Attachment C - White Paper

Attachment-C-White-paper.docx

Experimental Economic Research

Attachment C - White Paper

OMB: 0536-0070

OMB Control Number 0536-0070, expires 06/30/2016

Attachment C

White Paper

Alternative tools for improving CRP cost-effectiveness

Peter Cramton, Daniel Hellerstein, Nathaniel Higgins, Richard Iovanna, Steven Wallander

Draft paper for internal discussion only. Not for external circulation. Do not cite.

Abstract

The Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) is the world’s largest conservation program, spending $1.9 billion in fiscal year 2012 to pay farmers to voluntarily establish conservation cover on 29.6 million acres of environmentally sensitive cropland.1 The program relies on two approaches to enroll land: a competitive system known as General Signup and a first-come, first-served system called Continuous Signup which does not use a competitive procedure. In the General Signup, farmers participate in a competitive auction by offering to enroll land for a payment. These offers are ranked according to an index of environmental benefit and a cost metric. Each offer is constrained by a parcel-specific bid cap. Both economic theory and practical experience from other types of government auctions (e.g.: timber sales, toxic asset purchase, and communication spectrum sales) suggest that modifying the current auction structure could make CRP more cost-effective. Research estimates that $380 million or 20% of current annual payments exceed producer’s costs. In this paper, we discuss options for controlling costs by adjusting the bid cap and/or using alternative auction mechanisms such as reference prices or groupings.

How does CRP work?

The Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) minimizes soil erosion, enhances water quality, and creates wildlife habitat by paying farmers to voluntarily take environmentally sensitive cropland out of production for a contract period of 10-15 years and instead establish a conservation cover of grass or trees. Specific CRP practices range from relatively straightforward native grasses or tree plantings, to structural practices such as grassed waterways and constructed wetlands.2

Producers are provided an annual rental payment, as well as assistance paying for practice establishment costs (“cost share”). Which producers enroll and how their annual payments are set determine overall program cost and the environmental benefits provided by the program.

The program relies on two approaches to enroll land: a competitive system known as General Signup and a first-come, first-served system called Continuous Signup. General Signup is a competitive auction through which offers to enroll land are ranked according to an index of environmental benefit and a cost metric. Some version of competitive General Signup has been utilized since the program began in 1985. General Signups have tended to take place annually and usually last four weeks, during which time FSA maintains an open call for bids from landowners. In contrast, Continuous Signup focuses on enrolling land in targeted geographic regions or in high-value conservation practices and makes fixed payments to offers that meet minimum criteria.

An offer to enroll in General Signup specifies the conservation practice that the producer seeks to establish, the parcel on which the practice is proposed, and the annual payment that the producer proposes to receive, i.e., the bid. The bid can be no greater than an offer-specific estimate that USDA generates. This estimate is designed to be equal to the annual payment the producer ought to be willing to accept to enroll in CRP. This bid cap can also be referred to as the estimated opportunity cost of – or reservation value for – participation.

Since 1996, the General Signup has ranked offers on the basis of a multi-dimensional index (the Environmental Benefits Index, or EBI) that reflects both cost (the bid) and anticipated environmental benefits. Offers are ranked according to the EBI; those above a cutoff set by the Secretary of Agriculture are enrolled.

Since 1996, Continuous Signup has also been used to encourage establishment of relatively intensive practices to address serious conservation concerns. This signup is year-round and non-competitive, with eligible offers enrolled on a first-come, first served basis. Continuous signup acreage often qualifies for extra payments (such as Signup Incentive Payments and Practice Incentive Payments), hence per acre payments are typically above the parcel’s bid cap.

Total enrollment in CRP is subject to acreage caps at the practice3 , county4, and national levels. The acres signed up in a given year cannot exceed the national cap set by current farm legislation, less the active contract acres that will remain in the program at the end of the year. Accordingly, this constraint varies considerably from year to year.

As of December 2013, approximately 260,000 contracts covering almost 20 million acres had entered the program through General Signup, and about 410,000 contracts covering nearly 6 million acres had entered the program through Continuous Signup.5 The average size of an enrollment is 75 acres and 14 acres, respectively, reflecting the fact that General Signup tends to enroll whole fields while Continuous Signup tends to enroll parts of fields (a consequence of the practices encouraged by Continuous Signup).

The issue: The CRP signup process discourages participation

General Signup operates as a reverse auction, an auction in which many potential sellers competing for payments from a single buyer. Auctions can be an efficient, cost-effective, and transparent way for USDA to meet conservation goals on private lands.

Auctions are often used for government procurement because they utilize competition to control costs. Costs are driven down because participants are uncertain whether or not their bids will be accepted. This causes bidders to reduce their asking prices in order to increase their chances of having their offer selected – of winning the auction.

In pay-as-bid auctions – auctions like the CRP in which accepted offers are paid the amount bid – participants will want to submit a bid that is low enough to be accepted, yet high enough to be profitable. Bidders resolve these opposing forces by submitting a bid that is above their reservation value (higher than the minimum amount that they would be willing to accept). The more certain a bidder is that their bid will be accepted – because, for instance, their land is highly environmentally sensitive – the higher they will bid above their reservation value. In many auctions, including the CRP, some participants are very certain of their prospects. These participants may be able to extract relatively large profits from the auction. Conversely, auction participants who are almost certain to be rejected are unlikely to make any offer to enroll.

Within General Signup, the EBI is the principle piece of information which farmers can use to predict the likelihood that their offer will be accepted. CRP bidders having particularly environmentally valuable land, having land with unusually low productive value, or having both, know that they can ask for an annual payment significantly higher than their opportunity cost and still be confident that their offer will be accepted. The fact that General Signup is a repeated auction may exacerbate the situation. Potential participants in General Signup auctions can observe past auction outcomes to determine the size of payments that they can ask for while still remaining confident that their bid will be accepted.

Empirical examinations of CRP signups generally find that there is a substantial difference between farmer bids and reserve rents. Kirwan, Lubowski and Roberts (2005) find that landowners are, on average, paid 20% above their opportunity costs. Similarly, Horowitz, Lynch and Stocking (2009) find that bids in an auction where the state purchases farmland development rights are 5-15% above landowner opportunity costs.

USDA has implemented bid caps in the General Signup to limit the bids that participants offer and prevent excessive payments. Bid caps are based on soil rental rates (SRRs), which are based on county-average dryland cash-rent estimates, soil-specific adjustment factors, and professional judgment.6 The intent of these bid caps is to limit farmers’ annual rental payments to an estimate of their opportunity costs. Importantly, these bid caps are estimates and thus both inherently imprecise and subject to bias.7 The imprecision and potential bias of the estimates, coupled with the imposition of bid caps, creates a situation in which the General Signup auction may actually fail to lower costs because participation rates in the auction are too low to induce significant price competition.

This counter intuitive result can arise when actual (unobserved) opportunity costs fall both above and below bid caps. Some potentially interested producers will be dissuaded from submitting an offer because the bid cap they face is less than their actual opportunity cost. If these producers have low opportunity costs, relatively expensive offers then replace the dissuaded bidders, costing more to satisfy an acreage target or enrolling fewer acres for a fixed budget.

The insights above can be illustrated with a simple example. Assume there are 100 landowners, each with a unit of land of homogeneous environmental quality. Agricultural profitability is uniformly distributed between $1 and $100. The government seeks to retire 50 units (1/2 of the parcels) of this environmentally homogeneous land, and to do so at minimum total cost.

Table 1: Simulation of Cost control with imprecise bid caps

Scenario |

Participation |

Total Cost |

No caps, single price |

All farms offer |

2,475 |

“Tight” bid cap |

About 2/3 of farms offer |

1,938 |

“Loose” bid cap |

All farms offer |

1,325 |

Consider first a General Signup without a bid cap: over time, bids gravitate toward the same market-clearing annual payment. With the acreage goal of 50 and a single payment ($P/acre) to all participants, the total cost of the auction would be (on average) $2,475.8 USDA pays farmers with opportunity costs less than $50 more than their opportunity costs.

Consider next two scenarios where the government imperfectly estimates each unit’s opportunity cost and uses this estimate to set the parcel’s bid cap. The assessment is either $1 below the true opportunity cost, exactly equal to the true opportunity cost, or $1 above the true opportunity cost, with equal probability.

1. A “loose” cap: The government makes an unbiased but imperfect estimate of each bidder’s opportunity cost, and sets the cap at this level plus $1. Because the bid cap is always equal to or higher than each bidder’s opportunity cost, all landowners will offer and will make (on average) $1 in profit, assuming participants submit bids equal to their bid cap.9 The total average expenditure will be $1,325.. Setting a loose cap reduces average total expenditure by $1,150 compared to the uncapped scenario.

2. A “tight” cap: The government makes an unbiased but imperfect estimate of each bidder’s opportunity cost, and sets the cap exactly at this level. On average, 1/3 of assessments will be below the true opportunity cost of the landowner; these landowners will not offer to enroll CRP. These parcels may be high cost or low cost. Assuming again that participants submit bids equal to their bid cap, summing the 50 lowest bids results in total average expenditure of $1,937.50, $538 less than the uncapped scenario. However, setting a tight cap results in increased expenditure of $613 compared with a loose cap.

Despite the simplicity of the example, it illustrates a broad general point: setting a cap can be beneficial, as both the tight and the loose cap reduce cost compared to an uncapped scenario. However, setting a tight bid cap i.e. too close to an unbiased estimate of opportunity cost can discourage participation, leading to less auction competition and a worse outcome for the government (Hellerstein and Higgins 2010).

The example illustrates the dangers of setting a cap too tightly. The setting of an optimal cap requires balancing the negative participation effects of a cap with the potential for lower bids. It is also important to note that bidders may behave differently when a cap is imposed relative to when no cap is imposed. For a more nuanced discussion of the potential effects of bid caps on bidding behavior and market equilibrium, see the appendix.

Different auction mechanism may improve the sign-up process

It may be possible to adjust the CRP signup process in a way that reduces program cost by encouraging greater participation and/or reducing profits to landowners. We consider three alternative reverse auction approaches.

Alternative 1: relaxed bid caps

The first alternative is a modest departure from the current General Signup: Set bid caps equal to an opportunity cost estimate (the current state) but add a factor to overcome the inherent imprecision in the estimate (i.e., a positive bias). If the relaxed bid cap increases participation and bid competition more than it increases the payments to participants, this approach will reduce program costs. As shown above, if bid caps aggressively seek to push bids lower, they can increase costs by driving down participation. To the extent that current bid caps decrease participation within the pool of lower-cost parcels, the program will have to accept a greater proportion of higher-cost offers.

Relaxed bid caps have been applied in other natural resource contexts: British Columbia calculates an estimate of value which it calls an upset price for timber stands that it wishes to sell at auction. Athey, Cramton, and Ingraham (2002) find that using a limit price equal to about 70% of this value is optimal. This limit price represents a 30% “rollback” from the estimate of value – the analog in the CRP would be setting the bid caps at 130% of estimated opportunity cost.

Alternative 2: reference price

Rather than serving as bid caps, opportunity cost estimates could be used to standardize bids. When used in this manner, the opportunity cost estimate is referred to as a reference price. The standardized bid is used for ranking in the same way that the raw bid is currently used. Therefore, a bid greater than its estimated reference price is ranked below another bid less than its reference price – even if the two bids are for the same amount of money. The current CRP offer ranking allows farmers to improve their ranking by offering less than their bid cap. The key difference in the proposed reference price mechanism relative to the current General Signup structure is that the bid cap is removed. Therefore, farmers may bid above the estimated soil rental rate. However, it also makes offers progressively less competitive as they increase relative to their individual soil rental rate.

For example, think of a reverse auction for apples and oranges. Since apples and oranges are different fruits, in order to consider the relative merit of apple-bids and orange-bids, the auctioneer would estimate a fair price for apples (say $0.50), and a fair price for oranges (say $0.75). Bids are then ranked relative to their estimated value. An apple bid of $0.60 (with a score of $0.60/$0.50 = 1.2) would rank lower than an orange bid of $0.60 (with a score of $0.60/$0.75 = 0.8) even though they are the same amount of money.

The appeal of a reference price mechanism is that no one is dissuaded from making an offer because their opportunity cost exceeds an imperfect cap. The apple bid in the example above is allowed to be submitted, even though it exceeds the auctioneer’s best estimate of value. The submitted bid is appropriately ranked lower, however, than the orange bid submitted at a price less than estimated value.10

Like current bid caps, reference prices could be based on SRRs and announced to farmers before they submit a bid. This approach is clearly convenient, preserving the current infrastructure used to produce estimates.

Alternatively, the process of calculating SRRs can be avoided with an endogenous reference price. The reference price for each parcel would not be known to the farmers at the time of the auction, but would be calculated after all bids are submitted, using the mean bid of a random sample of similar offers. This approach may further reduce profits by keeping reference prices unknown to the bidder. Conversely, not announcing a reference price upon which to base their bid might prove unsettling enough to some that they elect not to participate. While collusion could influence endogenous reference prices, the potential for and/or impact of it is minimized by the random sampling and by not basing the reference price on the mean bids of offers that share readily discernible characteristics.

Reference price auctions have been implemented in other contexts. A reference price auction was selected by the U.S. Treasury to purchase toxic assets under TARP legislation during the 2008 financial crisis. Reference price auctions have been the subject of substantial theoretical and experimental work. See for example Ausubel et. al. (2013), and Armantier, Holt, and Plott (2013 [http://www.aeaweb.org/articles.php?doi=10.1257/mic.5.4]). Olivier Armantier presents a succinct summary of reference price auctions in a recent Federal Reserve Bank of New York post. The case for reference price auctions is strong in the Treasury setting, where the reference price is the appropriate way for the Treasury to compare bids on securities of different values. In CRP the purpose is to reduce the competitive advantage of those farmers with lower opportunity cost while maintaining the incentive for all farms to bid competitively.

Alternative 3: Grouping

Similar offers can be grouped together according to opportunity cost estimates (e.g., $0-$30, $30-$50, etc.) or factors that relate to opportunity cost (e.g., geography, soil productivity categories, etc.). Offers could then compete for enrollment within these groups. This increases competition among strong bidders – i.e. farmers with high EBI scores compete with other farmers with high EBI scores; farmers with low opportunity costs compete with other farmers with low opportunity costs. Low-cost bidders tend to submit lower bids when they are competing with other low cost bidders.

USDA would commit to accepting some fraction of offers from each group. This fraction does not need to be identical for each group. For instance, USDA could commit to accepting a relatively large fraction of very low-cost offers (say 90%), and a relatively small fraction of high-cost offers (say 50%). Knowing that all low-cost bids will not be accepted increases the incentives for low-cost bidders to bid closer to their true opportunity costs. It may also increase the bids of high-cost bidder but the overall impact is reduced program costs.

When using a grouping approach, a uniform price auction may be better. In a uniform price auction, each bidder in a group receives the same price equal to the last accepted bid in the group. Because most bidders receive a payment greater than their bid, they have an incentive to bid their true opportunity cost and be selected knowing they will receive a higher payment. This approach works well if each group is sufficiently homogeneous and there are many bidders in each group.

Grouping works similarly to set-asides, which are common in government auctions. In an auction with a set-aside, a selection of goods must be won by qualified bidders. Ayres and Cramton (1996) found that the Federal Communications Commission increased revenue of spectrum sales by $45 million as a result of set-asides.11

The reference price approach can be fine-tuned more easily than the grouping approach; with the grouping approach, large numbers of bidders will be treated equally, whereas with the reference price approach individual-specific estimates of value would be used. On the other hand, bidders may find the grouping approach less arbitrary when there are natural groups that can be delineated by obvious characteristics (such as soil productivity). Setting the fractions accepted (or rejected) for each group may also lead to additional administrative burdens.

Going forward: Investigating how these alternatives impact CRP

These alternatives to the current signup processes can be examined rigorously in an experimental setting. A common approach in policy settings is to proceed incrementally: first, theory and experience inform the selection of a set of alternative policies; next these alternatives are tested in a laboratory; finally, the most promising policy alternative informs the design of a proof-of-concept pilot. This pilot can be designed as a field experiment so that the impact of the signup refinements can be precisely estimated.12

References

Armantier, Olivier, Charles A. Holt , Charles R. Plott (2010). “A Reverse Auction for Toxic Assets,” California Institute of Technology Social Science Working Paper 1330. Available at: http://authors.library.caltech.edu/20207/1/sswp1330.pdf

Athey, Susan, Peter Cramton, and Allan Ingraham (2002). “Setting the Upset Price in British Columbia Timber Auctions,” MDI Report for British Columbia Ministry of Forests. Sep. 2002. Available at: http://works.bepress.com/cramton/118

Ausubel, Lawrence, Peter Cramton, Emel Feliz-Ozbay, Nathaniel Higgins, Erkut Ozbay, and Andrew Stocking (2013). “Common-Value Auctions with Liquidity Needs: An Experimental Test of a Troubled Assets Reverse Auction,” Handbook of Market Design, Nir Vulkan, Alvin E. Roth, and Zvika Neeman (eds), Oxford University Press, Chapter 20, 489-554.

Ayres, Ian and Peter Cramton (1996). "Deficit Reduction Through Diversity: How Affirmative Action at the FCC Increased Auction Competition," Stanford Law Review 48 (1996) 761-815.

Hellerstein, Daniel and Nathaniel Higgins. 2010. The Effective Use of Limited Information: Do Offer Maximums Reduce Procurement Costs in Asymmetric Auctions? Agricultural and Resource Economics Review 39(2): 288-304.

Hellerstein, Daniel, Nathaniel Higgins and Michael Roberts, 2014. “Options for Improving Conservation Programs: Insights from Auction Theory and Economic Experiments.” USDA Economic Research Service Research Report, forthcoming.

Horowitz, J. L. Lynch, and A. Stocking (2009). “Competition-Based Environmental Policy: An Analysis of Farmland Preservation in Maryland,” Land Economics, University of Wisconsin Press, vol. 85(4): 555-575.

Kirwan, Barrett, Ruben Lubowski, and Michael J. Roberts. 2005. “How Cost Effective are Land Retirement Auctions? Estimating the Difference between Payments and Willingness to Accept in the Conservation Reserve Program.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 87: 1239-1247.

Appendix

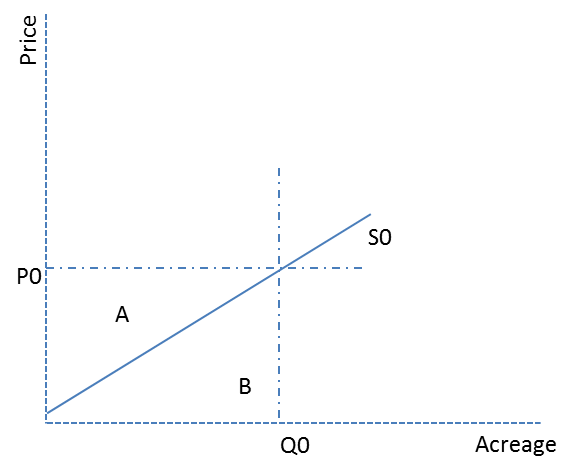

Consider the following illustrative example. We start with no bid cap, where a single price is paid to all accepted offers. Given a supply curve S0, a price of P0 will enroll Q0 acres (Figure 1). Total costs will be area A +B.

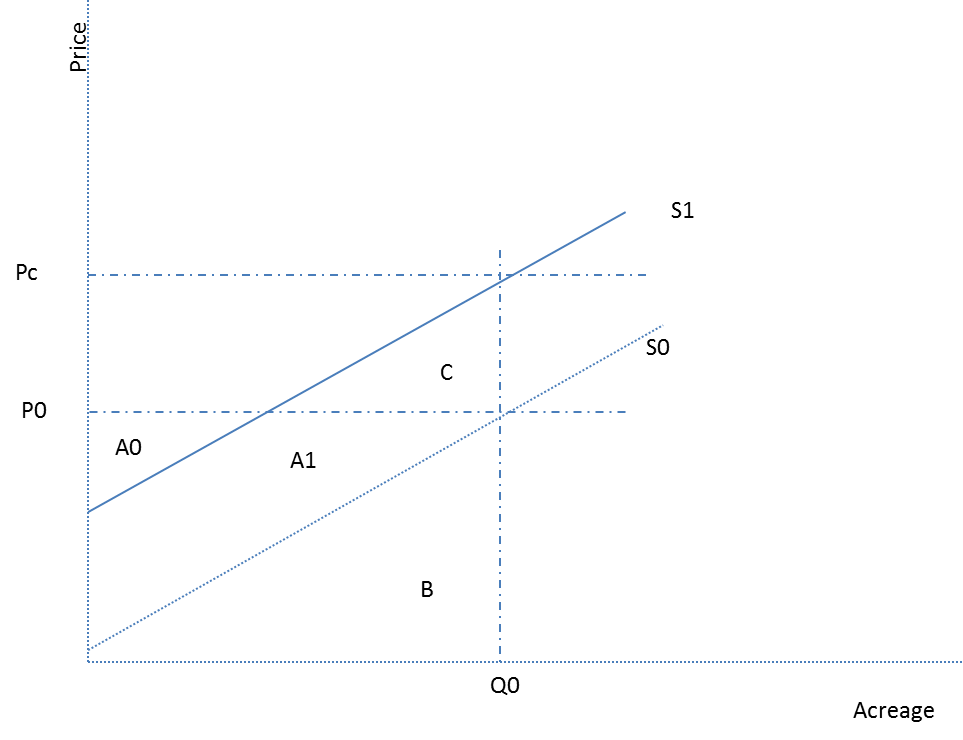

Now consider an auction with an offer-specific bid cap imposed; the bid cap is sometimes higher than a given producer’s opportunity cost, and sometimes lower. Producers interested in enrolling land into CRP are affected one of several ways:

Some of the same offers are enrolled, albeit with a payment rate constrained by their bid cap (lower than what it would have been otherwise).

Some producers that would have otherwise submitted competitive bids are dissuaded from submitting an offer because their bid cap fell short of their opportunity cost (not depicted in the figure).

Since some producers are not submitting bids, the supply curve shifts to S1 (Figure 2) – at any given price, fewer acres will be offered.

A bid cap does not simply influence existing bidders. Suppose the enrollment goal remains at Q0 – i.e. USDA wants to enroll a certain number of acres in the program. Because a tight bid cap reduces participation, the cutoff price (the maximum price paid for an offer) increases (moving from P0 to Pc in Figure 2). At this higher cutoff price, some high opportunity cost producers who were not previously interested in the program will make offers.

In the long run, potential bidders may recognize the fact that the cutoff bid is higher. General equilibrium effects would then cause producers whose bids were comfortably below the cutoff price, and below their bid cap, to raise their bids to the bid cap (at line S1).

The combination of these effects causes total cost to be A1+B+C in Figure 2. Area A0 is the saving from imposing the bid cap, while C is the cost due to the high cutoff price needed to obtain Q0. In this example, C is greater than A0.

Hence, in this illustrative example imposing a bid cap leads to an increase in total program cost.

Figure 1: No bid cap

Figure 2: Bid cap imposed

1 http://www.fsa.usda.gov/Internet/FSA_File/julyonepager2012.pdf

2 Practices can vary by region and state. For examples of eligible practice, see the Michigan state NRCS office website for a detailed description of common practices (http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/mi/programs/?cid=nrcs141p2_024527) and the Pennsylvania state NRCS office (http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/pa/programs/?cid=nrcs142p2_018173).

3 Practice caps only apply to continuous signups—since many continuous signup acres enroll under “initiatives” (such as the State Acres for wildlife enhancement initiative) that set aside a fixed number of acres that must use a limited set of conservation practices.

4 CRP’s enabling legislation limits per-county CRP enrollment to be less that 25% of cropland acres, unless specifically waived by USDA.

5 http://www.fsa.usda.gov/Internet/FSA_File/julysummary13.pdf

6 If FSA had perfect precision in soil rental rate information, there would be no need for an auction mechanism at all. In a world with such perfect information FSA could simply offer every farm with qualifying land the exact opportunity cost for that land and enroll acres until acreage goals were fulfilled.

7 There are a variety of reasons for imprecision in the estimate, mostly related to unobserved heterogeneity in land quality or limited number of observations with cash rental agreements. In regions where share rents predominate, imprecise formulae that map share fractions to cash rentals are often used. Bias can occur because bid caps reflect average soil rental rates on all cropland in a county – which may include rents for land that would never be offered to the program (such as between neighbors and family). Bias may also occur because of how rental rate surveys treat hayland.

8 This and the three following cost figures are the result of numerical simulations known as Monte Carlo simulations. We simulate many repetitions of the scenarios explained in the text, with 100 landowners having opportunity costs randomly distributed between $1 and $100. In some cases, random draws result in more low-cost bidders joining the scenario, which results in a low-cost CRP, for example. We report the average outcome for each scenario, i.e. the expected cost of carrying out an auction that matches each scenario explanation.

9 We make the simplifying assumption that all bidders will submit bids equal to their caps. In reality, some bidders may not. Those bidders who are close to the margin – i.e. bidders who are very near to the line demarcating acceptance/rejection – are less likely to submit bids equal to their cap. This behavior does not change the conclusions of the scenarios.

10 If one wanted to favor lower cost bids, one could adjust a reference price auction to favor lower cost bids by increasing the reference price for lower-cost bids; that is, attempt more limited price discrimination. Alternatively, one could also use the reference price as a weight that is combined with the actual bid; this approach allows the purchaser to choose when a relatively low offer (an offer less than its reference price) is preferred to an absolutely low offer (that may be greater than its reference price). For example, if the apple bid had been $0.55 ($0.55/$0.50=1.1) and the orange bid had been $0.60(0.60/$0.75 = 0.8); the orange bid is a relatively low offer (1.1>0.8) but the apple bid is lower than the orange bid ($0.55<$0.60) and so would cost less to buy. A high weight would lead one to choose the orange; a low weight would lead one to choose the apple.

11 Set-asides are also commonly used to ensure that small businesses win some proportion of government contracts, for instance. They might also be used to prevent a market from becoming too concentrated (for example, from preventing Verizon and AT&T from owning all available spectrum, thus promoting competition from new entrants to the wireless communications industry).

12 ERS and University of Maryland researchers (Hellerstein, Higgins and Roberts, 2014) have conducted a number of laboratory experiments that demonstrate the cost effectiveness of quota and reference price auctions.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | %USERNAME% |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-26 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy