CMS-10632_OMH_Supporting_Statement_A_clean_srs_012523

CMS-10632_OMH_Supporting_Statement_A_clean_srs_012523.docx

Evaluating Coverage to Care in Communities (CMS-10632)

OMB: 0938-1342

Evaluating Coverage to Care in Communities

Supporting Statement Part A

(CMS-10632; OMB 0938-1342)

A. Justification

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Office of Minority Health (OMH) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is requesting Office of Management and Budget (OMB) approval for the Evaluation of From Coverage to Care (C2C) in Communities study. OMB clearance for this package expired while determining (a) the information that is most useful to inform CMS OMH on future directions for C2C and (b) the most cost-effective manner to gather these data. As the decision was made to engage in a data collection effort similar to the prior effort, we wish to reinstate the prior OMB clearance with some changes.

Achieving better health and reducing health care costs requires individuals to take an active role in their health care and utilize primary and preventive care services. CMS OMH launched C2C in June 2014 to address these needs. The major goals of C2C are to help consumers (a) understand the meaning of health insurance coverage, (b) establish care with a primary care provider, (c) know when and where to seek health care services, and (d) recognize that the keys to optimal health lie in prevention and partnering with a provider. In addition, C2C aims to give providers and other stakeholders tools to promote consumer engagement and improve access to health care.

To accomplish these goals, C2C offers a variety of consumer-oriented health and health insurance educational materials that have various distribution channels, including print and digital materials. The most comprehensive of these materials is the eight-step booklet (available in print) entitled “A Roadmap to Better Care and a Healthier You,” which embodies the goals of C2C. Other C2C resources address the need for concise and topical information on each of the eight steps of the “Roadmap”, as well as current time-sensitive needs of target populations (e.g., COVID-19). The four most popular Roadmap-related materials at the time of this application, in descending order, were (1) A Roadmap to Better Care and a Healthier You Booklet, (2) Preventive Services Flyer, (3) 5 Ways to Make the Most of Your Health Coverage, and (4) Roadmap to Behavioral Health.

Currently, Coronavirus and Your Coverage: Get the Basic and Stay Safe: Getting the Care You Need, at Home are also very popular materials. Some materials are also available as single-page handouts for ease of distribution. Many materials are available in eight languages: English, Spanish, Arabic, Chinese, Haitian Creole, Korean, Russian, and Vietnamese. Materials are predominately requested in English or Spanish.

C2C is actively engaged in addressing the emerging needs of consumers and stakeholders across the entire Roadmap process: plan selection, enrollment, finding a provider, and engaging in care over time. CMS has also disseminated C2C messaging through speaking engagements, webinars, and meetings sponsored by CMS regional offices since its inception in 2014. CMS is actively filling orders for print materials and currently working on its second redesign of the C2C website. C2C content has also been directly re-distributed through local providers posting downloadable C2C materials on their websites.

This document details the proposed research activities and highlights some notable changes. The previously approved activities included two national web surveys of health care partners and health care consumers, as well as two focus groups. This proposed non-substantive request includes only the partner and consumer survey components, where these surveys would be fielded only in of the top 12 cities with the most C2C orders (Houston, San Antonio, New York, Tampa, Atlanta, Washington DC, Chicago, Mission, St. Louis, Philadelphia, Phoenix, Jacksonville, and Miami1). The differing survey strategy is consistent with our goals of comparing those exposed and not exposed to C2C materials. The proposed partner (600 previously vs. 60 proposed) and consumer (2800 previously vs. 400 proposed) surveys have smaller sample size requirements than the previously approved surveys. While much of the survey content used previously was consistent with these aims, additional survey items were needed to address these questions and some item content needed to be modified. The changes to the partner survey reflect (1) surveying those not using C2C materials (e.g., materials they use instead of C2C); (2) getting additional information on organizations (e.g., number of volunteers); and (3) changes to items to reflect current C2C efforts (e.g., asking about COVID 19 C2C materials). The changes to the consumer survey reflect (1) additional relevant items available in the Ipsos KnowledgePanel (e.g., self-reports of personal medical conditions); (2) changes due to also interviewing people with marketplace plans (e.g., addition of marketplace options); (3) measures of additional relevant constructs and refinement of prior measures (e.g., added measure of functional health literacy); and (4) changes to items to reflect current C2C efforts (e.g., asking about COVID 19 C2C materials). As mentioned later, only survey changes are detailed in Appendix E. Due to a smaller number of surveys and the same burden hours per survey (20 minutes), total survey burden costs were much higher for the prior partner ($12,117.60 previously vs. $1001.29 proposed) and consumer ($35,610 previously vs. $4,262.28 proposed) surveys.

A.1. Circumstances Making the Collection of Information Necessary

A.1.1. Overview of Request

CMS OMH has contracted with Ketchum (including the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation as an evaluation subcontractor to Ketchum) to evaluate C2C. We first provide an overview of the proposed study, then discuss the accompanying objectives justifying the need for information collection.

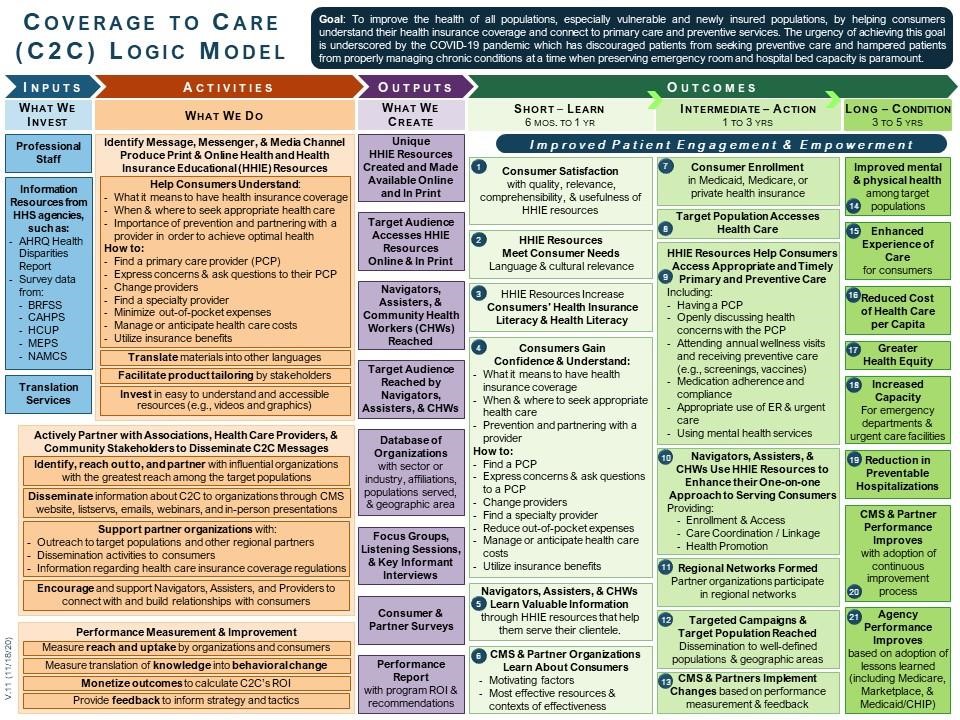

The Ketchum team has developed a Logic Model (Exhibit 1) of how to achieve the goals of the C2C program and is currently has developed an evaluation to determine whether C2C is achieving the desired program outcomes. At a broad level of abstraction, this evaluation will help CMS understand (1) how and what C2C materials are being utilized, (2) whether C2C materials increase the likelihood of desired short- and intermediate-term outcomes, and (3) the reasons why individuals are (or are not) exposed to C2C materials. We are proposing two cross-sectional surveys to accomplish these goals: one for consumers and one for partner organizations. The consumer survey will be conducted with panel members of the Ipsos KnowledgePanel who are receiving CMS services (i.e., Medicaid, Medicare, or Marketplace plan), including both those who have and have not been exposed to C2C materials. The partner survey will be conducted with partner organizations known to have requested C2C materials in the past year and similar organizations not requesting materials. The surveys will be conducted in top 12 geographic areas with a high saturation of C2C materials.

A.1.2. Study Context and Rationale

The purpose of this study is to extend our understanding from RAND Corporation’s prior study of how C2C materials are used. This will be accomplished by assessing what materials best serve partners in their efforts to activate, engage, and empower consumers and how consumers engage with or respond to C2C materials. These data collection efforts will also serve the goals of informing future consumer messaging and creating a long-term feedback loop for maintaining a relevant, successful, and engaging C2C initiative.

RAND's evaluation (specific to these surveys) was primarily designed to answer (1) what did organizations do with C2C materials and messages and (2) how did consumers use the C2C materials and messages? Considering these questions in turn, the evaluation largely found that organizational partners indicated that the primary barriers were (a) not knowing how to use insurance benefits, (b) not knowing how to access health care services, and (c) not understanding when it is appropriate to use emergency or urgent care services. Organizational partners used C2C materials to address these barriers more than half of the time. Considering the findings among consumers, (a) those with lower incomes and racial/ethnic minorities were more likely to report being exposed to C2C materials and (b) they reported greater confidence in addressing and understanding of the barriers mentioned.

We do not feel there are limitations to the study conducted by RAND and in general way, our questions are like the questions answered by RAND. It is important to consider that these findings (a) likely change over time and (b) likely change with CMS promotion of the C2C program (e.g., the relaunch of the C2C materials). We do not consider this a point of departure from RAND's study, but an examination of relationships that likely change over time. The only points of departure from the RAND study are that (a) we wish to have a better sense of the differences between C2C and non-C2C utilizing consumers, (b) we have added survey items to expand the breadth of our understanding about consumer health literacy, and (c) we wish to see what is working well among organizations who are high utilizers of C2C materials. This is of particular interest, as these materials have been redesigned with the C2C relaunch.

Exhibit 1. |

C2C Logic Model

Initial survey results will be available in early 2023, which will help fine-tune the strategy for the second portion of the 2023 relaunch of C2C and will influence strategies and techniques going forward. Further, this study opens the door for a feedback loop that may include future consumer testing to adjust and improve C2C outreach strategies to meet the changing needs of various targeted populations.

The C2C Logic Model serves as the basis of this package. The goal of C2C is to improve the health of all populations, especially vulnerable and newly insured populations, by helping consumers understand their health insurance coverage and connecting individuals to primary care and preventive services. The urgency of achieving this goal is underscored by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has discouraged patients from seeking preventive care and hampered patients from properly managing chronic conditions at a time when preserving emergency room and hospital bed capacity is paramount.

There are three main paths of information dissemination covered by the C2C Logic Model (see Exhibit 1): (a) a direct path to the consumer, (b) a path to the consumer through a partner, and (c) a role for performance measurement in improving performance (i.e., desired effect and how C2C can improve).

The partner and consumer surveys in the present evaluation build upon RAND’s earlier study by adapting their questions to the C2C Logic Model and using similar survey methodologies in the top 12 targeted geographic areas known to have received a high volume of C2C materials and messages. These research questions and sub-questions correspond to the short-term and intermediate-term outcomes on the C2C Logic Model. Thus, the foregoing is a reformulation of questions answered by RAND and a consideration of additional questions with respondents providing feedback on the new C2C relaunch materials.

A.2. Purpose and Use of the Information Collection

As noted in the prior section, the primary purpose of the study is to (1) determine what materials best serve partners in their efforts to activate, engage, and empower consumers; (2) inform future consumer messaging and outreach strategies, and (3) lay the groundwork for a long-term feedback loop aimed at continual improvement. Two data collection efforts will be conducted to address these questions.

A cross-sectional survey of partner organizations. Organizations requesting C2C materials from CMS will be identified through contact information available in product ordering reports. As with the consumer survey, this study will be restricted to the universe of organizations in the top 12 geographic areas with a high saturation of C2C material requests. Representatives of all 60 organizations identified will be invited by email and follow-up phone calls to participate in a short online survey to obtain information about (a) their organization and (b) use of materials to help connect people with health care services. All participants will be asked to identify other organizations in their area that serve similar goals. These nominations will be used to identify additional, similar organizations not requesting C2C materials as potential survey participants. This survey instrument is attached in Appendix A.

A cross-sectional survey of consumers selected from the Ipsos KnowledgePanel. We will conduct a cross-sectional online survey of members of the panel in the selected geographies who receive Medicare, Medicaid, or Marketplace plans. Both participants exposed and not exposed to C2C will be included in the sample. This survey instrument is attached in Appendix B.

Please note that in both appendices, additions to the original RAND items are noted in green text.

The purpose of the information to be collected is to answer a series of research questions based on the outcomes specified in the Logic Model. An exhaustive review of the literature was conducted to identify the factors involved in connecting individuals to providers, helping individuals navigate health insurance, and encouraging appropriate use of the health care system. The factors determined to affect or be indicators of these targeted outcomes were identified and categorized as short-term, intermediate-term, or long-term targeted outcomes of the C2C programs. The literature supporting the importance of the outcomes targeted in our Logic Model appear in Exhibit 2.

Based on the evidence supporting these outcomes, we developed a series of research questions, which appear in Exhibit 3. These research questions correspond to each of the outcomes in the Logic Model. Thus, we feel the questions in Exhibit 2 represent broad research questions in the field, while the questions in Exhibit 3 are the specific research questions to be addressed using these surveys. We also feel that the process by which individuals are exposed or not exposed to C2C becomes an important contextual question, as C2C cannot have an impact unless the materials are reaching the targeted partner organizations and consumers. As such, our first two research questions pertain to process measures, in order to explore why the target audience is or is not exposed to C2C, separately for consumers and partners. Similarly, we have classified each of our targeted outcomes as partner or consumer outcomes. It should be noted that some long-term outcomes are not represented in our research questions, as we are not proposing a longitudinal study following participants beyond this one-time survey.

The first pathway looks at the subset of the population that is known to have a chronic condition. When comparing the group of respondents who have been exposed to C2C resources against those that have not, answers to survey questions will help us to determine if exposure to C2C messaging is related to: (1) access to a PCP, (2) screening and diagnosis of the chronic condition, (3) provision of a chronic disease management regimen, (4) patient adherence and compliance with that regimen (including medication and suggested behavioral changes such as diet and exercise), and (5) an improved self-reported health status, including whether the clinical indicator associated with the chronic condition (such as high blood pressure, A1C level, or LDL level) is within the well-managed range due to consumer engagement with the PCP (step 1) leading to steps 2–5. From answers to steps 1–4, we can predict (by reference to past studies) the proportion of a population that will move from a poorly managed or at-risk state to a well-managed condition. Step 5 will help corroborate that prediction. Medical and productivity costs of poorly managed chronic disease can be estimated by reference to the literature to determine cost savings for those that move from poorly managed to well-managed and from at-risk to well-managed.

Exhibit 2. |

Evidence Base for Logic Model Outcomes

Outcome Number |

Brief Description of Short-Term Outcome |

Associated Evidence |

1 |

Consumer satisfaction with HHIE information received |

|

2 |

Consumers report HHIE materials met their needs |

Ghaddar et al. (2018), Han (2018), Hero et al. (2019), Patel et al. (2019), Politi et al. (2016b), Politi et al. 2020, Villagra et al. (2019) |

3 |

Consumers report HHIE materials improved their HIL and HL |

Champlin et al. (2017), Hero et al. (2019), Hoerl et al. (2017), Levy et al. (2016), Norbeck (2018), Patel et al. (2019), Politi et al. (2020), Villagra et al. (2019) |

4 |

Consumers understand and feel confident about key HIL and HL concepts |

Brown et al. 2016, Champlin et al. (2017), Han (2018), Ketterman Jr. et al. (2018), Patel et al. (2019), Politi et al. (2020), Politi et al. (2016b), Tipirneni et al. (2020) |

5 |

Insurance navigators learned from HHIE resources |

Chandrasekar et al. (2016), Flores et al., (2016), Giovannelli et al. (2016), Leininger et al. (2011), McManus et al. (2020), Ray et al. (2017), Yarger et al. (2017) |

6 |

CMS/organizational partners learn about consumer motivations and HHIE resource impact |

Chen et al. (2009), Crocetti et al. (2012), Furl et al. (2018), Gany et al. (2015), Giovannelli et al. (2016), Hearst et al. (2010), Huhman et al. (2016), Lee et al. (2015), Leininger et al. (2011), McLeod et al. (2013), McManus et al. (2020) |

Outcome Number |

Brief Description of Intermediate-Term Outcome |

Associated Evidence |

7 |

Consumer enrollment in health insurance |

Ali et al. (2018), Chandrasekar et al. (2016), Chen et al. (2009), Cousineau et al. (2011), Edward et al. (2018), Furl et al. (2018), Gany et al. (2015), Hoerl et al. (2017), Hom et al. (2017), McLeod et al. (2013), Norbeck (2018), Shafer et al. (2018), Wright et al. (2017) |

8 |

Target population able to access care |

Edward et al. (2018), Furl et al. (2018), Gany et al. (2015), Han (2018), Levy et al. (2016), Norbeck (2018), Tipirneni et al. (2020) |

9 |

Consumers report HHIE resources helped them access primary and preventive care |

Tipirneni et al. (2020) |

10 |

Insurance navigators used HHIE resources to enhance service to consumers |

Chandrasekar et al. (2016), Flores et al. (2016), Giovannelli et al. (2016), McManus et al. (2020) |

Outcome Number |

Brief Description of Intermediate-Term Outcome |

Associated Evidence |

11 |

Regional networks formed, and partner organizations join networks |

Valente et al. (2008), Ray et al. (2017) |

12 |

Targeted dissemination campaigns and population reached |

Ali et al. (2018), Chandrasekar et al. (2016), Flores et al. (2016), Chen et al. (2009), Cousineau et al. (2011), Hom et al. (2017), Shafer et al. (2018) |

13 |

Insurance navigators implement changes based on performance feedback |

Chandrasekar et al. (2016) |

Outcome Number |

Brief Description of Long-Term Outcome |

Associated Evidence |

14 |

Improved mental and physical health for target populations |

Furl et al. (2018) |

15 |

Enhanced experience of care for individuals |

Norbeck (2018) |

16 |

Reduced per capita cost of health care |

|

17 |

Greater health equity |

|

18 |

Increased capacity for EDs and urgent care facilities |

Lee et al. (2015) |

19 |

Decrease in preventable hospitalizations |

|

20 |

Insurance navigator performance improves with continuous improvement process |

Chandrasekar et al. (2016) |

21 |

Agency performance improves with adoption of lessons learned |

|

Exhibit 3. |

Evaluation Questions by Data Collection Component |

Questions Pertaining to Process Measures Consumers

Partners

|

Questions Pertaining to Short-Term Outcomes Consumers

|

Questions Pertaining to Intermediate-Term Outcomes Consumers

(including check-ups, screenings, and vaccinations)? (INT9)

Partners

|

Questions Pertaining to Long-Term Outcomes Consumers

|

The second pathway for the ROI analysis concerns the prevention of serious medical conditions through the use of preventive services such as annual well-visits, vaccine immunizations, cancer screenings, and behavioral health assessments. Consumer survey responses for those exposed to C2C resources versus those not exposed will reveal if exposure to C2C resources is related to: (1) access to a PCP, (2) provision of preventive services, (3) provision of further diagnosis when screenings or assessments indicate the possible presence of cancer or a behavioral health issue, (4) provision of a treatment regimen (5) patient adherence and compliance with that regimen (including clinical treatment, medication adherence and compliance with suggested behavioral changes such as diet and exercise), and (6) an improved self-reported health status, including whether the clinical indicator associated with the physical or behavioral health condition improves. The cost of diagnosis and treatment will be compared against the eventual medical and productivity costs for cases that fail to be detected and treated in earlier stages.

Our literature review stimulated further exploratory questions pertaining to the barriers to becoming engaged with one’s health care. More specifically, we suspect that there are two pathways to reach consumers: directly or through a partner. Part of the goal of the proposed survey research is to test this hypothesis. We will test whether the answers to certain demographic specifications help define consumer typology and predict motivators and hindrances to action. The specific exploratory questions to be examined are whether the following two clusters of individuals emerge:

A more active group that can seek out information and act upon it with little or no additional help. This group is proficient in English, has been in the U.S, longer, and has some experience with the health care system. This group is associated with the Consumer Direct Path.

A more passive group that depends upon the advice and influence of intermediaries to become activated. This group is not as proficient in English, has been in the U.S. for a shorter period of time, has a lower income, has no (or little) prior use of the health care delivery system, is a member of a racial or ethnic minority, and may also have a disability. This group is associated with the Partner Path to Consumer.

With this hypothesis in mind, we will ask consumers directly and partners answering on behalf of the consumers they serve: what are the barriers to enrolling in health care insurance, identifying a primary care physician, and using preventive services and behavioral health care?

Based on the extant literature, we suspect these barriers include cost (premium, co-insurance, and deductible), language barriers, health insurance literacy, habit, distrust, and fear. Once the barriers are identified and ranked, C2C will be in a position to work with partners to co-design messages and materials to overcome these barriers.

A.3. Use of Improved Technology and Burden Reduction

To reduce burden on respondents, both the consumer and partner surveys will be implemented online using computer-assisted data collection programs. The partner survey will be programmed by Ketchum team staff and hosted by Qualtrics. The consumer survey will be programmed and hosted by Ipsos. Both platforms confer the benefits of managing the data collection process (e.g., questionnaire layout, skip patterns), circumventing data coding errors, and producing the final dataset. Both systems allow users to begin surveys, save responses, and go back later to complete surveys. Ipsos offers technical assistance for respondents through email and a toll-free hotline for the consumer survey. Ipsos also has the capability to conduct surveys through phone interviews and paper administration as necessary for the consumer survey if the internet is not available. Technical support and telephone-based interviewing are options that will be offered by the Ketchum team for the partner survey.

We have not yet begun implementing the consumer survey with Ipsos, and we have not yet begun implementing the partner survey in Qualtrics. As such, no illustrative screen captures are available for either survey. Nonetheless, both platforms are well established and have demonstrated their reliability with many studies of similar scope and complexity. Both platforms also provide an interface that is easy for respondents to use. Screenshots can be submitted prior to study launch if requested by OMB.

A.4. Efforts to Identify Duplication and Use of Similar Information

The present C2C evaluation was primarily designed to answer questions that cannot be answered with existing data. CMS has conducted an exhaustive environmental scan of consumer outreach efforts, which has served as the basis for our logic model. Nonetheless, the questions to be answered by this study are not answered in the extant research. A more thorough discussion of what was found in RAND’s prior study and the additional benefits conferred by this study appear in section A.1.2.

The present study places current C2C efforts in the context of whether (or not) individuals are exposed to C2C. Any informational campaign can only be successful inasmuch as the information reaches the target audience. This evaluation will provide new information on what methods can be best used by CMS to reach its target audiences. It will also provide more outcome-focused information on the C2C program, assessing the outcomes of those exposed to C2C materials, relative to those not exposed.

A.5. Impact on Small Business or Other Small Entities

Minimal impacts on small businesses are expected, as only one person from each small business will be asked to participate in a survey that will last no longer than 20 minutes. Also, individuals are able to complete the survey during a time period that is convenient for them (e.g., outside of work hours), as to not affect their workflow.

A.6. Consequences of Collecting Information Less Frequently

All survey components proposed are cross-sectional, so data will only be collected once from any survey participant. The primary consequence of not collecting these data is that C2C would not have current information to (1) understand why consumers and partners do and do not use C2C materials; (2) understand what materials are positively impacting consumers and why; and (3) inform future healthcare utilization messaging for consumers.

A.7. Special Circumstances Relating to the Guidelines of 5 CFR 1320.5

No special circumstances surround the proposed data collection.

A.8. Comments in Response to the Federal Register Notice and Efforts to Consult Outside the Agency

CMS published a 60-day Federal Register Notice (86 FR 12192) on (03/02/2021) in the Federal Register announcing the agency’s intention to request an OMB review of this information collection activity in accordance with the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995 (Pub. L. 104-13) and Office of Management and Budget (OMB) regulations at 5 CFR Part 1320 (60 FR 44978, August 29, 1995). No comments were received during the comment period. CMS published a 30-day Federal Register Notice (86 FR 24624) on (05/07/2021) in the Federal Register.

Much of the survey content, as well as much of the survey approach, was used by RAND in their prior study. Thus, many of the measures and implementation protocols have been field tested.

A.9. Explanation of Any Payment or Gift to Respondents

Incentives have been shown to increase the likelihood of survey response and completion (Sing & Ye, 2013), while not introducing response biases (Young et al., 2015). A $35 gift card will be used for the partner survey as an incentive to participate A token economy is used for the

KnowledgePanel, where participants are offered points to complete the survey. These points can be redeemed for cash, merchandise, gift cards, or game entries. The offered point value is roughly worth $5. We feel the selected incentive values increase the likelihood of survey response but are not large enough to be considered excessive or coercive.

A.10. Assurance of Privacy Provided to Respondents

All responses collected for this survey will remain confidential to the extent permitted by law, and all consumers and partners participating in the surveys will be notified of this. Survey participants will be notified through an informed consent process (a) the purpose of the study, (b) that their data will only be reported in aggregate, (c) their rights as research participants, (d) the potential risks and benefits of the study, and (e) who to contact if they have questions about the study or their rights as a research participant. All study procedures were deemed exempt through the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation’s Institutional Review Board under 45 CFR 46.104(d)(2)(iii).

Both the partner and consumer surveys will present the informed consent on the introductory screen of the survey, and participants will only be allowed to continue to the survey if they give their consent to participate in the survey. The consent scripts for the partner and consumer surveys appear at the beginning of Appendices A and B, respectively.

Additional safeguards will be put in place to assure the data remain confidential. The names and other kinds of personal identifiers will not appear in the data for the partner and consumer surveys. Personal identifiers will be available in the sampling frame for the consumer survey; however, all organizations will be assigned a numeric identifier and only these identifiers will appear in the data. The same numeric identifier will be applied to data provided by CMS on the organization (e.g., materials requested, history of orders). After partner survey fielding is completed and these data sets have been merged, the key identifying organizations will be destroyed, effectively de-identifying the partner data. The consumer survey data provided by Ipsos to the Ketchum team will never contain personal identifiers. Thus, these procedures should maintain confidentiality for both surveys. Further, all reporting to CMS will involve reporting only on aggregate data (e.g., averages, percentage selecting a response).

A.11. Justification for Sensitive Questions

No sensitive questions are asked in the partner organization survey; however, consumers are asked about their health care utilization, which could be considered sensitive information. The proposed consumer survey collects information that is considered protected health information (PHI); however, we believe this burden is justified, and the data will be de-identified, posing little risk to survey participants. There are two sources of health information being used for the present survey: existing data already collected from the KnowledgePanel survey panel and data collected as part of the proposed survey effort. As shown in Appendix B, general information on health conditions is collected; however, no specific identifiers are associated with these data (e.g., names, diagnosis dates, identifiers of small geographies). The second source of PHI collected are items in our survey inquiring about whether participants have one of three common health conditions (hypertension, diabetes, or heart disease) and whether they have been receiving preventive care for their condition. Again, we are not collecting specific identifying information (e.g., service dates, specific tests received). Nonetheless, as these data fall under the purview of the HIPAA Privacy Rule (164.514), we will take special care to assure that all data received by the Ketchum team will be de-identified by Ipsos prior to receipt.

Safe Harbor de-identification [164.514(b)(2)] will be used by Ipsos, where (a) names will be removed from the data, (b) state (or the first two digits of the zip code) will be the only

geographic identifier in the data, and (c) all dates of services and identifying elements specified in 164.514(b)(2) (e.g., medical record numbers) will be removed from the data. Further, KnowledgePanel participants are aware, through an informed consent process, that their data is being used for research purposes, that their responses will be kept confidential, and that responses will only be reported in aggregate form. Even though we see the sensitivity of these items as low, participants are always given the option to skip questions that cause them discomfort, and they are notified of this in the informed consent process. We believe the potential benefits conferred by this use of PHI outweighs the potential burdens and risks. Specifically, this information is needed for a return-on-investment analysis to determine if the investment by CMS in producing and circulating C2C materials is offset by the return of greater preventive care utilization among those with common chronic conditions.

A.12. Estimates of Annualized Burden Hours and Costs

There are no direct financial burdens on survey participants in completing the survey, but there are indirect burdens for participants in spending their time completing the web surveys. This annualized estimate of burden is listed in Exhibit 4. This also serves as an estimate of the total burden, as all data will be collected within the span of one year.

We estimated burden separately for the consumer and partner surveys, based on the time we expect it will take individuals to complete the survey, as well as the anticipated salaries of the participants. We suspect individuals in the partner survey predominately will have a bachelor’s degree, and individuals who participate in the consumer survey will have a high school or some college education. We chose to use some college education, as it provides a better estimate of the upper bound of the cost for consumers. Using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020b) on median incomes by education level, the hourly wage (assuming 40 hours per week) for those with some college was $22.60 and those with a bachelor’s degree was $35.40. Further, assuming fringe benefits comprise 30% of total compensation from employers (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020a), total compensation including fringe benefits was estimated to be $32.29 per hour for individuals with some college education and $50.57 per hour for individuals with a bachelor’s degree. To arrive at total costs, we first calculated total burden hours as the product of number of respondents, number of responses per respondent, and average burden hours. The product of total burden hours and hourly wage (including fringe benefits) helps us arrive at the total burden hours and total burden costs by survey and overall. As shown in Exhibit 4, estimates for the consumer survey are 19.80 burden hours with a cost of $1,001.29, and the estimates for the partner survey are 132.00 burden hours with a cost of $4,262.28. This leads to a grand total of 151.80 burden hours with a cost of $5,263.57.

Exhibit 4. |

Annual Burden and Cost Estimates

Survey |

Annual Number of Respondents |

Number of Responses Per Respondent |

Average Burden Hours Per Response |

Total Burden Hours |

Average Hourly Wage |

Total Annual Cost |

Partner |

60 |

1 |

.33 |

19.80 |

$ 50.57 |

$ 1,001.29 |

Consumer |

400 |

1 |

.33 |

132.00 |

$ 32.29 |

$ 4,262.28 |

Total Annual Estimate |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

151.80 |

n/a |

$ 5,263.57 |

A.13. Estimates of Other Total Annual Cost Burden to Respondents and Record Keepers

As both surveys are being conducted online, there are no additional costs anticipated.

A.14. Annualized Cost to the Federal Government

The estimated annualized cost to the federal government is $87,714. Again, this also serves as an estimate of the total burden, as all data will be collected within the span of one year. This includes costs of developing surveys and survey protocols ($3,750 for consumer and $3,750 for partner); vendor costs (programming, incentives, implementing, and data file preparation) for the consumer survey ($44,614); programming ($2,500), incentives ($2,100), implementing ($10,000), and data file preparation ($1,000) for the partner survey; and data analysis and report preparation ($10,000 for consumer and $10,000 for partner).

A.15. Explanation for Program Changes or Adjustments

RAND previously conducted an evaluation of C2C using a mixed-methods approach that consisted of existing data, an organization survey, a consumer survey, and case studies. The research activities proposed are a subset of, and similar to, the previously approved activities; however, as can be seen in Exhibit 5, the proposed activities are smaller in scope. The previously approved activities included two case studies (semi-structured interview and focus group), while the activities proposed only consist of the partner and consumer surveys. Also, a smaller number of survey participants are proposed for the partner (600 vs. 60) and consumer (2800 vs. 400) surveys. The average burden is 20 minutes for all surveys. Following from the proposed activities representing a smaller number of surveys and the same burden hours per survey, survey costs were much higher for the prior partner ($12,117.60 vs. $1001.29) and consumer ($35,610 vs. $4,262.28) surveys.

Large survey samples were used for these prior survey efforts in service of producing reliable estimates of consumer and partner use of C2C materials in the US, while the present effort is more narrowly focused on examining differences between those who do and do not use C2C materials in the top 12 geographic areas where there is a high saturation of C2C materials. We are also interested in comparing the health impacts on those exposed and not exposed to C2C materials. For both partner and consumer surveys, we will compare users of C2C materials with non-users in the top 12 geographic areas. In doing so, we aim to ascertain the facilitators for acquiring health insurance coverage and using it to access preventive health care, as well as to assess barriers and unmet needs of consumers and partners who serve those consumers. As such, the changes to the Partner Survey reflect (1) surveying those not using C2C materials; (2) getting additional information on organizations; and (3) changes to items to reflect current C2C efforts.

The changes to the Consumer Survey reflect (1) additional relevant items available in the Ipsos KnowledgePanel; (2) changes due to also interviewing people with marketplace plans; (3) measures of additional relevant constructs and refinement of prior measures; and (4) changes to items to reflect current C2C efforts. Only the changes to the previously approved surveys are highlighted in Appendix E.

The present evaluation is best seen as a complement to, rather than a duplication of, existing information. Moreover, these data collection efforts will provide CMS with comprehensive, upto-date information not available from any other source that will be useful for helping CMS better reach its target consumers and help consumers get connected with the healthcare system.

The prior and proposed consumer survey would both use the Ipsos KnowledgePanel to more easily acquire research participants; however, the partner survey would be programmed and fielded by the Ketchum team using the Qualtrics survey platform, instead of using a vendor to perform this survey with only 60 organizational partners.

Exhibit 5. |

Crosswalk between Previously Approved and Requested Burden |

|

|||||

Data collection |

# of Respondents |

# Responses/ Respondent |

Avg. Burden Hours/ Response |

Total Burden Hours |

Avg. Hourly Wage |

Total Annual Cost |

|

Prior Partner Survey |

600 |

1 |

.33 |

198 |

$61.20 |

$12,117.60 |

|

Prior Consumer Survey |

2800 |

1 |

.33 |

924 |

$38.54 |

$35,610.96 |

|

Prior Case Study: Semi-Structured |

24 |

1 |

.75 |

18 |

$30.60 |

$550.80 |

|

Prior Case Study: Focus Group |

36 |

1 |

1.00 |

36 |

$19.27 |

$693.72 |

|

Prior Total |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

1176 |

- |

$48,973.08 |

|

Current Partner Survey |

60 |

1 |

.33 |

20 |

$50.57 |

$1,001.29 |

|

Current Consumer Survey |

400 |

1 |

.33 |

132 |

$32.29 |

$4,262.28 |

|

Current Total |

n/a n/a n/a 152 |

$5,263.57 |

|||||

A.16. Plans for Tabulation and Publication and Project Time Schedule

A.16.1. Analysis Plan

The proposed analysis plan consists of a series of steps to answer the study’s research questions previously described. Generally, the analysis will examine (a) why consumers and partners are or are not using C2C materials and (b) the effects of the C2C program on short-, intermediate-, and long-term outcomes. Data will be collected through the two online surveys previously described.

The first step in our analysis plan for both surveys will be to assure the quality of the data collected. While we know there will not be out-of-range survey responses, the data still must be examined for (a) outliers and extreme responses; (b) removal of respondents that were clearly inattentive (e.g., extremely short completion times, straight-line responding); (c) representativeness of the underlying target populations; and (d) related to the prior concern, potential biases in our analyses due to self-selection into the study sample. Outliers and extreme responses will be examined through simple descriptive statistics and a graphical analysis of variable distributions. Variables with extreme responses (e.g., responses beyond the third standard deviation) will be considered as candidates for Winsorization or other transformation techniques.

Second, we will examine whether the distributional characteristics of the samples obtained differ from the underlying target populations. The characteristics examined will be participant background characteristics for consumers (e.g., race, ethnicity, income) and organizational characteristics for partners (e.g., size and type of organization). Simple chi-square goodness of fit tests will be used to examine departures from distributional expectations based on what we know about the populations. These population parameters will be obtained from American Community Survey five-year population estimates for the consumer survey and from characteristics of CMS material-ordering organizations for the partner survey. If there is evidence of substantial departures from expectations, we will consider survey non-response weights as a potential ameliorative method in our analyses. Finally, we will examine whether other potential confounders serve as a better alternative explanation for differences between those exposed and not exposed to C2C materials. This analysis will use a Heckman (1976) selectivity model by regressing exposure to C2C material status on background or organization characteristics, using a probit regression model. If there is evidence of selectivity biases operating, an inverse Mills’ ratio will be produced and entered as an ameliorative correction for selectivity in all inferential analyses.

The second step in our analysis plan involves constructing the scales and variables needed for analysis. Many of the measures used represent validated scales (e.g., Health Literacy being measured with the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems). We will explore the psychometric properties of these validated scales by calculating Cronbach’s alpha for these measures, where we would expect alpha to be acceptable (i.e., .70 or greater). Scale scores will be calculated for these measures by taking the mean of measured items. Additional nominal and dichotomous measures will be created as appropriate for analyses.

The final step in our plan is conducting descriptive and inferential analyses to answer our research questions. There are three primary analysis types that will be used, described below.

Research questions inquiring descriptively about exposure to health care information materials (e.g., what materials exposed to) and general reactions to C2C materials (e.g., satisfaction with materials) will involve descriptive statistics, such as percentages and means. Confidence intervals (95%) will also be calculated for estimates to assess our certainty surrounding the estimates and the distribution of variables. These descriptive analyses typically involve survey items asked based on exposure to C2C materials. For instance, descriptive information on satisfaction with C2C materials would be reported for only those exposed to C2C, and other health care information sources used would be reported for only those not exposed to C2C.

Research questions inquiring about differences in the process of exposure to C2C materials or differences in outcomes as a result of C2C exposure will use different analysis methods for the consumer and partner data, due to the small size of the partner sample precluding the use of statistical significance testing. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d and odds ratios) will also be calculated for all comparisons, which gives perspective on the magnitude of the difference, independent of sample size. A description of the specific methods to be used follows.

Comparisons in the consumer survey data will be conducted using independent groups t-tests for continuous outcomes and chi-square tests for independence for dichotomous outcomes. Supplemental tests to rule out alternative explanations and exploratory examinations of the relationship between the process of exposure and outcomes will use ordinary least squares regression for continuous outcomes and logistic regression for dichotomous outcomes.

Comparisons will be made in the partner data by examining whether there is overlap in the 95% confidence intervals.

One long-term outcome to be examined pertains to whether there are differences in how individuals experience health care as a function of exposure to C2C materials and race/ethnicity (LT15 and LT17). This analysis will be conducted using a race/ethnicity x exposure ANOVA, where the interaction test will indicate whether there are differential effects of exposure by race/ethnicity.

A.16.2. Time Schedule and Publications

Exhibit 6 presents the projected timeline for project completion after clearance of this project. Our timeline assumes a clearance date of 8/31/2022, so specific dates may shift to some extent depending on when clearance is received. The proposed timeline consists of a six-month period for project completion, where all activities will occur prior to the second relaunch of C2C occurring in the Spring of 2023. The initial relaunch (primarily print materials) of C2C will occur by August of 2022 and the secondary relaunch (primarily digital materials) will occur in late spring of 2023. Thus, final reporting from these data does have the potential to impact final C2C relaunch decisions.

The first month of the six-month timeline will involve obtaining current sampling frames of (a) those partner organizations that requested CMS materials and (b) KnowledgePanel members who are consumers of Medicaid, Medicare or Marketplace plan services. The Ketchum team will be responsible for compiling the partner sample frame, and Ipsos will handle compiling the KnowledgePanel sampling frame. The first three months of the six-month time period will be allotted for fielding the surveys, where the Ketchum team will be responsible for the fielding of the partner survey, and Ipsos will be responsible for fielding the consumer survey. The final two months of the timeline will involve a month for data analysis and a month for data reporting. The final report produced from this evaluation will contain an executive summary that briefly summarizes the findings of the evaluation and a full report containing more details on the background of the study, the methods used for the study, the results of analyses, and conclusions and recommendations that can be drawn from the analyses.

Exhibit 6. |

Projected Timeline for Consumer and Partner Survey Implementation, Analysis, and Reporting

Task |

6 Months to Complete |

Dates |

Obtaining Consumer & Partner Sampling Frames |

1 |

09/01/22–09/30/22 |

Data Collection Activities |

3 |

10/01/22–12/31/22 |

Data Analysis |

1 |

01/01/23–01/31/23 |

Prepare and Submit Report* |

1 |

02/01/23–02/28/23 |

*Relaunch is currently slated to occur in late Spring of 2023 (after report is produced).

A.17. Display of OMB Expiration Date

All surveys will display the OMB number and expiration date on the first web page.

A.18. Exceptions to Certification for Paperwork Reduction Act Submissions

This data collection effort requires no exceptions.

References

Ali, N.M., Combs, R.M., Muvuka, B., & Ayangeakaa, S.D. (2018). Addressing Health Insurance Literacy Gaps in an Urban African American Population: A Qualitative Study. J Community Health 43(6): 1208-1216. DOI: 10.1007/s10900-018-0541-x.

Brown, V., Russell, M., Ginter, A., Braun, B., Little, L., Pippidis, M., & McCoy, T. (2016). Smart Choice Health Insurance(c): A New, Interdisciplinary Program to Enhance Health Insurance Literacy. Health Promot Pract 17(2): 209-16. DOI:

10.1177/1524839915620393.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020a). Employer costs for employer compensations – June 2020.

Downloaded 11/2/2020 from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/ecec.pdf.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020b). Usual weekly earnings of wage and salary workers second quarter 2020 (Table 5. Quartiles and selected deciles of usual weekly earnings of fulltime wage and salary workers by selected characteristics, 2nd quarter 2020 averages, not seasonally adjusted). Downloaded 11/2/2020 from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/wkyeng_07172020.htm.

Champlin, S. & James, J. (2017). Breaking Health Insurance Knowledge Barriers Through Games: Pilot Test of Health Care America. JMIR Serious Games 5(4): e22. DOI:

10.2196/games.7818.

Chandrasekar, E., Kim, K.E., Song, S., Paintal, R., Quinn, M.T., & Vallina, H. (2016). First Year Open Enrollment Findings: Health Insurance Coverage for Asian Americans and the Role of Navigators. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 3(3): 537-45. DOI: 10.1007/s40615-0150172-1.

Chen, J.Y., Swonger, S., Kominski, G., Liu, H., Lee, J.E., & Diamant, A. (2009). Costeffectiveness of insuring the uninsured: The case of Korean American children. Medical Decision Making 29(1): 51-60. DOI: 10.1177/0272989X08322011.

Cousineau, M.R., Stevens, G.D., & Farias, A. (2011). Measuring the impact of outreach and enrollment strategies for public health insurance in California. Health Serv Res 46(1 Pt 2): 319-35. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01202.x.

Crocetti, M., Ghazarian, S.R., Myles, D., Ogbuoji, O., & Cheng, T.L. (2012). Characteristics of children eligible for public health insurance but uninsured: data from the 2007 National Survey of Children's Health. Matern Child Health J 16 Suppl 1: S61-9. DOI:

10.1007/s10995-012-0995-x.

Edward, J., Morris, S., Mataoui, F., Granberry, P., Williams, M.V., & Torres, I. (2018). The impact of health and health insurance literacy on access to care for Hispanic/Latino communities. Public Health Nurs 35(3): 176-183. DOI: 10.1111/phn.12385.

Flores, G., Lin, H., Walker, C., Lee, M., Currie, J., Allgeyer, R., Fierro, M., Henry, M., Portillo, A., & Massey, K. (2016). Parent Mentors and Insuring Uninsured Children: A Randmoized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics 137(4): e20153519.

Furl, R., Watanabe-Galloway, S., Lyden, E., & Swindells, S. (2018). Determinants of facilitated health insurance enrollment for patients with HIV disease, and impact of insurance enrollment on targeted health outcomes. BMC Infect Dis 18(1): 132. DOI:

10.1186/s12879-018-3035-7.

Gany, F., Bari, S., Gill, P., Loeb, R., & Leng, J. (2015). Step On It! Impact of a Workplace New York City Taxi Driver Health Intervention to Increase Necessary Health Care Access. Am J Public Health. 105(4): 786-792. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302122.

Giovannelli, J. & Curran, E. (2016). Factors Affecting Health Insurance Enrollment Through the State Marketplaces: Observations on the ACA’s Third Open Enrollment Period. The Commonwealth Fund 19: 1-11.

Han, J. (2018). Perceived Value of Health Insurance and Enrollment Decision among Low-

Income Population. INNOVATIONS in pharmacy 9(2). DOI: 10.24926/iip.v9i2.988.

Heckman, James J. (1976). The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection and limited dependent variables and a simple estimator for such models. Annals of Economic and Social Measurement, 5, 475-492.

Hearst, A.A., Ramirez, J.M., & Gany, F.M. (2010). Barriers and facilitators to public health insurance enrollment in newly arrived immigrant adolescents and young adults in New York State. Journal of immigrant and minority health 12(4): 580-585.

Hoerl, M., Wuppermann, A., Barcellos, S.H., Bauhoff, S., Winter, J.K., & Carman, K.G. (2017). Knowledge as a Predictor of Insurance Coverage Under the Affordable Care Act. Med Care 55(4): 428-435. DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000671.

Hom, J.K., Stillson, C., Rosin, R., Cahill, R., Kruger, E., & Grande, D. (2017). Effect of Outreach Messages on Medicaid Enrollment. Am J Public Health 107(S1): S71-S73. DOI:

10.2105/AJPH.2017.303845.

Huhman, M., Quick, B.L., & Payne, L. (2016). Community College Students' Health Insurance Enrollment, Maintenance, and Talking With Parents Intentions: An Application of the Reasoned Action Approach. J Health Commun 21(5): 487-95. DOI:

10.1080/10810730.2015.1103327.

Ketterman Jr., J., Pippidis, M., Brown, V., & Braun, B. (2018). Teaching Consumers to Understand and Estimate Health Care Costs. The Forum for Family and Consumer Issues 22(1): 1-8.

Lee, J., Ding, R., Zeger, S.L., McDermott, A., Habteh-Yimer, G., Chin, M., Balder, R.S., & McCarthy, M.L. (2015). Impact of subsidized health insurance coverage on emergency department utilization by low-income adults in Massachusetts. Medical Care 53(1): 3844.

Leininger, L.J. & Burns, M.E. (2011). Why Are Low-Income Teens More Likely to Lack Health Insurance than their Younger Peers? Inquiry 48: 123–137.

Levy, H. & Janke, A. (2016). Health Literacy and Access to Care. J Health Commun 21 Suppl 1: 43-50. DOI: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1131776.

McLeod, A., Kemp, A., Hill-Mischel, J., & Cohen, A. (2013). Helping individuals obtain health coverage under the ACA. Healthcare Financial Management 67(10): 56-61.

McManus, K.A.A., Killelea, A., Honeycutt, E., An, Z., & Keim-Malpass, J. (2020). Assisters

Succeed in Insurance Navigation for People Living with HIV and People at Increased Risk of HIV in a Complex Coverage Landscape. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. DOI:

10.1089/AID.2020.0013.

Norbeck, A.J. (2018). Health Insurance Literacy Impacts on Enrollment and Satisfaction with Health Insurance, in College of Health Sciences. Walden University.

Patel, M.R., Israel, B.A., Song, P.X.K., Hao, W., TerHaar, L., Tariq, M., & Lichtenstein, R.

(2019). Insuring Good Health: Outcomes and Acceptability of a Participatory Health Insurance Literacy Intervention in Diverse Urban Communities. Health Educ Behav 46(3): 494-505. DOI: 10.1177/1090198119831060.

Politi, M.C., Kuzemchak, M.D., Liu, J., Barker, A.R., Peters, E., Ubel, P.A., Kaphingst, K.A., McBride, T., Kreuter, M.W., Shacham, E., & Philpott, S.E. (2016b). Show Me My Health Plans: Using a Decision Aid to Improve Decisions in the Federal Health Insurance Marketplace. MDM Policy Pract 1. DOI: 10.1177/2381468316679998.

Politi, M.C., Grant, R.L., George, N.P., Barker, A.R., James, A.S., Kuroki, L.M., McBride, T.D., Liu, J., & Goodwin, C.M. (2020). Improving Cancer Patients' Insurance Choices (I Can PIC): A Randomized Trial of a Personalized Health Insurance Decision Aid. Oncologist 25(7): 609-619. DOI: 10.1634/theoncologist. 2019-0703.

Ray, J.A., Rosnick-Slyker, A., Bryant, K.M., Detman, L.A., Price, M.J., Kirk, B., & Brunson,

A.E. (2017). Developing a Framework to Promote Children's Health Insurance

Enrollment in Florida. Health Promot Pract 18(6): 814-821. DOI:

10.1177/1524839917699552.

Shafer, P.R., Fowler, E.F., Baum, L., & Gollust, S.E. (2018). Television Advertising and Health Insurance Marketplace Consumer Engagement in Kentucky: A Natural Experiment. J Med Internet Res 20(10): e10872. DOI: 10.2196/10872.

Singer, E. & Ye, C. (2013), The use and effects of incentives in surveys, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 645(1): 112-141.

Tipirneni, R., Solway, E., Malani, P., Luster, J., Kullgren, J.T., Kirch, M., Singer, D., & Scherer, A.M. (2020). Health Insurance Affordability Concerns and Health Care Avoidance Among US Adults Approaching Retirement. JAMA Netw Open 3(2): e1920647. DOI:

10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20647.

Valente, T., Coronges, K., Stevens, G., & Cousineau, M. (2008). Collaboration and Competition in a Children’s Health Initiative Coalition: A Network Analysis. Evaluation and Program Planning, 31(4): 392-402. DOI: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.06.002

Wright, B.J., Garcia-Alexander, G., Weller, M.A., & Baicker, K. (2017). Low-Cost Behavioral Nudges Increase Medicaid Take-Up Among Eligible Residents Of Oregon. Health Aff 36(5): 838-845. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1325.

Yarger, J., Daniel, S., Biggs, M.A., Malvin, J., & Brindis, C.D. (2017). The Role of Publicly Funded Family Planning Sites In Health Insurance Enrollment. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 49(2): 103-109. DOI: 10.1363/psrh.12026.

Young, J. M., O'Halloran, A. McAulay, C., Pirotta, M., Forsdike, K., Stacey, I., & Currow, D. (2015), Unconditional and conditional incentives differentially improved general practitioners' participation in an online survey: randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 68(6), 693-697.

List of Appendices Under Separate Cover

Appendix A |

Partner survey and consent form |

Appendix B |

Consumer survey and consent form |

Appendix C |

Recruitment script for partner survey |

Appendix D |

Letter of support from CMS to be included with recruitment scripts for partner survey |

Appendix E |

Listing of Survey Changes |

1 Jacksonville and Miami were tied for 12th place.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2023-08-02 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy