HospiceDevelop_For_OMB_Appdx_A_

HospiceDevelop_For_OMB_Appdx_A_10-24-14.docx

National Implementation of the Hospice Experience of Care Survey (CAHPs Hospice Survey)

HospiceDevelop_For_OMB_Appdx_A_

OMB: 0938-1257

Final Report

Appendix A

Hospice Experience of Care Survey Development and Field Test

Rebecca Anhang Price, Denise D. Quigley, Melissa Bradley, Joan Teno, Layla Parast, Marc N. Elliott, Ann Haas, Brian Stucky, Brianne Mingura, Karl Lorenz

RAND Health

PR-1222-DHHS

June 2014

Prepared for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Preface

In September 2012, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) entered into a contract with RAND to design and field test a future Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) survey to measure the experiences of patients and their caregivers with hospice care. The survey was developed to provide a source of information from which selected measures could be publicly reported to beneficiaries and their family members as a decision aid for selection of a hospice program; aid hospices with their internal quality improvement efforts and external benchmarking with other facilities; and provide CMS with information for monitoring the care provided. CMS intends to implement the survey nationally in 2015. Eligible hospices will be required to administer the survey for a dry run for at least one month in the first quarter of 2015. Beginning in the second quarter of 2015, hospices will be required to participate on a monthly basis in order to receive the full Annual Payment Update.

This work was sponsored by CMS under contract number HHSM-500-2012-00126G, for which Lori Teichman serves as project officer. The research was conducted in RAND Health, a division of the RAND Corporation. A profile of RAND Health, abstracts of its publications, and ordering information can be found at www.rand.org/health.

Table of Contents

Preface ii

Figures v

Tables vi

Executive Summary viii

Survey Instrument Development viii

Call for Topic Areas ix

Literature Review and Environmental Scan ix

Technical Expert Panel x

Cognitive Interviews x

Field Test Design and Procedures xi

Eligibility Criteria xi

Sampling Hospices xi

Sampling Deaths within Hospices xii

Survey Administration Procedures xiii

Survey Instruments xiii

Field Test Results xiii

Characteristics of Field Test Hospices, Decedents and Caregiver Respondents xiii

Response Rates xiv

Item Nonresponse and Ceiling Effects xvi

Psychometric Analyses / Development of Composites xvii

Case Mix Adjustment xix

Association between Hospice, Decedent and Caregiver Characteristics and HECS Outcomes xxi

Open-Ended Responses xxii

Final Survey Instrument xxii

Recommendations for National Implementation xxiii

Survey eligibility criteria xxiii

Timing of Survey Administration xxiv

Sampling Procedures and Methods of Sampling xxiv

Mode of Survey Administration xxv

Data Requirements xxv

Abbreviations xxvii

Chapter One. Introduction 1

Chapter Two. Survey Instrument Development 3

Call for Topic Areas 4

Literature Review and Environmental Scan 5

Technical Expert Panel 7

Cognitive Testing 8

General Findings 9

General Findings: Spanish Only 10

Chapter Three. Field Test Design and Results 12

Field Test Procedures 12

Eligibility Criteria 12

Sampling Hospices 12

Hospice Recruitment 15

Sampling Deaths Within Hospices 15

Survey Administration Protocol 16

Timing of Administration 17

Survey Instruments 17

Characteristics of Field Test Hospices, Decedents and Caregiver Respondents 17

Response Rates 21

Predictors of Unit Response 22

Analysis of Unit Response 23

Analysis of Response Mode 23

Item Nonresponse and Ceiling Effects 39

Floor and Ceiling Effects 51

Psychometric Analyses and Development of Composites 63

Item and scale-level correlations 65

Setting-specific composites 66

Case Mix Adjustment 70

Association between Hospice, Decedent and Caregiver Characteristics and Hospice Experience of Care Survey Outcomes 94

Open-Ended Responses 100

Chapter Four: Final Survey Instrument 104

Chapter Five: Recommendations for National Implementation 105

Survey eligibility criteria 105

Timing of Survey Administration 105

Sampling Procedures and Methods of Sampling 106

Mode of Survey Administration 106

Data Requirements 107

Appendix A: Members of the Technical Expert Panel 108

Appendix B: Hospice Experience Survey – Home Version 109

Appendix C: Hospice Experience Survey – Nursing Home Version 127

Appendix D: Hospice Experience Survey – Inpatient Version 143

Appendix E: Item Response Rates Among Unit Respondents 160

Appendix F: Summary of Changes to Field Test Survey 166

References 176

Figures

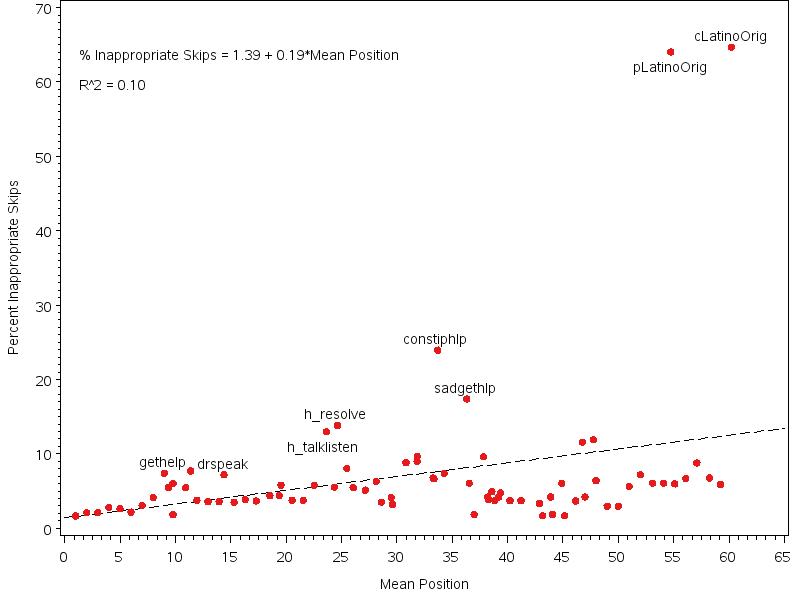

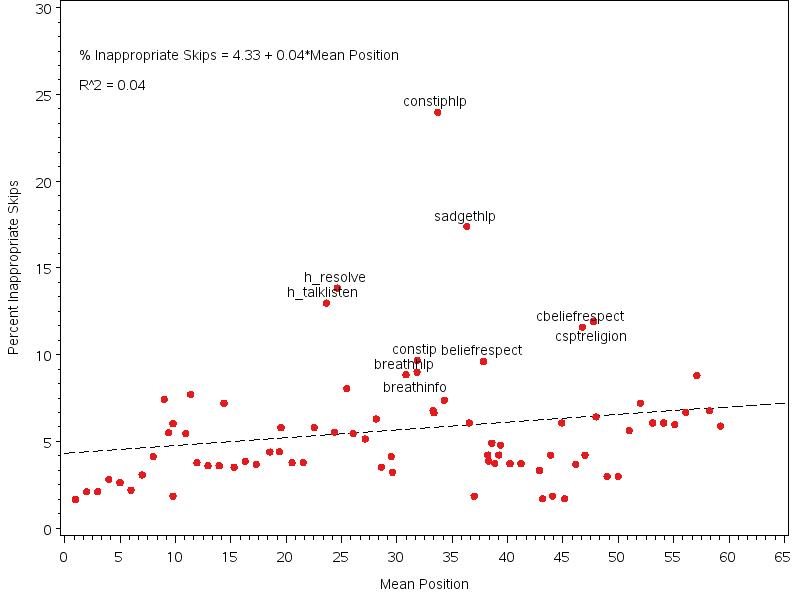

Figure 3.1. Plot of Percentage Inappropriate Skips by Item Mean Position, all items 50

Figure 3.2. Plot of Percentage Inappropriate Skips by Item Mean Position, omitting Latino origin items 52

Tables

Table 2.1. Cognitive-Interview Location, Patient Care Setting, and Income 9

Table 3.1. Targets for Hospices in Each of Three Sampling Strata 13

Table 3.2. Targeted Sample Sizes, by Hospice Care Setting and Size 14

Table 3.3. Characteristics of hospices participating in the HECS field test and nationwide using hospices “currently active” in 2012 Provider of Service file 18

Table 3.4. Characteristics of Decedents Whose Caregivers Completed the Field Test Survey and Medicare Hospice Decedents Ages 65 and Older 19

Table 3.5. Characteristics of Field Test Respondents and Respondents in the 2013 Family Evaluation of Hospice Care survey repository 21

Table 3.6. Response Rates by Setting and Survey Versiona 25

Table 3.7. Composition of Eligible Sample and Response Rates, by Hospice Characteristic 27

Table 3.8. Composition of Eligible Sample and Response Rates, by Caregiver Characteristic 29

Table 3.9. Composition of Eligible Sample and Response Rates, by Decedent Characteristic 29

Table 3.10. Mixed Linear Regression Model of Unit Response 32

Table 3.11. Unit Response Rates, by Final Setting of Care (%) 34

Table 3.12. Comparison of Eligibles, Respondents by Mail, and All Respondents, by Caregiver Characteristic 35

Table 3.13. Comparison of Eligibles, Respondents by Mail, and All Respondents, by Decedent Characteristic 36

Table 3.14. Item Nonresponse Rates by Mode and by Final Setting of Care 43

Table 3.15. Probability of item nonresponse: Logistic regression of non-legitimate missingness among all unit respondersa 45

Table 3.16. Inappropriate Skips and Item Nonresponse Rates 49

Table 3.17. Ceiling Effects: Percentage of respondents in the lowest and highest possible category and ICC 52

Table 3.18. Survey items comprising multi- and single-item composites and item-total correlations 67

Table 3.19. Correlations among composites and single-item indicators. 69

Table 3.20. Potential Case-Mix Adjustors 72

Table 3.21. Hospice-Level Intraclass Correlation Coefficients of Potential Case-Mix Adjustors to Be Included in the Models 74

Table 3.22. Summary of Models and Impact Analysis for Potential CMA and Overall Rating 77

Table 3.23. Summary of Models and Impact Analysis for Potential CMA and Willingness to Recommend 78

Table 3.24. Summary of Models and Impact Analysis for Potential CMA and the Hospice Team Communication Scale 80

Table 3.25. Summary of Models and Impact Analysis for Potential CMA and the Treating your Family Member with Respect Scale 82

Table 3.26. Summary of Models and Impact Analysis for Potential CMA and the Providing Emotional Support Scale 84

Table 3.27. Summary of Models and Impact Analysis for Potential CMA and the Getting Help for Symptoms Scale 86

Table 3.28. Parameterization of Ordinal CMA: p-values of test of hull hypothesis that categorical variables does not improve prediction beyond inclusion of the linear form. 91

Table 3.29. Overall Unadjusted Mean Scores for Overall Rating, Willingness to Recommend, and Composites 96

Table 3.30. Adjusted mean response for overall rating of hospice by hospice characteristics 97

Table 3.31. Adjusted mean response for overall rating of hospice by patient and respondent characteristics 98

Table 3.32. Adjusted Mean Response for Each Developed Composite, Overall Rating, and Willingness to Recommend, by Final Setting of Care 100

Table 3.33. Themes Identified in Open Ended Responses 101

Table E.1. Item Response Rates Among Unit Respondents 160

Table F.1. Summary of Changes to Field Test Survey 166

Executive Summary

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has implemented experience of care surveys in a number of settings including traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage and Part D Prescription Drug Plans, hospitals, and home health agencies. While CMS and/or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) have developed additional Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) surveys for in-center hemodialysis facilities, nursing homes and clinician and group practices, none of these surveys address experiences with hospice care.

In September 2012, CMS entered into a contract with RAND to design and field test a future CAHPS survey to measure the experiences of patients and their caregivers with hospice care. The survey was developed to (1) provide a source of information from which selected measures could be publicly reported to beneficiaries and their family members as a decision aid for selection of a hospice program; (2) aid hospices with their internal quality improvement efforts and external benchmarking with other facilities; and (3) provide CMS with information for monitoring the care provided. National implementation of the survey will begin in 2015. Eligible hospices will be required to administer the survey for a dry run for at least one month in the first quarter of 2015. Beginning in the second quarter of 2015, hospices will be required to participate on a monthly basis in order to receive the full Annual Payment Update.

In this report, we briefly summarize the work that RAND conducted to develop and field test the new survey, referred to throughout the report as the Hospice Experience of Care Survey (HECS). We provide an overview of the survey development process; describe the field test design and procedures; present analytic methods and findings from the field test; present the final survey instrument for national implementation; and make recommendations for national implementation.

Survey Instrument Development

Content and design of the HECS were informed by the following inputs:

a Call for Topic Areas in the Federal Register;

a review of the literature and environmental scan of existing tools for measuring end-of-life care;

input and feedback from survey and hospice care quality experts at a technical expert panel (TEP); and

cognitive testing with primary caregivers of hospice patients.

Call for Topic Areas

In response to a Call for Topic Areas published in the Federal Register in January 2013, stakeholder groups provided suggestions for survey content, including the following:

perceptions of the adequacy and frequency of provider visits;

measures of physical, psychosocial and economic distress of patients receiving hospice care in the nursing home;

level of support by the nursing home in obtaining a hospice referral;

adequacy and redundancy of services by the hospice care team and the residential facility;

information about experiences with medication changes;

regular use of comprehensive symptom management instruments in the hospice setting;

speed and degree of symptom management as well as flexibility in meeting patient needs;

availability of information to support informed decision making by patients and their caregivers;

degree to which hospice providers discussed, understood, respected and met patient and care giver preferences regarding the extent and intensity of life-prolonging care; and

specific items to address patient provider communication, care coordination, shared decision making, symptom management including pain and anxiety, access to care, understanding hospice, respect and dignity, care planning process, confidence of caregiver to perform care tasks, emotional and spiritual support, caregiver circumstances, and recommendation of the hospice to others.

Literature Review and Environmental Scan

A systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature on experiences with end-of-life care identified 87 articles containing 50 unique survey tools. The most common categories of survey content were as follows:

information / care planning / communication (Number of survey questions=632)

symptoms (303)

provider care (223)

spiritual / religious / existential (187)

overall assessment (134)

psychosocial care (131)

personal care (80)

veteran care (72)

responsiveness / timing (71)

caregiver support (59)

quality of death / last days (51)

bereavement care (33)

environment (28)

patient-centered care (20)

financial (14)

Technical Expert Panel

In December 2012, we convened a Technical Expert Panel (TEP), including experts on hospice care quality, survey research and performance measurement and improvement as well as individuals representing organizations that could have a major influence on the adoption of a standardized hospice care survey and promotion of its use in public reporting and quality improvement. TEP members agreed with the main survey content domains proposed: Access to care / responsiveness; Communication; Shared decision making; Care coordination; Symptom management / palliation; Information / skills for caregivers; Emotional / spiritual support; Environment; Overall rating of care.

TEP members agreed that the field test should exclude from sampling those cases in which the hospice patient died within 48 hours of admission, there was no caregiver listed in hospice records, or the primary caregiver in hospice records is a non-familial/friend (i.e., legal) guardian. TEP members recommended that the survey be administered no sooner than 1 month after death, and no later than 6 months after death, but noted that the logistics of sampling (i.e., receipt of data from hospices, data processing and mailing) would likely preclude sampling before 6 weeks after death.

Cognitive Interviews

Based on input from the Call for Topic Areas, literature review, qualitative interviews, and TEP, we drafted and refined three setting-specific survey instruments for cognitive testing, one for the home setting, one for the nursing home setting, and one for the inpatient setting, including both freestanding hospice inpatient units (IPUs) and acute care hospitals.

The team conducted three rounds of cognitive interviews to test interpretation and comprehension of survey content, revising survey instruments and protocols revised between each round of interviews. Interviews resulted in refinements to the carrier phrase (“while your family member was in hospice care”); re-organization of the survey to separate items inquiring about the respondents own experience with hospice from items inquiring about the patient’s experience; and removal of an item regarding pain treatment decisions in favor of an item regarding side effects of pain medicine.

Field Test Design and Procedures

From November 12 through December 23, 2013, we conducted a field test of the three setting-specific versions of the HECS. The survey was administered between 2 and 5 months following the death of the hospice patient, corresponding to deaths that had occurred between July 26, 2013 and September 11, 2013.

The field test was designed to assess survey administration procedures and to develop composite measures of hospice performance, while enabling comparisons of response rates and response patterns for larger and smaller hospices, and for the four settings of hospice care:

home, which includes home and assisted living facilities

nursing home, which includes skilled and regular nursing facilities

two sub-settings of inpatient care

acute care hospitals

free-standing hospice IPUs.

Eligibility Criteria

The following groups of hospice patients and the primary caregivers noted in their hospice’s administrative records were eligible for inclusion in the sampling universe:

Patients over the age of 18

Patients with death at least 48 hours following admission to their final setting of hospice care

Patients for whom a caregiver is listed or available and for whom caregiver contact information is known

Patients whose primary caregiver are people other than nonfamilial legal guardians

Patients for whom primary caregivers have U.S. or U.S. Territory home addresses.

Patients or caregivers of patients who requested that they not be contacted (those who sign no publicity requests while under the care of hospice or otherwise directly request not to be contacted) were excluded. Identification of patients and caregivers for exclusion was based on hospice administrative data.

Sampling Hospices

We used 2012 CMS Provider of Service and hospice claims files to characterize a sample frame of all hospices in the United States. We excluded hospices that were not eligible for, or had terminated, their participation in Medicare, those that had closed or had no claims for care services, and those that cared for fewer than 10 decedents per month, as these smaller hospices did not have enough volume to produce a sufficient sample size during the field test. We aimed to sample 30 hospice programs, 20 midsize-to-large (“larger”) hospice organizations (targeting completed surveys for 30 decedents per larger organization) and 10 smaller hospice organizations (targeting completed surveys for 10 patients per smaller organization). To increase the number of Spanish-speaking respondents, we sought to include at least one Puerto Rican hospice and one high-Hispanic mainland hospice.

In addition, we aimed to include a targeted number of hospices with the following characteristics in the final participating field test sample: a natural mix of hospices across 4 geographic regions in the U.S.; at least 1 hospice belonging to a national chain; 10 to 15 for-profit hospices; 1 government hospice; and at least 3 rural hospices, so as to establish feasibility of survey implementation and identify potential challenges (e.g., variation in response rates or rates of missingness) related to hospice characteristics.

To satisfy these targets, we randomly selected hospices proportionately with respect to region, and disproportionately with respect to hospice size, chain status, profit status, government ownership, and rural location. Because the design was not fully factorial, a simulation-based sampling approach was employed to derive a sample draw that was within a small pre-specified tolerance. Our sample target was 2,430 across hospice care settings and hospice size. We assumed 25 percent of deaths would be deemed ineligible, and a 40 percent response rate from caregivers.

Sampling Deaths within Hospices

Representatives from each hospice that agreed to participate in the field test submitted data files to support survey administration and analyses, including data on characteristics and care patterns of decedents, and contact information for primary caregivers. For each hospice, we identified and removed cases that were ineligible to participate.

To ensure a sufficient number of responses to compare experiences across settings of hospice care, we selected all eligible cases in the less common settings of care: nursing home, acute care hospital, and hospice inpatient unit. We subsampled cases in the largest setting, home care, with a higher sampling rate of 50% in hospices with higher proportions of black or Hispanic decedents (defined as 10% or more in either category). Across all hospices, we sampled 729 cases in the home setting, 639 in nursing homes, 198 in acute care hospitals, and 701 in hospice inpatient units, for a total of 2,267 cases.

Survey Administration Procedures

We used a mixed mode survey administration protocol, including one survey mailing, one prompt letter, and telephone as the secondary or nonresponse mode. In keeping with HCAHPS guidelines, the entirety of the field period from initial survey mailing to cessation of calling was no longer than 42 days (six weeks).

Survey Instruments

There were three setting-specific versions of the survey instrument, corresponding to the final setting in which the decedent received hospice care: home (including assisted living facility), nursing home, and inpatient (including acute care hospital and hospice inpatient unit).

Several survey sections were identical across the three versions: The Hospice Patient (3 items); Your Role (2 items); Starting Hospice Care (2 items); Your Own Experience with Hospice (7 items); Overall Rating of Care (3 items); About Your Family Member (4 items); and About You (7 items). The section on Your Family Member’s Hospice Care had 41 items on the home version, 37 items on the nursing home version, and 36 items on the inpatient version; 33 of these items were the same across all three versions. The home version had an additional section on Special Medical Equipment (3 items) and the inpatient version had an additional section on The Hospice Environment (3 items). The home version had a total of 72 items, the nursing home version had 65 items, and the inpatient version had 67 items; 61 items were the same across all versions.

Field Test Results

Characteristics of Field Test Hospices, Decedents and Caregiver Respondents

Thirty-three hospice programs from 29 hospice organizations agreed to participate in the field test. In keeping with our aim to include hospices with a range of size, ownership, geographic region, urbanicity, and chain status, 75.6% of hospices participating in the field test were small (10 to 29 deaths per month in the non-flu months of April through October), 39.4% were non-profit, 12.1% were located in rural areas, and 15.2% were members of national chains (Table 5). Compared to hospices nationwide, hospices participating in the field test were significantly more likely to be not-for profit (p=0.03) and had lower rates of live discharge (p=0.07). Hospices with fewer than 10 deaths per month in non-flu months were not eligible to participate in the field test, and therefore are not represented in the field test sample; such small hospices represent more than half (56.5%) of all hospices nationwide.

In all, 1,136 respondents completed the field test survey, reporting care experiences for 1,136 hospice decedents. The mean age of decedents was 79.8; 5.6% were black, and 4.3% were Hispanic. For more than one-third (34.7%) of decedents, the last setting of hospice care was a home or assisted living facility; last location was a nursing home for 27.9% of decedents, a hospice freestanding IPU for 29.7%, and an acute care hospital for 7.8%. The age, sex and race distributions of field test decedents were generally similar to the population of Medicare beneficiaries receiving hospice care. Hospice patients who died after less than 48 hours on hospice service were excluded from the field test; hence, the field test sample underrepresents those with short lengths of stay when compared to the national data.

Nearly three-quarters (72.6%) of respondents were female, 44.8% were age 65 or older, and 5.8% were black. Nearly half (46.6%) were children of the hospice patient, while one-third were the spouse or partner.

Response Rates

Unit nonresponse occurs when an eligible sampled individual does not respond to any of the items in a survey. We describe rates of unit nonresponse/response and assess hospice-, caregiver- and decedent-level characteristics associated with unit nonresponse.

The overall response rate among eligible members of the sample was 53.6%. The response rate in the home setting was slightly higher (56.5%) than in the other three care settings (51.3-52.9%). Multivariate regression analyses showed that the relationship between the survey caregiver and the decedent, previous receipt of the FEHC survey, decedent age at death, decedent race/ethnicity and length of final episode of hospice care are all significantly associated with the probability of response. In particular, spouses and parents were more likely to respond than children, those who were mailed the FEHC survey were less likely to respond, caregivers of older decedents were more likely to respond than those of younger decedents, and caregivers of Hispanic decedents were less likely to respond compared to other race/ethnicity categories. In addition, caregivers of decedents who had a longer length of final episode of hospice care were more likely to respond than those with a shorter length. Given the anticipated suspension of the FEHC during national implementation of the HECS, we may expect improved response rates in national implementation. Specifically, FEHC mailing was associated with an 8.8% lower response rate compared with those who were not mailed the FEHC in this field test and about 90% of eligible caregivers were mailed the FEHC; given our observed overall response rate of 53.6%, in the absence of the FEHC we would expect a response rate of about 61.4% given the same administration procedures and field period.

Non-responding cases include refusals, the majority of which were identified during telephone data collection and directly from the sampled caregiver rather than an informant on the caregiver’s behalf. Approximately 19% of caregivers who refused did not provide a specific reason for refusal, either simply hanging up or indicating they were not interested. Telephone interviewers could code more than one reason for refusal. Where reasons were provided, the most frequently cited were that the caregiver was too busy (cited by 34.4% of refusals) and/or not emotionally ready to discuss the patient’s care (cited by 31.3% of refusals). Some caregivers indicated that they had previously provided information, perhaps thinking about the FEHC, and would not do so again (cited by 14.4% of refusals). It seems likely that at least a portion of these refusals would have completed if they had not previously received the FEHC. A smaller proportion of refusing caregivers (11.3%) declined to participate citing that they did not know enough about the patient’s care; just over half of this group noted that the time the decedent spent in care was too short to properly comment. This follows along with the finding that caregivers of decedents with shorter lengths of stay were less likely to respond.

Caregivers with a longer time between decedent death and the beginning of mailing of the HECS, caregivers of younger decedents and caregivers of black and Asian/Pacific Islander decedents were less likely to respond by mail compared to phone. Given that a longer time between the decedent’s date of death and the date of first mailing tended to result in a lower probability of response by mail and thus a higher probability of response by phone and that mail mode is generally less costly than phone mode, this might suggest a recommendation that mailings go out more quickly than what we implemented in this field test. For example, these results suggests that delays between death and mailing that were in the highest quartile, a delay of 98 days or more, should be avoided in national implementation.

In addition, one-fifth of eligible non-responding cases were un-locatable during the field test. As caregivers may move or change contact information after patient death, this further underscores the need for fielding the survey in a timely manner after patient death. The number of un-locatable cases also highlights the need for hospices to give attention to verification of caregiver contact information, and to consider collecting and maintaining multiple sources of contact information for caregivers.

These response analyses also show that while caregivers of black and Hispanic decedents are less likely to respond to the survey in general compared to caregivers of white decedents, caregivers of black and Asian decedents that do respond are more likely to respond by phone rather than mail. With such small minority representation in the field test and likely across hospices in general, this highlights the importance of telephone follow-up to ensure that such groups are represented. Use of the telephone mode in addition to the mail mode yielded a group of respondents that were more similar to the eligible sample in terms of race/ethnicity of the decedent and in terms of other characteristics including relationship to decedent, age of decedent, and payer for hospice care, although differences still persist between all respondents and the eligible sampled group.

Item Nonresponse and Ceiling Effects

Item nonresponse occurs when a unit respondent inappropriately skips an item. We describe rates of item nonresponse and assess hospice-, caregiver-, and decedent-level characteristics associated with item nonresponse. In addition, we investigate floor and ceiling effects by examining both the number of respondents validating extreme response categories expressed as a proportion of valid responses obtained and the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). ICCs measure the amount of variability in response among hospices. Low ICCs indicate highly similar mean scores across hospices relative to variability within hospices and may indicate that an item was poorly understood and require modifications. However, a low ICC in combination with a very high or very low mean score may indicate a ceiling or floor effect (i.e. where most hospices score near the maximum or minimum limiting the ability of that question to distinguish performance between hospices).

Item nonresponse analyses showed that overall item missingness among eligible items was 5.5% with a lower item missingness rate observed in the home care setting even though the survey instrument for this setting is longer (62.9 eligible items compared to 56.0-58.4 for the other care settings). Higher non-response in the non-home care settings was not restricted to setting-specific items asked only in the nursing home and inpatient survey instruments. This pattern may be due to caregivers of decedents in the home care setting being more familiar with their family member’s care than caregivers of patients in other settings. Item missingness tended to be higher with an increased number of applicable items and for those items that appeared later in the survey instrument. While there was a slightly higher item non-response rate among respondents by phone compared to mail, it is common in CAHPS settings to see much higher item nonresponse by phone due to break-off (i.e., respondent hanging up before call is completed) than what was observed in this field test. This may indicate that break-off is less likely in the hospice survey due to the emotional content of the survey. Among unit respondents, several characteristics were associated with higher item missingness, including caregivers who were spouse/partners and non-family members (i.e., friends) of the decedent, caregivers of decedents covered by Medicaid or Medicaid/private insurance, caregivers of decedents in nursing home and inpatient care settings, and caregivers of decedents with a primary diagnosis of dementia/neurological disease or cardiovascular disease. Among unit respondents, several characteristics were associated with lower item missingness including caregivers of younger decedents, caregivers of Asian/Pacific Islander decedents, caregivers of decedents with longer final episodes of hospice care and caregivers who reported they ‘usually’ or ‘always’ took part in care of the decedent. This observed pattern in item nonresponse by caregiver relationship and decedent age may be largely driven by the fact that these caregivers may be older themselves and older age is often associated with higher item nonresponse in CAHPS. In addition, the observed lower rates of inappropriate missingness were observed among caregivers who reported ‘usually’ or ‘always’ taking part in care for family member compared with those who ‘sometimes’ took part in care is not surprising, as these respondents likely know more about the care that was received.

The analysis of floor and ceiling effects showed that 12 items had a high proportion of responses in the highest category and 11 of these 12 also had very small ICC estimates indicating a ceiling effect for these 11 items. For these 11 items, the ability to distinguish performance between hospices based on responses to these items is very limited. Given the anticipated larger number of respondents per hospice and larger number of hospices in national implementation, ICC estimates may be better estimated in national implementation.

Psychometric Analyses / Development of Composites

Composites are collections of items on the survey that assess similar content domains. When a set of items measure a given content domain, combining those items into a composite allows for a more precise estimate of a respondent’s experience of care than would be possible from any single item and allows fewer measures to be presented to consumers, reducing cognitive burden. We constructed factor analytic models to establish domains of interest (i.e., composites), and calculated item- and scale-level correlations to ensure the domains measure distinct content.

The analytic process resulted in the development of multi-item composites and single-item measures of key HECS domains, as follows. (Alpha is shown for multi-item composites, and refers to Cronbach’s alpha, a 0 to 1 index that increases with the number of items in a domain and their average correlation with one another. Higher values indicate better measurement of the underlying construct that the composite is intended to measure.) Survey items in each of the multi-item composites and single-item measures are:

Hospice team communication (alpha = .89) |

|

|

|

|

|

Getting timely care (alpha =.72) |

|

|

Treating your family member with respect (alpha =.69) |

|

|

Providing emotional support (alpha = .68) |

|

Providing Support for Religious and Spiritual Beliefs

|

Getting help for symptoms (alpha = .80) |

|

|

|

|

Information continuity |

|

Understanding the side effects of pain medication

|

|

Getting hospice care training (Home setting only; alpha = .87) |

|

|

|

|

The scales are generally moderately intercorrelated. There is a slight tendency for the inter-correlations between composites and measures to be highest for the Hospice team communication (r = .38 to .66). This is due in part to the survey generally assessing the communication between the hospice team and the family, but is also reflective of the high internal consistency of this composite. The inter-correlations are somewhat lower for the Information continuity (r = .23 to .38) and Providing emotional support (r = .16 to .53) composites, indicating that these domains measure content that is distinct on the survey.

Case Mix Adjustment

Previous research, both within and outside of CAHPS, has identified respondent characteristics that are not under the control of the entities being assessed but tend to be related to survey responses. For example, individuals who are older, those with less education and those in better overall and mental health generally tend to give more positive ratings and reports of care in Medicare CAHPS. Hence entities with disproportionate numbers of patients with such characteristics (favorable case mix) are advantaged relative to those with less favorable case mix. To ensure that comparisons between hospices reflect differences in performance rather than differences in case mix, responses must be adjusted for such characteristics.

We make recommendations for case-mix adjustment (CMA) of hospices participating in the field test, examine adjusted scores, and describe the impact of adjustment. Note that these are preliminary recommendations based solely on the field test and may be further informed by information obtained from national implementation. In general, only respondent characteristics that are determined not to be endogenous (i.e., not to be related to satisfaction or quality of care) should be considered as potential case-mix adjustors. Given this particular setting and available information, we considered both respondent and decedent characteristics as potential case-mix adjustors. Outcomes examined were: overall rating of hospice care, willingness to recommend the hospice, and the multi-item composites Hospice team communication, Treating your family member with respect, Providing emotional support, and Getting help for symptoms.

Overall, little-to-moderate variation in the following respondent and decedent characteristics was observed among hospices in the field test: language of completed survey, payer type, language spoken at home, prior receipt of the FEHC, decedent age, decedent education, primary diagnosis of dementia/neurological vs. other, and respondent education. A small number of characteristics were significantly associated with at least one of six outcomes examined in either a univariate or multivariate model: respondent sex, primary diagnosis of dementia/neurological vs. other, payer type, language spoken at home, primary diagnosis of cardiovascular disease vs. other, and language of completed survey. Only prior receipt of the FEHC demonstrated substantial marginal impact on adjustment of hospice-level scores.

Though decedent age, decedent sex, decedent education, respondent age, and respondent education neither were significantly associated with any examined outcomes nor had moderate or large (standardized regression coefficient greater than 0.20 SD) nonsignificant effects, one might consider retaining them in the survey for case-mix adjustment or other purposes. First, other CAHPS surveys including MCAHPS and CAHPS for Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) observe substantial variation in respondent age and respondent education among entities being evaluated and significant associations with ratings and reports of care and thus adjust for such respondent characteristics. Our potentially limited power in the field test to observe such effects leads us to recommend retaining these items in the survey for further evaluation in national implementation. Second, while improved power in national implementation will also allow further evaluation of decedent age, sex and education as case-mix adjustors, one would also be interested in retaining these items in the survey regardless of adjustment potential to allow for description and reporting of observed true differences in quality of care by these characteristics at a national level. Similarly, this reasoning also supports the retention of survey items related to decedent race/ethnicity. While this decedent characteristic was ruled out for case-mix adjustment consideration, it should be retained in the survey so that potential disparities in quality of care can be examined moving forward. Respondent race/ethnicity, on the other hand, was not considered for adjustment and would likely not be needed for future analyses. Furthermore, among respondents who answered survey items relating to the respondent’s race/ethnicity and the decedent’s race/ethnicity, race/ethnicity matched in 94.8% of cases.

Payer type demonstrated substantial variation among hospices and was significantly associated with multiple outcomes. Therefore, we recommend including this variable in the final CMA model. Note that this is similar to the inclusion of Medicaid dual eligibility in the CMA models for MCAHPS and CAHPS for ACOs.

While the characteristic indicating whether a respondent was located in the same state as the hospice was included in our initial list of candidate adjustors and examined in these analyses, further discussion of this variable, along with potential inclusion of a variable indicating whether the respondent was located in the same city as the hospice, has led us to recommend that both variables be excluded from CMA consideration due to the fact that they seem to be proxies for census region. In general, stakeholders do not tend to support adjustment for region in CAHPS and to maintain consistency with other CAHPS survey initiatives we recommend not including variables that directly or indirectly measure region. Finally, while respondent’s relationship to the decedent was not significantly associated with any examined outcomes and varied very little among hospices, we recommend including this characteristic provisionally in the CMA model for the field test and recommend further examination in national implementation.

For the purposes of providing hospice level scores for hospices participating in the field test, we recommend a CMA model that includes the following:

language of completed survey

decedent age

decedent education

decedent sex

payer type (all categories)

primary diagnosis (all categories)

respondent age

respondent education

respondent sex

language spoken at home (all categories)

relationship to decedent (all categories)

prior receipt of FEHC Survey

This recommended case-mix adjustment model should be further examined and evaluated in national implementation. Prior receipt of the FEHC is unlikely to be relevant in the context of national implementation. Future considerations could include discussion about whether one should categorize primary diagnosis as dementia/neurological vs. cardiovascular disease vs. other, categorize payer type as Medicare only vs. Medicare and Medicaid vs. Medicaid only/Medicaid and private, categorize language spoken at home as English only vs. other and categorize relationship to decedent as spouse/partner vs. other.

Association between Hospice, Decedent and Caregiver Characteristics and HECS Outcomes

We explore a range of hospice, patient, and caregiver characteristics that may be associated with differences in care experiences, particularly geographic region, hospice size, chain status and profit status at the hospice level, and setting of care at the decedent level.

Overall, across hospice, decedent and caregiver characteristics, the mean overall rating of hospice care was 93.0 out of 100. Mean scores for each composite were generally high, ranging from 81.0 for Understanding the side of effects of pain medication and 85.2 for Getting hospice care training to 94.9 for Information continuity and 95.7 for Treating your family member with respect.

Adjusted means varied greatly by hospice region with lower adjusted means for overall rating and willingness to recommend for hospices in the Northeast and Puerto Rico. Regional results should be interpreted with caution given that field test hospices may not be representative of hospices within their regions, and that Puerto Rico results reflect only one hospice. Chain hospices also tended to have lower adjusted mean scores compared to non-chain hospices. Differences in adjusted mean scores by hospice size were not observed for any outcomes examined.

In keeping with prior analyses reported by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) regarding important concerns with provision of hospice care in nursing homes, we find that reported experiences of care are typically worse in the nursing home setting, particularly with regard to Understanding the side effects of pain medication, Getting help for symptoms, Getting timely care, and Hospice team communication. Such differences may be associated with different visit patterns in the nursing home setting (i.e., fewer visits from skilled nursing staff). The field test findings support that experiences of care in freestanding hospice IPUs are rated best by caregivers. There were few significant associations between patient and respondent characteristics and outcomes.

Open-Ended Responses

All versions of the field test instrument included an open-ended survey item meant to elicit detailed comments from respondents on both exemplars and problems related to the care the patient received from the hospice. One purpose of including the open-ended question was to determine if any domains not represented by the field test questions should be considered for inclusion in the final survey.

The open-ended text responses were analyzed to identify general themes. Text responses were first coded as positive or negative. Positive and negative comments were furthered coded into 14 themes; themes were identified based on the survey content and some emerged from the text itself. The most prevalent themes identified in the text included concern and respect, communication, emotional support, access, staff/team care, medication, knowledge imparted to caregiver, and religious support. The open-ended questions elicited rich and detailed responses regarding these themes, but for the most part addressed issues for which survey questions already existed.

Final Survey Instrument

We identified items to maintain for the final survey instrument using several general guidelines. First, we removed items that were included on the field test instrument solely to facilitate tests of construct validity (e.g., “Did your family member begin getting hospice care too early, at the right time, or too late?”), and those that exhibited little variation or ceiling effects. Some items with limited variation were maintained due to the importance of the measured constructs to hospice stakeholders or consumers (e.g., an item regarding spiritual/religious support). For parallel items regarding caregivers’ and decedents’ experiences (e.g., “How often did the hospice team listen carefully to you?” and …”to your family member?”), we generally included the item directed to the caregiver respondent rather than the decedent on the grounds that respondents’ answers regarding their own experiences have greater face validity than proxy answers on behalf of family members. Finally, we retained items, such as respondent and decedent race and education, that may be used for case-mix adjustment or other analytic purposes.

Because few setting-specific items were maintained for the final version of the survey instrument, and because it is simpler and less expensive to administer one survey instrument in national implementation, rather than multiple setting-specific versions, the three setting-specific survey instruments administered during the field test were consolidated into one instrument designed to measure experiences with care in all care settings in which the patient received care. Items specific to the nursing home setting are presented under the heading “Hospice Care Received in a Nursing Home,” and tailored nonapplicable responses are offered for items specific to the home setting. No inpatient-specific items were maintained for the final survey. The final survey instrument is 47 items.

Recommendations for National Implementation

Based on the experiences in the field test, and the input of a subsequent TEP convened for the National Implementation of the HECS contract, we recommend the following procedures for national implementation.

Survey eligibility criteria

The following groups of patients discharged from hospice are eligible for inclusion in the sampling universe:

decedents over the age of 18

decedents with death at least 48 hours following last admission to hospice care

decedents for whom there is a caregiver of record

decedents whose caregiver is someone other than a non-familial legal guardian; and

decedents for whom the caregiver has a U.S. or U.S. Territory home address.

Decedents or caregivers of decedents who request that they not be contacted (those who sign “no publicity” requests while under the care of hospice or otherwise directly request not to be contacted) will be excluded. Patients whose last admission to hospice resulted in a live discharge will be excluded.

These eligibility criteria closely match those of the field test with the notable exception that the required length of stay of 48 hours is not restricted to the final setting of hospice care as it was in during the field test. This recommendation follows from the decision to implement one consolidated survey, rather than setting-specific versions, in national implementation. During the field test we needed to ensure that patients had a minimum of 48 hours in the last setting of care, to ensure that caregivers had enough experience to respond to the setting-specific questions. With the one consolidated survey, all caregiver respondents, even those whose family member experienced a transition in care setting, should be able to respond to all questions. Approximately 99% of transitions in care setting occur within the same hospice organization (analysis of 2012 CMS hospice claims data); therefore, respondents reporting on care experiences across settings are highly likely to be reporting about the hospice named on the survey cover.

Timing of Survey Administration

We recommend that the 42-day data collection period begin 2 to 3 months following patient death. This will result in caregivers being surveyed between 2 and 4.5 months after their family member’s death. This recommendation is in keeping with the field test, but modified to reflect monthly data submission by hospices to vendors during national implementation. Survey administration should begin two calendar months following the completion of the data submission month (e.g., on April 1 for deaths occurring anytime between January 1 and January 31). The time lag is designed to be respectful of caregiver grief while allowing for adequate recall of hospice care experiences, and keeping to a minimum the proportion of the sample frame that will have changed contact information in the period following the death.

Sampling Procedures and Methods of Sampling

The field test did not examine alternative methods of sampling; however, given that many hospices participating in national implementation will have a small patient volume, we make the following recommendation:

Hospices with fewer than 50 decedents during the prior calendar year should be exempt from the survey data collection and reporting requirements. Hospices with 50 to 699 decedents in the prior year (n = 2,326 in 2012) should be required to survey all cases. Large hospices with 700 or more decedents in the prior year (n = 274 in 2012) should be required to survey a minimum sample of 700 using an equal-probability design. Prior to the introduction of the HECS, most hospices sponsoring the FEHC survey administered it to all cases (a census). While we do not recommend requiring census administration, this option should be available to hospices that wish to continue it.

Our sampling recommendations are derived from the assumptions, based on the HECS field test, that approximately 85% of cases will be eligible, and that approximately 50% of those in the sample frame will respond. These rates will result in an estimated 300 completed questionnaires for each large hospice and between 21 and 300 completed questionnaires for hospices with at least 50 decedents during the calendar year. Assuming a total of 300 completes within each hospice and an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.01, which measures the amount of variability between hospices, we would achieve an interunit reliability of 0.75. Note that in Medicare CAHPS (MCAHPS) a reliability of 0.75 is regarded as a minimal acceptable standard.

Mode of Survey Administration

The HECS field test did not examine the effects of survey mode on patterns or rates of response. As such, we recommend that hospices be allowed to administer the survey using one of the three mode protocols currently in use for other CMS CAHPS data collection efforts, such as HCAHPS. Specifically, the three recommended modes are: mail only (one mailed survey followed by an additional mailed survey to non-responders 21 days later); telephone only (up to five telephone attempts); and mixed mode (one mailed survey followed by telephone follow-up to non-responders 21 days later with up to five telephone attempts). During the first year of national implementation, a mode experiment will be conducted to assess the degree to which results from the three modes of survey administration are comparable, and to develop analytic adjustments to compensate for any differences across modes if needed.

Data Requirements

We recommend that hospices be required to supply monthly data files to their vendors containing the following types of data elements for hospice patients who died within a calendar month while under the care of the hospice program (first day of month through last day of month).

Information about the hospice patient

patient name (first, middle (if available), last) and prefix/suffix

date of birth

date of death

sex

race/ethnicity

primary diagnosis

admission date for final episode of hospice care

payers (primary, secondary, other)

last location / setting of care (i.e., home, assisted living facility, nursing home, acute care hospital, freestanding hospice inpatient unit)

Information about the primary caregiver

caregiver name (first, middle (if available), last) and prefix/suffix

contact information, including mailing address, telephone numbers, email address (if available)

relationship to hospice patient (i.e., spouse/partner, child, sibling, etc.)

Survey vendors should conduct all sampling activities. Hospices should be required to document the complete list of all patients/caregivers for whom information has been withheld from the survey vendor for any reason, and to provide counts of patients by each of the ineligible categories to allow for tracking. Ineligible categories are:

patient was discharged alive

decedent was over the age of 18

decedent’s death was less than 48 hours following last admission to hospice care

decedent has no caregiver of record

decedent’s caregiver is a non-familial legal guardian

decedent’s caregiver has an address outside the U.S. or U.S. Territories; and

decedent or caregiver requested not to be contacted (i.e., signed “no publicity” requests or otherwise directly requested not to be contacted).

Abbreviations

ACO |

Accountable Care Organization |

AHRQ |

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

CAHPS |

Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems |

CFA |

confirmatory factor analysis |

CI |

confidence interval |

CMA |

case-mix adjustment |

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

COR |

Contracting Officer’s Representative |

EFA |

Exploratory Factor Analysis |

FEHC |

Family Evaluation of Hospice Care |

HCAHPS |

Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Hospital Survey |

HECS |

Hospice Experience of Care Survey |

HRQOL |

Health-Related Quality of Life |

HSAG |

Health Services Advisory Group |

ICC |

intraclass correlation coefficient |

IPU |

inpatient unit |

MCAHPS |

Medicare Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Survey |

MedPAC |

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission |

SD |

standard deviation |

SES |

socioeconomic status |

TEP |

technical expert panel |

Chapter One. Introduction

The Institute of Medicine has identified patient-centeredness as a cardinal feature of health care quality, alongside safety, effectiveness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Surveys of care experience directly evaluate the degree to which care is patient-centered and therefore assess an intrinsically important dimension of care quality. Care experience measures derived from surveys complement other measures of care quality (Berenson, Pronovost, and Krumholz, 2013), facilitate providers’ efforts to improve patients’ experiences of care (Goldstein et al., 2001; Friedberg et al., 2011), and provide patients with valuable information for selecting health care providers and plans (Kolstad and Chernew, 2009).

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has implemented experience-of-care surveys in a variety of settings, including traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage, Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Plans, hospitals, and home health agencies. Although CMS and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) have developed additional Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) surveys for in-center hemodialysis facilities, nursing homes, and clinician and group practices, none of these surveys addresses experiences with hospice care.

In September 2012, CMS entered into a contract with RAND to design and field test a future CAHPS survey to measure the experiences that patients and their caregivers have had with hospice care. The survey was developed to (1) provide a source of information from which selected measures could be publicly reported to beneficiaries and their family members as a decision aid for selection of a hospice program, (2) aid hospices with their internal quality improvement efforts and external benchmarking with other facilities, and (3) provide CMS with information for monitoring the care provided. CMS intends to implement the survey nationally in 2015. Eligible hospices will be required to administer the survey for a “dry run” for at least one month in the first quarter of 2015. Beginning in the second quarter of 2015, hospices will be required to participate on a monthly basis in order to receive the full annual payment update.

This report provides a summary of the work that we have conducted to develop and field test the new survey, the Hospice Experience of Care Survey (HECS). The report is divided into three parts. Chapter Two briefly describes each of the steps of survey development, including a public request for information about publicly available measures and important topics to measure; a review of the existing literature on tools that measure experiences with end-of-life care; exploratory interviews with caregivers of hospice patients; a technical expert panel (TEP) attended by survey development and hospice care quality experts; and cognitive interviews to test draft survey content. Chapter Three describes the field test design and procedures and presents analytic methods and findings, including unit response rates; item nonresponse and ceiling effects; composite development; case-mix adjustment (CMA) modeling; variation in performance by hospice, patient, and caregiver characteristics; and key drivers of overall performance ratings. Chapter Four presents the final survey instrument for national implementation. Chapter Five describes recommendations for national implementation. We also include six appendices: Appendix A lists participants in the TEP, Appendices B through D contain the three setting-specific field test survey instruments, Appendix E presents item response rates, and Appendix F summarizes changes to the field test survey.

Chapter Two. Survey Instrument Development

Rigorous development and testing are needed to develop an experience-of-care survey that can be used for a variety of purposes, including informing consumers, monitoring performance, identifying quality improvement targets, and promoting accountability (Darby, Hays, and Kletke, 2005; Crofton, Lubalin, and Darby, 1999). Survey development must take into account prior literature regarding experiences of care in the setting under consideration, perspectives of the consumers who may use reported care experience measures for decisionmaking, and stakeholders who will administer the survey and apply its results for quality improvement and accountability. Accordingly, the following steps were pursued to develop the content and design of the HECS:

call for topic areas in the Federal Register

review of the literature and environmental scan for existing tools for measuring end-of-life care

input and feedback from survey and hospice care quality experts at a TEP

cognitive testing with primary caregivers of hospice patients.

Throughout the development process, the project team incorporated input from each of these sources in an incremental process of revision and refinement to allow for more-precise measurement and to produce survey data that would better meet the information needs of consumer and stakeholder audiences.

CMS and RAND agreed on two critical design features before undertaking survey development, verifying these choices with the TEP. First, HECS respondents are informal caregivers (i.e., family members and close friends) of hospice patients, not hospice patients themselves. Direct reports from patients usually are not feasible because of the acuity of illness and speed of decline they experience. However, caregivers are critical informants for understanding hospice performance because the majority of hospice support is provided at home with the caregiver playing a constant, essential role in daily care. Surveys of family caregivers have been shown to be acceptable, given moderate agreement between patient and proxy responders (Kutner et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2011).

Second, because experiences of hospice care vary substantially by care setting, separate survey versions were developed to allow for exploration of setting-specific issues. The most common settings for hospice care are the patient’s home (including assisted living facilities) and nursing homes, while smaller proportions of patients receive hospice care in freestanding hospice inpatient units (IPUs) and acute care hospitals. Across settings, patients differ in care trajectories, acuity of illness, and cost of service provision (Nicosia et al., 2009). Familial caregivers play important—if different—roles in each of the settings, generally providing hands-on care in home settings and advocating for care quality in nursing home settings.

Call for Topic Areas

CMS published a Federal Register notice, “Request for Information to Aid in the Design and Development of a Survey Regarding Patient and Family Member/Friend Experiences with Hospice Care” on January 25, 2013 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013). This call was designed to elicit suggestions for potential survey items and topics from organizations and stakeholder groups. The stakeholder groups provided suggestions and concerns about the following:

survey administration, including coordinating or deduplicating within and across surveys of the same or similar populations as the proposed hospice experience survey to minimize survey burden; combining survey administration modes, including Internet, to increase response rate and reduce costs; and consideration of survey vendor costs

timing of the survey, including recommendations that the timing of the survey administration begin one to three months after death, not sooner, and that surveys received several months or more after received be included in data analysis

length of the survey, including considerations regarding survey burden

survey population, including the suggestion that surveys be administered to hospice patients in addition to their caregivers, and targeting specific patient groups, such as those with and without cancer diagnoses

value of including an open-ended comment question for provision of valuable quality improvement feedback for hospices

importance of testing the survey among a diverse population so as to explore the cultural competence of care, sensitivity to preferences, beliefs, goals, and those who have experience with hospice

specific survey content, including questions on the following suggested topics:

perceptions of the adequacy and frequency of provider visits

measures of physical, psychosocial, and economic distress of patients receiving hospice care in the nursing home

level of support from the nursing home in obtaining a hospice referral

adequacy and redundancy of services from the hospice care team and the residential facility

information about experiences with medication changes

regular use of comprehensive symptom management instruments in the hospice setting

speed and degree of symptom management, as well as flexibility in meeting patient needs

availability of information to support informed decisionmaking by patients and their caregivers

degree to which hospice providers discussed, understood, respected, and met patient and caregiver preferences regarding the extent and intensity of life-prolonging care

specific items to address patient–provider communication; care coordination; shared decisionmaking; symptom management, including pain and anxiety; access to care; understanding hospice; respect and dignity; the care planning process, the caregiver’s confidence to perform care tasks; emotional and spiritual support; caregiver circumstances; and recommendation of the hospice to others.

Literature Review and Environmental Scan

We systematically reviewed the peer-reviewed literature on experiences with hospice and palliative care to identify survey content and any related data-collection methods and reporting and quality improvement issues. We also conducted a search of the gray literature (e.g., New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Report, Google, and the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse).

References captured in the searches were screened first by title and abstract and finally by review of the entire article for articles deemed relevant to the topic. The primary inclusion criteria were that the article (1) measured domains of patient or caregiver satisfaction and experience with hospice or palliative care and (2) included survey questions or instruments regarding patient or caregiver satisfaction or experience with hospice or palliative care. This included surveys developed by individual organizations and by researchers. Our primary exclusion criteria related to studies of pediatric populations and studies of health care provider satisfaction with hospice care. Researchers then reviewed each article, survey, or measure identified and abstracted information regarding the research study design and population, survey type, and content of survey questions and measures. For the most commonly used surveys, we also abstracted information about the identification of proxy respondents for after-death surveys, the timing and method of survey administration, and the health care setting assessed.

Our search of PubMed and PsycINFO identified 2,094 unique articles. After screening the titles using the inclusion and exclusion criteria described in the previous paragraph, reviewing abstracts, and reviewing full articles or reports, we identified 87 articles. These articles contained 50 unique surveys with available content. We characterized 14 content areas variably present across the 50 surveys. We reviewed an additional 39 surveys, measures, websites, and reports obtained from a search of the gray literature. Final review of other sources resulted in four other articles that were added to the full literature review and nine new surveys not identified in the literature review. Two tool kits (Hospice Assessment, Intervention, Measurement [AIM] Toolkit by the Prepare, Embrace, Attend, Communicate, and Empower [PEACE] Project and the Toolkit of Instruments to Measure End-of-Life Care [TIME]) were also identified. Through the review of articles and other sources, we identified 2,180 survey items (not unique).

To develop categories for potential domains, we used an iterative process whereby multiple researchers reviewed different survey questions and attempted to describe the key focus of the questions. After this exercise, one of the researchers finalized categories that were developed. This process resulted in 14 unique categories. The resulting most common categories were

information, care planning, and communication (number of survey questions = 632)

symptoms (303)

provider care (223)

spiritual, religious, and existential (187)

overall assessment (134)

psychosocial care (131)

personal care (80)

veteran care (72)

responsiveness and timing (71)

caregiver support (59)

quality of death and last days (51)

bereavement care (33)

environment (28)

patient-centered care (20)

financial (14).

Many of the survey questions identified through this literature search were found in multiple studies and had been tested and validated in one or more settings.

We also examined the survey administration procedures, including mode and timing. The primary mode of administration was a mailed survey. Other modes of survey administration included computer-assisted telephone, in person, mixed mode (in person and telephone, in person and mail), paper completed at site, and telephone. There was considerable variation in timing of survey administration across articles and among the same surveys, indicating that there is little consensus about when each survey should be administered. In four articles, surveys were administered to patients before death (i.e., two to seven days after a do-not-resuscitate order), and, in 37 articles, surveys were administered to caregivers after the patient’s death. The shortest reported time frame after death for survey administration was three to six weeks, and the longest time frame reported was up to 372 days after death. The majority of articles (n = 21) reported that surveys were administered within approximately one to six months after death.

Technical Expert Panel

In December 2012, we convened a TEP, including experts on hospice care quality, survey research, and performance measurement and improvement, as well as people representing organizations that could have a major influence on the adoption of a standardized hospice care survey and promotion of its use in public reporting and quality improvement. The TEP provided feedback regarding field test survey methods, survey design principles, and domains for the field test. Two main themes emerged from the TEP discussion. First, from the perspective of both CMS and the community of hospice providers, the unit of care for the survey is the patient and the family. Second, given plans to publicly report survey results, TEP participants noted the importance of developing survey content that is useful to consumers for prospective decisionmaking (i.e., to select a hospice). Survey content needs to allow for retrospective evaluation of hospice services because that would be useful for both quality improvement and CMS monitoring of care quality.

The TEP agreed that it was important to include in the field test hospices that varied according to size (i.e., number of deaths), geographic region, and chain status. Panel members recommended also considering including hospices that vary with regard to affiliation with a health system, ownership, and urbanicity.

TEP members agreed with the proposed exclusion criteria for sampling informal caregivers (i.e., family members or friends) within hospices: patient died within 48 hours of admission, no caregiver is listed in hospice records, or primary caregiver in records is a nonfamilial or friend (i.e., legal) guardian. TEP members also agreed that the survey should be administered no sooner than one month after death and no later than six months after death but noted that the logistics of sampling (i.e., receipt of data from hospices, data processing and mailing) likely preclude sampling before six weeks after death. It was agreed that the aim would be a median time of between one and three months, based on feasibility considerations.

TEP members agreed with the main survey content domains proposed: access to care and responsiveness, communication, shared decisionmaking, care coordination, symptom management and palliation, information and skills for caregivers, emotional and spiritual support, environment, and overall rating of care. They also made recommendations for consideration of supplemental content specific to veterans because this group of patients is more common than any other individual cultural group for which CMS might consider developing specific survey content. TEP members also emphasized the value of an open-ended question for quality improvement purposes.

TEP members also suggested that the following concepts potentially be explored in the survey:

degree to which the respondent is the family member or friend most knowledgeable about the patient’s hospice care

coordination between hospice and nonhospice personnel

degree to which the hospice team listened carefully to the family member

communication with caregivers who live far away geographically

assessment of whether the caregiver or patient needed help to manage communication across providers

management of bowel symptoms

Spanish-language version only: degree to which caregivers received the language services they needed

availability of a hospice care team member who spoke the patient’s or family’s language (if not English)

degree to which the patient and family’s wishes were respected regarding where and how the patient died (recognizing that not all patients can die where and how they might like)

care planning and goal setting for care

services for which hospice is responsible (beyond medical equipment, which was already covered in the draft survey)

making volunteers available to patients and caregivers

pharmacy services (e.g., getting medicines in a timely manner).

Cognitive Testing

Informed by input from the call for topic areas, literature review, qualitative interviews, and TEP, we drafted and refined three setting-specific survey instruments for cognitive testing: one for the home setting, one for the nursing home setting, and one for the inpatient setting, including both freestanding hospice IPUs and acute care hospitals.

The team completed three rounds of cognitive interviews to test interpretation and comprehension of survey content, including 11 English interviews (six in round 1, three in round 2, and two in round 3) and four Spanish cognitive interviews. Six of the interviews were completed in person, and nine were completed by telephone. The participants all had recent experience acting as caregivers for family members in hospice care. Participation targets were designed to ensure variation in SES of respondents (i.e., low versus high income) and final setting in which hospice care was delivered (i.e., home, nursing home, IPU). Participants were also recruited to ensure participation by African American and Hispanic caregivers. Details of participant location and patient care setting are provided in Table 2.2.

Table 2.1. Cognitive-Interview Location, Patient Care Setting, and Income

Interview |

Location |

Setting |

Income |

Round 1 |

Delaware Los Angeles Los Angeles Los Angeles North Carolina Kentucky |

Nursing home Nursing home Home Home IPU IPU |

Low High Low High Low High |

Round 2 |

Delaware Los Angeles Kentucky |

Nursing home IPU Home |

Low High Low |

Round 3 |

Los Angeles Los Angeles |

Nursing home Home |

High Low |

Spanish |

Los Angeles |

Home |

Low |

|

Los Angeles |

Home |

Low |

|

Los Angeles Florida |

Nursing home IPU |

High Low |

We recruited cognitive-interview respondents, and trained interviewers conducted the interviews using interview protocols specific to the patient’s care setting at time of death. Interviews were conducted at RAND, in participants’ homes, and by phone. A bilingual, bicultural interviewer conducted the Spanish interviews. Respondents taking part in the interview by phone were sent a survey via FedEx to complete during the call. Each interview began with the interviewer obtaining oral informed consent and describing the overall goals of the session. Interviews were audiotaped. Each respondent was paid $125 for participating.

Following each cognitive interview, project staff drafted summaries from the audio recordings and paper notes taken during each interview. After the first six interviews, the team participated in a debriefing meeting to discuss the instrument, identify common problem areas, and come to consensus about ways to change items to address the problems identified with the instrument during round 2 of cognitive testing. A similar meeting took place after round 2 interviews. Two additional interviews were conducted to test the final revisions to the instrument. Key findings are summarized below.

General Findings

Respondents whose family members were in more than one care setting had difficulty including only the final care setting in their responses. In round 2, we tested the carrier phrase, “While your family member was in his or her last location of hospice care” to determine whether the mention of “last location” would focus respondents on the final setting. However, the wording was confusing and irritating to nearly all of the respondents. After review of data showing that the proportion of patients who change care settings is quite small, the team chose to revert to the original wording, “While your family member was in hospice care.”