Appendix D - Tests Influencing Design of NTPS

Appendix D NTPS 2023-24 - Tests Influencing the Design of NTPS v43 4.23.docx

National Teacher and Principal Survey of 2023-2024 (NTPS 2023-24) Data Collection

Appendix D - Tests Influencing Design of NTPS

OMB: 1850-0598

National Teacher and Principal Survey

of 2023-2024 (NTPS 2023-24)

OMB# 1850-0598 v.43

Appendix D

Tests Influencing the Design of NTPS 2023-24

National Center for Education Statistics

U.S. Department of Education

January 2023

revised April 2023

This document describes the tests that have most influenced the NTPS design, beginning with the 2014-15 NTPS Pilot Test and continuing through 2022.

2014-15 NTPS Pilot Test

Five experiments designed to optimize the design of the 2015-16 NTPS were conducted as part of the 2014-15 NTPS Pilot Test: 1) the Questionnaire Mode Experiment, 2) the Teacher Listing Form (TLF) Email Experiment, 3) the Invitation Mode Experiment, 4) the Teacher Questionnaire Instruction Experiment, and 5) the Vendor Analysis. Each of these experiments is briefly described below, along with its results and implications for successor NTPS data collections.

Questionnaire Mode Experiment. This experiment was designed to determine whether paper questionnaires or Internet survey instruments (i.e., mail‐only versus internet sequential modes) constituted the most effective mode of collecting the TLF, School Questionnaire, and Principal Questionnaire. For all three-survey instruments, the schools assigned to the paper mode had higher response rates than the schools assigned to the internet mode.

Some known issues with data collection could have impacted these response rates. First, the pilot test did not use survey coordinators, a method shown to boost response rates in SASS. Second, there were problems related to the contact materials for the internet treatment groups. As a result of this experiment, NTPS 2015-16 was primarily paper based; used improved contact materials and login procedures; and included an experimental sample of 1,000 schools, outside the main study, which were offered Internet survey at the onset of data collection and which followed standard production NTPS procedures, including the establishment of a survey coordinator.

Teacher Listing Form (TLF) Email Experiment. This experiment was designed to assess the feasibility of collecting teacher email addresses on the TLF and the quality of those collected. The pilot test design included a split-panel experiment, with half of sampled schools randomly assigned to receive a TLF that included a request for teachers’ email addresses and the other half to receive a TLF that did not request email addresses. At the end of data collection, response rates were comparable between the schools that received the TLF with the email address field and the schools that received the TLF without the email address field. As a result of this experiment and the Invitation Mode Experiment described below, NCES used the TLF with the email address field in NTPS 2015-16 and later collections.

Invitation Mode Experiment. The purpose of this experiment was to identify which of three methods of inviting teachers to complete the Teacher Questionnaire yielded the best response rates. Schools were randomly assigned to the following invitation modes: 1) both email and mailed paper invitation letters to complete the internet instrument (treatment A), 2) a mailed paper invitation letter to complete the internet instrument only (treatment B), and 3) a mailed package that included a letter and paper questionnaire (treatment C). The results of the experiment indicated that a strategy using a combination of email and paper invitations (treatment A) is best for inviting teachers to complete the internet questionnaire. The response rate for treatment group A was comparable to that of treatment group C that received only mailed paper materials. As a result of this experiment, teachers sampled for NTPS 2015-16 for whom we had a valid email address were sent both email and paper invitations as the initial request to fill out the Teacher Questionnaire. Teachers without valid email addresses were sent their initial invitation as part of a mailed package that included a paper copy of the survey. For the 2017-18 NTPS and later collections, NCES pushed for web response by both mailed and emailed correspondence, switching to a paper questionnaire at the third mailing.

Teacher Questionnaire Instruction Experiment. This experiment was designed to determine (1) whether including instructions in the NTPS questionnaire impacts response rates for questionnaire items and data quality, and (2) whether the position, format, and presence or absence of a preface in the instruction impacts response rates for questionnaire items. Production questions and instructions, which were the product of production cognitive interviewing, were selected from the 2014-15 NTPS. In addition, a second set of questions and instructions were intentionally created to counter teachers’ natural conceptions of terms. Both sets of questions were compared to a control group with no instructions. Utilizing a factorial experiment design, three factors varied that were predicted to alter the effectiveness of instructions: their location, format, and the presence or absence of a preface. The NTPS questions with instructions, which were the result of production cognitive interviews, increased the length of the questionnaire with no measurable improvement in data quality compared to control questions with no instructions, whereas the experimental questions with instructions meant to counter teachers’ natural conceptions of terms improved data quality by changing responses in the expected direction. Due to the lack of differences for NTPS production questions, no major changes were made to instruction position, format, or introduction in subsequent 2017-18 NTPS.

Vendor Analysis. The purpose of this experiment was to evaluate both the feasibility of collecting teacher lists from a vendor and the reliability of the purchased information to see whether it could be used to supplement or replace school-collected TLFs. NCES purchased teacher lists from a vendor for schools sampled for the 2014-15 NTPS pilot test. The vendor teacher lists were compared with information collected from the TLFs. The results suggested that the vendor list information was comprehensive and reliable at a relatively low cost. NCES used vendor lists to sample teachers from a subset of schools that did not respond to the TLF in NTPS 2015-16 and later collections.

NTPS 2015-16 Full-Scale Collection

Schools and Principals Internet Test. The 2015-16 NTPS included an Internet experiment for schools and principals, which was designed to test the efficacy of offering an internet response option as the initial mode of data collection, as done previously in the Questionnaire Mode Experiment included in the 2014-15 NTPS Pilot Study, described earlier.

Key differences exist between the 2014-15 and 2015-16 NTPS internet experiments, with the most notable being that the 2015-16 experiment included the use of a survey coordinator at the school, and improved respondent contact materials and mailout packaging. In the 2015-16 NTPS, an independent sample of 1,000 public schools was selected for this experiment, which invited schools and principals to complete the NTPS school-level questionnaires using the internet at the first and second contacts by mail. A clerical operation prior to data collection obtained email addresses for sampled principals assigned to the internet treatment. Principals were sent emails as an initial mode of invitation to complete the NTPS questionnaires as well as reminder emails; the timing of these emails was a few days following the mailings.

Paper questionnaires were offered at the third and final mailout. Data collection for the internet treatment concluded after the third mailing, so the schools in the experimental treatment did not receive a fourth mailing and were not included in the telephone follow-up or field follow-up operations. When comparing the response rates for all three survey instruments at the end of the reminder telephone operation – the most reasonable time to make the comparison – and removing the cases that would have qualified for the early field operation, the response rates for schools assigned to the internet treatment are five to six percentage points higher than those for the paper treatment. Therefore, the initial mailout in later NTPS collections will invite respondents to complete online questionnaires for all questionnaire types. Paper questionnaires will be introduced during the third mailing. Principal email addresses (purchased from the vendor) and school-based survey coordinator email addresses (collected at the time the survey coordinator is established) will be utilized during data collection. Invitations to complete the principal and school questionnaires via the Internet response option will be sent to the principal and school-based survey coordinator by email in conjunction with the various mailings.

Contact Time Tailoring Experiment. This test was designed to determine the optimal contact time for teachers. During the telephone nonresponse follow-up operation, interviewers contacted nonresponding principals and teachers to remind them to complete their questionnaire. Teachers tend to be difficult to reach during the school day due to their teaching schedules. NCES staff hypothesized that teachers may be easier to reach by phone in the late afternoon, when school had been dismissed. To test the accuracy of this theory, an experiment was embedded in the telephone nonresponse follow-up operation. A portion of the nonresponse follow-up (NRFU) teacher workload received an experimental treatment, where they were intended to be contacted only in the afternoon between 2:00 p.m. and 5:00 p.m. (respondent time). The remainder of the NRFU teacher universe functioned as the control group. These teachers were intended to receive contacts throughout the school day, per typical telephone follow-up procedures. The research questions this test was designed to answer were as follows:

Are afternoons more productive for calling teachers?

If not afternoons, are there more productive times than others for calling teachers?

Do productive contact times for teachers hold globally, or do different types of schools have different productive call time frames?

Can we use school-level frame information (e.g. urbanicity, school size, grade level) to help tailor call times in future rounds of data collection?

If the calls are being made at “productive times,” are fewer call attempts required to successfully make contact with the teacher?

If the calls are being made at “productive times,” are fewer call attempts and total contacts required to obtain a completed interview?

Operational challenges in conducting the call time experiment were encountered. Early in the telephone nonresponse follow-up operation, telephone interviewers reported that school staff members were complaining about receiving multiple calls to reach the sampled teachers. School staff members indicated that they would prefer to know the names of the teachers the interviewer needed to reach so that they could assist the interviewer in as few phone calls as possible. As a result, the results of the experiment could not be evaluated as intended. Instead of comparing the success of reaching the sampled teachers by their treatment group, staff compared the success rates of the actual call times. Call times were categorized as ‘early’ (before 2:00 p.m.) or ‘late’ (between 2:00 p.m. and 5:00 p.m.). There was not a noticeable difference in the success rates of contacting teachers by call time. Additional analyses on the data may be conducted to help inform future administrations of NTPS.

NTPS 2017-18 Full-Scale Collection

To address declining response rates among teachers in NTPS 2015-16, NCES tested the use of incentives to increase response in NTPS 2017-18. In addition, NTPS 2017-18 included a private school test that was designed to (a) provide accurate estimates for teachers and principals in private schools in the U.S. and (b) to examine the effects of strategies to improve response in this population.

Testing the use of teacher incentives. The 2017-18 NTPS included an incentive experiment designed to examine the effectiveness of offering teachers a prepaid monetary incentive to boost overall teacher response. Teachers were incentivized during the first 12 waves of teacher sampling (“phase one incentive experiment”), then a combination of teachers and/or school coordinators or principals were incentivized during the remaining waves (“phase two incentive experiment”). During the first 12 waves of the teacher sampling, teachers were only sampled from returned TLFs. However, beginning in wave 13 for schools, teachers could be sampled from returned TLFs, vendor lists, or internet look-ups. This change in the teacher sampling procedures provided a natural breakpoint between the two phases of the experiment and allowed us to target the most challenging cases with an additional incentive for the school coordinator or principal.

The results of phase one of the incentive experiment indicated that the teacher incentive led to significant increases in the response rate for both public and private school teachers. As shown in table 10, below, there was roughly a 4% increase in response for both the public and private school teachers that received the incentive, compared to the teachers that did not receive the incentive.

Table 1. Teacher response rates by incentive treatment and school type for the phase 1 incentive experiment: NTPS 2017-18

-

Public Teacher

Private Teachers

Incentive

88.60%

87.50%

No Incentive

84.60%1

83.70%1

1 denotes a statistically significant difference from the incentive group at the α = .10 level

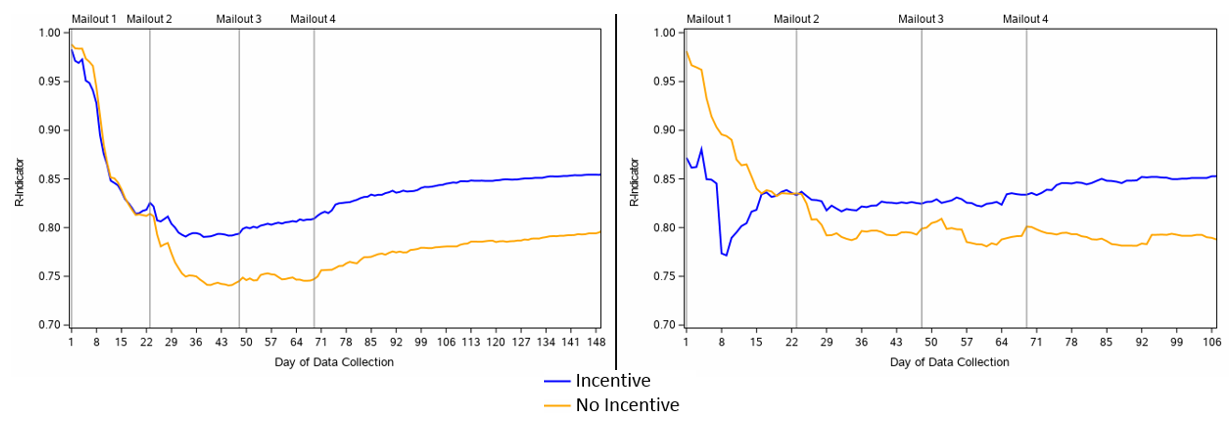

In addition, the average number of days to complete the questionnaire was significantly lower for public school teachers that received the incentive by 4.85 days. Finally, the incentive helped increase the overall sample balance for teachers in both public and private schools. Exhibit 2, below, depicts the full-sample R-indicator by day of data collection for public school teachers on the left and private school teachers on the right. As shown in the graphic, following the second mail-out, the group that received the incentive had a more balanced respondent population than the group that did not receive the incentive.

Exhibit 1. Full-sample R-indicator by day of data collection for public (left) and private (right) school teachers: NTPS 2017-18

The results of phase two of the incentive experiment indicated that the additive effect of the school coordinator incentive (in addition to the teacher incentive) was negligible for both public and private school teachers. As shown in the table 11 below, there were significant differences between the two groups that received the teacher incentive and the two groups that did not receive the teacher incentive. However, between the two groups that received the teacher incentive, the group that also received the school coordinator incentive did not have a significantly higher response rate.

Table 2. Teacher response rates by incentive treatment and school type for the phase 2 incentive experiment: NTPS 2017-18

-

Public Teacher

Private Teacher

Teacher, SC Incentives

77.40%

68.70%

Teacher Incentive Only

76.71%

69.00%

SC Incentive Only

72.97%1,2

62.30%1,2

No Incentives

73.73%1,2

68.00%3

1 denotes a statistically significant difference from the Teacher, SC Incentive group and the respective column’s group with α = .10 level

2 denotes a statistically significant difference from the Teacher Incentive Only group and the respective column’s group with α = .10 level

3 denotes a statistically significant difference from the SC Incentive Only group and the respective column’s group with α = .10 level

In addition, the average number of days to complete the teacher questionnaire was significantly lower for the treatment group that received both incentives when compared to the treatment groups that did not receive a teacher incentive (with or without the school coordinator incentive) for both public and private school teachers. Table 12 shows the average days to respond comparisons between the treatment groups.

Table 3. Average number of days for teachers to complete their teacher questionnaire by school type and incentive treatment for the phase 2 incentive experiment: NTPS 2017-18

-

Teacher,

SC Incentives

Teacher Incentive

Only

SC Incentive

Only

No Incentive

Public Teacher

36.86

37.57

41.081,2

42.051,2,3

Private Teacher

40.12

40.75

44.511

44.991

1 denotes a statistically significant difference from the Teacher, SC Incentive group and the value’s respective column group using Cox proportional hazard modeling with α = .10 level

2 denotes a statistically significant difference from Teacher Incentive only group and the value’s respective column group using Cox proportional hazard modeling with α = .10 level

3 denotes a statistically significant difference from SC Incentive only group and the value’s respective column group using Cox proportional hazard modeling with α = .10 level

Given these results, we planned to offer teachers an incentive for the NTPS 2020-21 and not offer a monetary incentive to school coordinators will not be offered for the NTPS 2020-21.

Testing the use of incentives as part of a contingency plan. NTPS 2017-18 experimented with offering an incentive to teachers if they belonged to a domain that was determined to be ‘at-risk’ of not meeting NCES reporting, or publishability, standards towards the end of data collection (by February 12, 2018). NCES monitored actual and expected response in each of the key domains on a weekly basis. The contingency plan was to be activated in the experimental group only if needed and, based on publishability reports, it was deemed needed and was activated. The control group was not eligible to receive the contingency incentive. While the plan was aimed at improving teacher response rates, because teachers within a school were likely to discuss the study, schools were selected based on meeting criteria of the domain at risk and all teachers within the school were subject to the same treatment (experimental or control). This approach was based on the assumption that if some teachers in the school received an incentive and others did not, it would negatively impact current and future response from that school. At the time the incentive was activated, some teachers at the school have already responded to NTPS – such teachers, if assigned to the contingency incentive treatment, were provided the incentive as a “thank you” for their participation. For all other teachers in the school, the same incentive was prepaid and not conditional on their response. Given that schools selected for the contingency plan incentive were based on the number of teachers in the at-risk domain, selection for this incentive was independent of the main NTPS incentive experiment. Consistent with the other NTPS 2017-18 procedures, the incentive amount varied between priority and non-priority schools. Teachers in selected non-priority schools received $10 with their third mail-out or thank-you letter, and teachers in selected priority schools received $20 with their third mail-out or thank-you letter.

The contingency plan results indicated that, overall, the contingency incentive significantly increased the response rate within the selected contingency incentive domains for public school teachers. For the cases that were open at the time of the 3rd mail-out and therefore received the contingency incentive, the response rate was 7% higher than for the group that did not receive the contingency incentive. Therefore, a contingency plan will also be included in the NTPS 2020-21 and will be executed as needed based on monitoring data collection status.

Table 4. Teacher response rates by treatment for the contingency plan incentive experiment: NTPS 2017-18

-

Contingency Incentive

No Contingency Incentive

Response Rate of Cases Still Open at the 3rd Mail-out

50.5%

43.2%1

Final Response Rate

74.8%

71.7%1

1 denotes a statistically significant difference from the contingency incentive group at the α = .10 level

Private School Test. In NTPS 2017-18, NCES conducted an embedded test with private schools both to determine whether sufficient response could be achieved to provide reliable estimates for private schools and to evaluate specific methods for improving response rates. The private schools selected for this test experienced data collection procedures that were generally similar to those used with the NTPS 2017-18 public school sample. Some procedures were adjusted to accommodate differences specific to this sector (e.g., religious holidays and schedules). Results indicate that the private school data collected during NTPS 2017-18 will yield publishable estimates; therefore, private schools will be included in the NTPS 2019-20 sample.

Within the private school test was a secondary test, where a tailored contact strategy was employed for a subsample of “priority schools”. A propensity score model was used to identify and segment priority schools. The highest priority schools for the collection are those with the lowest likelihood of response and the highest likelihood to contribute to bias. In order to assign schools into treatment groups, schools were matched into pairs with similar likelihood scores and then randomly assigned to groups (“priority” early contact schedule versus “non-priority” typical contact schedule). Because the priority school data collection plan was resource intensive and was not necessary for some schools (e.g., schools with a high likelihood of response), the tailored contact strategy was tested with 60 percent of the sample, based on the highest priority cases as identified by the propensity models. Once they were matched into pairs, half of the schools in the test group (30 percent of schools in the starting sample) were assigned to the treatment group (“priority”), and the other half of the schools (30 percent) were assigned to the comparison group (“non-priority”). The remaining 40 percent of the starting sample received the typical contact schedule for the non-priority schools.

Results from the tailored contact strategy test show that the tailored contact strategy (with data collection starting with in-person visits from Census Bureau FRs) was not effective for the private priority schools. While private schools with early in-person visits from FRs had higher response rates to the School and Principal questionnaires early in data collection, there was no difference by the end of the 2017-18 NTPS. These schools completed TLFs at higher rates than schools with non-priority treatment, however, teachers sampled from schools with priority treatment completed the Teacher Questionnaire at lower rates than teachers sampled from schools with non-priority treatment.

Coordinated special district operations. NCES conducts several school-based studies within the NCES legislative mandate to report on the condition of education including, among others, NTPS, the SSOCS, and the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). A critical step for data collection is to obtain approval from public school districts that require it before a study can be conducted with students, teachers, and/or staff within their jurisdiction. The number of such special contact districts is steadily increasing. This poses a barrier to successful data collection, because many districts and schools have complex and lengthy approval processes, reject all outside research, or only review applications for outside research once a year. This has contributed to lower response rates for non-mandatory NCES surveys. NCES continues to examine how different program areas, both within NCES and in other federal agencies, seek approval from PreK-12 public districts and schools in order to identify best practices and make recommendations for current and future operations, including the NTPS.

To reduce burden for the special contact districts and improve operational efficiency, NCES sought research approval simultaneously for NTPS 2017-18 and SSOCS 2018. Although NCES minimized overlap in the schools sampled for NTPS and SSOCS, most of the largest districts had at least one school selected for each of the surveys. All special contact districts with schools sampled for both NTPS and SSOCS received both research applications concurrently and were given the option to participate in NTPS only, SSOCS only, or both NTPS and SSOCS. The research request packets for the districts in both studies contained an additional letter introducing the studies and emphasizing that SSOCS and NTPS are working together to minimize the number of schools asked to participate in both studies. Some special districts found the dual application confusing, particularly districts with online application systems that do not allow for multiple applications to be linked. In addition, the samples for NTPS and SSOCS are drawn at different times, and coordinating applications delayed when a list of schools sampled for both studies could be shared with a district. As a result, future overlapping NTPS and SSOCS studies will likely send separate application packages to special districts for NTPS and SSOCS if these studies are fielded in the same school year, though the staff that follow up with special districts about the status of these applications will be able to direct districts to the appropriate contact person if there are questions about other NCES studies.

For NTPS 2020-21, NCES tested several collection strategies, all aimed at increasing survey response. Each of these experiments is briefly described below, along with its results and implications for successor NTPS data collections.

Three experiments aimed at increasing school-level response rates were included in the 2020-21 NTPS, namely (1) testing new package contents, (2) testing prepopulated TLFs, and (3) testing various question layouts on the school questionnaire internet instruments. Each of these experiments is described briefly below.

Testing new mailed package contents in school mailings. In an effort to both increase response rates and lower mailing costs, NTPS 2020-21 explored whether new types of mailed materials will yield higher response rates. Specifically, two versions of letters to principals and school coordinators were tested to determine whether modifying contact materials to emphasize the values of the study and the benefits of participating can increase response rates compared to letters similar to those used in past NTPS administrations. There were two versions of each letter (traditional and modified) for the screener and initial mailings, as follows:

Screener letter;

cover letter to principal and cover letter to survey coordinator (initial mailout); and

cover letter to principal/survey coordinator (second mailout).

As such, this experiment impacted the screener mailout, the initial school mailout, and the second school mailout.

Approximately 4,800 public schools received the traditional letters and approximately 4,800 public schools received the modified letter. Similarly for private schools, approximately 1,348 schools received the traditional letter and 1,348 schools received the modified letter.

Preliminary results show that, for the screener letter, there were no significant differences in the final unweighted or weighted Screener completion rates between the schools that received the modified letters versus the schools that received the traditional letters. These results held for both public and private schools.

For the initial and second mailouts, there were no significant differences in the final response rates for the school questionnaire, principal questionnaire, or TLF between the schools that received the modified letters versus the schools that received the traditional letters, and this result held true for both public and private schools. However, at the time of the third mailout, the public schools that received the modified letters had a significantly lower school questionnaire response rate than those that received the traditional letter.

Testing prepopulated Teacher Listing Forms (TLFs). The NTPS 2020-21 offered prepopulated TLFs to schools for verification via the NTPS Respondent Portal TLF application, where vendor-provided teacher data was loaded into the NTPS portal. The use of prepopulated TLFs via the NTPS Respondent Portal was offered to respondents in a split-panel manner in order to assess the quality and burden tradeoffs of offering schools a prepopulated TLF. The assumption behind this TLF collection strategy is that validating a prepopulated TLF is less burdensome than completing a blank TLF, but that the data received on the blank TLF may be more accurate based on feedback from NTPS 2017-18 operations; however, this has not been validated quantitatively.

A subset of the NTPS 2020-21 schools with acceptable vendor data were offered their prepopulated TLF via the portal, while the remaining schools with acceptable vendor data were only offered the traditional Excel upload and manual entry options. Approximately 15% of the public schools with acceptable vendor data were offered the blank TLFs, and the remaining schools received the prepopulated TLFs. Similarly, 20% of the private schools with acceptable vendor data were offered the blank TLFs and the remaining schools received the prepopulated TLFs. If schools randomly assigned to receive a blank TLF have not completed that form after multiple contact attempts, teachers from those schools will be sampled from vendor data and given the opportunity to complete the Teacher Questionnaire.

Preliminary results show that the schools that received the pre-populated TLF returned the TLF at a significantly higher rate than the schools that received the blank TLF. Additionally, schools returned the pre-populated TLF in significantly less time than the schools that returned the blank TLF, and there is no difference in the percentage of sampled teachers who return a Teacher Questionnaire at schools that completed a pre-populated or blank TLF. Therefore, for NTPS 2023-24, TLFs pre-populated with teacher data from vendor lists will be offered to respondents whenever possible.

A validation study was originally planned for NTPS 2020-21 during the spring of 2021 whose purpose was to verify the accuracy of TLF data and debrief schools about their experience with the TLF related task (generally) and NTPS portal instrument, as well as any discrepancy between the two teacher lists (if applicable). It was to be conducted by staff in the Census Bureau’s contact centers for a subsample of schools – approximately 100 schools from each TLF submission method. The intent was to be more of an intellectual exercise aimed at confirming that the expectation that the prepopulated TLF reduces burden and improves response rate is accurate. This study was cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic and its impact on schools, but should be considered for inclusion in future administrations of the NTPS.

Testing various question layouts on the school questionnaire internet instruments (4S). The NTPS 2020-21 school questionnaires included several different versions of items or groups of related items, with the layout of the items varying across the treatment groups. The goal of the experiment is to compare the response distributions of the different versions of the item and ultimately identify the best question layout for future cycles of NTPS.

Vacancies Item (2-4). Item 2-4 on the public and private school questionnaires asks the respondent how easy or difficult it was to fill vacancies for 12 positions in their school. The response options include the following: easy, somewhat difficult, very difficult, could not fill vacancy, no vacancy this school year, and position not offered in the school.

A filter question was included in past administrations, first asking respondents whether their school had any teaching vacancies in any field. While removal of this filter question would allow researchers to determine whether a school did not have a vacancy in a given field because the position was not offered or because there was simply no vacancy in any field, an important distinction for estimating the percentage of schools with vacancies in a given field, it is possible that fewer vacancies would be reported without the presence of a filter question, that is, respondents may mistakenly omit vacancies when a list of teaching fields is not seen. The presentation with the filter question is the experimental treatment.

None Boxes. In the 2017-18 NTPS, “None” boxes were included in web instruments and paper questionnaire instruments for items that asked the respondent to provide a count (e.g., number of minutes spent on various subjects/activities). The “None” boxes were replaced in the 2020-21 NTPS School Questionnaire (SQ) internet instrument with an item-specific instruction to ”Write ‘0’ if…” for a subsample of respondents.

This split-panel experiment for the SQ instrument assessed the impact of the absence of “None” boxes on data quality. This experiment required two instrument versions for the following survey items:

Item 2-1, Teacher counts: One version with None boxes, one without.

Item 2-2, School staffing: One version with None boxes, one without.

Item 2-4, Teaching vacancies: Once version to match paper questionnaire, one version with Yes/No filter question (as outlined above).

Item 2-5c, Newly hired teachers in their first year: One version with None box, one without.

Item 4-2b(1-4), IEP students in classroom settings: One version with None boxes, one without.

Item 4-6b(2)/c/d – NSLP, FRPL: One version with None boxes, one without

Item 4-8a/b, Title I counts: One version with None boxes, one without.

The presence of the “none” boxes was the experimental treatment.

The resulting NTPS 2020-21 school questionnaire had two internet versions – an experimental version (with a filter question for item 2-4 AND “none” boxes) and a control version (without a filter question for item 2-4 and no “none” boxes). For schools that were sent a paper questionnaire, both received the same form, which had no filter question for item 2-4 and no “none” boxes. The two web design experiments were not crossed for the purposes of analyses. Schools were assigned to an instrument version treatment at the time of sampling.

Preliminary results are as follows:

Item 2-1, teacher counts:

No significant differences in item response by treatment for Q2-1, among public schools.

Several significant differences in item response by treatment for Q2-1, among private schools, specifically higher item response among experimental group (with “none” boxes) for the number of teachers in each of the part-time categories (at least 75% time, 50-75% time, 25-50% time, and less than 25% time).

Item 2-2, School staffing:

Significant differences in item response by treatment for Q2-2, among public schools, specifically higher item response among experimental group (with “none” boxes”) for all full-time and part-time staff, except:

Principals (both full-time and part-time)

Secretaries (both full-time and part-time)

Private schools exhibited fewer significant results where there was higher response among experimental groups (with “none” boxes). The significant results are summarized as follows:

Higher item response among experimental group (with “none” boxes) for the number of full-time Vice Principals, but none of the other first six positions.

Higher item response among experimental group (with “none” boxes) for the number of part-time staff for four of the first six positions (Coordinators, Librarians, Data Coaches, and Tech Specialists).

Higher item response among experimental group (with “none” boxes) for the number of full-time Social Workers and Psychologists, but no other support staff positions.

Higher item response among experimental group (with “none” boxes) for all part-time support staff positions.

Higher item response among experimental group (with “none” boxes) for all full-time and part-time aide positions.

Item 2-4, Teaching vacancies:

No significant difference in item response by treatment for Q2-4, among public schools or private schools.

No difference in the percent answering all thirteen vacancy items among public or private schools.

Item 2-5c, Newly hired teachers in their first year:

No significant differences in item response by treatment for Q2-5c, among public or private schools.

Item 4-2b(1-4), IEP students in classroom settings:

No significant differences in item response by treatment for Q4-2b, among public or private schools.

Item 4-6b(2)/c/d – NSLP, FRPL:

No significant difference in item response by treatment for Q4-6b(2), among public or private schools.

No significant difference in item response by treatment for Q4-6c/d, among public schools.

Item 4-8a/b, Title I counts:

No significant differences in item response for Q4-8 – both Title I Pre-K and K-12 students – among public and private schools.

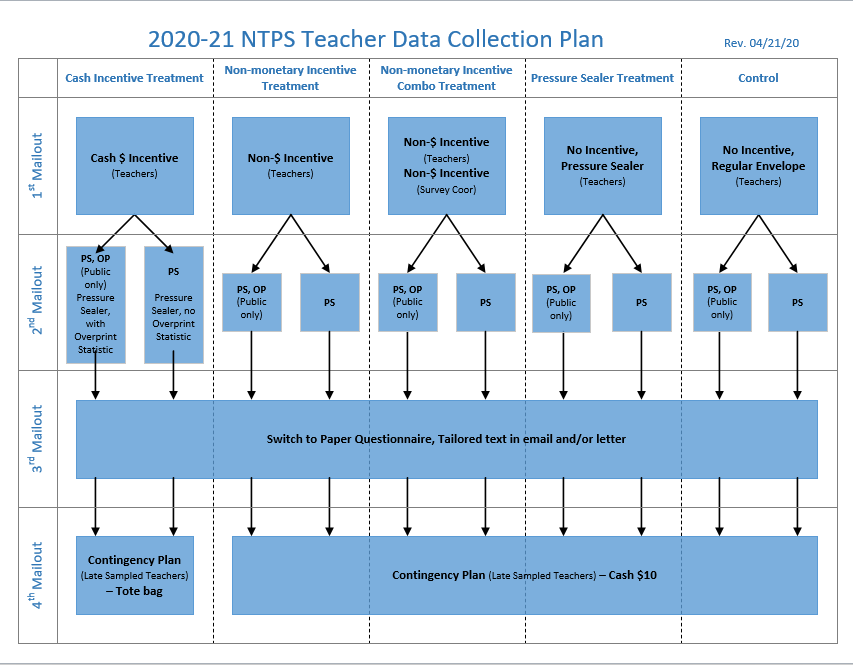

Two experiments aimed at increasing teacher-level response rates were planned for the 2020-21 NTPS, namely (1) further testing the use of teacher incentives and testing envelope packaging for teacher incentive letters, and (2) testing tailored contact materials. Each of these experiments is described briefly below.

Further testing the use of teacher incentives and testing the envelope packaging for teacher invitation letters. Due to the favorable results from the use of teacher incentives for the NTPS 2017-18, the NTPS 2020-21 included the use of incentives. Two types of incentives were offered in an experimental manner – a prepaid cash monetary incentive and a non-monetary incentive. Teachers in the experimental treatment received an education-branded canvas tote bag at the first contact by mail. The treatment was further separated into two groups – one where each of the teachers and the survey coordinator received a tote bag, and the other where only each of the teachers received a tote bag. The thought was that, since the survey coordinator is tasked with distributing the teacher packages, (s)he may also benefit from receiving the item, given that it is going to be apparent that there is something other than a letter in each envelope.

In order to assess the impact of receiving a non-monetary incentive over no incentive at all, a “no incentive” treatment was included in the design. This treatment was further separated into two groups – one where the teacher received his or her invitation letter in a large (custom) windowed envelope and one where the teacher received his or her invitation letter in a pressure-sealed mailer. The goal was to assess whether the use of a pressure sealed mailer (which are cheaper and more efficient for NPC assembly and QA) impacts response. The no incentive treatment using traditional envelopes is considered to be the control group for this experiment.

The resulting treatment groups were as follows:

Cash ($5) incentive treatment (teachers);

Non-monetary incentive treatment (teachers);

Non-monetary incentive combination treatment (teachers and survey coordinators);

No incentive, pressure sealer treatment; and

No incentive, envelope treatment (CONTROL).

The teacher treatment for each sampled school was assigned at the time of school sampling, prior to the start of data collection. All teachers within the same school received the same incentive treatment; there were not “mixed schools” where some teachers receive the prepaid cash monetary incentive while others receive the non-monetary tote bag incentive.

The planned testing of teacher incentives and envelope packaging described above was altered mid-data collection, as the coronavirus pandemic presented challenges and made the plan operationally infeasible. The plan was implemented for early waves of teachers (teachers sampled through mid-December 2020). Teachers sampled in late-December and beyond were instead offered a promised cash incentive to be mailed directly to the responding teacher later in the school year.

Preliminary analyses for the early waves of teachers for whom the original experimental design was implemented show that the cash incentive encouraged the highest response rate among public school teachers. Public school teachers that received the cash incentive also responded in significantly less time than the teachers that received the non-monetary incentive or no incentives. For private school teachers, the cash incentive and the non-monetary incentive both encouraged significantly higher response when compared to sending no incentives at all directly to teachers. Private school teachers that received the cash incentive also responded in significantly less time than the teachers that received the non-monetary incentive or no incentives.

Tailored Contact Materials at the teacher level (2T). Respondents sampled for NTPS receive letters and e-mails that emphasize the importance of their participation in the survey, but this information has not emphasized the ways in which NTPS data inform researchers and policymakers. In NTPS 2017-18, the statement “Public school teachers provided an average of 27 hours of instruction to students during a typical week in the 2015-16 school year. What about you?” was added to the outside of Third Reminder Teacher Letter envelopes for the final wave of sampled public school teachers.

Focus groups with teachers explored what statistics and other general revised wording is most salient to different types of respondents, and similar statements will be placed on materials sent to respondents, such as on the outside of envelopes or within enclosed letters, to determine whether targeted, persuasive messaging can increase response rates. Teachers seemed to take particular note of statistics related to finances (for example, salary and out of pocket spending on supplies) and where comparisons could be made either between statistics (for example, the amount of time spent providing instruction and worked overall) or types of teachers (for example, between teachers nationally and teachers in their own state).

The NTPS 2020-21 teacher data collection plan included an experiment in which tailored statistics were going to be overprinted on the exterior of the pressure-sealed mailers to non-responding teachers in the second teacher mailings. Teachers in the control group would receive their reminder letter with login information in a pressure-sealed mailer without overprinted information printed on the exterior. This experiment would have been crossed with the Teacher Incentive and Packaging experiments in the first mailing, yielding a total of ten experimental treatment groups. Finally, the later mailings and e-mails included tailored (with customized data/information) text in either letters or emails; however this will not be done experimentally.

The final design for teacher-level tests planned for inclusion in the 2020-21 NTPS is included in Exhibit 2 below.

Exhibit 2: 2020-21

National Teacher and Principal Survey – Planned Teacher-Level

Data Collection Tests

The planned testing of tailored contact materials at the teacher level was cancelled prior to the implementation of the test in production data collection, as the coronavirus pandemic presented challenges and made the plan operationally infeasible.

NTPS 2022 Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI) Pilot

Based on public comments received for NTPS 2017-18, cognitive testing was conducted in 2017, 2018, and 2022 (OMB #1850-0803 v.218 and v. 311) to test new NTPS content, including questions designed to ask public school principals and teachers about their sexual orientation and gender identity. The results indicated that principals and teachers understood these questions but speculated that others may be uncomfortable reporting their sexual orientation and gender identity, particularly when contacted through their school. Given the importance of collecting accurate demographic information about school staff, allowing analysis of any demographic disparities (for example, whether attrition or working conditions differ by demographic characteristics, including race/ethnicity, sex or gender, age, or sexual orientation), and not harming response rates, we conducted a pilot test with public school teachers in 2022. Initial findings were presented at the 2022 Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology (FCSM) Research and Policy Conference and can be viewed at https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/ntps/research.asp#SOGI.

For the 2022 pilot study, teachers were randomly assigned to receive either a questionnaire that included questions on their sex assigned at birth, gender, and sexual orientation in the demographics section, or a questionnaire that used only the demographics questions from past NTPS collections. Note that historically, NTPS has asked respondents whether they are male or female, without specifying whether this question referred to sex or gender, and without allowing respondents to provide any additional information.

Note that this pilot study was limited to public school teachers, and did not include either principals or private school staff. Principals were excluded since there are fewer principals than teachers, we would have to sample a large number of principals in order to detect any differences between the questionnaire types, and we expected our findings from public school teachers would apply to public school principals. Feedback from leaders of private school associations in 2017 indicated that both item and unit nonresponse could increase if the questions were included on questionnaires sent to private school principals or teachers. Private school staff were included in subsequent cognitive testing in 2022, and while participants were familiar with the terminology used in the questions, a private school administrator and a private school teacher disagreed with the presence of the questions and the underlying constructs, and the questions were removed from further rounds of cognitive testing with private school staff.

Including SOGI questions did not impact unit response rates for public school teachers. Item response rates for questions on sex and gender were similar to or higher than rates for other demographic items; the item response rate for sexual orientation was similar to rates for demographic items typically considered to be more sensitive. In addition, we received minimal negative feedback from sampled teachers during data collection.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Shawna M Cox (CENSUS/ADDP FED) |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2024-07-26 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy