0648-0769 Supporting Statement Part A

0648-0769 Supporting Statement Part A.docx

Florida Fishing and Boating Survey

OMB: 0648-0769

SUPPORTING

STATEMENT

FLORIDA FISHING AND BOATING SURVEY

OMB CONTROL

NO. 0648-0769

The objective of the Florida Boating and Fishing Survey (FBFS) is to understand how anglers respond to changes in trip costs and fishing regulations in the Gulf of Mexico. We are conducting this survey to improve our ability to predict changes in the number of fishing trips anticipated with changes in economic conditions and fishing regulations. This will improve the analysis of the economic effects of proposed changes in fishing regulations and changes in economic factors that affect the cost of fishing such as fuel prices. The FBFS will, therefore, produce results that will help meet the goals outlined in the National Saltwater Recreational Fisheries Implementation Plan, especially the plan to bolster understanding of the social and economic importance of recreational fishing. The work also addresses needs identified in the 2018 National Saltwater Recreational Fisheries Summit Report (NOAA 2018), in particular the need for improvements in the ability to predict changes in species-specific saltwater recreational fishing effort expected when fishing or economic conditions change. Note that, while the survey is expected to provide useful information for different stakeholders interested in analyzing effects of changes in regulations, the research is not designed to examine a specific regulation.

The FBFS will collect recreational fishing and boating information directly from the boating and fishing community with a specific focus on saltwater anglers fishing for gag grouper in the Gulf of Mexico. We will combine actual and contingent behavior data collected through the surveys to estimate a trip demand model (e.g., Alberini et al. 2007 and Whitehead et al. 2012). The model will provide estimates of hypothetical changes in recreational fishing effort expected from changes in fishing costs and gag grouper regulations. The model will also generate estimates of the potential change in fishing and boating activity anticipated with changes in trip costs. The estimates can be used to develop predictive models the forecast how fishing and/or boating effort will change when the trip costs change (e.g., via fuel price changes) and when the gag grouper fishing regulations (season length or bag limits) change. The results can also be used to determine if fishers and boaters respond the same to changes in trip costs.

Explain how, by whom, how frequently, and for what purpose the information will be used. If the information collected will be disseminated to the public or used to support information that will be disseminated to the public, then explain how the collection complies with all applicable Information Quality Guidelines.

The information generated from survey data will be useful for Federal, state, and local management entities interested in the potential changes in effort with changes in fishing costs and regulations. These entities may use the information to examine the consequences of projects, policies, or regulations that may affect recreational fishing – favorably or adversely. The results of the survey will be published and also available to anyone requesting the information. The survey will collect information only on fishing or boating activity associated with the respondent effort over the previous 2 months, and very limited demographic information.

In addition, we will prepare a paper for peer-reviewed publication that describes the outcomes of this survey. Prior to dissemination, the information will be subjected to quality control measures and a pre-dissemination review pursuant to Section 515 of Public Law 106-554.

Describe whether, and to what extent, the collection of information involves the use of automated, electronic, mechanical, or other technological techniques or other forms of information technology.

The data will be collected via a voluntary survey that respondents will take online or on paper. Initial contacts will be made either by email or mail, but the main mode of data collection will be an online survey. The paper survey will only be sent to those not responding to the online survey. An electronic database system will be used to track respondents and those who need to receive the paper version of the survey. The online survey will be programmed to include prompts and skip patterns to match the skip patterns in the paper survey. (See Part B for description of the methodology).

We will work with the State of Florida to ensure that we do not sample the same addresses as those targeted by the Gulf Reef Fish Survey (GRFS) and to coordinate responses to any questions regarding the survey. We cannot use the GRFS as our sampling frame because it does not contain boaters without a license (e.g. seniors). The State of Florida starts with the saltwater license frame and then attaches an indicator as to whether or not the household has an “offshore” boat registered at the same address. This approach is “license-frame-based” as opposed to “boat-owner-frame-based”. The later approach can contact boat-based anglers with and without a license.

There are many studies related to the value of recreational fishing (see Johnston et al. 2006 for a review). The literature on saltwater recreational fishing in the Southeast US (South Atlantic or Gulf of Mexico) includes studies on reef fish species, typically red snapper, groupers as a general category, or coastal pelagics (king mackerel, dolphinfish). This body of research has focused on estimating angler WTP by species and/or quantities of fish caught per trip (Carter and Liese 2012; Gillig et al. 2003; Haab et al. 2012; Hindsley et al. 2011; Lovell and Carter 2014).

Very little research focuses on predicting changes in recreational fishing behavior in the Southeast US. Whitehead et al. (2011) investigate how anglers would change number of charter trips they take in North Carolina in response to hypothetical changes in the combined snapper-grouper bag limits, and bag limits for King Mackerel. While this work deals with bag limits for snapper-grouper species it is unlikely that the estimates are strictly applicable to gag grouper fishing in the Gulf of Mexico. Cross-study comparisons suggest that economic measures related to recreational fishing cannot be easily transferred from one study area or mode (charter, shore, private boat, etc.) of fishing to other contexts (Johnston et al. 2006).

Gillig et al. (2000) estimated changes in effort based on changes in estimated catch, but only focused on red snapper. The trip cost and catch elasticities were estimated from a survey of anglers from 1991 who fished at sites across the Gulf of Mexico. Gillig et al. (2003) extends their analysis on this same dataset to examine the impact of the revealed preference data on the overall willingness to pay using their combined stated-preference and revealed preference model. Given many changes in regulations and stock abundance during the intervening 27 years, there is a strong possibility that angler behavior and preferences with regard to red snapper and reef fish in general may have changed as well. Therefore, this work cannot reliably be used to predict current changes in fishing for gag grouper in the Gulf of Mexico.

Other related research examines the potential changes in Florida coastal recreational activity anticipated with changes in costs and quality (e.g. Bhat 2003 (marine reserves), Park et al. 2002 (snorkeling), Thomas and Stratis 2002 (boating), Milon 1988 (preferences of anglers for natural versus artificial reef habitats). A more recent study by Whitehead et al. estimated a single site travel cost model to estimate the effects of the lost recreational use values from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on all cancelled recreational trips to northwest Florida, including uses other than fishing.

In summary, our literature review did not find any research directly useful to the objective of our proposed research which is to estimate the magnitude of potential changes (elasticities) in private boat recreational fishing effort for gag groupers in Florida associated with changes in regulations (e.g. catch) or trip costs. Given over 80% of trips from West Florida for gag grouper are from private boat anglers, there is need for more current research that is tailored to this specific mode and that can estimate how changes in bag limits or trip costs influence the number of trips taken.

If the collection of information involves small businesses or other small entities, describe the methods used to minimize burden.

Not Applicable.

Describe the consequences to the Federal program or policy activities if the collection is not conducted or is conducted less frequently.

The data and models currently used to predict changes in recreational fishing effort anticipated with change in regulations are either not available or dated. Consequently, Federal or state agencies will not be able to accurately calculate the benefits and costs of proposed changes in fishery regulations with the information collected in this survey. Inaccurate estimates of changes in benefits and costs can lead to incorrect policy conclusions and mistaken selection of regulations that are economically inefficient. This could harm the sustainability of Federal or state fishery management programs.

Explain any special circumstances that require the collection to be conducted in a manner inconsistent with OMB guidelines.

The collection is consistent with OMB guidelines.

Provide a copy of the PRA Federal Register notice that solicited public comments on the information collection prior to this submission. Summarize the public comments received in response to that notice and describe the actions taken by the agency in response to those comments. Describe the efforts to consult with persons outside the agency to obtain their views on the availability of data, frequency of collection, the clarity of instructions and record keeping, disclosure, or reporting format (if any), and on the data elements to be recorded, disclosed, or reported.

A Federal Register Notice ‘Web Survey to Collect Economic Data from Anglers in the Gulf of Mexico’ was published on Friday September 14, 2017 (81 FR 3782), soliciting public comment. No substantive comments were received.

We have already been in contact with the State of Florida regarding the survey and sampling procedures. As noted above, we will work with the State of Florida to ensure that we do not sample the same addresses as those targeted by the Gulf Reef Fish Survey and to coordinate responses to any questions regarding the survey. We have also discussed the availability and composition of the boating license list with the State of Florida and a private contractor who provides Florida boat license database services.

Explain any decisions to provide payments or gifts to respondents, other than remuneration of contractors or grantees.

The benefits of prepaid cash incentives on improving survey response rates are well documented (Dillman et al. 2014). We intend to follow a mail web-push protocol with a prepaid incentive and mail follow-up to maximize the response rate within the budget (Dillman 2017). Millar and Dillman (2011) show that this approach can improve response rates for a web survey by nearly 20 percentage points over an approach with email only contacts and no incentive. The MRIP Effort Survey of anglers currently uses a $2 prepaid incentive in a mail survey because pretesting found that “response rates increased significantly with increasing incentive amounts, but the $1 and $2 treatments were the most efficient in terms of cost” (OMB Control No. 0648-0652) . Therefore, we are proposing a $2 prepaid incentive in the mail-push portion of the survey. However, we are also conducting a portion of the survey using only email contacts (without an incentive) so that we can compare the relative response rates of the two strategies and the relative quality of responses.

In the pilot study (see Part B, section 22) we obtained a 0.39 response rate with a $2 incentive in mail web-push protocol and a 0.15 response rate with email only contacts. This 0.23 point increase is consistent with the results in Millar and Dillman (2011).

Describe any assurance of confidentiality provided to respondents and the basis for assurance in statute, regulation, or agency policy.

No personally identifiable information will be collected through the survey. Responses will only be associated with a unique, randomly assigned identification code. Any public release of survey data will be without identification as to its source or in aggregate statistical form. All survey data will be stored on secured, password protected servers, and all transfer of survey data will utilize secure file transfer protocols.

Provide additional justification for any questions of a sensitive nature, such as sexual behavior and attitudes, religious beliefs, and other matters that are commonly considered private.

There are no questions of a sensitive nature.

The main survey will be completed by approximately 1,250 people, resulting an estimated burden of 104 hours (1,250 * 5 minutes / 60 minutes). The nonresponse survey will be completed by approximately 175 people, for an estimated burden of 15 hours (175 * 5 minutes / 60 minutes). Based on the average hourly labor rate of $24 per hour for all civilian workers from the National Compensation Survey, the resulting total cost for the main and nonresponse survey will be approximately $2,891. There are no other costs to respondents.

Provide an estimate of the total annual cost burden to the respondents or recordkeepers resulting from the collection (excluding the value of the burden hours in Question 12 above).

These data collections will incur no cost burden on respondents beyond the costs of response time. Envelopes with prepaid postage will be included in the follow-up questionnaire mailing.

The duration of the survey will be for approximately 2 months; thus, the annualized cost is the one-time cost of the survey. Annual cost to the Federal government is approximately $40,000: $30,000 in data collection costs and $10,000 in professional staff, overhead and computing costs.

This is a modification/expansion of a data collection based on the results a pilot study (see Part B, section 22). The pilot study found a higher than expected prevalence rate for the target population in the sample frame. Consequently, we are requiring less sample for the larger study than originally planned (See Part B, section 19).

All results will be entered in a database using standard quality assurance/quality control procedures in survey research. Economists from NOAA Fisheries will analyze the data using standard software (e.g. R or SAS) and standard statistical procedures that are appropriate for survey data. Results from this collection may be used in scientific, management, technical or general informational publications, and would follow prescribed statistical tabulations and summary table formats. Data will be available to the general public on request in summary form only.

If seeking approval to not display the expiration date for OMB approval of the information collection, explain the reasons why display would be inappropriate.

Not Applicable.

Not Applicable.

Describe (including a numerical estimate) the potential respondent universe and any sampling or other respondent selection method to be used. Data on the number of entities (e.g., establishments, State and local governmental units, households, or persons) in the universe and the corresponding sample are to be provided in tabular form. The tabulation must also include expected response rates for the collection as a whole. If the collection has been conducted before, provide the actual response rate achieved.

Construction of Sample Frame

The target population for the FBFS is any Florida resident who might potentially fish in the Gulf of Mexico (GOM) from West Florida (WFL) during November and December. We are especially interested in anglers fishing for gag grouper. There is no specific list for this type of angler. We propose to construct a sample frame from two lists of Florida residents. The first is the list of registered Florida boat owners (FBO) and the second is the list of licensed saltwater anglers in Florida (FLSA). The FBO list will help us reach anglers missing from the saltwater license list due to exemptions, especially adults 65 and over which make up nearly 20% of the Florida population and by some accounts around 15% of the angling population (USFWS and USCB 2014). According to Info-Link, approximately 23% of our target FBO population is aged 65 or older.

The FBO and FLSA lists have information that can be used to focus on addresses that are most relevant to WFL GOM fishing during November and December. Both lists can be narrowed geographically to counties where WFL GOM trips are most likely to originate. We then propose to oversample these counties based on gag grouper fishing prevalence to generate sufficient responses from gag grouper anglers.

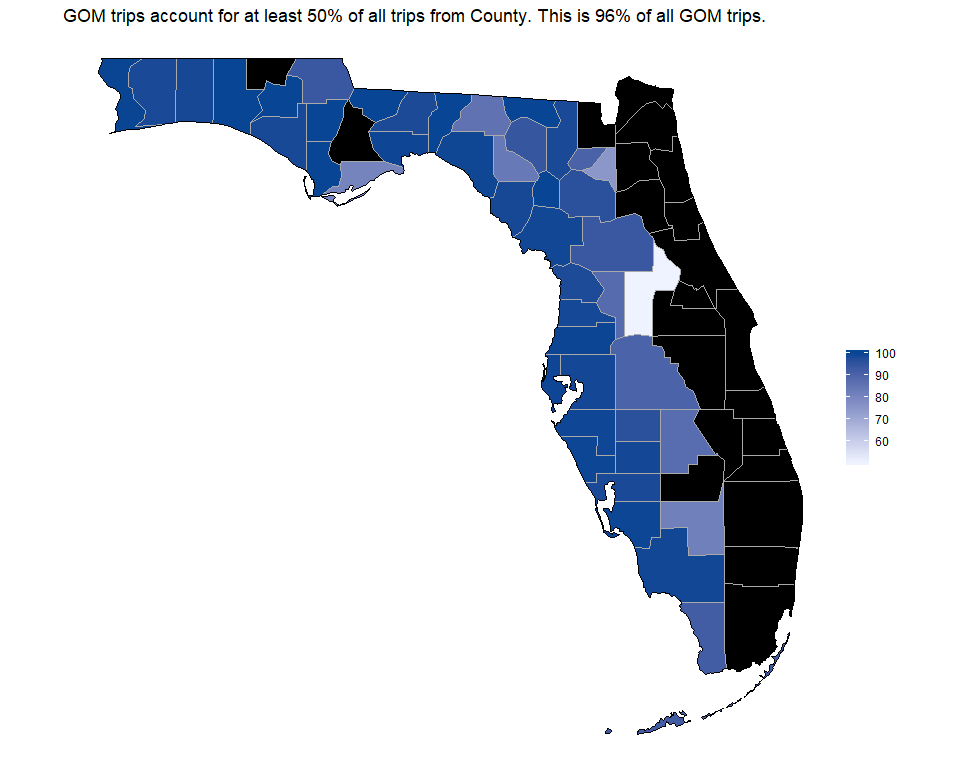

We use data from the Marine Recreational Fishing Information Program (MRIP) to identify Florida counties that are most likely to be associated with WFL GOM private boat fishing. In this case, a county is “associated” with WFL GOM if at least 50% of the 2005 to 2017 average annual estimated fishing trips during November and December from the county were to the GOM from WFL. Note that this sample frame will not cover the entire population of anglers that fish in the GOM from WFL because, based on 18 years of MRIP data, approximately 14% of anglers fishing in the GOM from WFL from a private boat reside outside Florida. We also define trips during this period as “associated”" with gag grouper if the angler either targeted (primary or secondary) or caught (kept or released dead or alive) gag grouper in the GOM from WFL.

Table 1 shows the average annual number of trips originating from each Florida county from 2005 to 2017 during November and December. There are columns for the estimated count of all trips (ALL), trips to the Gulf of Mexico (GOM), and trips to the Gulf of Mexico that targeted or caught gag grouper (GAG). A 95% confidence interval (LB and UB) is also shown next to each trip count estimate. The table is sorted in descending order by the number of trips to the Gulf of Mexico.

Table 2 shows the trip information again along with the county population (POP) and count of registered pleasure vessels, both all boats (ALL) and boats between 16 feet and 110 feet (CLASS14). Note that all trip estimates with a lower bound less than zero in Table 1 have been set to zero in Table 2 to remove counties with imprecise estimates from further consideration. The subset of pleasure boats between 16 feet and 110 feet likely contains nonfishing vessels. The FBO database has information that can be used to limit this population of registered boaters to those who are most likely to fish offshore. Specifically, we are interested in open or cabin motorboats >= 20 feet with outboard, inboard, or inboard/outboard motors and fiberglass hulls that are defined as recreational (pleasure) craft. Based on data from Info-Link’s BoatOwners Database, approximately 27% of registered pleasure vessels between 16 feet and 110 feet meet this criteria. The BoatOwners Database can also be used to delineate between “sportfish” brand and “other” brand vessels. However, we will likely include both brand types in the sample frame.

Table 2 also shows the share of trips originating from each county that went to the GOM and the share that went to the GOM to fish for (targeting or catching) gag grouper. The table is sorted in descending order by the share that went to the GOM. We plan to sample from the counties with at least 50% of trips to the GOM: Calhoun to Lake. These 45 counties account for 96% of all GOM trips and 99% of all gag grouper trips in the GOM. The map in Figure 1 shows the percentage of trips to the GOM from counties that will be sampled for the survey. Overall, 13% of trips in these counties are associated gag grouper. This suggests that every 8th angler from these counties is associated with gag grouper. Consequently, we would need around 8 times as much sample to reach gag grouper anglers, even from these counties. The pilot study (see Part B, section 22) found, however, that every 3th angler. If we use these results, then we would only need around around 3 times as much sample to reach gag grouper anglers. The pilot study included one county with a relatively high number of trips associated with gag grouper and another county with a relatively low number of trips associated with gag grouper. Therefore, we think that the gag grouper trip prevalence rate of 32% from the pilot study is an appropriate estimate for gag grouper trip prevalence for the rest of the coastal counties.

Table 1: Average Annual Private Boat Trips to GOM from WFL from Florida Counties Counties: 2005-2017, Nov-Dec (descending by GOM trips)

COUNTY |

ALL |

ALL LB |

ALL UB |

GOM |

GOM LB |

GOM UB |

GAG |

GAG LB |

GAG UB |

PINELLAS |

439,044 |

381,708 |

496,381 |

437,337 |

380,009 |

494,665 |

93,907 |

74,556 |

113,258 |

HILLSBOROUGH |

424,476 |

378,347 |

470,606 |

420,836 |

374,744 |

466,927 |

46,974 |

37,287 |

56,661 |

LEE |

195,639 |

162,588 |

228,690 |

195,047 |

161,999 |

228,095 |

15,742 |

10,269 |

21,214 |

SARASOTA |

194,338 |

157,009 |

231,667 |

193,878 |

156,551 |

231,205 |

35,463 |

24,515 |

46,412 |

PASCO |

161,959 |

135,832 |

188,086 |

161,703 |

135,578 |

187,827 |

25,509 |

18,669 |

32,350 |

MANATEE |

136,900 |

103,267 |

170,532 |

136,286 |

102,659 |

169,912 |

26,307 |

17,335 |

35,279 |

COLLIER |

133,132 |

99,911 |

166,353 |

132,296 |

99,084 |

165,507 |

10,370 |

5,288 |

15,453 |

CITRUS |

121,045 |

92,059 |

150,030 |

118,751 |

89,798 |

147,704 |

14,298 |

8,439 |

20,158 |

CHARLOTTE |

81,399 |

62,701 |

100,098 |

80,219 |

61,549 |

98,888 |

6,675 |

3,899 |

9,451 |

HERNANDO |

79,901 |

61,248 |

98,554 |

79,149 |

60,532 |

97,765 |

17,417 |

11,648 |

23,187 |

ALACHUA |

81,705 |

61,669 |

101,741 |

78,535 |

58,594 |

98,476 |

7,235 |

2,376 |

12,093 |

POLK |

82,263 |

70,383 |

94,143 |

74,282 |

62,833 |

85,730 |

9,523 |

6,702 |

12,344 |

ESCAMBIA |

73,890 |

52,993 |

94,787 |

73,811 |

52,914 |

94,707 |

8,102 |

3,897 |

12,307 |

LEON |

63,720 |

46,710 |

80,730 |

62,690 |

45,698 |

79,681 |

16,659 |

10,014 |

23,304 |

MONROE |

65,012 |

45,873 |

84,152 |

59,981 |

41,058 |

78,905 |

642 |

-181 |

1,465 |

MARION |

60,656 |

39,927 |

81,384 |

56,880 |

36,321 |

77,440 |

8,586 |

2,543 |

14,629 |

BAY |

56,164 |

34,329 |

77,999 |

55,462 |

33,643 |

77,281 |

6,020 |

-134 |

12,173 |

SANTA ROSA |

49,524 |

31,908 |

67,140 |

48,799 |

31,208 |

66,389 |

5,426 |

1,229 |

9,622 |

MIAMI-DADE |

239,913 |

191,806 |

288,020 |

44,771 |

23,728 |

65,815 |

945 |

8 |

1,882 |

OKALOOSA |

41,318 |

23,569 |

59,067 |

40,865 |

23,122 |

58,607 |

2,461 |

536 |

4,386 |

LEVY |

40,822 |

28,191 |

53,453 |

40,566 |

27,938 |

53,194 |

861 |

149 |

1,573 |

WAKULLA |

28,864 |

14,806 |

42,923 |

28,762 |

14,705 |

42,819 |

9,774 |

3,792 |

15,757 |

BROWARD |

167,833 |

128,690 |

206,975 |

25,317 |

15,563 |

35,072 |

797 |

34 |

1,560 |

LAKE |

38,908 |

27,730 |

50,086 |

19,556 |

12,898 |

26,214 |

3,533 |

1,179 |

5,887 |

GULF |

16,099 |

5,203 |

26,995 |

16,099 |

5,203 |

26,995 |

242 |

-147 |

630 |

ORANGE |

131,470 |

110,556 |

152,384 |

16,055 |

10,947 |

21,163 |

2,971 |

1,175 |

4,767 |

WALTON |

14,992 |

7,244 |

22,740 |

14,992 |

7,244 |

22,740 |

836 |

-51 |

1,722 |

COLUMBIA |

13,614 |

6,995 |

20,232 |

13,415 |

6,801 |

20,028 |

173 |

-166 |

512 |

FRANKLIN |

15,718 |

10,120 |

21,316 |

12,649 |

7,483 |

17,816 |

2,861 |

492 |

5,230 |

SUMTER |

14,349 |

9,886 |

18,811 |

12,627 |

8,352 |

16,901 |

1,227 |

318 |

2,137 |

DIXIE |

9,433 |

4,506 |

14,361 |

9,336 |

4,411 |

14,261 |

199 |

-77 |

474 |

SUWANNEE |

9,412 |

5,527 |

13,297 |

8,895 |

5,051 |

12,739 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

GILCHRIST |

8,884 |

3,608 |

14,160 |

8,884 |

3,608 |

14,160 |

376 |

-145 |

896 |

TAYLOR |

7,818 |

3,298 |

12,339 |

7,779 |

3,260 |

12,299 |

489 |

-69 |

1,048 |

HIGHLANDS |

8,646 |

3,798 |

13,494 |

7,559 |

2,789 |

12,329 |

1,821 |

-163 |

3,806 |

PALM BEACH |

253,141 |

218,424 |

287,858 |

7,435 |

1,995 |

12,874 |

88 |

-84 |

260 |

HENDRY |

8,889 |

2,428 |

15,350 |

7,269 |

1,007 |

13,531 |

80 |

-61 |

221 |

OSCEOLA |

19,085 |

11,097 |

27,072 |

6,051 |

-954 |

13,056 |

79 |

-76 |

234 |

DESOTO |

6,079 |

3,099 |

9,058 |

6,027 |

3,049 |

9,004 |

139 |

-134 |

412 |

DUVAL |

362,167 |

304,908 |

419,426 |

5,873 |

3,757 |

7,990 |

317 |

-129 |

763 |

SEMINOLE |

104,257 |

84,174 |

124,340 |

5,732 |

2,380 |

9,084 |

1,226 |

-59 |

2,511 |

BRADFORD |

7,269 |

3,870 |

10,669 |

5,460 |

2,328 |

8,593 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

BREVARD |

289,487 |

245,729 |

333,245 |

5,223 |

1,949 |

8,497 |

84 |

-80 |

247 |

HOLMES |

3,594 |

-1,028 |

8,217 |

3,594 |

-1,028 |

8,217 |

536 |

-515 |

1,588 |

VOLUSIA |

279,888 |

231,882 |

327,893 |

3,556 |

2,026 |

5,086 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

JACKSON |

3,768 |

1,302 |

6,233 |

3,540 |

1,098 |

5,982 |

195 |

-77 |

466 |

GADSDEN |

3,484 |

1,490 |

5,479 |

3,484 |

1,490 |

5,479 |

1,968 |

217 |

3,719 |

UNION |

3,833 |

855 |

6,811 |

3,477 |

539 |

6,416 |

376 |

-148 |

900 |

PUTNAM |

12,877 |

7,847 |

17,906 |

3,468 |

1,152 |

5,784 |

253 |

-242 |

747 |

WASHINGTON |

3,092 |

950 |

5,233 |

3,092 |

950 |

5,233 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

MARTIN |

117,113 |

94,218 |

140,007 |

3,027 |

1,135 |

4,919 |

141 |

-136 |

418 |

CALHOUN |

2,962 |

240 |

5,684 |

2,962 |

240 |

5,684 |

281 |

-114 |

675 |

HARDEE |

2,790 |

1,147 |

4,433 |

2,686 |

1,050 |

4,323 |

319 |

-52 |

689 |

JEFFERSON |

2,495 |

1,081 |

3,908 |

2,495 |

1,081 |

3,908 |

271 |

-14 |

556 |

BAKER |

8,898 |

4,115 |

13,682 |

2,367 |

370 |

4,364 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

CLAY |

43,201 |

32,709 |

53,693 |

2,245 |

982 |

3,507 |

498 |

-192 |

1,188 |

ST. JOHNS |

116,707 |

89,295 |

144,119 |

1,759 |

628 |

2,889 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

HAMILTON |

1,535 |

51 |

3,018 |

1,535 |

51 |

3,018 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

NASSAU |

43,470 |

29,883 |

57,056 |

1,518 |

-621 |

3,658 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

ST. LUCIE |

126,248 |

103,221 |

149,275 |

1,306 |

141 |

2,471 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

LAFAYETTE |

1,067 |

338 |

1,797 |

894 |

249 |

1,540 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

MADISON |

839 |

128 |

1,551 |

720 |

34 |

1,405 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

INDIAN RIVER |

101,234 |

77,314 |

125,155 |

671 |

72 |

1,270 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

FLAGLER |

22,633 |

11,843 |

33,423 |

357 |

-52 |

767 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

GLADES |

499 |

-77 |

1,075 |

280 |

-159 |

718 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

OKEECHOBEE |

6,881 |

3,847 |

9,915 |

200 |

-32 |

433 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

LIBERTY |

184 |

-176 |

543 |

184 |

-176 |

543 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 2: Population (2010), Registered Boats (2016) and Average Annual (2005-2017) Trips during Nov-Dec for Counties (descending by GOM trip share)

COUNTY |

POP |

CLASS14 BOATS |

ALL BOATS |

ALL TRIPS |

GOM TRIPS |

GAG TRIPS |

GOM TRIPS SHARE |

GAG TRIPS SHARE |

SHARE OF GOM TRIPS |

SHARE OF GAG TRIPS |

CALHOUN |

14,625 |

531 |

1,580 |

2,962 |

2,962 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

GADSDEN |

46,389 |

1,125 |

2,238 |

3,484 |

3,484 |

1,968 |

1 |

0.56 |

0 |

0.01 |

GILCHRIST |

16,939 |

983 |

1,671 |

8,884 |

8,884 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

GULF |

15,863 |

1,408 |

2,769 |

16,099 |

16,099 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0.01 |

0 |

HAMILTON |

14,799 |

399 |

871 |

1,535 |

1,535 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

JEFFERSON |

14,761 |

583 |

1,234 |

2,495 |

2,495 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

WALTON |

55,043 |

2,828 |

5,494 |

14,992 |

14,992 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0.01 |

0 |

WASHINGTON |

24,896 |

915 |

2,362 |

3,092 |

3,092 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

ESCAMBIA |

297,619 |

9,252 |

15,033 |

73,890 |

73,811 |

8,102 |

1 |

0.11 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

PASCO |

464,697 |

14,160 |

23,148 |

161,959 |

161,703 |

25,509 |

1 |

0.16 |

0.06 |

0.07 |

SARASOTA |

379,448 |

15,068 |

21,401 |

194,338 |

193,878 |

35,463 |

1 |

0.18 |

0.07 |

0.09 |

LEE |

618,754 |

33,264 |

45,187 |

195,639 |

195,047 |

15,742 |

1 |

0.08 |

0.07 |

0.04 |

WAKULLA |

30,776 |

2,716 |

4,734 |

28,864 |

28,762 |

9,774 |

1 |

0.34 |

0.01 |

0.03 |

PINELLAS |

916,542 |

31,053 |

47,130 |

439,044 |

437,337 |

93,907 |

1 |

0.21 |

0.15 |

0.25 |

MANATEE |

322,833 |

11,532 |

17,407 |

136,900 |

136,286 |

26,307 |

1 |

0.19 |

0.05 |

0.07 |

TAYLOR |

22,570 |

2,007 |

3,565 |

7,818 |

7,779 |

0 |

0.99 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

LEVY |

40,801 |

2,416 |

3,989 |

40,822 |

40,566 |

861 |

0.99 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0 |

COLLIER |

321,520 |

15,119 |

21,539 |

133,132 |

132,296 |

10,370 |

0.99 |

0.08 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

DESOTO |

34,862 |

1,209 |

2,227 |

6,079 |

6,027 |

0 |

0.99 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

HILLSBOROUGH |

1,229,226 |

25,196 |

39,191 |

424,476 |

420,836 |

46,974 |

0.99 |

0.11 |

0.15 |

0.13 |

HERNANDO |

172,778 |

5,345 |

9,154 |

79,901 |

79,149 |

17,417 |

0.99 |

0.22 |

0.03 |

0.05 |

DIXIE |

16,422 |

1,364 |

2,246 |

9,433 |

9,336 |

0 |

0.99 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

OKALOOSA |

180,822 |

10,525 |

17,829 |

41,318 |

40,865 |

2,461 |

0.99 |

0.06 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

BAY |

168,852 |

9,572 |

17,118 |

56,164 |

55,462 |

0 |

0.99 |

0 |

0.02 |

0 |

CHARLOTTE |

159,978 |

15,767 |

21,402 |

81,399 |

80,219 |

6,675 |

0.99 |

0.08 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

COLUMBIA |

67,531 |

2,483 |

4,360 |

13,614 |

13,415 |

0 |

0.99 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

SANTA ROSA |

151,372 |

7,968 |

14,089 |

49,524 |

48,799 |

5,426 |

0.99 |

0.11 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

LEON |

275,487 |

6,753 |

12,540 |

63,720 |

62,690 |

16,659 |

0.98 |

0.26 |

0.02 |

0.04 |

CITRUS |

141,236 |

10,087 |

15,578 |

121,045 |

118,751 |

14,298 |

0.98 |

0.12 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

HARDEE |

27,731 |

840 |

1,588 |

2,790 |

2,686 |

0 |

0.96 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

ALACHUA |

247,336 |

6,151 |

9,979 |

81,705 |

78,535 |

7,235 |

0.96 |

0.09 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

SUWANNEE |

41,551 |

1,459 |

2,700 |

9,412 |

8,895 |

0 |

0.95 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

JACKSON |

49,746 |

2,024 |

4,665 |

3,768 |

3,540 |

0 |

0.94 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

MARION |

331,298 |

11,030 |

18,254 |

60,656 |

56,880 |

8,586 |

0.94 |

0.14 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

MONROE |

73,090 |

19,810 |

26,147 |

65,012 |

59,981 |

0 |

0.92 |

0 |

0.02 |

0 |

UNION |

15,535 |

513 |

974 |

3,833 |

3,477 |

0 |

0.91 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

POLK |

602,095 |

16,388 |

27,733 |

82,263 |

74,282 |

9,523 |

0.9 |

0.12 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

SUMTER |

93,420 |

2,437 |

4,338 |

14,349 |

12,627 |

1,227 |

0.88 |

0.09 |

0 |

0 |

HIGHLANDS |

98,786 |

5,297 |

8,807 |

8,646 |

7,559 |

0 |

0.87 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

MADISON |

19,224 |

596 |

1,158 |

839 |

720 |

0 |

0.86 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

LAFAYETTE |

8,870 |

472 |

897 |

1,067 |

894 |

0 |

0.84 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

HENDRY |

39,140 |

1,794 |

2,827 |

8,889 |

7,269 |

0 |

0.82 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

FRANKLIN |

11,549 |

1,463 |

2,360 |

15,718 |

12,649 |

2,861 |

0.8 |

0.18 |

0 |

0.01 |

BRADFORD |

28,520 |

1,299 |

2,275 |

7,269 |

5,460 |

0 |

0.75 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

LAKE |

297,052 |

13,631 |

20,581 |

38,908 |

19,556 |

3,533 |

0.5 |

0.09 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

PUTNAM |

74,364 |

4,552 |

7,260 |

12,877 |

3,468 |

0 |

0.27 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

BAKER |

27,115 |

1,285 |

2,437 |

8,898 |

2,367 |

0 |

0.27 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

MIAMI-DADE |

2,496,435 |

42,760 |

63,312 |

239,913 |

44,771 |

945 |

0.19 |

0 |

0.02 |

0 |

BROWARD |

1,748,066 |

28,310 |

42,486 |

167,833 |

25,317 |

797 |

0.15 |

0 |

0.01 |

0 |

ORANGE |

1,145,956 |

15,094 |

26,046 |

131,470 |

16,055 |

2,971 |

0.12 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

SEMINOLE |

422,718 |

10,303 |

17,623 |

104,257 |

5,732 |

0 |

0.05 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

CLAY |

190,865 |

7,697 |

12,275 |

43,201 |

2,245 |

0 |

0.05 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

PALM BEACH |

1,320,134 |

24,915 |

36,253 |

253,141 |

7,435 |

0 |

0.03 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

MARTIN |

146,318 |

12,513 |

16,675 |

117,113 |

3,027 |

0 |

0.03 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

BREVARD |

543,376 |

19,331 |

32,003 |

289,487 |

5,223 |

0 |

0.02 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

DUVAL |

864,263 |

15,682 |

25,719 |

362,167 |

5,873 |

0 |

0.02 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

ST. JOHNS |

190,039 |

8,748 |

13,842 |

116,707 |

1,759 |

0 |

0.02 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

VOLUSIA |

494,593 |

16,201 |

26,161 |

279,888 |

3,556 |

0 |

0.01 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

ST. LUCIE |

277,789 |

8,398 |

12,259 |

126,248 |

1,306 |

0 |

0.01 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

INDIAN RIVER |

138,028 |

6,606 |

10,190 |

101,234 |

671 |

0 |

0.01 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

FLAGLER |

95,696 |

3,240 |

5,339 |

22,633 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

GLADES |

12,884 |

795 |

1,213 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

HOLMES |

19,927 |

664 |

2,031 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

LIBERTY |

8,365 |

357 |

1,071 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

NASSAU |

73,314 |

3,420 |

6,044 |

43,470 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

OKEECHOBEE |

39,996 |

3,399 |

4,795 |

6,881 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

OSCEOLA |

268,685 |

4,488 |

7,838 |

19,085 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Figure 1: Percent of West Florida Gag Grouper Trips in each County of Origin during Nov-Dec, 2005-2017

Describe the procedures for the collection, including: the statistical methodology for stratification and sample selection; the estimation procedure; the degree of accuracy needed for the purpose described in the justification; any unusual problems requiring specialized sampling procedures; and any use of periodic (less frequent than annual) data collection cycles to reduce burden.

Target Completes and Sample Size

The goal for the FBFS study is to have at least 400 surveys completed by anglers with gag grouper experience, though there are also questions on the survey related to general boating and fishing activity. We must contact a sufficient number of addresses to meet this goal given the relatively small population of gag grouper anglers and the expected response rate. As described above, we can expect, roughly, that every 3rd angler has experience with gag grouper.

Based on the number of gag grouper angler responses and the estimated gag grouper prevalence, we propose a target complete size of 400/0.32=1,250 to be achieved via email and mail contacts. The actual number of addresses required from the FBO list depends initially on the prevalence of email addresses in the combined FBO-license lists, and the email and mail response rates. Previous experience suggests that email addresses can be obtained for around 20% of observations in the FBO list and about half of the observations in the saltwater license list. For the combined (matched and unmatched sample), we assume 40% of observations will have email addresses. Therefore, of the 1,250 completes, 500 will have email addresses and 750 will not.

We assume that the FBFS will achieve two different response rates depending on mode: 0.15 for email contact with 3 reminder emails and no incentive, and 0.38 using a web-push strategy, a $2 incentive, and a mail option for those not completing the web version of the survey (Messer and Dillman 2011). The email response rate is based on the pilot study (see Part B, section 22) and rates typically achieved with email contacts from fishing license frames in the Southeastern US (e.g., Wallen et al. 2016). The pilot study and recent experience using mail surveys to push respondents to web surveys suggests that mail, web-push response rates of around 30 to 40 percent are not unreasonable for a carefully designed survey, especially with a mail follow-up option (Dillman 2017). Though not strictly comparable, MRIP FES mail protocol also typically achieves response rates around 30 to 40 percent.

Based on the assumed relative response rates and

email prevalence, we propose initial target sample sizes of 0.4 *

1,250 / 0.15 = 3,333 for email contacts and (1-0.4)*1,250/0.38=1,974

for mail contacts. The combined email and mail target sample size is

5,307. However, we need to start with a larger sample from the FBO

list to account for the difference between the actual and required

rate of matching for the FBO list and the saltwater license list.

The

general sampling strategy will be to draw a random sample from the

FBO “offshore” boat subset with addresses in the WFL GOM

counties (Table 2) and then match as many addresses as possible to

the fishing license frame from the WFL GOM counties. We assume that a

match will be found for 55% of addresses from the FBO list. This rate

is much higher than the matching typically achieved by the MRIP FES,

but we are using the FBO list rather than the general mail address

list.

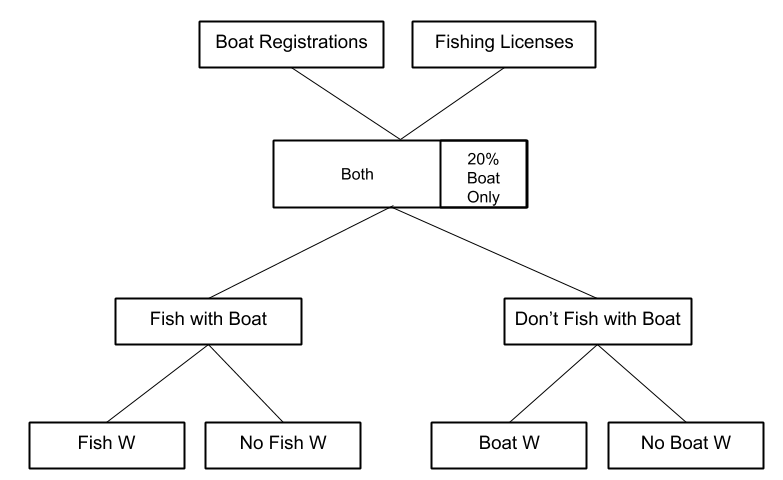

Following Brick et al. (2016) we will then sample the addresses from the FBO that do not match the license list until we hit the target sample size. Assuming that we want to have 20% (instead of 45%) of the final mailing sample to be unmatched to cover anglers 65 and over, the FBO “offshore” boat sample will have to be 7,719 addresses (5,307 * (1-0.2) / 0.55). This sample will then be matched to the license list to achieve the target sample size of 5,307 that contains 80% matched records. Any member of this list with an email will proceed with the email contact protocol and all others will proceed with the mail web-push protocol. As noted above, we are estimating that 3,333 members of the list will have emails and 1,974 members will not. The assumed sample allocation is shown in Table 3. Note that we show the population not included in the sample as a reminder that the sample does not cover the complete population of FBO or license lists. This number is based on the total number of 16 to 110 foot pleasure craft registrations in Florida during 2016 (565,590), but should be close to current figures. Also, the population numbers shown in the table are “guesses” obtained by applying the assumed actual FBO-license match rate (0.55) and the assumed share of records with email addresses (0.4) to the (565,590) count. The general sampling strategy is summarized in Figure 2.

Table 3: Assumed Sample Allocation based on 16 to 110 Foot Florida Vessel Registrations in 2016

Selected Boats |

Match |

Population |

Sample |

Returns |

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

19,633 |

2,667 |

400 |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

29,449 |

1,579 |

600 |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

16,063 |

667 |

100 |

Yes |

No |

No |

24,095 |

395 |

150 |

No |

Any |

Any |

476,351 |

0 |

NA |

Figure 2: Overview of Sampling Strategy

Specifically, we will create or purchase, from a qualified FBO list vendor, a sample of 7,719 addresses of registered boat owners in the Florida WFL GOM counties that meet the following criteria:

Only Florida residents

Type - open motorboat, cabin motorboat

Propulsion - outboard, inboard, inboard/outboard

Use - recreational (pleasure)

Length - >= 20 feet.

We will then match, by exact address and/or telephone number, the FBO sample to the list of anglers in the WFL GOM counties who were licensed to participate in saltwater fishing in Florida between the beginning of November 2019 and the time the list is compiled. The list will include a unique address ID, telephone number, state, county, address (address lines 1 and 2) and zip code of residence. The frame matching SAS program developed for the MRIP FES is available upon request. After the matching has been completed, we will sub-sample within the unmatched addresses at a rate needed to achieve target sample sizes as described above. Note that, as mentioned above, we will coordinate with the State of Florida to ensure that we do not sample the same people who have been selected to receive the Gulf Reef Fish Survey for the same period.

Survey Administration

The FES is a mail survey, but the FBFS will be a mixed-mode web-focused survey. We will closely follow the recommendations for mail-push web surveys in Messer and Dillman (2011) and Dillman (2017), including a prenotice letter, an incentive with the URL letter, and 2 mail follow-ups with the final a paper copy of the survey included in the final mailing.

The prenotice letter (first contact) will be sent during the last week of December 2019. The second contact will made within the first week of January with a letter containing a URL address for a web survey, a unique code that identifies each respondent (address), and a $2 incentive (one two dollar bill). Research suggests that the incentive significantly increases response rates in the mail web-push strategy (Messer and Dillman 2011). The respondent will be instructed to go to the URL, enter their unique code and complete the survey. The survey will focus on recreational fishing activity, but will contain screening questions related to saltwater recreation activities. There is more about the survey below. Following Messer and Dillman (2011) we are expecting about 60% of final returns (750*0.6 = 450) to occur after the first mailing (second contact).

Following the Messer and Dillman (2011), a thank you/reminder postcard (third contact) will be sent within 2 weeks after the first letter was mailed. The reminder postcard will also have the URL and the unique code. Contacts still not responding within 3 weeks of the reminder postcard will be sent (forth contact) a paper copy of the survey and a business reply envelope along with a letter including the URL and unique code. Note that NOAA will be handling the web survey and will to send the contractor a list of unique codes that completed the survey on the web. These addresses will be removed from the final mailing.

As described in more detail below, a nonresponse survey will be mailed to a sample of those in the email-only and mail-push groups who did not respond to the survey. This survey will be sent about 2 weeks after the final mailing to the mail-push group. It may be possible to mail the nonresponse survey to the email-only group slightly earlier which could help with recall.

The contractor will be responsible for all aspects of survey administration, except the web survey. This includes printing, assembling, mailing, receipting, and processing all survey materials. The contractor will handle all mailings and the tracking of respondents as expressed in Table 4. All mailings will be delivered through regular, first-class mail. Letters will be printed letterhead quality stock with a color NOAA logo. Frequently asked questions will be printed on the reverse side of the letter. Paper questionnaires will be mailed in a large envelope that can accommodate a 8.5X11 letter without folding. Each questionnaire will be printed on a single 8.5X11 sheet of paper, front and back.

Table 4: Sampling and Mailing Schedule

ITEM |

DATE |

ADDRESSES |

Obtain the FBO list and the license list for the select Florida counties in Table 1 and draw a sample of matched and unmatched addresses. |

12/09/19 |

7,719 |

Prenotice letter |

12/20/19 |

1,974 |

Letter with $2 incentive, URL, and unique respondent id code |

1/3/20 |

1,974 |

Reminder/Thank you postcard with URL, and unique respondent id code |

1/17/20 |

1,974 |

Letter with 2 page paper survey, URL, and unique respondent id code. |

1/31/20 |

1,524 |

Nonresponse survey sent to a portion of email only sample who did not respond. |

2/14/20 |

877 |

Survey Instrument

NOAA has programmed a version of the web survey in Qualtrics. The printed version is four pages to be printed as a double-sided booklet in color when sent with the final mailing.

There are two main sections of the survey following an introduction and screening/eligibility question. For the respondents that use their boat for fishing, the first section asks a series of questions related to fishing activity. There is also a subset of the fishing questions that will be answered by those who fish for gag grouper.

Those who do not use their boat for fishing are routed to a third section that asks a series of questions related to boating activities. Note that each respondent will answer either the fishing questions or the boating questions, but not both types of questions.

The fishing and boating question sections each have questions about the number of trips taken in the previous 2 months and the number of trips that would have been taken with different trip costs. The fishing section also has questions about the number of trips that would have been taken with different gag grouper regulations for anglers who fish for this species.

Q1: Intro text

Q2: ID Code they received in invitation by mail or email

Q3: Screening question to determine if the respondent is eligible to complete the survey - i.e. do they own and use a boat (If no, end of survey).

Q4: Screening question to determine if the respondent used their boat in the Gulf of Mexico in the two-month period.

Q5: if they did not use their boat during the two-month period in Gulf of Mexico, question asks for the reason they did not use it, then ends the survey.

Fishing Questions

Q6: Screening question to determine if the respondent is eligible to complete the portion of survey related to fishing in the Gulf of Mexico during two-month period by asking if they used the boat to fish during the two-month period.

Q7: If not used for fishing, then asks why they did not use the boat to fish during that time period in the Gulf of Mexico. (Skips over fishing-related questions and goes to boating questions)

Q8: Asks how many days they used their boat in the two-month period in the Gulf of Mexico

Q9-Q11: are questions to determine the size of the party, duration, and cost of a typical fishing trip.

Note: Q8–Q11 will only be answered by those who reported fishing during the two-month period in the Gulf of Mexico.

Q12: Intro text for cost of fishing and graphic of gas prices in Florida over time.

Q13–Q15: Series of questions asking how many days they would have fished with different trip costs.

Q16: Question on what species they were fishing for in the Gulf of Mexico during two-month period.

Q17: Asks how many days during the two-month period, that they previously reported X number of days fishing, that they targeted gag grouper.

Q18–Q20: Questions to determine how many days would have been fished in two-month period with different gag grouper regulations.

Q21: Determine how many days the boat was used without fishing in the two-month period.

Now they Skip to Q31 on household income then ends survey.

Boating Questions

Note: Q23–Q26 will only be completed by those who answered no to Q3 (that they did not use boat for fishing).

Q23: Asks how many days they used their boat (not for fishing) during the two-month period. Note: Q24–Q30 will only be answered by those who reported boating during the two-month period.

Q24–Q26: Questions to determine the size of the party, duration, and cost of a typical boating trip.

Q27: Intro text for cost of boating and of gas prices in Florida over time.

Q28–Q30: Series of questions asking how many days they would have boated with different trip costs.

Q31: Question that ask their household income (range).

End of survey.

The printed version of the nonresponse survey will be two pages to be printed double-sided in color. It will only include questions Q1-Q11, Q21, and Q31.

Data Entry

A contractor will be used to convert returned questionnaires from the final mailing into an electronic database format using optical scanning technology. The contractor will maintain scanned images of returned questionnaires for delivery to NOAA. Questionnaires that have been damaged or are otherwise inappropriate for scanning will be manually reviewed by contractor personnel. If such questionnaires are complete and legible, the contractor will be responsible for manually key-entering survey information. Questionnaires that are illegible or missing key information will be coded as such. The contractor will develop an appropriate coding scheme for sample dispositions with input from NOAA.

All returned paper questionnaires from the final mailing into an electronic database format using optical scanning technology. The responses will be delivered in a comma separated values (CSV) file along with a complete data dictionary that corresponds with the responses received via the web survey. The contractor will work with NOAA staff to make any changes to final dataset content, coding, formatting and naming conventions for all data collection components.

Stratification

There will be no a-priori stratification; however, post stratification of the data may be possible based on survey responses.

Data Analysis: Trip Demand Model

Following Alberini et. al. (2007) we use a

single-site travel cost model recreational fishing in the Gulf of

Mexico. Specifically, we assume that an angler chooses fishing trips,

and a numeraire good,

and a numeraire good,

to

maximize utility subject to a budget constraint or

to

maximize utility subject to a budget constraint or

where

where

is

income, the price of the numeraire good is set to one, and

is

income, the price of the numeraire good is set to one, and

is

the cost per fishing trip. We further assume that fishing trips are a

function of fishing quality,

is

the cost per fishing trip. We further assume that fishing trips are a

function of fishing quality,

,

which is itself a function of fishing regulations,

,

which is itself a function of fishing regulations,

,

i.e.,

,

i.e.,

.

Fishing trips and quality are weak complements such that

.

Fishing trips and quality are weak complements such that

if

if

,

i.e. the individual does not care about quality of fishing if he

or she does not fish. The number of trips is an increasing function

of fishing quality,

,

i.e. the individual does not care about quality of fishing if he

or she does not fish. The number of trips is an increasing function

of fishing quality,

.

.

The solution to the angler problem yields the

demand function for trips,

.

In our empirical work, we assume that the for demand function based

on data from angler

.

In our empirical work, we assume that the for demand function based

on data from angler

in

scenario

in

scenario

is

linear in its arguments

is

linear in its arguments

where

is

a vector of angler characteristics, including an intercept and

income;

is

a vector of angler characteristics, including an intercept and

income;

,

,

,

and

,

and

are parameters to be estimated; and

are parameters to be estimated; and

is

an error term. The parameters can be estimated with data on

is

an error term. The parameters can be estimated with data on

,

,

,

,

,

and

,

and

for angler

for angler

in

scenario

in

scenario

.

.

We will have six observations on trips for

respondents who complete the gag grouper portion of the survey and 3

trip observations for all other anglers and boaters. The scenarios

are summarized in Table 5. There is two sources of variation in the

scenarios when collected for a set of anglers: (i) across anglers,

and (ii) across scenarios within one angler. These sources of

variation should be adequate to estimate the slope of the demand

function,

,

and the effect,

,

and the effect,

,

of changes in the bag limit.

,

of changes in the bag limit.

Table 5: Trip Scenarios

Scenario |

Price ( |

Trips ( |

Bag ( |

Base (Actual) |

p0 |

r0 |

2 |

Double price |

p1=p0*2 |

r1 |

2 |

Half price |

p1=p0/2 |

r2 |

2 |

Bag 3 |

p0 |

r3 |

1 |

Bag 1 |

p0 |

r4 |

3 |

Bag 0 (closed) |

p0 |

r5 |

0 |

The observations on fishing trips for the

scenarios are correlated within an individual if unobservable angler

characteristics influence both actual fishing trips and the stated

number of trips under the hypothetical scenarios. Therefore, we adopt

a random-effects specification to combine the actual trips and trips

under the hypothetical scenarios (e.g., Loomis (1997) and Alberini

et. al. 2007). In this case we assume that

,

with

,

with

a

respondent-specific, zero-mean component, and

a

respondent-specific, zero-mean component, and

an

i.i.d. error term.

an

i.i.d. error term.

and

and

are uncorrelated with each other, across individuals, and with the

regressors in the right-hand side of Eq. (1). The presence of the

individual-specific component of the error term (

are uncorrelated with each other, across individuals, and with the

regressors in the right-hand side of Eq. (1). The presence of the

individual-specific component of the error term ( )

result in correlated error terms

)

result in correlated error terms

within a respondent. Specifically,

within a respondent. Specifically,

,

where

,

where

is

the variance of

is

the variance of

,

for

,

for

,

whereas the variance of each

,

whereas the variance of each

is

is

,

with

,

with

being the variance of

being the variance of

.

Generalized Least Squares is used to estimate parameters while

addressing the correlation in the model.

.

Generalized Least Squares is used to estimate parameters while

addressing the correlation in the model.

The estimated parameters are used to calculate

elasticities that show the percent change in trips with a percent

change in trip cost and the bag limit. The former is given by

and the later is given by

and the later is given by

.

.

The estimated parameters are also used to calculate two welfare measures. The first captures the value of access and is the consumer surplus associated with current fishing conditions and prices:

.

.

The second captures the value of changes in fishing regulations, and is the change in surplus due to a change in bag limits (holding the prices the same):

.

.

Describe the methods used to maximize response rates and to deal with nonresponse. The accuracy and reliability of the information collected must be shown to be adequate for the intended uses. For collections based on sampling, a special justification must be provided if they will not yield “reliable” data that can be generalized to the universe studied.

We have taken steps to maximize the number of surveys completed, including making the survey a brief, concise, and clear instrument, limiting the number of open-ended questions, and revising the survey based on feedback from focus groups conducted in Tampa, FL and a pilot study (see Part B, section 22) of two counties in Florida. In addition, we will administer a nonresponse bias survey in order to examine whether or not respondents are systematically different from nonrespondents. A survey is warranted because the only information in the boat registration data that can be used to compare respondents with nonrespondents is boat length and propulsion type. Results from the pilot study suggest that the distribution of these variables are very similar between responders and nonrespondents.

In the nonresponse bias study, people who do not respond to the survey will be randomly sampled to receive a short questionnaire by first class mail imprinted with a stamp requesting the recipient to “Please Respond Within 2 weeks”. Note that we will sample from the combined set of email-only and mail-push groups of nonresponders. Based on the pilot study response rates we expect roughly 4,035 nonresponders: 2,823 from the email-only strategy and 1,212 from the mail push strategy.

A power analysis suggests that we need at least 175 nonrepsonse surveys completed in order to compare the means of the responders and nonresponders using a t-test with a significance level of 0.05 to detect an effect size of 0.3 with a power of 0.8. If we aim to obtain completed nonresponse surveys from 175 nonresponders and assume a 20% response rate, then we will need to mail surveys to 877 nonresponders: 614 based on the email-only strategy and 263 based on the mail push strategy. The nonresponse questionnaire will be a short version of the original survey with questions regarding boat usage and income. Responses to these questions will be used to examine whether respondents are systematically different from nonrespondents.

Describe any tests of procedures or methods to be undertaken. Tests are encouraged as effective means to refine collections, but if ten or more test respondents are involved OMB must give prior approval.

Prior to the survey implementation, NOAA Fisheries conducted 2 focus groups with a total of 15 anglers in Tampa, FL. Their feedback was used to revise language and questions in the survey and to ensure that material is understood and interpreted by the respondent as intended. In addition, we conducted a pilot study to test the survey and sampling strategy for the FBFS. In the pilot study we only sampled from two of the counties included in the full study. In order evaluate the response rates over the range of possible grouper fishing prevalence rates, we surveyed one county with a high estimated grouper fishing prevalence rate and one county with a low estimated grouper fishing prevalence rate. The results of the pilot study were used to (A summary of the results are presented in italics. The full results are documented in a pilot study report.):

Compare the actual and expected response rates.

Both the email-only contact and mail-push strategy response rates were higher than expected and we met the overall response rate goal.

Assess whether fishing avidity (number of trips) of the respondents are significantly different from the average avidity in the study region.

The fishing avidity estimate from the pilot study was comparable to estimates from the mail and intercept surveys of the Marine Recreational Information Program for the same period.

Assess whether gag grouper fishing prevalence of the respondents is significantly different from the prevalence assumed in the study region.

The gag grouper angler prevalance estimate from the pilot study is twice as high as we initially assumed and will significantly reduce the required overall sample size to achieve the target sample size of anglers to answer the gag grouper fishing questions.

Identify unusual patterns, such as the majority of respondents always choosing zero trips in the contingent behavior questions.

The results of the contingent behavior questions were consistent with economic theory. For example, there were no respondents who stated more trips at double the cost or fewer trips at half cost. In addition, the average stated number of trips was higher with higher bag limits and lower with lower bag limits. There were no unusual patterns in the pilot study data.

Examine response rates for individual survey questions and evaluate whether adjustments to survey questions are required to promote a higher response rate.

All questions were required in the internet version of the survey. Therefore, the respondent had to enter a response to continue with the survey. The respondents who returned the paper version of the survey could skip questions, but there were not any questions that suffered consistent nonresponse.

Provide the name and telephone number of individuals consulted on the statistical aspects of the design, and the name of the agency unit, contractor(s), grantee(s), or other person(s) who will actually collect and/or analyze the information for the agency.

Design, Analysis, Report: David W. Carter, NOAA Fisheries, 305-361-4467 Data collection: Gustavo Rubio, ECS Federal, contracting company, 301-427-8180

References

Alberini, A., Zanatta, V. and Rosato, P., 2007. Combining actual and contingent behavior to estimate the value of sports fishing in the Lagoon of Venice. Ecological Economics, 61(2-3), pp.530-541.

Brick, J.M., Andrews, W.R. and Mathiowetz, N.A., 2016. Single-phase mail survey design for rare population subgroups. Field Methods, 28(4), pp.381-395.

Carter, D.W. and C. Liese. The economic value of catching and keeping or releasing saltwater sport fish in the southeast USA. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, 32(4):613–625

Dillman, D.A., 2017. The promise and challenge of pushing respondents to the Web in mixed-mode surveys. Statistics Canada.

Gillig, D., Ozuna Jr, T. and Griffin, W.L., 2000. The value of the Gulf of Mexico recreational red snapper fishery. Marine Resource Economics, 15(2), pp.127-139.

Gillig, D., Woodward, R., Ozuna, T. and Griffin, W.L., 2003. Joint estimation of revealed and stated preference data: an application to recreational red snapper valuation. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 32(2), pp.209-221.

Haab, T., Hicks, R., Schnier, K. and Whitehead, J.C., 2012. Angler heterogeneity and the species-specific demand for marine recreational fishing. Marine Resource Economics, 27(3), pp.229-251.

Hindsley, P., Landry, C.E. and Gentner, B., 2011. Addressing onsite sampling in recreation site choice models. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 62(1), pp.95-110.

Johnston, R.J., Ranson, M.H., Besedin, E.Y. and Helm, E.C., 2006. What determines willingness to pay per fish? A meta-analysis of recreational fishing values. Marine Resource Economics, 21(1), pp.1-32.

Loomis, J.B., 1997. Panel estimators to combine revealed and stated preference dichotomous choice data. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, pp.233-245.

Lovell, S.J. and Carter, D.W., 2014. The use of sampling weights in regression models of recreational fishing-site choices. Fishery Bulletin, 112(4).

Messer, B.L. and Dillman, D.A., 2011. Surveying the general public over the internet using address-based sampling and mail contact procedures. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(3), pp.429-457.

NOAA. 2018 National Saltwater Recreational Fisheries Summit Report. URL https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/recreational-fishing/2018-saltwater-recreational-fisheries-summit. Report prepared by the Meridian Institute. August 2018.

Wallen, K.E., Landon, A.C., Kyle, G.T., Schuett, M.A., Leitz, J. and Kurzawski, K., 2016. Mode Effect and Response Rate Issues in Mixed‐Mode Survey Research: Implications for Recreational Fisheries Management. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, 36(4), pp.852-863.

Whitehead, J.C., Dumas, C.F., Landry, C.E. and Herstine, J., 2011. Valuing bag limits in the North Carolina charter boat fishery with combined revealed and stated preference data. Marine Resource Economics, 26(3), pp.233-241.

Whitehead, J.C., Haab, T., Larkin, S.L., Loomis, J.B., Alvarez, S. and Ropicki, A., 2018. Estimating Lost Recreational Use Values of Visitors to Northwest Florida due to the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Using Cancelled Trip Data. Marine Resource Economics, 33(2), pp.119-132.

Whitehead, J., Haab, T. and Huang, J.C. eds., 2012. Preference data for environmental valuation: combining revealed and stated approaches (Vol. 31). Routledge.

U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau (USFWS and USCB). 2011 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| File Title | SUPPORTING STATEMENT FLORIDA FISHING AND BOATING SURVEY OMB CONTROL NO. 0648-XXXX |

| Author | Adrienne Thomas |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-16 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy