HH Survey Supporting Statement A - Revised V2

HH Survey Supporting Statement A - Revised V2.docx

Home Health (HH) National Provider Survey (CMS-10688)

OMB: 0938-1364

Measure & Instrument Development and Support (MIDS) Contractor:

Impact Assessment of CMS Quality and Efficiency Measures

Supporting Statement A:

OMB/PRA Submission Materials for the

National

Provider Survey of Home Health Agencies (CMS 10688; OMB 0938-NEW)

CONTRACT NUMBER: HHSM-500-2013-13007I

TASK ORDER: HHSM-500-T0002 SUBMITTED: SEPTEMBER 18, 2018 REVISED:

NONI BODKIN, PHD, MIDS CONTRACTING OFFICER’S REPRESENTATIVE (COR) CENTERS FOR MEDICARE & MEDICAID SERVICES (CMS)

7500 SECURITY BOULEVARD, MAIL STOP: S3-02-01 BALTIMORE, MD 21244-1850 NONI.BODKIN@CMS.HHS.GOV

Impact Assessment of CMS Quality and Efficiency Measures

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A1. Circumstances Making the Collection of Information Necessary 4

A2. Purpose and Use of the Information Collection 5

A3. Use of Improved Information Technology and Burden Reduction 8

A4. Efforts to Identify Duplication and Use of Similar Information 8

A5. Impact on Small Businesses or Other Small Entities 9

A6. Consequences of Collecting the Information Less Frequently 9

A7. Special Circumstances Relating to the Guidelines of 5 CFR 1320.5 9

A8. Comments in Response to the Federal Register Notice and Efforts to Consult Outside the Agency 9

A9. Explanation of Any Payment or Gift to Respondents 10

A10. Assurance of Confidentiality Provided to Respondents 10

A11. Justification for Sensitive Questions 11

A12. Estimates of Annualized Burden Hours and Costs 11

A13. Estimates of Other Total Annual Cost Burden to Respondents and Record Keepers 12

A14. Annualized Cost to Federal Government 12

A15. Explanation for Program Changes or Adjustments 12

A16. Plans for Tabulation and Publication and Project Time Schedule 12

A17. Reason(s) Display of OMB Expiration Date Is Inappropriate 13

OMB/PRA Submission Materials for the i

National Provider Survey of Home Health Agencies

SUPPORTING STATEMENT A – JUSTIFICATION FOR THE NATIONAL PROVIDER SURVEY OF HOME HEALTH AGENCIES

Background

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) promotes quality of health care and improved outcomes for beneficiaries through an array of programs and initiatives that gauge performance by health care providers. In using quality measures across these programs, CMS seeks to achieve a high-quality, sustainable health care system and put patients at the center of everything it does.

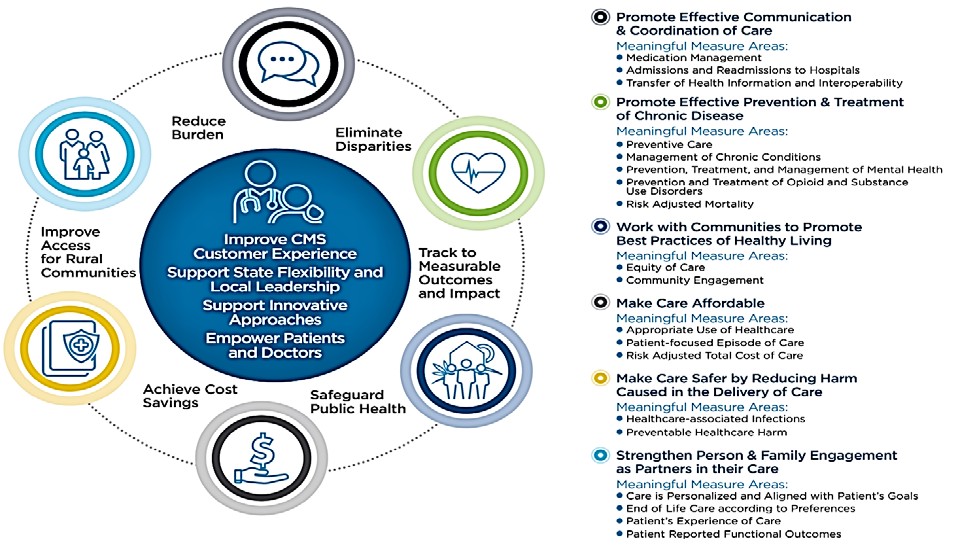

To better target the set of quality and efficiency measures used to assess provider performance, CMS in 2017 launched the Meaningful Measures initiative, the purpose of which is “to improve outcomes for patients, their families, and providers while also reducing burden on clinicians and providers.”1 The Meaningful Measures framework (Figure 1) guides CMS toward measurement activities that are the most critical to providing high-quality care and improving outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries.

Figure 1. Meaningful Measures Framework

CMS analyzes trends and disparity data across hundreds of measures and reports patient and cost-avoided impacts of selected quality measures in the National Impact Assessment of CMS Quality Measures Report (Impact Assessment Report). Section 1890A(a)(6) of the Social Security Act (the Act) requires the Secretary of HHS every three years to assess the quality and efficiency effects of the use of endorsed measures in specific Medicare quality reporting and

1 https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/CMS-Quality- Strategy.html

incentive programs. The 2012, 2015, and 2018 reports summarize the findings of the first three assessments conducted by CMS.2,3,4

A key aspect of evaluating the impact of CMS measures is determining how health care providers respond to the use of performance measures. The provider perspective can illustrate changes made in response to CMS quality programs and the effects of those changes on improving quality. The 2018 Impact Assessment Report included national surveys and qualitative interviews to assess the types of quality improvement (QI) actions that hospitals and nursing homes had taken in response to CMS’s use of quality measures and to examine whether these actions were associated with better performance on the quality measures.

Work on the hospital and nursing home surveys began as part of the previous Impact Assessment Report. A systematic literature review published as part of the 2015 Impact Assessment Report found that few studies had empirically measured unintended effects or collected evidence to gauge whether such effects had occurred. Furthermore, few studies have assessed how providers respond to quality measurement programs. CMS also lacked data about what features differentiate high- and low-performing providers (e.g., use of clinical decision support or investments in QI staff), a better understanding of which could aid CMS in its work nationally to improve performance and achieve desired outcomes. As a result, surveys were developed to enable CMS to measure these impacts.

Hospital and nursing home settings were selected to be surveyed first because the CMS reporting programs associated with these settings are mature, having been in place since 2004 and 2002, respectively.5,6 The study team drew a nationally representative sample to generate estimates of QI actions taken by hospitals and nursing homes. In addition to assessing QI changes made to improve care, the surveys and qualitative interviews collected information on barriers that providers face in reporting CMS quality measures and in improving performance on the CMS quality measures, as well as burdens related to reporting and unintended consequences associated with implementation of CMS quality measures.

CMS proposes to conduct the next provider surveys in the home health setting, which accounts for about 4.6 percent of Medicare fee-for-service spending. More than 12,200 HHAs

2 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Impact Assessment of Medicare Quality Measures. March 2012. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment- Instruments/QualityMeasures/QualityMeasurementImpactReports.html.

3 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2015 National Impact Assessment of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Quality Measures Report, CMS, Baltimore, Maryland, March 2, 2015. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment- Instruments/QualityMeasures/QualityMeasurementImpactReports.html.

4 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2018 National Impact Assessment of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Quality Measures Report. Baltimore, MD, February 28, 2018. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality- Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/National-Impact-Assessment-of-the-Centers-for-Medicare-and- Medicaid-Services-CMS-Quality-Measures-Reports.html.

5 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Program. Baltimore, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment- Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/HospitalRHQDAPU.html. Accessed December 11, 2017.

6 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Nursing Home Quality Initiative. Baltimore, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment- Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/index.html?redirect=/NursingHomeQualityInits/25_NHQIMDS30.asp. Accessed December 11, 2017.

participated in Medicare in 2016, and about 3.4 million beneficiaries received home health care services at a cost to Medicare of $18.1 billion.7 CMS has used quality measures in the home health setting since 2002 as part of the Home Health Quality Initiative.8 In 2007, HHAs were required to submit data for the purpose of measuring health care quality.9 This pay-for-reporting program is now referred to as the Home Health Quality Reporting Program (HHQRP).10

Despite the established use of CMS quality measures in HHAs, CMS lacks information regarding the impact of their use and how HHAS are responding to them. To address this knowledge gap, CMS directed its contractors, the Health Services Advisory Group, Inc. (HSAG) and the RAND Corporation, to develop a nationally representative survey and a qualitative interview guide to assess the impact of quality measures in the home health setting. The survey and interviews, assuming approval by August 2019, would be fielded from fall 2019 through spring 2020. Results would be published in the 2021 Impact Assessment Report and in peer- reviewed journals to broaden dissemination of findings.

Similar to the hospital and nursing home national provider surveys, the survey and qualitative interviews will seek to determine what changes providers are making in response to the use of performance measures by CMS. The project team will generate the sampling frames after analyzing HHA performance data and other agency characteristics. The HHAs completing the qualitative interview will not be the same as those completing the standardized survey; they are distinct samples. The project team also will oversee the fielding of the surveys (i.e., preparation of the surveys, monitoring response rates, and overseeing the survey vendor). Finally, the project team will conduct qualitative interviews and prepare written summaries of interviews, analyze quantitative data from the structured surveys, and summarize results.

A1. CIRCUMSTANCES MAKING THE COLLECTION OF INFORMATION NECESSARY

The circumstances making the collection of information necessary relate to section 1890A(a)(6) of the Act, which requires CMS to assess the impact of quality and efficiency measures in CMS reporting programs. This request is for review and approval of a survey and qualitative interview guide for the home health setting, which CMS proposes to use to address critical needs regarding the impact of use of quality and efficiency measures in the home health setting, including the burden they impose on HHAs.

An environmental scan of the literature identified critical gaps in knowledge regarding the impact of CMS quality measurement programs on HHAs. Several case studies on QI interventions were published in recent years, but the sole nationally representative survey, (which was limited in focus to HHAs’ adoption of electronic health record [EHR] systems and related technologies) was published over 10 years ago.11 To better understand the knowledge gaps, the project team also conducted interviews with CMS staff responsible for quality measurement and improvement in HHAs, as well as formative interviews with representatives of

7 Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. March 2018 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. 2018. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/-documents-/reports.

8 https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment- Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/HHQIArchives.html.

9 Section 1895(b)(3)(B)(v)(II) of the Act

10 Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. March 2018 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. 2018. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/-documents-/reports.

11 Resnick HE and Alwan M. Use of health information technology in home health and hospice agencies: United States, 2007.

J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010; 17(4):389-95.

HHAs. (Attachment I: Development of the National Provider Survey of Home Health Agencies summarizes the work to develop the survey and interview guide.)

The proposed survey of HHAs examines HHAs’ experiences with reporting CMS measures, challenges they face in improving performance, and undesired effects of measurement. An understanding of these experiences is critical to improving the home health quality measurement programs and informing CMS’s work in support of the Meaningful Measures Initiative.

Although the three Impact Assessment Reports included trends for selected home health measures, CMS also lacks data about what features (e.g., investments in QI staff) differentiate high- and low-performing HHAs. Better understanding of these features could allow HHAs to target QI investments more effectively.

To address the knowledge gaps that were identified, research questions were developed. The two proposed data collection instruments—a structured survey and a qualitative interview guide— address the research question “What changes are HHAs making in response to the use of performance measures by CMS?” This overarching question was translated into five specific research questions that form the content of the surveys and interviews:

What types of QI changes have HHAs made to improve their performance on CMS measures?

If a QI change was made, has it helped the HHA improve its performance on one or more CMS measures?

What challenges or barriers do HHAs face in reporting CMS quality measures?

What challenges or barriers do HHAs face in improving performance on the CMS quality measures?

What unintended consequences do HHAs report associated with implementation of CMS quality measures?

Of note, the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMS Innovation Center) is fielding two surveys in 2018 to evaluate the Home Health Value-Based Payment (HHVBP) model. Section A.4 details how the proposed survey differs from the CMS Innovation Center’s sampling of HHAs in the nine states participating in the HHVBP model and a modified companion survey of HHAs in non-participating states. The proposed survey is national in scope and will assess provider responses to quality measurement consistently across HHAs.

A2. PURPOSE AND USE OF THE INFORMATION COLLECTION

CMS plans to use the findings from surveys and qualitative interviews for multiple purposes. The Impact Assessment Reports provide data to support the measure development lifecycle, which includes identification of measurement gaps, measure development, implementation into programs, and evaluation of the impact of the use of the measures. CMS will use the findings to learn how to better engage HHAs in quality improvement and measure development work. The findings also will aid CMS in efforts to improve the set of quality measures used by HHAs and to identify areas for focused quality improvement activities, such as those provided by the Quality Innovation Network–Quality Improvement Organizations (QIN-QIOs). The QIN-QIOs partner with HHAs to improve patient outcomes by providing free educational resources and individualized assistance. Areas of focus include cardiovascular health, reducing unnecessary hospitalizations, and medication management. We also anticipate that HHAs will use the findings to identify ways to improve quality.

Since 1999, CMS has implemented multiple programs and initiatives that require collecting, monitoring, and public reporting of quality and efficiency measures—in the form of clinical process and outcome, patient experience, and efficiency/resource use measures—to promote improvement in the quality of care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries. Performance measurement is one strategy used to monitor national progress toward measurable health care quality goals and to close the gap between care recommendations based on clinical evidence and actual care delivery. For HHAs, CMS has implemented quality and efficiency measures through the HHQRP12 and the HHVBP model.13 The measures derive from the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS version C-2),14 Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) Home Health Care Survey,15 and Medicare fee-for-service claims data, which are used to construct additional quality measures. The implementation of quality and efficiency measures by CMS has increased the number of providers using evidence-based standards of care.16 To better understand these gains, CMS plans to conduct a survey of HHAs. CMS will publicly report the results from the proposed data collection as part of the 2021 Impact Assessment Report, which will expand upon prior work by providing quantitative and qualitative data specific to the use of home health quality and efficiency measures.

The qualitative interviews and standardized survey will inform CMS about the impact of measures used to assess care in HHAs. The surveys will help CMS understand whether the use of performance measures has been associated with changes in HHA behavior—namely, what QI investments HHAs are making and whether adoption of QI changes is associated with higher performance on the measures. The survey will help CMS identify characteristics associated with high performance, which, if understood, could be used to leverage improvements in care among lower-performing HHAs.

CMS also will learn directly from HHAs what barriers exist related to reporting and implementing the measures, as well as burdens they impose on HHAs. CMS has embraced human-centered design principles in making policy on how providers submit data and otherwise interface with CMS. Information obtained from the HHA surveys and interviews will highlight opportunities for CMS to make quality measurement policies and practices less burdensome and thus to better support providers in delivering high-quality care.

Finally, the surveys and interviews will identify any unintended consequences associated with the HHAs being measured and held accountable for performance, which can trigger further investigation by CMS. An example from the hospital setting illustrates how this information might be used: In interviews that RAND conducted in 2006 in developing a plan for the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing model, hospital quality leaders mentioned that a measure requiring receipt of antibiotics within 4 hours of arrival by patients discharged with a diagnosis

12 https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/Home-Health- Quality-Measures.html.

13 https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/home-health-value-based-purchasing-model.

14 Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS-C2) –The valid OMB control number for this information collection is 0938- 1279; expiration date is 12/31/2019.

15 CAHPS® Home Health Care Survey – The valid OMB control number for this information collection is OMB control number 0938-1066; expiration date is 01/31/2021.

16 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2018 National Impact Assessment of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Quality Measures Report. Baltimore, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/National-Impact- Assessment-of-the-Centers-for-Medicare-and-Medicaid-Services-CMS-Quality-Measures-Reports.html.

.

of pneumonia was leading to unintended effects (i.e., misuse of antibiotics in patients who did not have pneumonia). This information led CMS and the measure developer to further investigate the problem, ultimately leading to a change in the measure’s technical specifications to mitigate the problem.

Once the HHA survey and interview findings are widely disseminated, the results are likely to be useful to HHAs and organizations that represent them, QI organizations, measure developers, health services researchers, and members of Congress. These entities invest significant resources to advance quality measurement and performance, and the information will help them gauge the impact of these efforts and flag areas requiring attention.

Limitations

Data from the qualitative interviews and standardized surveys will provide information on the impact of use of measures by CMS but are associated with limitations.

Given that CMS certifies approximately 12,000 HHAs nationally, qualitative interviews with 40 HHAs will capture the experiences and views of a small fraction of agencies participating in the quality measurement programs, limiting the generalizability of the interview findings. To ensure that the interviews represent a range of views, the sampling will include HHAs that vary by size and participation in the HHVBP model. However, the qualitative interviews are not designed to produce national estimates; rather, the findings may be summarized in a manner such as “Of the 40 HHAs interviewed, 10 felt that ‘X’ was a significant barrier to implementation.”

Gathering qualitative information from HHAs using open-ended response choices allows more in-depth exploration of the topics and is an important way to supplement the national estimates from the structured survey. The interviews will provide greater detail about what HHAs are doing in response to quality measures (e.g., contextual factors influencing their behavior, perceived barriers to improvement, reasons that unintended effects might be occurring, and thoughts about how to modify measures to fix those unintended effects). The findings could identify areas that CMS could explore with HHAs in more depth, as in follow-up studies related to the survey, routine measure maintenance activities, open door forums, public comment periods, and other non-urgent activities. Of note, the survey is not designed to identify urgent issues requiring Special Circumstance responses within 30 days.

Neither the qualitative interviews nor the standardized survey was designed to evaluate a causal connection between the use of CMS measures and actions reported by HHAs. The survey will generate prevalence estimates (e.g., “X% of HHA quality leaders report hiring more staff or implementing clinical decision support tools in response to quality measurement programs”) and allow examination of the associations between actions reported and the performance of HHAs, controlling for other factors (e.g., agency size, for-profit status). In interpreting associations, it will be impossible to exclude the potential unmeasured effects of other factors that may have led HHAs to undertake certain actions in response to being measured on their performance.

However, CMS is the largest payer and the predominant entity measuring performance in the home health setting, as Medicare beneficiaries are the largest fraction of patients within

HHAs.17,18,19 Therefore, it is unlikely that other payers have significantly and independently influenced investments made by HHAs associated with quality measurement.

A3. USE OF IMPROVED INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND BURDEN REDUCTION

The structured survey of HHA quality leaders will apply information technology. The initial or primary mode for fielding the structured survey is Web-based, in which 100% of sampled HHAs will be asked to respond to the survey electronically. Invitations to the survey will be sent via email with a United States Postal Service (USPS) letter as backup should an email address not be available. The email will include an embedded link to the Web survey and a personal identification number (PIN) code unique to each agency. In addition to promoting electronic submission of survey responses, the Web-based survey will:

Allow respondents to print a copy of the survey for review and to assist response;

Automatically implement any skip logic so that questions dependent on response to a gate or screening questions will appear only as appropriate;

Allow respondents to begin the survey, enter responses, and complete remaining items later; and

Allow sections of the survey to be completed by other individuals at the discretion of the sampled agency quality leader.

HHA quality leaders who do not respond to emailed and mailed invitations will receive a mailed version of the survey to complete. The mailed version will follow a standard question layout formatted for manual data entry with clear navigational paths to ensure ease of completion.

The qualitative interviews are not conducive to computerized interviewing or collection and will be conducted by telephone.

A4. EFFORTS TO IDENTIFY DUPLICATION AND USE OF SIMILAR INFORMATION

Two methods were employed in efforts to identify similar information that has been collected: an environmental scan and interviews with staff from multiple CMS divisions.

This data collection effort is designed to meet CMS needs for assessing the impact of quality and efficiency measures in the home health setting. The project team conducted an environmental scan using several bibliographic data sources, including PubMed, Google Scholar, and federal government websites. No recent nationally representative studies of responses to quality measurement in HHAs were found in these bibliographic sources. (See Attachment I for complete findings from the environmental scan.)

However, as noted above, in conducting interviews with CMS staff from other divisions, the project team identified surveys of HHAs being conducted in 2018 by the CMS Innovation Center to assess responses to the HHVBP model. The primary survey included HHAs within nine HHVBP model states; a comparison survey sampled HHAs in the remaining 41 non-model

17 Grabowski DC, Stevenson DG, Huskamp HA, Keating NL. The influence of Medicare home health payment incentives: does payer source matter? INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. 2006; 43 (2):135-149.

18 Han B, McAuley WJ, Remsburg RE. Agency ownership, patient payment source, and length of service in home care, 1992– 2000. The Gerontologist. 2007; 47(4):438-446.

19 Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. March 2018 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. 2018; (9)245. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/-documents-/reports.

states. Additional cross-sectional surveys are planned after payment adjustments are applied if CMS continues the HHVBP model.

The proposed data collection remains necessary because the CMS Innovation Center surveys targets participating HHAs to focus on the specific effects of the HHVBP model rather than on quality measurement in HHAs more generally. By contrast, this survey would examine reporting burdens, difficulties in improving performance on measures, use of EHRs, and unintended consequences of quality measurement. The proposed survey for the Impact Assessment Report will be national in scope, will assess provider responses to quality measurement consistently across HHAs, and will use a different sampling methodology from that used by the CMS Innovation Center. The focus of the data analysis and the presentation of the findings will serve the purpose of assessing the impact of quality measures for the Impact Assessment Report. We also propose to conduct qualitative interviews with quality leaders from HHAs that cover the same topics as the structured survey. These qualitative interviews, unlike the CMS Innovation Center surveys, will allow the researchers to probe for clarification and quality leaders from the HHAs to express answers in their own words.

Given the lack of information on HHA responses to quality measurement in recent published literature and the different focus of the CMS Innovation Center survey, the proposed data collection will provide critical information that cannot be obtained from any other source.

A5. IMPACT ON SMALL BUSINESSES OR OTHER SMALL ENTITIES

This data collection is anticipated to have minimal impact on small businesses. Survey respondents represent HHAs participating in the HHQRP that report the OASIS measures. These scores are reported on Home Health Compare. As classified according to definitions provided in OMB form 8320 and by the Small Business Administration,21 most responding HHAs would likely qualify as small businesses or entities. However, testing found that the survey and interview each took an hour to complete, minimizing the impact on respondents with limited staff and resources, such as small businesses.

A6. CONSEQUENCES OF COLLECTING THE INFORMATION LESS FREQUENTLY

This is a one-time data collection conducted in support of the CMS 2021 Impact Assessment Report.

A7. SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCES RELATING TO THE GUIDELINES OF 5 CFR 1320.5

There are no special circumstances associated with this information collection request.

A8. COMMENTS IN RESPONSE TO THE FEDERAL REGISTER NOTICE AND EFFORTS TO CONSULT OUTSIDE THE AGENCY

The 60-day Federal Register notice was published on 11/15/2018 (83 FR 57490). CMS received comments from a Nurse Practitioner Group and a Home Care Association. In response to these

20 A small entity may be (1) a small business, which is deemed to be one that is independently owned and operated and that is not dominant in its field of operation; (2) a small organization that is any not-for-profit enterprise that is independently owned and operated and is not dominant in its field; or (3) a small government jurisdiction, which is a government of a city, county, town, township, school district, or special district with a population of less than 50,000. (https://www.opm.gov/forms/pdfimage/omb83-i.pdf)

21 The Small Business Administration classified home health care entities with average annual receipts of no more than

$15 million as small businesses in 2017. (https://www.sba.gov/document/support--table-size-standards)

comments, the Home Health Agency Qualitative Interview Guide (Attachment III) was modified to include a question regarding nurse practitioners, and Supporting Statement B was modified to include new power calculations regarding detection of differences between home health agencies located in urban areas and those located in small towns or rural areas.

The 30-day Federal Register notice was published on XX, 2019. (Results of the comment period will be added after both 60- and 30-day comment periods are completed)

In addition to having the opportunity to comment in response to Federal Register notices, HHAs were involved in developing the qualitative interview guide and the standardized survey. As part of the development work, the project team used feedback obtained from HHAs during formative interviews. The project team then cognitively tested the draft surveys with nine HHAs in June through August 2018, and changes were made in response to the respondents’ comments. (See Attachment I for additional details.) The testing assessed respondents’ understanding of the draft survey, interview guide items, and key concepts, enabling the project team to identify and revise problematic terms, items, or response options.

HHA respondents indicated that the content was important and relevant to their agencies and that they could answer the questions. The HHA respondents had knowledge of the CMS measures and provided comments (both positive and negative) about the measures and measurement programs, which the survey and interview guides seek to elicit. The respondents offered suggestions to improve the clarity of questions and the ease of response. They also provided terminology commonly used in HHAs, which informed the wording of the questions.

Additionally, CMS staff directly responsible for quality measurement in HHAs reviewed the data collection approach and instruments and had the opportunity to delete unnecessary content, clarify survey wording, and reduce overlap between this survey and the CMS Innovation Center surveys. For more details on the development process and the types of changes made in response to comments from affected stakeholders, please refer to Attachment I.

A9. EXPLANATION OF ANY PAYMENT OR GIFT TO RESPONDENTS

No gifts or incentives will be given to respondents for participation in the survey. Results from the survey will be published as part of the 2021 Impact Assessment Report that will be publicly posted on the CMS website.

A10. ASSURANCE OF CONFIDENTIALITY PROVIDED TO RESPONDENTS

All persons who participate in this data collection, through either the qualitative interviews or the standardized survey, will be assured that the information they provide will be kept private to the fullest extent allowed by law. Informed consent from participants will be obtained to ensure that they understand the nature of the research being conducted and their rights as survey respondents. Respondents who have questions about the consent statement or other aspects of the study will be instructed to call a specified contact person, such as the project leader or principal investigator.

The qualitative interview includes an informed consent and confidentiality script that will be read before any interview. This script is found in the data collection materials contained in Attachment III: Home Health Agency Qualitative Interview Guide. In addition, confidentiality information will be sent in the email inviting them to participate in the interview, found in Attachment IV: Interview Recruitment Email or Letter.

The HHA quality leaders who participate in the standardized survey will receive informed consent and confidentiality information on the first page of the electronic or paper instrument (Attachment II: HHA Survey Instrument) and via emails and letters inviting them to participate in the Web and mail survey, found in Attachments V, VI, VII, and VIII.

The study will have a data safeguarding plan to further ensure the privacy of the information collected. For the online survey and qualitative interviews, a data identifier will be assigned to each respondent. For the qualitative interviews, contact information that could be used to link individuals with their responses will be removed from all interview instruments and notes. All interview notes and recordings will be stored on a server where access will be restricted to project team members directly involved in the interviews. Recordings will be destroyed once notes are reviewed, finalized, and analyzed. The data from the qualitative interviews will not contain any direct identifiers and will be stored on encrypted media under the control of the interview task lead. Files containing contact information used to conduct qualitative interviews may also be stored on staff computers or in staff offices following procedures reviewed and approved by the project team’s institutional review board.

The standardized survey will be administered by an experienced survey vendor. All electronic files directly related to the administration of the survey will be stored on a restricted drive of the vendor’s secure local area network. Access to data will be limited to those employees identified by the vendor’s chief security officer as working on the specific project. Files containing survey response data and information revealing sample members’ individual identities will not be stored together on the network. No single file will contain both a member’s response data and his or her contact information.

The project team’s staff and the data collection vendor will destroy participant contact information once all qualitative and standardized survey data are collected and the associated data files are reviewed, finalized, and analyzed by the project team.

A11. JUSTIFICATION FOR SENSITIVE QUESTIONS

The survey does not include any questions of a sensitive nature.

A12. ESTIMATES OF ANNUALIZED BURDEN HOURS AND COSTS

Table 1 shows the estimated annualized burden and cost for the respondents’ time to participate in this data collection. These burden estimates are based on tests of data collection conducted on nine or fewer entities. The burden estimates represent time that will be spent by respondents completing the survey. Initial work to identify the correct individual to complete the survey within each HHA was not included in this estimate. As indicated below, the annual total burden hours are estimated to be 1,040 hours, assuming a response rate of 44%.22 The annual total cost associated with the annual total burden hours is estimated to be $123,448.

22 Supporting Statement B contains the justification for the assumption of a 44% response rate.

Table 1: Estimated Annualized Burden Hours and Cost – National Provider Survey of Home Health Agencies

Collection Task |

Number of Respondents |

Number of Responses per Respondent |

Hours per Response |

Total Burden hours |

Average Hourly Wage Rate* |

Total Cost Burden |

Semi-Structured Interview |

40 |

1 |

1 |

40 |

$118.70 |

$4, 748 |

Standardized Survey |

1,000 |

1 |

1 |

1,000 |

$118.70 |

$118,700 |

Total |

|

|

|

1,040 |

|

$123,448 |

*Based upon mean hourly wages for General and Operations Managers, “National Compensation Survey: All United States May 2017,” U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, available at https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes111021.htm; accessed August 8, 2018. The base hourly wage rates have been doubled to account for benefits and overhead.

A13. ESTIMATES OF OTHER TOTAL ANNUAL COST BURDEN TO RESPONDENTS AND RECORD KEEPERS

There are no capital costs or other annual costs to respondents and record keepers.

A14. ANNUALIZED COST TO FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

Table 2 details estimated costs for sampling, data collection, analysis, and reporting of survey findings for the HHA quality leader data collection (both qualitative interviews and a standardized survey) is $1,356,820.

Table 2: HHA Survey Estimated Cost Breakdown

Task |

Cost |

Verification of HHA contact and identification of respondent for standardized survey |

$60,376 |

Verification of HHA contact information and scheduling of semi-structured interviews |

$21,491 |

Oversight HHA survey vendor |

$6,052 |

Survey vendor costs |

|

Equipment/supplies |

$17,413 |

Printing |

$2,178 |

Support staff |

$23,027 |

Overhead |

$31,800 |

Project team to prepare survey for printing and proofing, prepare the sample file, conduct qualitative interviews, manage the qualitative and quantitative survey data collection, data cleaning, analysis, report production, and revisions |

$1,168,859 |

Project team total |

$1,331,196 |

CMS staff oversight |

$25,624 |

Total Cost to Federal Government |

$1,356,820 |

A15. EXPLANATION FOR PROGRAM CHANGES OR ADJUSTMENTS

This is a new information collection request. The changes made to the interview guide in response to a comment received during the 60-day comment period will not increase provider burden because the interview will be limited to one hour.

A16. PLANS FOR TABULATION AND PUBLICATION AND PROJECT TIME SCHEDULE

Data collection is anticipated to begin in late fall 2019 and conclude in February 2020. Analyses of these data will occur during February through April 2020 to contribute to the draft summary report delivered to CMS in May 2020. The final summary of survey results and qualitative

interviews will be delivered to CMS no later than July 2020 for inclusion in the 2021 Impact Assessment Report. Based on this timeline, the data collection would need to be approved by August 2019 to allow the survey results to be incorporated into the 2021 Impact Assessment Report.

Table 3: Timeline of Survey Tasks and Publication Dates

Activity |

Proposed Timing |

Finalize field materials |

August 2019–November 2019 |

Identify target respondent |

August 2019–November 2019 |

Field surveys and conduct qualitative interviews |

November 2019–February 2020 |

Analyze data |

February 2020–April 2020 |

Draft chapter summarizing findings for 2021 Impact Report |

April 2020–June 2020 |

Integrate findings into 2021 Impact Report |

June 2020–July 2020 |

Submit final version of Impact Report to CMS |

July 2020 |

CMS QMVIG Internal Review |

July–August 2020 |

Submit document for SWIFT Clearance |

August 30, 2020 |

Publish 2021 Impact Report |

March 1, 2021 |

Prepare additional products to disseminate findings |

December 2020–June 2021 |

In addition to summarizing the findings for the 2021 Impact Assessment Report, CMS will develop timelines for broad dissemination of the results, which may include peer-reviewed publications. Such publications will increase the impact of this work by exposing the results to a broader audience of HHA administrators and policymakers. The publication of the 2021 Impact Assessment Report will result in additional dissemination through press releases, open door calls, and other events.

A17. REASON(S) DISPLAY OF OMB EXPIRATION DATE IS INAPPROPRIATE

CMS offers no reasons not to display the expiration date for OMB approval of this information collection. CMS proposes to display the date on the document that details the topics addressed in the qualitative interview and on the standardized survey (on the introductory screen of the Web version and on the front cover of the mailed version). The requested expiration date is 36 months from the approved date.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| File Title | Home Health Survey Supporting Statement A |

| Subject | OMB/PRA Submission Materials for the National Provider Survey of Home Health Agencies |

| Author | HSAG |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-20 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy