ATTACHMENT M_CHIPRA ELE Evaluation Final Design and Work Plan Part 1

11. ATTACHMENT M_CHIPRA ELE Evaluation Final Design and Work Plan Part 1.docx

CHIPRA-Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 -ELE

ATTACHMENT M_CHIPRA ELE Evaluation Final Design and Work Plan Part 1

OMB: 0990-0400

Attachment m

CHIPRA ELE EVALUATION DESIGN REPORT

CHIPRA Express Lane Eligibility Evaluation

Final Design Report and Work Plan

Volume I: Evaluation Design

January 13, 2012

Mathematica Policy Research Marian Wrobel Sheila Hoag Margaret Colby Sloane Frost Cara Orfield Sean Orzol Adam Swinburn Kristina Rall

|

Urban Institute Fiona Adams Sarah Benatar Frederic Blavin Brigette Courtot Stan Dorn Ian Hill Genevieve Kenney Health Management Associates Jennifer Edwards Rebecca Kellenberg Eileen Ellis Sharon Silow-Carroll Esther Reagan Diana Rodin

|

This page has been left blank for double-sided copying.

This page has been left blank for double-sided copying.

CONTENTS

I. introduction 1

A. ELE as a Policy Tool for Expanding Coverage 1

1. The Potential of ELE to Raise Enrollment 2

2. Other Potential Benefits of ELE 2

3. Current State Implementation of ELE 4

B. Alternate Approaches to Expanding Coverage and Simplifying Enrollment and Retention 7

C. The Congressionally Mandated Evaluation of ELE 8

II. overview of the evaluation design 11

III. The Technical Advisory Group and its role in the evaluation 19

A. Purpose of the TAG 19

B. TAG Member Selection and Recruitment 19

C. Methods 20

D. Initial TAG Meeting 20

E. Next Steps 21

IV. Study 1: Ongoing Assessment of the State Policy Context 23

A. Baseline Information Review 23

B. State Tracking and Monitoring 24

1. Selecting the 30 States 24

2. Selecting Key Informants 25

3. Key Informant Interviews 25

4. Quarterly Reports 26

C. 51-State Survey 26

V. Study 2: Analysis of ELE Impacts on Enrollment (Using SEDS) 29

A. Data Sources 29

B. Analysis 32

C. Challenges 34

VI. Study 3: Case Studies of States Adopting ELE and Other Approaches to Simplifying Enrollment and/or Retention 37

A. ELE Program Case Studies 37

1. Review of State Documents, Evaluation Reports, and Other Background Material 38

2. Site Visits 38

3. Focus Groups 41

B. Case Studies in Non-ELE States 38

1. Selecting Non-ELE States 38

2. Focus Groups in Non-ELE States 39

C. Analysis and Reporting 38

D. Challenges and Limitations 38

vii. DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF COSTS, ENROLLMENT, AND UTILIZATION IN CASE STUDY STATES 40

A. ELE States 41

1. Acquisition of Data 41

B. Cost Analysis 43

1. Motivation 43

2. Administrative Cost Data and Analysis—First Year 44

3. Administrative Cost Data and Analysis—Second Year 61

4. Challenges 61

C. Enrollment Analysis 62

1. Motivation 62

2. Enrollment Data and Analysis – First Year 62

3. Enrollment Data and Analysis—Second Year 64

4. Challenges 65

D. Utilization Analysis 65

1. Motivation 65

2. Utilization Data and Analysis 66

3. Challenges 67

E. Reporting 67

Chapter VII (Continued)

F. Non-ELE Program Cost and Enrollment Study 68

1. Acquisition of Data 68

2. Motivation 68

3. Cost and Enrollment Data and Analysis 68

4. Challenges 68

5. Coordination 69

6. Reporting 69

VIII. Evaluation Reports and related briefings 71

A. Recommendations on ELE Improvements 71

B. Reports to Congress 72

C. Study Briefings 73

IX. Developing and Obtaining Approval for Data Collection Instruments 75

A. OMB Clearance 75

B. IRB Approval 76

REFERENCES 77

APPENDIX A: Example of memorandum of understanding for study of costs enrollment, and utilization 81

APPENDIX B: example of table shells for study of costs, enrollment, and utlization 86

This page has been left blank for double-sided copying.

TABLES

I.1 States with Approved State Plan Amendments for CHIPRA Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) Prepared November 14, 2011 5

I.2 Mapping of RFP Tasks to the Evaluation’s Four Studies and Chapters of the Design Report 10

II.1 Evaluation Goals, Research Questions, and the Main Studies and Data Sources for Addressing Them 14

II.2 Key Characteristics of Evaluation Studies and Data Sources 15

III.1 TAG Members 19

VI.1 ELE Site Visit Interview Protocol Potential Topics and Questions 43

VI.2 Potential ELE State Focus Group Moderators’ Guide 37

VI.3 Proposed Non-ELE States Focus Group Moderator’s Guide 41

VII.1. Key Research Questions Addressed Through Program Cost, Enrollment, and Utilization Study 40

VII.2 Summary of Analyses Completed Under Program Cost, Enrollment, and Utilization Study 41

VII.3 Draft Discussion Guide for ELE States Cost Study 45

VIII.1 Content and Sources of Data for Interim and Final Reporting to ASPE 72

IX.1 Schedules for OMB Submission 75

This page has been left blank for double-sided copying.

FIGURES

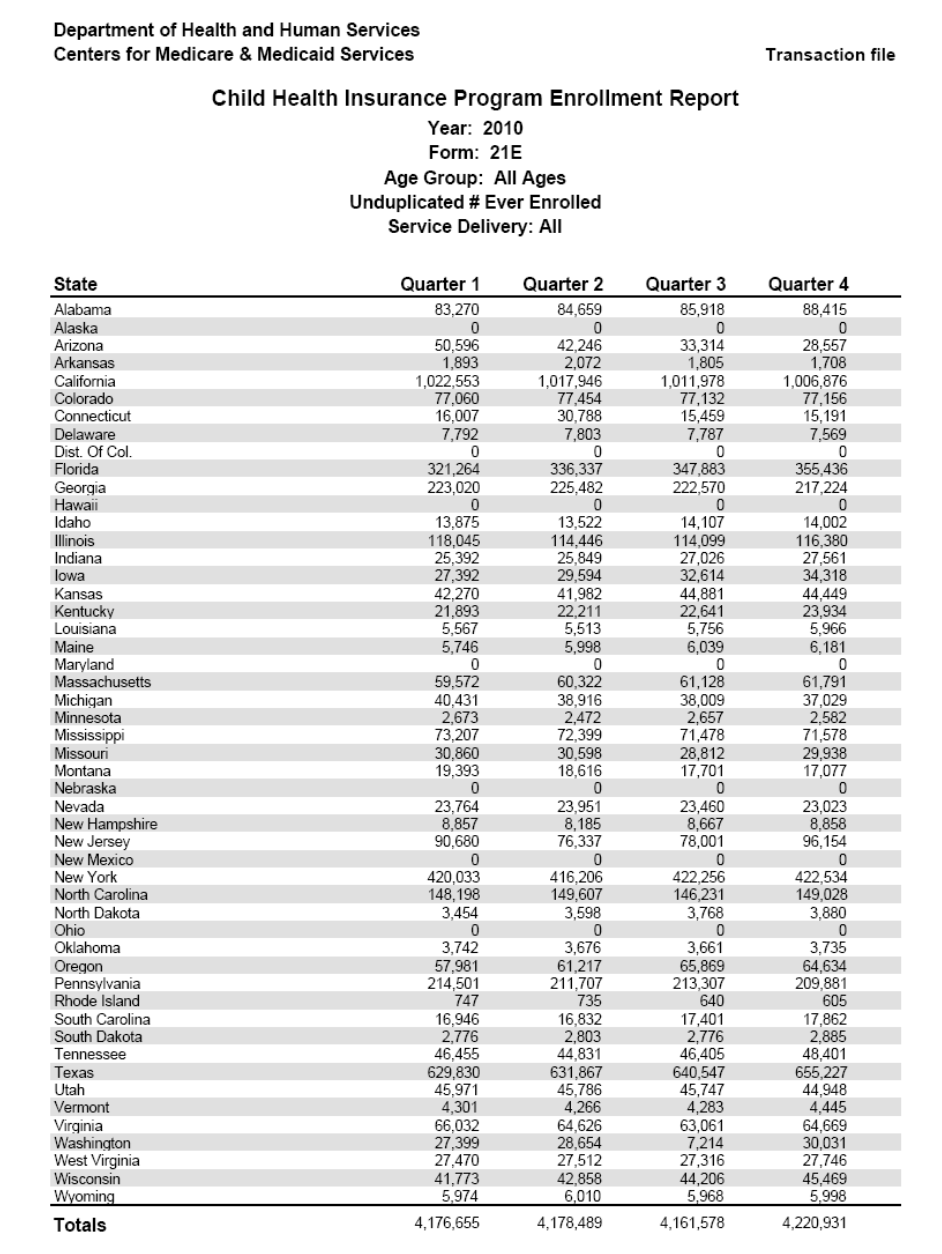

V.1 Snapshot of the 2010 Form 21E Quarterly (SEDS) Enrollment Report 31

This page has been left blank for double-sided copying.

I. introduction

As part of the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHIPRA), Congress gave states the option to implement a new policy known as Express Lane Eligibility (ELE). With ELE, a state’s Medicaid and/or Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) can rely on another agency’s eligibility findings to qualify children for health coverage, despite its different methods of assessing income or otherwise determining eligibility. ELE thus gives states another way to try to enroll and retain children who are eligible for Medicaid and CHIP but remain uninsured, including children who have traditionally been most difficult to reach.

CHIPRA authorized an extensive, rigorous evaluation of ELE, creating an exceptional opportunity to document ELE implementation across states and to assess the changes to coverage or administrative costs that might have resulted. The evaluation also provides an opportunity to understand other methods of simplified or streamlined enrollment that states have pursued and to assess the benefits and potential costs of these methods compared with those of ELE. The evaluation, to be conducted on behalf of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), will yield two major Reports to Congress: an interim report, due by September 30, 2012, and a final report, due by September 30, 2013.

This report presents the design for the congressionally mandated evaluation of ELE. The evaluation will be led by Mathematica Policy Research, with the assistance of the Urban Institute and Health Management Associates (HMA). The design presented here has benefited from multiple discussions with ASPE as well as a day-long meeting with our technical advisory group (TAG), discussed in Chapter III.

A. ELE as a Policy Tool for Expanding Coverage

ELE is best described as an open-ended authorization of a broad range of state efforts to incorporate findings from other public agencies into the eligibility determinations of Medicaid and CHIP programs. As the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) explained, “There is no one way to implement the Express Lane option” (Centers for Medicaid and State Operations 2010).

This breadth in the definition of ELE distinguishes it from other strategies to improve enrollment and retention (such as continuous eligibility, elimination of asset requirements, elimination of in-person interview requirements, and joint Medicaid/CHIP applications), which have similar basic structural features in most implementing states. In contrast, with ELE, a state can choose from among 13 named agencies with which to partner, or even select an unlisted program that fits the statute’s broad definition of an “Express Lane Agency.”1 Other features can vary. For example, ELE can apply to enrollment, retention, or both; ELE can either include or exclude an automatic enrollment option; ELE can apply to CHIP, Medicaid, or both; states can use traditional approaches to CHIP screen-and-enroll requirements or choose from among two alternative approaches specified in CHIPRA; and states may choose the element or elements of Medicaid or CHIP eligibility (except citizenship) to borrow from the findings of other agencies. Thus, many facets of the evaluation treat ELE as consisting of multiple differing initiatives in different states, not as one single initiative carried out in multiple states.

1. The Potential of ELE to Raise Enrollment

ELE has the potential to raise the enrollment of eligible children in public health insurance, both by raising families’ awareness of their eligibility and by reducing barriers to enrollment. With roughly two-thirds of the nation’s uninsured children eligible for Medicaid or CHIP but not enrolled (Kenney et al. 2010), significant progress in expanding coverage might depend on the kind of flexible strategy that ELE permits states to follow. As a tool for increasing eligible children’s coverage through Medicaid and CHIP, the promise of ELE has been well identified. For example, using ELE to qualify children for health coverage based on their participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Kenney et al. (2010) estimate that ELE could reach 15.4 percent of eligible, uninsured children. Using ELE to qualify children for health coverage based on state income tax records could reach even more children. An estimated 89 percent of uninsured children who qualify for Medicaid or CHIP live in families who file federal income tax returns (Dorn et al. 2009). Presumably, a large proportion of these families file state returns as well, particularly in states that supplement the federal Earned Income Tax Credit. ELE might also hold the potential to reach many adults beginning in 2014.

Insights from behavioral economics further underscore the potential of ELE as a way to expand coverage. Behavioral economists have reminded us of inertia’s remarkable power to shape enrollment into public or private benefits. For example, with the by-now-classic example of 401(k) retirement savings accounts, if new employees must complete applications to enroll, roughly a third participate; but if they are automatically enrolled unless they complete a form opting out, 90 percent join (Laibson 2005). ELE was intended to greatly minimize the need to complete applications for health coverage, because eligibility determination could be based on the findings of other agencies to which the families of uninsured children had already demonstrated low income or other facts relevant to eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP.

2. Other Potential Benefits of ELE

ELE also has other potential benefits beyond the potential increases in enrollment. Families that would otherwise have enrolled in public health insurance via traditional pathways also benefit when enrollment is made more automatic and less difficult. When systems function smoothly, states might enjoy lower per-application costs due to a streamlined process.

In addition, investments in the name of ELE can offer diverse benefits beyond increased enrollment and reduced burden. We discuss these briefly next.

ELE embodies an innovative approach to the broad problem of siloed public benefits. Low-income families seeking several forms of assistance must typically provide the same information to more than one program, each of which pays its staff to process that information. This creates needless red tape for families, administrative costs for government agencies, and more demanding application procedures that ultimately reduce participation levels. One reason for such redundancy involves technical differences between program eligibility rules. For example, SNAP generally limits benefits to households with net income at or below 100 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). One might think that SNAP-recipient children are thus necessarily income-eligible for Medicaid and that, when families seek Medicaid on their behalf, they could be relieved of the need to document income. However, SNAP determines net income by applying excess shelter cost deductions that Medicaid does not use. SNAP and Medicaid also use different definitions of the household members whose needs and earnings count in determining income. Therefore, SNAP eligibility determinations typically cannot qualify children for Medicaid without families providing additional information or Medicaid staff meticulously “cross-walking” information from SNAP records into the categories established by Medicaid eligibility rules.

A traditional approach to breaking down these silos involves modifying different programs’ rules and procedures so they align. Although this approach has considerable merit, it is difficult to change the rules of multiple programs. ELE takes a different approach that can, under some circumstances, be easier to implement. In this approach, each program continues to apply its own eligibility methodologies, but one agency uses the other agency’s findings to qualify people for subsidies, despite their methodological differences.

ELE provides a new way to address the challenges created by delinking Medicaid and cash assistance. Before the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) passed in 1996, the typical route to Medicaid ran through applications for cash assistance, which represented a higher priority than health coverage for many low-income families. With ELE, a state can once again hitch health coverage to other benefits, such as SNAP, that many families perceive as a higher priority.

It is true that public benefit programs have long offered application forms that permit families to simultaneously seek SNAP, Medicaid, cash assistance, and sometimes other benefits (such as energy assistance). However, such forms request the information needed by all these programs, a burden that defeats many applicants. To help families avoid long forms, some states have encouraged families to file SNAP-only applications or Medicaid/CHIP-only applications. ELE offers states a way to reduce the burden of multiprogram enrollment: a family filing a SNAP-only application can receive Medicaid or CHIP as well.

ELE substitutes data matches for the manual processing of forms in determining eligibility. This helps states do more with less. In much of the country, the worst state budget crises in decades have led to staff cutbacks and hiring freezes, shrinking the staff that take applications and determine eligibility, even as the ongoing economic downturn continues an elevated demand for services. Strategies such as ELE, which can lower administrative costs of enrollment and renewal, are particularly appealing to state officials with limited administrative resources.

ELE can help states comply with the Affordable Care Act. The Affordable Care Act requires states to transition to data-based eligibility methods that will qualify people for Medicaid, CHIP, and subsidies in the Affordable Insurance Exchanges, a step that ELE states have made progress to implement. Because of the central role of modified adjusted gross income and tax return information under the Affordable Care Act, this progress is particularly meaningful for states that use ELE to grant eligibility based on data matches with tax agencies. In addition, SNAP linkages might be useful for states seeking to reduce their administrative burdens by prequalifying low-income adults who will be newly eligible for Medicaid in 2014. More fundamentally, the Affordable Care Act requires that, whenever possible, eligibility for Medicaid, CHIP, and subsidies in the Affordable Insurance Exchanges must be established, verified, and renewed based on matches with reliable data sources. With ELE, states can begin making the challenging shift from traditional, manual methods to data-based routines for processing applications and renewals.

3. Current State Implementation of ELE

Despite the substantial promise of ELE as a way to achieve progress across a range of state priorities, only a handful of states have implemented it so far. As Table I.1 shows, only eight states—Alabama, Georgia, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, New Jersey, Oregon, and South Carolina—currently have approved plan amendments. Moreover, several of these amendments (Georgia, Iowa, Maryland, Oregon, and South Carolina) were approved only in the past 18 months. Even among this small group of states, however, the variation in the ELE model is striking and reflects the flexibility that the CHIPRA authorization afforded. For example, their matching agencies range from those administering a collection of different benefits—such as school lunch (New Jersey, just approved), SNAP (Alabama, Iowa, Louisiana, and South Carolina), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) (Alabama and South Carolina), and WIC (Georgia)—to those responsible for aspects of state revenue, including the Division of Taxation (New Jersey) and the Office of the Comptroller (Maryland).

Results from the models are beginning to emerge and often reflect self-reported descriptive data or qualitative information. These results suggest that the benefits of ELE vary, depending on the models implemented, though a more formal evaluation is clearly needed to draw credible conclusions within and across these states. Current data indicate that variation exists in enrollment using the ELE mechanism across the states (Table I.1). The ELE evaluation will build upon this base to fully characterize existing programs, to understand their impacts and implications, and to determine which programs have best practices that other states should model.

With only eight approved and implemented ELE programs, several factors have likely contributed to the modest uptake of ELE. The first is the economy: even in states with longstanding commitments to reaching all eligible children, serious fiscal woes have created strong resistance to the cost effects of increasing the number of children receiving Medicaid and CHIP. The second is the level of effort that might be required. This includes addressing challenging operational issues (such as linkages with sibling agencies that run different programs) and the intensive retraining and monitoring of social services staff unaccustomed to the approach. Finally, like any new, simplified enrollment method, ELE requires leadership and creative energy to pursue. Management staff have been reduced in many state agencies, and ELE implementation must compete for attention with top priorities, such as managing severe cutbacks and preparing for Affordable Care Act implementation.

Including ELE as one of the eight best practices for enrollment and retention, of which a state must implement at least five to qualify for performance bonuses under CHIPRA, likely has been a countervailing force and encouraged take-up of ELE among states.

Table I.1. States with Approved State Plan Amendments for CHIPRA Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) Prepared November 14, 2011

State and Program Type(s) using ELEa |

Matching Agencies, Eligibility Level for Ages 0-18, Effective Dates |

ELE Activities |

Results |

Alabamab

Medicaid

|

SNAP & TANF, 300% FPL, 4/1/2010 (SNAP) 10/1/2009 (TANF) |

Approved state plan amendment to conduct Medicaid eligibility and renewal using net income, family size, and income disregards from TANF and SNAP. Also deployed technology that allows online enrollment for multiple public programs and, on the back end, supports cross-agency data retrieval, verification, and processing. |

Three months after enactment, Alabama had renewed eligibility for more than 3,600 children. By the end of August 2010, 28,927 children had been processed. Alabama attributes its early success to good collaboration among Medicaid, TANF, and SNAP agencies. |

Georgia

Medicaid & CHIP |

WIC, 235% FPL, 1/1/2011 (Medicaid) 4/1/2011 (CHIP) |

Approved state plan amendment to use income information from WIC to establish CHIP eligibility. WIC agents check a system indicator field that enables them to share the information with the Department of Community Health (DCH). A data file from WIC is uploaded to PeachCare’s system nightly. DCH uses the income, age, residency, and identity portions of the WIC file, but must request additional information on household members, Social Security number (SSN), and citizenship status. |

Georgia has approved about 1,000 individuals for coverage between the two programs since April.

Although approved for enrollment and renewal, although in practice only the enrollment process is in place (ELE is not yet being used for redeterminations). |

Iowa

Medicaid & CHIP |

SNAP & Medicaid, 300% FPL, 6/1/2010 |

Approved state plan amendment to conduct automatic enrollment without a Medicaid application, using SNAP findings/data for all eligibility elements except citizen/alien status. |

As of June 30, 2011, the ELE form was sent to 15,549 families, and 1,396 children had been approved through the ELE option; 1,623 applications were in process. ELE must be requested by returning an opt-in form. ELE was not requested by 12,365 children. |

Louisiana

Medicaid |

SNAP & NSLP, 250% FPL, 10/10/2009 |

Approved state plan amendment to conduct Medicaid eligibility and renewal using SNAP and school lunch agency findings as to SSN (from SNAP), income, age, residency, and identity. Allows for the use of automatic enrollment. This process was implemented after years of conducting ex parte renewal through the Food Stamp and TANF programs. |

10,545 children were enrolled in the first month of ELE-enabled automatic eligibility. As of April 30, 2010, 3,391 children had already obtained medical services. Another 6,000 children needed further review due to minor errors in dates or names that prevented data-matching. After the initial wave of enrollment, child enrollment grew at 2.8% (the national average is 5.3%). |

Maryland Medicaid |

Office of the Comptroller 200% FPL, 4/1/2010 |

Approved state plan amendment to use information from state income tax records to make an initial Medicaid determination, using state residency information. Notices were sent to taxpayers with a dependent child who met income eligibility standards in tax year 2007. 2008 tax forms asked taxpayers to report health insurance coverage status for each dependent child. Medicaid/CHIP applications and enrollment instructions were then sent to all potentially eligible families. Maryland provides accelerated enrollment to Medicaid and CHIP applicants who already have an active case with Maryland’s Department of Social Services. Those children are eligible for up to three months pending a final determination. |

In 2007, approximately 450,000 families received the eligibility letter—180,000 families under 116% of the FPL and the rest between 116 and 300% of the FPL. One year after the comptroller sent the first wave of notices to taxpayers, more than 30,000 of Maryland’s uninsured children were enrolled in public coverage. The extent to which the notices were responsible for Maryland’s enrollment is unknown.

|

New Jersey Medicaid & CHIP |

Div. Taxation National School Lunch Program (NSLP), 350% FPL, 5/1/2009 |

Approved state plan amendment to use state tax records to establish income, budget unit, health insurance, citizenship (through SSN), and identity, for initial enrollment and renewal into Medicaid. Families have an opportunity to indicate they have uninsured dependents on their tax forms. These families are sent a form on which they authorize the use of the tax agency’s income finding to make an income-eligibility determination for Medicaid and CHIP and provide minimal additional information for a full eligibility picture. Also, New Jersey recently approved the use of data from the school lunch agency. |

The Department of Human Services mailed New Jersey FamilyCare Express Lane applications to each household identified as uninsured and below the eligibility threshold. It had a response rate of 5.7 percent, receiving only 16,504 completed applications. Of those, only 3,834 children were enrolled in FamilyCare. Initial feedback is that not many families have enrolled due to the two-step process. |

Oregon

Medicaid & CHIP |

SNAP & NSLP, 184% FPL, 8/1/2010 |

Approved state plan amendment to use SNAP and school lunch agency findings to make an initial Medicaid determination as to income, group size/household composition, SSN, and residency. Allows for the use of automatic enrollment. |

The state reports investing heavily in outreach and streamlining applications across programs. Internal culture has changed to work across programs for a common purpose. No data available. |

South Carolina

Medicaid

|

SNAP & TANF, 200% FPL, 4/1/2011 |

Approved state plan amendment allows South Carolina Medicaid to process redeterminations for children in families with incomes less than 200% of FPL in partnership with SNAP and TANF. |

The state expects to enroll 70,000 children and save $1 million in administrative costs as a result of this electronic collaboration. |

Sources: CHIP and Medicaid State Plan Amendments. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services web site. Accessed August 2, 2011.

The Children’s Partnership. “Express Lane Activities: States on the Move.” January 2011. Accessed August 2, 2011. http://www.childrenspartnership.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=State_Activity_Report&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=13347

The Children’s Partnership ELE Program Examples web page. Accessed August 2, 2011. http://www.childrenspartnership.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=State_Activity_Report&Template=/TaggedPage/TaggedPageDisplay.cfm&TPLID=153&ContentID=12200

The Children’s Partnership. “Express Lane Eligibility: Louisiana Moves Forward.” Updated April 2010. Accessed August 2, 2011. http://www.childrenspartnership.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Express_Lane_Toolkit&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=14527

Families USA. “Express Lane Eligibility: Early State Experiences and Lessons for Health Reform.” January 2011. Accessed August 2, 2011. http://www.familiesusa.org/assets/pdfs/chipra/Express-Lane-Eligibility-State-Experiences.pdf

Interviews with state officials conducted by HMA. July 2011.

Kaiser Family Foundation’s State Health Facts web page. Accessed August 2, 2011. http://www.statehealthfacts.org/comparemaptable.jsp?ind=898&cat=4&sub=195&rgnhl=2

Robert Wood Johnson and State Health Access Data Center. “Reaching Uninsured Children: Iowa’s Income Tax Return and CHIP Project.” August 2010. Accessed August 2, 2011. http://www.childrenspartnership.org/AM/Template.cfm? Section=State_Activity_Report&TEMPLATE=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=14979

Robert Wood Johnson[Foundation?] and State Health Access Data Center. “Using Information from Income Tax Forms to Target Medicaid and CHIP Outreach: Preliminary Results of the Maryland Kids First Act.” September 2009. Accessed August 2, 2011. http://www.childrenspartnership.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=State_Activity_Report&TEMPLATE=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=13839

Adcox, Seanna. “Good News: S.C. Medicaid May Add 70,000 Kids to Program.” South Carolina Health Care Voices, October 25, 2011. Available at http://schealthcarevoices.org/2011/10/25/good-news-s-c-medicaid-may-add-70000-kids-to-program/. Accessed 2011.

a Program Type shows the program(s) that allow(s) ELE matching, according to the RFP. Program Type does not reflect the programs states reported utilizing in 2010 CHIP Annual Reporting Template System (CARTS) or the CMS CHIP map

(https://www.cms.gov/LowCostHealthInsFamChild/downloads/CHIPMapofStatePlanActivity.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2011).

b Alabama submitted two ELE state plan amendments. The first covered redetermination and was approved on November 2, 2009; the second covered both initial determination and redetermination and was approved on June 7, 2010.

B. Alternate Approaches to Expanding Coverage and Simplifying Enrollment and Retention

At the same time that some states are introducing ELE, many states are developing and implementing other approaches to raising families’ awareness of the availability of public health insurance and streamlining the enrollment and renewal process. Similar to ELE, these approaches frequently involve partnering with other organizations that serve the same population or making use of electronic data collected for other purposes. These alternate approaches include the following:

Online applications, including universal online application for multiple programs (for example, Wisconsin and Massachusetts both use a single portal model to apply for many public benefit programs)

Community-based application assistance (for example, many community groups received CHIPRA outreach grants in 2010 and 2011 to focus on community application assistance)

Automatic conversion from Medicaid to CHIP and vice versa if a child’s age or income change is reported (as in Massachusetts and possibly other states)

Use of data obtained from other state sources (ex parte data); for example, 13 states currently use ex parte data for renewal in CHIP (Hoag et al., 2011)

Co-location of Medicaid/CHIP eligibility determination with other benefit offices (such as in Utah, Michigan, and Wisconsin, among others)

Presumptive eligibility, permitting providers, schools, or other community-based organizations (CBOs) to screen and enroll those who appear eligibility (offered in CHIP by 16 states as of federal fiscal year 2010) (Hoag et al., 2011)

Data matching, which might be viable for adult enrollment support in 2014 (similar to ELE states that use income tax data)

Outreach via other programs, such as schools (some of the CHIPRA outreach grants are to schools, and 29 states reported schools as key outreach partners in the most recent CHIP annual reports) (Hoag et al., 2011)

Like ELE, these alternate approaches have the potential to raise enrollment and/or to alter the enrollment pathway for families who would otherwise have enrolled via a traditional pathway. Moreover, most of the approaches have some long-term potential to reduce the burden on states, families, or both via efficient use of existing data or by capitalizing on a situation or relationship that leads a family to be particularly receptive to enrolling in insurance. Like ELE, these approaches can create partnerships among agencies, move state data systems forward, and help states lay a strong foundation for the Affordable Care Act.

In some cases, the line between ELE and non-ELE approaches is not clear. In a few states, including California, Hawaii, and Illinois, the states referred to the use of ELE in their 2010 CHIP annual reports, implying that they defined their approaches as ELE, but did not have CMS-approved state plan amendments for ELE.

C. The Congressionally Mandated Evaluation of ELE

As the first major federal project to study ELE, the congressionally mandated evaluation of ELE offers an outstanding opportunity to (1) document the current state of ELE policy development and implementation; (2) assess its progress and potential for expanding coverage, reducing administrative costs, and creating a more streamlined enrollment process for families; (3) examine alternative approaches to streamlining the enrollment process and relate the associated benefits and costs to those of ELE; and (4) identify and share recommendations, best practices, promising approaches, and areas for improvement.

Mathematica, the Urban Institute, and HMA have designed the evaluation to consist of four independent but related studies:

Study 1 – Ongoing Assessment of the State Policy Context, via document review, quarterly interviews with state officials, and an all-state survey

Study 2 – Analysis of ELE Impacts on Enrollment using SEDS data

Study 3 – Case Studies of States Adopting ELE and Other Approaches to Streamlining Enrollment, including key informant interviews and focus groups with families

Study 4 – Descriptive Study of Costs, Enrollment, and Utilization in Case Study States

Each of these studies will feature its own design and draw on its own data sources, many of which will be available only through the substantial assistance of state agencies and state-level program stakeholders. However, the design of these studies will be coordinated to ensure that they benefit from one another and can be brought together in the two reports to Congress and other integrated reporting of findings.

Chapter II offers an overview of the evaluation design; Chapters III describes the TAG, whose comments will inform the design and the analysis of findings. Chapters VI to VII present the four studies: Chapter IV, the assessment of the state policy context; Chapter V, the analysis of enrollment data from SEDS; Chapter VI, the ELE and non-ELE state case studies; and Chapter VII, the study of costs, enrollment, and utilization. Chapter VIII describes how we will report on study findings, and Chapter XI explains how we will attain the necessary clearance from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the necessary approval of an institutional review board (IRB) approval.

The organization of this report differs from the task structure proposed in ASPE’s request for proposals (RFP) in order to reflect the intellectual and operational structure of the evaluation. For ASPE’s convenience, Table I.2 maps the evaluation tasks, as specified in the RFP, to the four studies that make up the evaluation and to the chapters of the design report. Table I.2 also indicates major changes to the evaluation design relative to the RFP. The remainder of the report will describe the current design without ongoing references to the RFP task structure or other aspects of the RFP.

A second volume presents our work plan, including the organizational chart of our proposed team and a detailed scheduled of the timing of tasks and project deliverables. We have designed our management plan to coordinate closely with ASPE to ensure that our team meets the CHIPRA requirements for the congressionally mandated evaluation of ELE. The work plan does follow the task structure defined in the RFP.

Table I.2. Mapping of RFP Tasks to the Evaluation’s Four Studies and Chapters of the Design Report

RFP Task Number |

RFP Task Description |

Evaluation Study |

Chapter of Design Reporta |

Major Changes to Design Relative to RFP |

1 |

Initial Meeting |

|

Volume II Only |

|

2 |

TAG |

|

Chapter 2 |

|

3 |

Work Plan |

|

Volume II is the work plan |

|

4 |

Analysis of the Statistical Enrollment Data System |

Study 2 |

Chapter 5 |

Add a second round of SEDS analysis in Year 1 |

5 |

Data Collection Instruments/OMB |

|

Chapter 9 |

|

6 |

ELE Program Cost and Enrollment Data Collection/Analysis |

Study 4 |

Chapter 7 |

Add

a second round of analysis of ELE states’ cost and

enrollment data in Year 2;. |

7 |

ELE Program Case Studies |

Study 3 |

Chapter 6 |

Reduce the number of ELE case studies from 10 to 8 |

8.1 |

Information Review |

Study 1 |

Chapter 4 |

|

8.2 |

State Tracking and Monitoring |

Study 1 |

Chapter 4 |

|

8.3 |

Case

Studies (in non-ELE states) |

Study 3 |

Chapter 6 |

Reduce

the number of ELE case studies from 10 to 6; |

8.3 |

Analysis of enrollment trends and collection of cost and enrollment data in Non-ELE States |

Study 4 |

Chapter 7 |

Design for non-ELE cost and enrollment analysis is in Chapter 7; add financial compensation for participating states (as in the ELE states) |

8.4 |

51 State Survey |

Study 1 |

Chapter 4 |

|

9 |

Recommendations |

|

Chapter 8 |

|

10 |

Reports to Congress |

|

Chapter 8 |

|

11 |

Study Briefings |

|

Chapter 8 |

|

12 |

Deliver Data and Programs |

|

Volume II only |

|

13 |

Progress Reports |

|

Volume II only |

|

a All tasks are discussed in the work plan, Volume II, of this report, which is organized according to ASPE’s task structure.

II. overview of the evaluation design

The goals and design of the evaluation aim to give Congress, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and state policymakers the necessary basis for making decisions on the use, design, and implementation of Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) and other non-ELE efforts aimed at streamlining the enrollment and/or retention process for public health insurance. In addition, the evaluation develops broader implications, notably those that pertain to the Medicaid expansions authorized by the Affordable Care Act.

The evaluation is framed around two broad goals and, within each of these goals, the major research questions specified in the request for proposals (RFP):

Goal 1: Describe ELE implementation, evaluate its benefits, assess ELE best practices, and make recommendations. Focusing on the subset of states that have implemented ELE as of June 30, 2011, the evaluation will examine how states are adopting ELE and the extent to which it has expanded coverage and affected administrative costs. The evaluation will also examine the potential benefits of, and barriers to, ELE in states that have not yet adopted it; the extent to which specific models might be most effective; and how ELE approaches can be improved, through changes at the federal level and through state policy and practice. The upper panel of Table II.1 shows questions addressed as part of this first goal.

Goal 2: Describe the adoption of alternative (or complementary) approaches to ELE, evaluate and compare their potential benefits, and assess best practices. Drawing on the experience of several states that have pursued alternatives to ELE for simplifying or streamlining enrollment or otherwise reaching and enrolling eligible but uninsured children, the evaluation will document alternatives, how they have been implemented, and their relative success in expanding coverage and reducing administrative costs. The evaluation will emphasize alternative approaches to streamlining and automation, such as online applications or data-driven approaches. The lower panel of Table II.1 shows questions addressed as part of this second goal.

As mentioned earlier, to meet these goals and address the research questions, the evaluation will consist of four independent but related studies:

Study 1: Ongoing assessment of the state policy context. Together, the three components of this study catalog the various approaches that states are using for outreach, enrollment, and retention, as well as state officials’ and others’ assessments of the impacts of these strategies in terms of enrollment, administrative costs, burden on families and other factors. They create a foundation of knowledge, a point of departure for other studies, and assist in the interpretation of other studies’ findings. The first component of the study is a comprehensive review of publicly available information, conducted early in the study. The second component is quarterly tracking in 30 states (almost all of the states that are not part of case studies), consisting of both ongoing document review and quarterly interviews with well-informed state officials. This tracking will enable the evaluation team to understand and assess ongoing policy developments in many states and to fill in any gaps in knowledge left by the information review. The final component is an internet survey of Medicaid/ Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) directors in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. This survey will produce data on program characteristics and perceived impacts that can be readily compared among all 51 states and can be used to quantify the prevalence of various program features among states as well as perceptions regarding program impacts. The 2012 Interim Report to Congress will include results from the information review and early results from the ongoing document review; the 2013 Final Report to Congress will contain all results.

Study 2: Analysis of ELE impacts on enrollment using data from the CMS Statistical Enrollment Data System (SEDS). This study draws upon quarterly state-level enrollment data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for all 50 states and the District of Columbia in order to estimate the effects of ELE on Medicaid and CHIP enrollment. It uses the differences-in-differences methodology in which trends in non-ELE states are used to simulate the counterfactual, defined as what would have occurred in ELE states absent ELE, and therefore to estimate program impacts. Other policy and economic variables are entered into the estimating equation as controls. An initial analysis will be conducted for the Interim Report to Congress, and an updated analysis will be part of the Final Report to Congress. If these results are consistent with other evaluation findings, then they will represent rigorous evidence of a critical intended outcome of ELE.

Study 3: Case studies of states adopting ELE and other approaches to streamlining enrollment and/or retention. The case studies in eight ELE states offer rich detail on the design and implementation of ELE programs, including the perspectives of multiple stakeholders. The case studies pursue all the steps in program implementation, the motivations and expectations of participants, the barriers, and the unexpected outcomes. The case studies include both interviews with state officials, ELE partners, and other stakeholders as well as focus groups with families that can speak to their side of the enrollment process. A parallel set of case studies in six non-ELE states, selected for their innovative approaches to streamlining enrollment, will offer comparable insights into other strategies deemed particularly important to the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) and other evaluation audiences. A case study report will be prepared for each of the 14 study states, and the case studies, collectively, will be summarized in the Final Report to Congress.

Study 4: Descriptive study of costs, enrollment, and utilization in case study states. In ELE states, the cost study invites one or more informed individuals to map out the ELE process, compare it to the traditional enrollment/renewal process, and identify the potential for long-term cost savings from offering families an alternate pathway. At the same time, this study inquires about the fixed and start-up costs involved in establishing an ELE program. In non-ELE case-study states, the cost study is structured similarly but focuses on other strategies of interest. Costs and administrative simplification are also intended outcomes of ELE and related initiatives.

The enrollment studies in ELE states collect aggregate or individual-level data on enrollment by pathway to analyze (1) the numbers of children reached by ELE, (2) their demographic characteristics, and 3) their long-term enrollment outcomes. In the second and third cases, data on ELE are compared with parallel data for traditional pathways. Aggregate data are obtained from the states, whereas individual-level data can be obtained either from the states or from other centralized sources, such as MaxEnroll or the Medicaid Statistical Information System (MSIS).2 The first analysis offers a critical consistency check on the findings from the Statistical Enrollment Data System (SEDS) analysis regarding net new enrollment and hints at the potential of ELE to displace families that would otherwise have enrolled via other pathways; the second analysis sheds light on whether ELE reaches specific demographic groups; the third assesses a critical outcome. Again, parallel studies in non-ELE case-study states assess comparable topics for strategies of interest.

Finally, the utilization studies, in ELE states only, analyze individual-level data, obtained from MSIS, on spending for families enrolled via ELE and traditional pathways. Observed differences reflect both baseline differences in medical need between those who are reached by ELE and traditional means as well as any impact the pathway might have on use. (For example, ELE enrollees might not understand that they have health insurance or how to use it.) Despite this conceptual ambiguity, evidence of spending is critical to assessing the effect of ELE on state budgets.

The 2012 Interim Report to Congress will include cost results for six ELE states, aggregate enrollment results for four ELE states, and enrollment results based on individual data for two ELE states; the Final Report to Congress will offer updated cost results for up to eight ELE states (currently six ELE states operational as of December 31, 2010 are funded for this portion of the study, although if the evaluation has leftover funds we will discuss with ASPE using those resources for cost and enrollment studies in the other two ELE states approved as of June 30, 2011) and six non-ELE states, aggregate enrollment results for two additional ELE states and six non-ELE states, and both enrollment results and utilization based on individual data for four ELE states.

Table II.2 summarizes key characteristics of the four studies side by side. As Table II.1 shows, although these studies are distinct, the questions they inform cut across multiple sources. For example, every single data source will contribute to our understanding of the enrollment effect of ELE and other streamlined pathways. The cross-cutting nature of these questions underscores the importance of coordinating and integrating the design and conduct of the four studies. Moreover, it underscores the critical need to synthesize findings across tasks in the reporting on the evaluation finding.

Table II.1. Evaluation Goals, Research Questions, and the Main Studies and Data Sources for Addressing Them

|

Study

1: |

Study

2: |

Study

3: |

Study

4: |

||||||||

Information Review |

Information Review |

Quarterly Interviews and Ongoing Document Review |

51-State Survey |

|

Interviews |

Focus Groups |

|

|||||

Describe ELE implementation, evaluate its benefits, and assess ELE best practices and lessons for improvement |

||||||||||||

Does ELE raise enrollment? |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||||

Has ELE adoption facilitated readiness for the upcoming Medicaid expansion? |

x |

x |

x |

|

x |

|

x |

|||||

What are the administrative costs or savings from ELE programs? How do these costs and savings related to those from other approaches or processes to streamline enrollment? |

x |

x |

x |

|

x |

|

x |

|||||

What are recommendations for legislative or administrative changes to improve ELE? |

x |

x |

x |

|

x |

x |

|

|||||

What ELE practices proved most effective in enrolling and retaining children in Medicaid and CHIP? |

x |

x |

x |

|

x |

x |

|

|||||

What barriers to enrollment and retention remain? |

x |

x |

x |

|

x |

x |

|

|||||

Describe alternative approaches to creating streamlined pathways, evaluate their benefits, and assess best practices |

||||||||||||

What other approaches or processes do states have in place for outreach and to streamline enrollment? |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

|||||

How do they compare to ELE? |

x |

x |

x |

|

x |

x |

x |

|||||

Enrollment? |

x |

x |

x |

|

x |

x |

x |

|||||

Facilitating readiness for expansions? |

x |

x |

x |

|

x |

|

|

|||||

Administrative costs and savings? |

x |

x |

x |

|

x |

|

x |

|||||

What are best practices for outreach and to streamline enrollment? |

x |

x |

x |

|

x |

x |

|

|||||

Table II.2. Key Characteristics of Evaluation Studies and Data Sources

Study and Data Source |

Mode |

States |

Topics Emphasized |

Study 1: Ongoing Assessment of the State Policy Context |

|||

Baseline Information Review |

Comprehensive review of publicly available information |

All states |

Baseline information on program design, implementation, and impact |

Ongoing Document Review |

Periodic document review focusing on state-specific sources and issues |

30 selected states |

Program design, implementation, and impact—emphasis on changes over time |

Quarterly Interviews |

Quarterly interviews with informed state officials |

30 selected states |

Program design, implementation, and impact—emphasis on changes over time as well as gaps in knowledge |

51-State Survey |

Internet survey with open- and closed-ended items answered by Medicaid/CHIP directors and their staff |

All states |

Comprehensive census of states’ approaches to enrollment and renewal as well as perspectives on other evaluation topics |

Study 2: Analysis of ELE Impacts on Enrollment Using SEDS Data |

|||

Data from CMS’ Statistical Enrollment Data Systems (SEDS) |

Administrative data on enrollment from CMS |

All states (repeated in Years 1 and 2) |

Net enrollment impact of ELE or other approaches or processes to simplify enrollment |

Study 3: Case Studies of States Adopting ELE and Other Approaches to Simplifying Enrollment and/or Retention |

|||

Key Informant Interviews |

Key informant interviews with state officials, program partners, and other stakeholders |

8 ELE 6 non-ELE |

In-depth information on program design, implementation, and impact |

Focus Groups |

Focus groups with parents of children enrolled via ELE in ELE states and with parents of children enrolled via other simplified pathways in non-ELE states |

2 groups in each of 8 ELE states 2 groups in each of 4 selected non-ELE case study states |

Families’ experience with ELE and traditional enrollment approaches, in ELE states Families’ experience with alternate and traditional enrollment approaches, in non-ELE case study states |

Study 4: Descriptive Study of Costs, Enrollment, and Utilization in Case Study States |

|||

Costs |

Guided discussion with knowledgeable officials using a recording form |

6 ELE states with programs as of December 2010 (Years 1 and 2) 2 additional ELE states (funds permitting) and 6 non-ELE case study states (Year 2) Total: 6 to 8 ELE states and 6 non-ELE case study states |

Total costs of ELE/non-ELE simplification program Per-application costs of ELE/non-ELE simplification versus traditional pathways |

Aggregate Enrollment |

Administrative data gathered directly from states or from centralized sources |

4 ELE states with programs as of December 2010 (Year 1) 2 additional ELE states (funds permitting) and 6 non-ELE case study states (Year 2) Total: 4 to 6 ELE states and 6 non-ELE case study states. |

Net enrollment impact of ELE/non-ELE (total and by demographic group) Numbers enrolled via ELE/non-ELE pathways Baseline characteristics of ELE/non-ELE simplification versus other enrollees |

Individual-Level Enrollment |

Administrative

data |

2 ELE states (MaxEnroll Year 1) 4 ELE states (MSIS Year 2) Total: 6 ELE states |

Same as aggregate enrollment Plus, enrollment outcomes of ELE/non-ELE simplification versus other enrollees |

Utilization |

Administrative data (MSIS) |

4 ELE states (MSIS) (Year 2) |

Baseline utilization of ELE versus other enrollees (ELE renewals only) First-year utilization of ELE versus other enrollees |

a Most primary data collection will touch on all evaluation topics. This column highlights the distinctive focus of each study.

In carrying out the evaluation, we will address several challenges that cut across studies. They include:

Attributing observed changes in enrollment or administrative costs. Even when enough data are available to measure changes in key outcomes such as enrollment and administrative costs, a further challenge arises in attributing these changes to ELE (or other approaches) with a high degree of confidence. Often, for example, the adoption of policies such as ELE can arise simultaneously with other important policies or procedures that, in turn, risk confounding any estimates of ELE effects. In addition, many external and perhaps unobserved changes, such as shifts in economic conditions or changes in the private insurance market may affect Medicaid/CHIP enrollment patterns and further confound estimates of ELE effects. Not all children enrolled via ELE represent new enrollment. Some of these children might have enrolled via another pathway had ELE not been in force.

We will address this challenge via triangulation of multiple data sources. For example, the finding that ELE increases net enrollment in a state will be most convincing if it is observed in both the SEDS and in other enrollment data; if net enrollment gains are concentrated in the populations most likely to use ELE; and if participants in case studies, interviews, and the survey report a consistent story. When findings from various sources are inconsistent, we will probe for answers via additional data analyses or follow-up questions to the extent possible.

Minimizing burden on states and other stakeholders. Central to Studies 1, 3, and 4 is large-scale data collection across multiple states, combining primary data (such as stakeholder interviews and focus groups) and secondary data (such as acquisition of enrollment and cost data). This effort will place a significant burden on the study states, particularly the states that will be part of the cost, enrollment, and utilization study, which requires access to detailed data. Recognizing this burden, we plan to make significant payments to each participating state and will be able to increase these payments if documented efforts exceed our intended payment amount. In addition, we will leverage existing data when possible and only request that states provide data when we cannot access it independently. Finally, as described next, we will ensure linkages across study activities to avoid duplicate requests or asking the same question twice. Still, the evaluation must be careful in all states to balance the study’s data collection needs with the demands they place on state personnel.

Ensuring coordination among studies. In the final reporting, findings from the different analyses must be linked to address research questions as rigorously and thoroughly as possible and to use ASPE and state resources efficiently. We will ensure this coordination in several ways. First, to the extent feasible, we will use a common topical structure across study protocols and interim reports. Such a structure tends to focus the evaluation and makes it easier to integrate findings. Second, we plan to feature key staff across multiple studies to maximize the consistency of our approach and facilitate the synthesis of lessons learned. For example, the task leader of the cost and enrollment study will also be part of the case study team in non-ELE states. Some staff will conduct both ELE and non-ELE case studies, which will improve our ability to compare and contrast ELE versus non-ELE experiences. Third, we will maintain an internal library of study documents (data collection instruments for case studies and interviews, recording forms, case study reports, and documents identified in the information review) catalogued by state. Researchers will review relevant documents before embarking on site visits, interviews, and other discussions with states.

This page has been left blank for double-sided copying.

III. The Technical Advisory Group and its role in the evaluation

Purpose of the TAG

The technical advisory group (TAG) was formed to help guide the design and execution of the congressionally mandated Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) evaluation. The TAG will meet four times over the course of the evaluation to help the research team develop an effective and rigorous design, focus attention on the central policy issues, and assist in interpreting the evaluation’s findings.

TAG Member Selection and Recruitment

To maximize the potential value to the evaluation, TAG members were selected to represent a broad range of stakeholders and to bring diverse ELE perspectives and experiences to the table. Using our knowledge of the relevant design issues to be addressed by the group, we developed and submitted a list of potential TAG members as part of the project proposal. We sought candidates who understood both the policy and operational issues related to ELE, such as enrollment systems, program simplifications, and Medicaid/Children’s Health Insurance program (CHIP) coordination. Potential TAG members were selected from four different strata: ELE state governments, non-ELE state governments, research/policy/advocacy organizations, and the federal government. We refined and expanded our original list with guidance and input from the project officers during the project kickoff meeting. The project officers helped us prioritize selections within each category and to identify potential back-up participants in case the original selection was unable to participate.

After reaching consensus on the list of desired TAG members, we drafted and sent a letter inviting each person to participate in the TAG. The letter described the background of the project and the purpose of the TAG, outlining the commitment needed and remuneration for the member’s assistance. Most of our first-round invitees accepted the invitation to participate in the TAG. If an invitee was unable to participate, we invited our previously identified back-up candidate.3 The list of TAG members appears in Table III.1.

Table III.1. TAG Members

Name |

Affiliation |

State Government Officials |

|

Lesli Boudreaux |

LACHIP

Director |

Gretel Felton |

Director,

Certification Support Division |

Table II.1 (Continued)

Name |

Affiliation |

State Government Officials |

|

Becky Pasternik-Ikard |

Deputy

State Medicaid Director |

Anita Smith |

Bureau

Chief |

Thought Leaders from Private/Nonprofit Sector |

|

Tricia Brooks |

Senior

Fellow |

Anne Dunkelberg |

Associate

Director |

Beth Morrow |

Director

of Health IT Initiatives |

Federal Government Officials |

|

Anne Marie Costello |

Technical

Director, Division of Eligibility, Enrollment and

Outreach |

Vivian Lees |

Branch

Chief, State Systems Support Branch, Child Nutrition

Division |

Jennifer Ryan |

Deputy

Director, Children and Adults Health Programs Group |

Benjamin Sommers |

Senior

Advisor |

C. Methods

Participation in the TAG entails three one-day meetings and one conference call. The first one-day meeting was held at Mathematica’s offices in Washington, D.C., on Wednesday, November 30, 2011. The TAG will reconvene via conference call in May 2012 to review the preliminary findings from the ELE-state cost and enrollment data analysis. The next in-person meeting will occur in November 2012 (week 58) at which members will discuss the progress of the evaluation, including preliminary findings. The final in-person meeting will occur in June 2013, at which we will discuss recommendations coming out of the project and the final report.

D. Initial TAG Meeting

The main topics of discussion during the initial TAG meeting included (1) evaluation objectives, key audiences, and potential challenges; (2) case studies in 14 states; (3) cost and enrollment analysis; and (4) state monitoring, tracking, and selection. The TAG engaged in a lively discussion and provided the evaluation team with valuable feedback and new ideas for consideration. Many of the TAG’s suggestions have been incorporated into chapters throughout this design report.4

E. Next Steps

In general, the TAG’s comments confirmed the overall emphasis and direction of the evaluation. At the same time, the TAG made a number of useful suggestions regarding (1) topics for case studies, quarterly interviews, and 51-state surveys; (2) data fields for the cost and enrollment studies; (3) potential criteria for selecting states as well as states to consider; and (4) how to both raise the quality of data collected and reduce burden on states. The TAG also showed a strong interest in the implications of the ELE experience for federal and state decisions related to the Affordable Care Act. We thus plan to develop recommendations that address, not only federal and state policy options for ELE implementation, but also the lessons ELE holds for successful implementation of the Affordable Care Act. The evaluation team considered all of these discussions when preparing this design report, and insights from the TAG, both major and minor, have been incorporated in the evaluation design.

This page has been left blank for double-sided copying.

IV. Study 1: Ongoing Assessment of the State Policy Context

The first study will document states’ policy context and progress in enrolling and retaining children throughout the evaluation and will consist of three coordinated activities: a baseline information review, tracking and monitoring in 30 states not selected for case studies, and a 51 state survey. Collectively, these activities will build a foundation of knowledge regarding states’ outreach, enrollment, and retention strategies and serve as a point of departure for other study components; for example, the information review will inform the selection of states for non-Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) case studies, and the quarterly data and 51 state survey findings will help inform the interpretation of quantitative data from the Statistical Enrollment Data System (SEDS) analysis. They will complement the case study reports and give us the context to understand what observations from case studies might apply to other states. The remainder of the chapter discusses each of the three components of the study.

A. Baseline Information Review

At the outset of the project, we are reviewing and synthesizing available research, analysis, and descriptive information from states; published literature; and the grey literature (for example, policy organizations and think tanks) to understand states’ experiences in identifying, enrolling, and recertifying eligible children in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Two resources with particularly high value because they cover all 51 states are those collected by the Kaiser Family Foundation, including an annual survey of Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment practices, and the CHIP Annual Reporting Template System (CARTS) data that states submit to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). In addition, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Maximizing Enrollment for Kids program (MaxEnroll) has generated detailed information about innovative practices in eight grantee states.

To carry out our search efficiently, we will first turn to the reputable sources that we know have published articles on the relevant topics, particularly the research partners’ own work. Second, we will use key terms to search Medline and the Grey Literature database, such as “enrollment—Medicaid and CHIP,” “simplification,” “streamlining,” and “renewal—Medicaid and CHIP.” We will search explicitly for “ELE,” as well as other related terms such as “outreach,” “ex parte,” and “data matching.” We will review the products in light of the project’s goals and synthesize the most useful information.

We will prepare a memo with the following elements:

States’ activities pertaining to outreach, enrollment, and renewal for Medicaid and CHIP, as well as the key contextual factors, such as number of eligible but uninsured children,

Summary of the research pertaining to the effectiveness of current outreach, enrollment, and renewal strategies,

Summary of the eight ELE state plan amendments,

Key findings and states to watch, with implications for the other work to be conducted as part of this project, and

Appendices with 51-state tables.

Already, components of the information gathered have been used for the technical advisory group (TAG) meeting.

B. State Tracking and Monitoring

The information review might raise questions or leave gaps in knowledge that would best be resolved via an interview. In addition, over the two years of the project, states’ plans and policies related to outreach, enrollment, and renewal strategies could change in response to shifting priorities and local needs, and in preparation for health reform. We will enhance and maintain our knowledge base by following 30 states closely throughout the project period. In those 30 states, we will stay abreast of state news sources, reading any new articles and tracking states’ web sites to see how their outreach, enrollment, and renewal policies might change. We will also have quarterly calls with a key informant in those states who is likely to be aware of changing policy and progress toward implementing any changes.

1. Selecting the 30 States

The study team, in coordination with the project officers, will identify 30 states for monitoring and tracking of key activities related to identifying and enrolling children in Medicaid, CHIP, and other publicly subsidized health insurance programs. The states will be diverse along a variety of dimensions, such as number of simplifications adopted as well as demographic characteristics.

At the initial TAG meeting, discussed in Chapter III, we shared a table that arrayed states by various features tied to children’s enrollment and retention and asked advisors to identify any additional factors that should be taken into consideration in selecting states, such as innovations in enrollment or renewal not captured in existing documents. Using the table as a guide, the TAG broadly recommended that we select states that are both highly and less active in pursuing simplifications. The TAG also recommended we select a mix of states with high and low numbers of uninsured children. TAG members made some further, more specific recommendations on states to select, pointing to the value of using states already participating in other studies, which could facilitate low-cost access to data. These recommendations will be reflected in the list of states that we will submit to the project officers as the first milestone to this activity.

We also discussed with the TAG the value of including the case study states, both ELE and non-ELE, in the quarterly calls. Many TAG members agreed there would be value to having ongoing contact with these states (presumably selected because they are the states of greatest interest/the most to learn from their experiences). However, upon further consideration, we identified three reasons that the 30 states exclude all of the 14 case study states. First, we have an overarching concern about burden on participants. We are already asking all states to participate in an online survey; to ask a subset of 14 states to participate in an additional case study, a quarterly call focused on ELE and simplification issues, and the cost and enrollment study, seems burdensome and would pose a formidable hurdle for securing Office of Management and Budget (OMB) clearance. Second, we cannot envision a way that the case study protocols and the quarterly monitoring call protocols could be mutually exclusive and still gather the data necessary for understanding the pertinent issues. Thus in the case study states, the quarterly call would seem duplicative of the information we gather on site (and vice versa). Third, and perhaps most importantly, it expands the number of states on which we will gather information: by excluding the 14 case study states and focusing the quarterly calls on 30 separate states, our study will gather in-depth information on 44 states. We think this advantage—of gathering more on-the-ground data from more states—is beneficial in trying to understand the evolution of state policies regarding enrollment and retention simplification and the outcomes of related policy changes. Given this approach, identifying the 30 states for quarterly calls will, in some ways, become a process of identifying which 7 states we will not collect data on. This is likely to be an easier task, given some states have adopted few simplifications and are not considered innovators when it comes to CHIP enrollment and retention. However, the TAG did point out that the 30 states may “self-select,” as some among the 30 selected states may decline to participate, and so we may need to dig into those 7 remaining states as back-up states.

2. Selecting Key Informants

Because resources permit only a single respondent per state in the quarterly calls, we plan to focus these interviews on those who would be best informed and have the most accurate information about state policy decisions. Thus, our targets in states will be a government official with responsibility for developing and implementing enrollment and renewal policy. This might be the state Medicaid or CHIP administrator, eligibility policy director, or another high-level health policy official who has been directed to lead this work. We maintain a list of Medicaid and CHIP directors and will use this as a starting point for identifying our interviewees together with our knowledge of the states, the focal point of eligibility and enrollment activity, and recommendations from others in the state.

We appreciate the value in bellwether or alternate approaches, which might seek respondents with broader perspectives on health policy or individuals outside government; however, in our experience, these approaches work best when the resources exist to interview multiple respondents in a single state, enabling us to cover all topics with many respondents and to triangulate the information to be sure of what is factual and what is subjective. After discussion, ASPE officials agreed with this approach. However, should state officials be unavailable or unwilling to participate, we agree that individuals outside government, such as representatives of organizations in the State Fiscal Analysis Initiative, might be acceptable alternatives. If alternatives are needed, we can discuss these with ASPE on a case by case basis.

3. Key Informant Interviews

Upon OMB approval of the interview protocol, we will recruit a key informant within each of the 30 selected states. We will invite the key informant to participate in the study and confirm his or her availability for quarterly calls. Initially, the first call is likely to be lengthy (up to one hour), but we anticipate that subsequent calls will be much shorter (on average, about 15 minutes), particularly because state policies and processes usually change more slowly than every three months.

The study team will email a short list of questions based on the approved protocol to the key informants before each call. We will tailor follow-up questions to each state’s policy context and will design them to learn about progress toward planning, implementing, and operating activities that identify and enroll eligible children, as well as efforts to measure administrative efficiencies and impacts on Medicaid and CHIP enrollment trends. The quarterly key informant interviews will enable the study team to obtain the following information from the 30 states:

Plans for developing new activities and policies that will improve identification and enrollment of children in Medicaid, CHIP, and other publicly subsidized health insurance programs,

Updates on progress of implementation efforts currently under way, including the identification of administrative or policy barriers, efforts to overcome them, and states’ perceived outcomes,

Any newly available findings related to measuring the impact of identification and enrollment activities that are in operational phase, and

Findings will be organized by state and by theme using an in-house database developed for this purpose. We will work with the full evaluation team to identify key themes and be consistent across interviews and case study components in describing state activities related to these topics. In this way, we hope to maximize the connections among all the evaluation components.

4. Quarterly Reports

The study team will submit a quarterly report summarizing the latest developments in each of the 30 states. We also will use the quarterly reports to inform the interpretation of the enrollment data from SEDS, to provide more context for all of the case study reports, and as part of the final syntheses produced. Because the first quarterly report will be due in March 2012, before OMB approval of the protocol, we will use only publicly available information in it, relying heavily on findings from the information gathering.

C. 51-State Survey

We will conduct a survey of Medicaid and CHIP administrators in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, which will do the following:

Identify and catalog outreach strategies used by states and supplement existing knowledge of states’ enrollment and renewal practices, beyond information captured in existing surveys,

Gather findings from states’ own analyses of the effectiveness and efficiency of these approaches,

Understand states’ perspectives on the value of ELE and non-ELE approaches, including determining the ongoing barriers to enrollment in ELE states,

Determine states’ views of the implications of their enrollment and retention strategies on the upcoming Medicaid expansion populations, and

Identify ways that ELE effectiveness could be improved

We will conduct the survey electronically, using a custom-designed internet-based survey running on a Dataweb platform. The survey will include questions with multiple-choice response options; branched questions (for example, depending upon answers, the respondent will be directed to particular follow-up questions or skip others); and an opportunity for the respondent to provide additional information, including statistics, in a comment box for several questions. The breadth of information might necessitate completing the survey in multiple sessions or by multiple respondents within the state agency; therefore, we will structure the survey instrument so it can be saved and re-opened by the same or a different individual.

To optimize state participation, we will send a personalized letter to each state Medicaid and CHIP director by email, including an explanation of the purpose of the survey and the manner in which findings will be used. This email message will include the Internet link to the instrument and our contact information in case the respondent has questions regarding the instrument. We will monitor the response site regularly and will send at least two follow-up emails to non-responders during the field period. The survey instrument web site will be available for four weeks after the second email. It is possible, if we have to make reminder calls to respondents, that we will keep the site live for a slightly longer period to increase response rates. Our experience with similar surveys indicates that this is likely the case, and we have planned for this contingency.

The structural design of our survey in Dataweb will enable us to compile responses in a database. We will then review, clean, and analyze the data to determine themes and other findings relevant to key research questions. We will focus on key themes from other components of the study, including strengths and weaknesses of current approaches and considerations for new policies. We will compile and analyze the survey responses, looking for patterns and trends (for example, program-level trends, with certain responses more likely among CHIP than Medicaid directors or vice versa; policy trends that might vary along geographic or other lines; and so on), with a draft memo of findings submitted to the project officers. We will address feedback from the project officers and make revisions within one week of receiving the comments. We will use these findings to develop recommendations and to give input to the team. Findings will be incorporated into the Final Report to Congress.

We are mindful of the time frame requirements associated with this survey and of the need for OMB clearance, which could require 120 days or more. To maintain this schedule, we will provide a draft of the survey instrument and personalized letter template by January 20, 2012, as agreed at the initial meeting. Upon receipt of comments from the project officers, and other reviewers as appropriate, we will immediately revise the clearance package for ASPE’s submission to OMB. We will make additional revisions as necessary for final approval, based on comments received from both the general public and OMB during the clearance process.

This page has been left blank for double-sided copying.

V. Study 2: Analysis of ELE Impacts on Enrollment (Using SEDS)