• Attachment A - Informed Consent - Leaders Training Module

Attachment A - Leader module 10-6-14 .docx

Improving Hospital Informed Consent with Training on Effective Tools and Strategies

• Attachment A - Informed Consent - Leaders Training Module

OMB: 0935-0228

I mproving

Hospital Informed Consent with an Informed Consent Toolkit

mproving

Hospital Informed Consent with an Informed Consent Toolkit

Contract # HHSA290201000031I / TO 3

Deliverable 3.1.2

FINAL

Informed Consent Toolkit

Leaders Storyboard

For Pilot Test

October 6, 2014

Prepared for:

Cindy Brach, MPP

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Submitted by:

Abt Associates Inc.

55 Wheeler

Street

Cambridge, MA 02138

Introduction

In medical care, informed consent is a process of communication between clinician and patient that results in the patient's authorization or agreement to undergo a specific medical intervention. All too frequently, however, patients do not understand the benefits, harms, and risks, alternatives of their treatments even after signing a consent form.

In response to this challenge, Abt Associates, the Joint Commission, the Fox Chase Cancer Center and Temple University have been contracted by AHRQ to develop, test and make available to hospitals and the medical community an improved Toolkit on informed consent to medical treatment. This toolkit will draw from several sources, including:

A Practical Guide for Informed Consent, developed by Suzanne Miller and Linda Fleisher (Temple University) with funding by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Rozovsky F. Consent to Treatment: A Practical Guide, 4th Ed.(2013). Aspen Publishers.

Preliminary research including an updated environmental scan of the peer-reviewed and grey literature on informed consent

Input from an expert and stakeholder panel

Published sources will be referenced in a “resources” section of the toolkit.

The toolkit will be delivered in the form of two training modules, each providing approximately 1 hour of continuing medical education, to be pilot-tested through the Joint Commission’s Learning Management System. One training module will be designed for health care professionals, the other for hospital leaders.

The present document is the draft toolkit for hospital leaders in quality, safety, risk management, medicine, nursing, interpreter services, and other areas. It is presented as a storyboard. Once the storyboard is finalized, it will go into production and, upon satisfactory completion of the production process, it will be uploaded into the learning management system for pilot-testing.

Project name |

AHRQ Informed Consent Toolkit |

Course Title |

Making Informed Consent an Informed Choice: Training for Health Care Leaders |

Slide 1: Welcome and Overview |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Present the education accreditation notes in a smaller font or on a scrolling screen to limit learner interference |

Making Informed Consent an Informed Choice: Training for Health Care Leaders

Informed Consent requires clear communication about choices. It is not a signature on a form.

Goal

Informed Consent Informed Choice

Overview

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of The Joint Commission/Joint Commission Resources and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Joint Commission Resources is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians”. – ACCME Accreditation Statement Policy |

Making Informed Consent an Informed Choice: Training for Health Care Leaders.

Welcome and THANK YOU for your interest in improving the informed consent process for your patients. Informed consent for medical treatment requires clear communication about choices. It’s not a signature on a form. It’s a communication process in which a patient is given information about his or her options for medical treatments or procedures, and then selects the option that is the best fit for his or her goals and values.

The goal of this training is to help you make informed consent an informed choice in your hospital. In this training, you will find:

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of The Joint Commission/Joint Commission Resources and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Joint Commission Resources is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians”. – ACCME Accreditation Statement Policy |

Slide 2: Course Scope |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

In the resources section: please link to these resources on informed consent to research: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/education/index.html http://www.ahrq.gov/funding/policies/informedconsent/index.html

Please also include this legal reference on end-of-life care: Rozovsky, FA (2013). Refusing treatment, dying and death, and the elderly. Section 10.6, pp.10-23 –10-30. In: Consent to Treatment: A Practical Guide. 4th ed. New York, NY: Aspen Publishers: Wolters-Kluwer Law & Business. |

Course Scope

This course focuses on informed consent for medical treatment It does not focus on:

See “Resources” for references on these topics.

|

Course Scope

Please note that this course focuses on informed consent to medical treatment.

It does not focus on blanket consent forms that patients sign upon admission to a hospital, since such forms provide very little information to patients.

It also does not focus on informed consent for research, nor on advance directives for end-of-life care.

If you wish to learn more about informed consent for research or advance directives, please see the “resources” section of this course.

|

Slide 3: Learning Objectives |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Learning Objectives:

|

At the end of this course, you will be able to:

|

Slide 4: Contents of CE activity |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Course Contents

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent Purpose: Examine existing problems with the process of informed consent for health care, principles of informed consent and implications for a good informed consent process

Section 2: Crafting and disseminating your informed consent policy Purpose: Assess current policies, develop and disseminate improved informed consent policies

Section 3: Building systems to improve the informed consent process Purpose: Describe systems and resources that need to be put in place to support the effort to improve the informed consent process

Section 4: Championing change - Developing and implementing an action plan Purpose: Learn how to generate the organizational will and momentum to improve the informed consent process in your hospital

All sections of this activity are required for continuing education credit.

|

Course Contents The information in this course is organized into the following sections: Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent The purpose of Section 1 is to examine existing problems with the process of informed consent for health care, principles of informed consent and implications for a good informed consent process

Section 2: Crafting and disseminating your informed consent policy Section 2’s purpose is to assess current policies, develop and disseminate improved informed consent policies

Section 3: Building systems to improve the informed consent process The third section’s purpose is to describe systems and resources that need to be put in place to support the effort to improve the informed consent process

Section 4: Championing change - Developing and implementing an action plan The purpose of Section 4 is to learn how to generate the organizational will and momentum to improve the informed consent process in your hospital All sections of this activity are required for continuing education credit.

|

Slide 5: Course Navigation |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Will need to update navigation instructions as necessary.

Please provide an option for closed captioning so that the module will be 508 compliant

Note to programmers – use BACK not PREV for the button name. |

Course Navigation

|

Before you get started, take a moment to learn how to navigate in this course:

If you exit the module before it is over, you’ll be asked if you want to resume (where you left off) the next time you watch the module.

|

Slide 6: Authors and Disclosures |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Scroll to view authors/planners |

Authors and Disclosures As an organization accredited by the ACCME and the ANCC, Joint Commission Resources requires everyone who is a planner or faculty/presenter/author to disclose all relevant conflicts of interest with any commercial interest. Nurse Planners Name Jill Chmielewski, RN, BSN, MJ Title: Associate Project Director, The Joint Commission Disclosure: Jill Chmielewski has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Physician Planner Name: Daniel Castillo, MD Title: Medical Director, Division of Healthcare Quality Evaluation, The Joint Commission. Disclosure: Dr. Castillo has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Planning Committee Members Name: Cindy Brach, MPP Title: Senior Health Policy Researcher, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Disclosure: Ms. Brach has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Melanie Wasserman, PhD, MPA Title: Senior Associate, Abt Associates Disclosure: Dr. Wasserman has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Salome, Chitavi, PhD Title: Project Director, The Joint Commission Disclosure: Dr. Chitavi has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Linda Fleisher, PhD, MPH Title: Senior Scientist, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Disclosure: Dr. Fleisher has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Suzanne Miller, PhD Title: Professor, Fox Chase Cancer Center Disclosure: Dr. Miller has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Sarah Shoemaker PhD, PharmD Title: Senior Associate, Abt Associates Disclosure: Dr. Shoemaker has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Dina Moss, MPP Title: Senior Science Analyst, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Disclosure: Ms. Moss has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Technical Advisory Panel Name: Mary Ann Abrams, MD, MPH Title: Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Ohio State University College of Medicine and Nationwide Children’s Hospital Disclosure: Dr. Abrams has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: David Andrews Title: Patient Advisor, Georgia Regents Medical Center Disclosure: Mr. Andrews has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Ellen Fox, MD Title: Executive Director, National Center for Ethics in Health Care, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Disclosure: Dr. Fox has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Barbara Giardino, RN, BSN, MJ, CPHRM, CPPS Title: Risk Manager, Rockford Health System, Illinois Disclosure: Ms. Giardino has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Jamie Oberman, MD Title: Navy Medical Corps Career Planner, Office of the Medical Corps Chief, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Disclosure: Dr. Oberman has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Yael Schenker, MD, MAS Title: Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, Section of Palliative Care and Medical Ethics, University of Pittsburgh Disclosure: Dr. Schenker has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Faye Sheppard, RN, MSN, JD, CPHRM, CPPS, FASHRM Title: Principal, Patient Safety Resources, Inc. Disclosure: Ms. Sheppard, Esq. has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Jana Towne, BSN, MHCA Title: Nurse Executive, Whiteriver Indian Hospital Disclosure: Ms. Towne has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Dale Collins Vidal, MD, MS Title: Professor of Surgery, Giesel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and Chief of Plastic Surgery, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center Disclosure: Dr. Collins Vidal has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Matthew Wynia, MD, MPH, FACP Title: Director, Institute for Ethics & Center for Patient Safety, American Medical Association Disclosure: Dr. Wynia has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Credits Available ACCME ANCC ACHE IACET

There are no fees for participating in or receiving credit for this online educational course.

A certificate of CE/CME is available for print at the end of each module.

Original release date: xx-xx-xxxx Last reviewed: xx-xx-xxxx Termination date: xx-xx-xxxx Joint Commission Resources is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians. Joint Commission Resources takes responsibility for the content, quality, and scientific integrity of the CME activity. Joint Commission Resources designates this educational activity for the listed contact hours of AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. Joint Commission Resources is also accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s Commission on Accreditation. Joint Commission Resources designates this continuing nursing education activity for the above listed contact hours. Joint Commission Resources is provider approved by the California Board of Registered Nursing, provider number CEP 6381, for the listed contact hours. Joint Commission Resources is authorized to award the listed hours of pre-approved ACHE Qualified Education credit for this program toward advancement or recertification in the American College of Healthcare Executives. Participants in this program wishing to have the continuing education hours applied toward ACHE Qualified Education credit should indicate their attendance when submitting application to the American College of Healthcare Executives for advancement or recertification. The Joint Commission Enterprise has been accredited as an Authorized Provider by the International Association for Continuing Education and Training (IACET). |

Authors and Disclosures As an organization accredited by the ACCME and the ANCC, Joint Commission Resources requires everyone who is a planner or faculty/presenter/author to disclose all relevant conflicts of interest with any commercial interest. Nurse Planners Name Jill Chmielewski, RN, BSN, MJ Title: Associate Project Director, The Joint Commission Disclosure: Jill Chmielewski has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Physician Planner Name: Daniel Castillo, MD Title: Medical Director, Division of Healthcare Quality Evaluation, The Joint Commission. Disclosure: Dr. Castillo has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Planning Committee Members Name: Cindy Brach, MPP Title: Senior Health Policy Researcher, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Disclosure: Ms. Brach has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Melanie Wasserman, PhD, MPA Title: Senior Associate, Abt Associates Disclosure: Dr. Wasserman has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Salome, Chitavi, PhD Title: Project Director, The Joint Commission Disclosure: Dr. Chitavi has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Linda Fleisher, PhD, MPH Title: Senior Scientist, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Disclosure: Dr. Fleisher has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Suzanne Miller, PhD Title: Professor, Fox Chase Cancer Center Disclosure: Dr. Miller has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Sarah Shoemaker PhD, PharmD Title: Senior Associate, Abt Associates Disclosure: Dr. Shoemaker has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Dina Moss, MPP Title: Senior Science Analyst, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Disclosure: Ms. Moss has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Technical Advisory Panel Name: Mary Ann Abrams, MD, MPH Title: Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Ohio State University College of Medicine and Nationwide Children’s Hospital Disclosure: Dr. Abrams has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: David Andrews Title: Patient Advisor, Georgia Regents Medical Center Disclosure: Mr. Andrews has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Ellen Fox, MD Title: Executive Director, National Center for Ethics in Health Care, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Disclosure: Dr. Fox has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Barbara Giardino, RN, BSN, MJ, CPHRM, CPPS Title: Risk Manager, Rockford Health System, Illinois Disclosure: Ms. Giardino has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Jamie Oberman, MD Title: Navy Medical Corps Career Planner, Office of the Medical Corps Chief, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Disclosure: Dr. Oberman has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Yael Schenker, MD, MAS Title: Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, Section of Palliative Care and Medical Ethics, University of Pittsburgh Disclosure: Dr. Schenker has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Faye Sheppard, RN, MSN, JD, CPHRM, CPPS, FASHRM Title: Principal, Patient Safety Resources, Inc. Disclosure: Ms. Sheppard, Esq. has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Jana Towne, BSN, MHCA Title: Nurse Executive, Whiteriver Indian Hospital Disclosure: Ms. Towne has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Dale Collins Vidal, MD, MS Title: Professor of Surgery, Giesel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and Chief of Plastic Surgery, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center Disclosure: Dr. Collins Vidal has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Matthew Wynia, MD, MPH, FACP Title: Director, Institute for Ethics & Center for Patient Safety, American Medical Association Disclosure: Dr. Wynia has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Credits Available ACCME ANCC ACHE IACET

There are no fees for participating in or receiving credit for this online educational course.

A certificate of CE/CME is available for print at the end of each module.

