TO29_OMB_Part A_August 2016 08-12-16

TO29_OMB_Part A_August 2016 08-12-16.docx

Study of Title I Schoolwide and Targeted Assistance Programs

OMB: 1875-0280

OMB Clearance Request:

Part A – Justification (DRAFT)

Study

of Title I Schoolwide and

Targeted Assistance Programs

PREPARED BY:

American

Institutes for Research®

1000 Thomas Jefferson

Street, NW, Suite 200

Washington, DC 20007-3835

PREPARED FOR:

U.S. Department of Education

Policy and Program Studies Service

August 2016

OMB

Clearance Request

Part A

August 2016

Prepared

by: AIR

1000 Thomas Jefferson Street NW

Washington, DC

20007-3835

202.403.5000 | TTY 877.334.3499

www.air.org

Contents

Study of Title I Schoolwide and Targeted Assistance Programs 2

Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission 6

1. Circumstances Making Collection of Information Necessary 6

3. Use of Improved Technology to Reduce Burden 7

4. Efforts to Avoid Duplication of Effort 7

5. Efforts to Minimize Burden on Small Businesses and Other Small Entities 7

6. Consequences of Not Collecting the Data 7

7. Special Circumstances Causing Particular Anomalies in Data Collection 8

8. Federal Register Announcement and Consultation 8

9. Payment or Gift to Respondents 9

10. Assurance of Confidentiality 9

12. Estimated Response Burden 10

13. Estimate of Annualized Cost for Data Collection Activities 12

14. Estimate of Annualized Cost to Federal Government 12

15. Reasons for Changes in Estimated Burden 13

16. Plans for Tabulation and Publication 13

17. Display of Expiration Date for OMB Approval 13

18. Exceptions to Certification for Paperwork Reduction Act Submissions 13

Introduction

The Policy and Program Studies Service (PPSS) of the U.S. Department of Education (ED) requests Office of Management and Budget (OMB) clearance for data collection activities associated with the Study of Title I Schoolwide and Targeted Assistance Programs. The purpose of this study is to provide a detailed analysis of the types of strategies and activities implemented in Title I schoolwide program (SWP) and targeted assistance program (TAP) schools, how different configurations of resources are used to support these strategies, and how local officials make decisions about the use of these varied resources. To this end, the study team will conduct site visits to a set of 35 case study schools that will involve in-person and telephone interviews with Title I district officials and school staff involved in Title I administration. In addition, the study team will collect and review relevant extant data and administer surveys to a nationally representative sample of principals and school district administrators. Both the case study and survey samples include Title I SWP and TAP schools.

Clearance is requested for the case study and survey components of the study, including its purpose, sampling strategy, data collection procedures, and data analysis approach. This submission also includes the clearance request for the data collection instruments.

The complete OMB package contains two sections and a series of appendices as follows:

OMB Clearance Request: Part A – Justification [This Document]

OMB Clearance Request: Part B – Statistical Methods

Appendix A.1 – District Budget Officer Interview Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix A.2 – District Title I Coordinator Interview Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix B – School Budget Officer Interview Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix C – School Improvement Team (SWP School) Focus Group Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix D – School Improvement Team (TAP School) Focus Group Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix E – Principal (SWP School) Interview Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix F – Principal (TAP School) Interview Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix G- Teacher Interview Protocol and Consent Form

Appendix H – Principal Questionnaire

Appendix I – District Administrator Questionnaire

Appendix J – Request for Documents

Appendix K – Notification Letters

Study of Title I Schoolwide and Targeted Assistance Programs

Project Overview

Title I’s schoolwide program (SWP) provisions, introduced in 1978, gave high-poverty schools the flexibility to use Title I funds to serve all students (not just students eligible for Title I) and to support whole-school reforms. Unlike the traditional targeted assistance programs (TAPs), SWP schools also were allowed to commingle Title I funds with those from other federal, state, and local programs and were not required to track dollars back to these sources or track the spending under each source to a specific group of eligible students. Initially aimed at schools with a student poverty rate of 90 percent or more, successive reauthorizations reduced the poverty rate threshold for schoolwide status to 50 percent in 1994 and 40 percent in 2001 under No Child Left Behind. In a change from previous acts, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), enacted in December 2015, further allows states to approve schools to operate an SWP with an even lower poverty percentage. In response to these changes, the number and proportion of schools that are SWPs has increased dramatically over time. In the most recent year for which data are available (2013–14), 77 percent of Title I schools nationwide were SWPs.* The ESSA allowance for states to authorize SWPs in schools with a lower than 40 percent poverty is likely to result in an even greater number of schools operating as SWPs.

In exchange for flexibility, SWPs are required to engage in a specified set of procedures. First, a schoolwide planning team must be established, charged with conducting a needs assessment grounded in a vision for improvement. The team must then develop a comprehensive plan that includes prioritizing effective educational strategies and evaluating and monitoring the plan annually using empirical data. Implicit in these provisions is a vision that SWPs will engage in an ongoing, dynamic continuous improvement process and will implement systemic, schoolwide interventions, thus leading to more effective practices for low-income students. Yet little is known about whether SWPs have realized this vision.

This study will conduct a comparative analysis of SWP and TAP schools to look at the school-level decision-making process, implementation of strategic interventions, and corresponding resources that support these interventions. Comparing how SWP and TAP schools allocate Title I and other resources will provide a window into the different services that students eligible for Title I receive. For example, prior research shows that SWPs are more likely than TAP schools to use their funds to support salaries of instructional aides (U.S. Department of Education [ED], 2009). In addition, a U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report concluded that school districts use Title I funds primarily to support instruction (e.g., teacher salaries and instructional materials) (GAO, 2011), as did an earlier study of Title I resource allocation (ED, 2009). However, such data are not sufficient to show how decisions related to educational strategies and resource allocation are made, and what services and interventions these funds are actually supporting. This study will provide a better understanding of how SWP flexibility may translate into programs and services intended to improve student performance by combining information from several sources, including reviews of school plans and other relevant extant data, case study interviews, and surveys.

Through this study, the research team will address these three primary questions:

How do schoolwide and targeted assistance programs use Title I funds to improve student achievement, particularly for low-achieving subgroups?

How do districts and schools make decisions about how to use Title I funds in schoolwide programs and targeted assistance programs?

To what extent do schoolwide programs commingle Title I funds with other funds or coordinate the use of Title I funds with other funds?

To address the research questions, this study includes two primary types of data collection and analysis, each of which consists of two data sources:

Case studies of 35 schools, which include interviews with district and school officials as well as extant data collection

Nationally representative surveys of Title I district coordinators and principals of SWP and TAP Title I schools

Conceptual Approach

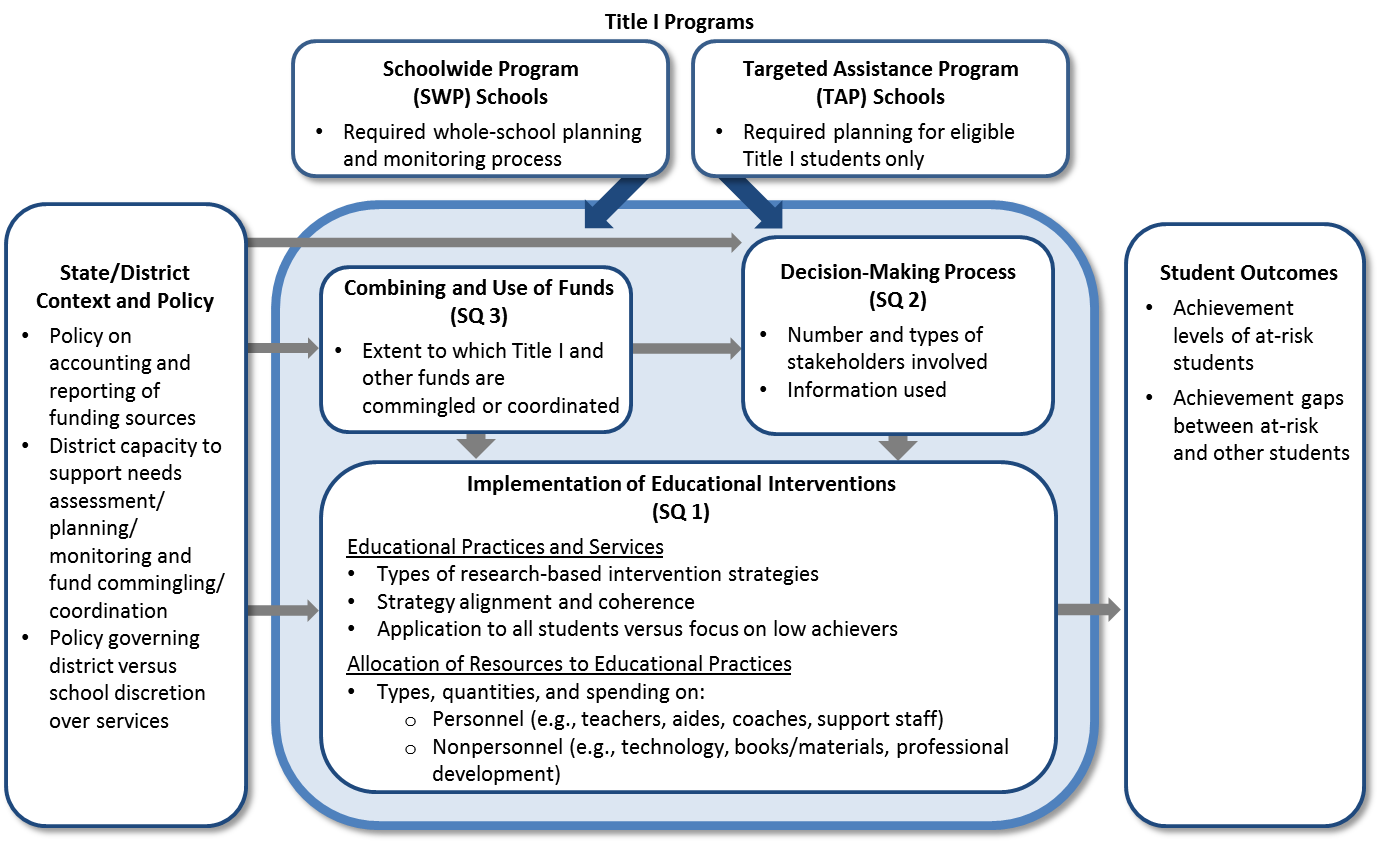

The focus of this study is the complex interplay among school decision making, use of funds, and implementation of educational practices, depicted in the central part of Exhibit 1. Two key policy levers may contribute to differences between SWP and TAP Title I schools: planning requirements and funding flexibility.† Based on a needs assessment grounded in the school’s vision for reform, SWPs must develop an annual comprehensive plan in which they set goals and strategies, and monitor outcomes of all students through an annual review. TAP schools, conversely, are required to identify Title I–eligible students, target program resources to this group, and annually monitor their outcomes separately from the noneligible students. The policy also treats SWP versus TAP schools differently in terms of how each can use their program funding, the accounting/reporting requirements, and the regulatory provisions to which they must adhere. SWPs may commingle Title I funds with other sources of federal, state, and local funding, while TAPs may not. Moreover, for SWPs both reporting requirements and the applicability of statutory/regulatory provisions are relaxed provided that schools can show that the program funding spread over the entire school’s enrollment was spent on intervention strategies that align with the intentions of Title I, which is not the case for TAP schools.

These policy provisions are intended to enable SWPs to design the types of educational programs that, according to decades of research on school improvement, are more likely to benefit students. Studies from the 1980s onward have identified characteristics associated with schools that are successful (particularly for disadvantaged students): shared goals, positive school climate, strong district and school leadership, clear curriculum, maximum learning time, coherent curriculum and instructional programs, use of data, schoolwide staff development, and parent involvement (Desimone, 2002; Fullan, 2007; Purkey & Smith, 1983; Williams et al., 2005). The extent to which SWP and TAP schools use Title I funds to support these kinds of practices—designing coherent whole-school programs with these characteristics, identifying and comingling or coordinating multiple funding streams, and selecting appropriate interventions and practices—is the focus of this study.

Title I requirements and guidance encourage SWPs to engage a greater variety of individuals in a more extensive planning process, rely on more complete schoolwide data sources, and engage in more frequent ongoing monitoring of progress than TAP schools. Research suggests that engagement of a range of school personnel and other stakeholders enhances a school’s decisions about strategies to undertake and commitment to the schoolwide program (Mohrman, Lawler, & Mohrman, 1992; Newcombe & McCormick, 2001; Odden & Busch, 1998). However, given the pervasiveness of state and local school improvement initiatives with similar requirements, it is possible that some TAP schools also engage in similar comprehensive improvement processes.

Notably, however, SWPs are allowed to commingle Title I and other federal, state, and local funds into a single pot to pay for services. In contrast, TAP schools may only leverage multiple funds through the coordination of Title I and the other sources, which require separate tracking and reporting of (1) funding by program and (2) spending by students eligible for each source (see the box “Combining of Funds” in Exhibit 1). Despite this provision, previous research has found that many SWPs do not use this flexibility, with key reasons being conflicts with state or district policy that require separate accounting for federal program funds, fear of not obtaining a clean audit, insufficient training and understanding of program and finance issues, and lack of information on how to consolidate funds (U.S. Department of Education, 2009). Aside from relatively low numbers of SWPs using their funding flexibility, previous research has not examined the relationship between the flexibility in using funds and the educational and resource allocation decisions that translate these funds into services and practices that benefit students.

Exhibit

1. Conceptual Framework for Study of

Title I Schoolwide and

Targeted Assistance Programs

In summary, this study’s collection of data from multiple sources regarding how schools use schoolwide flexibility to address the needs of low-achieving students will be used to answer the three research questions listed earlier. In addition to the three overarching study questions, more specific subquestions are associated with each. Exhibit 2 includes the study questions, as well as the study components intended to address each.

Exhibit 2. Detailed Study Questions

|

Study Components |

||

Extant Data |

Interviews |

Surveys |

|

1. How do SWPs and TAPs use Title I funds to improve student achievement, particularly for low-achieving subgroups? |

|||

a) What educational interventions and services are supported with Title I funds at the school level? |

ü |

ü |

ü |

b) How do interventions in SWPs compare with those implemented in TAPs? To what extent do SWPs use Title I funds differently from TAPs? Do they use resources in ways that would not be possible in a TAP? |

ü |

ü |

ü |

c) How do SWPs and TAPs ensure that interventions and services are helping to meet the educational needs of low-achieving subgroups? |

|

ü |

ü |

2. How do districts and schools make decisions about how to use Title I funds in SWPs and TAPs? |

|||

a) Who is involved in making these decisions? How much autonomy or influence do schools have in making decisions about how to use the school’s Title I allocation? |

|

ü |

ü |

b) Do schools and districts use student achievement data when making decisions about how to use the funds, and if so, how? |

|

ü |

ü |

c) Are resource allocation decisions made prior to the start of the school year, or are spending decisions made throughout the school year? To what extent is the use of funds determined by commitments made in previous years? |

|

ü |

ü |

3. To what extent do SWPs commingle Title I funds with other funds or coordinate the use of Title I funds with other funds? |

|||

a) To what extent do schools use the schoolwide flexibility to use resources in ways that would not be permissible in a TAP? Do they use resources in more comprehensive or innovative ways? To what extent are Title I or combined schoolwide funds used to provide services for specific students versus programs or improvement efforts that are schoolwide in nature? |

|

ü |

ü |

b) What do schools and districts perceive to be the advantages and disadvantages of commingling funds versus coordinating funds? |

ü |

ü |

ü |

c) What barriers did they experience in trying to coordinate the funds from different sources? Were they able to overcome those challenges and how? |

|

ü |

ü |

Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission

Justification

1. Circumstances Making Collection of Information Necessary

Children in high-poverty schools have profound educational needs; they often enter school ill prepared to succeed, and their subsequent educational experiences fail to compensate for challenges associated with poverty. Moreover, the achievement gap between impoverished students and those who are not in poverty has been growing steadily over the past several decades (Reardon, 2011).‡ Meanwhile, the schools they attend often have fewer resources and lower capacity to address their needs (Baker, 2014; Betts, Rueben, & Danenberg, 2000). For more than 50 years, Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) has aimed to improve the prospects of these children by providing additional funding for their schools to develop educational services that will improve student outcomes.

Although the Title I program began by targeting services to eligible students—low achievers in high-poverty schools—the program has increasingly emphasized schoolwide services for several reasons. Early evaluations of the Title I program found that supplementary services could fragment a student’s learning experience; targeted students were often provided pull-out remedial instruction by less qualified personnel (Birman et al., 1987; Commission on Chapter 1, 1992; Wong & Wang, 1994). In contrast, research on effective, high-poverty schools illustrated that such schools could improve student outcomes by adopting whole-school strategies (Committee on Education and Labor, 1992; Wang & Wong, 1997).

Previous studies of Title I resources have revealed that Title I funds primarily support instruction, including teacher salaries and instructional materials (GAO, 2011; ED, 2009). In addition, although federal education funds are targeted to the highest poverty districts, the funds do not close the gap between high- and low-poverty districts (ED, 2009). Although important findings, these studies did not explore the most fundamental policy question related to the largest source of federal education funds: How do schoolwide and targeted assistance programs use Title I funds to improve student achievement? Although there is considerable consensus regarding the intent of Title I, there is surprisingly little information about the extent to which the federal intent is reflected in local practices.

The data collection activities that are the focus of this OMB clearance request will provide descriptive information regarding these critical policy topics: how districts and schools use Title I resources to improve student achievement, how they make decisions about the use of Title I funds, and the extent to which they use the flexibility afforded to schoolwide programs. The American Institutes for Research is conducting this study on behalf of the Policy and Program Studies Service of the U.S. Department of Education. Participation of Title I districts and their schools in this study is required under Section 8306(a)(4) of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which requires grantees to cooperate with U.S. Department of Education evaluations of federal programs for which the grantee receives federal funding.

2. Use of Information

The contractor will use the data collected to prepare a report that clearly describes how the data address the key study questions, highlights key findings of interest to policymakers and educators, and includes charts and tables. The report will be written in a manner suitable for distribution to a broad audience of policymakers and educators and will be accompanied by a two-page Results in Brief. The Department will publicly disseminate the report via its website.

The data collected through this study will be of immediate interest and significance for policymakers and practitioners as it will provide timely, detailed, and policy-relevant information on a major federal program. The study will offer unique insight on how stakeholders in Title I schools make decisions about the use of funds, an in‑depth look into the use of resources in SWP and TAP schools, and will allow program administrators to fine‑tune guidance provided to districts and schools receiving Title I funds. The approach embraces mixed‑methods data collection and the associated analyses will enable the study to report on important Title I processes.

3. Use of Improved Technology to Reduce Burden

The recruitment and data collection plans for this project reflect sensitivity to issues of efficiency and respondent burden. The study team will use a variety of information technologies to maximize the efficiency and completeness of the information gathered for this study and to minimize the burden on respondents at the state, district, and school levels:

Use of extant data. When possible, data will be collected through ED’s and states’ websites and through sources such as EDFacts, and other Web‑based sources. For example, prior to case study data collection activities, the team will compile comprehensive information about each school, including demographics, academic performance, interventions, and accountability designations.

Online surveys. The district and principal surveys will be administered through a Web‑based platform to facilitate and streamline the response process.

Electronic submission of certain data. Districts and schools will be asked to submit certain fiscal data electronically if possible (i.e., data on revenues, expenditures, and Title I school allocations).

Support for respondents. A toll‑free number and e-mail address will be available during the data collection process to permit respondents to contact interview staff with questions or requests for assistance. The toll‑free number and e-mail address will be included in all communication with respondents.

4. Efforts to Avoid Duplication of Effort

Whenever possible, the study team will use existing data including EDFacts, Title I consolidated applications and plans, Consolidated State Performance Reports (CSPRs) and federal monitoring reports, federal, state, and local fiscal and payroll files. This will reduce the number of questions asked in the case study interviews and focus groups, thus limiting respondent burden and minimizing duplication of previous data collection efforts and information.

5. Efforts to Minimize Burden on Small Businesses and Other Small Entities

No small businesses or other small entities will be involved in this project.

6. Consequences of Not Collecting the Data

Failure to collect the data proposed through this study would prevent ED from gaining a better understanding of how SWP and TAP schools allocate their Title I and other resources to meet the needs of low-income students, including the extent to which SWP schools are engaging in an ongoing, dynamic continuous improvement process through the implementation of systemic, schoolwide interventions. Although existing data show that SWP schools are more likely than TAP schools to use their funds for instructional support staff (ED, 2009), and that school districts use Title I funds primarily to support instruction (GAO, 2011), such data are not sufficient to show how decisions related to educational strategies and resource allocations are made in SWP and TAP schools, and what services and interventions these funds are actually supporting. This study will provide a better understanding of how SWP flexibility may translate into programs and services that can improve student performance by pairing information from several sources. Specifically, by conducting a comparative analysis of SWP and TAP schools, this study will provide a new window into the school-level decision-making process, implementation of strategic interventions, and corresponding resources that support these interventions in Title I SWP and TAP schools.

7. Special Circumstances Causing Particular Anomalies in Data Collection

None of the special circumstances listed apply to this data collection.

8. Federal Register Announcement and Consultation

Federal Register Announcement

The Department published a 60-day Federal Register Notice on March 18, 2016 inviting public comment on this information collection request. A 30-day Federal Register Notice will be published as required. No public comments have been received to date.

Consultations Outside the Agency

To assist with the study’s complex technical and substantive issues, the study team drew on the experience and expertise of researchers with substantive expertise that is complementary to the core study team. In particular the study team consulted with Dr. Margaret Goertz, a researcher affiliated with the Consortium for Policy Research in Education (CPRE) at the University of Pennsylvania. In addition to decades of experience studying school improvement (often through case studies), Dr. Goertz brings expertise in fiscal data collection and analyses.

A technical working group (TWG) of state, district, and school officials was convened on April 28, 2016 to provide input on the data collection instruments developed for this study. The TWG consisted of one state-level representative, two district-level representatives, and three school-level representatives. Expert practitioner panelists included:

Elena Bell, Principal of Peabody Primary and Watkins Elementary Schools at the Capitol Hill Cluster School, District of Columbia Public Schools

Deann Collins, Director, Division of Title I & Early Childhood, Montgomery County Public Schools

Ursula Hill, Former principal, Norfolk City Schools

Melanie Kay-Wyatt, Principal of Walker-Grant Middle School, Fredericksburg City Public Schools

Tamiya Larkin, Title Programs Coordinator, Pittsburgh Public School

Mike Radke, Director Michigan Department of Education Office of Field Services

9. Payment or Gift to Respondents

Respondents will not receive a payment or a gift as a result of their participation in this project.

10. Assurance of Confidentiality

The study team is vitally concerned with maintaining the anonymity and security of its records. The project staff have extensive experience collecting information and maintaining the confidentiality, security, and integrity of interview data. All members of the study team have obtained their certification on the use of human subjects in research. This training addresses the importance of the confidentiality assurances given to respondents and the sensitive nature of handling data. The team also has worked with the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at AIR to seek and receive approval of this study, thereby ensuring that the data collection complies with professional standards and government regulations designed to safeguard research participants.

The following data protection procedures were in place:

The study team will protect the identity of individuals from whom we will collect data for the study and used it for research purposes only. Respondents’ names will be used for data collection purposes only and will be disassociated from the data prior to analysis.

Although this study does not include the collection of sensitive information (the only data to be collected directly from case study participants focused on district and school policies and practices rather than on individual people), a member of the research team will explain to participants what will be discussed, how the data will be used and stored, and how their confidentiality will be maintained. Individual participants will be informed that they may stop participating at any time. The study’s goals, data collection activities, participation risks and benefits, and uses for the data are detailed in an informed consent form that all participants will read and sign prior to beginning any data collection activities. The signed consent forms collected by the site visit project staff will be stored in secure file cabinets at the contractors’ offices.

All electronic data will be protected using several methods. The contractors’ internal networks are protected from unauthorized access, including firewalls and intrusion detection and prevention systems. Access to computer systems is password protected, and network passwords must be changed on regular basis and conform to the contractors’ strong password policies. The networks also are configured so that each user has a tailored set of rights, granted by the network administrator, to files approved for access and stored on the local area network. Access to all electronic data files and workbooks associated with this study is limited to researchers on the case study data collection and analysis team.

Responses to this data will be used to summarize findings in an aggregate manner (across groups or sites), or will be used to provide examples of program implementation in a manner that does not associate responses with a specific site or individual. In the report, pseudonyms will be used for each site. The study team may refer to the generic title of an individual (e.g. project director or Principal) but neither the site name nor the individual name will be used. All efforts will be made to keep the description of the site general enough so that the reader would never be able to determine the true name or identity of the site or individuals on the site. The study team will make sure that access to all data with identifiable information is limited to members of the study team. The study team will not provide information that associates responses or findings with a subject or district to anyone outside of the study team, except as required by law.

11. Sensitive Questions

No questions of a sensitive nature are included in this study.

12. Estimated Response Burden

It is estimated that the total hour burden for the data collections for the project is 2,232 hours, including 1867.5 burden hours for the surveys, 39.25 hours for gaining the cooperation of the case study sites, and 325.5 hours for collecting the case study information. This totals an estimated cost of $94,323, based on the estimated average hourly wages of participants. Exhibit 1 summarizes the estimates of respondent burden for the various project activities.

For the surveys, we expect to achieve response rates of 85 percent for principals and 92 percent for district administrators). The total burden estimates are 1,275 hours for principals (for a 1 hour survey) and 592.5 hours for district administrators (for a 1. 5 hour survey).

The 39.25-hour burden estimate for the recruitment of the case study schools and their districts includes the following:

A half-hour hour per state for each of five states

A half-hour per district for each of 21 districts

45 minutes per school for each of 35 schools

The 325.5-hour burden estimate for the case study data collection includes 262.5 hours for the schools themselves and 63 hours for their districts (amounting to 7.5 hours per school and 3 hours per district). This figure includes the following:

Time for district administrators and school administrators in the 35 case study schools and 21 districts to prepare the appropriate documentation, including time for district administrators to compile information on Title I allocations for each school (included in the district survey)

A single one-hour interview with a district administrator

A single one-hour interview with a district budget officer

A half-hour conversation with a district administrator regarding extant document request

A single one-hour interview with a principal at all 35 schools

A single 45-minute interview with a Title I teacher at 30 schools

A half-hour conversation with a school administrator to ensure the team has collected appropriate documents

A single one-hour interview with an assistant principal or school budget coordinator at 20 schools

A single one-hour focus group with a school improvement team, averaging five members per school at 30 schools

Exhibit 1. Summary of Estimated Response Burden

Data Collection Activity |

Task |

Total Sample Size |

Estimated Response Rate |

Estimated Number of Respond-ents |

Time Estimate (in hours) |

Total Hour Burden |

Hourly Rate |

Estimated Monetary Cost of Burden |

Nationally representative survey |

District coordinators (See Appendix I) |

430 |

92% |

395 |

1.5 |

592.5 |

$44.23 |

$26,206 |

Principals (See Appendix H) |

1,500 |

85% |

1,275 |

1 |

1,275 |

$43.36 |

$55,284 |

|

Recruitment for site visits |

State Education Agency administrator conversation* |

5 |

100% |

5 |

0.5 |

2.5 |

$58.99 |

$147 |

District administrator conversation* |

21 |

100% |

21 |

0.5 |

10.5 |

$44.23

|

$464 |

|

Principal conversation* |

35 |

100% |

35 |

0.75 |

26.25 |

$43.36 |

$1,138 |

|

Case study site visits |

District administrator interview (See Appendix A.2) |

21 |

100% |

21 |

1 |

21 |

$44.23 |

$929 |

District budget officer interview (See Appendix A.1) |

21 |

100% |

21 |

1 |

21 |

$44.23 |

$929 |

|

Principal interview (See Appendix E or F) |

35 |

100% |

35 |

1 |

35 |

$43.36 |

$1,518 |

|

District administrator conversation: extant documents* |

21 |

100% |

21 |

0.5 |

10.5 |

$44.23

|

$464 |

Data Collection Activity |

Task |

Total Sample Size |

Estimated Response Rate |

Estimated Number of Respond-ents |

Time Estimate (in hours) |

Total Hour Burden |

Hourly Rate |

Estimated Monetary Cost of Burden |

Case study site visits

|

District administrator prepare extant documents |

21 |

100% |

21 |

0.5 |

10.5 |

$44.23 |

$464 |

School administrator conversation: extant documents* |

35 |

100% |

35 |

0.5 |

17.5 |

$43.36 |

$759 |

|

School administrator prepare extant documents |

35 |

100% |

35 |

0.5 |

17.5 |

$43.36 |

$759 |

|

School budget coordinator interview (See Appendix B) |

20 |

100% |

20 |

1 |

20 |

$29.59 |

$592 |

|

School improvement team focus group (See Appendix C or D) |

150 |

100% |

150 |

1 |

150 |

$27.07 |

$4,061 |

|

Teacher

interview |

30 |

100% |

30 |

0.75 |

22.5 |

$27.07 |

$609 |

|

TOTAL |

|

2,380 |

|

2,120 |

|

2,232 |

|

$94,323 |

Because this study is being conducted over a 24-month period (although it is a one-time data collection that will be conducted during the 2016-17 school year), the annualized burden estimates are 1,060 responses annually and 1,116 burden hours each year.

13. Estimate of Annualized Cost for Data Collection Activities

No additional annualized costs for data collection activities are associated with this data collection beyond the hour burden estimated in item 12.

14. Estimate of Annualized Cost to Federal Government

The estimated cost to the federal government for this study, including development of the data collection plan and data collection instruments as well as data collection, analysis, and report preparation, is $1,981,687.

15. Reasons for Changes in Estimated Burden

This is a new collection so all burden hours are considered program changes.

16. Plans for Tabulation and Publication

The contractor will use the data collected to prepare a report that clearly describes how the data address the key study questions, highlights key findings of interest to policymakers and educators, and includes charts and tables to illustrate the key findings. The report will be written in a manner suitable for distribution to a broad audience of policymakers and educators and will be accompanied by a two-page Results in Brief. We anticipate that the Department will clear and release this report by September 2017. This final report will be made publicly available on the Department’s website, as well as on AIR’s website. In addition, the Results in Brief will be sent to all participants in the study, together with a weblink for the full report.

17. Display of Expiration Date for OMB Approval

All data collection instruments will display the OMB approval expiration date.

18. Exceptions to Certification for Paperwork Reduction Act Submissions

No exceptions to the certification statement identified in Item 19, “Certification for Paperwork Reduction Act Submissions,” of OMB Form 83-I are requested.

References

Baker, B. D. (2014). Evaluating the recession’s impact on state school finance systems. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 22(91). Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v22n91.2014

Betts, J., Reuben, K., & Danenberg, A. (2000). Equal resources, equal outcomes? The distribution of school resources and student achievement in California. San Francisco, CA: Public Policy Institute of California.

Birman, B., Orland, M., Jung., R., Anson, R., Garcia, G., Moore, M.T., Funkhouser, J.E., Morrison, D.R., Turnbull, B.J., & Reisner, E. (1987). The current operations of the Chapter 1 program: Final report from the National Assessment of Chapter 1. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement.

Commission on Chapter 1. (1992). Making schools work for children in poverty. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers.

Committee on Education and Labor, U.S. House of Representatives. (1992). School Improvement Act of 1987, report. Washington, DC: Author.

Desimone, L. (2002). How can comprehensive school reform models be successfully implemented? Review of Educational Research, 72(3), 433–479.

Fullan, M. (2007). The new meaning of educational change (4th ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Mohrman, S. A., Lawler, E. E., & Mohrman, A. M. (1992). Applying employee involvement in schools. Education Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 14, 347–360.

Newcombe, G., & McCormick, J. (2001). Trust and teacher participation in school-based financial decision making. Educational Management Administration Leadership, 29(2), 181–195.

Odden, A., & Busch, C. (1998). Financing schools for high performance: Strategies for improving the use of educational resources. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Purkey, S., & Smith, M. (1983). Effective schools: A Review. Elementary School Journal, 83(4), 427–452.

Reardon, S. F. (2011). The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: New evidence and possible explanations. In R. Murnane & G. Duncan (Eds.), Whither opportunity? Rising inequality and the uncertain life chances of low-income children. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation Press.

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development, Policy and Program Studies Service. (2009). State and local implementation of the No Child Left Behind Act, Volume VI—Targeting and uses of federal education funds. Washington, DC: Author.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2011). Disadvantaged students: School districts have used Title I funds primarily to support instruction (GAO-11-595). Washington, DC: Author.

Wang, M., &Wong, K. (Eds.). (1997). Implementing school reform: Practice and policy perspectives. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Center for Research in Human Development and Education.

Williams, T., Kirst, M., Haertel, E., et al. (2005). Similar students, different results: Why do some schools do better? A large-scale survey of California elementary schools serving low-income students. Mountain View, CA: EdSource.

Wong, K., & Wang, M. (Eds.). (1994). Rethinking policy for at-risk students. Berkeley, CA: McCutchan Publishing.

* Source: 2014–15 EDFacts, Data Group (DG) 22: Title I Status.

† Details on the components and rules governing the use of funds for SWP versus TAP schools can be found in sections 1114 and 1115 of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, Title I, Part A.

‡ For example, Reardon reported that the achievement gap between students from high- and low-income families in 2001 was roughly 30–40 percent larger than for those born in 1976.

* These conversations are intended to be informal and do not have a relevant appendix.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Information Technology Group |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-23 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy