National Household Education Survey 2019 (NHES:2019)

National Household Education Survey 2019 (NHES:2019)

Appendix 4 Study of NHES 2019 Nonresponding Households

National Household Education Survey 2019 (NHES:2019)

OMB: 1850-0768

National Household Education Survey 2019 (NHES:2019)

Full-scale Data Collection

OMB# 1850-0768 v.14

Appendix 4 – In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households

May 2018

Contents

Description and Justification 2

1.2 The utility of conducting follow-up studies 3

1.3 The challenges associated with using address-based sampling (ABS) frames 3

1.4 The benefits of collecting interviewer observations 3

2.1 Structured interview methodology 4

2.2 Qualitative interview methodology 6

3. Looking ahead: making use of the study findings 10

B1.1 Address/neighborhood observation instrument 15

B1.2.3 General survey attitudes and experiences 17

B1.2.4 Experience as an NHES sample member 18

B2.1.3 Qualitative interview items 21

B2.1.4 Feedback on NHES materials 22

B2.1.5 Mail interaction discussion 23

Description and Justification

Given continued declines in response rates to both the National Household Education Surveys (NHES) and to household surveys more broadly – and the growing challenges associated with conducting cost-efficient, high-quality, representative data collections, NCES will conduct the In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households during the NHES:2019 administration. This study will primarily address the following research questions:

What are the barriers to response among screener nonrespondents to NHES? For example, do screener nonrespondents remember receiving the survey mailings, and, if so, do they open them? What stops some households from receiving or opening the mailings?

What are the characteristics of nonresponding households? Is there information about nonresponding households that could be used to tailor contact protocols in future collections?

Is the information available on the address-based sampling frame for nonresponding households accurate to ensure variables used for tailoring materials or predicting data collection protocols are reliable?

Are there variables related to household survey nonresponse that have not been previously observed or measured?

Two separate interview operations will be conducted to address these research questions: (a) approximately 230 10-minute interviews using a structured interview protocol and neighborhood observations (“structured interviews”) and (b) approximately 80 90-minute interviews using a semi-structured, qualitative interview protocol and home observations (“qualitative interviews”). Due to the differences in interview protocols, data from these two sets of interviews will be analyzed separately. This document discusses the importance of conducting this study and provides an overview of its methods.

1. Background

Survey nonresponse has been increasing for several decades (Brick and Williams 2013; Czajka and Beyler 2016). NHES has not escaped this trend; between the first mail-based NHES administration in 2012 and the most recent one in 2016, the screener response rate has dropped from 74 percent to 66 percent (McPhee et al. 2015; McPhee et al. 2018). In addition, NHES nonrespondents tend to be younger, less educated, and have lower incomes than respondents; they are also less likely to be White or to be married than are respondents.

Given the global nature of this phenomenon, researchers have devoted considerable attention to understanding the factors that contribute to survey nonresponse. Proposed individual-level explanations for nonresponse include privacy concerns, anti-government sentiment, busyness and fatigue, concerns about response burden, lack of interest in the topic, and low levels of civic engagement or community integration (Abraham et al. 2006; Amaya and Harring 2017; ASA Task Force on Improving the Climate for Surveys 2017; Groves et al. 1992; Groves et al. 2004; Singer 2016). Investigators also have suggested that societal-level changes, such as the increasing number of survey and solicitation requests, declining confidence in public institutions, and growing concerns about security and identity theft are contributing to declining response rates (ASA Task Force on Improving the Climate for Surveys 2017; Czajka and Beyler 2016; Presser and McCulloch 2011).

However, much remains unknown about sample members’ reasons for nonresponse and the best way to counteract those concerns. Recent task force reports focused on survey nonresponse argue there is a need for more research about the current survey climate and the various factors that could improve survey participation (AAPOR Task Force on Survey Refusals 2014; ASA Task Force on Improving the Climate for Surveys 2017). Due to the emphasis on telephone surveys in the latter decades of the 1900s, little research has been carried out since the 1970s about the response decision process associated with mail surveys like NHES (Singer 2016). Questions remain about whether research on nonresponse within mail collections from previous decades holds up in today’s survey environment.

Studies that have followed up with survey sample members after the survey request has been made have proven to be a useful tool for understanding the reasons for response (or lack thereof). In-depth follow-up interviews with respondents to an earlier survey found that materials that clearly communicated the topic and benefits of the study were particularly important for gaining response (Harcomb et al. 2011). In another study, semi-structured follow-up interviews with sample members identified altruism, perceived personal benefit, understanding the study, and being committed to its success as primary reasons for responding (Nakash et al. 2008). A focus group of immigrant and ethnic minority nonrespondents to a Danish national health survey discovered that linguistic and educational limitations, alienation resulting from sensitive questions and cultural assumptions, and concerns about anonymity were the primary cause of nonresponse among that group (Ahlmark et al. 2015).

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Response Analysis Survey used qualitative telephone interviews to examine nonresponse (refusals) to the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) (O’Neill and Sincavage 2004). The study found that the advance materials were ineffective at communicating the differences between the Current Population Survey, which served as the sampling frame for the ATUS, and the ATUS. It concluded that how respondents perceive the survey sponsor is an important factor in whether to participate and that the use of incentives should be explored to encourage participation.

The American Community Survey (ACS) conducts an in-person computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) follow-up for a subsample of nonrespondents. Special emphasis is placed on collecting data from many languages (e.g., providing language assistance guides to the interviewers in Chinese and Korean, special training). Language availability and the mandatory nature of the survey keep the response rates high (United States Census Bureau 2014). CAPI interviewers achieve about a 95.5% interview rate. Cases that showed initial resistance or had at least one coded refusal had interview rates of 94.5% and 26.8% respectively (Zelnack et al. 2013). The ACS also uses the Contact History Instrument (CHI) to monitor field performance and collect paradata during in-person interviews. The purpose of the interview is to collect data from nonrespondents.

Despite the research cited here, there are relatively few studies that attempt to explore the reasons for nonresponse in American household surveys at the scale or depth planned for the In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households, making this an important and unique contribution to the survey literature and a potential resource for researchers facing the same challenges in other national, federal government household surveys.

The NHES sample is comprised of addresses drawn from an ABS frame. The quality of the information about these addresses on the frame is another factor that could contribute to nonresponse. For example, vacancy or seasonal status indicators available on the frame could be inaccurate and lead to addresses being sampled where there is no one available to respond (AAPOR Task Force on Address-Based Sampling 2016). In addition, if the information available about the individuals living at sampled addresses (such as whether they prefer to speak Spanish) is inaccurate, this creates challenges for designing survey protocols that are targeted at sampled addresses’ response preferences (such as whether to send Spanish-language materials). The NHES frame is not immune to this problem; analysis of NHES:2016 data shows that only about 55% of the screener respondent households flagged on the commercial vendor frame as having children ended up reporting a child on the screener. Assessing the quality of additional sampling frame variables through interview questions and observations will help to assess the extent to which inaccurate frame data may be hindering efforts to gain response to NHES and making recruitment efforts inefficient.

Interviewer observations are a low-burden tool for learning about the context in which sample members receive the survey request and for verifying ABS frame data. Little and Vartivarian (2005) suggest that interviewer observations of variables related to the likelihood to participate in a survey and to the survey’s key estimates can be used to adjust for nonresponse bias. Several large-scale, in-person surveys collect observations using tools such as the Contact History Instrument or Neighborhood Observation Instrument (NOI). Since 2013, National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) interviewers have used the NOI to observe neighborhood characteristics, such as the condition of units or the presence of barriers to access, and to make inferences about sample member characteristics of interest, such as income, employment, and the presence of children (United States Census Bureau 2017). NHIS researchers have found that some, but not all, NOI measures are positively associated with refusal to participate (Walsh et al. 2013). The National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) also collects interviewer observations about the neighborhood, housing unit, and sampled persons (User’s Guide for Paradata File n.d.). NSFG researchers again find that some, but not all, of the recorded observations are associated with lower propensity to respond to the in-person interview request (Lepkowski et al. 2013). These findings highlight the potential benefit of collecting observations, as well as the need for further research into which neighborhood and address characteristics are related to responsiveness to a mailed survey instead of an in-person survey.

2. The proposed study

The proposed In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households will use structured and qualitative in-person interviews, as well as address and household observations to assess whether the existing theories surrounding household survey nonresponse are applicable to NHES. The study is designed to provide additional actionable information about how to combat the growing nonresponse problem in NHES and other federal government household surveys that use mail to contact sample members. It is expected that the results of this study will be used to improve the design of NHES, with the goal of increasing the response rate and the representativeness of the respondents. Potential changes could include modifications to the nonresponse follow-up protocol, the type of incentives offered, and the presentation of contact materials.

The primary goal of the structured interviews is to understand who lives in nonrespondent households and the household members’ primary reasons for nonresponse.

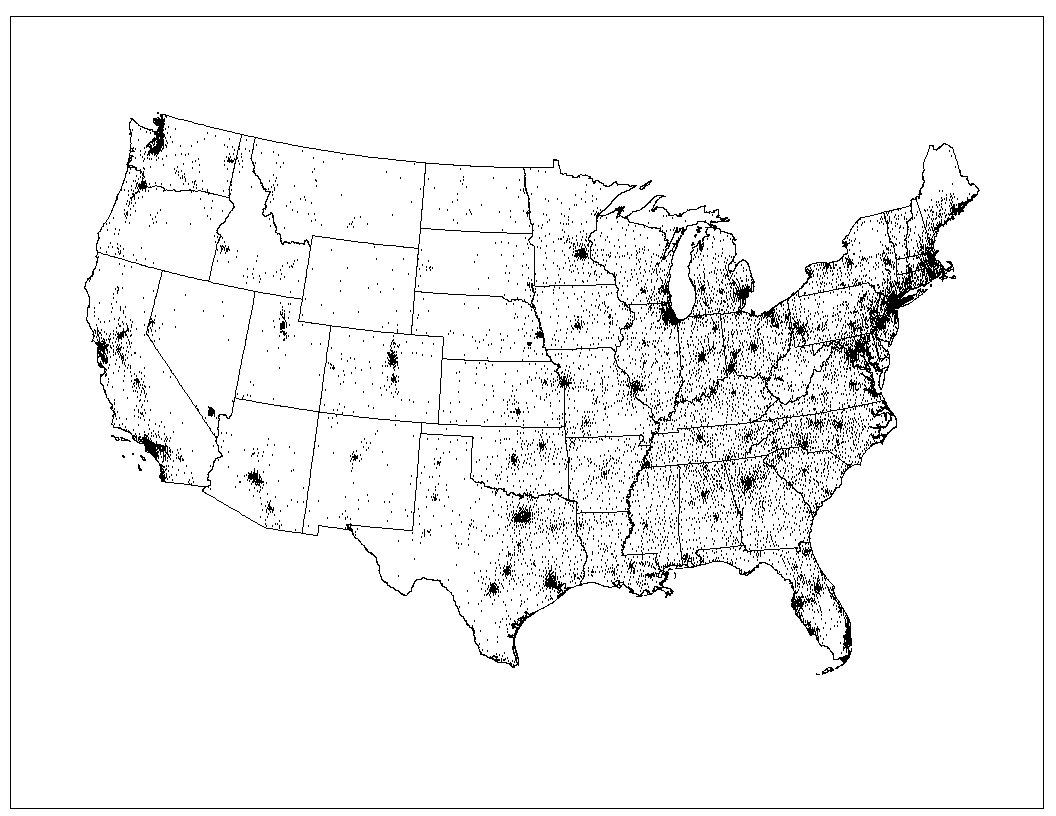

Approximately 230 structured interviews will be conducted with NHES screener nonrespondents. Screener nonrespondents, rather than topical nonrespondents, are the focus of the study because of the impact that screener nonresponse has on both the screener response rate and each NHES survey’s overall response rate and because NHES screener response rates are lower than topical response rates.1 Larger numbers of screener nonrespondents are anticipated to be clustered in metropolitan areas than in more rural locales. Exhibit 1 plots the location of NHES:2016 screener nonrespondents. As expected, screener nonrespondents are widely dispersed, but there is some clustering around large cities.

About 350 screener nonrespondents will be sampled to yield these 230 completed interviews. Sampled cases will be clustered around 2 to 4 U.S. cities and will be located within 70 miles of the center of those cities. To evaluate the representativeness of the sample drawn from the cities under consideration (Chicago, IL; Washington, DC; Atlanta, GA; Austin, TX; and San Mateo, CA), we have conducted a preliminary analysis using NHES:2016 data to identify potential biases in cases reached under this design compared to cases that are located outside of these five city areas. Focusing on statistically significant biases of five percentage points or more, this analysis suggests that the following groups would be overrepresented in this study sample:

Addresses in high percent Hispanic strata (and addresses that are in strata that are neither high percent Black nor high percent Hispanic would be underrepresented);

Addresses where the head of the household is Hispanic (and those where the head of household is White would be underrepresented);

Addresses that received bilingual mailings (and those that did not would be underrepresented);

Addresses in block groups that are 100 percent urban (and those that are located in block groups that are 50 percent or less urban would be underrepresented); and

Addresses with Census low response scores (LRS) in the fifth (lowest propensity) quintile (and those in the second highest quintile would be underrepresented).

Exhibit 1. Location of NHES:2016 Screener Nonrespondents

Though cases located near cities overrepresent certain subgroups of nonrespondents (such as those that are Hispanic or urban dwellers), these are also the groups that tend to be less likely to respond to NHES. In NHES:2016, household in tracts with 40% of more Hispanic persons, high rise apartments, and renters had lower weighted screener response rates, 55.9%, 58.9%, and 56.6% respectively (see Attachment A in this document for screener response rates by additional subgroups) (McPhee et al. 2018). This study is an opportunity to learn more about the specific response barriers faced by these specific types of sample members. For example, are sample members that need bilingual mailings getting them, and are sample members living in multi-unit or high-rise buildings receiving their mailings? While the resulting sample will not be nationally representative, it will be large enough to provide rich data about these important subgroups of nonrespondents. Analyses of the resulting data are expected to illuminate some of the factors associated with nonresponse and inform revisions to the content and design of recruitment materials to be used in NHES:2022.

2.1.1 Recruitment

Sampled cases will be sent an advance letter that includes $2 or $5 cash2, invites them to participate in the in-person study, and indicates that someone will be visiting their home to ask them to complete an interview. The advance letter does not ask for a response or action from the household member. Its purpose is to inform the household that an interviewer will visit their house. All sampled cases will be offered an additional $25 cash incentive for completing the interview. This incentive is designed to demonstrate to participants that their time and participation is valued and takes into account that the sample is comprised of households that have already shown reluctance to participate in the survey. Recruitment materials will be branded as coming from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). The participant will receive a consent form to read and sign before the interview starts, and will be able to keep a copy of the form for their records. The details of obtaining consent and the consent forms will be submitted for OMB’s review with a 30-day public comment period in fall 2018.

2.1.2 Address observations

When field interviewers first reach a sampled address, they will complete a brief observation of the neighborhood and address as unobtrusively as possible. The main goal of this observation task is to better understand the characteristics of nonresponding addresses (e.g., whether they appear to be occupied or whether there are objects present that suggest children live there such as children’s outdoor toys). The observations also will assess quality of the United States Postal Service (USPS) return service (for example, are there addresses that actually appear to be vacant or nonexistent? Is it possible to locate the addresses that had at least one mailing returned as undeliverable, and, if so, what are their characteristics?).

2.1.3 Structured interview protocol

Upon completion of the address observation, the field interviewer will ring the bell or knock on the door of the home. If no one answers the door, the interviewer will leave a “Sorry I Missed You” card at the household. The card will indicate that he or she stopped by and will return at a later day and time. It also will contain a phone number the sample member can call to learn more about the study and/or schedule an interview. If someone answers the door, the field interviewer will introduce him- or herself, show their identification badge and forms to indicate that they are part of the study, mention the advance letter, and attempt to speak with the adult living at this address who usually opens the mail.3 If that person is not available, the interviewer will attempt to interview another available adult living in the household. Interviews will be voluntary and will last approximately 10 minutes. Interviews will be carried out by trained field interviewers who will be further trained for this specific study before data collection begins. Some interviewers will be Spanish bilingual speakers so that they can conduct interviews in Spanish if needed.

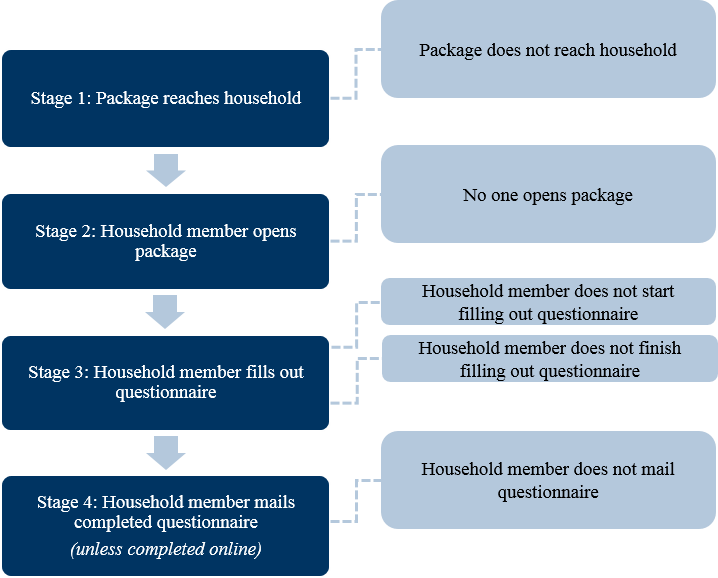

The goal of the interview is to understand the reason(s) for the household’s lack of response to the screener, with a focus on understanding at which stage this household’s response process was interrupted (e.g., did the NHES:2019 survey package reach the household, did the household members open it?). The interviewer also will collect basic demographic household characteristics; for example, whether any household members are eligible for the NHES topical surveys (generally, children in 12th grade or younger).4 Finally, the interview will include questions about characteristics that may be drivers of the nonrespondent status of the household, such as privacy and confidentiality concerns, busyness, topic salience, and attitudes toward surveys or the federal government (Brick and Williams 2013; Groves et al. 2004; Kulka et al. 1991; Singer and Presser 2008). Interviews will be conducted in both English and Spanish. Data quality control procedures will be undertaken; several options, such as audio recording or manager follow-up with a subset of participants, are currently being evaluated. The structured interview protocol and contact materials are currently being developed (see Attachment B in this document for an outline of the protocol’s content). The finalized procedures, interview protocol, and contact materials for the In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households will be submitted for OMB’s review with a 30-day public comment period in fall 2018.

Qualitative research is particularly useful for trying to understand how people make sense of their lives and experiences. To gain a deeper understanding of why some sample members do not respond to the NHES screener, approximately 80 semi-structured, qualitative interviews will be conducted with screener nonrespondents. These interviews are designed to be longer and provide richer and more nuanced information than the structured interviews described above.

Nonrespondents may be stratified and sampled to focus on a handful of key household characteristics available on the sampling frame that are likely to drive differences in reasons for nonresponse and could be used for targeting NHES materials and contact protocols in future administrations: (1) whether the household has children living in it, (2) whether the household is Hispanic or is expected to prefer to respond in Spanish, and (3) whether the household is located in an urban area or a rural area. A final sample design and sampling strata will be specified in the fall 2018 submission. In addition, the cases will be clustered near 2 to 4 U.S. cities and will be located within 70 miles of the center of those cities. The 70-mile radius will allow for sampling of rural addresses (e.g., villages and towns such as Sollitt, IL, which is 45 miles south of Chicago, IL and is a rural community with fewer than 100 people within the community). Approximately 480 households will be sampled to yield approximately 80 completed 90-minute interviews.

One possible design for the study of nonresponding households is to also follow up with a small sample (n= 50-100) of responding households for the 90-minute semi-structured, qualitative interviews. Data from responding households would provide a comparison to the data from the nonresponding households. Respondent sample cases could be stratified on whether they were early or late responders and on the same demographic characteristics used to identify cases for nonrespondent sampling. If differences are found between the responding and nonresponding groups, this will aid analyses by helping to hone in on the themes in the data from nonrespondents that may be related to nonresponse. If no differences are found between the responding and nonresponding groups, it will be a signal to look at some of the less common themes in the interview data for clues about nonrespondents’ unique characteristics or attitudes. In turn, these less common themes would provide future researchers with better information on which to base interview protocols for research into nonresponse.

Bates (2007) found that debriefing both respondents and nonrespondents to a mail survey yielded considerably more data from respondents than nonrespondents and that nonrespondents commonly did not remember receiving the mailed survey materials. Collecting data from respondents in addition to nonrespondents would help us to understand whether or not differences in household practices with mail are the linchpin to ABS-survey nonresponse in which contact materials are sent through the mail. Budget may limit our ability to add a sample of responding households. Final decisions and details about the sample design, and whether or not responding households will be included, will be provided for OMB review in fall 2018.

2.2.1 Recruitment

The following recruitment protocol will be used after the NHES:2019 screener data collection closes in late May 2019:

Sampled cases will be sent an advance letter that includes $2 or $5 cash5, invites them to participate in the in-person study, and indicates that someone will contact them to schedule an interview. The advance letter does not ask for a response or action from the household member. Its purpose is to inform the household that they will be contacted to schedule an interview at their house. All sampled cases will be offered an additional $120 cash incentive for completing the interview and this incentive will be mentioned in all recruitment materials. This incentive is designed to demonstrate to participants that their time and participation is valued and takes into account that the sample is comprised of households that have already shown reluctance to participate in the survey (see below for additional discussion of the incentive amount). Recruitment materials will be branded as coming from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

Recruitment phone calls will occur in two windows for sampled households that have phone numbers available on the sampling frame. One window will occur at the start of the recruitment period and the other halfway through the recruitment period. During each window, each household will be called twice. One voicemail will be left per calling window if the household does not answer the phone.

An in-person recruitment period where all households that have neither agreed nor declined to participate over the phone (or do not have a phone number available) will be visited by a recruiter. Recruiters will have an identification badge they will show to each household along with study forms to indicate that they are part of the study.

The phone and in-person recruiters will encourage the household to participate in the in-person interview and set up a time for a trained qualitative interviewer to do so. The recruiter will attempt to speak with the adult living at this address who usually opens the mail. Should that person not be available, they will attempt to speak to another available adult living in the household.

To maintain engagement and increase the likelihood that recruited households keep their scheduled appointments, the recruiters also will ask recruited households to provide contact information that can be used to keep them engaged and aware of their upcoming interview appointment. Depending on the type of contact information provided, recruited households will receive: (1) a confirmation email or text shortly after scheduling the appointment, and (2) a reminder email or text and a reminder phone call in the days leading up to the interview. The interviewer will then call the participant the morning of the interview to confirm he or she is still available to meet. If when the interviewer arrives, no one answers the door, the interviewer will leave a “Sorry I Missed You” card at the household. The card will indicate that he or she stopped by and will return at a later day and time. It also will contain a number the sample member can call to learn more about the study and/or schedule an interview. All interviewers will have an identification badge they will show to the household to indicate they are part of the study.6 Interviews will be carried out by trained qualitative interviewers who will be further trained for this specific study before data collection begins. Some interviewers will be Spanish bilingual speakers so that they can conduct interviews in Spanish if needed. All materials will be branded as coming from the National Center of Education Statistics (NCES).

The participant will receive a consent form to read and sign before the interview starts, and will be able to keep a copy of the form for their records. The details of obtaining consent and the consent forms will be submitted for OMB’s review with a 30-day public comment period in fall 2018.

2.2.1.1 Use of Incentives

Given the length of the interview and the fact that the target population is comprised of survey nonrespondents, an incentive will be offered to households who complete the interview. Some examples of other incentives in in-person data collections follow:

In a comparison study of incentive groups in qualitative research, 3 monetary groups ($25, $50, and $75) all resulted in greater willingness to participate in the survey than no incentive or a nonmonetary incentive (Kelly et al 2017).

Similar incentive amounts were used in experiments as part of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). In one experiment, a preincentive ($10 or $40 was mailed to sample members) and an additional $40 was offered to a small sub-set of nonresponders in later weeks in the data collection. The $80 total incentive increased response rates in both the screener and main survey by 10 and 12 percentage points respectively, and was more successful at recruiting different people (busy, college-educated, childless women, high-income men, and Hispanic men) into the sample than the $50 total incentive (Lepkowski et al. 2013).

The 2012/2014 Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), an international household survey of adult skills conducted in-person, offered $5 to screener respondents. PIACC offered an additional $50 to households who then completed the assessment in-person. PIAAC achieved an overall weighted response rate of 70.3% for the main study (Hogan et al. 2016).

The in-person household component of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) conducted an experiment beginning in 2008 for 5 rounds of the panel data collection. Households received $30, $50, or $70 for completing the survey. Response rates were higher for both the $50 and $70 incentive group relative to the $30 group, and the difference between the $70 (71.13%) and $50 (66.74%) groups was also statistically significant. In 2011, OMB approved the new $50 incentive for the MEPS collection.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) involves multiple health exams and tests for respondents. NHANES has various incentive amounts for different subgroups of people. The maximum incentive for adults ages 16 and older who agree to participate in the exam component at a preselected time is $125. The amount decreases as cooperation decreases (e.g., adults ages 16 and older who refuse the exam component at a preselected time is $90). Additional follow-ups include additional $30-$50 incentives. NHANES respondents from low-income households often perceive the medical exams as a tangible, direct benefit to their well-being, which will not be true of the NHES interviews, wherein the benefits of participation are civic engagement and volunteerism, which are comparatively indirect benefits.

In the National Food Acquisition and Purchase Survey (FoodAPS), all contacted households were offered $5. The week-long data collection which included training, a food acquisition diary with scanners, two CAPI interviews, one computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI), and 3 respondent initiated call-in periods, offered eligible households a multi-part incentive designed to encourage initial agreement to participate. A base of $100 was offered with additional $10-$20 to other household members who agreed to participate. The average household incentive was $180 with a range of $130-$230 depending on household size. A previous experiment was conducted using $50 as the base incentive with the average household incentive receiving $130 and a range of $80-$180 depending on household size. Results showed that providing the larger base incentive yielded higher response rates.

The Survey of Consumer Finance (SCF) analyzed field effort outcomes between 2007 and 2010 after the base incentive increased from $20 in 2007 to $50 in 2010. On average, the $50 group needed four fewer attempted contacts before agreeing to participate relative to families receiving no incentive (To 2015).

Though many large studies use in-person data collection methods and/or burden respondents in excess of 1 hour, no study is a good match in the same type of sample members, burden, methods, and respondent experience to the proposed study of nonresponding households. To fully understand this unique target population, it is crucial to ensure a large enough, representative, and cooperative sample. Additionally, the need for high quality data from these sample members is of paramount importance for understanding reasons of nonresponse in studies like NHES. Based on the varying literature on higher incentive amounts and the unique target population of nonrespondents, all households will be offered a $120 cash incentive for completing the interview and this incentive will be mentioned in all recruitment materials.

2.2.2 Qualitative interview protocol

Qualitative interviews will be voluntary and will last 90 minutes to allow time to obtain consent, give participants sufficient time to reflect on the more open-ended questions included in this protocol, and conduct observations. Because this is exploratory research (trying to find out why something is happening as opposed to testing a hypothesis) maximizing contact time with the participants and giving them enough space to discuss their experience is crucial. Interviews will be conducted in both English and Spanish. All interviews will be audio-recorded with participants’ permission7. They will consist of the following kinds of questions:

Qualitative interview questions that aim to gain a deep understanding of the household’s reasons for nonresponse and what might convince them to respond;

Questions adapted from the structured interviews for the qualitative interview protocol, such as conducting a household roster by asking about the other members of the households or asking if the participant remembers receiving the NHES mailings;

A mail interaction discussion, where the interviewer asks the participant to do things like “show me what you do with your mail when you get it” or “show me how you decide whether to open a piece of mail”; and

A request for feedback on NHES:2019 screener mailed materials.

2.2.3 Observations

The interview will conclude with the interviewer using a brief check list to make observations about the home and/or household members, beyond any observations recorded while interacting with the participant during the interview. Observations are important to include in qualitative research because interview questions can often only address attitudes or actions of which participants are cognitively aware. There are likely other observable aspects of participants’ lives that they may not explicitly connect to their lack of participation (e.g., how they organize their mail), as well as observable qualities that nonresponding households may have in common (e.g., whether they display children’s educational achievements). These observations will be used to capture such more nuanced indicators.

The qualitative interview protocol and contact materials are currently being developed (see Attachment B for an outline of the protocol’s content). The finalized procedures, interview protocol, and contact materials for the In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households will be submitted for OMB’s review with a 30-day public comment period in fall 2018.

The priority for analysis will be on identifying actionable responses to the themes identified in the interviewer observations and the participant responses and comments. The protocols for this study will be written with that aim in mind. Some global changes to NHES are likely to result from the In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households, but it is anticipated that most findings will be targeted at specific priority or hard-to-reach subgroups that can be identified prior to the start of data collection. This may include, for example, changing the timing or mode of nonresponse follow-up for certain subgroups, altering the wording or presentation of contact materials, or changing the value or timing of incentives.

To help ensure that the results of this study reach the maximum possible audience, contribute to the survey methodology literature, and serve as a resource for others conducting federal government household surveys (particularly those using ABS frames or contacting household by mail), it is anticipated that the findings may be shared through the following outlets:

An official NCES publication posted on the NCES website that summarizes the methodology and key findings of the study. This report will identify key themes from the interviews and propose actionable strategies that could be implemented in future administrations of NHES and other household surveys.

A manuscript, based on the above report, that is submitted to a leading survey methodology journal, such as Public Opinion Quarterly, the Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology, or Field Methods.

At least two presentations submitted to conferences such as the American Association for Public Opinion Research national conference or the Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology Research and Policy conference.

References

AAPOR Task Force on Survey Refusals. (2014). Current knowledge and considerations regarding survey refusals. American Association for Public Opinion Research.

AAPOR Task Force on Address-Based Sampling. (2016). Address-based sampling. American Association for Public Opinion Research.

Abraham, K., Maitland, A., and Bianchi, S. (2006). Nonresponse in the American Time Use Survey: Who is missing from the data and how much does it matter? Public Opinion Quarterly, 70, 676-703.

Ahlmark, N., Algren, M., Holmberg, T., Norredam, M., Nielsen, S., Blom, A., Bo, A., and Juel, K. (2015). Survey nonresponse among ethnic minorities in a national health survey -- a mixed-method study of participation, barriers, and potentials. Ethnicity & Health, 20, 611-632.

Amaya, A., and Harring, J. (2017). Assessing the effect of social integration on unit nonresponse in household surveys. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology, 2017, 480-508.

ASA Task Force on Improving the Climate for Surveys. (2017). Interim report. American Association for Public Opinion Research.

Bates, N. (2007). The Simplified Questionnaire Report. Results from the Debriefing Interviews. Accesses 4/10/18 from https://www.census.gov/srd/papers/pdf/rsm2007-03.pdf

Brick, J., and Williams, D. (2013). Explaining rising nonresponse rates in cross-sectional surveys. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 645, 36-59.

Czajka, J., and Beyler, A. (2016). Declining response rates in federal surveys. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC.

Groves, R., Cialdini, R., and Couper, M. (1992). Understanding the decision to participate in a survey. Public Opinion Quarterly, 56, 475-495.

Groves, R., Presser, S., Dipko, S. (2004). The role of topic interest in survey participation decisions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 68, 2-31.

Harcombe, H., Derrett, S., Herbison, P., and McBride, D. (2011). "Do I really want to do this?" Longitudinal cohort survey participants' perspectives on postal survey design: a qualitative study. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 1-9.

Hogan, J., Thornton, N., Diaz-Hoffmann, L., Mohadjer, L., Krenzke, T., Li, J., VanDeKerckhove, W., Yamamoto, K., and Khorramdel, L. (2016). U.S. Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) 2012/2014: Main Study and National Supplement Technical Report (NCES 2016-036REV). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Available from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch

Kelly, B., Margolis, M., McCormack, L., LeBaron, P.A., and Chowdhury, D. (2017). What affects people’s willingness to participate in qualitative research? An experimental comparison of five incentives. In Field Methods (29).

Kulka, R. A., Holt, N. A., Carter, W., and Dowd, K. L. (1991). Self-reports of time pressures,

concerns for privacy, and participation in the 1990 mail Census. Proceedings of the Bureau of the Census Annual Research Conference, Arlington, VA.

Lepkowski, J., Mosher, W., Groves, R., West, B., Wagner, J., and Gu, H. (2013). Responsive design weighting, and variance estimation in the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth. 2(158). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/22069

Little, R. and Vartivarian, S. (2005). Does weighting for nonresponse increase the variance of survey means? Survey Methodology, 31, 161-168.

McPhee, C., Bielick, S., Masterton, M., Flores, L., Parmer, R., Masica, S., Shin, H., Stern, S., and McGowan, H. (2015). National Household Education Surveys Program of 2012: Data file user’s manual (NCES 2015-030). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC.

McPhee, C., Jackson, M., Bielick, S., Masterton, M., Battle, D., McQuiggan, M., Payri, M., Cox, C., and Medway, R. (2018). National Household Education Surveys Program of 2016: Data file user’s manual (NCES 2017-100). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC.

Nakash, R., Hutton, J., Lamb, S., Gates, S., and Fisher, J. (2008). Response and non-response to postal questionnaire follow-up in a clinical trial – a qualitative study of the patient's perspective. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 14, 226-235.

O’Neill, G. and Sincavage, J. (2004). Response Analysis Survey: A Qualitative look at Response and Nonresponse in the American Time Use Survey. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/ore/pdf/st040140.pdf Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Presser, S., and McCulloch, S. (2011). The growth of survey research in the United States: Government-sponsored surveys, 1984–2004. Social Science Research, 40, 1019-1024.

Singer, E., and Presser, S. (2008). Privacy, confidentiality, and respondent burden as factors in telephone survey nonresponse. In J. M. Lepkowski, C. Tucker, J. M. Brick, E. D. de Leeuw, L. Japec, P. J. Lavrakas, M. W. Link, and R. L. Sangster (Eds.), Advances in telephone survey methodology (449–470). New York: John Wiley.

Singer, E. (2016). Reflections on surveys’ past and future. Journal of Statistics and Survey Methodology, 4, 463-475.

To, N. (2015). Review of Federal Survey Program Experiences with Incentives. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/cex/research_papers/pdf/Review-of-Incentive-Experiences-Report.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (2014). Design and Methodology: American Community Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/methodology/design-and-methodology.html.

United States Census Bureau. (2017). CAPI Manual for NHIS field representatives. Retrieved from https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Survey_Questionnaires/NHIS/2017/frmanual.pdf

User’s guide for the paradata file and codebook documentation: Special file covering 2011-2015 of the National Survey of Family Growth. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nsfg/NSFG2011_2015_Paradata_UserGuide.pdf

Walsh, R., Dahlhamer, J., and Bates, N. (2013). Assessing interviewer observations in the NHIS. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/296847278_Assessing_Interviewer_Observations_in_the_NHIS

Zelnack, M. and David, M. (2013). Impact of Multiple Contacts by Computer-Assisted Telephone Interview and Computer-Assisted Personal Interview on Final Interview Outcome in the American Community Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2013/acs/2013_Zelenak_01.pdf

Attachment A. Count of sampled households by response status, and weighted screener response rate, by selected household characteristics: NHES:2016

Table A-1. Count of sampled households by response status, and weighted screener response rate, by selected household characteristics

Household characteristic |

Count of sampled households |

Weighted screener response rate |

||||

Total |

Responded |

Refused |

Ineligible |

Unknown eligibility |

||

Total |

206,000 |

115,342 |

1,606 |

19,136 |

69,916 |

66.4 |

Frame variables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sampling stratum |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tracts with 25% or more Black persons |

41,200 |

18,593 |

330 |

5,472 |

16,805 |

58.2 |

Tracts with 40% or more Hispanic persons |

30,900 |

13,906 |

206 |

3,404 |

13,384 |

55.9 |

All other tracts |

133,900 |

82,843 |

1,070 |

10,260 |

39,727 |

69.4 |

Tract poverty rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

20% or higher |

64,760 |

29,030 |

468 |

9,025 |

26,237 |

59.5 |

Below 20% |

141,240 |

86,312 |

1,138 |

10,111 |

43,679 |

68.9 |

Census region1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Northeast |

35,398 |

20,341 |

281 |

3,019 |

11,757 |

67.2 |

South |

82,478 |

43,580 |

662 |

8,500 |

29,736 |

64.0 |

Midwest |

42,817 |

25,859 |

336 |

4,056 |

12,566 |

70.6 |

West |

45,307 |

25,562 |

327 |

3,561 |

15,857 |

65.6 |

Route type |

|

|

|

|

|

|

City style/street |

155,113 |

93,178 |

1,252 |

11,302 |

49,381 |

68.4 |

P.O. box |

2,181 |

785 |

19 |

845 |

532 |

74.5 |

High rise |

48,507 |

21,276 |

333 |

6,958 |

19,940 |

58.9 |

Rural route |

199 |

103 |

2 |

31 |

63 |

67.8 |

Delivery point is a drop point |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

3,784 |

1,558 |

50 |

573 |

1,603 |

57.5 |

No |

202,216 |

113,784 |

1,556 |

18,563 |

68,313 |

66.5 |

Dwelling type |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Single family |

150,545 |

91,419 |

1,219 |

10,650 |

47,257 |

68.9 |

Multiple unit |

53,274 |

23,138 |

368 |

7,641 |

22,127 |

58.5 |

Dwelling type unknown |

2,181 |

785 |

19 |

845 |

532 |

74.5 |

Number of adults in household |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

78,318 |

39,090 |

589 |

8,008 |

30,631 |

61.1 |

2 |

50,592 |

32,743 |

395 |

2,388 |

15,066 |

70.6 |

3 or 4 |

38,440 |

26,435 |

288 |

1,225 |

10,492 |

73.1 |

5–8 |

9,200 |

6,321 |

63 |

260 |

2,556 |

72.7 |

Number of adults unknown |

29,450 |

10,753 |

271 |

7,255 |

11,171 |

61.6 |

Children in household |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

47,236 |

28,146 |

297 |

2,415 |

16,378 |

65.8 |

No/unknown |

158,764 |

87,196 |

1,309 |

16,721 |

53,538 |

66.5 |

See notes at end of table.

Table A-1. Count of sampled households by response status, and weighted screener response rate, by selected household characteristics—Continued

Household characteristic |

Count of sampled households |

Weighted screener response rate |

||||

Total |

Responded |

Refused |

Ineligible |

Unknown eligibility |

||

Phone number matched |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

134,574 |

84,010 |

1,099 |

7,687 |

41,778 |

69.4 |

No |

71,426 |

31,332 |

507 |

11,449 |

28,138 |

60.6 |

Home tenure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rent |

52,220 |

23,091 |

330 |

6,037 |

22,762 |

56.6 |

Own |

120,115 |

79,806 |

988 |

5,165 |

34,156 |

71.6 |

Home tenure unknown |

33,665 |

12,445 |

288 |

7,934 |

12,998 |

61.0 |

Income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

$50,000 or less |

83,949 |

43,740 |

673 |

8,065 |

31,471 |

62.8 |

$50,001–$100,000 |

55,967 |

36,271 |

401 |

2,446 |

16,849 |

70.2 |

$100,001–$150,000 |

21,839 |

14,376 |

147 |

822 |

6,494 |

70.5 |

$150,001 or more |

14,772 |

10,189 |

114 |

544 |

3,925 |

73.3 |

Income unknown |

29,473 |

10,766 |

271 |

7,259 |

11,177 |

61.6 |

Treatment variables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Assigned mode at first screener mailing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Paper |

171,000 |

97,315 |

1,256 |

15,819 |

56,610 |

67.2 |

$5 incentive |

126,000 |

72,064 |

914 |

11,593 |

41,429 |

67.5 |

Other incentive ($2 or modeled) |

45,000 |

25,251 |

342 |

4,226 |

15,181 |

66.5 |

Web2 |

35,000 |

18,027 |

350 |

3,317 |

13,306 |

62.1 |

Screener incentive |

|

|

|

|

|

|

$5 |

161,000 |

90,091 |

1,264 |

14,910 |

54,735 |

66.3 |

$2 |

10,000 |

5,449 |

71 |

922 |

3,558 |

64.9 |

Modeled incentives3 |

35,000 |

19,802 |

271 |

3,304 |

11,623 |

67.0 |

$0 |

1,750 |

1,393 |

18 |

55 |

284 |

82.8 |

$2 |

6,996 |

5,176 |

63 |

210 |

1,547 |

77.2 |

$5 |

21,007 |

11,502 |

150 |

1,932 |

7,423 |

64.2 |

$10 |

5,247 |

1,731 |

40 |

1,107 |

2,369 |

54.0 |

1 Northeast includes Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. South includes Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, District of Columbia, Maryland, Delaware, West Virginia, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Kentucky, Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma. Midwest includes North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio. West includes New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, Washington, Oregon, California, Hawaii, and Alaska.

2All households assigned to the web mode received a $5 screener incentive.

3Incentives in the modeled group were assigned according to predicted response propensity, with households with a higher predicted response propensity receiving a lower incentive.

NOTE: Weighted screener response rate is calculated using the single-eligibility formula (AAPOR RR3).

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, National Household Education Surveys Program (NHES) of 2016.

Attachment B. In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households Interview Protocol Development Plan

As part of the In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households, in-person interviews will be conducted with selected NHES:2019 screener nonrespondents. The purpose of these interviews is to understand the reasons for the rising NHES screener nonresponse rate. They will primarily address the following research questions:

What are the barriers to response among screener nonrespondents to NHES?

What are the characteristics of nonresponding households?

Just over 300 in-person interviews will be conducted with NHES:2019 screener nonrespondents: approximately 230 10-minute structured interviews and about 80 90-minute qualitative interviews. Interviewers also will conduct observations of participants’ neighborhoods and homes for the structured interviews.

This document outlines the plan for developing the following instruments to be used during the interviews:

an address/neighborhood observation instrument, to be used before both the structured and qualitative interviews;

a structured interview instrument; and

a qualitative interview instrument, including household observations.

This plan provides an overview of the constructs to be measured by each instrument, notes other surveys that have measured the same constructs (when available), and provides examples of the types of questions that will be asked.

The address/neighborhood observation instrument and the two interview protocols, along with all contact materials for the In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households are currently being developed (see further details about the study in the Supporting Statement Parts A and B). The finalized procedures and materials for the In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households will be submitted for OMB’s review with a 30-day public comment period in fall 2018.

B1. Structured interview

The structured interviews will be about 10 minutes long and will be conducted with approximately 230 households in 2-3 United States cities and nearby areas. Before attempting to interview a household member, interviewers will first conduct a 5-minute observation of the sampled address and neighborhood. When possible, existing items will be taken or adapted from other national surveys’ interview and observation instruments, such as the American Community Survey (ACS), the Current Population Survey (CPS), the Health and Retirement Survey (HRS), the National Survey on Family Growth (NSFG), and the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). We recognize that the content outlined below would likely exceed the duration of a 10-minute interview. Ten minutes of the proposed content below will be chosen for the final interview protocols.

B1.1 Address/neighborhood observation instrument

The objective of these observations is to determine the types of addresses that are prone to nonresponse or having their NHES mailings be undeliverable and to assess the accuracy of the information available on the frame for such addresses. The observation form will be based on items from the Neighborhood Observation Instrument (NOI) and the Contact History Instrument (CHI). It will list a series of characteristics that interviewers will look for and mark off when they observe that address or neighborhood. There will also be space for entering notes that might provide helpful context. The observation form will include about 15 questions and will measure the following characteristics:

Household residential occupancy status – If a household is vacant (whether permanently or seasonally) or nonresidential, that might explain why there has not been a response to the survey. Collecting this type of information will also help assess the accuracy of information available on the frame, as well as the accuracy of the USPS mail returns. Interviewers will note whether the address appears to be vacant (e.g., address is not protected from the exterior environment because of a missing roof or window, signs are available indicating the address will be demolished), nonresidential (e.g., address is used as a storage area or has been converted to a school), or seasonal (e.g., vacation home). The vacancy or seasonal status definition used by the NHIS or the Census Bureau (https://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/definitions.pdf) will be provided for interviewers as a cue for assessing the vacancy or seasonal status of a household. A comparison of frame information about the address type to nonresponse study data will help us understand the validity of address based sampling (ABS) frame data. A comparison of USPS mail return information (e.g. “undeliverable as addressed,” vacant) to nonresponse study data will help us understand the validity of USPS mail return information.

Structure type – These items will assess whether the address is a single-family unit (including town/row houses), a multi-unit building (high-rise or not), a mobile or seasonal home. Certain address types (such as multi-unit buildings or mobile homes) might be less likely to consistently receive their mail; this observation will also assess the accuracy of related information collected on the frame. These items will be adapted from the ACS or the NSFG NOI form.

Household eligibility for NHES topicals – These items will assess whether the household occupants are eligible for the NHES topical surveys by directing interviewers to look for evidence of children being present in the household. Examples of cues recorded by NSFG NOI interviewers include child-focused objects outside the house (such as toys, strollers, bicycles, or swing sets) or the sound of children’s voices coming from the household. A list of specific cues to look for will be provided to the interviewers. The observation questionnaire will also ask interviewers to judge specifically whether they think younger children (less than 6 years of age, eligible for ECPP) or older children (eligible for PFI) reside at the address; this type of age-specific observation is currently done in both the NHIS (children under age 6) and the NSFG (children under age 15).

Mail access – An item will be included that will ask the interviewer to assess how the household receives their mail (e.g., mail slot, mail box attached to their home, mailbox at the end of a driveway, mail room in the building, drop point, etc.). If access to the mail is limited or retrieving mail is time consuming, this might be a driver of nonresponse. If the interviewer cannot clearly identify how the household receives its mail, an item asking about this will be posed during the structured interview with the respondent.

Household access barriers – These items will ask the interviewer to observe any impediments to accessing the address, which might indicate a lower likelihood of mail successfully reaching this address or that the individuals living there prefer not to be contacted. These items will be adapted from the NSFG NOI and will ask whether the address is in a gated community, has a doorkeeper or an access system controlled through an intercom, or if any other signs discouraging contact are present (e.g., “no trespassing”, “watch out for a dog”).

Household income – – An item will be included that will ask the interviewers to estimate household income. This item will be based on the NHIS instrument. They can observe the conditions of the address, the number and types of cars, and use any knowledge they might already have of the neighborhood in their estimate. Response options will be limited to options such as “top/middle/bottom third of the population”, etc. This item will be used to assess the relative accuracy of the income information available on the frame. It will also help determine whether higher and lower income participants face different barriers to response. Additionally, estimates from real estate websites (e.g. www.zillow.com) that include rent and/or home values may be used to validate interview observations and used as additional household data.

Neighborhood characteristics – Items to assess the characteristics of the neighborhood will also be included. The constructs that will be assessed include:

Physical/social disorder indicators –These items will help assess the climate in which the address is located; safety concerns or indicators of general disorder might predict a lower likelihood of consistently receiving one’s mail or a hesitancy to respond to government surveys. Some of these items will be adapted from the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood survey; they will include items that assess the presence of physical disorder (e.g., presence of litter, abandoned cars, boarded up windows, graffiti), neighborhood safety concerns (e.g., large number of households with window bars or gratings on doors or windows), and social disorder (e.g., presence of gangs, homeless people, prostitutes).

Presence of non-English speakers – Other items will assess whether there is evidence of a high concentration of non-English speaking individuals (e.g., store signs are predominantly written in a non-English language). This information will help assess the accuracy of attempts to predict which addresses might prefer Spanish-language materials, as well as determining the prevalence of other populations that might ideally receive non-English materials.

B1.2 Interview instrument

B1.2.1 Introductory text

Given the importance of initial doorstep interactions for building rapport with a household and obtaining cooperation (Groves & McGonagle 2001; Sinibaldi et al. 2009) – particularly for this study’s target population of survey nonrespondents – interviewers will use a script for the introduction. The introduction will briefly state what NHES is, who is the conducting agency, and who is administering the In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households. The script will also explain that the purpose of the visit is to follow-up with certain NHES households to understand their experience with this study and with surveys in general. Interviewers will also remind participants that the interview is voluntary, will only take 10 minutes, and that respondents will receive a $25 cash token of appreciation for participating. Interviewers will then ask if the participant has any questions about the study and confirm that he/she is willing to participate. American Institutes for Research (AIR) will oversee the interviews and use a subcontractor to administer them.

B1.2.2 Screener

The interviewer will attempt to speak to the adult who is usually responsible for handling a household’s mail (since the NHES:2019 survey contacts will be sent to the household by mail). The interview screener protocol will include items based on the 2010 Decennial Census Nonresponse Follow-up interview screener to:

confirm that the address is the sampled address,

ask if the household member that answered the door is usually the one who handles the mail for the household,

confirm that the household member is over the age of 18, and

confirm that the household member resided at the address during the months the original requests were sent out.

If the person fails to meet any of the criteria listed above, the interviewer will ask to speak with the adult who usually handled the mail during the time frame the NHES materials were sent out. If that individual is not available, the interview will be conducted with any available adult that resided at the address during the survey administration. If none of the available household members resided at the address during the NHES:2019 data collection timeframe or if an eligible person no longer lives there or is deceased, an interview will not be completed at the address. If an eligible person exists but is just temporarily away, the interviewer will attempt to return at a time when that person is expected to be available.

B1.2.3 General survey attitudes and experiences

After the individual is screened, the first section of the interview will include items that ask about participants’ attitudes toward and experiences with surveys and mail.

Attitude towards surveys – The interview will include an item that specifically asks about the household’s attitudes towards participating in surveys in general (e.g., To what extent do you like or dislike doing surveys?).

Drivers of nonresponse- These items will focus on topics found to be drivers of nonresponse in other studies, such as:

Attitude towards the government – These items will be adapted from existing Pew surveys or the General Social Survey (GSS) (e.g., Do you think the federal government is having a positive or negative effect on the way things are going in this country today? Which of the following best describes how you feel about the federal government?).

Privacy concerns – This section will ask about general attitudes towards privacy and confidentiality. Items could be adapted from existing Pew surveys or the GSS (e.g., In general, how confident do you feel that companies or organizations keep your data private? How much control do you feel you have over your personal information?).

Perceived busyness – These items will be adapted from the Socio-cultural shifts in Flanders survey (SCV) and will ask about how busy the respondent feels in their daily life (e.g., How busy do you feel in general? How many hours of free time do you have on a week/workday? How many hours of free time do you have on a weekend/nonworkday?).

Importance of social surveys and research – These items will be adapted from existing Pew surveys (e.g., How important do you think the Census is for the United States? Do you believe that answering and sending back government surveys would personally benefit you in any way, personally harm you, or neither benefit nor harm you?).

Altruism or civic/community involvement – These items will be adapted from existing Pew surveys, GSS, and/or the Voting and Registration Supplement for the CPS (e.g., How much do you agree with the following statement? – I think it is my civic duty as a citizen to agree to participate when asked in most surveys that come from a government organization. Are you currently active in any types of groups or organizations? How often do you do volunteer work?).

Mail habits and attitudes – To assess how much solicitation the household receives and how the household feels about mail, we will adapt items from the 2016 USPS Mail Moments Survey (e.g., How much mail does your household receive daily? How frequently mail is attended to? What is the proportion of mail packages that are discarded? How much do you enjoy receiving mail?).

Drivers of response – This section will include an item attempting to determine what factors participants weigh when deciding whether to complete a survey request (e.g., whether they care about the topic, perceived burden, who is conducting and who is administering the survey, incentive, mode, and other aspects). These items also will aim at understanding what features of the survey package may have compelled this household to respond to the NHES survey request. However, the responses to these kinds of hypothetical questions will need to be interpreted with caution because they are not measures of actual response behavior and because the presence of an interviewer may influence someone to respond more positively to questions about survey response than reality. They could ask about topics such as what amount or type of incentive (if any) would motivate them to participate, whether the survey topic is important in deciding whether to participate (and if so, whether education, as a topic, is a motivating or demotivating factor for them), and whether they would want to learn about the survey results. These items also could help assess whether, for at least some nonresponding households, there is really nothing that could be done to get them to respond. Most items in this section will be newly developed for this interview.

B1.2.4 Experience as an NHES sample member

The next set of items will focus on whether the individual remembers receiving the NHES:2019 screener invitation mailing. Similar to nonresponse follow-up studies conducted as part of both the ACS (Nichols 2012) and the American Time Use Survey (O'Neill & Sincavage 2004), interviewers will ask participants whether they remember different aspects of the mailings that were sent to the household. The interview protocol will assess the following topics:

Identifying the break in the response process – The interviewer will first ask whether the household member remembers receiving the NHES:2019 materials. The interviewer will have paper copies of the materials in both English and Spanish and for households that are uncertain, an example NHES mailing package will be shown. The interviewer will determine which survey protocol the household received based on NHES:2019 operations files and will bring printed examples of the recruitment materials used with that protocol to the interview. The language of materials will be matched to the household’s language preference. The following NHES:2019 materials are one example of what may be provided:

Advance Letter (NHES-10LB(MW))

Initial screener invitation letter (NHES-11LB(W))

Screener pressure-sealed mailer (with userID) (0939-12PB(W))

Second screener mail package reminder letter (NHES-12LB(W))

Third screener mail package reminder letter (NHES-13LB(W))

Fourth screener mail package reminder letter (NHES-14LB(W))

English/Spanish bilingual Commonly Asked Questions mail package insert

English Paper Screener (NHES-11BE) or Spanish Paper Screener (NHES-11BE(S))

For household members that remember receiving any of the materials, these items will attempt to pinpoint the stage at which the survey response process was halted (see Exhibit 1 for stages).

Exhibit. 1 Stages of Response Process and Potential Interruptions

For example, items will ask: Did you open any of the packages (or discard them without opening)? Did you begin filling out the survey? Did you finish filling out the survey? Do you remember anything other than the cover letter and questionnaire being included in the invitation package (to determine whether the household noticed the cash incentive)? Once the response break is identified, respondents will be probed on the reason for that break (e.g., Why did you decide to throw this away without opening it? What made you decide not to send this back?). The interviewer’s goal during this section is to determine as specifically as possible why the participant did not respond to the NHES survey request.

Identifying factors that would encourage response – The interviewer will then ask a few questions to try to identify what things the participant likes or does not like about the mailing protocol and what he or she would change (e.g., Do you remember seeing any cash in the survey mailing? Do you like the text/fonts/or layouts of the materials? Do you like the appearance of the envelopes?). For any aspects identified as suboptimal by the respondent, the interviewer will try to probe to understand what kind of change(s) would be needed to make the person respond, although the responses to these kinds of hypothetical questions will need to be interpreted with caution.

B1.2.5 Household details

The structured interview will also collect information about the sampled household more generally. This information can help us understand household-level correlates with nonresponse and potential impacts of nonresponse on NHES survey estimates which may not be adjustable with weights. The household related items will include the following:

Eligibility for topical surveys – The NHES:2019 target population is households with children. In order to compare the interviewed households with the population of interest, the protocol will include items that ask: Are there are children in the household? What age are they? In what grade/ grade equivalent are they?

Other household characteristics – The interview will also include items about other household characteristics of interest (both for analysis purposes and to confirm the accuracy of information available on the frame), such as: What is the total number of people living in your household? What is the primary language spoken at home? Do you rent or own your home? These items can be adapted from NHES or ACS.

Respondent demographics – The final section of the interview protocol will collect respondent demographics such as sex, race/ethnicity, and education level of the person who responded to the interview using items adapted from NHES or ACS.

Given that the sample members selected for the In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households will consist of previous nonresponders to NHES:2019, we are concerned about their willingness to respond in the in-person study. To mitigate this, should a household member refuse the structured interview immediately, interviewers will attempt to ask 2-3 brief questions to try to understand whether they received the mailed survey package and whether they have children eligible for the study. Asking these questions is currently under consideration. Final decisions and details about this operation will be provided for review in fall 2018 clearance request.

B2. Qualitative interview

The qualitative interviews will be 90 minutes long and will be conducted with approximately 80 households in 2-3 United States cities and nearby areas. The interview will consist of several parts:

An introduction to build rapport and a brief screener to ensure the interviewer is speaking to the correct person (5 minutes);

Qualitative interview questions about household values and attitudes (45 minutes);

A mail interaction discussion (10 minutes);

A request for feedback on NHES:2019 screener mailed materials (20 minutes);

A household observation (5 minutes); and

A brief concluding discussion that includes giving the participant his or her incentive (5 minutes).

This section lists the topics to be measured by each section of the interview instrument, notes other surveys that have measured the same topics (when available), and provides examples of the types of questions that will be asked.

B2.1 Interview instrument

B2.1.1 Introductory text

Though the qualitative interview participants have had some interaction with a recruiter, the introduction will briefly remind them what NHES is, who is the conducting agency, and who is administering the In-Person Study of NHES:2019 Nonresponding Households. The script will also explain that the purpose of the visit is to follow-up with certain NHES households to understand their experience with this study and with surveys in general. Interviewers will also remind participants that the interview is voluntary, will take 90 minutes, and that respondents will receive a $120 cash token of appreciation for participating. Interviewers will then ask if the participant has any questions about the study and confirm that he/she is willing to participate.

B2.1.2 Screener

Although this information would have been covered during the recruitment call, the interview will also use a brief screener to confirm that the interviewer is speaking with the recruited person and that this person is eligible to participate. The screener will confirm the following:

that the address is the sampled address,

that the participant is over the age of 18, and

that the participant resided at the address during the months the original requests were sent out.

If any of the above is not true, the interviewer will determine if any other eligible household members are home and willing to complete the interview. The interviewer will also re-confirm whether the participant is the household member who normally handles the mail (since this will have already been addressed during recruitment); though it is preferable to interview the person who handles the mail, this will not be a firm requirement for participating in the interview. If no eligible individuals are currently available and they are just temporarily away from the home, the interviewer will attempt to reschedule the interview. If an eligible person no longer lives there or is deceased, the interview will not be completed at this address. The screener items will be based on those included in the 2010 Decennial Census Nonresponse Follow-up interview screener.

B2.1.3 Qualitative interview items

Due to a lack of existing published studies using this methodology, the items in this section will largely be newly created for this study and will be designed in partnership with qualitative experts from AIR. The purpose of these items is to gather in-depth information about the household, their reasons for not responding to mailed NHES:2019 screener/survey requests, and their reflections on what might make them respond to future requests. The interviewer will also ask about general attitudes on topics that may be drivers of nonresponse in general (e.g., privacy attitudes, feelings about the federal government making survey requests). The interview will be comprised of open-ended questions (required to be asked of all participants) and suggested probes to help the interviewers explore all dimensions of a given topic. Interviewers will start with broad questions about surveys and will gradually ask more specific questions as they dive deeper into topics raised by the participant. They will take the time to understand the thought process underlying responses; for example, general probes such as “Can you walk me through how that happened?” or “Can you tell me why you did this?” will be used to encourage reflection. Questions will cover the following topics:

Attitudes towards surveys – Questions that ask about their general feelings and experience with surveys will be asked here. For example: How do you react when you receive a survey in the mail? Tell me about a time you responded to a mailed survey. How do you feel about doing surveys online? How does the appearance of legitimacy affect your attitudes and behaviors? How do you know that a survey is legitimate?

Reasons for not responding – Questions that try to understand why they didn’t respond to the survey also will be asked. For example: What stopped you from opening the envelope? What stopped you from filling out the survey?

General attitudes towards privacy and confidentiality – Questions will be included that ask about general attitudes towards privacy and confidentiality. Items could be adapted from existing Pew surveys, such as: What does privacy mean to you? How do you feel about companies or organizations keeping your data private? How do you feel about the amount of control you have over your personal information? What are some things you do to protect your personal information?

Attitudes towards the government and government requests for information – How do you feel about the way things are going in this country? How you do feel about the government’s role in your everyday life? What do you think the government’s role should be in conducting research?

Altruism or civic/community involvement – These items will be adapted from existing Pew surveys such as: Tell me how you feel about your community. Are you a member of any social, civic, professional, religious or spiritual groups? Tell me about any volunteer work you might do.