Form 1 Attachment A FORM - MCH Block Grant Guidance_October_26_

Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant Application/Annual Report Guidance

Attachment A FORM - MCH Block Grant Guidance_October_26_2020-FINAL

Application/Annual Report with Needs Assessment Summary

OMB: 0915-0172

TITLE V MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH SERVICES BLOCK GRANT TO STATES PROGRAM

GUIDANCE AND FORMS

FOR THE

TITLE V APPLICATION/ANNUAL REPORT

APPENDIX OF SUPPORTING DOCUMENTS

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Health Resources and Services Administration

Maternal and Child Health Bureau

Division of State and Community Health

Room 18N-33

5600 Fishers Lane, Rockville, MD 20857

(Phone 301-443-2204 FAX 301-443-9354)

TABLE of CONTENTS

APPENDIX A: HISTORY AND ADMNISTRATIVE BACKGROUND 1

APPENDIX B: PERFORMANCE MEASURE FRAMEWORK & IMPLEMENTATION 5

APPENDIX C: DETAIL SHEETS FOR THE NATIONAL OUTCOME MEASURES 24

AND NATIONAL PERFORMANCE MEASURES

APPENDIX D: FAMILY PARTNERSHIP 80

APPENDIX E: NEEDS ASSESSMENT – BACKGROUND AND CONCEPTUAL 81

FRAMEWORK

APPENDIX F: ASSURANCES AND CERTIFICATIONS 86

APPENDIX G: REQUIRED APPLICATION/ANNUAL REPORT COMPONENTS 89

AND TIMELINE

APPENDIX H: FINANCIAL BUDGET AND EXPENDITURE REPORTING 91

APPENDIX I: POPULATION HEALTH & CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL 97

HEALTH CARE NEEDS

APPENDIX J: MCH WORKFORCE CAPACITY 103

APPENDIX K: GLOSSARY 105

APPENDIX A: HISTORY AND ADMINISTRATIVE BACKGROUND

As one of the largest Federal block grant programs, Title V is a key source of support for promoting and improving the health of all the nation’s mothers and children. When Congress passed the Social Security Act in 1935, it contained the initial key landmark legislation which established Title V. This legislation is the origin of the federal government’s pledge of support to states and their efforts to extend and improve health and welfare services for mothers and children throughout the nation. To date, the Title V federal-state partnership continues to provide a dynamic program to improve the health of all mothers and children, including children with special health care needs (CSHCN).

The Maternal and Child Health Bureau

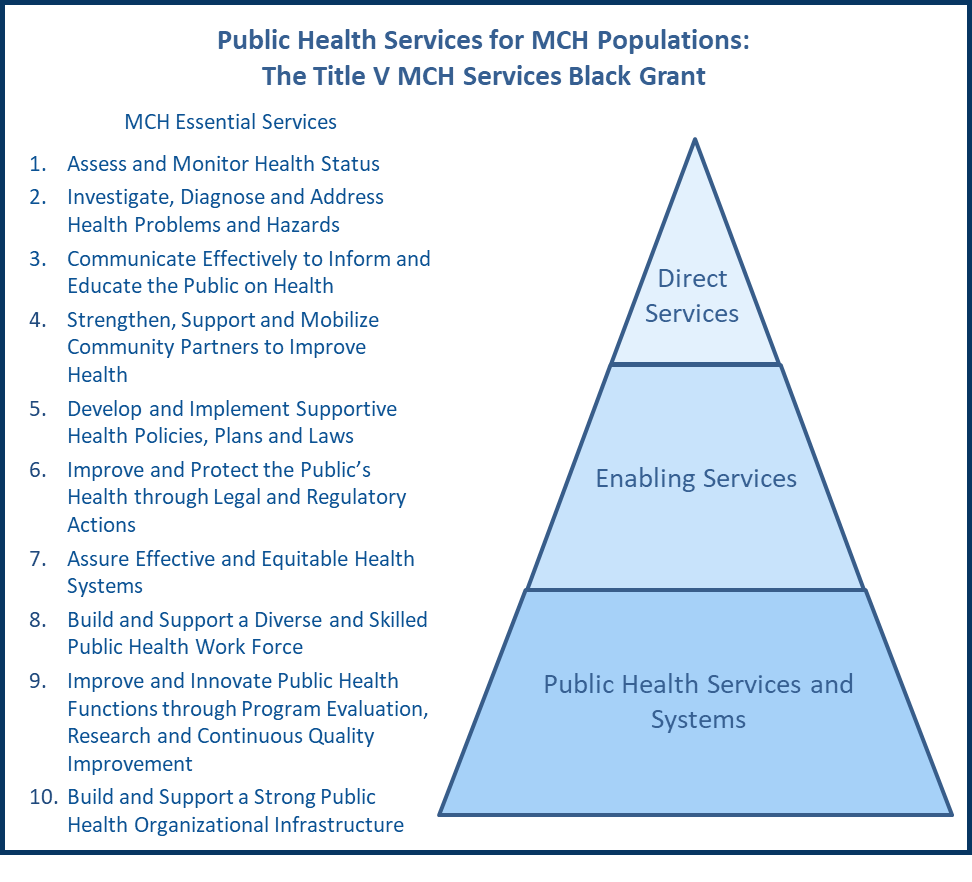

The Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) is the principal focus within Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) for all Maternal and Child Health (MCH) activities within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). MCHB’s mission is to improve the health of America’s mothers, children and families. We envision an America where all children and families are healthy and thriving. To achieve its mission, MCHB directs resources towards a combination of integrated public health services and coordinated systems of care for the MCH population.

Within the MCHB, the Division of State and Community Health (DSCH) has the administrative responsibility for the Title V MCH Services Block Grant to States Program (hereafter referred to as the MCH Block Grant). DSCH is committed to being the Bureau’s main line of communication with states and communities, in order to consult and work closely with both of these groups and others who have an interest in and contribute to the provision of a wide range of MCH programs and community-based service systems.

Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant (Title V)

Under Title V, MCHB administers a Block Grant and competitive Discretionary Grants. The purpose of the MCH Block Grant is to create federal/state partnerships in 59 states and jurisdictions for developing service systems that address MCH challenges, such as:

• Significantly reducing infant mortality;

• Providing comprehensive care for all women before, during, and after pregnancy and childbirth;

• Providing preventive and primary care services for infants, children, and adolescents;

• Providing comprehensive care for children and adolescents with special health care needs;

• Immunizing all children;

• Reducing adolescent pregnancy;

• Preventing injury and violence;

• Putting into community practice national standards and guidelines for prenatal care, for healthy and safe childcare, and for the health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents;

• Assuring access to care for all mothers and children; and

• Meeting the nutritional and developmental needs of mothers, children and families.

Under Title V, MCHB also administers two types of Federal Discretionary Grants, Special Projects of Regional and National Significance (SPRANS) and Community Integrated Service Systems (CISS) grants. SPRANS funds projects (through grants, contracts, and other mechanisms) in research, training, genetic services and newborn screening/follow-up, sickle cell disease, hemophilia, and MCH improvement. CISS projects (through grants, contracts, and other mechanisms) seek to increase the capacity for service delivery at the local level and to foster formation of comprehensive, integrated, community level service systems for mothers and children.

In addition to SPRANS and CISS grants, the MCHB also administers the following categorical programs:

• Emergency Medical Services for Children;

• Sickle Cell Disease Treatment Demonstration Program;

• Healthy Start Initiative;

• Universal Newborn Hearing Screening;

Heritable Disorder Program;

• Autism;

• Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program; and

Family to Family Health Information Centers.

In recent years, some state Title V programs have begun to utilize the life course model as an organizing framework for addressing identified MCH needs. The life course approach points to broad social, economic, and environmental factors as underlying contributors to health and social outcomes. This approach also focuses on persistent inequalities in the health and well-being of individuals and how the interplay of risk and protective factors at critical points of time can influence an individual’s health across his/her lifespan and potentially across generations.

Maternal and Child Health Block Grant (State Formula Grants)

Since its original authorization in 1935, Title V of the Social Security Act has been amended several times to reflect the increasing national interest in maternal and child health and well-being. One of the first changes occurred when Title V was converted to a block grant program as part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1981. This change resulted in the consolidation of seven categorical programs into a single block grant. These programs included:

Maternal and Child Health and Services for Children with Special Health Care Needs;

Supplemental Security Income for children with disabilities;

Lead-based paint poisoning prevention programs;

Genetic disease programs;

Sudden infant death syndrome programs;

Hemophilia treatment centers; and

Adolescent pregnancy grants.

Another significant change in the Title V MCH Block Grant came as a result of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1989, which specified new requirements for accountability. The amendments enacted under OBRA introduced stricter requirements for the use of federal funds and for state planning and reporting. Congress sought to balance the flexibility of the block grant with greater accountability, by requiring State Title V programs to report their progress on key MCH indicators and other program information. Thus, the block grant legislation emphasizes accountability while providing states with appropriate flexibility to respond to state-specific MCH needs and to develop targeted interventions and solutions for addressing them. This theme of assisting states in the design and implementation of MCH programs to meet state and local needs, while at the same time asking them to account for the use of federal/state Title V funds, was embodied in the requirements contained in the Guidance documents for the state MCH Block Grant Applications/Annual Reports.

In 1993 the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA), Public Law 103-62, required federal agencies to establish measurable goals that could be reported as part of the budgetary process. For the first time, funding decisions were linked directly with performance. Among its purposes, GPRA is intended to “...improve Federal program effectiveness and public accountability by promoting a new focus on results, service quality, and customer satisfaction.” GPRA requires each federal agency to develop comprehensive strategic plans, annual performance plans with measurable goals and objectives, and annual reports on actual performance compared to performance goals. The MCHB effort to respond to GPRA requirements coincided with other planned improvements to the MCH Block Grant Guidance. As a result, the MCH Block Grant Application/Annual Report and forms contained in the 1997 edition of the Maternal and Child Health Services Title V Block Grant Program - Guidance and Forms for the Title V Application/Annual Report served to ensure that the states and jurisdictions could clearly, concisely, and accurately tell their MCH “stories.” This Application/Annual Report became the basis by which MCHB met its GPRA reporting requirements for the MCH Block Grant to States Program.

In 1996, the MCHB began a process of programmatic assessments and planning activities aimed at improving the Title V MCH Block Grant Application/Annual Report Guidance document for states. Since that time, the Maternal and Child Health Services Title V Block Grant Program - Guidance and Forms for the Title V Application/Annual Report (Guidance) has been revised eight times. Updated Guidance documents are submitted to and approved by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) prior to their release. Revisions to each subsequent edition of the Guidance have considered changes in MCH priorities, availability of new national data sources and opportunities for refining and streamlining the Application/Annual Report preparation and submission process for states. The reduced burden that resulted from this latter commitment was largely achieved through efficiencies that were created by the electronic reporting vehicle for the state MCH Block Grant Applications/Annual Reports, specifically the Title V Information System (TVIS.)

Title V Information System

The development of an electronic reporting package in 1996 was a significant milestone for the State MCH Block Grants. Advances in technology allowed for the development of a web based Title V Information System (TVIS). The TVIS is designed to capture the performance data and other program and financial information contained in the state Applications/Annual Reports. While descriptive information is available on state Title V-supported efforts, state MCH partnership efforts and other program-specific initiatives of the state in meeting its MCH needs, TVIS primarily serves as an online, Web-accessible interface for the submission of the 59 state and jurisdictional Title V MCH Block Grant Applications/Annual Reports each year by July 15th. Developed in conjunction with the program requirements outlined in the Title V MCH Block Grant Application/Annual Report Guidance, the TVIS is available to the public on the World Wide Web at: https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/. Over the years, the TVIS has increasingly become recognized as a powerful and useful tool for a number of audiences. The “transformation” of the State MCH Block Grant program in 2015 mandated the development of a new data collection and web report system for the TVIS. HRSA continues to provide funding support for a contract to develop, maintain and enhance the TVIS annually.

Integrated with HRSA’s grants management system (i.e., the HRSA Electronic Handbooks (EHB),) the TVIS makes available to the public through its web reports the key financial, program, performance, and health indicator data reported by states in their yearly MCH Block Grant Applications/Annual Reports. Examples of the data that are collected include: information on populations served; budget and expenditure breakdowns by source of funding, service and program; program data, such as individuals served and breakdowns of MCH populations; other state data (OSD); and performance and outcome measure data for the national and state measures. Reporting on performance relative to the national measures is used to assess national progress in key MCH priority areas and to facilitate the Bureau’s annual GPRA reporting.

APPENDIX B: |

PERFORMANCE MEASURE FRAMEWORK & IMPLEMENTATION

|

Overview of the Framework

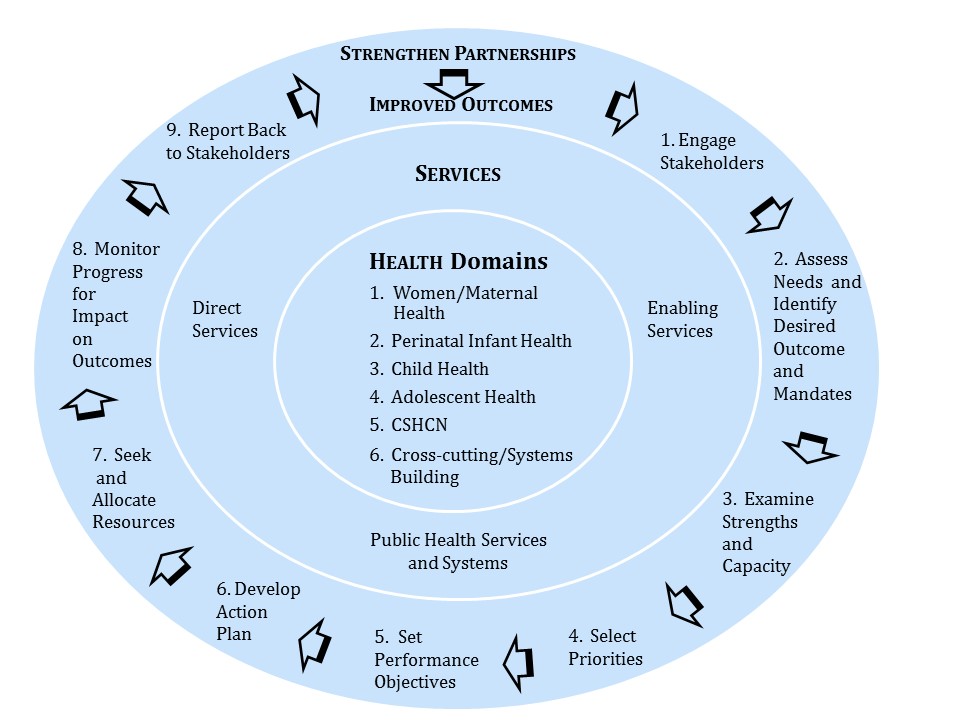

The national performance measure framework is based on a three-tiered performance measure system: National Outcome Measures (NOMs), National Performance Measures (NPMs), and Evidence-based or -informed Strategy Measures (ESMs). In brief, NOMs are the ultimate health outcomes that Title V is attempting to improve. The NPMs are considered to be more directly modifiable by state Title V program efforts and influence NOMs. ESMs are developed by states to capture their evidence-based or -informed programmatic efforts to affect NPMs and in turn NOMs. The framework is intended to highlight the impact of Title V investments and provides states with flexibility in selecting NPMs and developing state performance measures (SPMs) and ESMs to address the state’s priority needs. The minimum number of required NPM selections is five. There needs to be at least one NPM in each of the five population domains. States may select as many NPMs and SPMs as needed to reflect priority needs identified from the five-year needs assessment.

Title V Performance Measure Framework

Evaluation Logic Model

In the above figure, which compares the Title V performance measure framework to an evaluation logic model, measures were designated as NOMs, which primarily reflect longer-term indicators of population health status, if they met one or more of the following criteria: the measure was mandated by the Title V legislation that the data be collected (Table 1), even if not a long-term indicator; it was considered a sentinel health marker for women, infants, or children; it was a major focus of either the Title V legislation or Title V activities; it was considered an important health condition to monitor because the prevalence was increasing, but the reasons for the increase were unclear; or there was a recognized need to move the MCH field forward in this area, even if there was not yet a consensus on how to measure the construct. The latter were considered developmental outcome measures. There are 25 NOMs, of which 4 have additional sub-measures.

Table 1. Measures mandated by Title V legislation1

Measure |

Related NOMs |

Rate of Infant Mortality |

NOM 9.1 |

Rate of Low Birth Weight Births |

NOM 4 |

Rate of Maternal Mortality |

NOM 3 |

Rate of Neonatal Death |

NOM 9.2 |

Rate of Perinatal Death |

NOM 8 |

Number of children with chronic illness and the type of illness |

NOMs 17.1-17.4 |

Proportion of infants born with fetal alcohol syndrome2 |

NOM 10 |

Proportion of infants born with drug dependency |

NOM 11 |

Proportion of women who do not receive prenatal care during the first trimester of pregnancy |

NOM 1 |

Proportion of children by age 2 vaccinated against measles, mumps, rubella, polio, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, Hib meningitis, and hepatitis B |

NOM 22.1 |

1Sec. 506(a)(2)(B) of the Social Security Act [42 U.S.C. 706 (a)(2)(B)] https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title05/0506.htm

2Operationalized as “percent of women who drink alcohol in the last 3 months of pregnancy” due to a lack of available data on FASD prevalence.

Measures

were considered as NPMs, or short or medium term indicators of health

behaviors or health care access/quality, if they met one or more of

the following criteria: there was a large investment of resources as

determined by the state narratives; the measure was considered

modifiable through Title V activities; a state could delineate

measurable activities to address the performance measure; significant

disparities existed among population groups; research had indicated

that the condition or activity had large societal costs; or research

had indicated that the promotion of certain behaviors, practices or

policies had improved outcomes. There also had to be evidence that

an NPM was associated with at least one of the NOMs (see Table 3 in

this Appendix) for evidence-based or -informed linkages between NPMs

and NOMs). However, it is important to recognize that NOMs are

multifactorial and improvement in a given NPM may not necessarily

result in improvement of the associated NOM. Fifteen NPMs were

identified for the Title V MCH Services Block Grant.

The ESMs are the key to understanding how a state Title V program tracks programmatic investments or inputs designed to impact the NPMs. In the framework, states select evidence-based or evidence-informed strategies and activities designed to impact the NPMs; states then create ESMs to track state Title V strategies contained in the State Action Plan. The development of ESMs is guided through an examination of evidenced-based or -informed strategies, and determining what components are practical, meaningful, measurable, and moveable. The main criteria for ESMs are being meaningfully related to the selected NPM through scientific evidence or theory and being measurable by the state with improvement achievable in multiple years of the five-year reporting cycle. (The Guidance for Implementation of Performance Measurement Framework section below provides more detailed information on ESMs.)

The 15 NPMs address key national MCH priority areas in five MCH population health domains: 1) Women/Maternal Health; 2) Perinatal/Infant Health; 3) Child Health; 4) Adolescent Health; and 5) CSHCN. The five MCH population health domains are contained within the three legislatively-defined MCH populations [Section 505(a)(1).] The first two domains are included under “preventive and primary care services for pregnant women, mothers and infants up to age one,” which is the first of the three defined MCH populations. The third and fourth domains, child and adolescent health, are included in the second defined MCH population, specifically “preventive and primary care services for children.” Services for CSHCN is the third legislatively-defined MCH population. Presented in the table below are the 15 NPMs and the corresponding MCH Population domain(s) and applicable subgroup options for ESMs.

Table 2. NPMs and MCH Population Domains

NPM # |

National Performance Measures |

MCH Population Domains |

ESM Subgroup Options (if applicable) |

1 |

Well-woman visit |

Women/Maternal Health |

|

2 |

Low-risk cesarean delivery |

Women/Maternal Health |

|

3 |

Risk-appropriate perinatal care |

Perinatal/Infant Health |

|

4 |

Breastfeeding |

Perinatal/Infant Health |

|

5 |

Safe sleep |

Perinatal/Infant Health |

|

6 |

Developmental screening |

Child Health |

|

7 |

Injury hospitalization |

Child Health and/or Adolescent Health |

Children 0 through 9 Adolescents 10 through 19 All Children 0 through 19 |

8 |

Physical activity |

Child Health and/or Adolescent Health |

Children 6 through 11 Adolescents 12 through 17 All Children 6 through 17 |

9 |

Bullying |

Adolescent Health |

|

10 |

Adolescent well-visit |

Adolescent Health |

|

11 |

Medical home |

Children with Special Health Care Needs (CSHCN), Child and Adolescent Health |

CSHCN CSHCN and non-CSHCN |

12 |

Transition |

Children with Special Health Care Needs (CSHCN) and Adolescent Health |

CSHCN CSHCN and non-CSHCN |

13 |

Preventive dental visit – Pregnancy Preventive dental visit – Child/Adolescent |

Women/Maternal Health, Child Health, and/or Adolescent Health |

Pregnant women Children 0 through 5 Children 6 through 11 Adolescents 12 through 17 All Children 0 through 17 |

14 |

Smoking – Pregnancy Smoking – Household |

Women/Maternal Health, Child Health, and/or Adolescent Health |

Pregnant women Children 0 through 5 Children 6 through 11 Adolescents 12 through 17 All Children 0 through 17 |

15 |

Adequate insurance |

Child Health, Adolescent Health, and/or Children with Special Health Care Needs (CSHCN) |

All Children CSHCN |

The NPMs incorporate two significant concepts: first, Title V is responsible for promoting the health of all mothers and children, which includes an emphasis on CSHCN and their families; and second, the development of life course theory has indicated that there are critical stages, beginning before a child is born and continuing throughout life, which can influence lifelong health and wellbeing (see Table 4 in this Appendix for a crosswalk of NPM/NOMs and AMCHP Lifecourse Indicators).

A sixth domain, Cross-Cutting/Systems Building, allows states to focus on public health system issues that impact all MCH population groups. This domain does not contain any NPMs but allows states to develop unique SPMs to address priority areas that cut across all population health domains. Example SPM topics may include but are not limited to:

Family partnership activities across all population health domains;

Social determinants of health;

Health equity;

Workforce development; and

Enhancement of data infrastructure.

Implementation of Measurement

National Outcome Measures

NOMs are longer-term and/or legislatively required indicators, many of which may be influenced by NPMs (see Table 3) and are important to monitor and assess as a core function of public health that may stimulate program and policy action. Thus, NOMs should be tracked to understand the MCH population’s health, and are important for the development of the needs assessment and selection of NPMs. Changes in NOM indicators, which may result from improvement in NPMs, can be discussed in the appropriate population domain section of the narrative, but there is not a reporting requirement for this discussion. Data for NOMs will be prepopulated, where possible. States do not provide performance objectives for NOMs.

National Performance Measures

In implementing this framework, states will choose a minimum five out of 15 NPMs for its Title V program to address during the current five-year needs assessment cycle, at least one in each MCH population domain. When selecting NPMs, it is important that the alignment of the NPMs to the state identified priorities is clear. If the priority does not align with a NPM, the state should develop a state performance measure (SPM). When selecting NPM #4 or NPM #5, all sub-measures are included as part of the NPM and individual sub-measures cannot be selected as the NPM in TVIS. To promote flexibility, each MCH population domain contains at least three NPM options. There are no mandatory NPMs and no maximum for the number of NPMs that a state can select. The same measure selected in multiple domains (NPM #7, NPM #8, NPM #11, NPM #12, NPM #13, NPM #14 and NPM #15) will only count once toward the minimum of five.

For example, if a state selects a compound measure such as NPM #14 in Women/Maternal Health and Child Health, it would only count once towards the minimum of five NPMs, and another measure would need to be selected in either Women/Maternal or Child Health to satisfy the requirement of one measure in each population domain. Injury hospitalization, physical activity, medical home, preventive dental visit, household smoking, and adequate insurance can be selected for either the Child or the Adolescent Health domains, or both, because the age ranges span both domains. It is recognized that the strategies and accompanying ESMs may be different, depending on the children’s ages, for injury hospitalization, physical activity, preventive dental visit, and household smoking; therefore, these measures have various subgroup options for specifying the focus of ESMs. Given their particular importance for CSHCN, medical home and transition must include a focus on CSHCN, even if they are selected within the Child and/or Adolescent Health domain.

In

the last reporting year of the previous Guidance that expired on

12/31/2020, states selected a minimum of five NPMs to complete in

the new five-year needs assessment cycle (2021-2025).

States

will continue to report 2019 and 2020 indicator data for NPMs from

the previous needs assessment cycle (2016-2020) that they chose to

not continue into the new cycle.

Once NPMs are

selected, a state will track the five NPMs throughout the five-year

reporting cycle. States are encouraged not to change the selected

NPMs during the five-year reporting cycle. This

Guidance covers years 2-4 of the current five-year reporting cycle.

States are encouraged to continue using measures selected in the FY

2021 application (year 1 of the five-year reporting cycle). If

a state determines that a NPM needs to be changed or retired, clear

justification must be provided. In an effort to reduce state burden,

annual performance data (indicator/numerator/ denominator) for the

NOMs and the NPMs will be prepopulated by MCHB from national data

sources, as available, and provided to the states for their use in

preparing the yearly Title V MCH Services Block Grant

Applications/Annual Reports. Data will be provided overall by year

to facilitate objective-setting and performance monitoring, as well

as by various demographic stratifiers (e.g., age, race/ethnicity,

education, urban/rural residence) to identify priority populations

for targeting strategies and programmatic interventions. Performance

objectives for future years can be changed for individual NPMs based

on ongoing needs assessment efforts and performance monitoring.

![]()

![Lol_exclam[1].png](106167900_html_c9b1776d4b10db3f.gif)

States also have the opportunity to develop SPMs that will specifically impact infrastructure through the Cross-cutting/Systems Building domain to improve the areas impacting multiple population domains like family partnership and data infrastructure.

When selecting new measures it is important that the following checklist items have been satisfied.

Measure Checklist |

Check if Answer is Yes |

A minimum of 5 NPMs is selected |

□ |

There is at least one NPM selected for each population health domain

*NPM #7, #8, #11, #12, #13, #14, #15 selected in multiple domains count once toward the minimum of five |

□ |

There is a NPM/SPM for each state priority |

□ |

All selected NPMs/SPMs have clear alignment with the state priorities |

□ |

Additional guidance on use of provisional data for NPMs, lack of a national data source for NPMs, and use of integrated measures is provided below:

Use of Provisional Data: States may, but are not required to, include more timely provisional data if they choose. Providing this data will not replace the prepopulated final data provided for the measures.

Lacking a National Data Source: States can choose a measure if they do not have the data source noted on the detail sheet, as long as they provide the indicator, numerator and denominator data as defined on the detail sheet (Appendix C). For Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), states will be able to submit their PRAMS or PRAMS-like data to TVIS following the same definition for a given measure if CDC cannot furnish it. The same situation may apply to other data sources. If a state provides its own data from a different source, this should be annotated in a field note. If a state cannot provide data for a given measure with the same definition as listed on the detail sheet, the state should consider creating a SPM.

Integrated Measures (NPM #13 and NPM #14): The integrated measures of preventive dental visit and smoking have two distinct measures, one in pregnancy and one for children/adolescents. States may select these NPMs for one or more of the following MCH population domains: Women/Maternal Health; Child Health; Adolescent Health. If a state selects one of these NPMs for Women/Maternal Health (#13.1 and NPM #14.1) and also for Child and/or Adolescent Health (NPM #13.2 and NPM #14.2), states will be expected to develop multiple ESMs, at least one for each measure.

Evidence-based or -informed Strategy Measures

For each selected NPM, states must develop at least one ESM to quantify and assess the outputs of the identified State Title V strategies that are linked to each selected NPM. The main steps for developing ESMs include 1) review the evidence base for effective strategies, 2) operationalize outputs of strategy as a measure and, 3) set improvement objectives that are achievable over multiple years or throughout the five-year reporting cycle.

When

developing ESMs, remember to: Review

the evidence base

– Your state should start by choosing evidence-based or

–informed strategies that are known to impact your state’s

selected NPMs. Operationalize

outputs of your chosen strategies

– Quantifying outputs (e.g., number, percent and rate) will

allow your state will show measurable improvement over time. Set

objectives for improvement

– This provides an important check to make sure improvement

is possible and attainable.

States are only required to have at least one

active ESM for each of the NPMs selected. Most issues in MCH are

multifactorial, therefore, states are encouraged to develop multiple

strategies, each with a related ESM, to impact a selected NPM. Given

that ESMs capture state programmatic efforts, it is recommended that

states develop corresponding ESMs for strategies in which they are

investing the most activity and/or funding.

![Lol_exclam[1].png](106167900_html_c9b1776d4b10db3f.gif)

Steps for Developing ESMs:

Review the evidence base for effective strategies: This step requires a review of the evidence to select strategies that are meaningfully related to the NPMs through scientific evidence or theory. The key for selecting an effective strategy to impact an NPM is identifying evidence-based or – informed practices. Evidence-based strategies are those that have either moderate evidence or are scientifically rigorous, while evidence-informed are those that have emerging evidence or are based on expert opinion. “Evidence-informed” is meant to convey that there is information suggesting that a certain strategy could be effective in addressing a NPM. These are strategies that have not yet been rigorously tested or evaluated but that incorporate a theoretical model from other effective public health practices or apply a novel approach grounded in scientific theory. For more information on this continuum and its rationale, review the Evidence Ratings model, adapted from the Robert Wood Johnson What Works for Health project (https://www.mchevidence.org/tools/).

Beyond scientific evidence of effectiveness, additional considerations of reach, feasibility, sustainability, and transferability should be considered in terms of likely impact. It is important to note that there may be a need for states to adapt strategies based on differences in populations and settings, available resources and other considerations. A given strategy should be based on, or informed by, evidence of effective practice in direct relation to improving the NPM rather than a strategy that has an indirect relationship. An example of an indirect relationship may include efforts to improve the content or quality of well-woman or adolescent visits as a strategy for improving access or utilization. While the ESMs may be either directly or indirectly related to the NPM, states/jurisdictions are encouraged to select at least one ESM that directly corresponds to the selected NPM. The strategy should be relevant to state priorities and tailored or adapted for contextual settings and population groups where applicable. It is critical for the strategy to be feasible for the state to implement within the five-year cycle and involve stakeholder input or buy-in from partners who may be instrumental in successfully executing the strategy or tracking output. The strategy should also have potential for improvement (i.e., not already or nearly accomplished).

Operationalize the outputs of the strategy as a measure: Once the state identifies a strategy it intends to use, the state will develop and operationalize the outputs of this strategy as a measure or ESM. Given that ESMs are intended to measure progress over time, they should be quantifiable (e.g., number, percent, rate, count), well-defined and specific (i.e., specifically defined indicator, numerator, and denominator), and there should be data available to measure and track the ESM with incremental change over time.

Set improvement objectives that are achievable: The setting of improvement objectives offers an important check that improvement in the ESM is expected and attainable over multiple assessments within a reasonable time period. Objectives should reflect an improvement goal over multiple years of the five-year reporting cycle rather than a static objective over time.

The checklist below may be helpful in identifying a meaningful strategy and operationalizing the output as a measure.

ESM Checklist |

Check if Answer is Yes |

1: The strategy is meaningful |

|

The strategy is evidence-based/informed in direct relation to the NPM |

□ |

The strategy is relevant to state priorities and context |

□ |

The strategy is feasible and involved stakeholder input or buy-in |

□ |

The strategy has potential for improvement |

□ |

2: The strategy output is measurable as an ESM |

|

The ESM is a number, %, rate, count, yes/no* |

□ |

The ESM is well-defined and specific |

□ |

Data are available to measure and track the ESM over time with multiple assessments |

□ |

3: The ESM is moveable |

|

Improvement in the ESM is attainable within the 5-year needs assessment and reporting cycle |

□ |

The ESM can show incremental change over time |

□ |

*Quantitative measures are recommended over qualitative yes/no measures to quantify strategy outputs and show incremental improvement over time in relation to the NPM.

States should work closely with family partnerships as they revise and develop the ESMs for their selected NPMs. For the Title V MCH Services Block Grant, family partnership is defined as patients, families, their representatives, and health professionals working in active partnership at various levels across the health care system - direct care, organizational design, governance and policy making - to improve health and health care. 2 This partnership is accomplished through the intentional practice of working with families for the ultimate goal of positive outcomes in all areas through the life course.

Development of Detail Sheets for ESMs

As a new ESMs are introduced, a state will develop a detail sheet for each ESM, which it will submit as part of its Application/Annual Report. On the detail sheet, the state will define the: (1) measure; (2) linkage to broader framework; (3) description of evidence-based/informed strategy; (4) goal; (5) significance; (6) indicator, numerator, denominator; and (7) data source and data issues.

A Note on Count Measures – Adding a

denominator Count

measures (e.g., # providers trained) are not bad in and of

themselves and are preferable to qualitative yes/no measures to

capture the impact of a strategy. For example, it is important to

know that 200 providers received training. A count alone will not

measure the full coverage or reach of a strategy within a state. If

there are 200 providers in the state, then 100% were reached. If

there are 20,000 providers, only 1% were reached. By adding a

denominator and making the count a percentage, it is possible to

track progress relative to the actual need within a state and

understand when the strategy objective has been achieved.

![Lol_exclam[1].png](106167900_html_c9b1776d4b10db3f.gif)

Tracking of ESMs

States will track performance for the ESMs that were established for this five-year needs assessment cycle. States will determine performance objectives for each of the ESMs in the application year. These objectives can be revised, as needed, for future reporting years. Data for the ESMs (i.e., numerator/denominator) will be entered annually by the state. During the five-year reporting cycle, ESMs may be added, modified, replaced, or retired, as new strategies or measurement methods emerge, objectives are achieved without further room for improvement, or the strategy did not produce intended results.

State Performance and Outcome Measures

To

address state priorities not addressed by the National Performance

Measures, the State Performance Measures (SPMs) can be developed.

Similarly,

if the definition of the NPM does not align with the priority, the

state should develop a related SPM. For example, if the priority is

only focused on one sub-measure of an NPM such as NPM #4 or NPM #5,

then that sub-measure should be created as an SPM. There

is no minimum or maximum number of SPMs required. The combination of

NPMs with state-developed SPMs allows the state flexibility to

reflect its priority needs from the most recent Five-Year Needs

Assessment. For the developed SPMs, the state will continue with the

performance objectives for five years (FY 2021-FY 2025) for each of

the measures. A state may revise its SPM objectives in future years’

Applications/Annual Reports. The development of the SPMs coincides

with the selection of NPMs and the development of the state ESMs.

A state will develop a detail sheet for each of these measures, which will define the:

(1) measure; (2) goal; (3) indicator, numerator, and denominator; (4) data source; and

(5) significance. States will track their developed SPMs throughout the five-year reporting cycle. Data for the SPMs (i.e., indicator/numerator/denominator) will be entered annually by the state. A state can retire a SPM during the five-year reporting cycle and replace it with another SPM based on its MCH priority needs. A state is not required to develop ESMs for SPMs.

A state may also develop, if it chooses, one or more State Outcome Measures (SOMs) based on its MCH priorities, as determined by the findings of the Five-Year Needs Assessment, provided that none of the NOMs address the same priority area for the state. An SOM should be linked with a performance measure to show the impact of performance on the intended outcome. States will track the SOMs during the five-year reporting cycle and the SOM can be retired if the state chooses. Data for the SOMs (i.e., indicator/numerator/ denominator) will be entered annually by the state.

Available Resources

MCH Library

The Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Digital Library provides access to current evidence to support State Title V programs, community agencies, educators, students, researchers, policymakers, and families. The library also provides access to seminal and historic materials from federal, state, and local programs. The overarching goal of the library is to serve the MCH community with accurate, reliable, and timely information and resources.

Strengthening the Evidence Base for Maternal and Child Health Programs https://www.mchevidence.org/

This is a consortium-based project bringing multiple partners together including the National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health, National Maternal and Child Workforce Development Center, CityMatCH, AMCHP, and the Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development. The purpose of the project is to provide expert consultation, technical assistance (TA), and resources to assist state Title V MCH Block Grant programs in developing evidence based-/informed State Action Plans and strategies that advance National Performance Measures (NPMs). In addition to individual TA-requests, the MCH Evidence website provides a variety of resources to help states review evidence-based or -informed strategies and develop evidence-based or –informed strategy measures (ESMs) for each National Performance Measure.

Innovation Station

http://www.amchp.org/programsandtopics/BestPractices/InnovationStation/Pages/Innovation-Station.aspx

AMCHP’s Innovation Station is a collection of best practices and innovative strategies developed and submitted by State Title V agencies to facilitate state-to-state sharing. In addition to searching for best practices by NPM, states are able to access implementation guides, apply for funding to replicate best practices, and request technical assistance. States are invited to participate by submitting best practices or joining a MCH Population Community of Practice (CoP).

Table 3. Evidence-based/informed National Performance and Outcome Measure Linkages*

National Outcome Measure |

National Performance Measure |

|||||||||||||||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

||

# |

Short Title |

Well-woman visit |

Low-risk cesarean delivery |

Risk-appropriate perinatal care |

Breastfeeding |

Safe sleep |

Developmental screening |

Injury hospitalization |

Physical activity |

Bullying |

Adolescent well-visit |

Medical home |

Transition |

Preventive dental visit |

Smoking |

Adequate insurance |

1 |

Early prenatal care |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

Severe maternal morbidity |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

3 |

Maternal mortality |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

4 |

Low birth weight |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

5 |

Preterm birth |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

6 |

Early term birth |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

7 |

Early elective delivery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

Perinatal mortality |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

9.1 |

Infant mortality |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

9.2 |

Neonatal mortality |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

9.3 |

Postneonatal mortality |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

9.4 |

Preterm-related mortality |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

9.5 |

SUID mortality |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

10 |

Drinking during pregnancy |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

Neonatal abstinence syndrome |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

Newborn screening timely follow-up |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 |

School readiness |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

Tooth decay/cavities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

15 |

Child mortality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16.1 |

Adolescent mortality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

16.2 |

Adolescent motor vehicle death |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

16.3 |

Adolescent suicide |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

17.1 |

CSHCN |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17.2 |

CSHCN systems of care |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

17.3 |

Autism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17.4 |

ADD/ADHD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 |

Mental health treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

19 |

Overall health status |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

20 |

Obesity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

21 |

Uninsured |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

22.1 |

Child vaccination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

22.2 |

Flu vaccination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

22.3 |

HPV vaccination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

22.4 |

Tdap vaccination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

22.5 |

Meningitis vaccination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

23 |

Teen births |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

24 |

Postpartum depression |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

25 |

Forgone health care |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

* Includes linkages based on expert opinion or theory in the absence of empirical scientific evidence. Associations with available empirical scientific evidence that is mixed or inconclusive are not included. This table is subject to revision as new scientific evidence becomes available. By definition, NPMs must be linked to at least one NOM; however, not all NOMs must have linked NPMs, as they may be important to monitor as sentinel health indicators regardless.

References for Table 3

NPM-1 Well-Woman Visit

Johnson K. Posner SF, Biermann J, Cordero JF, Atrash HK, Parker CS, Boulet S, Curtis MG. Recommendations to Improve Preconception Health and Health Care—United States: A Report of the CDC/ATSDR Preconception Care Work Group and the Select Panel on Preconception Care. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006 Apr 21;55(RR-6):1-23. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5506a1.htm

Moos MK, Dunlop AL, Jack BW, Nelson L, Coonrod DV, Long R, Boggess K, Gardiner PM. Healthier women, healthier reproductive outcomes: recommendations for the routine care of all women of reproductive age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Dec;199(6 Suppl 2):S280-9. https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(08)01029-6/fulltext

NPM-2 Low-Risk Cesarean Delivery

Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:693–711. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Obstetric-Care-Consensus-Series/Safe-Prevention-of-the-Primary-Cesarean-Delivery

NPM-3 Risk-Appropriate Perinatal Care

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus And Newborn. Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics. 2012 Sep;130(3):587-97. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/3/587

NPM-4 Breastfeeding

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, França GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, Murch S, Sankar MJ, Walker N, Rollins NC; Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016 Jan 30;387(10017):475-90. http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)01024-7/fulltext

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012 Mar;129(3):e827-41. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2012/02/22/peds.2011-3552

Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Aug 15;(8):CD003517. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003517.pub2/full

Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, Chew P, Magula N, DeVine D, Trikalinos T, Lau J. Breastfeeding and Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes in Developed Countries. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2007 Apr;(153):1-186. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK38337/

NPM-5 Safe Sleep

Taskforce on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. SIDS and Other Sleep-Related Infant Deaths: Updated 2016 Recommendations for a Safe Infant Sleeping Environment. Pediatrics. 2016 Nov;138(5). http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/138/5/e20162938

Moon RY, Taskforce on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. SIDS and Other Sleep-Related Infant Deaths: Evidence Base for 2016 Updated Recommendations for a Safe Infant Sleeping Environment. Pediatrics. 2016 Nov;138(5). https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/138/5/e20162940

NPM-6 Developmental Screening

Council on Children With Disabilities; Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics; Bright Futures Steering Committee; Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006 Jul;118(1):405-20. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/118/1/405

Hagan, JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM. Bright Futures: guidelines for health supervision of infants, children and adolescents. Fourth Edition. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics. 2017.

NPM-7 Injury Hospitalization

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). VitalSigns: Child Injury. April 2012. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/childinjury/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Suicide: Facts at a Glance. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicide-datasheet-a.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth Violence: Facts at a Glance. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/yv-datasheet.pdf

NPM-8 Physical Activity

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd Edition. 2018. https://health.gov/our-work/physical-activity/current-guidelines

NPM-9 Bullying

Holt MK, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Polanin JR, Holland KM, DeGue S, Matjasko JL, Wolfe M, Reid G. Bullying and suicidal ideation and behaviors: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2015 Feb;135(2):e496-509. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/135/2/e496

NPM-10 Adolescent Well-Visit

National Adolescent and Young Adult Health Information Center (2016). Summary of Recommended Guidelines for Clinical Preventive Services for Adolescents up to age 18. San Francisco, CA: National Adolescent and Young Adult Health Information Center, University of California, San Francisco. Retrieved from http://nahic.ucsf.edu/adolescent-guidelines

Adams SH, Park MJ, Twietmeyer L, Brindis CD, Irwin CE. Increasing Delivery of Preventive Services to Adolescents and Young Adults: Does the Preventive Visit Help? J Adolesc Health. 2018 Aug;63(2):166-171. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.03.013. Epub 2018 Jun 19. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1054139X1830137X

NPM-11 Medical Home

Hadland SE, Long WE. A systematic review of the medical home for children without special health care needs. Matern Child Health J. 2014 May;18(4):891-8. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10995-013-1315-9

Homer CJ, Klatka K, Romm D, Kuhlthau K, Bloom S, Newacheck P, Van Cleave J, Perrin JM. A review of the evidence for the medical home for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2008 Oct;122(4):e922-37. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/122/4/e922

MCHB-funded National Resource Center: National Center for Medical Home Implementation, https://medicalhomeinfo.aap.org/Pages/default.aspx

NPM-12 Transition

American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, and American College of Physicians, Transitions Clinical Report Authoring Group. Clinical Report – Supporting the Health Care Transition from Adolescence to Adulthood in the Medical Home. Pediatrics. 2018: 142(5); e20182587; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2587. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/142/5/e20182587

American Academy of Pediatrics; American Academy of Family Physicians; American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002 Dec;110(6 Pt 2):1304-6. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/110/Supplement_3/1304

Campbell F, Biggs K, Aldiss SK, O'Neill PM, Clowes M, McDonagh J, While A, Gibson F. Transition of care for adolescents from paediatric services to adult health services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Apr 29;4:CD009794. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009794.pub2/abstract

Gabriel P, McManus M, Rogers K, White P. Outcome Evidence for Structured Pediatric to Adult Health Care Transition Interventions: A Systematic Review. J Pediatr. 2017 Sep;188:263-269.e15. http://www.jpeds.com/article/S0022-3476(17)30759-X/fulltext

Schmidt A, Ilango SM, McManus MA, Rogers KK, White PH. Outcomes of Pediatric to Adult Health Care Transition Interventions: An Updated Systematic Review. J Pediatr Nurs. Mar-Apr 2020;51:92-107. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2020.01.002. Epub 2020 Jan 22. https://www.pediatricnursing.org/article/S0882-5963(19)30555-X/fulltext

NPM-13 Preventive Dental Visit

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Perinatal and Infant Oral Health Care. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. 2016. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/bp_perinataloralhealthcare.pdf

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Women's Health Care Physicians; Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee Opinion No. 569: oral health care during pregnancy and through the lifespan. 2013, Reaffirmed 2017. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2013/08/oral-health-care-during-pregnancy-and-through-the-lifespan

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on periodicity of examination, preventive dental services, anticipatory guidance/counseling, and oral treatment for infants, children, and adolescents. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. 2018.

NPM-14 Smoking

The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK179276.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44324/

NPM-15 Adequate Insurance

Kogan MD, Newacheck PW, Blumberg SJ, Ghandour RM, Singh GK, Strickland BB, van Dyck PC. Underinsurance among children in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 26;363(9):841-51. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa0909994

Smith PJ, Molinari NA, Rodewald LE. Underinsurance and pediatric immunization delivery in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009 Dec;124 Suppl 5:S507-14. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/124/Supplement_5/S507.full

Smith PJ, Lindley MC, Shefer A, Rodewald LE. Underinsurance and adolescent immunization delivery in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009 Dec;124 Suppl 5:S515-21. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/124/Supplement_5/S515.full

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2009. America’s Uninsured Crisis: Consequences for Health and Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25009923/

Table 4. National Performance and Outcome Measure Crosswalk to AMCHP Life Course Indicators

National Performance or Outcome Measure |

AMCHP Life Course Indicators |

||||

# |

Short Title |

Identifier |

Thematic Category |

Indicator Name |

Brief Description |

National Performance Measure |

|||||

4B |

Breastfeeding |

LC-27* |

Family Wellbeing |

Exclusive Breastfeeding at 3 Months |

Percent of children exclusively breastfed through 3 months |

6 |

Developmental screening |

LC-19** |

Early Life Services |

Early Childhood Health Screening - EPSDT |

Percent of Medicaid-enrolled children who received at least one initial or periodic screen in past calendar year |

8.2 |

Physical activity |

LC-33 * |

Family Wellbeing |

Physical Activity Among High School Students |

Proportion of high school students who are physically active for at least 60 minutes per day on five or more of the past seven days. |

9.1 |

Bullying |

LC-12 |

Discrimination and Segregation |

Bullying |

Percent of 9-12th graders who reported being bullied on school property or electronically bullied |

11 |

Medical home |

LC-37 |

Health Care Access and Quality |

Medical Home for Children |

Proportion of families who report their child received services in a medical home |

13.2 |

Preventive dental visit |

LC-41 |

Health Care Access and Quality |

Oral Health Preventive Visit for Children |

Percent of children who received a preventive dental visit in the past 12 months |

14.2 |

Smoking |

LC-28 |

Family Wellbeing |

Exposure to Second Hand Smoke in the Home |

Percent of children living in a household where smoking occurs inside home |

National Outcome Measure |

|||||

5 |

Preterm birth |

LC-55 |

Reproductive Life Experiences |

Preterm Birth |

Percent of live births born < 37 weeks gestation |

12 |

Newborn screening timely follow-up |

LC-17** |

Early Life Services |

Early Intervention |

Proportion of children aged 0-3 years who received EI services of all children aged 0-3 years |

16.3 |

Adolescent suicide |

LC-45* |

Mental Health |

Suicide |

Suicides per 100,000 population |

17.1 |

CSHCN |

LC-25 |

Family Wellbeing |

Children with Special Health Care Needs |

Percent of children (0-17 years) with a special health care need |

20.2 |

Obesity |

LC-32A |

Family Wellbeing |

Obesity |

Percent of children who are currently overweight or obese |

22.1 |

Child vaccination |

LC-35 |

Health Care Access and Quality |

Children Receiving Age Appropriate Immunizations |

Percent of children ages 19-35 receiving age-appropriate immunizations according to the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices (ACIP) guidelines and HP 2020 Goal. |

Table 4. National Performance and Outcome Measure Crosswalk to AMCHP Life Course Indicators (Continued)

National Performance or Outcome Measure |

AMCHP Life Course Indicators |

||||

# |

Short Title |

Identifier |

Thematic Category |

Indicator Name |

Brief Description |

National Outcome Measure |

|||||

22.3 |

HPV vaccination |

LC-36A* |

Health Care Access and Quality |

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Immunization |

The proportion of adolescents ages 13-17 who receive the evidence-based clinical preventive service HPV vaccine |

23 |

Teen births

|

LC-54* |

Reproductive Life Experiences |

Teen Births |

Number of live births born to women aged 10-19 years per 1,000 women aged 10-19 years |

24 |

Postpartum depression

|

LC-44 |

Mental Health |

Postpartum Depression |

Percent of women who have recently given birth who reported experiencing postpartum depression following a live birth |

25 |

Forgone health care |

LC-39* |

Health Care Access and Quality |

Inability or Delay in Obtaining Necessary Medical Care or Dental Care |

Percent of parents reporting their child was not able to obtain necessary medical care or dental care. |

*NPM or NOM similar to AMCHP indicator (different age range or definition)

**NPM or NOM conceptually related to AMCHP indicator

Source: http://www.amchp.org/programsandtopics/data-assessment/Pages/LifeCourseIndicators.aspx

APPENDIX C: |

DETAIL SHEETS FOR THE NATIONAL OUTCOME MEASURES AND NATIONAL PERFORMANCE MEASURES |

National Outcome Measures

National Performance Measures

A.

No. |

Title V MCH Services Block Grant - National Outcome Measures |

1 |

Percent of pregnant women who receive prenatal care beginning in the first trimester |

2 |

Rate of severe maternal morbidity per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations |

3 |

Maternal mortality rate per 100,000 live births |

4 |

Percent of low birth weight deliveries (<2,500 grams) |

5 |

Percent of preterm births (<37 weeks gestation) |

6 |

Percent of early term births (37,38 weeks gestation) |

7 |

Percent of non-medically indicated early elective deliveries |

8 |

Perinatal mortality rate per 1,000 live births plus fetal deaths |

9.1 |

Infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births |

9.2 |

Neonatal mortality rate per 1,000 live births |

9.3 |

Postneonatal mortality rate per 1,000 live births |

9.4 |

Preterm-related mortality rate per 100,000 live births |

9.5 |

Sudden Unexpected Infant Death (SUID) rate per 100,000 live births |

10 |

Percent of women who drink alcohol in the last 3 months of pregnancy |

11 |

Rate of neonatal abstinence syndrome per 1,000 birth hospitalizations |

12 |

Percent of eligible newborns screened for heritable disorders with on time physician notification for out of range screens who are followed up in a timely manner. (DEVELOPMENTAL) |

13 |

Percent of children meeting the criteria developed for school readiness (DEVELOPMENTAL) |

14 |

Percent of children, ages 1 through 17, who have decayed teeth or cavities in the past year |

15 |

Child mortality rate, ages 1 through 9, per 100,000 |

16.1 |

Adolescent mortality rate, ages 10 through 19, per 100,000 |

16.2 |

Adolescent motor vehicle mortality rate ages 15 through 19 per 100,000 |

16.3 |

Adolescent suicide rate ages 15 through 19 per 100,000 |

17.1 |

Percent of children with special health care needs (CSHCN), ages 0 through 17 |

17.2 |

Percent of children with special health care needs (CSHCN), ages 0 through 17, who receive care in a well-functioning system |

17.3 |

Percent of children, ages 3 through 17, diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder |

17.4 |

Percent of children, ages 3 through 17, diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder/Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADD/ADHD) |

18 |

Percent of children, ages 3 through 17, with a mental/behavioral condition who receive treatment or counseling |

19 |

Percent of children, ages 0 through 17, in excellent or very good health |

20 |

Percent of children, ages 2 through 4, and adolescents, ages 10 through 17, who are obese (BMI at or above the 95th percentile) |

21 |

Percent of children, ages 0 through 17, without health insurance |

22.1 |

Percent of children who have completed the combined 7-vaccine series (4:3:1:3*:3:1:4) by age 24 months |

22.2 |

Percent of children, 6 months through 17 years, who are vaccinated annually against seasonal influenza |

22.3 |

Percent of adolescents, ages 13 through 17, who have received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine |

22.4 |

Percent of adolescents, ages 13 through 17, who have received at least one dose of the Tdap vaccine |

22.5 |

Percent of adolescents, ages 13 through 17, who have received at least one dose of the meningococcal conjugate vaccine |

23 |

Teen birth rate, ages 15 through 19, per 1,000 females |

24 |

Percent of women who experience postpartum depressive symptoms following a recent live birth |

25 |

Percent of children, ages 0 through 17, who were unable to obtain needed health care in the past year |

OUTCOME MEASURE 1 |

Percent of pregnant women who receive prenatal care beginning in the first trimester |

GOAL To ensure early entrance into prenatal care to enhance pregnancy outcomes. |

|

|

|

DEFINITION Numerator: Number of live births with reported first prenatal visit during the first trimester (before 13 weeks’ gestation)

Denominator: Number of live births

Units: 100

Text: Percent |

|

|

|

HEALTHY PEOPLE 2030 OBJECTIVE Related to Maternal, Infant, and Child Health (MICH) 08 Objective: Increase the proportion of pregnant women who receive early and adequate prenatal care. (Baseline: 76.4% of pregnant females received early and adequate prenatal care in 2018, Target: 80.5%) |

|

|

|

DATA SOURCES National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) For details about data source methodology, SAS code, national and states estimates, standard errors, stratifiers, and data alerts, see https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/uploadedfiles/TvisWebReports/Documents/FADResourceDocument.pdf

For national and state trends and data notes, see https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/PrioritiesAndMeasures/NationalOutcomeMeasures |

|

|

|

SIGNIFICANCE Early prenatal care is essential for identification of maternal disease and risks for complications of pregnancy or birth. This can help ensure that women with complex problems, chronic illness, or other risks are seen by specialists. Early prenatal care can also provide important education and counseling on modifiable risks in pregnancy, including smoking, drinking, and inadequate or excessive weight gain.1 Although early high-quality prenatal care is essential, particularly for women with chronic conditions or other risk factors, it may not be sufficient to assure optimal pregnancy outcomes. Efforts to improve pregnancy outcomes and the health of mothers and infants should begin prior to conception, whether before a first or subsequent pregnancy2. As many women are not aware of being pregnant at first, it is important to establish healthy behaviors and achieve optimal health well before pregnancy.2 The timeliness of prenatal care measure for health plans is part of the Core Set of Maternal and Perinatal Health Measures for Medicaid and CHIP and the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS).

(1) National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. What is prenatal care and why is it important? 2017 January 31. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/pregnancy/conditioninfo/prenatal-care

(2) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care—United States. MMWR Recommendations and Reports. 2006;55(RR-06):1–23. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5506a1.htm |

|

OUTCOME MEASURE 2 |

Rate of severe maternal morbidity per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations |

GOAL To reduce life-threatening maternal illness and complications. |

|

|

|

DEFINITION Numerator: Number of delivery hospitalizations with an indication of severe morbidity from diagnosis or procedure codes (e.g. heart or kidney failure, stroke, embolism, hemorrhage).

Denominator: Number of delivery hospitalizations

Units: 10,000

Text: Rate |

|

|

|

HEALTHY PEOPLE 2030 OBJECTIVE Identical to Maternal, Infant, and Child Health (MICH) 05 Objective: Reduce severe maternal complications identified during delivery hospitalizations. (Baseline: 68.7 per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations in 2017, Target: 61.8 per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations) |

|

|

|

DATA SOURCES Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) - State Inpatient Database (SID) For details about data source methodology, SAS code, national and states estimates, standard errors, stratifiers, and data alerts, see https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/uploadedfiles/TvisWebReports/Documents/FADResourceDocument.pdf

For national and state trends and data notes, see https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/PrioritiesAndMeasures/NationalOutcomeMeasures |

|

|

|

SIGNIFICANCE Over 25,000 women experience severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations every year. This includes significant life-threatening complications, such as hemorrhage, infection, and cardiac events, that may require lengthy hospital stays with long-term health consequences.1,2 Many more women require blood transfusions but there is significant under-reporting with the transition to ICD-10 coding and it may not reflect severe morbidity in the absence of other indicators. Rises in chronic conditions, including obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, are likely to have contributed to rises in severe maternal morbidity.1 Minority women and particularly non-Hispanic black women have higher rates of severe maternal morbidity.2

|

|

OUTCOME MEASURE 3 |

Maternal mortality rate per 100,000 live births |

GOAL To reduce the maternal mortality rate. |

|

|

|

DEFINITION Numerator: Number of deaths related to or aggravated by pregnancy, but not due to accidental or incidental causes, and occurring within 42 days of the end of a pregnancy (follows WHO definition)

Denominator: Number of live births

Units: 100,000

Text: Rate |

|

|

|

HEALTHY PEOPLE 2030 OBJECTIVE Identical to Maternal, Infant, and Child Health (MICH) 04 Objective: Reduce maternal deaths (Baseline: 17.4 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2018, Target: 15.7 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) |

|

|

|

DATA SOURCES National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) for states and territories United Nations Maternal Mortality Estimation Interagency Group for the Freely Associated States in the Pacific Basin For details about data source methodology, SAS code, national and states estimates, standard errors, stratifiers, and data alerts, see https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/uploadedfiles/TvisWebReports/Documents/FADResourceDocument.pdf

For national and state trends and data notes, see https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/PrioritiesAndMeasures/NationalOutcomeMeasures |

|

|

|

SIGNIFICANCE Maternal mortality is a sentinal indicator of health and health care quality worldwide. In 2018, the national maternal mortality rate was 17.4 deaths per 100,000 live births. There are significant racial disparities with Black women dying at more than 2.5 times the rate of White women (37.1 versus 14.7). Maternal deaths can be prevented or reduced both by improving underlying maternal health as well as health care quality for leading causes of maternal death, such as hemmorhage and preeclampsia.

|

|

|

|

OUTCOME MEASURE 4 |

Percent of low birth weight deliveries (<2,500 grams)

|

GOAL To reduce the percent of low birth weight deliveries |

|

|

|

DEFINITION Numerator: Number of live births weighing less than 2,500 grams

Denominator: Number of live births

Units: 100

Text: Percent

|

|

|

|

HEALTHY PEOPLE 2030 OBJECTIVE Related to Maternal, Infant, and Child Health (MICH) 07 Objective: Reduce preterm births. (Baseline: 10% of live births were preterm in 2018, Target: 9.4%) |

|

|

|

DATA SOURCES National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) For details about data source methodology, SAS code, national and states estimates, standard errors, stratifiers, and data alerts, see https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/uploadedfiles/TvisWebReports/Documents/FADResourceDocument.pdf

For national and state trends and data notes, see https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/PrioritiesAndMeasures/NationalOutcomeMeasures |

|

|

|

SIGNIFICANCE Low birth weight infants include pre-term infants and infants with intrauterine growth retardation1. Some risk factors for low birth weight babies include: chronic health conditions, inadequate weight gain, both young and old maternal age, poverty, smoking, substance abuse, and multiple births.1 Low birth weight infants are more likely than normal weight infants to die in the first year of life and to experience long-range physical and developmental health problems.1 Infants born to non-Hispanic Black women have the highest rates of low birth weight, particularly very low birth weight, with levels that are about two or more times greater than for infants born to women of other race and ethnic groups.2

http://www.marchofdimes.org/baby/low-birthweight.aspx

|

|

OUTCOME MEASURE 5 |

Percent of preterm births (<37 weeks)

|

GOAL To reduce the percent of all preterm, early term, and early elective deliveries. |

|

|

|

DEFINITION Numerator: Number of live births before 37 completed weeks of gestation

Denominator: Number of live births

Units: 100

Text: Percent |

|

|

|

HEALTHY PEOPLE 2030 OBJECTIVE Identical to Maternal, Infant, and Child Health (MICH) 07 Objective: Reduce preterm births. (Baseline: 10% of live births were preterm in 2018, Target: 9.4%) |

|

|

|

DATA SOURCES National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) For details about data source methodology, SAS code, national and states estimates, standard errors, stratifiers, and data alerts, see https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/uploadedfiles/TvisWebReports/Documents/FADResourceDocument.pdf

For national and state trends and data notes, see https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/PrioritiesAndMeasures/NationalOutcomeMeasures |

|

|

|

SIGNIFICANCE Babies born preterm, before 37 completed weeks of gestation, are at greater risk of immediate life-threatening health problems, as well as long-term complications and developmental delays.1 Currently, about 1 in every 10 infants are born prematurely.1 Preterm birth is a leading cause of infant death and childhood disability, accounting for at least a third of all infant deaths.1 Infants born to non-Hispanic Black women have the highest rates of preterm birth, particularly early preterm birth, with levels that are at least 1.5 times those for infants born to women of other race and ethnic groups.2 Risk factors include infection, younger and older maternal age, substance use, poverty, stress, and multiple births.1

|

|

|

|

OUTCOME MEASURE 6 |