Original release date: xx-xx-xxxx Last reviewed: xx-xx-xxxx Termination date: xx-xx-xxxx Joint Commission Resources is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians. Joint Commission Resources takes responsibility for the content, quality, and scientific integrity of the CME activity. Joint Commission Resources designates this educational activity for the listed contact hours of AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. Joint Commission Resources is also accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s Commission on Accreditation. Joint Commission Resources designates this continuing nursing education activity for the above listed contact hours. Joint Commission Resources is provider approved by the California Board of Registered Nursing, provider number CEP 6381, for the listed contact hours. Joint Commission Resources is authorized to award the listed hours of pre-approved ACHE Qualified Education credit for this program toward advancement or recertification in the American College of Healthcare Executives. Participants in this program wishing to have the continuing education hours applied toward ACHE Qualified Education credit should indicate their attendance when submitting application to the American College of Healthcare Executives for advancement or recertification. The Joint Commission Enterprise has been accredited as an Authorized Provider by the International Association for Continuing Education and Training (IACET). |

Slide 7: Principles of Informed Consent |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

A good informed consent process can:

Problems with informed consent:

|

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Patients and health care teams alike benefit when a patient’s consent to treatment is fully informed as the result of a clear, comprehensive and engaging communication process.

A good informed consent process has many benefits. It helps patients to make informed decisions, strengthens the therapeutic relationship, and can improve follow-up and after-care. When patients and their families understand the benefits, harms, and risks in advance, they can be partners in patient safety, and they can better cope with any poor outcomes that may happen as a result of treatment. This makes it less likely that the patient would sue the clinician when a poor outcome occurs.

Unfortunately, there are many problems with the informed consent process in hospitals today.

Both clinicians and patients often treat informed consent as a nuisance, a formality, and an obstacle on the way to care.

This is a problem, because even after signing a consent form, many patients don’t understand basic information about the benefits, harms, and risks of their proposed treatment, including the possibility of poor outcomes; and some patients may not understand that they can say no.

As a result, informed consent is one of the top 10 most common reasons for medical malpractice suits.

|

Slide 8: When “informed” consent isn’t informed |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

JAMIE: VISUAL

Show last 1:45 minutes of video clip of Toni talking: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubPkdpGHWAQ. This is not a good quality clip, but it can be extracted from the AMA health literacy video.

When audio on Art starts, add picture of Art (use a stock photo, or we can ask the person who contributed this story, Audrey Riffenburg, if she would share a real picture). When the quote from Art begins (i.e., What the hell do you mean…), add conversation balloon.

When audio on Dai starts, add his picture (use a stock photo) and the buttons.

|

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

When “informed” consent isn’t informed

Picture of Toni with link to video. Caption: Toni Cordell had a hysterectomy without realizing it.

Picture of older White male in a hospital bed with doctor standing next to him. Conversation bubble, “What do you mean! I’m not going to be able to talk?”

Picture of young Vietnamese man with injured arm. Caption:

|

Examples of failures in informed consent include the story of Toni Cordell. Toni had a hysterectomy without realizing the procedure recommended to solve her “woman’s problem” was the removal of her uterus.

Click on the picture of Toni to hear her describe what happened.

While Toni’s experience was not recent, failures in informed consent happen in hospitals every day.

Take Art, for example. He agreed to have surgery to remove throat cancer after his doctor explained it using terms like “laryngectomy,” “palliative trach,” “ventilator problems,” “bronchiecstasis,” and “purulent bronchitis.” Then his adult daughter explained, “Dad, what the doctor is saying is that with the surgery, you would have your voice box taken out. You wouldn’t be able to talk anymore. You’d have a breathing hole through the front of your throat for the rest of your life. You’d have to keep the hole protected so germs couldn’t go straight into your lungs. And you’d have a tube in your breathing pipe that you’d have to take care of every day.” Art was surprised and got angry. He asked, “What the hell do you mean! I won’t be able to talk?!”

Let’s look at one more case. Dai is a young agricultural worker who speaks only Vietnamese. He arrived at the hospital with a badly injured arm. The hospital wanted to perform an invasive diagnostic test and gave Dai a poorly translated consent form to sign. Dai signed it, because he thought that if he didn’t, he wouldn’t be given pain reliever.

Since these patients weren’t truly informed, we can’t say that they gave informed consent. |

Slide 9: Ethical Principles and Legal Standards |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Principle of Autonomy

P

Patients’ Rights to Informed Consent:

|

The ethical principle of autonomy gives patients the right to decide what happens to their bodies.

The legal doctrine on informed consent in health care has evolved over time and varies from state to state. But in every state, by law, patients have the right to:

|

Slide 10: Ethical Principles and Legal Standards |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Legal Standard for “Adequate Disclosure”:

|

State law defines what constitutes adequate disclosure – what you are required to tell patients.

In most states, adequate disclosure is the duty of the clinician who is providing the treatment. It can’t be delegated to another person. The information to be disclosed must include:

Many states have additional requirements. |

Slide 11: It’s Not About the Form |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Digital Ignite to explore opportunities for interactive learning for this slide |

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Signed Form ≠ Informed consent

L

S Risk

Liability

[Picture of MD talking to patient with question marks over patient’s head?]

“The statute requires a physician to "explain" the treatment, alternatives, and risks to his or her patient. ‘Explain’ means ‘to make plain or understandable: clear of complexities or obscurity’…. Explanation implies more than a mere correct statement of the facts. An explanation clarifies an issue or makes it understandable to the recipient …. For example, a physician can mouth words to an infant, or to a comatose person, or to a person who does not speak his or her language, but unless and until such patients are capable of understanding the physician’s point, the physician cannot be said to have explained anything to any such person.”

Macy v. Blatchford case, Oregon Supreme Court, 2000) |

In the previous slide we described what clinicians have to tell patients as part of obtaining their consent. But telling patients isn’t enough for consent to be informed, even if patients sign the form.

The consent form exists to document that the patient has been provided information, understood the information and agreed to a particular treatment or procedure. A signed consent form actually implies that prior to the patient’s signing, a process of adequately informing the patient and ensuring understanding has taken place. Yet, many patients sign informed consent forms even when they don’t understand the procedure, its benefits, harms, risks, or alternatives to treatment.

If the patient didn’t understand the information presented, it’s a patient safety problem, and you may be sued.

For example, in the Macy versus Blatchford case the Oregon Supreme Court, discussing whether a physician failed to obtain a patient’s informed consent for surgery, made the point that informing without understanding does not constitute informed consent. The court stated, “The statute requires a physician to "explain" the treatment, alternatives, and risks to his or her patient. ‘Explain’ means ‘to make plain or understandable: clear of complexities or obscurity’…. Explanation implies more than a mere correct statement of the facts. An explanation clarifies an issue or makes it understandable to the recipient …. For example, a physician can mouth words to an infant, or to a comatose person, or to a person who does not speak his or her language, but unless and until such patients are capable of understanding the physician’s point, the physician cannot be said to have explained anything to any such person.” |

Slide 12: Recognizing patient capacity for decision-making |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

JAMIE: consider bringing in bullets 1 by 1 with audio guidance – these are key points that need to be emphasized on-screen. I’m also open to other options to achieve that goal.

JAMIE: Let us explore alternative ways to stress the key points in this slide without using bullet points (graphics, images etc).

