FINAL Supporting Statement Part A - Revised - 11-24-09

FINAL Supporting Statement Part A - Revised - 11-24-09.doc

Supporting Healthy Marriage (SHM) Demonstration and Evaluation Project - Wave 2 Survey

OMB: 0970-0339

SUPPORTING STATEMENT

FOR OMB CLEARANCE

PART A

SUPPORTING HEALTHY MARRIAGE DEMONSTRATION EVALUATION

WAVE TWO DATA COLLECTION

ADMINISTRATION FOR CHILDREN AND FAMILIES

OFFICE OF PLANNING, RESEARCH AND EVALUATION

November 24, 2009

Justification

A.1 Explanation of Circumstances That Make Collection of Data Necessary

The Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation (OPRE), within the Administration for Children and Families (ACF), seeks approval of changes to the previously approved follow-up survey (OMB No. 0970-0339) to conduct the second wave of data collection at 30-months after random assignment in the Supporting Healthy Marriage (SHM) evaluation. Conducting a second wave of data collection, as originally planned for the study, will allow for assessment of longer-term impacts of the intervention and collection of data on topics that are more pertinent to the study beyond the 12-month period. In addition to changes to the adult survey for wave 2, we also present justification for a new instrument and protocols to collect information from and about children/youth during wave 2.

Further, OPRE seeks approval for continued use of the original information collection instruments (adult survey and in-home couple and parent-child observations) beyond the April 30, 2011 expiration date to complete the wave 1 survey data collection. A nine-month extension through January 2012 is needed to complete the 12-month follow-up with the last enrolled research sample cohort.

In addition, we also request changes to respondent payment amounts to address lower than expected and needed response rates to the 12-month follow-up survey and in-home observation and request similar changes for wave 2.

The 12- and 30-month adult follow-up survey waves cover the same constructs of interest. About 80 percent of the questions on the adult survey are the same as in the first wave. Changes to the survey include modules to measure constructs that are more likely to show impacts at a longer-term follow-up period. Areas of new content include questions related to changes in the family structure, parenting, more in-depth measures of child outcomes for the focal child, material hardship experienced by the family, and health insurance coverage of the respondent and child. Exhibit A1.1 shows the specific survey question numbers that are the same as in the first wave or new and also identifies the youth survey and in-home child observation as new.

Background: OPRE contracted for an evaluation of SHM demonstration programs in September 2003; the evaluation will assess the effectiveness of marriage education and support services for low-income married couples. The evaluation utilizes a random assignment design, a baseline survey and two waves of follow-up data collection to measure program impacts in eight sites. A range of family, couple and child well-being outcomes will be measured. The evaluation also includes implementation analyses. The SHM evaluation is an important opportunity to examine the extent to which the demonstrations are meeting their objectives of improving couples’ marital relationships in an effort to improve broader individual and child outcomes in low-income families.

Exhibit A1.1 Differences Between First and Second Wave Information Collection |

||

Adult Survey Instrument Questions |

Same As 12-month survey |

New for 2nd Wave |

Contact Information |

X |

|

Section A: Household Structure |

|

|

A1-A5 |

X |

|

A6 |

|

X |

A7-A8 |

X |

|

A9 |

|

X |

A10-A15 |

X |

|

Section B: Marital Status and Stability |

|

|

B1-B7 |

X |

|

Section C: Marital Relationship Outcomes |

|

|

C1-C9 |

X |

|

C10 |

|

X |

Section D: Co-Parenting and Parenting |

|

|

D1-D3 |

X |

|

D4 |

|

X |

D5-D12 |

X |

|

D13-D14 |

|

X |

Section E: Non-Resident Parent Involvement |

|

|

E1-E2 |

X |

|

E3-E5 |

|

X |

E6-E8 |

X |

|

E9 |

|

X |

E10-E11 |

X |

|

Section F: Parental Well-Being |

|

|

F1-F2 |

X |

|

F3-F5 |

|

X |

F6-F7 |

X |

|

F9 |

|

X |

Section G: Physical and Domestic Violence |

|

|

G1-G3 |

X |

|

G4-G5 |

|

X |

G6-G9 |

X |

|

Section H: Child Outcomes |

|

|

H1-H2 |

X |

|

H3-H9 |

|

X |

Section I: Economic Security |

|

|

I1-I12 |

X |

|

I13-I16 |

|

X |

I17-I20 |

X |

|

I21-I24 |

|

X |

Section J: Participation in Services |

|

|

J1-J15 |

X |

|

Section K: Questions about Current Partner |

|

|

K1-K22 (Only asked to respondents who are living with or married to someone who was not their spouse when they first entered the study) |

|

X |

Section L: Locating and Demographic Information |

|

|

L1-L37 |

X |

|

Youth Survey |

|

X |

In-home Direct Child Assessment |

|

X |

A.2 How the Information Will Be Collected, by Whom, and For What Purpose

Wave 2 information will be collected in the same manner as was used in fielding the first wave. Information through surveys -- adult and youth -- will be collected primarily through computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI) with computer-assisted in-person interviews (CAPI) conducted when necessary.

All information will be collected by individuals who have been trained in the protocols for child assessment and survey administration. The adult survey will be fielded with both members of all couples in the research sample. The youth survey will be administered to the subset of focal children who were randomly selected from the children in the home when their parents first entered the SHM study and who are 8 years, 6 months old to 17 years at the time of the wave 2 follow-up. The youth survey will be administered through computer-assisted telephone interviews for those over 11 years old and through in-person interviews for those 8.5 to 11 years. The child assessments will be conducted in-person in research sample members’ homes.

Data collected will be used to determine the effectiveness of SHM marriage and relationship education programs in helping low-income married couples to develop stronger relationships and stable marriages and in improving adult and child well-being. As with the first wave of data collection, the second wave will be used to estimate intervention impacts on outcomes that are the primary and distal targets of the intervention and identify mechanisms that might account for these effects.

Data gathered through the youth survey also will be used: 1) to determine the effectiveness of relationship education programs in enhancing the well-being of participants’ children; and 2) to gather youth-reported information on some of the same constructs measured on the adult survey, namely the parent-child and mother-father relationships.

Direct child assessments will be conducted with a subset of focal children who are 8 years, 5 months old or younger at the wave 2 follow-up. The direct assessments will be used to assess children’s self-regulation and executive functioning, a key dimension of children’s broader abilities to regulate their emotions and behavior and, for younger children, language abilities. Prior non-experimental research suggests that aspects of marital conflict and the home environment are linked with children’s self-regulation.

EXHIBIT A2.1

OUTCOMES MEASURED DURING IN-HOME DIRECT CHILD ASSESSMENT

Outcome Domain |

Measures |

Mode |

Age of Child |

CHILD DIRECT ASSESSMENT |

|||

Language Development |

|||

Receptive language |

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test 4 |

Direct assessment of child |

2 years-4 years old |

Social and Emotional Adjustment and Self-Regulation |

|||

Self-regulation (behavioral regulation/motor control) |

Walk a Line Slowly (Murray and Kochanska 2002) |

Direct assessment of child |

2 year -3 years, 5 months old |

Self-regulation (inhibitory control/attention shifting) |

Item Selection/Attention Shifting Task (Blair & Razza, 2007) |

Direct assessment of child |

3 years, 6 months old-8 years, 5 months old |

Self-regulation (inhibitory control/attention shifting) |

Head to Toes Task (McClelland et al., 2004) |

Direct assessment of child |

3 years, 6 months old-8 years, 5 months old |

Interviewer assessment of self-regulation and behavioral adjustment |

Leiter-R Assessment |

Observer completes following the home assessment |

2 years-10 years, 11 months old |

Research Questions

The evaluation will use information collected to address the following key research questions. As compared to control group members who did not receive SHM services:

Do program group members demonstrate increased relationship quality with regard to relationships with their spouse and/or current new partner?

Do program group members experience greater stability in marital relationships?

Do the children of program group members live in more stable households?

Do program group members show improvement in both co-parenting and individual parenting?

Do the children of program group members show improved social, emotional, and behavioral adjustment, higher levels of self-regulation, and better early language skills?

Do program group members exhibit better mental and physical health?

Do program group members experience improved economic well-being (primarily due to reduced rates of family disruption)?

A.3 Use of Improved Information Technology to Reduce Burden

The CATI/CAPI technology that will be used to administer the adult and youth surveys is expected to reduce respondent burden. Computer programs enable respondents to avoid inappropriate and non-applicable questions.

A.4 Efforts to Identify Duplication

There is no similar information that can be used to assess outcomes of research sample members in the SHM study. We have attempted to use similar measures where appropriate in the SHM and Building Strong Families (BSF) evaluation, which is testing the effectiveness of relationship education and support services for low-income unmarried parents.

A.5 Burden on Small Business

No small businesses will be involved as respondents. Respondents are individuals.

A6. Consequences to Federal Program or Policy Activities in the Collection of Information is Not Conducted or is Conducted Less Frequently

Research indicates that low-income couples experience higher rates of marital dissolution than higher income couples. The consequences for children of family break-up are often quite negative. The longer-term data collection will provide the only source of information about the longer term impacts of the SHM family strengthening intervention. Failure to conduct the second wave of data collection would limit estimation of the impacts of the programs, and limit ACF’s ability to determine whether the programs met stated goals. The programs are intended to have long-term influences on couple relationships and marriages, which can affect child well-being. It will be important to understand if program impacts detectable at 12 months (the time of the first follow-up) are sustained and if new impacts emerge over time. For example, because the relationship status of low-income couples, in general, has shown to be unstable, couples together at the first follow-up may no longer be together at the second follow-up. If SHM has its intended effect, the relationship status pattern will be more stable in the program group than in the control group.

A7. Special Data Collection Circumstances

There are no special circumstances associated with this data collection.

A8. Federal Register Comments and Persons Consulted Outside the Agency

In accordance with the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995, ACF published a notice in the Federal Register announcing the agency’s intention to request an OMB review of data collection activities. The notice was published on March 23, 2009 in volume 74, number 54, page 12135 and provided a 60-day period for public comments. No comments were received.

The new measures for wave 2 were developed by evaluation researchers at MDRC and their sub-contractor, Child Trends, who are conducting the study for ACF. The researchers also consulted with Dr. Thomas Bradbury, University of California at Los Angeles; Dr. John Gottman, University of Washington; Drs. Philip and Carolyn Pape Cowan, University of California at Berkeley; Dr. Scott Stanley, University of Colorado at Denver; and Dr. Paul Amato, Penn State University.

A9. Justification for Respondent Payments

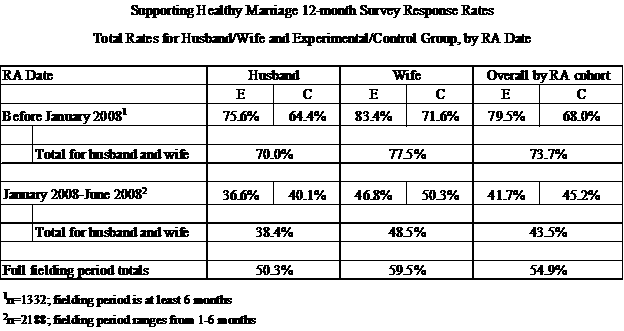

OMB previously approved respondent payments of $30 to adults responding to the 12-month follow-up. However, a lower than anticipated, and needed, response rate to date suggests that SHM sample members perceive the burden to be greater than the level of respondent payment offered. SHM study participants enrolled and released for survey through June 30, 2009 include 3,520 individual participants. By June 2009, 1,933 of these had completed the 12-month survey. The response rate is 74% for the portion of the sample that has been in the field for at least six months (a period expected to be generally sufficient to locate and contact respondents and complete surveys); this is lower than our 80% goal.

Concern about the overall response rate is compounded by disparities in response rates for experimental and control group members. Control group members are 10 percentage points lower than program group members. The differential in response rates between program and control group members is of key concern and has the potential to bias impact results. The following table illustrates these points.

For the earlier cohort, we see a clear differential in the overall response rates between program and control group members (11.5 percentage point differential). Our goal is to achieve an overall response rate of 80 percent, and less than a 5 percentage point differential between program and control group members. That we are falling notably short of these goals is of considerable concern and is the main issue that we aim to address by proposing an increase in the respondent payment for the survey effort.

Because the SHM evaluation targets a population with slightly higher incomes than many of the populations that we have studied in the past (e.g., married couples below 200% of poverty rather than single parents receiving welfare), it is likely that this current study population of men and women, many of whom are working, perceive their “cost” and burden of responding to the data collection to be greater than we assumed and reflected in our respondent payment level.

To address the substantially lower than needed survey response rate among control group members, we propose a respondent payment of $50 for this group. We propose to maintain the $30 respondent payment for program group members. These levels will be used for both the remainder of the Wave 1 (12-month) survey and for the Wave 2 survey. Further, we propose that respondents to the youth survey included in Wave 2 receive a payment of $25.

Respondent Payments for Observational Data Collection

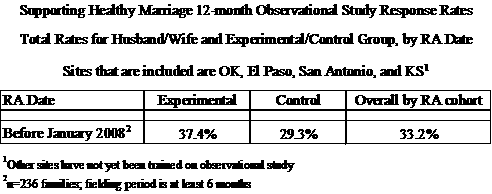

The trends described above with regard to lower than expected response rates for the survey data carry over to a higher degree with the observational study. Below, we provide a table showing response rates for the observational study by program and control group members, for the earlier RA cohort also shown in the previous table.

The response rates to date within the Wave 1 data collection for the observational study are of great concern; they hover between 29 and 37 percent, depending on research group. In addition, like the 12-month survey, controls are less likely to complete the observational study (about 8% point difference).

To have adequate power and unbiased impact results, we should achieve a response rate of 72 percent overall and at least a 60% overall response rate for the early cohort (that will continue to be followed-up to seek agreement to participate). That we are falling notably short of this goal, and the clear differential in response rates between program and control group members, causes considerable concern.

For the remainder of the Wave 1 (12-month) and for the Wave 2 observational component, we propose a payment of $25 for the first adult and $100 per couple if both members complete the observational component. For children included in the in-home observational component in Wave 1 and Wave 2, we propose a $10 payment level.

A10. Assurance of Confidentiality

There is no change in the procedures for protecting the privacy of study participants in the second wave of data collection. The Confidentiality Certification from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (see copy in Attachment 1) authorizes anyone connected with any information collections that are part of the SHM project to withhold the identity of subjects of the research. The Confidentiality Certificate protects the privacy of all research data gathered by researchers from MDRC, its subcontractors and cooperating agencies, and anyone else who may come into contact with research information about SHM study participants.

The procedures to protect data during information collecting, data processing, and analysis activities include the following:

No individual information will be cited as sources of information in prepared reports

To ensure data security, all individuals hired by the contractor are required to adhere to strict standards and sign an oath of confidentiality as a condition of employment

Individual identifying information will be maintained separately from completed data collection forms and from computerized data files used for analysis. No respondent identifiers will be contained in public use files made available from the study, and no data will be released in a form that identifies individuals.

A11. Questions of a Sensitive Nature

There are two new topics in the second wave data collection with adults that may be considered sensitive. The topics and justification are presented in Exhibit A11.1 below. The experience to date with sensitive questions as identified in the original submission indicates that non-response is less than 1 percent on those questions. We expect a similar rate of response on these additional questions.

Exhibit A11.1

JUSTIFICATION FOR NEW QUESTIONS IN SECOND WAVE – ADULT SURVEY

Question Topic |

Justification |

Whether the SHM partner is the parent of other children born after random assignment |

This question will enable us to examine SHM’s potential impact on multiple partner fertility. Multiple partner fertility has been shown to have negative consequences for child well-being, reducing financial and other support from parents and increasing children’s exposure to unrelated adults, which can increase the risk of child maltreatment (McLanahan and Sandefur 1994; Radhakrishna et al. 2001; Carlson and Furstenburg 2006; Harknett and Knab 2005). This question has been used on follow-up surveys conducted as part of the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study and the first follow-up Building Strong Families survey. In addition, it is important to collect updated information on the respondent’s previous child-bearing and household structure in order to have context in which to put other outcomes, specifically concerning the parent’s mental and economic well-being. |

Module of questions about the respondent’s relationship with a current romantic partner (whom he/she is living with and/or married to) |

We anticipate that some SHM participants will be separated or divorced from the spouse with whom they entered the study, and will have begun a relationship with a new partner by the time of the 30-month follow-up. We propose asking relationship quality questions about the participant's relationship with the new partner because we predict that program group members will carry over any skills learned in the SHM program to the relationship with the new partner. Hence, although they may be separated from their original spouse, respondents may have healthier relationships in the future due to participation in the SHM program. |

Below we identify constructs/topics included in the youth survey that may be considered sensitive even though they have been included in numerous other large-scale or national surveys.

EXHIBIT A11.2

JUSTIFICATION FOR SENSITIVE QUESTIONS: 30-MONTH YOUTH SURVEY

Question Topic |

Source |

Justification |

Delinquency

|

Sources: NLSY-97; National Survey of America’s Families (NSAF); America’s Promise Survey |

The SHM intervention may reduce children’s involvement in risky behaviors such as truancy, gang involvement, runaway incidents, vandalism, theft, and school suspensions and expulsions by promoting relationship stability, as divorce has been linked to delinquency in prior research (Price & Kunz, 2003). Additionally, research has found that healthy marriage programs have positive impacts on child delinquency (Lochman & Wells, 2004; Santisteban et al., 2003). We will assess school behaviors for focal children ages 8 to 17. |

Substance Abuse |

Source: America’s Promise Survey |

Studies have found that parental relationship conflict is positively associated with adolescent alcohol use (Baer, Garmezy, McLaughlin, & Pokorny, 1987; Hair et al., 2009b). Additionally, family cohesion was found to buffer the negative effects of father problem drinking on adolescent alcohol use (Farrell, Barnes, & Banerjee, 1995). In addition, interventions targeting the promotion of healthy marriage have been associated with reduced adolescent substance use (Lochman & Wells, 2004; Santisteban et al., 2003). |

Reactions to Interparental Conflict Perception of Parental Marital/ Relationship Quality Perception of Parent Co-Parenting Relationship |

Sources: Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale; Child’s View Questionnaire; NLSY-97; Schoolchildren and their Families Project; Security in the Interparental Subsystem (SIS), Conflict Tactics Scale, SHM baseline survey |

These items can be used to provide an independent perspective from the focal child on the quality of the parents’ marriage. In addition, these perceptions may serve as mediators for the children and adolescents. Studies using nationally representative samples have found that adolescents who perceive their parents’ relationships as supportive generally experience better physical and mental health and are less likely to engage in substance use and risky sex (Hair et al., 2009b; Kaye et al., 2009). Parents and their children tend to have similar though not identical perceptions of the parent marital relationship (Hair et al., 2009a), and interventions targeting this relationship have positive effects on both parents and children (Alexander, Pugh, Parsons, & Sexton, 2000; Kurkowski, Gordon, & Arbuthnot, 1999; Leung et al., 2003). Youth perceptions of, and reactions to, parental marital quality may be important predictors of various aspects of child well-being and good indicators of program success. |

Dating information (Romantic relationships) |

Source: Schoolchildren and their Families Project |

Though we were unable to find assessments of the effects of healthy marriage interventions for parents on adolescent romantic relationships, we expect that children may model behaviors observed in their parents’ relationships; therefore, it is important to assess the impacts of the SHM intervention on adolescents’ own romantic relationships. We also include items related to the parents’ knowledge and opinion of their adolescent offsprings’ relationships. These behaviors reflect another dimension of parent-child relationship quality and may indicate that offspring are developing more healthy relationships. |

Age of romantic partners |

Source: National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) |

Research has found that there are long-term consequences associated with having sexual partners three or more years older than one’s self. Specifically, girls with older sexual partners are more likely to acquire a sexually transmitted disease and to have a baby outside of marriage than girls with similar-aged partners (Schelar, Ryan, & Manlove, 2008). |

Relationship conflict |

Sources: NLSY-97; Supporting Healthy Marriage 12 month adult questionnaire |

Based on findings that parents condition their children in how to form and maintain relationships (Curtner-Smith, 2000), we expect that parent marital interactions may have a significant indirect impact on adolescent romantic relationships. |

Sexual activity |

Sources: NLSY-97 |

Many of the targeted goals of the SHM intervention including improved parent-child relationships and relationship stability have been found to reduce adolescents’ negative sexual behaviors. Specifically, high levels of parent supportiveness, awareness, and parent-child connectedness have been linked to delayed initiation of sex (Davis & Friel, 2001; Markham et al., 2003; Miller et al., 1997) and fewer sexual partners (Cleveland & Gilson, 2004; Donenberg et al., 2002; Jemmott & Jemmott, 1992; Miller et al., 1998). Furthermore, interventions geared at reducing interparental conflict have been found to reduce the number of adolescent sexual partners (Wolchik et al., 2002). |

A12. Estimates of Respondent Burden

Exhibit A12 presents estimates of the annualized reporting burden for extension of Wave 1 information collection. It also presents estimates for the second wave of data collection: the adult survey, the youth survey and the in-home observation. The burden estimates reflect the maximum burden expected assuming a 100 percent response. Time estimates are based on experience with the 12 month information collection activities.

Exhibit A12.1

Annual Burden Estimate

Instrument |

Number of Respondents |

Number of Responses per Respondent |

Average Burden Hours per Respondent |

Estimated Annual Burden Hours |

Adult Survey Wave 1 |

4,267 |

1 |

.83 |

3,542 |

Adult-Child Observation Study – Wave 1 |

2,448 |

1 |

.55 |

1,346 |

Total Wave 1 Burden |

|

|

|

4,888* |

|

|

|

|

|

Adult Survey Wave 2 |

4,267 |

1 |

.83 |

3,542 |

Youth Survey Wave 2 |

633 |

1 |

.50 |

317 |

Child Observation Study –Wave 2 |

1,329 |

1 |

.50 |

665 |

Total Wave 2 Burden |

|

|

|

4,524 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total Burden |

|

|

|

9,412 |

*Note: This figure is lower than that included in section A12 of the supporting statement submitted for the 12-month information collection, Wave 1 (OMB No. 0970-0339). The first estimate was erroneously calculated based on the full, rather than annual, burden using estimated response rates between 80% and 72%. The estimates in Exhibit A12 above reflect the annual number of respondents and assume a 100% response rate reflecting potential maximum burden hours for Wave 1 continuation beyond the current expiration date.

A13. Estimates of the Cost Burden to Respondents

Other than their time to complete the surveys or observation, there are no direct monetary costs to respondents. There is no annualized capital/startup or ongoing operation and maintenance costs associated with the information collection.

A14. Estimate of Costs to Federal Government

The total cost to the federal government for activities related to the second wave of data collection is estimated to be $5,740,478 over a three-year period, resulting in an annual cost of about $1,913,492.67.

A15. Changes in Hour Burden

The annual burden will decrease by 2,381 burden hours due to the original estimate being erroneously calculated based on the full, rather than annual, burden. The burden associated with wave 1 is a continuation, while the 4,524 burden associated with wave 2 is new.

A16. Time Schedule, Publication, and Analysis Plan

The schedule shown in Exhibit A16, below, displays the schedule and key dates for activities related to data collection, analysis, and publication.

Exhibit A16

Schedule and Key Dates for SHM Data Collection Activities

Activities and Deliverables |

Date of follow-up activity |

Follow-Up 1 Data Collection |

June 2008-January 2011 |

Follow-Up 2 Data Collection |

October 2009-July 2012 |

Data Analysis for Follow-Up 1 |

2011-2012 |

Reporting First Follow-Up |

2012 |

Data Analysis for Follow-Up 2 |

2012-2013 |

Reporting Second Follow-Up |

2013 |

The data will go through a rigorous series of tests for completeness and quality. Data from the second wave of follow-up will be merged with data from other sources, including data from the baseline and the first wave of follow-up, and the MIS data on program participation.

The SHM evaluation utilizes a random assignment analytic design. Although the use of a randomized design will ensure that simple comparisons of experimental and control group means will yield unbiased estimates of program effects, the precision of the estimates will be enhanced by estimating multivariate regression models that control for factors at baseline that all affect the outcome measures. Such impacts are often referred to as “regression-adjusted” impacts. Examples of factors that may affect outcomes are the sample members’ age, number of children, prior employment, and baseline levels of marital distress.

The same outcome domains will be examined in the impact analysis for the second wave of follow-up as are examined for the first wave. In drawing inferences about estimated impacts, standard statistical tests such as the two-group t-tests (for continuous variables such as an index of marital quality) or chi-square tests (for categorical measures, such as marital status) will be used to determine whether estimated effects are statistically significant. Since we will analyze multiple outcomes, we will explore the possibility of adjusting estimates to account for this fact, for example, by using a Bonferroni correction (Darlington, 1990) or other omnibus test (such as those discussed in Cooper & Hedges, 1994).

A17. Display of Expiration date for OM B Approval

All instruments will display the expiration date for OMB approval.

A18. Exceptions to Certification Statement

No exceptions are necessary.

References

Alexander, J. Pugh, C., Parsons, B., & Sexton, T. 2000. “Functional family therapy.” In D.S. Elliott (ed.), Blueprints for Violence Prevention (Vol. 3). Boulder, CO: Venture Publishing.

Baer, P.E., Garmezy, L.B., McLaughlin, R.J., & Pokorny, A.D. 1987. “Stress, coping, family conflict, and adolescent alcohol use.” Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 10: 449-466.

Blair, C., & Razza, R.P. 2007. Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development 78 (2): 647–63.

Carlson, Marcia J., and Frank F. Furstenberg, Jr. “The Prevalence and Correlates of Multipartnered Fertility Among Urban U.S. Parents.” Working Paper #03-14-FF. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, Center for Research on Child Wellbeing, January 2006.

Cleveland, H.H. and M. Gilson, 2004. The effects of neighborhood proportion of single-parent families and mother-adolescent relationships on adolescents' number of sexual partners. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 33(4): 319-329.

Cooper, H. & Hedges, L.V. (Eds.). 1994. Handbook of Research Synthesis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Curtner-Smith, M. E. 2000. Mechanisms by which family processes contribute to school-age boys’ bullying. Child Study Journal, 30, 169–186.

Darlington, R. B. 1990. Regression and Linear Models, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Davis, E.C. and L.V. Friel, 2001. Adolescent Sexuality: Disentangling the Effects of Family Structure and Family Content. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(3) 669-81.

Donenberg, G.R., et al., 2001. Holding the line with a watchful eye: The impact of perceived parental monitoring on risky sexual behavior among adolescents in psychiatric care. AIDS Education & Prevention, 14(2) 138-157.

Farrell, M.P., Barnes, G.M., & Sarbani, B. 1995. “Problem-drinking fathers on psychological distress, deviant behavior, and heavy drinking in adolescents.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36: 377-385.

Hair, E.C., Moore, K.A., Hadley, A.M., Kaye, K., Day, R.D., & Orthner, D.K. 2009a. “Combined marital quality and parent-adolescent relationship latent class analysis profiles.” Marriage & Family Review, 45, 2(3).

Hair, E.C., Moore, K.A., Hadley, A.M., Kaye, K. Day, R.D., & Orthner, D.K. 2009b. “Parent marital quality and the parent-adolescent relationship: Effects on adolescent and young adult health outcomes.” Marriage & Family Review, 45, 2(3).

Harknett, Kristen, and Jean Tansey Knab. 2005. “More Kin, Less Support: Multipartnered Fertility and Perceived Support Among Unmarried Parents.” Unpublished working paper. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania.

Jemmott, L.S. and J.B. Jemmott. 1992. “Family structure, parental strictness, and sexual behavior among inner-city black male adolescents.” Journal on Adolescent Research. 7(2):192-207.

Kaye, K., Hair, E.C., Moore, K.A., Hadley, A.M., Day, R.D., & Orthner, D.K. 2009. “Parent marital quality and the parent-adolescent relationship: Effects on adolescent and young adult sexual outcomes.” Marriage & Family Review, 45, 2(3).

Kurkowski, K.P., Gordon, D.A., & Arbuthnot, J. 1999. “Community-based skills vs. affectively oriented divorce education interventions for families in outpatient therapy.” Doctoral dissertation not submitted for publication.

Leung, C., Sanders, M.R., Leung, S., Mak, R., & Lau, J. 2003. “An outcome evaluation of the implementation of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program in Hong Kong.” Family Processes, 42, 4: 531-544.

Lochman, J.E., & Wells, K.C. 2004. “The Coping Power Program for preadolescent aggressive boys and their parents: Outcome effects at the 1-year follow-up.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 4: 571-578.

Markham, C., et al., 2003. Family connectedness and sexual risk-taking among youth attending alternative higher schools. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35(4) 174-179.

McClelland, M., Cameron, C., Connor, C., Farris, C., Jewkes, A., and Morrison, F. 2007. “Links between behavioral regulation and preschoolers’ literacy, vocabulary, and math skills.” Developmental Psychology, 43, 4: 947-959.

McLanahan, Sarah, and Gary Sandefur. 1994. Growing up with a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Miller, B.C., et al. 1997. The Timing of Sexual Intercourse among Adolescents: Family, Peer, and Other Antecedents. Youth and Society, 29, 1, 55-83.

Miller, K.S., et al. 1998. Patterns of condom use among adolescents: The impact of mother-adolescent communication. American Journal of Public Health, 88(10) 1542-1544.

Murray, K.T., & Kochanska, G. 2002. Effortful control: Relation to externalizing and internalizing behaviors and factor structure. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 503-514.

Price, C. & Kunz, J. 2003. Rethinking the paradigm of juvenile delinquency as related to divorce. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 39, 109-135.

Radhakrishna, A., Bou-Saada, I., Hunter, W., Catellier, D., and Kotch, J. 2001. “Are Father Surrogates a Risk Factor for Child Maltreatment?” Child Maltreatment, 6, 4.

Santisteban, D.A., Coatsworth, J.D., Perez-Vidal, A., Kurtines, W.M., Schwartz, S.J., LaPerriere, A., & Szapocznik, J. 2003. “The efficacy of Brief Strategic Family Therapy in modifying Hispanic adolescent behavior problems and substance use.” Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 1: 121-133.

Schelar, E., Ryan, S., & Manlove, J. 2008. “Long-term consequences for teens with older sexual partners.” Child Trends Fact Sheet. Washington, DC: Child Trends.

Wolchik, S.A., Sandler, I.N., Millsap, R.E., Plummer, B.A., Greene, S.M., Anderson, E.R., Dawson-McClure, S.R., Hipke, K., & Haine, R.A. 2002. “Six-year follow-up of preventive interventions for children of divorce: A randomized controlled trial.” Journal of the American Medical Association, 288, 15: 1874-1881.

| File Type | application/msword |

| File Title | SUPPORTING STATEMENT |

| Author | Nancye C. Campbell |

| Last Modified By | DHHS |

| File Modified | 2009-11-24 |

| File Created | 2009-11-24 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy