BRFSS - SOGI Literature Review FEB2017

BRFSS-SOGI Lit Review Feb 2017_Final.docx

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)

BRFSS - SOGI Literature Review FEB2017

OMB: 0920-1061

Submitted

to: Division

of Population Health National

Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention Submitted

by: 126

College Street, Suite 2 Burlington,

VT 05401

Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention Behavioral Risk Factor

Surveillance System Sexual Orientation and Gender Literature Review:

Summaries

From February 2017

March

3, 2017

Carol

Pierannunzi

ICF

In order to generate this February 2017 literature for CDC, ICF first used a keyword search strategy to identify recent literature concerning the current state of the knowledge on developing and fielding sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) questions in surveys. Two ICF researchers searched using the following keywords: “sexual orientation”, “sexual identity”, “gender identity”, “transgender”, “national survey”, “federal survey”, “health survey”, “research”. Additionally, ICF used a key source search strategy whereby researchers searched for literature that cited either of the following key sources:

The GenIUSS Group. (2014). Best practices for asking questions to identify transgender and other gender minority respondents on population-based surveys. J.L. Herman (Ed.). Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

ICF employed these strategies to search through the following databases: Academic Search Complete, Google Scholar, PubMed, and Taylor & Francis Medical Library. ICF researchers selected articles for inclusion in the literature review based on recency (with more recently published articles favored over older articles) and relevance to CDC interests (as judged by the researchers). In this document, ICF summarized the following ten articles:

Baldwin, A., Dodge, B., Schick, V., et al. (2015). Sexual Self-Identification Among Behaviorally Bisexual Men in the Midwestern United States. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(7):2015-2026.

Bränström, R. (2017). Minority Stress Factors as Mediators of Sexual Orientation Disparities in Mental Health Treatment: A Longitudinal Population-Based Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, DOI: 10.1136/jech-2016-207943.

Eliason, M.J., Radix, A., McElroy, J.A., et al. (2016). The “Something Else” of Sexual Orientation: Measuring Sexual Identities of Older Lesbian and Bisexual Women Using National Health Interview Survey Questions. Women's Health Issues, 26(51):571-580.

Elliott, M.N., Kanouse, D.E., Burkhart, Q., et al. (2015). Sexual Minorities in England Have Poorer Health and Worse Health Care Experiences: A National Survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(1):9-16.

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.I. and Kim, H.J. (2017). The Science of Conducting Research With LGBT Older Adults- An Introduction to Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS). The Gerontologist, 57(S1):S1-S14.

Galupo, M.P., Lomash, E., and Mitchell, R.C. (2017). “All of My Lovers Fit Into This Scale”: Sexual Minority Individuals’ Responses to Two Novel Measures of Sexual Orientation. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(2):145-165.

Galupo, M.P., Ramirez, J.L., and Pulice-Farrow, L. (2016): “Regardless of Their Gender”: Descriptions of Sexual Identity among Bisexual, Pansexual, and Queer Identified Individuals. Journal of Bisexuality, DOI: 10.1080/15299716.2016.1228491

Gates, G. (January 11, 2017). In US, More Adults Identifying as LGBT. Available at: http://www.gallup.com/poll/201731/lgbt-identification-rises.aspx. Accessed on March 2, 2017.

Lombardi, E. and Banik, A. (2016). The Utility of the Two-Step Gender Measure Within Trans and Cis Populations. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13(3):288–296.

Swanbrow Becker, M.A., Nemeth Roberts, S.F., Ritts, S.M., Branagan, W.T., Warner, A.R., Clark, S.L. (2017). Supporting Transgender College Students: Implications for Clinical Intervention and Campus Prevention. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, DOI: 10.1080/87568225.2016.1253441.

Additionally, in the Appendix that follows the summaries, ICF researchers present the specific SOGI items described in nine of the ten articles.

Citation:

Baldwin, A., Dodge, B., Schick, V., et al. (2015). Sexual Self-Identification Among Behaviorally Bisexual Men in the Midwestern United States. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(7):2015-2026.

Summary:

A substantial body of research demonstrates the insufficiency of mutually exclusive sexual orientation categories, the imperfect correlation between orientation categories and sexual identities, as well as the flexibility and instability of these various categories over time and across different romantic-sexual relationships. Recognizing the unreliability of these categories in appealing to and describing human populations, clinical and public health nomenclature has begun to shift from orientation/identity-based target or ‘‘risk’’ populations to behavior-based populations, as evidenced by the adoption of the term ‘‘men who have sex with men (MSM)’’. Nevertheless, in separating sexual identity from sexual behavior through the use of acronyms like MSM, the specific meanings individuals attach to their sexuality are obscured and thus go unexplored. Previous work has called for a reevaluation of the role of sexual identity in public health efforts and a better understanding of the variations in identity among members of sexual minorities.

Research on identity among bisexual men has generally been conducted on samples of men who self-identify as ‘‘bisexual,’’ often in combined MSM samples, and little is known about sexual self-identification among behaviorally bisexual men. Recent studies of behaviorally bisexual men, however, emphasize the need to recognize the complexities of their sexual lives and health implications in terms of both risk and resilience. In this article, the authors present the analysis of qualitative data from interviews with 77 behaviorally bisexual men regarding their sexual self-identification and the ways in which such identification may be related to other health issues in their everyday lives. Men were eligible to participate if they reported engaging in oral, vaginal, and/or anal sex with at least one man and at least one woman during the past six months, regardless of how they identified their sexuality.

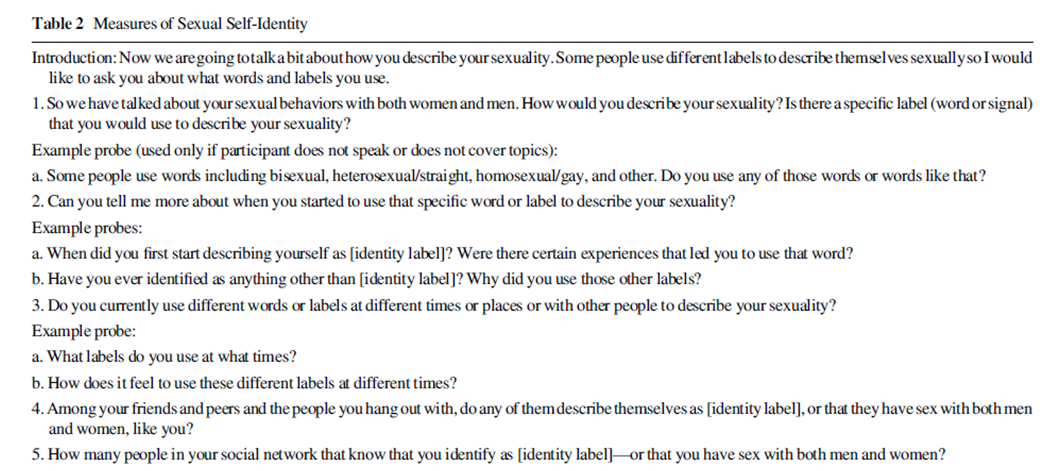

All participants completed 90-minute, in-depth, semi-structured interviews with a trained research associate. In order to gain a deeper understanding of participants’ experiences and expressions of sexual identity, questions were designed to elicit narratives from participants regarding use or nonuse of sexual identity labels, patterns and meanings of sexual identity labels in various times and contexts, as well as sexual identification among other individuals in the participants’ social networks. (Measures of sexual self-identity are included in the Appendix.)

Overall, participants’ sexual self-identification was exceptionally diverse. Three primary themes emerged: (1) a resistance to, or rejection of, using sexual self-identity labels; (2) concurrent use of multiple identity categories and the strategic deployment of multiple sexual identity labels; and (3) a variety of trajectories to current sexual self-identification. Based on their findings, authors offer insights into the unique lived experiences of behaviorally bisexual men, as well as broader considerations for the study of men’s sexuality.

Authors also explore identity-related information useful for the design of HIV/STI prevention and other sexual health programs directed toward behaviorally bisexual men, which will ideally be variable and flexible in accordance with the wide range of diversity found in this population.

Citation:

Bränström, R. (2017). Minority Stress Factors as Mediators of Sexual Orientation Disparities in Mental Health Treatment: A Longitudinal Population-Based Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, DOI: 10.1136/jech-2016-207943.

Summary:

An increasing body of research shows large mental health disparities between sexual minorities as compared with heterosexual individuals. Earlier studies have found that sexual minorities are between 1.4 and 4 times more likely to have a lifetime history of mental disorder when compared with heterosexuals. The primary aim of this study was to examine mental health treatment disparities between sexual minority individuals and heterosexuals in Sweden using a population sample followed longitudinally. A second aim was to examine if potential sexual orientation differences in mental health could be explained, or partially explained, by exposure to minority stressors (i.e., victimization, threat of violence) and ameliorating factors (i.e., social support). Finally, the author wanted to explore gender, age, country of birth, income, relationship status and level of education as possible effect modifiers of potential disparities.

The Stockholm Public Health Cohort is a prospective study managed by the Stockholm County Council. For this study, the author used data from the 30,730 individuals (18 years and older) recruited in the fall of 2010 that successfully returned a baseline paper-and-pencil mailed questionnaire or self-administered web survey (response rate: 61%). In addition to a question regarding sexual orientation (included in the Appendix), the survey included questions regarding sociodemographic characteristics, health status and other life circumstances. A total of 28,434 (92.5) individuals responded that they identified as heterosexual, 361 (1.2%) as gay or lesbian, and 381 (1.2%) as bisexual.

The author produced descriptive statistics of the participants’ responses by sociodemographics and further generated regression models to examine sexual orientation differences in experiences of victimization or threat of assaults, social support, and mental health outcomes. Negative binomial regressions were used for count variables and logistic regressions for dichotomous outcomes. Only respondents with complete data were analyzed.

In adjusted analyses, gay and lesbian individuals were more likely to receive treatment for anxiety disorders (adjusted ORs (AOR)=3.80; 95% CI 2.54 to 5.69) and to use antidepressant medication (AOR=2.13; 95% CI 1.62 to 2.79); and bisexuals were more likely to receive treatment for mood disorders (AOR=1.58; 95% CI 1.00 to 2.48), anxiety disorders (AOR=3.23; 95% CI 2.22 to 4.72) and substance use disorders (AOR=1.91; 95% CI 1.12 to 3.25), and to use antidepressant medication (AOR=1.91; 95% CI 1.12 to 3.25) when compared with heterosexuals. The largest mental health treatment disparities based on sexual orientation were found among bisexual women, gay men and younger lesbian women. More frequent experiences of victimization/threat of violence and lack of social support could partially explain these disparities.

This study shows a substantially elevated risk of poor mental health among LGB individuals as compared with heterosexuals. Findings support several factors outlined in the minority stress theory in explaining the mechanisms behind these disparities.

Citation:

Eliason, M.J., Radix, A., McElroy, J.A., et al. (2016). The “Something Else” of Sexual Orientation: Measuring Sexual Identities of Older Lesbian and Bisexual Women Using National Health Interview Survey Questions. Women's Health Issues, 26(51):571-580.

Summary:

Measuring sexual orientation accurately and reliably has always been a major challenge for health disparities researchers. In particular, and despite low rates of selection by survey respondents, “not sure” type responses to sexual orientation questions pose challenges for data analysis. Investigators usually exclude data from participants who have chosen not to answer questions, or who state they are not sure about their sexual orientation. In some cases, researchers have decided to include “not sure” responses with a lesbian/bisexual category for analysis running the risk of misclassifying heterosexual people who do not understand the question with LGBT respondents. Other authors have excluded those respondents, thereby losing data.

Unlike other U.S. Population-based surveys that include sexual orientation measures, The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) includes a follow up intended to gain further understanding when respondents indicate their sexual identity is “something else”. (NHIS items are included in the Appendix.)This study explores how well these NHIS questions operated in a health intervention study of lesbian and bisexual women.

Data were drawn from a multisite study funded by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office on Women’s Health called the Healthy Weight Initiative for Lesbian and Bisexual Women. Each of five sites had different interventions for improving health of older lesbian/bisexual women, but had core baseline and posttest survey items and outcome measures in common, including the NHIS sexual identity questions. This study analyzed the baseline survey data to examine the characteristics of women who identified as lesbian, bisexual, or “something else,” and explored what the “something else” response meant.

Of 376 participants, 80% (n= 301) chose “lesbian or gay,” 13% (n=49) selected “bisexual,” 7% (n=25) indicated “something else,” and 1 participant chose “don’t know the answer.” In response to the follow-up question for women who said “something else” or “don’t know,” most (n= 17) indicated that they were “not straight, but identify with another label.” One participant chose “transgender, transsexual, or gender variant,” five chose “You do not use labels to identify yourself,” and three chose “you mean something else.” Lesbian, bisexual, and “something else” groups were compared across demographic and health-related measures. Women who reported their sexual identity as “something else” were younger, more likely to have a disability, more likely to be in a relationship with a male partner, and had lower mental health quality of life than women who reported their sexual identity as lesbian or bisexual.

Respondents who answer “something else” pose challenges to analysis and interpretation of data, but should not be discarded from samples. Instead, they may represent a subset of the community that views sexuality and gender as fluid and dynamic concepts, not to be defined by a single label. Further study of the various subsets of “something else” is warranted, along with reconsideration of the NHIS question options.

Citation:

Elliott, M.N., Kanouse, D.E., Burkhart, Q., et al. (2015). Sexual Minorities in England Have Poorer Health and Worse Health Care Experiences: A National Survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(1):9-16.

Summary:

The health and healthcare of sexual minorities, including gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people, have recently been identified as priority areas for research. Because of the paucity of research using large, representative samples, much of what is known about the health of sexual minorities comes from small samples that may not accurately represent national populations. Relatedly, studies have tended to combine sexual minority groups that may be quite different in their health and experiences with health care.

Authors use data from the 2009/10 English General Practice Patient Survey (GPPS), a large national health survey of health and healthcare experiences that includes a sexual orientation question (included in the Appendix), to study the associations among sexual orientation, sociodemographic characteristics, and health in a large population-based sample. Authors contrast the health and healthcare experiences of sexual minorities (here limited to gay/lesbian and bisexual men and women) with those of heterosexual men and women.

The 2009/10 GPPS was mailed to 5.56 million randomly sampled adults registered with a National Health Service general practice (representing 99 % of England’s adult population). In all, 2,169,718 people responded (39% response rate), including 27,497 people who described themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual.

In their analysis, authors use two measures of health status (fair/poor overall self-rated health and self-reported presence of a longstanding psychological condition), as well as four measures of poor patient experiences (no trust or confidence in the doctor, poor/very poor doctor communication, poor/very poor nurse communication, fairly/very dissatisfied with care overall).

Authors find that sexual minorities were two to three times more likely to report having a longstanding psychological or emotional problem than heterosexual counterparts (age-adjusted for 5.2 % heterosexual, 10.9 % gay, 15.0 % bisexual for men; 6.0 % heterosexual, 12.3 % lesbian and 18.8 % bisexual for women; p< 0.001 for each). Sexual minorities were also more likely to report fair/poor health (adjusted 19.6 % heterosexual, 21.8 % gay, 26.4 % bisexual for men; 20.5 % heterosexual, 24.9 % lesbian and 31.6 % bisexual for women; p<0.001 for each). Adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and health status, sexual minorities were about one and one-half times more likely than heterosexual people to report unfavorable experiences with each of four aspects of primary care. Little of the overall disparity reflected concentration of sexual minorities in low performing practices.

Authors conclude that sexual minorities suffer both poorer health and worse healthcare experiences. Sexual minorities are two to three times more likely than heterosexual respondents to report longstanding psychological or emotional problems, with the differences being greatest for bisexual respondents. Sexual minorities’ experiences of primary health care also tend to be less favorable than those of heterosexual people of the same gender, age, health, and socioeconomic status. Authors propose efforts should be made to recognize the needs and improve the experiences of sexual minorities.

Citation:

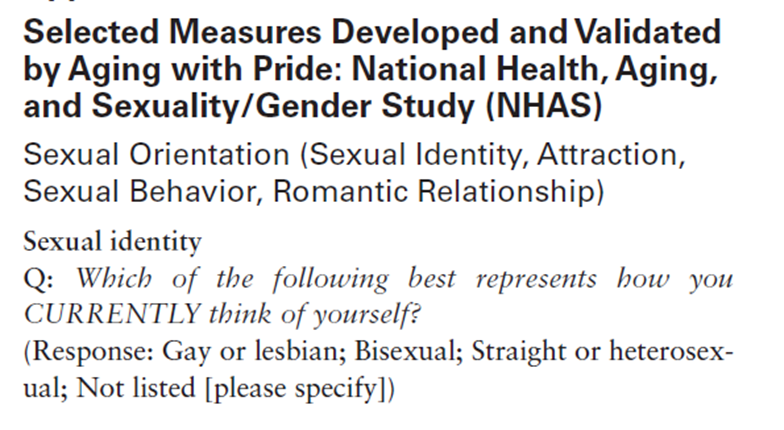

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.I. and Kim, H.J. (2017). The Science of Conducting Research With LGBT Older Adults- An Introduction to Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS). The Gerontologist, 57(S1):S1-S14.

Summary:

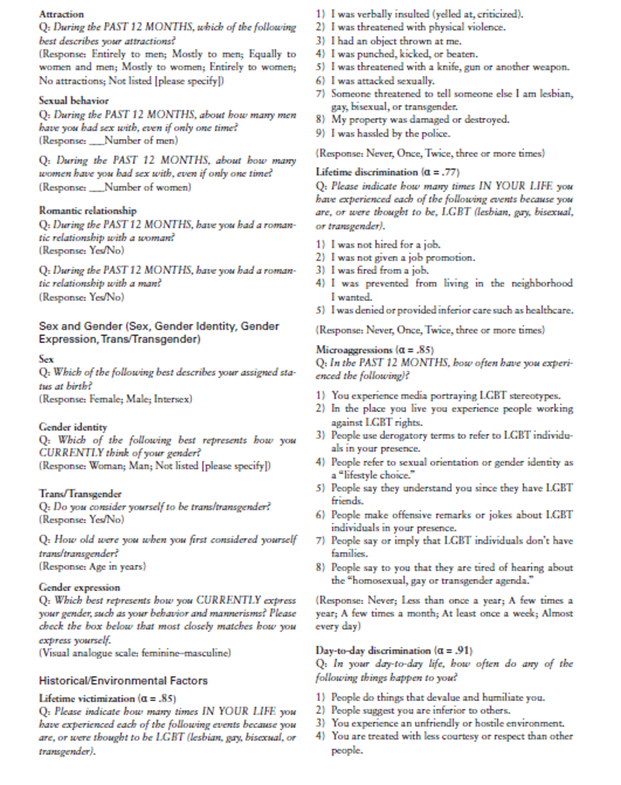

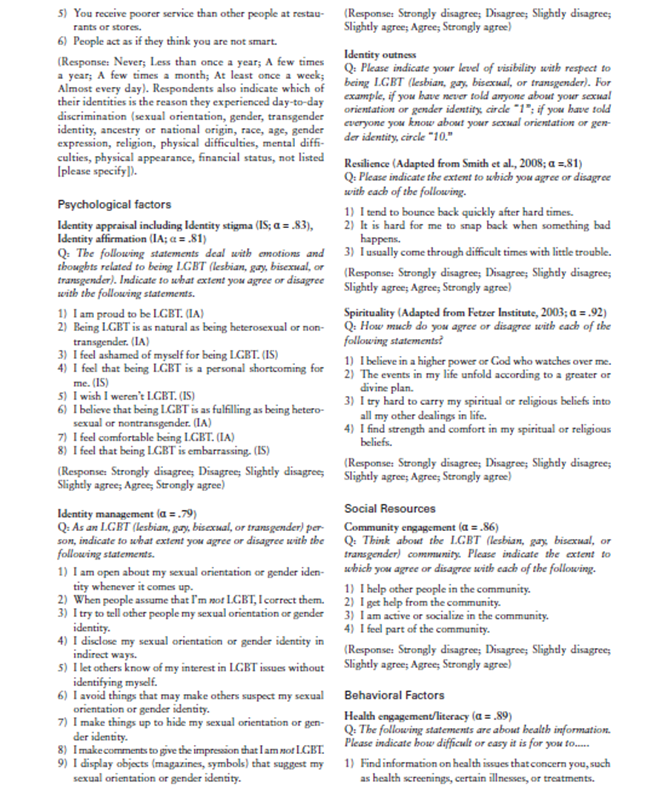

In order to better understand health disparities, aging, and well-being by sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and age, the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Aging funded Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS), the first national longitudinal study of LGBT adults aged 50 and older in the United States. The study aims, derived from the Health Equity Promotion Model (HEPM), include: (a) Foster a better understanding of health and well-being over time among LGBT older adults; (b) Investigate explanatory mechanisms of health equity and inequity, including risk and protective factors common to older adults as well as those distinct to LGBT individuals; and (c) Assess subgroup differences in health and explanatory factors, by age cohort, gender, and race/ethnicity, to identify those at highest risk.

Fredriksen-Goldsen and Kim introduce a supplemental issue of The Gerontologist dedicated to reporting on the 2014 data from Aging with Pride: NHAS. The introduction to the supplement provides foundational information to frame the papers that follow, including a review of population-based findings regarding the size and health status of the LGBT older adult population, a description of the HEPM (the conceptual framework that guides the study), a review of some of the key methodological challenges that exist in conducting research in this hard-to-reach population, and a description of the study’s primary substantive and content areas (which include social positions, historical/environmental, psychological, social, behavioral, biological, health and well-being).

The introduction further describes the articles in the issue, which explore a breadth of topics critical to understanding the challenges, strengths, and needs of a growing and underserved segment of the older adult population. The ten articles in the issue cut across three major themes: risk and protective factors and life course events associated with health and quality of life among LGBT older adults; heterogeneity and subgroup differences in LGBT health and aging; and processes and mechanisms underlying health and quality of life of LGBT older adults. Together these research articles consider the opportunities as well as the constraints in conducting research with hard to-reach populations and the critical theoretical and methodological issues that surface when addressing the increasing sexual and gender diversity in our aging society. The papers develop a foundation of information necessary to guide the development of interventions and practice modalities that can be delivered within community-based agency settings to address the growing needs of LGBT older adults. In future work, authors will employ the longitudinal data to investigate changes in health and well-being over time and to assess temporal relationships between psychological, social, behavioral, and biological processes and health and well-being of LGBT older adults.

The article also includes an Appendix of selected measures developed and validated by NHAS (also included in the Appendix of this document).

Citation:

Galupo, M.P., Lomash, E., and Mitchell, R.C. (2017). “All of My Lovers Fit Into This Scale”: Sexual Minority Individuals’ Responses to Two Novel Measures of Sexual Orientation. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(2):145-165.

Summary:

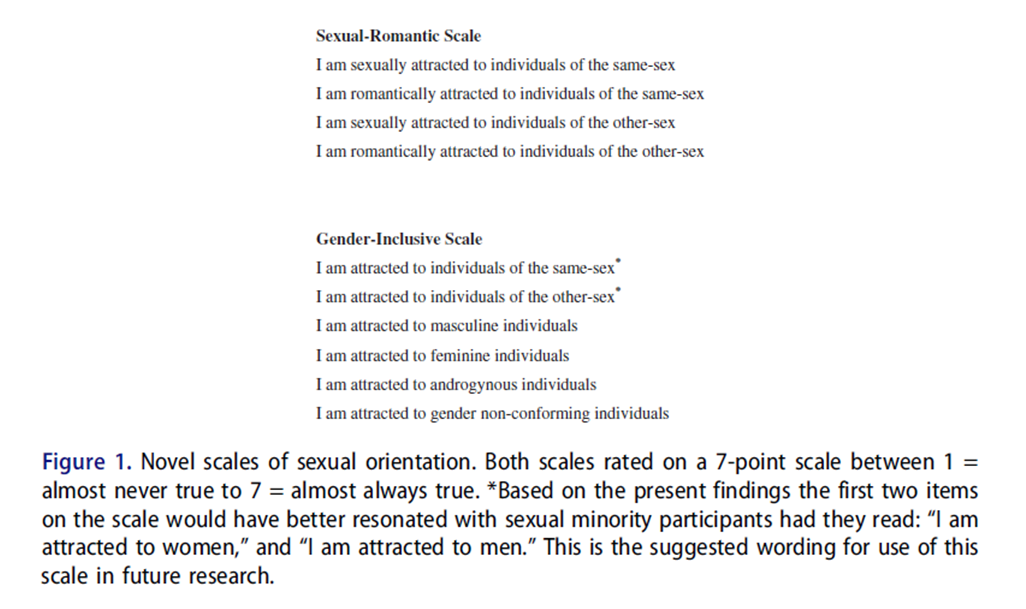

Previous qualitative research on traditional measures of sexual orientation raise concerns regarding how well these scales capture sexual minority individuals’ experience of sexuality. To begin reconceptualizing the measurement of sexual orientation in ways that better represent sexual minority experience, the present research explored sexual minority individuals’ qualitative critiques of two novel sexual orientation scales: the Sexual-Romantic Scale and the Gender- Inclusive Scale. The Sexual-Romantic Scale was designed for the present research to address dual concerns raised by sexual minority participants with regard to traditional measures of sexual orientation. This scale was constructed to measure same-sex and other-sex attraction on independent dimensions rather than on the same continuum, and also to disaggregate the ratings of sexual and romantic components of attraction. The Gender-Inclusive Scale was designed for the present research to address concerns raised by sexual minority participants generally and to specifically address the concerns of plurisexual and transgender individuals. This scale was constructed to measure same-sex and other-sex attraction on independent dimensions rather than on a single continuum, and to also incorporate dimensions of attraction beyond those based on sex. The scales incorporate both traditional components of attraction (same-sex and other-sex) with the intention of capturing more normative conceptualizations of sexuality (monosexual, cisgender). The scales also incorporate novel components of attraction (masculine, feminine, androgynous, and gender non-conforming) to address the concerns of plurisexual and transgender individuals. (Both scales are included in the Appendix.)

Participants represented a convenience sample of 179 individuals who completed an online survey and identified as non-heterosexual. After being presented with each measure, participants were asked to respond to the open-ended prompt: “In what ways did this scale capture, or fail to capture, your sexuality?” Using an inductive method, authors sought to characterize the way in which sexual minority participants responded to two novel scales of sexual orientation. Participant responses varied, including both pointed critiques of the scales and characterizations of sexuality in general. Thematic analysis for each scale was conducted independently. After identifying themes, patterns of responses were analyzed across sexual and gender identity.

Findings indicate that the Sexual-Romantic and Gender-Inclusive scales appear to address some of the concerns raised in previous research regarding the measurement of sexual orientation among sexual minority individuals. In particular, there was a general overall positive reaction to the Gender-Inclusive Scale from sexual minority individuals. Participants, regardless of identity, expressed a sense that this scale captured something the other scales did not. In discussing their findings, the authors agreed that the Gender-Inclusive Scale may represent a promising direction for researchers interested in developing a sexual orientation scale that better resonates with the conceptualization of sexuality as it is experienced by sexual minority individuals across a range of sexual orientation and gender identities.

Citation:

Galupo, M.P., Ramirez, J.L., and Pulice-Farrow, L. (2016): “Regardless of Their Gender”: Descriptions of Sexual Identity among Bisexual, Pansexual, and Queer Identified Individuals. Journal of Bisexuality, DOI: 10.1080/15299716.2016.1228491

Summary:

Despite findings that suggest bisexuality is the largest sexual identification group in the LGBT community, little is known about the range of identities often grouped together under the bisexual umbrella. The present study takes an exploratory approach in understanding the way individuals endorsing three of the most common plurisexual identities—bisexual, pansexual, and queer—describe their sexual identities. Thematic analysis was used to characterize emergent themes from participants’ qualitative descriptions of their sexual identities. Once themes were identified, each participant’s response was coded based on the presence or absence of each theme/subtheme. Chi-square analyses were conducted to examine frequencies of themes across participant self-identification (bisexual, pansexual, queer).

Participants were 172 adults who self-identified as bisexual (n=76), pansexual (n=51), or queer (n=45). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 77 (M=26.18, SD=9.29). The majority (95.35%) of participants resided in the United States and represented all 50 states and Washington, DC. There was limited racial/ethnic diversity within the sample, with 76.7% identifying as White and 23.3% of participants identifying as a racial/ethnic minority. Demographics did not significantly differ across groups with the exception of age and gender identity. Recruitment announcements, including a link to the online survey, were posted to social media sites, online message boards, and e-mailed via LGBT listservs. Some of these resources were geared toward specific sexual minority communities including LGBT people of color, whereas others served the plurisexual community more generally.

The present study focused on information obtained from a demographic section of a larger online study investigating sexual identity and sexual minority experience. A structured sexual orientation question was presented to participants where they chose their primary sexual orientation from discrete options: gay, lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, fluid, queer, asexual, and other. All participants were then asked to respond to the following prompt via free response: “Please describe how you define your sexuality.” The present analysis focuses on the responses from participants who self-identified as bisexual, pansexual, and queer.

Qualitative free responses were analyzed via thematic analysis. Four major themes were identified and found relevant to all three identity groups: (1) labeling sexual identity, (2) distinctions of attraction, (3) explicit use of binary/nonbinary language, and (4) identity transcendence. Each of the four major themes was further composed of subthemes, and one minor theme of questioning also emerged. Patterns of responses across sexual identity were analyzed via chi-square analyses. Individuals who self-identified as bisexual, pansexual, and queer demonstrated similarities and differences in the way they described their sexual identities. Of the 15 emergent subthemes, six differed in frequency across sexual identity.

In their discussion, authors focus on elucidating when grouping bisexual, pansexual, and queer identities together may prove useful, and when it may further distort an understanding of the range of plurisexual experience.

Citation:

Gates, G. (January 11, 2017). In US, More Adults Identifying as LGBT. Available at: http://www.gallup.com/poll/201731/lgbt-identification-rises.aspx. Accessed on March 2, 2017.

Summary:

The portion of American adults identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT) increased to 4.1% in 2016 from 3.5% in 2012. These figures, drawn from the largest representative sample of LGBT Americans collected in the U.S., imply that more than an estimated 10 million adults now identify as LGBT in the U.S. today, approximately 1.75 million more compared with 2012.

These results are based on telephone interviews with a random sample of 1,626,773 U.S. adults, aged 18 and older, living in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, collected from June 1, 2012, through Dec. 30, 2016, as part of the Gallup Daily tracking survey and the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index survey. The data include 49,311 respondents who said "yes" when asked, "Do you, personally, identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender?" (This question is also included in the Appendix.)

Millennials, defined in this report as those born between 1980 and 1998, drive virtually all of the increases observed in overall LGBT self-identification. The portion of that generation identifying as LGBT increased from 5.8% in 2012 to 7.3% in 2016. LGBT identification remained relatively stable over the five-year period at 3.2% among Generation X and declined slightly from 2.7% to 2.4% among baby boomers and from 1.8% to 1.4% among traditionalists. The author speculates that millennials are the first generation in the U.S. to grow up in an environment where social acceptance of the LGBT community markedly increased. This may be an important factor in explaining their greater willingness to identify as LGBT. They may not have experienced the levels of discrimination and stigma experienced by their older counterparts.

Additionally, LGBT identification increases are more pronounced in women than in men. In 2012, 3.5% of women identified as LGBT, comparable to the 3.4% of men. By 2016, LGBT identification in women increased to 4.4% compared with 3.7% among men. These changes mean that the portion of women among LGBT-identified adults rose slightly from 52% to 55%. Among racial and ethnic minorities, the largest increases since 2012 in LGBT identification occurred among Asians (3.5% to 4.9%) and Hispanics (4.3% to 5.4%). Among whites, the comparable figures are 3.2% to 3.6%. Black Americans showed only a slight increase from 4.4% to 4.6%, and among "other" racial and ethnic groups, the increase was from 6.0% to 6.3%. The relatively larger increases in LGBT identification among racial and ethnic groups other than white, non-Hispanics mean that these racial and ethnic minorities now account for 40% of LGBT-identified adults compared with 33% in 2012. In the general population, 33% of adults identify their race or ethnicity as other than white, non-Hispanic, an increase from 28% in 2012.

The variations in increases in LGBT identification by race and ethnicity are likely affected by differences in the age composition of the groups. According to the Gallup data, the average age of Asian adults in the U.S. is 35, the youngest among the race/ethnicity groupings. Average age is 39 among Hispanics, 44 among blacks, 51 among white adults, and 44 among "other" racial and ethnic groups. Given the big changes in LGBT identification among millennials, the youngest generation, it's not surprising that younger racial and ethnic groups report larger LGBT identification increases.

Citation:

Lombardi, E. and Banik, A. (2016). The Utility of the Two-Step Gender Measure Within Trans and Cis Populations. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13(3):288–296.

Summary:

There has been much discussion on the need for greater research on the health of transgender, transsexual, and gender nonconforming (trans) people in order to address significant disparities experienced by these populations in terms of health care access and outcomes. The lack of research regarding trans issues is partly due to the lack of inclusion within population level studies, and a major reason being the lack of measures that can effectively differentiate between different gender identities.

This study is focused on understanding how trans and cis individuals interpret each of the questions within a two question measure to assess transgender and cisgender status. Both groups will likely vary how they experience and interpret sex and gender. Trans populations can vary widely in regards to their gender identities. At the same time, cis populations will likely have a very traditional belief of sex and gender. We have quantitative studies showing that trans and cis groups will answer the questions, but what is not known is either groups understanding of the measure. The current study addresses that gap. As this study wanted to assess the effectiveness of the two-step measure for general population studies (rather than LGBT or primarily trans populations), the number of response categories for the question asking about people’s sex or gender was limited to only Male, Female, and Other (specify). The percentage of trans people of all categories to be found within a general population is likely to be small and will create problems during quantitative analysis (e.g., statistical power, how to combine responses). This study decided to force a choice between male, female, and “other (specify)” category in order to differentiate between binary and nonbinary (genderqueer, agender, etc.) identified individuals. This is seen as the simplest way to differentiate between trans and cis, male and female, and binary and nonbinary populations for studies targeting general populations. (Items are included in the Appendix.)

The study recruited a convenience sample of 50 people (25 trans and 25 cis) from the general population of Cleveland and Akron, OH. The study used cognitive interviewing methods with scripted, semi-structured and spontaneous probes when appropriate. Participants were asked to read questions out-loud, answer the questions, and explain why they answered the way they did. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed prior to analysis within a dedicated qualitative research program (NVIVO). The study was able to attain theoretical saturation with the 50 cases examined.

This investigation found that the two-step gender status measure were understood by a sample of cis men and women, and its results were what were expected for both cis and trans populations. Based on the study’s findings, it will be important to refer to people’s gender or gender identity rather than sex. While the cis participants did not note a significant difference between the two, the trans participants did and saw gender as referring to their identity and sex as their physiology. The results support the consensus that is growing regarding the use of the two-step gender measure within population studies within the US Health surveillance system, but issues remain regarding the categories to offer in order to best capture diverse gender identities for the purpose of quantitative studies.

Citation:

Swanbrow Becker, M.A., Nemeth Roberts, S.F., Ritts, S.M., Branagan, W.T., Warner, A.R., Clark, S.L. (2017). Supporting Transgender College Students: Implications for Clinical Intervention and Campus Prevention. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, DOI: 10.1080/87568225.2016.1253441.

Summary:

College students identifying as transgender face complex challenges as they attempt to negotiate a transition in their gender identity in addition to adjusting to adulthood, college life, and new social supports. They likely experience the college environment differently from those who identify as cisgender and heteronormative, and so may feel excluded from and marginalized by the dominant cultures and even from the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Questioning (LGBQ) community with whom they are so often associated. Efforts to help transgender students thrive on campus are hampered by the lack of understanding of their multiple intersecting identities, their experiences coping during stressful times, their unique developmental tasks in managing bodily changes and learning new gender roles, and their perceived access to social, academic, and mental health supports. This article seeks to address whether transgender students differ in the level of distress experienced during a stressful time as compared to their cisgender LGBQ and heterosexual peers and what factors impact any differences.

In order to better understand how college students cope with stress, The National Research Consortium of Counseling Centers in Higher Education distributed an electronic survey to a random selection of 100,493 college students across 73 participating institutions. Students completed the 79-itemsurvey in the Spring of 2011 and responses were collected anonymously. The survey yielded 26,292 respondents, a 26% response rate. Subjects were grouped during analysis by their self-reported gender identification. Participants were then placed into one of three groups: students who identified as transgender, students who identified as cisgender and LGBQ, and students who identified as cisgender and heterosexual. The transgender group was composed of 47 students (0.2%). (Gender identification and sexual orientation items are included in the Appendix.)

A chi-square analysis revealed that transgender college students have survived a significantly greater rate of trauma than LGBQ cisgender and heterosexual cisgender students. The prevalence of a trauma history was also significantly greater in LGBQ college students as compared to heterosexual students. Furthermore, while transgender students endorsed some of the same stressors as their cisgender peers that seem typical of college students, such as academics, life transition, and financial problems, they also reported more stressors that appear related to their special circumstances, such as gender identity concerns, physical health problems, discrimination, and sexual orientation concerns. In addition to a more extensive trauma history and increased stressors, the transgender group also reported a higher prevalence of suicidal thoughts and attempts across their lifetime and during the stressful period than the cisgender LGBQ and heterosexual cisgender groups.

The results from this study begin to elucidate several factors related to the help seeking patterns of transgender college students and how they may differ from heterosexual cisgender and LGBQ cisgender students.

Appendix: Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Items

Baldwin, A., Dodge, B., Schick, V., et al. (2015). Sexual Self-Identification Among Behaviorally Bisexual Men in the Midwestern United States. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(7):2015-2026.

Bränström, R. (2017). Minority Stress Factors as Mediators of Sexual Orientation Disparities in Mental Health Treatment: A Longitudinal Population-Based Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, DOI: 10.1136/jech-2016-207943.

Sexual Orientation What is your sexual orientation? Heterosexual Bisexual Gay/lesbian Not sure

|

Eliason, M.J., Radix, A., McElroy, J.A., et al. (2016). The “Something Else” of Sexual Orientation: Measuring Sexual Identities of Older Lesbian and Bisexual Women Using National Health Interview Survey Questions. Women's Health Issues, 26(51):571-580

Sexual Orientation Which of the following best represents how you think of yourself? Lesbian or gay; Straight, that is, not lesbian or gay; Bisexual; Something else; I don’t know the answer.

If you answered “something else”; What do you mean by something else? You are not straight, but identify with another label such queer, trisexual, omnisexual or pansexual; You are transgender, transsexual or gender variant; You have not figured out or are in the process of figuring out your sexuality; You do not think of yourself as having sexuality; You do not use labels to identify yourself; You mean something else.

|

Elliott, M.N., Kanouse, D.E., Burkhart, Q., et al. (2015). Sexual Minorities in England Have Poorer Health and Worse Health Care Experiences: A National Survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(1):9-16.

Sexual Orientation Which of the following best describes how you think of yourself? Heterosexual/straight Gay/lesbian Bisexual Other I would prefer not to say

|

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.I. and Kim, H.J. (2017). The Science of Conducting Research With LGBT Older Adults- An Introduction to Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS). The Gerontologist, 57(S1):S1-S14.

Galupo, M.P., Lomash, E., and Mitchell, R.C. (2017). “All of My Lovers Fit Into This Scale”: Sexual Minority Individuals’ Responses to Two Novel Measures of Sexual Orientation. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(2):145-165.

Gates, G. (January 11, 2017). In US, More Adults Identifying as LGBT. Available at: http://www.gallup.com/poll/201731/lgbt-identification-rises.aspx. Accessed on March 2, 2017.

Sexual Orientation Do you, personally, identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender? Yes No

|

Lombardi, E. and Banik, A. (2016). The Utility of the Two-Step Gender Measure Within Trans and Cis Populations. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13(3):288–296.

Two-Step Gender Status Measures 1. What is your sex or gender? (Check ALL that apply) Male Female Other: Please specify:

2. What sex were you assigned at birth? (Check one) Male Female Unknown or Question Not Asked Decline to State

|

Swanbrow Becker, M.A., Nemeth Roberts, S.F., Ritts, S.M., Branagan, W.T., Warner, A.R., Clark, S.L. (2017). Supporting Transgender College Students: Implications for Clinical Intervention and Campus Prevention. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, DOI: 10.1080/87568225.2016.1253441.

Gender Identification How do you identify? Male Female Transgender

|

Sexual Orientation How would you describe your sexual orientation? Bisexual Gay or lesbian Heterosexual Questioning Other

|

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| File Title | Report Template Blue |

| Author | Microsoft Office User |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-21 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy