SOII Edits Test Report

SOII_Edits_test_2012_finalreport_draft.docx

Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses

SOII Edits Test Report

OMB: 1220-0045

October 9, 2012

MEMORANDUM FOR: Elizabeth Rogers

FROM: Scott Fricker, Office of Survey Methods Research

SUBJECT: Results of the SOII Edits Usability Test

Introduction and Purpose

Previous evaluations (e.g., expert reviews, respondent debriefings, usability tests) of the Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illness (SOII) web-based instrument on the Internet Data Collection Facility (IDCF) have found that respondents may:

Have difficulty understanding what they are supposed to enter in the “Total hours worked by all employees” field and in using the optional worksheet that accompanies this field (Section 1: Establishment Information).

Be confused and/or frustrated by the way information about Average Hours Worked per Employee is derived and presented on the screen (Section 1: Establishment Information).

Miss or have negative reactions to error message that appear on the detailed “Cases with Days Away From Work” reporting page.

The primary purpose of the present study was to explore the impact of alternative designs for displaying edit messages on the usability of the Establishment Information page (Section 1) and the detailed Case reporting page of the SOII instrument. In addition, the program office was interested in participant reactions to the Worksheet for Estimating Total Hours Worked by All Employees. These pages were evaluated through common usability metrics (e.g., task success rates, time to completion, etc.), eye-tracking analyses, and respondent think-alouds and debriefings, in an attempt to identify any confusion or problems participants encounter as they complete the web survey. The main body of the report describes the test methodology and contains detailed information about problems that arose during testing on the individual IDCF web pages. The recommendations based on the results of this study are presented in Section 4.0, beginning on page 14.

Methodology

2.1 Test Procedures

The usability test sessions were conducted in the Office of Survey Methods Research (OSMR) usability lab from August 7 – August 23, 2012. Nineteen participants were administered a web-based SOII instrument designed by program office staff to replicate the look and feel and functionality of the SOII IDCF instrument. Eye-tracking data were captured for each participant, and the test facilitator observed users’ interactions with the instrument and the associated eye-tracking data from a separate monitor located in an adjacent room. Each test session was recorded and two sessions were observed in person by a member of the SOII-IDCF team. A high-level summary of the key findings from this study was delivered to the program office on August 23, 2012.

Prior to their test date, participants were sent hard copies of a blank 2011 SOII form and the OSHA Form 300 so that they would be familiar with the general SOII reporting requirements and format. Individuals were notified in advance that the BLS was in the process of redesigning its SOII reporting website, and that they would be helping to evaluate the proposed changes. They were told that this was a test of the site, not of them, and that they would not be asked to report data for an actual establishment.

During the test session, participants were asked to complete a series of tasks. Prior to each task, they read a brief passage describing the task objective and information about a hypothetical company that would be necessary to complete the task. After verifying that the participant understood the task objective and material, the test facilitator launched the appropriate page of the SOII instrument and the participant attempted to complete the task. Participants were encouraged but not required to think-aloud during their task performance and were provided with hints or feedback only when they asked for help, or when it was apparent that they were stuck (e.g., after more than 1 minute of inactivity, or when there were explicit expressions of confusion or frustration). If a participant did not recover from an error or failed to complete a task within a reasonable amount of time (varied by task), the test monitor intervened and/or moved on to the next task. At the end of the test session, the facilitator conducted a debriefing to collect any additional comments from participants (see Appendix A for study protocol).

Participants

Twenty individuals from the local DC metro area were recruited to participate in this study. During the recruitment process, study candidates were asked a series of screener questions designed to ensure that all participants were sufficiently proficient with using the computer and Internet, and that the resulting non-probability sample was diverse with respect to age, education, and employment. One scheduled participant failed to appear for their scheduled appointment; 19 participants contributed to the findings in this report. Table 1 provides more detailed information about the composition of the study sample.

Table 1: Participant Demographics and Computer Experience

Age |

|

18-35 |

|

36 – 64 |

|

Mean |

|

Education |

|

HS diploma/some college |

|

College degree |

|

Post-graduate degree |

|

Employment Status |

|

Unemployed |

|

Employed |

|

Use of the Internet in typical week? |

|

Less than 5 hours |

|

6 - 10 hours |

|

More than 11 hours |

|

Web purchase in last 6 months? |

|

Never |

|

Less than once per month |

|

Monthly |

|

Weekly or more |

|

Online web form, surveys, or registration? |

|

Never |

|

Less than once per month |

|

Monthly |

|

Weekly or more |

|

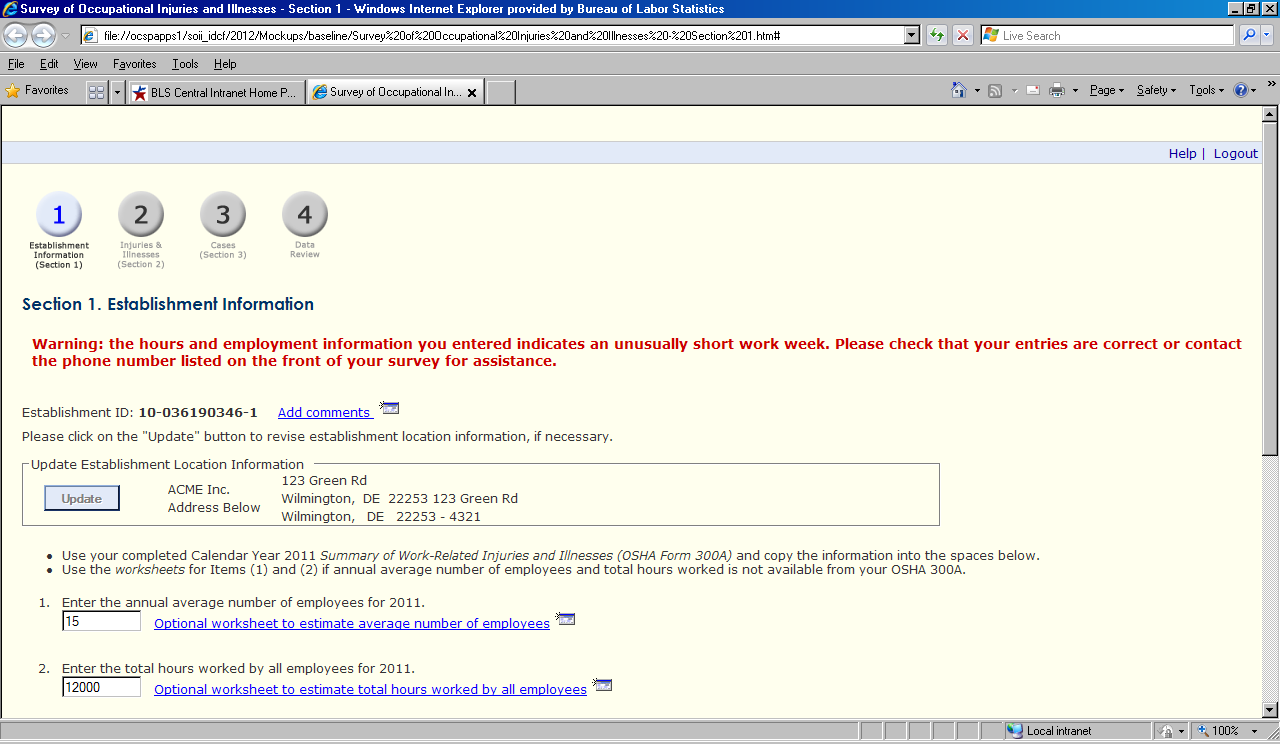

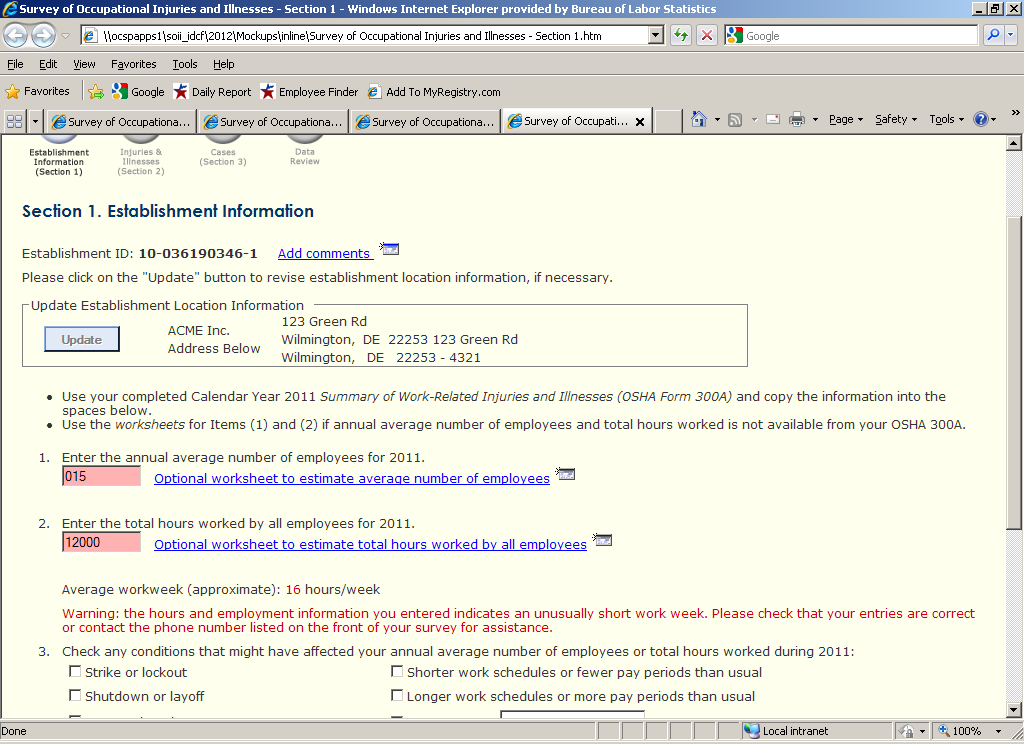

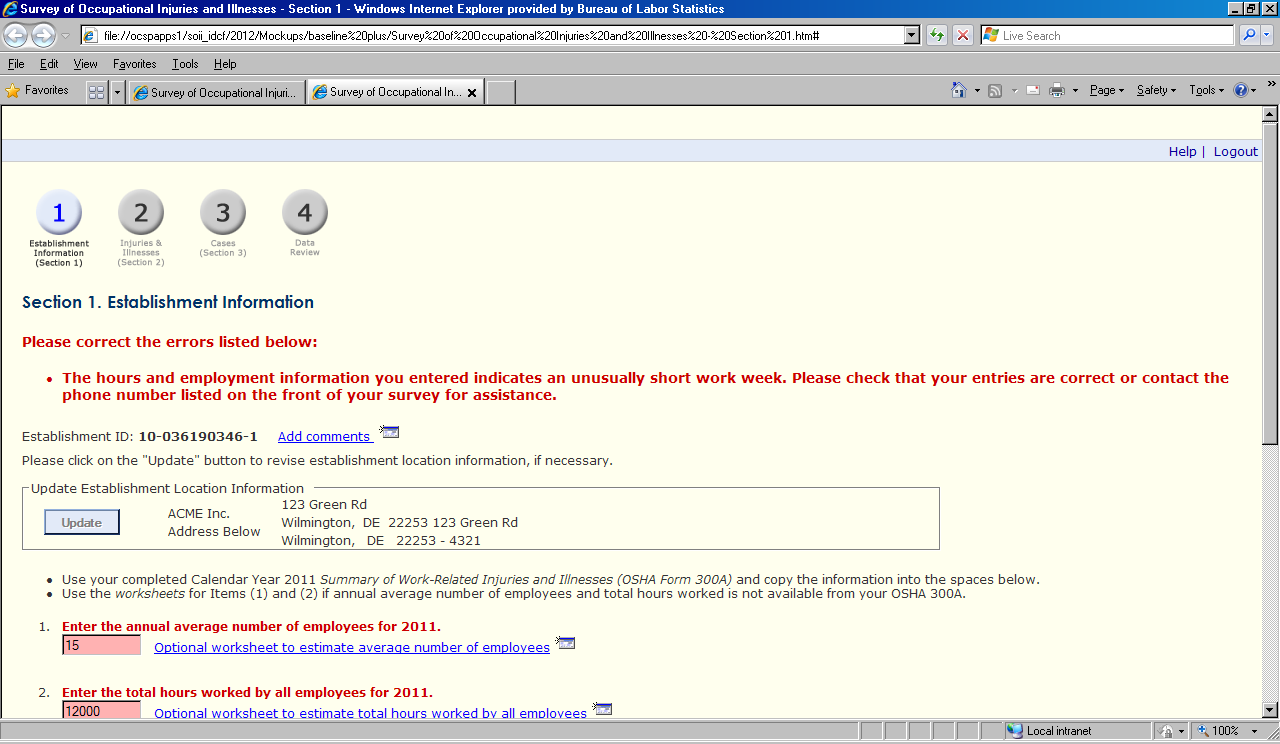

2.3 Treatments

The SOII program office created three versions of a web-based SOII instrument outside IDCF; the three versions differed only in the timing and placement of edit messages. In one version, the messages appeared as red text at the top of the page only after the user had completed all the items on the page and clicked the “Save & Continue” button to proceed to the next section of the instrument. This approach mirrors the way in which edit messages are presented in the current SOII IDCF instrument, and is therefore referred to as the ‘Baseline’ version throughout the remainder of this report. The second version was similar to the Baseline condition – it used deferred messages which appeared in red text at the top of the page – but in addition, the fields that triggered the edits also were highlighted in red. This is referred to as the ‘Baseline Plus’ condition. The final version presented the edit messages to users immediately after an edit was triggered. In this “Inline” condition, an edit message (again, in red) appeared next to the field where the edit failure occurred, and the entire field was highlighted in red, as well; there were no top-of-the-page edit messages in this condition. The Inline edit messages and highlighted fields persisted on the page until the user confirmed or corrected the input. Appendix B provides example screenshots of the three versions as they appeared on the Section 1 and Case pages, respectively.

2.4 Test Objectives

The study was designed to answer the following questions about the SOII instrument:

Which of the edit message formats is most effective in directing users’ visual attention to the problem field?

Is one of the edit message formats more effective than the others in terms of respondents addressing/fixing the triggered edit?

Which edit message format do users prefer and why?

Do users notice the Average Hours Worked (AHW) information in Section 1?

Is this impacted by the format of that field and/or the edit message format?

If users do notice it, do they comprehend it as intended?

What mistakes (if any) do users make and what reactions do they have when interacting with the Total Hours Worksheet?

2.5 Tasks and Edit Triggers

Participants were asked to complete four independent tasks that were intended to address the test objectives.

Task 1 Complete Establishment Information page (Section 1)

Participants were provided with information about the ‘average number of employees’ in the company and the ‘total hours worked by all employees,’ and were asked to use the SOII instrument to enter these data.

Task 2 Complete Establishment Information page + Total Hours Worksheet (Section 1)

Participants were provided with new information about the company’s ‘average number of employees’ and the ‘total hours worked by all employees,’ and were asked to use the SOII instrument to enter these data. However, this task required participants to calculate the ‘total hours worked’ value because the company employed some full-time and some part-time workers. Participants were told that they should try to find and use the ‘worksheet to estimate the total hours worked by all employees.’

Task 3 Complete Case with Days Away From Work page - 1

Participants were told that the company had two cases with injuries that resulted in days away from work, and were asked to use the Case page to enter information for the first case. They were told that they could make up answers to all of the required fields in the form.

Task 4 Complete Case with Days Away From Work page - 2

Participants were asked to enter in information about the second case resulting in days away from work, and again were told that they could make up their answers for the required fields. The only difference between Task 3 and Task 4 was in how the edit messages were displayed (see below for more details).

Because the primary objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of edit message formatting, and there was no way to control whether and where edits would be spontaneously triggered with a small sample of non-SOII respondents, it was necessary to incorporate forced edits on every task. Forced edits are edits that are triggered automatically for a particular field or action, regardless of the user’s input. A common example of a forced edit is the prompt that users receive in MS Windows applications when attempting to delete a file (e.g., “Are you sure you want to delete this file?”).

In this study, forced edits were triggered for the ‘Average hours worked” value in Section 1, and for the ‘Job Title” and “Employee’s Age” fields on the Cases with Days Away from Work page. On the Section 1 page, the edit message users received read: “Warning: the hours and employment information you entered indicates an unusually short work week. Please check that your entries are correct or contact the phone number listed on the front of your survey for assistance.” This edit was triggered by design for each participant because the fictional establishment for which they were reporting was a seasonal business (a ski lodge), and so the resulting annual hours were lower than for a typical year-round SOII establishment. On the Cases page, the forced edits simply asked participants to re-enter the job title and employee’s age. Although the edits on both pages were highly artificial – that is, they were a product of what participants were told to enter in Section 1, and required users to re-type perfectly valid responses in two fields on the Cases page – they offered a way to assess whether users noticed the edit messages, and if so, when they did, and what actions users took (if any) as a result.

2.6 Evaluation Measures

To address the test objectives, a number of participant actions and behaviors were observed and logged. These included:

Awareness of the edit message - whether or not the participant noticed edit message. In most cases, determination was based on eye-tracking data. In some instances, however, eye-tracking data was poor or not-available. When this occurred, an attempt was made to use respondents’ actions (e.g., mouse movements) and verbal reports (during and after the task) to determine if the edit message had been seen. If the eye-tracking data or respondent behaviors were inconclusive, these cases were excluded from analyses related to this metric.

Time to first fixation - the eye tracker collected data on the time it took participants to notice the edit messages. Time to first fixation refers to the elapsed time between the moment the page displaying the edit message loaded and the first time the user looked at (fixated on) the edit message text and/or the field that triggered the edit. This metric is reported only for those participants who saw the edit messages and for whom eye-tracking data were available.

Resolution of edits – whether or not the participant attempted to act on the edit message, and if so, the outcome of those actions (successful resolution or not)

Observation and open-ended comments- participants’ verbal comments or displays of unusual actions during task performance.

Debriefing session comments – participants’ responses to questions asked after all study tasks had been attempted, in an effort to clarify or elaborate on actions and comments made during test performance, and to assess respondents’ preferences regarding instrument design.

Results

This section presents findings on the effectiveness of the different edit formats, and summarizes interviewer observations and respondent comments pertaining to the usability of the three SOII instrument pages evaluated in this study (i.e., Section 1 - Establishment Information; Worksheet for Estimating Total Hours Worked by All Employees; and, Case with Days Away from Work). Participant data were combined from Tasks 1 and 2 (Section 1 page tasks), and Tasks 3 and 4 (Case page tasks), respectively. This was done to ease interpretation of the findings and increase the effective sample size for analyses, and only after initial examinations revealed a very similar pattern of results for tasks by page.

Impact of Edits on Section 1 Page

Table 2 displays the key study outcome measures of the impact of edit formatting on the Section 1 page. The first row in the table indicates the number of cases that were ‘eligible’ to be included in these analyses (numerator) out of the total number of cases (denominator). Here, the denominator reflects participants’ interactions with the Section 1 page across the two tasks. Since this analysis collapses across the two tasks that involved the Section 1 page, the denominator is equal to twice the number of participants in a condition (e.g., the Baseline condition had 7 participants in Task 1 and Task 2, for a total of 14 cases). In order to be considered ‘eligible’ for these analyses, (1) the SOII instrument must have presented an edit, and (2) there needed to be sufficient data to determine whether the participant saw the edit. The number of eligible cases on Tasks 1 and 2 was substantially lower than the total number of possible cases, particularly for the Baseline and Inline conditions. This stemmed in part from the absence of participant eye-tracking data during the test session (i.e., some participants did not track well at all, others simply had intermittent tracking). The primary reason for low eligibility rates across these two tasks, however, was that at the start of the study edits on the Section 1 page initially were not triggered automatically, or were set to time out after two seconds. SOII program staff corrected these implementation issues after the first few test sessions, but they somewhat reduced the usable sample size for the analyses presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Participant Performance on the Establishment Information Page (Section 1), Collapsing Across Tasks 1 and 2

|

Condition |

||

Baseline |

Inline |

Baseline Plus |

|

Eligible |

8/14 |

6/12 |

11/12 |

|

|

|

|

Notice edit text? |

7/8 |

5/6 |

11/11 |

Time to 1st fixation (sec) - text |

0.8 |

5.7 |

0.6 |

Read text? |

7/7 |

4/6 |

11/11 |

|

|

|

|

Notice field after edit? |

8/8 |

6/6 |

8/9 |

Time to 1st fixation (sec) – field |

2.4 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

|

|

|

|

Attempt to fix field? |

3/8 |

3/6 |

6/11 |

|

|

|

|

Average Hours Worked (AHW) Element |

|

|

|

Fixate on AHW before edit? |

11/14 |

7/12 |

6/12 |

Fixate on AHW after edit? |

5/8 |

3/6 |

6/11 |

Click on AHW? |

5/22 |

0/18 |

0/23 |

The next three rows in Table 2 show the extent to which participants noticed the edit message text, the time it took them to first fixate on that text, and whether participants actually read the message. As can be seen, there was little difference between conditions in participants’ likelihood of noticing the text, but participants in the Inline condition took about 5 seconds longer to do so than participants in either the Baseline or Baseline Plus condition. Inline participants also were somewhat less likely than those in the other two conditions to read the text of the edit message. As the next two rows in the table show, however, this pattern of results was reversed for the time it took participants to locate (fixate on) the fields that triggered the edit. Although almost all participants in the three conditions did eventually look at the relevant fields on the Section 1 page, those in the Inline condition did so extremely quickly (0.2 seconds) and consistently faster than participants in the Baseline or Baseline Plus conditions.

The objective of any edit is to effectively communicate some desired action on the part of the respondent – e.g., directing them to review, confirm, or correct input. The Section 1 edit message asked participants to ‘check to make sure that their entries’ were correct. The results presented in the preceding paragraph indicate that nearly all participants did in fact review the appropriate information on the page. But many of the participants who saw the edit expressed confusion or appeared unsure how to proceed, and about half attempted to fix their entries in some way (e.g., by retyping them, adding commas to the hours-worked value, etc.). This result largely was an artifact of the testing protocol. Participants were given the fictional company information to report and often were surprised when this ultimately resulted in an edit message that asked them to verify that the information was correct. In their think-aloud comments during test performance, approximately one third of the participants in each condition commented that they were not going to change their answers because they felt they had entered in the appropriate values based on the task description.

Finally, we examined the Average Hours Worked (AHW) element on the Section 1 page. In the production SOII instrument, one of the Section 1 edits is a range edit based on the derived average hours worked value (i.e., dividing the ‘total hours worked by all employees’ entry by the ‘annual number of employees’ entry). The inclusion of the AHW element in Section 1 is intended to help respondents identify potential errors in the values they entered in the ‘total hours’ or ‘number of employees’ fields. The AHW element is a part of the basic SOII-IDCF Section 1 page. Initially, its value is blank (i.e., an empty grayed-out box displays next to the AHW field; see Figure 1 below); when respondents complete the ‘total hours’ and ‘number of employees’ items, the AHW field dynamically displays the value for the calculated average hours worked per employee for the establishment. Respondents cannot directly enter or alter the values that appear in the AHW box.

Figure 1. Format of SOII-IDCF Average Hours Worked Element

In this study, the implementation of the AHW element differed slightly across the three test conditions. All three conditions dynamically displayed the AHW value as soon as the ‘total number of employees’ and ‘total hours’ information had been entered, but the formatting (layout) of the field was varied. The Baseline condition used the format shown in Figure 1. The Baseline Plus and Inline conditions used the format shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Format of Average Hours Worked Element in Baseline Plus and Inline Conditions

The last three rows of Table 2 show participants’ visual and behavioral interactions with the Average Hours Worked (AHW) element on the Section 1 page. The format of this element had a clear impact on participants’ attention. Nearly 80 percent of Baseline participants (11 out of 14) fixated on this element prior to triggering and displaying the edit, but only about half of the participants in the other two conditions did so (6 of 12 Baseline Plus participants; 7 or 12 Inline participants). The effects of formatting are evident as well in the number of instances where participants attempted to click on the AHW element; this occurred in 5 instances in the Baseline condition but did not occur in the other two study conditions.

Only about half the participants in each condition looked at the AHW element after the edit message displayed. This may be explained in part by the fact that in the Baseline and Baseline Plus conditions, the AHW element appeared ‘below the fold’ of the Section 1 page (i.e., participants had to scroll down the page to see it; see Appendix A). In the Inline condition, the AHW element was ‘sandwiched’ between the red, highlighted ‘average number of employees’ and ‘total hours’ entry fields and the red edit message text itself. This formatting appears to have competed for participants’ attention, causing some in the Inline condition not to look at the AHW information.

Participant think-aloud comments indicated that most people understood that something had “gone wrong” when they noticed the edit message on the Section 1 page, but they seldom associated this with the AHW element, choosing instead to focus on the fields in which they had entered information. However, one participant in the Baseline condition who initially noticed the AHW element prior to triggering the edit, said upon seeing the subsequent edit message, “Oh, I guess that’s because I didn’t fill out that [AHW] box.” During the post-test debriefing, 7 participants could not accurately articulate how the AHW value was derived. Of the remaining participants who understood what the AHW represented, 7 thought this element was ‘very useful’ or ‘somewhat useful,’ and 5 said that this element was ‘not very useful’ or ‘not at all useful.’ There were no differences in interpretation or perceived usefulness between conditions, though two people in the Baseline condition did say that the gray box looked like a text-entry box and should be reformatted to avoid confusing respondents.

Other Usability Issues/Comments on Main Section 1 Page

Following Tasks 1 and 2, participants were asked if there were any features of the Section 1 page (wording, layout, functionality) that they found confusing or which could be improved. Several participants said that they thought the page was well-designed or noted specific features that they liked (e.g., “…it was neat and clean.” “..the buttons and formatting break up the sections nicely – it’s good on your eyes.” “I like the big ‘Continue’ button – I know where I’m going.”). But more than half of the participants (n=11) offered some form of critique of or suggested improvements for the page. The most common comments were that (1) the page looked too crowded (e.g., “It was overwhelming. The questions are bunched together.” “The first question is too far down, there’s so much text before you even see it.” “It’s super crowded at the top.”), (2) the font was too small and/or the color scheme was washed out (e.g., “The page is so ‘black and white’ – so serious.” “I had a hard time reading the tiny text.” “This is one dull page.”), and (3) the ‘0’s that initially populate the ‘annual number of employees’ and ‘total hours’ fields should (but do not) disappear when the user clicks in the field.

Usability Issues/Comments on Total Hours Worksheet

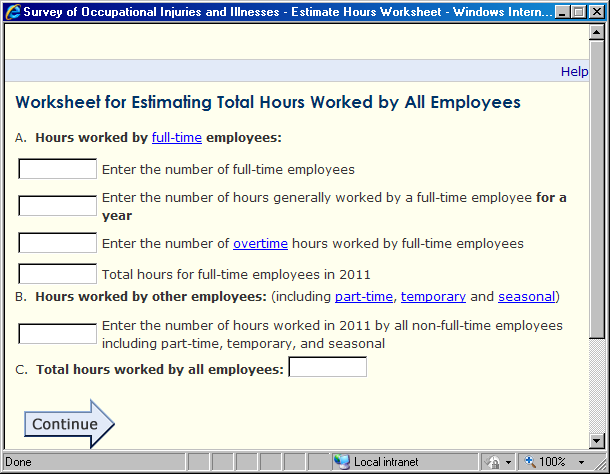

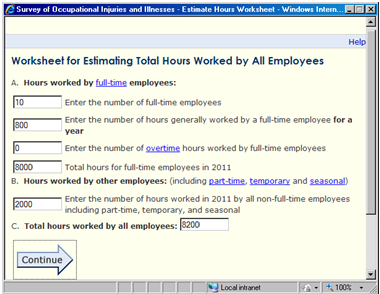

Task 2 asked participants to find and use the ‘optional worksheet to estimate total hours worked by all employees.’ The link to the worksheet appeared next to the ‘total hours worked’ field on the Section 1 page; Figure 2 provides a screenshot of the worksheet.

Figure 2. Screenshot of the Total Hours Worksheet

Users are asked the number of hours

generally worked by FT employees for a year

These two fields are auto-filled based

on users’ preceding entries

The written task description participants were given in Task 2 indicated that the company for which they were responding operated for only 10 pay periods during the year, and employed 10 full-time workers (40 hours/week; 80 hours/pay period) with no overtime, and 5 part-time employees (20 hours/week; 40 hours/pay period). Figure 3 shows an example of a correctly completed worksheet. Participants in all three study conditions saw this identical worksheet, so their data were summed across conditions. Table 3 provides a summary of participant performance and comments on the worksheet.

Figure 3. Screenshot of the Correctly Completed Worksheet

Table 3. Performance and Comments on the Worksheet for Estimating Total Hours Worked by All Employees

|

# of Participants (out of 19) |

Participant Performance |

|

Found link to Worksheet? |

12 |

Read “for a year’ in FT employee hours item |

15 |

Calculation error – FT employee hours |

11 |

Calculation error – Other employee hours |

13 |

Auto-fill confusion |

10 |

Could not complete worksheet |

2 |

|

|

Participant Comments |

|

Add a calculator |

9 |

Break up Worksheet into more steps |

3 |

Make section B more like section A |

4 |

Twelve of 19 participants were able to find the link to the Worksheet on their own (with an average time to first click of 4.9 seconds), and the remaining 7 participants were directed to the Worksheet when it became apparent that they were stuck. Eye-tracking analysis revealed that the majority of study participants (15 of 19) read the bolded “for a year” in the full-time employee hours item. Despite this, about 60 percent of participants made mistakes in their entries for full-time employee hours (second field in Section A) and “hours worked by other employees” (Section B). The most common errors were failure to do any computation (i.e., to simply type in the number of hours a full-time employee worked per week or per pay period), and failure to calculate annual hours correctly (e.g., to multiple the number of part-time hours per pay period, 40, by the number of pay periods, but neglect to multiply this product by the number of part-time employees). One participant understood that she was supposed to provide an annual estimate per employee, but did not know how to calculate that value. She became stuck and the task facilitator had to intervene/exit the worksheet.

The auto-fill function in the last box of Section A and in Section C was another source of confusion for more than half of the study participants (n=10). Eight participants actively (and in some cases, repeatedly) tried to click in these boxes to enter a response (which the Worksheet does not allow), and two kept referring back to the task materials in search of information that could be used to answer these “questions.” This ultimately was a non-critical problem for all but one participant. Once they started filling in some of the other items in the Worksheet, the auto-fill functionality became apparent. Nine out of 10 participants realized what these fields were doing and moved through the Worksheet successfully (albeit with a high probability of calculation errors). One participant got stuck trying to correct the auto-filled value displayed in Section C (to conform to the ‘total hours worked’ value used in Task 1), and the test facilitator had to intervene.

During debriefings, participants spontaneously offered suggestions for ways to improve the total hours Worksheet. Not surprisingly, given participants’ calculation difficulties, the most common suggestion was to add a calculator function to the Worksheet. This would have helped the few participants who made simple arithmetic errors. The biggest problem, however, was that users failed to understand (or perhaps forgot to implement) the formula for calculating annual hours per employee. As reflected in the last two rows of Table 3, a number of participants suggested that a more step-wise approach would make the Worksheet more usable and useful. One participant asked, “Why can’t it ask me separately for the number of FT employees, the number of pay periods, and the hours generally worked per pay period, rather than making me do all of the work?” Other participants did not understand why there were different questions/approaches to capture full-time employee hours (Section A) and part-time/other employee hours (Section B), and preferred the more step-wise approach. Finally, several participants noted that it was unlikely that they would need to use the Worksheet if they were actual SOII respondents because their company would provide them with the total hours number, or if they did need to use it, they would have pre-tabulated data that could then be used directly to answer the items in the Worksheet.

Impact of Edits on Case with Days Away From Work Page

Table 4 displays the key study outcome measures of the impact of edit formatting on the detailed Case reporting page, after collapsing across Tasks 3 and 4. Since there were two edits triggered on this page – for the ‘Job Title’ and ‘Employee’s Age’ items – and implementation of those edits differed by treatment condition, the findings are presented separately by condition (i.e., Baseline, Inline, and Baseline Plus) and edit (‘Job Title’ and ‘Employee’s Age’). As in the analysis of Section 1 performance (see Table 2), to be eligible for these analyses the SOII instrument had to present an edit and there needed to be sufficient data to determine if the participant saw the edit. Although there were a few instances in which system errors prevented proper implementation of the Case page edits and/or eye-tracking data were unavailable, the number of usable cases was generally very high (see the first two rows under each sub-section of Table 4).

We first examined the extent to which participants attended to the text of the ‘Job Title’ edit message. Recall that in the Baseline and Baseline Plus conditions, this text was presented in red at the top of the screen and was part of the page’s larger edit message that also pertained to the ‘Employee’s Age’ edit. In the Inline condition, the ‘Job Title’ edit message text was presented in red to the right of the field, and pertained only to the ‘Job Title’ edit. The findings indicate that participants were quicker and more likely to notice the edit message when it was placed at the top of the page than when it was adjacent to the item. More than 80 percent of Baseline and Baseline Plus participants (9 of 11 and 9 of 10, respectively) looked at the top-of-the-page edit message, whereas only two-thirds (6 of 9) of Inline participants looked at their adjacent message, and this was roughly the same distribution of participants across the three conditions who read (not just glanced at) the text of the edit message. The elapsed time between the when the edit message first displayed and when participants first looked at the edit text also was considerably longer in the Inline condition than in the Baseline and Baseline Plus conditions (4.9 seconds compared to 1.3 and 0.7 seconds, respectively).

Table 4. Performance on the Case with Days Away from Work Page, Collapsing Across Tasks 3 and 4

|

Condition |

||

Baseline |

Inline |

Baseline Plus |

|

JOB TITLE EDIT |

|

|

|

Received edit? |

12/12 |

9/13 |

11/12 |

|

|

|

|

Acceptable eye track? |

11/12 |

13/13 |

10/11 |

|

|

|

|

Notice edit message text? |

9/11 |

6/9 |

9/10 |

Time to 1st fixation (sec) - text |

1.3 |

4.9 |

0.7 |

Read text? |

9/11 |

6/9 |

8/10 |

|

|

|

|

Notice title field after edit? |

9/11 |

6/9 |

10/10 |

Time to 1st fixation (sec) – field |

6.5 (n=8) |

0.9 |

1.0 (n=10) |

Time to 1st fixation (sec) – field, from Age field |

11.8 (n=1) |

n/a |

n/a |

|

|

|

|

Complied with job title edit request (read edit text)? |

7/9 |

5/6 |

6/8 |

Complied with job title edit request (all eligible)? |

7/12 |

5/9 |

6/11 |

|

|

|

|

EMPLOYEE’S AGE EDIT |

|

|

|

Received edit? |

12/12 |

11/13 |

11/12 |

|

|

|

|

Acceptable eye track? |

12/12 |

13/13 |

10/11 |

|

|

|

|

Notice edit message text? |

see above |

5/11 |

see above |

Time to 1st fixation (sec) - text |

“ |

3.3 |

“ |

Read text? |

“ |

4/11 |

“ |

|

|

|

|

Notice age field after edit? |

8/12 |

7/11 |

7/11 |

Time to 1st fixation (sec) – field |

21.3 |

3.5 |

23.5 |

Time to 1st fixation (sec) – field, from Title field |

9.5 |

n/a |

4.3 |

|

|

|

|

Complied with age edit request (read edit text)? |

7/9 |

4/4 |

4/8 |

Complied with age edit request (all eligible)? |

7/12 |

4/11 |

4/11 |

A review of participants’ eye-gaze videos suggest one reason for these findings is that Inline participants’ attention was focused on answering the next item on the page (i.e., the ‘Data of injury or onset of illness’ question). This item used a series of drop-down menus, one of which partially obscured the ‘Job Title’ field. Some Inline participants reported that they had noticed something change on the ‘Job Title’ item (out of their peripheral vision), but had elected to complete one of the ‘Date of injury’ drop-down items before investigating the ‘Job Title’ field. When these participants returned to the ‘Job Title’ item, they tended to focus first (and sometimes exclusively) on the red, highlighted field. Others reported in debriefing that they had simply not seen the ‘Job Title’ edit message text or the change in the field’s color. By contrast, participants in the Baseline and Baseline Plus conditions tended to reorient their visual focus to the top of the page after submitting the “Save & Continue” button (triggering the edit). Therefore, when the page reloaded in the Baseline and Baseline Plus conditions, these participants already were fixated on the portion of the screen where the edit message appeared.

We also observed differences across the three conditions in participants’ likelihood of looking at the ‘Job Title’ field after the edit was triggered. One-hundred percent (10 of 10) of Baseline Plus participants, 81 percent of Baseline participants (9 of 11), and 67 percent of Inline participants (6 of 9) fixated on the field post-edit. Underscoring the power of field highlighting to draw users’ attention, when study participants in the Inline and Baseline Plus conditions (where red highlighting was used to denote fields that triggered the edit) did look at the ‘Job Title’ field after the edit, they were much quicker to do so than participants who eventually located this field in the Baseline condition (0.9, 1.0, and 6.5 seconds, respectively). One Baseline participant who read the top-of-the-page edit message initially scrolled past the ‘Job Title’ field to first re-type his answer to the ‘Employee’s Age’ item. This resulted in an unusually long duration for this participants’ ‘Job Title’ time-to-first-fixation measure (the participant spent several minutes trying to ‘fix’ his ‘Employee’s Age’ entry), so we calculated the time it took him to locate the ‘Job Title’ field after addressing the ‘Employee’s Age’ edit (i.e., 11.8 seconds).

Table 4 also shows a range of participant compliance with the ‘Job Title’ edit request (i.e., re-typing the title) across conditions. Compliance was assessed in two ways. The first measure reflects compliance among only those participants who read the edit message text. The second measure assesses compliance among all participants who received the edit, regardless of whether they saw the edit or not. As shown in Table 4, compliance among those who read the edit message text was slightly higher for Inline participants than Baseline or Baseline Plus participants: 83% (5 of 6) vs. 78% (7 of 9) and 75% (6 of 8), respectively. Overall compliance rates were slightly higher in the Baseline condition (58% - 7 of 12), than in the Inline (56%, 5 of 9) or Baseline Plus (55%, 6 of 11) conditions. The differences between conditions in both compliance measures are not large, and probably reflect the influence of a combination of factors (e.g., unique respondent characteristics within each treatment sample; the saliency of different features of the edit formats; the ecological validity of the edit message request itself). For example, think-aloud comments from 6 participants indicated that they were not sure why they were being asked to re-type their ‘Job Title’ entry (e.g., “It looks like I spelled it correctly.” “You said that I could make up whatever answer I wanted to – why does it want me to type it again?”). Other participants might have felt similarly and just not voiced this reaction. Edit compliance likely would be a more informative measure with real SOII respondents interacting with actual SOII edits.

The bottom half of Table 4 summarizes participant performance results related to the ‘Employee’s Age’ edit. The results tell roughly the same story as the data discussed for the ‘Job Title’ edit. Fewer than half (5 of 11) of the Inline participants looked at the ‘Employee’s Age’ edit message and only slightly more than a third (36%, 4 of 11) read the edit text (compared to over 80 percent of participants who fixated on and read this edit message in the other two conditions). This represents a performance decline for Inline participants relative to their interactions with the ‘Job Title’ edit message. And, although Inline participants who did notice the ‘Employee’s Age’ edit message text continued to do so more quickly than those in the Baseline condition (3.3 vs. 6.5 seconds), it took them three times longer to notice this edit than to notice the earlier ‘Job Title’ edit text (3.3 vs. 0.9 seconds). One likely reason for these findings is that the placement of the ‘Employee’s Age’ edit text in the Inline condition was further away from participants’ visual focal point than it had been in the comparable situation involving the ‘Job Title’ item. That is, most Inline participants triggered the ‘Employee’s Age’ edit when they clicked on the ‘MM’ drop-down menu in the ‘Employee’s date hired’ item. So, participants not only were focused on this subsequent item rather than the ‘Employee’s Age’ edit text, but that edit text was far away from their field of vision. Moreover, the “Employee’s date hired - MM’ ‘drop-down’ menu actually opened upward and obscured part of the highlighted ‘Employee’s Age’ field above.

About two-thirds of participants in each of the treatment conditions looked at the ‘Employee’s Age’ field after the edit was triggered. This was a marked deterioration in performance for Baseline and Baseline Plus participants relative to their response to the ‘Job Title’ edit (where all of the Baseline Plus and more than 80 percent of Baseline participants looked at the ‘Job Title’ field after the edit); about the same proportion of Inline participants (67%) looked at the ‘Employee’s Age’ field as looked at the ‘Job Title’ field following those edits. Inline participants again were faster to fixate on the affected field than participants in the other conditions. Both results are unsurprising given that the edit message and highlighted ‘Employee’s Age’ fields were ‘below the fold’ for the Baseline and Baseline Plus condition, whereas participants in the Inline condition did not have to scroll to locate them. Participants in the Baseline Plus condition were more than twice as fast those in the Baseline condition to locate the ‘Employee’s Age’ field after having addressed the ‘Job Title’ edit (4.3 vs. 9.5 seconds, respectively), as well – again suggesting the challenges users face with long, scrolling pages and the efficacy of field highlighting.

Compliance with the ‘Employee’s Age’ edit request was generally high for Baseline and Inline participants who read the edit text (78% and 100%, respectively), but half of those who saw the edit text in the Baseline Plus condition failed to re-enter their entries. Three of these Baseline Plus participants just scrolled down the page after addressing the first edit (‘Job Title’) and did not look the ‘Employee’s Age’ field, or only glanced at it in passing. When probed in the debriefing, these participants indicated that they had not noticed the red highlighted field. When another participant was shown the highlighted ‘Employee’s Age’ edit field, she remarked that it ‘made sense,’ but that her attention was not drawn to it (“I didn’t make the connection that I needed to fix my answer.”). Overall compliance (regardless of whether the edit message was read), was lower for all groups, and particularly low for the Inline and Baseline Plus conditions.

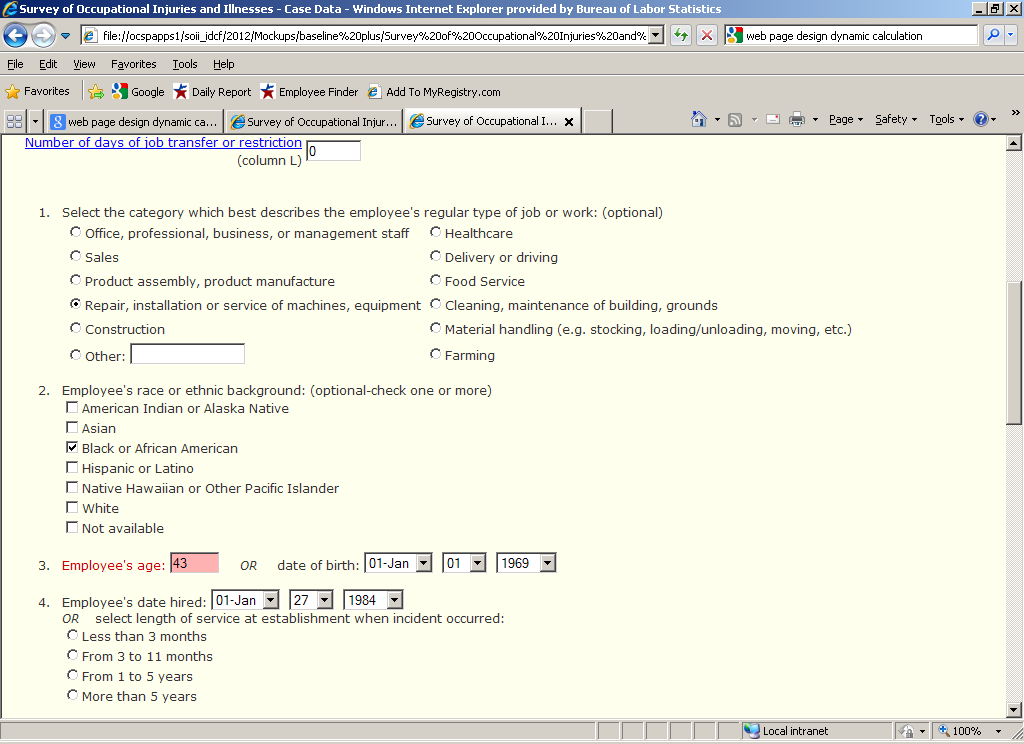

Other Usability Issues/Comments on the Cases Page

Participants had very few critical comments about the Case with Days Away from Work page. Most found the questions and layout to be straightforward, and the task to be easier than the Section 1 task(s) (in part because the Case-page tasks were designed to be more naturalistic – participants could make up responses – and the edit messages were more directive and self-explanatory). One participant commented that he liked that the fields/items on the page varied from text entry to radio buttons to drop-down menus. Two participants said that the text size on the page seemed too small. Three participants expressed negative reactions to the drop-down menus (e.g., “Why can’t I just enter in a data manually rather than hunting to click on the year?”). One participant did not realize that the drop-down menu for year of birth was scrollable and got stuck. Another participant said that she would have like a spell-check function in the open-ended text entry boxes. By far the most obvious (if minor) usability issue had to do with participants not seeing the “OR” between alternative ways of providing answers to the ‘Employee’s Age’ and ‘Employee’s date hired’ items. Twelve out of 19 participants did not notice they had a choice in how to report this information, and provided responses to each component. Several of those who did notice this option said that they liked it (e.g., “It saves me some work.” “It’s good to give employers the option to provide whichever information they have at hand.”)

Participants’ Stated Preferences for Different Edit Formats

After participants had completion all four study tasks, the task facilitator briefly showed them examples of the three different edit formats and asked them to select their favorite. Fourteen of 19 participants said that they liked the Inline version the best, three selected the Baseline Plus version, one said it was a tie between the Baseline Plus and Inline versions, and one chose the Baseline format. The most common reason given for preferring the Inline version was that it allowed participants to see right away if a mistake was made and what needed to be done. (e.g., “I like that it’s immediate and that it’s right next to the field…it allows me to keep going.” “I don’t have to go through the entire page again!”). Several participants indicated that they were familiar with this form of notifying users of potential issues or instructions (e.g., “I fill out a lot of forms. I see this [approach] all the time, so I’m used to it.”). Proponents of the Baseline Plus condition liked that the message at the top of the page directed them where to look, and appreciated that the field highlighting meant that they did not have to search for the relevant field (e.g., “I don’t have to go hunting for an answer.”).

Discussion and Recommendations

Edit Format

There are tradeoffs with any design decisions. In the case of selecting an edit format, the results of this study suggest that adopting an inline approach can improve the speed with which users notice that an edit has been triggered and attend to the relevant fields, but may cause them to pay less attention to the accompanying edit text. The specific implementation and placement of inline edit messages can impact performance, as well. In Section 1, the inline edit message text appeared beneath the Average Hours Worked element, and was fairly far away from the entry boxes that participants needed to focus on and fix. Similarly, in the Case page, the ‘Employee’s Age’ inline edit text was probably too far from where participants’ attention was focused when the edit was triggered (i.e., the ‘Employee date hired - MM’ item).

Despite participants’ preferences for the Inline approach, a sizable minority of participants who received this condition simply did not notice or carefully read the edits (particularly on the Case page). Based on our observations and respondent comments, the two most likely explanations for this finding are that (1) users who are engaged in the act of filling a form/instrument can become hyper-focused on filling out item in front of them, rather than attending to possible errors or revisions (this is consistent with the ‘modal theory of form completion’; see Bargas-Avila et al., 2007, as discussed in our previous literature review), and/or (2) the color contrasts and formatting used in the inline edits simply were insufficient to draw users’ visual attention to these elements (several participants in fact commented that the highlighted fields did not stick out enough, and that the reddish color was too faded against the yellow background).

If there is a ‘winner’ among the three approaches tested in this study, it would be the Baseline Plus condition. Although few participants selected this as their preferred method, the performance data on the Section 1 and Case page tasks were strong. Nearly all of the Baseline Plus participants noticed and read the top-of-the-page edit text, and they consistently found the relevant fields (thanks to the field highlighting), and did so more quickly than Baseline participants generally. Some participants missed/scrolled by the second edit on the Case page (‘Employee’s Age’) despite the red highlighting, so if this method were to be adopted in production, there would need to an iterative functionality (i.e., edits that are initially ignored would be flagged upon second submission of the page, etc.). It also might be useful to experiment with different ways of directing users to the fields responsible for the edits (e.g., including links to those items in the top-of-the-page edit text; using richer colors or other visually distinctive formatting in the fields themselves).

Regardless, it would be extremely useful to examine these issues in more detail with a sample of actual SOII respondents interacting with their own data in the IDCF instrument (or some test/development version). Some of the apparent inattention and confusion exhibited by participants in the present study was undoubtedly due to the fact that they were being asked to perform an unfamiliar task with unfamiliar or artificial data. This was a known limitation going into the study, though not a fatal one – we can and did learn much from even these somewhat constrained, simulated interactions.

Other Observations and Recommendations

The Average Hours Worked (AHW) element in Section 1 appears problematic for several reasons. First, in the Baseline condition (and in the IDCF instrument), the AHW value is presented in a gray box. Clearly this box drew the attention of participants in this study, but it also suggested to some that it had an interactive functionality (text entry) that it did not have. This can result in a situation in which users become confused and frustrated (e.g., repeatedly trying to click in the box). By contrast, the format of the AHW element in the other two conditions resulted in considerably fewer participants attending to it. Based on participant comments in this study and our own understanding of this element generally, the value of the AHW element as currently implemented seems questionable. The edit message in Section 1 does not reference the AHW number (only the entries in the two preceding items), and the element appears to get somewhat lost (conceptually and visually) on the page (except in the Baseline condition, where the box draws users attention). If the program office wants to retain this element (e.g., if SOII participants requested it, or report liking it), we suggest that the language of the edit message be modified to incorporate reference to the derived AHW value. One possible approach would be:

WARNING: we have calculated the Approximate Hours Worked per Employee for your company based on your entries for the ‘average number of employees’ and ‘total hours worked by all employees.’

This indicates an unusually short (long) workweek.

Please check that your entries are correct or contact the phone number on the front of your survey for assistance.

The other feature of the SOII instrument that study participants struggled with was the Total Hours Worksheet. Most of the problems either stemmed from participant misunderstandings about how to calculate annual hours given disaggregated data on number of pay periods, number of employees, and typical number of hours per pay period, or from simple calculation errors. It is unclear in the absence of information about how often this worksheet is used by actual IDCF respondents, and the issues that arise during its use, whether the problems we observed are representative or an artifact of the study. From a design standpoint, however, many of the improvements/changes that participants suggested (e.g., using a more step-wise approach, including a calculator function, making it more clear what are text-entry boxes and what information is auto-filled, making part B more similar to part A, etc.) seem like they would improve the worksheet’s usability and user experience.

Finally, we noted that a number of participants thought that the Section 1 page was too crowded. This may be a testing artifact. Our study participants were given two pieces of information to report on that page (‘average annual number of employees’ and ‘total hours worked by all employees’), but were not provided with any additional information about the (fictional) establishment, or with survey forms referenced in Section 1. It therefore is understandable that some participants might find the content preceding the two relevant entry fields unnecessary or overwhelming. However, the page does contain a lot of text that the user is expected to digest, and the eye-tracking data from in this study (and past usability findings, generally) suggest that people often do not read this amount of text carefully. Anything that can be done to make the page appear less cluttered would likely improve its usability. One approach would be break up the current Section 1 page into two separate pages – one where users can review and update their Establishment Information, and another specifically for entering employees, hours, and summary case data.

Appendix A – Test Protocol

Tasks and Debriefing Protocol

Task 1: Enter Information about Number of Company Employees and Total Hours Worked

For the purposes of this task and those that follow, you will be reporting for the calendar year 2011.

Over the course of the 2011 ski season, Ski Solutions had an average of 15 employees.

The total hours worked by all employees for 2011 was 12,000 hours.

2011 was a typical year for Ski Solutions. There was nothing unusual that affected the number of employees it hired or the hours those employees worked.

In this task, you will be asked to report the annual average number of employees and the total hours worked by all employees for 2011.

When you are ready to launch the website and begin entering in the company information, please let us know. (And, please don’t forget to think out loud as you go through the task!)

Post-task debriefing probes:

How difficult was it for you to enter in information about the company’s employees and hours?

Was there any language on the website that confused you?

Were there any features of the website layout that you found confusing or frustrating, or which you think could be improved?

[IF NOT MENTIONED OR OBSERVED PREVIOUSLY] Did you notice the information about Average Hours Worked per Employee? What was your reaction to this – did it make sense? Can you tell me in your own words what this means?

Task 2: Enter Information about Number of Employees and Total Hours Worked II

For this task, let’s assume that the company had the same average number of employees as you saw in the previous task (i.e., 15 employees), but because some of those employees worked part-time, you’ll need to do a bit more to calculate the total hours worked in 2011. The SOII website offers respondents a worksheet to estimate the total hours worked by all employees, so we’d like you to use the worksheet and the following information to enter in a new total hours worked estimate.

In 2011, Ski Solutions paid its employees twice a month, so over the five months that the company was open for business, it had a total of 10 pay periods.

In a typical pay period, the company employed 10 full-time employees and 5 part-time employees. (So, the annual average number of employees working for the company in 2011 was still 15.)

Full-time employees worked 80 hours per pay period (40 hours per week)

Part-time employees worked 40 hours per pay period (20 hours per week)

Again, 2011 was a typical year for Ski Solutions. There was nothing unusual that affected the number of employees it hired or the hours those employees worked.

For this task, please report the annual average number of employees and use the worksheet to estimate the total hours worked by all employees for 2011.

When you are ready to launch the website and begin entering in the company information, please let us know. (Don’t forget to think out loud as you go through the task!)

Post-task debriefing probes:

How difficult was it for you to use the worksheet to calculate the total number of hours?

Was there any language on the worksheet that confused you?

Were there any features of the worksheet layout that you found confusing or frustrating, or which you think could be improved?

Task 3: Enter Case Details – I

In 2011, Ski Solutions had two work-related incidents that resulted in employee injuries. In both cases, the injuries were suffered by members of the ski lift maintenance crew as they worked to repair faulty equipment. The injuries were not severe, but both employees had to miss two days of work before they were sufficiently recovered. There were no other accidents, illnesses, or other incidents at Ski Solutions that resulted in days away from work or job transfers/restrictions in 2011.

Please use the website to begin reporting the cases with days away from work.

Note: the website may ask you to refer to specific OSHA forms as you fill out the survey, but we will not be using those forms for this study. Simply use the information provided in this task description to fill out the relevant fields of the survey form.

For this task, you will be asked to enter specific details about the first injury cases. Please try to do so – just make up answers for any questions on the page that require a response (e.g., about the injured employee’s name, the date of injury, etc.). The specific answers you give are not important – we are only interested in how easy or difficult it is for people to navigate through the website and provide the information necessary for completing the survey.

When you are ready to begin entering information about the first of the 2 injury cases that resulted in days away from work, please let us know. (Again, please think out loud as you go through the task.)

Post-task debriefing probes:

How difficult was it for you to enter in information about the company’s work-related injury cases?

Was there any language on these pages that confused you?

Were there any features of the layout that you found confusing or frustrating, or which you think could be improved?

[Note any comments Rs make about edits, but do not probe about them in any detail until after the completion of the next task.]

Task 4: Enter Case Details - II

In this task, you’ll report details about the 2nd case that resulted in days away from work. Recall that the injury kept the employee away from work for 2 days. Again, for this task you will not be using the OSHA/SOII forms – you should make up answers for any questions on the page that require a response. We only are interested in how easy or difficult it is for people to navigate through the website and provide the information necessary for completing the survey.

When you are ready to launch the website and begin entering information about the second of the 2 injury cases, please let us know. (Again, please think out loud as you go through the task.)

General Debriefing Questions.

Now I have a few general questions to ask you about your experience completing the survey. Non-scripted questions will be added based on testing observations and additional post-testing questions will be added based on tasks.

What would you say was the most difficult step involved in completing the survey? If you personally didn’t have a problem, what do you think would be the most difficult step for others?

Were there any places where the instructions could be improved or were needed?

What are your general impressions of the online survey?

You may have noticed that at various times when you were filling out the survey the website showed messages asking you to confirm or correct an answer that you provided.

What were your reactions to the messages generally?

Let’s take a closer look at the individual messages and get your reactions to each of them. How about the messages that appeared on the first screen (show respondent screen/message)

Did this make sense to you? Can you tell me in your own words what it was asking you to do?

[If edit was triggered] Did you notice this when you were filling out the form?

If not, why not?

If so, what was your reaction – did you find it helpful or not?

Now let’s look at look at the messages that appeared on the detailed case entry screen (show respondent screen/message)

Did you notice this when you were filling out the form?

If not, why not?

If so, what was your reaction – did you find it helpful or not?

Now let’s look at a couple of alternative ways these messages could have been presented (show respondent screen/message, demonstrate edits)

What are your reactions to this message format?

Do you think you would have been more or less likely to notice the message with this format or the other format you saw?

Have you seen this kind of format/this approach used before?

Which approach/format do you prefer?

[If not obvious from previous answer] Can you tell me more about that – why do you prefer __________?

[Show 2nd alternative format for Detailed Cases page] On this task we presented the messages a bit differently?

What are your reactions to this format/approach?

Do you think you would have been more or less likely to notice the message with this format or the other format you saw?

Have you seen this kind of format/this approach used before?

Which approach/format do you prefer – of the three seen?

[If not obvious from previous answer] Can you tell me more about that – why do you prefer __________?

Appendix B – Screenshots of Edit Formats

Section 1: Establishment Information Page

Baseline – Post-edit

Inline – Post-edit

Baseline Plus – Post-edit

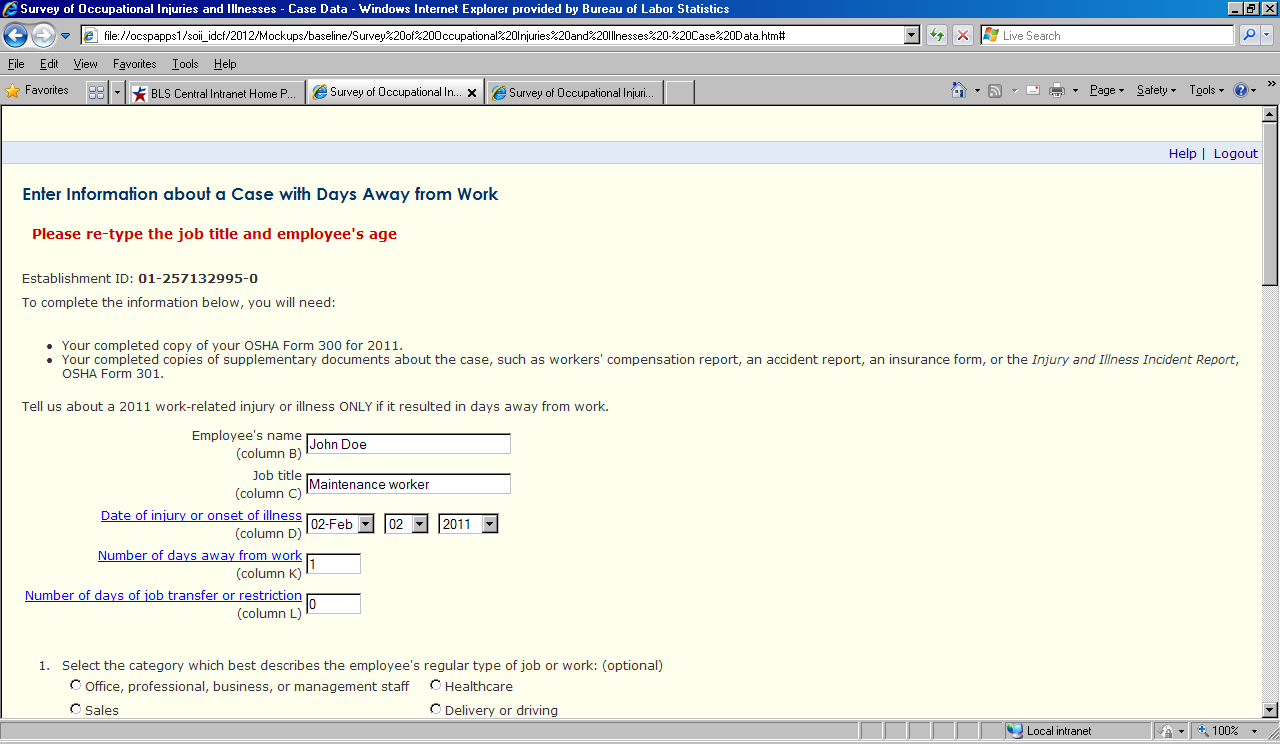

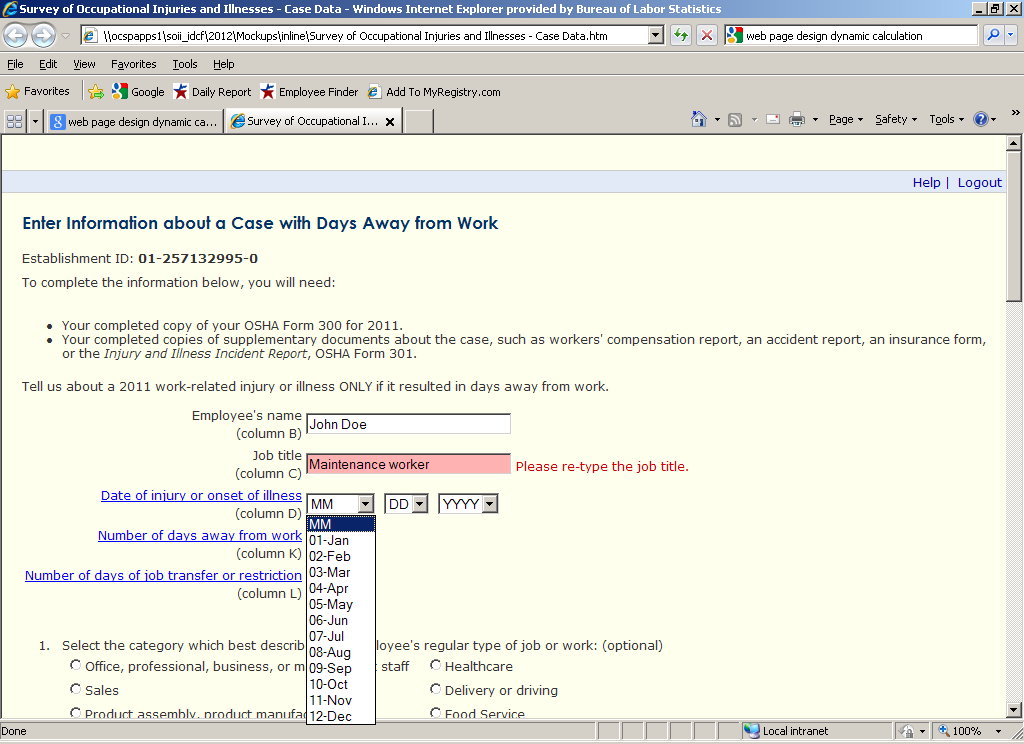

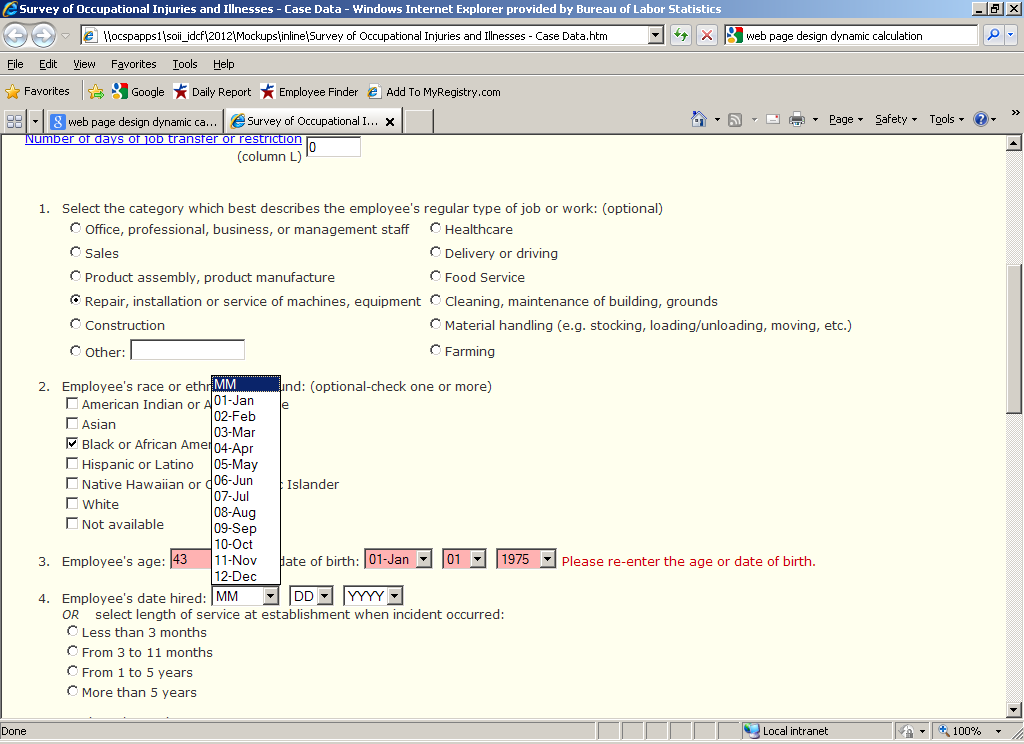

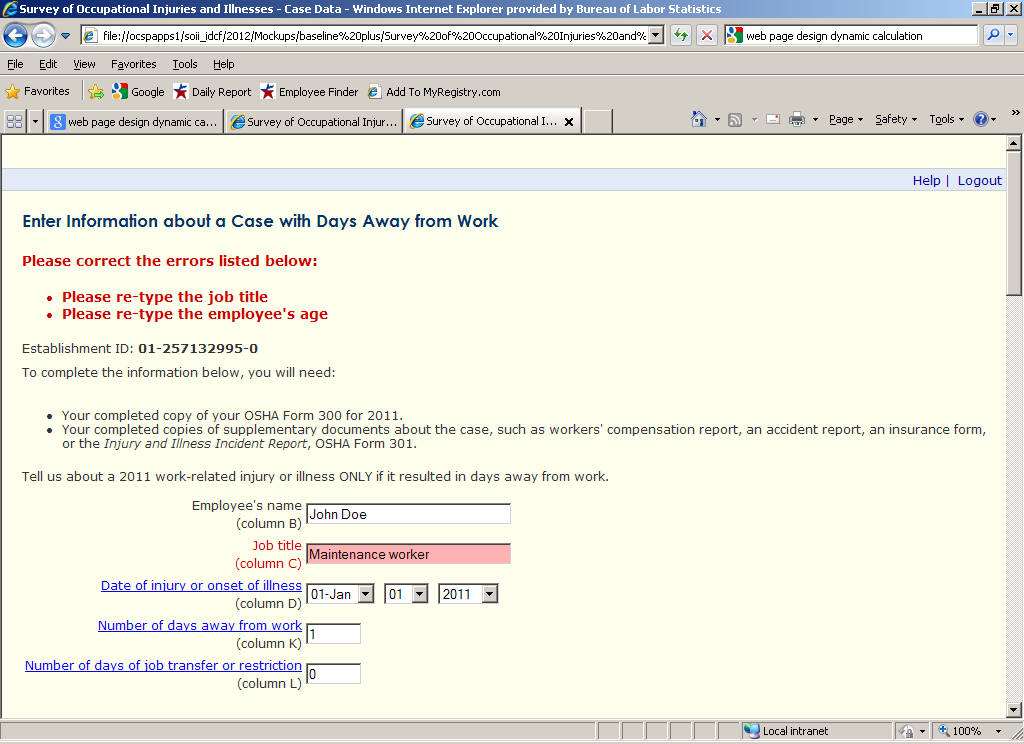

Case with Days Away from Work Page

Baseline – Post-edit

Inline – Post-edit, 1

Inline – Post-edit, 2

Baseline Plus – Post-edit, 1

Baseline Plus – Post-edit, 2

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | fricker_s |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-20 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy