1875-NEW-WSF_OMB_Part_A_RecruitSample_(2017-06-21)

1875-NEW-WSF_OMB_Part_A_RecruitSample_(2017-06-21).docx

Study of Weighted Student Funding and School-Based Systems (recruitment and study design phase)

OMB: 1875-0284

OMB Clearance Request:

Part A—Justification

Study of Weighted Student Funding and School-Based Budgeting Systems: Study Design and District Recruitment

PREPARED BY:

American

Institutes for Research®

1000 Thomas Jefferson

Street, NW, Suite 200

Washington, DC 20007-3835

PREPARED FOR:

Policy and Program Studies Service

Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development

U.S. Department of Education

June 21, 2017

Contents

Study Purpose and Policy Context 2

Mapping Study Questions to Study Components 5

Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission 7

1. Circumstances Making Collection of Information Necessary 7

3. Use of Improved Technology to Reduce Burden 7

4. Efforts to Avoid Duplication of Effort 8

5. Efforts to Minimize Burden on Small Businesses and Other Small Entities 8

6. Consequences of Not Collecting the Data 8

7. Special Circumstances Causing Particular Anomalies in Data Collection 8

8. Federal Register Announcement and Consultation 8

9. Payment or Gift to Respondents 9

10. Assurance of Confidentiality 9

12. Estimated Response Burden 10

13. Estimate of Annualized Cost for Data Collection Activities 13

14. Estimate of Annualized Cost to Federal Government 13

15. Reasons for Changes in Estimated Burden 13

16. Plans for Tabulation and Publication 13

17. Display of Expiration Date for OMB Approval 13

18. Exceptions to Certification for Paperwork Reduction Act Submissions 13

Introduction

The Policy and Program Studies Service (PPSS) of the U.S. Department of Education (ED) requests Office of Management and Budget (OMB) clearance for the study design, sampling procedures, and district sample recruitment activities for the Study of Weighted Student Funding and School-Based Budgeting Systems. The study will investigate how districts vary in their implementation of weighted student funding (WSF) and school-based budgeting (SBB); outcomes in terms of levels of principal autonomy, transparency of resource allocation, and extent to which resources are distributed based on student needs; interactions of WSF and SBB systems with school choice policies; and challenges that districts may have faced in transitioning to and implementing these systems. Data collection will include: a) nationally representative surveys of districts and principals, and b) case studies of nine districts that are implementing WSF systems, including site visits, in-person interviews with district officials and school staff, and analysis of relevant extant data such as descriptive documents, budgets, and audited expenditure files.

This OMB package contains two documents:

OMB Clearance Request: Part A—Justification [this document]

OMB Clearance Request: Part B—Statistical Methods

Note that Part A and Part B both contain an identical study overview (pp. 2-6).

This OMB package also contains the following appendices:

Appendix A: Notification Letter for Sample Recruitment Chief State School Officer/State Superintendent

Appendix B: Notification Letter for Sample Recruitment District Superintendent

Appendix C: District Research Application (Generic Text Commonly Required)

Appendix D: Example District Research Application (Los Angeles Unified School District)

Appendix E: District Administrator Conversation (Introductory Invitation Email)

Study Overview

Study Purpose and Policy Context

The purpose of this study is to examine how districts have implemented school-based budgeting (SBB) systems—and more specifically, weighted student funding (WSF) systems, a type of SBB system that uses weights to distribute funds based on student needs-- for allocating funds to schools and how these districts and their schools compare with districts using traditional approaches to allocating school resources. SBB and WSF systems typically allocate dollars to schools using student-based formulas and devolve decision-making regarding resource use to the school level rather than the central office. This study seeks to understand how SBB systems have been implemented; the outcomes of such systems in terms of levels of principal autonomy, transparency of resource allocation, empowerment of stakeholders in the decision-making process, and the extent to which resources are distributed based on student needs; the interactions of WSF and SBB systems with school choice policies; and the challenges that these districts experienced implementing changes to their resource allocation systems.

Most school districts in the United States distribute staffing and other resources to schools based on total student enrollment. School staffing allocations are generally provided in the form of full-time equivalents (FTEs) of teachers, school administrators, and other types of school staff, without regard for the different salary levels paid to individual staff. Education researchers and policymakers have raised concerns that because high-poverty schools often have teachers with less experience, this approach can result in actual per-pupil expenditures being lower in higher-need schools compared with other schools in the district (Roza and Hill 2003). Supplemental support for student needs is provided by federal and state-funded categorical programs that often distribute predetermined FTEs of staff. When funds from these categorical programs are made available to school sites, they are bound (or perceived to be bound) by certain restrictions on how the money may be spent. In addition, a large proportion of school budgets are already committed due to staffing obligations covered by collective bargaining agreements. Therefore, traditional systems of resource allocation provide little flexibility for principals to shift resources to respond to the unique needs of their school and increase efficiency (producing higher outcomes with a given budget).

Some school districts have experimented with the use of SBB systems as a way to improve both resource efficiency and funding equity while enhancing accountability. In these districts, education leaders have implemented policies that shift decision-making responsibility regarding the utilization of resources away from the central office to schools. Specifically, the use of SBB has emerged as an alternative to the more traditional allocation systems; school districts utilizing SBB allocate dollars to schools rather than staffing positions. WSF systems specifically emphasize equity by differentially distributing dollars to schools on the basis of the individual learning needs of the students served, with more dollars distributed to school for students who may cost more to educate, such as those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged (e.g., from low-income households), English learners, and students with disabilities.

Similar to other systemic reforms, implementation of SBB will vary according to how districts choose to design the policy. Canada’s Edmonton school district was one of the first to implement a large-scale SBB model in 1974 (named Results-Based Budgeting) that allowed schools to directly plan approximately 80 percent of the district’s budget with input from teachers, students, parents, and the community. A number of U.S. districts have also implemented SBB policies for allocating dollars directly to schools. In an effort to distribute dollars more equitably, some systems have employed different types of student weights and other factors to provide additional resources to schools to account for the higher costs associated with various student need and scale of operation factors. These weights and factors have often included:

Students in specific grade or schooling levels (i.e., elementary, middle, or high)

Students from low-income families

English learners

Students not meeting educational targets

Gifted and talented students

Students with disabilities who are eligible for special education services

Schools serving a small population of students

The existing literature base on SBB and WSF is limited, and relatively few studies have investigated how these systems operate and what outcomes they have achieved related to resource allocation, such as whether implementation is associated with significant increases in the equity with which resource are distributed, increased school autonomy, or changes in school programmatic decisions. This study will help to fill this gap in the literature through an in-depth qualitative and quantitative analysis of data from the following sources:

Nationally representative surveys of district administrators and school principals

Case studies of nine WSF school districts, which include interviews and focus groups with district and school officials/staff as well as extant data collection.

The study will address four primary study questions:

How are resources allocated to schools in districts with SBB systems compared with districts with more traditional resource allocation practices?

In what ways do schools have autonomy and control over resource allocation decisions, and how does this vary between districts with SBB and other districts?

How has the implementation of SBB in districts using weights to adjust funding based on student needs affected the distribution of dollars to schools?

What challenges did districts and schools experience in implementing SBB, and how did they respond to those challenges?

Conceptual Approach

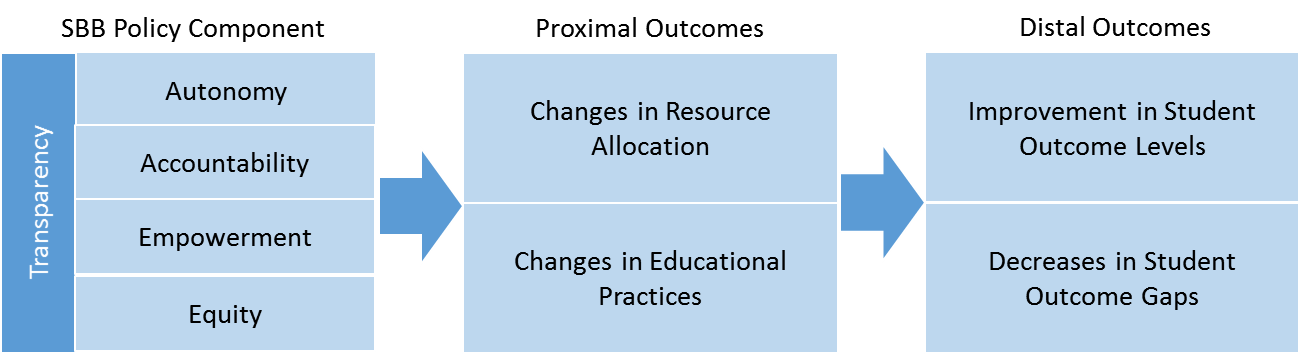

Under a SBB system, changes in educational resource allocation and practice are thought to occur as a result of moving to a decentralized system that distributes dollars to schools coupled with enhanced principal decision-making autonomy. Greater autonomy will allow schools to improve the efficiency and appropriateness of resource usage and educational practice for their own students, which will translate into improved outcomes for students. SBB also often includes greater stakeholder involvement in decision-making and aims for more transparency in resource allocation systems. Under WSF systems, resources are also distributed with a greater focus on equity, with schools with higher student needs receiving more funds. Exhibit 1 provides a graphical depiction of a simple theory of action illustrating the underlying mechanism that links various SBB policy components to both resource allocation and educational practice outcomes and student outcomes. The discussion that follows describes how these SBB components work together and link to these outcomes. SBB typically includes all or some of these components, and the focus of this study is on the prevalence of each component and the relationships among them.

Exhibit 1. Theory of Action Linking School-Based Budgeting (SBB) Policy Components to Changes in Resource Allocation and Improvements in School-Level Achievement

Autonomy. It has been argued that under traditional resource allocation systems school leaders are given little discretion over how dollars are spent at their schools, and the process of allocating resources becomes more of an exercise in compliance rather than thoughtful planning to ensure that a more efficient combination of resources is being employed to meet the individual needs of students. The impact of autonomy on student achievement is unclear, however, and it may depend on exactly what types of staff and other resources principals have authority to allocate. International studies have suggested that principal autonomy is associated with higher student achievement in high-achieving countries (Hanushek et al. 2013), but that autonomy in hiring decisions is associated with higher achievement while autonomy in formulating the school budget is not (Woessmann et al. 2007). SBB systems provide schools with increased spending autonomy over the dollars they receive. This may allow for improved resource allocation by allowing those who are closest to students and arguably most knowledgeable about how to best address their educational needs to make the spending decisions. Prior research suggests that increased principal autonomy can indeed lead to improved school quality and student outcomes (Honig and Rainey 2012; Mizrav 2014; Roza et al. 2007; Steinberg 2014).

Accountability. Increasing school autonomy also implicitly shifts a significant amount of responsibility for delivering results from the central office to school leadership. As a result, the accountability to which schools are held under the SBB policy may increase because school leaders are given more discretion over the means to success. Accountability requires that schools have more choice of the staff they employ (i.e., in terms of both quantities and qualifications), the responsibilities school leadership assigns to staff, and the materials and support services (e.g., professional development or other contracted services) made available. The theory suggests that given the expanded autonomy afforded school sites and enhanced expectations to deliver results, schools will react by modifying both their resource allocations and educational practices, which should translate into improved student achievement.

Empowerment. Another key component of SBB is to empower school staff other than administrative leadership (e.g., teachers, instructional and pupil support staff), other local community stakeholders (e.g., parents, other educational advocates), and even students (e.g., at the high school level) by making them privy to information related to incoming funding and involved in decisions about how to use those funds. Specifically, enhancing empowerment involves the significant inclusion of these parties in the decision-making and governance processes, such as participating in developing the mission and vision of the school and helping to determine the resources and practices that will be employed to best serve students. In addition to the direct contributions that empowered staff and other stakeholders make to resource allocation and educational practice decisions, empowerment also serves to enhance the accountability to which school sites are held through increased stakeholder understanding of funding and school operations. In summary, empowerment should affect how autonomy is used to change both resource allocation and educational practice, which should translate into improved student achievement and be reinforced by an increase in the degree to which schools are accountable for results.

Equity. SBB policies- and WSF systems in particular- often intend to promote equity by implementing a funding model based on student needs. Providing funding that is based on the additional costs associated with achieving similar outcomes for students with specific needs and circumstances (i.e., those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged, English learners, disabled, or attend schools where it is more costly to provide services) increases equity by providing schools serving students with higher needs relatively higher levels of resources. The framework therefore suggests that changes in the proximal outcomes related to resource allocation and educational practice as a result of more equitable resource distribution will translate into improvements in more distal outcomes related to student achievement.

Transparency. Pervading all of the SBB policy components is a general increase in transparency by simplifying and clarifying the processes by which funding and other resources (staffing and materials) are allocated to schools. For example, a SBB district would typically provide a base amount of per-pupil funding to each school based on total student enrollment, often with additional funds for students in particular categories of need, such as English learners or students in poverty (in the case of WSF). These additional amounts are often implemented using a series of student weights that are meant to be transparent and easy to understand. They also are simpler than more typical systems, in which case a school might receive multiple allocations of various types of staff based on its student enrollment, plus funding sources from multiple categorical funds that may be numerous, difficult to understand, and potentially manipulated by the district. SBB systems also aim to improve access of stakeholders to information pertaining to resource allocation, educational practice, student outcomes, as well as funding. Specifically, needs-based funding models implemented under a WSF or SBB policy provide transparent dollar allocations to each school. Furthermore, details of the school program developed under the increased autonomy also are made clear to empowered stakeholders (some of whom even participate in the design process), as is information on student outcomes, all of which is intended to promote accountability.

Mapping Study Questions to Study Components

There are two main study components – a nationally representative survey and case studies of WSF districts – each having several data sources that will be analyzed to answer the research questions. The survey data collection will administer both district-level and school-level surveys to district officials and school principals, respectively. The case studies will consist of a qualitative analysis of interview data and extant documentation, as well as a quantitative analysis of school-level expenditure data. Exhibit 2 shows how the study subquestions map to each of the study data sources.

Exhibit 2. Detailed Study Questions and Associated Data Sources

Detailed Study Questions |

Data Sources |

|||

Survey |

Case Study |

|||

District |

Principal |

Qualitative |

Quantitative |

|

|

||||

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

||||

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

3. How has the implementation of SBB in districts using weights to adjust funding based on student needs affected the distribution of funding provided dollars to schools? |

||||

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

||||

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission

Justification

1. Circumstances Making Collection of Information Necessary

As discussed in the Study Overview section, the purpose of this study is to examine how districts have implemented weighted student funding (WSF) and school-based budgeting (SBB) systems for allocating funds to schools and how these districts and their schools compare with those using traditional approaches to allocating school resources. SBB systems typically allocate dollars to schools using student-based formulas, rather than the prevalent approach of allocating staff FTEs and other purchased resources to schools. In addition, they commonly devolve at least some decision-making regarding resource use to the school level rather than the central office. This study will investigate how WSF and SBB systems have been implemented; the outcomes of such systems in terms of levels of principal autonomy, transparency of resource allocation, empowerment of stakeholders in the decision-making process, and equity of resource distribution; the interactions of WSF and SBB systems with school choice policies; and the challenges that these districts experienced in implementing changes to their resource allocation systems. It will also help to fill a gap in the literature by investigating in more depth the prevalence and implementation of SBB systems. American Institutes for Research (AIR) is conducting this study on behalf of the Policy and Program Studies Service of the U.S. Department of Education.

2. Use of Information

The contractor will use the data collected to prepare a report that clearly presents findings from the data to address the key study questions, highlights key findings of interest to policymakers and educators, and includes charts and tables to illustrate the findings. The report will be written in a manner suitable for distribution to a broad audience of policymakers and educators and will be accompanied by a two-page Results in Brief. ED will publicly disseminate the report via its website.

The data collected through this study will be of immediate interest and significance for policymakers and practitioners as they will provide timely, detailed, and policy-relevant information on how districts have implemented WSF and SBB systems and district officials’ perceived benefits in terms of enhanced school funding equity and improved resource allocation practice, as well as the challenges each district may have faced in undertaking such a reform. For instance, the results will inform any continued development of the Pilot Program for Weighted Student Formulas introduced as part of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), as well as policy related to promoting site-based budgeting.

3. Use of Improved Technology to Reduce Burden

The recruitment and data collection plans for this project reflect sensitivity to issues of efficiency and respondent burden. The study team will use a variety of information technologies as follows to maximize the efficiency and completeness of the information gathered for this study and to minimize the burden on respondents at the state, district, and school levels:

When possible, data will be collected through ED’s and states’ websites and through sources such as EDFacts, and other Web‑based sources. For example, prior to case study data collection activities, the team will compile comprehensive information about each school, including demographics, academic performance, interventions, and accountability designations.

District and principals surveys will be administered through a Web‑based platform to streamline the response process. Paper versions of the survey will be available for those that would prefer not to respond by web. Staff will be trained to complete the survey over the telephone if a respondent would prefer that mode instead of web or paper.

A toll‑free number and email address will be available during the data collection process to permit respondents to contact interview staff with questions or requests for assistance. The toll‑free number and email address will be included in all communication with respondents.

4. Efforts to Avoid Duplication of Effort

Whenever possible, the study team will use existing data including EDFacts, Common Core of Data, and existing reports and case studies on districts with WSF or SBB systems. This will reduce the number of questions asked in the surveys, thus limiting respondent burden and minimizing duplication of previous data collection efforts and information.

5. Efforts to Minimize Burden on Small Businesses and Other Small Entities

No small businesses or other small entities will be involved in this project. We are assuming charter schools are not considered small entities. We also will be minimizing burden on all districts and schools in our sample based on data collection procedures that we have developed over several similar studies (including those performed for PPSS).

6. Consequences of Not Collecting the Data

Failure to collect the data proposed through this study would prevent ED from gaining a better understanding of how WSF and SBB systems, which have potential to increase both efficiency and equity in school funding, are implemented. The existing literature base addressing the effects of WSF and SBB systems is limited. To date, there have been few studies that have investigated outcomes related to resource allocation, including improved resource equity, enhanced autonomy, and changes in school programmatic decisions associated with implementation of SBB-type policies. Through multiple data sources, this study will describe how these systems may translate into programs and services that can improve student performance. Specifically, by conducting both nationally representative surveys and in-depth case studies, this study will provide a better understanding of how WSF and SBB systems compare to more traditional systems and the challenges faced by districts in implementing these systems.

7. Special Circumstances Causing Particular Anomalies in Data Collection

None of the special circumstances listed apply to this data collection.

8. Federal Register Announcement and Consultation

Federal Register Announcement

The Department published a 60-day Federal Register Notice on January 23, 2017, Vol. 82, page 7813, inviting public comment on the information collection request for the recruitment and sample attainment activities for this study. A 30-day Federal Register Notice was also published as required. No public comments have been received to date.

Consultations Outside the Agency

To assist with the study’s complex technical and substantive issues, the study team drew upon the knowledge of researchers and practitioners with experience and expertise surrounding WSF and SBB systems. A technical working group (TWG) of state and district officials and researchers took place on March 7, 2017, to gather input on the data collection instruments developed for this study. The TWG consists of five members (a combination of researchers and practitioners), including:

Mark Ferrandino, Chief Financial Officer, Denver Public Schools

Betty Malen, University of Maryland

Amy Ellen Schwartz, Syracuse University

Jonathan Travers, Education Resource Strategies

Jason Willis, WestEd and former Assistant Superintendent, San Jose Unified School District

9. Payment or Gift to Respondents

Both district and principal respondents that satisfactorily complete and submit a survey will receive $25.00 gift cards as a token of appreciation for their time and effort. Based on the literature, these incentives are expected to increase response rates and reduce the need for more costly survey follow-up (Singer & Ye, 2012). No additional funds will be sought for these incentives; other slight adjustments to the allocation of contract funding will be made in order to free up the funds for the incentive payments. In addition, the cost may be offset because fewer telephone follow-ups will be necessary if the incentives increase response rates in this study.

10. Assurance of Confidentiality

The study team is concerned with maintaining the confidentiality and security of its records. The project staff have extensive experience collecting information and maintaining the confidentiality, security, and integrity of survey data. All members of the study team have obtained their certification on the use of human subjects in research. This training addresses the importance of the confidentiality assurances given to respondents and the sensitive nature of handling data. The team also has worked with the contractor’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) to seek and receive approval of this study, thereby ensuring that the data collection complies with professional standards and government regulations designed to safeguard research participants.

The following data protection procedures will be in place:

The study team will protect the identity of individuals from whom we will collect data for the study and use the data for research purposes only. Respondents’ names will be used for data collection purposes only and will be disassociated from the data prior to analysis.

Although this study does not include the collection of sensitive information (the only data to be collected directly from case study participants focused on district and school policies and practices rather than on individual people), a member of the research team will explain to participants what will be discussed, how the data will be used and stored, and how their confidentiality will be maintained. Participants will be informed that they may stop participating at any time. The study’s goals, data collection activities, participation risks and benefits, and uses for the data are detailed in an informed consent form that all participants will read and sign prior to beginning any data collection activities. The signed consent forms collected by the site visit project staff will be stored in secure file cabinets at the contractors’ offices.

All electronic data will be protected using several methods. The contractors’ internal networks are protected from unauthorized access, including firewalls and intrusion detection and prevention systems. Access to computer systems is password protected, and network passwords must be changed on a regular basis and conform to the contractors’ strong password policies. The networks also are configured so that each user has a tailored set of rights, granted by the network administrator, to files approved for access and stored on the local area network. Access to all electronic data files and workbooks associated with this study is limited to researchers on the case study data collection and analysis team.

The data collected will be used to summarize findings in an aggregate manner (across groups or sites), or to provide examples of program implementation in a manner that does not associate responses with a specific site or individual. In the report, pseudonyms will be used for each site. The study team may refer to the generic title of an individual (e.g. district administrator or principal) but neither the site name nor the individual name will be used. All efforts will be made to keep the description of the site general enough so that the reader would never be able to determine the true name or identity of the site or individuals on the site. The study team will make sure that access to all data with identifiable information is limited to members of the study team. The study team will not provide information that associates responses or findings with a subject or district to anyone outside of the study team, except as required by law.

11. Sensitive Questions

No questions of a sensitive nature are included in this study.

12. Estimated Response Burden

It is estimated that the total hour burden for recruitment and sampling for the project is 246.7 hours for gaining the cooperation from districts, including those that require research applications. This totals an estimated cost of $11,042 and is based on the estimated average hourly wages of participants (Exhibit 3). The estimated burden for site visit protocols and survey instruments will be included in a separate future OMB submission.

Exhibit 3. Summary of Estimated Response Burden

Data Collection Activity |

Task |

Total Sample Size |

Estimated Response Rate |

Estimated Number of Respondents |

Time Estimate (in hours) |

Total Hour Burden |

Hourly Rate |

Estimated Monetary Cost of Burden |

Recruitment of nationally representative sample and non-case study certainty districts |

Study Notification Letter, Chief state school officer/State superintendenta |

52 |

100% |

52 |

0.17 |

8.8 |

$58.99 |

$521 |

Study Notification, District Superintendentb |

398 |

100% |

398 |

0.17 |

67.7 |

$44.23 |

$2,993 |

|

District Research Application Coordinatorb |

398 |

20% |

80 |

2 |

160.0 |

$44.23 |

$7,077 |

|

Subtotal |

|

|

530 |

|

236.5 |

|

$10,591 |

|

Recruitment for purposive WSF case study sample |

Study Notification Letter, Chief state school officer/State superintendentc |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0.17 |

0.0 |

$58.99 |

$0 |

Study Notification, District Superintendentb |

10 |

100% |

10 |

0.17 |

1.7 |

$44.23 |

$75 |

|

District Research Application Coordinatorb |

10 |

20% |

2 |

2 |

4.0 |

$44.23 |

$177 |

|

District administrator conversation |

9 |

100% |

9 |

0.5 |

4.5 |

$44.23 |

$199 |

|

Subtotal |

|

|

21 |

|

10.2 |

|

$451 |

|

TOTAL |

|

|

|

551 |

|

246.7 |

|

$11,042 |

a. The total number of states notified will be dependent on the final sample selection. However, the maximum number of states that would be notified will be 52 (50 states plus District of Columbia and Puerto Rico).

b. Prior studies have shown that an expected 20 percent of districts will require the filing of research applications, of which 10 percent will not be approved. Therefore, it will be necessary to reach out to 8 additional districts for a total of 398 districts in order to obtain an initial sample of 390 that we will invite to complete surveys (390 equals 369 in the nationally representative sample plus 21 non-case study districts that will be sampled with certainty). Similarly, in order to obtain a total of 9 participating case study districts we expect to reach out to 1 additional district.

c. The study notification letter to the chief state school officer/State superintendent about the case study site visits will be incorporated into the study notification letter about the nationally representative sample data collection activities.

13. Estimate of Annualized Cost for Data Collection Activities

No additional annualized costs for data collection activities are associated with this data collection beyond the hour burden estimated in item 12.

14. Estimate of Annualized Cost to Federal Government

The estimated cost to the federal government for this study, including development of the data collection plan and data collection instruments, sample selection and recruitment, as well as data collection, analysis, and report preparation, is expected to be $1,442,687.

15. Reasons for Changes in Estimated Burden

This is a new collection so all burden hours are considered program changes.

16. Plans for Tabulation and Publication

Findings from the study will be published in a final report. The final report is expected to be cleared for released by September 2018 and will be available on the Department of Education website as well as the contractor’s website. It will also be disseminated through ED’s public communication channels and through the contractor’s external contacts (newsletter and web logs) and directly to all participants in the study.

17. Display of Expiration Date for OMB Approval

All data collection instruments will display the OMB approval expiration date.

18. Exceptions to Certification for Paperwork Reduction Act Submissions

No exceptions to the certification statement identified in Item 19, “Certification for Paperwork Reduction Act Submissions,” of OMB Form 83-I are requested.

References

Hanushek, Eric A., Susanne Link, and Ludger Woessmann. 2013. “Does School Autonomy Make Sense Everywhere? Panel Estimates From PISA.” Journal of Development Economics 104: 212–32.

Honig, Meredith I. and Lydia R. Rainey. 2013. “Autonomy and School Improvement: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go From Here?” Educational Policy 26(3): 465-495.

Mizrav, Etai. 2014. Could Principal Autonomy Produce Better Schools? Evidence From the Schools and Staffing Survey. https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/709855

Roza, Marguerite, Tricia Davis, and Kacey Guin. 2007. Spending Choices and School Autonomy: Lessons From Ohio Elementary Schools (Working Paper 21). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Center on Reinventing Public Education, School Finance Redesign Project. http://www.crpe.org/sites/default/files/wp_sfrp21_rozaohio_jul07_0.pdf

Roza, Marguerite, and Paul T. Hill. 2003. How Within-District Spending Inequities Help Some Schools to Fail (Brookings Conference Working Paper). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Center on Reinventing Public Education.

Singer, E., Ye, C. (2012). The Use and Effects of Incentives in Surveys. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 645(1), 112-141.

Woessmann, Ludger, Elke Lüdemann, Gabriela Schütz, and Martin R. West. 2007. School Accountability, Autonomy, Choice, and the Level of Student Achievement: International Evidence from PISA 2003 (OECD Education Working Papers, No. 13). doi:10.1787/246402531617 http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED504023.pdf

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| File Title | WSF OMB Part A Recruit Sample |

| Author | American Institutes for Research |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-23 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy