Literature Review

Working Women's Survey Lit Review 3_11_2014.docx

Survey of Working Women

Literature Review

OMB: 1290-0011

WOMEN’S BUREAU: U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR |

WORKING WOMEN COUNT: REVIEW OF LITERATURE |

|

|

March 11, 2014 |

Table of Contents

Multiple factors of discrimination 3

Solutions provided by researchers. 3

Organizational research and gaps 3

Women and Gender Equality in the Workplace 6

The Current State of Research 20

Key Findings

Women in the workplace are discrimanted against, not only by gender, but by age, race, motherhood, and job type

Although gender is a common source of workplace discrimination for all women, it can be further compounded when paired with other elements of bias such as age, minority status, and occupation. These multiple factors can further burden women at work, causing them to face lower pay and promotion potential. However, there is little research looking at how these factors work together against women.

Many studies fail to take into account multiple biases and how they interact. Rather, many studies only focus on a single level of discrimination and do not accurately depict the hardships that women face on the job. For example, a young Latina worker may face discrimination by age, race, and gender simultaneously.

many researchers provide solutions, including flexible working hours

In addition to highlighting the problems facing working women today, researchers are increasingly focused on how to address them. Many recent publications suggest several options for addressing these issues including organizational, legal, and cultural shifts. Uniquely, flexible working schedules and productivity options are cited by several studies as an effective way of allowing women to maintain progress and seniority at work, while still taking care of children.

Multiple organizations are producing Research on working women, but significant gaps still remain

Given the growing influence of women in the workplace, with rising participation rates and a narrowing salary gap, research in gender and employment issues has come from a multitude of sources including government reports, academia, and nonprofits. Private businesses and consulting groups have also produced large-scale, global reports looking at employed women. However, even with this amount of coverage, gaps still exist in the research. Many publications are based on small scale, one-time studies. Many also only collected quantitative data, without fully capturing the “why” behind women’s decisions in regards to work. Greater longitudinal and qualitative studies can help remedy these issues.

Introduction

Women’s studies as a discipline has grown substantially since coming to prominence in the 1970s (although a large body of important work exists from much earlier). During this period, women began expanding into the workplace at an increasingly rapid pace, breaking down many of the barriers that had previously prevented their inclusion. Today, the study of women in the workplace is an advanced and growing field, with many specialties and sub-fields growing out of it. Not coincidentally, many of the most researched and discussed areas in women’s employment are also those barriers that women face most in the workplace: discrimination by gender, age, race, and job type all feature prominently in current research.

To more completely understand advancements in this research as part of the Working Women Count study, the Women’s Bureau has conducted a study of the literature on women’s employment. (Throughout this report, past research for this major study will be referred to in past tense.) This literature review seeks to answer what are the main issues facing women in the workplace in the 21st century and what body of academic research currently exists on women in the workplace. This study examines a sample of the published work regarding women in the workplace and attempts to highlight major themes and trends in the field.

Methodology

A broad range of research articles, journals, interviews, and books were consulted and evaluated for this study. To focus on the most recent developments, materials were primarily restricted to post-1990 findings, although earlier legal or reference documents (such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964) were included when necessary for context. Searches were conducted through academic databases (EBSCO, WALDO) as well as open-source methods, such as Google Scholar. Search results were limited to English, and were primarily focused on the U.S., although global studies were included if they encompassed the U.S. in their results, or provided a novel finding in terms of research or methodology.

Literature Review Sample Keyword Search Terms

Working women |

Gender equality |

Momism |

FMLA |

Glass ceiling/Sticky floor |

Occupational dissimilarity |

Ageism |

Race and gender in the workplace |

Women in non-traditional jobs |

Limitations

This literature review seeks to provide a brief overview of the existing literature and studies on women in the workplace. However, given the scope and breadth of the publications on the subject, some articles may have been omitted. This study primarily focused on the status of working women within the U.S., so many worthwhile studies from outside of the U.S. were not included. This report also used articles solely written in English so foreign language documents were excluded. Likewise, some articles requiring paid access that were unavailable through interlibrary loan may have also been omitted.

Discussion

Introduction

Limitations placed on female workers in terms of pay, benefits, status, and fairness have long characterized the role of women in the workplace. While women have achieved enormous progress over the past 50 years in gaining equal opportunities, many women entering the workforce still face difficulties.

Although women have made great strides in overcoming obstacles and gaining new levels of responsibility and status, these triumphs still represent the exception rather than the rule. Consider how professional women are viewed globally. Of the 195 countries in the world, just 17 have a female leader. Worldwide, 80% of members of parliament are men, and 18% of U.S. Congressional representatives are women. In the business world, things aren’t much better. Of the Fortune 500 CEOs, 21 are women, and women make up 17% of corporate board members.1

However, the prejudices of the past are beginning to come into conflict with the reality of the present. Today’s women are coming into the workforce better educated than men, with 38% of 25- to 32-year-old women holding a four-year college degree compared with 31% of men.2 This increases even further in graduate education as women now earn 60% of all master’s degrees in the U.S.3 Although women still lag behind men in the workforce, they have closed the gap in recent years, especially following the 2008 financial crisis. In the wake of the recession, 67.5 million women are working in the U.S., the highest proportion ever, while working men remain at 69 million employed, never having recovered from their peak in 2007.4 Women are also entering white-collar positions at a higher rate (53%) than men (47%).5

This report will examine the issues facing women at work, and the specific instances of discrimination that they face in terms of pregnancy, motherhood, age, race, and job type. The current state of research will be explored, as well as gaps that currently exist in the data.

Women and gender equality in the workplace

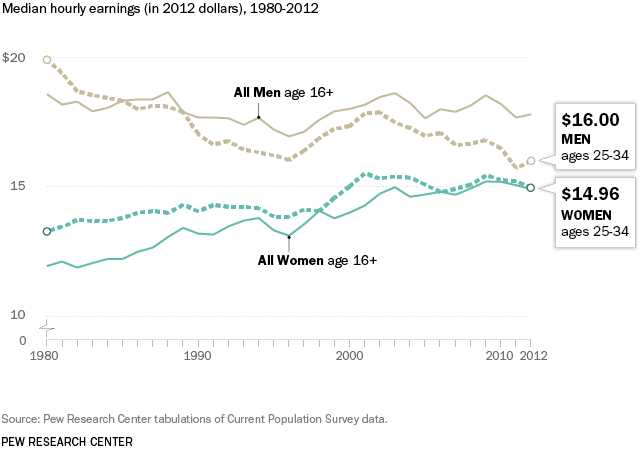

Among the most commonly noted, and thus most often researched, barrier for women is the pay gap between genders. Although the gap has narrowed in recent years, differences remain. According to the Department of Labor (DoL) in 2010, the median weekly earnings of full-time men was $824, while women earned 81% of this at $669.6 However, recent trends show optimism as the gap is closing, particularly among young workers. A 2012 Pew study found that among 25- to 34-year-olds, men earned $16/hour in median wages, while women earned $14.96/hour, just 6% less.7 However, this movement appears to be due as much to men’s wages falling as much as women’s wages rising.

Figure 1: Median earnings by gender

Although important, pay equality is not the only differentiator in how men and women are successful in the workplace. A study conducted among MBA graduates found that the budgets of men’s projects were generally twice as large as women’s and had three times as many people working on them.8 Moreover, men’s projects were noted to have a high level of executive (C-suite) visibility (35% for men vs. 26% for women), and involved a significantly higher level of risk.

A shortage of mentors may also hold women back in the professional ranks. Mentors (people providing advice and guidance) and sponsors (people who will advocate and vouch for them) for women are not found at the same rate as men. One study found that employees (either men or women) with sponsors were more likely to ask for “stretch” assignments and pay raises at work, than those who did not have sponsors.9 Furthermore, those who were satisfied with the sponsorship they had received were more likely to have direct reports, more likely to work on a project with a budget of $10 million or more, and more likely to work on projects leading to “turn-around” outcomes.10 While sponsors have been shown to be equally helpful in the development and advancement of both men and women, they are not equally distributed. A recent study through the Harvard Business School (HBS) found that men are more likely to be sponsored and more satisfied with their rates of advancement (once sponsored) than women.11

Pregnancy

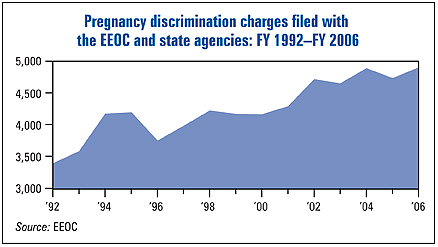

Instances of pregnancy discrimination, that of women who are or have recently been pregnant, in the workplace has become a major type of discrimination in the country, surpassing sexual harassment and sex discrimination complaints. According to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), complaints of pregnancy discrimination jumped 39% from 1992 to 2003.12

Figure 2: Pregnancy discrimination on the rise in U.S.

Research regarding pregnant women in the workplace has been consistently produced over the past few decades, following many of the laws passed to protect these women such as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (1978). Perhaps the most effective measure against pregnancy discrimination has been the 1993 passage of the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA). Under FMLA employers cannot13:

Deny women a job offer based solely on their pregnancy.

Use pregnancy as an excuse to test workers, or force them to meet special conditions that are not required of other employees.

Demand a doctor’s note to return to work if not required of other employees.

Refuse to grant pregnant women on leave the ability to accrue seniority, vacation, pay increases, and disability benefits in the same way as those who are on leave for reasons other than pregnancy.

Studies have shown that this discrimination can impact beyond current or recently pregnant women to those who might become pregnant in the future. Young women of child-bearing age have been shown to be discriminated against in job interviews because employers are unwilling to take the “risk” that they may become pregnant and would then be forced to grant them leave. A study of recruiters found that 75% had been asked by clients to avoid hiring pregnant women or those who were of child-bearing age.14 Many of the recruiters (44%) felt that this attitude was most prevalent among smaller businesses and organizations.

Gaps in fmla

However, even as the passage of FMLA has helped to promote workplace equality for pregnant women, several authors believe that they are not nearly specific enough to fully protect expectant mothers. To qualify for the protections of the FMLA, a worker must work for an employer for at least 1,250 hours for the year before the leave is granted. This effectively eliminates coverage for all part-time workers, many of whom are women. Moreover, a workplace must have 50 or more employees for FMLA to take effect. Some studies find that half of all workers in “very small firms” (10 or fewer employees) are women, meaning that a substantial number of women working in the U.S. are not afforded the rights and protections they need under FMLA.15 One study found that 40% of private-sector workers cannot utilize FMLA because they work for companies that have fewer than 50 employees.16

Even among working women who are covered by FMLA, the law may fail to adequately meet their needs. Some researchers cite that it is because these laws treat men and women as indistinguishable equals that they fail to provide women with equal opportunities in the workplace, since women are anatomically unique from men in that they are the only ones capable of giving birth. As such, the comparator approach taken by the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA), requiring pregnant workers to prove they received inferior treatment than a similar non-pregnant worker, fails to acknowledge that only women will ever become pregnant, and thus sets an unfair standard of comparing pregnant women against non-pregnant men. Moreover, the PDA is also limited in terms of providing protections for “pregnancy-related” conditions (such as breastfeeding and fertility treatments) as these fall outside the scope of PDA.17

Additionally, although FMLA is a federal law, states may take additional measures to support working families. However, these laws differ on a state-by-state basis such that some states, like Alabama, only provide the minimum leave to workers covered by the federal FMLA, while others, like Connecticut, are much more generous in their coverage. As a result, working women nationwide are unequally supported in terms of leave.18 Moreover, states themselves can largely avoid any negative consequences related to infractions of FMLA for their workers. In a 2012 ruling, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that states are immune from lawsuits related to FMLA violations by the state.19

Finally, FMLA also only provides leave in terms of taking care of children and immediate family members. Women who are caretakers for extended family, including grandparents, cannot be granted leave under FMLA provisions.20

working mothers

In addition to the bias against working women who are pregnant, women with children face discrimination in the workplace including lower wages and less opportunity for advancement. This “motherhood penalty” is one of the most studied phenomena in gender research, with many sources measuring the burden that having children places on women. This increases the gap in the already disparate level of wages between men and women, imposing a penalty of between 10%-18% on women per child.21 The imposition of this penalty is seen by researchers to be the result of a variety of factors. Employers may falsely perceive mothers to be less committed to their jobs, and less willing to put in long hours. Employer discrimination may also contribute to paying mothers less, and may even prevent them from being hired to begin with. Finally, some studies have shown that mothers, acting as the primary caregivers, often experience more breaks and interruptions in school and work, which further diminish their earnings.22

A 2013 HBS study had participants play the role of a hiring manager and consider the resumes of job applicants who were identical, except that some indicated that the applicant was a parent. The results found that women with children were penalized and were much less likely to be hired. Men, on the other hand, suffered no penalty at all. Moreover, when mothers were selected for hire, they were started at $11,000 less than women without children. Again, fathers did not receive any disadvantageous treatment for having children.23

Several articles have also looked at ways to overcome the motherhood penalty. In several similar studies, women were able to overcome the penalty by demonstrating a strong devotion and commitment to their work. Men faced no penalty and therefore did not have to go to any extra effort to show their commitment. In one study, equally qualified female applicants who were noted to be “devoted to their family” were rated lower by simulated interviewers than all other candidates in terms of hiring. However, if the women were noted to be “devoted to their work” they were rated as highly as work-devoted fathers.24 This finding was confirmed in a follow-up experiment to the HBS study, which again found that mothers were seen as less hirable than fathers, or those without children. But, the study also found that if the “hiring managers” were given sample performance reviews that showed mothers to have high levels of commitment and performance at their previous jobs, the motherhood penalty could be diminished. Although these findings are useful, it remains unclear to what lengths working women should go to overcome the motherhood penalty. Certainly, it is beneficial for working mothers to signal their commitment and advance in their careers to serve as an example for others, but this will not change the underlying bias that is imposing this extra burden on women to begin with.

Shelley Correll of Stanford sees changes within organizations as partially helpful, but notes that only a major cultural shift in terms of attitudes toward working hours and work/life balance can truly diminish the penalty against mothers.25 She goes on to note that the most effective way to equalize the playing field may be through more flexibility in terms of scheduling and working hours, reducing work/family conflict for women as well as men. The focus on flexible work hours and new ways of measuring productivity, such as the Results-Oriented Work Environment (ROWE) pioneered at Best Buy, are detailed in a number of qualitative and quantitative studies on working women.26 New research bolsters by these findings, with one studying finding that greater flexibility with regards to working hours are the “last chapter” needed to close the pay gap between men and women, stating, “The last chapter must be concerned with how worker time is allocated, used, and remunerated and it must involve a reduction in the dependence of remuneration on particular segments of time.”27

While discrimination toward working women is a global phenomenon, the U.S. stands out as deficient in terms of providing assistance for these mothers. Of all the industrialized nations, the U.S. is the only one that does not have a national policy on paid maternal leave.28 This comes at a time when working mothers are the primary breadwinners in 40% of households with children in the U.S.29

Some researchers have also identified the phenomenon of “momism” or “new momism” as a societal pressure that unfairly burdens women (especially those with jobs) with unrealistic expectations of what a perfect mother should be. “New momism” was coined by Susan Douglas and Meredith Michaels in 2004, to describe the perception that women are natural caregivers and mothers and as such need to devote their entire life (although “momism” as a term was first used pejoratively by Philip Wylie in his 1942 work Generation of Vipers). This phenomenon has added to the discrimination faced by mothers, particularly those who work, by shaming them for not quitting their job to dedicate all of their time to raising children.30

Age

Ageism, the discrimination against workers solely based on age, is an often-mentioned topic largely because it has the potential to affect anyone regardless of sex, race, or parental status. Everyone, therefore, is susceptible to age discrimination at any time during their lives. However, certain disadvantaged groups may find themselves the victim of ageism more often than others, as prejudices can be combined to a more deleterious effect. “Gendered ageism,” as it affects women, can exacerbate existing issues and may cause women to exit the workforce early, or to not return once having left.31

Research into ageism has not received the same level of study as it has for other areas, such as racism and sexism. Age is often seen as an additional or compounding variable, rather than a real driver of discrimination. Authors Lisa Finkelstein and Donald Truxillo remark, “…although we have age discrimination laws in the United States, they have not gotten anywhere near the attention that ethnic and gender discrimination cases do.”32 As a result, the extant body of literature is small and in need of further research and data.33 However, recent trends see ageism emerging as a focus of study in its own right, and many gender researchers have published work looking at the effect of age on women in the workplace.

A main topic of interest in gendered ageism is retirement and the timing with which women leave the workforce. Women may be more likely to choose an “early exit,” leaving the workforce permanently, as a result of having children or other familial obligations. This can have negative consequences as this often reduces current pay as well as future pay through diminished pensions, Social Security payments, or retirement savings.34 This status as a caretaker may even affect the perception of retirement among women who have children at home. A 2002 study found that even though older childless women, women with children away from home, and women with children at home were equally likely to engage in work, women with children at home were significantly less likely to refer to themselves as retired. The author of the study, Namkee Choi, notes that childless women are able to build up a longer career, while women whose children have left home are no longer burdened by parental obligations, allowing them the freedom to define themselves as retired, even if they are still engaging in paid work. As such, self-defined retirement among women is not solely based on actual working status, but is more of a state of mind and sense of entitlement and thus, “retirement has become more like a status of title to be proud of than an actual marker of a complete withdrawal from the world of work.”35

The expectation placed on women to always act as the primary caretaker, such as the obligation to provide the majority of childcare, does not diminish with age, and may be replaced by having to care for older parents and other family member. Indeed, as Dr. Rosalind Barnett of the Brandeis University Women’s Studies Research Center notes, “Because women outlive their husbands, they are more likely than men to care for their ill and dying parents, in-laws, and spouses, and they are often left widowed and impoverished at the end of their lives.”36 Thus, the decision to continue working for many older women, may not be one of enjoying the work, but of trying to escape poverty and to provide for dependents. One researcher found that women are 70% more likely than men to live in poverty during retirement, while a 1989 study found nearly 20% of women above age 74 living below the poverty level.37 These issues have been compounded in recent years as a result of the recession, particularly among baby boomers and those nearing retirement age. Older workers are retiring later and seeing detrimental effects on their pensions, savings, and home values, making it difficult to completely stop working. Interestingly, the initial research conducted on this topic shows that these factors are affecting men and women in a mostly similar fashion. More research may be needed to parse out the specific gender impacts of the recession on potential retirees.38

Given the potential burdens that women potentially face after retirement, some women may be forced reenter the workforce after having left it. A 2011 study by the DoL found that among women who left the labor force, 13% later returned. The likelihood of women to return to work is affected by a number of factors including age, health, and caretaker status. Work type also plays a role as self-employed women are significantly more likely to reenter the workforce when compared with wage and salary workers. This finding does not occur among men, however.39

Research also suggests that the wage gap between men and women increases as workers get older. Indeed, data from business- and law-school graduates show that wages are equal between the sexes when they first start their careers, but begin diverging five years out, further spreading after 15 years. By 16 years, female MBAs were making 55% of what the males were.40 This trend has been explored by numerous authors (Mincer and Polacheck, etc.) who have found that this widening gap is due to the greater amount of professional opportunities that men receive as they move through their careers, which women are often denied. This can also be exacerbated by interruptions in women’s careers in the labor force by time taken off for pregnancy and childcare, which can stall women’s career advancement as they age. However, this growing gap between men and women as they age actually happens independently of any contributing circumstances like experience or opportunities. That is to say, “Young men are paid more as they age because of age; young women are not.” This comes largely as a result of sexism: Employers show a preference for maturity in men but not in women.41

Some also see the rapid advancement of technology and science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) jobs as leaving older workers behind. Non-traditional and high-tech jobs for women, particularly older women, can also face increased instances of ageism, with one study of IT workers finding a majority thought the term “older worker” described those as young as 35 years old.42 As many of these fields make up an increasing amount of the new jobs being created in America, older workers may feel even more discriminated against in the workplace.

Race

As with age, race can play a compounding factor in the challenges women face in the workplace. However, similar to much of the research on age, many studies do not fully differentiate discrimination by individuals who are both minorities and women, with many concentrating on race as the primary focus. While research exists on both race and gender factors, few studies look closely at the unique challenges faced by minority women at work. One study from NYU finds, “Despite evidence that work constitutes a major life domain among African American women, researchers know relatively little about the work experiences of this group.”43

However, this may not be solely attributable to a gap in the research, but may also be a product of the discrimination that minority women face. According to one study, while both African-American and white women report facing discrimination, such as discriminatory firing, African-American women face it to a greater degree and more often attribute it to race. These African-American women may in fact be experiencing gender discrimination as well, but may be perceiving it exclusively as differential racial treatment.44 Although a few studies exist, there is a gap in the research that specifically explores discrimination by gender and race simultaneously to examine the double minority effect.

In addition to the dual status of gender and race, additional classifications can further disadvantage minority women. Minority women have also been shown to face discrimination by both race and gender, and often face harder economic circumstances than white women in the same jobs. Much of the existing research has focused on the disparate income and security levels faced by these groups. Following the recession, 39% of women overall reported facing difficulties in paying utility bills. However, this number rises to 48% among Hispanic women and 52% among African-American women. Food insecurity rates are also twice as high among African-American and Hispanic women when compared to white women.45

Another compounding factor is the status of mothers. Minority working women are also more likely to be working mothers when compared to white women. Nationwide, one in five families (20%) is headed by a single mother. Yet 27% of Latino and 52% of African-American children are raised by single mothers.46 Given the wage and employment deficiencies that mothers face, this further burdens young minority women, reducing their outlook in terms of wages and status.

Lastly, considering age, this disparity continues across age groups for African-American women in particular, remaining constant all the way through retirement. One study found fewer good work opportunities existing for older African-American women. Further, those who did work had lower wages than older white women.47

Job type

Today, women are working in greater numbers and in more roles than ever before. Whereas in the past women were largely confined, either formally or informally through societal pressures, to a small number of acceptable professions, women in the U.S. today have access to nearly as many job types as men. Women are beginning to fill in many jobs that were previously considered “non-traditional” (those with less than 25% of women in the role) and a large number of positions that were considered non-traditional 25 years ago, such as chemists, physicians, lawyers, and correctional officers, now see women working above the 25% threshold.48

However, the legacy of past gender-role assignments has proven difficult to overcome and still dominates women’s employment decisions today. Among the most prevalent occupations for working women in 2010, secretarial work, nursing, and teaching were the top three professions, much as they have been for decades. This is particularly prevalent in nursing where 91.1% of all registered nurses were female.49 A large number of non-traditional occupations still exist, excluding many women from high-paying and high-status professions such as architects, computer programmers, engineers, and pilots. Furthermore, many of these positions are also noted by the DoL to have strong potential for future growth and demand, making them even more appealing.50 This disparity in positions may also contribute to the gender wage-gap by keeping women in lower paid positions. In his book Categorically Unequal sociologist Douglas Massey highlights the occurrence of “occupational dissimilarity,” the unequal stratification of people in social categories and jobs, specifically as it relates to gender. Since women are more likely to be employed in professions with lower average wages, and are more often excluded from higher-wage categories, the wage gap increases further between genders, notwithstanding the preexisting impact of wage discrimination that exists within job roles.51 The abundance of women in low- to mid-wage professions such as teaching and secretarial work, and the conspicuous absence from executive positions, highlights the significance of the problem.

Addressing the shortage of women in these in-demand positions has been an area of focus for several academics, many of whom note it to be a crucial area for improving women’s employment outlooks. Of particular attention is the lack of female participation in STEM fields, which are among the fastest growing in the country. STEM positions are estimated to grow 17% in the decade between 2008 and 2018, compared with 9.8% growth for other, non-STEM related occupations.52 Yet, women make up less than one-quarter of all STEM positions, and are far less likely to hold a degree in a STEM field. Even among those women who do hold a relevant degree, they are far less likely than male degree-holders to actually work in a STEM field and are more likely to work in a gender-traditional role such as education or healthcare. This represents a major missed opportunity for women Not only do these positions have a strong job outlook, but women in STEM jobs, on average, earn one-third (33%) more compared with women in non-STEM fields. This earnings difference is greater among women than among men, causing the gender wage gap to be smaller in STEM positions than in others.53

Many see this disparity as beginning in K-12 and college and continuing into the workforce. At an early age, girls face societal messages, both overt and implied, steering them away from science and mathematics fields. This can lead to a “stereotype threat” where girls are negatively impacted by the perceived stereotype around them. This has become so ingrained in individuals that even reminding girls of their gender can cause them to perform worse on STEM tests. A study that had female students check a “M” or “F” box at the top of a test showed girls doing worse than others whose tests did not have the gender question at the top.54 These issues can impact women at a young age, even before they enter the workforce, and have a lifelong impact on their career choices.

Some authors find the legacy of gender sortation by job type may be a contributing factor to women’s high levels of employment today. Traditionally male-dominated occupations such as construction and manufacturing were hit particularly hard by the financial crisis, while traditionally female-dominated jobs, such as healthcare, education, and hospitality, have been relatively spared. As a result of the recession, more than 6 million men lost their jobs compared with 2.7 million women.55

In addition to the often-cited “glass ceiling” that prevents women from achieving top positions in corporations such as board members and CEOs, some researchers suggest, it is the “sticky floor”, a phenomenon where entry-level works are prevent from rising through the ranks, which keeps them stuck in lower-level positions. This is particularly true of male-dominated professions where women are even more likely to be clustered at the bottom of the hierarchy. In 2011, women held just 9% of jobs in the construction industry. Among these women, 74% were involved in sales or office-related work.56 However, the opposite is true among men who are able to rise quickly, even in traditionally female-dominated occupations such as nursing and teaching. This explains why there are so many female teachers, but so few female superintendents.57 A 2000 study by the American Association of School Administrators (AASA) found that of the 13,728 superintendents in the country, just 1,984 (14%) are female. This number is particularly striking, considering that 72% of all K-12 educators are women.58

This phenomenon adversely affects women more so than men (although some research has shown it to occur among minority males) largely because of the social and labor dynamics that currently exist in society. Women are also more tied to a geographic location (for perceptions of family responsibilities) than men, and are hence less mobile. Thus, men are more likely than women to receive outside offers and pay increases.59

The Current state of research

The above dimensions represent several of the major obstacles working women in America face today. These factors have been the subject of great deal of research to study, measure, and ideally, solve many of the employment-related issues affecting women.

Ongoing research into women’s employment is primarily conducted by three main groups: governments, academic institutions, and nonprofit organizations. The results from these studies are usually targeted at the general public and policy makers, and are often times made publically available. Research by private companies, although less prevalent, is conducted by a variety of businesses including consulting firms and business that conduct the research on behalf of a government contract. Some studies, such as Accenture’s The Path Forward: International Women’s Day 2012 Global Research Results are funded internally and are released publically to showcase their research capabilities.60 Other research studies, such as Unlocking the full potential of women at work by McKinsey & Company are sponsored by an outside group, in this case, the Wall Street Journal, for their exclusive use.61

The Federal government provides a great deal of statistical information on women including many indicators on employment, health, education, and poverty rates. Although some targeted studies exist, much of this gender-specific information is gleaned from data already being collected through massive nationwide studies such as the National Compensation Study (Bureau of Labor Statistics), National Health Care Surveys (Center for Disease Control and Prevention), Current Population Survey (Bureau of Economic Analysis), and the Survey of Income and Program Participation (Census Bureau). While the information gained from these large-scale studies is important for determining current conditions and trends for working women, the lack of questions directed toward women may limit their usefulness in determining specific issues facing women in the workplace today. Moreover, some of these studies, owing to the desire to preserve longitudinal questions or other reasons, may unfairly introduce gender biases into the results. For example, the latest report from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) notes, “In households where both parents are present the mother is the reference parent. Questions on child care arrangements for each child are asked of the reference parent. If the mother is not available for an interview, the father of the child can give proxy responses for her.”62 While this may reflect the reality in many households in America, automatically defaulting to the mother as the primary caregiver perpetuates the long-held bias that mothers are automatically responsible for the majority of child-rearing duties.

However, more targeted studies of working women have been conducted on behalf of government agencies, such as the Working Women Count! survey in the early 1990s, which was organized by the Women’s Bureau of the DoL. This study specifically focused on the concerns and priorities of women in the workplace, and provided information not only on their current conditions, but on their desires for what they would like to see changed in the future.63

Much of the current research, and by far the largest source of publications on women’s employment, comes from universities and academia. These institutions, many which hold departments or centers dedicated to women and gender studies, are also responsible for some of the recurring and longitudinal studies focused on working women. The Women’s Employment Study (WES) produced by the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy and the University of Michigan began in February 1997 and tracks single mothers who are on or have been on welfare. This study has completed five waves through 2004, and still retains a high proportion of the original sample.64

Many prominent research projects have also been produced by think tanks and non-profit research groups. These studies have provided a great deal of much-needed research, looking at workforce participation among women, as well as issues faced by gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender women. Some groups conduct research in a variety of fields, such as Pew and the Rockefeller Foundation, but produce surveys and studies specifically focused on aspects of women’s employment. Concurrently, some organizations, such as the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) and the National Council for Research on Women (NCRW) are solely focused on providing and promoting research on women’s topics including employment. The IWPR recently partnered with the Rockefeller Foundation to produce a survey of economic security among men and women.65 This study, published in 2010, focused specifically on the economic impact the recent recession is having on women, particularly those in the workplace.

potential Research Gaps

Despite the continued research on women’s studies and women in the workplace, there still remain a number of gaps regarding many important questions in the field.

Perhaps the biggest gap of all in the research involves the inconsistent methods of data collection for the disparate studies on women in the workplace. Studies and research projects on working women are often done on a one-off basis, using small sample sizes. In looking at studies on pregnant working women, Salihu et al. note, “The quality and amount of data collected on pregnancy in the workplace varies by topic area and there is a lack of uniformity of outcomes and measures, which makes it difficult to compare findings across studies.”66 Specifically missing are large-scale, longitudinal studies of women across the country. Additionally, several large studies that have been conducted have ceased and the data are rapidly becoming outdated. Because fundamental research into gender issues is becoming obsolete, more research is necessary to reflect issues affecting the contemporary generation.

Also missing are more granular and focused research efforts regarding specific causes and drivers of women’s experiences in the workplace. Harvard researcher Pamela Stone remarks, “Women with impressive training and credentials do interrupt their careers in significant numbers, but we do not know, beyond the shorthand of “family,” what accounts for these voluntary — and costly — workforce exits.”67 Although there have been a few recent studies (including an informative focus group report on Gen Y working women by the Business and Professional Women’s Foundation68) a greater amount of qualitative research, specifically looking at women’s reasons for choosing to exit or not exit the workplace would provide greater context and understanding regarding the drivers of their decision to continue working or not.

Also conspicuously absent from the research is work looking at men’s and women’s differing perceptions of workplace issues, such as pay and family leave. Much of extant research is focused on objective measures such as salary amounts, number of women in the workforce, number of vacation days, etc. Missing is information on the personal perceptions of these factors in the workplace and how they impact men and women differently.

Finally, although many of the forms of discrimination, such as race, age, gender, and sexual identity have been studied in their own right by researchers, much less common are studies that involve interaction variables, such as those faced by older women or minority women. In examining gender- and age-based discrimination in the workplace, British researchers Colin Duncan and Wendy Loretto note, “…little is known about how age interacts with gender in producing employment disadvantage. Indeed, recent public policy has assumed ageism to be a gender-neutral phenomenon — in the government’s Code of Practice, no distinction was made between age discrimination as it affects men and women.”69 Studies that more accurately seek to determine the impact of gender along with race, age, and job type would be useful in determining how these factors weigh on women’s employment experiences. Additionally, more needs to be done to target the specific decision points among young female students in determining whether to pursue non-traditional or STEM fields. Further research in this area would help to create targeted responses to address the employment disparities in these fields.

Appendix A: Works Reviewed

"10 Findings about Women in the Workplace." Pew Research Centers Social Demographic Trends Project RSS. N.p., 11 Dec. 2013. Web. 1 Mar. 2014. <http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/12/11/10-findings-about-women-in-the-workplace/>.

Angle, John, and David A. Wissmann. "Work Experience, Age, and Gender Discrimination." Social Science Quarterly (University of Texas) 64.1 (1983): 66-84. Print.

Aranda, B., and P. Glick. "Signaling Devotion to Work over Family Undermines the Motherhood Penalty." Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 17.1 (2013): 91-99. Print.

Armour, Stephanie. "Pregnant Workers Report Growing Discrimination." USATODAY.com. USAToday, 17 Feb. 2005. Web. 1 Mar. 2014. <http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/workplace/2005-02-16-pregnancy-bias-usat_x.htm>.

Barnes, Robert. "Supreme Court Rules That States Can’t Be Sued for Denying Workers Medical Leave." WashingtonPost.com. The Washington Post, 20 Mar. 2012. Web. 1 Mar. 2014. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/supreme-court-rules-that-states-cant-be-sued-for-denying-workers-medical-leave/2012/03/19/gIQAB0FNQS_story.html>.

Barnett, Rosalind C. "Ageism and Sexism in the Workplace." Generations (Fall 2005): 25-30. Print.

Barsh, Joanna, and Lareina Yee. Unlocking the Full Potential of Women at Work. Rep. N.p.: McKinsey &, 2012. Print.

Berman, Jillian. "Working Mothers Now Top Earners in Record 40 Percent of Households with Children: Pew." The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 29 May 2013. Web. 1 Mar. 2014. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/05/29/working-mothers-top-earners_n_3351495.html>.

Blackwell, Lauren V., Lori Anderson Snyder, and Catherine Mavriplis. "Diverse Faculty in STEM Fields: Attitudes, Performance, and Fair Treatment." Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 2.4 (2009): 195-205. Print.

Budig, M. J., and M. J. Hodges. "Differences in Disadvantage: Variation in the Motherhood Penalty across White Women's Earnings Distribution." American Sociological Review 75.5 (2010): 705-28. Print.

Bygren, M. "The Gender Composition of Workplaces and Men's and Women's Turnover." European Sociological Review 26.2 (2010): 193-202. Print.

Cahill, Kevin E., Michael D. Giandrea, and Joseph F. Quinn. "Reentering the Labor Force after Retirement." Monthly Labor Review (June 2011): 34-42. Print.

Choi, Namkee G. "Self-Defined Retirement Status and Engagement in Paid Work among Older Working-Age Women: Comparison between Childless Women and Mothers." Sociological Inquiry 72.1 (2002): 43-71. Print.

Conrad, Cecilia. "Black Women: The Unfinished Agenda." The American Prospect. N.p., 20 Sept. 2008. Web. 11 Feb. 2014.

Correll, Shelley J. "Minimizing the Motherhood Penalty: What Works, What Doesn't and Why?" Gender & Work: Challenging Conventional Wisdom; Harvard Business School (2013): n. pag. Print.

Cronin, Brenda. "The Wall Street Journal." Real Time Economics RSS. The Wall Street Journal, 4 Jan. 2014. Web. 24 Feb. 2014. <http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2014/01/04/job-flexibility-seen-as-key-to-equal-pay/>.

Danaher, Kelly, and Christian S. Crandall. "Stereotype Threat in Applied Settings Re-Examined." Journal of Applied Social Psychology 38.6 (2008): 1639-655. Print.

Douglas, Susan J., and Meredith W. Michaels. The Mommy Myth: The Idealization of Motherhood and How It Has Undermined Women. New York: Free, 2004. Print.

Duncan, Colin, and Wendy Loretto. "Never the Right Age? Gender and Age-Based Discrimination in Employment." Gender, Work and Organization 11.1 (2004): 95-115. Print.

"Economics and Statistics Administration." Women in STEM: A Gender Gap to Innovation. U.S. Department of Commerce, 3 Aug. 2011. Web. 11 Mar. 2014. <http://www.esa.doc.gov/Reports/women-stem-gender-gap-innovation>.

Eisenberg, Susan. We'll Call You If We Need You: Experiences of Women Working Construction. Ithaca, NY: ILR, 1998. Print.

England, Paula, Janet Gornick, and Emily Fitzgibbons Shafer. "Women's Employment, Education, and the Gender Gap in 17 Countries." Monthly Labor Review (April 2012): 3-12. Print.

"The Family and Medical Leave Act: 10 Years Later." IBEW Journal. IBEW, Feb. 2003. Web. 24 Feb. 2014. <http://www.ibew.org/articles/03journal/0301/page10.htm>.

Fideler, Elizabeth F. Women Still at Work: Professionals over Sixty and on the Job. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012. Print.

Finkelstein, Lisa, and Donald Truxillo. "Age Discrimination Research Is Alive and Well, Even If It Doesn't Live Where You'd Expect." Industrial and Organizational Psychology 6.1 (2013): 100-02. Print.

Gangl, Markus, and Andrea Ziefle. "Motherhood, Labor Force Behavior, and Women’s Careers: An Empirical Assessment of the Wage Penalty for Motherhood in Britain, Germany, and the United States." Demography 46.2 (2009): 341-69. Print.

Gill, Judith, Julie Mills, Suzanne Franzway, and Rhonda Sharp. "‘Oh You Must Be Very Clever!’ High‐achieving Women, Professional Power and the Ongoing Negotiation of Workplace Identity." Gender and Education 20.3 (2008): 223-36. Print.

Glass, Thomas E. "Where Are All the Women Superintendents?" AASA.org. AASA, June 2000. Web. 28 Feb. 2014. <http://aasa.org/SchoolAdministratorArticle.aspx?id=14492>.

Goldin, Claudia. A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter. Rep. N.p.: Harvard University, 2013. Print.

Gordon, Judith R., Karen S. Whelan-Berry, and Elizabeth A. Hamilton. "The Relationship among Work-family Conflict and Enhancement, Organizational Work-family Culture, and Work Outcomes for Older Working Women." Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 12.4 (2007): 350-64. Print.

Gutek, Barbara A. "Women and Paid Work." Psychology of Women Quarterly 25.4 (2001): 379-93. Print.

Handy, J., and D. Davy. "Gendered Ageism: Older Women's Experiences of Employment Agency Practices." Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 45.1 (2007): 85-99. Print.

Hayes, Jeff, Ph.D., and Heidi Hartmann, Ph.D. Women and Men Living on the Edge: Economic Insecurity A. Rep. N.p.: IWPR/Rockefeller, 2010. Print.

Henderson, Angela C., Sandra M. Harmon, and Jeffrey Houser. "A New State of Surveillance?" Surveillance & Society 7.3/4 (2010): 231-47. Print.

Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, Kerrie Peraino, Laura Sherbin, and Karen Sumberg. The Sponsor Effect: Breaking through the Last Glass Ceiling. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business Review, 2010. Print.

Hill, Elizabeth T. "The Labor Force Participation of Older Women: Retired? Working? Both?" Monthly Labor Review (September 2002): 39-48. Print.

House, Jonathan. "Women Reach a Milestone in Job Market." The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, 20 Nov. 2013. Web. 24 Feb. 2014. <http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303755504579203833804047994>.

Hughes, Diane, and Mark A. Dodge. "African American Women in the Workplace: Relationships." American Journal of Community Psychology 25.5 (1997): 581-99. Print.

Judge, Timothy A., Beth A. Livingston, and Charlice Hurst. "Do Nice Guys—and Gals—really Finish Last? The Joint Effects of Sex and Agreeableness on Income." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 102.2 (2012): 390-407. Print.

Kara Nichols. Gen Y Women in the Workplace: Focus Group Summary Report. Rep. N.p.: Young Careerist: Business and Professional Women's Foundation, 2011. Print.

LaTour, Jane. Sisters in the Brotherhoods: Working Women Organizing for Equality in New York City. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. Print.

Massey, Douglas S. Categorically Unequal: The American Stratification System. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2007. Print.

McBride, Anne. "Lifting the Barriers? Workplace Education and Training, Women and Job Progression." Gender, Work, and Organization 18.5 (2011): 528-47. Print.

NAWIC Facts. Issue brief. N.p.: National Association of Women in Construction, 2012. Print.

Neumark, David. Sex Differences in Labor Markets. London: Routledge, 2004. Print.

Nunenmacher, Julie, and Bobbie Schnepf. "Battle of the Bulge." The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences 6.11 (2021): 167-76. Print.

Ortiz, Susan Y., and Vincent J. Roscigno. "DISCRIMINATION, WOMEN, AND WORK: Processes and Variations by Race and Class." Sociological Quarterly 50.2 (2009): 336-59. Print.

Oyoung, Maryn. "Until Men Bear Children, Women Must Not Bear the Costs of Reproductive Capacity: Accommodating Pregnancy in the Workplace to Achieve Equal Employment Opportunities." McGeorge Law Review 44 (2013): 515-43. Print.

The Path Forward: International Women's Day 2012 Global Research Results. Rep. N.p.: Accenture, 2012. Print.

Paton, Nic. "Bosses Reluctant to Employ Women of Childbearing Age." Mangement-Issues.com. Mangement-Issues.com, 25 Nov. 2005. Web. 11 Mar. 2014. <http://www.management-issues.com/news/2803/bosses-reluctant-to-employ-women-of-childbearing-age/>.

Salihu, H. M., J. Myers, and E. M. August. "Pregnancy in the Workplace." Occupational Medicine 62.2 (2012): 88-97. Print.

Sandberg, Sheryl. Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013. Print.

Schulte, Brigid. "Landmark Family Leave Law Doesn’t Help Millions of Workers." WashingtonPost.com. The Washington Post, 16 Feb. 2013. Web. 6 Mar. 2014. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/landmark-family-leave-law-doesnt-help-millions-of-workers/2013/02/10/aa1cd468-720f-11e2-8b8d-e0b59a1b8e2a_story.html>.

Silva, Christine, Nancy M. Carter, and Anna Beninger. Good Intentions, Imperfect Execution? Women Get Fewer of the "Hot Jobs" Needed to Advance. Rep. New York: Catalyst, 2012. Print.

Smeding, Annique. "Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM): An Investigation of Their Implicit Gender Stereotypes and Stereotypes’ Connectedness to Math Performance." Sex Roles 67.11-12 (2012): 617-29. Print.

Staff, Jeremy, and Jeylan T. Mortimer. "Explaining the Motherhood Wage Penalty During the Early Occupational Career." Demography 49.1 (2012): 1-21. Print.

"State Family and Medical Leave Laws." Nolo.com. Nolo, n.d. Web. 7 Mar. 2014. <http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/state-family-medical-leave-laws>.

"STEM: Good Jobs Now and For the Future." Economics & Statistics Administration. U.S. Department of Commerce, 14 July 2011. Web. 24 Feb. 2014. <http://www.esa.doc.gov/Reports/stem-good-jobs-now-and-future>.

Stone, Pamela. 'Opting Out': Challenging Stereotypes and Creating Real Options For Women in the Professions. Rep. N.p.: Havard Business School, 2013. Print.

United States. OFCCP. Know Your Rights: Pregnancy & Childbirth Discrimination. N.p.: U.S. Department of Labor, n.d. Print.

United States. Who's Minding the Kids?: Child Care Arrangements: Spring 2011. By Lynda Laughlin. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 2013. Print.

United States. Working Women Count!: A Report to the Nation. By Robert B. Reich and Laren Nussbaum. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Labor, Women's Bureau, 1994. Print.

Weaver, David A. "The Work and Retirement Decisions of Older Women." Social Security Bulletin 57.1 (1994): 3-25. Print.

"Women's Bureau - Quick Stats on Women Workers, 2010." Women's Bureau - Quick Stats on Women Workers, 2010. Department of Labor, n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2014. <http://www.dol.gov/wb/factsheets/QS-womenwork2010.htm>.

"Women's Bureau (WB) - Nontraditional Occupations for Women in 2008." Women's Bureau (WB) - Nontraditional Occupations for Women in 2008. Department of Labor, Apr. 2009. Web. 1 Mar. 2014. <http://www.dol.gov/wb/factsheets/nontra2008.htm>.

"The Women's Employment Study." Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy. University of Michigan, n.d. Web. 28 Feb. 2014. <http://fordschool.umich.edu/research/poverty/wes/>.

Yap, Margaret, and Alison Konrad. "Is There a Sticky Floor, a Mid-Level Bottleneck, or a Glass Ceiling?" Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations 64.4 (2009): 593-619. Print.

1 Sandberg, Sheryl. Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013. Print.

2 "10 Findings about Women in the Workplace." Pew Research Centers Social Demographic Trends Project RSS. N.p., 11 Dec. 2013. Web. 1 Mar. 2014.

3 Sandberg, Sheryl. Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013. Print.

4 House, Jonathan. "Women Reach a Milestone in Job Market." The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, 20 Nov. 2013. Web. 24 Feb. 2014.

5 Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, Kerrie Peraino, Laura Sherbin, and Karen Sumberg. The Sponsor Effect: Breaking through the Last Glass Ceiling. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business Review, 2010. Print.

6 "Women's Bureau - Quick Stats on Women Workers, 2010." Women's Bureau - Quick Stats on Women Workers, 2010. Department of Labor, n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2014.

7 "10 Findings about Women in the Workplace." Pew Research Centers Social Demographic Trends Project RSS. N.p., 11 Dec. 2013. Web. 1 Mar. 2014.

8 Silva, Christine, Nancy M. Carter, and Anna Beninger. Good Intentions, Imperfect Execution? Women Get Fewer of the "Hot Jobs" Needed to Advance. Rep. New York: Catalyst, 2012. Print.

9 Sandberg, Sheryl. Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013. Print.

10 Silva, Christine, Nancy M. Carter, and Anna Beninger. Good Intentions, Imperfect Execution? Women Get Fewer of the "Hot Jobs" Needed to Advance. Rep. New York: Catalyst, 2012. Print.

11 Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, Kerrie Peraino, Laura Sherbin, and Karen Sumberg. The Sponsor Effect: Breaking through the Last Glass Ceiling. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business Review, 2010. Print.

12 Armour, Stephanie. "Pregnant Workers Report Growing Discrimination." USATODAY.com. USAToday, 17 Feb. 2005. Web. 1 Mar. 2014.

13 United States. OFCCP. Know Your Rights: Pregnancy & Childbirth Discrimination. N.p.: U.S. Department of Labor, n.d. Print.

14 Paton, Nic. "Bosses Reluctant to Employ Women of Childbearing Age." Mangement-Issues.com. Mangement-Issues.com, 25 Nov. 2005. Web. 11 Mar. 2014.

15 Barnett, Rosalind C. "Ageism and Sexism in the Workplace." Generations (Fall 2005): 25-30. Print.

16 "The Family and Medical Leave Act: 10 Years Later." IBEW Journal. IBEW, Feb. 2003. Web. 24 Feb. 2014.

17 Oyoung, Maryn. "Until Men Bear Children, Women Must Not Bear the Costs of Reproductive Capacity: Accommodating Pregnancy in the Workplace to Achieve Equal Employment Opportunities." McGeorge Law Review 44 (2013): 515-43. Print.

18 "State Family and Medical Leave Laws." Nolo.com. Nolo, n.d. Web. 7 Mar. 2014.

19 Barnes, Robert. "Supreme Court Rules That States Can’t Be Sued for Denying Workers Medical Leave." WashingtonPost.com. The Washington Post, 20 Mar. 2012. Web. 1 Mar. 2014.

20 Schulte, Brigid. "Landmark Family Leave Law Doesn’t Help Millions of Workers." WashingtonPost.com. The Washington Post, 16 Feb. 2013. Web. 6 Mar. 2014.

21 Gangl, Markus, and Andrea Ziefle. "Motherhood, Labor Force Behavior, and Women’s Careers: An Empirical Assessment of the Wage Penalty for Motherhood in Britain, Germany, and the United States." Demography 46.2 (2009): 341-69. Print.

22 Staff, Jeremy, and Jeylan T. Mortimer. "Explaining the Motherhood Wage Penalty During the Early Occupational Career." Demography 49.1 (2012): 1-21. Print.

23 Correll, Shelley J. "Minimizing the Motherhood Penalty: What Works, What Doesn't and Why?" Gender & Work: Challenging Conventional Wisdom; Harvard Business School (2013): n. pag. Print.

24 Aranda, B., and P. Glick. "Signaling Devotion to Work over Family Undermines the Motherhood Penalty." Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 17.1 (2013): 91-99. Print.

25 Correll, Shelley J. "Minimizing the Motherhood Penalty: What Works, What Doesn't and Why?" Gender & Work: Challenging Conventional Wisdom; Harvard Business School (2013): n. pag. Print.

26 Kara Nichols. Gen Y Women in the Workplace: Focus Group Summary Report. Rep. N.p.: Young Careerist: Business and Professional Women's Foundation, 2011. Print.

27 Goldin, Claudia. A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter. Rep. N.p.: Harvard University, 2013. Print.

28 Sandberg, Sheryl. Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013. Print.

29 Berman, Jillian. "Working Mothers Now Top Earners In Record 40 Percent Of Households With Children: Pew." The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 29 May 2013. Web. 1 Mar. 2014.

30 Nunenmacher, Julie, and Bobbie Schnepf. "Battle of the Bulge." The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences 6.11 (2001): 167-76. Print.

31 Handy, J., and D. Davy. "Gendered Ageism: Older Women's Experiences of Employment Agency Practices." Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 45.1 (2007): 85-99. Print.

32 Finkelstein, Lisa, and Donald Truxillo. "Age Discrimination Research Is Alive and Well, Even If It Doesn't Live Where You'd Expect." Industrial and Organizational Psychology 6.1 (2013): 100-02. Print.

33 Weaver, David A. "The Work and Retirement Decisions of Older Women." Social Security Bulletin 57.1 (1994): 3-25. Print.

34 Duncan, Colin, and Wendy Loretto. "Never the Right Age? Gender and Age-Based Discrimination in Employment." Gender, Work and Organization 11.1 (2004): 95-115. Print.

35 Choi, Namkee G. "Self-Defined Retirement Status and Engagement in Paid Work among Older Working-Age Women: Comparison between Childless Women and Mothers." Sociological Inquiry 72.1 (2002): 43-71. Print.

36 Barnett, Rosalind C. "Ageism and Sexism in the Workplace." Generations (Fall 2005): 25-30. Print.

37 Hill, Elizabeth T. "The Labor Force Participation of Older Women: Retired? Working? Both?" Monthly Labor Review (September 2002): 39-48. Print.

38 Burtless, Gary, and Barry P. Bosworth. Impact of the Great Recession on Retirement Trends in Industrialized Countries. Rep. N.p.: Brookings Institution, 2013. Print.

39 Cahill, Kevin E., Michael D. Giandrea, and Joseph F. Quinn. "Reentering the Labor Force after Retirement." Monthly Labor Review (June 2011): 34-42. Print.

40 Cronin, Brenda. "The Wall Street Journal." Real Time Economics RSS. The Wal Street Journal, 4 Jan. 2014. Web. 24 Feb. 2014.

41 Angle, John, and David A. Wissmann. "Work Experience, Age, and Gender Discrimination." Social Science Quarterly (University of Texas) 64.1 (1983): 66-84. Print.

42 Duncan, Colin, and Wendy Loretto. "Never the Right Age? Gender and Age-Based Discrimination in Employment." Gender, Work and Organization 11.1 (2004): 95-115. Print.

43 Hughes, Diane, and Mark A. Dodge. "African American Women in the Workplace: Relationships." American Journal of Community Psychology 25.5 (1997): 581-99. Print.

44 Ortiz, Susan Y., and Vincent J. Roscigno. "DISCRIMINATION, WOMEN, AND WORK: Processes and Variations by Race and Class." Sociological Quarterly50.2 (2009): 336-59. Print.

45 Hayes, Jeff, Ph.D., and Heidi Hartmann, Ph.D. Women and Men Living on the Edge: Economic Insecurity A. Rep. N.p.: IWPR/Rockefeller, 2010. Print.

46 Sandberg, Sheryl. Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013. Print.

47 Hill, Elizabeth T. "The Labor Force Participation of Older Women: Retired? Working? Both?" Monthly Labor Review (September 2002): 39-48. Print.

48 "Women's Bureau (WB) - Nontraditional Occupations for Women in 2008." Women's Bureau (WB) - Nontraditional Occupations for Women in 2008. Department of Labor, Apr. 2009. Web. 1 Mar. 2014.

49 "Women's Bureau - Quick Stats on Women Workers, 2010." Women's Bureau - Quick Stats on Women Workers, 2010. Department of Labor, n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2014.

50 "Women's Bureau (WB) - Nontraditional Occupations for Women in 2008." Women's Bureau (WB) - Nontraditional Occupations for Women in 2008. Department of Labor, Apr. 2009. Web. 1 Mar. 2014.

51 Massey, Douglas S. Categorically Unequal: The American Stratification System. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2007. Print.

52 "STEM: Good Jobs Now and For the Future." Economics & Statistics Administration. U.S. Department of Commerce, 14 July 2011. Web. 24 Feb. 2014.

53 "Economics and Statistics Administration." Women in STEM: A Gender Gap to Innovation. U.S. Department of Commerce, 3 Aug. 2011. Web. 11 Mar. 2014.

54 Danaher, Kelly, and Christian S. Crandall. "Stereotype Threat in Applied Settings Re-Examined." Journal of Applied Social Psychology 38.6 (2008): 1639-655. Print.

55 House, Jonathan. "Women Reach a Milestone in Job Market." The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, 20 Nov. 2013. Web. 24 Feb. 2014.

56 NAWIC Facts. Issue brief. N.p.: National Association of Women in Construction, 2012. Print.

57 Barnett, Rosalind C. "Ageism and Sexism in the Workplace." Generations (Fall 2005): 25-30. Print.

58 Glass, Thomas E. "Where Are All the Women Superintendents?" AASA.org. AASA, June 2000. Web. 28 Feb. 2014.

59 Yap, Margaret, and Alison Konrad. "Is There a Sticky Floor, a Mid-Level Bottleneck, or a Glass Ceiling?" Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations 64.4 (2009): 593-619. Print.

60 The Path Forward: International Women's Day 2012 Global Research Results. Rep. N.p.: Accenture, 2012. Print.

61 Barsh, Joanna, and Lareina Yee. Unlocking the Full Potential of Women at Work. Rep. N.p.: McKinsey &, 2012. Print.

62 United States. Who's Minding the Kids?:Child Care Arrangements: Spring 2011. By Lynda Laughlin. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 2013. Print.

63 United States. Working Women Count!: A Report to the Nation. By Robert B. Reich and Laren Nussbaum. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Labor, Women's Bureau, 1994. Print.

64 "The Women's Employment Study." Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy. University of Michigan, n.d. Web. 28 Feb. 2014.

65 Hayes, Jeff, Ph.D., and Heidi Hartmann, Ph.D. Women and Men Living on the Edge: Economic Insecurity A. Rep. N.p.: IWPR/Rockefeller, 2010. Print.

66 Salihu, H. M., J. Myers, and E. M. August. "Pregnancy in the Workplace." Occupational Medicine 62.2 (2012): 88-97. Print.

67 Stone, Pamela. 'Opting Out': Challenging Stereotypes and Creating Real Options For Women in the Professions. Rep. N.p.: Havard Business School, 2013. Print.

68 Kara Nichols. Gen Y Women in the Workplace: Focus Group Summary Report. Rep. N.p.: Young Careerist: Business and Professional Women's Foundation, 2011. Print.

69 Duncan, Colin, and Wendy Loretto. "Never the Right Age? Gender and Age-Based Discrimination in Employment." Gender, Work and Organization 11.1 (2004): 95-115. Print.

DRAFT

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| File Title | WORKING WOMEN COUNT: REVIEW OF LITERATURE |

| Author | Gallup, Inc. |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-24 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy