YCC_OMB Part A Justification_3 4 2015

YCC_OMB Part A Justification_3 4 2015.docx

Youth Career Connect Impact and Implementation Evaluation

OMB: 1291-0003

OMB Part A Page

Evaluation of Youth CareerConnect

Office of Management and Budget SUPPORTING STATEMENT PART A

The Employment and Training Administration (ETA), U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), is undertaking the Evaluation of Youth CareerConnect (YCC). The overall aims of the evaluation are to determine the extent to which the YCC program improves high school students’ educational and employment outcomes and to assess whether program effectiveness varies by students’ and grantees’ characteristics. The evaluation will be based on a rigorous random assignment design in which program applicants will be randomly assigned to a treatment group (who will be able to receive YCC program services) or a control group (who will not). ETA has contracted with Mathematica Policy Research and its subcontractor, Social Policy Research Associates (SPR), to conduct this evaluation. With this package, clearance is requested for four data collection instruments related to the impact and implementation studies to be conducted as part of the evaluation:

Baseline Information Form (BIF) for parents

Baseline Information Form (BIF) for students

Grantee survey

Site visit protocols

Additionally, a parental or guardian consent form and a student assent form are included in the ROCIS Supplementary Documents.

An addendum to this package, to be submitted at a later date, will request clearance for the follow-up data collection of study participants. The full package for the study is being submitted in two parts because the study schedule requires random assignment and the implementation study to begin before the follow-up instruments are developed and tested.

1. Circumstances necessitating collection of information

Too many American youth leave high school without the skills that employers demand. Of the nearly 47 million jobs predicted to be created by 2018, about one-third will require at least a bachelor’s degree and about 30 percent will require some college or an associate’s degree (Carnevale et al. 2010). To help fill job openings in some of the fastest-growing sectors of the economy, the United States issues hundreds of thousands of nonimmigrant H-1B visas (Ruiz et al. 2012; U.S. Department of State 2011). At the same time, however, youth ages 16 to 19 faced a 23 percent unemployment rate in 2013, compared with a national average of 7 percent, with some subgroups of youth facing even higher rates (U.S. Department of Labor 2014). The occurrence of both high youth unemployment and demand for H-1B visas suggests that youth are leaving high school without the skills needed to obtain necessary credentials or further education. Building youths’ skills and workplace competencies can help address both employers’ needs for high-skilled workers and youths’ high unemployment rates.

To provide high school students with the necessary skills to succeed in the labor market, in spring 2014, DOL awarded a total of $107 million to 24 grantees to implement the YCC program. The program is a high school-based initiative aimed at improving students’ college and career readiness in particular employment sectors. The programs are redesigning the high school experience through partnerships with colleges and employers to provide skill-developing and work-based learning opportunities to help students prepare for jobs in high-demand occupations.

This information correction collection is authorized by the American Competitiveness and Workforce Improvement Act. See 29 U.S.C. 2916a.

a. The YCC program model

The design of the YCC program model drew, in part, from a successful high school redesign effort referred to as the career academy. Career academies embrace three core components: (1) a small learning community that links students and teachers in a structured environment; (2) a college preparatory curriculum based on a career theme that applies academic subjects to labor market contexts and includes work-based learning; and (3) employer, higher education, and community partners (National Career Academy Coalition 2013; Brand 2009; Stern et al. 2000). Both experimental and quasi-experimental evaluations have found that career academies improved academic achievement and reduced high school dropout rates for disadvantaged students (Kemple 2004; Kemple and Snipes 2000; Maxwell and Rubin 2000; Stern et al. 1992). In addition, career academies have been found to increase preparation for and graduation rates from college (Maxwell 2001), as well as wages, hours worked, and employment stability (Kemple 2004; Maxwell and Rubin 2002). Qualitative evidence suggests that work-based learning helped students clarify their career goals (Haimson and Bellotti 2001).

The YCC program model also draws from the success of more recent sector-based initiatives that align occupational training with employers’ needs (Greenstone and Looney 2011; Maguire et al. 2010; Woolsey and Groves 2010), often within the workforce investment system. Using labor market statistics and information collected directly from employers, the programs identify the skills employers need. Training providers and employers work collaboratively to develop training curricula tailored to specific job opportunities. Evaluations of sector-based programs have yielded promising findings. An experimental study of three relatively mature, sector-based programs estimated that adult participants in the programs earned about $4,500 (18 percent) more over the two years after they had enrolled in the study than similar adults who did not participate in the program (Maguire et al. 2010).

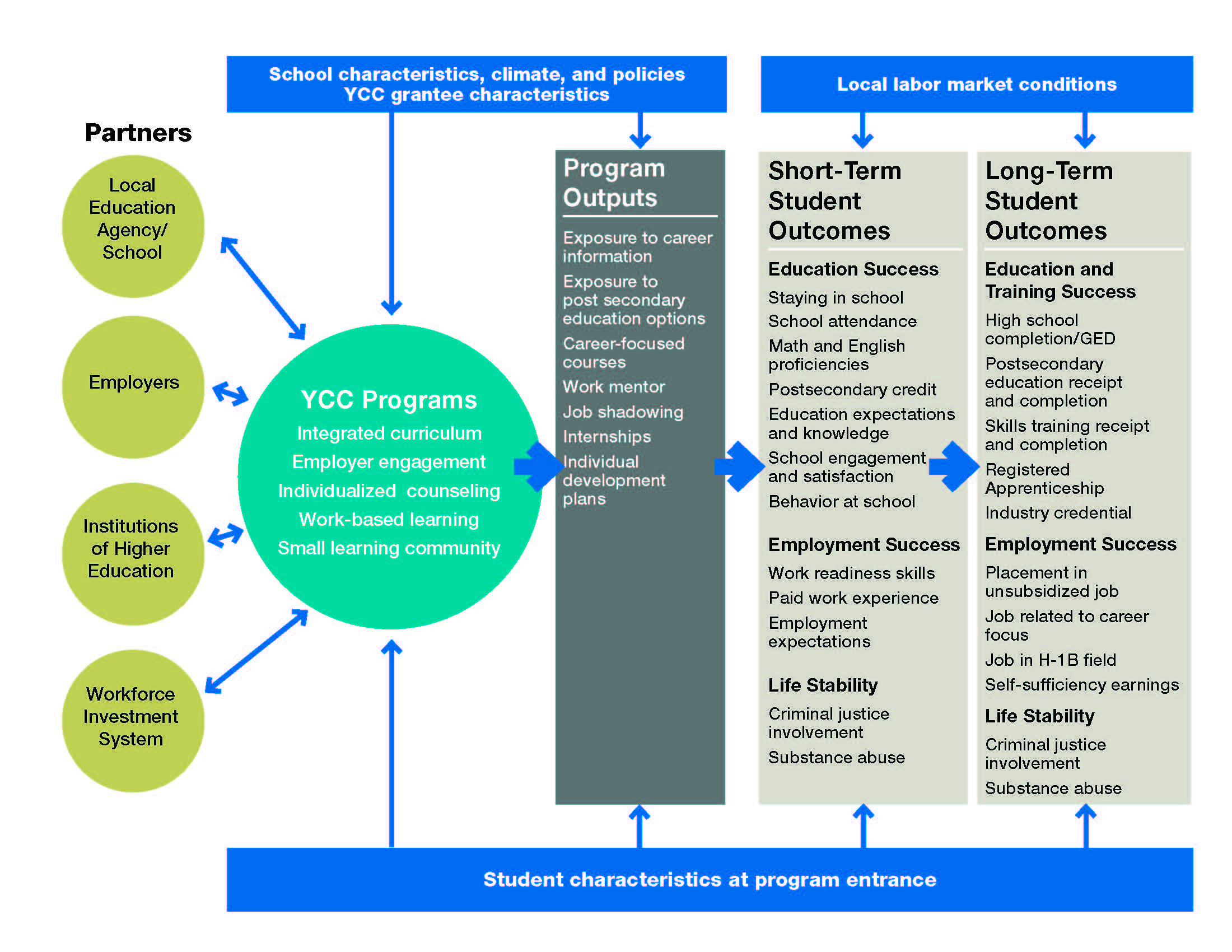

YCC programs blend promising features of both the career academy and sector-based models. The YCC programs will serve high school students and include the key components of career academies. Their design draws on the sector-based models, however, in the importance placed on employers and the workforce investment system. Figure A.1 presents a logic model of the YCC program that will guide the design of the evaluation. The program contains five critical program components: (1) integrated academic and career-focused curricula around one or more industry themes, (2) demonstrated strong partnerships with employers, (3) individualized career and academic counseling that builds career and postsecondary awareness and exploration of opportunities beyond the high school experience, (4) engaged employers that provide work experiences in the workplace, and (5) a small learning community.

Figure A.1. Logic model for YCC programs

GED = general equivalency degree.

b. Overview of Evaluation

Measuring the effectiveness of the DOL-funded YCC programs requires a rigorous evaluation that can address potential biases resulting from fundamental differences between program participants and nonparticipants. ETA has contracted with Mathematica and its subcontractor, SPR, to conduct (1) a random assignment evaluation to measure the impact of the YCC programs and (2) a process study to understand program implementation and help interpret the impact study results.

The evaluation will address three main research questions:

What was the impact of the YCC programs on students’ short-term outcomes? How did participation in a YCC program affect students’ receipt of services and their educational experiences? Did YCC participation improve education, employment, and other outcomes in the three years after the students applied to the program?

How were the YCC programs implemented? How were they designed? Did the grantees implement the YCC core components? What factors influenced implementation? What challenges did programs face in implementation and how were those challenges overcome? What implementation practices appear promising for replication?

Did the effectiveness of YCC programs vary by students’ and grantees’ characteristics? What were the characteristics of the more effective YCC programs?

A rigorous random assignment design in which program applicants will be randomly assigned to a treatment group or a control group will address the first set of questions. Random assignment designs have been broadly accepted as the gold standard for providing reliable impact estimates of interventions. An implementation study of all 24 grantees will address the second set of questions. The third set of questions will be addressed by integrating aspects of the impact and implementation studies and, in doing so, will likely yield important insights into ways to improve programs.

Recognizing the inherent challenges of implementing a random assignment study, our first step in planning the evaluation will be to clarify information in the 24 YCC grant applications to identify sites that appear to be suitable for the study based on their program models and enrollment processes. For the next step, we plan to conduct site visits to suitable sites. The purpose of these visits will be to recruit sites for the proposed random assignment study and to start the process of customizing random assignment procedures to each site. The visits will include on-site, one-day visits to up to 16 promising grantees. Sites will be selected that meet three criteria: (1) enough student demand to generate a control group, (2) feasibility of implementing random assignment procedures, and (3) a significant contrast between the services available to the treatment and control groups.1

Random assignment will be implemented in each selected site that agrees to participate in the study. How random assignment occurs will likely vary by grantee. Some grantees might use a web-based participant tracking system (PTS) developed for the evaluation (which will also be used to collect data for program performance monitoring), whereas others might use existing lotteries and enter information about treatment and control group members into the PTS.2 Baseline data will be collected on treatment and control group students at program application and follow-up data will be collected about two to three years after random assignment.

c. Overview of the data collection

Understanding the effectiveness of the YCC program requires data collection from multiple sources. After obtaining parental/guardian consent forms and student assent forms, the study team will collect a rich set of baseline, service, and outcome data on treatment and control group members to support the impact study; comprehensive data will also be collected to support the implementation study. The data covered by this clearance includes the collection of baseline and contact information for students and parents from the BIFs. These baseline data will enable the team to describe the characteristics of study participants at the time of random assignment, ensure that random assignment was conducted properly, and conduct baseline equivalency analyses. Baseline data will also be used to create subgroups for the analysis, match students to school records data, improve the precision of the impact estimates, and assess and correct for survey nonresponse. The contact information will be used to locate individuals for a follow-up survey.

The implementation analysis data covered by this clearance will consist of (1) a grantee survey administered twice to all 24 YCC grantees and (2) three rounds of visits to sites selected for the impact study. Together, these data will be needed to describe the YCC programs and the successes and challenges they face; highlight promising or best practices found in specific programs; and identify a set of lessons learned with regard to implementing, supporting, and funding YCC programs. Data from the implementation analysis will support findings from the impact analysis and will enable the study team to create subgroups to examine the association between the variation in program impacts and key measures of program features and practices.

Data on service receipt and study outcomes will be part of a future clearance package. Self-reported information on the receipt of YCC-related services (collected consistently for both the treatment and control groups) will be used to estimate the impact of YCC on the number of career-focused courses completed; the receipt of work-based activities in high school (such as job shadowing, mentoring, internships, participation in training programs, and apprenticeships); and the receipt of career skill-building services (such as resume writing, interviewing, team building, and information on postsecondary schools). This information will be used to assess the intensity of services received by the treatment group and to assess the study counterfactual as measured by the services received by the control group.

Key follow-up outcomes will be constructed using school records and student survey data collected in the two to three years after random assignment. These outcomes will include measures of (1) education success (school and program retention, attendance and behavior, school engagement and satisfaction, test scores and proficiency, postsecondary credits and the number of Advanced Placement classes, and educational expectations); (2) employment success (such as work-readiness skills, work experience in paid and unpaid jobs, employment expectations, and knowledge of career options); (3) life stability (such as involvement with the criminal justice system and drug use); and (4) the school climate.

2. How, by whom, and for what purpose the information is to be used

Clearance is currently being requested for data collection that will be used to perform and monitor random assignment and to conduct the implementation study. Each form is described below, along with how, by whom, and for what purpose the collected information will be used. A subsequent addendum to this package will include a request for clearance for additional data collection instruments for follow-up data collection on sample members.

The parent and student BIFs

Before random assignment, contact and demographic information will be collected on all youth and parents who consent to be part of the study. Baseline data and contact information are needed for multiple purposes, including (1) conducting and monitoring random assignment, (2) locating participants for follow-up data collection, (3) defining policy-relevant subgroups for impact estimates, (4) increasing the precision of impact estimates by including baseline covariates in the regression models that are predictive of the outcome measures, and (5) adjusting for nonresponse to the follow-up data collection using baseline data that are predictive of survey nonresponse.

The student BIF will provide a snapshot of information about the students—their school experiences, school engagement, expectations for education, and activities both in and outside of school—at the time the students apply for the program. The parent BIF will collect information on a student’s household that is not available from the student, and information on the reasons the parent wants his or her child to enroll in the YCC program. Both the parent and student BIFs will collect multiple forms of contact information that will be critical to the success of the follow-up data collection.

The parent and student BIFs are presented in Attachments A and B respectively. Parents and students will be asked to complete their respective BIFs as part of the YCC application process. Baseline data elements to be collected include the following:

Identifying information. These data include the student’s and their parent’s name; address; telephone number (home, cell, or other); and email address. This information will be entered into the PTS by program staff to ensure that each individual is randomly assigned only once and that control group members do not receive barred YCC services. In addition, parents will be asked to provide students’ Social Security numbers on the consent form, if available. These data will also be necessary for tracking and locating students for the follow-up data collection and to ensure that students can be accurately matched to administrative records data.

Demographic characteristics and reasons for applying to YCC. These data items mostly come from the parent BIF and include household structure, household education level, parent/guardian employment status, household income sources, primary language spoken at home, and the number of schools the child has attended since 1st grade (excluding those from the natural promotion through schools). The parent BIF also includes reasons their children want to join the YCC program. The student BIF obtains information on whether the student has any children.

Education expectations. Included in this category are the following items in the student BIF: a measure of the importance of grades and highest degree expected to complete. The parent BIF asks about degree expectations for their children and whether a parent has talked to the student about education after high school.

School engagement, satisfaction, and behavior. The data items in the student BIF include measures of the student’s participation in school-organized extracurricular activities, satisfaction with school, school behavior, hours spent doing homework, and a measure of motivation.

Employment experience. The student BIF collects information on the student’s work experience at any paid jobs.

Involvement with the criminal justice system and drug and alcohol use. The student BIF collects information on the number of times the student was ever arrested and whether the student used alcohol and drugs in the prior month or ever.

b. Grantee survey

As part of the implementation study, a grantee survey will be administered to all 24 YCC grantees in spring 2015 and again in spring 2017 to collect information on service delivery models, staffing, staff development, partnerships, and implementation of the core program elements. The survey will be sent both as a writeable portable document format (PDF) file (via email) and mailed in hard copy. The data collected from these surveys will be used to describe all the YCC programs and the successes and challenges they face; highlight promising or best practices found in specific programs; and identify a set of lessons learned with regard to implementing, supporting, and funding YCC programs. These data will also provide context for helping the team to interpret the impact evaluation findings for the sites participating in the impact study.

The grantee survey in Attachment C will be used to collect information in 10 topical areas related to the program’s design and service delivery model:

Organization and administrative structure, including the number of programs associated with the YCC grant, grades covered; program length, prior experience offering YCC-related services, and funding

Program partners, including institutions of higher education, employers, supportive service organizations and Workforce Investment Boards

Program features, including career focuses; recruitment methods; application processes; and service offerings (such as college visits, information on postsecondary schools and financing, job shadowing, mentoring, and internships, and job search and other workforce preparation activities)

Curriculum, including types of standards and assessments, academic courses, career and technical courses, and curriculum integration

Employer engagement, including program development, support, and workforce preparation activities provided by employer partners

Career and academic counseling, including the availability of dedicated counselors and coaches, the frequency of students’ contacts with counselors, and counselors’ roles (such as identifying education and career goals and ways a counselor helps students meet these goals)

Work-based learning, including the types of skills YCC students gain from program participation (such as technical skills and an understanding of workplace behavioral expectations, workplace culture and communication, and workplace performance expectations)

Support services, including academic, career preparatory, financial, and health services offered by the program

Small learning communities, including specific courses targeted to YCC students, project-based learning activities, and the availability of physical space devoted to the YCC program

Professional development, including the number of hours provided to YCC staff and types of professional development

c. Site visit protocols

The study team will conduct three rounds of visits to the sites included in the impact study. The first visit for the in-depth implementation analysis will be a three-day visit in spring 2015, shortly after the grantees have completed surveys. It will provide site visitors with the opportunity to learn in detail about how grantees have planned, designed, and implemented their programs; the process for mobilizing key partners; early implementation activities with the first cohort of students; and challenges encountered and solutions identified, especially those related to program start-up. The second, a two-day visit, will be scheduled for spring 2016 and will enable site visitors to learn how program service models and partnerships have evolved over time, how the subsequent cohort has been served, how students who have been enrolled for multiple years are faring, and challenges grantees have encountered and the solutions identified to overcome those challenges. The third visit, for two days, will be scheduled for winter 2018 and will enable site visitors to document how programs matured over time and to look more closely at program sustainability.

Site visit protocols and topic guides are presented in Attachment D. They will help ensure that site visitors focus their data collection to systematically collect information to address the implementation study research questions, although they will be flexible enough that site visitors can pursue more open-ended discussions with respondents when needed. The protocols and topic guides will also promote uniform data collection across programs. Site visitors will use the topic guides to conduct semistructured interviews and focus groups during the visits. The site visit protocols will be customized to the structure of each organization.

Site visitors will use these interviews to capture the perspectives of a wide variety of stakeholders, to document differences and similarities between programs, and to understand the unique contexts in which each program operates. Respondents will include program administrators and staff, key partners, employers, and students.

Site visitors will also gather and review two types of program documents during each visit: students’ individual development plans (IDPs) and program design documents. At the start of each visit, site visitors will request IDPs of the selected students and review and record specific items from each plan. This review will provide a foundation for understanding the nature of the individualized counseling program component. Site visitors will discuss each case with the appropriate staff member to understand the service planning process and how staff counsel youth for academic and career exploration. Site visitors will also collect relevant program materials that provide details not easily gathered during interviews and focus groups, such as course syllabi, lesson plans, tests, homework assignments class schedules, student handbooks, and blank IDPs. Such materials will help us to assess the degree to which programs incorporate key program elements—such as the integration of academic and career-focused learning—into everyday operations.

3. Use of technology to reduce burden

The data collection efforts will use advanced technology to reduce burden on program participants and on staff at participating agencies. Consent forms and BIFs will be integrated into existing electronic application processes whenever possible. When sites use paper applications, we will supply sites with hard copies of the consent forms and BIFs to make it easier on sites, parents, and students to complete the application and BIFs in one sitting. Paper copies of the consent forms and BIFs will be sent to the evaluator, which will use trained data entry staff to compile the data and create electronic databases.

4. Efforts to avoid duplication of effort

To minimize duplicate data collection, the parent and student BIFs, as well as the grantee survey, have been reduced to only items necessary to the evaluation. Only a limited amount of descriptive information is expected to be available from the data collected electronically by programs as part of their normal intake procedures. These existing data likely do not contain all the baseline characteristics of youth necessary nor will they be consistent across sites. If discussions with sites lead to a finding that all sites collect an item on the parent and student BIFs, or on the grantee survey, in a consistent manner, and this information is not necessary to conduct random assignment, the item can be dropped.

5. Methods of minimizing burden on small entities

The data collection effort does not involve small businesses or other small entities.

6. Consequences of not collecting data

Without collecting baseline information on study participants, the study’s ability to implement random assignment correctly and monitor adherence to random assignment procedures would be severely limited. The lack of baseline information would limit the ability to describe the population of YCC students and would limit the analysis of impacts of the program on subgroups, hence limiting the ability to determine the groups for which the program is most effective. Without baseline data, impact estimates would be less precise (so that small impacts would be less likely to be detected), and adjustments for nonresponse to the follow-up surveys would have to be based on less-detailed administrative data.

Without collecting detailed contact information for study participants, the study’s ability to track participants over the follow-up period would be limited. This would likely lead to a higher nonresponse rate and, thus, a greater risk that the quality of survey data is compromised. That in turn could lead to compromised impact estimates.

Without collecting the information specified in the grantee survey and site visit protocols, an implementation analysis of the YCC program could not occur. This would prevent information being provided to policymakers about the context in which programs operate, any operational challenges faced by programs, and how the programs evolve over time. Lack of implementation data would also prevent an examination of how the impacts of the services vary by how and the context in which they are implemented. Without the site visits, there is also a greater chance that any deviations from study procedures would go undetected.

7. Special circumstances

No special circumstances are involved with the collection of information.

8. Federal Register announcement and consultation

a. Federal Register announcement

A 60-day notice to solicit public comments was published in the Federal Register, Volume 79 Issue No. 201, page 62467 on October 17, 2014. No comments were received.

b. Consultations outside the agency

We have not consulted any experts who are not directly involved in the study regarding the subject of this clearance. We expect to consult with additional experts for other aspects of the evaluation design and impact evaluation.

c. Unresolved issues

There are no unresolved issues.

9. Payment or gift to respondents

There are no payments to respondents. Tasks and activities conducted by program and partner staff are expected to be carried out in the course of their employment, and no additional compensation will be provided outside of their normal pay. Sample members will not be compensated for completing study enrollment forms. Sample members will be compensated at follow-up, which will be described in a future submission.

10. Privacy of the data

The study is being conducted in accordance with all relevant regulations and requirements, including the Privacy Act of 1974 (5 U.S.C. 552a); the Privacy Act Regulations (34 CFR Part 5b); and the Freedom of Information Act (5 CFR 552) and related regulations (41 CFR Part 1-1, 45 CFR Part 5b, and 40 CFR 44502).

Before random assignment, program participants and their parents will receive information about the study’s intent to keep information private to the extent permitted by law; the consent form that participants will be asked to read and sign before being randomly assigned to a research group will include this privacy information (see Attachment E). The information will introduce the evaluators, explain random assignment and the research groups, explain that the study participants will be asked to participate in voluntary surveys, and inform participants that administrative records will be released to the research team. Participants will be told that all information provided will be kept private and used for research purposes only. Further, they will be assured that they will not be identified by name or in any way that could identify them in reports or communications with DOL.

11. Additional justification for sensitive questions

The parent and student BIFs will collect background information on students who have consented to participate in this evaluation. Information on date of birth, Social Security number, address, and telephone numbers is needed to identify and contact sample members and to ensure that random assignment is conducted correctly. The BIFs will also collect information on characteristics of sample members and their parents, such as their education level, which will be used to enhance the impact estimates. This type of information is routinely collected as part of enrollment in most programs and is, therefore, not considered sensitive.

The student BIF includes questions that some respondents might find sensitive. These questions ask about delinquent activities, including arrests and drug use. Collection of this information, though sensitive in nature, is critical for the evaluation and cannot be obtained through other sources. The extent of prior involvement with the criminal justice system will be an important characteristic for describing our sample members and will serve as a means to form key subgroups for our impact analysis. We have included similar questions in past studies without any evidence of significant harm.

As described earlier, all sample members will be provided with assurances of confidentiality before random assignment and the completion of study enrollment forms. Not all data items have to be completed. All data will be held in the strictest confidence and reported in aggregate, summary format, eliminating the possibility of individual identification.

12. Estimates of hours burden

In Table A.1, we describe our assumptions about the total number of responses expected, the average hours of burden per respondent, and the total burden hours estimated for the student and parent BIFs, grantee survey, and three rounds of site visits. We have provided the average burden for the grantee survey, but estimate that the actual burden time per response will vary based on the complexity of the grantee’s program structure. We anticipate that grantees with more complex programs will average approximately 90 minutes per response, whereas other grantees will average approximately 30 minutes per response. The estimate of burden on students is 1,580 hours (1,400 hours for the baseline survey and 180 hours for site visits) ($11,455); 1,267 hours on parents ($21,369); 35 hours on grantees ($1,535); and 674 hours on program and partner staff ($29,357). In total, the burden is 3,556 hours ($63,717). The annual burden hours on students is 526.67 hours (466.67 hours for the baseline and 60 hours for site visits) ($3,818.33); 422.33 hours on parents ($7,123); 11.67 hours on grantees ($511); and 224.67 hours on program and partner staff ($9,785.99). In total, the annual burden is 1,185 hours ($21,239).

Table A.1. Burden associated with the baseline enrollment forms, grantee surveys, and site visits

Respondents |

Total number of respondents over entire evaluation |

Annual number of responses |

Number of responses per respondent |

Average burden time per response |

Total burden hours over entire evaluation |

Annual burden hours |

Time value |

Annual monetized burden hours |

|

Baseline information forms |

|||||||||

Students (including assent) |

4,000a |

1,333.33 |

1 |

21 minutes |

1,400 |

466.67 |

$7.25c |

$10,150 |

$3,383.33 |

Parents (including consent) |

4,000a |

1,333.33 |

1 |

19 minutes |

1,267 |

422.33 |

$16.87c |

$21,369 |

$7,123 |

YCC staff (Student BIF) |

50b |

666.67 |

40 |

5 minutes |

167 |

55.67 |

$43.60c |

$7,267 |

$2,422.33 |

YCC staff (Parent BIF) |

50b |

666.67 |

40 |

5 minutes |

167 |

55.67 |

$43.60c |

$7,267 |

$2,422.33 |

Grantee survey and site visits |

|||||||||

Grantee survey |

24 |

16 |

2 |

44 minutes |

35 |

11.67 |

$43.60 |

$1,535 |

$511 |

Site visits |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Staff |

170d |

170 |

3 |

40 minutes |

340 |

113.33 |

$43.60 |

$14,824 |

$4941.33 |

Students |

60d |

60 |

3 |

60 minutes |

180 |

60 |

$7.25 |

$1,305 |

$435 |

Total |

8354 |

4246 |

|

|

3,556 |

1,186 |

|

$63,717 |

$21,239 |

a The figures correspond to 200 treatment and 200 control group students in each of the 10 study sites.

b The figures assume five staff members per site.

c The hourly wage of $7.25 is the federal minimum wage (effective July 24, 2009) http://www.dol.gov/dol/topic/wages/minimumwage.htm , $16.87 is the May 2013 median wage across all occupations in the United States http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm , and $43.60 is based on the May 2013 Bureau of Labor Statistics hourly and weekly earnings of “Education Administrators: Elementary and Secondary” found at http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes119032.htm .

d Assumes 17 staff and 6 students are interviewed at each site.

13. Estimate of total annual cost burden to respondents or record-keepers

There are no direct costs to respondents, and they will incur no start-up or ongoing financial costs. The cost to respondents involves solely the time involved for the interviews and completing the BIFs. The costs are captured in the burden estimates in Table A.1.

14. Estimates of annualized cost to the federal government

The total annualized cost to the federal government is $39,341.40. Costs result from the following three categories:

The estimated cost to the federal government for the contractor to carry out this study is $46,053 for baseline data collection, $1,535 for two rounds of the grantee survey, and $16,129 for three rounds of site visits. Annualized, this comes to $21,239. ($46,053 + $1,535 + $16,129)/3 = $21,239.

The annual cost borne by DOL for federal technical staff to oversee the contract is estimated to be $18102.40. We expect the annual level of effort to perform these duties will require 200 hours for one Washington D.C. based Federal GS 14 step 4 employee earning $56.57 per hour. (See Office of Personnel Management 2015 Hourly Salary Table at http://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/pay-leave/salaries-wages/salary-tables/pdf/2015/DCB_h.pdf ). To account for fringe benefits and other overhead costs the agency has applied multiplication factor of 1.6 200 hours x $56.56.57 x 1.6 = $18,102.

TOTAL FEDERAL COST $39,341. $21,239 + $18,102 = $39,341.

15. Reasons for program changes or adjustments

This is a new information collection.

16. Tabulation, publication plans, and time schedules

This data collection will contribute to interim, final, and short reports on impact and implementation. The final report will be available in early 2019.

17. Approval not to display the expiration date for OMB approval

The expiration date for Office of Management and Budget (OMB) approval will be displayed.

18. Exception to the certification statement

No exceptions to the certification statement are requested or required.

REFERENCES

Brand, Betsy. “High School Career Academies: A 40-Year Proven Model for Improving College and Career Readiness.” American Youth Policy Forum, November 2009.

Carnevale, Anthony P., Nicole Smith, and Jeff Strohl. “Help Wanted: Projections of Jobs and Education Requirement Through 2018.” Washington, DC: Center for Education and the Workforce, Georgetown University, July 2010.

Greenstone, Michael, and Adam Looney. “Building America’s Job Skills with Effective Workforce Programs: A Training Strategy to Raise Wages and Increase Work Opportunities.” Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, November 2011. Available at http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2011/11/training%20greenstone%20looney/11_training_greenstone_looney.pdf.

Haimson, Joshua, and Jeanne Bellotti. “Schooling in the Workplace: Increasing the Scale and Quality of Work-Based Learning.” Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, January 2001. Available at http://mathematica-mpr.com/publications/PDFs/schooling.pdf.

Kemple, James J. “Impacts on Labor Market Outcomes and Educational Attainment.” MDRC, June 2004. Available at http://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/full_45.pdf.

Kemple, James J., and Jason Snipes. “Impacts on Students’ Engagement and Performance in High School.” [add city]: MDRC, 2000. Available at http://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/full_45.pdf.

Maguire, Sheila, Joshua Freely, Carol Clymer, Maureen Conway, and Deena Schwartz. “Tuning in to Local Labor Markets: Findings from the Sectoral Employment Impact Study.” Philadelphia, PA: Public/Private Ventures, 2010. Available at https://www.nationalserviceresources.gov/files/m4018-tuning-in-to-local-labor-markets.pdf.

Maxwell, Nan L. “Step-to-College: Moving from the High School Career Academy Through the Four-Year University.” Evaluation Review, vol. 25, no. 6, December 2001, pp. 619–654.

Maxwell, Nan L., and Victor Rubin. High School Career Academies: Pathways to Educational Reform in Urban Schools? Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2000.

Maxwell, Nan L., and Victor Rubin. “High School Career Academies and Post-Secondary Outcomes.” Economics of Education Review, vol. 21, no. 2, April 2002, pp. 137–152.

National Career Academy Coalition. “National Standards of Practice for Career Academies.” National Career Academy Coalition, April 2013. Available at http://www.ncacinc.com/sites/default/files/media/documents/nsop_with_cover.pdf.

Ruiz, Neil G., Jill H. Wilson, and Shyamali Choudury. “The Search for Skills: Demand for H-1B Immigrant Workers in U.S. Metropolitan Areas.” Washington, DC: Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings Institution, July 2012.

Stern, David, Marilyn Raby, and Charles Dayton. Career Academies: Partnerships for Reconstructing American High School. Jossey-Bass, 1992.

Stern, David, Charles Dayton, and Marilyn Raby. “Career Academies: Building Blocks for Reconstructing American High Schools.” Career Academy Support Network, October 2000. Available at http://casn.berkeley.edu/resource_files/bulding_blocks.pdf.

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey: Household Annual Average, 2013.” Washington, DC: DOL, February 26, 2014. Available at http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat03.htm.

U.S. Department of State. “Nonimmigrant Visa Issuances by Visa Class and Nationality, FY 2011.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State, 2011. Available at http://travel.state.gov/visa/statistics/nivstats/nivstats_4582.html.

Woolsey, Lindsey, and Garrett Groves. “State Sector Strategies Coming of Age: Implications for State Workforce Policymakers.” Washington, DC: National’s Governors Association, 2010. Available at http://www.woolseygroup.com/uploads/NGA_Sector_Strategies_Coming_of_Age_2013.pdf

1 A separate Office of Management and Budget (OMB) clearance package was submitted and approved (under OMB Number 1205-0436) for these site visits.

2 A separate OMB clearance package was submitted and is under review for the PTS for performance reporting.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | PBurkander |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-25 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy