Supp Statement Part A_10Oct12

Supp Statement Part A_10Oct12.docx

Identifying Potentially Successful Approaches to Turning Around Chronically Low Performing Schools

OMB: 1850-0875

Identifying

Potentially Successful Approaches to Turning Around Chronically Low

Performing Schools

ED-04-CO-0025/0020

OMB Clearance Request for Data Collection

Part A

Table of Contents

OMB Clearance Request for Data Collection Part A 1

Administrative Data Analysis 11

Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission 15

1. Circumstances Making Collection of Information Necessary 15

2. Purposes and Uses of Data 16

3. Use of Technology to Reduce Burden 17

4. Efforts to Identify Duplication 17

5. Methods to Minimize Burden on Small Entities 17

6. Consequences of Not Collecting Data 18

8. Federal Register Comments and Persons Consulted Outside the Agency 18

10. Assurances of Confidentiality 20

11. Justification of Sensitive Questions 21

12. Estimates of Hour Burden 21

13. Estimate of Cost Burden to Respondents 22

14. Estimate of Annual Cost to the Federal Government 22

15. Program Changes or Adjustments 22

16. Plans for Tabulation and Publication of Results 22

17. Approval to Not Display OMB Expiration Date 23

List of Exhibits

Exhibit 1. Conceptual Framework 5

Exhibit 2: Construct Matrix 8

Exhibit 3. Main Study Components and Proposed Sample 10

Exhibit 4. Summary of Data Collection Procedures 10

Exhibit 5. Timeline for Piloting, Data Collection, and Data Analysis 16

Exhibit 6. Members of the Technical Working Group 19

Exhibit 7. Summary of Estimates of Hour Burden 22

OMB Clearance Request for Data Collection Part A

Introduction

The Institute of Education Sciences (IES), U.S. Department of Education (ED) requests clearance for the data collection for the study titled “Identifying Potentially Successful Approaches to Turning Around Chronically Low-Performing Schools.” This study reflects both the urgency for rapid school improvement and the lack of rigorous evidence to guide improvement efforts. The study seeks to identify schools that have achieved rapid improvements in student outcomes in a short period of time; illuminate the complex range of policies, programs, and practices (PPP) used by these turnaround (TA) schools; and compare them to strategies employed by not improving (NI), chronically low-performing (CLP) schools. The ultimate goal is to specify replicable PPP and combinations of PPP that hold greatest promise for further rigorous analysis. To this end, the study will collect data from school principals as well as school staff through a web-based and telephone survey and on-site interviews in selected schools.

Clearance is requested for the study’s design, sampling strategy, data collection, and analytic approach. This submission also includes the clearance request for the data collection instruments.

This document contains three major sections with multiple subsections.

Description of the Study

Overview, including research questions

Conceptual framework

Sampling design

Data collection procedures

Analytic approach

Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission

Justification (Part A)

Description of Statistical Methods (Part B)

Appendices containing the construct matrix, school survey, and case study interview protocol.

Description of the Study

Identifying Potentially Successful Approaches to Turning Around Chronically Low Performing Schools is a three-year study being conducted by the American Institutes for Research and its partners, Decision Information Resources, Policy Studies Associates, and the Urban Institute. The impetus for the study is the urgent need for rapid school improvement and the lack of rigorous evidence to guide improvement efforts.

The project comprises two substudies, referred to as Study I and Study II. Study I examines school performance trajectories for chronically low-performing (CLP) elementary and middle schools in multiple states to identify schools that have shown rapid improvement (designated turn around [TA] schools), schools that have shown moderate improvement (MI), and schools that are persistently nonimproving (NI).1 The primary goal of Study I is to identify a sample of TA and NI schools for which data on policies, programs, and practices (PPP) will be collected and analyzed in Study II.

When complete, Study I will provide useful information on the distribution of long-term performance trajectories that can be expected in a population of schools (i.e., all schools in a state). To date, very little systematic research has been done on the long-term performance trajectories of populations of schools. The few rigorous studies of school trajectories have focused on methodological issues (Raudenbush, 2004; Ponisciak & Bryk, 2005; Choi, 2005, 2009; Choi & Seltzer, in press; Choi, Seltzer, Herman, & Yamashiro, 2007).

Data collection and analysis in Study II will enable us to report the policies, programs, and practices and the educational and organizational changes found in turnaround schools. Study II will provide potentially important findings using a range of methods. By contrasting the survey responses of turnaround schools with those of chronically low performing schools in the moderate improvement and nonimproving categories, we will examine external and within-school policies, programs, and practices to determine whether some are more often associated with successful than with unsuccessful turnaround efforts. By analyzing administrative data on school staffing and teachers’ value added, we will learn the extent to which major staffing changes are associated with successful turnaround. Then, because survey responses and administrative data are necessarily limited in their depth and detail, through case studies we will explore the improvement histories of a sample of turnaround schools, contrasted with a sample of schools that have not improved, focusing on how their improvement strategies were introduced, supported, implemented, and sustained and the conditions that appear to have been favorable or unfavorable for turnaround.

Building on the identification of turnaround, moderate improvement, and nonimproving schools in Study I, Study II will employ quantitative and qualitative methods to gather data and perform comparisons addressing the following research questions:

RQ1. How did the policies, programs, and practices and combinations of policies, programs, and practices experienced or adopted differ across turnaround, moderate improvement, and nonimproving schools, and across elementary and middle schools?

RQ2. To what extent were turnaround, moderate improvement, and nonimproving schools characterized by changes in staff (e.g., new principal, amount of teacher turnover, entry of high-value-added teachers, exit of low-value-added teachers)?

RQ3. What differences existed between turnaround and nonimproving schools in the ways they implemented the policies, programs, and practices that were intended to improve their outcomes?

In addressing these research questions, this study builds on and extends current research on turnaround schools. By examining policies, programs, and practices in schools that have been empirically identified as chronically low performing schools, we go beyond the typical studies of turnaround schools, which tend to examine practices in schools that “beat the odds” (Kannapel & Clements, 2005; Carter, 2000; Barth et al., 1999). These studies do not necessarily focus on schools with the most intractable challenges or on schools with long histories of low performance. Perhaps more important, we include examination of credible comparison schools, without which a study cannot rule out the possibility that nonimproving schools have adopted the same practices as the turnaround schools.

Key phases of the study are the following:

An online and telephone survey of principals of a sample of 750 schools, stratified by performance trajectory (TA, MI, and NI) and level (elementary or middle). Survey responses will (1) identify or rule out exogenous explanations for apparent turnaround (e.g., conversion to a selective-admissions school or other substantial changes to the student population), and (2) identify policies, programs, and practices reportedly experienced or adopted by the school. Analyses of these data will address RQ1. In addition, by determining how many principals have served in the school over the relevant time period and whether former principals can be contacted, the survey will screen turnaround and nonimproving schools for the feasibility of onsite data collection through case studies. We expect to learn more about the dynamics of principal turnover when both sitting and former principals can be contacted.

Through analysis of administrative data, the research team will examine the movement of teachers into, out of, and across schools between 2002 and 2007 using state longitudinal administrative data. As student and teacher data can be linked, we will develop value-added measures for individual teachers and explore relationships between teacher characteristics (e.g., years of experience), turnaround processes (e.g., staff replacement), and outcomes. This analysis will address RQ2 and will also inform sampling for the case studies.

On-site case studies will be conducted in 24 TA schools and 12 NI schools (36 in total). Through site visits and qualitative analyses of interview and observational data, the research team will examine the “how” of the implementation of policies, programs, and practices, identifying conditions and strategies that increase the collective capacity of staff to provide quality curriculum, instruction, and assessment and thereby lift student achievement.

Study II will both identify the policies, programs, and practices that are found more often in TA schools than in less successful schools and provide in-depth detail on policies, programs, and practices implementation. It will address a major challenge for research in this field: chronically low performing schools, whether improving student performance or not, often report substantially similar policies, programs, and practices (Aladjem et al., 2006; Kurki et al., 2006; Turnbull, 2006). Prior research has linked school success not to the adoption of interventions but to the will and skill of staff (Cohen & Ball, 1999), the fit of approaches and developers with local circumstances (Datnow & Stringfield, 2000), and the level and quality of implementation (Berman & McLaughlin, 1978; Crandall et al., 1982; Stringfield et al., 1997; Kurki et al., 2006). This study reflects the following research-based assumptions about school change:

Sustained improvements in student outcomes are a function of change in the technical core of instruction: curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment (Elmore, 2004).

To turn around instruction across curriculum areas requires improvements in the organizational capacity of schools (Newmann, King & Youngs, 2001).

Teachers are the most important factor in improving the capacity of schools to influence student learning (Aaronson, Barrow, & Sander, 2007; Hanushek, 1986).

Certain operating features have been found to contribute to improvements in the technical core of schools: professional community, curriculum coherence, technical resources, principal leadership (Newmann et al., 2001), and order and safety (Bryk et al, 2010).

Certain structural features have been found to contribute to improvements in the technical core of schools: increases in instructional time (Smith, Roderick, & Degener, 2005), school and classroom size reductions (Bryk et al., 2010), and select comprehensive reform models (Aladjem et al., 2006).

The performance of schools is influenced by external infrastructures; specifically, their communities, support organizations, and the district, state, and federal context (Bryk et al., 2010).

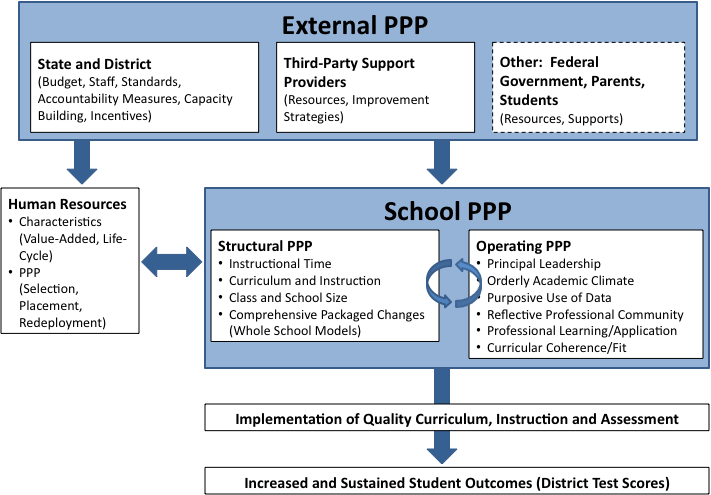

We summarize these ideas graphically in Exhibit 1, which presents the conceptual framework for this study. We elaborate on key aspects below.

External Policies, Programs, and Practices

School change is embedded in complex systems. Research has found that external policies can be critical to successful school improvement (Bodilly, 1998; Datnow & Stringfield, 2000; Kirby, Berends, & Naftel, 2001). A key feature of this study’s conceptual framework is its emphasis on external as well as school-level influences on learning outcomes. The top panel of Exhibit 1 identifies important elements of the external context for school turnaround.

Exhibit 1. Conceptual Framework

State and District. This study will examine district and state influences on school turnaround as noted in the box in Exhibit 1 labeled “District and State PPP.” Research describes the importance of district support and leadership stability in the school change process (Bodilly, 1998). School-level respondents link school change to focused district priorities, the absence of a district (budget) crisis, and a history of trust between the central office and the schools (Bodilly, 1998). Central office supports for schools come in the form of regulatory and financial practices: (a) providing schools with increased site-level control of mission, curriculum/instruction, budgets, positions and staffing, and (b) increased resource allocation for positions, materials, technology, planning time, and professional development. Fullan (2001) references three separate strands of district activities in support of school change: accountability measures, incentives (pressures and supports), and fostering capacity-building. These can also originate at the state level. Other means of state and district influence include governance structures, curriculum change, staff certification requirements, staff assignment regulations, policies regarding the length of school days and years; and performance requirements for students and schools including school closure and restart policies.

Third-Party Support Providers. Some might say that schools that are chronically low performing are so in part because they lack the capacity to improve significantly on their own. This study will examine the work of external agents in school change, as noted in the box in Exhibit 1 labeled “Third-Party PPP.” Assistance may come from outside vendors, universities, foundations, and other non-profits. It may focus on one or multiple aspects of improvement strategies.

Other Factors. The federal policy environment (Fullan, 2001) and the larger local community (parents, non-profit agencies, students background characteristics) influence school change efforts (Bryk et al. 2010). We include these as “Other Factors” in Exhibit 1 with a dotted (not solid) line to acknowledge that our data collection is not directly focused on these factors. .

Human Resource Policies, Programs, and Practices

Prior research has linked school success to staff capacity (Aaronson, Barrow, & Sander, 2007; Hanushek, 1986; Cohen & Ball, 1999). According to Fullan (2001: 117), educational change depends on “what teachers do and think—it‘s as simple and as complex as that.” Multiple agencies (states, districts, and schools) influence teacher hiring, deployment, and development policies, programs, and practices as indicated by the arrows converging on the box in the second panel of Exhibit 1 labeled “Human Resources.” Through analysis of administrative data, this study will examine the movement of teachers across schools with focused attention to the distribution of high value-added teachers. The study will also examine district and school policies, programs, and practices designed to influence teacher selection, deployment, redeployment, and development.

School-Level Policies, Programs, and Practices

In the second panel of Exhibit 1, alongside “Teacher PPP” we identify two types of school-level policies, programs, and practices designed to affect achievement outcomes. The first is labeled “Structural PPP” and the second is labeled “Operating PPP.”

“Structural PPP” refers to school and classroom policies, programs, and practices that have been identified as making a direct contribution to improvements in the technical core of schools. These include increases in instructional time (Smith, Roderick, & Degener, 2005), reductions in class and school size (Bryk et al., 2010), and select comprehensive reforms (Aladjem et al., 2006).

“Operating PPP” refers to policies, programs, and practices that have been shown to build staff capacity. These include investments in professional community, curricular coherence, technical resources, and principal leadership (Newmann et al., 2001). In looking at operating policies, programs, and practices we propose to focus on how school staff function in often taken-for-granted aspects of practice. We will focus, for example,on principal leadership practices given the centrality of leadership to turnaround (Herman et al., 2008; Duke, 2004, Leithwood et al., 2004; Turnbull, 2006); on the quality of teachers’ professional communities (McLaughlin & Talbert, 2006) with attention to relational trust (Bryk & Schneider, 2002), given the centrality of joint work on instruction; and on the level of coherence in multifaceted reform efforts (Newmann, Smith, Allensworth, & Bryk, 2001).

Temporal Dimension and the Dynamics of Change

The conceptual framework for this study indicates a focus on the role of the external environment, human resources, and school structures and operations in relation to instructional quality (curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment) and thereby outcomes. There is an important temporal dimension to the introduction, enactment, and abandonment or maintenance of policies, programs, and practices. In school-level case studies, we will gather and analyze retrospective data on the under-studied subject of the implementation histories of school turnaround efforts, contrasting successful efforts in a sample of TA schools with unsuccessful efforts in a sample of NI schools.

In looking at turnaround (or lack of turnaround) over time, we will assess the dynamics of change in a sample of schools. According to Datnow and Stringfield (2000: 199), “[R]eform adoption, implementation, sustainability, and school change more generally, are not processes that result from individuals or institutions acting in isolation from one another. Rather, they are the result of the interrelations between and across groups in different contexts, at various points in time.”

The external and school-level subsystems described above operate reciprocally. Just as effective teachers can, for example, be expected to increase curriculum cohesion, curriculum cohesion can be expected to increase teacher effectiveness. Bryk et al. (2010: 66) writes, “Only if mutually reinforcing activity occurs across these various domains is student learning in classrooms likely to improve.”

To understand how complex organizations change in the context of multiple influences, management scholars have borrowed theories from many disciplines. Van de Ven and Poole (1995) describe four basic theories: life cycle, teleology, dialectics, and evolution.

According to life-cycle theory a developing organization has within it an underlying form, logic, program, or code that regulates the process of change and moves the entity from a given point of departure to a subsequent end.

Teleology purports that purpose or goal is the final cause for guiding movement of an entity. Proponents of this theory view development as a repetitive sequence of goal formulation, implementation, evaluation, and modification of goals based on what was learned or intended by the entity.

In dialectical theory, stability and change are explained with reference to the balance of power between entities. Change occurs when opposing values, forces, or events gain sufficient power to confront and engage the status quo.

According to evolutionary theory, change proceeds through a continuous cycle of variation, selection, and retention. Variations are often viewed as emerging at random. Selection occurs principally through the competition for available resources. Retention involves forces (including inertia) that perpetuate certain forms.

No single theoretical perspective on change prevails. In case studies of the dynamics of school turnaround, we will therefore explore the following forces that may regulate change processes within schools:

Life-cycle forces at the level of the school as an organization

The role of purposive action and inquiry, including efforts to engage in cycles of goal setting and evaluation

The influence of multiple stakeholders within the school on program coherence and fit

Identification of productive variations that emerge in PPP implementation, and support for the maintenance of these variations

Both the conceptual framework and the construct matrix depicted in Exhibit 2 will guide data collection for Study II. The X’s indicate that the given data source will be used for the associated construct. The letter-number combinations (A1-D11) indicate survey item numbers.

|

Data Sources |

|||

Key Constructs and Indicators |

Study I |

School Survey |

Case Studies |

Administrative Data |

Screen and Validate Case Sample2 |

|

|

|

|

Non selective enrollment |

|

A8 |

X |

|

Stable enrollment policy |

|

A6 |

X |

|

Stable student demographics |

X |

A7 |

X |

|

Substantial resource infusions |

|

|

X |

|

Open since 2002 (continuously or not) |

X |

A2 |

X |

|

Grade span includes at least 2 grades 3-8 |

X |

A1 |

|

|

Principal turnover |

|

A3-5 |

|

|

External PPP |

|

|

|

|

Notification that the school is at risk of closing down |

|

B1a, b |

X |

|

Organizational changes at the district level |

|

B1d |

X |

|

Funding and resources for school improvement |

|

B1e |

X |

|

Collaboration with an external partner (e.g., a university or education management organization) |

|

B2 |

X |

|

Increased school autonomy |

|

B1c |

X |

|

Partnership with families and the community |

|

C1f |

X |

|

Human Resources |

|

|

|

|

Qualifications of teachers joining the school |

|

|

X |

X |

Value added of teachers joining the school |

|

|

|

X |

Little turnover of qualified staff |

|

C1c,d |

X |

X |

Teacher selection, assignment, and development policies and practices |

|

|

X |

|

School PPP |

|

|

|

|

Structural PPP |

|

|

|

|

Adoption and implementation of a comprehensive school reform |

|

B3 |

X |

|

Schedule changes (e.g., block scheduling, extended learning time) |

|

D5,6 |

X |

|

Reduced class size / student-teacher ratio |

|

D9 |

X |

X |

Project-based and cooperative learning strategies |

|

D3a,b |

|

|

Curriculum and instruction |

|

D3f,g |

X |

|

Tiered interventions |

|

D3c |

|

|

Integration of technology |

|

D3d |

X |

|

Revised student grouping strategies |

|

D3e |

|

|

Revised programs and policies to reduce behavior problems |

|

D11 |

X |

|

Use of data to inform instruction |

|

D4a-d |

X |

|

Operating PPP |

|

|

|

|

Trust and rapport among staff |

|

C1a |

X |

|

Non-committed teachers leaving school |

|

C1b |

|

|

High job satisfaction |

|

C1e |

|

|

Teacher collaboration and professional community |

|

C1a |

X |

|

Support for new teachers |

|

D7,D8 |

X |

|

Training for incumbent principal |

|

D1a |

|

|

Principal instructional leadership |

|

D1b |

X |

|

Distributed leadership |

|

D1c |

X |

|

Professional development |

|

D2a-c |

|

|

Instructional coherence |

|

|

X |

|

The main components of this study are presented in Exhibit 3 along with the proposed sample. A detailed description of our sampling design is provided in the Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission, Part B.

Exhibit 3. Main Study Components and Proposed Sample

Study Component |

Sample |

School Survey |

Principals of a random sample of 750 schools in Florida, North Carolina and Texas, stratified by performance trajectory (TA, MI, and NI) and level (elementary and middle). |

State Longitudinal Administrative Data |

Administrative records for the same 750 schools contacted for the school survey. These records detail the movement of teachers in/out and across schools between 2002 and 2007. |

In-Depth Case Studies |

A purposive sample of 24 TA schools and 12 NI schools (36 in total) in Florida, North Carolina, and Texas. |

The data collection for this study includes a telephone/web-based school survey, analysis of state longitudinal administrative records, and in-depth case studies. We have included all of the study’s data collection instruments in this submission. Exhibit 4 below presents a summary of our data collection procedures. The instruments for which we are requesting OMB clearance appear with an asterisk. A more detailed discussion of these procedures is provided in the Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission, Part B section of this package. Copies of the school survey and the case study staff interview protocol are included in the Appendix.

Exhibit 4. Summary of Data Collection Procedures

Study Component |

Data Sources |

Timeline |

School Survey* |

Web-based survey. Computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) with principals who have not responded to the web-based survey. Paper survey for principals preferring that format. |

Fall 2010 |

State Longitudinal Administrative Data |

Extant state administrative data on teacher demographics, teaching experience, and background, linked to student achievement data. |

Fall 2010 |

In-Depth Case Studies* |

Site visits to 36 schools in three states, including 30-60-minute interviews with district and school personnel and (where necessary) 15-20 minute follow-up telephone conversations to clarify field data. |

Winter 2011 |

Analytic approach

The school survey will both furnish data for analysis and also support the next steps in Study II. The survey will serve the following purposes:

Screen for exogenous explanations of TA. The survey will rule out TA schools where exogenous factors could explain outcomes.

Document policies, programs, and practices among chronically low-performing schools. The survey will address RQ1, gathering reports of the policies, programs, and practices experienced or implemented over the period from 2004 through 2007. These data will allow us to report on the extent to which particular policies, programs, and practices were considered significant in different categories of schools—TA, MI, and NI schools; and elementary and middle schools.

Identify schools in which case studies would be feasible. A few logistical and substantive factors would make schools suitable candidates for on-site study. For example, the current principal must be willing to participate in the study; the principal who was in place from 2004 to 2007 must be reachable for an interview; an NI school is a potentially informative site for a case study if it has adopted policies, programs, and practices in an effort to improve, but not if the principal cannot describe any improvement efforts implemented in the school. The survey will provide a simple assessment of these conditions.

Survey Analysis

The school survey will provide information about the variety of policies, programs, and practices implemented in schools during the period in which some of the sampled schools turned around. Survey data will be analyzed for two purposes. One is to identify the policies, programs, and practices reported in TA, MI, and NI schools and in elementary and middle schools (thus addressing RQ1). The other purpose is to select sites for intensive study.

For the identification of policies, programs, and practices, we will focus on those policies, programs, and practices shown in our conceptual framework that are most amenable to survey data collection. These policies, programs, and practices are found in the boxes labeled “External PPP,” “Staff,” and “Structural PPP.” Thus, we will tally the extent to which schools in the categories of interest (TA, MI, NI; elementary and middle) had substantial experience with policies, programs, and practices of the following types: external mandates, incentives, and resources; teacher recruitment and deployment; curriculum or pedagogy; added time; grouping; support services; comprehensive reform designs; and inter-organizational partnerships. In addition, although we would not expect a survey to yield in-depth information on operating policies, programs, and practices, we will analyze and report on the extent to which schools attempted to use approaches such as teacher professional development or common planning time in their improvement efforts.

The use of survey data in identifying case study schools is described in the section on the case study sample, below.

Although researchers have documented that teachers are the most important factor in increasing student outcomes (Aaronson, Barrow, & Sanders, 2007; Hanushek, 1986), most studies of TA schools do not adequately measure the effectiveness of the teaching staff. A unique feature of this study is our access to administrative data on teachers. In addition to information on credentials (e.g., certification, PRAXIS scores) and experience, we are able to calculate the effectiveness (value added to student tested performance) of individual teachers for all teachers with experience in the state because, for the states in this study, the teacher data are linked to student data. The research team will explore whether TA schools differ from MI and NI schools in the qualifications and effectiveness of the teaching staff and/or changes in (entry/exit/retention) effective staff (e.g., Loeb & Miller, in press; Xu, Hannaway, & Taylor, 2009; Sass, 2008; Clotfelter, Ladd, & Vigdor, 2007). We are particularly interested in the entry and retention of high value-added teachers and the exit of low value-added teachers (e.g., Boyd, Grossman, Lankford, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2009a, 2009b; Boyd, Lankford, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2005; Boyd, Lankford, Loeb, Rockoff, & Wyckoff, 2007; Hanushek & Rivkin, 2008; Goldhaber, Gross, & Player, 2007).

The policies, programs, and practices implemented in successful turnaround schools may affect change directly; however, turning around a school’s performance may also rely on indirect factors that aid in sustaining the improvement into the future. For instance, improved performance in a school may change the community’s perception of the school, which induces increased community and parental support in the school—reinforcing the school’s turnaround. One potentially important indirect factor in turnaround schools is the way the teacher labor market responds to dramatic changes in school performance. As part of the analysis, we propose to investigate how changes in a school’s teacher capacity may operate in relation to the turnaround. Thus, to address RQ 3, the research team will use the available statewide data to assess changes in staff capacity.

We plan to investigate two aspects of the teacher labor market that may indirectly contribute to creating or sustaining turnarounds in school performance: teacher mobility patterns around turnaround schools vis-à-vis nonimproving schools and changes in teacher value-added that may signal increased capacity in turnaround schools.

Studies have shown that more-qualified and more-experienced teachers tend to sort to relatively more successful or advantaged schools (Clotfelter, Ladd, & Vigdor, 2005; Hanushek, Kain, & Rivkin, 2004; Lankford, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2002). Schools that make a dramatic turnaround in performance may benefit from changes in sorting patterns that help sustain improvement. We plan to analyze changes in the relative attractiveness of schools through a difference-in-difference strategy, as modeled in Equation 1.

![]() (1)

(1)

This equation models differences in the characteristics of teachers at a given school as a function of differences in the schools observable characteristics, an indicator designating a school as a TA school, a variable indicating the post-turnaround period, and an interaction term combining the two indicators. The outcome of interest will be differences in one of several perceived signals of quality in the teacher labor market: average experience, percentage of teachers holding a post-baccalaureate degree, or percentage of teachers holding national board certification. If teacher capacity at turnaround schools is instrumental in sustaining the improvement, we would expect β4 to be positive. Beyond this difference-in-difference approach, we will also evaluate turnover rates for different segments of the teacher workforce (i.e., segmented by experience or degree) in TA schools before and after the turnaround period across schools, and compare these with those of non-TA schools.

To investigate the value-added of teachers in TA schools, we plan to use a similar difference-in-difference strategy in the set of teachers at a particular school. We encounter a problem, however, in that teachers’ estimated value-added measures are endogenous to the measures that are used to identify school turnaround. To overcome this endogeneity, we will use lagged value-added estimates of teacher quality. Investigating the dynamics of turnover jointly with teachers’ value-added estimates will show whether the improved performance in a school appears to be attributable to building human capital internally (developed within the current group of teachers) or whether turnaround relies more heavily on selecting a better pool of teachers into the school.

The results of this analysis will inform the strategy for the case studies: to the extent that teacher selection shows a strong association with turnaround, the procedure for sampling schools for case studies will include stratification by the amount of teacher turnover. This will ensure that the case study analysis can address the processes by which TA and NI schools have selected, inducted, and retained effective teachers, and the dynamics of change in professional community and collective capacity that follow an influx of new teachers.

The case studies will trace the dynamics of turnaround—the unfolding of events and actions by which turnaround in classroom instruction and other important supports for student learning is (or is not) perceived to be a consequence of policies, programs, and practices that were intended to improve the school. On-site, in-depth case studies will address a particularly vexing issue: How do TA and NI schools differ in their implementation of the policies, programs, and practices they have brought to bear on improvement? This question addresses the possibility that TA and NI schools adopt superficially similar policies, programs, and practices but differ in how practices are selected for adoption, introduced, and implemented. For example, past research demonstrates that when many improvement activities coexist in a school, the coherence of the different practices is a key to how well the practices, as a group, improve student outcomes (Newmann & Associates, 1996; Newmann, Smith, Allensworth, & Bryk, 2001). Variation in outcomes may also be a function of variation in the ways schools approach implementation of policies, programs, and practices (Marsh et al., 2006). We will examine these implementation issues through case studies.

We will explore in depth the improvement efforts undertaken in a sample of TA and NI schools, analyzing the ways in which they did (and did not) differ in external impetus for improvement, internal conditions that drive change, selection of policies, programs, and practices, and capacity development. We expect that some types of conditions and strategies can be identified as more characteristic of the TA schools than of the NI schools, and our aim in data collection and analysis will be to identify these with enough confidence to point the way to more systematic future inquiry.

Case Study Analysis

There are numerous ways to classify data. We will face the key analytic challenge of identifying, from among the many events and perceptions described in the schools, preferred categories and subcategories for the presentation of policies, programs, and practices and school improvement. Our procedures involve the site visitors in compiling the data from each school under the guidance of lead analysts. Cross-site analysis will be an iterative process of identifying tentative generalizations, testing them against all the available data, and refining them.

Our conceptual framework will suggest possible types of patterns related to the supports and impediments for school turnaround and to the dynamics of change. However, we also expect surprises in the data, and the analysis team will test tentative conclusions against the evidence through the following procedures.

Analyses of case study data will proceed in five stages: (1) summaries of interview themes completed while in the field, (2) case study reports, and (3) coding of case study reports, (4) cross-case analyses, and (5) data displays.

First, concise preliminary summaries of completed interviews will be completed–approximately two pages entered into a standard data capture template–with bulleted list of key themes from each interview and observation. Leaders of Study II will review these write-ups in detail, noting text that needs clarification or elaboration. This first phase will enable us to identify emergent themes and gaps in data collection and will generate possible codes.

Second, site visit teams will develop case studies mapping verbatim quotes onto study themes. Senior staff will review case studies against completed interviews to ensure that researchers are entering data in a consistent manner, with comparable levels of detail. Senior staff will sift through the data to identify the external and school-level PPP perceived to have been critical for the successful implementation of school TA efforts, and the differences in TA and NI schools with regard to each of these. Phase-two analysis will involve writing section headings that describe perceived turnaround dynamics, supports, and impediments. After tentative categories are established, site-by-site, a complete list of headings will be made and classified.

Third, select members of case study teams will code case study reports against classification headings using a qualitative analysis software program (most likely, Nvivo). This software package will enable the research team to adopt a structured system for organizing and categorizing data, identifying segments of interview text that relate to a specific topic, and comparing responses across case study sites and districts. When the coding is completed, analysts will run preliminary queries to identify overall trends and patterns in the data.

Fourth, select members of case study teams will conduct cross-case analyses to identify emergent themes, associations, and processes. The analysis will include comparison of topics across the schools, districts, and states in the case study sample. We will develop tables and case-ordered matrices that will allow us to identify themes as they emerge and to highlight promising practices. Cross-case analyses will enable us to explore the relationship between sets of variables, such as school-level contextual features–urbanicity, size–and the consistency and stability of the turnaround strategies. Likewise, when comparing cases across districts with different systemic challenges–for example, persistent shortages of high-caliber teachers–we can better gauge the effectiveness of strategies to improve educators’ qualifications.

Fifth, we will determine the most appropriate level of specification to use in reporting the data. The final set of headings will be clear and meaningful, parallel in content and structure, and of the same magnitude of importance.

Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission

Justification (Part A)

1. Circumstances Making Collection of Information Necessary

Chronically low-performing schools have concerned policymakers and educators for years. Under Section 133 of Public Law 107-279 (The Education Sciences Reform Act 2002), the duties of the National Center for Education Research of the Institute of Education Sciences include carrying out scientifically valid research that provides reliable information on educational practices that support learning and improve academic achievement and access to educational opportunities for all students. Recently, state and federal accountability requirements have quantified one aspect of this problem. The AIR-conducted analyses for the National Assessment of Title I found that 12% of all schools (11,648 schools) were identified for improvement (IFI) in 2005–06. Almost one-quarter of these schools (2,771 schools) were Title I schools with a history of failing to meet state achievement standards for 4 to 6 years (Stullich, Eisner, & McCrary, 2007). These schools face the greatest challenges in turning around student achievement, and the number of schools being identified for improvement will increase as states raise the annual objectives for school performance (LeFloch et al., 2007). The issue of chronically low-performing schools is much broader than just schools failing to make adequate yearly progress.

The pressure to meet accountability deadlines has motivated many policymakers to seek fast ways to improve schools. Beyond accountability pressures, policy makers are increasingly emphasizing the need to turn around chronically low-performing schools for the sake of the students in the schools, independent of accountability considerations. Empirical research—much of it correlational—on school reform has offered important findings and promising strategies. Studies of effective schools identified common school-level factors such as consensus on school goals, high expectations for student achievement, principal leadership, and monitoring of student progress (Gamoran, Secada, & Marrett, 2000). Researchers also found relationships between organizational conditions—teacher teams, teacher collaboration, principal support for teachers, flexible scheduling—and student achievement (Bryk & Driscoll, 1988; Lee & Smith 1995, 1996). Research on the social organization of schools found that professional community—shared responsibility, collective decision making, common values—when focused on student learning relates to instruction and achievement (Newmann & Associates, 1996). Human resources such as teacher knowledge and principal leadership, especially, seem related to improved instruction (Gamoran et al., 2000).

One “bottom line” emerges from this descriptive research on effective schools and organizations: instruction matters most, and other changes (e.g., leadership, resources) also relate to student achievement when they facilitate changes in instruction (Gamoran et al., 2000). However, although this research suggests that changes in teaching and school organization can improve student learning, it does not consider how these individual practices operate together. School staff have difficulty implementing multiple, unrelated interventions well, and isolated interventions tend to be less related to student outcomes than a concerted, coordinated approach (Stringfield et al., 1997).

Recent exploratory work suggests that some schools achieve quick, dramatic improvement, contrary to the prevailing wisdom of school improvement (Herman et al., 2008; Murphy & Meyers, 2007; Rhim, Kowal, Hassel, & Hassel, 2007; Calkins et al., 2007). Although research provides suggestive evidence about PPP that may promote TA, we have little rigorous evidence for many of these PPP. Most important, we have almost no scientific evidence about how to implement PPP quickly or in what combination to achieve rapid and dramatic improvement. We do not know whether PPP that work in elementary school also work in middle school. We know almost nothing about sustainability of improvement, especially when achieved quickly. The overarching objective of this study is to begin to understand, scientifically, how turnaround (TA) schools work. We plan to describe the range of PPP in CLP schools and identify those PPP and combinations of PPP in TA schools with the most potential for further replication and study in future impact studies.

Exhibit 5 expands on the timeline presented in Exhibit 4.

Exhibit 5. Timeline for Piloting, Data Collection, and Data Analysis

Study Component |

Spring 2010 |

September 2010 |

October 2010 |

November 2010 |

December 2010 |

Winter 2011 |

Spring 2011 |

School Survey |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pilot |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Recruitment |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Data collection |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

Data analysis |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In-Depth Case Studies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pilot |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Recruitment |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Data collection |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

Data analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

Data collection and analysis in this study will enable ED to identify policies, programs, and practices associated with turnaround that could be evaluated for evidence of causal impacts on student achievement. This study will provide important findings using a range of methods. By contrasting the survey responses of TA schools with those of chronically low-performing schools in the moderate-improvement and not-improving categories, we will identify external and within-school PPP that are more often associated with successful than with unsuccessful turnaround efforts. By analyzing administrative data on school staffing and teachers’ value added, we will learn the extent to which major staffing changes are associated with successful turnaround. Then, because survey responses and administrative data are necessarily limited in their depth and detail, we will explore in depth the improvement histories of a sample of turnaround schools, contrasted with a sample of schools that have not improved, focusing on how their improvement strategies were introduced, supported, implemented, and sustained and the conditions that appear to have been favorable or unfavorable for turnaround. The ultimate purpose of the data collection is to identify potentially successful approaches to turning around chronically low-performing schools that can later be studied using more rigorous methods. Not enough is yet known about how chronically low-performing schools turn around to undertake more rigorous evaluations at this time.

3. Use of Technology to Reduce Burden

We will use a variety of information technologies to maximize the efficiency and completeness of the information gathered for this evaluation and to minimize the burden the evaluation places on respondents at the district and school levels:

Existing records of administrative data will be collected electronically.

To further streamline the data collection process and reduce burden on survey respondents, principals will be given the choice between a web-based version of the survey or a Computer-Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI) version of the survey. In only very few cases, we anticipate that principals will complete a paper version of the survey.

A toll-free number and email address will be available during the data collection process to permit respondents to contact interview staff with questions or requests for assistance. The toll-free number and email address will be included in all communication with respondents.

4. Efforts to Identify Duplication

The basic question posed by this study has not been previously addressed. While many studies have examined the characteristics of effective schools, and a few have investigated turnaround schools (US Department of Education, 2010), none have sought specifically to identify policies, programs, and practices that can themselves be subjects for future effectiveness studies.

We have developed advanced statistical methods for identifying potential school sites with a high likelihood of being true turnarounds. In this way, we will not needlessly burden schools from which we are unlikely to gather useful data. We also plan to use extant administrative data on staff capacity which will greatly reduce the number of questions asked, thus reducing respondent burden, minimizing duplication of previous data collection efforts and information, and increasing data quality.

5. Methods to Minimize Burden on Small Entities

No small businesses will be involved as respondents. Schools will be the focus of our study and as such will be subjected to some burden. We have sought to minimize this burden through a number of means.

We have carefully targeted schools for inclusion in the study (using extant administrative records) so that we can focus on those that will yield the most useful information. We thereby have excluded many schools that might otherwise have been included but yielded relatively less useful data.

We will use extant administrative data for a major set of analyses of high policy importance (i.e., teacher effectiveness and mobility) and thereby eliminated all burden on schools.

We will use technology to administer a short survey to principals thereby reducing the burden on principals to deal with a paper and pencil survey or a long overly broad survey.

We will use both administrative data and the survey data to select our sample of case study schools and thereby, again, focused our investigation on those schools most likely to yield valuable data.

We have kept our case study protocol short and focused on the data of most interest and will speak with relatively few staff at the subject schools.

6. Consequences of Not Collecting Data

Existing research on school turnaround and school reform have focused on the types rather than processes and enabling factors that separate successful from less successful efforts. Failure to collect the planned data through this study would prevent a picture of how chronically low-performing schools implemented practices that led to success. For example, it would limit our ability to identify external and within-school PPP that are more often associated with successful than with unsuccessful turnaround efforts. Additionally, the consequences of not collecting the data include an inability to examine how practices combined together in specified contexts can become effective approaches to school improvement. As such, the information gained through this study can inform national, state, and local efforts to better guide and support chronically low-performing schools.

None of the special circumstances listed apply to this data collection.

8. Federal Register Comments and Persons Consulted Outside the Agency

Comments will be solicited via a 60-day notice and a 30-day notice to be published in the Federal Register to provide the opportunity for public comment.

Throughout the duration of this study, we will draw on the experience and expertise of a technical working group that provides a diverse range of experiences and perspectives, including researchers with expertise in relevant methodological and content areas. The members of this group, their affiliation, and areas of expertise are listed in Exhibit 6.

Exhibit 6. Members of the Technical Working Group

TWG Member |

Professional Affiliation |

Area(s) of Expertise |

|---|---|---|

Robert Balfanz |

Johns Hopkins University |

Quantitative analysis, school reform |

Adam Gamoran |

University of Wisconsin-Madison |

Survey research development, case studies, qualitative analysis, quantitative analysis, school reform |

David Heistad |

Minneapolis Public Schools |

Program evaluation, school reform |

David Kaplan |

University of Wisconsin-Madison |

Quantitative analysis, school reform |

Henry May |

University of Pennsylvania |

Quantitative analysis, school reform |

Sam Redding |

National Center on Innovation and Improvement |

Implementation of policies, programs, and practices in schools, school reform |

Joan Talbert |

Stanford University |

Case studies, qualitative analysis, survey research |

The school survey is the sole source of data for RQ 1. This increases the importance of achieving a high response rate. Given the length of the survey, ED’s experience on prior studies suggests that it is necessary to provide a modest incentive of $50 to each principal to participate in the survey and to compensate the principal for the time to schedule and complete the survey. Our experience has demonstrated that a modest incentive such as this greatly reduces the costs of follow up with non-respondents. Refreshments will be provided to participants in the case study schools. Case study schools also will be offered $250 to participate. This amount is intended to compensate the schools for the time it takes the principal, teachers, and staff to provide us with information and accommodate our needs throughout the site visits. No other payments or gifts are planned for this study.

Other recent federal data collections have paid participants to ensure successful recruitment and data collection efforts. Our review of several of these data collections suggest payments in the range of $20 to 25 for teacher surveys, $35 for school surveys, and as much as $45 for teacher participation in focus groups (see for example, (03262) 1850-0832-v.1 Conversion Magnet Schools Evaluation, (03361) 1850-0838-v.1 A Study of the Effectiveness of a School Improvement Intervention, (03328) 1850-0842-v.1 Evaluation of the Quality Teaching for English Learners (QTEL) Program). In addition, the Longitudinal Assessment of Comprehensive School Reform Implementation and Outcomes (LACIO) paid schools participating in case studies $200, (03327) 1875-0222-v.3.

The underlying principle used to justify payments to study participants is that the payment ought to correlate closely to the participants’ labor market wages. The proposed payments for this study correlate more closely to real market wages than the assumptions used in prior data collections. According to the latest data available from the Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2008, the mean annual wage of elementary school teachers was $52,240. Assuming a 160 day school year, this is equal to an hourly wage of $40.81 (http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes252021.htm). The mean annual wage of elementary and secondary school administrators was $86,060. Assuming a 220-day year for administrators (11 months), this is equal to an hourly wage of $48.90 (http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes119032.htm). In this context, a payment of $50 to principals and $250 to schools seems wholly appropriate.

10. Assurances of Confidentiality

As research contractors, the research team is concerned with maintaining the confidentiality and security of its records. The team will ensure the confidentiality of the data to the extent possible through a variety of measures. The contractor’s project staff has extensive experience collecting information and maintaining confidentiality, security, and integrity of interview and survey data. The team has worked with the Institutional Review Board at American Institutes for Research to seek and receive approval of this study. The following confidentiality and data protection procedures will be in place:

Project team members will be educated about the confidentiality assurances given to respondents and to the sensitive nature of materials and data to be handled. Each person assigned to the study will be cautioned not to discuss confidential data.

Data from the school survey, administrative records, and case study schools will be treated as follows: respondents’ names, addresses, and phone numbers will be disassociated from the data as they are entered into the database and will be used for data collection purposes only. As information is gathered from respondents or from sites, each will be assigned a unique identification number, which will be used for printout listings on which the data are displayed and analysis files. The unique identification number also will be used for data linkage. Data analysts will not be aware of any individual’s identity.

We will shred all interview protocols, forms, and other hardcopy documents containing identifiable data as soon as the need for this hard copy no longer exists. We will also destroy any data tapes or disks containing sensitive data.

Participants will be informed of the purposes of the data collection and the uses that may be made of the data collected. All case study respondents will be asked to sign an informed consent form approved by AIR’s IRB. Consent forms will be collected from site visitors and stored in secure file cabinets at the contractor’s office in Washington, DC.

We will protect the confidentiality of survey respondents and all case study participants who provide data for the study and will assure them of confidentiality to the extent possible. We will ensure that no district- and school-level respondent names, schools, or districts are identified in reports or findings, and if necessary, we will mask distinguishing characteristics. Responses to this data collection will primarily be used to summarize findings in an aggregate manner and secondarily to provide examples in a manner that does not associate responses with a specific individual or site. We will not provide information that associates responses or findings with a school or district to anyone outside of the study team except if required by law.

While most of the information in the final report will be reported in aggregate form, as noted above, there may be instances where specific examples from the case study data will be utilized to illustrate “best practices”. In these instances, the identity of the case study site will be masked with a pseudonym and efforts will be made to mask distinguishing characteristics.

All electronic data will be protected using several methods. We will provide secure FTP services that allow encrypted transfer of large data files among contractors. This added service prevents the need to break up large files into many smaller pieces, while providing a secure connection over the Internet. Our internal network is protected from unauthorized access utilizing defense-in-depth best practices, which incorporate firewalls and intrusion detection and prevention systems. The network is configured so that each user has a tailored set of rights, granted by the network administrator, to files approved for access and stored on the LAN. Access to our computer system is password protected, and network passwords must be changed on regular basis and conform to our strong password policy. All project staff assigned to tasks involving sensitive data will be required to provide specific assurance of confidentiality and obtain any clearances that may be necessary. All staff will sign a statement attesting to the fact that they have read and understood the security plan and ED’s security directives.

11. Justification of Sensitive Questions

No questions of a sensitive nature will be included in this study.

The estimated hour burden for the data collections for the study is 743 hours. Based on average hourly wages for participants, this amounts to an estimated monetary cost of $28,557. Exhibit 7 summarizes the estimates of respondent burden for study activities.

The burden estimates associated with the principal interviews is 383 hours. This figure includes:

Time associated with preparing for the school survey administration, including gaining cooperation, providing information about the study, providing contact information for former principals (if applicable) and scheduling an interview (if applicable) (10 minutes /respondent); and

Time for to participate in a 25-minute CATI or web-based survey.

The burden estimate associated with the case studies is 360 hours. This burden estimate includes:

Time for a district official to participate in a 30-minute interview;

Time associated with identifying school staff to participate in interviews or focus groups (1 hour/school); and

Time associated with gaining cooperation from school staff, which will include time for school management to review study information, request additional information or clarification as needed, identify and recruit participants for interviews, and coordinate meeting logistics (e.g., locating a meeting room) (2 hours/school); and,

Time for school staff in 36 schools to participate in a 1-hour interview.

Exhibit 7. Summary of Estimates of Hour Burden

|

Task |

Total Sample Size |

Estimated Response Rate |

Number of Respondents |

Time Estimate (hours) |

Total Hour Burden |

Hourly Rate |

Estimated Monetary Cost of Burden |

School Survey |

Preparing for Administration |

750 |

100% |

750 |

0.17 |

131 |

$45 |

$5,625 |

Completing the Survey |

750 |

80% |

600 |

0.42 |

252 |

$45 |

$11,340 |

|

Total for School Survey |

|

|

1,350 |

|

383 |

|

$16,965 |

|

Case studies |

Interview with a district official |

72 |

100% |

72 |

0.50 |

36 |

$45 |

$1,620 |

Identifying interview participants (principals’ support) |

36 |

100% |

36 |

1.00 |

36 |

$45 |

$1,620 |

|

Individual interviews with school staff |

288 |

100% |

288 |

1.00 |

288 |

$29 |

$8,352 |

|

Total for Case Studies |

|

|

396 |

|

360 |

|

$11,592 |

|

TOTAL |

|

|

1,746 |

|

743 |

|

$28,557 |

|

13. Estimate of Cost Burden to Respondents

There are no additional respondent costs associated with this data collection beyond the hour burden estimated in item A12.

14. Estimate of Annual Cost to the Federal Government

The estimated cost for this study, including development of a detailed study design, data collection instruments, justification package, data collection, data analysis, and report preparation, is $2,174,984.00 for the three years, or approximately $724,995 per year.

15. Program Changes or Adjustments

This request is for a new information collection, thus all burden is considered new.

16. Plans for Tabulation and Publication of Results

We have designed our data collections, data management, and analysis procedures to accommodate the short data collection period of 9/2/2010 to 8/1/2011. The research team will develop coding materials for entering and preparing data for analysis as it is received, and will enter all data into an electronic database. Our team will ensure accuracy of the data and will analyze the data as described in our analytic approach. The research team will submit preliminary data tabulations to the Contracting Officer’s Representative (COR) no later than October 3, 2011. General approach to analyses is described in Part B of this submission.

The Data Analysis Report will describe what we have learned about CLP schools that have successfully turned around, including the ways different external PPP trigger, foster, and sustain turnaround; the adoption at the school level of PPP; the various PPP; and the important features of PPP. The report will systematically address the RQs for Study II and document all aspects of the work. The report will provide objective, descriptive data on the prevalence of various PPP in CLP schools. We understand that as important as the basic description of the prevalence of PPP is, the main contribution of this report will be to examine why schools can implement similar sets of PPP yet achieve very different outcomes. This examination of the interaction among PPP in differing contexts is what will set this report apart from others.

The Data Analysis Report will be submitted to ED and three members of the TWG by October 3, 2011. Upon review (within 2 weeks), we will submit a revision by November 21, 2011. Upon review, again within 2 weeks by ED and the same TWG members, we will prepare a final draft to be submitted by January 9, 2012.

The Summary Report will describe and highlight specific, replicable PPP of CLP schools that have the potential to be tested experimentally. The Summary Report will synthesize findings of Studies I and II and include discussions of a theory of change, prior relevant research, PPP and their constituent components that need further refinement, mediating and moderating factors, challenges to evaluating the identified PPP, and limitations and lessons learned from the studies. We expect, on the basis of Study II, to identify certain PPP that hold promise for further rigorous study. The Summary Report will be submitted to ED and three members of the TWG by March 1, 2012. Upon review (within 2 weeks), we will submit a revision by April 16, 2012. Upon review, again within 2 weeks by ED and the same TWG members, we will prepare a final draft to be submitted by June 4, 2012.

No other reports or public data files are envisioned at this point.

17. Approval to Not Display OMB Expiration Date

All data collection instruments will include the OMB expiration date.

No exceptions are requested.

References

Aaronson, D., Barrow, L., & Sander, W. (2007). Teachers and student achievement in the Chicago Public High Schools. Journal of Labor Economics, 25(1), 95–135.

Aladjem, D. K., LeFloch, C., Zhang, Y., Kurki, A., Boyle, A., Taylor, J. E., Herrmann, S., Uekawa, K., Thomsen, K., & Fashola, O. (2006). Models matter—The final report of the national longitudinal evaluation of comprehensive school reform. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research.

Berman, P., & McLaughlin, M. W. (1978). Federal programs supporting educational change, Vol VIII: Implementing and sustain innovation. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Bodilly, S. J. (1998). Lessons from New American Schools’ scale‑up phase: Prospects for bringing designs to multiple schools. Washington, DC: RAND.

Boyd, D. J., Grossman, P. L., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. H. (2009). Teacher preparation and student achievement (CALDER Working Paper No. 20). Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research.

Boyd, D. J., Grossman, P. L., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. H. (2009a). Who leaves? Teacher attrition and student achievement (CALDER Working Paper No. 20). Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research.

Boyd, D. J., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., Rockoff, J. E., & Wyckoff, J. H. (2007). The narrowing gap in New York City teacher qualifications and its implications for student achievement in high poverty schools (CALDER Working Paper No. 10). Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research.

Boyd, D. J., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. H. (2005). Explaining the short careers of high‑achieving teachers in schools with low‑performing students. American Economic Review, 95(2), 166–171.

Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Bryk, A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Supescu, S., & Easton, J. Q. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Choi, K. (2005). Monitoring school improvement over years using a 3‑level hierarchical model under a multiple‑cohorts design: comparing scale score to NCE results. Asian Journal of Education, 6(1), 59–81.

Choi, K. (2009). Multisite Multiple‑Cohort Growth Model with Gap Parameter (MMCGM): Latent variable regression 4‑level hierarchical models. IES unsolicited grant annual report.

Choi, K., & Seltzer, M. (in press). Modeling heterogeneity in relationships between initial status and rates of change: Treating latent variable regression coefficients as random coefficients in a three‑level hierarchical model. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics.

Choi, K., Seltzer, M., Herman, J., & Yamashiro, K. (2007). Children left behind in AYP and non‑AYP schools: Using student progress and the distribution of student gains to validate AYP. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 26(3), 21–32.

Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2007). How and why do teacher credentials matter for student achievement? CALDER Working Paper No. 2. Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research.

Clotfelter, C., Ladd, H., & Vigdor, J. (2005). Who teaches whom? Race and the distribution of novice teachers. Economics of Education Review, 24(4), 377–392.

Cohen, D. K., & Lowenberg-Ball, D. (1999). Instruction, capacity, and improvement (CPRE Research Report Series RR 43). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education, Consortium for Policy Research in Education.

Crandall, D. P., Loucks-Horsley, S., Baucher, J. E., Schmidt, W. B., Eiseman, J. W., & Cox, P. L. (1982). Peoples, policies, and practices: Examining the chain of school improvement (Vols. 1–10). Andover, MA: The NETWORK.

Datnow, A., & Stringfield, S. (2000). Working together for reliable school reform. Journal of Education for Students Placed At Risk, 5, 183–204.

Duke, D. (2004). The turn‑around principal: High‑stakes leadership. Principal, 84(1), 12–23

Elmore, R. F. (2004). School reform from the inside out: Policy, practice, and performance. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Fullan, M. (2001). The new meaning of educational change. 3rd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

Goldhaber, D., Gross, B., & Player, D. (2007). Are public schools really losing their best? Assessing the career transitions of teachers and their implications for the quality of the teacher workforce (CALDER Working Paper No. 12). Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research.

Goldschmidt, P., Choi, K., Martinez, F., & Novak, J. (under review). Using growth models to monitor school performance: comparing the effect of the metric and the assessment. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice.

Hanushek, E. (1986). The economics of schooling: Production and efficiency in public schools. Journal of Economic Literature, 24(3), 1141–1177.

Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2008). Do disadvantaged urban schools lose their best teachers? (CALDER Policy Brief No. 7). Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research.

Hanushek, E., J. Kain, & Rivkin, S. (2004). Why public schools lose teachers. Journal of Human Resources, 39(2), 326–354.

Herman, R., Dawson, P., Dee, T., Greene, J., Maynard, R., Redding, S., & Darwin, M. (2008). Turning around chronically low‑performing schools: A practice guide (NCEE #2008‑4020). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/practiceguides.

Kirby, S. N., Berends, M., & Naftel, S. (2001). Implementation in a longitudinal sample of New American Schools: Four years into scale‑up. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Kurki, A., Boyle, A., & Aladjem, D. K. (2006). Implementation: Measuring and Explaining the Fidelity of CSR Implementation. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 11(3&4), 255–277.

Lankford, H., S. Loeb, S, & Wyckoff, J. (2002). Teacher sorting and the plight of urban schools: A descriptive analysis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24(1), 37–62.

Leithwood, K., Louis, K. S., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How leadership influences student learning. Minneapolis and Toronto: Center for Applied Research on Educational Improvement and Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Loeb, S.,& Miller, L. (in press). The effect of principals on teacher retention (working title; CALDER Working Paper). Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research.

Marsh J. A., Pane, J. F., & Hamilton, L. S. (2006). Making sense of data‑driven decision making in education: Evidence from recent RAND research. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

McLaughlin, M. W., & Talbert, J. E. (2006). Building school‑based teacher learning communities: Professional strategies to improve student achievement. New York: Teachers College Press.

Newmann, F. M., & Associates. (1996). Authentic achievement: Restructuring schools for intellectual quality. San Francisco: Jossey‑Bass.

Newmann, F. M., King, B. & Youngs, P. (2001). Professional development that addresses school capacity: Lessons from urban elementary schools. American Journal of Education, 108 (4), 259-299.

Newmann, F. M., Smith, B., Allensworth, E., & Bryk, A. (2001). Instructional program coherence: What it is and why it should guide school improvement policy. Education Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 23(4), 297–321.

Ponisciak, S. M., & Bryk, A. (2005). Value‑added analysis of the Chicago Public Schools: An application of hierarchical models. In R. Lissitz (Ed.), Value‑added modeling in education: Theory and applications (pp. 40–79). Maple Grove, MN: JAM Press.

Raudenbush, S. W. (2004). Schooling, statistics, and poverty: Can we measure school improvement? Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Sass, T. R. (2008). The stability of value‑added measures of teacher quality and implications for teacher compensation policy (CALDER Policy Brief No. 4). Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research.

Smith, B., Roderick, M., & Degener, S. (2005). Extended learning time and student accountability: Assessing outcomes and options for elementary and middle grades. Educational Administration Quarterly, 41(2), 195–236.

Stringfield, S., Millsap, M., Yoder, N., Schaffer, E., Nesselrodt, P., & Gamse, B. (1997). Special strategies studies final report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Turnbull, B. J. (2006). Comprehensive school reform as a district strategy. In D. K. Aladjem & K. M. Borman (Eds.), Examining comprehensive school reform. Washington DC: The Urban Institute Press.

U.S. Department of Education. (2010). Achieving Dramatic School Improvement: An Exploratory Study. Author: Washington, DC.

Van de Ven, A. H., & Poole, M. S. (1995). Explaining development and change in organizations. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 510-540.

Xu, Z., Hannaway, J., & Taylor, C. (2009). Making a difference? The effects of Teach for America in high school (CALDER Working Paper No. 17). Washington, DC: National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research.

1 The study focuses on elementary and middle schools.

2 Data collected during case studies will be used as a final verification of data from other sources. Our experience is that we can learn things in the field that may contradict official administrative data and survey data.

1000 THOMAS JEFFERSON STREET, NWWASHINGTON, DC 20007‑3835TEL 202 403 5000FAX 202 403 5020WEBSITE WWW.AIR.ORG

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| File Title | Introduction |

| Author | Information Technology Group |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-02-02 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy