Part C-1 Item Justification Update

Part C-1 SSOCS 2018 & 2020 Update.docx

School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS) 2018 and 2020 Update

Part C-1 Item Justification Update

OMB: 1850-0761

School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS) 2018 and 2020 Update

OMB# 1850-0761 v.16

Supporting Statement Part C-1

Item Justification

National Center for Education Statistics

Institute of Education Sciences

U.S. Department of Education

March

2017

revised April 2019

Contents

C1. Item Description and Justification: SSOCS:2018 and SSOCS:2020 1

C2. Changes to the Questionnaire and Rationale: SSOCS:2018 10

2.3 Item Deletions and Rationale 13

2.4 Content Modifications, Item Additions, and Rationale 13

C3. Changes to the Questionnaire and Rationale: SSOCS:2020 14

3.3 Changes to School/Respondent Information 16

3.4 Item Deletions and Rationale 17

3.5 Global Changes to Formatting and Instructions 17

C4. School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS) 2018 Cognitive Interview Report 19

C1. Item Description and Justification: SSOCS:2018 and SSOCS:2020

At various times in the history of the School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS), the survey items have been examined both for the quality of their content and the data collected in response to them and, when necessary, the questionnaire has been adjusted. To maintain consistent benchmarks over time, to the extent possible, minimal changes have been made to the questionnaire between survey administrations. Some items were removed from the SSOCS:2018 and SSOCS:2020 questionnaires based on a perceived decline in their usefulness and to reduce the burden on respondents, and some items were revised to clarify their meaning.

Information on specific editorial changes, content modifications, item additions, and item deletions is included in Sections C2 and C3 of this document.

Presented below is a complete description of the sections and the corresponding items in the SSOCS:2018 and SSOCS:2020 questionnaires (see appendix B for the full questionnaires).

The SSOCS:2018 questionnaire consists of the following sections:

School practices and programs;

Parent and community involvement at school;

School security staff;

School mental health services;

Staff training and practices;

Limitations on crime prevention;

Frequency of crime and violence at school;

Incidents;

Disciplinary problems and actions; and

School characteristics: 2017–18 school year.

1.1.1 School Practices and Programs

This section collects data on current school policies and programs relating to crime and safety. These data are important in helping schools know where they stand in relation to other schools, and in helping policymakers know what actions are already being taken in schools and what actions schools might be encouraged to take in the future. These data can also benefit researchers interested in evaluating the success of certain school policies. Although SSOCS is not designed as an evaluation, the presence of school policies can be correlated with the rates of crime provided elsewhere in the questionnaire, with appropriate controls for school characteristics.

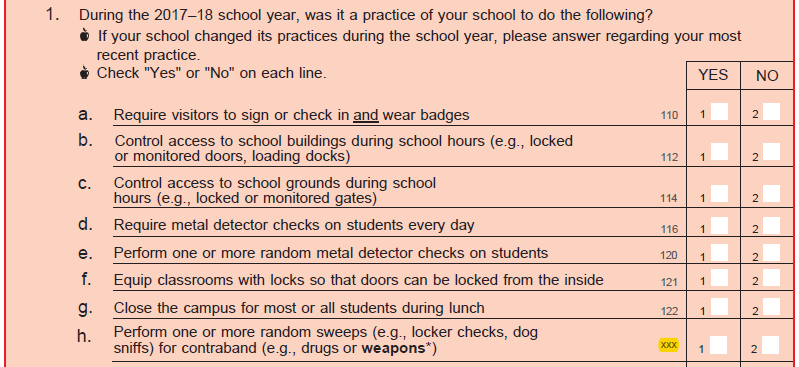

Question 1 asks specifically about the various school policies and practices that are in place, including those that restrict access to school grounds, monitor student behavior to prevent crime, impact the school’s ability to recognize an outsider, and enable communication in the event of a school-wide emergency. These policies and practices are important because they influence the control that administrators have over the school environment as well as the potential for students to bring weapons or drugs onto school grounds. Such actions can directly affect crime because students may be more reluctant to engage in inappropriate activities for fear of being caught. The school climate may also be affected because students may feel more secure knowing that violators of school policies are likely to be caught.

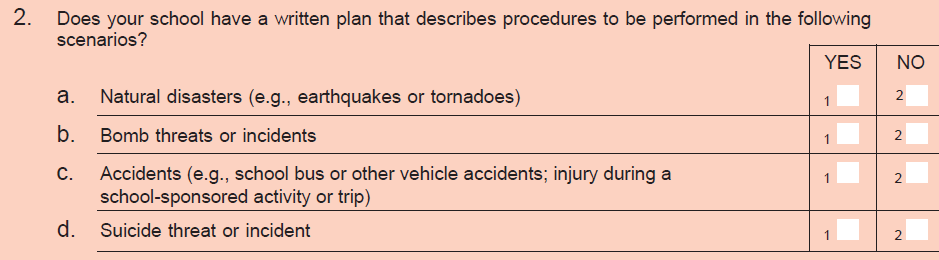

Question 2 asks about the existence of written plans for dealing with various crisis scenarios, and Question 3 asks whether schools drill students on the use of specific emergency procedures. When emergencies occur, there may not be time or an appropriate environment for making critical decisions, and key school leaders may not be immediately available to provide guidance. Thus, having a written plan for crises and drilling students on emergency procedures is important in preparing schools to deal with crises effectively.

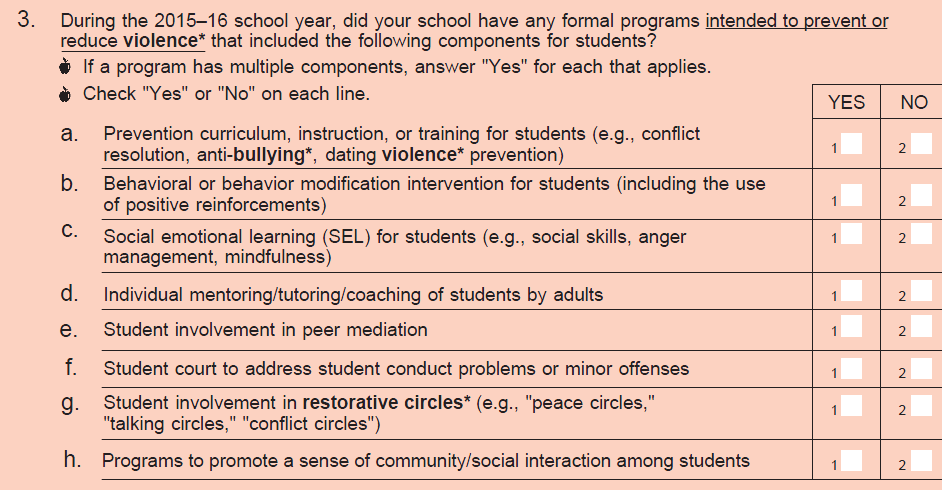

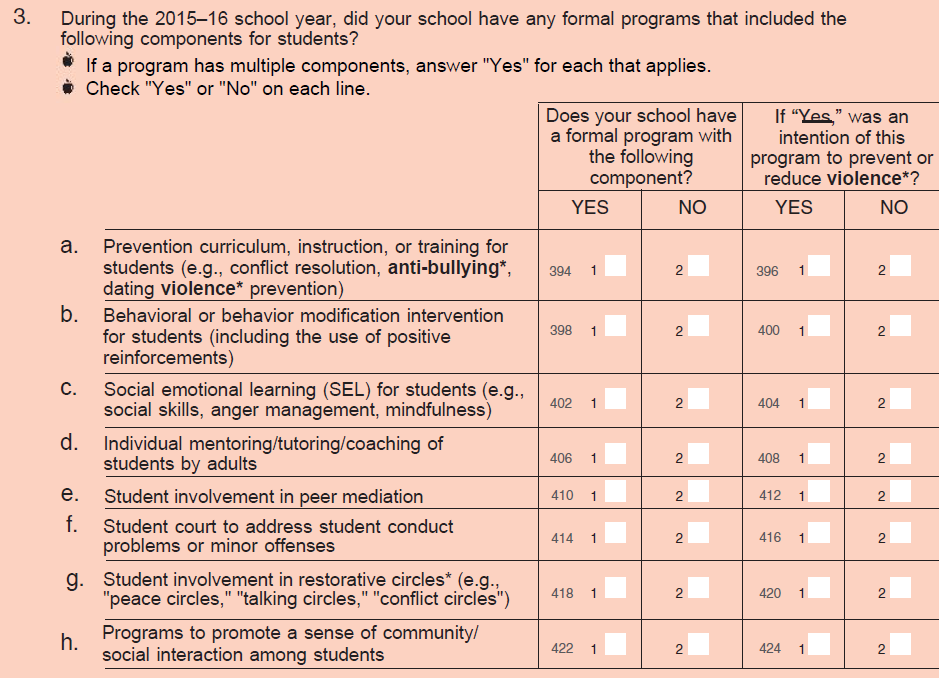

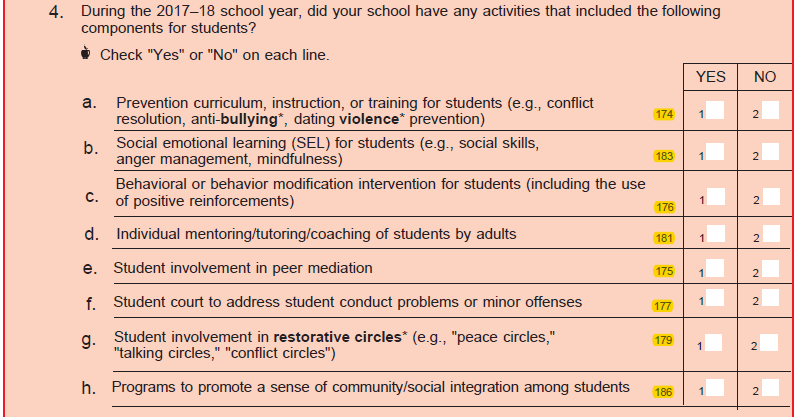

Question 4 asks about various activities schools have in place that may directly or indirectly prevent or reduce violence. The presence of such activities is a sign that schools are being proactive by seeking to prevent violence before it occurs rather than reacting to it.

Questions 5 and 6 ask whether schools have a threat assessment team, and, if so, how often the threat assessment team meets. Threat assessment teams are an emerging practice in schools to identify and interrupt students who may be on a path to violent behavior.

Question 7 asks about the presence of recognized student groups that promote inclusiveness and acceptance in schools. The presence of such groups is important in creating a climate in which students are respectful of peers from all backgrounds and may help to reduce conflict and violence.

1.1.2 Parent and Community Involvement at School

This section asks about the involvement of parents and community groups in schools. Parent and community involvement in schools can affect the school culture and may impact the level of crime in a school.

Questions 8 and 9 ask about policies or practices that schools have implemented to involve parents in school procedures and the percentage of parents participating in specific school events.

Question 10 asks if specific community organizations are involved in promoting a safe school environment to determine the extent to which the school involves outside groups.

1.1.3 School Security Staff

Questions 11 through 18 ask about the use and activities of sworn law enforcement officers (including School Resource Officers) on school grounds and at school events. Question 19 asks about the presence of other security personnel who are not sworn law enforcement officers. In addition to directly affecting school crime, the use of security staff can also affect the school environment. Security staff may help prevent illegal actions, reduce the amount of crime, and contribute to feelings of security or freedom on school grounds. Thus, the times that law enforcement personnel are present, their visibility, their roles and responsibilities, and their carrying of weapons are all important.

1.1.4 School Mental Health Services

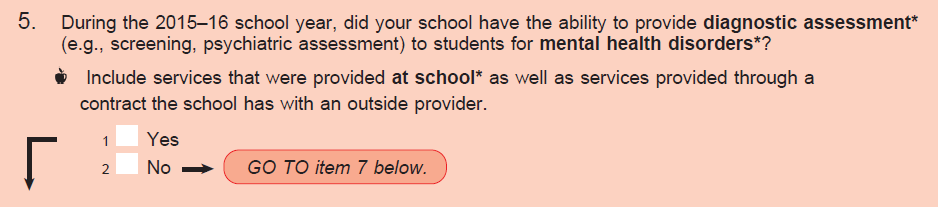

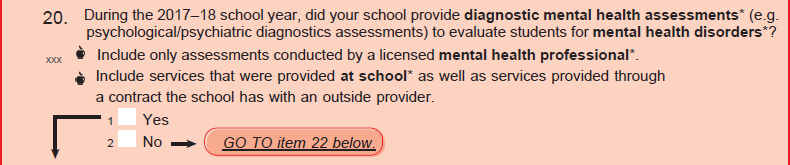

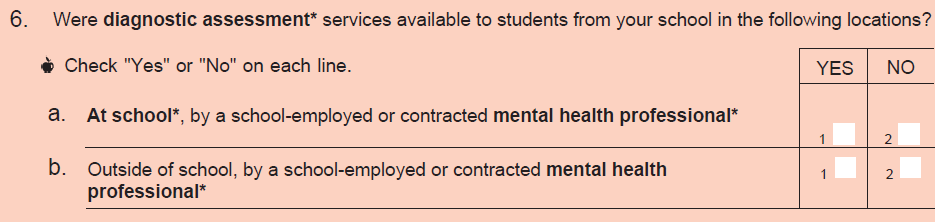

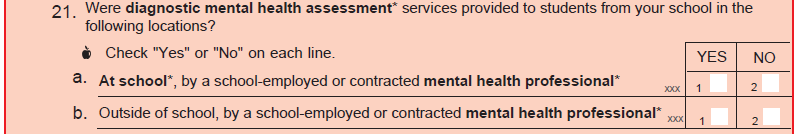

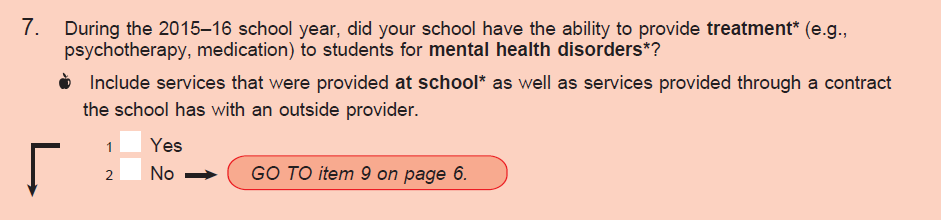

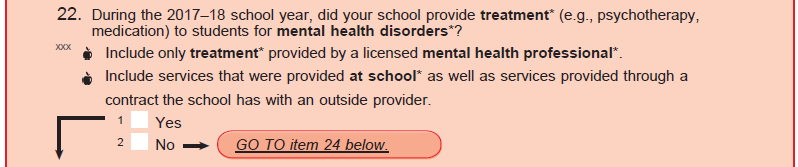

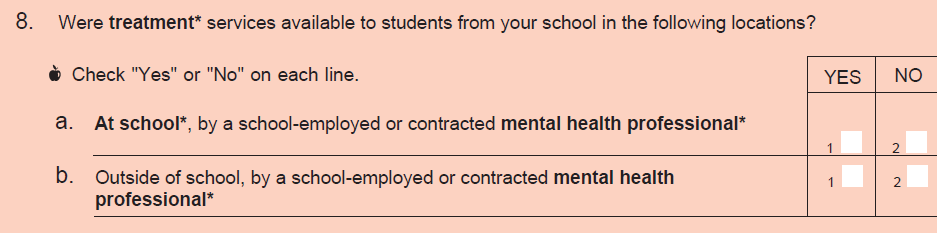

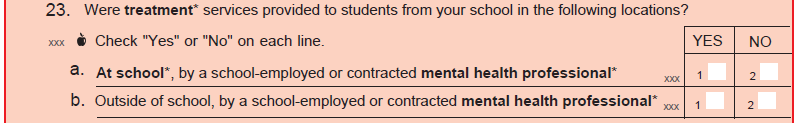

Questions 20 and 21 ask whether diagnostic mental health assessments were provided to students by a licensed mental health professional and whether these diagnostic assessments were provided at school or outside of school (school-employed or contracted mental health professionals may provide diagnostic assessment services in either or both locations). Questions 22 and 23 ask whether treatment for mental health disorders was provided to students by a licensed mental health professional and whether treatment was provided at school or outside of school (school-employed or contracted mental health professionals may provide treatment in either or both locations). Assessing the types of mental health services provided by schools as well as the location of these services demonstrates how well equipped schools are to deal with students who have mental disorders. Schools’ ability to attend to students who have mental health disorders may influence the frequency and severity of delinquency and behavioral problems within the school.

Question 24 asks for principals’ perceptions of the factors that limit their schools’ efforts to provide mental health services to students. The question asks about factors such as inadequate access to licensed mental health professionals, inadequate funding, concerns about parents’ reactions, and the legal responsibilities of the school. Schools that face issues relating to inadequate resources or support may have limited effectiveness in providing mental health services to students. Schools’ financial obligation to pay for mental health services may also make them reluctant to identify students who require these services.

1.1.5 Staff Training and Practices

Question 25 asks whether schools or districts provide training for classroom teachers or aides on topics such as classroom management; school-wide policies and practices related to violence, bullying, and cyberbullying; alcohol and/or drug use; and safety procedures. Other types of training include recognizing potentially violent students; recognizing signs of suicidal tendencies; recognizing signs of substance abuse; intervention and referral strategies for students who display signs of mental health disorders; recognizing physical, social, and verbal bullying; positive behavioral intervention strategies; and crisis prevention and intervention. Schools can now obtain early warning signs to identify potentially violent students, and their use of such profiles may affect both general levels of discipline and the potential for crises. The type of training provided to teachers is important because teachers collectively spend the most time with students and observe them closely. Moreover, there is evidence in recent research that a substantial discrepancy exists in the percentage of schools that have these types of policies and the percentage of teachers that are trained in them. Collecting data on teacher training will inform efforts to combat violence and discipline problems in schools.

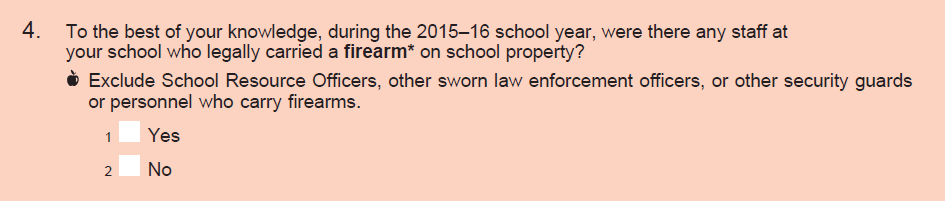

Question 26 asks if there are any school staff who legally carry a firearm on school property. While many school districts and states have policies that prohibit carrying firearms on school property, some state and district policies allow school staff to legally carry (concealed) firearms at school. While not all policies require those who carry a firearm on campus to divulge that information, principals may be aware of some instances in which staff members have brought firearms on school property. The presence of firearms in schools may be an indicator of the school climate.

1.1.6 Limitations on Crime Prevention

This section asks for principals’ perceptions of the factors that limit their schools’ efforts to reduce or prevent crime. Question 27 asks about factors such as lack of adequate training for teachers, lack of support from parents or teachers, inadequate funding, and federal, state, or district policies on disciplining students. Although principals are not trained evaluators, they are the people who are the most knowledgeable about the situations at their schools and whether their own actions have been constrained by the factors listed.

Schools that face issues relating to inadequate resources or support may have limited effectiveness in responding to disciplinary issues and reducing or preventing crime. Identifying principals’ perceptions of the factors that limit their ability to prevent crime in school can inform efforts to minimize obstructions to schools’ crime prevention measures.

1.1.7 Frequency of Crime and Violence at School

Questions 28 and 29 ask about violent deaths, specifically homicides and shootings at school. Violent deaths get substantial media attention but are actually relatively rare. There is evidence that, in general, schools are much safer than students’ neighboring communities. Based on analyses of such previous SSOCS data, these crimes are such rare events that the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) is unable to report estimates per its statistical standards. Nonetheless, it is important to include these items as they are significant incidents of crime that, at the very least, independent researchers can evaluate. Furthermore, the survey is intended to represent a comprehensive picture of the types of violence that can occur in schools, and the omission of violent deaths and shootings would be questioned by respondents who may have experienced such violence.

1.1.8 Incidents

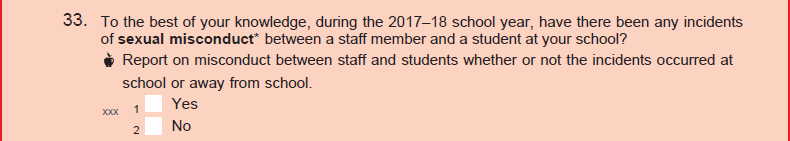

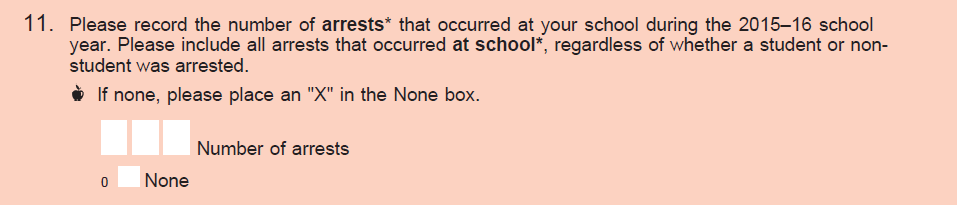

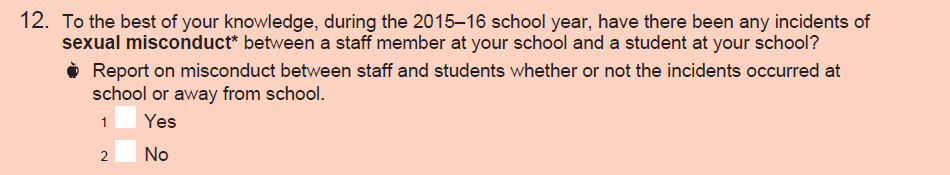

The questions in this section ask about the frequency and types of crime and disruptions at school (other than violent deaths). Question 30 specifically asks principals to provide counts of the number of recorded incidents that occurred at school and the number of incidents that were reported to the police or other law enforcement. Question 30 will assist in identifying which types of crimes in schools are underreported to the police and will provide justification for further investigation. Questions 31 and 32 ask about the number of hate crimes and the biases that may have motivated these hate crimes. Question 33 asks whether there were any incidents of sexual misconduct between school staff members and students. Question 34 asks about the number of arrests that have occurred at school. The data gained from this section can be used directly as an indicator of the degree of safety in U.S. public schools and indirectly to compare schools in terms of the number of problems they face.

1.1.9 Disciplinary Problems and Actions

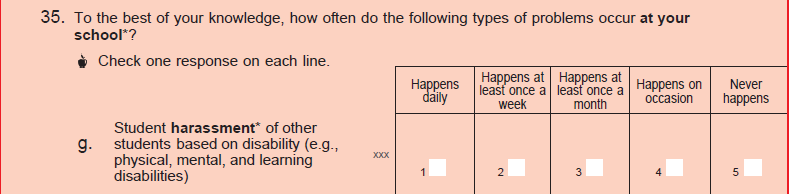

This section asks about the degree to which schools face various disciplinary problems and how schools respond to them. The data gathered in questions 35 and 36 can help to provide an overall measure of the types of problems schools encounter on a regular basis. There is evidence that schools’ ability to control crime is affected by their control of lesser violations, and that, when lesser violations are controlled, students do not progress to more serious disciplinary problems. The data gathered in this section will be helpful in confirming or denying the importance of schools’ control of lesser violations and provide another measure of the disciplinary situation in U.S. schools. The data may also be helpful in multivariate models of school crime by providing a way of grouping schools that are similar in their general disciplinary situation but different in their school policies or programs.

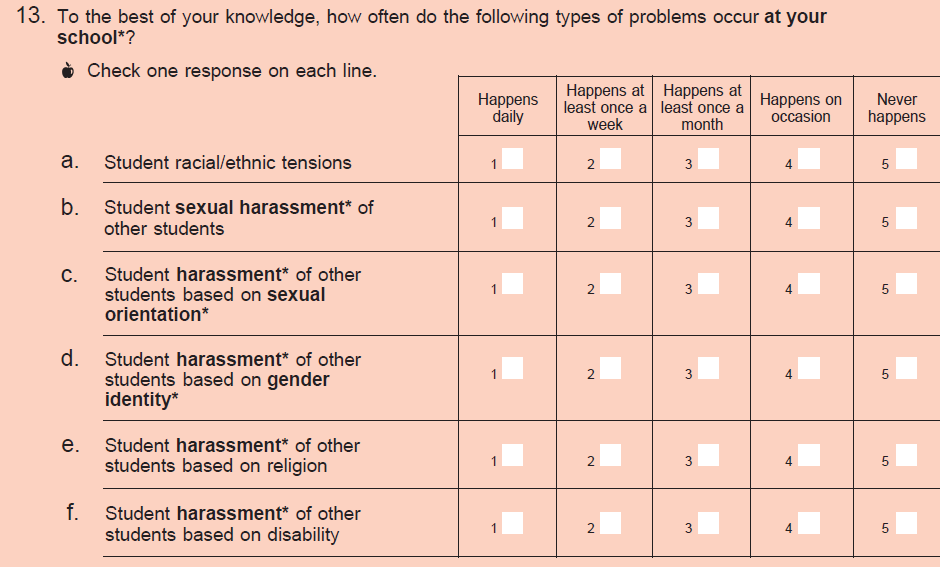

Question 35 asks principals to report, to the best of their knowledge, how often certain disciplinary problems occur at school. Problems of interest include student racial/ethnic tensions; bullying; sexual harassment; harassment based on sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, or disability; widespread disorder in classrooms; student disrespect of teachers; and gang activities. This question provides a general measure of the degree to which there are disciplinary problems at each school.

Question 36 asks about the frequency of three aspects of cyberbullying, providing a general measure of the degree to which cyberbullying is an issue for students and how often staff resources are used to deal with cyberbullying.

Question 37 asks what kinds of disciplinary actions were available to each school and whether each action was actually used during the school year. This item is not intended to be comprehensive; instead, it focuses on some of the most important disciplinary strategies. These data will help policymakers to know what options and what constraints principals face. For example, if an action is allowed in principle but not used in practice, then policymakers would need to act in a different way than if the action is not allowed.

Question 38 asks about the number of various types of offenses committed by students and the resulting disciplinary actions taken by schools. Question 39 asks how many students were removed or transferred from school for disciplinary reasons. These items provide valuable information about how school policies are actually implemented (rather than simply what policies are in place), with a particular emphasis on how many different kinds of actions are taken with regard to a particular offense as well as how many times no actions are taken.

1.1.10 School Characteristics: 2017–18 School Year

This section asks for a variety of information about the characteristics of the schools responding to the survey. The information provided in this section is necessary to be able to understand the degree to which different schools face different situations. For example, one school might have highly effective programs and policies, yet still have high crime rates due to the high crime rates in the area where the school is located. Another school might appear to have effective policies based on its crime rates but actually have higher crime rates than similar schools.

Question 40 asks for the school’s total enrollment.

Question 41 requests information on the school’s student population, including the percentage of students who receive free or reduced-price lunches (a measure of poverty), are English language learners (a measure of the cultural environment), are in special education (a measure of the academic environment), and are male (most crimes are committed by males, so the percentage who are male can affect the overall crime rate).

Question 42 addresses various levels of academic proficiency and interest, which are factors that have been shown to be associated with crime rates.

Question 43 asks for the number of classroom changes made in a typical day. This is important because it affects schools’ ability to control the student environment. When students are in hallways, there are more opportunities for problems. Also, a school with fewer classroom changes is likely to be more personal and to have closer relationships between the students and teachers.

Questions 44 and 45 ask about the crime levels in the neighborhoods where students live and in the area where the school is located. This is an important distinction, since some students may travel a great distance to their school, and their home community may have a significantly different level of crime than their school community.

Question 46 asks for the school type. Schools that target particular groups of students (such as magnet schools) have more control over who is in the student body and may have more motivated students because the students have chosen a particular program. Charter schools have more freedom than regular schools in their school policies, may have more control over who is admitted into the student body, and may have more motivated students because the students chose to attend the school.

Question 47 asks for the school’s average daily attendance. This is a measure of truancy and thus a measure of the level of disciplinary problems at the school. It also is a measure of the academic environment.

Question 48 asks for the number of transfers. When students transfer after the school year has started, schools have less control over whether and how the students are assimilated into the school. These students are likely to have less attachment to the school as well as to the other students, thus increasing the risk of disciplinary problems.

1.2 SSOCS: 2020

The SSOCS:2020 questionnaire and procedures are expected to be the same as in SSOCS:2018. Due to adjustments to the questionnaire between these two administrations, some item numbers have shifted. The item numbers presented below represent the SSOCS:2020 question numbering, with the SSOCS:2018 question numbers displayed in parentheses. Further details on the changes made to the questionnaire between the 2018 and 2020 administrations of SSOCS, including rationales for the changes, can be found in Section C3.

The SSOCS:2020 questionnaire consists of the following sections:

School practices and programs;

Parent and community involvement at school;

School security staff;

School mental health services;

Staff training and practices;

Limitations on crime prevention;

Incidents (the section on Frequency of Crime and Violence at School was removed from the SSOCS:2020 questionnaire; items previously in that section were incorporated into the Incidents section)

Disciplinary problems and actions; and

School characteristics: 2019–20 school year.

1.2.1 School Practices and Programs

This section collects data on current school policies and programs relating to crime and safety. These data are important in helping schools know where they stand in relation to other schools, and in helping policymakers know what actions are already being taken in schools and what actions schools might be encouraged to take in the future. These data can also benefit researchers interested in evaluating the success of certain school policies. Although SSOCS is not designed as an evaluation, the presence of school policies can be correlated with the rates of crime provided elsewhere in the questionnaire, with appropriate controls for school characteristics.

Question 1 (SSOCS:2018 Question 1)

This question asks specifically about the various school policies and practices that are in place, including those that restrict access to school grounds, monitor student behavior to prevent crime, impact the school’s ability to recognize an outsider, and enable communication in the event of a school-wide emergency. These policies and practices are important because they influence the control that administrators have over the school environment as well as the potential for students to bring weapons or drugs onto school grounds. Such actions can directly affect crime because students may be more reluctant to engage in inappropriate activities for fear of being caught. The school climate may also be affected because students may feel more secure knowing that violators of school policies are likely to be caught.

Questions 2 and 3 (SSOCS:2018 Questions 2 and 3)

These questions ask about the existence of written plans for dealing with various crisis scenarios, and whether schools drill students on the use of specific emergency procedures. When emergencies occur, there may not be time or an appropriate environment for making critical decisions, and key school leaders may not be immediately available to provide guidance. Thus, having a written plan for crises and drilling students on emergency procedures is important in preparing schools to deal with crises effectively.

Question 4 (SSOCS:2018 Question 4)

This question asks about various activities schools have in place that may directly or indirectly prevent or reduce violence. The presence of such activities is a sign that schools are being proactive by seeking to prevent violence before it occurs rather than reacting to it.

Questions 5 (SSOCS:2018 Questions 5 and 6)

This question asks whether schools have a threat assessment team. Threat assessment teams are an emerging practice in schools to identify and interrupt students who may be on a path to violent behavior. A follow-up question in the SSOCS:2018 questionnaire asked how often the threat assessment team meets; this question was removed from the SSOCS:2020 questionnaire.

Question 6 (SSOCS:2018 Question 7)

This question asks about the presence of recognized student groups that promote inclusiveness and acceptance in schools. The presence of such groups is important in creating a climate in which students are respectful of peers from all backgrounds and may help to reduce conflict and violence.

1.2.2 Parent and Community Involvement at School

This section asks about the involvement of parents and community groups in schools. Parent and community involvement in schools can affect the school culture and may impact the level of crime in a school.

Question 7 (SSOCS:2018 Questions 8 and 9)

This question asks about policies or practices that schools have implemented to involve parents in school procedures. An additional question in the SSOCS:2018 questionnaire asked about the percentage of parents participating in specific school events; this question was removed from the SSOCS:2020 questionnaire.

Question 8 (SSOCS:2018 Question 10)

This question asks if specific community organizations are involved in promoting a safe school environment to determine the extent to which the school involves outside groups.

1.2.3 School Security Staff

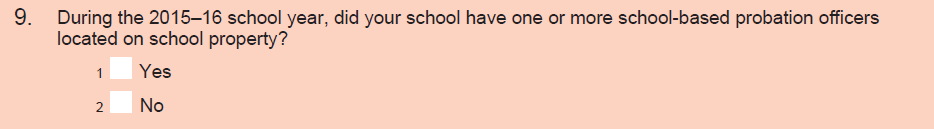

Questions 9 through 15 (SSOCS:2018 Questions 11 through 18)

These questions ask about the use and activities of sworn law enforcement officers (including School Resource Officers) on school grounds and at school events. One question from this section (SSOCS:2018 Question 15) was removed from the SSOCS:2020 questionnaire.

Question 16 (SSOCS:2018 Question 19)

This question asks about the presence of other security personnel who are not sworn law enforcement officers. In addition to directly affecting school crime, the use of security staff can also affect the school environment. Security staff may help prevent illegal actions, reduce the amount of crime, and contribute to feelings of security or freedom on school grounds. Thus, the times that law enforcement personnel are present, their visibility, their roles and responsibilities, and their carrying of weapons are all important.

1.2.4 School Mental Health Services

Questions 17 and 18 (SSOCS:2018 Questions 20 and 21)

These questions ask whether diagnostic mental health assessments were provided to students by a licensed mental health professional and whether these diagnostic assessments were provided at school or outside of school (school-employed or contracted mental health professionals may provide diagnostic assessment services in either or both locations).

Questions 19 and 20 (SSOCS:2018 Questions 22 and 23)

These questions ask whether treatment for mental health disorders was provided to students by a licensed mental health professional and whether treatment was provided at school or outside of school (school-employed or contracted mental health professionals may provide treatment in either or both locations). Assessing the types of mental health services provided by schools as well as the location of these services demonstrates how well equipped schools are to deal with students who have mental disorders. Schools’ ability to attend to students who have mental health disorders may influence the frequency and severity of delinquency and behavioral problems within the school.

Question 21 (SSOCS:2018 Question 24)

This question asks for principals’ perceptions of the factors that limit their schools’ efforts to provide mental health services to students. The question asks about factors such as inadequate access to licensed mental health professionals, inadequate funding, concerns about parents’ reactions, and the legal responsibilities of the school. Schools that face issues relating to inadequate resources or support may have limited effectiveness in providing mental health services to students. Schools’ financial obligation to pay for mental health services may also make them reluctant to identify students who require these services.

1.2.5 Staff Training and Practices

Question 22 (SSOCS:2018 Question 25)

This question asks whether schools or districts provide training for classroom teachers or aides on topics such as classroom management; school-wide policies and practices related to violence, bullying, and cyberbullying; alcohol and/or drug use; and safety procedures. Other types of training include recognizing potentially violent students; recognizing signs of suicidal tendencies; recognizing signs of substance abuse; intervention and referral strategies for students who display signs of mental health disorders; recognizing physical, social, and verbal bullying; positive behavioral intervention strategies; and crisis prevention and intervention. Schools can now obtain early warning signs to identify potentially violent students, and their use of such profiles may affect both general levels of discipline and the potential for crises. The type of training provided to teachers is important because teachers collectively spend the most time with students and observe them closely. Moreover, there is evidence in recent research that a substantial discrepancy exists in the percentage of schools that have these types of policies and the percentage of teachers that are trained in them. Collecting data on teacher training will inform efforts to combat violence and discipline problems in schools.

Question 23 (SSOCS:2018 Question 26)

This question asks if there are any school staff who legally carry a firearm on school property. While many school districts and states have policies that prohibit carrying firearms on school property, some state and district policies allow school staff to legally carry (concealed) firearms at school. While not all policies require those who carry a firearm on campus to divulge that information, principals may be aware of some instances in which staff members have brought firearms on school property. The presence of firearms in schools may be an indicator of the school climate.

1.2.6 Limitations on Crime Prevention

This section asks for principals’ perceptions of the factors that limit their schools’ efforts to reduce or prevent crime.

Question 24 (SSOCS:2018 Question 27)

This question asks about factors such as lack of adequate training for teachers, lack of support from parents or teachers, and inadequate funding.. Although principals are not trained evaluators, they are the people who are the most knowledgeable about the situations at their schools and whether their own actions have been constrained by the factors listed. Four subitems from this section (SSOCS:2018 items 27j–m) were removed from the SSOCS:2020 questionnaire.

Schools that face issues relating to inadequate resources or support may have limited effectiveness in responding to disciplinary issues and reducing or preventing crime. Identifying principals’ perceptions of the factors that limit their ability to prevent crime in school can inform efforts to minimize obstructions to schools’ crime prevention measures.

1.2.7 Incidents

The questions in this section ask about the frequency and types of crime and disruptions at school (other than violent deaths). Note that the section Frequency of Crime and Violence at School has been removed from the SSOCS:2020 questionnaire and its items have been incorporated into the Incidents section.

Question 25 (SSOCS:2018 Question 30)

This question specifically asks principals to provide counts of the number of recorded incidents that occurred at school and the number of incidents that were reported to the police or other law enforcement. This question will assist in identifying which types of crimes in schools are underreported to the police and will provide justification for further investigation.

Questions 26 and 27 (SSOCS:2018 Questions 31 and 32)

These questions ask about the number of hate crimes and the biases that may have motivated these hate crimes.

Question 28 (SSOCS:2018 Question 33)

This question asks whether there were any incidents of sexual misconduct between school staff members and students.

Questions 29 and 30 (SSOCS:2018 Questions 28 and 29)

These questions ask about violent deaths (specifically, homicides and shootings at school). Although violent deaths get substantial media attention, they are actually relatively rare. In fact, there is evidence that, in general, schools are much safer than students’ neighboring communities. Based on analyses of such previous SSOCS data, these crimes are such rare events that the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) is unable to report estimates per its statistical standards. Nonetheless, it is important to include these items as they are significant incidents of crime that, at the very least, independent researchers can evaluate. Furthermore, the survey is intended to represent a comprehensive picture of the types of violence that can occur in schools, and the omission of violent deaths and shootings would be questioned by respondents who may have experienced such violence. In the SSOCS:2018 questionnaire, these questions were contained in the Frequency of Crime and Violence at School section; this section was removed from the SSOCS:2020 questionnaire and its items moved to the Incidents section.

Question 31 (SSOCS:2018 Question 34)

This question asks about the number of arrests that have occurred at school. The data gained from this section can be used directly as an indicator of the degree of safety in U.S. public schools and indirectly to compare schools in terms of the number of problems they face.

1.2.8 Disciplinary Problems and Actions

This section asks about the degree to which schools face various disciplinary problems and how schools respond to them. The data gathered in questions 32 and 33 (SSOCS:2018 questions 35 and 36) can help to provide an overall measure of the types of problems schools encounter on a regular basis. There is evidence that schools’ ability to control crime is affected by their control of lesser violations, and that, when lesser violations are controlled, students do not progress to more serious disciplinary problems. The data gathered in this section will be helpful in confirming or denying the importance of schools’ control of lesser violations and provide another measure of the disciplinary situation in U.S. schools. The data may also be helpful in multivariate models of school crime by providing a way of grouping schools that are similar in their general disciplinary situation but different in their school policies or programs.

Question 32 (SSOCS:2018 Question 35)

This question asks principals to report, to the best of their knowledge, how often certain disciplinary problems occur at school. Problems of interest include student racial/ethnic tensions; bullying; sexual harassment; harassment based on sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, or disability; widespread disorder in classrooms; student disrespect of teachers; and gang activities. This question provides a general measure of the degree to which there are disciplinary problems at each school.

Question 33 (SSOCS:2018 Question 36)

This question asks about the frequency of cyberbullying (including at and away from school), providing a general measure of the degree to which cyberbullying is an issue for students. Two additional subitems were included in the SSOCS:2018 questionnaire asking about how often cyberbullying affected the school environment and how often staff resources were used to deal with cyberbullying; these subitems were removed from the SSOCS:2020 questionnaire.

Question 34 (SSOCS:2018 Question 37)

This question asks what kinds of disciplinary actions were available to each school and whether each action was actually used during the school year. This item is not intended to be comprehensive; instead, it focuses on some of the most important disciplinary strategies. These data will help policymakers to know what options and what constraints principals face. For example, if an action is allowed in principle but not used in practice, then policymakers would need to act in a different way than if the action is not allowed.

Question 35 (SSOCS:2018 Question 38)

This question asks about the number of various types of offenses committed by students and the resulting disciplinary actions taken by schools.

Question 36 (SSOCS:2018 Question 39)

This question asks how many students were removed or transferred from school for disciplinary reasons. These items provide valuable information about how school policies are actually implemented (rather than simply what policies are in place), with a particular emphasis on how many different kinds of actions are taken with regard to a particular offense as well as how many times no actions are taken.

1.2.9 School Characteristics: 2019–20 School Year (SSOCS:2018 2017–18 School Year)

This section asks for a variety of information about the characteristics of the schools responding to the survey. The information provided in this section is necessary to be able to understand the degree to which different schools face different situations. For example, one school might have highly effective programs and policies, yet still have high crime rates due to the high crime rates in the area where the school is located. Another school might appear to have effective policies based on its crime rates but actually have higher crime rates than similar schools.

Question 37 (SSOCS:2018 Question 40)

This question asks for the school’s total enrollment.

Question 38 (SSOCS:2018 Question 41)

This question requests information on the school’s student population, including the percentage of students who receive free or reduced-price lunches (a measure of poverty), are English language learners (a measure of the cultural environment), are in special education (a measure of the academic environment), and are male (most crimes are committed by males, so the percentage who are male can affect the overall crime rate).

Question 39 (SSOCS:2018 Question 42)

This question addresses various levels of academic proficiency and interest, which are factors that have been shown to be associated with crime rates.

Question 40 (SSOCS:2018 Question 43)

This question asks for the number of classroom changes made in a typical day. This is important because it affects schools’ ability to control the student environment. When students are in hallways, there are more opportunities for problems. Also, a school with fewer classroom changes is likely to be more personal and to have closer relationships between the students and teachers.

Questions 41 and 42 (SSOCS:2018 Questions 44 and 45)

These questions ask about the crime levels in the neighborhoods where students live and in the area where the school is located. This is an important distinction, since some students may travel a great distance to their school, and their home community may have a significantly different level of crime than their school community.

Question 43 (SSOCS:2018 Question 46)

This question asks for the school type. Schools that target particular groups of students (such as magnet schools) have more control over who is in the student body and may have more motivated students because the students have chosen a particular program. Charter schools have more freedom than regular schools in their school policies, may have more control over who is admitted into the student body, and may have more motivated students because the students chose to attend the school.

Question 44 (SSOCS:2018 Question 47)

This question asks for the school’s average daily attendance. This is a measure of truancy and thus a measure of the level of disciplinary problems at the school. It also is a measure of the academic environment.

Question 45 (SSOCS:2018 Question 48)

This question asks for the number of transfers. When students transfer after the school year has started, schools have less control over whether and how the students are assimilated into the school. These students are likely to have less attachment to the school as well as to the other students, thus increasing the risk of disciplinary problems.

C2. Changes to the Questionnaire and Rationale: SSOCS:2018

The following section details the editorial changes, deletions, and additions made to the SSOCS:2016 questionnaire. Based on the results of the SSOCS:2016 data collection and cognitive interview testing, some items for SSOCS:2018 were revised to clarify their meaning. Additionally, several items were removed from the survey based on a perceived decline in their usefulness and to make room for new items that reflect emerging issues in school crime and safety.

The result is the proposed instrument for the SSOCS:2018 survey administration, which is located in appendix B. For additional information on the rationales for item revisions, please see the findings and resulting recommendations from cognitive testing, which are located in Part C4.

One definition (sexual misconduct) has been added to clarify a term used in a new survey item on the 2018 questionnaire. Three definitions (arrest, harassment, and school resource officer) have been added to clarify terms already used in previous questionnaires. Eight definitions (bullying, cyberbullying, diagnostic mental health assessment, mental health professional, rape, sexual assault, sexual harassment, and treatment) were revised to increase clarity for survey respondents.

Arrest – A formal definition has been added to increase consistency in the interpretation of an “arrest.” The definition aligns with the definition used by the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Bullying – The three key components for bullying (an observed or perceived power imbalance, repetition, and the exclusion of siblings or current dating partners) have been re-ordered in the definition to increase readability.

Cyberbullying – The definition for cyberbullying has been revised to explicitly identify cyberbullying as a form of bullying.

Diagnostic mental health assessment – The definition for diagnostic mental health assessment (previously called “diagnostic assessment”) was modified to remove references to general medical professionals and medical diagnoses other than mental health. The revisions will help respondents to distinguish diagnostic assessments for mental health disorders from assessments that may be administered to identify other medical or educational issues.

Harassment – A formal definition has been added to clarify “harassment.” The definition aligns closely with the definition used in the Civil Rights Data Collection conducted by the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights.

Mental health professional – The definition for mental health professional has been revised to specify that mental health professionals are licensed.

Rape – The definition of rape has been modified to specify that all students, regardless of sex or gender identity, can be victims of rape.

School resource officer – As this term is used in the instructions for many survey items, the definition for school resource officer is now included in the list of formal definitions. Previously, the definition for this term was included directly in subitem 18a.

Sexual assault – The definition for sexual assault has been modified to specify that all students, regardless of sex or gender identity, can be victims of sexual assault.

Sexual harassment – The definition for sexual harassment has been modified to specify that all students, regardless of sex or gender identity, can be victims of sexual harassment and to include additional examples of forms of harassment. Additionally, as the corresponding survey item asks only about sexual harassment of students by students, examples of other perpetrators (e.g., school employees, non-school employees) were removed from the definition.

Sexual misconduct – This definition was added to the questionnaire in accordance with a new item on incidents of sexual misconduct. The definition aligns with language used in legislation in several states, such as the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s “Educator Discipline Act.”

Treatment – In consultation with mental health experts, the wording of this definition was modified to clarify that “treatment” refers to clinical interventions to address mental health disorders.

Throughout the questionnaire, the school year has been updated to reflect the most recent 2017–18 school year, and item skip patterns have been updated to reflect the new numbering in the questionnaire.

Item 1, subitem b. “Loading docks” was added as an example to this item in a parenthetical notation.

Item 1, subitem h. This item has been modified to combine the two items on random sweeps, subitems 1h and 1i, on the 2016 questionnaire. The resulting item does not distinguish between random sweeps conducted using dog sniffs and those that do not use dog sniffs, because it is more important to identify how many schools are conducting sweeps for contraband as opposed to the method used for such sweeps.

Item 1, subitem i. This item has been modified to combine the two items on drug testing, subitems 1j and 1k, on the 2016 questionnaire. The resulting item does not distinguish between drug testing for student athletes and drug testing for students in extracurricular activities other than athletics, because it is more important to identify how many schools are conducting random drug testing as opposed to the specific population that is being drug tested.

Item 1, subitem u. This item has been modified to specify prohibition of “non-academic” use of cell phones or smartphones since many schools now permit students to use cell phones during school hours for academic purposes. “Text messaging devices” has also been changed to “smartphones.”

Item 2, subitem g. This item has been modified to “pandemic disease” to broaden the scope of the item since schools’ emergency plans may include infectious diseases other than or in addition to the flu.

Item 4, subitem b. The word “training” was removed from this item, and the item was moved to follow subitem 4a in an effort to put similar items closer together.

Item 4, subitem d. The word “attention” has been removed from this item since individual mentoring, tutoring, and coaching all imply individual attention.

Item 13, subitem a. The wording of this item was revised to increase consistency between subitems 13a and 17b.

Item 14, subitem c. The wording of this item was revised to increase consistency between subitems 14c and 17a.

Item 17, subitem b. The wording of this item was revised to increase consistency between subitems 13a and 17b.

Item 18, subitem a. The definition for School Resource Officer was removed from this item as the definition is now included in the list of formal definitions.

Item 19. The wording of this item stem was re-ordered to read “sworn law enforcement officers (including School Resource Officers)” to increase consistency with the wording used in other items in the School Security Staff section.

Item 24, subitem c. “Confidentiality” was added as an example to this item in a parenthetical notation.

Item 24, subitem f. Per changes to the term and definition as noted above, “diagnostic assessment” was changed to “diagnostic mental health assessment” in this item. Additionally, “diagnostic mental health assessment” and “treatment” were bolded and marked with an asterisk as an indication that these terms have a formal definition.

Item 32, subitem c. The word “gender” was changed to “sex” to align the terminology in the questionnaire with the terminology used in other NCES data collections.

Item 32, subitem e. A parenthetical was added to clarify the meaning of “disability.” The examples given in the parenthetical (physical, mental, and learning disabilities) align with those used in subitem 35g.

Item 34. Previously, this item asked respondents to record the number of arrests that occurred at school. Since respondents are sometimes unable to record the exact number of arrests, the format of this item has been changed to use the following response categories: 0, 1–5, 6–10, and 11 or more. These data will be used to benchmark against estimates collected in other federal data collections. Due to the addition and removal of items from the “Incidents” section of the survey, this item was moved to the end of the section to establish a better flow in the survey items.

Item 37, subitem b. “At-home instruction” was changed to “home instruction” to align the terminology in the questionnaire with the terminology used by schools.

Item 41, subitem b. “Limited English Proficient” was changed to “English language learner (ELL)” to align the terminology in the questionnaire with the terminology used in other NCES data collections.

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 1, subitem h. This item was deleted. The two items on random sweeps (1h and 1i in the 2016 questionnaire) were combined because it is more important to identify how many schools are conducting sweeps for contraband than whether or not schools are using dog sniffs during these sweeps.

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 1, subitem k. This item was deleted. The two items on required drug testing (1j and 1k in the 2016 questionnaire) were combined because it is more important to identify how many schools are conducting random drug testing as opposed to the specific population that is being tested.

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 1, subitem v. This item was deleted. This variable was determined to be outdated and to have limited analytic use.

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 1, subitem x. This item was deleted. This variable was determined to be outdated and to have limited analytic use.

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 4, subitem c. This item was deleted. This variable was shown to have little variance and to have limited analytic use.

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 4, subitem d. This item was deleted. This variable was determined to have limited analytic use and was dropped to increase the focus on other, more-specific programs included in item 4.

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 4, subitem f. This item was deleted. This variable was determined to have limited analytic use and was dropped to increase the focus on other, more-specific programs included in item 4.

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 8, subitem c. This item was deleted. This variable was determined to have limited analytic use.

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 9, subitem c. This item was deleted. Similar information is collected in other NCES surveys, such as the National Household Education Surveys.

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 9, subitem d. This item was deleted. Similar information is collected in other NCES surveys, such as the National Household Education Surveys.

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 14, subitem d. This item was deleted. This variable was shown to have little variance and limited analytic use.

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 20. This item was deleted. To address limitations in the format of the item in the 2016 questionnaire and to improve comprehension, information on the types of mental health services available and the location of these services will now be collected in four separate items (items 20, 21, 22, and 23 in the 2017–18 questionnaire).

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 21, subitem d. This item was deleted. To collect information on limitations related to the broader scope of parental concerns regarding schools’ efforts to provide mental health services to students, it was replaced with a new item on “concerns about reactions from parents.”

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 30. This item was deleted. This item was determined to have limited analytic use, and its deletion is intended to help reduce overall questionnaire burden on the respondent.

2015–16 Questionnaire, Item 31. This item was deleted. This item was determined to have limited analytic use, and its deletion is intended to help reduce overall questionnaire burden on the respondent.

Item 4. The stem of this item was revised. Specifically, “programs” was changed to be “activities” to encompass the wide range of programs, trainings, and interventions that schools may implement in an attempt to prevent or reduce violence. Additionally, the specification of “formal” was also removed from the item since both “formal” and “informal” activities are important in schools’ attempts to prevent or reduce violence. The specification that activities must be “intended to prevent or reduce violence” was also removed since it is assumed all activities in this item have an explicit or implicit intent to prevent or reduce violence. The instruction to answer “Yes” for all that applies was also removed.

Item 20. This item has been added to assess the percentage of schools that provide diagnostic mental health assessments to evaluate students for mental health disorders. Adequate assessment of mental health disorders in students may help to prevent future violent acts, and research supports that school mental health programs can have an impact on reducing behavioral problems.

Item 21. As a follow-up to item 20, this item has been added to assess whether schools are providing diagnostic mental health services at school or outside of school (school-employed or contracted mental health professionals may be providing services in either or both locations).

Item 22. This item has been added to assess the percentage of schools that provide treatment to students for mental health disorders. Adequate treatment of mental health disorders in students may help to prevent future violent acts, and research supports that school mental health programs can have an impact on reducing behavioral problems.

Item 23. As a follow-up to item 22, this item has been added to assess whether schools are providing treatment for mental health disorders at school or outside of school (school-employed or contracted mental health professionals may be providing services in either or both locations).

Item 24, subitem d. This subitem was added to assess whether principals perceive that their schools’ efforts to provide mental health services to students are limited by concerns about how parents may react.

Item 25, subitem h. This item will gather information on whether teachers/aides have been trained in what steps to take once they have recognized the signs of suicidal tendencies or self-harm. Training in recognizing signs of self-harm is critical for interrupting students who may be in situations of self-harm.

Item 26. This item will gather information on the number of schools that had a staff member who legally carried a firearm on school property. While many schools, districts, and states have laws or policies that prevent the carrying of firearms in public schools, a growing number of state and district policies allow school staff to legally carry (concealed) firearms at school, an indication that this item is particularly policy relevant.

Item 33. This item will identify the percentage of schools that had an incident of sexual misconduct between a staff member and a student during the 2017–18 school year. Adding this item is in direct response to a GAO recommendation for the Department of Education to collect data and have the ability to respond to the prevalence of sexual misconduct by school personnel.

Item 35, subitem f. This item will gather information on the frequency of student harassment of other students based on religion. Harassment based on other biases is already included on the survey, and this item will separately identify harassment based on religion.

Item 35, subitem g. This item will gather information on the frequency of student harassment of other students based on disability. Harassment based on other biases is already included in the survey, and this item will separately identify harassment based on student disabilities (including physical, mental, learning, and other disabilities).

C3. Changes to the Questionnaire and Rationale: SSOCS:2020

The following section details the editorial changes, item deletions, and global formatting changes made between the SSOCS:2018 and SSOCS:2020 questionnaires. Based on the results of the SSOCS:2018 data collection, feedback from content area experts, and a seminar on visual design in self-administered surveys, some items for SSOCS:2020 were revised for consistency, clarity, and brevity. The section Frequency of Crime and Violence at School was removed, and the corresponding questions were incorporated into the Incidents section. Additionally, several items were removed from the survey in an effort to reduce overall questionnaire burden on the respondent. No new items were added.

The result is the proposed instrument for the SSOCS:2020 survey administration, which is provided in appendix B.

Three terms and definitions (active shooter, alternative school, and children with disabilities) have been adjusted to align with federal definitions for those terms. Eight definitions (evacuation, gender identity, hate crime, lockdown, rape, School Resource Officer (SRO), shelter-in-place, and threat assessment) have been minimally revised to increase brevity and clarity for survey respondents.

Active shooter – The definition was revised to align with the current definition used by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Alternative school – The definition for alternative school (previously “specialized school”) was revised to align with other NCES and Department of Education surveys and publications.

Children with disabilities – The definition for children with disabilities (previously “special education students”) was updated to align with the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) definition.

Evacuation – The definition was simplified to avoid implied endorsement of a specific procedure for evacuation.

Gender identity – Detailed examples of gender expression were removed from the definition for brevity.

Hate crime – The definition was modified to include national origin or ethnicity as a hate crime bias.

Lockdown – The term was simplified, and examples were removed to avoid implied endorsement of a specific procedure for lockdown.

Rape – The bracketed item-specific instruction was removed from the definition. This information is specific to item 25 and the instructions appear within that item.

School Resource Officer (SRO) – The word “career” was removed from the definition to broaden the definition to all SROs.

Shelter-in-place – The definition was modified to clarify the purpose of the practice and examples of procedures were simplified.

Threat assessment – The word “team” was removed from the term and the definition was modified to focus on a formalized threat assessment process rather than a team.

Throughout the questionnaire, the school year has been updated to reflect the most recent 2019–20 school year, and item skip patterns have been updated to reflect the new numbering in the questionnaire.

Arrest – The first letter in the definition was lowercased for consistency with other definitions.

Gender identity – The word “means” was removed from the beginning of the definition for consistency with other definitions.

Hate crime – The first letter in the definition was lowercased for consistency with other definitions.

Sexual misconduct - The first letter in the definition was lowercased for consistency with the rest of the definitions.

Sexual orientation – The word “means” was removed from the beginning of the definition for consistency with other definitions.

Item 1, subitem a. The underlining and bolding of the word “and” were removed to align with consistent formatting practices across the questionnaire.

Item 1, subitem u. The underlining of the word “use” was removed to align with consistent formatting practices across the questionnaire.

Item 2, subitem f. The term “Suicide threats or incidents” was pluralized to make the item parallel with the wording used in items 2d and 2e.

Item 4, subitem d. The forward slashes in “mentoring/tutoring/coaching” were changed to commas.

Item 5. Per the changes to the term and definition as noted above, the term “threat assessment team” was changed to “threat assessment.”

Item 6, subitem c. This subitem was expanded to include student groups supporting the acceptance of religious diversity.

Item 8. The phrase “disciplined and drug-free schools” was replaced with “a safe school” to broaden the question and better reflect current Department of Education language.

Item 13. The phrase “Memorandum of Use” was changed to “Memorandum of Understanding” to better reflect current terminology.

Item 14. The term “at school” was set in bold and marked with an asterisk to indicate that it has a formal definition.

Item 14, subitem b. The subitem was reworded to distinguish examples of physical restraints from chemical aerosol sprays.

Item 15. The term “Part-time” was capitalized in the instructions to increase consistency with the response options of the item.

Item 16. The term “Part-time” was capitalized in the instructions to increase consistency with the response options of the item. The term “security guards” was changed to “security officers” to better reflect current terminology.

Item 23. The phrase “to the best of your knowledge” was removed from the item for brevity. The instruction to exclude sworn law enforcement was moved into the item stem to increase clarity.

Item 25. The underlining of the word “incidents” was removed to align with consistent formatting practices across the questionnaire. The column 2 header was changed to “Number reported to sworn law enforcement” for clarity.

Item 27, subitem a. The phrase “color” was removed from the item to reduce ambiguity in terminology.

Item 28. The underlining of “whether or not the incidents occurred at school or away from school” was removed to align with consistent formatting practices across the questionnaire.

Item 31. The placement of language specifying the inclusion of both students and non-students was adjusted for increased clarity.

Item 34. The word “Yes” was capitalized for consistency with the rest of the item.

Item 34, subitem c. Per the changes to the term and definition as noted above, the term “a specialized school” was changed to “an alternative school.”

Item 35. Per the changes to the term and definition as noted above, the column 3 header term “specialized schools” was changed to “alternative schools.”

Item 36, subitem b. Per the changes to the term and definition as noted above, the term “specialized schools” was changed to “alternative schools.”

Item 38, subitem c. Per the changes to the term and definition as noted above, the term “Special education students” was changed to “Children with disabilities (CWD).”

Item 44. The question was rephrased to better align with the language above the response box and clarify that the response should be a percentage of the school’s total enrollment.

In prior SSOCS collections, respondents have been asked to provide their name and title/position. For SSOCS 2020, respondents are provided more title/position response options and similar title/position information is being requested for any other school personnel who helped to complete the questionnaire. This modification reflects feedback from the TRP and aims to gain a better understand of all staff involved in completing the survey.

2017–18 Questionnaire Item 6. This item was deleted. Following feedback from an expert panel, it was determined that how often the threat assessment team meets is not a critical piece of information. The broad response options had limited analytic use.

2017–18 Questionnaire Item 9. This item was deleted to reduce respondent burden since the item overlaps with the National Teacher and Principal Survey (NTPS).

2017–18 Questionnaire Item 12, subitem a. This subitem was deleted. Similar information is collected in SSOCS:2020 item 9 (SSOCS:2018 item 11); its deletion is intended to help reduce overall questionnaire burden on the respondent.

2017–18 Questionnaire Item 15. This item was deleted. Similar information is collected in SSOCS:2020 items 9 and 10 (SSOCS:2018 items 11 and 12); its deletion is intended to help reduce overall questionnaire burden on the respondent.

2017–18 Questionnaire Item 27, subitem j. This subitem was deleted. Following feedback from an expert panel, it was determined that this variable was outdated and had limited analytic use.

2017–18 Questionnaire Item 27, subitem k. This subitem was deleted. Following feedback from an expert panel, it was determined that this variable was outdated and had limited analytic use.

2017–18 Questionnaire Item 27, subitem l. This subitem was deleted. Following feedback from an expert panel, it was determined that this variable was outdated and had limited analytic use.

2017–18 Questionnaire Item 27, subitem m. This subitem was deleted. Following feedback from an expert panel, it was determined that this variable was outdated and had limited analytic use.

2017–18 Questionnaire Item 36, subitem b. This subitem was deleted. Following feedback from an expert panel, it was determined that this variable had limited analytic use.

2017–18 Questionnaire Item 36, subitem c. This subitem was deleted. Following feedback from an expert panel, it was determined that this variable had limited analytic use.

In addition to the item-specific changes described above, some global changes were made to enhance the consistency and formatting of the questionnaire in an effort to improve its visual design. A streamlined and consistent questionnaire will be easier for the respondent to follow, reduce response time and burden, and help promote an accurate understanding of survey items and response options. These revisions were based on feedback from a TRP consisting of content area experts and on the recommendations of a national expert in visual design elements for self-administered surveys.

The survey cover page has been revised to:

Include the Department of Education and U.S. Census Bureau logos in order to enhance the perception of the survey’s legitimacy.

Remove white space where the school information will be printed. White space typically indicates an area for the respondent to fill in, but in this case the information will be pre-filled by Census.

Remove the list of endorsements. The endorsements will be provided in a separate handout in order to reduce clutter on the cover page and allow for the incorporation of the logos of some endorsing agencies that respondents may be most familiar with.

Horizontal and vertical grid lines have been removed.

Alternative row shading has been incorporated.

Certain response field shapes have been changed to reflect best practices in questionnaire design. The following guidelines for response fields have been implemented for consistency across the SSOCS:2020 questionnaire. These changes also bring the paper questionnaire design in better alignment with the design of the SSOCS web instrument:

For items where respondents select only one response (out of two or more response options), response fields will appear as circles.

For items where respondents select all applicable responses (out of two or more response options), response fields will appear as squares.

For items where respondents are asked to provide numerical values (e.g., incident counts or dates) or text (e.g., names or e-mail addresses), response fields will appear as rectangles.

Instructions found at the bottom of pages referring the respondent to item definitions will now read “*A removable Definitions sheet is printed on pages 3–4.” Similar to NTPS procedures, the two definition pages will be included as a perforated sheet that can be removed from the questionnaire to facilitate easier reference when taking the survey.

All apple-style bullet points have been changed to circular bullet points.

The source code font has been lightened, and codes have been moved away from response boxes to avoid distracting the respondent.

Certain instructions in the survey were also removed to reduce redundancy and item length. The following instructions are included the first time a style of item response options is introduced, but not in subsequent questions that use the same response option style:

“Check “Yes” or “No” on each line” (appears first in Question 1).

“Check one response on each line” (appears first in Question 21).

“If none, please place an “X” in the None box” (appears first in Question 15).

C4. School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS) 2018 Cognitive Interview Report

Contents

Sample and Recruitment Plan 22

Cognitive Testing Findings and Recommendations 26

Appendices

List of Charts

List of Tables

Table 1. Distribution of cognitive interview participants, by school and interview mode and wave 23

Table 2. Distribution of cognitive interview participants, by school and school characteristics 20

Executive Summary

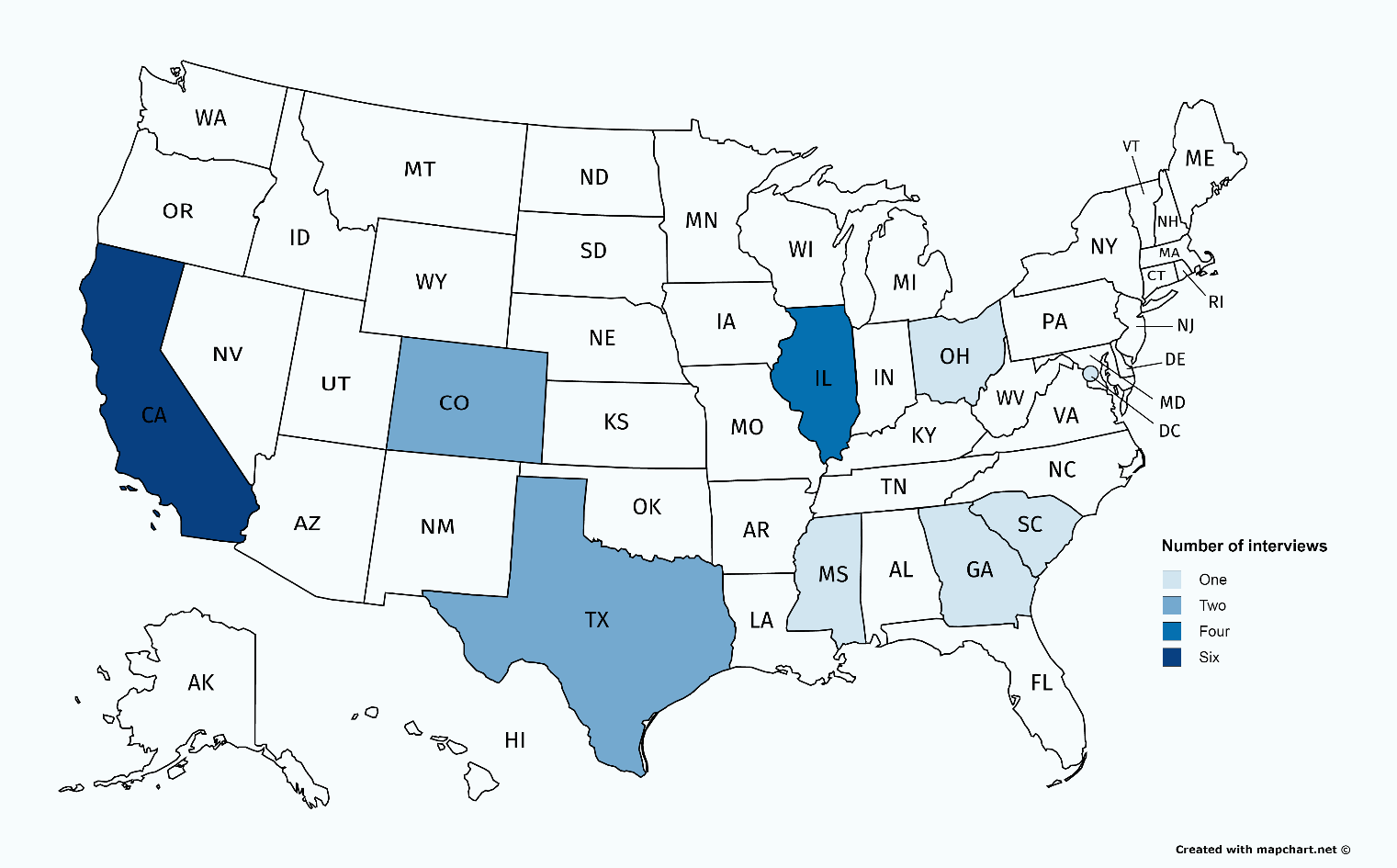

This report summarizes the findings from and decisions following cognitive interviews conducted by American Institutes for Research (AIR) to test and revise items on the School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS) 2018 questionnaire. Nineteen remote and in-person cognitive interviews were conducted across the United States during November and December of 2016.

In the cognitive interviews, AIR interviewers followed a structured protocol in an hour-long one-on-one interview session, where participants were encouraged to “think-aloud” in their answers with probes from the interviewer as needed. The objective of the cognitive interview testing was to identify problems of ambiguity or misunderstanding in item wording as well as response options. The testing allowed revisions and refinement of the wording for the next administration of SSOCS in spring 2018. The intended result of cognitive interviews is a questionnaire that is easier to understand, interpreted consistently across respondents, and aligned with the concepts being measured.

Key Findings and Recommendations

Across cognitive interviews, it was identified that respondents rarely referred back to the instructions or definition page even if they were stuck or found a concept confusing. Small edits to draw the respondent’s attention to definitions will be implemented for the SSOCS:2018 paper questionnaire and, upon approval, SSOCS:2018 will include an experimental web administration; NCES, AIR, and Census intend to incorporate the definitions and skip patterns directly into items for the web instrument.

Item 3, which asked participants to identify components of programs with the intent to prevent or reduce violence, proved to be the tested item which resulted in the most respondent error and confusion. Specifically, most respondents had issues with defining “formal” programs and determining the “intent” of programs. Though revisions made to this item and tested across the latter portion of participants appeared to help respondents some in understanding the scope of the item, continued respondent comprehension issues led NCES and AIR to further revise the item to remove both the specification of “formal” programs and the intent to prevent or reduce violence. It is the nature of all the listed components to either implicitly or explicitly have an influence in reducing/preventing violence.

Respondent feedback on two new items – item 4 on staff carrying firearms at school and item 12 on sexual misconduct between staff and students – yielded no significant comprehension issues. NCES will include these items on SSOCS:2018 to gather information that no other federal survey currently requests. The testing of one new item – item 9 on school-based probation officers – indicated that respondents were confused about the scope of school-based probation officers. Due to these comprehension issues and the fact that the survey included only a general definition of probation officer and not one specific to school-based probation officers, NCES and AIR felt this item should undergo further refinements and testing before being included on the questionnaire; the item will not appear on SSOCS:2018.

Respondents generally experienced few issues with other items tested during cognitive interviews. NCES and AIR made minor revisions to these items to add additional context or clarification.

Participants who reviewed and answered questions about the survey materials and delivery cited that time burden and length of the questionnaire were response deterrents. Respondents noted that the relevant topic and a small gift would be incentivizing to completing the questionnaire. Based on the feedback on the survey materials, NCES and AIR will make efforts to shorten the length of future questionnaires, streamline and target the communication materials, develop a pilot web instrument and electronic materials, and test the inclusion of a monetary incentive to increase response rates.

Introduction

The School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS), a nationally representative survey of elementary and secondary public schools, is one of the nation’s primary sources of school-level data on crime and safety. Managed by the U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), SSOCS has been administered six times, covering the 1999–2000, 2003–04, 2005–06, 2007–08, 2009–10, and 2015–16 school years, and will next be administered in the spring of the 2017–18 school year.

SSOCS is the only recurring federal survey collecting detailed information on the incidence, frequency, seriousness, and nature of violence affecting students and school personnel, as well as other indices of school safety from the schools’ perspective. As such, SSOCS fills an important gap in data collected by NCES and other federal agencies. Topics covered by SSOCS include school practices and programs, parent and community involvement, school security staff, school mental health services, staff training, limitations on crime prevention, the type and frequency of crime and violence, and the types of disciplinary problems and actions used in schools. Principals or other school personnel designated by the principal as the person who is “the most knowledgeable about school crime and policies to provide a safe environment” are asked to complete SSOCS questionnaires.

Background

At multiple points in its history, the quality of SSOCS survey items has been examined. To the greatest extent possible, minimal changes have been made to existing survey items to maintain consistent benchmarks over time. However, items have periodically been modified to ensure relevancy, and new items have been added to address emerging issues of interest. The 2016 questionnaire, which included approximately 40 new and modified items or sub-items on school practices and programs, school security staff, school mental health services, staff training, and incidents of crime, received OMB clearance in August 2015 (OMB# 1850-0761 v.8). The 2015–16 data collection was fielded in spring 2016.

SSOCS will be conducted again in spring 2018. NCES and its contractor, the American Institutes for Research (AIR), held a series of meetings in spring and summer 2016 to discuss the proposed content of the SSOCS:2018 questionnaire. NCES and AIR also requested feedback on proposed and modified survey items from top experts in school crime and safety who previously served as Technical Review Panel (TRP) members during development of prior SSOCS questionnaires. As a result of these discussions, 8 items or sub-items were recommended for addition, 15 items or sub-items were recommended to be modified, and 10 items or sub-items were removed from the questionnaire. Additionally, recommendations were made to add or modify several definitions in accordance with changes made to survey items.

As a final step in the item development process, a portion of the new and modified survey items were tested on target participants through cognitive interviews in fall 2018 (the questionnaire that contains all of the items that underwent cognitive testing can be found in appendix A-1 of this report). In addition to the selection of survey items, questions about the communication materials and physical survey package contents were also tested to assess possible factors which may or may not contribute to the propensity of completing the survey (the communication materials that were tested can be found in appendix A-2). This document describes the types of cognitive testing conducted, the sample and recruitment plans, the data collection process, and the data analysis process. It also provides detailed findings from the cognitive interviews as well as summarizes the discussion of results and final decisions on additional modifications to survey items and materials included in the 2018 questionnaire.

Study Purpose

The objective of cognitive interviews is to uncover participants’ specific comprehension issues when responding to survey items. Cognitive interviews also measure participants’ overall understanding of the content surveyed. In a cognitive interview, an interviewer uses a structured protocol in a one-on-one interview, drawing on methods from cognitive science. Interviews are intended to identify problems of ambiguity or misunderstanding in question wording, with the goal of ensuring that final survey items are easily understood, interpreted consistently across respondents, and aligned with the concepts being measured. Cognitive interviews should result in a questionnaire that is easier to understand and therefore less burdensome for respondents, as they also yield more accurate information.

Methodology

Sample and Recruitment Plan

In order to meet a target number of approximately 20 completed cognitive interviews, interview respondents were recruited via a sub-contracted recruitment firm, Nichols Research. Nichols Research is a full-service marketing research firm operating in the San Francisco Bay Area and Central California. During the last month of recruitment, AIR staff also recruited potential participants through e-mail and phone outreach to school administrators who have relationships with AIR through other research projects.

Recruited participants were targeted from a variety of locations as trained AIR-interviewers were available to conduct in-person interviews at school sites near five AIR offices – in the District of Columbia, Chicago, San Mateo, Boston, and Austin metropolitan areas – or could conduct remote interviews with participants anywhere in the United States. Given the diversity of locations across the country in which the cognitive interviews were held, NCES and AIR expected that those who participated would better represent the target population of schools from SSOCS than participants sampled from the same region or city. In order to adequately test the survey instrument with minimal selection bias, an attempt was made to distribute interviews across schools that represent a diverse cross section of the general population given their socio-demographic characteristics (i.e., percent white enrollment, total enrollment size, etc.).