2019 NSECE Supporting Statement Part A _clean_051719

2019 NSECE Supporting Statement Part A _clean_051719.docx

National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE): The Household, Provider, and Workforce Surveys

OMB: 0970-0391

The 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education:

The Household, Provider, and Workforce Surveys

0970-0391

SUPPORTING STATEMENT

Part A

Version: August 2018, Revision May 2019

Submitted By:

Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation

Administration for Children and Families

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

4th Floor, Mary E. Switzer Building

330 C Street, SW

Washington, D.C. 20201

Table of Contents

A. Justification 1

1. Necessity for the Data Collection 1

2. Purpose of Survey and Data Collection Procedures 2

3. Improved Information Technology to Reduce Burden 12

4. Efforts to Identify Duplication 12

Advantages of Extant Surveys 15

5. Involvement of Small Organizations 16

6. Consequences of Less Frequent Data Collection 16

7. Special Circumstances 16

8. Federal Register Notice and Consultations 16

Federal Register Notice and Comments 16

Consultation with Experts Outside of the Study 16

9. Incentives for Respondents 17

10. Privacy of Respondents 19

11. Sensitive Questions 20

12. Estimation of Information Collection Burden 22

13. Cost Burden to Respondents or Record Keepers 23

14. Estimate of Cost to the Federal Government 23

15. Change in Burden 24

16. Plans and Time Schedule for Data Collection and Deliverables 24

17. Reasons to Not Display OMB Expiration Date 24

18. Exceptions to Certification for Paperwork Reduction Act Submissions 24

List of Exhibits

Exhibit 1. 2019 NSECE Surveys, Questionnaires, and Sample Sources 9

Exhibit 2. 2019 NSECE Sample Types and Questionnaires 11

Exhibit 3. 2010 NSECE Field Test Return Rates by Experimental Group 19

Exhibit 4. Estimated Number of Burden Hours to Complete the Data Collection 22

Table of Attachments

Supporting Document |

Attachment |

2019 NSECE Center-based Provider Questionnaire Items - Overview and Comparison |

1 |

2019 NSECE Center-based Provider Screener and Questionnaire |

2 |

2019 NSECE Home-based Provider Questionnaire Items - Overview and Comparison |

3 |

2019 NSECE Home-based Provider Screener and Questionnaire |

4a |

2019 NSECE Home-based Provider Screener and Questionnaire (Spanish) |

4b |

2019 NSECE Classroom Staff (Workforce) Questionnaire Items - Overview and Comparison |

5 |

2019 NSECE Classroom Staff (Workforce) Questionnaire |

6a |

2019 NSECE Classroom Staff (Workforce) Questionnaire (Spanish) |

6b |

2019 NSECE Center-based Provider Survey Contact Materials |

7 (A-I) |

2019 NSECE Listed Home-based Provider Survey Contact Materials |

8 (A-I) |

2019 NSECE Classroom Staff (Workforce) Survey Respondent Contact Materials |

9 (A-H) |

2019 NSECE Listed Home-based Provider Survey Contact Materials (Spanish) |

10 (A-I) |

2019 NSECE Classroom Staff (Workforce) Survey Respondent Contact Materials (Spanish) |

11 (A-H) |

2019 NSECE Unlisted Home-based Provider Survey Contact Materials |

12 (A-E) |

2019 NSECE Unlisted Home-based Provider Survey Contact Materials (Spanish) |

13 (A-E) |

2019 NSECE Household Questionnaire Items - Overview and Comparison |

14 |

2019 NSECE Household Screener and Questionnaire |

15a |

2019 NSECE Household Screener and Questionnaire (Spanish) |

15b |

2019 NSECE Household Survey Respondent Contact Materials |

16 (A-I) |

2019 NSECE Household Survey Respondent Contact Materials (Spanish) |

17 (A-I) |

Comments Received in Response to 60-Day FRN and Agency Responses |

18 (A-B) |

Supporting Statement A

for the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education

A. Justification

1. Necessity for the Data Collection

This statement covers the main data collection effort for the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education (2019 NSECE), sponsored by the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children & Families (ACF), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Through a set of four inter-related surveys, the 2019 NSECE will collect information on (1) early care and education (ECE) services available (supply) to families with children ages birth through 5 years, not yet in kindergarten; (2) characteristics of the workforce providing these child care and early education services; and (3) households with children under age 13 years. These surveys of households, center- and home-based providers, and the center-based workforce will gather nationally representative information on the supply of ECE available to families across all income levels; the demand for ECE; the factors influencing parents’ choices and utilization of ECE for their children; and, the interaction of supply and demand-specifically the extent to which families’ needs and preferences coordinate well with providers’ offerings and constraints. The 2019 NSECE will generate a robust sample of providers serving low-income families of all racial, ethnic, language, and cultural backgrounds, in diverse geographic areas. Providers include programs that do or do not participate in the child care subsidy program; regulated, registered, or otherwise listed home-based providers; unregulated, or “unlisted,” home-based providers who are not on a registration list; and center-based programs (e.g., private, community-based child care, Head Start, and school-based settings).

The 2019 NSECE is preceded by the 2012 NSECE (OMB #0970-0391), which assembled the first national portrait of the demand for and supply of ECE in 20 years. The 2012 NSECE included a number of unique design features which have yielded significant contributions to the field regarding what we know about household demand for early care and education. These design features include a parental work and child care schedule; detailed questions on families’ child care search, perceptions, and decision-making process; the availability of geographical data on distance from child home to child care setting; and NSECE’s detailed coding conventions to accurately identify types and combinations of care used by all children under the age of 13 in a household. Thanks to the comprehensive information gathered by the NSECE, each of these topics have been/can be examined by a number of family, child, and community covariates including: household income-to-poverty ratio, child age, race/ethnicity, urbanicity, and poverty density of the community. Findings from the NSECE have been used to paint a nationally representative picture of the demand for early care and education and to inform states’ efforts at consumer education (National Center on Early Childhood Quality Assurance. (2017).

Published work from the NSECE has addressed a number of topics related to families’ child care search and perceptions. NSECE data related to child care search has addressed why families search for care, how many options parents have when selecting a care arrangement, how parents search for care- including where parents get information and what types of information they gather, the number and type of care arrangements considered, methods used to conduct a search (e.g., friends/family who knew provider, R&Rs, advertisements, provider reputation), and percent of searches that led to a change in arrangements (for detailed results, see NSECE Project Team, 2004; Mendez & Crosby, 2018). Multiple research teams have used NSECE data to examine parents’ perceptions of various types of early care and education (e.g., how they rate on being nurturing, educational preparedness, affordability, and flexibility). These studies have examined parental perceptions of care using a nationally representative set of families, Hispanic families, and low-income immigrants (NSECE Project Team, 2014; Sandstrom & Gelatt, n.d.; Guzman, Hickman, Turner, & Gennetian, 2016).

In addition to addressing families’ process and perceptions in selecting care arrangements, the NSECE has provided nationally representative and unique data on the types and combinations of early care and education used, cost, hours, and geographic distance between a child’s home and the location of the selected ECE provider. As with data on search and perceptions, findings on use of care have been published for a nationally representative sample, as well as for Hispanics, and low-income immigrants (for more information, see NSECE Project Team, 2016; NSECE Project Team, 2016; Crosby & Mendez, 2016; Sandstrom & Gelatt, 2017). In addition to collecting information on the combinations of care used, the NSECE is unique among national studies in the categories of care studied. These care categories distinguished home-based providers for whom there was/was not a prior relationship, as well as home-based providers that were paid or unpaid (for details, see NSECE Project Team, 2016).

Multiple policy and programmatic changes affecting the supply and quality of ECE have been implemented since the last fielding of the NSECE in 2012, making this an ideal time to re-map the ECE landscape. New federal legislation (e.g., CCDBG Act of 2014 and the Every Student Succeeds Act), funding opportunities (e.g., Preschool Development/Expansion Grants, Race to the Top-Early Learning Challenge (RTT-ELC) Grants, Early Head Start-Child Care Partnership Grants), and Head Start program performance standards have paved the way for improving the skills and credentials of the ECE workforce. These developments attempt to increase the quality of ECE more generally, and to increase the supply of affordable ECE providers. Likewise, state expansions of public pre-K, the Quality Rating and Improvement Systems (QRIS), and local initiatives focusing on improving community services from cradle to grave may also have contributed to enhanced ECE quality, supply, and affordability. The 2019 NSECE will collect information in a manner that facilitates comparisons with data collected for the 2012 NSECE and allows for examination of the changes in the characteristics of households and their use of non-parental care and the changing landscape of ECE programs during that seven year period. The importance of the quality of services provided to families and children underscores the need to better understand the characteristics of programs providing these services in order to inform federal, state, and local initiatives to improve them.

2. Purpose of Survey and Data Collection Procedures

Purpose of the NSECE

In addition to policy and programmatic changes since 2012, emerging research findings have advanced the field by identifying trends and policy-relevant issues that affect ECE. Together with those changes, recent research findings and trends in the following topical areas related to ECE serve as the foundation for the 2019 NSECE data collection: ECE access, ECE usage and supply, provider financing and affordability, quality/quality improvements, and workforce issues.

ECE Access. Since the last fielding of the NSECE, multiple policy and programmatic changes have been implemented to improve ECE availability, quality, and affordability, as well as parents’ awareness of ECE options. These changes have occurred at the federal, state, and local levels, such as the passage of recent federal legislation that carried with it new program rules and performance standards, and at the state level, through expansions of state public pre-K programs, QRIS, and scholarships designed to make high-quality care more affordable for low-income families. As with 2012, the 2019 survey of households will gather information about the characteristics of households with children under age 13-years, employment and non-parental care arrangements for all children in the household, and information about families’ preferences and choices of non-parental care to meet the needs of families and their children. The NSECE data will allow researchers to examine changes in the characteristics of households and their use of non-parental care, and whether significant developments since 2012 have addressed parents’ changing ECE needs. The 2012 and 2019 NSECE share key features of the design aimed at measuring local-level interactions of the supply and demand for ECE in the United States. As with 2012, the 2019 NSECE will allow analysts to measure the number of providers that are geographically close to households, the characteristics of those providers, and the number and ages of children served by those providers. The provider data include numbers of children served, by age of child and public funding source (Head Start, child care subsidies, public pre-kindergarten), among other characteristics. In addition, the 2019 provider questionnaires include questions about vacancies by age group to further describe local supply.

ECE Usage and Supply. The NSECE is uniquely designed to simultaneously map supply and demand – there is no other survey of ECE that accomplishes this at the national level. Because of this, the NSECE focuses at the same time on usage and availability of ECE services and allows analysts to describe the ECE supply proximate to households with specific characteristics and preferences. The 2012 NSECE provided a wealth of information on the state of the ECE market at that point in time. This survey identified the number of home-based providers caring for children ages birth to 13-years, including family child care providers, informal home-based providers, and family, friend and neighbors caring for children not their own (i.e., listed and unlisted providers, which refers to how these providers were sampled for the study).1 The 2012 NSECE served to deepen our understanding of the extent to which families’ needs and preferences coordinated well with providers’ offerings and constraints, and highlighted for the field the strong reliance of families (particularly low-income families) on unlisted providers, both paid and unpaid (National Survey of Early Care and Education, 2016a). It also highlighted the need for regulated care during non-standard hours and the need for infant/toddler providers, particularly in areas of high-poverty density and in rural areas (National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2016b). Recent research has substantiated and expanded these findings regarding unmet care needs and child care deserts, or areas that have few providers (Werner, 2016; Isaacs, Katz, Minton, & Michie, 2015; Anthony, Muenchow, Arellanes & Manship, 2016). The field has also advanced since the 2012 NSECE fielding in defining and measuring ECE supply and utilization, work that is incorporated into the 2019 NSECE surveys (Friese, Lin, Forry, & Tout, 2017). There are currently ten additional research teams analyzing restricted use 2012 NSECE data on questions linking local ECE supply and demand.

Provider Financing. The 2012 NSECE collected new, nationally representative data that advanced the field’s knowledge of the revenue and expenditures of ECE providers at that point in time. These data have been useful in comparing which types of care received government funding and revenue from other sources, calculating average fees by type of care and age of child, and comparing data on the costs/expenditures inherent in providing ECE. New issues related to provider financing have emerged since the administration of the 2012 NSECE, in part as a result of the NSECE findings, as several research and policy initiatives have brought significant focus on child care financing. As an example, both policy makers and researchers have a growing interest in the cost of care (i.e., what is involved in both monetary and in-kind supports to provide care), in addition to the price of care (i.e., what the consumer is charged), as important factors in understanding how programs can provide high quality care. Certain features of ECE that are considered indicators of quality (such as group size, child to caregiver ratios, staff qualifications, training and professional development, the physical environment, and curriculum) are associated with improved child outcomes, but these factors also have cost implications for the provider (Caronongan, Kirby, Boller, Modlin, & Lyskawa, 2016).

The 2019 NSECE will further our understanding of the link between cost and price of care, on one side, and features of quality, on the other, by collecting data related to programs’ costs, advertised price, and the mix of funding sources and in-kind supports used to address costs in different ECE settings. The 2012 NSECE established the first nationally-representative incidence rates of providers blending or braiding funding, but the availability of these rates now introduces new questions about how providers are using their multiple funding streams (e.g., within classrooms or among children). Through the addition of targeted new questionnaire items and analyses, the 2019 NSECE will further attempt to distinguish methods of blending and braiding funding to better describe multiple-funded centers. The 2019 NSECE center-based provider survey will make it possible to categorize centers and classrooms by their unique funding situations. One survey item requests information about the number of children in the center who are funded by each public funding source (e.g., CCDF, Head Start, Pre-K). Another set of items asks whether the center serves children who have specific combinations of funding to cover their care (e.g., “Head Start + CCDF”). Finally, an item assesses the funding sources for children enrolled in a randomly-selected classroom (e.g., CCDF, Head Start, Pre-K). Taken together, these items allow us to ask questions such as, “How many ECE centers serve both Head Start and Pre-K children?” and “How many classrooms have both Head Start and Pre-K children enrolled?” In addition, the survey asks center directors how they manage performance standards from multiple funding sources. These questions will provide information on whether centers apply the standards to all classrooms, or only to those classrooms for which the standards are required due to funding.

Quality and Quality Improvements. Despite more than two decades of research focused on the importance of early childhood quality (Yoshikawa et al., 2013), quality of care in early childhood settings (as currently defined and measured) still typically remains in the low to moderate range. Higher quality tends to be found in more formal and highly regulated programs, such as child care centers, state pre-K, and Head Start, than in informal settings such as family child care homes and unlicensed care providers (Bassok, Fitzpatrick, Greenberg, & Loeb, 2016). Although the 2012 NSECE did not include observational measures of quality, data related to structural predictors of quality 2 (e.g., provider education, use of a curriculum) also reflected these differences by type of care, with center-based programs scoring higher than listed home-based providers across multiple indicators (National Survey of Early Care and Education, 2015).

Efforts to improve quality since 2012 include the expansion of QRIS (Tout, Epstein, Soli, & Lowe, 2015), modifications to program standards, and the use of monitoring to formalize expectations regarding structural quality, such as teacher education, curriculum, and group size (Maxwell, Sosinsky, Tout, & Hegseth, 2016). At the federal level, the Preschool Development Grants administered by the Departments of Education and Health and Human Services have aimed to help states build or enhance their infrastructure to provide high-quality preschool programs, or to expand high-quality preschool programs. Also, both the Head Start program and the Child Care Development Fund, have received significant increases in funding that allocated specific dollars for quality improvement activities.

Also needed are additional data on how quality improvement efforts are being received by providers (e.g., how they are experienced, what supports providers are using) and whether they are associated with increased quality. In particular, data are needed on how quality improvement efforts are associated with the actual improvements in quality in two settings that tend to be associated with lower quality ratings: infant/toddler classrooms and family child care settings. The 2019 NSECE will provide needed data on the implementation of instructional supports, curricula, and quality improvement, topics emphasized by recent federal policies and programs.

Workforce. Estimates from the 2012 NSECE provided the first counts of ECE workers since 1990, their professional qualifications, and their compensation (National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2013). Research since the 2012 NSECE has focused on the importance of strengthening practitioner competencies and qualifications as a necessary means to improve program quality. The decentralized nature of the ECE workforce poses challenges in systematically providing additional education and development opportunities (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academies, 2015). Nevertheless, there is an interest among ECE stakeholders in identifying the multiple access routes to increased professional development for the ECE workforce, especially for those who are new to the field or who currently lack state and/or national certification (Limardo, Hill, Stadd, & Zimmer, 2016). Some recent work in this area has focused on the preparation and ongoing continuing professional development of those ECE providers who care for infants and toddlers (Epstein, Halle, Moodie, Sosinsky, & Zaslow, 2016; Madill, Blasberg, Halle, Zaslow, & Epstein, 2016).

Another area of interest is the compensation received by ECE workers (Whitebook, McLean, & Austin, 2016; National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2013; Whitebook, Phillips, & Howes, 2014). Because the 2019 NSECE includes a sample of both listed home-based and center-based providers, analyzing the 2019 state of ECE workforce compensation, as well as shifts in the workforce (e.g., in response to market shifts such as the expansion of public pre-K) will be possible. Finally, there is also a growing interest in the mental health of ECE workers and its relationship to providing quality care and child outcomes (Raver, Blair, & Li-Grining, 2012; Madill, Halle, Gebhart, & Shuey, 2018). The 2019 NSECE questionnaires for ECE workers (the home-based provider and classroom staff (workforce) questionnaires, Attachments 4a/4b and 6a/6b, respectively) include a measure of depression.

The NSECE 2019 effort will build upon the 2012 NSECE by focusing both on supply of ECE providers and families’ demand for ECE, with a goal of understanding the interaction of supply and demand in 2019 and assessing the changes that have occurred since 2012. The revised 2019 NSECE questionnaires (Attachments 2, 4a/4b, 6a/6b, and 15a/15b) incorporate questions related to research findings and policies regarding ECE access, ECE usage and supply, provider financing and affordability, quality/quality improvements, and workforce issues; these areas of inquiry will be included in the analysis of the 2019 NSECE data.

The NSECE is not designed to measure barriers of entry for potential providers, given that only ECE providers currently operating in the field are included in the sample. The NSECE does not include providers who considered entry into the ECE field but did not enter or providers who have left the ECE field. That being said, the NSECE allows comparisons of providers with different lengths of experience and duration, such as those who have been in the field 0-5 years, 5-10 years, 10 or more, and so on. Comparisons of new entrants between 2012 and 2019 may be informative about changes in opportunities and barriers to entry between the two time periods.

Research Questions

The 2019 data collected will address the following questions:

What is the level of need and utilization for different types of ECE programs by important demographic characteristics of families and children (e.g., household income, family structure, employment status, links to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) reauthorization, and other programs; social supports; ages of children; racial, ethnic, and language minority status; non-traditional work hours, etc.)?

How are families combining parental care and/or ECE of different types to cover the hours they need care for?

What is the availability of unlisted home-based non-parental care and early education programs by neighborhood, county, or other geographic unit?

What are the characteristics of programs providing care and early education? How much are these characteristics determined by federal, state, and local policies and standards?

How well is the availability of ECE programs meeting the needs of parents and children-how aligned are supply and demand?

Are there differences by type of ECE program (e.g., family, friend, and neighbors; center care; faith-based providers; Head Start; public pre-K) in the degree to which the services offered to families meet their needs and those of their children?

Which families need and want child care subsidies?

How well are programs that provide subsidies and other assistance to access ECE (e.g., Head Start, state pre-K) to working families meeting their needs?

What percentage of their income are families able and willing to spend on ECE?

How and why are parents making decisions about the ECE programs they choose?

What features of programs do parents consider in choosing care?

Do parents feel that they have real choice of care?

How much do parents take into account information about the quality of care available to them in choosing care and early education?

What motivates providers to provide ECE?

How well aligned are the goals of programs with the wishes of parents for programs for their children?

Is there congruence between the cultural, ethnic, racial, and language characteristics of providers and the children they serve?

What is the availability of non-parental care and early education services by neighborhood, county, or other geographical unit?

What are the characteristics of programs/providers supplying ECE?

How much do these characteristics vary by federal, state, and local policies and standards?

How does the availability and characteristics of ECE providers compare to what was observed in 2012? Has the availability of listed home-based child care changed? Has the availability of care for infants and toddlers changed?

What are the characteristics of the ECE workforce (i.e., teachers, caregivers)?

What motivates teachers/caregivers to offer ECE services?

What services do ECE providers offer to parents and children?

What are the characteristics (e.g., schedules, rules, comprehensive services) of the care they offer?

How do providers identify and respond to children of diverse language backgrounds, children with special needs, homeless families, or other specific populations?

How much are providers charging for ECE for children of different ages and in different kinds of programs?

What proportion of revenues from provision of ECE is covered by parent fees? What proportion is covered by other sources?

How do providers blend funding from different sources (e.g., child care subsidies, contracted slots, Head Start, state pre-K funding, Title I, The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), other private funding) to cover the costs of serving children from households of different incomes?

How does blended funding contribute to differences across providers? How do funding sources contribute to differences within programs (e.g., variations in characteristics of the workforce in classrooms within a program)?

Which providers are willing and able to participate in the child care subsidy program? Which other public programs do they participate in (e.g., Child and Adult Care Food Program)?

What is their role in helping parents navigate access to child care subsidies?

What are barriers to participation in subsidy programs (e.g., administrative practices, reimbursement rates)?

Do providers serving subsidized children charge fees in addition to parent co-pays? Do they waive additional fees and/or co-pays? How do providers determine parent co-pays?

How do predictors of quality (e.g., participation in professional development activities; use of curriculum) vary across providers (e.g., by funding sources, settings, geographic area, populations served, community characteristics)?

How do predictors of quality in classrooms (e.g., use of a curriculum, group size) compare to predictors of quality at the program-level (e.g., financial support for teacher professional development, staff departure rates)?

What is the relationship between the prices charged for providing care and predictors of quality?

Which providers are most likely to serve specific populations, including dual language learners, infants and toddlers, children with disabilities, children experiencing homelessness, and families who need care during non-standard hours? Do families who need care during non-standard hours have a range of choices among ECE programs?

How does the availability of child care and early education relate to community characteristics or characteristics of families with young children in similar geographic areas, as measured in other national surveys (e.g., The American Community Survey (ACS), The National Household Education Surveys Program (NHES))?

Universe of Data Collection Efforts and Study Design

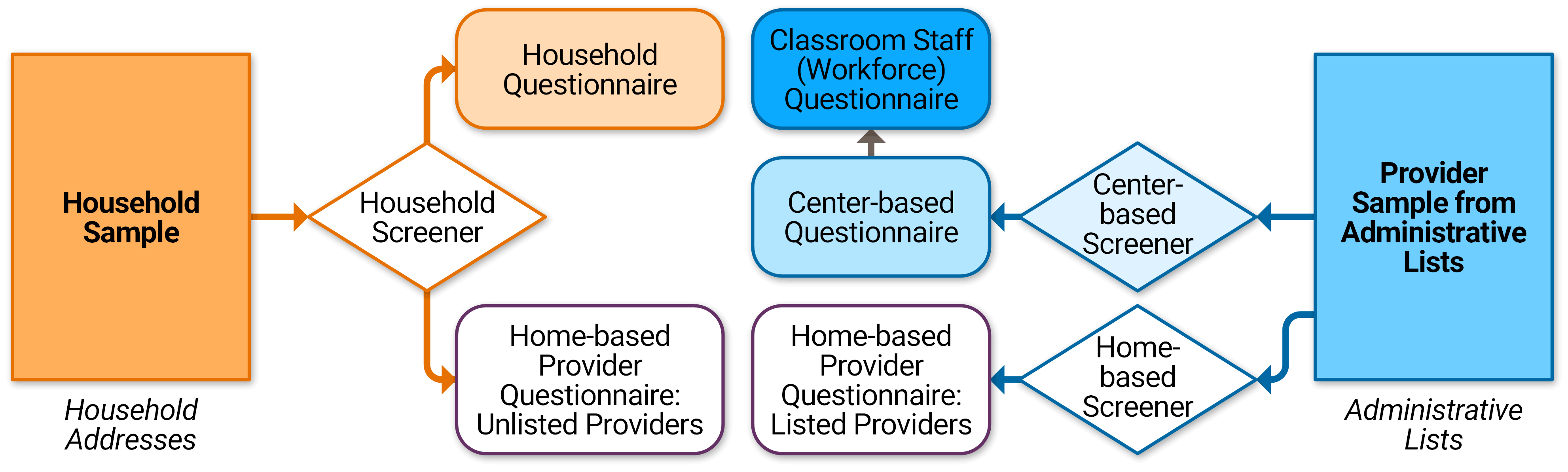

The 2019 NSECE will include four inter-related surveys comprised of three screeners and four questionnaires shown in Exhibit 1 below.

Exhibit 1. 2019 NSECE Surveys, Questionnaires, and Sample Sources

Survey |

Screener/Questionnaire |

Sample Source |

Household survey |

Household screener |

Address-based sample |

Household questionnaire |

Eligible households identified through household screener |

|

Home-based provider survey |

Home-based provider screener |

Administrative lists (for listed home-based providers) |

Home-based provider questionnaire |

Eligible providers identified through home-based provider screener (listed home-based providers) and

Eligible providers identified through household screener (unlisted home-based providers) |

|

Center-based provider survey |

Center-based provider screener |

Administrative lists |

Center-based provider questionnaire |

Eligible programs identified through center-based provider screener |

|

Classroom staff (workforce) survey |

Classroom staff (workforce) questionnaire |

Eligible classroom staff identified through completed center-based provider questionnaire |

The household screener will be administered to all sampled households to determine eligibility to complete the household questionnaire (households with at least one child under age 13) and/or the home-based provider questionnaire (individuals who provide care in a residential setting for one or more children under age 13 who are not their own at least five hours per week).

The household questionnaire will be conducted with a parent or guardian of a child or children under age 13. Eligible respondents will be identified through the household screener.

The home-based provider screener will be administered to sampled home-based providers identified through administrative lists to determine eligibility to complete the home-based provider questionnaire. Eligible providers will be individuals who provide care in a residential setting for one or more children under age 13 who are not their own at least five hours per week.

The home-based provider questionnaire will be completed by eligible home-based providers identified through two separate sample sources (the address-based household sample and the administrative list sample). Unlisted home-based providers will be identified by administering the household screener to the address-based sample. Listed home-based providers will be identified through screening the providers sampled from state or national administrative lists.

The center-based provider screener will be completed with all sampled center-based providers who are identified from administrative lists such as state licensing lists, Head Start program records, lists of elementary schools, or pre-K rolls. The screener will verify the selected provider’s information and collect any new/additional information about providers operating at that site that were not included in the sample frame.

The center-based provider questionnaire will be completed with administrators, directors, or other leaders of ECE centers who are determined eligible and sampled for inclusion through the center-based provider screener.

The classroom staff (workforce) questionnaire will be completed with classroom-assigned staff at sampled center-based provider locations. After each center-based provider questionnaire is completed, classroom-assigned instructional staff from that organization will be sampled and approached for the classroom staff (workforce) questionnaire.

Exhibit 2 below provides an overall schematic of the NSECE sample types and questionnaires outlined above. For more detailed information about the full sampling plan, see Supporting Statement B, Section B1. From the household (address-based) sample, the household screener will identify 1) households eligible to complete the household questionnaire, and 2) individuals eligible to complete the home-based provider questionnaire (unlisted home-based providers). The address-based sample will include an oversample of low-income families.

For home-based providers and center-based providers, we will build a national sampling frame of all “listable” providers of ECE services and sample programs from that frame to be screened for eligibility. This frame is built from state-level lists of center-based and home-based providers, national lists of ECE providers (e.g., Office of Head Start, accreditation list from the National Association for the Education of Young Children), and ECE provider lists maintained federal agencies like the Department of Defense and the General Services Administration. We supplement these sources with a commercially available list of all K-8th grade elementary schools to capture ECE programs that do not appear on state lists. These lists together provide us with a comprehensive source for ECE programs that interact with public agencies such as licensing agencies and school districts. Other types of individual ECE providers, like nannies or individuals who appear on lists like Care.com for instance, will be identified through screening of the household sample. Programs determined eligible through the respective sample type screener are then selected for the corresponding provider questionnaire. Respondents for the classroom staff (workforce) survey will be randomly selected from a classroom staff roster built in the center-based provider questionnaire. Home-based caregivers/teachers sampled for the home-based provider survey will respond to questions parallel to those in the classroom staff (workforce) questionnaire regarding their caregiving/teaching activities and experiences as members of the ECE workforce.

Exhibit 2. 2019 NSECE Sample Types and Questionnaires

Overview of Questionnaires

The center-based provider questionnaire (Attachment 2) is designed to collect a variety of information about the provider, including structural characteristics of care, revenue sources, enrollment, admissions and marketing, enumeration of staff (instructional/non-instructional), and respondent demographics. One feature of the questionnaire is a section collecting information about a randomly selected classroom or group, including characteristics of all instructional staff associated with that classroom/group.

The classroom staff (workforce) questionnaire (English and Spanish version Attachments 6a and 6b, respectively) collects information from classroom-assigned instructional staff working in center-based programs. Items cover: personal characteristics (demographic, employment-related, education/training); classroom activities (teacher-led/child-led, active/passive); classroom characteristics (enrollment, instructional staff, and child demographics); attitudes and orientation toward caregiving (perception of teacher role, parent-teacher relationships, job satisfaction, worker well-being); and work climate (provider program management, opportunities for collaboration and innovation, support for professional development).

The home-based provider questionnaire (Attachment 4a/4b) covers many of the same topics as the center-based provider questionnaire described above. Additional topics include the household composition of the provider, questions trying to understand the proportion of household income coming from home-based care, and characteristics of the care provided to children. Listed home-based providers are eligible for a number of additional items regarding the type of care provided, which are asked to more formal or market-based providers, including use of curriculum, membership in professional organizations, specific professional development questions, background checks, and inspections.

The household questionnaire (Attachment 15a/15b) collects information on a variety of topics including household characteristics (such as household composition and income), parents’ employment (employment schedule, employment history, etc.), the utilization of ECE services (care schedules, care payments and subsidies, attitudes towards various types of care and caregiver, etc.), and search for non-parental care. The respondent is a parent or guardian in the household who is knowledgeable about the ECE activities of the youngest child in the household.

3. Improved Information Technology to Reduce Burden

The 2019 NSECE will employ a multi-mode data collection approach that achieves significant cost efficiencies for the government while giving respondents flexibility to select a more convenient mode to complete their questionnaires as the data collection period progresses. The project will emphasize the convenience of web survey completion for all provider surveys, as well as the household screener, and will subsequently offer telephone and in-person questionnaire administration options. A paper self-administered questionnaire (SAQ) option will also be available for the classroom staff (workforce) questionnaire and household screener for respondents to use as needed. Telephone, in-person, and web surveys all reduce respondent burden and produce data that can be prepared for release and analysis faster and more accurately than is the case with pencil-and-paper surveys.

The project will also employ tablet technology to support field interviewer screening, prompting, and interviewing for the 2019 NSECE, which will further reduce respondent burden. Particularly, using tablets will allow interviewers to quickly text and email provider questionnaire URLs while talking with respondents, and allow interviewers to deliver technical support instantly to respondents on completing the web questionnaire.

4. Efforts to Identify Duplication

Three extant national surveys collect data on ECE characteristics and utilization patterns. These surveys are the National Household Education Survey, Early Childhood Program Participation (NHES: ECPP), the Survey of Income Program Participation (SIPP), and the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 2010-11 (ECLS-K: 2011).

While these three national surveys may address some of the data needs relative to households with children, there are no data collection efforts aimed at understanding the institutions, professionals, and individuals working directly with children, as well as the relationship between the changing needs of families and these ECE resources.

The NHES: ECPP is a repeated cross-sectional mail survey (previously a telephone survey) of households with children ages 0-6 (not yet in kindergarten) that focuses on children's participation in center- and home-based non-parental care and education programs, as well as characteristics of ECE arrangements. It is conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), and has been administered in 1991, 1995, 1999, 2001, 2005, 2012 and 2016.

The SIPP, conducted by the U.S. Bureau of the Census, is a multi-panel longitudinal survey of adults, and includes a Child Care Topical Module, which was designed to establish an ongoing database of child care statistics at the national level. Data from the SIPP were last collected in 2014.

The ECLS-K: 2011, also conducted by NCES, is a nationally representative longitudinal study that has followed the same children from kindergarten (2010-2011) through the fifth grade. The study has been designed to help better understand children’s development and experiences in the elementary grades. Between 2010 and 2016, information was collected from children, their families, their teachers, their schools, and their before- and after-school care providers across the United States. As part of a broader set of questions about their child, parents reported on the child’s care arrangements, including the type of care and when care was provided. The study also interviewed center-based and home-based providers, who reported on their qualifications, classroom activities, and program characteristics. In 2019, the ECLS-K: 2011 sample will be around 14 years of age, so these respondents will not overlap with the 2019 NSECE child population of interest.

The NSECE differs from these studies in several important ways:

NSECE measures both ECE supply and demand. Because policy makers and administrators seek to maximize parental choice for ECE, it is important to understand how choices are made, as well as the ECE options that are available in a local market. Both the SIPP and NHES: ECPP collect data solely from households. Although parental preferences and ECE utilization are measured by the SIPP and NHES: ECPP, this information lacks the context of what was available to families. The ECLS-K: 2011, on the other hand, collects data from both parents and providers, but this information is used largely to provide context for the sampled child’s growth and learning over the years, not to provide context for parents’ ECE choices. Because the NSECE will allow for a comparison of data collected from both households and ECE providers, analyses of parents’ ECE choices as well as their decision-making process will be contextualized with detailed information about a sample of available providers in their area. We will, for example, be able to contrast a parent’s assessment of available ECE providers with the actual availability of ECE providers. This improved data will allow for policy makers at the federal and state levels to make more informed decisions about how to improve the fit between what is needed and wanted and what is actually available.

Low-income oversample. While the NHES: ECPP and SIPP provide national estimates of child care utilization patterns, they do not oversample low-income households, with the exception of the 1990 and 1996 SIPP panels which oversampled households from areas with high poverty concentrations. The NHES has oversampled Black and Hispanic households, and in recent years, sorted tracts by poverty in their sampling process. As such, NHES and SIPP are limited in their ability to address key policy questions, such as differential child care utilization patterns among families by income or among low-income families who do and do not receive assistance paying for their ECE arrangements. The NHES: ECPP and SIPP data are particularly limited in analyses examining patterns among subgroups that consider combinations of characteristics, such as employment and income or race/ethnicity and income. The proposed design of the 2019 NSECE will oversample low-income households to allow for these important subgroup analyses.

Inclusion of unlisted home-based providers. This study will allow for a more thorough understanding of the role of unlisted home-based providers in ECE. While the SIPP collects data on whether care was provided by a friend, neighbor, nanny, or au pair, it does not distinguish who among these is providing care. Additionally, the SIPP does not collect data on pre-existing or personal relationships with providers or whether the provider cares for other non-related children. NHES: ECPP collects data on whether a non-relative is providing care, whether the care is provided at the child’s home or elsewhere, and whether the provider was someone the child’s parents already knew. However, the study does not collect information on whether other unrelated children are cared for by the provider. Therefore, friend and neighbor and family care providers cannot be distinguished with accuracy from other non-relative providers. The ECLS-K: 2011 collected data on whether the sampled child was cared for by relatives, how often and when that care occurred, and whether that caregiver received payment for the care they provide. Yet, because these data were collected in reference to the sampled child, they provide little insight into the household’s larger ECE usage patterns and are unable to situate these choices within the larger local context of what is available in their surrounding community. The NSECE will provide data to describe and analyze which American families use unlisted home-based providers, and how their availability varies by community, socioeconomic status of families, and formal child care market characteristics. We will also be able to understand the demographic characteristics of these providers and how they see their role in caring for children and helping the parents of these children. Research on these topics is important for policy makers as they may inform decisions regarding subsidies paid and professional development available to unlisted home-based providers.

Includes multiple children in household. The NSECE will provide detailed information about the ECE arrangements of all children in a household age 12 or younger. These data will include the type (or combinations) of arrangements, descriptions of providers, number of hours of care in ECE arrangements, where ECE services are provided, and the cost of the ECE. While the ECLS-K: 2011 collected detailed information on the different care arrangements, schedule of care, and location of care, these data are collected only for the sampled child. Further, the NHES: ECPP only provides data on the children in the household between the ages of 0 to 6, not yet in kindergarten. Additionally, though the SIPP Child Care Module collects information about all child care arrangements for all children under 15 in the household, it does not collect key pieces of information that the NSECE will measure, including parents’ strategies for gathering information about the provider, activities offered in the ECE setting, and language spoken at the ECE setting. Furthermore, the questions used in the NSECE to define type of ECE are more detailed than those asked in the SIPP.

Includes detailed parental work schedule. The NSECE household questionnaire also captures data that allows us to understand how parental schedules for work-related activities, including during standard office hours vs non-standard hours of the week, constrain and influence parents’ selection and use of ECE. Along with other rich data from the household and provider surveys, this schedule information will provide a highly specific aggregate description of the match between parental search requirements for ECE and the actual utilization of ECE. These data are more comprehensive than those collected through the SIPP Child Care Module, which addresses child care utilization and employment schedules, but not the search process or parental preferences. Additionally, though both the NHES: ECPP and ECLS-K: 2011 include items about parental employment, they do not ask parents or regular caregivers to describe their work-related schedules in detail, nor in conjunction with their spouses’/partners’ schedules and/or their children’s ECE participation. . Taking into account issues of irregular hours, non-traditional hours, and commute times, the NSECE will provide valuable information about the role of ECE in enabling Americans to participate in the workforce.

Allows for 51-state sample. The NSECE will employ a 51-“state” design (50 states and the District of Columbia), which will permit analysis of policy variation across states. Many of the specific decisions states face depend on market dynamics — how to strengthen regulatory and quality rating standards, what reimbursement rates and co-pay schedules to set, and what incentives to provider organizations and individual staff can produce higher quality in a cost-effective manner. The answers depend on the interaction of supply and demand within a local market, and thus, market data must be gathered at the state and local, not just the national level. The SIPP and ECLS-K: 2011 samples only allow for state-level analyses in a sub-set of states,3 while the NHES provides national cross-sectional estimates of child care demand for each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia.4

Advantages of Extant Surveys

Although the unique strengths of the NSECE are of primary focus above, the NHES: ECPP, SIPP, and ECLS-K: 2011 have the advantage of collecting data over time. For example, the NHES: ECPP collects repeated cross-sectional data, allowing for an analysis of ECE utilization over time. Likewise, the SIPP collects longitudinal data from cohorts of participants, allowing for tracking of parents’ ECE usage and receipt of financial support for child care over time. The ECLS-K: 2011 tracks children’s growth and development through the elementary schools grades, collecting data on the types of school programs in which children participate, as well as ECE arrangements, children’s cognitive development, and household characteristics.

The NSECE, by contrast, is the only nationally representative survey of ECE providers and workforce across sectors and funding streams. Since 2012 there have been significant changes in the ECE landscape that make the 2019 data collection effort much needed. For example, new legislation (e.g., CCDBG Act of 2014 and the Every Student Succeeds Act), funding opportunities (e.g., Preschool Development/Expansion Grants, RTT-ELC, etc.), and program standards have been introduced in an effort to better ECE providers and make quality care more accessible to all families. These changes make it a critical time to collect updated information to examine what impact they have had on ECE services and how we can further inform federal, state, and local initiatives to improve ECE quality, utilization, and affordability.

5. Involvement of Small Organizations

Data collection for the NSECE may impact small organizations involved in the administration of center- and home-based provider surveys. All efforts will be made to minimize the burden of survey participation on these providers. Use of multiple possible modes of data collection and opportunities to designate delegates for some portions of the center-based provider questionnaire are among the ways in which burden will be lessened.

6. Consequences of Less Frequent Data Collection

The 2019 NSECE is proposed for one-time collection of data; no reduction in frequency is possible.

7. Special Circumstances

None of the listed special circumstances apply.

8. Federal Register Notice and Consultations

Federal Register Notice and Comments

In accordance with the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995 (Pub. L. 104-13) and Office of Management and Budget (OMB) regulations at 5 CFR Part 1320 (60 FR 44978, August 29, 1995), ACF published a notice in the Federal Register announcing the agency’s intention to request an OMB review of this information collection activity. This notice was published on February 13, 2018, Volume 83, Number 30, page 6187, and provided a sixty-day period for public comment. During the notice and comment period two comments were received – one an endorsement of the project and the second substantive comment with response attached. The 2019 NSECE added the household and unlisted provider surveys after the 60-day Federal Register Notice was published; the public will have the opportunity to comment on these additions in response to the 30-day Federal Register Notice, which published on August 15, 2018.

Consultation with Experts Outside of the Study

The 2019 NSECE held the first meeting of its Technical Expert Panel (TEP) in December 2017. The TEP provides insight and content and technical expertise on various project activities, including informing decisions about the content areas for ECE research, technical elements of survey design, and administration and analysis. The TEP also shares with OPRE and the project team research-related issues from the ECE field. Expert panel members come from research organizations and universities and include the following individuals:

Peg Burchinal

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Elizabeth Davis

University of Minnesota

Anne Douglass

University of Massachusetts, Boston

Julia Henly

University of Chicago

Iheoma Iruka

High Scope Educational Research Foundation

Herman Knopf

University of Florida

Lynn Karoly

RAND Corporation

Michael Larsen

Saint Michael’s College, Vermont

Beth Rous

University of Kentucky

Heather Sandstrom

Urban Institute

Holli Tonyan

California State University at Northridge

A second expert panel, the 2019 NSECE Content Advisory Team (CAT), has been developing the 2019 NSECE questionnaire design and analysis and reporting strategy that builds on the 2012 NSECE instrumentation and analytic products. The CAT members have the highest order expertise in each ECE topical area and include the following individuals:

Nicole Forry

Child Trends

Kathleen Gallagher

University of Nebraska, Kearney

Robert Goerge

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago

Patricia del Grosso

Mathematic Policy Research

Erin Hardy

Brandeis University

Gretchen Kirby

Mathematica Policy Research

Rebecca Madill

Child Trends

Roberta Weber

Oregon State University

Wladimir Zanoni

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago

Martha Zaslow

Society for Research in Child Development

9. Incentives for Respondents

We propose the use of incentives as part of the overall data collection strategy for the 2019 NSECE for the following reasons:

To ensure that data collection can be completed as much as possible during the school year. Known patterns in ECE usage and supply among households and providers during the summer months mean that additional questionnaire changes would be necessary to protect data quality and comparability of data across cases if summer data collection were necessary.

To minimize bias in estimates.

To ensure that target sample sizes are achieved. Target sample sizes are required to support high priority subgroup analyses, especially families receiving child care subsidies and ECE providers and workers in rural areas.

We base our rationale on data from incentive experiments conducted in 2011 for an NSECE field test and on outcomes of the 2012 NSECE data collection.

Provider Survey Incentives

Listed home-based provider: $2 pre-paid incentive with mail invitation. We will include a $2 in the advance letter sent to listed home-based providers. In 2012, we found that 23 percent of home-based providers sampled from state licensing and other national lists were not providing care to young children at the time of data collection. To better support early identification of ineligible sample in 2019, a $2 incentive will be included in the initial sample mailing (Attachments 8A/10A) to encourage self-reporting of eligibility status. This additional screening step will allow for resources to be spent targeting critical subsample groups to ensure full sample representation rather than efforts spent on nonresponse prompting with ineligible sample members.

Listed home-based provider and classroom staff: small in-kind gifts. In-kind gifts worth no more than five dollars help build rapport and trust, leaving sampled providers and staff more receptive to our contacts and more willing to provide other contact information (i.e., cell phone number and email address) to receive additional study information. These gifts also provide field interviewers with another reason to approach sample members whom they have already attempted to contact in the past without success. Specific guidelines will be provided to interviewers about when these gifts can be used and how they can be incorporated strategically into contact attempts.

Household Survey Incentives

The household survey uses a combination of a pre-paid incentive for screening and a post-paid incentive for survey completion.

Household pre-paid incentive. With nearly 100,000 households to be screened, a $2 incentive will be included in the first screener letter (Attachment 16A) to screen households more effectively by mail prior to the start of field outreach. A successful mail screening effort will allow us to preserve field resources to be used later for harder to reach populations. Research about the effectiveness of incentives with household surveys has found that pre-paid mail incentives have a larger impact per dollar than pre-paid incentives by other modes or post-paid incentives (Mercer, et al., 2015). The 2019 NSECE household screener incentive model is based on findings from the 2010 field test, in which an incentive experiment was conducted testing the effectiveness of a $1 incentive in the first screener mailing (group 1) versus no incentive in the first mailing and a $5 incentive in the second mailing (group 2). The experiment showed that the $1 coin yielded higher mail screener completion rates and its effect may even have extended into field data collection where that group had higher screening completion rates as well. Because of the significant processing and postage costs of mailing $1 coins and similar benefits in the literature of $2 bills as incentives, we mailed $2 bills in the 2012 NSECE and propose to do the same for the 2019 NSECE.

Exhibit 3. 2010 NSECE Field Test Return Rates by Experimental Group

|

$1

Coin at Initial Mailing, $0 at |

$0 at Initial Mailing, $5 at Follow-up |

Difference |

Return Rate at First Mailing |

13.6% |

4.9% |

8.8% |

Return Rate at Second Mailing |

8.8% |

14.6% |

-5.8% |

Total Return Rate |

21.1% |

18.6% |

2.5% |

In-Field Screener Completion Rates |

72.5% |

64.3% |

8.2% |

% Eligible for Household Survey |

29.1% |

28.4% |

0.7% |

% Eligible for Home-based Provider Survey |

3.8% |

2.3% |

1.5% |

Household post-paid incentive. The second incentive stage will be a $20 post-paid incentive for respondents eligible for and completing the household survey. This is consistent with the 2012 NSECE incentive for the household survey.

10. Privacy of Respondents

Respondents will receive information about privacy protections throughout the recruitment process and when they consent to participate in the survey. Privacy concerns will be addressed first through letters introducing sampled providers, staff, and households to the survey (Attachments 7A, 8A, 9A, 10A, 11A, 12A, 13A, 16A, and 17A) and will continue through with any follow-up contacts (see Attachments 7-17). Frequently asked questions (Attachments 7H, 8H, 9G, 10H, 11G, 12E, 13E, 16H, and 17H) will be printed on the back of letters explaining how we protect respondent information and use the data collected through the questionnaire. Interviewers are also trained to understand the survey’s privacy protocols; discuss privacy concerns with sampled providers, staff, and households; and answer any related privacy questions. Finally, each questionnaire contains carefully worded consent statements explaining in simple, direct language the steps that we will take to protect the privacy of the information provided.

The 2019 NSECE has also obtained a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to further protect the identities and information of respondents from disclosure. We have submitted consent forms and other materials with language appropriate for a project with a Certificate.

Safeguards for the security of data include: storage of printed survey documents in locked spaces, protection of computer files against access by unauthorized individuals and groups through a multi-tiered approach of access control and monitoring, data encryption during transmission, and continuous upgrade of plans and policies. Information will not be maintained in a paper or electronic system from which data are actually or directly retrieved by an individuals’ personal identifier.

ACF intends to make the NSECE data available to policy makers and researchers during (and well beyond) the period of the NSECE contract. Similar to the 2012 NSECE data, any 2019 NSECE data posing disclosure risk will be released under restricted use or other protected data provisions. A primary challenge of this task is to maximize access to the data while ensuring the privacy of respondents. For the 2012 NSECE, the agency provides multiple tiers of access to data files. Five tiers of data files vary in privacy and restrictions on access, with two being unrestricted-access public-use files and three restricted-use files. Key differences between public- and restricted-use files are the overall risk of identification of sampled entities (from minimal risk to direct identification of providers needed for linkage to administrative records); the level of geography included in each file (from large areas such as Census region to precise coordinates of providers needed to calculate distance, such as provider to work); and the extent to which variables are edited to mask against disclosure. Similar data security and privacy protocols are anticipated for the 2019 NSECE data.

11. Sensitive Questions

At the close of the household questionnaire, respondents are asked to provide consent for the project to access administrative records from government subsidy programs. Respondents (parents or guardians) who grant such consent are then asked to provide the full names, dates of birth, and the street address of their children under age 13. (Please see the household questionnaire, Attachment 15a/15b, Section H for these items.) Such sensitive information is required in order to match administrative records to survey data. The availability and use of child care subsidies is a key research topic of this study. These data require extensive questionnaire batteries for collection and are even then very difficult for parents to report accurately. Collection of administrative records would improve the quality of subsidy-related analyses that could be completed using the NSECE data. Respondents are free to refuse consent for records access, and in this case will not be asked for personal identifying information.

Additionally, the home-based provider and classroom staff (workforce) questionnaires ask respondents to report their total household income the year preceding questionnaire completion (calendar year 2018). The household questionnaire includes a section on household characteristics with questions regarding the respondent’s total household monthly and annual income (for the month/year prior to questionnaire administration). All questionnaires ask respondents to report income as an exact dollar amount. Since income may be difficult to remember or report, if respondents do not know or refuse to provide this information the questionnaires then ask them to describe income by pre-defined approximate ranges, such as less than $15,000, $15,001 to $22,500, and so on. In a separate section, the household questionnaire also asks about annual household income to determine eligibility for questions related to child care subsidies. This question narrows income to a single approximate range category based on the number of reported children and individuals per household, and asks respondents to report if their income is below or above this threshold that approximates 200 percent of the federal poverty line. This allows only household respondents who are below a certain income threshold to receive these child care subsidy questions, thereby reducing overall respondent burden.

Last, the home-based provider questionnaire may raise additional concerns about disclosure, such as individuals without full work permission in the U.S., or providing ECE services without full compliance with licensing or other requirements. The questionnaire, therefore, very intentionally avoids any reference to such issues as visa status or licensing status. We view it as essential in gaining cooperation and respondents’ trust to be able to assure them that no questions will be asked on these potentially sensitive topics.

12. Estimation of Information Collection Burden

Data collection is expected to take place over approximately nine months.

Exhibit 4. Estimated Number of Burden Hours to Complete the Data Collection

Questionnaire |

Total/Annual Number of Respondents |

Number of Responses per Respondent |

Average Burden Hours per Response |

Estimated Annual Burden Hours |

Average Hourly Wage Rate |

Total Cost Burden |

Household screener (screening only) |

61,500 |

1 |

.1 |

6,150 |

$18.12 |

$111,438 |

Household questionnaire (no screener) – during school year |

8,000 |

1 |

1 |

8,000 |

$18.12 |

$144,960 |

Household questionnaire (no screener) – during summer |

2,600 |

1 |

.75 |

1,950 |

$18.12 |

$35,334 |

Home-based provider screener ([screening only] listed home-based providers) |

2,015 |

1 |

.03 |

60 |

$10.72 |

$643 |

Home-based provider questionnaire, including screener (listed home-based providers) |

4,000 |

1 |

.67 |

2,680 |

$10.72 |

$28,730 |

Home-based provider questionnaire, including screener (unlisted home-based providers) |

2,100 |

1 |

.33 |

693 |

$10.72 |

$7,429 |

Center-based provider screener (screening only) |

7,640 |

1 |

.1 |

764 |

$22.54 |

$17,221 |

Center-based provider questionnaire, including screener |

7,800 |

1 |

.75 |

5,850 |

$22.54 |

$131,859 |

Classroom staff (workforce) questionnaire |

6,100 |

1 |

.33 |

2,013 |

$10.72 |

$21,579 |

Total |

|

|

|

28,160 |

|

$499,193 |

Average Hourly Wage Information

The above average hourly wage information includes estimates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The wage rate for the household survey is the median hourly wage for all occupations ($18.12).5 The median hourly wage for 11-9031 Education Administrators, Preschool and Child Care Center/Program is $22.54.6 The median hourly wage for home-based providers or child care workers is $10.72.7

13. Cost Burden to Respondents or Record Keepers

Honoraria will be provided directly to individual participants as compensation for their time participating in the survey. Honoraria are “payments given to professional individuals or institutions for services for which fees are not legally or traditionally required in order to secure their participation,” (Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs Office of Management and Budget, 2016).

Exhibit 5. Proposed Honoraria Models for 2019 NSECE

Sample |

Post-paid Honorarium Value** |

Estimated 2019 Questionnaire Completion Time (hours) |

Estimated 2019 Wages |

Center-based provider |

$20 |

0.8 |

Median: $21.20/hour** |

Listed home-based provider |

$15 |

0.67 |

$10.72/hour* |

Unlisted home-based provider |

$10 |

0.33 |

$10.72/hour* |

Classroom staff (workforce) |

$10 |

0.33 |

Median: $11.82/hour** |

* Home-based provider hourly wage rates from BLS data as in Exhibit 4.

** Median wage rates for center-based providers and classroom staff are based on 2012 NSECE response data. We calculated the respective median wage rates from the 2012 NSECE response data and applied an estimated inflation adjustment from January 2012 to January 2019 of 11.54%. For example, a $19 wage in 2012 for center-based provider respondents is used to project an hourly wage of $21.20 in 2019.

14. Estimate of Cost to the Federal Government

The total estimated cost of the 2019 NSECE data collection is $26.7 million. This cost includes survey management, data collection, and other tasks involved in implementing the data collection effort. The estimated amount for data collection in fiscal year 2018 is $1.5 million. In 2019 the estimated amount is $25.2 million. Because this is a one-time data collection, there will be no data collection costs after 2019.

15. Change in Burden

This request is for a new round of data collection for the NSECE. All previously approved data collection under 0970-0391 was completed.

16. Plans and Time Schedule for Data Collection and Deliverables

Data collection for the 2019 NSECE is slated to begin in November 2018, pending OMB approval. The proposed time schedule for data collection is listed in Exhibit 6 below:

Exhibit 6. Proposed Data Collection Time Schedule

Activity |

Date |

Prepare for data collection |

September 2018 |

Conduct data collection (pending OMB approval) |

November 2018–August 2019 |

Data collection begins for household sample (mailing advance letter, web survey invitation, and paper self-administered screener) |

November–December 2018 |

Screening of K-8 schools for center-based provider questionnaire |

|

Data collection for household, center-based, home-based, and classroom staff (workforce) surveys |

January–August 2019 |

In addition, the 2019 NSECE team will prepare comprehensive reports on the utilization and supply of ECE, specifically seven research briefs, four methodological briefs, and seven fact sheets that address the research questions mentioned above. The project team will also produce public- and restricted-use data files, with relevant documentation, which will be made available to other researchers to fully explore the range of issues of policy and programmatic importance. These data will have geographic and other identifiers to allow for linkage to other information (e.g., Census Bureau data, policy variables).

17. Reasons to Not Display OMB Expiration Date

Does not apply.

18. Exceptions to Certification for Paperwork Reduction Act Submissions

No exceptions are necessary for this information collection.

Reference List

Anthony, J., Muenchow, S., Arellanes, M., & Manship K. (2016). Unmet need for preschool services in California: Statewide and local analysis. Washington DC: American Institutes for Research. Available at: https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Unmet-Need-for-Preschool-Services-California-Analysis-March-2016.pdf

Bassok, D., Fitzpatrick, M., Greenberg, E.H., & Loeb, S. (2016). Within- and between-sector quality differences in early childhood education and care. Child Development, 87 (5), 1627-45. Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/570f/671c5c9f88e4d49af585006b6e421131c164.pdf?_ga=2.188555944.1462708497.1519329541-1613166450.1519329541

Blumberg, S.J. & Luke, J.V. Wireless substitution: Early release of estimates from the national health interview survey, July–December 2017. (2017). National Center for Health Statistics. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm

Caronongan, P., Kirby, G., Boller, K., Modlin, E., & Lyskawa, J. (2016). Assessing the implementation and cost of high quality early care and education: A review of literature. OPRE Report #2016-31, Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. Available at: https://www.mathematica-mpr.com/our-publications-and-findings/publications/assessing-the-implementation-and-cost-of-high-quality-early-care-and-education-a-review

Crosby, D. A., & Mendez, J. L. (2016). Hispanic children's participation in early care and education: Amount and timing of hours by household nativity status, race/ethnicity, and child age. (Publication No. 2016-58). Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Available at: https://www.researchconnections.org/childcare/resources/32877

Epstein, D., Halle, T., Moodie, S., Sosinsky, L., & Zaslow, M. (2016). Examining the association between infant/toddler workforce preparation, program quality and child outcomes: A review of the research evidence. OPRE Report #2016-15. Washington DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.earlychildhoodworkforce.org/sites/default/files/resources/cceepra_evidencereviewreportandtables_508compliantfinalupdated.pdf

Friese, S., Lin, V., Forry, N., & Tout, K. (2017). Defining and measuring Access to high quality early care and education: A guidebook for policymakers and researchers. OPRE Report #2017-08. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/cceepra_access_guidebook_final_508_22417_b508.pdf

Guzman, L., Hickman, S., Turner, K., & Gennetian, L. A. (2016). Hispanic children's participation in early care and education: Parents' perceptions of care arrangements, and relatives' availability to provide care. (Publication No. 2016-60). Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Available at: https://www.researchconnections.org/childcare/resources/32878

Howes, C., Pianta, R.C., Hamre, B.K. (Eds.), Effective early childhood professional development: improving teacher practice and child outcomes (pp. 113-130). Brookes Publishing.

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academies. (2015). Transforming the workforce for children birth through age 8. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. Available at: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2015/Birthto8/BirthtoEight_brief.pdf

Isaacs, J., Katz, M., Minton, S., & Michie, M. (2015). Review of child care needs of eligible families in Massachusetts. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. Available at: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/45351/2000160-review-of-child-care-needs.pdf

Limardo, C., Hill, S., Stadd, J., & Zimmer, T. (2016). Accessing career pathways to education and training for early childhood professionals. Bethesda, MD: Manhattan Strategy Group. Available at: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ecd/elcpi_accessibility_10_28_ada.pdf

Madill, R., Blasberg, A., Halle, T., Zaslow, M., & Epstein, D. (2016). Describing the preparation and ongoing professional development of the infant/toddler workforce: An analysis of the national survey for early care and education data. OPRE Report #2016-16, Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/cceepra_secondary_analysis_508final_b508.pdf

Madill, R., Halle, T., Gebhart, T., & Shuey, E. (2018). Supporting the psychological wellbeing of the early care and education workforce: Findings from the National Survey of Early Care and Education. OPRE Report #2018-49, Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/nsece_psychological_wellbeing_612018_to_opre_508_2.pdf

Maxwell, K. L., Sosinsky, L., Tout, K., & Hegseth, D. (2016). Coordinated monitoring systems for early care and education. OPRE Research Brief #2016-19. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/coordinated_monitoring_systems_in_early_care_and_education.pdf

Mercer, A., Caporaso, A., Cantor, D., & Townsend, R. (2015). How much gets you how much? Monetary incentives and response rates in household surveys, Public Opinion Quarterly, Volume 79, Issue 1, 1 January 2015, Pages 105–129. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfu059

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2006). Study of early child care and youth development (SECCYD): Findings for children up to Age 4 1/2 years (05-4318) Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

National Survey of Early Care and Education Team. (2013). Number and characteristics of early care and education (ECE) teachers and caregivers: initial findings from the national survey of early care and education (NSECE). OPRE Report #2013-38, Washington DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/resource/number-and-characteristics-of-early-care-and-education-ece-teachers-and