Study of Weighted Student Funding and School-Based Systems (recruitment and study design phase)

Study of Weighted Student Funding and School-Based Systems (recruitment and study design phase)

1875-NEW-WSF_OMB_Part_B_RecruitSample_(2017-06-21)

Study of Weighted Student Funding and School-Based Systems (recruitment and study design phase)

OMB: 1875-0284

OMB Clearance Request:

Part B—Statistical Methods

Study of Weighted Student Funding and School-Based Budgeting Systems: Study Design and District Recruitment

PREPARED BY:

American

Institutes for Research

1000 Thomas Jefferson St. NW,

Suite 200

Washington, DC 20007-3835

PREPARED FOR:

U.S. Department of Education

Policy and Program Studies Service

June 21, 2017

Contents

Study Purpose and Policy Context 2

Mapping Study Questions to Study Components 5

Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission 7

Description of Statistical Methods 7

2. Procedures for Data Collection 13

3. Methods to Maximize Response Rates in the Survey 18

4. Expert Review and Piloting Procedures 20

Introduction

The Policy and Program Studies Service (PPSS) of the U.S. Department of Education (ED) requests Office of Management and Budget (OMB) clearance for the study design, sampling procedures, and district sample recruitment activities for the Study of Weighted Student Funding and School-Based Budgeting Systems. The study will investigate how districts vary in their implementation of weighted student funding (WSF) and school-based budgeting (SBB); outcomes in terms of levels of principal autonomy, transparency of resource allocation, and extent to which resources are distributed based on student needs; interactions of WSF and SBB systems with school choice policies; and challenges that districts may have faced in transitioning to and implementing these systems. Data collection will include: a) nationally representative surveys of districts and principals, and b) case studies of nine districts that are implementing WSF systems, including site visits, in-person interviews with district officials and school staff, and analysis of relevant extant data such as descriptive documents, budgets, and audited expenditure files.

The clearance request for this study will be submitted in two stages in order to provide more advance time to recruit sample districts, which sometimes have their own extended application processes for conducting research in their districts, before the start of the school year and the actual data collection. In this clearance package, we are requesting approval for the study design, including sampling plan and data collection procedures, as well as for recruiting the sample districts. The data collection instruments will be submitted through a separate OMB package.

This OMB package contains two documents:

OMB Clearance Request: Part A—Justification

OMB Clearance Request: Part B—Statistical Methods [this document]

Note that Part A and Part B both contain an identical study overview (pp. 2-6).

This OMB package also contains the following appendices:

Appendix A: Notification Letter for Sample Recruitment Chief State School Officer/State Superintendent

Appendix B: Notification Letter for Sample Recruitment District Superintendent

Appendix C: District Research Application (Generic Text Commonly Required)

Appendix D: Example District Research Application (Los Angeles Unified School District)

Appendix E: District Administrator Conversation (Introductory Invitation Email)

Study Overview

Study Purpose and Policy Context

The purpose of this study is to examine how districts have implemented school-based budgeting (SBB) systems—and more specifically, weighted student funding (WSF) systems, a type of SBB system that uses weights to distribute funds based on student needs-- for allocating funds to schools and how these districts and their schools compare with districts using traditional approaches to allocating school resources. SBB and WSF systems typically allocate dollars to schools using student-based formulas and devolve decision-making regarding resource use to the school level rather than the central office. This study seeks to understand how SBB systems have been implemented; the outcomes of such systems in terms of levels of principal autonomy, transparency of resource allocation, empowerment of stakeholders in the decision-making process, and the extent to which resources are distributed based on student needs; the interactions of WSF and SBB systems with school choice policies; and the challenges that these districts experienced implementing changes to their resource allocation systems.

Most school districts in the United States distribute staffing and other resources to schools based on total student enrollment. School staffing allocations are generally provided in the form of full-time equivalents (FTEs) of teachers, school administrators, and other types of school staff, without regard for the different salary levels paid to individual staff. Education researchers and policymakers have raised concerns that because high-poverty schools often have teachers with less experience, this approach can result in actual per-pupil expenditures being lower in higher-need schools compared with other schools in the district (Roza and Hill 2003). Supplemental support for student needs is provided by federal and state-funded categorical programs that often distribute predetermined FTEs of staff. When funds from these categorical programs are made available to school sites, they are bound (or perceived to be bound) by certain restrictions on how the money may be spent. In addition, a large proportion of school budgets are already committed due to staffing obligations covered by collective bargaining agreements. Therefore, traditional systems of resource allocation provide little flexibility for principals to shift resources to respond to the unique needs of their school and increase efficiency (producing higher outcomes with a given budget).

Some school districts have experimented with the use of SBB systems as a way to improve both resource efficiency and funding equity while enhancing accountability. In these districts, education leaders have implemented policies that shift decision-making responsibility regarding the utilization of resources away from the central office to schools. Specifically, the use of SBB has emerged as an alternative to the more traditional allocation systems; school districts utilizing SBB allocate dollars to schools rather than staffing positions. WSF systems specifically emphasize equity by differentially distributing dollars to schools on the basis of the individual learning needs of the students served, with more dollars distributed to school for students who may cost more to educate, such as those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged (e.g., from low-income households), English learners, and students with disabilities.

Similar to other systemic reforms, implementation of SBB will vary according to how districts choose to design the policy. Canada’s Edmonton school district was one of the first to implement a large-scale SBB model in 1974 (named Results-Based Budgeting) that allowed schools to directly plan approximately 80 percent of the district’s budget with input from teachers, students, parents, and the community. A number of U.S. districts have also implemented SBB policies for allocating dollars directly to schools. In an effort to distribute dollars more equitably, some systems have employed different types of student weights and other factors to provide additional resources to schools to account for the higher costs associated with various student need and scale of operation factors. These weights and factors have often included:

Students in specific grade or schooling levels (i.e., elementary, middle, or high)

Students from low-income families

English learners

Students not meeting educational targets

Gifted and talented students

Students with disabilities who are eligible for special education services

Schools serving a small population of students

The existing literature base on SBB and WSF is limited, and relatively few studies have investigated how these systems operate and what outcomes they have achieved related to resource allocation, such as whether implementation is associated with significant increases in the equity with which resource are distributed, increased school autonomy, or changes in school programmatic decisions. This study will help to fill this gap in the literature through an in-depth qualitative and quantitative analysis of data from the following sources:

Nationally representative surveys of district administrators and school principals

Case studies of nine WSF school districts, which include interviews and focus groups with district and school officials/staff as well as extant data collection.

The study will address four primary study questions:

How are resources allocated to schools in districts with SBB systems compared with districts with more traditional resource allocation practices?

In what ways do schools have autonomy and control over resource allocation decisions, and how does this vary between districts with SBB and other districts?

How has the implementation of SBB in districts using weights to adjust funding based on student needs affected the distribution of dollars to schools?

What challenges did districts and schools experience in implementing SBB, and how did they respond to those challenges?

Conceptual Approach

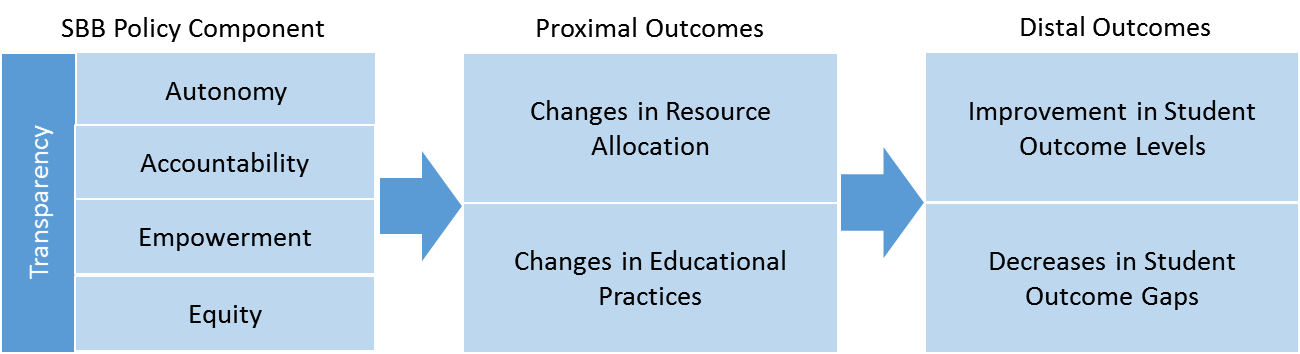

Under a SBB system, changes in educational resource allocation and practice are thought to occur as a result of moving to a decentralized system that distributes dollars to schools coupled with enhanced principal decision-making autonomy. Greater autonomy will allow schools to improve the efficiency and appropriateness of resource usage and educational practice for their own students, which will translate into improved outcomes for students. SBB also often includes greater stakeholder involvement in decision-making and aims for more transparency in resource allocation systems. Under WSF systems, resources are also distributed with a greater focus on equity, with schools with higher student needs receiving more funds. Exhibit 1 provides a graphical depiction of a simple theory of action illustrating the underlying mechanism that links various SBB policy components to both resource allocation and educational practice outcomes and student outcomes. The discussion that follows describes how these SBB components work together and link to these outcomes. SBB typically includes all or some of these components, and the focus of this study is on the prevalence of each component and the relationships among them.

Exhibit 1. Theory of Action Linking School-Based Budgeting (SBB) Policy Components to Changes in Resource Allocation and Improvements in School-Level Achievement

Autonomy. It has been argued that under traditional resource allocation systems school leaders are given little discretion over how dollars are spent at their schools, and the process of allocating resources becomes more of an exercise in compliance rather than thoughtful planning to ensure that a more efficient combination of resources is being employed to meet the individual needs of students. The impact of autonomy on student achievement is unclear, however, and it may depend on exactly what types of staff and other resources principals have authority to allocate. International studies have suggested that principal autonomy is associated with higher student achievement in high-achieving countries (Hanushek et al. 2013), but that autonomy in hiring decisions is associated with higher achievement while autonomy in formulating the school budget is not (Woessmann et al. 2007). SBB systems provide schools with increased spending autonomy over the dollars they receive. This may allow for improved resource allocation by allowing those who are closest to students and arguably most knowledgeable about how to best address their educational needs to make the spending decisions. Prior research suggests that increased principal autonomy can indeed lead to improved school quality and student outcomes (Honig and Rainey 2012; Mizrav 2014; Roza et al. 2007; Steinberg 2014).

Accountability. Increasing school autonomy also implicitly shifts a significant amount of responsibility for delivering results from the central office to school leadership. As a result, the accountability to which schools are held under the SBB policy may increase because school leaders are given more discretion over the means to success. Accountability requires that schools have more choice of the staff they employ (i.e., in terms of both quantities and qualifications), the responsibilities school leadership assigns to staff, and the materials and support services (e.g., professional development or other contracted services) made available. The theory suggests that given the expanded autonomy afforded school sites and enhanced expectations to deliver results, schools will react by modifying both their resource allocations and educational practices, which should translate into improved student achievement.

Empowerment. Another key component of SBB is to empower school staff other than administrative leadership (e.g., teachers, instructional and pupil support staff), other local community stakeholders (e.g., parents, other educational advocates), and even students (e.g., at the high school level) by making them privy to information related to incoming funding and involved in decisions about how to use those funds. Specifically, enhancing empowerment involves the significant inclusion of these parties in the decision-making and governance processes, such as participating in developing the mission and vision of the school and helping to determine the resources and practices that will be employed to best serve students. In addition to the direct contributions that empowered staff and other stakeholders make to resource allocation and educational practice decisions, empowerment also serves to enhance the accountability to which school sites are held through increased stakeholder understanding of funding and school operations. In summary, empowerment should affect how autonomy is used to change both resource allocation and educational practice, which should translate into improved student achievement and be reinforced by an increase in the degree to which schools are accountable for results.

Equity. SBB policies- and WSF systems in particular- often intend to promote equity by implementing a funding model based on student needs. Providing funding that is based on the additional costs associated with achieving similar outcomes for students with specific needs and circumstances (i.e., those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged, English learners, disabled, or attend schools where it is more costly to provide services) increases equity by providing schools serving students with higher needs relatively higher levels of resources. The framework therefore suggests that changes in the proximal outcomes related to resource allocation and educational practice as a result of more equitable resource distribution will translate into improvements in more distal outcomes related to student achievement.

Transparency. Pervading all of the SBB policy components is a general increase in transparency by simplifying and clarifying the processes by which funding and other resources (staffing and materials) are allocated to schools. For example, a SBB district would typically provide a base amount of per-pupil funding to each school based on total student enrollment, often with additional funds for students in particular categories of need, such as English learners or students in poverty (in the case of WSF). These additional amounts are often implemented using a series of student weights that are meant to be transparent and easy to understand. They also are simpler than more typical systems, in which case a school might receive multiple allocations of various types of staff based on its student enrollment, plus funding sources from multiple categorical funds that may be numerous, difficult to understand, and potentially manipulated by the district. SBB systems also aim to improve access of stakeholders to information pertaining to resource allocation, educational practice, student outcomes, as well as funding. Specifically, needs-based funding models implemented under a WSF or SBB policy provide transparent dollar allocations to each school. Furthermore, details of the school program developed under the increased autonomy also are made clear to empowered stakeholders (some of whom even participate in the design process), as is information on student outcomes, all of which is intended to promote accountability.

Mapping Study Questions to Study Components

There are two main study components – a nationally representative survey and case studies of WSF districts – each having several data sources that will be analyzed to answer the research questions. The survey data collection will administer both district-level and school-level surveys to district officials and school principals, respectively. The case studies will consist of a qualitative analysis of interview data and extant documentation, as well as a quantitative analysis of school-level expenditure data. Exhibit 2 shows how the study subquestions map to each of the study data sources.

Exhibit 2. Detailed Study Questions and Associated Data Sources

Detailed Study Questions |

Data Sources |

|||

Survey |

Case Study |

|||

District |

Principal |

Qualitative |

Quantitative |

|

|

||||

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

||||

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

3. How has the implementation of SBB in districts using weights to adjust funding based on student needs affected the distribution of funding provided dollars to schools? |

||||

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

||||

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

Supporting Statement for Paperwork Reduction Act Submission

Description of Statistical Methods

1. Sampling Design

This study will include the following two samples, which will provide different types of data for addressing the study’s research questions.

Nationally representative survey sample. Based on the statistical power analysis below, the study will include a sample of 400 district administrators and 679 school principals within those districts.

Case study sample. A set of nine school districts implementing SBB systems that use weights to adjust funding based on student needs, i.e., WSF districts, which will be the focus of extant data collection as well as interviews with district and school staff.

Nationally Representative Survey Sample

The target population of the nationally representative survey includes all public school districts in the United States serving a large enough enrollment and number of schools that would make adoption of an SBB system a relevant option. Due to the nature of SBB systems, small districts with very few schools are unlikely to consider implementing such policies. Drawing on reports such as the Reason Foundation Weighted Student Formula Yearbook (Snell and Furtick 2013) and the presentation by Koteskey and Snell at the July 2016 Future of Education Finance Summit1, as well as examination of district websites, the study team has identified 31 districts that are currently implementing, have previously implemented, or are actively considering implementing a WSF or SBB system (Exhibit 3). The smallest of these identified districts—New London School District, Connecticut—contained 6 schools and enrolled 3,199 students in 2014–15. Based on this information, we contend that it is unlikely that school districts with fewer than six schools will be SBB implementers. Therefore, we will restrict the target population to those districts that have at least six schools. Districts with a mix of charter and noncharter schools will be included; however, districts consisting entirely of charter schools will be excluded as they may have governance structures and resource allocation mechanisms in place that are different from and not applicable to traditional school districts.

The sample selection for the surveys will be completed in July 2017, subject to OMB approval. The survey sample will be drawn from the 2014–15 Common Core of Data (CCD) Public Elementary/Secondary School Universe Survey conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), which provides a complete listing of all public elementary and secondary schools in the United States.

Exhibit 3. Districts Identified As Currently Implementing, Previously Implemented, or Considering a Weighted Student Funding or Student-Based Budgeting System

District Name |

State |

Enrollment |

Number of Schools |

Urbanicity |

Adams 12 Five Star Schools |

CO |

38,701 |

53 |

Suburb |

Baltimore City Public Schools |

MD |

84,976 |

189 |

City |

Boston Public Schools |

MA |

54,312 |

120 |

City |

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools |

NC |

145,636 |

169 |

City |

Chicago Public Schools |

IL |

392,558 |

603 |

City |

Cincinnati Public Schools |

OH |

32,444 |

56 |

City |

Cleveland Municipal School Dist. |

OH |

39,365 |

102 |

City |

Davidson County (Nashville) |

TN |

84,069 |

164 |

City |

Denver School District |

CO |

88,839 |

191 |

City |

District of Columbia |

DC |

46,155 |

131 |

City |

Douglas County School District |

CO |

66,702 |

89 |

Suburb |

Falcon School District 49 |

CO |

19,552 |

22 |

Suburb |

Hartford School District |

CT |

21,435 |

67 |

City |

Hawaii Department of Education |

HI |

182,384 |

292 |

Suburb |

Houston Independent School Dist. |

TX |

215,225 |

288 |

City |

Indianapolis Public Schools |

IN |

31,794 |

67 |

City |

Jefferson County School District |

CO |

86,581 |

165 |

Suburb |

Milwaukee School District |

WI |

77,316 |

167 |

City |

Minneapolis Public School Dist. |

MN |

36,999 |

96 |

City |

New London School District |

CT |

3,199 |

6 |

City |

New York City Public Schools |

NY |

972,325 |

1,601 |

City |

Newark Public School District |

NJ |

34,861 |

76 |

City |

Oakland Unified |

CA |

48,077 |

130 |

City |

Poudre School District |

CO |

29,053 |

53 |

City |

Prince George's County |

MD |

127,576 |

211 |

Suburb |

Rochester City School District |

NY |

30,014 |

54 |

City |

San Francisco Unified |

CA |

58,414 |

127 |

City |

Santa Fe Public Schools |

NM |

14,752 |

33 |

City |

Seattle Public Schools |

WA |

52,834 |

106 |

City |

St. Paul Public School District |

MN |

37,969 |

104 |

City |

Twin Rivers Unified |

CA |

31,035 |

54 |

Suburb |

A stratified sample of districts with at least six schools will be drawn, stratifying on three student financial need categories (low, middle and high ranges of district-level poverty based on the Census Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates)2, three NCES locale categories (city, suburb, and town/rural combined)3, and two size categories (small/medium and large) so as to allow for meaningful comparisons across these subgroups.4 The 31 districts identified as previously having implemented, currently implementing, or actively considering WSF or SBB will be selected with certainty to guarantee their inclusion in the study (sampling selection probability equal to one). Additionally, the district sample size in each stratum will be determined proportionally to the number of schools within the stratum. Within each of these 18 district strata, the determined number of districts will be selected with probability proportional to the number of schools in the district. If a stratum has fewer than three districts allocated, then the stratum will be combined with a neighboring stratum to avoid the situation in which a stratum may have fewer than two responding districts and strata have to be collapsed after the data collection.

After district selection, schools in the sampled districts within each stratum will be pooled together, and the pooled list of schools will be stratified by school level (elementary, middle, and high school). From the total number of schools included in each stratum, roughly equal number of schools will be sampled with probability proportional to their district sampling weights. In turn, the school selection probability within each schooling level will be equal in the case where the within-district composition of schools with respect to schooling level is equal to that of the district stratum from which they are being sampled. Ten schools will be sampled from 31 districts identified as previously having implemented, currently implementing, or actively considering WSF or SBB, and one school will be sampled from each of the other selected districts.

Due to the clustering of schools within the districts and differential selection probabilities to satisfy sample size requirements for different groups, we expect a design effect (a proportional increase in variance) of between 1.6 and 2.0. Assuming the conservative design effect (2.0) for both the district and school samples, we propose a design with a sample of 400 districts and 679 schools. The target response rates for WSF districts and their schools are 95 percent and 85 percent, respectively, while for non-WSF districts the district- and school-level response rates are 75 percent and 65 percent. The rationale for these response rates is that participation in this study is voluntary and on a topic that may not be perceived as relevant to some respondents. To encourage response, to the study team will provide survey respondents a $25 gift card as a token of appreciation, as well as to conduct a variety of non-response follow-up outreach activities. Given these considerations and efforts, the study team estimates district response rates at 95 and 75 percent for WSF and non-WSF districts, respectively, and principal response rates of 85 and 65 percent for principals in WSF and non-WSF schools, respectively. At these target response rates, we will obtain 306 district responses and 503 principal responses. Given these sample yields, we anticipate estimating, with a 95 percent confidence level, a school-level average response on a dichotomous variable with a value of 0.5 to within plus or minus 0.0618, and a district-level average response on a dichotomous variable with a value of 0.5 to within plus or minus 0.0825.

To better understand and adjust for nonresponse bias, we will identify subsamples of the overall district and school samples (of 30 percent and 20 percent, respectively) with whom we will conduct intensive follow up with those that prove to be non-responsive.5 Specifically, we will reach out to the non-respondents in each of these groups and ask them to complete abbreviated surveys consisting of a small subset of key survey items. This will allow us to compare non-respondents to respondents on these key items and more precisely adjust weights to account for non-response bias.

Sample Preparation. A list of sampled districts will be generated as part of the sampling process. The CCD file contains the addresses and phone numbers for districts and schools, but not the names, titles, or email addresses of key contacts in the district. Therefore, although the CCD data provide a starting point for creating a database of contact information for each sampled district and school, the information is not adequate for administering the study’s survey. In order to ensure that the survey is directed to the appropriate district or school official who can report on the details of the district’s school resource allocation system, the study team will find additional information from state department of education online directories; engage in Internet searches; and, as needed, make phone calls to each of the district’s central offices to identify the official who is in the best position to respond to each survey and to verify this person’s contact phone number and email address. At the district level, this person might be the superintendent, chief academic officer, chief financial officer, or budget manager; at the school level, it might be the principal, assistant principal, or budget manager.

Weighting and Variance Estimation Procedures. Weights will be created for analysis so that a weighted response sample is unbiased. The district and school weights will reflect the sample design by taking into account the stratification and differential selection probabilities, and will include adjustments for differential response rates among different subgroups and adjustments for matching population totals for certain demographic characteristics.

Within each district stratum, the district selection probabilities will be calculated as

where

is

the assigned sample size for district stratum i, and

is

the assigned sample size for district stratum i, and

is

the MOS (measure of size, which is the number of eligible schools in

the district) of district j in district stratum i. The

district base weight is the reciprocal of the district selection

probabilities:

is

the MOS (measure of size, which is the number of eligible schools in

the district) of district j in district stratum i. The

district base weight is the reciprocal of the district selection

probabilities:

.

.

Within each district in the sample, the school selection probabilities will be calculated as

where

is

the sample size (up to two as discussed earlier) for school stratum k

in the district j in district stratum i and

is

the sample size (up to two as discussed earlier) for school stratum k

in the district j in district stratum i and

is

the number of schools in school stratum k in the district j

in district stratum i. The school base weight is the district

base weight times the reciprocal of the school selection probability:

is

the number of schools in school stratum k in the district j

in district stratum i. The school base weight is the district

base weight times the reciprocal of the school selection probability:

.

.

Nonresponse adjustments will be conducted at both

the district and school levels. The nonresponse adjustment factor ( for districts and

for districts and

for schools) will be computed as the sum of the weights for all the

sampled units in a nonresponse cell divided by the sum of the weights

of the responding units in nonresponse cell c. The final

district weight is a product of the district base weight and the

district nonresponse adjustment factor:

for schools) will be computed as the sum of the weights for all the

sampled units in a nonresponse cell divided by the sum of the weights

of the responding units in nonresponse cell c. The final

district weight is a product of the district base weight and the

district nonresponse adjustment factor:

.

.

The final school weight is a product of the school base weight and the school nonresponse adjustment factors:

After the nonresponse adjustment, the weights will

be further adjusted by raking adjustments such that the sum of the

final weights matches population totals for certain demographic

characteristics. The raking adjustment procedure can further correct

for noncoverage, nonresponse, and other types of nonsampling bias due

to noncoverage, nonresponse, and fluctuations in the sampling and

adjustment processes. This procedure iteratively adjusts the weights

until a convergence criterion is reached and the final weights can

produce the marginal distributions of each of the demographic

characteristics adjusted in the procedure. The raked final district

weight is a product of the final district and the raking adjustment

factor ( ):

):

.

.

The raked final school weight is a product of the

final school and the raking adjustment factor ( ):

):

.

.

Standard errors of the estimates will be computed using the Taylor series linearization method that will incorporate sampling weights and sample design information (e.g., stratification and clustering).

Case Study Sample

The study team will select nine case study districts from those known to be distributing funds to schools through a WSF system (i.e., an SBB system that uses weights to adjust school allocations based on student needs). To facilitate the selection process, the study team will review the list of districts presented earlier in Exhibit 3 and determine a short list of those that are currently implementing a WSF systems. The study team will validate this list through documentation scans and follow-up calls to the districts as needed to ensure that each are active WSF implementers with a funding allocation system that uses weights to adjust funding for student needs and is sufficiently different from a traditional model. We will also use this pre-screening as chance to gain a better understanding of the share of operational funding flowing through the WSF system and how these funds are distributed. In total, we anticipate a final list of active implementers consisting of approximately 21 districts, which will serve as the final case study sampling frame. In collaboration with the Department, the study team will select a purposive sample of nine case study districts from the comprehensive list, with the aim of yielding a diverse set of sites with respect to geographic location, age of WSF system, and formula design.

Sample Recruitment, Survey and Case Study

Study Notification Letters/Email. Once the survey and case study sample are selected, a notification letter from the Department of Education will be mailed to the chief state officers/state education agency, followed three business days later by a letter to the district superintendents, informing both of the survey and case studies study activities. The district notification letters will also ask the district to notify the study team if additional research clearance activities are required. We also plan to use email communication and follow-up phone calls to recruit case study sites for the study.

District Research Clearances. The study team also will independently investigate whether any of the districts require advance review and approval of any data collection (surveys and/or case studies) being conducted in their districts. For those districts requiring such advance review and approval, a tailored application will be developed and submitted according to each district’s requirements; typically, the application will include a cover letter, a research application form or standard proposal for research, and copies of the surveys to be administered. Exhibit 4 provides the schedule for the sample recruitment (survey and case studies) and district research clearances.

Exhibit 4. Planned Recruitment Schedule

Event |

Event Date (If Applicable, Number of Weeks After Initial Invitation Letter Sent) |

Select sample |

7/19/17 |

Sample preparation |

7/19/17 – 8/16/17 |

Mail study notification letter from ED to chief state officers/state education agencies (see Appendix A) and district superintendent (see Appendix B) as part of the sample recruitment process.a |

8/16/17 SEA; 8/21/17 District Superintendents |

Identify district research application requirements and obtain clearances. Appendix C presents samples of text to be included in research applications, and Appendix D provides an example research application form from a specific district, Los Angeles Unified School District.a |

Begins 8/21/17 |

Conduct district administrator conversation to recruit for case studies. Appendix E provides example of the introductory invitation email that will be sent prior to any case study telephone conversations.a |

Begins 8/28/17 with districts that do not require a research application |

a. Appendices A -E were submitted with the recruitment and sample attainment OMB package.

2. Procedures for Data Collection

The procedures for carrying out the survey and case study data collection activities are described in the following section.

Survey Data Collection

Nationally representative, quantitative survey data will be collected from a sample of districts and schools. These data will complement the results of the case studies and extant data analyses by providing a higher level, national picture of the prevalence of SBB systems, their implementation, and their challenges. This section describes how survey data collection instruments will be developed, followed by procedures for the collection from the nationally represented sample.

Survey Questionnaire Development. The contractor team will employ a well-tested process for developing the questionnaires. Based on our previous experience developing survey instruments for WSF studies in California and Hawaii, we already have a core set of items across a range of key relevant constructs. The contractor will conduct an extensive review of existing surveys that can serve as sources for valid and reliable items.

We will include questions in the surveys on topics such as the following:

What is the structure of district school funding formulas (including weight structures for WSF districts if applicable)?

What resources do principals report they have authority to allocate?

What is principals’ understanding of how resources are distributed to schools?

Who is involved in school resource allocation decision making?

How long has the WSF or SBB system been in place? (WSF/SBB districts only)

What training and support are provided to principals to build their capacity in making resource allocation decisions?

We will develop an item bank that includes information about all potential items to be used in the survey. In this item bank, we will include the proposed survey item, its source (e.g., the CCD, National Longitudinal Study of No Child Left Behind, and Evaluation of Hawaii’s Weighted Student Funding), the research question(s) the item addresses, any information concerning prior testing or quality of the item, and any additional testing that might be necessary. To the extent that the item requires adaptation of either the question wording or response options to be suitable for use in this study, both the original and revised wording will be documented. The item bank will include not only the content-specific items that will be used to address the study questions, but also appropriate background items, such as the number of current FTEs of district and school staff.

Experience on other PPSS evaluation studies is that existing items from other surveys often require adaptation to better reflect the specific policy being studied or a more nuanced understanding of certain practices. We will evaluate the potential source items and adapt or supplement them with newly drafted items as needed.

Programming and Testing. Upon approval of the final instrument from the study team, senior advisors, ED staff, Institutional Review Board, and OMB clearance, specifications will be written for programmers that include notes on the look and feel of the instruments, skip rules, and fills. The study team will then program the survey in UNICOM® Intelligence™, a survey and sample tracking software that enables a project to program, launch, and track responses to a multimode survey in a single environment. This software will be used to administer the survey, track respondents, send out reminders, and report response rates.

A hard-copy version of the survey will be available for participant review upon request. Respondents will be provided a toll-free number if they have questions about the survey or if they would like to complete the survey over the telephone.

The contractor will design the surveys for the Web mode, which we expect most respondents to use. After the surveys have been extensively tested, the Web instrument will then be adapted for mail and for computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) when we complete the nonresponse bias effort. The adaptations will be made with the goal of maximizing data quality in each mode (Dillman et al. 2014). For example, automatic skips and fills will be used in the Web and CATI modes, while design features will be used to accommodate any complexity in the mail survey instrument.

Before going live, the Web instrument will go through rigorous testing to ensure proper functionality. The online survey will be optimized for completion using mobile devices (e.g., smartphones and tablets), even though we anticipate that most respondents to this survey will complete the survey using either a desktop or laptop computer.

Building Awareness and Encouraging Participation. Survey response rates are improved if studies use survey advance letters from the sponsor of the study or other entities that support the survey (Lavrakas 2008). Therefore, the study team will prepare a draft letter of endorsement for the study from ED that will include the official seal and will be signed by a designated ED official. The letter will introduce the study to the sample members, verify ED’s support of the study, and encourage participation. The study team has submitted this draft letter as part of this package and will customize it as needed prior to contacting each of the respondents.

We also will encourage districts to show support for the principal survey to increase response rates. Some districts may prefer to send an email directly to the sampled principals, post an announcement on an internal website, or allow the study team to attach an endorsement letter from the superintendent or other district official to the data collection materials. To promote effective endorsements and minimize the burden on districts, the research team will draft materials that support the study and provide an accurate overview of the study, its purposes, the benefits of participating, and the activities that are associated with participation.

Following OMB approval and district research clearances, the notification letter from ED will be mailed to districts to encourage their participation will be sent starting in July 2017. We expect to launch the survey in early September 2017. All data collection activities will conclude 19 weeks later in January 2018. Non response bias data collection will take place during the last three weeks of the data collection window. Starting data collection in the fall tends to be more successful due to the many commitments schools and districts have in the spring, such as student testing and planning and budgeting for the following school year. These dates are subject to change and are dependent on OMB approval.

Survey Administration Procedures

District administrators and school principals will be offered varied and sequenced modes of administration because research shows that the using a mixed-mode approach increases survey response rates significantly (Dillman et al. 2014). Different modes will be offered sequentially rather than simultaneously because people are more responsive to surveys when they are offered one mode at a time (Millar and Dillman 2011).

In an effort to minimize costs and take advantage of the data quality benefits of using Web surveys (Couper 2000), the survey will start with a Web-only approach for both district administrators and principals. We expect that both respondent groups have consistent access to the Internet and are accustomed to reporting data electronically. For district administrators who do not respond to electronic solicitations, we will offer the opportunity to complete the survey by telephone. For nonresponsive school principals, the study team will offer the opportunity to complete the questionnaire on paper if they prefer that mode to the online platform. This design is the most cost-effective way of achieving the greatest response rates from both groups.

Web Platform and Survey Access. The contractor currently uses the Unicom software package to program and administer surveys and to track and manage respondents. Unicom can accommodate complex survey formatting procedures and is appropriate for the number of cases included in this study. Respondents will be able to access the survey landing page using a specified website and will enter their assigned unique user ID to access the survey questions. This unique user ID will be assigned to respondents and provided along with the survey link in their survey invitation letter as well as reminder emails. As respondents complete the questionnaire online, their data are saved in real time. This feature minimizes the burden on respondents so that they do not have to complete the full survey in one sitting or need to worry about resubmitting responses to previously answered questions should a session time out or Internet access break off suddenly. In the event that a respondent breaks off, the data they have provided up to that point will be captured in the survey dataset, and Unicom allows them to pick up where they left off when they return to complete the questionnaire.

Help Desk. The contractor will staff a toll-free telephone and email help desk to assist respondents who are having any difficulties with the survey, or request to complete the survey by telephone These well-trained staff members will be able to provide technical support and answer more substantive questions, such as whether the survey is voluntary and how the information collected will be reported. The help desk will be staffed during regular business hours (Eastern through Pacific Time), and we will respond to inquiries within one business day.

Monitoring Data Collection. The study team will monitor Web responses in real time, and completed paper questionnaires will be entered into a case management database as they are received. This tracking of Web and paper completions in the case management database will provide an overall, daily status of the project’s data collection efforts, and enable the team to provide survey response updates to the Department on a regular basis. We will identify district and school administrators who have not yet responded and decide whether additional nonresponse follow-up is needed outside of the activities outlined above. For example, we will attempt to verify that we have correct contact information, make additional follow-up telephone calls, or email the paper questionnaire. The contractor will update PPSS regularly on the survey response rates.

Procedures for Extant Data Collection to Inform Case Studies

The study team will use a comprehensive request for documents (RFD) to collect critical extant data from the case study districts; the RFD will request the types of information needed to investigate the extent to which allocation of funding became more equitable and how the use of resources may have changed after introducing a WSF system. The RFD will request the following documents for the WSF case study districts:

Documents describing how funding and other (personnel and nonpersonnel) resources were allocated to schools

Documents describing the school-level budgeting process, including governance structure, timing, training and support for schools, and roles of district and school staff and other stakeholders in the budgeting process

Information regarding which school-level services were under the discretion of the central office versus school sites prior to and after implementation of the SBB system

Final audited end-of-year school-level fiscal files, including expenditures and revenues for at least five years prior to WSF implementation and for at least five years after implementation (but ideally for all post-WSF years), recognizing that the five-year minimum may not be possible for districts that are more recent implementers

School-level budgets and budget narratives for at least three years prior and three years after (if available) WSF implementation

School improvement plans or other program plans

RFDs will be sent to district staff via email only after the district has agreed to participate. To place minimal burden on those providing the data, the study team will ask providers not to modify the information they provide but instead to send extant materials in the format most convenient for them. The RFD also will include instructions for providing this information via a File Transfer Protocol (FTP) site or other secure transfer method. The administration of the RFD will mark the beginning of the case study data collection, which is expected to start in fall 2017.

Procedures for Case Study Site Visit and Interview Data Collection

In each case study district, the study team will conduct on-site interviews with a district program officer, district finance officer, and three school principals. Additionally, if time permits the study team will hold on-site interviews with respondents in two of the following three groups— a union representative, school board member, or an additional district administrator—depending on the union’s presence in the district and which respondents are most knowledgeable about the WSF system. If there is not enough time to perform these interviews on site, the research team will conduct the two interviews over the phone. As necessary, the study team will conduct follow-up telephone interviews for the purpose of obtaining key missing pieces of information, but we will seek to limit this practice.

Training for Site Visitors. Before site visits begin, all site visit staff will participate in a one-day in-person or webinar site visit training to ensure understanding of the purpose of the study, content of the protocols, and interview and site visit procedures. In addition, staff will discuss strategies for avoiding leading questions, ensuring consistency in data collection, and conducting interviews in a way that is conversational yet still directed toward collecting the intended information systematically. Important procedural issues to be addressed during training include guidelines for ensuring respondent privacy, guidelines for ensuring high-quality interview notes, and follow-up communications with district and school staff. Staff will be trained to probe thoroughly for detailed answers to questions and how to follow up on vague answers.

Scheduling Site Visits and Interviews. To ensure the highest quality data collection, each site visit will be conducted by two site visitors. Each site visit pair will be responsible for scheduling the visits and interviews within those visits for their assigned sites. Because of differences in district sizes and structures, some job titles and roles of interviewees may vary across sites. Pairs will work with a point person in each district and school to identify the best respondents prior to the site visit and develop a site visit and interview schedule. We anticipate that each site visit will take only one day. Exhibit 5 presents a sample interview schedule during a site visit.

Exhibit 5. Sample Interview Schedule

Task |

Time |

On-Site During Visit |

|

Interview with district program officer |

7:30–9:00 a.m. |

Interview with district finance officer |

9:00–10:00 a.m. |

Interview with union representative |

10:00-10:45 a.m. |

Interview with school board member |

10:45–11:130 a.m. |

Interview with school principal 1 |

11:45 a.m.–12:45 p.m. |

Lunch break/ travel to school 2 |

|

Interview with school principal 2 |

1:15–2:15 p.m. |

Travel to school 3 |

|

Interview with school principal 3 |

2:45–3:45 p.m. |

Conducting Interviews. Before visiting sites, we will ask the district official in each case study district most knowledgeable about the WSF system to complete a preinterview questionnaire through a simple Web survey platform such as Survey Gizmo. The information gathered will provide the research team with an initial introduction to each case study district’s WSF system, including the structure of the WSF formula, longevity of the system, and challenges the district has experienced implementing the system. Site visitors will review information from extant documents collected through the RFD and the preinterview questionnaires as to help inform and save time during the interviews that will take place during the site visit.

Interview protocols will be designed to elicit clear, specific, and detailed information from respondents. However, interview responses can be difficult to interpret when acronyms are used or prior knowledge is assumed. The study team will seek detailed responses from interviewees; when responses are vague, interviewers will probe carefully and thoroughly as trained using probes contained in the protocols and strategies covered in the site visitor training. If it becomes clear during the analysis process that information provided by the respondent does not fully address the question, the team will contact the respondent again to ask clarifying questions via phone or email. During data collection, we will ask permission from all respondents to contact them later with follow-up questions if needed.

Data Management. In preparation for the site visits and while on-site, the study team will use Microsoft OneNote to organize extant data, interview protocols, and audio files. OneNote enables audio data to be synchronized with interview notes, allowing the researchers to create an accurate transcript of each interview or focus group. The study team will record each interview (pending consent of the interviewee) and send the audio files to a professional transcription service. The contractor will then prepare de-identified transcripts for delivery to PPSS to enable them to monitor the completeness of the response to each question.

Extant data will be received through multiple vehicles, sometimes by email, sometimes through FTP site, and, if needed, by mail on a disk. We anticipate receiving documents and files in multiple rounds and over the course of about a one-month period. A research assistant on the team, designated as the extant data manager, will carefully track these incoming data and save them in district-specific folders in the project’s folder on a secure network drive. Only study team members who have been trained in data security procedures will have access to these folders. Once final documents have been received from a given site, they will be copied into OneNote so that all relevant documents are in one place for each case.

Quality Control. The case study site visit and interview data collection process will include the following quality control procedures: (1) weekly site visit debriefings among the team to identify and discuss logistical and data collection concerns; (2) a formal tracking system to ensure that we are collecting all parts of the required data from each site; and (3) adherence to the timely cleaning and posting of interview notes and written observations, as well as interview audio transcripts, to a secure project website for task leaders to check for completeness and consistency.

3. Methods to Maximize Response Rates in the Survey

Response Rates and Nonresponse Bias. In contrast to many other PPSS studies in which grantees are required by law to participate, this study is voluntary. When sampled district staff and principals refuse to participate, we will make many attempts to convert their refusal to cooperation using evidence-based methods as described below. We expect to see increases in response rates as a result of these design features, but we expect that response rates will be lower than mandatory PPSS studies.

Still, although the response rate is an important data quality indicator, its relationship with nonresponse error is tenuous, as nonresponse error only occurs when the nonrespondents differ systematically from respondents on characteristics of interest (Groves, 2006; Groves and Peytcheva, 2008). The study team will make weighting adjustments to reduce nonresponse error as described in the Sampling Design section in Part A.

In addition to post-survey weighting adjustments, this study will incorporate a variety of evidence-based methods to increase response rates. In this section we describe the procedures we will use to do so.

Keeping the survey instrument brief and as easy as possible to complete. The team will draw upon its past experience in developing data collection instruments that are designed to maximize response rates by placing as little burden on respondents as possible, as well as by tailoring each instrument to be appropriate for the particular type of respondent. The team will also use cognitive interviews with principals and district administrators to pilot survey data collection instruments to ensure that they are user‑friendly and easily understandable, all of which increases participants’ willingness to participate in the data collection activities.

Using multiple contact attempts to reach individuals. This study will incorporate a variety of contacts and reminders (see Exhibit 6). First, a survey invitation letter will be sent using both mail and email to all principals and selected district respondents. These letters and emails will include a link to the Web survey and a request to participate. Then during a 16-week period we will send a maximum of eight email reminders and conduct three rounds of telephone reminder calls to all nonrespondents to help encourage participation. ED will send two reminders (one mailing will contain a copy of the survey, and one email reminder) to encourage districts and principals to respond if they have not yet participated. This strategy was successful on two other PPSS studies: Study of Title I Schoolwide and Targeted Assistance Programs and Study of the Teacher Education Assistance for College and Higher Education Grant Program.

After week 16, we will conduct a small nonresponse bias experiment to determine if the district and principal staff who respond are different from the district and principal staff who did not respond on selected variables of interest. To determine this, three additional contact attempts will be made to 30 percent of district subjects and 20 percent of the principal subjects who fail to respond by week 17, to ask them to respond to a shortened set of key survey questions. This strategy has been used in other studies to estimate nonresponse bias in key survey estimates (e.g., Curtin et al., 2005). We will additionally send an e-mail in week 17, mail a hard-copy survey in week 18 and conduct telephone calls in Week 19.

Exhibit 6. Survey Data Collection Timeline

Event |

Event Date (If Applicable, Number of Weeks After Initial Invitation Letter Sent) |

Mail survey notification/advance letters from ED to District Administrators and Principals as part of the survey notification process (See Appendix F) |

10/27/2017 |

Mail/email Web invitation sent |

11/01/2017 |

Reminder email sent (maximum eight) |

Starting on 11/08/2017(1 Week) Ending on 02/14/2107 (15 weeks) |

Telephone nonresponse (maximum three rounds) |

11/15/2017 (2 Weeks) 11/29/2017 (4 Weeks) 1/03/2018(9 Weeks) |

Paper questionnaires mailed (two times, second by ED) |

12/13/2017 (6 Weeks) 1/10/2017(10 Weeks) |

Final reminder email by ED |

2/21/2018 (16 Weeks)6 |

NON RESPONSE BIAS FOLLOWUP |

|

Nonresponse follow-up: Email reminder |

2/28/2018 (17 weeks) |

Nonresponse follow-up: Paper questionnaires mailed |

3/7/2018 (18 weeks) |

Nonresponse follow-up: Telephone completes |

3/14/2018 (19 weeks) |

Sending notification letters. Notification letters will be printed on Department of Education letterhead and will be sent to states, districts, and schools through a staggered process described above. Prior research has found that notification letters, particularly from an authoritative source, can increase response rates (e.g., Groves, 2006; Dillman et al., 2014).

Offering different modes for completion. Research shows that the using a sequential mixed-mode approach—a design in which a second or subsequent mode of administration is used to recruit nonrespondents—is a cost-efficient method to significantly increase survey response rates relative to using a single mode (Dillman et al. 2014). The subsequent mode used tends to have higher costs associated with it but also tends to result in higher response rates than the first mode. In this design, we begin with a relatively inexpensive Web survey, followed by a mail survey for nonrespondents to the Web survey. A wealth of research has indicated that these designs can also increase response rates in a cost-effective manner (e.g., Beebe et al., 2007; de Leeuw, 2005).

Offering incentives. As noted in Part A, district and principal respondents that satisfactorily complete and submit a survey will receive $25.00 gift cards as a token of appreciation for their time and effort. Research has shown that providing incentives can increase response rates (Dillman et al., 2014; Groves et al., 2000; Singer, 2002; Singer and Ye, 2012).

There will be no increase in the study budget; other slight adjustments to the allocation of contract funding will be made in order to free up the funds for the incentive payments. In addition, the cost may be offset because fewer telephone follow-ups are expected to be necessary.

4. Expert Review and Piloting Procedures

To ensure the quality of the data collection instruments, the study team will solicit feedback on survey items from technical working group (TWG) members and well as current and former district and school staff ensure the drafted items that will result in high-quality data to address the study’s research questions. The TWG members include two university professors, each with research expertise in educational resource allocation, WSF and SBB systems, and related policy; and three practitioners (two at the district level and one at the state level) who have been directly involved in the implementation of WSF and SBB systems. We solicited feedback on survey items from the TWG members during an in-person meeting in March 2017. We have revised the survey items based on their initial feedback and will continue to consult with the group as needed. The study team will also conduct cognitive interviews with a limited set of principals and district officials to pilot the survey items, again respecting limits regarding the number of respondents prior to OMB clearance.

5. Individuals and Organizations Involved in the Project

AIR is the contractor for the study. The project director is Dr. Jesse Levin, who is supported by an experienced team of researchers leading the major tasks of the project. Contact information for the individuals and organizations involved in the project is presented in Exhibit 7

Exhibit 7. Organizations and Individuals Involved in the Project

Responsibility |

Contact Name |

Organization |

Telephone Number |

Project Director |

Dr. Jesse Levin |

AIR |

(650) 376-6270 |

Deputy Project Director |

Karen Manship |

AIR |

(650) 376-6398 |

Senior Advisor |

Dr. Kerstin Carlson LeFloch |

AIR |

(202) 403-5649 |

Senior Advisor |

Dr. Jay Chambers |

AIR |

(650) 376-6311 |

Senior Advisor |

Dr. Sandy Eyster |

AIR |

(202) 403-6149 |

Case Study Task Lead |

Steve Hurlburt |

AIR |

(202) 403-6851 |

Survey Task Lead |

Kathy Sonnenfeld |

AIR |

(609) 403-6444 |

Consultant |

Dr. Bruce Baker |

Graduate School of Education at Rutgers University |

(848) 932-0698 |

Consultant |

Matt Hill |

Burbank Unified School District |

(818) 729-4422 |

References

Beebe, T. J., Locke, G. R., Barnes, S., Davern, M., & Anderson, K. J. (2007). “Mixing Web and Mail Methods in a Survey of Physicians”. Health Services Research, 42(3), 1219-34.

de Leeuw, E. D. (2005). “To Mix or Not to Mix Data Collection Modes in Surveys”. Journal of Official Statistics, 21(2), 233-255.

Couper, Mick P. 2000. “Web Surveys: A Review of Issues and Approaches.” Public Opinion Quarterly 64 (4): 464–94.

Curtin, R. Presser, S., and Singer, E. (2005). “Changes in Telephone Survey Nonresponse over the Past Quarter Century.” Public Opinion Quarterly, 69: 87-98.

Dillman, Don A., Jolene D. Smyth, and Leah Melani Christian. 2014. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Groves, R. M. 2006. Nonresponse Rates and Nonresponse Bias in Household Surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70(5), 646-675.

Groves, R. M. and Peytcheva, E. 2008. The Impact of Nonresponse Rates on Nonresponse Bias: A Meta-analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(2), 167-189.

Groves, R. M., Singer, E., Corning, A. D. (2000). “Leverage-Salience Theory of Survey Participation: Description and an Illustration”. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64 (3): 299–308.

Singer, E. (2002). “The Use of Incentives to Reduce Nonresponse in Household Surveys.” In Survey nonresponse, eds. Groves, R. M., Dillman, D. A., Eltinge, J.L., Little, R. J. A., pp.163–78. New York, NY: Wiley.

Singer, E., Ye, C. (2012). The Use and Effects of Incentives in Surveys. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 645(1), 112-141.

Honig, Meredith I., and Lydia R. Rainey. 2013. “Autonomy and School Improvement: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go From Here?” Educational Policy 26(3): 465-495.

Lavrakas, Paul J. 2008. Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Koteskey, Tyler, and Lisa Snell. 2016. Trends in the National Student-Based Budgeting Landscape: Exploring Best Practices and Results (Presentation. http://allovue.com/files/fefs2016/session-d/trends-sbb/trends-sbb-fefsummit.pdf

Millar, Morgan M., and Don A. Dillman. 2011. “Improving Response to Web and Mixed-Mode Surveys.” Public Opinion Quarterly 75 (2): 249–69.

Mizrav, Etai. 2014. Could Principal Autonomy Produce Better Schools? Evidence From the Schools and Staffing Survey. https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/709855

Roza, Marguerite, Tricia Davis, and Kacey Guin. 2007. Spending Choices and School Autonomy: Lessons From Ohio Elementary Schools (Working Paper 21). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Center on Reinventing Public Education, School Finance Redesign Project. http://www.crpe.org/sites/default/files/wp_sfrp21_rozaohio_jul07_0.pdf

Roza, Marguerite, and Paul T. Hill. 2003. How Within-District Spending Inequities Help Some Schools to Fail (Brookings Conference Working Paper). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Center on Reinventing Public Education.

Snell, Lisa, and Katie Furtick. 2013. Weighted Student Formula Yearbook 2013. Washington, DC: Reason Foundation.

Steinberg, Matthew P. 2014. “Does Greater Autonomy Improve School Performance? Evidence From a Regression Discontinuity Analysis in Chicago.” Education Finance and Policy 9 (1): 1–35. http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/EDFP_a_00118

1 See Koteskey and Snell’s (2016) Trends in the National Student-Based Budgeting Landscape: Exploring Best Practices and Results presentation.

2 Poverty levels—low, middle, high—were determined using enrollment-weighted quartiles of the Census Small Area Income Population Estimates (SAIPE) district-level poverty estimates. Low represents the bottom quartile, middle consists of both the second and third quartiles, and high is made up of the top quartile. Quartiles were calculated according to PPSS guidelines and prior to excluding districts with fewer than six schools.

3 We will combine town and rural district into a single locale category for the purposes of stratification due to the exclusion of large numbers of town and rural districts that have fewer than six schools.

4 PPSS guidelines define small districts as those with less than 2,500 students, medium districts as those with enrollments of at least 2,500 and less than 10,000 students, and large districts as having at least 10,000 students. The exclusion criterion of having at least six schools substantially reduces the number of small districts; therefore, we will combine small and medium-sized districts into a single size category for the purposes of stratification.

5 The expected numbers of non-repsondent districts and schools with which we will conduct intensive follow up is 26 and 35, respectively.

6 Reminder messages resume after the holiday break.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| File Title | OMB Part B |

| Author | American Institutes for Research |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-22 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy