Appendix D SurveyTryouts Focus Group Summary

Appendix D SurveyTryouts Focus Group Summary.docx

2016/20 Baccalaureate and Beyond (B&B:16/20) Full-Scale Study

Appendix D SurveyTryouts Focus Group Summary

OMB: 1850-0926

2016/20 BACCALAUREATE AND BEYOND LONGITUDINAL STUDY (B&B:16/20)

Appendix D

Survey Tryouts and Focus Group Summary

OMB # 1850-0926 v.9

Submitted by

National Center for Education Statistics

U.S. Department of Education

DECEMBER 2019

Table of Contents

Online Survey Tryouts Summary 3

In-Person Focus Group Summary 4

Topic 1: Introduction to Survey 9

Topic 2: Paying for Education 10

Topic 3: Employment and Teaching Experiences 13

Topic 4: Contacting Materials 15

Recommendations for the Full-Scale Study 21

Tables

Figures

Figure 1. Reported ease or difficulty with survey information recall 10

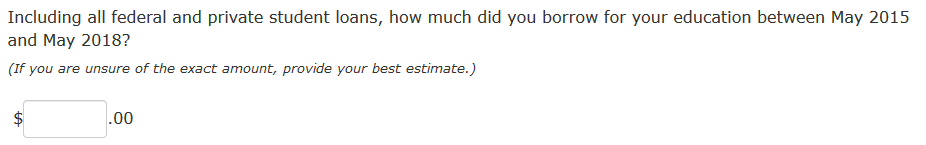

Figure 2. Example of federal and private student loan survey items. 11

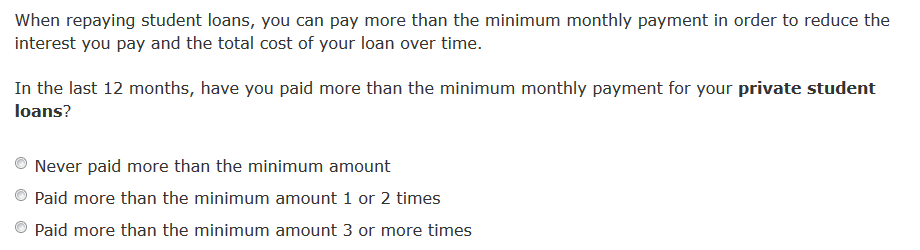

Figure 3. Monthly over-payment item example 12

Figure 4. Survey-provided reasons to pursue side jobs/informal work 14

Figure 5. Sample envelope design details 15

Figure 6. Participants' net likelihood to open a sample envelope design 16

Figure 7. Top five topic areas selected to be included in a brochure 18

Background

Pretesting in preparation for the 2016/20 Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study (B&B:16/20) survey materials and data collection materials consisted of several components: 1) online survey tryouts with individuals who completed their degree requirements between May 1, 2013 and December 31, 2014, and 2) in-person focus groups with a subsample of those who participated in the survey tryouts. Full details of the pretesting components were approved in November 2018 (OMB# 1850-0803 v. 242).

In this appendix, results from the online survey tryouts are presented first followed by a detailed report of the in-person focus group design, including sampling and recruitment, data processing, and findings. This appendix concludes with recommendations for the B&B:16/20 full-scale data collection efforts.

Online Survey Tryouts Summary

The online survey tryouts were conducted using a subset of items proposed for inclusion in the B&B:16/20 full-scale survey with targeted debriefing questions for certain questions deemed more difficult. These debriefing questions aimed at gaining an in-depth understanding into the respondents’ response process, including, for example, comprehension of questions, terminology, definitions used, and information retrieval.

Generally, respondents understood the questions in the survey and considered them easy or very easy to answer. A couple of open-ended debriefing questions did elicit information that identified areas for improved specificity and clarity in the full-scale survey, specifically:

Respondents, who borrowed student loans, were asked what types of aid they included when reporting their total amount borrowed. A few participants included student aid that was not a loan, such as Pell Grants and tuition assistance.

Respondents, who worked for pay, were asked whether they reported their earnings “before taxes and other deductions were taken out (gross pay), or did you report your take-home pay (net pay)?” Most reported gross pay but 15 percent said they reported net earnings.

The subset of substantive items included for the tryouts comprised questions from the financial aid, employment, and teaching sections of past B&B surveys and questions recommended to be newly fielded in B&B:16/20. A total of 300 surveys were completed using self-administered web surveys.

Among survey tryout respondents, 43 percent borrowed student loans to pay for education since completing a bachelor’s degree. Of those with postbaccalaureate student loans, 93 percent borrowed federal loans and 45 percent borrowed private loans. Ninety-nine percent worked for pay during the time frame of interest following the completion of a bachelor’s degree. Of those who worked, 17 percent had taught as a prekindergarten through 12th grade regular classroom teacher. A subsample of survey tryout respondents completed the survey in-person and then participated in an in-depth focus group (n=44) to debrief on the survey experience.

In-Person Focus Group Summary

RTI International, on behalf of the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), part of the U.S. Department of Education, contracted with EurekaFacts to administer in-depth in-person focus groups with bachelor’s degree recipients to refine the B&B:16/20 full-scale survey and recruitment procedures. The focus groups collected feedback from participants in the following areas:

Accuracy of data recall across a three- or four-year span of time;

Comprehension of terms in questions including updated and added terminology;

Retrieval processes used to arrive at answers to survey questions;

Mapping and reporting of responses to appropriate responses/response categories;

Sources of burden and respondent stress;

Usability and user interaction with the survey;

Perception of survey design and ease of survey navigation on all tablet and mobile devices (smartphones);

Appeal of select data collection materials, such as, envelope, brochure, and infographic designs; and

Likelihood of participation based on the appeal of the contacting materials.

Study Design

Sample

To be eligible for focus group participation, sample members had to have completed the requirements of their bachelor’s degree between May 1, 2013 and December 1, 2014, have been employed since completing their bachelor’s degree, and live within commuting distance of Rockville, Maryland where the focus groups were conducted. The target population for the focus groups was chosen based on similar criteria to the B&B:16/20 full-scale, however, with an oversample of preK-12th grade teachers. Bachelor’s degree recipients were stratified into two sub-groups based on the participant’s current or most recent employment:

PreK-12 teachers

Other, non-teacher occupations

The six focus groups consisted of 44 participants, ranging from five to ten participants per group. Due to the desire to learn specifically about teacher experiences, three of the six focus groups were comprised of individuals who worked as a preK-12 teacher in their current or most recent occupation (n=19). The remaining three focus groups included participants who were not teachers (other).

Table 1 provides a summary of participants’ demographics by occupation type.

Table 1. Percentage of focus group participants, by occupation type and enrollment and demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristic |

Total |

PreK-12 teacher |

Non-teacher |

Total |

100 |

43 |

57 |

|

|

|

|

Sex |

|

|

|

Female |

75 |

32 |

43 |

|

|

|

|

Age |

|

|

|

18-29 |

45 |

20 |

25 |

30 or older |

55 |

23 |

32 |

|

|

|

|

Race |

|

|

|

White |

25 |

14 |

11 |

Non-white |

75 |

30 |

45 |

|

|

|

|

Borrowed student Loans for bachelor's degree |

|

|

|

Yes |

77 |

36 |

41 |

|

|

|

|

Attended a postbaccalaureate degree or certificate program |

|

|

|

Yes |

68 |

43 |

25 |

|

|

|

|

Borrowed Student Loans for postbaccalaureate education |

|

|

|

Yes |

43 |

32 |

11 |

Not Applicable |

32 |

# |

32 |

|

|

|

|

Grades Taught |

|

|

|

Pre-K |

5 |

5 |

# |

K-12 |

39 |

39 |

# |

Not Applicable |

57 |

# |

57 |

|

|

|

|

Annual Income |

|

|

|

Less than $49,000 |

30 |

14 |

16 |

$50,000 to $99,000 |

55 |

23 |

32 |

$100,000 or more |

11 |

5 |

7 |

Prefer not to answer |

5 |

2 |

2 |

# Rounds to zero.

Recruitment and Screening

EurekaFacts utilized an internal panel of individuals as well as targeted recruitment and in-person outreach to individuals aged between 18 and 65 years old in the Washington, DC metro area. Recruitment materials and advertisements were distributed across social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. In-person outreach and canvasing of alumni associations at public and private 2- and 4-year institutions as well as public and private preschools in the Washington, DC metropolitan area were also conducted.

To ensure that individuals met the eligibility criteria, all interested individuals completed a screening survey. Individuals were either self-screened, using an online web-intake form, or were screened by EurekaFacts staff via phone. All individuals were screened using a screener script programmed into a CATI-like software (Verint) to guarantee that the screening procedure was uniformly conducted and instantly quantifiable. During screening, all participants were provided with a clear description of the research, including its burden, confidentiality, and an explanation of any potential risks associated with their participation in the study. Eligible participants who completed the survey online were then contacted by phone or email and scheduled to participate in a focus group session. Eligible participants who were screened by EurekaFacts staff via phone were scheduled at the time of screening.

Participants were recruited to maintain a good mix of demographics, including gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (n=44), as shown in Table 1. All focus group participants received a $90 incentive as a token of appreciation for their efforts.

Ensuring participation

To ensure maximum “show rates,” participants received a confirmation email that included the date, time, and location of the focus group, along with a map and directions for how to reach the EurekaFacts office. Participants also received confirmation information via postal mail. Any participant scheduled more than two days prior to the actual date of the session also received a reminder email 48 hours prior to the focus group session. All participants received a follow-up email confirmation and a reminder telephone call at least 24 hours prior to their focus group session, to confirm participation and respond to any questions.

Data Collection Procedure

EurekaFacts administered six 90-minute focus groups at their research facility in Rockville, MD, between February and May 2019. Each session was divided into two parts: participants first completed the B&B:16/20 web survey and then discussed their experiences completing the survey. The survey was designed to capture student loan debt and repayment and employment information. B&B:16/20 has an emphasis on the experiences of preK-12 teachers. To gather more information about teachers’ experiences, the six focus groups were loosely arranged by occupation:

PreK-12 teachers (3 sessions), and

Non-teacher occupations (3 sessions).

Data collection followed standardized policies and procedures to ensure privacy, security, and confidentiality. When the participants arrived at the EurekaFacts office, they were greeted by professionally trained hosts and asked to sign-in. The hosts also obtained the participants written consent and provided them with an ID card with a unique link to the survey. Each survey link was created using a unique identifier and not incorporating any part of the participant’s name or any other identifying information. The consent forms, which did not include the participants’ names, were stored separately from the focus group data and were secured for the duration of the study.

Focus Group Procedure

At

the scheduled start time, participants were escorted to the focus

group room and introduced to the moderator. The moderator reminded

participants that they were providing feedback on the B&B:16/20

survey and reassured them that their participation was voluntary and

that their answers would be used only for statistical purposes and

may not be disclosed, or used, in identifiable form for any other

purpose except as required by law.

At

the scheduled start time, participants were escorted to the focus

group room and introduced to the moderator. The moderator reminded

participants that they were providing feedback on the B&B:16/20

survey and reassured them that their participation was voluntary and

that their answers would be used only for statistical purposes and

may not be disclosed, or used, in identifiable form for any other

purpose except as required by law.

Participants were also informed that the session would take up to 90 minutes and be divided into two parts: completing an online survey and group discussion. After participants completed the 30-minute survey, the moderator led participant introductions before introducing the first topic for discussion.

The moderator facilitated group discussion using a moderator guide that was organized by topic area. Each topic area contained several questions and probes, which the moderator used to progress the discussion. The following topics were discussed in the focus groups:

Topic 1: Introduction to Survey

Topic 2: Paying for Education

Topic 3: Employment and Teaching Experiences

Topic 4: Contacting Materials

Topic 5: Closing

The moderator encouraged the participants to speak openly and freely. Because every focus group is different and each group requires different strategies, the moderator used a fluid structure allowing for different levels of direction, as needed.

The goal of the discussion was to gain insight into participants’ experiences taking the survey in order to identify any comprehension or usability issues and to explore participant reactions to contacting materials and brochure designs for future iterations of the recruitment for and administration of the B&B survey.

At the end of the focus group session, participants were thanked, remunerated, and asked to sign a receipt for their incentive payment.

Coding and Analysis

The focus group sessions were audio and video recorded using IPIVS recorder. During each session, a live-coder also documented main themes, trends, and patterns raised during the discussion of each topic and took note of key participant behaviors in a standardized datafile. In doing so, the coder looked for patterns in ideas expressed, associations among ideas, justifications, and explanations. The coder considered both the individual responses and the group interaction, evaluating participants’ responses for consensus, dissensus, and resonance. The coder’s documentation of participant comments and behavior include only records of participants’ verbal reports and behaviors, without any interpretation. This format allowed easy analysis across multiple focus groups.

Following each focus group, the datafiles were examined by three reviewers. Two of these reviewers cleaned the datafile by reviewing the audio/video recording to ensure all themes, trends, and patterns of the focus group were consistent with those captured in the datafile. In instances where discrepancies emerged, the two reviewers further examined the participants’ narratives, evaluated their interpretations, and discussed the participant’s narratives and their interpretations to resolve any lingering discrepancies. Then, the third reviewer conducted a spot check of the datafile to ensure quality and final validation of the data captured.

Once all the data were cleaned and reviewed, it was analyzed by topic area using the following steps:

Getting to know the data – Several analysts read through the datafile and listened to the audio/video recordings to become extremely familiar with the data. Analysts recorded impressions, considered the usefulness of the presented data, and evaluated any potential biases of the moderator.

Focusing on the analysis – The analysts reviewed the purpose of the focus group and research questions, documented key information needs, focused the analysis by question or topic, and focused the analysis by group.

Categorizing information – The analysts gave meaning to participants’ words and phrases by identifying themes, trends, or patterns.

Developing codes – The analysts developed codes based on the emerging themes to organize the data. Differences and similarities between emerging codes were discussed and addressed in efforts to clarify and confirm the research findings.

Identifying patterns and connections within and between categories – Multiple analysts coded and analyzed the data. They summarized each category, identified similarities and differences, and combined related categories into larger ideas/concepts. Additionally, analysts assessed each theme’s importance based on its severity and frequency of reoccurrence.

Interpreting the data – The analysts used the themes and connections to explain findings and answer the research questions. Credibility was established through analyst triangulation, as multiple analysts cooperated to identify themes and to address differences in interpretation.

Limitations

The key findings of this report are based solely on notes taken during and following focus group discussions. Additionally, some probes in the moderator guide were not administered to all focus groups, and even where probes were administered in all sessions, every participant did not respond to every probe due to time constraints and the voluntary nature of participation, thus limiting the number of respondents providing feedback.

Focus groups are sometimes prone to the possibility of social desirability bias, wherein some participants may agree with others simply to appear more favorable in the eyes of the group. While impossible to prevent this, the EurekaFacts moderator instructed participants that consensus was not the goal and encouraged participants to offer diverse ideas and opinions throughout the sessions.

Qualitative research seeks to develop insight and direction, rather than obtain quantitatively precise measures. The value of qualitative focus groups is demonstrated in their ability to elicit unfiltered commentary and feedback from a segment of the target population. While focus groups cannot provide definitive answers, the sessions can evaluate the degree to which respondents are able to recall information requested in the survey and accurately answer survey items and gauge participant attitudes toward study-related contacting materials.

Findings

Topic 1: Introduction to Survey

This section describes participants general impressions of the B&B:16/20 survey, including likes, dislikes, and reactions. Participants’ ability to recall information and provide accurate answers about their experiences are also summarized.

Survey Impressions

Overall, participants reported that the survey items were interesting; capturing diverse experiences with employment and earning a degree; however, some participants identified the following key difficulties and concerns:

Unclear survey items, and

Survey structure and flow.

Unclear survey items. Many participants were uncertain how best to answer some of the survey items. One participant explained that at times the wording of the question caused confusion, stating, “you had to sometimes re-read the question. Okay, what are you trying to ask in here? Someone needs to go in and tighten up some questions.” Question that were unclear, or where the participant was unsure how to provide the most accurate response also caused confusion. The following instances most frequently elicited confusion:

Uncertainty with whether to provide a net or gross pay amount;

Having to “guesstimate” an accurate job category; and

Difficulty providing an accurate response when questions offered the option to select only one response, but more than one response option applied.

Survey structure and flow. A few participants suggested that the survey should include an accurate progress bar. One participant who used their mobile device to complete the survey reported “I had no sense of my placement in the survey.” Another participant reported that a status bar would provide “an idea of where [a participant] is going” and a guide for a participant that wants to return to previously completed sections. The same participant also recommended providing an outline of the content covered in the survey, explaining “a key at the beginning of [of the survey and] how it's going to break down" would be considered helpful. Three participants felt the survey was “relatively long.” One participant that agreed the survey was lengthy explained the survey items were “too specific with details they wanted.”

Information Recall

The participants were also asked to describe how easy or difficult it was to recall information referenced in the survey. The participants were divided on whether recalling details about their experiences after completing their bachelor’s degree was easy or difficult. Of the participants who provided a response, just under half (46 percent) reported that it was difficult to recall details asked in the survey while almost four in ten (39 percent) indicated they found it to be easy (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Reported ease or difficulty with survey information recall

The following are some of the most common reasons that participants reported finding it difficult to recall details to answer survey questions:

Multiple employers, particularly regarding previous side jobs;

Information inquired about over the entirety of the three-year period; and

Providing specific monetary details such as wages or net and gross pay.

One participant described the process of providing specific details as “tedious,” explaining, “It seemed pretty tedious just remembering exact details. A lot of the side work I did involved flexible hours or it just varied a lot.” Other participants agreed that recalling more than one type of job was difficult. Participants shared that it was particularly difficult recalling payments that varied over a short or long time period, or payments that were not clearly stated on documentation that they received from their employer.

Topic 2: Paying for Education

Participants were asked about their ability to recall information and provide accurate responses about their student loans, their knowledge of Income Driven Repayment (IDR) Plans, and their opinion of the “Help Text” functionality in the survey. The questions on this topic were administered to only the first four focus groups (n=32).

Student Loan Information

During the first part of this discussion participants were asked about their ability to recall how much they borrowed in federal and private student loans and to discuss the item response options (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Example of federal and private student loan survey items

Information recall. Most participants that borrowed student loans were able to recall how much they borrowed in federal and private student loans. More specifically, twelve participants stated that they could easily recall information about their student loans for the following reasons:

Regularly reviewing monthly statements;

Being assertive about paying off their loans;

Having a particularly large or small amount borrowed; and

Having assistance from either a job or parent to pay off the loan.

Most participants who borrowed both federal and private loans were able to confidently determine the amounts that they received from each source. The participants were either able to instantly recall the amounts because they “just knew” or they used the knowledge they had to complete simple math to provide an answer to the best of their ability.

Seven participants reported a level of difficulty with recalling the amount of federal and private student loans. Difficulty occurred for participants with loans borrowed from more than one lender and participants who did not pay close attention to how much they borrowed.

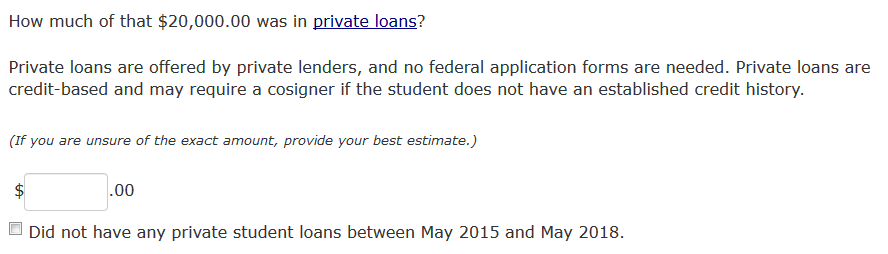

Response options. Participants were asked to provide feedback on response options offered in the student loan section of the survey. They were specifically asked to report on the relevance, accuracy, and thoroughness of the response options offered in an item about monthly over-payments (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Monthly over-payment item example

Of the participants who provided a response, most were able to provide accurate reports based on the answer options available to them; however, two similar suggestions were offered:

Add an open-ended response option; or

Add an “Other” category that would allow participants to offer a more accurate report.

Similarly, when discussing other survey item response options, most participants reported that response options that included the amount borrowed in federal student loans or a “drop-down” selection with amount ranges would be considered helpful when reporting amounts borrowed.

Some concerns about recalling the amount borrowed for a specific time frame were reported. Overall, the participants preferred response options that were not categorical and offered an open-ended response option, which was considered easier to recall and report.

Income Driven Repayment (IDR) Plans

Most participants reported familiarity with either the term or concept of Income Driven Repayment (IDR) Plans. Only a few participants disclosed that they had never heard of IDR Plans. Among the participants who reported familiarity with the term, they indicated learning about IDR plans from student loan customer service agents, their own personal research, or previously reviewed materials they received. Four participants disclosed personal experience with using IDR Plans or a similar plan.

Definitions. Participants defined IDR Plans as a student loan repayment plan that calculates an interest rate or payment by an individual’s personal income. As one participant stated, “from what I understand [an IDR Plan] is based on your income but then your interest rates go up if they base it off how much you make. So, it may not always be the best way to go because then you are going to pay more with interest. You end up paying more and for longer.” Two other participants agreed with the definition shared. Another participant added, “it is true that your interest rates will go up and you will pay more but it gives you a chance to make a dent in the payment instead of being completely deferred.”

Utilization of help text. The majority of the participants did not make use of the help text feature while completing the survey. When first probed about the usefulness of the help text feature on the survey item about IDR Plans, one participant reported using the feature to confirm their understanding of the term. Only one other participant stated that they clicked on the “Help” button while completing these remaining survey items.

The most common reasons provided for not using the help text included:

Being unaware of the feature;

Having prior knowledge on terms used; and

Understanding the items asked.

Topic 3: Employment and Teaching Experiences

Participants were asked about their understanding of the terms "side job" and "informal work," including their perceptions of why such engagements are pursued. Participants also reported on their ability to recall employment details. This section reviews the general employment section, focusing specifically on difficulty therein, and the teaching section, which was administered to and discussed with teachers only.

Side Jobs and Informal Work

Definitions. Participants were asked to define the terms “side job” and “informal work”. Of the participants who provided a response, a majority of participants described the terms “side job” and “informal work” as synonymous, while just seven provided distinct definitions for the two terms. The participants who felt the terms were synonymous most often included the phrase “extra money” (n = 12) in their definitions, often adding that the income is untaxed or earned “under-the-table.” A subset of these participants also agreed that such employment is less-than-full-time, characterized by flexible, self-determined scheduling, and outside of their career field.

Only one common theme emerged from the participants who defined the two terms differently; three of the seven participants felt that the term “informal work” described work that is not taxed. Otherwise, there was no agreement among participants who defined the terms differently.

Response

options. Participants were also

asked about the response options available to them on an item

inquiring about reasons they pursued informal work or side jobs for

pay (see Figure 4). While most felt this list was comprehensive,

several response option additions were suggested. Five participants

felt the list should include “savings,” three

participants proposed, “as a favor,” and two participants

each recommended, “for charity,” “to invest,”

and “to change careers.” The following additions were

suggested once each: to pay student loans, to gain experience, for

personal fulfillment, and to relocate.

Figure 4. Survey-provided reasons to pursue side jobs/informal work

Difficulties in the general Employment Section

Participants were asked which portions of the employment section of the survey they found difficult. Four participants found a survey item that asked for the months they engaged in side jobs and/or informal work to be difficult. In a statement that sums up the attitudes of all four of these participants, one said, “with side work there are definitely hot and cold periods and you can’t necessarily remember the exact months.”

Some participants found it difficult to rate their level of satisfaction with several characteristics at their most recent job on a five-point scale, with 1 being “very dissatisfied” and 5 being “very satisfied.” When asked how it could be made easier, they gave the following suggestions:

Allow respondents to report periods where satisfaction may vary;

Rephrase the question so that each item can be answered with a “yes” or “no;” and

Ask “are you currently happy with your situation?” instead.

Information Recall. Sixteen participants said it was easy to recall details in the employment section of the survey, and another 16 participants reported difficulty recalling employment details. Participants were able to easily recall this information for the following reasons:

Having one stable employer during the time period referenced; and

General familiarity with their resumes and/or work history.

Alternatively, sixteen participants reported having difficulty with recalling details on employment for the following reasons:

Variability in their side jobs (e.g., lack of structure, infrequency, inconsistent rates of pay, etc.)

Difficulty recalling their dates of promotion;

Needing to reference documentation of employment history (i.e., resume)

Employer industry. There was no apparent difficulty or confusion with the term “industry.” Participants described it as either the “field” their company operates in or the type of work the company does. No participants identified any unfamiliar terms or phrases in the industry items of the survey.

Overall, there were only five reports of difficulty in finding the correct industry. The main reason participants reported having difficulty was due to choosing between existing classification options, feeling that some of them encompassed others or their job could fit in more than one option. For example, a federal contractor did not know whether to classify himself as a “contracting firm” or as “a healthcare firm” due to the fact that he performs healthcare-related work.

Teachers-Only

Generally, teachers did not report having more difficulty than non-teachers. In only one case, a PreK teacher had difficulty listing a school on the survey due to working as a travelling teacher in a variety of homes and daycare centers. The participant reported being managed from an administrative office. Concerning the functionality of the survey, teachers reported scrolling and reading line-by-line as some of the most common strategies used to view longer lists, such as subjects taught, displayed in the teaching section.

Topic 4: Contacting Materials

This section reviews participant attitudes toward survey-related contacting materials. Historically, RTI and NCES use a selection of mailings to recruit participants. To optimize recruitment efforts and increase response rates, RTI sought to understand which envelope features compel potential respondents to read or discard a particular envelope. In addition to this general goal, RTI sought specific knowledge on the impact of having the study’s incentive indicated on the outside of the envelopes. To this end, four sample envelope designs with identical return addresses were presented to focus group participants for feedback: three with printed messages in the lower, right-hand corner that were designed to indicate an enclosed cash incentive and one Control Envelope that was blank in the lower, right-hand corner (see Figure 5). Participants were also presented with four sample brochures of varying formats and probed to explain which they preferred, and the best information to include, to inform the content of mailings.

Figure

5. Sample envelope design details

Figure

5. Sample envelope design details

Procedure

In each focus group session, discussion of contacting materials always began with the sample envelope designs. Each participant received a folder which contained, in this order, a paper and pencil survey regarding the envelopes, with the full set of four envelopes, a paper and pencil survey regarding the brochures, and the full set of brochure formats (as approved in OMB# 1850-0803 v.242). Following along with prompts from the moderator, participants ranked their envelope preferences on the Envelope Handout after perusing all four envelopes. To prevent order effects, presentation of the envelope designs was randomized between sessions. Before each session, the order of the physical envelopes inside the folders was changed to match the order on that session’s envelope survey. Once participants completed the envelope survey, they discussed their impressions of the envelopes in greater detail with the moderator. After completing the envelope survey and discussion, the moderator transitioned to a discussion about the study brochures. First, participants discussed the best information to include in study brochures and then completed the brochure survey. Once the brochure survey was completed, participants reviewed the set of brochures and discussed which format they preferred most.

Envelopes

Handout data. A total of 43 participants1 completed the envelope survey, indicating their likelihood of opening an envelope from “1 - Most likely to Open” to “4 - Least likely to open.” Figure 6 assesses participants' net likelihood to open all four sample envelope designs. The $2 Gift Envelope was the most top-ranked design with 31 participants selecting it as the envelope they would be likely to open, including those who ranked it as “1 - Most likely to open” (n=15) and “2 - Somewhat likely to open” (n=16). In addition, the $2 Gift Envelope was selected by only two participants as “4 - Least likely to open,” thus the $2 Gift Envelope is considered most favorable of the four designs.

Figure

6. Participants’ net likelihood to open a sample envelope

design

Contrarily, participants were least likely to open the Control Envelope (n=27); including those who ranked it as “4 - Least likely to open” (n=21) and “3 - Somewhat unlikely to open” (n=6). While the $2 Bill design was equally unlikely to be opened overall based on net values (n=27), fewer participants ranked it as “4 - Least likely to open” (n=13) compared to the control envelope. The Coffee Envelope received the fewest extreme ranks with 31 participants ranking it either a 2 or a 3 on a scale from “1 - Most Likely to Open” to “4 - Least Likely to Open.” These results indicate it was the least divisive design which perhaps made the lightest impression in either the positive or negative direction. Six participants did not respond to Question 2 of the envelope survey. Thus, 37 participants had an average likelihood to actually open their top-ranked envelope of 8.86 out of 10. Teacher responses did not deviate from the trends of the larger participant pool.

Influencing Factors. Despite being instructed to review and rank envelopes as if they had received each one in the mail, participants tended to compare the envelopes and reported that the most important factor that influenced their decision to open an envelope was that it “not look scammy or gimmicky.” Of the 39 participants who responded to the probe, 12 gave some variation of this response usually referencing a specific distaste for the $2 Bill envelope (i.e., ‘not looking scammy or gimmicky like the $2 bill envelope,’ n = 9), although two of these participants called the Coffee envelope “scammy” and one felt that all the incentive-indicating envelopes “looked like spam.”

Perceived value was the second most common factor influencing participants’ decisions to open an envelope. Eleven participants reported choosing their top-ranked envelope for this reason. Nine participants felt the most important factor was a certain degree of specificity. Interestingly, all of these participant’s top-ranked the $2 Gift Envelope, reporting that they could look at it and “know what to expect” when they open it. The remaining participants made their decision based off which envelope sparked their curiosity. Notably, four teachers took the opportunity of this discussion to explicitly report a belief that they would open any of the envelopes because the return address indicates that the envelope is from the U.S. Department of Education.

When specifically asked about the influence of the $2 Bill Envelope, 25 participants reported that the image was important in their decision to either open or not open that envelope. While nine participants felt the image sparked their curiosity to see what was inside, most participants did not view the picture of the two-dollar bill favorably. Sixteen participants reported that the image of the two-dollar bill made them less-inclined to open that envelope. Overwhelmingly, the pervasive feeling among this selection of participants was that the image made the envelope seem like a scam. Multiple participants remarked that the envelope looked “cheesy” or like “junk mail” and at least five participants felt the presence of the image of money undermined the credibility of NCES, the organization indicated in the return address.

Brochures

Handout data. Forty-two participants ranked their preferred brochure topics on the Brochure Handout2, indicating which study content should be included in the brochure. Figure 7 summarizes the five brochure topic areas most frequently selected to be included in the brochure. The content area most frequently selected to be included is the Study Content (n=31), followed by Data Use (n = 23), Privacy and Confidentiality (n = 19), Past Results (n = 12), and Study contact/help desk information (n = 12).

Figure

7. Top five topic areas selected to be included in a brochure

Figure

7. Top five topic areas selected to be included in a brochure

Participants were then asked to rank the three topic areas selected as important to include, on a scale from “1 - Most important to include” to “3 - Least important to include”. Of the five topic areas that were most frequently selected to be included in the brochure, Table 2 presents the percentage for each ranking by topic area. In addition to being most frequently selected overall, Study Content was also top-ranked more than any other topic, with 16 participants (51 percent) indicating it most important to include.

Table 2. Percent of participants who ranked the top five brochures topics most important, somewhat important, or least important to include in a study brochure

Topic areas |

Most important |

Somewhat important |

Least important |

Study Content |

52 |

26 |

23 |

Data Use |

19 |

48 |

26 |

Privacy and Confidentiality |

37 |

32 |

32 |

Past Results |

17 |

25 |

58 |

Study contact/help desk information |

17 |

8 |

75 |

Participants were then asked to indicate, on a scale from 1 to 10 (1 - Least likely, 10 - Most likely), their likelihood of reading the brochure or pamphlet received in the mail. On average, participant’s likelihood of reading a brochure received in the mail was 6.72 out of 10. Teachers 3, however, indicated being slightly more likely (7.25 out of 10) than their non-teacher counterparts (6.34 out of 10) to read a brochure or pamphlet received in the mail.

Information and Format Preferences. Twenty-eight participants responded when the moderator asked if information from the study brochures should be repeated in recruitment letters. Of these participants, most (n = 22) advocated for the repetition of study information, usually citing a belief that potential respondents who do not read the letter may read the brochure. When asked what information should be included to motivate participation, the respondents generated several topics not already included in the brochure survey. Participants indicated a desire to see incentive information in-session, while others felt the survey’s duration should be included, and some reported the purpose of the study and how it will help others should be included.

“[The

Infographic] it’s kind of like a hook of a story or a trailer

to a movie; it kind of can just get me, pull me in and then I want

to read the letter.”

The Two-Panel Brochure was the least successful brochure format, with only two participants indicating a preference for it. The Three-Panel design was preferred twice as often, and it tied the Standard Flyer format with 6 explicit reports of preference each. Participants who preferred the Three-Panel Brochure appeared most concerned with the amount of information each format was capable of holding (n = 5). One participant referred to it as “big enough to address all her concerns.” Dissimilarly, the participants who preferred the Standard Flyer all liked its brevity but usually preferred it to the Infographic because of its “simplicity” (n = 4).

Topic 5: Closing

To conclude each focus group session, participants were asked to summarize their impressions of the survey. This last section includes participants’ likes and dislikes, their opinions on the overall functionality of the survey. Throughout the six focus groups there were polarizing opinions about the survey, most notably the length of the survey and the ease of providing information asked. Due to time constraints, one focus group did not participate in this section of the discussion and other sessions focused more on “dislikes” in order to obtain more actionable feedback.

Likes. Despite several participants expressing confusion about particular sections of the survey, eleven participants described the survey as easy to complete and understand. Several participants also used the phrase “straight forward” to describe the survey. One participant described the survey as “very detailed.” Three participants stated that the survey was either not long or did not take an extensive amount of time to complete.

Dislikes. Participants were asked one at a time to describe what they liked least about the survey and why. Eight participants felt the survey items were repetitive. A participant reported “it felt like I was answering the same questions over and over again. It wasn’t too many [questions]. it was the repetition of each thing for employment, I was doing it again and again.” Seven participants reported that they least liked the length of the survey. One participant stated, “if I was voluntarily doing [the survey] at home I probably would have stopped it.”

Another common critique that participants reported while sharing their dislikes was related to the survey items about employment, particularly informal work and supplying their salary information. Two participants considered questions about employer information and/or salary information to be uncomfortable to disclose. A participant also further added, “I didn’t see how it was relevant it wasn’t connected to anything else within the survey.”

Functionality. Participants were also asked to report any difficulties that they experienced while using the tools or functions of the survey. The majority of participants reported a positive experience with the overall functionality of the survey. Some participants specifically liked the ability to return to previous items that they completed during the survey. Other participants mentioned that they liked the survey’s ability to populate information such as school names or area codes and provided notifications when a respondent provided conflicting data. Another participant also noted that they liked the embedded definitions included throughout the survey.

A few participants did report some difficulties with the functionality of the survey. Three participants noted that the survey’s usability was more difficult on the mobile device. One participant pointed out that the lack of a progress bar impacted how they answered the items later in the survey because they were not as attentive out of concern for how many items remained.

Recommendations for the Full-Scale Study

Survey Content

Findings suggest that participants generally found the survey interesting and user friendly. A main goal of testing was to understand ease and accuracy of recall within a specific three- or four-year time frame. Participants were equally split on the ease and generally reported moderately high confidence levels in the accuracy of the information they reported. Given participants somewhat positive feedback on the time frame and the benefits to data structure and consistency across rounds of data collection in a longitudinal study, this time frame will be implemented in the full-scale survey.

Survey tryouts and focus group results identified two data elements in particular that could use further clarification in the survey questions. While participants were generally confident in their reported student loan amounts borrowed and found it easy to report, some participants included grants and tuition assistance in their reported amounts borrowed while others’ reasons given for why it was easy to report suggest that some participants refer to monthly statements, which include interest on top of the original amount borrowed, for this information, specifying the types of aid that are not loans and making a distinction between amount borrowed and amount owed in the question may improve data accuracy. Participants also expressed uncertainty about whether to report gross or net earnings when asked for their pay with an employer. Explicit instructions to provide gross pay will relieve this burden and improve data quality.

Questions asking for details about “side jobs” and “informal work” were tested in the survey and proved a major source of burden for participants given the high variability of this type of work. As a newer concept to B&B, how we capture this information over greater spans of time should continue to be tested and modified before inclusion in a full-scale data collection.

Contacting Materials

Based on the results of the focus groups we recommend testing the “$2 Gift Enclosed. See details inside.” envelope (the text envelope) as part of a calibration sample in the B&B:16/20 full-scale study. We suggest a comparison to another version of the $2 bill envelope instead of a blank control since focus group participants indicated a preference for envelopes that indicated that currency was included and the value of the currency. To address the issue with the perceived ‘scammyness’ of the printed $2 bill as expressed by some participants, we recommend comparing the text envelope to an envelope that displays part of the bill used for the prepaid incentive in the window of the envelope.

Based on the focus group findings, we furthermore recommend retaining the brochure information currently already included but including an infographic in one of the reminder mailings.

1 One participant asked to leave the session early and is not included in data analysis portion of this topic area

2 One participant asked to leave the session early and another incorrectly responded to the question asked, therefore this data is not included in the results summary.

3 Results based on a total of 17 teachers who responded to this question. Two teachers did not provide a response on Q3 of the Brochure Handout

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | administrator |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-13 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy