Comparison of Unweighted Distrubutions by Sexual Orientation

ATT_P_SplitStudyPrelimResults.docx

National Survey of Family Growth

Comparison of Unweighted Distrubutions by Sexual Orientation

OMB: 0920-0314

NSFG OMB Attachment P OMB No. 0920-0314

NSFG OMB Attachment P

Comparison of Unweighted Distributions by Sexual Orientation in NSFG ACASI,

based on NSFG and NHIS Question Wording

Note: This attachment was provided in our Change Request, approved in August 2017

Background

Since 2002, the NSFG has included a question on sexual orientation, asked for all male and female respondents aged 15-44 (and 15-49 since 2015) in the self-administered portion of the survey (Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview, or ACASI). Detailed reports on sexual behavior, sexual orientation and sexual attraction, based on NSFG data from 2002, 2006-2008, 2006-2010, and 2011-2013 have been published (Mosher et al, 2005; Chandra et al., 2011, 2012; Copen et al, 2016). Other reports published by NCHS have examined sexual orientation as one of several correlates of other sexual and reproductive health related behaviors such as HIV testing, self-report of STI in lifetime and other STI/HIV risk behaviors (Copen et al, 2015; Mosher et al, 2005; Chandra et al, 2012).

Since sexual orientation was first included in the NSFG ACASI in 2002, several changes have been made to the NSFG question to minimize response error. The 2002 question was patterned directly on the 1992 National Health and Social Life Survey, conducted by University of Chicago, and basic statistics were published (Mosher et al, 2005). For reasons fully described in the technical notes of a prior NCHS report (Chandra et al, 2011), in 2006, more commonly known terms for sexual orientation were added to the response categories used in the 2002 NSFG. Instead of ‘‘heterosexual,’’ the response was changed to ‘‘heterosexual or straight’’ for both men and women. Similarly, instead of ‘‘homosexual,’’ men were offered ‘‘homosexual or gay,’’ and women were offered ‘‘homosexual, gay, or lesbian.” Furthermore, respondents were able to select the category of “something else” to describe their sexual orientation in both 2002 and 2006-2008. Detailed analysis of the “something else” category showed that the addition of the more commonly known terms to describe sexual orientation significantly reduced the percentage of respondents reporting “something else” as well as the percentages who “did not report” sexual orientation (e.g., “don’t know” or “refused” ) between 2002 and 2006-2008. Hence, the “something else” category and a follow-up verbatim question, “When you say “something else,” what do you mean?” were deleted from the survey in July 2008.

Along with these improvements in the wording of the NSFG’s sexual orientation question, there have been continued efforts to harmonize the sexual orientation question across NCHS surveys. The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) first included a sexual orientation question in 2013, and after several years of cognitive and operational testing (Dahlhamer, 2014), arrived at a question that was recommended as the NCHS-wide standard.

The NSFG and NHIS questions are shown below:

NSFG question:

Do you think of yourself as ...

Heterosexual

or straight

Homosexual,

gay, or lesbian

Bisexual

NHIS question:

Which of the following best represents how you think of yourself?

Lesbian or gay

Straight, that is, not lesbian or gay

Bisexual

Something else

NSFG was asked to adopt the NHIS question beginning in 2015, but given the NSFG’s longer history of asking about sexual orientation in the ACASI mode, we were approved, as part of our 2015-2018 renewal package in 2015, to conduct a 50-50 randomized study to compare the distributions by sexual orientation that are obtained using the two question approaches. Also, this study permitted an assessment of the two questions in a similar placement in the questionnaire, that is, in the same position in ACASI after all sexual behavior items had been asked, which would potentially “equalize” any contextual effects seen when comparing NSFG and NHIS data directly. Beginning with fieldwork in September 2015, all NSFG ACASI respondents were randomized in a 50-50 split to be asked either the NHIS or the NSFG sexual orientation question.

Results of the 50-50 Randomized Study of the NSFG & NHIS Questions

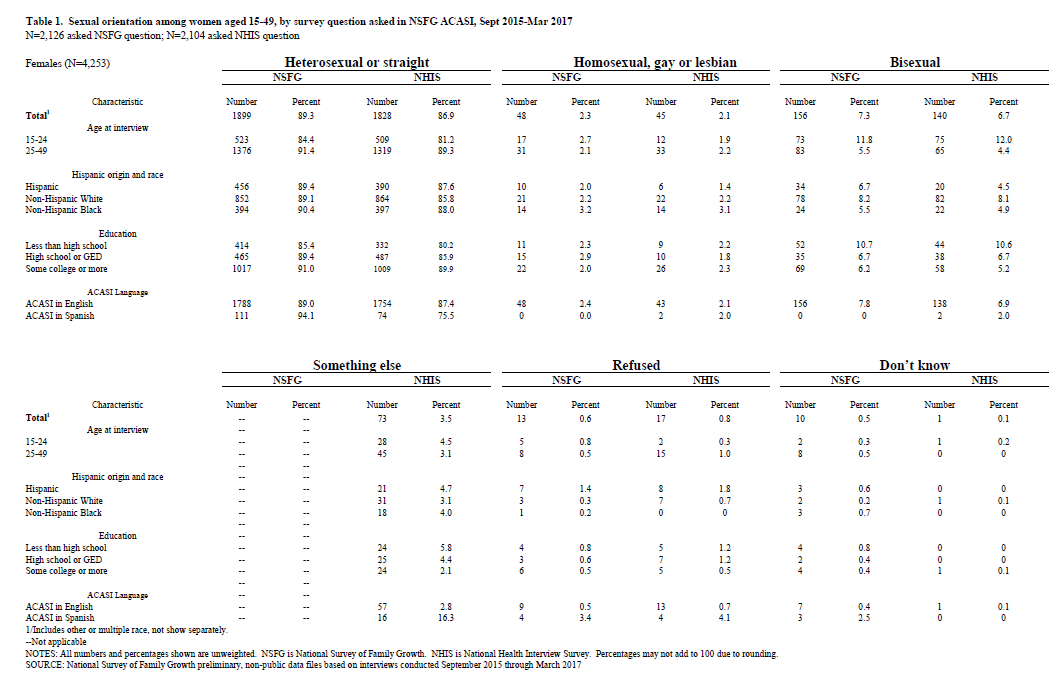

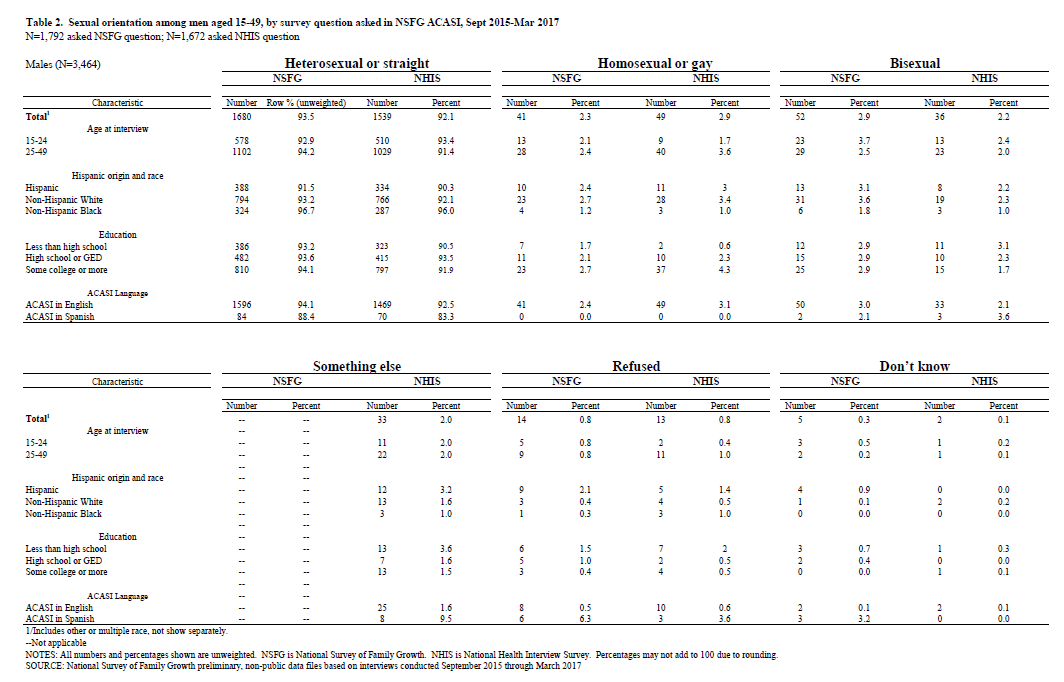

Tables 1 and 2 show the unweighted sample numbers and percentage distributions for the NSFG and NHIS sexual orientation questions among 4,253 females and 3,474 males respondents aged 15-49 who were interviewed between September 2015 through March 2017. (Appropriate sample weights for the full 2-year data files planned for public release will not be available until early 2018, so only unweighted tabulations can be examined at this time.) The overall distribution by sexual orientation was similar for the NSFG and NHIS questions. Among females 15-49, 89.3% who received the NSFG question identified as “heterosexual or straight” compared with 86.9% who received the NHIS question, 2.3% and 2.1% identified as “homosexual/gay/lesbian,” 7.3% and 6.7% identified as “bisexual,” 0.6% and 0.8% refused and 0.5% and 0.1% said “don’t know.” For males 15-49, 93.8% who received the NSFG question identified as “heterosexual or straight” compared with 92.1% who received the NHIS question, 2.3% and 2.9% identified as “homosexual/gay,” 2.9% and 2.1% identified as “bisexual,” 0.8% (for both) refused and 0.3% and 0.1% said “don’t know.”

Responses to the NSFG and NHIS sexual orientation questions were also generally similar by the subgroups shown for age, Hispanic origin and race, education, and ACASI language. Additionally, 3.5% of females and 2.0% of male respondents aged 15-49 identified as “something else” (NHIS question only). One primary difference between these questions , albeit with these unweighted data, was among female and male respondents aged 15-49 who completed ACASI in Spanish; these respondents appeared more likely to identify as “something else,” an option only available in the NHIS question, than respondents who completed ACASI in English. For female respondents completing ACASI in Spanish, 16.3% identified as “something else,” compared with 2.8% of females completing ACASI in English. For male respondents completing ACASI in Spanish, 9.5% identified as “something else,” compared with 1.6% of males completing ACASI in English. This difference in reporting of “something else” by ACASI language for the NHIS version of the sexual orientation question reduced the percentage identifying as “heterosexual/straight,” compared with the percentages seen with the NSFG question where no “something else” option was offered. Among women answering the NHIS question in Spanish, 75.5% identified as “straight” compared with 94.1% of women answering the NSFG question in Spanish. No such difference was seen among women answering the ACASI questions in English. Although the difference was smaller for males, a similar pattern was seen: 83.3% of males who answered the NHIS question in Spanish identified as “straight,” compared with 88.4% of females who answered the NSFG question in Spanish. The unweighted data also suggest that females and males who completed ACASI in Spanish were also more likely to answer either version of the sexual orientation question with “don’t know” or “refusal” compared with those who answered in English.

While we cannot know for sure what respondents answering “something else” on the NHIS question may have meant, there is some possible insight from previous data collected for the NSFG and NHIS. Before the follow-up questions for those reporting “something else” were dropped in both the NSFG (in 2008) and NHIS (in 2015) surveys, analyses of these verbatim responses indicated that there were no significant differences in any of the response categories of sexual orientation once responses that could be backcoded into an existing category were re-classified (Chandra et al, 2011; Dahlhamer et al, 2014). It is difficult to conclude whether the addition of the “something else” category on the NHIS question significantly changes the percent distribution of the other sexual orientation categories, particularly for those who answered the ACASI in Spanish, until more data from this 50-50 study are available and can be analyzed with the appropriate sample weights and variance estimation variables to account for the complex survey design.

Recommendation

Based on these unweighted findings from the 50-50 study of the 2 question approaches, we would like to continue the study to compare these questions until the end of fieldwork under the current contract (currently scheduled to end June 2019, with possible extension to September 2019). Additional cases and the availability of the sample weights (prepared by ICPSR before release of the 2015-2017 file in Fall 2018) will allow us to compare these questions in a more statistically valid manner, accounting for the complex survey design and assessing the statistical significance of the differences noted with unweighted data.

References

Chandra A, Billioux VG, Copen CE, Sionean C. HIV Risk-Related Behaviors in the United States Household Population Aged 15–44: Data from the National Survey of Family Growth, 2002 and 2006–2010. National health statistics reports; no 46. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2012.

Chandra A, Copen CE, Mosher, WD. Sexual Behavior, Sexual Attraction, and Sexual Identity in the United States: Data from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. In Amanda Baumle (Ed.) International Handbook on the Demography of Sexuality. New York, NY. Springer Publishing Company. 2012.

Chandra A, Mosher WD, Copen C, Sionean C. Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States: Data from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. National health statistics reports; no 36. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2011.

Copen CE, Chandra A, Febo-Vazquez I. Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual orientation among adults aged 18–44 in the United States: Data from the 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth. National health statistics reports; no 88. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2016.

Copen CE, Chandra A, Febo-Vazquez I. HIV testing in the past year among the U.S.household population aged 15–44: 2011–2013. NCHS data brief, no 202. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2015.

Dahlhamer JM, Galinsky AM, Joestl SS, Ward BW. Sexual orientation in the 2013 National Health Interview Survey: A quality assessment. Vital Health Stat 2(169). 2014.

Mosher WD, Chandra A, Jones J. Sexual behavior and selected health measures: Men and women 15–44 years of age, United States, 2002 . Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 362. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2005.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Copen, Casey E. (CDC/OPHSS/NCHS) |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-21 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy