Appendixes A-3 FT Results

Att_ECLS-K (4226) Appendix A.3 EBRS FT results.doc

Early Childhood Longitudinal Study Kindergarten Class of 2010-2011

Appendixes A-3 FT Results

OMB: 1850-0750

TO: Alberto Sorongon, Karen Tourangeau, Christine Nord, WESTAT

FROM: Michelle Najarian, ETS

DATE: February 3, 2010

SUBJECT: Recommendation for Administration of the English Basic Reading Skills Assessment in the ECLS-K:11

The purpose of this memo is to provide a recommendation for administering the English Basic Reading Skills (EBRS) assessment in the ECLS-K:11. The original intent of the EBRS was to possibly serve as both a measure of basic reading skills in English for all test-takers, regardless of language, and as a language proficiency screener, identifying children to proceed with the remainder of the assessment in English. The types of analyses will be discussed, followed by the analysis results, recommendation, and next steps.

Analysis

We used two approaches in the initial analysis of the field test item data for the EBRS: classical item analysis and Item Response Theory (IRT), both providing information on item difficulty and the relationship of individual items to the construct as a whole

Classical item analysis includes the percent correct (P+) for each item, the correlation of performance on each item to performance on the test as a whole (r-biserial), omit rates, and distracter analysis (number and overall test performance for children choosing each response option for multiple choice items, or for children answering right/wrong for open ended items), as well as the internal consistency (alpha coefficient) for the set of items. Strengths of item analysis include the possibility of identifying weak distracters (i.e., options chosen by very few test takers), multiple keys (more than one correct or nearly correct answer), or items omitted by unusually high numbers of children. It also makes it possible to observe whether a response option designated as incorrect may be chosen by test takers who scored as high or higher, on average, on the test as a whole than did the group choosing the intended correct answer. This situation would result in a low or negative r-biserial, that could be an indicator of confusing or ambiguous language or presentation that may be causing children to misunderstand the intent of the question, or a different and equally correct interpretation not anticipated by the item writer.

A limitation of classical item analysis is that statistics are distorted by treatment of omits, whether they are included or excluded from the denominator of the percent correct. Including omits implicitly makes the assumption that ALL children who omitted an item would have gotten it wrong if they had attempted it, while excluding omits from P+ is equivalent to assuming that the same proportion of children who omitted would have given a correct answer. Neither assumption is likely to be true. Even if there are negligible numbers of omits, percent correct does not tell the whole story of item difficulty: all other things being equal, a multiple choice item will tend to have a higher percent correct than a comparable open ended item because of the possibility of guessing. R-biserials provide a convenient measure of the strength of the relationship of each item to the total construct, but they too are affected by omits. The P+ and r-biserial reported in classical item analysis contribute to an overall evaluation of a test item, but may be attenuated for items that perform well at one level of ability but not another.

Even with its limitations, however, classical item analysis provides an overview of the item quality and overall assessment consistency as well as details. It provides a look at the functioning of each individual response option, as opposed to IRT, which only considers whether the correct option was chosen. And when coupled with IRT analysis, which accounts for omits and the possibility of guessing, and shows the ability levels at which an item performs well, the result is a comprehensive assortment of statistics for item and assessment evaluation.

PARSCALE is the IRT program used for calibrating test takers’ ability levels on a common scale regardless of the assortment of items administered. The graphs (item characteristic curves) generated in conjunction with PARSCALE are a visual representation of the fit of the IRT model to the data. The IRT difficulty parameter ("b") for each item is on the same scale as the ability estimate (theta) for each child, allowing for matching a set of test items to the range of ability of sampled children. The IRT ("a") parameter, "discrimination" is analogous to the r-biserial of classical item analysis. IRT output includes a graph visually illustrating performance on the item for children at different points across the range of ability.

We evaluated item quality and potential for use in the EBRS by reviewing all of the available information for each item, including:

Difficulty: Matching the difficulty of the test questions to represent items measuring basic reading skills.

Use as a Language Screener: Evaluating the effectiveness of the items in clearly differentiating between children with and without enough English proficiency to proceed with the remainder of the English assessment.

Test Specifications: Targeting percentages of the basic skills and vocabulary content categories from the framework.

Psychometric Characteristics: Selecting items that do a good job of discriminating among achievement levels.

Linking: Having sufficient overlap of items across subsequent grade levels so that a stable scale can be established for measuring status and gain, as well as having an adequate number of items carried over from the ECLS-K to permit cross-cohort comparisons.

Assessor Feedback: Considering observations made by the field staff on the item functioning.

Measurement of Gain: Evaluating whether performance improved in subsequent years.

For example, an item with P+ = .90 (90% of children answering correctly) and IRT b=-2.0 would appear to be an easy item, potentially suitable for a test of basic reading skills. But a low r-biserial (below about 0.30) or a relatively flat IRT "a" parameter (below 0.50 or so), suggest a weak relationship between the item and the test as a whole. In other words, while the item is somewhat easy, it is not useful in differentiating different levels of basic reading skills because it is about equally difficult for low-ability and high-ability students.

Pooling Data and Samples

In order to measure each child's status accurately, it is important that each child receive a set of test items that is appropriate to his or her skill level. Selection of potential items brings together two sets of information: the difficulty parameters for each of the items in the pool, and the range of ability expected in the each round. Calibration of these two pieces of information on the same scale, so that they may be used in conjunction with each other, was accomplished by means of Item Response Theory (IRT) analysis. (In-depth discussions of the application of IRT to longitudinal studies may be found in the ECLS-K psychometric reports.)

IRT calibration was carried out by pooling the following datasets together:1

ECLS-K:11 fall kindergarten Spanish field test (approximately 1100 cases)

ECLS-K:11 fall kindergarten field test (approximately 450 cases)

ECLS-K:11 fall first grade field test (approximately 400 cases)

ECLS-K fall kindergarten national - items selected from general knowledge assessment (approximately 18,000 cases)

ECLS-K spring kindergarten national - items selected from general knowledge assessment (approximately 19,000 cases)

ECLS-K fall first grade national - items selected from general knowledge assessment (data collected only for a subsample of about 5,000)

ECLS-K spring first grade national - items selected from general knowledge assessment (approximately 16,000 cases)

The overlapping items shared by two or more datasets serve as an anchor, so that parameters for items and samples from different assessments are all on a common scale. Data from the ECLS-K:11 English and Spanish field test samples supply a link between the newly-developed field test items and the ECLS-K kindergarten/first grade assessments, enabling them to be put on the common scale necessary for direct comparisons. The large samples from the ECLS-K data collections also serve to stabilize parameter estimates that would be unreliable if only the small samples of the fall 2009 field test was available.

Pooling the datasets together also provides estimated values for the mean ability levels for each dataset on the same scale. Although the datasets are pooled together, the samples are treated separately to preserve the ability ranges of each dataset. Mean ability levels for each of the datasets above were calculated from the pooled sample.

Results

The original intent of the EBRS was to serve a dual purpose: 1) as a measure of early reading for all children, regardless of language, and 2) as a language screener, identifying children proficient enough in English to proceed with the remainder of the assessments in English. As such, we expected most of the items to function in such a way that the EBRS sample would show a probability of a correct response at the chance level or below, essentially showing a flat data curve across all ability levels. If that were the case, we would be able to differentiate between English and non-English speakers based on the probability of a correct response for each item. This information would be used to form a cut-score for English proficiency on the pool of items selected for the national administration.

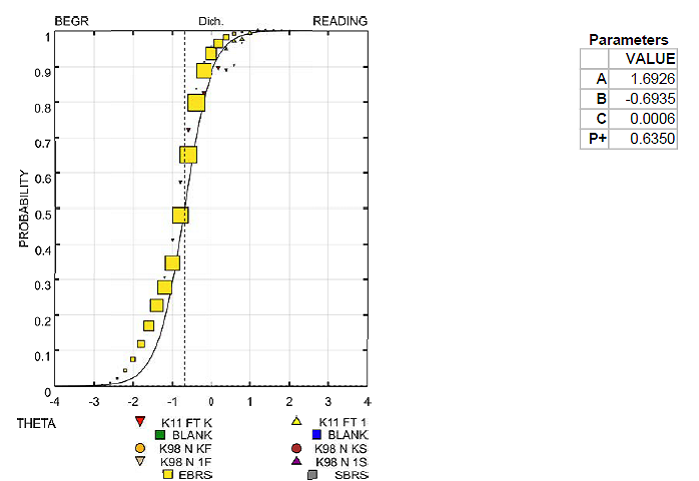

However, what we had expected was not what was observed, at all. Instead, what we found was that the Spanish sample tracked the English sample for nearly all items, as in the ICC in Figure 1 below.2 Here there is no differentiation between the Spanish and English speakers, as illustrated by the data which is common-functioning across all samples, and by the model tracking the data well. The result is that the items are very useful to measure early reading skills for all test-takers, regardless of language spoken and across the ability spectrum, but not as items to screen English proficiency.

Thus, a separate language screener is recommended to differentiate between English and non-English speakers. Our recommendation is to follow the same method as was done in the original ECLS-K study, which based a child’s English proficiency on the Pre-LAS score administered to those children whose school records indicated the child was an English Language Learner.

Recommendations

Upon our recommendation to administer a language screener, NCES responded by recommending an alternative approach, both approaches listed in Table 1 below. The table lists the scenarios we would possibly see in the national assessment: Spanish and English speakers scoring “low” on the EBRS and Spanish and English speakers scoring “mid” to “high” on the EBRS. Listed also are the different approaches to testing each of these groups. The pieces highlighted in yellow indicate the differences in how the assessments would proceed, comparing the two (ETS and NCES) approaches.

The major concern in the NCES approach is that low-ability English-speaking children, who would have continued in English with the original recommendation, will not continue any further in the NCES recommendation. Although it may not be likely that the low-scoring English speakers would respond correctly to many of the remaining routing and low-form second-stage items, gathering their responses on subsequent items does add to their ability estimation and the difficulty estimation of the items in the IRT calibration. So it is strongly recommended that the English-speakers who score low on the EBRS continue with the remaining routing items and appropriate second stage form in English prior to moving to the Math assessment (second group of yellow-highlighted text).

Upon further thought on the approaches, it was realized that if we do stop the low-ability English speaking children from proceeding with the English reading assessment, we would be limiting the number of items administered to that group, while not doing so with the Spanish-speakers, who would continue with the Spanish Basic Reading Skills (SBRS) items.3 So in this domain, the English-speakers would be treated like non-English non-Spanish speakers, who do not proceed with any additional reading items. This would result in the administration of fewer items to the low-ability English speakers, which is not comparable to what was done in the original ECLS-K study.

Therefore the recommendation still stands to administer a language screener, such as the Pre-LAS, to the Spanish-speakers in the sample. The administration of the Pre-LAS would be based on school records indicating that the child is a Spanish speaker, which is the same method used in the ECLS-K. NCES expressed concerns about using school records to define a child’s language. If school records are used to define whether or not a child receives the Pre-LAS, we would still be using the Pre-LAS (and not only school records) to screen children into the Spanish assessment. However, if we do not administer a language screener, we will be using school records only to screen low-ability children into the Spanish assessment, thus relying more heavily on school records, seeming contrary to the concerns.4

Next Steps

Upon receiving approval for these recommendations (or after subsequent revisions), we will proceed with selecting items for the EBRS. Delivery of the item selections will include a descriptive memo describing the analysis methods used, target ability and difficulty ranges, item overlap, and consistency with the framework.

Table 1: Comparison of Original and NCES Recommendations for the EBRS and Assessment Paths

Language Group |

Original Recommendation |

NCES Recommendation |

“Low” score on the EBRS items |

||

Spanish speakers, based on school records |

Administer the Pre-LAS Simon Says and Art Show items

|

Administer SBRS items

Administer Spanish-translated math assessment |

English speakers, based on school records |

Administer the remaining routing and appropriate second-stage forms of reading in English

Administer the math assessment in English |

Administer the math assessment in English |

“Mid” to “High” score on the EBRS items |

||

Spanish speakers, based on school records |

Administer the Pre-LAS Simon Says and Art Show items

|

Administer the remaining routing and appropriate second-stage forms of reading in English

Administer the math assessment in English |

English speakers, based on school records |

Administer the remaining routing and appropriate second-stage forms of reading in English

Administer the math assessment in English |

Administer the remaining routing and appropriate second-stage forms of reading in English

Administer the math assessment in English |

NOTE: Science and other assessments, as well as non-English/non-Spanish speakers are not included in the table above.

Figure 1: Sample item illustrating variability in the probability of a correct response across ability levels

1 The calibration focused on the kindergarten and first grade samples, and not the later grade levels, assuming the EBRS items would not be administered as a separate subtest beyond first grade.

2 The following discussion of the results utilizes item characteristic curves that show the IRT results for some sample items. On the graphs, the horizontal axis corresponds to the estimated ability level, Theta, of students in the sample. The vertical axis, Probability, is the proportion of test takers answering correctly at each ability level. The colored triangles and squares show the actual percent correct (P+) for the field test participants in different grades, while the smooth S-shaped curve shows the estimated percent correct at each ability level derived from the IRT model. The A, B, and C parameters that define the shape of the curve (left-to-right location; steepness; asymptotes) are computed by the Parscale program as the best fit to the actual item response data.

3 The Spanish Basic Reading Skills assessment contains items from the English reading assessment translated to Spanish that are likely to be equitable to the English versions of the items. More information on the SBRS is available in the memo on the SBRS of February 3, 2010.

4 An additional concern was raised regarding the differences in the number of items administered to English and Spanish speakers. It must be remembered that the number of items administered to a child varies depending upon which second stage form is administered, if discontinue rules are implemented, etc., in addition to whether only the EBRS items are administered. It is advantageous to administer additional items to a child in developing the item parameters and the ability score for the child; but what is not an issue is that in the sample, children receive different numbers of items. IRT takes this into account in its calibration.

| File Type | application/msword |

| File Title | TO: |

| Author | Michelle A Najarian |

| Last Modified By | #Administrator |

| File Modified | 2010-02-11 |

| File Created | 2010-02-11 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy