Burden for 10 CFR Part 26 associated with Risk-Informed, Technology-Inclusive Regulatory Framework for Advanced Reactors Proposed Rule

Burden for 10 CFR Part 26 associated with Risk-Informed, Technology-Inclusive Regulatory Framework for Advanced Reactors Proposed Rule

DG-5073 - Fitness-For-Duty Programs For Commercial Nuclear Plants And Manufacturing Facilities Licensed Under 10 CFR Part 53

Burden for 10 CFR Part 26 associated with Risk-Informed, Technology-Inclusive Regulatory Framework for Advanced Reactors Proposed Rule

OMB:

U.S. NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION |

||

|

DRAFT REGULATORY GUIDE DG-5073 |

|

Proposed new Regulatory Guide 5.94, Revision 0 |

|

|

Issue Date: October 2024 Technical Lead: Brian Zaleski |

||

FITNESS-FOR-DUTY PROGRAMS FOR

COMMERCIAL

NUCLEAR PLANTS AND MANUFACTURING FACILITIES LICENSED UNDER 10 CFR

PART 53

Purpose

This regulatory guide (RG) describes an approach that is acceptable to the staff of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to meet regulatory requirements for fitness-for-duty (FFD) programs at commercial nuclear plants (CNPs) licensed under Title 10 of the Code of Federal Regulations (10 CFR) Part 53, “Risk-Informed, Technology-Inclusive Regulatory Framework for Commercial Nuclear Plants” (Ref. 1). Licensees, applicants, and other entities (as defined in 10 CFR 26.5) who implement FFD programs may consider this guidance when preparing an application for a 10 CFR Part 53 operating license, manufacturing license, combined license, limited work authorization, construction permit, or early site permit and when implementing the FFD program during construction, operation, and decommissioning.

Applicability

This RG applies to applicants and holders of a license under the provisions of 10 CFR Part 53 that implement an FFD program under 10 CFR Part 26, “Fitness for Duty Programs” (Ref. 2), Subpart M, “Fitness for Duty Programs for Facilities Licensed under 10 CFR Part 53.”

Applicable Regulations

10 CFR Part 26 describes the requirements and standards for the establishment, implementation, and maintenance of FFD programs.

For all FFD programs implemented under 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart M, the following requirements and subparts are applicable:

10 CFR 26.3(f) applies the 10 CFR Part 26 requirements to CNPs licensed under 10 CFR Part 53 and holders of a manufacturing license under 10 CFR Part 53.

10 CFR 26.4, “FFD program applicability to categories of individuals,” specifies the categories of individuals who are subject to 10 CFR Part 26 FFD programs.

10 CFR 26.5, “Definitions,” explains the relevant terminology.

10 CFR 26.23, “Performance objectives,” describes five performance objectives that every FFD program must meet.

10 CFR Part 26, Subpart A, “Administrative Provisions,” provides the requirements and standards for the establishment, implementation, and maintenance of FFD programs.

10 CFR Part 26, Subpart I, “Managing Fatigue,” contains the requirements for the management of fatigue for certain individuals who are subject to the FFD program.

10 CFR Part 26, Subpart M, “Fitness for Duty Programs for Facilities Licensed under 10 CFR Part 53,” provides the FFD requirements for 10 CFR Part 53 applicants, licensees, and other entities.

10 CFR Part 26, Subpart O, “Inspections, Violations, and Penalties,” provides the requirements that enable NRC inspection and enforcement of licensed activities to accomplish the purposes of 10 CFR Part 26.

In addition to the requirements and subparts that all licensees and other entities under 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart M, must implement, for FFD programs1 implemented under 10 CFR 26.605(a) and (b), a licensee or other entity must, and in some cases may, at their own discretion (as described in the Subpart M requirements), implement the following requirements and subparts:

10 CFR Part 26, Subpart C, “Granting and Maintaining Authorization,” establishes the requirements for a licensee or other entity to grant an individual or maintain an individual’s authorization for the types of access or perform the duties or responsibilities making them subject to 10 CFR Part 26. The requirements in this subpart apply to the FFD programs of licensees and other entities identified in 10 CFR 26.3(f) that elect not to implement the requirements in subpart M for the categories of individuals in 10 CFR 26.4 and those licensees and other entities that elect to implement the requirements in 10 CFR 26.605(b).

10 CFR Part 26, Subpart D, “Management Actions and Sanctions To Be Imposed,” establishes requirements and the minimum actions when an individual has violated the drug and alcohol provisions of an FFD policy or shows indications that he or she may not be fit to safely and competently perform his or her duties. The requirements in this subpart apply to the FFD programs of licensees and other entities identified in 10 CFR 26.3(f) that elect not to implement the requirements in subpart M for the categories of individuals in 10 CFR 26.4 and those licensees and other entities that elect to implement the requirements in 10 CFR 26.605(b).

10 CFR Part 26, Subpart E, “Collecting Specimens for Testing,” provides the requirements for the collection and testing for alcohol and collecting urine specimens for drug testing unless the licensee or other entity elects to use the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ “Mandatory Guidelines for Federal Workplace Drug Testing Programs” (HHS Guidelines) (Ref. 3) for urine testing. Licensees or other entities that collect urine specimens for drug testing and implement an FFD program in 10 CFR 26.605 must implement the following Subpart E requirements: 10 CFR 26.115, “Collecting a urine specimen under direct observation,” and 10 CFR 26.119, “Determining ‘shy’ bladder.” Licensees or other entities that collect urine specimens for conducting alcohol tests must implement the following Subpart E requirements: 10 CFR 26.91, “Acceptable devices for conducting initial and confirmatory tests for alcohol and methods of use,” 26.93, “Preparing for alcohol testing,” 26.95, “Conducting an initial test for alcohol using a breath specimen,” 26.97, “Collecting oral fluid specimens for alcohol and drug testing,” 26.99, “Determining the need for a confirmatory test for alcohol,” 26.101, “Conducting a confirmatory test for alcohol,” and 26.103, “Determining a confirmed positive test result for alcohol.”.

10 CFR Part 26, Subpart G, “Laboratories Certified by the Department of Health and Human Services,” contains a provision in 10 CFR 26.163(a)(2) that permits the conduct of special analyses of dilute specimens. Licensees and other entities who implement an FFD program under 10 CFR 26.605 and use a urine specimen for drug testing are required to implement special analysis testing under 10 CFR 26.163(a)(2).

10 CFR Part 26, Subpart H, “Determining Fitness-for-Duty Policy Violations and Determining Fitness,” contains requirements for determining whether a donor has violated the FFD policy and for making a determination of fitness. The requirements in this subpart apply to the FFD programs of licensees and other entities identified in 10 CFR 26.3(f) that elect not to implement the requirements in subpart M for the categories of individuals in 10 CFR 26.4 and those licensees and other entities that elect to implement the requirements in 10 CFR 26.605(b).

10 CFR Part 26, Subpart N, “Recordkeeping and Reporting Requirements,” provides recordkeeping and reporting requirements. The requirements in this subpart must be implemented by a licensee or entity that implements an FFD program in 10 CFR 26.605(b).

10 CFR Part 53 provides an alternative risk-informed and technology-inclusive regulatory framework for the licensing, construction, operation, and decommissioning of CNPs .

10 CFR 53.610, “Construction,” under 10 CFR Part 53 requires, in part, that licensees ensure the development and implementation of an FFD program under 10 CFR Part 26, to manage and control the construction activities.

10 CFR 53.620, “Manufacturing,” under 10 CFR Part 53 requires, in part, that holders of manufacturing licenses ensure the development and implementation of an FFD program, in accordance with 10 CFR Part 26, to manage and control the manufacturing activities within the scope of the manufacturing license.

10 CFR 53.860, “Security programs,” under 10 CFR Part 53 requires, in part, that each holder of an operating license or combined license develop, implement, and maintain an FFD program under 10 CFR Part 26.

10 CFR Part 73, “Physical Protection of Plants and Materials” (Ref. 4), prescribes requirements for the establishment and maintenance of a physical protection system that will be capable of protecting special nuclear material (SNM) at fixed sites and in transit and protecting plants in which SNM is used.

10 CFR 73.100, “Technology-inclusive requirements for physical protection of licensed activities at commercial nuclear plants against radiological sabotage,” provides requirements for the physical protection of CNPs licensed under 10 CFR Part 53.

10 CFR 73.120, “Access authorization program for commercial nuclear plants,” provides requirements for granting, maintaining, and denying authorization to individuals seeking unescorted access to a CNP licensed under 10 CFR Part 53.

49 CFR Part 40, “Procedures for Transportation Workplace Drug and Alcohol Testing Programs” (Ref. 5), tells all parties that conduct drug and alcohol tests required by U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) regulations how to conduct these tests and which procedures to use. This part concerns the activities of transportation employers, safety-sensitive transportation employees (including self-employed individuals, contractors, and vendors as covered by DOT regulations), and service agents.

Related Guidance

RG 5.77, “Insider Mitigation Program” (Ref. 6), provides guidance for monitoring the initial and continuing trustworthiness and reliability of individuals granted or retaining unescorted access authorization to a protected or vital area, and implementation of defense-in-depth methodologies to minimize the potential for an insider to adversely affect, either directly or indirectly, the licensee’s capability to prevent significant core damage and spent fuel sabotage.

RG 5.84, “Fitness-for-Duty Programs at New Reactor Construction Sites” (Ref. 7), provides guidance for implementing 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart K, “FFD Program for Construction.”

RG 5.89, “Fitness for Duty Programs for Commercial Power Reactor and Category I Special Nuclear Material Licensees” (Ref. 8), provides guidance for the FFD programs implemented at commercial power reactors and Category I SNM licensees.

Draft Regulatory Guide (DG)-5078 (proposed new RG 5.99), “Fatigue Management for Nuclear Power Plant Personnel at Commercial Nuclear Plants Licensed under 10 CFR Part 53,” (Ref. 9) provides guidance for implementing 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart I, “Managing Fatigue.”

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ “Mandatory Guidelines for Federal Workplace Drug Testing Programs” (HHS Guidelines) provides proposed or final drug testing guidelines for the collection, shipment, storage, and testing of urine, oral fluid, and hair specimens and the medical review officer (MRO) evaluation of the laboratory test results.

RGs 5.77 and 5.84 were developed for CNP and Category I SNM licensees subject to the regulatory requirements in 10 CFR 26.3(a) through (d) and licensed under 10 CFR Parts 50, 52, or 70 and did not include (or consider) CNPs licensed under 10 CFR Part 53. However, these RGs provide information for sections in 10 CFR Part 26 that applicants, licensees, and other entities under 10 CFR Part 53 may want to review in developing and implementing their FFD program.

Purpose of Regulatory Guides

The NRC issues RGs to describe methods that are acceptable to the staff for implementing specific parts of the agency’s regulations, to explain techniques that the staff uses in evaluating specific issues or postulated events, and to describe information that the staff needs in its review of applications for permits and licenses. Regulatory guides are not NRC regulations and compliance with them is not required. Methods and solutions that differ from those set forth in RGs are acceptable if supported by a basis for the issuance or continuance of a permit or license by the Commission.

Paperwork Reduction Act

This RG provides voluntary guidance for implementing the mandatory information collections in 10 CFR Parts 26, 53, and 73 that are subject to the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995 (44 U.S. Code (USC) 3501 et. seq.). These information collections were approved by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), under control numbers 3150-0146, 3150-XXXX, and 3150-0002, respectively. Send comments regarding this information collection to the FOIA, Library, and Information Collections Branch (T6-A10M), U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Washington, DC 20555-0001, or by email to [email protected], and to the OMB Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Attn: Desk Officer for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 725 17th Street, NW Washington, DC 20503.

Public Protection Notification

The NRC may not conduct or sponsor, and a person is not required to respond to, a collection of information unless the document requesting or requiring the collection displays a currently valid OMB control number.

Purpose of Regulatory Guides 5

Public Protection Notification 5

Consideration of International Standards 8

C. STAFF REGULATORY GUIDANCE 10

1. 10 CFR 26.601, “Applicability.” 10

2. 10 CFR 26.4, “FFD program applicability to categories of individuals.” 10

a. Holders of a Manufacturing License 10

b. Transportation of a Manufactured Reactor 13

c. Licensees or Other Entities of a Commercial Nuclear Plant 13

d. Risk-informed Evaluation Process 14

3. 10 CFR 26.603(a), FFD Program Description 15

a. 10 CFR 26.603(a)(1), Description of Analysis Performed under 10 CFR 26.603(c) 15

b. 10 CFR 26.603(a)(2), Type of FFD Program to Be Implemented 16

c. 10 CFR 26.603(a)(3), Program Applicability to Individuals 16

d. 10 CFR 26.603(a)(4), Drug and Alcohol Testing and Fitness Determinations 17

e. 10 CFR 26.603(a)(5), Performance Monitoring and Review Program 17

4. 10 CFR 26.603(c), Criterion and Analysis for an FFD program 18

5. 10 CFR 26.603(d), FFD Performance Monitoring and Review 18

d. Defining Acceptable Performance (i.e., FFD program success) 23

f. 10 CFR 26.603(d)(1), Performance Measures and Thresholds 30

6. 10 CFR 26.603(e), FFD Program Change Control 57

7. 10 CFR 26.605, “FFD program requirements for facilities that do not implement § 26.604” 58

a. 10 CFR 26.605(b), FFD Program for Operation of a Commercial Nuclear Plant 58

8. 10 CFR 26.606, “Written policy and procedures.” 59

a. 10 CFR 26.606(a), Contents of Written Policies 59

b. 10 CFR 26.606(b), Contents of Written Procedures 63

9. 10 CFR 26.607, “Drug and alcohol testing.” 64

a. 10 CFR 26.607(b)(1), Pre-access Testing 66

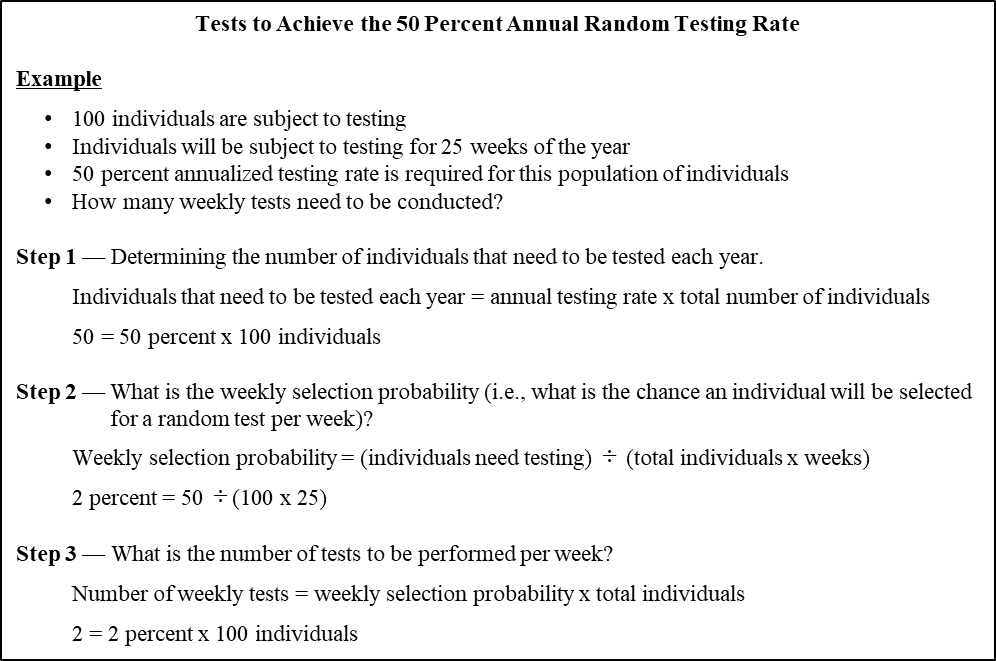

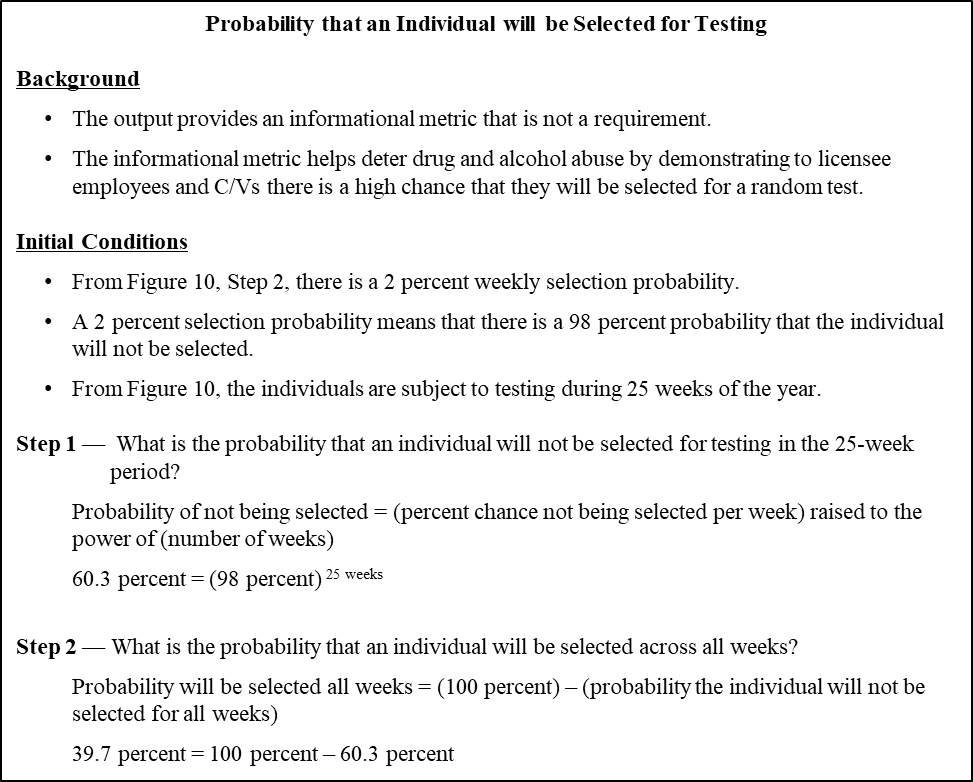

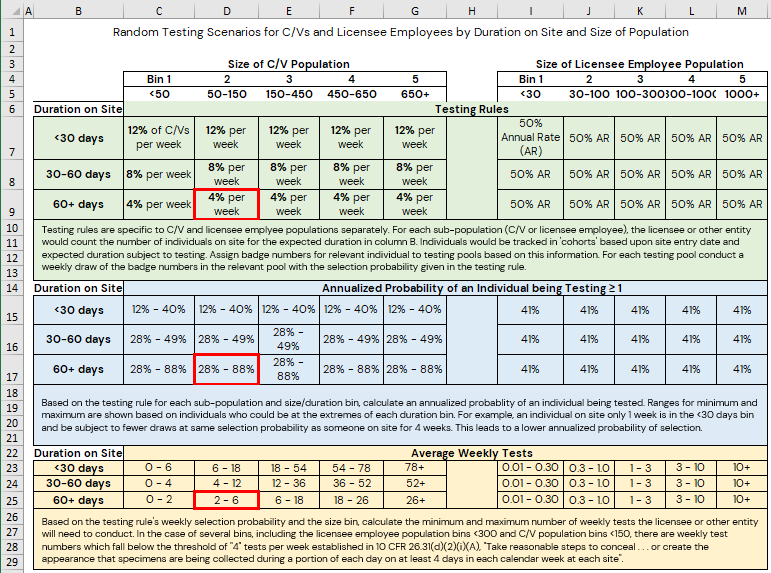

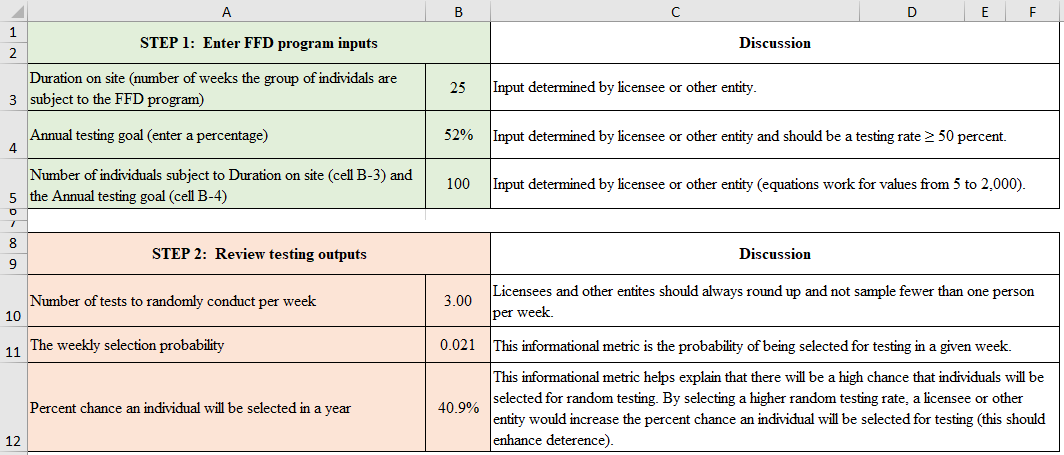

b. 10 CFR 26.607(b)(2), Random Testing 67

c. 10 CFR 26.607(b)(3), For-cause Testing 73

d. 10 CFR 26.607(b)(4), Post-event Testing 75

e. 10 CFR 26.607(b)(5), Follow-up Testing 77

f. 10 CFR 26.607(c), Urine and Oral Fluid Specimens 77

g. 10 CFR 26.607(d), Privacy and Integrity 78

h. 10 CFR 26.607(e), Collection Facility 78

i. 10 CFR 26.607(f), Initial Testing 79

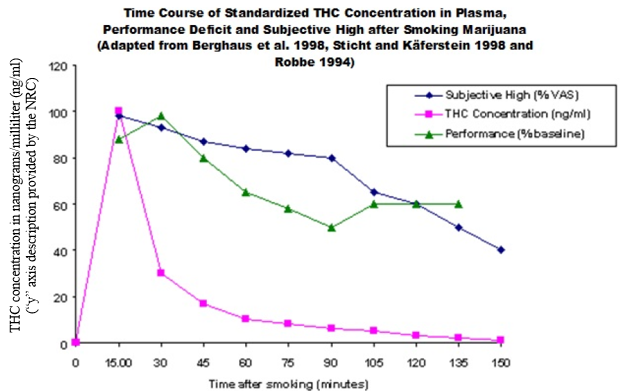

j. 10 CFR 26.607(g), Oral Fluid 79

k. 10 CFR 26.607(h), Point of Collection Testing and Assessment 82

l. 10 CFR 26.607(i), Hair Testing 82

m.10 CFR 26.607(j), Portal Area Monitor Screening 83

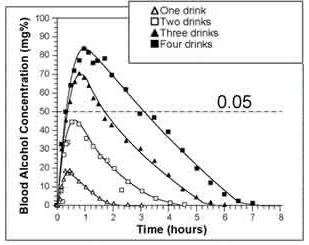

o. 10 CFR 26.607(k), Blood Specimens 84

p. 10 CFR 26.607(l), Custody-and-Control Form 85

q. 10 CFR 26.607(m), MRO Review and Training 85

10. 10 CFR 26.608, “FFD program training.” 86

11. 10 CFR 26.609, “Behavioral observation.” 89

12. 10 CFR 26.610, “Sanctions.” 92

a. Determining Sanction Groups by Roles and Responsibilities 92

b. Sanctions Based on Risk Significance 93

13. 10 CFR 26.611, “Protection of information.” 95

a. 10 CFR 26.611(a), Protecting Information 95

b. 10 CFR 26.611(b), Consent 97

14. 10 CFR 26.613, “Appeal process.” 98

15. 10 CFR 26.615, “Audits.” 99

a. 10 CFR 26.615(a), General 99

b. 10 CFR 26.615(b), Frequency 100

c. 10 CFR 26.615(c), Joint Audits or Accepting Party Audits 101

16. 10 CFR 26.617, “Recordkeeping and reporting.” 101

a. 10 CFR 26.617(a), Recordkeeping 101

b. 10 CFR 26.617(b)(1), Reporting to the NRC Operations Center 104

c. 10 CFR 26.617(b)(2), Annual Program Performance Reports 106

d. 10 CFR 26.617(c), Sharing of FFD-Related Information 106

17. 10 CFR 26.619, “Suitability and fitness determinations.” 106

Reason for Issuance

This document provides guidance for the FFD program requirements detailed in 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart M. These details involve, in part, policies, procedures, training, drug and alcohol testing, laboratory testing processes, behavioral observation, MRO responsibilities, fitness determinations, reporting, and recordkeeping. The FFD program for facilities licensed under 10 CFR Part 53 also includes requirements for a performance monitoring and review program (PMRP), and an FFD program change control process. Licensees and other entities who are not implementing an FFD program under 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart M, should use the guidance in the documents listed in section A, “Introduction,” sub-section “Related Guidance,” of this RG.

Background

The requirements in 10 CFR Part 26 establish a regulatory framework under which FFD programs that comply with these requirements meet the performance objectives in 10 CFR 26.23, “Performance objectives,” including providing reasonable assurance that individuals subject to these FFD programs are trustworthy and reliable, as demonstrated by the avoidance of substance abuse, and are not under the influence of any substance or mentally or physically impaired from any cause that would in any way adversely affect their ability to perform their duties safely and competently. The NRC amended 10 CFR Part 26 in the final rule that also created 10 CFR Part 53. Those amendments produced 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart M, for use by 10 CFR Part 53 licensees and other entities. Licensees and other entities that comply with the Subpart M framework meet the 10 CFR 26.23 performance objectives.

The requirements in 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart M, are performance-based and risk-informed consistent with the risk associated with the facility and human activities necessary to (1) effectively operate, maintain, surveil, decommission, and protect the facility, materials, and sensitive information (e.g., classified, safeguards, medical, and private information), (2) prevent or mitigate radiological consequences should the facility experience a structure, system, or component (SSC) failure, a reactor transient or accident, or other abnormal occurrence, and (3) detect, assess, and respond to an internal or external security incident or an adverse environmental condition (e.g., hazardous chemicals, earthquake, flooding).

The Subpart M framework supplements the access authorization program under 10 CFR 73.120 for CNPs licensed under 10 CFR Part 53. The regulations in 10 CFR 73.120 establish the general performance objective that individuals subject to the access authorization program are trustworthy and reliable, such that they do not constitute an unreasonable risk to public health and safety or the common defense and security, including the potential to commit radiological sabotage. The defense in depth afforded by the FFD and access authorization programs provide reasonable assurance that individuals who maintain unescorted access to the protected area,2 SNM, or sensitive information are trustworthy, reliable, and fit for duty.

Consideration of International Standards

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) works with member states and other partners to promote the safe, secure, and peaceful use of nuclear technologies. The IAEA develops Safety Requirements and Safety Guides for protecting people and the environment from harmful effects of ionizing radiation. This system of safety fundamentals, safety requirements, safety guides, and other relevant reports, reflects an international perspective on what constitutes a high level of safety. To inform its development of this RG, the NRC considered IAEA Safety Requirements and Safety Guides pursuant to the Commission’s International Policy Statement (Ref. 10) and Management Directive and Handbook 6.6, “Regulatory Guides” (Ref. 11).

The staff reviewed IAEA Safety Guide No. NS‑G‑2.8, “Recruitment, Qualification and Training of Personnel for Nuclear Power Plants,” issued 2004 (Ref. 12), as it is pertinent to this RG. The safety guide states, “A programme to identify personnel with a tendency towards drug or alcohol abuse should be established. Personnel prone to drug or alcohol abuse should not be employed for safety related tasks.” This RG describes a method for implementing the NRC’s requirements for specific elements of such a program.

The terms “screen” and “screening

test” for drugs or alcohol are used in this guide to describe

when a biological specimen is collected and assessed by FFD program

personnel using a point of collection testing (POCT) device or an

instrument that passively collects (but does not store) and analyzes

a biological specimen. The

word “test” for the drug and alcohol testing under 10

CFR 26.605 describes the process when a biological specimen is

collected by FFD program personnel and is (1) sent to an

HHS-certified laboratory for drug testing and analysis or (2)

analyzed for alcohol by an evidentiary breath testing device.

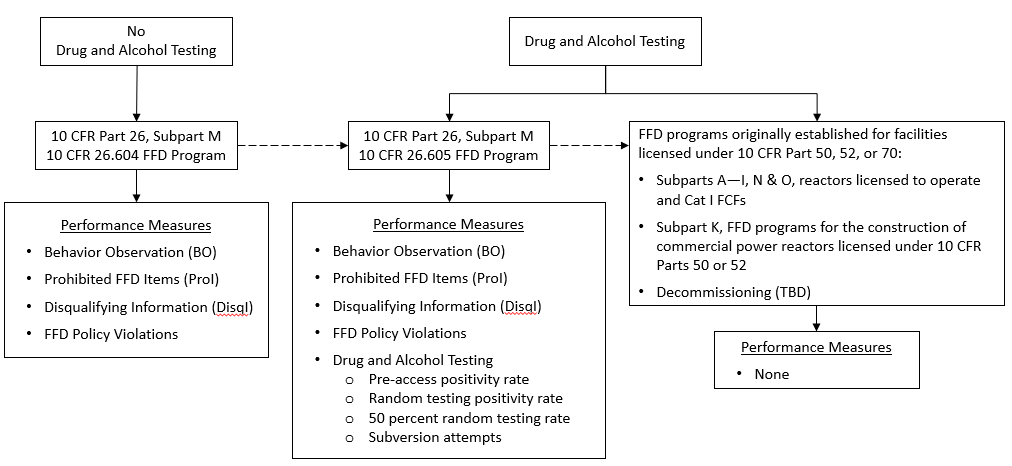

A licensee or other entity in 10 CFR 26.3(f) may choose to establish, implement, and maintain an FFD program that meets the requirements of 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart M, and apply this program to the individuals specified in 10 CFR 26.4. If the licensee or other entity does not implement an FFD program under 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart M, then the licensee or other entity is required to establish, implement, and maintain an FFD program that meets the requirements of Subparts A through I, N, and O of 10 CFR Part 26. A licensee or other entity covered by 10 CFR 26.3(f) may not implement 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart K, unless it requests an exemption from the requirements in 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart M, to implement Subpart K and the NRC grants the exemption request.

a. Holders of a Manufacturing License

The holder of a manufacturing license for the assembly or testing of a reactor under 10 CFR Part 53 should consider applying its FFD program to all individuals who—

implement the FFD program.

are granted unescorted access to the reactor during its assembly or testing;

operate or direct the operation of SSCs that are needed to assemble or test a reactor;

perform maintenance or surveillance or direct the maintenance or surveillance of SSCs of the reactor;

perform design changes on SSCs of the reactor;

perform quality assurance or quality verification activities; or

perform security duties as an armed security force officer, alarm station operator, response team leader, or watchman, hereafter referred to as “security personnel.”

Based on the duties and responsibilities described above, the holder of a manufacturing license should implement an FFD program that should apply to individuals who manage, direct, or perform functions that include, but are not limited to, the following:

activities during the assembly or testing the reactor necessary to meet NRC‑required codes and standards from the American Society of Mechanical Engineers or Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers;

assembling, installing, testing, or operating an SSC used for the following: control of reactivity, temperature, pressure, or coolant flow; reactor operation; accident or transient response or mitigation; heat transfer and management; or radiation and chemical detection and monitoring;

maintaining, testing, monitoring, and upgrading the cybersecurity and information technology services used for the assembly or testing of a reactor;

assembling, installing, testing, or operating the SSCs for the management of radioactive or hazardous materials for or during assembly or testing of the reactor;

controlling access to the protected area or foreign material exclusion areas during the assembly or testing of the reactor;

performing inspections, tests, analyses, and acceptance criteria or otherwise implementing the quality assurance program required by 10 CFR Part 53;

participating in the day-to-day operations of the FFD program, as defined by the licensee’s or other entity’s procedures.

The regulation in 10 CFR 26.4(g) refers to the following individuals as “FFD program personnel” if they are involved in the day-to-day operations of the program, as defined by the procedures of the licensees and other entities:

All persons who can link test results with the individual who was tested before an FFD policy violation determination is made, including, but not limited to the MRO.

These persons could include those who receive, read, manage (e.g., store, file), or communicate drug or alcohol test results (i.e., test results from an HHS-certified laboratory). The MRO should be considered as FFD program personnel if involved in the day-to-day operations of the program, regardless of full- or part‑time employment, or location of employment because the MRO must review positive test results obtained from an HHS-certified laboratory and should assist FFD program staff in the evaluation of subversion attempts. Also, and if applicable to the FFD program, 10 CFR 26.183(c) states that the MRO is responsible for identifying any issues associated with collecting and testing specimens, which may inform a licensee’s or other entity’s issuance of an FFD policy violation. FFD program personnel would not include individuals who are assigned to monitor portal area screening devices or conduct drug and alcohol screening tests or maintain FFD program information and computer systems.

Persons who make determinations of fitness.

These persons would not include medical or clinical professions who make determinations of fitness only occasionally and are not otherwise involved in the day-to-day operations of the FFD program.

Persons who make authorization decisions.

These persons should include individuals who have the title “reviewing official” as defined in 10 CFR 26.5 and would not include contractors/vendors (C/Vs) that perform reviews, activities, and investigations for the licensee or other entity to support a Reviewing Official’s determination whether to grant, maintain, or deny authorization for any individual.

Persons involved in selecting or notifying individuals for testing.

This would include the FFD program staff who select individuals subject to pre-access screening using hair or a point of collection testing and assessment (POCTA) device, random screening or testing, and follow-up testing. This would not include individuals who direct others to be subject to a for-cause or post-event test. For example, supervisors who direct staff members to report to the collection facility for a for-cause or post-event test would not be FFD program personnel because the initiating condition would be an observation or event that warrants the test. Also, administrative personnel, managers, or supervisors who are not part of the FFD program staff but who may receive direction from the FFD program staff to notify a particular person to report for a drug or alcohol screening or test, are not FFD program personnel.

FFD program personnel must be subject to random testing. To help ensure the integrity of the random testing process, licensees and other entities should place their FFD program personnel into a random testing pool managed by a different licensee or other entity. This would help ensure that FFD program personnel would be unable to predict when they would be subject to a random test.

All persons involved in the collection or onsite testing of specimens.

All persons involved in the collection of specimens should include individuals who perform multiple roles and responsibilities that include the collection of specimens, even if collections are not performed on a day-to-day basis.

Individuals who do not routinely collect specimens and do not perform FFD program activities on a day-to-day basis would not be considered FFD program personnel. These individuals could be managers, supervisors, or other licensee- or other entity-designated personnel who are trained under 10 CFR 26.608, “FFD program training,” to collect specimens and directed to collect one or more specimens during a particular time, shift, or day. These individuals would typically be called upon to conduct collections for the random testing program and may be used for all test conditions.

All persons involved with the collection of specimens would include those licensee- or other entity-designated individuals who are responsible for the packaging, temporary storage, and shipment of specimens to an HHS-certified laboratory or the storage of POCTA devices before and after their use (if used to inform a determination of fitness or suitability determination). These persons should include individuals responsible for maintaining specimen integrity, for example, individuals who ensure that specimens or POCTA and other screening devices or instrumentation are controlled to prevent tampering. Technicians who maintain or surveil the SSCs that store specimens and POCTA devices would typically not be considered FFD program personnel.

Individuals assigned to a license or other entity facility (like a loading dock) where packaged specimens are awaiting shipment (e.g., by U.S. postal service or private shipping companies) to an HHS-certified laboratory should be subject to the FFD program. Individuals who work at offsite collection facilities not owned or operated by the licensee or other entity would not be subject to the FFD program and would not be FFD program personnel.

The individuals involved in the onsite testing of specimens should include those licensee- or other entity-designated individuals who are directed to facilitate the use of a POCTA device (which would include an evidentiary breath testing device) to screen individuals for drugs, drug metabolites, and alcohol.

b. Transportation of a Manufactured Reactor

For the transportation of a manufactured reactor, the holder of the manufacturing license should ensure that the operators and standby operators that conduct the transport, as a conveyance,3 are subject to the DOT drug and alcohol testing program in 49 CFR Part 40. A licensee or other entity may assess whether the operators of the conveyance had any drug or alcohol violations while subject to the DOT’s Federally mandated drug and alcohol testing. This information may be obtained from the DOT’s website at https://clearinghouse.fmcsa.dot.gov.

Individuals subject to DOT drug and alcohol testing may be randomly tested at frequencies below that established in 10 CFR Part 26. The DOT random testing rates may change based on the mode of transportation or by calendar year.

If an individual conducting the conveyance appears impaired, either before or after entry in the NRC-licensed facility (e.g., protected area), the licensee and other entity should take timely action to coordinate with the conveyor the implementation of corrective actions before the potentially impaired individual attempts to perform the conveyance. Under its own discretion, a licensee or other entity could implement a contractual requirement with the conveyor to require drug and alcohol screening to help inform a licensee’s or other entity’s immediate evaluation of the individual’s ability to safely and competently perform the conveyance.

c. Licensees or Other Entities of a Commercial Nuclear Plant

A licensee or other entity under 10 CFR Part 53 must apply its FFD program to the categories of individuals described in 10 CFR 26.4. Operating experience from the large light-water reactor (LLWR) community should be used to assist in the application of the FFD program to individuals. For example, the NRC understands that it is common that licensees and other entities of LLWRs licensed under 10 CFR Part 50, “Domestic Licensing of Production and Utilization Facilities” (Ref. 13), apply their FFD program to all individuals who direct, perform, or could direct or perform those duties and responsibilities described in 10 CFR 26.4 or maintain unescorted access to the NRC-licensed facility (i.e., not just the protected area). In fact, the NRC has been informed by some licensees of LLWRs that every individual possessing a licensee- or other entity-issued badge to enter (i.e., gain access to) the site or an emergency response facility (whether onsite or offsite), or have access (whether the access is physical or electronic) to an SSC required for facility operations, would be subject to the FFD program or would be escorted.

d. Risk-informed Evaluation Process

The requirements in 10 CFR 26.4(a)(1) and (4) state that the FFD program must be applied to those individuals who operate and maintain or direct the operation and maintenance, respectively, of systems and components “that a risk-informed evaluation process or alternative method for evaluating safety significance has shown to be significant to public health and safety.” In lieu of applying the FFD program to all individuals, the following references may assist a licensee or other entity in its evaluation process or alternate method used to determine whether to apply the FFD program to certain individuals, but not others, based on the risk-significance of the component or structure.

10 CFR 50.69, “Risk-informed categorization and treatment of structures, systems and components for nuclear power reactors.”

Regulatory Guide 1.201, “Guidelines for Categorizing Structures, Systems, and Components in Nuclear Power Plants According to Safety Significance” (Ref. 14)

Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI) guidance document NEI 00-04, “10 CFR 50.69 SSC Categorization Guidelines” (Ref. 15)

“A new method for safety classification of structures, systems and components by reflecting nuclear reactor operating history into importance measures,” J. Cheng et al., Nuclear Engineering and Technology, Vol. 54, Issue 4, April 2022. Publicly available through www.ScienceDirect.com.

If the licensee or other entity elects to perform a risk-informed evaluation process or alternative method for evaluating safety significance, then the licensee or other entity should assess the below list of SSCs. The evaluation process should include an assessment of the safety‑significant function(s) of the SSC and the roles and responsibilities of any individual required to perform any action required for the SSC to fulfill its intended safety function. For this guide, a safety-significant function is one whose degradation or loss could result in a significant adverse effect on defense in depth, safety margin, or risk. This function would be accomplished by SSCs that are relied on to remain functional during and following design-basis and licensing-basis events other than design-basis accidents. These functions ensure the integrity of the reactor system (e.g., reactor containment vessel or shell and its thermodynamic heat cycle boundary); the capability to shut down the reactor and maintain it in a safe‑shutdown condition; and the capability to detect, prevent, or mitigate the consequences of accidents that could have onsite and offsite dose consequences. The SSCs should include those that are needed for the following:

containment;

nuclear fuel loading, recovery, or removal, or configuration control;

monitoring, maintaining, or controlling nuclear reactivity (e.g., fuel, poison, reflector, or moderator control), or coolant temperature, pressure, or flow;

system isolation and pressure, temperature, and flow management performed by SSCs not associated with controlling nuclear reactivity;

detecting, assessing, or responding to normal operations, transients, and abnormal conditions;

maintaining or restoring steady-state operation or the thermodynamic heat cycle, or causing and maintaining reactor shutdown;

detecting, assessing, or responding to radiation or contamination levels or hazardous chemical conditions; or

detecting, assessing, or responding to unauthorized access to the reactor, its SSCs, and licensee‑designated control areas.

10 CFR 26.603(a) requires certain 10 CFR Part 53 applicants to include a description of their FFD programs in their final safety analysis reports. This description informs the NRC inspection process and discussions with the applicant’s, licensee’s, or other entity’s FFD program staff. The entities that are required to submit these FFD program descriptions are those applicants that must comply with the application requirements in 10 CFR Part 53, Subpart H. In Subpart H, 10 CFR 53.1309(a)(6) requires an applicant for a construction permit to provide a description of its FFD program in its PSAR. Under 10 CFR 53.1279(b)(4), 53.1369(x), and 53.1416(a)(24), an applicant for a manufacturing license, operating license, and combined licensee, respectively, is required to provide a description of its FFD program in its final safety analysis report.

If the licensee or other entity performed the analysis under 10 CFR 26.603(c) and the analysis demonstrates that the facility and its operation4 satisfy the criterion in 10 CFR 53.860(a)(2), then the licensee or other entity must include in its FFD program a summary of the analysis, including the assumptions, methodology, conclusion, and references. If the analysis is equivalent to the analysis performed for the physical security, access authorization, other 10 CFR Part 53 program, then the licensee or other entity may reference the analysis performed for a different program; however, for the FFD program, the analysis must include a description of the facility and its operation. The licensee or other entity must maintain the analysis until permanently ceasing operations under 10 CFR Part 53.

The description must include the assumptions associated with the operation of the facility. This description will support an NRC review of the human performance elements necessary to safely construct, operate, maintain, decommission, and secure the facility. These assumptions should include those associated with (1) safety and security margins, (2) the principal individuals who must be on shift and the human actions required to operate and maintain (e.g., monitor, surveil, and repair) the facility in a safe operating or shutdown condition, (3) the principal individuals assigned on shift to perform or direct the performance of human actions to secure and protect the facility and control sensitive information (without providing safeguards information), (4) individuals assigned to offsite monitoring or control stations (including stations to implement physical protection) who are assigned to supervise, observe, or direct individuals on shift at the CNP site, and (5) individuals assigned to implement actions after a design basis event or accident occurs.

The description must include the methodology used in the site‑specific analysis to demonstrate that the facility and its operation satisfy the criterion in 10 CFR 53.860(a)(2). This description should include any details of the analysis, analytical software (e.g., software name, version, and vendor), and calculational assumptions that the applicant, licensee, or other entity used that would assist the NRC in its evaluation of the analysis.

The description must describe any references used to support the analysis. This should include bibliographic information for technical studies, manuals, guidance, standards, and supporting documentation used in the analysis.

The regulation in 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart M, gives 10 CFR Part 53 licensees and other entities flexibility in selecting the set of FFD program requirements they will implement. In 10 CFR 26.603(a)(2), the NRC requires the licensee’s or other entity’s FFD program description to include a statement declaring which set of requirements the licensee or other entity will implement.

A licensee or other entity may implement the following sets of requirements:

all 10 CFR Part 26 requirements except those in Subparts K and M;

10 CFR 26.604, “FFD program requirements for facilities that satisfy the § 26.603(c) criterion,” if they are a licensee or other entity whose facility and its operation satisfy the criterion in 10 CFR 26.603(c); or

10 CFR 26.605, “FFD program requirements for facilities that do not implement § 26.604,” if they are a licensee or other entity whose facility and its operation satisfy the criterion in 10 CFR 26.603(c); a licensee or other entity who does not satisfy the criterion in 10 CFR 26.603(c); or a holder of a manufacturing license that allows the assembly or testing of a manufactured reactor.

Knowledge of which FFD program requirements the licensee or other entity intends to implement will inform the NRC’s inspection plan and review of human actions to construct, operate, maintain, decommission, and secure the facility.

The FFD program description must discuss which individuals described in 10 CFR 26.4 are subject to the licensee’s or other entity’s FFD program. This description should inform the NRC of any substantial differences from 10 CFR 26.4 the licensee or other entity expects in its categories of individuals who will be subject to the FFD program. Although the descriptions in 10 CFR 26.4 are for the LLWRs licensed under 10 CFR Part 50 or 10 CFR Part 52, “Licenses, Certifications, and Approvals for Nuclear Power Plants” (Ref. 16), they are applied to facilities licensed under 10 CFR Part 53 through 10 CFR 26.3(f) because the roles and responsibilities described in 10 CFR 26.4 apply to individuals at CNPs licensed under 10 CFR Part 53. Understanding the licensee’s or other entity’s FFD program applicability to individuals would enhance the NRC’s ability to assess the contribution of the FFD program to human performance in the conduct of duties and responsibilities necessary to operate, maintain, surveil, secure, and decommission the facility, if applicable. This information would also be used to inform NRC inspection of those categories of individuals who perform their principal roles and responsibilities onsite or offsite (i.e., at a remote operations or monitoring station), including individuals who may not be afforded physical unescorted access to the NRC-licensed facility, SNM, or sensitive information, but should be subject to the FFD program, such as individuals who operate or maintain cybersecurity and information systems.

The FFD program description must detail the licensee’s or other entity’s drug and alcohol testing and fitness determinations process. The description should discuss the following: whether the licensee or other entity plans to implement the drug testing requirements as provided in 10 CFR Part 26, such as Subparts E and H, or use provisions from the HHS Guidelines in its procedures; the collection and testing facilities to be used (including names and locations if not the licensed facility for which this description is being provided for); the biological specimens to be collected; planned use of a POCTA device for either oral fluid or urine and any instrumentation that may be used to passively detect drugs, alcohol or both; the suitability and determination of fitness process; and the sanctions to be imposed on one and two confirmed FFD policy violations. The description should include the manufacturer’s name and unique identification number of any POCTA device and passive screening instrumentation planned for use at the NRC‑licensed facility.

Regarding the description of the suitability and fitness determination process, these processes are similar, but they are not equivalent. Although they are both evaluations to determine whether to assign individuals to the duties specified in 10 CFR 26.4, a suitability determination is typically focused on whether the licensee or other entity should assign an individual a particular duty or responsibility or grant authorization. For example, the results of pre-access testing would inform the licensee’s or other entity’s decision whether to grant an individual authorization as defined in 10 CFR 26.5. A suitability evaluation would also include cases where an individual exhibits, for example, claustrophobia (such that the individual should not work in confined spaces); facial or respiratory performance considerations that may prevent proper donning or use of personnel protective equipment (e.g., an oxygen breathing apparatus); or acrophobia (such that the individual should not be assigned to work in elevated positions). This suitability determination would help provide assurance that such individuals, subject to the FFD program, are fit for duty to safely and competently perform their duties and responsibilities. Since this suitability determination could be site-, facility-, duty-, or responsibility-specific, it should be performed by an individual with detailed knowledge of the individual’s condition, the site and facility, and the duties and responsibilities to be performed by the individual. The applicant, licensee, or other entity should describe its planned suitability process.

A determination of fitness is typically the process entered when there are indications that an individual specified in 10 CFR 26.4 may be in violation of the licensee’s or other entity’s FFD policy or procedure; For example, the individual was identified as using an illegal substance or is a member of a group acting or advocating for an unlawful change to the U.S. government or violence to a particular ethnic, religious, or cultural group. A determination of fitness may require the use of a medical or clinical professional, called on by the licensee or other entity, to evaluate the individual, formulate a treatment plan, and recommend whether the individual’s authorization should be reinstated. The types of professionals called upon to make this determination should be educated, accredited, or trained in the specific area(s) of concern (e.g., drug or alcohol abuse, psychosis, etc.). The applicant, licensee, or other entity should describe its determination of fitness process including, if applicable, its planned use of the requirements in 10 CFR 26.187, “Substance abuse expert,” and 26.189, “Determination of fitness.”

In the summary of its PMRP, the licensee or other entity must inform the NRC of the initial set of performance measures and thresholds to be used in the PMRP. Summaries should state whether the measures and thresholds apply to the whole population subject to the FFD program or individuals in a particular employment or labor category. The description should also contain the information used to justify the measure or threshold; for example, how the measure or threshold was developed, which comparable facilities were part of the comparative assessment, and whether an FFD program or industry data were used to establish the threshold.

This section states that for a licensee or other entity to implement an FFD program under 10 CFR 26.604, the licensee or other entity must perform a site-specific analysis to demonstrate that the facility and its operation satisfy the criterion in 10 CFR 53.860(a)(2). In Section C.3.a in this RG, guidance is provided for the description of the human performance actions necessary to, in part, operate the facility and implement actions after a design basis event or accident occurs. 10 CFR 26.603(c) also requires that the licensee or other entity must maintain the analysis, including updates to reflect changes made to the staffing, FFD programs, or offsite support resources described in the analysis, to show that the facility and its operation continues to satisfy the criterion, until permanent cessation of operations under 10 CFR 53.1070.

The changes made to the licensee or other entity staff could include those individuals who perform those duties and responsibilities identified in Section C.3.a. Changes made to the FFD program could involve program changes in which the actions implemented to mitigate a potential reduction in program effectiveness were not effective and resulted or could have resulted in adverse human performance of the individuals who perform those duties and responsibilities identified in Section C.3.a. Changes in offsite support services could include changes to the methods, structures, systems, or equipment used by the individuals assigned to implement actions after a design basis event or accident occurs that adversely affect the human performance of those individuals.

The objective of the PMRP is to help ensure that the FFD program remains effective over time as program changes are implemented or substance abuse patterns change among the individuals subject to 10 CFR Part 26. An FFD program would remain effective if FFD performance data, reviews, and audits demonstrate that the licensee or other entity continues to meet the 10 CFR 26.23 performance objectives and adverse trends are not occurring that exceed established thresholds for identified performance measures. The PMRP should help maintain FFD performance at levels comparable to the historic FFD performance levels established by LLWR and Category I SNM facilities.

The PMRP framework is based, in part, on 10 CFR 26.41, “Audits and corrective action,” 10 CFR 26.415, “Audits,” 10 CFR 26.717, “Fitness-for-duty program performance data,” and 10 CFR 26.719, “Reporting requirements”; performance-based requirements in 10 CFR Part 50; and NRC guidance. These regulations and guidance are listed below to inform the licensee or other entity of regulatory requirements that are similar to elements within a PMRP. The licensees and other entities that must implement a PMRP could communicate with those that are now implementing these requirements to learn of operating experience to help in the development and implementation of the PMRP. The following performance-based requirements may have generated operating experience that could inform the development of the PMRP: 10 CFR 26.41(a); 10 CFR 26.41(b); 10 CFR 26.415(a) and (b); and 10 CFR 26.717(c) and (d).

The licensee or other entity can review the performance monitoring programs under 10 CFR Part 50 to inform its PMRP. Two such programs are 10 CFR 50.48(c)(2)(vii), which allows the use of performance-based methods to select fire protection program elements and establishes an NRC review and approval framework, and 10 CFR 50.65, which establishes the requirements for monitoring the effectiveness of maintenance at LLWRs.

The Reactor Oversight Process (ROP) is the NRC’s program to inspect, measure, and assess the safety and security performance of operating LLWRs and to respond to any decline in their performance. Licensees and other entities can find information on ROP program elements and performance monitoring considerations at https://www.nrc.gov/reactors/operating/oversight.html. For example, the information at this website discusses measuring nuclear power plant performance; the use of performance indicators and how the NRC assesses plant performance through inspection; enforcement of NRC requirements; and communications and making information available to the public. The inspection of FFD programs is in the Security cornerstone of the Safeguards strategic performance area and could involve the cross‑cutting areas of human performance, problem identification and resolution, and safety-conscious work environment.

NUREG/BR-0303, “Guidance for Performance-Based Regulation,” issued December 2002 (Ref. 17), provides information on the elements the NRC uses to establish a performance-based regulatory framework. It states, in part, “Performance-based approaches focus primarily on results. They can improve the objectivity and transparency of NRC decision-making, promote flexibility that can reduce licensee burden, and promote safety by focusing on safety-successful outcomes.”

The PMRP is designed, in part, to address the scenario in which a licensee or other entity meets all applicable 10 CFR Part 26 requirements, and its rate or number of FFD policy violations continues to increase. Although 10 CFR Part 26, Subparts B through K, have many audit-related requirements, no requirement compels a licensee or other entity to evaluate, for example, the question, “What random testing positivity rate is considered unacceptably high, such that the licensee or other entity no longer meets a 10 CFR 26.23 performance objective?” The PMRP requires the licensee or other entity to evaluate the random testing positive rate (and the other quantitative performance measures) annually, measure its performance data against its threshold (which was established based on site, fleet-level, and industry performance data), and assess whether corrective actions should be implemented. Licensees and other entities implementing Subpart M should consider the total risk associated with the population of individuals subject to the random testing program but who were not tested (see “Testing Rates and Deterrence under Subpart K FFD Program” (Ref. 18)).5

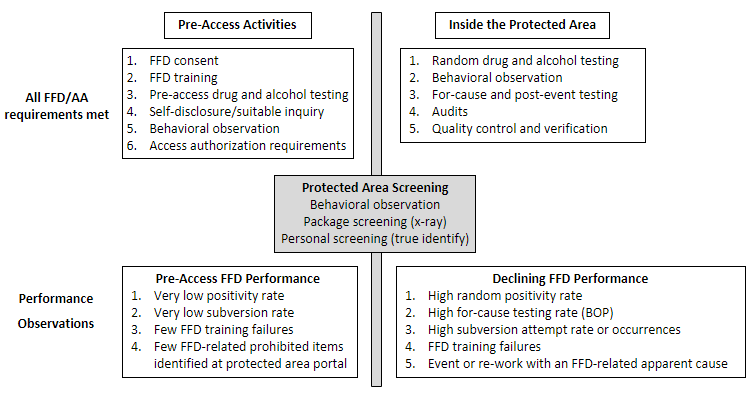

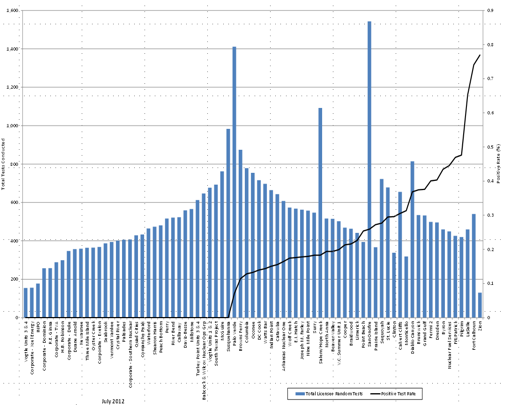

As a second example, a licensee or other entity identifies an increased number of individuals demonstrating signs of impairment while they are allowed unescorted access to the facility. A cause could be that a particular element of the pre-access screening process is not as effective as it once was. For example, the process is not identifying individuals who are subverting the testing process, or suitable inquiries are not identifying potentially disqualifying FFD information (PDI).6 This assessment of pre-access screening and an increased occurrence of FFD policy violations identified through random testing could provide information for the licensee or other entity to assess the safety culture of its staff (see the NRC’s Safety Culture Policy Statement (Ref. 19)).7 Figure 1 presents an example of declining FFD performance when pre-access or the protected area portal area performance does not correlate to FFD program performance inside the protected area.

FFD performance levels established by LLWR facilities and Category I SNM facilities provide a model for effective FFD program performance and performance measures. To maintain an effective FFD program, the PMRP regulations in 10 CFR 26.603(d) require that the licensee or other entity measure its performance and compare it to its past performance and its fleet-level and industry performance. If the data in a particular performance measure meets established by the licensee or other entity, corrective actions would be required to restore performance. Unlike audits that provide a discrete assessment at a particular place and time, the PMRP enables an organization to continuously assess its FFD program as it receives performance data.

The PMRP requirements do not compel a licensee or other entity to continuously improve performance. For example, a licensee or other entity is not required to continuously work to lower positivity rates to achieve zero positive test results or no subversion attempts. The PMRP requires corrective actions only when thresholds are met. Based on discussions within the NRC’s Safety Culture Policy Statement, the licensee’s or other entities’ instructions for PMRP implementation could:

enable continuous assessment;

ensure the program and corrective actions are timely implemented and verified as being effective; and

communicate performance and successes to the staff and other stakeholders and hold the staff accountable for performance.

Figure 1. FFD Declining Performance: Pre-access Performance versus Protected Area Performance

However, nothing prevents a licensee or other entity from seeking to improve FFD performance. Such initiatives should be documented to inform any future program change, auditor, or NRC inspector, for example, as to the reason for the initiative and the baseline performance level at the time of the change. As an example, a licensee or other entity decides to implement drug screening using hair as the biological specimen for a specific group of C/Vs performing nonroutine but safety-sensitive maintenance or engineering design changes. The use of hair screening would provide additional assurance that the contracted workforce is trustworthy and reliable as demonstrated by their avoidance of Schedule I or II drugs as classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration.8 This would be considered as a licensee or other entity initiative to enhance the pre-access testing process for a specific group of individuals and the licensee or other entity could suspend this initiative without incurring a reduction in FFD program effectiveness.

As discussed in the Commission white paper “Risk-Informed and Performance-Based Regulation,” dated March 1, 1999 (See Ref. 20) one of the attributes of a risk-informed, performance-based regulation is the incorporation of safety margins. The Commission stated that, in a performance-based regulatory framework, the failure to meet a performance criterion, while undesirable, will not in and of itself constitute or result in an immediate safety concern. In this construct, margin can be the difference between a baseline level of performance (e.g., a required level of performance) and the actual level of performance above the baseline. Therefore, a licensee’s performance can decrease and the amount of margin would correspondingly decrease, yet the licensee’s performance could remain in excess of the required level of performance. Margin enables flexibility in program implementation because it allows variations in FFD performance above the baseline level of performance; this adds realism to the PMRP. Figure 2 illustrates FFD margin.

Margin within the FFD program is both quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative margin is the operating space under the licensee- or other entity-selected threshold for the particular performance measure where the threshold is quantitative, developed from FFD performance data, and indicates when margin is becoming too small. Qualitative margin within the FFD program is established from licensee and other entity implementation of the 10 CFR Part 26 requirements that establish defense in depth and by the licensee’s and other entity’s policies and procedures that go above the minimum regulatory requirements.

FFD qualitative margin is established from the FFD program elements that provide defense in depth above the assurances gained through performance monitoring of FFD policy violations and other quantitative indicators of FFD program performance (e.g., identification of PDI). These FFD program elements are PMRP qualitative reviews in 10 CFR 26.603(d)(1)(iv)(A) though (C); audits under 10 CFR 26.607(c)(4) and (e) and 10 CFR 26.615; self-disclosures under either 10 CFR 73.56 or 10 CFR 73.120, which can be used in the quantitative performance measure for PDI as listed in Tables 1 through 4; suitable inquiries under 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart C, if applicable, and either 10 CFR 73.56 or 10 CFR 73.120; protection of sensitive information under 10 CFR 26.611, “Protection of information;” fitness determinations under 10 CFR 26.619, “Suitability and fitness determinations,” or 10 CFR 26.189, as applicable; and the use of HHS-certified laboratories under 10 CFR 26.607 or 10 CFR 26.31, “Drug and alcohol testing,” as applicable.

Qualitative margin should not be used as an excuse to justify no action for exceeding a quantitative performance measure threshold. For example, if the random testing positivity rate is set at 1.0 percent for short-term C/Vs, and the CNP plans for a large influx of C/Vs to perform maintenance and expects the random testing positivity rate to go up because the C/Vs do not have a history of working in the nuclear industry, the random testing positivity rate threshold should not be increased. The threshold should remain as is, and the licensee or other entity should help ensure that the C/V workforce is fit for duty and trustworthy and reliable during their pre-access process and while subject to the random testing process This guidance is consistent with the ROP performance indicators.

The number and significance of occurrences in which an individual’s fitness, trustworthiness, or reliability was a root or contributing cause to an event or condition could inform a licensee’s or other entity’s assessment of FFD margin within the PMRP. For example, a licensee or other entity should assess quantitative margin if substantial rework or increased quality assurance and quality verification findings were attributed to a number of individuals who were subsequently identified as being in violation of the FFD policy, yet the threshold for the FFD policy violation performance measure was not exceeded. Additionally, qualitative margin should be assessed if these same individuals cause an SSC to be inoperable and the inoperable condition was not identified during post-maintenance testing; in this case, the defense in depth established to return an SSC to an operable condition was insufficient to identify the SSC performance deficiency. Other indicators of decreased margin could include the following: declines in FFD training scores, increased occurrences of PDI after an individual has been granted unescorted access to the protected area, and recurrent MRO or laboratory performance deficiencies. If the licensee or other entity determines that FFD margin has decreased based on the number and significance of events, then the performance measure should be evaluated even though a threshold may not have been exceeded. Since there is margin built into a licensee-established performance threshold, licensees should use the margin to strike a balance among the following: (1) managing an effective performance‑based FFD program, (2) involving management in the consideration of how qualitative factors (e.g., audit findings, staff size) may influence FFD performance assessments, and (3) issuing corrective actions when FFD data indicate a trend toward degraded performance.

Licensees and other entities should define acceptable performance in their PMRPs in terms of the performance standards in 10 CFR 26.23. For example, the following illustrates the relationship between the performance measures in Table 1 and the 10 CFR 26.23 performance objectives.

The behavioral observation performance measure relates to 10 CFR 26.23(a), (b), (c), (d) and (e).

The identification of disqualifying information performance measure relates to 10 CFR 26.23(a) and (c).

The identification of prohibited FFD items performance measure relates to 10 CFR 26.23(a), (b), (c), and (d).

The FFD policy violation performance measures for licensee employees, C/V, and labor category relate to 10 CFR 26.23(a), (b), (d) and (e).

Licensees and other entities are in an excellent position to define and measure success. The licensee or other entity could assess whether its facility is sited in a geographical location that may be more prone to substance abuse, will be operated using a large C/V workforce, or will be located in a community that does not have ready access to consistent mail services or medical or clinical professionals or clinics, which may challenge site specific implementation of FFD program requirements. Unless new to 10 CFR Part 26 implementation, the licensee or other entity knows its site‑specific and fleet-level performance, if applicable. Furthermore, the licensee or entity would be aware of its audit findings, changes to protected area portal area monitoring and screening, if applicable, the scope of its FFD training program, and other site‑specific FFD program elements.

The performance measures and thresholds in this guide are designed to help monitor important FFD program elements and are based on FFD performance information submitted by LLWRs and Category I SNM facilities to the NRC since approximately calendar year 2009 through the agency’s reporting requirements in 10 CFR 26.417(b)(2) and 10 CFR 26.717. The NRC maintains each FFD program performance report submitted to the agency in its Agencywide Documents Access and Management System (ADAMS). The NRC evaluates the information in these performance reports annually. Reports submitted under 10 CFR 26.417 and 26.719 inform the NRC of HHS-laboratory performance issues and specific FFD program weaknesses and FFD policy violations. NRC inspectors also receive these performance data. The public may search for this data in NRC ADAMS by searching for NRC Form 891, “Annual Reporting Form for Drug and Alcohol Tests.” This search process can be used to view FFD-related events reports under 10 CFR 26.719.

A review of this operating experience and the NRC-issued violations related to FFD shows that LLWRs and Category I SNM facilities have historically met the 10 CFR 26.23 performance objectives and that this FFD performance has contributed to public health and safety and the common defense and security. The data demonstrate low random, for-cause, and post-event positivity testing rates in safety-sensitive labor categories subject to 10 CFR Part 26 (and other safety-sensitive industries)9 and very few abnormal conditions (e.g., plant operational occurrences, human errors, human-related accidents, and rework) caused by human impairment (see Ref. 21, Ref. 22, and Ref. 23). Furthermore, since issuance of the 10 CFR Part 26 final rule in 2008 (Ref. 35) there has been only one violation of the 10 CFR Part 26 requirements that had a significance determination of greater than green.10 Also, very few occurrences have been brought to the attention of the NRC in which licensees or other entities acted to remove individuals from NRC-licensed sites because the individuals caused or could have caused a significant condition adverse to safety, security, or quality or were acting in manner that could harm themselves, others, or the facility. Therefore, the FFD regulatory framework, its implementation, and record of performance in the LLWR and Category I SNM facilities communities have contributed to the (1) deterrence of undesirable human actions that may erode the Commission’s defense-in-depth regulatory framework and (2) detection of individuals who may have been or were impaired or determined to be not trustworthy and reliable. Based on operating experience, past FFD program success within the LLWR fleet includes, at a minimum, the following FFD program characteristics:

Effective training on the FFD policy and procedures is demonstrated by test results from the administration of a comprehensive test.

A signed consent is completed and a pre-access drug and alcohol test with negative test results is verified before an individual is granted unescorted access to the protected area.

All individuals provide complete and accurate information in a self-disclosure, and an effective suitable inquiry is performed.

Random drug and alcohol testing is conducted at an annual random testing rate greater than or equal to 50 percent for the population of individuals subject to testing and there is no prior notice to report for random testing. Notification to test should be made only when an individual (including FFD program personnel) is in a work status and has the time to report to the collection site within the time-to-report metric established by the licensee or other entity. Random testing is conducted during all shifts and on all days as described in this guide. Following completion of the random screening with a negative indication or test (meaning that the test result was obtained from an HHS‑certified laboratory and was evaluated by the MRO), the individual is immediately placed back into the random testing pool.

All individuals participate in the behavioral observation program (BOP), are subject to behavioral observation, and report all FFD concerns to the representative designated by the licensee or other entity. The BOP includes all individuals subject to 10 CFR Part 26 whether working onsite or remotely.

All individuals are held responsible for being fit for duty, trustworthy, and reliable, and they are empowered to report FFD concerns about themselves (e.g., fatigue or adverse effect from the use of a prescription medication) or others without retaliation.

All individuals who indicate a presumptive positive test result on an initial drug or alcohol test, show signs of physiological or psychological impairment, demonstrate characteristics of being untrustworthy or unreliable, or act or threaten to act in a manner contrary to plant or human safety and security are immediately removed from all access to protected areas, SNM, and sensitive information, and the duties and responsibilities making them subject to the FFD program. If confirmed to have violated the FFD policy, these individuals must be issued an FFD‑required sanction under 10 CFR 26.610, “Sanctions,” or 10 CFR 26.75, “Sanctions”; should be evaluated medically, clinically, or both before returning to duty under 10 CFR 26.619 or 10 CFR Part 26, Subpart H; and should be subject to FFD retraining.

The FFD program personnel timely updates site-specific FFD performance data to enable continual assessment and prompt communication of results to management for consideration of corrective actions.

The FFD program personnel and MRO perform a timely review of drug and alcohol test results, promptly remove individuals from the workplaces if PDI about the individual has been identified or the individual is found with a prohibited FFD item (e.g., a substance that could be used to subvert a drug test, a beverage or consumable containing alcohol, or consumable containing marijuana (specifically delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ-9 THC)11 or cannabidiol)), and communicate with HHS-certified laboratories and forensic toxicologist(s) on test result discrepancies, program weaknesses, and proposed program changes.

The workplaces and individuals subject to 10 CFR Part 26 are free from the presence and effects of alcohol and illegal drugs, and that training informs individuals subject to 10 CFR Part 26 of other potentially impairing substances like illegal substances, illegal drugs, and illicit substances.

All sensitive information is controlled to prevent unauthorized disclosure.

Privacy and due process are effectively afforded to all individuals.

Applicants, Newly Licensed Facilities, and Unique Facilities

During the licensing application phase of a 10 CFR Part 53 facility, the applicant is required to provide FFD program information to the NRC. This information includes, in part, the initial performance measures and thresholds the applicant plans to use to assess FFD program performance when the program is first implemented. Since this PMRP is new for the licensed facility and program implementation has not yet occurred at the site, there is no historical site-specific FFD performance data available for the licensee or other entity to use in its PMRP. In this case, the FFD performance data may be gathered from the fleet-level program, if available; LLWR facilities; and other 10 CFR Part 53 facilities.

Unique sites should obtain data from comparable sites. A comparable site is one that may be similar in design, operation, and the size of the staff that is subject to 10 CFR Part 26; may have a comparable ratio of licensee employees to C/Vs; and may be in a comparable location to that of the facility being licensed. Assessing the licensee employee to C/V ratio is important because operating experience from the LLWR fleet demonstrates that C/Vs result in about 4 times as many drug and alcohol positive test results as that of licensee employees and contribute to more than 97 percent of all subversion attempts.12 Understanding the location of the facility may be important because of differences in societal substance abuse profiles. For example, local geography, demographics, and other similar factors may contribute to the substance abuse profile for a facility. Licensees or other entities hiring C/Vs from communities surrounding the NRC-licensed facility may therefore experience differences in drug and alcohol positivity rates based on the location of the facility.

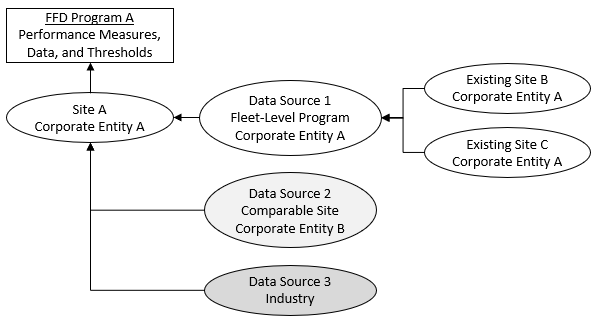

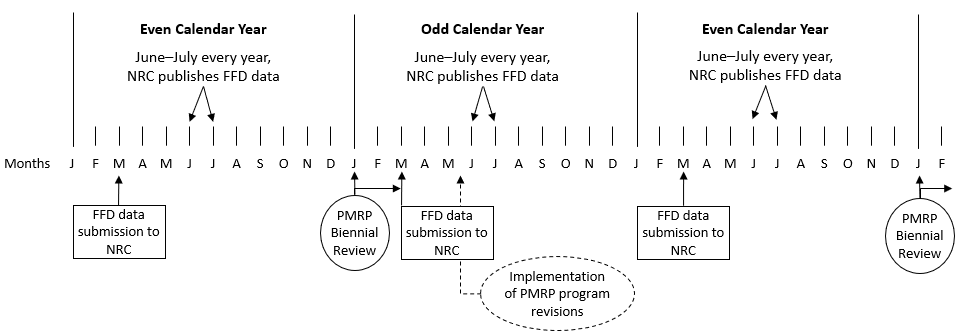

Figure 3. Data Sources for the PMRP

All Facilities Must Gather Data for the PMRP

Figure 3 shows several potential sources of data. As a first step, the licensee or other entity would use FFD performance data generated from the site and fleet-level program performance. Based on operating experience, a dataset from a fleetwide set of policies, procedures, training curriculum, and audit plans would enhance the effectiveness of performance comparisons. A fleet-level FFD program may also attempt to use the same C/Vs to accomplish work at all its sites, which could contribute to consistently effective FFD performance.

The second source of data the licensee or other entity should use is FFD performance data from comparable sites that are operating under a different FFD program implemented by a different licensee or corporate entity. This dataset could be relatively small compared to that of the LLWR community; however, it could provide a baseline of performance to inform the licensee’s or other entity’s measures and thresholds. Furthermore, if the 10 CFR Part 53 facility and the comparable sites have a very small population subject to the FFD program, they might enter into a drug testing consortium, which could be comparable to a fleet-level FFD program. The use of a drug and alcohol testing consortium could enhance FFD program effectiveness and enable implementation consistency across the sites within the consortium.

The third source of FFD data would be industry FFD performance data. As discussed in regulatory position C.5.d, operating experience shows generally low positive testing rates for drug and alcohol testing across the LLWR industry and the Category I SNM facilities when compared to other safety‑sensitive industries. This 10 CFR Part 26 industry performance level helps licensees and other entities meet the 10 CFR 26.23 performance objectives and helps justify using past performance to inform a licensee’s or other entity’s PMRP.

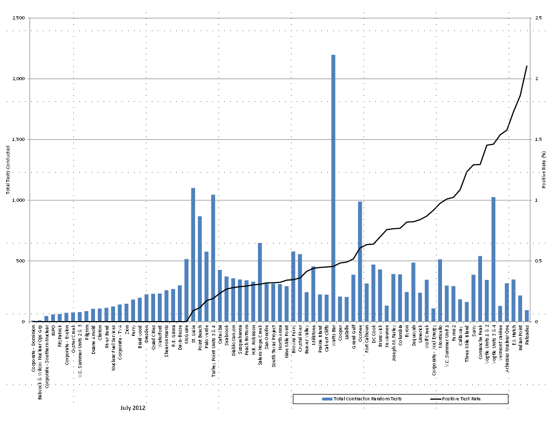

Figures 4 and 5 present historical data from the LLWR and Category I SNM facilities and illustrate that individuals should not immediately conclude that, because a site appears to be an FFD performance outlier, the performance at that site was unacceptable. Performance is a function of the activities occurring at a particular site, such as refueling or maintenance outages; engineering design changes; labor sources; total staff size; ratio of licensee employees to C/Vs; geographical location; and safety culture. For example, if the site has a large influx of C/Vs to perform a maintenance outage, then the pre-access, random, for-cause, post-event, and subversion testing rates may increase because the contracted workforce may not share the safety culture usually present at the site. In figures 4 and 5, the vertical bars represent the total number of licensee employees or C/Vs who received a random drug and alcohol test as measured from the left “y” axis; the black single line is the positivity rate at the NRC‑licensed facility as measured from the right “y” axis; and the “x” axis is the name of the facility. Calendar year 2011 performance data and site names are presented here for illustration to demonstrate relative FFD performance and should not be used in a PMRP.

Figure 4. Random Testing by Site—C/Vs (Calendar Year 2011)

Figure 5. Random Testing by Site—Licensee Employees (Calendar Year 2011)

Data Reporting and Quality

In 10 CFR Part 53, the NRC requires licensees and other entities to submit FFD performance data, either under 10 CFR 26.617(b)(2) or 10 CFR 26.717(e), in accordance with the requirements in 10 CFR 26.11, “Communications.” Since calendar year 2014, the entire LLWR fleet has used NRC Form 890, “Single Positive Test Form” (Ref. 24), and Form 891, “Annual Reporting Form for Drug and Alcohol Tests” (Ref. 25), to report FFD performance information through the NRC’s Electronic Submissions System, General Submission Portal. This has resulted in a large FFD database of performance information that is publicly available in ADAMS and available for incorporation into a PMRP.

Licensees and other entities under 10 CFR Part 53 are required to use NRC-provided forms for the submission of performance data to the NRC. These are NRC Form 893, “10 CFR Part 26, Subpart M, Single Positive Test Form” (Ref. 26) and NRC Form 894, “10 CFR Part 26, Subpart M, Annual Reporting Form” (Ref. 27). Licensees and other entities may familiarize themselves with the instructions posted on the NRC website https://www.nrc.gov/ at “Electronic Submittals Application” located at the bottom of the home page. Licensees or other entities under 10 CFR Part 53 may also submit fatigue management information to the NRC using NRC Form 892. “Annual Fatigue Reporting Form.”

Licensees and other entities also maintain FFD data for their site or sites. These datasets are not publicly available. Licensees or other entities may control FFD performance information collected from 10 CFR Part 26 implementation as “business sensitive”; however, 10 CFR 26.617(c) requires them to share this information with 10 CFR Part 53 licensees and other entities. Information could be shared for the biennial PMRP, audits, and authorization determinations. When sharing occurs, it should be done in good faith and within a reasonable time to support PMRP implementation. Private or personally identifiable information (PII) should not be shared unless it is needed to meet a 10 CFR Part 26, 10 CFR 73.56, or 10 CFR 73.120 authorization requirement. Information sharing should include any site-specific activities or considerations within the data period that would inform the shared dataset, performance measures, or thresholds. The following activities or considerations should be assessed when reviewing FFD performance information from other sites:

Was a different drug testing process implemented or biological specimen used?

Was a different panel of drugs and drug metabolites or cutoffs used?