Attachment 4 Follow-up Study Protocol

Attachment 4 GA protocol 4121.doc

Follow-up Study of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome in Georgia (Survey of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome & Chronic Unwellness in Georgia-Baseline Survey)

Attachment 4 Follow-up Study Protocol

OMB: 0920-0638

Survey of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Chronic Unwellness in Georgia

National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, Atlanta, GA

Departments of Medicine and Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA

Principal Investigator: William C. Reeves, MD, MSc

March 15, 2007

Phase 1 (February 2, 2004 to February 14, 2006)

Summary

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a complex medical and public health problem. It is estimated that approximately 700,000 adults in the U.S. suffer from CFS. They have been ill for 5-7 years, a quarter are unemployed or receive disability, yet fewer than 20 percent have received medical care for CFS. CFS is a Congressional and DHHS priority and CDC is responsible for its prevention and control. This study of CFS in metropolitan, urban, and rural populations of Georgia addresses major gaps in current knowledge that must be clarified in order to understand CFS and devise optimal control and prevention strategies. Minority racial/ethnic groups appear to disproportionately suffer from CFS and there is evidence of markedly different risks in metropolitan, urban, and rural populations. CFS is defined by self-reported symptoms, because as yet there are no defining physical symptoms or diagnostic laboratory abnormalities. Reasons for the discrepancies between studies attempting to identify risk factors and markers include the heterogeneity of the CFS population and varying rigor applying a standard case definition, which was derived by clinical consensus rather than empirically. This study of CFS in metropolitan, urban, and rural Georgia will estimate the prevalence of CFS in these distinct populations and measure associated risk factors that are important to understand and empirically define the illness. We will use random digit dialing methods to screen residents of metropolitan, urban, and rural communities of Georgia, and interview in detail those reporting fatigue or other unwellness of at least a month’s duration, as well as a random sample of healthy controls. We will assess subjects identified in the telephone survey who appear to meet the case definition of CFS, a random sample of persons reporting other chronic unwellness, and a matched set of healthy controls. Assessments will include clinical evaluation of each subject’s medical and psychiatric status, psychosocial factors, and cognitive functioning. We will also obtain specimens for endocrine and immune measures and future genotype studies. Findings from our study will be used to estimate the prevalence of CFS in defined populations, evaluate demographic and psychosocial factors associated with CFS, and help to develop an empiric case definition for CFS. Our findings will also generate specific hypotheses that will help to further our understanding of the underlying pathophysiology of CFS.

Performance Sites

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA (OHRP # FW A 00001413)

Departments of Medicine and Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA (OHRP # MI426)

Abt Associates, Inc. 640 North LaSalle Street, Suite 400, Chicago, IL 60610 (OHRP # IRB00001281)

Key Personnel

William C. Reeves, MD, MSc CDC Principal Investigator (PI)

Joann House CDC Project Officer

James F. Jones, MD CDC CDC Deputy PI

Christine Heim, PhD Emory University Emory Deputy PI

Rosane Nisenbaum, PhD CDC Coordinator Biostatistics

Dimitris Papanicolaou, MD Emory University Coordinator Endocrinology

Suzanne D. Vernon, PhD CDC Coordinator Molecular Epidemiology

Abt Associates Inc. CDC has contracted with Abt Associates to implement those tasks necessary to complete the study. This includes collaboration in study design and sampling strategies, random-digit-dialing screening surveys, detailed telephone surveys, and clinical evaluation.

Key CDC/Emory University Personnel Qualifications

Dr. Reeves is Chief of the Viral Exanthems & Herpesvirus Branch (VEHB), Division of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, NCID and has served as Principal Investigator for CDC’s chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) research program since 1992. He is a medical epidemiologist with expertise in infectious and chronic diseases. He is an elected member of the American Epidemiologic Society, an elected Fellow American College of Epidemiology, and elected Fellow in the Infectious Diseases Society of America. He is a recipient of the Amador Guerrero Medal (the highest honor awarded by Panama in the field of science and equivalent to the U.S. Medal of Science) awarded by the President of Panama in recognition of his research and service to public health. Dr. Reeves has published 170 peer-reviewed articles of which 30 deal with CFS (encompassing the case definition, prevalence, incidence, outbreaks, risk factors, clinical aspects, laboratory measures, and stress).

Ms House has been Administrative Officer and Deputy Director for VEHB since 1996. Prior to this (1990 to 1996) she was Program Specialist responsible for DVRD program management. She is currently responsible for administrative management of the VEHB CFS and human papillomavirus research programs and serves as Project Officer for all CDC funded studies of CFS. Because optimal administrative management requires ongoing integrated analysis and interpretation of management information related to large epidemiology, clinical, and molecular biology laboratory studies, she participates actively in the CDC CFS Research Group to maintain a level of scientific competence sufficient to place management into an appropriate context.

Dr. Jones is a senior Medical Research Officer in VEHB and will serve as Deputy PI to oversee clinical aspects of this study. He is board certified in Pediatrics and Allergy/Immunology. Prior to accepting a position at CDC last year he was Professor of Pediatrics at the National Jewish Medical Center and University of Colorado School of Medicine. He was responsible for an active CFS research program involving clinical studies, studies of behavior and CFS, studies of immunology and CFS, studies of infectious agents and CFS, and studies of endocrinology and CFS. Between 1986 and 2002 he was been PI on 4 NIH RO-1 grants investigating CFS. He has written 20 book chapters and 75 peer-reviewed publications.

Dr. Heim is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine and will serve as Deputy PI to oversee psychiatric and behavioral medicine aspects of this study. She is a research clinical psychologist who is internationally recognized in the field of early-life stress and chronic diseases. In the 3 years prior to relocating to Atlanta from Germany, she was PI on 2 research projects investigating stress and chronic illness. Since 1997 she has written a book on stress and chronic disease, 14 book chapters, and 30 peer-reviewed publications on aspects of this topic. She is an active member of international neuroscience, endocrinology, and psychiatry, socialites, key investigator on two active RO-1 grants, and recipient of a Young Investigator Award. Since relocating to Emory University (partly supported by a CDC IPA) she has been an active collaborator in the CDC CFS research group and has served as co-PI on the Pilot National Survey for CFS (IRB 2936) and on the Clinical Research Center study of CFS in Wichita (IRB 3504).

Dr. Nisenbaum is a senior Biostatistician in VEHB. She has worked on CFS at CDC since 1994. Dr. Nisenbaum has been lead investigator internationally in deriving empiric definitions for CFS and other medically unexplained illnesses. She is also actively involved in studies of other chronic diseases related to infectious agents (cervical cancer and papillomavirus, recurrent respiratory papillomatosis and HPV, and genital herpes). She is author of 18 peer-reviewed publications involving the epidemiology or CFS, behavioral/infectious/immunologic risk factors for CFS, and definitions of CFS. Most recently she has helped to develop mathematical methods for integrating epidemiologic, clinical, gene expression and proteomics data to the study of CFS.

Dr. Papanicolaou is an Assistant Professor of Medicine in the Division of Endocrinology at the Emory University School of Medicine. He is board certified in Internal Medicine and Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism. Since 1996 (when he finished his residency), he has authored 20 peer-reviewed publications on aspects of endocrinology and immunology in areas related to CFS and has written 5 book chapters in this area. In 1998, he relocated from NIH (where he was a senior investigator responsible for clinical studies of endocrinology/immunology and CFS) to Emory and has been an active collaborator in the CDC CFS research group (supported by an IPA). Most recently, he was co-PI on the Clinical Research Center study of CFS in Wichita (IRB 3504) and PI on a CDC funded clinical study of adipose tissue, cytokines and CFS (IRB 3475).

Dr. Vernon is microbiologist and Chief of the VEHB Molecular Epidemiology Group. The Molecular Epidemiology Program combines epidemiology with powerful molecular and genomic technologies to identify markers and risk factors for CFS and to acquire an understanding of the underlying biologic correlated. She has worked on CFS at CDC since 1996 as co investigator in the Longitudinal Study of CFS in Wichita (IRB 1698), the National Pilot Study of CFS (IRB 2936), and on the Clinical Research Center study of CFS in Wichita (IRB 3504). She has served as CDC PI on contracts searching for novel pathogens associated with CFS, protein markers of CFS, isoelectric focusing to identify markers for CFS, endogenous retroviruses associated with CFS, and a contract investigating the economic impact of CFS. She is responsible for a CDC grant to the University of New South Wales to study post-infectious fatigue as a model for CFS, for a contract investigating the economic impact of CFS. Since 1996, she has authored 19 peer-reviewed publications on various aspects of CFS, including the first studies clearly showing a correlation between gene expression profiles and CFS. She also has two pending patents involving laboratory studies of CFS.

Key Abt Associates Personnel Qualifications

As noted above, CDC has contracted with Abt Associates Inc. to collect and deliver data for the Survey of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Chronic Unwellness in Georgia. Abt Associates staff are experienced with CDC telephone surveys and clinical studies involving CFS research. Below, we briefly describe the qualifications and responsibilities of Abt Associates’ project team. Upon request, CDC will furnish resumes to the IRB.

Bonnie Randall, a vice president at Abt Associates, is has been Abt Associates project director of all CDC CFS field studies since 1992. Ms. Randall has responsibility for and authority over the scientific, operational, and financial aspects of the task orders conducted under this master contract with CDC. Ms. Randall has two decades of experience in analytic and survey research. She has been associated with CFS studies since 1988.

Senior Survey Director, Marjorie Morrissey, has oversight of the telephone interview component and has day-to-day responsibility (budget, schedule, and staff) for the clinical evaluation component. She, too, has over twenty years of survey management experience and has extensive knowledge of CFS. She was Abt Associates study director for the Longitudinal Study of CFS in Wichita (IRB 1698), the National Pilot Study of CFS (IRB 2936), and on the Clinical Research Center study of CFS in Wichita (IRB 3504).

Senior statistician David C. Hoaglin, Ph.D. collaborated in study design and sampling strategies and will compute sample weights and calculate prevalence estimates and provide technical advice on project design and on analytic protocols. Dr. Hoaglin has provided statistical support for CDC projects, since 1996.

Chief economist, Larry Orr, Ph.D., is assisting CDC with the design the economic impact analysis plan and questionnaire. He will also provide analytic support. Dr. Orr has over thirty years experience in the design and analysis of large-scale research and evaluation projects, including major social experiments in welfare reform, health insurance, home health care, employment and training, and housing.

As study director for the telephone interview component, Survey Director Rebecca Devlin, has day-to-day responsibility (including schedule, budget, and staff). She will work closely with the programmer to implement the CATI versions of the instruments and will create the training materials for supervisors and interviewers. She has also assisted CDC with screener and detailed interview revisions. For the clinical evaluation component, Ms. Devlin will coordinate the trainings for neurocognitive testing and the interviewer-administered psychiatric interview. She has assisted CDC with consent form revisions. Previously, Ms. Devlin implemented the random-digit-dialing telephone survey for the National Pilot Study of CFS (IRB 2936). She also implemented the telephone component of the Clinical Research Center study of CFS in Wichita (IRB 3504).

Senior Analyst Maria Amoruso, task leader for clinical evaluation data collection, has lead responsibilities for implementing the clinic protocol. She has structured the clinic day and is currently working on staffing, space, laboratory, and training issues. She trained clinic staff for the final portion of the Longitudinal Study of CFS in Wichita (IRB 1698), developed data collection instruments for the clinic component of the National Pilot Study of CFS (IRB 2936), and developed and implemented the data collection protocol and quality assurance plan for the Clinical Research Center study of CFS in Wichita (IRB 3504).

Associate Keith Smith will manage data preparation and delivery for the telephone and clinical evaluation components. His specific responsibilities include developing the data entry specifications for paper questionnaires, cleaning questionnaire data, and delivering interim and final data files and documentation. Mr. Smith produced the final data deliverables for the final portion of the Longitudinal Study of CFS in Wichita (IRB 1698) and the telephone and clinical assessment data sets for the National Pilot Study of CFS (IRB 2936). He recently completed and submitted to CDC interim and final data files for of the Clinical Research Center study of CFS in Wichita (IRB 3504).

Field Manager, Sandra Henion, will manage clinic operations in Atlanta and Macon. Ms. Henion has set up and managed four clinics for CDC during the Longitudinal Study of CFS in Wichita (IRB 1698) (1997-2001) and managed clinic operations for the Clinical Research Center study of CFS in Wichita (IRB 3504). She will supervise the local clinic managers.

Study Consultants

Dr. Martin Meltzer, Ph.D., is an NCID senior health economist. He will collaborate with the Principal Investigator in the analysis of the economic data.

Acknowledgment of all funding sources and substantial contributions:

As part of a coordinated Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) program of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) research, CDC has been charged by the Congress to address CFS control and prevention. Congress has specified that CDC conduct population surveys of CFS. Monies appropriated by Congress for this purpose fund this study.

Statement of any conflict of interest:

None of the investigators have any conflict of interest in this project.

Face Page 1 Phase 1Summary 2 Description, Performance Site, and Key Personnel 3-7 Table of Contents 8

Phase 1 Research Plan 9A. Objectives and Specific Aims 9-10 B. Background and Significance 11-22 C. Research Design and Methods 23-57 D. Human Subjects 58-63 E. Literature Cited 64-70 F. Appendix Summary 71-72 Note—these approved Phase 1 appendices are not included in this submission

|

Phase 2Summary 79-74 Description, Performance Site, and Key Personnel 75-78 Phase 2 Research Plan 79A. Objectives and Specific Aims 79-80 B. Background and Significance 81-88 C. Research Design and Methods 89-116 D. Human Subjects 117-122 E. Literature Cited 123-128 F. Appendix Summary 129 F.1. Appendix 1: Press Release and Web Site F.2. Appendix 2: Telephone Interview Advance Letter F.3. Appendix 3: Telephone Non-Contact Letters F.4. Appendix 4: Detailed Telephone Interview F.5. Appendix 5: Descriptive materials sent prior to clinical evaluation F.6. Appendix 6: Physical Examination F.7. Appendix 7: Summary of Specimen Collection F.8. Appendix 8: Questionnaires Concerning Symptomatology F.9. Appendix 9: Assessment of Stress and Coping F.10. Appendix 10: Economic Impact F.11. Appendix 11: Health Services Utilization

|

A. Objectives and Specific Aims

A.1 Objective: Describe epidemiologic and clinical aspects of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) in defined Georgia populations.

A.2 Specific aims:

Specific Aim 1 - Determine the prevalence of CFS in different racial/ethnic groups representative of metropolitan, urban, and rural Georgia populations.

Hypothesis – the prevalence of CFS will differ by at least 2-fold between white and black populations.

Hypothesis – the prevalence of CFS will differ by at least 2-fold between metropolitan/urban and rural populations.

Specific Aim 2 - Determine factors associated with CFS in the metropolitan, urban, and rural populations of Georgia. Factors to be studied include: symptoms, demographics (sex, age, race/ethnicity), occupation, quality of life, health services utilization, life experiences, psychiatric comorbidity and endocrine-immune measures.

Hypothesis – symptoms and demographics of CFS will differ in metropolitan, urban, and rural populations.

Hypothesis – occupation, illness characteristics (e.g., type of onset, duration of illness, impairment/disability, physical and psychiatric symptom patterns), and utilization of health services will differ between metropolitan/urban and in rural populations.

Hypothesis – psychosocial factors (e.g., adverse life experiences, personality, coping mechanisms, etc.) will be associated with CFS.

Hypothesis – psychiatric comorbidity (e.g., mood and anxiety disorders) will be associated with CFS.

Hypothesis – endocrine-immune changes will be associated with CFS.

Hypothesis – polymorphisms of genes involved in CNS, neuroendocrine, and immune pathways will be associated with CFS.

Specific Aim 3 - Describe the economic impact of CFS on individuals, families, and the economies of metropolitan, urban, and rural Georgia.

Hypothesis – CFS will be associated with a substantial economic burden on affected individuals, their families, and society throughout Georgia.

Specific Aim 4 - Develop an empiric case definition for CFS based on symptoms and other illness attributes, and evaluate overlap with the 1994 CFS research case definition.

Hypothesis – the illness defined by symptoms and illness attributes (e.g., type of onset, duration of illness, impairment/disability, stress history, physical and psychiatric symptom patterns), and biomarkers will more accurately identify patients with CFS than the consensus 1994 research case definition and will differentiate subcategories of CFS.

Hypothesis –endocrine and immune changes, psychiatric symptoms and type/severity of life experiences, psychological traits, and specific polymorphisms, will vary with fatigue states, symptoms and illness characteristics, and will help to differentiate subgroups of CFS.

Specific Aim 5 - Identify persons representative of the Georgia population with CFS, unwellness and a healthy comparison group to invite for future enrollment in General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) studies at Emory University. Select persons with risk factors for CFS identified in Aim 2 for enrollment in GCRC mechanistic studies. Similarly, select patients with CFS or unwellness based on biological factors identified in Aim 4 for GCRC mechanistic studies.

GCRC proposals based on results of these studies and those of others will be developed under separate protocols and address: 1) specific hypotheses concerning mechanisms and pathophysiology of CFS, 2) specific treatments and interventions, and 3) polymorphisms of genes involved in CNS, neuroendocrine, and immune pathways, as possible examples.

B. Background and Significance

CFS is a complex medical and public health problem. It is estimated that approximately 700,000 adults in the U.S. suffer from CFS. Their median duration of illness is 7 years, a quarter of them are unemployed or receiving disability, yet fewer than 20 percent have received medical care for CFS (Reyes, 2003). Despite more than 3,000 articles in the peer-reviewed medical literature, the pathophysiology of CFS is not well understood. There are no diagnostic laboratory abnormalities or clinical tests. There is no specific treatment or prevention strategy for CFS. CFS is a DHHS priority and CDC is the lead agency for research concerning prevention and control. CFS is also a Congressional priority. Beginning in 1992, Congressional language has stressed legislators’ desire for CDC to conduct community-based CFS surveillance. Recently Congressional language has directed that CDC should target race/ethnicity-specific differences in the occurrence of CFS and should accelerate its CFS research plan to identify the causes, risk factors, diagnostic markers, and economic impact of CFS. This protocol was designed to conduct surveillance of CFS in the metropolitan, urban, and rural populations of Georgia and to address these Congressional mandates. Recently Congress has also directed CDC to accelerate its educational activities for health care providers and this study will collect information concerning health care utilization that is necessary to optimally develop our educational program. Finally, Congress has directed CDC to create a CFS patient registry and information from the Georgia surveillance study (especially as related to rural populations) will be pivotal for developing registry strategies. Each of the Specific Aims discussed below addresses our program objectives and congressional concerns in the context of major unanswered questions concerning the characteristics of CFS in the general population.

B.1 Aim 1 – Prevalence of CFS in Metropolitan, Urban, and Rural Georgia Populations

B.1.a Hypothesis – the prevalence of CFS will differ by at least 2-fold between white and black populations.

B.1.b Hypothesis – the prevalence of CFS will differ by at least 2-fold between metropolitan/urban and rural populations.

An understanding of the prevalence and distribution of CFS is fundamental to focusing etiologic research, targeting health-care and educational programs, and estimating the effects of debilitating fatiguing illnesses on quality of life and productivity. By ranking the burden of CFS and fatiguing illnesses among other national health concerns, a prevalence estimate can help frame appropriate health policy and raise political and public awareness for the concerns that emanate from this misunderstood and stigmatized syndrome.

Previous studies have estimated a wide range of CFS prevalence, from 2.3 to 600 per 100,000 persons [Bates et al., 1993; Jason et al., 1999; Lloyd et al., 1990; Reyes et al., 1997; Steele et al., 1998; Wesley et al., 1997]. Prevalence estimates from those studies cannot be directly compared because of the lack of and inconsistent use of a standard CFS case definition [Reeves et al., submitted], varying degrees of rigor in examining subjects [Holmes et al., 1988] differences in study populations [Reyes et al., 1997; Buchwald et al., 1995; Lloyd et al., 1990; Jason et al., 1999; Minowa et al., 1996], sampling strategies, and methods for estimating prevalence [Fukuda et al., 1994; Lloyd et al., 1990; Sharpe et al., 1991; Kitani et al., 1992]. Physician-based surveillance studies, although they reflect the burden of CFS on the health care system, underestimate the true burden CFS imposes on both individuals and the population.

Only two studies (by CDC and DePaul University) have used population-based random samples to estimate the prevalence of CFS and describe its demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Both studies used the 1994 CFS Research Case Definition [Fukuda et al., 1994]. The DePaul study estimated a prevalence of 422 per 100,000 in Chicago [Jason et al., 1999] and the CDC study found 235 per 100,000 adults in Wichita to suffer from CFS [Reyes et al., 2003]. These rates were not statistically different. In both studies, CFS primarily affected women, and suggested an increased prevalence, although non-significant, among non whites.

The two studies used different sampling and analysis strategies, confidence intervals for their various estimates overlapped, and there are limitations to their generalizability. Thus, in July 2001, CDC conducted a pilot survey to determine feasibility and test procedures for a National Survey of CFS [Bierl et al., submitted]. To examine regional and metropolitan differences, the pilot survey sampled strata from statistical areas in each of the four US census regions (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West) and was further stratified into urban and rural statistical areas. Urban areas included; Buffalo-Niagara Falls, New York; Chicago, Illinois; Baton Rouge, Louisiana; and Oakland, California. Rural areas included; Franklin County, Pennsylvania, Ripley County, Indiana, Monroe County, Georgia, and Chaves County, New Mexico. We sampled 2,728 households and surveyed 7,317 residents (the screening interview CASRO response rate was 70%1 and 77% of the detailed interviews were completed)[Bierl et al., submitted]. The pilot survey was not designed to rigorously estimate CFS, but CFS-like illness (meets criteria of 1994 CFS Research Case Definition, pending physical examination) was reported by 1.2 percent of the population (similar to both the Wichita and Chicago studies). CFS-like illness was more common in persons with annual incomes < $40,000 and in those with less than a high school education. The survey found no evidence for differences in the prevalence of CFS-like illness by geographic region, but rural rates were 60% higher than those of urban residents.

The pilot study also showed that nation-wide epidemiologic studies of CFS posed significant technical problems because clinical evaluation, which is necessary to confirm classification of CFS, was not practical on a national level. This finding, in conjunction with the tragic events of September 11, 2001 [Heim et al., submitted], precluded a subsequent CFS study on a national level.

We have modified the concept of the National Survey of CFS by limiting data collection to one Southern U.S. state (Georgia). This more focused research is better able to serve the objectives of the National Survey of CFS and additional CDC objectives. Reasons supporting this statement are the following: 1) Logistics - A difficulty in the pilot survey was matching subjects and physicians for clinical evaluations because subjects were, of course, scattered across the continent. Focusing on a single state, Georgia allows operation of regional clinics and greater opportunities for collaboration between and among CDC, Emory University and Abt Associates. 2) Metropolitan, urban and rural differences - The pilot survey results suggest no regional differences in the occurrence of CFS-like illnesses between and among the Midwest, south, west, and northeast, so concentrating on one state (Georgia) should provide generalizable information. The pilot survey findings suggested the importance of further evaluating urban and rural differences in the occurrence of CFS. Again, Georgia supports such a study with a major metropolitan center (Atlanta), well-defined urban areas (Macon and Warner Robins), and rural populations (in counties surrounding Macon/Warner Robbins) with well-defined regional differences. 3) Racial/ethnic differences - As noted earlier, the prevalence of CFS in minority populations must be appropriately evaluated. Population-based studies have indicated that risk for CFS may be elevated the black and Hispanic populations [Steele et al., 1988; Jason et al., 1999; Reyes et al., 2003]. Georgia has well-characterized urban and rural white, black, and Hispanic populations of varying socioeconomic status living in the regions to be studied. The presence of these populations, geographically contiguous to CDC/Emory University, is ideal for public health surveys. Taken together, the proposed GA survey will produce estimates of the prevalence of CFS in metropolitan, urban and rural populations and will elucidate racial/ethnic differences in CFS in these populations.

B.2 Aim 2 - Factors Associated with CFS in Metropolitan, Urban, and Rural Georgia Populations

B.2.a Hypothesis – symptomatology and demographics of CFS will differ in metropolitan, urban, and rural populations. Results from the Pilot National Survey suggest possible differences in risk of CFS between urban and rural communities (see above). Such differences must be evaluated in order to devise and implement appropriate prevention and control activities. Metropolitan, urban and rural populations reflect different demographic profiles, as well as differences in illness attributes and health-seeking behaviors. Data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey [Larson, 2003] suggest that there are not only demographic differences between urban and rural communities, but that there are also differences in perceived health, activity, access to health care, and utilization of health services. The sense of community in a population influences several of these parameters [Ahern, 1996]; as does the patient’s perception of their medical care [Ax, 1997].

B.2.b Hypothesis – occupation, illness characteristics (e.g., type of onset, duration of illness, impairment/disability, physical and psychiatric symptom patterns), and utilization of health services will differ between metropolitan/urban and in rural populations. The median duration of illness among persons with CFS identified in community studies varied between 2.5 and 7.3 years (Reyes et al., 2003; Jason et al., 1999]. In spite of this, only half of those with CFS in Chicago were under medical care [Jason et al., 2000] and only 16% of persons identified with CFS in Wichita had received medical care for CFS [Solomon et al., submitted]. Similarly, a clinic-based study in Seattle found that individuals with chronic fatigue, CFS, and fibromyalgia each saw multiple medical physicians, but that those with CFS or fibromyalgia saw alternative providers, such as chiropractors, more frequently than did the other subjects [Bombardier and Buchwald, 1996]. These observations, in the context of the preceding discussion, document the need to determine if occupation, illness characteristics, and utilization of health services by persons with CFS and appropriate comparison groups differ between defined metropolitan, urban, and rural populations.

B.2.c. Hypothesis – psychosocial factors (e.g., adverse life experiences, personality, coping styles) will be associated with CFS. Mainly based on clinical observations, stress (including physical insults such as childhood disease) or emotional traumas have long been considered as major precipitating factors in the development of CFS. Few epidemiological or clinical studies have evaluated the association between severe stress or trauma and CFS or other fatiguing illnesses. One study reported that acute exposure to Hurricane Andrew induced relapses of CFS and symptom exacerbations in a sample of 49 CFS patients living in South Florida [Lutgendorf et al., 1995]. The extent of individual emotional and behavioral stress responses was the single and strongest predictor of the likelihood and severity of the relapse and functional impairment within 4 months after the hurricane. Our group reported that the self-reported chemical, emotional, and physical exposures in Gulf war veterans was related to the prevalence of a multi-symptom fatigue-like illness [Nisenbaum et al., 2000]. Several other studies report elevated rates of CFS in Gulf War veterans, and CFS is associated with combat-related post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in these veterans [McCauley et al., 2002; Kang et al., 2003]. It thus appears that severe stress in adulthood might be a precipitating factor of CFS, or at least in a subgroup of CFS patients.

In recent years, much attention has been directed towards understanding the long-term effects of stress during development on long-term health and functioning. Epidemiological studies provide compelling evidence for a strong association between adverse childhood experiences (e.g., abuse or neglect, parental loss and household dysfunction) and unwellness later in life [McCauley et al., 1997; Felitti et al., 1998]. One study involving almost 2000 women reported that those who had been abused as children exhibited increased levels of fatigue and pain in adulthood, and additional symptoms of depression, anxiety, substance abuse and interpersonal sensitivity when compared to women not abused as children [McCauley et al., 1997]. A population-based study conducted in New Zealand reported elevated rates of chronic fatigue in women with childhood adversity [Romans et al., 2002]. One population-based study reported an association between childhood abuse and fatiguing illnesses [Taylor & Jason, 2001]. Childhood abuse also accounted for comorbidity with anxiety disorders (e.g., PTSD). A study in tertiary care patients with CFS found that those with CFS more frequently reported various types of abusive victimization starting in childhood and persisting throughout adulthood, as compared to controls [van Houdenhove et al., 2001]. Another recent clinical study found that an overprotective maternal parenting style and maternal depression, which is often associated with lack of care giving, were associated with a diagnosis of CFS [Fisher & Chalder, 2003].

Since stress exacerbates CFS in adults, these findings support a stress-diathesis model, which postulates that genetic liabilities interact with stressful experiences in determining individual vulnerability to disease, including CFS. This vulnerability likely reflects the combined effects of early experience and genes on the developing brain, resulting in a stable phenotype with different neurobiological expressions, which may determine perceptual thresholds and the "set-point" of neuroendocrine, immune and behavioral reactivity to the environment [Heim & Nemeroff, 2001], thereby contributing to the development of CFS upon further challenge (see Figure 1 below in section on endocrine and immune function).

In addition, certain psychological factors might influence individual adaptation to CFS. One important factor comprises illness attributions. It has been reported that CFS patients tend to attribute their illness to physical causes (like viruses or pollution) and minimize or neglect psychological or personal circumstances. Importantly, these attributions seem to be a risk factor for the exacerbation and perpetuating of CFS and are also accompanied by greater disability [Butler et al., 2001]. Negative coping styles, such as denial or disengagement, have also been shown to be important in the development and perpetuation of CFS [Afari & Buchwald, 2003]. Several other authors suggest an association between CFS and certain personality traits [Fiedler et al., 2000; White & Schweitzer, 2000]. Taken together, it appears that attribution styles, coping strategies and personality traits might influence the development and course of CFS. The proposed study will assess these associations.

B.2.d. Hypothesis – psychiatric comorbidity (e.g., mood and anxiety disorders) will be associated with CFS: Psychiatric disorders that may cause chronic fatigue are exclusionary for a diagnosis of CFS [Fukuda et al., 1994]. Exclusionary psychiatric disorders include major depression with melancholic features, bipolar disorder, psychotic disorders, and eating disorders and substance abuse disorders within 2 years of the onset of the fatigue. However, other psychiatric disorders that are not exclusionary for CFS may be associated with the development and persistence of CFS. Indeed, there are high rates of comorbidity between CFS and psychiatric disorders, mainly with respect to mood, anxiety and somatoform disorders, when compared to individuals with other chronic illnesses or healthy subjects. Rates of comorbidity between CFS and these disorders, determined in community and clinical samples, range between 45-82% for any psychiatric diagnosis, 23-67% for depression, 2-30% for anxiety disorders and 6-28% for somatoform disorders [reviewed in Ax et al., 2001; Afari & Buchwald 2003]. There is also evidence for increased rates of personality disorders among CFS patients [Ciccone et al., 2003]. Because these disorders have symptoms similar to CFS, it is likely that most studies over-estimate rates of comorbidity. The apparent variability in the estimates likely reflects differences in the sampling of CFS cases (community versus clinical samples) and differences in the method of psychiatric assessment (self-report versus diagnostic interview).

The nature of the relationship between CFS and these psychiatric disorders remains obscure but has important implications regarding therapy [Reid et al., 2000}. It is possible that 1) CFS causes psychiatric disorders, 2) psychiatric disorders cause CFS, 3) certain psychiatric disorders are incorrectly diagnosed in CFS patients because of overlap in symptomatology, 4) CFS and certain psychiatric disorders are independent disorders with high rates of comorbidity, and 5) CFS and certain psychiatric disorders share pathophysiologic mechanisms and represent covariates of one underlying process [Nisenbaum et al., 2000; Reyes et al., 1996; Suraway et al., 1995].

B.2.e Hypothesis –endocrine and immune biomarkers will be associated with CFS

Numerous studies have searched for a pathophysiological basis of CFS and other fatiguing illnesses. They have identified multiple neuroendocrine and immune alterations and alterations in sleep and neural circuitry in patients with CFS. One particular area of focus has been hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function in persons with CFS. The HPA axis constitutes one of the major peripheral outflow systems of the brain, serving to adapt the organism to changes in the internal and external milieu. Alterations of the HPA axis may thus represent a common pathway linking antecedent factors, such as infection and stress, with immune disturbances, altered behavior and symptoms of CFS [see, e.g., Heim et al., 2000].

Several

studies have provided evidence for impairment of the HPA axis and

increased immune function in CFS. Patients with CFS exhibit low

cortisol levels compared to healthy controls [Demitrack et al., 1991;

Scott & Dinan 1998; Parker et al., 2001]. Low cortisol

availability might play a causal role in CFS. For example, adrenal

insufficiency, a condition characterized by hypocortisolism, shares

several symptoms with CFS (such as flu-like symptoms, fatigue,

malaise, arthralgia, myalgia, sleep abnormalities, headaches,

dizziness, and decreased memory). Glucocorticoids are important

regulators of immune function. For example, during prolonged stress,

glucocorticoids have a suppressive effect on the production of

inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, which might prevent toxic

effects of immune reactions [Munck et al., 1994]. Conversely, a lack

of cortisol effects might be associated with overproduction of

inflammatory cytokines [Heim et al., 2000; Raison & Miller,

2003]. The increased production of inflammatory cytokines may be at

least partially, responsible for the symptom complex of cortisol

deficiency, which greatly overlaps with the symptom complex of CFS

[Papanicolaou et al., 1996]. Thus, chronic cortisol deficiency, as

seen in CFS, could result in chronic overproduction of IL-6 and other

immune mediators. Indeed, overproduction of inflammatory cytokines,

such as IL-6 has been reported in patients with CFS [Gupta, 1999;

Cannon, 1995]. Administration of IL-6 to normal volunteers causes

symptoms of CFS [Papanicolaou et al., 1996]. However, studies of CFS

patients have not uniformly identified elevated serum inflammatory

cytokine levels, nor have they uniformly found altered levels of

serum cortisol. A possible explanation for such disagreements might

be that physiological measures vary with the clinical course of CFS,

including frequent remissions and relapses, which in turn might be

influenced by other factors, such as stress and behavioral styles.

To address the above possibilities in a coordinated manner, the

current study will measure of endocrine-immune markers in saliva and

plasma and will relate these measures to CFS status and illness

attributes (also see Aim 4).

Several

studies have provided evidence for impairment of the HPA axis and

increased immune function in CFS. Patients with CFS exhibit low

cortisol levels compared to healthy controls [Demitrack et al., 1991;

Scott & Dinan 1998; Parker et al., 2001]. Low cortisol

availability might play a causal role in CFS. For example, adrenal

insufficiency, a condition characterized by hypocortisolism, shares

several symptoms with CFS (such as flu-like symptoms, fatigue,

malaise, arthralgia, myalgia, sleep abnormalities, headaches,

dizziness, and decreased memory). Glucocorticoids are important

regulators of immune function. For example, during prolonged stress,

glucocorticoids have a suppressive effect on the production of

inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, which might prevent toxic

effects of immune reactions [Munck et al., 1994]. Conversely, a lack

of cortisol effects might be associated with overproduction of

inflammatory cytokines [Heim et al., 2000; Raison & Miller,

2003]. The increased production of inflammatory cytokines may be at

least partially, responsible for the symptom complex of cortisol

deficiency, which greatly overlaps with the symptom complex of CFS

[Papanicolaou et al., 1996]. Thus, chronic cortisol deficiency, as

seen in CFS, could result in chronic overproduction of IL-6 and other

immune mediators. Indeed, overproduction of inflammatory cytokines,

such as IL-6 has been reported in patients with CFS [Gupta, 1999;

Cannon, 1995]. Administration of IL-6 to normal volunteers causes

symptoms of CFS [Papanicolaou et al., 1996]. However, studies of CFS

patients have not uniformly identified elevated serum inflammatory

cytokine levels, nor have they uniformly found altered levels of

serum cortisol. A possible explanation for such disagreements might

be that physiological measures vary with the clinical course of CFS,

including frequent remissions and relapses, which in turn might be

influenced by other factors, such as stress and behavioral styles.

To address the above possibilities in a coordinated manner, the

current study will measure of endocrine-immune markers in saliva and

plasma and will relate these measures to CFS status and illness

attributes (also see Aim 4).

B.3 Aim 3 - Economic Impact of CFS.

The ability of CFS patients to carry out productive lives can be severely limited and CFS likely imposes a large burden on society. Economic cost of illness is an important element in understanding its overall impact and in deciding the allocation of health recourses. Several, clinic-based, studies have found CFS patients to have substantial functional impairment compared with both healthy controls and other chronically ill patient groups [Buchwald et al., 1996; Hardt et al., 2001; Komaroff et al., 1996]. Other clinical studies have reported patients with CFS to be more severely impaired than persons with end-stage renal disease [Hart et al., 1987], heart disease [Bergner et al., 1984], and multiple sclerosis [Komaroff et al., 1996].

However, scant empirical scientific work exists to quantify the economic impact of CFS. Previous studies have addressed consequences of CFS in terms of disability (16%) and unemployment (21%) [Jason et al., 1999; Nisenbaum et al., 2003; Solomon et al., 2003]. CFS imposes a significant burden on both society and those living with the syndrome. Only three studies, all of which were clinic based, have attempted to quantify the impact of CFS, and each showed that people with the syndrome were likely to have lost their job or to be unemployed [Lloyd & Pender, 1992; Bombardier & Buchwald, 1996; McCrone et al., 2003]. Persons with CFS also pose a disproportionate burden on the health care system and their families since they are sick for long periods of time and since there is no known cure for the illness [McCrone et al., 2003].

Persons with CFS incur direct costs associated with healthcare services and products used for the diagnosis, assessment, and management of an illness. Perhaps more important, persons with CFS suffer indirect costs irrespective of their health care. Indirect costs are affiliated with the loss in productivity attributed to a particular illness – that is, forgone income due to a decrease in hours worked or required job change. Medical and nonmedical costs are usually described as resources expended, and productivity losses are described as resources foregone. The individual will experience a lower standard of living due to foregone resources stemming from increased morbidity and mortality. Additionally, the government foregoes tax revenue as well due to lost (reduced) earnings.

Our preliminary estimates [Reynolds et al., submitted] indicate that CFS accounts for $9.1 billion annually in lost productivity. The loss in earnings and wages disproportionately affects women, who carried almost 90% of this burden [Reynolds et al., submitted]. We will use data from the Georgia Survey to precisely measure lost productivity associated with CFS. These costs to society as a whole (i.e., society’s costs related to reduced levels of output, time spent to obtain health care, and lost productivity resulting from change in employment status as a result of morbidity or mortality) emphasize the importance of on-going research to determine causes and develop treatments for this devastating illness.

B.4 Aim 4 Case Definition

B.4.a Hypothesis – the illness defined by symptoms and illness attributes (e.g., type of onset, duration of illness, impairment/disability, stress history, physical and psychiatric symptom patterns), and biomarkers (such as endocrine and immune parameters) will more accurately identify patients with CFS than the consensus 1994 research case definition and will differentiate subcategories of CFS.

The International CFS Research Case Definition [Fukuda et al., 1994] stipulates that patients have the following: 1) clinically evaluated, unexplained, persistent or relapsing chronic fatigue (of least 6 months duration) that is of new or definite onset (i.e., has not been lifelong); 2) is not the result of ongoing exertion; 3) is not substantially alleviated by rest; and 4) results in substantial reduction in previous levels of occupational, educational, social, or personal activities. These descriptors of fatigue are difficult to apply in practice. In addition, the case definition represents a clinical-consensus document that is not based on experimental evidence.

The etiology and pathophysiology of CFS remain unknown, and there is a lack of consensus in the findings of many well-conducted studies both within and between centers [Wilson et al., 2001]. Difficulties with accurate case ascertainment are a major contributor to this problem. Much of the difficulty reflects conceptual and operational problems inherent in classifying an illness defined by symptoms and reported disability [Taylor et al., 2001].

CDC has convened an International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group, which has focused on aspects of a case definition [Reeves et al., submitted]. The Study Group has recommended a standardized approach to persons with CFS, which we have adopted in this protocol. The Group has also recommended standardized and validated instruments to be used in assessment of fatigue, disability, and other CFS case-defining symptoms, which we will use in this protocol. Individual instruments are discussed below (Section C.2.e Clinical Evaluation). Finally, the Group has recommended studies of patients with chronic unexplained fatigue from which a definition of CFS can be empirically derived, the subject of specific aim 4.

Defining CFS empirically is not trivial. We think that CFS may be categorized as a functional somatic syndrome because its symptoms, suffering and disability do not correlate with objective findings in patients [Barsky & Borus, 1999]. Other functional syndromes include irritable bowel syndrome, chronic pelvic pain, fibromyalgia, atypical or non-cardiac chest pain, tension headache, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and multiple chemical sensitivities. Wessely et al. [1999] reviewed several characteristics of functional somatic syndromes, including chronic fatigue syndrome, and found substantial overlap of diagnostic features (e.g., symptoms) and in associations with sex, psychological distress, physiology, history of childhood maltreatment and abuse, difficulties in doctor-patient relationship, and response to treatment. Because of this overlap, they suggest a scheme of classification that would consider not only types of symptoms, but also duration of symptoms, associated mood disturbance, patients’ attributions for the symptoms, and identifiable physiological processes. With Specific Aim 4, we will attempt to derive such a classification scheme using data collected during the clinical evaluation and statistical techniques such as structural equation modeling.

B.5 Aim 5 - General Clinical Research Center Studies

A continuing need in the study of CFS is identification of biomarkers that would contribute to patient identification and to determination of pathogenesis. Two approaches are proposed here. The first is the collection of samples from a large number of individuals as is only possible in a population based study, with performance of assays following the completion of subject accrual. Testing for genetic polymorphisms is a good example of this approach.

Genetic studies (including family, adoption, twin, and molecular genetic studies) have now provided compelling evidence that many diseases, including functional somatic syndromes and the major psychiatric disorders, have one or more genetic components. Studies on the genetics of complex functional disorders have been hampered by a variety of factors, such as genetic heterogeneity (a similar phenotype develops from different genotypes), pleiotropy (the same gene contributes to the manifestation of several different disorders, leading to comorbidity) and incomplete penetrance of the phenotype (genetic risk might be uncovered by an environmental trigger) [see Radant et al., 2001; Heim, Bremner & Nemeroff, in press]. Little is known about genetic variants which may confer susceptibility to CFS, but there is reason to believe that CFS does have a genetic component. Twin studies have shown varying degrees of heritability of CFS, and familial clustering of CFS has been observed in several studies [Buchwald et al., 2001; Hickie et al., 2001; Walsh et al., 2001; Endicott 1999; Levine et al., 1998; Torpy et al., 2001]. It is conceivable that polymorphisms in genes involved in neuroendocrine-immune pathways and neurotransmission might confer vulnerability to CFS in interaction with other factors. We will therefore assess single nucleotide polymorphisms in our population-based sample. We will specifically assess mutations or polymorphisms in immune- and neurotransmitter-related genes, including genes of cytokine receptors, adrenergic receptors, selected complement components, serotonin, and transporters as well as dopamine receptors and transporters. Since allergy also appears to be common in CFS, we will also examine genes suspected to be associated with the allergic diathesis.

For example, only recently, a common polymorphism of the serotonin transporter (SERT) gene has been demonstrated to determine the risk to develop psychopathology related to stress, including early adverse experience [Caspi et al., 2003]. Such polymorphisms in several candidate genes will be the initial focus of the study, but DNA samples from each patient will be stored and may be subjected to additional analyses as new candidate loci are identified.

One of the strengths of this study is the ability to evaluate the prevalence of mutations or polymorphisms in candidate genes in the CFS population as compared not only to unaffected populations but also to populations with other fatiguing conditions. One of the recurrent themes in CFS research and clinical management has been the challenge of distinguishing it from the myriad of other conditions which can cause similar symptoms. If particular genetic variations appear preferentially in individuals with CFS, they could be tested in prospective studies as potential biological markers and rapidly incorporated into clinical practice. Additionally, insights into the fatigue process on a molecular level would have wide applicability to other medical conditions, and potentially help elucidate drug efficacy variability and differing host-responses to a variety of pathogens and antigens.

The second can only take place when persons fulfilling strict definitional criteria are identified and entered into appropriate study protocols. The Georgia survey will identify subjects who meet these criteria. They will be asked to grant permission to be contacted for possible enrollment into studies to be performed at Emory University.

C. Research Design and Methods

C.1 Design

C.1.a Study population. This cross-sectional study will use a random-digit-dialing survey to identify, and enroll subjects representative of metropolitan, urban, and rural Georgia populations. To identify persons with CFS and comparison subjects who are unwell and have similar symptoms of CFS, we will enroll Unwell subjects. Unwell subjects are defined as reporting one month or more duration of any of the following CFS defining symptoms (severe fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, impaired memory or concentration, muscle or joint pain). Unwell subjects will be further evaluated to identify the subset with CFS. Well subjects who do not report any of these CFS defining symptoms for one month or longer will comprise the control group.

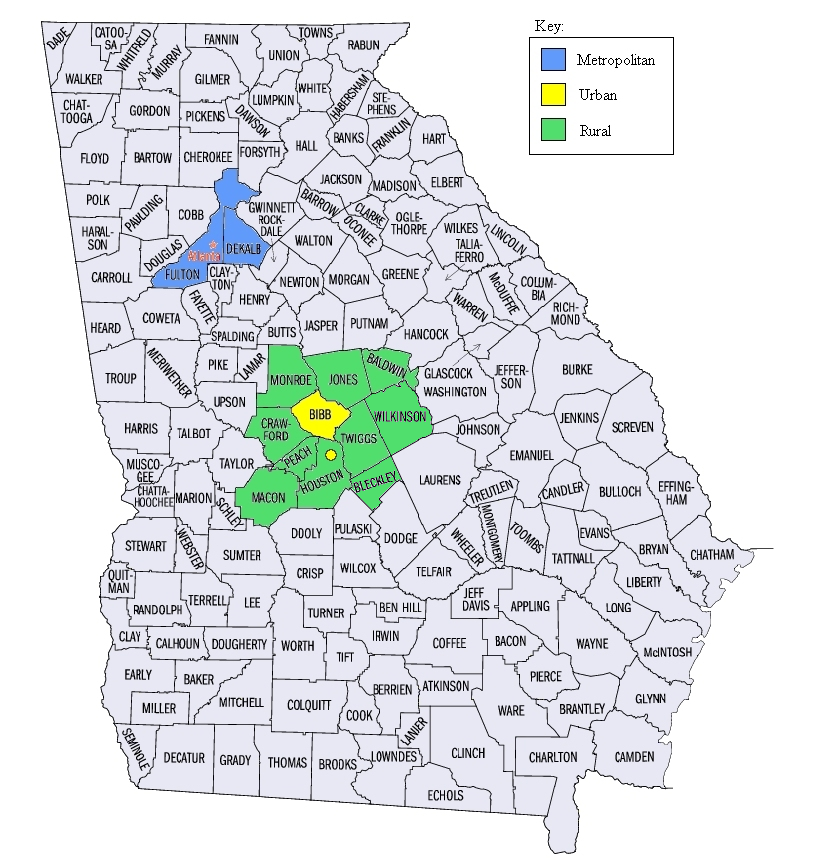

The

metropolitan (Atlanta) population will consist of the residents of

DeKalb and Fulton counties. The urban population will consist of

residents of Macon (Bibb county) and the adjoining city of Warner

Robins (in Houston County). The rural population will include

residents of counties surrounding Bibb, specifically Houston

(excluding Warner Robins), Monroe, Jones, Baldwin, Wilkinson, Twiggs,

Peach, Crawford, Bleckley, and Macon counties. We limited the study

to the Atlanta and Macon areas for logistic reasons (conducting

clinical evaluations). Atlanta is the major metropolitan center of

Georgia and we chose the two counties that encompass its core. Macon

and Warner Robins represent typical urban Georgia, and the areas

surrounding Macon/Warner Robins will represent rural Georgia.

The

metropolitan (Atlanta) population will consist of the residents of

DeKalb and Fulton counties. The urban population will consist of

residents of Macon (Bibb county) and the adjoining city of Warner

Robins (in Houston County). The rural population will include

residents of counties surrounding Bibb, specifically Houston

(excluding Warner Robins), Monroe, Jones, Baldwin, Wilkinson, Twiggs,

Peach, Crawford, Bleckley, and Macon counties. We limited the study

to the Atlanta and Macon areas for logistic reasons (conducting

clinical evaluations). Atlanta is the major metropolitan center of

Georgia and we chose the two counties that encompass its core. Macon

and Warner Robins represent typical urban Georgia, and the areas

surrounding Macon/Warner Robins will represent rural Georgia.

The process of sampling the study population using an RDD sample, involves a number of steps. Please refer to the flowchart below. First, a random sample of telephone numbers from the selected Georgia counties is drawn. These numbers are then screened for business and nonworking numbers using the GENESYS ID Plus sampling system. Nonworking and business numbers are removed from the sample.

Telephone

numbers randomly drawn for selected counties in Georgia.

Addresses appended to telephone numbers through reverse address

matching.

Advance letters sent for telephone numbers where matched addresses

are found.

Sampled telephone numbers dialed to attempt screening interviews.

Respondent(s)

sampled for detailed interview.

No respondents sampled for detailed interviews.

Attempt detailed interview(s) for sampled household member(s).

Then, using a reverse address matching process, addresses are appended to telephone numbers where matched addresses are found. Advance letters are sent to telephone numbers with matched addresses prior to initial contact. When addresses are available, noncontact letters are sent to households where we are having difficulty reaching household members to complete screening interviews.

Following the screening interviews, a detailed interview is attempted with each selected respondent. When addresses are available, noncontact letters are sent to respondents with whom we are having difficulty reaching to conduct detailed interviews. The following sections describe the interviewing process in more detail.

C.1.b Population Survey. The survey will include four components:

A Screening Telephone Interview of a single household informant to provide a household census (for deriving weights to be applied during analysis) and to identify Unwell household members who have at least one of the core CFS-defining symptoms for a month or longer (fatigue, cognitive impairment, unrefreshing sleep or muscle/joint pain) and Well residents (subjects that have none of these problems for at least a month).

A Detailed Telephone Interview of respondents between 18 and 59 years of age including all Unwell identified as fatigued, a random sample of selected Unwell subjects who are not fatigued (i.e., identified with cognitive impairment, pain, or sleep problems) and a random sample of Well to:

determine classification as CFS-like (i.e., those who report fatigue characteristics and symptoms of CFS and report no exclusionary medical or psychiatric conditions) and thus eligibility for clinical evaluation (Aims 1-5).

obtain information on residence, symptom characteristics, demographics, medical/psychiatric comorbidity, and economics (Aims 1-3).

screen for psychiatric comorbidity and life experiences (Aims 1, 2, 4, 5).

Clinical Evaluation (one day) of:

all subjects classified, based on information from the Detailed Telephone Interview, as having CFS-like illness. Clinical evaluation is necessary to confirm classification as CFS (Aims 1-5).

comparison subjects for the purposes of identifying characteristics specific to CFS (Aim 2), to assess impairment and utilization of health services, and for derivation of an empiric case definition of CFS (Aim 4). These will include a random sample of subjects with Chronic Unwellness (not CFS-like), and a random sample of Well subjects. Persons with Chronic Unwellness are defined as being Unwell (with or without fatigue) reporting symptoms lasting for at least 6 months. The Well comparison group will be matched to CFS-like subjects by geography (metropolitan/urban/rural), sex, age and race/ethnicity. The Chronic Unwellness comparison group will be randomly selected (1:1 for CFS-like) from the same geographic area as CFS-like.

GCRC Studies. Finally, selected subjects participating in the Detailed Telephone Interview and those undergoing the Clinical Evaluations will be offered the opportunity to participate in future follow-up studies and in clinical research studies of fatiguing illness, which will be conducted at Emory University (Aim 5).

C.2 Methods

In this section we describe the data collection process from initial contact through GCRC studies. To facilitate communication throughout the study, we will host an Internet website that subjects can visit to learn more about the study, get answers to frequently asked questions, and ensure themselves of the study’s legitimacy.

C.2.a Advance and follow up letters. Prior to calling selected telephone numbers, advance letters will be sent to all households where the randomly generated telephone number could be matched to an address. These letters will notify respondents of the survey, explain its purpose and sponsor, and alert respondents to expect a call from a telephone interviewer.

Potential respondents who are initially reluctant to cooperate may be sent follow-up letters, emphasizing the importance of their participation in the study and giving them a toll-free telephone number to call to schedule or complete an interview. Four “conversion” letters were designed for this study. The first letter will be sent to households we have difficulty contacting by telephone for the Screening Telephone Interview. The second letter will be sent to households reluctant to complete the Screening Telephone Interview. The third letter will be sent to adult subjects reluctant to complete the Detailed Telephone Interview. The fourth letter will be sent to households where we are having difficulty reaching a subject selected for a Detailed Telephone Interview. These letters are appended.

C.2.b Telephone interview overview. Professional interviewers trained to administer the Screening and Detailed questionnaires will conduct all telephone interviews. All telephone interviews will be administered using computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI). The scripts that the telephone interviewers will use to contact respondents and conduct the interviews are included in the questionnaires. Informed consent statements are included in both the screening and detailed telephone interview questionnaires. The consent statements for both of these interviews will be administered as soon as the respondent is on the telephone. Telephone interviewers will be prepared to discuss any aspect of the respondent’s participation at greater length, including respondent rights and the telephone numbers of staff who can be contacted for more or different information. The interview will not proceed until the informed consent statement has been read, exactly as written, to each respondent, and all of the respondent’s questions have been answered.

We request a waiver of documentation for the verbal consent for the screening and detailed telephone interview questionnaires. 1) These questionnaires involve no more than minimal risk to the participants. The interview provides participants with a number to call (Dr. James F. Jones) if they think that they have been injured in this study. Dr. Jones (CDC Co-PI) has considerable clinical experience managing persons with CFS and other illnesses and is available at all times. He is backed up by Dr. Dimitris Papanicolaou (Emory Co-investigator). Previous versions have been administered with verbal consent in previous CDC studies of CFS (the Longitudinal Study of CFS in Wichita - IRB 1698) and the Pilot National Survey for CFS - IRB 2936) and there have been no adverse events. 2) The waiver or alteration will not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the participants. The verbal consent explains the study, the reasons it is being conducted, the nature of the questions, discusses possible risk, and informs the participant that she/he can choose not to answer any question or terminate the interview at any time. The interview also informs participants that they can call the CDC Deputy Director for Science at a toll free number if they have any questions about their rights in this study. Finally, individual potentially sensitive sections (e.g., exclusionary medical conditions and the life experiences screener) have introductory text informing the participant as to why the questions are being asked, their potentially sensitive nature, and that responses are completely voluntary and that he/she is free to not answer any question. 3. Because of the nature of random-digit-dialing telephone surveys, it is not practical to obtain written informed consent. 4) Whenever appropriate, participants will be provided with additional pertinent information after participation. The interview closes informing participants that if they have any questions about this research study they can contact Dr. Jones.

C.2.c Screening Telephone Interview. The objective of the Screening Telephone Interview is to identify subjects to interview in detail. A copy of the Screening Telephone Interview is appended. Screening will be similar to that in previous CDC population surveys for CFS.

The Screening Telephone Interview will contact a responsible adult informant for the selected households by asking for a respondent “who knows about the general health of the people in the household.” She/he will be asked to provide demographic information for all household residents. Household residents include: a] related family members residing in the living unit, b] unrelated people who share the housing unit (e.g., lodgers, foster children, wards, or employees), c] a person living alone in a housing unit, d] a group of unrelated people sharing a housing unit (e.g., partners or roomers), e] persons who are temporarily away (e.g., business, vacation, at boarding school, in the hospital). Persons not considered household members and who will not be enumerated include: a] students living away at college, b] persons who usually live elsewhere (e.g., “snowbirds” who live in a warmer climate during winter months but live elsewhere during the remainder of the year), c] persons living in group quarters (e.g., dormitories, nursing homes, military barracks).

We will also ask the respondent to identify Unwell household residents who have at least one core symptom of CFS for at least one-month duration (e.g., fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, problems with memory or concentration, and muscle or joint pain). Subjects selected for the Detailed Telephone Interview will be adults between 18 and 59 years of age and include all fatigued Unwell, a random sample of the Unwell not fatigued, and a random sample of the Well Subjects.

C.2.d Detailed Telephone Interview. The primary objective of the Detailed Telephone Interview is to identify Unwell subjects who fulfill criteria of the 1994 CFS Research Case Definition (i.e., have CFS-Like illness) and recruit them for clinical evaluation to confirm whether they have CFS and to obtain additional information needed for weighting during data analysis. The Detailed Telephone Interview will also 1) obtain data concerning characteristics of Well and Unwell respondents from metropolitan, urban, and rural populations; 2) obtain data from Unwell respondents for use in developing an empiric case definition (this includes information on mental health problems that may be related to the pathophysiology of CFS but are not exclusionary, such as anxiety disorders); 3) obtain data from Well and Unwell respondents for use in determining associations between life experiences and unwellness.

A copy of the Detailed Telephone Interview is appended. As with the Screening Telephone Interview, Detailed Interviews will be administered as CATI. We will attempt to complete the detailed interview immediately following the initial screening contact. If this is impossible, we will schedule an appropriate time.

We will conduct Detailed Telephone Interviews with all fatigued Unwell subjects between 18 and 59 years of age (i.e., those who could be CFS), randomly selected not fatigued Unwell, and randomly selected Well subjects between 18 and 59 years of age from within the specific geographic area. Sample size considerations are discussed below.

The detailed interview will:

Confirm the respondent is the individual who was identified by the household representative during the Screening Telephone Interview.

Document current residence.

Document demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, and ethnicity).

Document status of fatigue and other symptoms by a modified version of the CDC Symptom Inventory used in previous population surveys of CFS conducted by CDC. This will record presence or absence of specific symptoms, and if they have been present for at least 6 months.

Screen for medical conditions that exclude classification as CFS, by a modified version of the CDC screener used in the previous population surveys.

Screen for psychiatric conditions that exclude classification as CFS and comorbid conditions and experiences thought to be associated with CFS.

We will screen for exclusionary psychiatric disorders by an instrument we have compiled from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (First et al., 2002). Exclusionary psychiatric conditions identified by this instrument include: bipolar disorder, psychotic disorders, eating disorders, and alcohol and substance abuse. During the clinic visit, melancholic (and other) subtypes of depression will be determined in a detailed psychiatric interview.

Screen for psychiatric comorbidity and lifetime experiences.

Because psychopathology is highly prevalent in patients with CFS and may be related to the clinical course of CFS, we will assess lifetime and current psychiatric disorders that are not exclusionary for CFS, such as depression. We will include a screening for mood, anxiety (e.g., PTSD), and somatoform disorders to determine associations between psychopathology and CFS and to identify persons to recontact for future clinical studies at Emory University. The screening instrument was compiled from the SCID (First et al., 2002).

Because of the increasing evidence for a role of stress during development as a risk factor for CFS, and because of the evidence that symptoms of CFS are often exacerbated by acute life stress, we will include a detailed assessment of stress history in the present study. We will document lifetime experiences with the Childhood Traumatic Events Scale (CTES), the Recent Traumatic Events Scale (RTES) (Pennebaker and Susman, 1988), and four items of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) (Parker, 1979). The RTES measures major life events in the preceding 3 years.

Document occupation.

Gather information to estimate direct and indirect economic costs associated with CFS and chronic unwellness.

B ased

on information from the Detailed Telephone Interview, Well

and Unwell

subjects will be classified as having or not having an exclusionary

medical or psychiatric condition. Unwell

participants

will be classified as Chronically

Unwell if

symptoms have persisted 6 months or longer. Chronically

Unwell patients

with fatigue who do not have an identified exclusionary condition

will be classified as CFS-Like

if they fulfill criteria of the 1994 CFS research case definition.

Chronically

Unwell

participants (with or without fatigue) who do not meet criteria for

CFS

will be classified according to the nature of their symptoms and the

presence or absence of comorbid psychiatric conditions identified in

the interview.

ased

on information from the Detailed Telephone Interview, Well

and Unwell

subjects will be classified as having or not having an exclusionary

medical or psychiatric condition. Unwell

participants

will be classified as Chronically

Unwell if

symptoms have persisted 6 months or longer. Chronically

Unwell patients

with fatigue who do not have an identified exclusionary condition

will be classified as CFS-Like

if they fulfill criteria of the 1994 CFS research case definition.

Chronically

Unwell

participants (with or without fatigue) who do not meet criteria for

CFS

will be classified according to the nature of their symptoms and the

presence or absence of comorbid psychiatric conditions identified in

the interview.

At the conclusion of the Detailed Telephone Interview, the CATI program will determine subject eligibility for the clinical evaluation component. If subjects are eligible, the CATI program will display a script for the telephone interviewer to read to subjects informing them that they have been selected for the clinical evaluation component. Next, the CATI interviewer will be prompted to collect information to facilitate follow-up by clinics for scheduling purposes. Only respondents who did not have an exclusionary medical or psychiatric condition identified during the Detailed Telephone Interview will be eligible for clinic evaluation. We will attempt to clinically evaluate all respondents with CFS-like illness, an equal number of randomly selected Chronically Unwell not CFS-like (fatigued or not fatigued) subjects, and randomly selected Well subjects matched 1:1 to CFS-Like subjects by geography, sex, age, race/ethnicity.

C .2.e

Clinical Evaluation.

The objectives of the Clinical Evaluation are: 1) to classify

subjects as CFS,

Chronically

Unwell not CFS,

or Well

[Specific Aims 1-5]; 2) obtain detailed information pertinent to the

symptom domains of CFS in order to determine its characteristics

[Specific Aim 2] for use in deriving an empiric definition (Specific

Aim 4), as stratification variables [Specific Aim 2], and to identify

subgroups for participation in GCRC studies [Specific Aim 5]; 3)

obtain information to describe the economic impact of CFS (Specific

Aim 3), and; 4) obtain information concerning stress history, coping

mechanisms, and economic impact [Specific Aims 2 – 5].

.2.e

Clinical Evaluation.

The objectives of the Clinical Evaluation are: 1) to classify

subjects as CFS,

Chronically

Unwell not CFS,

or Well

[Specific Aims 1-5]; 2) obtain detailed information pertinent to the

symptom domains of CFS in order to determine its characteristics

[Specific Aim 2] for use in deriving an empiric definition (Specific

Aim 4), as stratification variables [Specific Aim 2], and to identify

subgroups for participation in GCRC studies [Specific Aim 5]; 3)

obtain information to describe the economic impact of CFS (Specific

Aim 3), and; 4) obtain information concerning stress history, coping

mechanisms, and economic impact [Specific Aims 2 – 5].

In summary, the following will be assessed during clinical evaluation: 1) physical and laboratory examinations for classification purposes; 2) saliva and blood collection for endocrine/immune function and future genetic studies; 3) questionnaires concerning symptomatology; 4) neurocognitive assessment; 5) psychiatric evaluation; 6) assessment of early and adult life experiences; 7) assessment of stress, coping and personality traits; 8) assessment of economic impact; and 9) assessment of health care utilization.

Each subject scheduled for Clinical Evaluation will receive a packet of materials prior to the appointment. This will include a letter describing the study, an informed consent document for review (8TH grade reading level), and a questionnaire to complete before arriving at clinic. The packet will also include 4 salivette devices and written instructions for the collection of saliva samples at home (see below). Upon arrival at the clinic, the coordinator will explain the study, answer any questions, and confirm eligibility for clinical evaluation. A subject will be ineligible for clinical evaluation if his/her body mass index (BMI) is 40 or greater, if the subject is not between 18 and 59 years of age, or if the subject has been pregnant within the past 12 months. Also, if the registered nurse determines the subject is suffering an acute illness (based on basal temperature and observation), the subject will be temporarily deferred until he/she is no longer contagious. Finally, a matched Well subject may be ineligible if his/her matching criteria (such as age, race, or ethnicity) no longer match the CFS-like subject with whom he/she has been paired.

Clinic coordinators will administer the informed consent to eligible subjects. Descriptive materials sent to subjects prior to Clinical Evaluation are appended (research instruments are appended separately).

The following table is an example of a work plan at clinic. All instruments are appended.

Exhibit 2.5

Clinic Flow for a Typical Clinic Day

|

||||

|

Subject 1 |

Subject 2 |

Subject 3 |

Subject 4 |

7:30 am |

Informed Consent |

Informed Consent |

|

|

8:00 am |

Blood Draw |

Blood Draw |

Informed Consent |

Informed Consent |

8:30 am |

BREAKFAST |

BREAKFAST |

Blood Draw |

Blood Draw |

9:00 am |

Medical & Meds Hx |

WRAT/CANTAB |

BREAKFAST |

BREAKFAST |

9:30 am |

Buffer |

|

WRAT/CANTAB |

Questionnaires |

10:00 am |

WRAT/CANTAB |

Medical & Meds Hx |

|

|

10:30 am |

|

Buffer |

Questionnaires |

WRAT/CANTAB |

11:00am |

Questionnaires |

Questionnaires |

Medical & Meds Hx |

|

11:30 am |

|

|

Buffer |

Questionnaires |

12:00pm |

LUNCH |

LUNCH |

Questionnaires |

Medical & Meds Hx |

12:30 pm |

SCID & PDQ4 |

Physical Exam |

LUNCH |

LUNCH |

1:00 pm |

|

|

SCID & PDQ4 |

Buffer |

1:30 pm |

|

Questionnaires |

|

Physical Exam |

2:00pm |

|

|

|