Supporting Statement Part A - POD (0960-NEW) - Revised

Supporting Statement Part A - POD (0960-NEW) - Revised.docx

Promoting Opportunity Project (POD)

OMB: 0960-0809

Supporting Statement for Promoting Opportunity Demonstration (POD)

OMB No. 0960-NEW

PART A: JUSTIFICATION

A.1. Introduction and authoring laws and regulations

A.1.1. Overview

The Social Security Administration (SSA) is requesting clearance to collect data necessary to conduct a random assignment evaluation of volunteers in select sites who enroll in the Promoting Opportunity Demonstration (POD). The evaluation will provide empirical evidence on the impact of the intervention for the subjects who receive Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) benefits and their families in several critical areas: (1) increased employment, (2) increased number of employed beneficiaries who have substantive earnings, (3) reduced benefits, and (4) increased beneficiary income (earnings plus benefits).

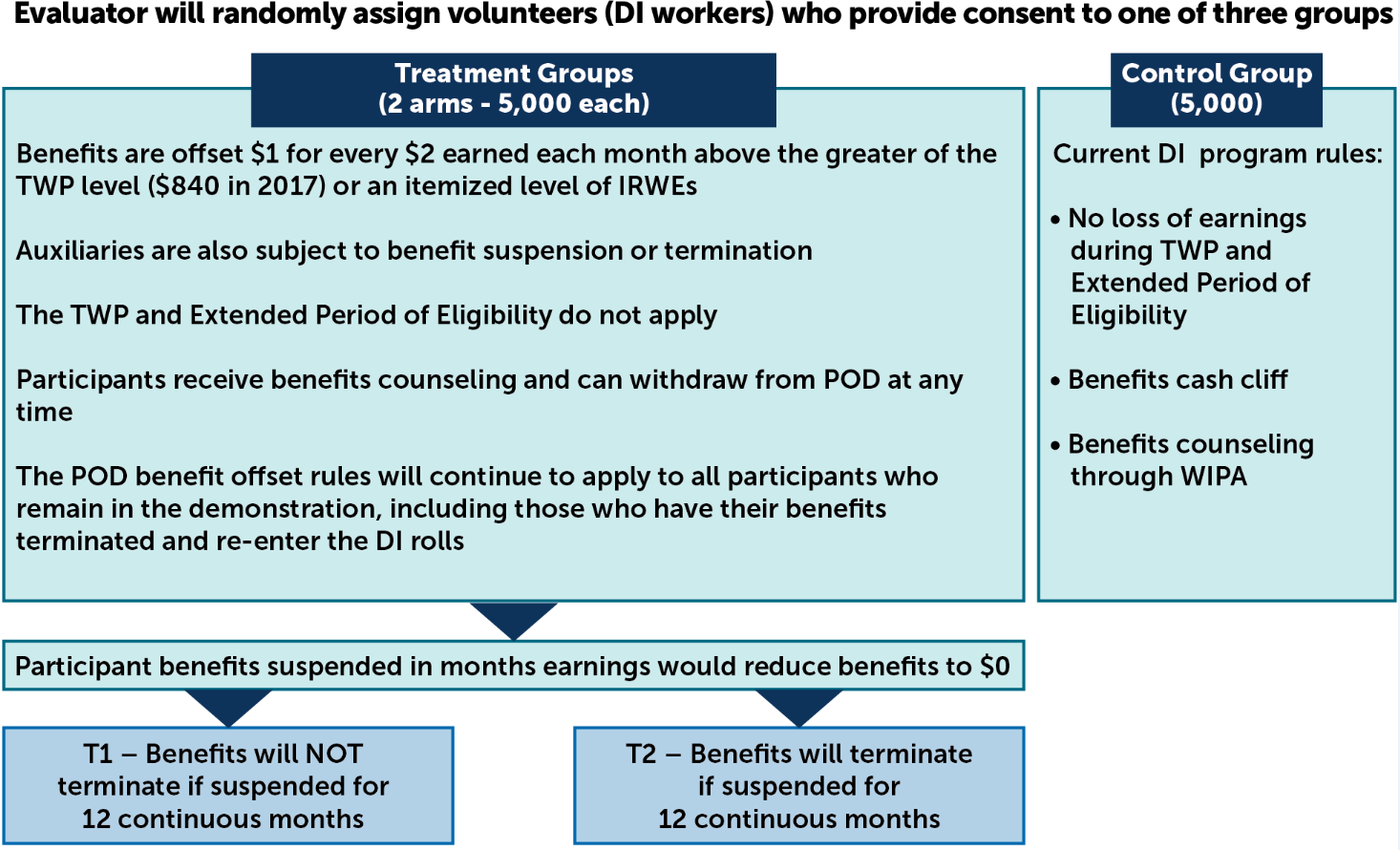

Because they are volunteers, the POD subjects will self-select into the study. Upon entering the study, they will be randomly assigned to one of two treatment arms or one control arm. We refer to beneficiaries randomized into the demonstration as treatment and control subjects. Both treatment arms include a benefit offset of $1 for every $2 earned above the larger of the Trial Work Period (TWP) level (defined as $840 in 2017) and the amount of the subject’s Impairment-Related Work Expenses (IRWE). They differ in the way they administer policies involving cases that reach full benefit offset (that is, benefits reduced to zero). In both treatment arms, POD initially suspends benefits. However, in one arm the suspension has no time limit whereas in the other arm, POD terminates benefits after 12 consecutive months of suspension. Beneficiaries in the control arm receive services available under current law. Exhibit A.1 summarizes the services the two treatment groups and the control group receive.

The demonstration will include approximately 15,000 SSDI subjects, 5,000 in each treatment group and 5,000 in the control group, across the eight selected POD states. The eight states include Alabama, California, Connecticut, Maryland, Michigan, Nebraska, Texas, and Vermont. The POD implementation contractor, Abt Associates, chose these states according to substantive and practical criteria that relate to their capacity to carry out the demonstration. Part B of this package provides more information about how Abt chose these states.

WIPA = Work Incentives Planning and Assistance program.

The Social Security Administration is conducting the study and our recruitment contractor, Mathematica, is carrying out components of the evaluation on behalf of SSA. Hereinafter, this will be referred to as “the POD evaluation team” or, when clear from context “the evaluation team.” The evaluation will include an assessment of the implementation of POD and its effectiveness for the 15,000 subjects enrolled in the eight POD states. The conclusions drawn from the evaluation represent results only for the voluntary population of this study. SSA believes the study may yield useful insights on the potential effectiveness of the new work rules and future research on Administration programs. The POD evaluation team will base this assessment on analyses of data from the following sources:

Recruitment materials and baseline survey. The recruitment materials will include a letter describing POD; baseline survey; consent form; and brochure. The letter and brochure will provide background information about the demonstration. Beneficiaries who are interested in participating will complete the baseline survey and the consent form to apply for the demonstration. The short survey will provide information on a set of beneficiary characteristics that do not appear in SSA program data. These materials are in Appendix A.

Two follow-up surveys. The POD evaluation team will administer the Year 1 follow-up survey to treatment and control subjects 12 months after their study enrollment date. The POD evaluation team will conduct the Year 2 follow-up survey 24 months after enrollment. The two surveys have similar content and will collect information on important study outcomes, which the evaluation team cannot use program data to measure. The survey instruments and contact materials are in Appendix B.

Four rounds of qualitative data from POD implementation and operations staff. The POD evaluation team will conduct two rounds of in-person site visits and two rounds of “virtual” interviews (follow-up telephone calls) with field staff to assess the process of POD implementation. The evaluation team anticipates conducting in-person visits for the first and third rounds of data collection when key informants are working centrally on site at the vocational rehabilitation (VR) agency. However, in states that rely more on telecommuting staff, the evaluation team will collect information by telephone in these rounds to reduce the cost of interviewing geographically dispersed respondents. The first round of in-person site visits will occur early in the implementation period before the end of recruitment and the second round will occur in the middle of program operations. If feasible, the virtual interviews will include videoconferences. In these interviews, the evaluation team will use semi-structured protocols to collect information from key respondents identified during the first round of in-person visits. The first round of virtual interviews will occur upon completion of random assignment and the second round will occur toward the end of the program implementation period. Interview topics for the in-person and virtual interviews are in Appendix C.

Two rounds of semi-structured interviews with treatment group subjects. The evaluation will use two rounds of semi-structured telephone interviews with subjects to obtain information about their perspective about implementation to supplement the data from the four rounds of process data collection noted above. The first round, which will occur at the same time as the virtual interviews at the end of recruitment noted above, will focus on subjects’ motivations for enrolling; their perceptions of the outreach, recruitment and enrollment processes; their employment goals; and their expectations of the demonstration. The second, which will occur at the same time as the in-person visits during program operations noted above, will capture their perspectives on services received, experiences with the offset, and work experiences. Interview topics for these semi-structured interviews are in Appendix D.

POD Monthly Earnings and Impairment-Related Work Expenses (IRWE) Reporting. The POD evaluation team will collect monthly earnings and IRWE from participants whose monthly earnings exceed the POD threshold. Each month, participants will use a form to provide their employers’ names, along with their earnings from each employer and any IRWEs they claimed that month. Participants will also submit documentation to the POD evaluation team, such as paystubs and receipts for IRWEs. This will allow the POD evaluation team to evaluate the subset of POD participants whose earnings exceed the POD threshold.

POD End of Year Reporting (EOYR). Beginning in 2018, the POD evaluation team will send a form every February to collect additional earnings or IRWEs that the respondents did not report during the prior year to those participants whose monthly earnings exceed the POD threshold. Along with the form, participants will also submit additional paystubs and IRWE documentation they did not submit previously. This will allow the POD evaluation team to evaluate the subset of POD participants whose earnings exceed the POD threshold.

Exhibit A.2 summarizes the time frames over which SSA and its contractor anticipate using these materials to collect information.

Exhibit A.2. Timeline for data collection efforts

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

||||||||||||

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q1 |

|

Recruitment materials and baseline survey |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Follow-up surveys |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Year 1 survey |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

Year 2 survey |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Qualitative data from POD implementation and operations staff |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

Semi-structured interviews with treatment group subjects |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

POD Monthly Earnings and Impairment-Related Work Expenses (IRWE) Reporting |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

POD End of Year Reporting (EOYR) |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

A.1.2. Background

Congress required SSA to implement and evaluate POD for voluntary subjects. As part of the Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) of 2015 (Public Law 114-74), Section 823, policymakers required SSA to carry out POD to test a new benefit offset formula for SSDI beneficiaries who volunteer to be in the study. The new rules, which also simplify work incentives, aim to promote employment and reduce dependency on benefits.

Section A22 of Public Law 114-74 requires that participation in projects such as POD be voluntary and include informed consent. As will be discussed below, this feature of the law is important because it prescribes how SSA can implement the demonstration, which has implications for the interpretation of the evaluation findings. The degree of interest among potential volunteers and their decisions to participate are of policy interest, particularly because some beneficiaries might not benefit from the proposed interventions. Consequently, an important component of the POD evaluation will be to assess the number and types of beneficiaries who come forward to participate in the demonstration.

In addition, Public Law 114-74 specifies that study volunteers assigned to a treatment group have the right to revert from the new POD rules to current SSDI rules at any point. Section B includes more discussion of this requirement and its implications for the evaluation.

POD is part of a broader effort by policymakers to identify new approaches to help beneficiaries and their families – many of whom are low income – increase their incomes and self-sufficiency through work. In addition to authorizing POD, the Bipartisan Budget Act extended the solvency of SSDI until 2023 and renewed SSA’s demonstration authority (section 42 U.S.C. 434 of the United States Code). The renewed authority allows SSA to carry out experiments and demonstration projects promoting labor force attachment and identifying mechanisms that could result in savings to the SSDI trust funds. Hence, POD will be one of many possible demonstration projects SSA will conduct.

POD attempts to address complexities with the current law’s work rules. A policy concern is that existing work rules for SSDI beneficiaries are complex and include provisions that result in a complete loss of SSDI benefits for sustained earnings above a certain level—commonly referred to as a cash cliff. (A literature review on the SSDI program and other disability benefits programs follows this section.) One complexity is that current rules change depending on the beneficiary’s work history. For example, the current rules do not result in any reductions for earnings among beneficiaries who initially return to work and have relatively low earnings. Those who earn below a threshold amount have no subsequent changes to their benefits, and those with higher earnings enter what SSA refers to as the Trial Work Period (TWP). As of 2017, the TWP threshold was $840 per month. However, the rules change following the TWP (Exhibit I.1). Ultimately, SSDI beneficiaries who work over longer periods and earn wages above the Substantial Gainful Activity (SGA) threshold, defined in 2017 as $1,170 per month for non-blind beneficiaries and $1,950 per month for blind beneficiaries, risk the complete loss of benefits. Researchers and administrators refer to this benefit loss as a cash cliff because beneficiaries lose all benefits for a single dollar of earnings in excess of SGA.

The complexity of the current rules creates challenges for beneficiaries and SSA staff. For beneficiaries, the complexity of the work rules creates concerns about returning to work (Wittenburg et al. 2013). For example, beneficiaries might fear returning to work because they could lose both their SSDI benefit and Medicare eligibility if their earnings exceed the SGA threshold (the cash cliff). In addition, beneficiaries who do not fully understand the current rules risk incurring overpayments, which they will have to pay back to SSA (see Hoffman et al. 2017 for more details). Administratively, SSA staff must record beneficiaries’ earnings, which can be complicated if beneficiaries do not regularly report their earnings to SSA.

POD attempts to address these challenges by creating a simplified set of new work rules that replace the cash cliff with a ramp, which we refer to as a benefit offset (Exhibit I.1). Under POD, the rules do not change depending on the beneficiary’s work history because it eliminates the TWP and Grace Period. The new offset formula reduces benefits by $1 for every $2 of earnings in excess of a TWP level (defined as $840 in 2017).

Exhibit I.1. Snapshot comparison of current rules and the new POD rules

Current rules |

New POD rules |

|

|

POD adds distinctive information to what has been learned from previous SSA research on disability employment programs and policies. The largest evaluations of employment supports for people with disabilities have emphasized approaches targeting people who receive SSDI and/or Supplemental Security Income (SSI). SSDI and SSI beneficiaries are a natural target population for services because they represent the largest federally funded cash transfer programs for people with disabilities.

In 1980, Congress authorized SSA to test SSDI demonstration projects over a five-year period and to test SSI demonstration projects permanently (Szymendera 2011). SSA could use this authority to temporarily waive certain program rules and allocate trust fund dollars and appropriated funds to finance demonstrations. The authority required that the demonstrations have sufficient scope and scale to facilitate a thorough evaluation of the program or policy change under consideration.

The Ticket to Work (TTW) and Work Incentives Improvement Act of 1999 (Ticket Act) developed a major return-to-work program to promote employment by beneficiaries. Specifically, the Ticket Act established the TTW program, which provides SSDI and SSI beneficiaries with a voucher, or ticket, to purchase public or private sector employment services. As noted in the Ticket Act, even a small increase in exit rates from SSDI and SSI could result in large programmatic savings. The reason for the large potential savings is because most SSDI and SSI participants receive benefits for several years and the most likely reasons for leaving the programs are either death or retirement. Annual exits from SSDI and SSI due to work have generally persisted at 0.5 percent for years, even in the face of numerous programmatic and economic changes (Berkowitz 2003; Newcomb et al. 2003). Following the passage of the Ticket Act, SSA launched several major employment demonstrations projects and programs. Several focused on providing employment supports, whereas others focused on the disability determination processes and providing health benefits (Wittenburg et al. 2013). In designing these demonstration projects, SSA sought to test how the interventions influenced the multiple work barriers faced by the heterogeneous SSDI and SSI beneficiary populations. Consequently, some interventions targeted rehabilitation supports (for example, beneficiaries in the TTW program), whereas others attempted to provide enhanced work incentives and/or most customized supports to specific subgroups, such as those with psychiatric impairments and youth with disabilities.

The largest work incentive demonstration was SSA’s Benefit Offset National Demonstration (BOND), which replaced the cash cliff with a different offset ramp than what is tested in POD; BOND also tested additional supports.1 BOND is a random assignment evaluation that tests whether replacing the SGA cash cliff with a $1-for-$2 offset ramp would increase work and reduce beneficiaries’ reliance on SSDI benefits. BOND changed the accounting period from monthly to annually and replaced the cash cliff with a $1-for-$2 benefit offset that gradually reduces benefits when earnings surpass the annual equivalent of the SGA amount. This is unlike POD, which bases the offset ramp on monthly earnings and begins at the lower TWP amount. As discussed below, a later phase of BOND also included a treatment arm that tested the added effect of enhanced work incentives counseling to help beneficiaries better understand the demonstration’s rules.

The BOND study features two stages that both include random assignment evaluations. SSA randomly selected 10 Area Offices to conduct BOND. Stage 1 provides estimates of the impacts of the BOND offset on the national beneficiary population. Participation in BOND Stage 1 was mandatory, and the Stage 1 sample includes a nationally representative sample of the SSDI beneficiary population who were younger than 60 at the start of BOND and older than 20. SSA designed Stage 2 of BOND to more carefully examine impacts among those beneficiaries who seem most likely to use the offset, using informed and recruited volunteers selected from a solicitation pool established from the Stage 1 sample. The study sample for Stage 2 comprises informed SSDI volunteers. Unlike POD, BOND Stage 2 includes SSDI-only beneficiaries and excludes concurrent beneficiaries. The counseling enhancements provided to Stage 2 treatment group members go substantially beyond the standard counseling services provided under current law (including the BOND control groups) and to the Stage 1 treatment subjects, featuring proactive initial and follow-up outreach by the counselors and several enhancements to the counseling itself.

Early results suggest the BOND offset has had limited impacts on earnings in the short term, and benefit payments have increased in the short term (Wittenburg et al. 2015; Gubits et al. 2014). The evaluation findings also showed long administrative delays in adjusting benefits following changes in earnings. These latter findings underscore some of the complexities of BOND rules. Specifically, the BOND rules keep elements of the current law’s rules (for example, the Extended Period of Eligibility) and include an annualized version of earnings (annual SGA) that potentially added to the delays given the complexity of these calculations.

The intervention for POD addresses the perception that BOND rules were complex using a more simplified set of administrative adjustments in implementing a $2-for-$1 offset. Specifically, the new POD rules eliminate the TWP and Grace Period, which effectively make the new POD offset rules consistent throughout the entire demonstration period for all beneficiaries unless their benefits are terminated. This change differs from current rules (and the rules under BOND) because beneficiaries experience different work incentive rules following the Grace Period. To expedite the processing of the new POD rules, the implementation contractor (Abt) is engaging with the state VR and Work Incentive Planning and Assistance agencies. In addition, the POD rules start the offset at the monthly TWP threshold, which will generally mean lower earnings than the annualized SGA amount used to trigger the offset under the BOND rules.

Similar to BOND, the POD evaluation is designed to produce internally valid impact estimates using random assignment, though POD’s includes only volunteers and is being implemented under different conditions. The requirement to include volunteers makes POD more similar to the BOND Stage 2 sample. However, the purposive selection of the sites in POD differs from the random sampling that BOND used. In addition, the two demonstrations will be carried out under markedly different general economic conditions—with BOND Stage 2 enrollment occurring during the slow recovery following the Great Recession. Finally, the recruitment of sample members in POD also differs in important ways from BOND.2 All of these factors make direct comparisons of study subjects and volunteer rates challenging across demonstrations. Further, as already noted, POD implements a different set of work-incentive rules than BOND used. Hence, the POD evaluation will provide substantively new information that can help SSA meet the congressional mandate to assess voluntary participants in the study of a new set of rules and the impacts of those rules on study subjects.

Overview of POD implementation and evaluation. The POD implementation team, which includes Abt and its state VR and Work Incentive Planning and Assistance agencies, will collect and coordinate the subjects’ earnings information and transmit the information to SSA for timely benefit adjustments. Given the usual workloads of these state partners, they will likely be the primary source for benefits counseling and employment services for subjects. It will be important to assess how the state implementation partners respond to this significant opportunity to enhance the services they provide to SSDI beneficiaries.

The evaluation will assess the effect of POD services on employment, earnings, and benefit payments. It will include the following four components (see Exhibit A.3):

A process analysis will describe the components of POD’s infrastructure and assess the functioning and implementation of each component. It will document the program environment, beneficiaries’ perspectives on the POD offset, and the fidelity of program operation to the offset design. It will also seek to determine the extent of any problems the POD evaluation team might detect, and whether they will affect the impact estimates.

A participation analysis will examine recruitment, withdrawal, and use and nonuse of POD’s services and the benefit offset. The first component of the analysis will compare the study subjects’ characteristics with those of nonparticipants in the recruitment pool. The second component will compare treatment subjects who remain in their treatment arm with those who withdraw from it separately for the two treatment groups. The third component will examine how beneficiaries in the treatment groups use demonstration services and the offset, including the extent to which they report earnings each month, receive benefits counseling and earn enough to have benefits reduced or terminated under the offset.

An impact analysis will leverage the experimental design to provide internally valid quantitative estimates of the effects of the benefit offset and benefits counseling on the outcomes of subjects. Because the study is using random assignment, the treatment and control groups will have similar observed and unobserved characteristics, on average, when they enter the study. Hence, the evaluation’s impact estimates will provide an unbiased assessment of whether the benefit offset can help SSDI beneficiaries who volunteer achieve greater economic self‑sufficiency and other improvements in their lives. In addition, information from the process and participation analyses will inform understanding of POD’s impacts, and the results from the impact evaluation will support the calculation of POD’s costs and benefits.

A cost-benefit analysis will assess whether the impacts of the POD treatments on subjects’ outcomes are large enough to justify the resources required to produce them. By placing a dollar value on each benefit and cost of an intervention, a cost-benefit analysis can summarize in one statistic all the intervention’s diverse impacts and costs. The cost-benefit analysis for POD will produce cost-effectiveness results on altering the SSDI work rules for the set of volunteers who enroll as study subjects. These volunteers are presumably most likely to benefit from new rules, so the results might not generalize to a broader population, but the findings will still provide SSA with valuable information about the net costs of the demonstration.

There are four targeted outcomes for SSDI beneficiaries under POD: (1) increased employment and earnings above the SGA level; (2) decreased benefits payments; (3) increased total income; and (4) impacts on other related outcomes (for example, health status and quality of life). Four outcomes of interest for system changes include: (1) reduction in overpayments; (2) enhanced program integrity; (3) stronger culture of self-sufficiency; and (4) improved SSDI trust fund balance. To achieve these outcomes, SSA expects POD to make better use of existing resources by improving service coordination among multiple state and local agencies and programs.

Exhibit A.3. Analyses study will use to answer research questions

Research question |

Process analysis |

Participation analysis |

Impact analysis |

Cost-benefit analysis |

What are the impacts of the two POD benefit designs on beneficiaries’ earnings, SSDI benefits, total earnings, and income? |

. |

. |

X |

. |

Is POD attractive to beneficiaries, particularly those whose earnings and benefits the POD $1-for-$2 offset would most likely affect? Do they remain engaged over time? |

. |

X |

. |

. |

How were the POD offset policies implemented, and what operational, systemic, or contextual factors facilitated or posed challenges to administering the offset? |

X |

. |

. |

. |

How successful were POD and SSA in making timely benefit adjustments, and what factors affected timeliness positively or negatively? |

X |

. |

. |

. |

How do the impacts of the POD offset policies vary with beneficiaries’ characteristics? |

. |

X |

X |

. |

What are the costs and benefits of the POD benefit designs relative to current law, and what are the implications for the SSDI trust fund? |

. |

. |

. |

X |

What are the implications of the POD findings for national policy proposals that would include a SSDI benefit offset? |

. |

. |

X |

Cautious interpretation of the evaluation findings based on a study sample of volunteers. In developing the POD evaluation reports, we will develop a cohesive understanding of the types of SSDI beneficiaries who volunteer for the demonstration and how the POD benefit offset affects them. Our integrated approach will enable us to assess not only whether the POD benefit offset policies were effective in increasing income and self-sufficiency for this group, but for whom (which subgroups of beneficiaries) and where (in which implementation settings) the offset policies were more effective. The resulting findings will enable us to develop a broad understanding of potential replicability for a similar sample of volunteers and ways in which the POD benefit offset policies might be improved or better targeted for such a group.

Any broader implications drawn from the impacts found in the evaluation will be undertaken cautiously due to the Public Law 114-74 requirement that the demonstration include volunteers who provide informed consent. The evaluation team’s detailed participation analysis will provide information about the types of SSDI beneficiaries who enrolled in POD and, therefore, to whom the results are applicable. It is likely that these informed volunteers constitute mainly those beneficiaries who believe that assignment to one of the treatment groups will benefit them—that over the course of the demonstration they will work and earn enough to be better off under the POD design than they would be under current law. Volunteers’ expectations about future earnings could be wrong, and their understanding about the POD design could be less than complete, so at least some volunteers will ultimately not benefit from the POD design. Based on theoretical expectations, we anticipate the following beneficiary groups will likely have more incentive to volunteer relative to other beneficiaries: those with relatively higher benefit amounts, more substantial earnings at baseline, and no receipt of SSI or other benefits (such as private disability insurance), as well as those who are near or past their Grace Period. The differences in volunteer rates by characteristics and, specifically, our inability to observe impacts for nonvolunteers, are important for interpreting impact findings, especially in limiting the capacity to directly generalize results beyond the study sample. Hence, the evaluation findings will include a careful discussion of these issues stemming from the volunteer requirement of Public Law 114-74 and what they imply for external validity.

Literature review. The SSI and SSDI programs are designed to provide income support to those with significant disabilities who are unable to work at substantial levels. To qualify for either program, an applicant must demonstrate an inability to engage in SGA due to a medically determinable impairment expected to last at least 12 months or to result in death. SSDI eligibility also depends on having a sufficient number of recent and lifetime quarters of Social Security-covered employment. The SSDI benefit level is based on past earnings; individuals with higher lifetime earnings are eligible for higher SSDI benefits. SSI is a means-tested program, with eligibility subject to strict income and asset limits. The SSI payment is based on the individual’s monthly income and living arrangement. Individuals may qualify for both programs if their incomes (including SSDI benefits) and assets are low enough to meet the SSI income limits.

Most SSDI and SSI beneficiaries qualify for Medicare and Medicaid, respectively. Although there are eligibility and health coverage differences between Medicare and Medicaid, both offset potentially expensive medical care costs and, therefore, can be extremely valuable to people with disabilities. SSI beneficiaries (in most states) are categorically eligible for Medicaid; SSDI beneficiaries become eligible for Medicare after a two-year waiting period following SSDI eligibility.

A major policy challenge is that the caseloads and expenditures of these programs have expanded substantially over the past several decades, with significant recent growth that has put stress on the SSDI and Medicare trust funds. SSI program expenditures, funded through general revenues, have also increased substantially. Federal expenditures to support working-age people with disabilities across all programs (estimated at $357 billion in 2008, including about $170 billion each on income maintenance and health care expenditures) account for a nontrivial and growing share of all federal expenditures. Those expenditures represented 12.0 percent of all federal outlays in fiscal year 2008, up from 11.3 percent just six years earlier (Livermore et al. 2011).

The number of disabled workers who receive SSDI has more than tripled in the past three decades, from 2.9 million in 1980 to 9 million in 2014 (SSA 2015). There is disagreement on the causes of this growth. Some experts, including the chief actuary of SSA, argue, in the words of the latter, that the reasons have been “long anticipated and understood,” and that this growth is almost entirely due to growth in the number of workers and the aging of the baby boom cohort (Goss 2014). Others claim that changes in the SSDI program, including reduction in the stringency of medical eligibility criteria, are the greatest contributors to the growth in SSDI because they have led to increases in award rates for mental disorders and musculoskeletal conditions such as back pain (see, for example Autor and Duggan 2006). Liebman (2015) decomposed the contribution of various factors to SSDI growth and concluded that rising incidence rates (that is, the number of new SSDI awards per the number of disability-insured individuals) accounted for about 50 percent of the growth from 1985 through 2007. He also found that rising incidence rates were predominantly a factor before 1993; population aging has been the predominant factor since then.

In response, policymakers have sought to develop interventions to promote employment and reduce reliance on program benefits, particularly among disability beneficiaries. The demonstrations noted above, including POD, represent efforts to increase employment and reduce reliance on program benefits.

A.1.3. Legal authority

Since 1980, Congress continues to require SSA to conduct demonstration and research projects to test the effectiveness of possible program changes that could encourage people to work and decrease their dependence on disability benefits. In fostering work efforts, SSA intends for this research and the program changes it evaluates to produce Federal program savings and improve program administration. Section 234 of the Social Security Act authorizes SSA to conduct this research and evaluation project. Public Law 114‑74 reauthorizes SSA’s authority to conduct disability insurance demonstration projects, and section 823 of the BBA instructs SSA to carry out the POD. Public Law 114-74 also requires that participation in projects be voluntary and include informed consent. Hence, the subjects in POD must first volunteer and provide informed consent before they can participate in the demonstration. Because SSA only has the authority to conduct this study using a self-selected sample, the results of this study are not generalizable to SSA disability beneficiary population.

Although SSA is required to include volunteers in the demonstration, it is important to note that several agencies have conducted previous demonstrations that included volunteers. For example, most previous SSA demonstration projects have included volunteers, as have projects from the U.S. Department of Labor (such as the Individual Training Accounts Experiment) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (such as the Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstrations). Often, including volunteers is a requirement because the relative effectiveness of a new program is unknown, so there is a potential ethical concern that mandatory enrollment (or mandatory random assignment) might cause harm to participants.

A.2. Description of collection

SSA will have oversight of all POD data collection activities. SSA and its evaluation and implementation contractors will be the primary users of the data for evaluation and implementation activities. SSA will produce a public use data set and supporting documentation for survey data with all personal identifiers removed. Other interested researchers can use this public use file to address issues regarding the health and employment-related activities of SSDI beneficiaries. The following sections describe, in turn: (1) the recruitment materials and baseline survey; (2) the follow-up surveys; (3) qualitative data from POD implementation and operations staff; and (4) semi-structured interviews with treatment group subjects.

A.2.1. Recruitment materials and baseline survey

Recruitment for POD will occur over a 15-month period, from fall 2017 through the end of 2018. POD recruitment will gradually roll out throughout the eight states, one local area (for example, a county) after another. The study will recruit volunteers from a larger population of beneficiaries in each area. Based on lessons learned from past SSA evaluations, notably BOND, the POD evaluation team expects the study will need to send recruitment materials to approximately 300,000 beneficiaries to enroll 15,000 eligible subjects. The evaluation team developed its recruitment approach based on experience with recruitment challenges that arose for the evaluations of BOND and the Ticket to Work program. Their design will mimic a national rollout strategy, similar in concept to the strategy SSA used for Ticket to Work, involving both indirect outreach to beneficiaries via many stakeholder organizations and direct outreach via mailings.

The first part of the recruitment approach is an indirect effort, which includes an information dissemination campaign, a toll-free number, and an informational website. The evaluation team aims for it to establish the legitimacy of POD in each area with stakeholders. This indirect outreach will provide information about the nature of POD and the types of beneficiaries who will find it attractive. It will begin just before the start of recruitment in an area or state, and will target stakeholder organizations serving beneficiaries in various ways. The POD evaluation team will coordinate with the POD implementation team to ensure that key stakeholders do not receive any conflicting messages, as well as to identify synergies in the efforts.

The second part of the recruitment approach is the direct effort, which includes mailings to beneficiaries. The mailings will include a letter and brochure meant to educate potential subjects about POD. The letter will describe the key benefits and drawbacks of the POD offset; a monetary incentive available to those who return the enclosed baseline survey; and the informed consent form. The brochure will complement the letter by including further information about the POD intervention. The POD evaluation team wrote these materials in a way that entices beneficiaries who are likely to benefit from POD to participate in the demonstration by providing succinct but clear and complete information. Shortly after the packet mailing occurs, the evaluation team will attempt to contact a subset of beneficiaries (approximately 25 percent of the total sample) to: (1) verify they received a packet and reviewed the contents; (2) provide further explanations of POD; and (3) offer help completing the forms. Part B of this clearance package includes a discussion of how the POD evaluation team will choose these beneficiaries.

The first three months of the recruiting period will include a pilot phase to refine assumptions about the most effective outreach methods and identify which beneficiaries are most likely to enroll in POD. The last 12 months will include the full rollout. As necessary, the POD evaluation team will modify the recruitment based on the lessons learned during the pilot phase to meet the target of 15,000 subjects for the demonstration. See Part B for additional details.

The process and participation analyses will use information from the pilot phase to develop an understanding of which types of beneficiaries are most likely to volunteer for the demonstration. To achieve this evaluation objective, the evaluation team will develop data on recruitment yields based on responses to the baseline survey (described in the next section), combined with SSA program data about beneficiaries whom the recruitment effort targeted.

Baseline survey and consent form. To participate in POD, beneficiaries must complete the 20-minute baseline survey and return it along with the signed consent form. The baseline survey will collect information for the evaluation that is not readily available in program data; the content of this survey is in Exhibit A.4.

These baseline survey measures will provide descriptive information about the characteristics of the POD subject sample for use in the process and participation analysis. The POD evaluation team will also use this information in the impact analysis to form subgroups or adjust for baseline characteristics when estimating the impacts of POD.

Exhibit A.4. Baseline survey content

Currently working at job for pay |

Date of last job (if not currently working) |

Likelihood of working in next 12 months |

Job training experience |

Receipt of services from a benefit specialist or WIPA provider |

Education—highest achieved |

Overall health status and use of health insurance |

Income—total household |

Race and ethnicity |

Marital status and living arrangement |

The consent form includes information about the random assignment, benefit offset, and research. The consent form highlights the benefits and risks of participation, as required by law, to ensure that participants understand these issues. For simplicity and clarity, the form avoids using technical terms such as substantial gainful activity and extended period of eligibility but nonetheless provide accurate information.

The POD evaluation team anticipates that a portion of beneficiaries who return a consent form and baseline questionnaire will not enroll in the study. The most likely reason for not enrolling is that the beneficiaries decline to consent. However, beneficiaries may also not enroll if: (1) SSA finds they are ineligible after they return the mailing; (2) the baseline questionnaire is incomplete; or (3) the beneficiaries return the forms after recruitment ends. The evaluation team assumes they will need to collect approximately 16,500 baseline surveys and consent forms to obtain the target sample of 15,000 eligible subjects.

A.2.2. Follow-up surveys

The Year 1 and Year 2 follow-up surveys, in conjunction with an analysis of outcomes derived from SSA program data, will capture the experiences of treatment and control group members over a period of two years. Both surveys will collect information about employment‑related activities; training and education; receipt of and satisfaction with POD services; understanding and attitudes toward work incentives; health and functioning; total income; and other contextual variables. A follow-up interval of this length is important to measure the impacts of POD, as the effects of the demonstration on individual behavior and well-being may take time to emerge. The content of the follow up surveys is in Exhibit A.5.

Exhibit A.5. Follow-up survey content

Any jobs for pay in last 12 months |

Details on current, main or last job |

Job search activities and job training experience and education in last 12 months |

Work accommodations, job satisfaction, attitudes toward work and returning to work |

Satisfaction with POD offset, rules and services, reasons for withdrawing from the POD offset |

Understanding/attitudes toward the POD offset, termination of benefits |

Physical and mental health status; hospitalization, current health insurance |

Income—total household, including employment, housing assistance, SNAP, TANF, SSDI, workers’ compensation, disability insurance, other income |

The study will conduct the 30-minute follow-up surveys primarily via web and telephone over 30 months, from fall 2018 to spring 2021. Study staff will conduct the Year 1 survey with a subsample of POD subjects (7,500 or half of the 15,000 POD subjects). This will reduce burden on the full set of subjects, and is feasible because the evaluation team will have some outcome information from program data that they can use in the interim reports. They will conduct the Year 2 survey with the full sample of 15,000 POD subjects.

A.2.3. Qualitative data from POD implementation and operations staff

The POD evaluation team will conduct qualitative data collection in each of the first four years of the evaluation. Key data collection activities will include: (1) in-person site visits, including semi-structured interviews with key POD staff and partners such as VR staff, POD work incentives counselors, and technical assistance providers; direct observation of site operations; and collection of program documentation; and (2) “virtual” site visits consisting of semi-structured telephone interviews with program participants. As part of these visits, the evaluator will interview directors of select VR agencies, or other state partners, implementing POD in the selected states; program staff responsible for arranging and delivering POD services to subjects (such as POD work incentives counselors); and VR state agency staff, and other implementation partners, providing services to subjects. SSA’s evaluation team anticipates that POD sites will vary in geographic location, organization, and staffing arrangements, so the specific number of interviews might vary across sites, although the POD evaluation team expects to interview an average of five program and partner staff during each in-person visit. If key program and partner staff telecommute from geographically dispersed locations, study staff may conduct semi-structured telephone interviews in lieu of in-person site visits. In addition, the POD evaluation team expects to conduct virtual site visits with an average of five key informants per site; the evaluation team will identify these individuals during the in-person visits. Topics for the site visit interviews are in Attachment C, which also includes a description of the evaluation team’s approach for observing program staff interactions with subjects during the in‑person visits to gain more insight into whether service providers are implementing POD as planned and whether providers need additional resources to support implementation. Site visitors will observe activities such as benefits counseling sessions and phone calls between POD work incentives counselors and treatment subjects related to earnings reporting or benefit adjustment issues.

The goals of site visit data collection are to: (1) document the programs, their implementation environments, and the nature of the services they offer to POD subjects; (2) describe VR agency partnerships and other state partnerships developed to implement POD; and (3) assess the extent to which the programs adhere to their intended service delivery models. The study will use this information in the process analysis to provide SSA with a detailed description of the POD programs: how they implement the demonstration; the contexts in which they operate; the program operations and their fidelity to design; and subjects’ perspectives of POD. These detailed descriptions will assist in interpreting program impacts and identifying program features and conditions necessary for effective program replication or improvement. POD evaluation team members will gather information using a range of techniques and data sources to describe the programs and activities completely. They plan to use the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (Damschroder et al. 2009) to guide the collection, analysis, and interpretation of qualitative data. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research is a framework that offers systematic assessment of the multilevel and diverse contexts in intervention implementation and helps in understanding the myriad factors that might influence intervention implementation and effectiveness.

The POD evaluation team will also conduct telephone interviews with SSA payment center staff who are responsible for administering the benefit offset to understand the process staff use to adjust benefit payments under POD better. In addition, the POD evaluation team will conduct telephone interviews with key staff on the POD implementation team to gain insight into their successes and challenges, including recommendations for corrective action to improve service delivery and reasons for withdrawals. SSA is not seeking clearance for these activities because the first involves collecting data from federal employees in their official capacity and the each of the two efforts will involve interviewing nine or fewer people.

A.2.4. Semi-structured interviews with treatment group subjects

In rounds 2 and 3, the POD evaluation team will conduct semi-structured telephone interviews with POD treatment subjects and with individuals who withdraw from the demonstration’s treatment groups. The purpose is to gain an understanding of their direct experiences with POD and gather feedback on ways to improve the implementation of the demonstration. These interviews will inform the process analysis, participant analysis, and the impact study.

The subjects selected for this evaluation component will represent a purposively selected sample of POD treatment subjects. For each round of interviews, the POD evaluation team will complete nine interviews in each site, for total of 72 interviews per round (or 144 in total across the two rounds). They will include subjects from both treatment groups and from key subgroups of interest (for example, subjects who have requested to withdraw; low earning offset users; and high earning offset users). The two rounds of beneficiary interviews will focus on different topics. The first interview will include questions about subjects’ motivations for enrolling in POD; their perspectives on the outreach, recruitment, and enrollment processes; and their understanding of POD offset rules. The second interview will capture subjects’ perspectives of their participation in POD including work incentives counseling, earnings reporting, and benefit adjustment; their attitudes toward employment and work experiences; and POD areas in need of improvement. For subjects who have withdrawn from the demonstration, the interview will provide an opportunity to explore their decision. The interview topics for the beneficiary interviews are in Attachment D.

A.2.5. Implementation Data Collection Instruments

The POD implementation data collection will begin in the fall of 2017 and will continue through the spring 2021. Implementation data collection will follow the flow of study intake and random assignment and will be gradual throughout the eight states included in POD.

During POD’s implementation period, SSA will collect data from SSDI beneficiaries assigned to the two POD treatment groups whose monthly earnings exceed the POD threshold. The implementation team will use two data collection instruments to collect this information: (1) the POD Monthly Earnings and Impairment-Related Work Expenses (IRWE) Reporting Form; and (2) the POD End of Year Reporting (EOYR) Form. These two forms are in Attachments E and F, and we describe them below:

POD Monthly Earnings and Impairment-Related Work Expenses (IRWE) Reporting Form. The implementation team will use this form to collect monthly earnings and IRWE information from POD participants whose monthly earnings exceed the POD threshold. The form collects the respondent’s contact information and provides a table for respondents to list the name(s) of their employer(s) for that month along with their earnings from each employer and any IRWEs that they claimed. The implementation team will also instruct respondents to submit documentation with the form such as paystubs and receipts for IRWEs. To facilitate online submission, the implementation team will replicate this form in an electronic format.

POD End of Year Reporting (EOYR) Form. Beginning in 2018, the implementation team will send POD participants this form every February in advance of the reconciliation process. The implementation team will use the EOYR Form to collect additional earnings or IRWEs that respondents did not report during the prior year. The form provides a table with earnings and IRWE information that the respondent reported during the year, and instructs respondents to submit additional paystubs and IRWE documentation along with the completed form. To facilitate online submission, the implementation team will replicate this form in an electronic format.

Respondents are SSDI beneficiaries, who will provide written consent before agreeing to participate in the study and before we randomly assign them to one of the study treatment groups.

A.3. Use of information technology to collect the information

This evaluation will use information technology to facilitate collection of the survey data in standardized and accurate ways that also accommodate the confidential collection of sensitive data, as well to maintain all demonstration data in a consistent manner. The POD evaluation team will also use information technology to assist with sample tracking and locating efforts for the follow-up surveys. The following subsections describe these uses of information technology in each of the main data collection efforts for the evaluation.

A.3.1. Recruitment materials and baseline survey

The recruitment outreach will provide information to beneficiaries in several alternative formats. The materials include an informational website, a toll-free phone number, and an email address. The POD evaluation team will mail the baseline survey and consent form as paper documents to respondents, and ask them to complete and return them via U.S. mail. If needed, subjects can call the toll-free line to complete the survey through a telephone interview with the assistance of a trained telephone interviewer. When collecting baseline surveys and consent forms, the POD evaluation team will use an automated management information system to assess eligibility. This will reduce burden by preventing staff from enrolling subjects who have not completed a baseline survey and provided written consent, or who might have previously enrolled.

A.3.2. Follow-up surveys

The study will administer follow-up surveys primarily by web and computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) technology. The web and CATI technology help to improve the quality of the survey data collected for the evaluation in several ways. First, web and CATI technology control the flow of the interview, which virtually eliminates any chance for missing data. Second, controlling the flow of the interview also ensures that the skip patterns work properly. Third, computer-assisted interviewing can build in checkpoints that allow the interviewer to confirm responses, thereby minimizing data entry errors. Fourth, automated survey administration can incorporate system checks for allowable ranges for quantity and range value questions, minimizing out-of-range or unallowable values. Finally, web and CATI technology also allow interviewers to record verbatim responses to open-ended questions more easily, supporting efficient survey management.

Although the web and CATI software enhance the quality of the survey data collected by the POD evaluation team and minimizes data entry errors, post-data-collection cleaning – using rigorous protocols – is necessary. First, researchers review frequency distributions to ensure that there are no outlying values, and to make sure that related data items are consistent. Second, analysts review the open-ended or verbatim responses; group like answers together; and assign a numeric value. The most important open-ended responses to require coding are the industry and occupation questions, and those that capture data about the respondent’s knowledge of SSA rules and the demonstration. The automated nature of the survey data collection should reduce the extent of missing data at the item level. Third, in instances where data are missing, the evaluation team will recode the variables in question with standard default codes to indicate missing data. After completing the data cleaning protocols, they will construct appropriate weights required for analysis.

A.3.3. Qualitative data from POD implementation and operations staff

For the process study, the POD the evaluation team will conduct the semi-structured interviews in person and via telephone with implementation and operations staff. The evaluation team will audio-record the discussions to collect the information with consent from staff, ensure that meeting notes are accurate, and securely store and transcribe the audio files.

A.3.4. Semi-structured interviews with treatment group subjects

The POD evaluation team will conduct the semi-structured interviews with subjects via telephone. The evaluation team will audio-record the discussions with consent from staff, and securely store and transcribe the audio files.

A.3.5. Implementation Data Collection Forms

The implementation team will use information technology to facilitate implementation data collection in standardized and accurate ways. Both the POD Monthly Earnings and Impairment‑Related Work Expenses (IRWE) Reporting Form and the POD End of Year Reporting (EOYR) Form) will be replicated in an electronic format. This will provide respondents the option of submitting these forms and supporting documentation on paper or electronically, using an online process. In addition, we will give respondents the option to request email reminders to submit their POD Monthly Earnings and Impairment-Related Work Expenses (IRWE) Reporting Forms.

A.4. Why the information collected will not duplicate existing information

The nature of the information SSA will collect and the manner in which the POD evaluation and implementation teams will collect it preclude duplication. SSA does not use another collection instrument to obtain similar data. The staff interviews, direct observations, program documents, and management information system data will provide information the evaluation and implementation teams cannot obtain through SSA’s program records.

A.4.1. Recruitment materials and baseline survey

The purpose of the baseline survey for the POD evaluation is to obtain current information on the status and well-being of people in the POD study sample. Information about these respondents’ educational attainment, employment status, job skills development, overall health, and use of health insurance is not available through any other source. Further, as described in A.3, the evaluation will use program data in conjunction with survey data to avoid duplication of reporting (for example, disability benefits receipt of suspension). The POD evaluation team will also avoid duplication in this study by using the centrally maintained SMS and RAPTER, which links all the data collected from random assignment with information gathered from program sources.

A.4.2. Follow-up surveys

The purpose of the follow-up surveys for the POD evaluation is to obtain information on the experience and well-being of people in the POD study sample. Information about these respondents’ educational attainment, employment status, job skills development, overall health, and use of health insurance is not available through any other source. The survey data include information on several outcomes that do not appear in the program data, such as subjects’ understanding of the POD offset, which are important for addressing the evaluation’s research questions. Further, as described in Section A.3, the evaluation will use program data in conjunction with survey data to avoid duplication of reporting (for example, disability benefits or earnings).

A.4.3. Qualitative data from POD implementation and operations staff

The interviews will cover staff members’ POD-related operations and experiences; the coordination between POD’s state implementation partners and other agencies or programs; and the fidelity of POD program implementation. Direct observations will focus on activities that the interviews with site program staff do not address specifically. Each site will use the POD implementation team’s MIS to track information on service receipt specific to POD.

A.4.4. Semi-structured interviews with treatment group subjects and Implementation Data Collection Forms

Interviews with treatment subjects will provide information that the study cannot obtain through SSA’s program records or interviews with program staff, such as subjects’ personal experiences with POD. The semi-structured telephone interviews will also provide more in‑depth information than the surveys and will focus on different topic areas, for example, motivation for volunteering for POD, the recruitment and enrollment process, initial contact with demonstration staff, and concerns about the demonstration and needs for improvement. The reporting forms will collect earnings data and impairment-related work expenses for the purposes of the POD study only.

A.5. Minimizing burden on small businesses or other small entities

Some of the service providers that the POD evaluation team interviews for the process analysis may be staff of small entities. The evaluation team’s protocol imposes minimal burden on all organizations involved, and interviewers will keep discussions to one hour or less. The POD evaluation team collects the minimum amount of information required for the intended use, and schedules interviews at times that are convenient to the respondents. In this way, the evaluation team will minimize the effect on small businesses and other small entities.

Some beneficiaries who have institutional representative payees may participate in the demonstration. The small institutions may support the beneficiaries in reviewing the informed consent and baseline survey. If the beneficiaries are interested in POD, they and the representative payee both must sign the document.

A.6. Consequences of not collecting information or collecting it less frequently

A.6.1. Recruitment and baseline survey

If SSA did not conduct the POD evaluation, it would be unable to address important issues regarding SSDI beneficiaries’ success in finding, maintaining, and advancing in employment. The baseline survey is a one-time collection and is necessary to conduct a credible evaluation. The data the POD evaluation team will collect are not available from other sources, and the survey will collect a richer set of information than the evaluation team can gather from program records alone. For example, program records do not offer details on job training experience, likelihood of working in the next year, or job search activities. The study staff will conduct the baseline survey only once, so they cannot conduct it less frequently.

A.6.2. Follow-up surveys

The follow-up surveys will collect information than the POD evaluation team cannot obtain from SSA program records alone. For example, program records may include data on earnings from jobs, but do not offer details such as job training experience; likelihood of working in the next year; or job search activities; as well as types of POD services received, satisfaction with those services, and reasons for withdrawing from POD. The evaluation team expects that collecting these data less frequency, for example by only fielding the second follow-up survey, could reduce the extent or quality of information obtained for the evaluation. This is because a longer recall period is likely to lower the reliability of the information that respondents provide about the period shortly after they enrolled as subjects in the study. Therefore, we cannot collect the data less frequently.

A.6.3. Qualitative data from POD implementation and operations staff

To support the process analysis, the POD evaluation team will conduct two rounds of in‑person site visits with local program administrators, program supervisors, service delivery staff, and partner agencies, and two rounds of virtual visits (telephone interviews). The evaluation team anticipates conducting in-person visits for the first and third rounds of data collection when key informants are working centrally on site at the VR agency or state partners of the POD implementation team. However, in states that rely more on telecommuting staff, they will collect information by telephone in these rounds to reduce the cost of interviewing geographically dispersed respondents. The first visit in early 2018 will focus on start-up activities; outreach efforts; the projects’ outstanding features; and key challenges encountered during early implementation. The second in-person site visit in late 2019 will focus on POD infrastructure; staff use of the MIS; benefits counseling; monthly reporting of earnings and IRWEs; processing of the offset; and successes and challenges. The virtual site visits, conducted in the interim years, will enable the evaluation team to continue to document POD recruitment and enrollment; progress developing the POD infrastructure; adjustments made to correct issues identified; and in round 4, exiting POD and lessons learned in later rounds. All site visits are necessary to develop an understanding of the intervention and the steps taken to implement project services as well as to assess fidelity of the demonstration design.

Conducting fewer in-person and virtual visits would limit the POD evaluation team’s ability to follow up on challenges observed early in the implementation period; this, in turn, could reduce their capacity to help implementation staff resolve or improve activities between visits. Fewer rounds of site visits would not allow SSA to assess how the projects evolve over time to address significant challenges and leverage successes. Interviewing fewer staff on each visit or interviewing staff less frequently would not allow SSA to capture the full range of experiences to document all features of the service environment. Therefore, the evaluation team cannot collect the range of information needed for this evaluation less frequently, or with fewer respondents.

A.6.4. Semi-structured interviews with treatment group subjects

The POD evaluation team will also conduct two rounds of semi-structured telephone interviews with program subjects. These interviews are necessary to help SSA assess whether there is interest in the program; whether subjects have a favorable impression of the demonstration; how this translates into take-up rates; and how participation in POD affected education or training decisions and subjects’ quality of life.

The first interview will provide an early assessment of subjects’ perspectives so the evaluation can provide early feedback to states, the implementation contractor, and the VR agencies and the implementation team’s other state partners serving POD subjects. The second interview will provide more information about satisfaction with services received, employment, and the offset. The two rounds of beneficiary interviews will focus on different topics. During the first interview, the protocol will include questions on the subjects’ motivation for volunteering for POD; employment goals; the recruitment and enrollment process; initial contact with demonstration staff; services received; and any concerns about the demonstration. The second round of interviews will capture subjects’ perspectives of the services received; their participation in POD; work experience; attitudes toward employment; and areas in need of improvement. For subjects who have withdrawn from the demonstration, the interview will provide an opportunity to explore their decision. Because not all subjects will have a chance to use the benefit offset before the first round of interviews, particularly those that enroll in late 2018, a second round of interviews is necessary to assess the offset’s effect on employment for these later enrollees.

A.6.5. Implementation Data Collection Forms

The implementation data for POD, which we will collect on the earnings collection forms, is essential for SSA to operate POD and are not available from other sources. Collecting the data less frequently would increase the risk of SSA calculating the participants’ DI benefit incorrectly, which could in turn cause participants to experience overpayments and underpayments. Because we need to update the data monthly for the purposes of evaluating the POD data, we cannot collect this information less frequently.

A.7. Special circumstances

The proposed data collection activities are consistent with the guidelines set forth in 5 CFR 1320.5 (Controlling Paperwork Burden on the Public, General Information Collection Guidelines). There are no circumstances that require deviation from these guidelines.

A.8. Solicitation of public comment and other consultation with the public

A.8.1. Federal Register

The 60-day advance Federal Register Notice published on April 18, 2017, at 82 FR 18335, and we received no public comments. The 30-day FRN published on July 27, 2017, at 82 FR 35022. If we receive any comments in response to this Notice, we will forward them to OMB.

A.8.2. Consultation with the public

SSA consulted with an interdisciplinary group of economists, disability policy researchers, survey researchers, and information systems professionals on the staff of Mathematica Policy Research and its subcontractor, Insight Policy Research, contributed to the design of the information collection effort for this evaluation. These people include:

David Wittenburg, Ph.D., Mathematica

Kenneth Fortson, Ph.D., Mathematica

Noelle Denny-Brown, Mathematica

Karen CyBulski, Mathematica

David Stapleton, Ph.D., Mathematica

Heinrich Hock, Ph.D., Mathematica

Debra Wright, Ph.D., Insight

SSA also consulted with the team from Abt Associates, as the prime contractor for the implementation of POD. In addition, Abt’s subcontractor, VCU, assisted with the design for POD’s implementation. SSA collaborated on the design of POD’s implementation with the Abt study team to ensure the technical soundness and usefulness of the data collection instruments in carrying out the aims of POD’s implementation. These people include:

Sarah Gibson, Abt

Eric Friedman, Abt

Brian Sokol, Abt

Susan O’Mara, VCU

A.9. Payments or gifts to respondents

SSA believes that some compensation is important to engender a positive attitude about the study and reduce attrition in follow-up interviews. Research shows that incentives increase response rates without compromising data quality (Singer and Kulka 2000), and help increase response rates among people with relatively low educational levels (Berlin et al. 1992), among low-income and non-white populations (James and Bolstein 1990), and among unemployed workers (Jäckle and Lynn 2007). There is also evidence that incentives bolster participation among those with lower interest in the survey topic (Jäckle and Lynn 2007; Kay 2001; Schwartz, Goble, and English 2006), resulting in data that are more complete.

A.9.1. Recruitment and baseline survey

Incentive payments are a powerful tool for maintaining low attrition rates in longitudinal studies, especially for members of the control group who are not receiving any (other) program benefits or services. Using incentive payments for the POD baseline survey can increase the attractiveness to participation in the demonstration. This may help the POD evaluation team efficiently recruit a sufficient sample size necessary to meet SSA’s objectives of the evaluation.

The POD evaluation team will pay survey respondents a modest sum to encourage response; facilitate cooperation; and demonstrate appreciation to subjects for their time and effort. Each POD subject who returns a completed baseline survey and consent form, regardless of whether they give consent for random assignment and further participation in the study, will receive a $25 incentive. As discussed in Part B, one experiment in the recruitment pilot phase could be to alter the incentive amount and assess how doing so affects recruitment yields.

A.9.2. Follow-up surveys

The POD evaluation team will pay follow-up survey respondents a differential incentive based on the mode of response. POD subjects who complete a follow-up survey by web will receive an incentive of $30 for the 12-month survey and $35 for the 24-month survey. Subjects who complete a follow-up survey by telephone will receive an incentive of $20 for the 12-month and $25 for the 24-month survey. If subjects do not respond to either follow-up survey despite multiple attempts, the study will mail them a prepaid $5 incentive and a short questionnaire that contains only critical items.

A.9.3. Qualitative data from POD implementation and operations staff

The POD evaluation team will not offer program administrators, POD service provider staff, or their partners remuneration for completing the site visit interviews.

A.9.4. Semi-structured interviews with treatment group subject

The POD evaluation team will provide a $25 gift card to respondents who participate in the semi-structured telephone interviews, to encourage participation and thank them for taking part. It is important to offer a reasonably high incentive to these subjects to ensure timely recruitment and completion of the interviews within the desired time frame.

A.9.5. Implementation Data Collection Forms

SSA will not provide payments or gifts to POD participants for activities related to the implementation of POD.

A.10. Assurances of confidentiality

The subjects of this information collection and the nature of the information the team will collect require strict confidentiality procedures. SSA will protect the information the POD evaluation team collects in accordance with 42 U.S.C. 1306, 20 CFR 401 and 402, 5 U.S.C. 552 (Freedom of Information Act), 5 U.S.C. 552a (Privacy Act of 1974), and OMB Circular No. A‑130. Descriptions of the detailed plans for informed consent and data security procedures are in subsequent sections.

A.10.1. Informed consent

All potential POD subjects should be able to make a genuinely informed decision about participation in the demonstration. Vigorous outreach with a clear message and strong supporting materials will help to ensure that people applying to the demonstration understand the opportunities available and are likely to take advantage of the demonstration’s benefits. The outreach materials will clearly explain the risks to subjects by highlighting situations when SSDI beneficiaries’ benefits would be higher or lower under the POD offset rules; the outreach materials will also include a detailed comparison of the current SSDI rules and the new POD rules if the evaluation assigns subjects to one of the treatment groups.

The POD evaluation team will obtain the informed consent of each sample member through a signed consent form (see Appendix A), which describes the demonstration; the process of random assignment; and the evaluation’s information requirements. As shown in Attachment A of this submission, this form also indicates to applicants that participation is voluntary and that agreeing to participate means that they give permission for researchers to access information about them, such as their SSDI benefit status, from other sources.

In addition, the baseline survey contains two questions to confirm the beneficiaries’ understanding of POD. The study will use the questions to screen out beneficiaries who provide answers that demonstrate they do not understand the voluntary nature and general purpose of POD.

When the POD evaluation team recruits program subjects for the qualitative, semi-structured interviews via phone, they will assure subjects that the evaluation will keep their information confidential, unless required by law, and not use it in any way that would affect their program eligibility or payments, if applicable. At the time of the interview, the evaluation team will again advise subjects of the purpose of the interview. They will also provide the subjects with a toll‑free telephone number to call if they have questions about the study.

A.10.2. Data confidentiality protections

The POD evaluation team clearly states the assurances and limits of confidentiality in all advance materials it sends to recruit potential subjects, and restates them at the beginning of each interview. For the baseline surveys, the advance letter to SSDI beneficiaries will make clear the assurances and limits of confidentiality. The Paperwork Reduction and Privacy Act statements will appear on the advance letter and on the baseline questionnaire (Attachment A).

The POD enrollment database, RAPTER, will contain the contact information the evaluator will use to invite subjects to complete the interviews. The evaluation team will not disclose the identity of the group subjects to anyone outside of the POD evaluation and implementation teams. Public documents from the evaluation will summarize information the subjects provide, but will not attribute it to specific people.

The implementation team will use strict procedures for maintaining the privacy, security, and integrity of data. The Paperwork Reduction and Privacy Act statements will appear on the POD Monthly Earnings and IRWE Reporting Form and the POD EOYR Form. In addition, the informed consent process conducted by the evaluation team during the POD random assignment process will assure participants that participation in POD is voluntary; that all information will remain confidential; and that we will only report respondents’ information in aggregate form.

A.10.3. Data storage and handling of survey data

SSA and its POD evaluation team contractors have procedures in place to ensure we appropriately safeguard data from unauthorized use and disclosure, including the use of passwords and encrypted identifiers. It uses several mechanisms to secure data, including obtaining suitability determinations for designated staff; training staff to recognize and handle sensitive data; protecting computer systems from access by staff without favorable suitability determinations; limiting the use of personally identifiable information in data; limiting access to secure data on a need-to-know basis and to staff with favorable suitability determinations; and creating data extract files that exclude identifying information.