Consider making the 3rd and fourth bullets interactive (show the story, offer “yes/no” buttons, feedback to learner whether they got it right, then show the right answer

Add to the resources section this document on minors’ right to consent: https://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_OMCL.pdf

Link to Resources: FAQs for patients that lack decision making capacity.

|

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Patient capacity for decision-making

Most patients have capacity for decisions about medical treatment.

Key Criteria for patient capacity:

- Their condition - Options - Benefits, harms, and risks

Capacity can change over time and can vary depending on the decision to be made.

What’s not incapacity:

|

Patient capacity for decision-making

To uphold a patient’s right to participate in decisions about their care, it is important to recognize their capacity for decision-making.

The main thing to remember is that most patients have capacity for decision-making about their medical care and treatment.

Sometimes a patient is perceived as not having the ability to make an informed decision due to signs of intoxication, mental illness, cognitive impairment, or other factors.

In some cases, that perception is right, but in many cases, it is not.

The key criteria in assessing the patient’s capacity are the following. The patient has capacity if he or she:

Capacity is both the ability and the right to make a decision. It can change over time, and can depend on the decision to be made.

Patients don’t automatically lack capacity just because they disagree with the care team’s treatment plan. This is true even if members of the care team strongly disagree with the patient’s choice and think they know what’s best for the patient. Patients may refuse treatment even if it puts their lives in jeopardy.

Also, just because some patients can’t speak, have an intellectual or physical disability, mental illness, or cognitive impairment, or are under the influence of alcohol or pain medications, that does not automatically mean they lack capacity to make a decision. These conditions can make it harder to communicate and make decisions, though, so later in this course, we’ll share some communication strategies that can help. |

Slide 13: When to consult an authorized representative |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

JAMIE: When narrator says, “Click on the label ‘Authorized representative, show this text:

For minors: the authorized representative is a parent or legal guardian (show a picture of a mom next to a hospital bed with a young child in it with arrow pointing to mom saying “Authorized representative (Mom)” [or use a picture of a Dad next to hospital bed with young child, with the label “Authorized representative (Dad)”]

For adults: an authorized representative can either be designated by the patient (health proxy) or designated by someone other than the patient who has authority (for example the hospital policy can establish a hierarchy of authorized representatives in the absence of a proxy, typically spouse first, then adult children, then siblings, then other relatives).

The Cecile story is a true story of Cindy’s. She can record it. |

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Except:

Consult an authorized representative

Picture of Cecile [Caption: Click here to hear Cecile’s real life story on informed consent in an emergency situation.]

|

The patient’s family and friends often play an important role in the decision-making process, but in most cases, the final decision rests with the patient.

There are some exceptions to this rule, namely:

In these cases, you will need to consult with someone who is legally authorized to make a decision on the patient’s behalf. Click on the label “Authorized Representative,” to learn more about who can serve as an authorized representative.

Even when you’re working with an authorized representative, sharing information with the patient can help them to feel included, respected, and more comfortable with the care they are receiving.

A last exception is a life- or health-threatening emergency leaving no time to identify or speak with an authorized representative. In that case, the clinician can make a decision in the patient’s best interests. But often there’s still time to hold a consent discussion in emergency situations. Click on Cecile to hear her story about informed consent in an emergency.

Cecile: My father was recovering from minor surgery when I noticed he was trying to say something but was having trouble coming up with the words. I called in the nurse practitioner, and he decided to call the stroke team. Well, the stroke team arrived, performed an assessment, and started to wheel my father out the door. “Where are you taking him?” I asked. “To give him medicine to break up the blood clot,” they said. I said, “But you haven’t gotten consent.” “It’s an emergency!” they called, halfway out the door. But I was my father’s health proxy and I called after them, “You can’t give him anything until I consent.” That caught them short. “You’re right,” they agreed. “Can you walk with us while we tell you about this medicine?” And I did. I understand they were in a rush – they had to give him the medicine within 3 hours of his first symptoms, but that didn’t mean they didn’t have time to get consent.

Informed consent rules vary state-by-state and hospital-by-hospital, so check your hospital policy or state laws for further guidance.

|

Slide 14: Making Informed Consent an Informed Choice |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

JAMIE: During first paragraph have the word “consent” morph into the word “choice |

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Informed Consent Informed Choice

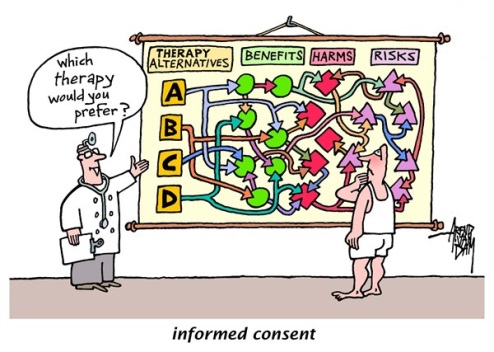

Informed choice requires:

Of course, the information must be presented in a way the patient can understand. [We will contact the author of this cartoon for permission. http://www.cagle.com/tag/informed-consent/]

|

The goal of this course is to help you mobilize resources and improve your hospital’s systems to make informed consent an informed choice for your hospital’s patients. Let’s talk about what we mean by “informed choice”.

What we often see in informed consent is that a clinician will recommend a treatment, explain the treatment, and then get the patient’s consent to deliver the treatment.

This may satisfy the minimum requirements for informed consent, but to truly make an informed choice, patients need clear, unbiased medical information they can understand about all their treatment options, including what happens if they decide to do nothing.

This is challenging, because clinicians may not always be in a position to provide information about all the options. It’s important to recognize that, and to know that patients may factor into their decision knowledge they’ve obtained through sources other than the clinician.

In addition to considering all the options, to make an informed choice, patients factor their values and preferences into the decision. Of course, in order for a patient to make an informed choice, information about the choices must be presented in a way that the patient can understand.

|

Slide 15: Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

|

||||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

||

|

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

Why focus on hospital informed consent policy? An analysis of The Joint Commission accreditation data:

Common problems:

Frequently asked questions:

|

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

This section will help you to assess your hospital’s current informed consent policy, improve it if need be, and better disseminate it.

You may be asking yourself, “Why should my hospital focus on improving its informed consent policy?

A recent analysis of The Joint Commission accreditation data suggests that many hospitals could benefit from improving their informed consent policies. Some hospitals were found out of compliance with accreditation standards because they did not have a formal written informed consent policy. The most frequent area of concern was failure to obtain informed consent in accordance with the hospital’s policy and processes. The analysis also revealed that many policies were overly broad and lacked the detail necessary for clinicians to be able to implement the policy.

Judging from the questions asked of The Joint Commission, clinicians need more detailed guidance from their hospital policies on informed consent. Examples of commonly asked questions include:

|

||

Slide 16: Informed Consent Policy Worksheet |

||||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

||

Upon completion of this track, the completed worksheet should be savable electronically/printable for reference as the learner continues to improve their informed consent policy.

In the resources section, include:

Resources on partnering with patients and families:

http://www.ipfcc.org/resources/guidance/index.html

[include the header and link. Publications are not free, so we can only make the link part of the resources, not the publications].

|

Gather your materials

[thumbnail of the informed consent policy worksheet]

Click here for Worksheet |

The next few slides will walk you through the essential elements of an informed consent policy. To get the most out of this section, please get a copy of your hospital’s informed consent policy. If you believe no policy is available, double-check that this is the case. Most accredited hospitals have a written informed consent policy. If your hospital truly does not have an informed consent policy, this section can help you to create one. In addition to obtaining your informed consent policy, please open the worksheet shown on this slide. You may print it or save it and work on it electronically. We’ll refer back to this worksheet in Section 4 of this course.

Policy examples given here are offered for illustrative purposes only, and this exercise is only a starting point. If your assessment shows any deficiencies in your policy, consider working to improve the policy with a Task Force that includes representatives of your health care facility’s legal, risk management, and medical teams, as well as patients. If you are not sure how to engage patients and families, the resources section of this module includes links to reports from the Institute of Patient- and Family-Centered Care on engaging patients and families in quality improvement. |

||

Slide 17: Statement of Purpose |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Instruction to designer: provide link to the following resource: Guidelines from the Office of Human Subjects Protection and the Code of Federal Regulations (Title 45 CFR Part 46)

Jamie – consider highlighting the “Note” to catch the eye of the learner. |

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

Statement of Purpose

Example Wellness Hospital Informed Consent Policy [Text box] Purpose: To ensure that every patient receiving invasive tests or procedures or other medical treatments at Wellness Hospital will be fully informed as to all benefits, harms, risks, and alternatives prior to choosing whether to consent.

Note: Policy examples given here are offered for illustrative purposes only.

Please fill out your worksheet for this slide.

|

Hospitals’ informed consent policies generally start with a statement of purpose.

Here is an example of a statement of purpose from a fictional hospital we’ll call Wellness Hospital.

Purpose: To ensure that every patient receiving invasive tests or procedures or other medical treatments at Wellness Hospital will be fully informed as to all benefits, harms, risks, and alternatives prior to choosing whether to consent.

Note that this example, and the other policy examples provided in this training, are just for illustrative purposes. Your hospital’s policy should be tailored to your hospital’s needs.

Please take a moment to fill out your worksheet for this slide, before moving on to the next slide.

|

Slide 18: General Policy |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Instruction to designer: provide link to the following resource: Guidelines from the Office of Human Subjects Protection and the Code of Federal Regulations (Title 45 CFR Part 46) |

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

Policy

Example – Wellness Hospital [Text box] Policy: The physician or Licensed Independent Practitioner (LIP) in charge will ask for consent from the patient or the patient’s authorized representative for all surgeries, invasive procedures or treatments involving risk, such as cardiac catherizations, lumbar punctures, biopsies, and administration of medicines.

Patients have the right to:

Note: This policy focuses on informed consent for medical procedures and treatments. Participation in research is governed by guidelines from the Office of Human Subjects Protection and the Code of Federal Regulations (Title 45 CFR Part 46).

Please fill out your worksheet for this slide.

|

In addition to the statement of purpose, a general policy may also be provided to outline the key principles of informed consent at the hospital.

Here is an example from our fictional hospital, Wellness Hospital.

The physician or Licensed Independent Practitioner in charge (also known as an LIP) will ask for consent from the patient or the patient’s authorized representative for all surgeries, invasive procedures, or treatments involving risk, such as cardiac catherizations, lumbar punctures, biopsies, and administration of medicines.

Patients have the right to:

The Wellness Hospital’s policy continues: Note: This policy focuses on informed consent for medical procedures and treatments. Participation in research is governed by guidelines from the Office of Human Subjects Protection and the Code of Federal Regulations (Title 45 CFR Part 46).

(Remember, this is just a fictional example of a policy).

Please take a moment to fill out your worksheet for this slide, before moving on to the next slide.

|

Slide 19: Who can obtain informed consent |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Who can obtain informed consent

Example – Wellness Hospital [Text box] For all tests, treatments, and procedures offered at Wellness Hospital:

Please fill out your worksheet for this slide.

|

Your policy should include a section stating who is responsible for obtaining informed consent.

In many states, the physician or licensed independent practitioner who orders or orders a test, prescribes a treatment, or performs a procedure is responsible for the informed consent process. In some states, informed consent tasks can be delegated. The Joint Commission has received many questions from hospital staff regarding the appropriate roles of physicians, nurses and other staff members in the informed consent process. In particular, persons who are delegated by the physician in charge to perform informed consent tasks are unsure of whether it is appropriate for the physician to delegate these tasks, and are unclear about how to execute their role in relation to the physician responsible.

If other staff members are playing a support role in your hospital’s informed consent process, your policy can clarify who should play what support roles. For example, a nurse can conduct patient education, and support staff can verify that a signed informed consent form is on file before a procedure takes place.

Here is an example from Wellness Hospital: For all tests, treatments, and procedures offered at Wellness Hospital:

Please take a moment to fill out your worksheet for this slide, before moving on to the next slide.

|

Slide 20: Procedures that require explicit consent |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

Procedures that require explicit consent

Example – Wellness Hospital [text box]

All surgeries, invasive procedures or treatments involving risk, such as cardiac catherizations, lumbar punctures, biopsies, and administration of medicines

Please fill out your worksheet for this slide.

|

Procedures that require explicit consent

This section of a hospital informed consent policy defines what procedures require explicit consent.

In the example of Wellness Hospital, the general policy, shown earlier, is that all surgeries, invasive procedures or treatments involving risk, such as cardiac catherizations, lumbar punctures, biopsies, and administration of medicines, require explicit consent.

Explicit consent doesn’t always a patient’s signature. For many procedures and treatments, oral consent can be sufficient. Later on, we’ll discuss hospital policies regarding how informed consent should be documented.

Please take a moment to fill out your worksheet for this slide, before moving on to the next slide.

|

Slide 21: Timing of informed consent discussion |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

When to Hold the Informed Consent Discussion

Example – Wellness Hospital [text box, both paragraphs below]

Timing of Informed Consent Discussions

Informed consent discussions must be held before tests, treatments, and procedures are carried out. Except in emergency situations, discussions should be held well in advance to give patients an opportunity to process the information. Obtaining informed consent when the patient is not in a position to readily say “No” does not give the patient a choice.

For example, having the informed consent discussion with a colonoscopy patient after the patient has completed the colon prep is not considered adequate timing.

Please fill out your worksheet for this slide.

|

When to Hold the Informed Consent Discussion

This section of your policy defines when informed consent should be obtained. At a minimum, the policy should state that consent must be obtained before the test, treatment, or procedure is given. Sometimes it helps to state the obvious.

In addition, you may want to have a statement of principle about the importance of giving patients enough time to process the information, and to not wait until it’s too late to say no.

For example, your policy could say:

Timing of Informed Consent Discussions

Informed consent discussions must be held before tests, treatments, and procedures are carried out. Except in emergency situations, discussions should be held well in advance to give patients an opportunity to process the information. Obtaining informed consent when the patient is not in a position to readily say “No” does not give the patient a choice.

For example, having the informed consent discussion with a colonoscopy patient after the patient has completed the colon prep is not considered adequate timing.

Please take a moment to fill out your worksheet for this slide, before moving on to the next slide.

|

Slide 22: Content of an Informed Consent Discussion |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Interactive exercise: informed consent policy worksheet, continued |

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

Content of an Informed Consent Discussion

Varies based on state laws, and should include at least:

Please fill out your worksheet for this slide.

|

You’ll want your informed consent policy to address what information should be covered in the informed consent discussion. In many states, the content of informed consent communications is mandated by law. At a minimum, a hospital policy should require informed consent discussions to include:

Please take a moment to fill out your worksheet for this slide, before moving on to the next slide.

|

Slide 23: Documentation of consent |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Interactive exercise: informed consent policy worksheet, continued |

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

Documentation of consent

Example – Wellness Hospital [Text box] Patients at Wellness Hospital sign a blanket consent form for treatment prior to admission. This form documents that the patient has been admitted to the hospital of his or her own accord, and covers non-invasive, routine, minimal risk procedures such as taking the patient’s blood pressure and asking intake questions.

Oral consent is required for routine treatments and procedures with very low, but not minimal risk, such as the administration of most drugs, vaccines, blood draws and minor procedures, such as routine X-rays.

A signed written consent is required prior to all surgery, and for any treatments and procedures that involve a significant risk of harm, pain or discomfort, and/or require sedation or anesthesia. For recurring treatments such as radiation or chemotherapy, a single form can be used to cover multiple sessions.

Qualified interpreters who interpreted an informed consent discussion and/or sight translated the informed consent form must also sign the form. In the case of telephone interpreters, the clinician conducting the discussion may write the interpreters name on the form.

Both oral and written consent must be documented in the patient’s electronic health record. If the informed consent discussion took place outside Wellness Hospital, consent must be verified by the physician and documented in the patient’s Wellness Hospital Electronic Health record before treatment occurs.

Please fill out your worksheet for this slide.

|

The Joint Commission receives frequent queries about how to document informed consent, suggesting that hospital policies are often insufficiently detailed on this topic.

Your policy should specifically identify the procedures and treatments that are covered by the blanket “consent to treatment” that patients sign upon admission to the hospital, and which procedures and treatments require separate explicit consent.

It should specify which ones require only oral consent, which ones require a signed consent form, including signed by interpreters when used, and how consent should be documented.

Joint Commission standards require a signed informed consent prior to surgery, except in emergencies, such as an unconscious patient requiring life-saving surgery when surrogate decision makers (such as a family member) cannot be consulted in time.

It can also be helpful to specify that recurring treatments such as radiation or chemotherapy can be covered by a single form. Since informed consent discussions often take place before the patient gets to the hospital, you’ll want your policy to address how to document informed consent in those instances.

Here is an example of a policy on documentation of consent from the fictional Wellness Hospital:

Patients at Wellness Hospital sign a blanket consent form for treatment prior to admission. This form documents that the patient is present of his or her own accord, and covers non-invasive, routine, minimal risk procedures such as taking the patient’s blood pressure and asking intake questions.

Oral consent is required for routine treatments and procedures with very low, but not minimal risk, such as the administration of most drugs, vaccines, blood draws and minor procedures, such as routine X-rays.

A signed written consent is required prior to all surgery, and for any treatments and procedures that involve a significant risk of harm, pain or discomfort, and/or require sedation or anesthesia. For recurring treatments such as radiation or chemotherapy, a single form can be used to cover multiple sessions.

Qualified interpreters who interpreted an informed consent discussion and/or sight translated the informed consent form must also sign the form. In the case of telephone interpreters, the clinician conducting the discussion may write the interpreters name on the form.

Both oral and written consent must be documented in the patient’s electronic health record. If the informed consent discussion took place outside Wellness Hospital, consent must be verified by the physician and documented in the patient’s Wellness Hospital Electronic Health record before treatment occurs.

Please take a moment to fill out your worksheet for this slide, before moving on to the next slide.

|

Slide 24: Exceptions to informed consent |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Interactive exercise: informed consent policy worksheet, continued

Cite this book in the resources section:

|

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

Exceptions to informed consent

What do to in an exception

|

Once your policy has outlined the general rules regarding informed consent, it should also note the exceptions.

In brief, the exceptions include certain emergencies, cases where the patient is incapacitated, most minors, patients whose treatment is required by law or court-order, and cases where a patient asks not to be informed.

Your policy should provide more details on each of these exceptions. The resources section cites a legal reference book by Fay Rozovsky that provides extensive information on this and other informed consent topics.

Your organization’s informed consent policy might first address what constitutes an emergency, such as if irreparable harm will result if immediate action isn’t taken. It should also provide clear guidance on what to do when exceptions arise. If time allows and treatment is not mandated by law or court-order, it may be possible to identify a surrogate decision-maker. Laws vary from state to state regarding who can be the patient’s duly authorized legal representative. Priority should be given to persons named in health care proxy or power of attorney documents, and the hospital may establish a hierarchy of decision-makers in the event that a health care proxy or power of attorney is not available. For example, the spouse or same-sex partner may be the first in line, followed by adult children, then siblings, and so forth, with the medical team making decisions as a last resort. This level of detail can help to reduce conflict when the patient is unable to make or express decisions and relatives disagree on the course of treatment.

You may also want to include in your hospital policy that clinicians should communicate with patients about their treatment even if the patient can’t communicate or consent to care, unless the patient has asked not to be informed. Communicating with the patient can help to alleviate feelings of anxiety and improve cooperation with treatment. |

Slide 25: Informed consent for minors |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Interactive exercise: informed consent policy worksheet, continued

Read the story of the teen girl in a different voice from that of the main narrator. We could ask the person who contributed the story, Jana Towne, to read and record it for us. |

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

Informed consent for minors

General policy

[PHOTO OF TEEN GIRL IN HOSPITAL – caption: click here for a real-life story from a nurse illustrating the importance of seeking assent from minors]

|

The hospital’s policy should include a section about consent for minors. In most cases, minors can’t legally consent to treatment, and parental consent is required. Nonetheless, in addition to gaining parental consent, you may want to encourage clinical staff to engage minor patients in their care when possible by providing information about their treatment and, for older children, seeking their assent. Assent is an agreement that does not have legal power.

When seeking assent, a commonly used rule of thumb is that teenagers, typically over the age of 14, can process similar information to what is given to their parents or guardian, and younger children, typically above the age of 7, can process information about what the experience will be, how it may help, how long it will take, and whether it might involve any pain or discomfort.

Click here for a real-life story from a nurse illustrating the importance of seeking assent from minors.

“We received a 14-year-old on our inpatient unit who had a PICC line in place. When talking to her mother regarding her medicines, she learned that the line terminated in her heart and was quite distressed by this. Later that day, the RN went to administer antibiotics and discovered that the patient had pulled the PICC out on her own and hidden it in her gown. That issue might have been avoided with a consenting process that more actively involved the patient, given her age.”

|

Slide 26: Informed consent for minors contd. |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Interactive exercise: informed consent policy worksheet, continued

|

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

Exceptions to the rule that minors can’t consent

|

There can be exceptions to the rule that minors can’t consent, and if these apply in your hospital, they should be noted in your policy.

First, some states allow mature minors to consent to treatment without their parents’ involvement. Definitions of mature minors vary. If your state allows it (or does not forbid it), your hospital policy should spell out who can be considered a mature minor. Some state laws define mature minors or the conditions under which a minor can consent. Absent guidance from the law, your definition of a mature minor can be based on age (for example, 14+), whether the minor is married or has children, or based on the minor’s ability to make a decision based on information about possible treatments and their benefits, harms, and risks.

Second, it is generally recognized that minors who are parents have the right to consent to care on behalf of their children.

Third, some states allow minors to consent to certain services without involvement from their parents, such as reproductive health care and substance abuse treatment. |

Slide 27: Clear communication policies |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

When the learner clicks on the picture of Magda, play the story provided in the comment. |

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

Clear communication policies

Picture of Magda with caption “Magda’s real life close call”

Example – Wellness Hospital [Text box] Wellness Hospital is committed to clear communication. To ensure that patient consent is truly informed, we strive to use plain language, clear and simple forms, and high-quality educational materials and decision aids. We also use teach-back to ensure that patients have understood the information that has been presented to them.

For patients with limited English proficiency, clinicians should conduct informed consent discussions with the assistance of a qualified interpreter. (See Wellness Hospital’s Language Access Plan for details on our interpreter services).

Clinicians should offer assistive devices, such magnifying readers and audio amplifiers, and ask patients if they would like forms read aloud to them. |

Clear communication policies

Regardless of what patients say or sign, patients haven’t consented unless they understand the information provided.

To foster a culture of clear communications with patients, consider including in your informed policy a statement to describe how clinicians can ensure that patient consent is informed. For example you can highlight the importance of plain language, clear and simple forms, the use of high-quality decision aids, graphics, and other educational materials, and teach-back. Teach-back is asking the patient to explain in their own words what they need to know or do, so clinicians can make sure they’ve explained things well.

Click on Magda to hear what a difference teach-back can make.

A clear communication policy should also address how to make reasonable accommodations to help patients participate in the informed consent process. Accommodations include providing professionally translated forms and language assistance for patients with limited English proficiency, using large print forms as well as magnifier reading glasses for patients with limited vision, and offering to read the form to all patients in case they are embarrassed to admit difficulties with reading.

Coming back to Wellness Hospital, here is an example of a clear communication policy:

Wellness Hospital is committed to clear communication. To ensure that patient consent is truly informed, we strive to use plain language, clear and simple forms, and high-quality decision aids, graphics, and other educational materials. We also use teach-back to ensure that clinicians have explained the information in a way that patients can understand.

For patients with limited English proficiency, clinicians should conduct informed consent discussions with the assistance of a qualified interpreter. (See Wellness Hospital’s Language Access Plan for details on our interpreter services.)

Clinicians should offer assistive devices, such magnifying readers and audio amplifiers, and ask patients if they would like forms read aloud to them. |

Slide 28: Compliance |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Compliance |

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

Compliance

Check compliance of your policy:

Offer Contact information for concerns/ complaints

Example – Wellness Hospital. [Text box] Compliance: If you have questions or concerns about this policy, or if you would like to report a violation of this policy, please call 1.800.xxx.xxxx or visit www.wellness.org/complianceline

|

Compliance

Before you share your policy, check with your legal, quality and safety teams to make sure it complies with Federal, State and local laws, regulations, such as Medicare and Medicaid rules, and accreditation standards.

A final part of your policy is offering a point of contact at the hospital to report concerns about or violations of the policy. The point of contact should have a clear process for referring complaints for quality improvement or disciplinary action, as appropriate. Here is an example: Compliance: If you have questions or concerns about this policy, or if you would like to report a violation of this policy, please call our compliance hotline at 1.800.xxx.xxxx or visit |

Slide 29: Disseminating the hospital’s policy on informed consent |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

For resources section, include examples of brochures/posters informing patients of their rights: http://www.aha.org/advocacy-issues/communicatingpts/pt-care-partnership.shtml

|

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

Disseminating the hospital’s policy on informed consent

|

To ensure that your hospital’s policy is implemented, both patients and clinicians should be aware of patients’ rights with regard to informed consent.

Consider several modes of dissemination to inform patients and clinicians about patients’ rights. Common modes of dissemination include posting the informed consent policy on your hospital’s Web site, placing posters on walls, and training clinicians and staff both during orientation and in-service. Plain language brochures in multiple languages can be distributed to patients upon admission, and the policy can also be disseminated through any patient- and family-centered care networks or online patient social networks your hospital may have. |

Slide 30: Periodic review of informed consent policy |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Section 2: Crafting and Disseminating Your Informed Consent Policy

Plan for periodic review of the hospital’s informed consent policy

|

As part of keeping your policy current, establish a time-frame for periodic review, for example, at least every two years. Conducting a periodic review should be part of one of the hospital leader’s responsibilities. Noting on the policy document the date when it was last updated can help to ensure that policies are kept current.

The policy should be evaluated in light of new legal or ethical doctrines, new evidence that changes which procedures are considered risky, and hospital experiences that suggest the policy should be clarified or changed. |

Slide 31: Section 3: Building Systems to Improve The Informed Consent Process |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

In resources section, please link to Temple Health’s “a Practical Guide for Informed Consent”: http://www.templehealth.org/ICTOOLKIT/html/ictoolkitpage1.html

|

Section 3: Building Systems to Improve the Informed Consent Process

System Supports

[thumbnail of the informed consent systems worksheet]

Click here for Worksheet

|

Clinical staff, however well intentioned, cannot improve informed consent on their own. Systems need to be put in place to support them in making informed consent an informed choice.

In this section, we describe the systems that can set the stage for an improved informed consent process. These include:

Please open the worksheet shown on this slide. You may print it or save it and work on it electronically. We’ll refer back to this worksheet in Section 4 of this course.

|

Slide 32: Compile a library of clear and simple forms |

||||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

||

For the “before” and “After” forms, use Mary Ann Abrams’s forms from here: http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/PublicHealth/HealthLiteracy/2013-APR-11/Abrams.pdf

Mary Ann has given informal permission (as part of her feedback) and we will ask for formal permission.

|

Section 3: Building Systems to Improve the Informed Consent Process

System Support #1: Compile a library of clear and simple informed consent forms

Choose forms that:

Test forms

Click here to see an example of an informed consent form before and after it was converted to a reader-friendly plain language format. Thumbnails of “before” and “after” forms; full forms pop up when learners click on the thumbnails |

Let’s start by describing the resources you need.

Your hospital should have a library of clear and simple informed consent forms for all the tests, treatments, and procedures that require a signed consent form according to your hospital’s informed consent policy. A signature on a form that the patient doesn’t understand doesn’t serve its purpose, which is to document the patient’s understanding from the informed consent discussion. Nor does it protect your hospital from liability.

Choose forms that are written using health literacy principles to maximize reading ease and comprehension. This includes writing in plain language and avoiding technical terms.

Clear and simple forms sequence information logically, breaking the information into chunks with informative headings. Layout also matters – lots of white space, large easy-to-ready fonts, and short line lengths all contribute to readability.

Don’t forget to include in your library forms that have been professionally translated in languages commonly spoken by your patients.

The best way to make sure the forms meet the needs of your patient population is to test both English-language and translated forms with their intended audience. Ask for feedback from a sample of diverse groups of patients within your patient community.

Click on the thumbnails of sample forms before and after simplification.

|

||

Slide 33: Where to obtain clear and simple forms |

||||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

||

Put in resources section:

Link to Queensland Health’s online database: http://www.health.qld.gov.au/consent/html/for_clinicians.asp

Resources on plain language: Pdf of “A Practical Guide to Informed Consent”, available here: http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/web-assets/2009/04/a-practical-guide-to-informed-consent

Link to: www.plainlanguage.gov

Link to: Toolkit for Making Written Material Clear and Effective: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Outreach/WrittenMaterialsToolkit/index.html?redirect=/WrittenMaterialsToolkit |

Section 3: Building Systems to Improve the Informed Consent Process

Support #1: Compile a library of clear and simple informed consent forms

Where to obtain informed consent forms

[Picture of Mary Ann Abrams, or picture selected by Mary Abrams to represent the Iowa Health system’s health literacy initiative to develop reader-friendly informed consent forms.] |

To build a library of informed consent forms, you can either use or customize a pre-packaged library, or develop your own consent forms.

Pre-packaged solutions include free online databases of informed consent forms, such as Queensland Health’s online database. A link to this database is provided in the resources section of this module. There are also commercial products, available for a fee, and some are designed to integrate with electronic health records. Be sure to assess pre-packaged solutions both before and after implementing them, to make sure they meet your clinicians’ and patients’ needs. You may be able to build on an existing library of forms and modify or customize it to meet your hospital’s needs.

If you are creating your own informed consent forms, you’ll want to make sure that your forms follow the health literacy principles that we just discussed. In addition to consulting plain language writing guides, try to enlist the help of health literacy experts. Be prepared to educate and collaborate with lawyers or risk managers to produce clear and simple forms that meet everyone’s needs.

In addition to serving as documentation, a clear and simple form can help clinicians structure their informed consent discussion and give them simple ways of explaining complex concepts. Involve clinicians in the development of forms so the forms match the flow of the informed consent discussion and to obtain buy-in for the new forms.

You’ll also want to provide forms in the key languages spoken by your patients. Make sure you use professional translators. Untrained translators are more likely to make mistakes, which can expose your hospital to liability.

Before you roll out your new forms to the entire hospital, pilot them with a few clinicians or in a few units. Get feedback from both clinicians and patients and revise accordingly. Finally, make sure you update your forms on a regular basis. You’ll want to modify the forms in your library as you learn of new treatment options or the expected outcomes or risks change.

Click on the picture to learn how the Iowa Health System developed reader-friendly informed consent forms.

For tips on developing clear and simple informed consent forms, see the “resources” section of this course. |

||

Slide 34: Maintain a library of high quality decision aids and patient education materials |

|

|||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

||

For the resources section, offer this resource to learn more about the standards for high-quality decision aids: Volk RJ, Llewelyn-Thomas H, Stacey D, Elwyn G (2013). Ten years of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration: evolution of the core dimensions for assessing the quality of patient decision aids.

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6947/13/S2/S1 what constitutes a high-quality decision aid: |

Section 3: Building Systems to Improve the Informed Consent Process

System Support #2 – Maintain a library of high-quality decision aids and patient education materials

Decision aids provide unbiased information. They can be:

Decision aids provide information about:

Decision aids are NOT a substitute for the informed consent discussion.

Using decision aids:

[Reference: Kinnersley et al 2013; Legare et al. 2014.]

|

While plain language informed consent forms can help patients to understand what they are consenting to, many patients need additional materials to help them make an informed choice. It can be very helpful for your clinical staff to have your hospital maintain a library of high-quality decision aids and other educational materials for common tests, treatments, and procedures offered in your hospital.

A decision aid presents options in an unbiased way to patients so that they can make an informed choice. Decision aids can be paper-based, audio-visual, multimedia, web-based, or interactive. Some decision aids are meant for patients to use on their own, while other decision aids are to be used jointly, with the clinician helping the patient process the information and highlight important points.

Decision aids provide information about:

Decision aids are designed to be part of, rather than replace, the informed consent discussion. For example, after a patient has viewed a decision aid, the clinician can use teach-back to make sure the patient understood the information, personalize the information for that patient, encourage and answer questions, and discuss the information in the context of the patient’s goals and values.

Clinicians often find that using decision aids helps them structure conversations about choices with patients. Research suggests using decision aids improves patients’ knowledge of the options available to them. Patients who use decision aids also have more accurate expectations of possible benefits, harms, and risks of their options. Most importantly, decision aids help patients clarify what matters most to them, makes them more likely to participate in the decision-making process and communicate effectively with their providers, and makes them more likely to reach decisions consistent with their goals and values.

And finally, patients whose decisions are fully informed through the use of decision aids are better able to cope with treatment outcomes and adverse events. An added advantage is that the use of decision aids can sometimes be used as evidence that consent was informed. In fact, Washington State passed a law in 2007 that established that the use of certified patient decision aids was evidence of patients’ informed consent.

|

||

Slide 35: 7Assessing the Quality of Decision Aids |

|

|||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

||

|

How do you know if you have a high-quality decision aid?

|

There are a lot of decision aids available. Not all of them are high quality. Here are some questions to consider when assessing the quality of decision aids:

Finally, a high quality decision aid will help patients be clear about what matters the most to them and factor those goals and values into their decision. |

||

Slide 36: Other patient education materials, finding high-quality aids, and maintaining your library |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

In resources section, please include links to:

Free databases of decision aids and other patient education materials: the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, and the Mayo clinic.

International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration: http://ipdas.ohri.ca/

this resource for assessing decision aids (under development):

and this resource for evaluating patient education materials (including decision aids): |

Section 3: Building Systems to Improve the Informed Consent Process

Support #2 – Maintain a library of high-quality decision aids and other patient education materials

Other patient education materials: