CFSAN Usability Study for Feedback on Consumer Food Safety Educator's Planning and Evaluation Toolkit

Generic Clearance for the Collection of Qualitative Feedback on Food and Drug Administration Service Delivery

2016 06 24 Draft Eval Toolkit-062416

CFSAN Usability Study for Feedback on Consumer Food Safety Educator's Planning and Evaluation Toolkit

OMB: 0910-0697

OMB No: 0910-0697 Expiration Date: 09/30/2017

Paperwork Reduction Act Statement: The public reporting burden for this collection of information has been estimated to average 120 minutes per response for reviewing this document. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspects of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing burden to [email protected].

Draft: Planning and Evaluation 101 – A

Toolkit for Consumer Food Safety Educators

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Overview and Importance of Evaluation 2

Chapter 2: Formative Program Planning 5

Chapter 3: Mapping the Intervention and Evaluation 20

Chapter 1: Overview and Importance of Evaluation

Consumer food safety education and evaluation

Foodborne illness is a serious public health problem in the United States, affecting 48 million people and causing 127,839 hospitalizations and 3,037 deaths each year [5,8]. Cases of foodborne illness come with heavy economic costs, totaling approximately $51-$77.7 billion each year [6,8]. These costs include medical and hospital bills, lost work productivity, costs of lawsuits, legal fees, and a loss of sales and consumers [2,3]. Foodborne illness also causes emotional tolls and burdens on family members when caring for friends and relatives or when experiencing the loss of a loved one [3].

Microbial risk due to improper food preparation and handling by consumers in the home is a preventable cause of foodborne illness. Health educators across the nation have engaged in educational activities to increase the public’s awareness and knowledge about food safe practices and the risk of food borne illness, and to promote safe food handling practices. However, a recent comprehensive assessment of consumer food safety education found several areas of concern [8]. The paper identified a lack of rigorous and evidence based evaluation of educational program activities [8]. Recommendations were also made to improve research designs by ensuring that interventions focus on the specific needs of the target audience and address common influencers of consumer food safety practices, such as specific knowledge, perceived susceptibility, and access to resources [8].

In order to ensure that consumer food safety education programs are effective in achieving their goals and preventing foodborne illness it is important that they incorporate a rigorous and thorough program evaluation. In addition, planning of interventions must be strategic, evidence based, and tailored specifically for target audiences. This toolkit was created to serve as a guide with tips, tools, and examples to help consumer food safety educators develop and evaluate their programs and activities.

Why evaluate?

Evaluating your program is important and beneficial to its overall success. For example:

An evaluation can help you identify the strengths and weaknesses of your program, learn from mistakes, and allow you to continuously refine and improve program strategies.

By using evaluation data to improve program practices you can ensure that resources are utilized as efficiently and effectively as possible.

Evaluation data can provide program staff with valuable insight to help them understand the impact of the program, the audience they are serving, and the role they can play to contribute to the program’s success.

There is no way to really know what kind of impact or affect your program or activities are having without a program evaluation.

Conducting an evaluation can help you monitor the program and ensure accountability.

Sharing what you learned from the evaluation with other consumer food safety educators can help them design their own programs more effectively.

Having documentation and data that shows how your program works can help you receive continued or new funding. Evaluation data is usually expected when applying for grants.

Demonstrating that your program has an impact can help increase support of activities by other researchers, educators, and the greater community.

Showing the target audience how your program works and is effective can help increase interest and participation.

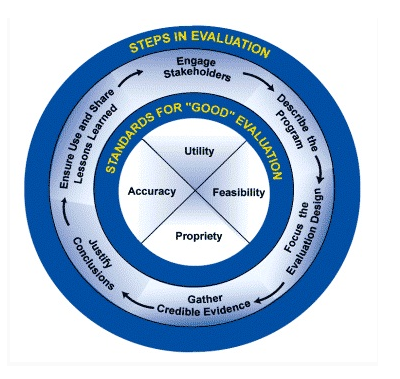

Evaluation standards

The Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation (JCSEE) has identified five attributes of standards to ensure that evaluations of educational programs are ethical, feasible, and thorough. The five attributes, Utility, Feasibility, Propriety, Accuracy, and Evaluation Accountability, include a list of standards it is important to consider when evaluating your program.

Below are brief descriptions of each attribute and examples of standards which they include [4,7,9] -

Utility standards help ensure that program evaluations are informative, influential, and provide the target audience or stakeholders with valuable and relevant information. These standards require evaluators to thoroughly understand the target audiences’ needs and to address them in the evaluation.

Examples of standards related to Utility are – Attention to Stakeholders, Explicit Values, Timely and Appropriate Communicating and Reporting, and Concern for Consequences and Influence.

Feasibility standards are intended to ensure that evaluation designs are able to function effectively in field settings and that the evaluation process is efficient, realistic, and frugal.

Examples of standards related to Feasibility are – Project Management, Practical Procedures, and Resource Use.

Propriety standards protect the rights of individuals who might be affected by the evaluation and support practices that are fair, legal, and just. They ensure that the evaluators are respectful and sensitive to the people they work with and that they follow relevant laws.

Examples of standards related to Propriety are – Formal Agreements, Human Rights and Respect, Clarity and Fairness, and Conflicts of Interest.

Accuracy standards ensure that evaluation data, technical information, and reporting are accurate in assessing the programs worth or merit.

Examples of standards related to Accuracy are Justified Conclusions and Decisions, Valid information, Reliable Information, and Explicit Evaluation Reasoning.

Evaluation Accountability standards encourage sufficient documentation of evaluation processes, program accountability, and an evaluation of the evaluation, referred to as a metaevaluation. This provides opportunities to understand the quality of the evaluation and for continuous improvement of evaluation practices.

Examples of standards related to Evaluation Accountability are – Evaluation Documentation and Internal Metaevaluation.

Click for a full list of the program evaluation standards and to learn more about them.

Keep these standards in mind as you plan your program and the evaluation. Remember, it is not only important to evaluate your education program, but also to think about the quality of your evaluation and to ensure that it is ethical, accurate, and thorough. In addition, a key factor for having a successful evaluation is to think about these standards and plan your evaluation before you implement your program, not after.

References

Arnold, M. E. (2006). Developing evaluation capacity in extension 4-h field faculty - a framework for success. American Journal of Evaluation. 27(2), 257-269.

Buzby, J., Roberts T, Jordan Lin CT, Roberts, T, & MacDonald, J. (1996). Bacterial foodborne disease: medical costs and productivity Losses. United States Department of Agriculture–Economic Research Service (USDA–ERS). Agricultural Economics Report No. (AER741) 100 pp.

Nyachuba, D. G. (2010). Foodborne illness: is it on the rise? Nutrition Reviews, 68(5), 257-269.

Sanders, J. (1994). The program evaluation standards: how to assess evaluations of educational programs (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Scallan, E, PM Griffen, FJ Angulo, RV Tauxe, & RM Hoekstra. (2011). Foodborne illness acquired in the united states-unspecified agents. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 17, 16-22.

Scharff. RL. (2012). Economic burden from health losses due to illness in the united states. Journal of Food Protection. 75, 123-131.

The Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation (JCSEE). (2016). Program evaluation standards statements. Retrieved from: http://www.jcsee.org/program-evaluation-standards-statements

White Paper on Consumer Research and Food Safety Education. (DRAFT).

Yarbrough, D. B., Shulha, L. M., Hopson, R. K., & Caruthers, F. A. (2011). The program evaluation standards: A guide for evaluators and evaluation users (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chapter 2: Formative Program Planning

Form a planning and evaluation team.

Before implementing and evaluating your program, it is important to thoughtfully and thoroughly plan out program and evaluation activities. Having a team to focus on planning and evaluation can be beneficial throughout this process. A team can bring unique and diverse ideas to the table, ensure the needs of various stakeholders are being met, and allow for tasks to be divided up and not a burden to only one or two individuals.

Select a team leader

You may decide to select a planning and evaluation team leader to facilitate and coordinate team activities. Having a “go-to” person to co-ordinate activities and provide leadership throughout the development and implementation of the program can help things operate as smooth as possible. The team leader can function as a point person to ensure that important decisions are made when necessary, without the confusion of who has the responsibility to make final decisions. Remember, it is not the job of the team leader to do everything. The team leader has the responsibility to ensure important tasks are taken care of and completed, and this is usually done through delegating to other team members or staff. Below are important things to think about when selecting a team leader.

An effective team leader:

Understands the overarching goals and priorities of the program and what tasks must be accomplished.

Has strong interpersonal skills and is able to communicate and work effectively with staff and partners.

Is good at delegating responsibilities and tasks to others.

Is supportive and encouraging of others.

Is able to refer to other individuals with specific expertise in program development, evaluation or food safety for recommendations or insight.

Has a realistic understanding of program resources and limitations but also encourages staff and partners to be creative and innovative when planning and strategizing.

Understands and teaches the importance of utilizing research and evidence based strategies when implementing consumer food safety education campaigns and interventions.

Is flexible and able to acknowledge both the strengths and weaknesses of the program.

Uses evaluation data and participant, staff, and partner input to continuously improve the program.

Build partnerships

When forming your team, think about stakeholders or partners you might want to work with or have represented. Consider including a key informant or community expert from the target audience to provide valuable insight about the individuals you are trying to reach. Stakeholders may include individuals who will help implement the program, those who the program aims to serve or your target audience, and individuals who make decisions that impact food safety. You may also want to think about inviting or hiring an experienced evaluator to join your team. A benefit of hiring an external evaluator, instead of solely relying on staff members, is the potential of reducing bias and increasing objectivity of throughout the evaluation process [15,17,21]. Below is a list of potential partners or stakeholders to consider inviting to join your team.

Potential partners:

Food safety researchers

Health professionals

Health educators

External evaluators

Key informants or representatives from your target community

Previous participants of your program if applicable

Teachers

Representatives from local grocery stores or supermarkets

Representatives from local health organizations or health departments doing work related to food safety

Staff from local food banks, community centers, or WIC clinics

There are nine key elements to a successful partnership. They are: 1. Provide clarity of purpose 2. Entrust ownership 3. Identify the right people with which to work 4. Develop and maintain a level of trust 5. Define roles and working arrangements 6. Communicate Openly 7. Provide adequate information using a variety of methods 8. Demonstrate appreciation 9. Give feedback [6]. Keep these elements in mind, share them with your team members, and incorporate them into your team structure and interactions to foster strong and fruitful partnerships.

[6]

Identify the food safety education needs of the target audience

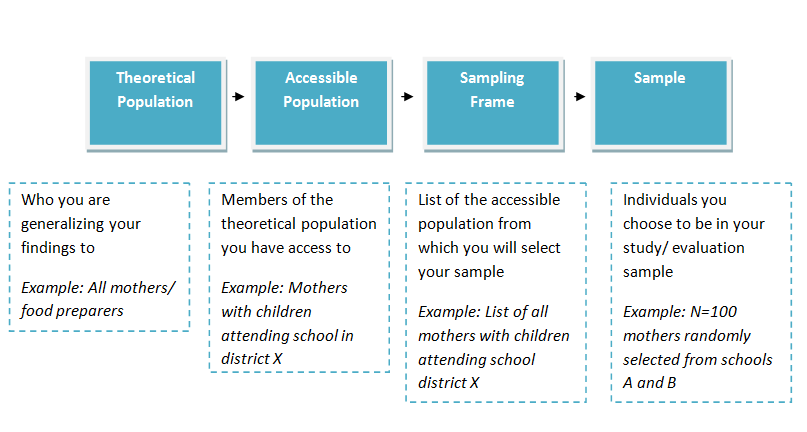

Before planning program activities you will need to figure out exactly who your target audience is, the barriers and challenges they face in implementing safe food handling practices, and their specific food safety needs so that you can design a need based program.

Identify the target audience

First, identify your target audience or the segment of the community that your program will focus on and serve. The target audience can consist of individuals who are most vulnerable to foodborne illness, individuals who will most benefit of your materials and resources, and/or people who can function as gatekeepers and will utilize your program to not only benefit themselves, but others as well. For example, focusing on parents and increasing their knowledge about food safety may lead them to model and teach safe food practices to their children.

If you already have a behavior in mind, your target audience can be individuals who do not already practice that behavior [5]. For example, if the target behavior is correct handwashing, the target audience can be individuals who wash their hands incorrectly [5]. In this case, since you have already identified the target behavior, you will then need to conduct some research or a community needs assessment to determine what part of the population tends to wash their hands incorrectly. The group that you identify will be your target audience.

Alternatively, you may wish to start by conducting some food safety research in order to identify vulnerable populations that you might want to select as the target audience. For example you may look at some recent research and find that higher socio economic groups are associated with higher incidence of Campylobacter, Salmonella, and E.coli, or that low SES children may be at greater risk of foodborne illness [4,8,29]. This information can help you narrow down the target audience by socio economic status and you can then use tools such as interactive Community Commons maps to identify specific populations or geographic locations in your community to focus on based on chosen characteristics.

You can also select your target audience by identifying a segment of the community or a specific setting to focus on (parents or teenagers in a specific school district, residents in a specific zip code, and residents of a senior center). Once the setting has been selected, conduct a needs assessment to identify what target food safety behaviors you should to focus on.

Examples of populations you could target:

Older adults

Parents

Teachers

Food service staff or volunteers

Assisted living aids

Vulnerable populations: children, older adults, pregnant women, individuals with weaker immune symptoms due to disease or treatment [11]

Conduct a needs assessment

In your needs assessment you will want to find out what factors influence your target audience’s food handling practices. Identifying these factors will help you figure out what strategies you need adopt to address specific barriers and promote safe food handling behaviors. You don’t need to start from scratch. Do some research to find out what information and resources already exist on the behavior or population you want to focus on. This can help you identify important food safety factors to address in the assessment or gaps that you might want to further investigate.

Below are important food safety factors you could explore in your needs assessment and examples of questions you might want to ask about [adapted 30].

Access to resources: Are there any resource barriers that prevent the target audience from adopting certain food safe practices? Examples include: lack of thermometers, soap, or storage containers.

Convenience: Are there any convenience barriers, such as time or level of ease, the target audience thinks prevents them from implementing safe food handling behaviors?

Cues to action: Are there any reminders or cues the audience thinks would motivate them to engage in certain food safe practices? Are there any that they have found to be successful in the past?

Knowledge:

Inaccurate knowledge or beliefs: Does the target audience have any inaccurate beliefs related to food safety and foodborne illness? For example, does the individual overestimate their knowledge about food safety or underestimate their susceptibility to food borne illness?

Specific knowledge: Does the target audience have any specific knowledge gaps related to food safety and food handling behaviors?

Knowledge - Why: Does the audience understand why a specific behavior is recommended and how it prevents foodborne illness?

Knowledge - When: Does the audience understand exactly when and under what circumstances they should engage in a specific food handling behavior?

Knowledge - How (self-efficacy): Does the audience know how to engage in the specific behavior? Does the individual believe they are capable of engaging in the behavior?

Public policy: Are there any policies in place that prevents or makes it more challenging for the target audience to engage in a recommended behavior? What existing policies influence the audience’s food safety knowledge, attitudes or behaviors?

Sensory appeal: How do the smell, appearance, taste, and texture of a food influence the target audience’s food handling practices?

Severity: Is the audience aware of the short and long term consequences of food borne illness?

Social norms and culture: What kind of food safety attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors does the target audience’s social circle, including family and friends, possess and engage in?

Socio-demographics: What is the demographic and socio economic status of the target audience? Examples of demographic factors include gender, ethnicity, age, and education level.

Susceptibility: How susceptible does the audience feel they are to foodborne illness resulting from food handling practices at home?

Trust of educational messages: How trusting is the target audience of consumer food safety messages? Do they find sources of these messages to be credible?

For more specific recommendations and strategies on how to address the factors listed above refer to the White Paper on Consumer Research and Food Safety Education (DRAFT).

How They Did It

When planning “Is It Done Yet?” a social marketing campaign to increase the use of thermometers in order to prevent foodborne illness, a specific audience, upscale suburban parents, was identified and targeted. This target audience was carefully chosen for specific reasons such as being more likely to rapidly move through the stages of behavior change to adopt the desired behavior, their tendency to be influencers and trend setters, and because of their propensity to learn and use new information.

Geodemographic research was conducted to get to know this population to learn about their interests, characteristics, and where they access information. Observational research in a kitchen setting was also conducted to learn about how the parents use thermometers and handle foods. This helped program planners identify important barriers that would need to be addressed in the campaign and gather information to help test and develop campaign messages. Messages were pilot tested at a “special event” held in a popular home and cooking store where participants were able to provide feedback on several message concepts. Following the event, additional focus groups were conducted to select the final campaign slogan, “Is It Done yet? You can’t tell by looking. Use a thermometer to be sure.”

Before implementing the campaign, baseline data was collected through a mail survey that aimed to identify where the target audience was in stages of behavior change. Objectives for the campaign were identified as:

- Employ partnerships

- Saturate the Boomburb market with the campaign messages

- Employ free and paid media

- Conduct on-site events at retail stores, schools, festivals, etc.

- Conduct pre- and post-campaign research

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS). (2005). A report of the “is it done yet? Social marketing campaign to promote the use of food thermometers. U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service. National Food Safety & Toxicology Center at Michigan State University. Michigan State University Extension. Michigan Department of Agriculture (Funding Provider for Michigan).

Utilize behavior theories

Using a theoretical framework for understanding how and why individuals engage in behaviors can be useful to identify what questions to ask in your needs assessment and to identify effective strategies to use to design and implement your program. Behavior theories can also help you narrow down your evaluation approach and the main questions you want to answer to determine the impact and outcomes of your program.

Below are examples of two behavior theories that have previously been applied to consumer food safety studies:

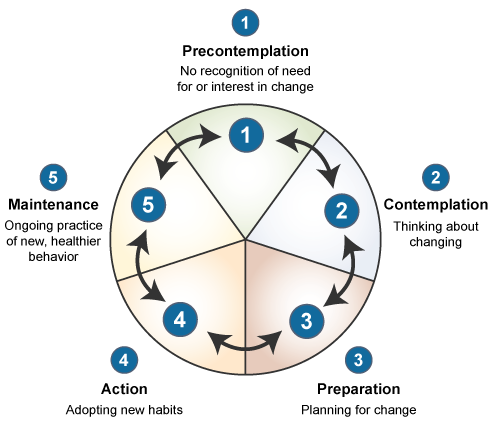

Transtheoretical Model

The Transtheoretical model, or stages of change theory, provides a framework for the stages an individual can experience before successfully changing behavior [23]. There are five stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action and maintenance.

Precontemplation - when an individual is not at all thinking about changing behavior and may be unaware of the consequences of their actions [14,24]

Contemplation - when an individual has not taken any action yet but is seriously considering changing their behavior in the next six months [14,24]

Preparation - when an individual is preparing to make a behavior change within one month [14,24]

Action - when an individual has been successful and consistent in engaging in the new behavior in a one to six month time period [14,24]

Maintenance - when an individual has engaged in behavior change for six or more months [24]

The Transtheoretical or Stages of Change Model [Source]

Understanding what stage of change your target audience is in can be valuable in determining how to strategically communicate with them. For example, the needs of individuals that are in the precontemplation stage and not at all thinking about food safety might be different from individuals in the preparation stage. For those who are in the precontemplation stage you might need to put a greater on emphasize why safe food handling behaviors is important in the first place. Individuals in the contemplation stage may already understand why food safety is important and might require more support in terms of encouragement or helpful tools teaching them how to adopt the new behavior.

Other key constructs of the Transtheoretical Model are decisional balance, or what individuals perceive are the pros and cons of engaging in a specific behavior, and self-efficacy, how confident the individual is in their ability to engage in the behavior [1,24]. Exploring these constructs can help you understand more about your target audience, their beliefs related to consumer food safety, and how to best promote safe food handling practices to the group.

How They Did It

To examine the impact of a food safety media campaign targeting young adults, college students from five geographically diverse universities were recruited to participate in a pre and post-test and a post test only evaluation. Recruitment efforts included Facebook flyers, ads in the school newspaper, and announcements made in student listservs and in class. The objective of the evaluation was to find the campaigns impact related to food safety self-efficacy, knowledge, and stage of change. Stage of change, a construct from the Transtheoretical model, was assessed using a questionnaire item asking participants to identify what statement best described their stage of change related to food handling. Response options included:

1. I have no intention of changing the way I prepare food to make it safer to eat in the next 6 months (precontemplation).

2. I am aware that I may need to change the way I prepare food to make it safer to eat and am seriously thinking about changing my food preparation methods in the next 6 months (contemplation).

3. I am aware that I may need to change the way I prepare food to make it safe to eat and am seriously thinking about changing my food preparation methods in the next 30 days (preparation).

4. I have changed the way I prepare food to make it safe to eat, but I have been doing so for less than the past 6 months (action).

5. I have changed the way I prepare food to make it safe to eat, and I have been doing so for more than the past 6 months (maintenance).

Abbot, J.M., Policastro, P., Bruhn, C., Schaffner, D.W., & Byrd-Bredbenner C. (2012). Development and evaluation of a university campus-based food safety media campaign for young adults. Journal of Food Protection, 75(6)

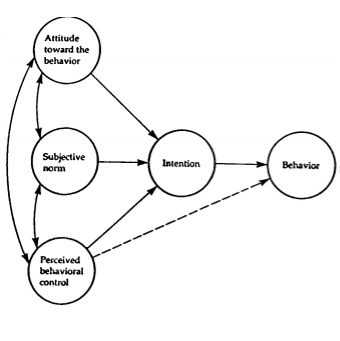

Theory of Planned Behavior

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) provides another framework for understanding behavior. The TPB is founded on three constructs that influence an individual’s intention to engage in a particular behavior. They are: attitudes towards a specific behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, or the perceived ability to make a behavior change or carry out a specific action [2,3].

By focusing on intent we can understand the motivational factors that influence behaviors [3]. In general, the stronger a person’s intent to engage in a specific behavior, the more likely he/she will engage in the behavior, [3]. Intent is influenced by attitudes, which develop as a result of personal beliefs related to a particular behavior [3,12]. A more positive or favorable attitude towards a behavior can result in greater motivation or intent to engage in the behavior [3]. Normative beliefs and subjective norms, also influence intent, because individuals are often concerned about whether or not friends, family or others within their social circle, would disapprove or approve their engagement in a particular behavior [3].

An individual must also have the necessary resources and opportunity to actually engage in the particular behavior. Behavioral control and self-efficacy can be used as predictors of successful behavior change [3]. A person must not only have motivation and intention to make a behavior change, he/she must also have the actual capabilities to make the change and perceive that he/she has the capabilities to successfully make carry out the behavior in question.

The Theory of Planned Behavior Framework [3]

Exploring these constructs can help you understand your target audience’s intentions to engage in safe food handling practices, as well as whether or not, and how, they are motivated to do so. Understanding specific factors related to attitudes, norms, and perceived behavior control can provide insight into what strategies may be effective in motivating your target audience’s intentions to adopt safe food handling behaviors.

Identify core activities and messages

Once you have conducted your research and needs assessment to identify your target audience and the food safety behaviors you will focus on, you can start identifying the main elements of your program, such as what kinds of messaging and activities you will create and implement, and where the program will take place.

Identify program activities.

Taking into account your resources and the needs and interests of your target audience, think about what kinds of strategies and activities will be most effective to achieve your education objectives. Consider using more than one education method to maximize reach and the quality of your program [9]. Most common education approaches in consumer food safety today include educational experiences that are interactive and hands on and mass media/ social marketing campaigns that utilize multiple media channels and target a specific geographic location [30].

Below are ideas of consumer food safety education activities you could implement:

Hold a free food safety workshop presentation for parents at a local library or community center. Work with local schools to send out invites and provide onsite childcare to encourage participation.

Reach out to primary care physicians and figure how to best inform their patients about food safety. Provide educational messages and materials such brochures for them to hand out to their patients.

Meet with teachers and school administrators and inform them of the importance of consumer food safety. Provide them with educational resources they can share with their students and work with them to incorporate food safety education in school curriculums.

Develop a social marketing campaign with core messages that address the specific needs and knowledge gaps of your target audience (identified in the needs assessment). Work with local partners and stakeholders to support you in sharing and disseminating the messages.

Hold a food safety festival for parents and children during National Food Safety Month in September. Plan interactive activities that are hands on and educational.

Partner with local grocery stores and work with them to provide educational messages in their grocery stores.

Encourage work places to send weekly newsletters to employees on food safety topics, or create fun and educational food safety competitions [30].

Selecting a setting for your program can also help you narrow down and choose program activities. In this approach you would: select the setting for your program → conduct a needs assessment for the community within that setting → identify appropriate activities and strategies. Examples of settings for consumer food safety education activities include schools, public restrooms, health fairs, workplaces, and grocery stores.

For more consumer food safety education activity ideas, refer to the White Paper on Consumer Research and Food Safety Education (DRAFT).

Identify communication/delivery strategies and core messages

In your needs assessment, consider including questions that can help you identify how your target audience seeks out health information, what media channels they have access to, and what sources they find to be credible and trustworthy. This information is key to ensure that educational messages are heard and trusted.

Potential delivery channels [30]:

Traditional media (print, audio, video)

“New” media (internet, social media, video games, computer programs)

Mass media/social marketing

Classroom-style lessons

Interactive and hands-on activities

Visual cues or reminders

Community events and demonstrations

Crafting Your Message

When crafting food safety messages think about what you want people to know and what the primary purpose of your message is. There are three different types of messages you could use to influence food safety behavior [adapted 5]:

Awareness messages increase awareness about what people should do to prevent foodborne illness, who should be doing it, and where people should engage in safe food handling practices. A key role of this type of message is to increase interest in the topic of food safety and to encourage people to want to find out more about how to prevent foodborne illness.

Instruction messages provide information to increase knowledge and improve skills on how to adopt new safe practices to prevent foodborne illness. These types of messages can also provide encouragement or support if people lack confidence in engaging in the new behavior.

Persuasion messages provide reasons why the audience should engage in a new food handling behavior. This usually involves influencing attitudes and beliefs by increasing knowledge about food safety and foodborne illness.

When crafting a persuasive message to encourage consumers to adopt a new behavior there are three things you should think about: credibility, attractiveness, and understandability. It is important that your target audience finds your messages to be [5]:

Credible, accurate and valid. This is normally done by demonstrating you are a trustworthy and competent source and providing evidence that supports your message.

Attractive, entertaining, interesting, or mentally or emotionally stimulating. Consider providing cues to action messages that are eye catching, quick and easy to read, and include some amount of shock value [18].

Understandable, simple, direct, and with sufficient detail.

Use appeals and incentives [25]

Your message should include persuasive appeals or incentives to motivate the target audience to change their behaviors. These can be can positive or negative incentives. Examples of negative incentives include inciting fear of the consequences of foodborne illness or negative social incentives such as not being a responsible care taker or cook for the family. Positive appeals demonstrate the positive outcomes for adopting new food safe practices, such as addressing strong physical health or being a good role model to family and friends. Using a combination of both positive and negative incentives can be a good strategy to influence different types of individuals. This is because it is probable that not all individuals of your target audience will be motivated by negative incentives, and not all by positive incentives.

Consider timing

The timing of when to disseminate messages is also an important factor to consider. Think about national or community events taking place that might peak the target audience’s interest in food safety and help you maximize the effectiveness or reach of your messages. For example, national health observances such as National Food Safety Month or National Nutrition Month, might provide a great opportunity to promote your program or to share educational food safety information. The opening of a new grocery could also a good opportunity to promote food safety. Your organization or program could partner with store owners and staff to provide food safety information during their grand opening and display food safety messages throughout the store.

Don’t reinvent the wheel

When developing core messages and educational materials you don’t always have to reinvent the wheel. Utilize science and evidence based materials that have already been created for consumer food safety education, such as resources developed by the Partnership for Food Safety Education on the four core food safety practices.

Fight BAC! Four Core Practices [Source]

Other food safety education materials you can use:

For consumers: Food Safe Families, Be Food Safe, Cook It Safe

For schools: Science and our Food Supply , Hands On

If you decide to use existing materials don’t forget to think about your target audience and how you may want to refine messages or materials to best serve their needs and interests. You should also take health literacy and cultural sensitivity into account.

Health literacy

Health literacy refers to a person’s ability to access, understand, and use health information to make health decisions. About 9 out of 10 adults have difficulty using everyday health information available to them, such as those in health care facilities, media, and through other sources in their community [10,20,26,28].

Things to consider:

Incorporate a valid and reliable health literacy test, such as the Newest Vital Sign by Pfizer, in your needs assessment to help you understand the health literacy levels of your target audience.

Use plain, clear, and easy to understand language when writing educational consumer food safety information.

Think of creative formats to share food safety messages such as video, multi-media, and infographics.

Make sure messages are accurate, accessible, and actionable [7].

Avoid medical jargon, break up dense information with bulleted lists, and leave plenty of white space in your documents.

Use helpful tools such as the CDC’s Clear Communication Index and Everyday Words for Public Health Communication the Health Literacy Online Checklist to create and refine your content.

When in doubt write at a 7th or 8th grade reading level or below [19].

Conduct a pilot test of materials with representatives from the target audience to ensure that they are easy to understand and use.

Cultural sensitivity

When working with diverse or ethnic populations it is important to be culturally sensitive in your approach, interactions, and when creating educational content.

Things to consider:

It is not only important for you to translate food safety messages into another language when needed, but also to provide tailored information, examples, and visuals that are culturally relevant and appropriate [22].

Take into account cultural beliefs, norms, attitudes, and preferences related to health and food safety.

Work closely and collaborate with the target population to ensure you are addressing their specific needs [22].

Hire members from the community with cultural backgrounds similar to your target population to help with recruiting, administering interviews, or facilitating focus groups to ensure that the data collection process is culturally sensitive and respectful [16,13,27].

Request staff or colleagues with cultural backgrounds similar to target audience to review materials and messages for content that might include cultural assumptions or prejudice [16].

More communication tips

A few more tips for communicating consumer food safety information [30]:

Make your messages specific to the target audience and address any food safety misconceptions the target audience may have.

Provide powerful visual aids to help consumers visualize contamination. Use storytelling and emotional messaging to convey the toll of foodborne illness.

Link temporal cues with food safety. For example, help consumers associate running their dishwasher with sanitizing their sponge.

References

Armitage, C. J., Sheeran, P., Conner, M., & Arden, M. A. (2004). Stages of change or changes of stage? Predicting transitions in transtheoretical model stages in relation to healthy food choice. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 491–499.

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckman (Eds.), Action-control: From cognition to behavior, 11–39.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Bemis, K. M., Marcus, R., & Hadler, J. L. (2014). Socioeconomic status and campylobacteriosis, Connecticut, USA, 1999-2009. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 20(7).

Borrusso, P., & Das, S. (2015). An examination of food safety research:

implications for future strategies: preliminary findings. Partnership for Food Safety Education Fight BAC! Forward Webinar.Cates, S., Blitstein, J., Hersey, J., Kosa, K., Flicker, L., Morgan, K., & Bell, L. (2014). Addressing the challenges of conducting effective supplemental nutrition assistance program education (SNAP-Ed) evaluations: a step-by-step guide. Prepared by Altarum Institute and RTI International for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service.

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2016). Health literacy: develop materials. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/developmaterials/index.html

Consumer Federation of America (CFA). (2013). Child Poverty, Unintentional Injuries, and Foodborne Illness: Are Low-Income Children at Greater Risk?

Gabor, G., Cates, S., Gleason, S., Long, V., Clarke, G., Blitstein, J., Williams, P., Bell, L., Hersey, J., & Ball, M. (2012). SNAP education and evaluation (wave I): final report. Prepared for U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Research and Analysis. Alexandria, VA.

Kutner, M., Greenberg, E., Jin, Y., & Paulsen, C. (2006). The health literacy of America’s adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006-483). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2015). Food Safety: it's especially important for at-risk groups. Retrieved from: http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodborneIllnessContaminants/PeopleAtRisk/ucm352830.htm

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, 1. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison—Wesley.

Fisher, P.A., & Ball, T. J. (2002). The Indian family wellness project: An application of the tribal participatory research model. Prevention Science, 3.

Horwath, C. C. (1999). Applying the transtheoretical model to eating behaviour change: challenges and opportunities. Nutrition Research Reviews, 12, 281–317.

Issel L. (2004). Health Program Planning and Evaluation: A Practical, Systematic Approach for Community Health. London: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

McDonald, D. A., Kutara, P. B. C., Richmond, L. S., & Betts, S. C. (2004). Culturally respectful evaluation. The Forum for Family and Consumer Issues, 9(3).

McKenzie J. F, & Smeltzer J. L. (2001) Planning, implementing, and evaluating health promotion programs: a primer, 3rd ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Meysenburg R, Albrecht J., Litchfield, R., & Ritter-Gooder, P. (2013). Food safety knowledge, practices and beliefs of primary food preparers in families with young children. A mixed methods study. Appetite, 73, 121-131.

National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S National Library of Medicine, MedlinePlus. (2016). How to write easy-to-read health materials. Retrieved from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/etr.html

Nielsen-Bohlman, L., Panzer, A. M., & Kindig, D. A. (Eds.). (2004). Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

O'Connor-Fleming, M. L., Parker, E. A., Higgins, H. C., & Gould, T. (2006) A framework for evaluating health promotion programs . Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 17(1).

Po, L. G., L. D. Bourquin, L. G. Occeña, and Po, E. C. Po. (2011). Food safety education for ethnic audiences. Food Safety Magazine. 17:26-31.

Prochaska, J. O. (2008). Decision making in the transtheoretical model of behavior change. Medical Decision Making, 28, 845–849.

Prochaska, J.O. , Redding, C.A., & Evers, K. E. (2008). The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In Health behavior and health education theory, research and practice (97-121). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Rice, R. E., & Atkin, C. K. (2001). Public Communication Campaigns. London: Sage publications.

Rudd, R. E., Anderson, J. E., Oppenheimer, S., & Nath, C. (2007). Health literacy: An update of public health and medical literature. In J. P. Comings, B. Garner, & C. Smith. (Eds.), Review of adult learning and literacy, 7, 175–204. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Stubben, J.D. (2001). Working with and conducting research among American Indian families. American Behavioral Scientist, 44.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2010). National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. Washington, DC.

Whitney, B. M., Mainero, C., Humes, E., Hurd, S., Niccolair, L., & Hadler, J. L., (2015). Socioeconomic status and foodborne pathogens in Connecticut, USA, 2001-2011. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 21(9).

White Paper on Consumer Research and Food Safety Education. (DRAFT).

Chapter 3: Mapping the Intervention and Evaluation

Steps for a program evaluation

There are six evaluation steps to think about as you plan your intervention and evaluation. The evaluation steps are: 1. Engage stakeholders 2. Describe the program 3. Focus the evaluation design 4. Gather credible evidence 5. Justify conclusion 6. Ensure use and share lessons learned [2]. The next chapters will go through these steps in more detail but it is helpful to have a framework or overview to think about before you begin planning. Applying the Utility, Feasibility, Accuracy, and Propriety evaluation standards discussed in the first chapter to these steps can help ensure that your evaluation is rigorous and thorough.

Evaluation steps and standards [2]

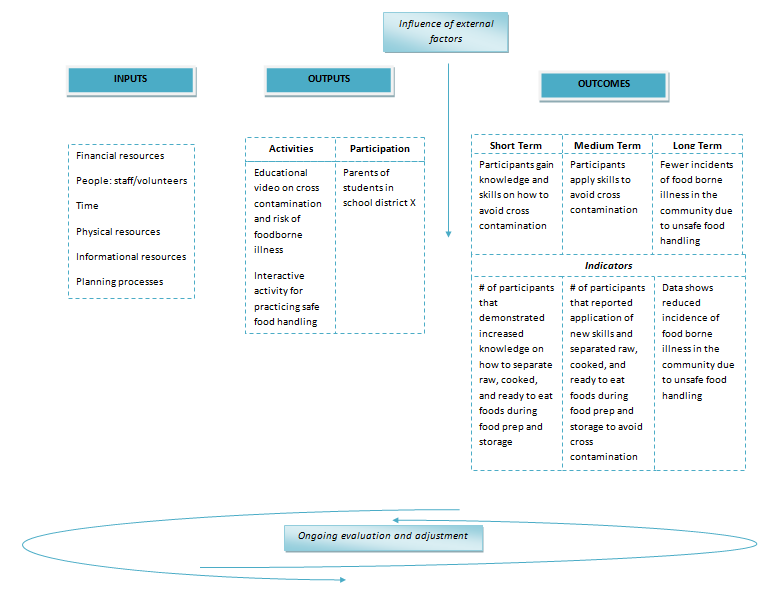

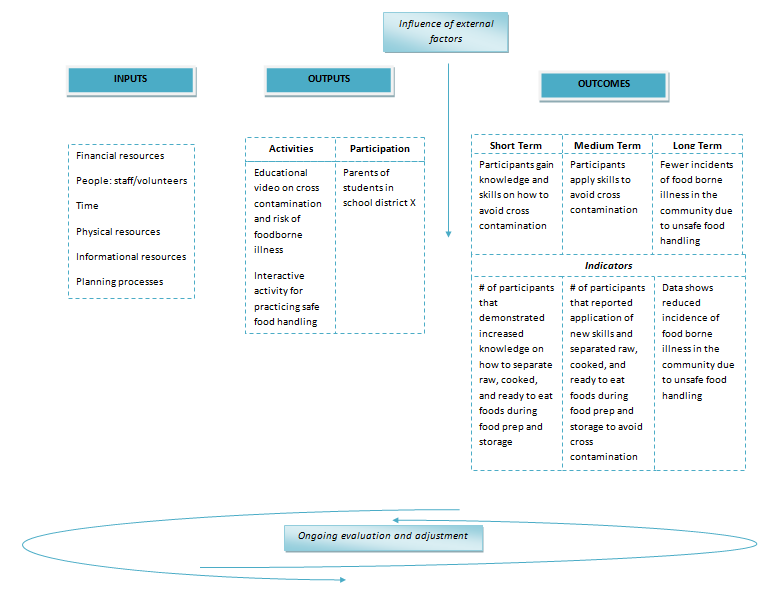

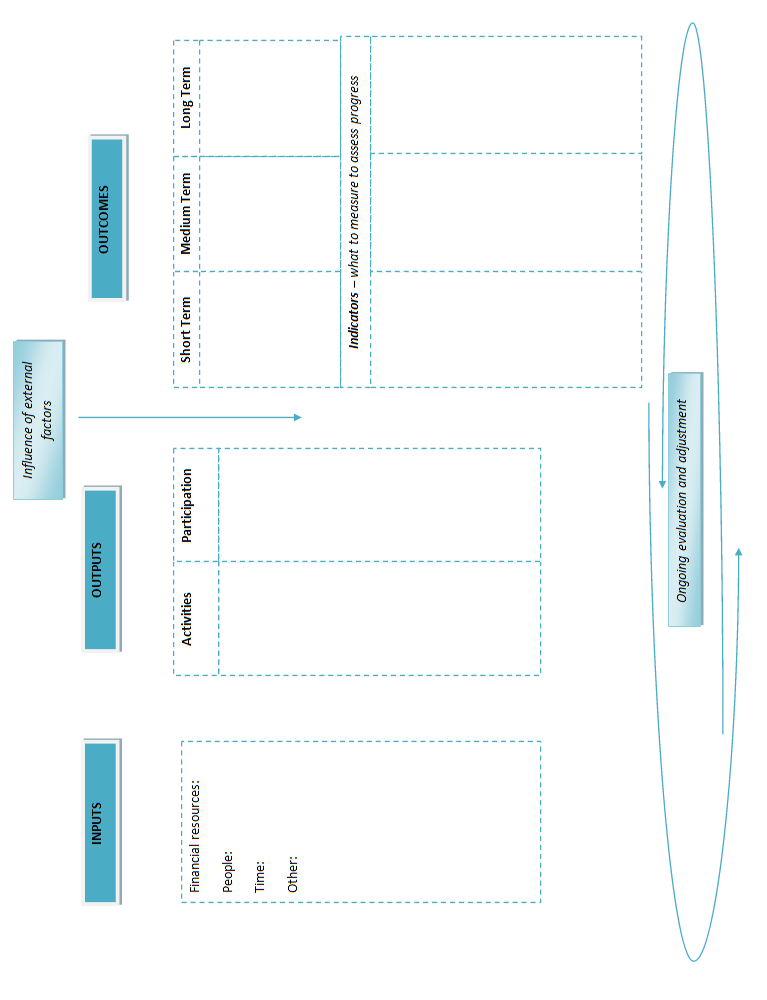

Create a logic model

Creating a logic model can help you describe your program by identifying program priorities, mapping out the components of your program, and understanding how they are linked. A logic model can also help you identify short, medium, and long term outcomes of the program and figure out what to evaluate and when. A logic model can also assist program staff, stakeholders, and everyone else involved with implementation and evaluation, in being aware of the overall framework and strategy for the program.

A logic model generally includes inputs (e.g. resources, materials, staff support), outputs (e.g. activities and participation), and outcomes (short, medium, and long term). As you pinpoint program outcomes you should also identify corresponding indicators. An indicator is the factor or characteristic you need to measure to know how well you are achieving your outcome objectives. Identifying outcome indicators early in the planning process can help clarify program priorities and expectations.

There is no one way to create a logic model. You may decide to make one model for your entire program, or multiple models for each program activity. Make it your own and remember to take into account the needs of your target audience, the program setting, and your resources.

Below is an example of a logic model created for a program aiming to reduce foodborne illness due to cross contamination of foods – [adapted 11,12]. You can create your own logic model using a template provided in Chapter 7.

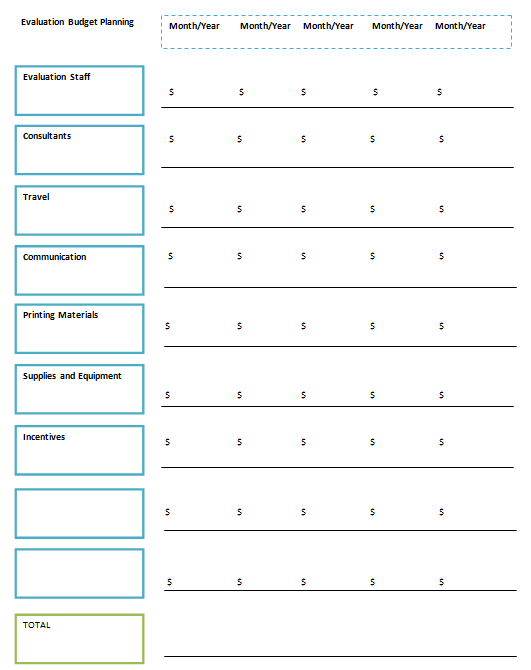

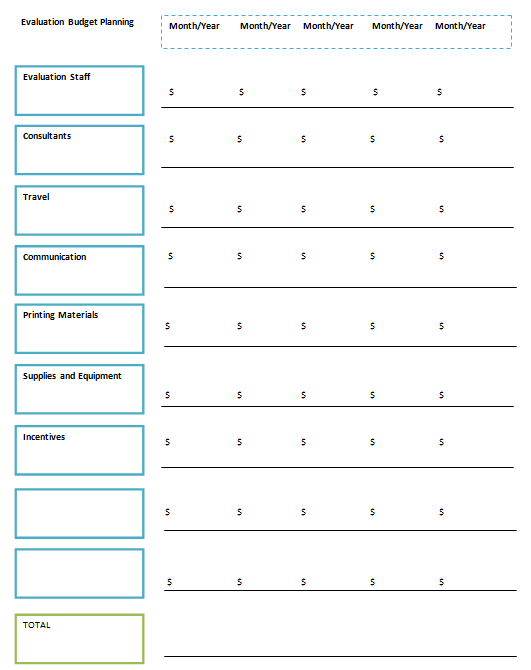

Budget

When planning and deciding your program budget make sure you take evaluation costs into account. The general recommendation is to use 10% of program funding for evaluation [13]. Your budget can be flexible and you should review it overtime to adjust if needed [15]. Document your spending and keep track of expenses. You should also track and take inventory of program supplies and materials so that you don’t purchase more than needed and can reduce waste and maximize efficiency. You may find it helpful to designate a team member to keep track of spending and funds.

Use the template below to help plan your budget [adapted 15]. You can also use it to keep track of your spending.

Levels of assessment

There are generally seven incremental assessment levels in a program evaluation that you should consider depending on the applicability of each level to your evaluation needs [5,10]. They are:

Inputs such as staff and volunteer time, monetary resources, transportation, and program supplies, required to plan, implement, and evaluate the program.

Educational and promotional activities targeting the target audience. Includes activities with direct contact to more indirect methods such as mass media campaigns.

Frequency, duration, continuity, and intensity of participation or people reached.

Positive or negative reactions, interest level, and ratings from participations about the program. Can include feedback on program activities, program topics, educational methods, and facilitators.

Learning or Knowledge, Attitude, Skills, and Aspiration (KASA) changes. These changes can occur as a result of positive reactions to participation in program activities.

New practice, action, or behavior changes that occur when participants apply new Knowledge, Attitude, Skills, and Aspiration (KASA) they learned in the program.

Impact or benefits from the program to social, economic, civil, and environment conditions.

Each level addresses important elements you can evaluate to understand the impact and outcomes of your program, as well program strengths and challenges.

The below table displays examples of outcomes and indicators for each of the seven assessment levels. The examples are based on a program aiming to reduce foodborne illness due to cross contamination of foods.

Assessment Level |

Goal/Target Outcomes |

Indicators |

Inputs |

400 total hours of staff and volunteer time, 500 copies of educational brochures are printed and distributed |

Time sheet is completed by staff/volunteers and documents the assignments produced or worked on. A spreadsheet that documents printing and distribution of brochures and other materials is also complete. |

Activities |

Needs assessment, focus groups to finalize program materials and messaging, educational workshop for parents on cross contamination and safe food handling (video and interactive activity) |

Frequency, duration, methods, and content of program activities are documented and reported on |

Participation |

Target quota for participation filled (n=100), workshop members consist of target audience (parents in school district X), participants stay for the entire duration of the workshop |

Participant sign in/sign out sheet for workshop is filled out. Sheet documents the time participant signs in and out and whether or not participant has a child that is a student in school district X |

Reactions |

Participants find the workshop content and facilitators to be engaging and find the information to be relevant and important to them |

Brief follow up survey for participant feedback. Participants provide a high rating level for factors such as topic area, workshop facilitation, workshop format, and content |

Learning or Knowledge, Attitude, Skills, and Aspiration (KASA) |

Participants gain knowledge and skills on how to avoid cross contamination |

# of participants that demonstrated increased knowledge on how to separate raw, cooked, and ready to eat foods during food prep and storage |

Actions or behavior |

Participants apply skills to avoid cross contamination |

# of participants that reported application of new skills and separated raw, cooked, and ready to eat foods during food prep and storage to avoid cross contamination |

Impact |

Fewer incidents of food borne illness in the community due to unsafe food handling |

Data shows reduced incidence of food borne illness in the community due to unsafe food handling |

Create a timeline

Create a timeline to display important implementation and evaluation activities and specify when they need to be completed. This timeline can change overtime but it is important for you and other staff and partners to pre-plan and share a common understanding of when important tasks need to be accomplished.

Below is an example of a simple timeline for a year long project and evaluation, using a Gantt Chart. The chart displays important tasks that need to be accomplished, the durations for each task, when they begin and end, and how some tasks overlap with each other.

Project Activity |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

Form a planning/evaluation team and invite partners |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Research on topic/target audience |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Implement needs assessment |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Report needs assessment findings |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Create a logic model, plan out activities, evaluation, and budget |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Focus groups for feedback on program materials/messages |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conduct a pre-test |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Preliminary analysis of pre-test data |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Train staff and volunteers |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Implement workshop |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Post-test follow up round 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Post-test follow up round 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Data analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

Evaluation report/ disseminate findings |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

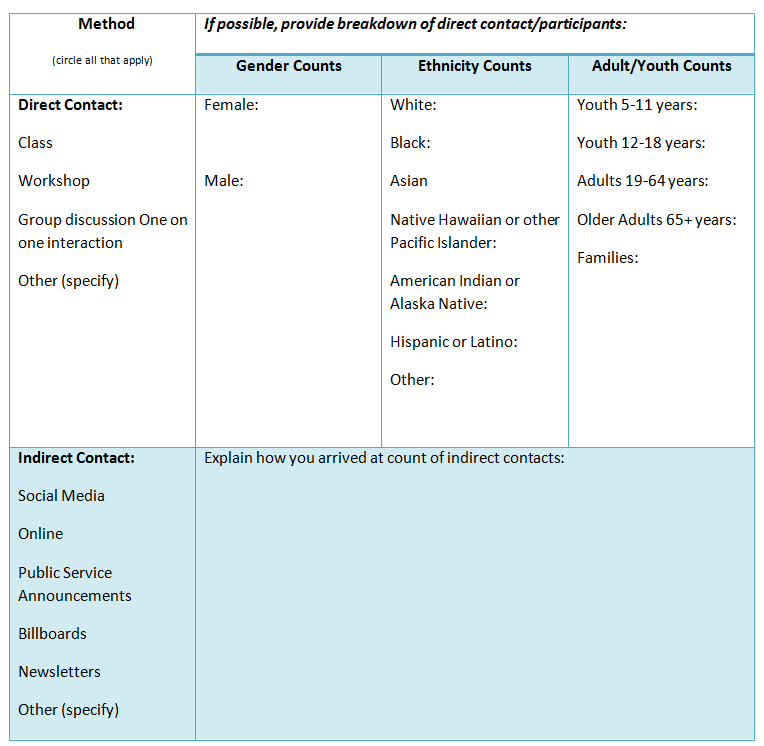

Process evaluation

The first three levels of assessment related to program inputs, activities, and participation are generally referred to as a process evaluation. A process evaluation is usually ongoing and tells you whether program implementation is continuing as planned [9]. It can also help you figure out what activities have the greatest impact given the cost expended [1]. A process evaluation often consists of measuring outputs such as staff and volunteer time, the number of activities, dosage and reach of activities, participation and attrition of direct and indirect contacts, and program fidelity. A process evaluation can also involve finding out:

If you are reaching all the participants or members of the target audience [9].

If materials and activities are of good quality [9].

If all activities and components of the program are being implemented [9].

Participant satisfaction with the program [3,4,8,9].

Program fidelity refers to whether or not and to what extent the implementation of the program occurs in the manner originally planned. For example, whether or not staff follow standards and guidelines they receive in a training, whether an activity occurs at the pre-determined location and duration, or whether or not educators stick to the designated curriculum when teaching consumer food safety education.

Below are examples of how to assess program fidelity:

Develop and provide training on the standards for data collection, and management. Check in overtime to ensure standards are met.

Evaluate program materials to make sure they are up-to-date and effective.

Evaluate facilitators or educators to make sure they are up-to-date, knowledgeable, enthusiastic, and effective.

Hold regular staff trainings and team meetings and track activities (you can use the Activity Tracker Form in Chapter 7) to gather feedback on implementation of program activities, learn about implementation challenges and how to address them, and provide support to staff, volunteers, and educators.

During the planning phase of your program, it may be helpful to create a spreadsheet template to document program inputs and outputs. Consider providing a form (such as the activity tracker form in Chapter 7) to staff to ensure they keep track of important and relevant information. You should also set up a time or schedule for when staff are required to submit completed forms.

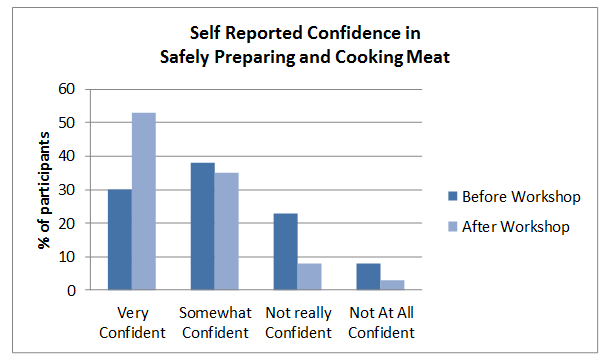

Outcome Evaluation

The last few levels of assessment related to changes to KASA, behaviors, or the environment, are generally part of an outcome evaluation. As discussed in the logic model section, you may want to identify three outcomes for your program, short term, medium term, or long term. When determining outcome objectives make sure they are SMART [1,7]:

Specific – Identify exactly what you hope the outcome to be and address the five W’s: who, what, where, when, and why.

Measurable – quantify the outcome and that amount change you aim for the program to produce.

Achievable – be realistic in your projections and take into account assets, resources, and limitations.

Relevant – make sure your objectives address the needs of the target audience and align with the overarching mission of your program or organization.

Time-bound – provide a specific date by which the desire outcome or change will take place.

Examples of SMART outcomes:

At least 85% of participants in the Food Safe workshop will learn at least two new safe practices for cooking and serving food at home by August 2016.

80% of food kitchen volunteers will wash their hands before serving food kitchen meals after completing the final day of the handwashing training on October 2nd, 2016.

70% of children enrolled in the Food Safety is Fun! summer camp will be able to identify the four core practices of safe food handling and explain at least one consequence of foodborne illness by the end of summer.

Examples of food safety factors you may wish to measure and address in your outcome objectives include: knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, and other influential factors such as visual cues or reminders, resources, convenience, usual habits, perceived benefits, taste preferences, self-efficacy or perceived control, and perceived risk or susceptibility [14].

Purpose of the evaluation

As you think about and plan your evaluation, make sure you can clarify the purpose of the evaluation and what kind of information you want to find out. To do this, think about who will use the evaluation data, what it will be used for, and how other stakeholders and partners will use the evaluation findings [13].

Below are examples of questions you might want to ask to help clarify the purpose of the evaluation:

Do we need to provide evaluation data to funders to show that the benefits of the program outweigh the costs?

Do we need to understand whether the program strategies used are effective in producing greater knowledge about food safety and positive behavior changes?

Do we want to figure out whether the educational format and strategies we used can be a successful model for other educators to incorporate in their programs?

Identifying what overarching questions need to be answered, who the evaluation is for and how it will be used, will help you figure out what exactly you need to evaluate and how.

References

Cates, S., Blitstein, J., Hersey, J., Kosa, K., Flicker, L., Morgan, K., & Bell, L. (2014). Addressing the challenges of conducting effective supplemental nutrition assistance program education (SNAP-Ed) evaluations: a step-by-step guide. Prepared by Altarum Institute and RTI International for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service.

Community Toolbox. (n.d). Evaluating programs and initiatives: section 1. A framework for program evaluation: a gateway to tools. Retrieved from: http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/evaluate/evaluation/framework-for-evaluation/main

Hawe P, Degeling D, & Hall J. (2003). Evaluating Health Promotion: A Health Workers Guide. Sydney: MacLennan and Petty.

Issel L. (2004). Health Program Planning and Evaluation: A Practical, Systematic Approach for Community Health. London: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Kluchinski, D. (2014). Evaluation behaviors, skills and needs of cooperative extension agricultural and resource management field faculty and staff in new jersey. Journal of the NACAA, 7(1).

Little, D., & Newman, M. (2003). Food stamp nutrition education within the cooperative extension/ land-grant university system national report – FY 2002. Prepared for United States Department of Agriculture Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service Families, 4-H, and Nutrition Unit. Washington, D.C.

Meyer, P. J. (2003). What would you do if you knew you couldn’t fail? Creating S.M.A.R.T. Goals. Attitude is everything: If you want to succeed above and beyond. Meyer Resource Group, Incorporated.

Nutbeam D. (1998). Evaluating health promotion--progress, problems and solutions. Health Promotion International, 13(1).

O'Connor-Fleming, M. L., Parker, E. A., Higgins, H. C., & Gould, T. (2006) A framework for evaluating health promotion programs . Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 17(1).

Rockwell, K., & Bennett, C. (2004). Targeting outcomes of programs: a hierarchy for targeting outcomes and evaluating their achievement. Faculty Publications: Agricultural Leadership, Education & Communication Department. Paper 48.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA). (n.d). Community nutrition education (CNE) – logic model detail.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA). (n.d). Community nutrition education (CNE) – logic model overview.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2011). Office of the Director, Office of Strategy and Innovation. Introduction to program evaluation for public health programs: A self-study guide. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

White Paper on Consumer Research and Food Safety Education. (DRAFT).

W. K. Kellogg Foundation. (2004). Evaluation handbook. MI.

Chapter 4: Selecting an Evaluation Design

Observational and experimental designs

An evaluation design is the structure or framework you decide to use to conduct your evaluation. There are two main types of evaluation designs: observational and experimental.

An observational study is a non-experimental design in which participants are not pre-assigned whether they will participate in the program (control group) or not (comparison group).

An experimental study involves an intentional assignment of who will be in control group and who will be in the comparison group. This allows the evaluator to alter the independent variable (the program or activity) and be able to control external factors that influence the outcome variable. Experimental designs are not always easy to implement in real life, but are the best option for reducing internal threats to validity.

When to collect data

Deciding when to collect evaluation data is an important part of selecting an evaluation design. To collect data you could:

Collect data only one-time, usually in a post-test. A post-test is when you collect data after the program or intervention.

Conduct a pre-post test where you collect data before and after the program takes place.

Collect data multiple times throughout the evaluation process.

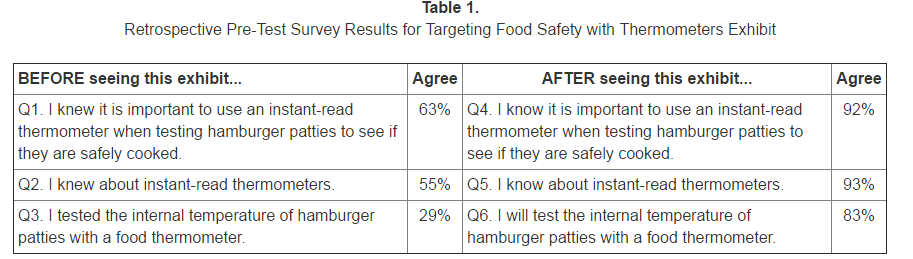

Conduct a retrospective pre-test that is administered at the same time as the post test.

More information about the benefits and limitations of each of these options will be listed in the table on the following page.

Internal validity

When deciding how to design your evaluation and when to collect data it is important to think about minimizing threats to internal validity that could bias your data and evaluation findings. Internal validity refers to the extent to which you can ensure or demonstrate that external factors other than the independent variable, or your program, did not influence the outcome variables. This can influence how true or accurate your findings and conclusions are so it is important to protect against internal validity threats to ensure your evaluation is sound and reliable.

Below are descriptions and examples of different types of threats to internal validity:

Maturation occurs when participants have matured or developed mentally or emotionally throughout the evaluation process, and this influences the outcome variable.

Example: Kids perform better on a post-test foodborne pathogens quiz than on the pre-test simply because they are older and have become better test-takers, not because of the new food safety curriculum at their school (education program/independent variable).

History threats happen when events that have taken place in the participants’ lives throughout the program or evaluation process which influence the outcome variable.

Example: Participants score high on a household audit because most of them recently watched a documentary on the consequences of foodborne illness, not because of the “Food Safety at Home Reminders” magnet they received in the mail.

Testing effect occurs when the participants’ post-test data is influenced by their experience of taking the pre-test.

Example: Participants’ understanding about the importance of separating raw meat, poultry, seafood, and eggs from other foods in their shopping cart improved in the post-test because of being exposed to that information in the pre-test, not because they read new signage on cross contamination in their local grocery store.

Instrumentation takes place when data on the outcome variable is influenced by differences in the way the pre-test and post-test assessments are administered or collected. Pre-test and post-test assessments need to be the same to prevent instrumentation from occurring.

Example: Participants more positively describe their safe food handling practices in the post-test interview because of the way the new interviewer described and interpreted the questions, not because a new training program encouraged them to adopt new safe food handling practices at home.

Recall bias takes place when participants do not accurately remember events they have experienced in the past and this influences the accuracy of the data collected.

Example: Participants do not remember how long they generally take to wash their hands so they guess a number of seconds that is inaccurate. The finding that most participants wash their hands for at least 20 seconds is due to participants incorrectly recalling how long they wash their hands, not due to them reading new handwashing messages posted all over social media.

Social desirability bias occurs when participants provide responses they believe will be pleasing to the interviewer and will make them seem more favorable. This often leads to over reporting of behaviors or information that participants believe are positive or “good” and an under reporting of behaviors or information participants believe are negative or “bad.”

Example: In one on one interviews participants share that foodborne illness is of great concern to them and that they always try their best to practice safe food handling practices at home because they want to impress the interviewer and think that is the “correct” answer, not because it is actually true.

Attrition bias happens when a loss of participants in the control or comparison group, influences the evaluation data. Attrition can be due to reasons such as loss in follow up, death, or moving away.

Example: The control group loses about a third of participants for the post-test survey and this negatively impacts the overall knowledge testing score on safe storage of foods. As a result, change in score is mostly not related to the educational video that participants watched.

Selection bias occurs when differences in the data collected from the control and comparison group are due to differences between the individuals in each group, not because one group participated in the program and the other did not.

Example: Participants in the control group demonstrate greater motivation to adopt safe cooking practices at home because the group is comprised of more risk averse personalities, not because the control group was exposed to interactive TV ads on safe cooking.

Use of a comparison/control group

One way to protect your evaluation from validity threats is to use a comparison or control group of individuals who do not participate in the program, to compare to participants who do participate in the program.

The best way to choose a control group and prevent selection bias is to randomly choose who will participate in the program and randomly choose who will be in the control group and not participate in the program. This is called random assignment and through this method both groups will be theoretically alike.

If random assignment is not possible you can collect demographic information about individuals in each group in the evaluation so that when analyzing data you can adjust for differences between each group [2]. Remember, the longer you wait before collecting data after the program or intervention, the more likely it is that both groups will regress towards the mean and have fewer differences in regards to the outcome variable [2]. When possible it is best to collect your post-test data not long after the program is implemented.

How They Did It

To evaluate the effectiveness of web-based and print materials developed to improve food safety practices and reduce the risk of foodborne illness among older adults, a randomized control design was used with a sample of 566 participants. 100 participants were in the web site intervention group, 100 in the print materials group, and 100 in the control group. Participants took a web based survey that was emailed to them before the intervention and about 2 months following the intervention.

To measure food safety behavior, participants were asked to report their behaviors when they last prepared specific types of food. To assess perception of risk of foodborne illness, participants were asked to rate agreement to the following statement with a 4 point Likert scale: “Because I am 60 years or older, I am at an increased risk of getting poisoning or foodborne illness.” Participants were also asked about how satisfied they were with the educational materials and about how informative and useful they found them. Overall findings showed insignificant difference in the changes between the control and comparison groups, demonstrating that the materials did not impact food safety behavior.

Kosa, K. M., Cates, S.C., Godwin, S.L., Ball M., & Harrison R. E. (2011) Effectiveness of educational interventions to improve food safety practices among older adults. Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics, 30(4)

Now that you have learned about threats to internal validity, you can weigh out the benefits and limitations of different evaluation designs given your resources and evaluation needs. Below is a table of common evaluation designs and the benefits and limitations of each option [adapted 2]. In general the design options increase in rigor as you go down the table. It is important to note that some of these designs are frequently used to evaluate health programs, but are generally weak in terms of being able to tell you whether change in the outcome variable can be attributed to the program.

Evaluation Design |

Description/Example |

Benefits |

Limitations |

One group post-test only |

-Collect data after implementing the program. Example: You implement a food safety workshop and then hand out a survey before participants leave. |

-Good to use if a pre-test might bias the data collected/findings or when unable to collect pretest/baseline data. -Generally inexpensive. -Easy to understand and for staff with little training to implement. -May be the only design option if you do not plan ahead and decide to evaluate once the program has already begun. |

-Weak design because you do not have baseline data to be able to determine change. -Not very useful in understanding the actual effect of the program. -Examples of potential validity threats: history and maturation because you only have information regarding a single point in time and don’t know if any other events or internal maturation took place to influence the outcome. |

One group, retrospective pre- and post-test |

-Collect both pre and post-test data after implementing the program. The pre-test will involve participants thinking back to their experience before the program. Example: You implement a food safety workshop and then hand out a two part (pre and post) survey before participants leave. |

-Good to use when you are unable to collect traditional pretest/baseline data. -Generally inexpensive. -May be the only design option if you do not plan ahead and decide to evaluate once the program has already begun. -May demonstrate more accurately how much participants feel they have benefited from the program [1]. |

-Without a comparison group this design is not very useful in understanding whether a change in the outcome variable is actually due to the program. -Examples of potential validity threats: Recall bias and social desirability. Social desirability can be more influential in a retrospective pre-test than a traditional pre-test [1]. |

Comparison group post-test only |

-You have a comparison group of individuals that do not participate in the program. Following the program you collect data from the program participants and the comparison group. Example: You implement a food safety workshop and then hand out a survey to participants before they leave. You also give the same survey to individuals in the comparison group who have not participated in the workshop. You later compare survey results of program participants and comparison group. |

-Good to use if a pre-test might bias the data collected or when unable to collect pretest/baseline data. -May be the only design option if you do not plan ahead and decide to evaluate once the program has already begun. -Statistical analysis to compare both groups is fairly simple. |

-Comparison group must be available. -Target audience must be large enough to have both a control and comparison group. -Weak design because you do not have baseline data to be able to determine change and whether differences between groups are actually due to the program. -Example of potential validity threats: selection bias. |

One group pre-post test |

-You collect data before and after the program or intervention takes place. Usually data is linked for each single individual to assess amount of change. Example: You implement a food safety workshop and survey participants before and after they participate in the workshop. A survey knowledge score is calculated for each individual participant to find out if scores improved after participating in the workshop. |

-Able to identify change before and after the program. -Generally easy to understand and calculate. |

-Must be able to collect pre-test/baseline data. -Without a comparison group this design is not very useful in understanding whether a change in the outcome variable is actually due to the program. -Demonstrates greater evaluation rigor and validity when seeking funders or sharing outcome findings with partners than when relying on a single post test or retrospective pre and post test [1]. -Examples of potential validity threats: testing affect and instrumentation. |

One group, repeated measures or time series |

-You collect data more than once before program implementation and at least two more times following intervention, overtime. The optimal number of times to collect data is five times before and after the program, but this will vary depending on your sample and evaluation needs [3]. Example: You implement a food safety workshop and survey participants a few times before and a few times after they participate in the workshop, over the following months. A survey knowledge score is calculated for each time participants took the survey to find out how scores improved after participating in the workshop and how much information was retained over time. |

-Able to identify change before and after the program. -By tracking change repeatedly over time you have a greater opportunity to observe external factors that might influence findings and address threats to internal validity. -Generally beneficial for large aggregates like schools or populations. |

-Must be able to collect pre-test/baseline data. -Examples of potential validity threats: history (major threat), maturation, and instrumentation.

|

Two group pre-post test |

-You collect data from program participants and a comparison group before and after the program takes place. Usually data is linked for each single individual to assess amount of change. Example: You implement a food safety workshop and survey workshop participants and the comparison group before and after the workshop takes place. A survey knowledge score is calculated for each individual participant to find out if or how scores changed and how scores of program participants’ and the comparison group differ. |

-Able to identify change before and after program/intervention. -Statistical analysis to compare both groups is fairly simple. |

-Comparison group must be available. -Target audience must be large enough to have both a control and comparison group. -Must be able to collect pre-test/baseline data. -Demonstrates greater evaluation rigor and validity when seeking funders or sharing outcome findings with partners than when relying on a single post test or retrospective pre and post test [1]. |

Two or more -group time series |