Form 1 Organizational Capacity Assessment Instrument

Generic Information Collection Request for Test and Pilot Data

CNCS OCAT

Organizational Capacity Assessment

OMB: 3045-0163

Organizational

Capacity Assessment Tool

This

tool was developed for the Corporation for National and Community

Service by ICF under contract #CNSHQ16T0073.

This

tool was developed for the Corporation for National and Community

Service by ICF under contract #CNSHQ16T0073.

Contributing Authors:

Adrienne DiTommaso

Bethany Slater

Joe Raymond

Venessa Marks

Nanette Antwi-Donkor

Trevor Hoffberger

Suggested citation: Corporation for National and Community Service (2017). Organizational Capacity Assessment Tool. Washington, D.C.: Author.

The Corporation would like to thank the following people for serving on a Technical Working Group, advising the authors in the development of this tool: Isaac Castillo, Robert Cox, Meghan Duffy, Anthony Nerino, Chukwuemeka Umeh, and Lily Zandmiapour.

The Corporation would also like to thank the many organizations that participated in the pilot testing and validation of this tool.

Table of Contents

Key Domains of Organizational Capacity 4

Management & Operations Capacity 11

Infrastructure & Information Technology 12

Community Engagement Capacity 14

Measuring Outcomes & Impact 21

Learning & Continuous Improvement 21

Appendix A – Scoring Rubric 23

Introduction

Defining Key

Terms

Organizational

effectiveness: The ability of an

organization to fulfill its mission through effective leadership

and governance, sound management, and the alignment of measurable

outcomes with strategies, services, resources and partners.

Organizational

capacity: The wide

range of capabilities, knowledge, and resources that organizations

need in order to be effective. Capacity

assessment: The use of a standardized

process or formal instrument to assess facets of organizational

capacity and identify areas of relative strength and weakness. Capacity

building: Internal and/or external

strategies, use of resources or technical

assistance to strengthen an organization’s capabilities to

enhance organizational effectiveness.

Adapted

from Grantmakers

for Effective Organizations. (2016). Strengthening nonprofit

capacity: Core concepts in capacity building.

Washington, DC: Author.

Key Domains of Organizational Capacity

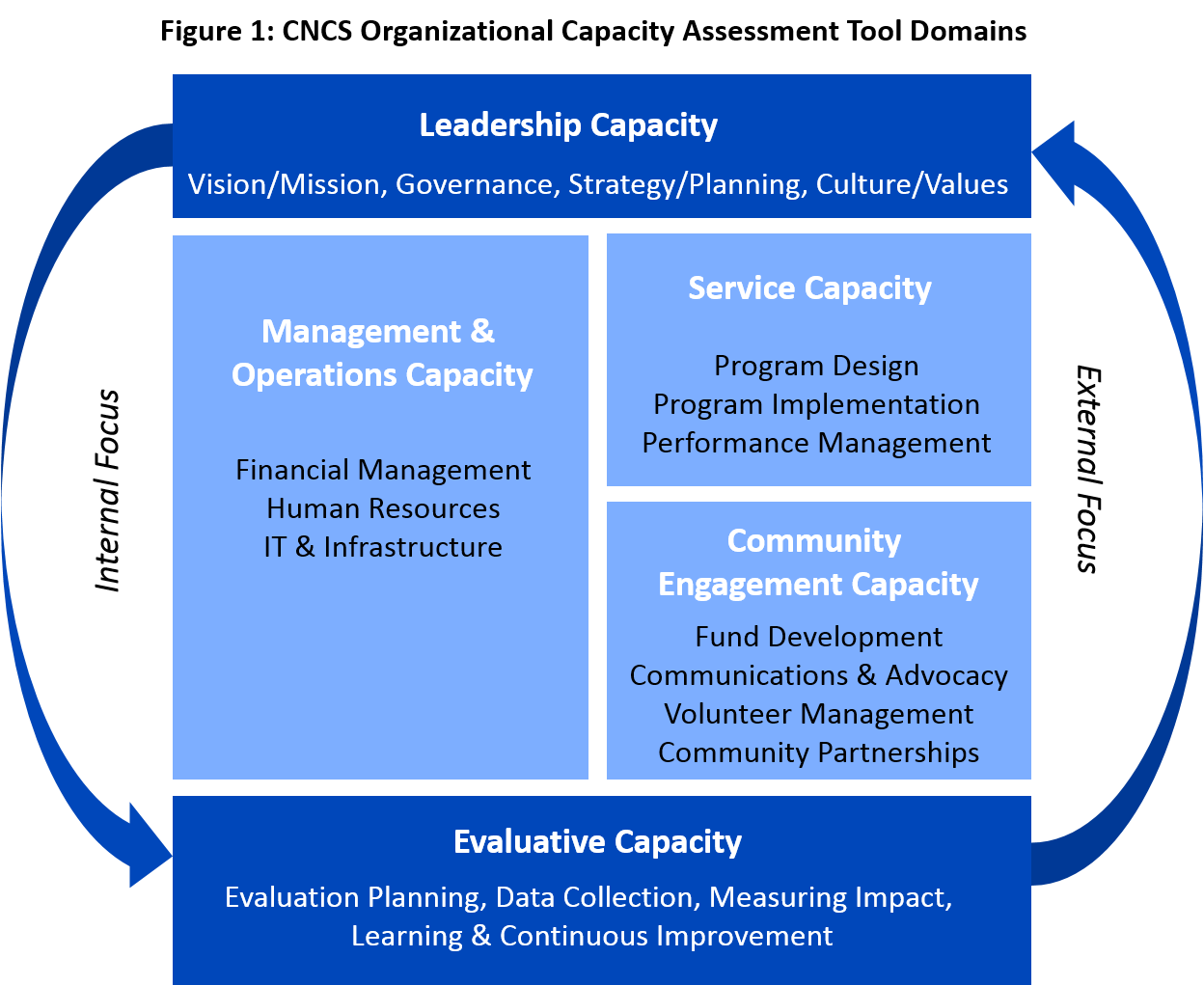

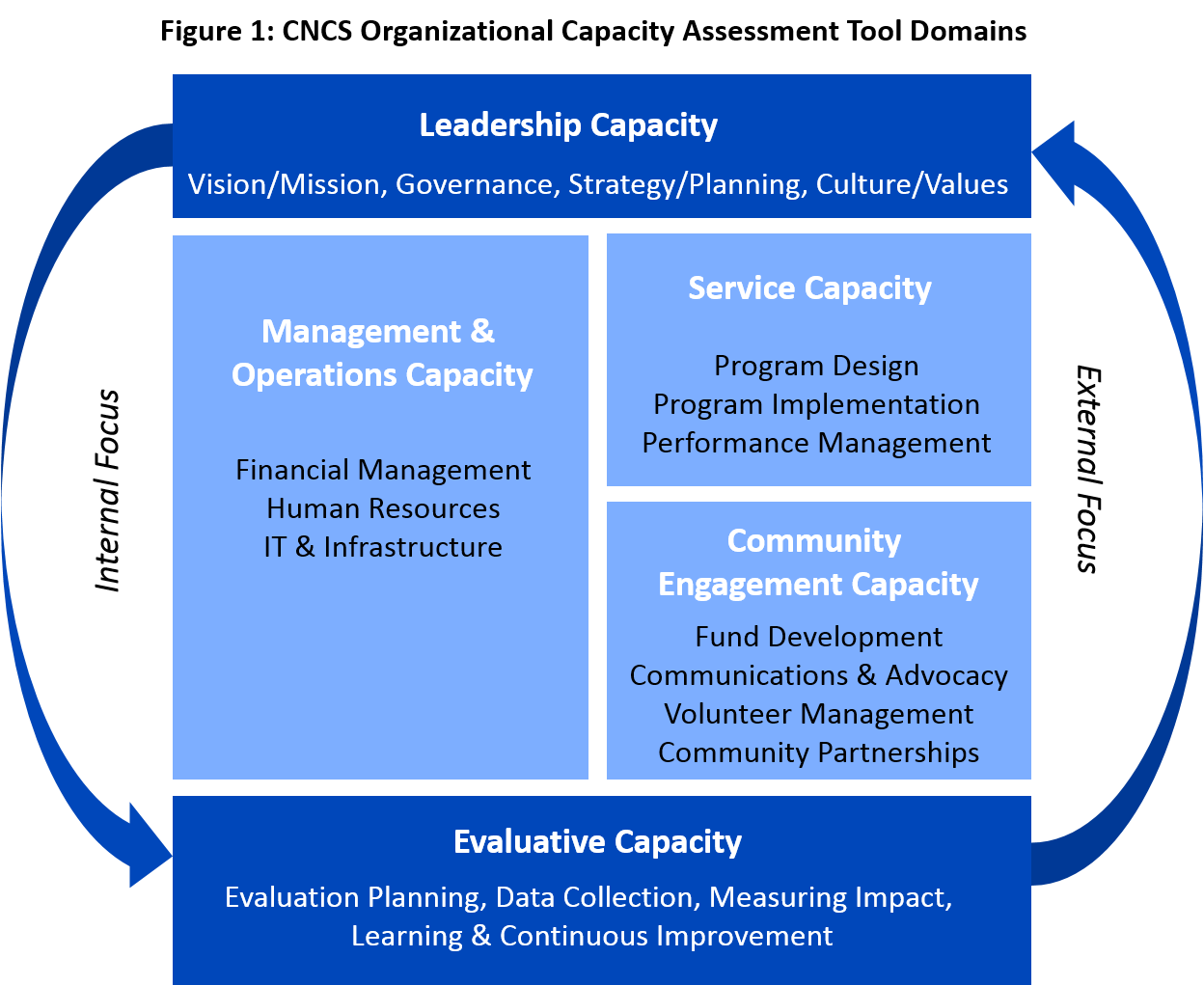

To develop this tool, CNCS commissioned an extensive review of the research literature on capacity assessment and analyzed leading and widely used assessment tools available in the marketplace. In developing the domains and subdomains, CNCS aimed to take a straightforward, functional approach – using terms common in nonprofit management and organizing the domains based on typical job functions. CNCS also considered domains and subdomains that may be particularly important for CNCS-funded organizations, including volunteer management, community engagement, and evaluative capacity. Figure 1 diagrams these domains relative to their internal versus external focus. Leadership and evaluative capacity are overarching domains that set the strategy for the organization and drive organizational culture. Management and operations capacity includes more internal functions, while service and community engagement capacity are primarily externally facing. Each of these domains is described in greater detail in the following sections of this tool.

Using this Tool

This tool provides a practical approach to beginning or enhancing an organization’s understanding about its capacity strengths and areas where its capacity might be enhanced. Organizational capacity is complex and fluid – it changes over time and perceptions of capacity often differ within and across organizations. For this reason, CNCS recommends that organizations invite multiple individuals within the organization to complete this assessment and then discuss results – including any differences of opinion. Team members well positioned to provide insight on organizational capacity include the CEO/Executive Director, members of the Board of Directors (or comparable entity), leadership team members, and managers. External stakeholders – such as volunteers, partners, or service recipients – may also provide a valuable perspective on all or sections of this assessment tool. Diversity of opinion may indicate misunderstandings that can be easily addressed or may reveal areas where there is more work to be done. The tool may also reveal strong areas of capacity to acknowledge and to be sustained.

Appendix A offers a scoring worksheet to enable you to identify domains and subdomains of capacity that might particularly benefit from capacity-building efforts. To simplify and streamline scoring, all questions are framed negatively – requiring you to simply check off whether or not a specific capacity is a challenge or gap for your organization.

This tool has been validated for use with a wide variety of organization types: national and local nonprofits; state, local and tribal government; institutes of higher education; and funders and intermediary organizations. If a question is not appropriate for your organization, simply skip that question and note its exclusion in your scoring calculation.

The tool was also designed to enable organizations to assess changes to capacity over time. Consider taking and retaking this assessment on an annual or biannual basis to track how organizational capacity strengths and needs are changing over time.

Capacity building takes time and effort. This capacity tool can be a critical first step in increasing basic understanding about capacity and prioritizing potential capacity-building efforts. The suggested resources at the end of each domain section can provide a helpful starting place to learn more about effective practices for organizational development.

Leadership Capacity

This domain focuses on capacity functions that are typically the responsibility of senior leadership and executive board members (in the case of nonprofits) to guide or execute. Markers of effective organizational leaderships include:

Vision & Mission: An organization’s vision and mission statements articulate its sense of purpose and direction (McKinsey, 2001). Effective vision and mission statements set parameters for what the organization will and won’t do; inspire staff, volunteers, and donors; and set the basis for strategy (Paynter & Berner, 2014; Smith, Howard, & Harrington, 2005; McKinsey, 2001).

Leadership & Governance: An organization’s governance model and function is a critical component for organizational functioning and sustainability (Liket, 2015). For nonprofits with executive boards, clear separation between the board and the organization’s leadership and documented roles and responsibilities are important (Liket, 2015). Research also suggested that the professional diversity, ability to fundraise, and size of the board can impact nonprofit effectiveness. Note: organizations that do not have an executive board or suitable proxy should skip questions pertaining to an executive board.

Strategy & Planning: If an organization’s vision and mission establish its aspirations, its strategy articulates the means for achieving those goals (McKinsey, 2001). Research has shown that strategic planning—the process of mission review, stakeholder analysis, and visioning coupled with the development of resource allocation strategies—boosts organizational capacity (Bryson, Gibbons & Shaye, 2001; Paynter & Berner, 2014).

Culture & Values: An organization’s culture impacts every aspect of its functioning—from how leaders interact with board and staff to how staff members respond to external or internal challenges. Building a strong values-based culture is a strategic and often difficult process that must be led and modeled by organizational leadership. Organizational culture is typically divided into three interrelated components: core values, beliefs, and behavior norms (McKinsey, 2001). Cultural competency, diversity, equity and inclusion are critical components of a strong organizational culture.

Vision and Mission

|

|

|

Our vision statement does not describe the future our organization intends to achieve. |

|

|

|

Our mission statement does not clearly define what we want to achieve and for whom. |

|

|

|

Not all staff fully embrace or could clearly describe our vision and mission to individuals who have never heard of our organization. |

|

|

|

Organizational decisions are sometimes not reflective of the mission and vision of the organization and detract from its fulfillment. |

Leadership & Governance

|

|

|

The board does not have an adopted set of bylaws that define its essential responsibilities and comply with federal and state statutes. |

|

|

|

The board does not adopt and regularly review an annual set of organizational strategic goals and measurable outcomes. |

|

|

|

The board does not adopt an annual budget aligned with its strategic goals and measurable outcomes. |

|

|

|

The board does not regularly update and adopt a set of policies to govern the organization in the areas of finance, human resources, fund development, and communication. |

|

|

|

The board does not evaluate the performance of its CEO on regular basis. |

|

|

|

The board does not evaluate its performance on a regular basis. |

|

|

|

Our board does not have the right mix of skills and expertise to govern the organization and routinely consider diverse points of view from internal and external stakeholders. |

|

|

|

The composition of our board does not reflect the community we serve. |

|

|

|

Board members do not have the knowledge they need about the organization and current issues relevant to our organization to make effective policy decisions. |

|

|

|

Few or none of the board members are effective at getting others in the community to invest time, money, or other resources in our organization. |

Strategy & Planning

|

|

|

Our organization does not have a written strategic plan1 that includes a clear, specific, and measurable set of goals2 and objectives3 to ensure success. |

|

|

|

Our organization does not formally share progress on the strategic plan’s goals and objectives with board and staff members on a regular basis. |

|

|

|

Our organization either did not solicit or did not use external stakeholder input as it developed its strategic plan. |

|

|

|

The board either has not reviewed or has not approved the existing strategic plan in the last 12 months. |

|

|

|

Our organization has too many priorities and our capacity is insufficient or stretched too thin to achieve all of our goals. |

|

|

|

Implementation of the action steps in our strategic plan are significantly behind schedule. |

|

|

|

Our overall strategy is not broadly known and has limited influence over day-to-day behavior. |

|

|

|

There is a lack of clarity on how to make decisions when priorities come into conflict with each other. |

|

|

|

Our organization has a history of failure to meet program or organizational goals and benchmarks. |

Culture & Values

|

|

|

Our organization does not have a common set of basic beliefs and values that are written, shared broadly, and held by all or the majority of staff. |

|

|

|

Our organization does not provide regular opportunities for staff to express constructive feedback or concerns to leadership. |

|

|

|

Many staff are not culturally sensitive with respect to internal management or delivery of services. |

|

|

|

Our organization invests little time or resources in reflection or learning. |

|

|

|

Our organization does not openly embrace diversity of race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, ability, and other facets of human identity. |

|

|

|

The demographics of our staff do not represent the population which it serves. |

The

Strategic Plan is Dead. Long Live Strategy, by Dana O’Donovan

and Noah Rimland Flower. Stanford Social Innovation Review. January

10, 2013.

Boards

that Make a Difference: A New Design for Leadership in Nonprofit

and Public Organizations, by John Carver. December 10, 2007.

Trying

Hard is Not Good Enough: How to Produce Measurable Improvements for

Customers and Communities, by Mark Friedman. March 8, 2015.

Resources to

build leadership capacity

Management & Operations Capacity

This domain focuses on internal-facing capacities, including the capacity of an organization to manage its finances, recruit, develop and retain talent, and maintain critical infrastructure and systems. Markers of effective management and operations include:

Financial Management: Beyond the ability to just manage a budget, financial capacity is the ability of an organization to align its financial capital with the strategic plans and mission of the organization (Paynter & Berner, 2014, Misener & Doherty, 2009). Effectively managing resources is critical for mission fulfillment, yet many capacity assessment studies have revealed that direct service providers are frequently troubled by insufficient financial management capacity. Effective organizations have the skills and systems necessary relative to its size and revenue base for financial planning, accounting, budgeting, and other activities to ensure financial health.

Human Resources: Human resource capacity is the ability to effectively recruit, manage, develop, and retain staff within an organization. Researchers have argued this dimension is in fact the key element that directly impacts all other organizational capacities, and is often seen as a strength in nonprofit and voluntary organizations (Hall et al., 2003; Misener & Doherty, 2009). Staff structures and roles are also often used to approximate organizational maturity, with more developed organizations having more specialized and defined staff functions (Schuh & Leviton, 2006). Effective organizations have policies and procedures for staff recruitment, management and supervision, development and training, succession planning and leadership development, compensation, and staff retention.

Infrastructure & Information Technology: Infrastructure refers to the tangible property/goods and facilitates staff members need to do their jobs. Effective organizations have sufficient infrastructure to facilitate the day-to-day functions of the organization. As organizations become more dependent on technology for day-to-day operations, many organization struggle to ensure that they have the right systems in place, adequately maintain those systems, and ensure staff have adequate training to use IT systems such as databases, websites, hard and software.

Financial Management

|

|

|

Our organization does not have an up-to-date fiscal policy and procedures manual. |

|

|

|

Our organization does not compare actual with budgeted expenses each month. |

|

|

|

Our operations plan and annual budget does not align with our current strategic plan. |

|

|

|

Our organization rarely reforecasts year-end revenue and expenses to assist in making management decisions. |

|

|

|

Our organization does not effectively manage its finances (e.g. does not have balanced books, appropriate internal controls, on-time accounts payable, an adequate reserve fund, or has had year-over-year deficits, etc.). |

Human Resources

|

|

|

Our organization does not have written human resource policies that have been approved by the board and explained to staff. |

|

|

|

Staff are not given constructive feedback from managers/supervisors on a regular basis. |

|

|

|

Our organization does not routinely assess workloads to ensure adequate resources are available to meet performance objectives. |

|

|

|

Our organization does not have an adequate total compensation system4 on par with other similar organizations for personnel, which includes salary standards, retirement benefits, healthcare, and systems for bonuses, awards, or recognition of high performance. |

|

|

|

Our organization does not fill open positions with highly qualified applicants in a timely manner. |

Infrastructure & Information Technology

|

|

|

Our organization does not have the right facilities (e.g. space, equipment, office supplies) to implement our program(s) and achieve our mission. |

|

|

|

We do not have sufficient expertise (on staff or through volunteers, consultants) to effectively and efficiently run and manage our technology systems. |

|

|

|

Our staff does not have the necessary hardware (e.g. computers) and software (e.g. word processing systems, database systems) to do their jobs consistently, efficiently, and effectively. |

|

|

|

Our staff does not have the necessary hardware (e.g. computers) and software (e.g. word processing systems, database systems) to do their jobs consistently, efficiently, and effectively. |

|

|

|

Important data and files are not frequently backed up (at least once per month). |

Resources to

build management and operations capacity

Managing

to Change the World: The Nonprofit Manager’s Guide to Getting

Results, by Alison Green and Jerry Hauser. Jossey-Bass. 2012.

An

Executive Director’s Guide to Financial Leadership, by

Kate Barr and Jeanne Bell. The Nonprofit Quarterly. Fall/Winter

2011.

Financial

Management for Human Service Administrators, by Lawrence

Martin. May 5, 2016.

Community Engagement Capacity

This domain is primarily external facing, focusing on an organization’s capacity to draw on strategic relationships with funders, community partners, corporations, media, and individuals to access resources and expertise and leverage time and in-kind contributions. Markers of effective community engagement include:

Fund Development: The lack of core, stable, long-term funding is often noted as the greatest challenge to the development of organizational capacity (Hall et al., 2003). Uncertainties about future funding and constraints on how funds can be used can have a significant impact on the ability of an organization to plan strategically—or to execute those plans (Misener & Doherty, 2009). Organizations that are more mature in their fund development capacity have provisions for covering overhead costs, routinized or formalized fundraising activities (such as annual campaigns or events), and will have a more diverse or strategic array of funding sources (Schuh & Leviton, 2006).

Communications & Advocacy: Increasingly in the digital age, effective and transparent communications are considered essential to nonprofit effectiveness (Liket, 2015). Communications capacity includes an organization’s marketing skills, online presence, media relations, and use of social media to raise awareness, advocate and attract resources to an organization or issue (Grantmakers for Effective Organizations, 2016b). Transparency is often judged by the organization posting its strategic plan, annual and financial reports online and providing a list of executive board members on its Web site (Liket, 2015).

Volunteer Management: Many small community-based nonprofits as well as larger organizations rely on volunteers to deliver services or cover other essential staff functions. Indeed, for some small community-based organizations, the commitment of volunteers can be more important than other capacity areas such as infrastructure (Paynter & Berner, 2014). Effective volunteer management requires the development and execution of effective recruitment, screening, training, and retention strategies.

Community Partnerships: Partnership capacity includes the skills and mindset to create and sustain relationships with peer organizations, government, corporations, and other key stakeholders to advance the organization’s mission (Grantmakers for Effective Organizations, 2016b). Many direct service providers rely on organizations with complementary services to meet the holistic needs of their clients. Volunteer-based organizations often heavily rely on religious organizations or corporations to help recruit volunteers or provide in-kind donations.

Note: some of these subdomains and questions will not be applicable to all organizational types. If a question does not apply to your organization, simply skip it and take that into account as you score your responses in Appendix A.

Fund Development

|

|

|

Our organization is overly dependent on a small number of funders or funding streams. |

|

|

|

We have difficulty identifying and cultivating new funders. |

|

|

|

Our organization has insufficient discretionary funds independent of project-specific or restricted funds. |

|

|

|

We do not have a viable fundraising plan that was developed in the last 12 months. |

Communications & Advocacy

|

|

|

Our organization does not have an up-to-date external communications strategy 5 that addresses crisis communications, marketing, and public relations. |

|

|

|

Our organization has outdated communications tools and messages. |

|

|

|

Our materials or website do not reflect the quality of our organization. |

|

|

|

We have limited or no social media presence. |

|

|

|

Our organizational leaders are rarely asked by other community or nonprofit leaders to provide leadership, knowledge, or advice on community-level issues. |

Volunteer Management

|

|

|

Our organization does not have a written volunteer recruitment and management plan. |

|

|

|

Our organization often fails to recruit the volunteers it needs to provide essential services. |

|

|

|

Our organization struggles to retain volunteers. |

|

|

|

Volunteers often do not know who is managing them. |

|

|

|

Volunteers often do not understand their role in the organization. |

|

|

|

Volunteers do not always receive the resources, support, and training they need to do their job. |

|

|

|

Our organization often struggles to recruit the right mix of volunteers (e.g. with the right skill sets, with backgrounds reflective of the community, etc.). |

Community Partnerships

|

|

|

Our organization spends insufficient time meeting, interacting, and collaborating with community members, program participants and leaders for the purposes of learning about what is going on in the community. |

|

|

|

We have had limited engagement in partnerships due to a lack of awareness or inability to take advantage of real partnership opportunities. |

|

|

|

We have spent so much time on partnership work that it interferes with our ability to implement important goals. |

|

|

|

We have focused efforts on partnership work or networking that is not mission aligned. |

|

|

|

Our organization has paid little attention to assessing the results of key partnerships, alliances or participation in networks. |

Resources to

build community engagement capacity

Ten

Nonprofit Funding Models, by William Foster, Peter Kim, and

Barbara Christiansen. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Spring

2009.

Twenty-First-Century

Communications versus the Illusion of Control: An Epic Battle,

by Ruth McCambridge. Nonprofit Quarterly. August 27, 2014.

Working

Better Together: Building Nonprofit Collaborative Capacity, by

Grantmakers for Effective Organizations. 2013. Management

of Human Service Programs, by Judith A Lewis, Thomas R Packard,

and Michael D Lewis. August 15, 2011.

This domain focuses on the capacity of the organization to design research-informed programs, monitor and support quality implementation, and make course corrections as needed. Markers of service effectiveness include:

Program Design: Programs are more likely to produce reliable, positive outcomes for their clients if they use evidence-based practices and have a clearly articulated logic model and/or theory of change (Easterling & Metz, 2016). A critical element in strong program design includes taking steps to understand and document relevant community and individual-level needs and assets. Community needs assessment, asset mapping, and focus groups with potential clients and key stakeholders are all strategies that can assist organizations in designing (or refining) programs that are responsive to client needs and the larger community environment (Sharpe, Greaney, Lee, & Royce, 2000).

Program Implementation: Program implementation is more effective and sustainable if it is documented, monitored, and well-coordinated with other program or organizational functions. Policy and procedure manuals provide evidence of a structured, step-by-step approach to programming and are an essential knowledge and risk management tool (Paynter & Berner, 2014). Coordination across functional teams or other interagency programs can keep programs from operating in silos and reduce inefficiencies. Finally, monitoring fidelity to policies and practices or evidence-based programs (if applicable) is essential for ensuring that programs are providing services as intended (Easterling & Metz, 2016).

Performance Management: Although related to evaluative capacity, performance management capacity focuses on the organization’s ability to identify, collect, and monitor key performance indicators (KPIs) directly related to service provision. These KPIs are typically program activities and outputs that provide real-time input on how and whether the program is being implemented and clients are participating as intended (Parmenter, 2015).

Program Design

|

|

|

We do not have a clear understanding of how our resources and strategies will result in our intended outcomes. |

|

|

|

Our program design is not grounded in the best and most recent available research literature. |

|

|

|

National service members and/or volunteers are not explicitly included in our logic model or theory of change. |

|

|

|

Our organization has minimal knowledge or understanding of other or alternative program models in our field. |

|

|

|

Our organization’s clients/participants do not provide input or feedback on our program design or implementation. |

|

|

|

Our organization does not conduct regular assessments of our clients’ needs. |

|

|

|

Our new programs are created largely in response to funding availability, rather than client needs and community service gaps. |

Program Implementation

|

|

|

Policy and procedure6 documents are out-of-date or insufficient to provide staff guidance on current program practices. |

|

|

|

Insufficient financial or staffing resources are allocated to ensure strong program implementation. |

|

|

|

Not all of our program staff have the required knowledge, experience or skills to implement our program in a manner that will achieve the greatest positive effect. |

|

|

|

Staff members with different roles rarely have the time to meet and share their work, coordinate their work, or develop ideas for working together. |

|

|

|

Program leadership do not regularly monitor fidelity to program design7 or adaptations8 made in implementation. |

|

|

|

Staff members do not have a clear understanding of the program logic model9 or the relationship between implementation and expected outcomes. |

Performance Management

|

|

|

Our program does not have clearly defined key performance indicators.10 |

|

|

|

Key performance indicators are not reviewed and discussed by organizational or program leadership regularly (at least biannually). |

|

|

|

Internal performance data is rarely used to improve the program or organization. |

|

|

|

Our organization rarely or never compares our program performance with relevant external programs. |

Within

Our Reach: Breaking the Cycle of Disadvantage, by Lisbeth B.

Schorr. March 23, 2011.

Designing

and Managing Programs: An Effectiveness-Based Approach, by

Peter Kettner, Robert Moroney, and Lawrence Martin. January 20,

2016.

Resources to

build service capacity

This domain focuses on the capacity of an organization to gather data, measure impact, and assess lessons learned in order to strengthen the organization’s work over time. Markers of evaluative capacity include:

Evaluation Planning: Organizations with strong evaluative capacity develop a systematic plan for evaluation activities with the full engagement and support of senior management (Bourgeois, 2013). Execution of the evaluation plan may be the responsibility of internal evaluators and staff or external consultants.

Data Collection: The capacity to collect quality data is often indicated by clear data collection protocols that identify who is collecting what data, when, from whom, and for what purpose (Grantmakers for Effective Organizations, 2016b). Without high-quality data collection, the value of analysis is questionable at best.

Measuring Impact: Organizations are best positioned to measure their impact if they are using validated or research-based outcome assessment tools that align with their service intervention and their short- and long-term intended outcomes (Grantmakers for Effective Organizations, 2016b). Programs that have participated in a quasi-experimental or randomized control trial will have a better understanding of the degree to which their client outcomes can be attributed to their intervention.

Evaluation Use, Learning & Continuous Improvement: Organizations that maximize their learning from evaluation activities and use that information to drive continuous improvement tend to share similar characteristics: (1) they openly and widely share their evaluation findings with internal and external stakeholders; (2) they link their evaluation process to other organizational decision-making processes; and (3) they recognize the value of empirical data in decision-making and problem-solving (Bourgeois, 2013).

Evaluation Planning

|

|

|

Our organization has not developed or not revisited a systematic plan within the past three years that defines the purpose of our evaluation efforts and our methodology, outlines our evaluation activities, and establishes clear responsibilities. |

|

|

|

Our senior leadership does not prioritize evaluation and does not routinely dedicate resources to it. |

|

|

|

Our organization has not engaged an internal or external experienced evaluator to design or implement the evaluation plan. |

|

|

|

Our organization dedicates insufficient resources for evaluation. |

Data Collection

|

|

|

Our organization does not have clear protocols11 for data collection. |

|

|

|

Our organization does not provide regular staff training on how to use data collection protocols. |

|

|

|

Organization does not have sufficient or effective data collection systems.12 |

Measuring Outcomes & Impact

|

|

|

Our organization does not internally evaluate the effect of our program(s). |

|

|

|

The questions in our evaluation instruments13 are not clearly stated. |

|

|

|

The questions in our evaluation instruments are not in line with our proposed methods of evaluation and program design. |

|

|

|

Our organization has not participated in a high-quality external evaluation to assess the degree to which participant impact can be attributed14 to the program intervention, such as a quasi-experimental study15 or a randomized control trial.16 |

Learning & Continuous Improvement

|

|

|

Staff have low levels of knowledge about evaluation and its benefits across the organization. |

|

|

|

Evaluation findings are not openly and widely shared with key stakeholders.17 |

|

|

|

Our organization makes limited use of internal evaluation data to make decisions regarding organizational strategy or fiscal allocations. |

|

|

|

Our organization makes limited use of external research to make decisions regarding organizational strategy or fiscal allocations. |

|

|

|

No systematic evaluation recommendation follow-up process is in place. |

Resources to

build evaluative capacity

The

Challenge of Organizational Learning, by Katie Smith Milway and

Amy Saxton. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Summer 2011.

Building

a Strategic Learning and Evaluation System for Your Organization,

by Hallie Preskill and Katelyn Mack. FSG. 2013.

Collective

Genius, by Linda Hill, Greg Brandeau, Emily Truelove, and Kant

Lineback. Harvard Business Review. June 2014.

Building

Evaluation Capacity: Activities for Teaching and Training, by

Hallie Preskill and Darlene Russ-Eft. September 15, 2015.

Appendix A – Scoring Rubric

Once

you have completed the assessment, complete this scoring rubric to

identify the areas of greatest strength and need within your

organization. This rubric will allow you to reflect upon the various

aspects of your organization in order to drive capacity-building

efforts. A copy of the domain diagram has been included for your

reference.

Once

you have completed the assessment, complete this scoring rubric to

identify the areas of greatest strength and need within your

organization. This rubric will allow you to reflect upon the various

aspects of your organization in order to drive capacity-building

efforts. A copy of the domain diagram has been included for your

reference.

The table below displays each of the eighteen subdomains examined throughout the assessment. To complete the rubric, follow these steps for each subdomain row:

Tally the number of boxes that you checked within a given subdomain, and record it in the “Number of Checks” column.

If needed, subtract any number of questions skipped due to inapplicability from the “Total Questions” column.

Divide the “Number of Checks” by the “Total Questions.”

Convert your answer into a percentage, and write that number in the far right column.

Subdomain |

Number of Checks |

Total Questions* |

Percentage |

Leadership Capacity |

|||

Vision & Mission |

|

4 |

|

Governance |

|

10 |

|

Strategy & Planning |

|

9 |

|

Culture & Values |

|

6 |

|

Management and Operations Capacity |

|||

Financial Management |

|

5 |

|

Human Resources |

|

5 |

|

IT & Infrastructure |

|

5 |

|

Community Engagement Capacity |

|||

Fund Development |

|

4 |

|

Communications & Advocacy |

|

5 |

|

Volunteer Management |

|

7 |

|

Community Partnerships |

|

5 |

|

Service Capacity |

|||

Program Design |

|

7 |

|

Program Implementation |

|

6 |

|

Performance Management |

|

4 |

|

Evaluative Capacity |

|||

Evaluation Planning |

|

4 |

|

Data Collection |

|

3 |

|

Measuring Impact |

|

4 |

|

Learning and Continuous Improvement |

|

5 |

|

* Subtract any number of questions skipped due to inapplicability from the total in that subdomain.

After completing the table above, briefly reflect upon your results in the space provided. By identifying the three strongest subdomains and the three areas of greatest need, you will be better equipped to address gaps in your capacity.

Which three subdomains appear strongest within your organization (lowest percentage of checked boxes)?

______________________________________

______________________________________

______________________________________

Which three subdomains show the greatest need for capacity-building efforts (greatest percentage of check boxes)? The “Resources to Build Capacity” section at the end of each domain can support your growth.

______________________________________

______________________________________

______________________________________

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013, July 3). Correlation and causation. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/a3121120.nsf/home/statistical+language+-+correlation+and+causation.

Authenticity Consulting, LLC. (n.d.). Nonprofit Organizational Assessment. Retrieved from https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/SVF38MM?sm=nqYAfItd5pCME8J7VJjBQpxt%2b7TXVQBxdZt6z7IiPZg%3d

The Basics of Strategic Planning, Strategic Management and Strategy Execution. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.balancedscorecard.org/Resources/Strategic-Planning-Basics

Bourgeois, I., & Cousins, J. B. (2013). Understanding dimensions of organizational evaluative capacity. American Journal of Evaluation, 34(3), 299-319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1098214013477235

Bryson, J. M., Gibbons, M. J., and Shaye, G. (2001). Enterprise schemes for nonprofit survival, growth, and effectiveness. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 11(3), 271-288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nml.11303

The Denver Foundation. (n.d.) Identifying internal and external stakeholders. Retrieved from http://www.nonprofitinclusiveness.org/identifying-internal-and-external-stakeholders

Easterling, D., & Metz, A. (2016). Getting real with strategy: Insights from implementation science. The Foundation Review, 8(2), 97-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1302

Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, George Washington University. (n.d.). Study Design 101: Randomized controlled trial. Retrieved from https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu/tutorials/studydesign101/rcts.html

Grantmakers for Effective Organizations. (2016). Shaping culture through key moments. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from https://www.geofunders.org/resources/708

Grantmakers for Effective Organizations. (2016). Strengthening nonprofit capacity: Core concepts in capacity building. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from https://www.geofunders.org/resources/710

Hall, M., Andrukow, A., Barr, C., Brock, K., de Wit, M., Embuldeniya, D., … Vaillancourt, Y. (2003). The capacity to serve: A qualitative study of the challenges facing Canada’s nonprofit and voluntary organizations. Toronto: Canadian Centre for Philanthropy. Retrieved from http://www.vsi-isbc.org/eng/knowledge/pdf/capacity_to_serve.pdf

Hovland, I. (2005, January). Planning Tools: How to write a communications strategy. Overseas Development Institute: Shaping policy for development. Retrieved from https://www.odi.org/publications/5186-planning-tools-how-write-communications-strategy

Jackson, T. (2015, March 5). 18 key performance indicator examples defined for managers. ClearPoint Strategy. Retrieved from https://www.clearpointstrategy.com/18-key-performance-indicators/

Liket, K. C., & Mass, K. (2015). Nonprofit organizational effectiveness: Analysis of best practices. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44(2), 268-296. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0899764013510064

McKinsey & Company (2001). Effective Capacity Building in Nonprofit Organizations. Retrieved from https://www.neh.gov/files/divisions/fedstate/vppartnersfull_rpt_1.pdf

McKinsey & Company. Organizational capacity assessment tool (OCAT). Retrieved from http://mckinseyonsociety.com/ocat/

Misener, K., & Doherty, K. (2009). A case study of organizational capacity in nonprofit community sport. Journal of Sport Management, 23(4), 457-482. http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/jsm.23.4.457

Moore, K. A. (2008). Quasi-experimental evaluations: Part 6. Washington, DC: Child Trends. Retrieved from https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/01/Child_Trends-2008_01_16_Evaluation6.pdf

Mowbray, C. T., Holter, M. C., Teague, G. B., & Bybee, D. (2003). Fidelity criteria: Development, measurement, and validation. American Journal of Evaluation, 24(3), 315-340. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/109821400302400303

The NCJA Center for Justice Planning. (n.d.). Goals and Objectives. Retrieved from http://www.ncjp.org/strategic-planning/overview/where-do-we-want-be/goals-objectives

NCVO Knowhow Nonprofit. (2016, July 1). Employment policies and procedures. Retrieved from https://knowhownonprofit.org/people/employment-law-and-hr/law-and-hr-basics/policies

Parmenter, D. (2015). Key performance indicators: Developing, implementing, and using winning KPIs (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Paynter, S., & Berner, M. (2014). Organizational capacity of nonprofit social service agencies. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 37(1), 111-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.18666/JNEL-2016-V6-I2-6499

Program Sustainability Assessment Tool. (n.d.). Program adaptation. Retrieved from https://sustaintool.org/understand/program-adaptation.

Faculty Development and Instructional Design Center, Northern Illinois University. (2005). Data collection. Retrieved from https://ori.hhs.gov/education/products/n_illinois_u/datamanagement/dctopic.html

Rutgers University. (n.d.). Developing a survey instrument. Retrieved from http://njaes.rutgers.edu/evaluation/resources/survey-instrument.asp

S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation. (2016). Resiliency Guide 2.0. Retrieved from http://sdbjrfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/ResiliencyGuide.pdf

Sharpe, B. (2016, January 26). How to Define Total Compensation: A Quick Guide [blog]. Retrieved from https://hrsoft.com/blog/how-to-define-total-compensation-a-quick-guide/

Sharpe, P. A., Greaney, M. L., Lee, P. R., & Royce, S. W. (2000). Assets-oriented community assessment. Public Health Reports, 115(2-3), 205-211. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10968755

Smith, W. J., Howard, J. T., & Harrington, K. V. (2005). Essential formal mentor characteristics and functions in governmental and non-governmental organizations from the program administrator’s and the mentor’s perspective. Personnel Administration, 34(1), 31-58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/009102600503400103

Schuh, R. G., & Leviton, L. C. (2006). A framework to assess the development and capacity of non-profit agencies. Evaluation and Program Planning, 29(2), 171-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2005.12.001

Taylor-Ritzer, T., Suarez-Balcazar, Y., Garcia-Iriarte, E., Henry, D. B., & Balcazar, F. E. (2013). Understanding and measuring evaluation capacity: A model and instrument validation study. American Journal of Evaluation, 34(2), 190-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1098214012471421

TCC Group. (n.d.). CCAT Tool. Retrieved from http://www.tccccat.com/

What Is a Data Collection System (DCS)? (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.techopedia.com/definition/11311/data-collection-system-dcs

W.K. Kellogg Foundation (2004). Logic model development guide: Using logic models to bring together planning, evaluation, & action. Battle Creek, MI: Author. Retrieved from https://www.wkkf.org/resource-directory/resource/2006/02/wk-kellogg-foundation-logic-model-development-guide

1 A strategic plan is a documented framework that communicates an organization’s goals, sets priorities, and focuses energy around actions that accomplish those goals (“The Basics of Strategic Planning,” n.d.).

2 Strategic goals are the realistic and clearly-defined outcomes that guide implementation of a program or intervention (The NCJA Center for Justice Planning, n.d.).

3 Strategic objectives are concrete explanations of how goals will be accomplished, and necessary steps to reach that end (The NCJA Center for Justice Planning, n.d.).

4 Total compensation is a holistic model of employee payment that incorporates both monetary compensation (such as base pay, performance-based pay, and bonuses) and non-monetary compensation (such as health care, trainings, and benefits) (B. Sharpe, 2016).

5 A communications strategy is a document that establishes the objectives, audiences, messages, resources, responsibilities and measures for an organization’s outreach. The objectives in a communication strategy should be segmented by target audience (Hovland, 2005).

6 Policy and procedure documents define how an organization operates and provide guidance on program-specific practice (NCVO Knowhow Nonprofit, 2016).

7 Fidelity is the “extent to which delivery of an intervention adheres to the protocol or program model originally developed.” Providing consistent services is important to evaluate impact and make adjustments (Mowbray, Holter, Teague, & Bybee, 2003).

8 Program adaptations are data-driven changes to implementation that ensure sustainability and effectiveness (Program Sustainability Assessment Tool, n.d.).

9 A logic model is a visual and written depiction of the necessary inputs and activities to bring about desired outputs and outcomes (W.K. Kellogg Foundation, 2004).

10 A key performance indicator is a quantifiable performance measurement that indicates the effectiveness of a program or organization in achieving its goals (Jackson, 2015).

11 Data collection protocol is the systematic procedure by which individuals and organizations collect, maintain, secure, and use data. Protocols ensure that evaluations are effective and valid (Faculty Development, 2005.).

12 Data collection systems, typically using computer-based software, aggregate and analyze sets of data in an efficient manner (“What Is a Data Collection System?”, n.d.).

13 An evaluation instrument is a questionnaire or survey that assesses knowledge gain or behavior change in a group of program participants (Rutgers University, n.d.).

14 For participant impact to be attributed to the program interventions, there must be a causal relationship between the two, effectively ruling out other variables as the primary cause (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013).

15 A quasi-experimental study compares outcomes for individuals receiving an intervention with outcomes for comparable individuals not receiving that intervention (Moore, 2008).

16 A randomized control trial randomly assigns individual participants to either a control or treatment group in order to measure the impact of an intervention on specific outcomes (Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, n.d.).

17 Key stakeholders are individuals or organizations that share an interest in your program’s success. Stakeholders can be funders, partners, community members, participants, board members, or volunteers (The Denver Foundation, n.d.).

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Hoffberger, Trevor |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-22 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy