2019 NSDUH SS_Part B_Extension_1.29.19

2019 NSDUH SS_Part B_Extension_1.29.19.docx

2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

OMB: 0930-0110

2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health

SUPPORTING STATEMENT

B. COLLECTIONS OF INFORMATION EMPLOYING STATISTICAL METHODS

1. Respondent Universe and Sampling Methods

The respondent universe for the 2019 NSDUH is the civilian, noninstitutionalized population aged 12 or older within the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The NSDUH universe includes residents of noninstitutional group quarters (e.g., shelters, rooming houses, dormitories), residents of Alaska and Hawaii, and civilians residing on military bases. Persons excluded from the universe include those with no fixed household address (e.g., homeless transients not in shelters, and residents of institutional group quarters such as jails and hospitals).

Similar to previous NSDUHs, the sample design consists of a stratified, multi-stage area probability design (see Attachment A for a detailed presentation of the Sample Design). As with most area household surveys, the NSDUH design continues to offer the advantage of minimizing interviewing costs by clustering the sample. This type of design also maximizes coverage of the respondent universe since an adequate dwelling unit and/or person-level sample frame is not available. Although the main concern of area surveys is the potential variance-increasing effects due to clustering and unequal weighting, these potential problems are directly addressed in the NSDUH by selecting a relatively large sample of clusters at the early stages of selection and by selecting these clusters with probability proportionate to a composite size measure. This type of selection maximizes precision by allowing one to achieve an approximately self-weighting sample within strata at the latter stages of selection. Furthermore, it is appealing because the design of the composite size measure makes the FI workload roughly equal among clusters within strata.

A coordinated design was developed for the 2014-2017 NSDUHs and has been extended to the 2018-2022 NSDUHs. To accurately measure drug use and related mental health measures among the aging drug use population, this design allocates the sample to the 12 to 17, 18 to 25, and 26 or older age groups in proportions of 25 percent, 25 percent, and 50 percent, respectively.

In anticipation of the next decennial census data not being available at the time the 2018-2022 sample would be selected, a large reserve sample was selected when the 2014–2017 NSDUH sample was selected. Thus, the 2018-2022 sample has been selected down to the area segment level. The sample selection procedures begin by geographically partitioning each state into roughly equal size state sampling regions (SSRs). Regions are formed so that each area within a state yields, in expectation, roughly the same number of interviews during each data collection period. As shown in Table 1 of Attachment A, this partition divides the U.S. into 750 SSRs.

Within each of the 750 SSRs formed for the 2014-2022 NSDUHs, a sample of Census tracts is selected. Then, within sampled Census tracts, Census block groups are selected. This stage of selection facilitates possible transitioning to an address-based sampling (ABS) design in the future. Finally, within Census block groups, smaller geographic areas, or segments, are selected. A total of 48 segments per SSR are selected: 20 to field the 2014-2018 surveys and 28 “reserve” segments which are available to field the 2018-2022 NSDUHs. In general, segments consist of adjacent Census blocks and are equivalent to area segments selected at the second stage of selection in the 2005-2013 NSDUHs.

In summary, the first-stage stratification for the 2014-2022 NSDUHs is states and SSRs within states, the first-stage sampling units are Census tracts, the second-stage sampling units are Census block groups, and the third-stage sampling units are small area segments. This design for the 2014-2022 NSDUHs at the first stages of selection is desirable because of (a) the large person-level sample required at the latter stages of selection in the design and (b) continued interest among NSDUH data users and policymakers in state and other local-level statistics.

The coordinated design facilitates 50 percent overlap in third-stage units (area segments) between each two successive years from 2014 through 2022. The primary benefit of the sample overlap is the cost savings achieved from being able to reuse the list frames for half of the area segments in the 2015 through 2022 surveys. In addition, the expected precision of difference estimates generated from consecutive years (e.g., the year-to-year difference in past month marijuana use among 12- to 17-year-old respondents) is improved because of the expected positive correlation resulting from the overlapping sample.

Similar to previous NSDUHs, at the latter stages of selection, five age group strata are sampled at different rates. These five strata are defined by the following age group classifications: 12 to 17, 18 to 25, 26 to 34, 35 to 49, and 50 or older. Adequate precision for race/ethnicity estimates at the national level is achieved with the larger sample size and the allocation to the age group strata. Consequently, race/ethnicity groups are not over-sampled. However, consistent with previous NSDUHs, the 2019 NSDUH is designed to over-sample the younger age groups.

Table 1 in Attachment A shows the projected number of person respondents by state and age group. Table 2 (Attachment A) shows main study sample sizes and the projected number of completed interviews by sample design stage. Table 3 (Attachment A) shows the expected precision for key measures by demographic domain.

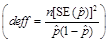

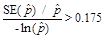

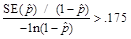

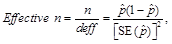

In addition, all estimates ultimately released as NSDUH data must meet published precision levels. Through a thorough review of all data, any direct estimates from NSDUH designated as unreliable are not shown in reports or tables and are noted by asterisks (*). The criteria used to define unreliability of direct estimates from NSDUH is based on the prevalence (for proportion estimates), relative standard error (RSE) (defined as the ratio of the SE over the estimate), nominal (actual) sample size, and effective sample size for each estimate. These suppression criteria for various NSDUH estimates are summarized in the table below.

Summary of NSDUH Suppression Rules

-

Estimate

Suppress if:

Prevalence Estimate,

,

with Nominal Sample Size, n,

and Design Effect, deff

,

with Nominal Sample Size, n,

and Design Effect, deff

(1) The estimated prevalence estimate,

,

is < 0.00005 or > 0.99995,1

or

,

is < 0.00005 or > 0.99995,1

or(2)

when

when

,

or

,

or when

when

,

or

,

or(3) Effective n < 68, where

or

or(4) n < 100.

Note: The rounding portion of this suppression rule for prevalence estimates will produce some estimates that round at one decimal place to 0.0 or 100.0 percent but are not suppressed from the tables.2

Estimated Number

(Numerator of

)

)The estimated prevalence estimate,

,

is suppressed.

,

is suppressed.Note: In some instances when

is not suppressed, the estimated number may appear as a 0 in the

tables. This means that the estimate is greater than 0 but less

than 500 (estimated numbers are shown in thousands).

is not suppressed, the estimated number may appear as a 0 in the

tables. This means that the estimate is greater than 0 but less

than 500 (estimated numbers are shown in thousands).Note: In some instances when totals corresponding to several different means that are displayed in the same table and some, but not all, of those means are suppressed, the totals will not be suppressed. When all means are suppressed, the totals will also be suppressed.

Means not bounded between 0 and 1 (i.e., Mean Age at First Use, Mean Number of Drinks),

,

with Nominal Sample Size, n

,

with Nominal Sample Size, n(1)

,

or

,

or(2) n < 10.

deff = design effect; RSE = relative standard error; SE = standard error.

NOTE: The suppression rules included in this table are used for detecting unreliable estimates and are sufficient for confidentiality purposes in the context of the first findings reports and detailed tables.

1

Starting with the 2015 NSDUH, the close to 100 percent portion of the

rule was changed to

![]() >

0.99995 instead of the old rule, which was greater than or equal to

0.99995. This was done so the close to 0 and close to 100 rule were

both strict inequalities.

>

0.99995 instead of the old rule, which was greater than or equal to

0.99995. This was done so the close to 0 and close to 100 rule were

both strict inequalities.

2. Information Collection Procedures

Unless otherwise specified, the 2019 NSDUH procedures described in this section follow the same processes as used on the 2018 NSDUH.

Prior to the FI’s arrival at the SDU, a Lead Letter (see Attachment C) will be mailed to the resident(s) briefly explaining the survey and requesting their cooperation.

Upon arrival at the SDU, the FI will refer the resident to this letter and answer any questions. If the resident has no knowledge of the Lead Letter, the FI will provide another copy, explain that one was previously sent, and then answer any questions. If no one is home during the initial visit to the SDU, the FI may leave a Sorry I Missed You Card (Attachment F) informing the resident(s) that the FI plans to make another callback at a later date/time. Callbacks will be made as soon as feasible following the initial visit. FIs will attempt to make at least four callbacks (in addition to the initial call) to each SDU in order to complete the screening process and complete an interview, if yielded.

If the FI is unable to contact anyone at the SDU after repeated attempts, the FS may send one of the Unable-to-Contact (UTC) letters (Attachment J). These UTC letters reiterate information contained in the Lead Letter and present a plea for the resident to participate in the study. If after sending the UTC letter, an FI is still unable to contact anyone at an SDU, a Call-Me letter (Attachment J) may be sent to the SDU requesting that the resident(s) call the FS as soon as possible to set up an appointment for the FI to visit the resident(s).

When in‑person contact is made with an adult member of the SDU and introductory procedures are completed, the FI will present a Study Description (Attachment G) and answer any questions that person might have concerning the study. A Question & Answer Brochure (Attachment D) that provides answers to commonly asked questions may also be given. In addition, FIs are supplied with copies of the NSDUH Highlights & Newspaper Articles (Attachment R) for use in eliciting participation, which can be left with the respondent.

Also, the FI may utilize the multimedia capability of the touch screen tablet to display one of two short videos (approximately 60 seconds total run time) for members of the SDU to view, which provides a brief explanation of the study and why participation is important. The scripts for these videos are included as Attachment E.

If a potential respondent refuses to be screened, the FI has been trained to accept the refusal in a positive manner, thereby minimizing the possibility of creating an adversarial relationship that might preclude future opportunities for contact. The FS may then request that one of several Refusal Letters (Attachment K) be sent to the residence. The letter sent is tailored to the specific concerns expressed by the potential respondent and asks him or her to reconsider participation. Refusal letters are customized and also include the FS’s phone number in case the potential respondent has questions or would like to set up an appointment with the FI. Unless the respondent calls the FS or the Contractor’s office to refuse participation, an in-person conversion is then attempted by specially-selected FIs with successful conversion experience.

With respondent cooperation, the FI will begin screening the SDU by asking either the Housing Unit Screening questions, or the Group Quarters Unit Screening questions, as appropriate. The screening questions are administered using a 7-inch touch screen Android tablet computer. A paper representation of the housing unit and group quarters unit screening process is shown in Attachment I.

Once all household members aged 12 or older have been rostered, the hand-held computer performs the within-dwelling-unit sampling process, selecting zero, one, or two members to complete the interview. For cases with no one selected, the FI asks for a name and phone number for use in verifying the quality of the FI’s work, thanks the respondent, and concludes the household contact.

For each person selected to complete the full interview, the FI follows these steps:

If the selected individual is aged 18 or older, or aged 17 and living independently from his or her parent or guardian, and is currently available, the FI immediately seeks to obtain informed consent. Once consent is obtained, the FI begins to administer the questionnaire in a private setting within the dwelling unit. As necessary and appropriate, the FI may make use of the Appointment Card (in Attachment F) for scheduled return visits with the respondent.

If the selected individual is 12 to 17 years of age, except in rare instances where a 17-year-old is living independently from his or her parent or guardian, in which case the 17-year-old provides his or her own consent, the FI reads the parental introductory script (Attachment O) to the parent or guardian before speaking with the youth about the interview. Subsequently, parental consent is sought from the selected individual’s parent or legal guardian using the Parent section of the youth version of the Introduction and Informed Consent Scripts (Attachment H). Once parental consent is granted, the minor is then asked to participate using the Youth section of the same document. If assent is received, the FI begins to administer the questionnaire in a private setting within the dwelling unit with at least one parent, guardian or another adult remaining present in the home throughout the interview.

As mentioned in section A.3, the FI administers the interview in a prescribed and uniform manner with sensitive portions of the interview completed via ACASI. The changes to the 2019 NSDUH questionnaire are summarized in section A.1.

Race/ethnicity questions are FI-administered and meet all of the guidelines for the OMB minimum categories. The addition of the finer delineation of Guamanian or Chamorro and Samoan, which collapse into the OMB standard Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander category, were a requirement of the new HHS Data Collection Standards and will continue to be included in the 2019 questionnaire.1

In order to facilitate the respondent’s recollection of prescription-type drugs and their proper names pill images will appear on the laptop screen during the ACASI portions of interviews as appropriate in 2019. Also, respondents will use an electronic reference date calendar, which displays automatically on the computer screens when needed throughout the ACASI parts of the interview. Finally, in the FI-administered portion of the questionnaire, showcards are included in the Showcard Booklet (Attachment N) that allow the respondent to refer to information necessary for accurate responses.

After the interview is completed and before the verification procedures begin, each respondent is given a $30.00 cash incentive and an Interview Incentive Receipt (L) signed by the FI.

For verification purposes, interview respondents are asked to complete a Quality Control Form (Attachment Q) that requests his/her current address and phone number for possible follow‑up to ensure that the FI did his or her job appropriately. Respondents are informed that completing the Quality Control Form is voluntary. If he or she agrees, the respondent completes this form, places it in an envelope and seals it. The form is then mailed to the Contractor’s office for processing. In previous NSDUHs, less than one percent of the verification sample refused to fill out Quality Control Forms.

FIs may give a Certificate of Participation (Attachment S) to interested respondents after the interview is completed. Respondents may attempt to use these certificates to earn school or community service credit hours. As stated on the certificate, no guarantee of credit is made by SAMHSA or the Contractor. The respondent’s name is not written on the certificate. The FI signs his or her name and dates the certificate, but for confidentiality reasons the section for recording the respondent’s name is left blank. The respondent can fill in his/her name at a later time so the FI will not be made aware of the respondent’s identity. It is the respondent’s choice whether he or she would like to be identified as a NSDUH respondent by using the certificate in an attempt to obtain school or community service credit.

A random sample of those who complete Quality Control Forms are contacted via telephone to answer a few questions verifying that the interview took place, that proper procedures were followed, and that the amount of time required to administer the interview was within expected parameters. The CATI Verification Scripts (Attachment T) contain the scripts for these interview verification contacts via telephone, as well as the scripts used when verifying a percentage of certain completed screening cases in which no one was selected for an interview or the SDU was otherwise ineligible (vacant, not primary residence, not a dwelling unit, dwelling unit contains only military personnel, respondents living at the sampled residence for less than half of the quarter). For verification purposes, a Quality Control letter (Attachment U) is mailed to a respondent’s address when a phone number is not available.

As noted above, all interview data are transmitted on a regular basis via secure encrypted data transmission to the Contractor’s offices in a FIPS-Moderate environment, where the data are subsequently processed and prepared for reporting and data file delivery.

Questionnaire

As explained in section A.3, the version of the questionnaire to be fielded in 2019 is a computerized (CAPI/ACASI) instrument based on the 2018 questionnaire.

As in past years, two versions of the instrument will be prepared: an English version and a Spanish translation. Both versions will have the same essential content.

The proposed CAI Questionnaire is shown in Attachment B. While the actual administration will be electronic, the document shown is a paper representation of the content that is to be programmed. The interview process is designed to retain respondent interest, ensure confidentiality, and maximize the validity of response. The questionnaire is administered in such a way that FIs do not know respondents’ answers to sensitive questions, including those on illicit drug use and mental health. These questions are self-administered using ACASI. The respondent listens to the questions privately through headphones so even those who have difficulty seeing or reading are able to complete the self-administered portion. Topics that are administered by the FI (i.e., the CAPI section) are limited to Demographics, Health Insurance, and Income. Respondents are given the option of designating an adult proxy who is at home to provide answers to questions in the Health Insurance and Income sections.

The interview consists of a combination of interviewer-administered and self-administered questions. Interviewer-administered questions at the beginning of the interview consist of initial demographic items. The first set of self-administered questions pertain to the use of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, crack cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, methamphetamine, and prescription psychotherapeutic drugs (i.e., pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives). Similar questions are asked for each substance or substance class, ascertaining the respondent’s history in terms of age of first use, most recent use, number of times used in lifetime, and frequency of use in past 30 days and past 12 months. These substance use histories allow estimation of the incidence, prevalence, and patterns of use for licit and illicit substances.

Additional self-administered questions or sections follow the substance use questions and ask about a variety of sensitive topics related to substance use and mental health issues. These topics include (but are not limited to) injection drug use, perceived risks of substance use, substance use disorders (SUDs), arrests, treatment for substance use problems, pregnancy, mental illness, the utilization of mental health services, disability, and employment and workplace issues. Additional interviewer-administered CAPI sections at the end of the interview ask about the household composition, the respondent's health insurance coverage, and the respondent's personal and family income.

The detailed specifications for the proposed CAI Questionnaire for 2019 are provided in Attachment B.

3. Methods to Maximize Response Rates

In 2017, the weighted response rates were 75 percent for screening and 67 percent for interviews, with an overall response rate (screening * interview) of 51 percent. With the continuation of the $30.00 cash incentive for the 2019 survey year, the Contractor expects the weighted response rates for 2019 to be about the same as the 2017 rates.

NSDUH management staff continuously work with FIs to ensure all necessary steps are taken so that best response rates possible are achieved. Despite those efforts, as shown in Table 2 (“Screening, Interview, and Overall NSDUH Weighted Response Rates, by Year” in Section A.9), NSDUH response rates continue to decline. This decline of the screening, interview and overall response rates over the past 10 years can be attributed to three main factors:

Increase in respondent refusals;

Decrease in refusal conversion; and

Increase in controlled access barriers (i.e., gated communities, secured buildings, etc.).

Refusals at the screening and interviewing level have historically been a problem for NSDUH due to: 1) respondents feeling they are too busy to participate; 2) respondents feeling inundated with market research and other survey requests; 3) growing concerns about providing personal information due to raised awareness of identity theft and leaks of government and corporate data; and 4) concerns about privacy and increased anti-government sentiment.

The $30.00 cash incentive for interview completion was implemented beginning with the 2002 NSDUH (Wright et al., 2005). The decision to offer an incentive was based largely on an experiment conducted in 2001, which showed that providing incentives appeared to increase response rates. Wright and his coauthors explored the effect that the incentive had on nonresponse bias. The sample data were weighted by likelihood of response between the incentive and nonincentive cases. Next, a logistic regression model was fit using substance use variables and controlling for other demographic variables associated with either response propensity or drug use. The results indicate that for past year marijuana use, the incentive either encourages users to respond who otherwise would not respond or encourages respondents who would have participated without the incentive to report more honestly about drug use. Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether the incentive money is reducing nonresponse bias, response bias, or both. However, reports of past year and lifetime cocaine did not increase in the incentive category, and report of past month use of cocaine actually was lower in the incentive group than in the control group.

In addition to the $30.00 cash incentive and contact materials, to achieve the expected response rates, the 2018 NSDUH will continue utilizing study procedures designed to maximize respondent participation. This begins with assignment of the cases prior to the start of data collection, accompanied by weekly response rate goals that are conveyed to the FIs by the FS. When making assignments, FSs take into account which FIs are in closest proximity to the work, FI skill sets, and basic information (demographics, size, etc.) about the segment. FSs assign cases to the FIs in order to ensure maximum production levels at the start of the data collection period. To successfully complete work in remote segments or where no local FI is available, a traveling FI (i.e., a veteran NSDUH FI with demonstrated performance and commitment to the study) or a “borrowed” FI from another FS region can be utilized to prevent delays in data collection.

Once FIs transmit their work, data are processed and summarized in daily reports posted to a web-based case management system (CMS) accessed by FSs, which requires two-factor authentication for log-in as part of a FIPS-Moderate environment. On a daily basis, FSs use reports on the CMS to review response rates, production levels, and record of call information to determine an FI’s progress toward weekly goals, to determine when FIs should attempt contact with a case, and to develop plans to handle challenging cases such as refusal cases and cases where an FI is unable to access the dwelling unit. FSs discuss this information with FIs on a weekly basis. Whenever possible, cases are transferred to available FIs with different skill sets to assist with refusal conversion attempts or to improve production in areas where the original FI has fallen behind weekly response rate goals.

Additionally, FSs hold group calls with FI teams to continuously improve staff’s refusal conversion skills. FIs report the types of refusals they are currently experiencing and the FS leads the group discussion on how to best respond to the objections and successfully address these challenges. FSs regularly, on group and individual FI calls, work to increase the FI’s ability to articulate pertinent study information in response to common respondent questions.

Periodically throughout the year, response rate patterns are analyzed by state. States with significant changes are closely scrutinized to uncover possible reasons for the changes. Action plans are put in place for states with significant declines. Response and nonresponse patterns are also tracked by various demographics on an annual basis in the NSDUH Data Collection Final Report. The report provides detailed information about noncontacts versus refusals, including reasons for refusals. This information is reviewed annually for changes in trends.

As noted in section B.2 above, FIs may use a Sorry I Missed You Card (in Attachment F), NSDUH Highlights and Newspaper Articles (Attachment R), and a Certificate of Participation (Attachment S) to help make respondent contact and encourage participation. To aid in refusal conversion efforts, Refusal Letters (Attachment K) tailored to specific refusal reasons can be sent to any case that has refused. Similarly, an Unable-to-Contact Letter (in Attachment J) may be sent to a selected household if the FI has been unable to contact a resident after multiple attempts. For cases where FIs have been unable to gain access to a group of SDUs due to some type of access barrier, such as a locked gate or doorperson, Controlled Access Letters (in Attachment J) can be sent to the gatekeeper to obtain his or her assistance in gaining access to the units. In situations where a doorperson is restricting access, the FI can provide that doorperson a card to read to selected residents over the phone or intercom (in Attachment V) seeking permission to allow the FI into the building.

If those attempts fail, a Call-Me Letter (in Attachment J) may be sent directly to a selected household. These letters inform the residents that an FI has been trying to contact them and asks that they contact the FS by phone. If the resident calls the FS, the FS attempts to get the resident to agree to an appointment so the FI can return to that address and screen the household in person.

Aside from refusals and controlled access barriers, other field challenges attributing to a decline in response rates include:

An increase of respondents who are home but simply do not answer the door. In these instances, FIs try various conversion strategies (i.e., sending unable to contact/conversion letters) to address potential concerns that a respondent may have, while also respecting their right to refuse participation.

An increase in homes with video doorbells (RING, NEST, etc.), where a respondent can view someone at their door via a Smartphone. In these situations, FIs introduce themselves, show their ID badge and note that they are following up on the lead letter the respondent should have received in the mail.

An increase in respondents broadcasting messages across neighborhood social media platforms, such as Nextdoor.com, Facebook, etc. about FIs working in the area and making false claims that the study is a scam and warning residents not to open their door. In these situations, FIs inform the local police department they are working in the general area to address any concerns raised by the residents.

An increase in the number of respondents calling into the project’s toll-free number to refuse participation before ever being visited in person by an FI. In these instances, both the FS and FI are notified and the case is coded as a final refusal and no subsequent visits are made to that address.

An increase in hostile and adamant refusals. These cases are coded out as a final refusal and no subsequent visits are made to that address.

In addition to procedures outlined in this section, NSDUH currently employs the following procedures to avert refusal situations in an effort to increase response rates:

All aspects of NSDUH are designed to project professionalism and thus enhance the legitimacy of the project, including the NSDUH respondent website and materials. FIs are instructed to always behave professionally and courteously.

The NSDUH Field Interviewer Manual includes specific instructions to FIs for introducing both themselves and the study. Additionally, an entire chapter is devoted to "Obtaining Participation" and lists the tools available to field staff along with tips for answering questions and overcoming objections.

During new-to-project FI training, trainers cover details for contacting dwelling units and how to deal with reluctant respondents and difficult situations. During exercises and mock interviews, FIs practice answering questions and using letters and handouts to obtain cooperation.

During veteran FI training, time is spent reviewing various techniques for overcoming refusals. The exercises and ideas presented help FIs improve their skills and thus increase their confidence and ability to handle the many situations encountered in the field.

Finally, data have shown that experienced FIs are more successful in converting refusals. In 2018, NSDUH implemented a yearly FI Tenure-Incentive Plan to reward FIs monetarily for their dedication to the project and ultimately to reduce the FI attrition rate to ensure we retain more experienced FIs.

Nonresponse Bias Studies

In addition to the investigations noted above, several studies have been conducted over the years to assess nonresponse bias in NSDUH. For example, the 1990 NSDUH2 was one of six large federal or federally-sponsored surveys used in the compilation of a dataset that then was matched to the 1990 decennial census for analyzing the correlates of nonresponse (Groves and Couper, 1998). In addition, data from surveys of NSDUH FIs were combined with those from these other surveys to examine the effects of FI characteristics on nonresponse. One of the main findings was that those households with lower socioeconomic status were no less likely to cooperate than those with higher socioeconomic status; there was instead a tendency for those in high-cost housing to refuse survey requests, which was partially accounted for by residence in high-density urban areas. There was also some evidence that FIs with higher levels of confidence in their ability to gain participation achieved higher cooperation rates.

In follow-up to this research, a special study was undertaken on a subset of nonrespondents to the 1990 NSDUH to assess the impact of the nonresponse (Caspar, 1992). The aim was to understand the reasons people chose not to participate, or were otherwise missed in the survey, and to use this information in assessing the extent of the bias, if any, that nonresponse introduced into the 1990 NSDUH estimates. The study was conducted in the Washington, DC, area, a region with a traditionally high nonresponse rate. The follow-up survey design included a $10 incentive and a shortened version of the instrument. The response rate for the follow-up survey was 38 percent. Follow-up respondents appeared to have similar demographic characteristics to the original NSDUH respondents. Estimates of drug use for follow-up respondents showed patterns that were similar to the regular NSDUH respondents. Another finding was that among those who participated in the follow-up survey, one-third were judged by FIs to have participated in the follow-up because they were unavailable for the main survey request. Finally, 27 percent were judged to have been swayed by the incentive, and another 13 percent were judged to have participated in the follow-up due to the shorter instrument. Overall, the results did not demonstrate definitively either the presence or absence of a serious nonresponse bias in the 1990 NSDUH. Based on these findings, no changes were made to NSDUH procedures.

CBHSQ produced a report to address the nonresponse patterns obtained in the 1999 NSDUH (Eyerman et al., 2002). In 1999, the NSDUH changed from PAPI to CAI instruments. The report was motivated by the relatively low response rates in the 1999 NSDUH. The analyses presented in this report were produced to help provide an explanation for the rates in the 1999 NSDUH and guidance for the management of future projects. The report describes NSDUH data collection patterns from 1994 through 1998. It also describes the data collection process in 1999 with a detailed discussion of design changes, summary figures and statistics, and a series of logistic regressions comparing 1998 with 1999 nonresponse patterns. The results of this study are consistent with conventional wisdom within the professional survey research field and general findings in survey research literature: the nonresponse can be attributed to a set of FI influences, respondent influences, design features, and environmental characteristics. The nonresponse followed the demographic patterns observed in other studies, with urban and high crime areas having the worst rates. Finally, efforts taken in 1999 to improve the response rates were effective. Unfortunately, the tight labor market combined with the large increase in sample size caused these efforts to lag behind the data collection calendar. The authors used the results to generate several suggestions for the management of future projects. No major changes were made to NSDUH as a result of this research, although it—along with other general survey research findings—has led to minor tweaks to respondent cooperation approaches.

In 2004, focus groups were conducted with NSDUH FIs on the topic of nonresponse among the 50 or older age group to gather information on the root causes for differential response by age. The study examined the components of nonresponse (refusals, noncontacts, and other incompletes) among the 50 or older age group. It also examined respondent, environmental, and FI characteristics in order to identify the correlates of nonresponse among the 50 or older group, including relationships that are unique to this group. Finally, they considered the root causes for differential nonresponse by age, drawing from focus group sessions with NSDUH FIs on the topic of nonresponse among the 50 or older group. The results indicated that the high rate of nonresponse among the 50 or older age group was primarily due to a high rate of refusals, especially among sample members aged 50 to 69, and a high rate of physical and mental incapability among those 70 or older. It appeared that the higher rate of refusals among the 50 or older age group may, in part, have been due to fears and misperceptions about the survey and FIs' intentions. It was suggested that increased public awareness about the study may allay these fears (Murphy et al., 2004).

In 2005, Murphy et al. sought a better understanding of nonresponse among the population 50 or older in order to tailor methods to improve response rates and reduce the threat of nonresponse error (Attachment W, Nonresponse among Sample Members Aged 50 and Older Report). Nonresponse to the NSDUH is historically higher among the 50 or older age group than lower age groups. Focus groups were again conducted, this time with potential NSDUH respondents to examine the issue of nonresponse among persons 50 or older. Participants in these groups recommended that the NSDUH contact materials focus more on establishing the legitimacy of the sponsoring and research organizations, clearly conveying the survey objectives, describing the selection process, and emphasizing the importance of the selected individual’s participation.

Another examination of nonresponse was done in 2005. The primary goal was to develop a methodology to reduce item nonresponse to critical items in the ACASI portion of the NSDUH questionnaire (Caspar et al., 2005). Respondents providing "Don't know" or "Refused" responses to items designated as essential to the study's objectives received tailored follow-up questions designed to simulate FI probes. Logistic regression was used to determine what respondent characteristics tended to be associated with triggering follow-up questions. The analyses showed that item nonresponse to the critical items is quite low, so the authors caution the reader to interpret the data with care. However, the findings suggest the follow-up methodology is a useful strategy for reducing item nonresponse, particularly when the nonresponse is due to "Don't know" responses. In response, follow up questions were added to the survey and asked when respondents indicated that they did not know the answer to a question or refused to answer a question. These follow-up items encouraged respondents to provide their best guess, or presented an assurance of data confidentiality in order to encourage response.

Biemer and Link (2007) conducted additional nonresponse research to provide a general method for nonresponse adjustment that relaxed the ignorable nonresponse assumption. Their method, which extended the ideas of Drew and Fuller (1980), used level-of-effort (LOE) indicators based on call attempts to model the response propensity. In most surveys, call history data are available for all sample members, including nonrespondents. Because the LOE required to interview a sample member is likely to be highly correlated with response propensity, this method is ideally suited for modeling the nonignorable nonresponse. The approach was first studied in a telephone survey setting and then applied to data from the 2006 NSDUH, where LOE was measured by contact attempts (or callbacks) made by FIs.

The callback modeling approach investigation confirmed what was known from other studies on nonresponse adjustment approaches (i.e., there is no uniformly best approach for reducing the effects of nonresponse on survey estimates). All models under consideration were the best in eliminating nonresponse bias in different situations using various measures. Furthermore, possible errors in the callback data reported by FIs, such as underreporting of callback attempts, raise concerns about the accuracy of the bias estimates. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to apply uniform callback reporting procedures amongst the large NSDUH interviewing staff, which is spread across the country. An updated study of the callback modeling approach was completed in 2013 and similar conclusions were reached on errors in the callback data reported by FIs (Biemer, Chen, and Wang, 2013). For these reasons, the callback modeling approach was not implemented in the NSDUH nonresponse weighting adjustment process (Biemer and Link, 2007; Biemer, Chen, and Wang, 2013).

ONDCP has repeatedly emphasized that trends be maintained for three modules in the survey: Alcohol, Tobacco, and Marijuana. Therefore, all survey protocols administered before these modules needed to remain relatively unchanged. SAMHSA shares OMB’s concerns about decreasing response rates. Initial plans were assessed to adjust the incentive to $40 for the 2015 NSDUH. However, given the experience with the unexpected break in trends when the original incentive was introduced in 2002 (despite a field test indicating continuity), and ONDCP’s request to maintain trends on those three modules, SAMHSA has retained the $30 incentive.

Methods to assess nonresponse bias vary and each has its limitations (Groves, 2006). Some methods include follow-up studies, comparisons to other surveys, comparing alternative post-survey adjustments to examine imbalances in the data, and analysis of trend data that may suggest a change in the characteristics of respondents. When comparing to other surveys such as the Monitoring the Future (MTF), we have found comparable trends even though the estimates themselves differ in magnitude (mostly due to differences in survey designs). For example, trends in NSDUH and MTF cigarette use between 2002 and 2012 show a consistent pattern:

http://samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2012SummNatFindDetTables/NationalFindings/NSDUHresults2012.htm#fig8.1.

Using a different approach, information in a NSDUH report suggests that alternative weighting methods based on variables correlated with nonresponse were not better or only slightly better than the current weighting procedure: http://samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/NSDUHCallbackModelReport2013.pdf .

In April 2015, a study was conducted on the potential for declines in the screening response rate to introduce nonresponse bias for trend estimates. The primary purpose of these analyses was to examine any potential impact of steep declines in the screening response rate observed in 2013 and the first three quarters of 2014 on nonresponse bias. The common approach in these analyses was to examine changes over time from 2007 through 2014, rather than estimating nonresponse bias only at one point in time.

The first analysis evaluated whether there were any apparent changes in the reliance on variables in the screening nonresponse weighting adjustment models over time.

The second analysis used household level demographic estimates from the Current Population Survey (CPS) as a “gold standard” basis of comparison for similar estimates constructed from the NSDUH screening. CPS quarterly estimates related to household size, age, gender, race, Hispanic origin and active military duty status were compared with NSDUH selection weighted estimates (i.e. NSDUH base weights that do not adjust for nonresponse and are not adjusted to population control totals).

The third analysis used data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) to compare estimates of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption over time with estimates from NSDUH. Overall, the results of these analyses provided little evidence of any systematic change in trend estimates during a period of relatively steeper declines in screening response rates. In January 2018, NSDUH benchmark comparisons with CPS and NHIS were reproduced through the 2016 survey year which confirmed earlier findings.

SAMHSA is currently conducting an analysis which examines the potential for nonresponse bias by examining correlations between response propensities of participating in the survey and prevalence rates for survey outcome measures using small area estimation (SAE) methods. The analysis will pool three years of NSDUH data (2014 to 2016) and fit SAE models using the pooled data to produce state sampling region (SSR) level estimates for:

1) dwelling unit (DU) screening response propensities;

2) person-level (or interview-level) response propensities; and

3) outcome measures from the survey.

Response propensities defined at the SSR level will be used to group SSRs into deciles from lowest to highest; for each category, the prevalence rate of the outcome measure can be calculated and used to examine the correlation between response propensities and prevalence rates. Nonresponse weighting adjustments can reduce nonresponse bias if the weights are correlated with response propensities. The goal of such weighting is to reduce the potential for nonresponse bias by reducing the correlation between response propensities and survey outcome measures. This analysis is expected to be completed by October 2018.

4. Tests of Procedures

Since there are no planned additions to the 2019 data collection protocol, field testing will not occur. All of the recent significant modifications to the questionnaire have already been tested under NSDUH Methodological Field Tests generic OMB clearance (OMB No. 0930-0290) and the Questionnaire and Dress Rehearsal Field Tests (OMB No. 0930-0334).

5. Statistical Consultants

The basic NSDUH design was reviewed by statistical experts, both within and outside SAMHSA. Statistical experts reviewing portions of prior NSDUHs designs include William Kalsbeek, PhD, University of North Carolina; Robert Groves, PhD, Georgetown University; and Michael Hidiroglou, PhD, Statistics Canada. Monroe Sirken, PhD, National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS); Arthur Hughes, CBHSQ, SAMHSA (retired); James Massey, PhD, (deceased) also of NCHS; Douglas Wright, CBHSQ, SAMHSA (retired); and Joseph Gfroerer, CBHSQ, SAMHSA (retired) were consulted on the 1992 and subsequent survey designs. Peter Tice, CBHSQ, SAMHSA is the Government Project Officer responsible for overall project management, (240) 276-1254. Jonaki Bose, Chief, Population Surveys Branch, Division of Surveillance and Data Collection, CBHSQ, SAMHSA is the primary mathematical statistician, (240) 276-1257. RTI senior statisticians contributing to the design are Ralph Folsom, PhD (retired), Rachel Harter, PhD, and Akhil Vaish, PhD.

The 2018–2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health contract was awarded to RTI International (RTI) on December 15, 2016, with only the Base Award (2018 NSDUH) exercised initially. The 2019 NSDUH was exercised by SAMHSA for RTI on October 1, 2017. Contractor personnel will implement the sample design; recruit FSs and FIs; train FIs; conduct data collection; conduct data receipt, editing, coding, and keying; conduct data analysis; and develop and deliver to CBHSQ statistical reports and data files. CBHSQ will provide direction and review functions to the Contractor. Data collection will be conducted throughout the 2019 calendar year.

Appendix A

Potential NSDUH Consultants

a. Consultants on NSDUH Design

Michael Arthur, PhD, Research Associate Professor (206) 685-3858

Social Development Research Group, School of Social Work

University of Washington

Raul Caetano, M.D., PhD, Dean (214) 648-1080

School of Health Professions

University of Texas Southwestern

John Carnevale, PhD, President and CEO (301) 977-3600

Carnevale Associates, LLC

William D. Kalsbeek, PhD, Professor/Founder (919) 962-3249

Carolina Survey Research Laboratory, Biostatistics

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Graham Kalton, PhD, (301) 251-8253

Chairman of the Board

Westat

Philip Leaf, PhD, Professor (410) 955‑3962

Department of Mental Health Policy and Management

School of Public Health

Johns Hopkins University

Patrick O’Malley, PhD, Senior Research Scientist (734) 763-5043

Population Studies Center, The Institute for Social Research

University of Michigan

Peter Reuter, PhD, Professor (301) 405-6367

School of Public Policy and Department of Criminology

University of Maryland

b. NSDUH Consultant for the Tobacco Module

Gary A. Giovino, PhD, Professor and Chair (716) 845-8444

Department of Health Behavior

University at Buffalo - SUNY

c. NSDUH Consultants for Mental Health Modules

Margarita Alegria, Director (617) 503-8447

Center for Multicultural Mental Health Research, Department of Psychiatry

Harvard Medical School

Paul C. Beatty, PhD, Chief (301) 763-5001

Center for Survey Measurement, US Census Bureau

Maureen Boyle, PhD, Branch Chief

Science Policy Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse (301) 443-6071

Jeffrey Buck, PhD (301) 443-0588

Director of Office of Managed Care, Center for Mental Health Services

Alan J. Budney, PhD, Professor (603) 653-1821

Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth University

Michael Cala, PhD (202) 395-5205

Office of Research and Data Analysis

White House Office of National Drug Control Policy

Glorisa Canino, PhD, Director (787) 754-8624

Behavioral Sciences Research Institute, University of Puerto Rico

Wilson M. Compton, MD, Deputy Director (301) 443-6480

National Institute on Drug Abuse

Lori Ducharme, PhD, Program Director (301)451-8507

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcholism

Marilyn Henderson (retired) (301) 443-2293

Center for Mental Health Services

Kimberly Hoagwood, PhD, Vice Chair for Research (410) 573-0228

NYU Child Study Center, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

NYU

Ronald C. Kessler, PhD, Professor (617) 423-3587

Department of Health Care Policy

Harvard Medical School

Christopher P. Lucas, MD, Clinical Associate Professor (212) 263-2499

NYU Study Center, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

NYU

Michael Schoenbaum, PhD (301) 435-8760

Senior Advisor for Mental Health Services,

Epidemiology and Economics

National Institute of Mental Health

Philip Wang, MD, PhD, Deputy Director (301) 443-6233

National Institute of Mental Health

Gordon Willis, PhD, Cognitive Psychologist (240) 276-6788

Office of the Associate Director of the Applied Research Program

National Cancer Institute

Appendix B

Feedback on medication-assisted treatment (MAT) questions

Agency |

Recommendation |

Response |

ONDCP |

Questions need to capture respondent use of medical marijuana |

Respondents can report medical marijuana use under “other, specify.” Analysts can chose to include or exclude those responses in their analysis.

|

|

Add text repeating the phrase: “prescribed by doctor or other health care professional.”

Otherwise, respondent maybe self-medicating |

The preamble includes this phrase so in order to reduce cognitive burden, we did not repeat the phrase in the question. |

|

Does question ALMATOTHA2 allow respondents to report illicit drugs like marijuana? |

Yes since it is an open-ended question. Analysts can chose to include or exclude those responses in their analysis.

|

|

Consider including question that captures medication that respondents might have obtained from friend, or family, or somewhere else |

The new questions focus on medication prescribed from a doctor. If they are using these types of medications illicitly, they can report this in the prescription drug module.

|

NIDA |

Consider including pictures of pills and describing injections and implants. Without seeing the visual, patients sometimes don’t know what they are taking. |

We have included text mentioning pills, implants, and injections in the question as appropriate.

We considered including images, however, given the rapidly changing nature of the market, we did not include images. |

|

Add the phrase: “(with or with naloxone)” after buprenorphine, in order to capture both generic forms

|

We have added similar text as appropriate |

|

Add measures of adherence |

While the concept of adherence is an important one, it is also complicated. Measuring this concept would require a large number of in-depth questions, which are beyond the scope of this survey. |

|

Be clear and consistent with pharmacological names across all questions |

We have edited the questions as appropriate |

|

Add the phrase “approximately” to frequency of use questions |

We did not add this phrase since this differs from the NSDUH format for other frequency of use questions |

NIAAA |

Reorder drugs to include generic and then brand name consistently |

We have made this change |

References

Biemer, P., & Link, M. (2007). Evaluating and modeling early cooperator bias in RDD surveys. In Lepkowski, J. et al. (Eds.), Advances in telephone survey methodology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Biemer, P., Chen, P., and Wang, K. (2013). Incorporating level of effort paradata in the NSDUH nonresponse adjustment process. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral, Health Statistics and Quality.

Caspar, R.A. (1992). A follow-up study of nonrespondents to the 1990 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. In Proceedings of the1992 American Statistical Association, Survey Research Section, Boston, MA (pp. 476-481). Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association.

Caspar, R. A., Penne, M. A., & Dean, E. (2005). Evaluation of follow-up probes to reduce item nonresponse in NSDUH. In J. Kennet & J. Gfroerer (Eds.), Evaluating and improving methods used in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 05-4044, Methodology Series M-5, pp. 121-148). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies.

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2013). Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings (HHS Publication No. SMA 13-4795, NSDUH Series H-46). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Colliver, J.D., Kroutil, L.A., Dai, L., & Gfroerer, J.C. (2006). Misuse of prescription drugs: Data from the 2002, 2003, and 2004 National Surveys on Drug use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 06-4192, Analytic Series A-28.) Rockville, MD; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies.

Dahlhamer, J., Cain, V., Cynamon, M., Galinsky, A., Joestl, S., Mandans, J., Miller, K. (2013). Asking about Sexual Identity in the National Health Interview Survey: An Experimental Mode Comparison. National Center for Health Statistics.

de Leeuw, E., Hox, J., & Kef, S. (2003). Computer-assisted self-interviewing tailored for special populations and topics. Field Methods, 15(3), 223-251. doi: 10.1177/1525822X03254714

Drew, J.H. and Fuller, W.A. (1980). Modeling Nonresponse in Surveys with Callbacks. Proceedings of the American Statistical Association, Survey Research Methods Section, 639–642.

Eyerman, J., Odom, D., Butler, D., Wu, S., and Caspar, R. (2002). Nonresponse in the 1999 NHSDA. In J. Gfroerer, J. Eyerman, & J. Chromy (Eds.), Redesigning an ongoing national household survey: Methodological issues (HHS Publication No. SMA 03-3768). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies.

Gfroerer, J., Wright, D., & Kopstein, A. (1997). Prevalence of youth substance use: The impact of methodological differences between two national surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 47, 19–30.

Groves, R. M., and M.P. Couper. (1998). Nonresponse in Household Interview Surveys. New York: Wiley.

Groves, R. M. (2006). Nonresponse Rates and Nonresponse Bias in Household Surveys, Public Opinion Quarterly, 70(5), pp. 646-675.

Groves, R. (1989). Survey Errors and Survey Costs. New York: Wiley.

Grucza, R. A., Abbacchi, A. M., Przybeck, T. R., & Gfroerer, J. C. (2007). Discrepancies in estimates of prevalence and correlates of substance use and disorders between two national surveys. Addiction, 102, 623-629.

Hennessy, K., & Ginsberg, C. (Eds.). (2001). Substance use survey data collection methodologies [Special issue]. Journal of Drug Issues, 31(3), 595–727.

Huang, B., Dawson, D. A., Stinson, F. S., Hasin, D. S., Ruan, W. J., Saha, T. D., Smith, S. M., Goldstein, R. B., & Grant, B. F. (2006). Prevalence, correlates and comorbidity of nonmedical prescription drug use and drug use disorders in the United States: Results of the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67, 1062-1073.

Miller, J. W., Gfroerer, J. C., Brewer, R. D., Naimi, T. S., Mokdad, A., & Giles, W. H. (2004). Prevalence of adult binge drinking: A comparison of two national surveys. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27, 197-204.

Murphy, J., Eyerman, J., & Kennet, J. (2004). Nonresponse among persons aged 50 or older in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. In S. B. Cohen & J. M. Lepkowski (Eds.), Eighth Conference on Health Survey Research Methods (HHS Publication No. PHS 04-1013, pp. 73-78). Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

National Research Council. (2013). Nonresponse in Social Science Surveys: A Research Agenda. Roger Tourangeau and Thomas J. Plewes, Editors. Panel on a Research Agenda for the Future of Social Science Data Collection, Committee on National Statistics. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Tourangeau, R., & Smith, T. W. (1996). Asking sensitive questions: The impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context. Public Opinion Quarterly, 60(2), 275‑304.

Tourangeau, R., & Yan, T. (2007). Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin, 133(5), 859-883.

Wright, D., Bowman, K., Butler, D., & Eyerman, J. (2005). Non-response bias from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse incentive experiment. Journal for Social and Economic Measurement, 30(2-3), 219-231.

Attachments

Attachment A. Sample Design

Attachment B. CAI Questionnaire

Attachment C. Lead Letter

Attachment D. Question & Answer Brochure

Attachment E. Tablet Screening Video Scripts

Attachment F. Contact Cards – Sorry I Missed You Card and Appointment Cards

Attachment G. Study Description

Attachment H. Introduction and Informed Consent Scripts

Attachment I. Screening Questions

Attachment J. Unable-to-Contact, Controlled Access, and Call-Me Letters

Attachment K. Refusal Letters

Attachment L. Interview Incentive Receipt

Attachment M. Federalwide Assurance

Attachment N. Showcard Booklet

Attachment O. Parental Introductory Script

Attachment P. Confidentiality Agreement and Data Collection Agreement

Attachment Q. Quality Control Form

Attachment R. NSDUH Highlights and Newspaper Articles

Attachment S. Certificate of Participation

Attachment T. CATI Verification Scripts

Attachment U. Quality Control Letter

Attachment V. Doorperson Card

Attachment W. Nonresponse among Sample Members Aged 50 and Older Report

1 http://aspe.hhs.gov/datacncl/standards/ACA/4302/index.shtml

2 Prior to 2002, the NSDUH was referred to as the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA). In this document the term NSDUH is used for all survey years.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Grace Medley |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-15 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy