E-Commerce Exploratory Interviews for AIES

Attachment K - E-Commerce Exploratory Interviews for AIES.docx

Annual Integrated Economic Survey

E-Commerce Exploratory Interviews for AIES

OMB: 0607-1024

Attachment K

Department of Commerce

United States Census Bureau

OMB Information Collection Request

Annual Integrated Economic Survey

OMB Control Number 0607-1024

E-Commerce Exploratory Interviews for AIES

September 30, 2024

Cognitive Testing Support Project: Final Report on Exploratory Interviews of the e-Commerce economic activity for the Annual Integrated Economic Survey (AIES)

Final Report

Prepared for

Economy-Wide Statistics Division

Economic Statistics and Methodology Division

The U.S. Census Bureau

Prepared by

Y. Patrick Hsieh, PhD, Katherine Blackburn,

and Chris Ellis

RTI International

3040 E. Cornwallis Road

Research Triangle Park, NC 27709

The Census Bureau has reviewed this data product to ensure appropriate access, use, and disclosure avoidance protection of the confidential source data (Project No,-P-7530157, Disclosure Review Board (DRB) approval number: CBDRB- FY25-ESMD009-002).

Contents

Section Page

1. Introduction 1-1

2. Methodology 2-1

2.1 Goals And Research Questions 2-1

2.2.1 Population of interest 2-1

2.2.2 Participant recruitment 2-1

2.2.3 Debriefing interview protocol and procedure 2-3

3. Findings from the Debriefing Interviews 3-1

3.1 Previous Research on e-Commerce Activities by Census Bureau 3-1

3.2 How Businesses Define e-Commerce Activities 3-2

3.2.1 e-Commerce activities involve a point of sale online 3-2

3.2.2 Difficulties in defining e-Commerce activities 3-3

3.2.3 Varying industry-specific considerations of e-Commerce activities 3-5

3.2.4 Scope impact on e-Commerce definition 3-9

3.2.5 Does the business conduct e-Commerce activities? 3-10

3.3 Review of the Current AIES e-Commerce Question 3-10

3.3.1 Reactions to question text without instruction 3-10

3.3.2 Reactions to question text with instructions 3-14

3.3.3 Scope impact on e-Commerce definition 3-27

3.3.4 Visibility of instructions 3-28

3.4 e-Commerce Record-Keeping Practices 3-29

3.4.1 Levels of e-Commerce records and tracking 3-29

3.4.2 Data availability impacts understanding of e-Commerce 3-39

3.4.3 Accessibility of e-Commerce records 3-41

3.5 Recommendations and Next Steps 3-44

3.5.1 Recommendations for the AIES question text 3-44

3.5.2 Recommendations for future research 3-47

4. Concluding Remarks 4-1

Appendix A. Exploratory Interview Protocol A-1

Appendix B. Current AIES e-Commerce Question B-1

Exhibits

2-1. Sample Characteristics and Recruitment Outcomes 2-2

3-1. Amount of e-Commerce Activities Reported by Participants 3-9

3-2. Current AIES e-Commerce Question Text 3-11

3-3. Current AIES e-Commerce Question Text Instructions 3-15

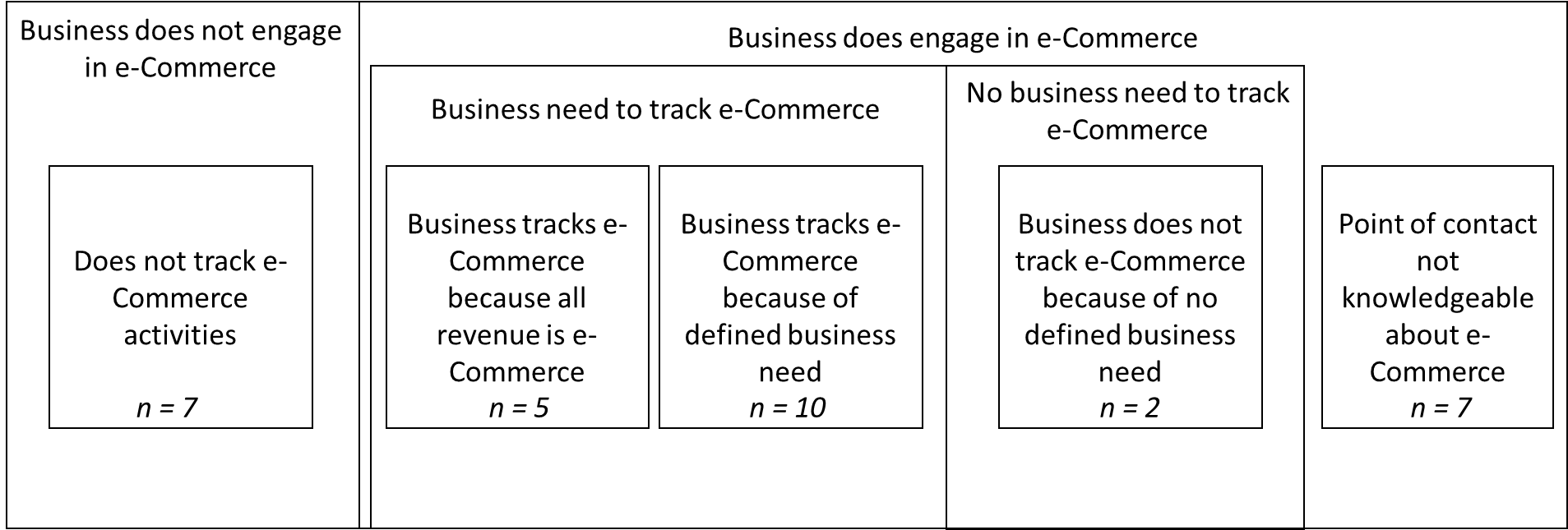

3-4. Types of Businesses Tracking e-Commerce Activities 3-30

3-5. Tyes of Businesses Tracking e-Commerce Activities by Non-profit versus For-profit Status 3-31

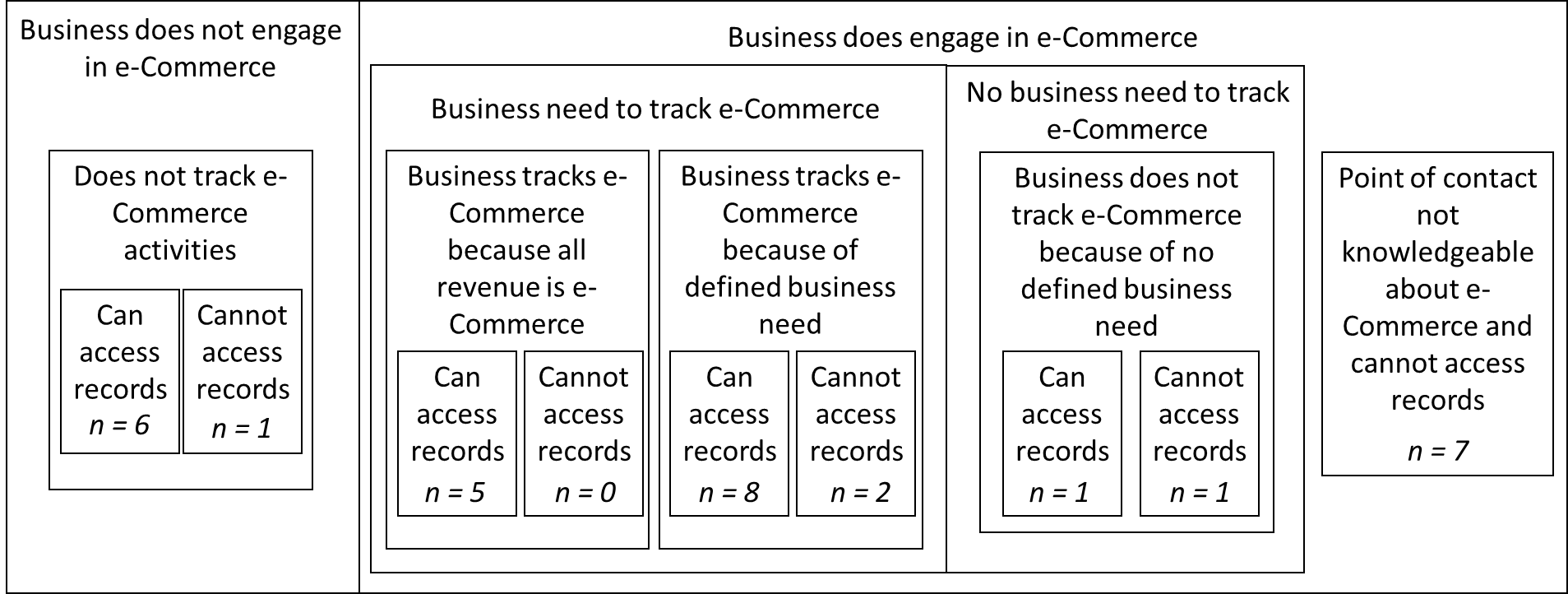

3-6. Accessibility of Records by Types of Businesses Tracking e-Commerce Activities 3-42

The Annual Integrated Economic Survey (AIES) is a re-designed survey to integrate and replace seven existing annual business surveys into a single streamlined instrument. The goals of the AIES redesign are to provide an easier reporting process for businesses, collect better and more timely data, and reduce costs for the U.S. Census Bureau through more efficient data collection. Designed to be conducted annually, the AIES will provide key yearly measures of economic activity, including the only comprehensive national and subnational data on business revenues, expenses, and assets.1

As part of the research effort for improving AIES, the Census Bureau contracted RTI International and Whirlwind Technologies, LLC, to conduct exploratory interviews with respondents who completed the AIES web instrument to survey and document the record-keeping practices and common verbiage for e-Commerce economic activity for future iterations of the AIES. This interviewing represents an additional research methodology to explore mis- and under-reported content on the AIES specific to e-Commerce. From the interview feedback, the project team was able to explore the record-keeping practices and data accessibility related to e-Commerce activities and how such practices reflected opportunities and challenges in measuring e-Commerce activities in the AIES context.

This report summarizes that effort, thematic research findings, and ensuing recommendations for future research.

This qualitative study explored the reporting experiences of AIES respondents, focusing on their definition of e-Commerce business activities, their record-keeping practices and data accessibility related to e-Commerce activities, and their reactions to the wording and definition of the e-Commerce question in the current AIES. The findings assess how record-keeping practices and data accessibility related to e-Commerce activities may reflect varying definitions of e-Commerce activities and subsequent considerations of the need to track such activities to support core business functions. The findings from the exploratory interviews will enable the Census Bureau to consider further research directions and potential designs for updated survey questions to measure e-Commerce activities. This study contributed to the continuous efforts by the Census Bureau to improve the AIES further.

The population of interest for debriefing interviews consisted of businesses that completed the AIES instrument after April 1, 2024. Because of the rapid turnaround needed to meet the debriefing interview schedule, only businesses for which the Census Bureau had an email address and phone number in the dataset were eligible for this study. Census Bureau staff from the Economy-Wide Statistics Division (EWD) provided the project team with a sample list of businesses that completed the AIES instrument on a rolling basis throughout the debriefing interview data collection period. This sample list was used to contact potential respondents.

In addition to contact information, the EWD staff were also able to append to the recruitment file several key business characteristics, including the total number of establishments, North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code, whether the business had establishments in Puerto Rico, whether the business was in the manufacturing sector, and whether the business reported any e-Commerce revenue. However, these key characteristics were not available for all businesses and were used to track sample diversity of completed interviews rather than for targeted recruitment. The total number of establishments was used to categorize businesses into three different sizes: single unit, small business with less than 10 establishments, and large business with 10 establishments or more. Because of missing NAICS code data, business sector information was confirmed during the exploratory interview.

The goal of participant recruitment was to conduct approximately 30 total exploratory interviews. Consistent with the previous e-Commerce research effort by the Census Bureau, conducting 30 exploratory interviews from a diverse group of businesses was deemed adequate to provide sufficient feedback on the record-keeping practices and data accessibility e-Commerce activities. In April 2024, Census Bureau staff shared the first sample list with the project team to recruit participants for the debriefing interviews. As the project team proceeded to contact and solicit research participation from the sample list, the breakdowns of sectors and business size of completed interviews were also monitored. Only businesses that reported e-Commerce revenue in the 2023 AIES were sampled for participation in this research effort.

Data collection began in June 2024, and concluded in July 2024. The project team contacted 541 sampled businesses and completed 31 interviews; one did not attend their scheduled interview, four withdrew participation during the interview, and another 29 refused to participate. Among the 31 completed interviews, three participants represented a single unit company, 10 participants represented a small company with less than 10 establishments, and 18 represented a large company with more than 10 establishments. Three participants represented a manufacturing company, and another three participants represented a company with establishments located in Puerto Rico. Exhibit 2-1 details the distribution of completed interviews by size of business.

Exhibit 2-1. Sample Characteristics and Recruitment Outcomes

n |

Interview status by type |

||

Number of units |

|||

Single Unit |

Small (<10) |

Large (≥10) |

|

Total sample |

152 |

183 |

206 |

Completed |

3 |

10 |

18 |

No show/withdrew/refused |

6 |

12 |

16 |

Data collection began with the following contact protocol: one email followed by one call, then a second email for all sample members. Because of low engagement and the rapid timeline for data collection, this contact protocol was adjusted to focus primarily on emails, which allowed for a wider reach of potential participants more quickly. All 541 sample members received at least one email communication and 203 were contacted by phone to solicit participation. Following calls, 49 sampled members received either a second email invitation or a second phone call as the last recruitment attempt.

Participant recruitment was challenging due to several factors. Sample members refused to participate in the interview primarily because of the time commitment; many businesses were engaged in end of fiscal quarter activities, and typical points of contact for Census Bureau surveys were overwhelmed with other work. Future data collection efforts with AIES respondents should be sensitive to timing around year- or quarter- end activities and the deadline for tax filing and other regulatory compliance activities of businesses.

Exploratory interviews, as a qualitative method, are typically employed at an early stage in the instrument design and evaluation process.2 Exploratory interviews tend to use a more wholistic approach to ask participants to respond to the exploratory questions or probes in an open conversation. This method is suitable for collecting insights into a theoretical or empirical concept of focus for operationalization for developing survey questions.

Census Bureau staff from EWD provided the project team the following three main research questions for review:

What are the current e-Commerce record-keeping practices of businesses?

What is included or excluded in these records?

What are the differences in record-keeping by firm industry(ies)?

What are the differences in record-keeping by firm size and complexity?

At what level of granularity are these records kept?

How accessible are records of e-Commerce activity?

How easy or challenging is accessing this information?

How many people at the business are involved in maintenance and pulling of e-Commerce records for reporting?

Are there levels of granularity that are more or less accessible for respondents (e.g., establishment level compared to industry or company-wide level)?

How do current e-Commerce record keeping practices inform current reporting practices on the AIES?

What are respondents currently including (and excluding) from reporting e-Commerce for AIES?

How much data manipulation (aggregation, allocation, estimation, and others) do respondents engage in to report e-Commerce for AIES?

What are the factors that determine the decision to report e-Commerce on the AIES?

Based on these research questions, the interview protocol was further revised to enhance the clarity of the debriefing questions and the flow of the protocol.

During data collection, project team survey methodologists conducted all exploratory interviews virtually using Microsoft Teams. Participants were encouraged to join the interviews via the computer so that interviewers could share their screen to review the current AIES question. In a few cases when screen sharing was not possible, interviewers emailed a PDF document with the question text to participants.

Before the interview, participants were asked to review the consent document, which was sent via email. At the start of each interview, the main points of consent were reviewed, and the interviewer confirmed that the participant consented to be interviewed. Additionally, participants were asked to consent to the recording of the interview. If consent was provided, the interviewer began the recording. The interviewer then proceeded with the exploratory interview following a semi-structured interview protocol (Appendix A).

The protocol first included questions that gauged participants’ experience in completing the AIES, how participants retrieved information, participants’ perception of the difficulty of the questions, and what level of burden might be associated with data retrieval and reporting. The first section of the protocol set up an opportunity for interviewers to establish rapport with participants by discussing any problems they faced in responding to the newly formatted AIES. This approach relied on the social exchange of feedback about the AIES in exchange for an in-depth discussion about the e-Commerce activities of participants’ business. The protocol also included questions that asked about the definition of e-Commerce activities of the businesses, and their record-keeping practices and data accessibility for such activities. Lastly, the protocol also included questions that asked about participants’ reactions to the e-Commerce question in the current AIES. Interview length was approximately 45 to 60 minutes, and the study did not offer monetary incentives for research participation.

This section begins by presenting the findings from Module 2 of the interview protocol (see Appendix A), in which participants were asked to define what e-Commerce means to them. Although the purpose of this research effort was not to focus on the definition of e-Commerce because previous Census Bureau research has covered this extensively, the participant-provided definitions are key to the topics of interest: record-keeping practices and data accessibility. After reviewing participant definitions of e-Commerce, the report will outline reactions to the current AIES e-Commerce Question (Module 5) and how the instructions provided do and do not fit with participants’ conceptualization of e-Commerce. The last two parts of this section will cover the key research topics of record-keeping practices and accessibility of e-Commerce records (Module 3 and 4, respectively).

The topic of e-Commerce is one that the Census Bureau has been exploring since the beginning of electronically coordinated commerce. Previous research has shown that e-Commerce is challenging to measure and define for several reasons. Respondents have previously reported difficulties understanding the concept of e-Commerce and lack of access to e-Commerce data. As defined by Fayyaz (2018),3 e-Commerce consists of three aspects—the ordering and delivery process, the nature of the products, and the actors involved—thus leading to a three-prong definition of e-Commerce that consists of the following:

Digitally ordered transactions (i.e., sales conducted over computer networks),

Digitally facilitated transactions (i.e., cross-border trade flows facilitated by online platforms, such as credit card and bank systems), and

Digitally delivered transactions (i.e., services delivered digitally as downloadable products3).

The exploratory interviews from which these findings are reported focus less on the established definitional issues and more on the issues of record-keeping and accessibility of said records. However, each participants’ definition is still key to understanding their reports about their records; participants only reported the records associated with e-Commerce as they understand the concept. Additionally, review of the current AIES e-Commerce question, which participants had responded to in the 2 months before interview, was useful to explore the definitional issues and further understand participants’ records. This research hopes to report an updated perspective on how businesses organize and access records about their e-Commerce activities.

When participants conceptualize e-Commerce, one of the key features is that the point of sale (POS) is online. Other terms that consumers use in addition to “online” are “electronically” or “electronic,” “digital,” and “virtual.” For many businesses, this definition of e-Commerce includes that the POS is remote from the business and taking place through a website, either the business’ own website or a third-party app/website (e.g., DoorDash). This conceptualization maps well onto the first prong of Fayyaz’s (2018) definition that specifies e-Commerce as digitally ordered transactions; however, participants think more about the sale (i.e., when and how customers are paying) rather than placing orders or reservations. One archetype of e-Commerce that many participants think about is Amazon; this business features a primarily online storefront, no in-person interactions, and products delivered remotely to consumer’s homes.

“For me I would immediately think of companies like Amazon, PayPal, eBay, where you buy or sell something online.”

“I would define e-commerce as any transaction that is being entered electronically or online, via a website or an internet portal… I personally have probably like a lot of people, when I think of e-Commerce, the first thing I think of is buying something on Amazon.”

Participants also think about what e-Commerce is not when they define it. These definitions include not in person (e.g., “non-brick-and-mortar sales”) and not with physical cash. One participant specifically excluded bulk purchases to other businesses because they are not ordering through a customer-facing website. Others excluded purchases made by mail or phone and paid by check.

“I would say receiving premiums electronically, not physical cash. The majority of our premium revenue is through our online system. It is electronically transferred; we aren’t handling physical money.”

“But normally, our large customers are not going to order from Amazon, they want a large quantity. If they want to try our [product], then we could do a sample order, and then we would send them special packaged sample quantities that we could send to them for that. And that’s processed differently [than Amazon purchases].”

Participants also understand e-Commerce through what their business offers and how their business operates. They provided several examples of how the business they work for operate when defining e-Commerce, including options to buy online and pick up in store (BOPIS), electronically delivered goods and services (e.g., digital marketing, software, telehealth), and donations for non-profit organizations. Participants whose businesses have more diverse methods of e-Commerce (e.g., BOPIS and ship-to-consumer orders) seem to have a broader definition of e-Commerce, with more inclusive examples of what counts as e-Commerce. Other less common methods that participants considered e-Commerce included in-store purchases made on the business website for delivery to customers’ homes and orders placed via email.

Participants’ definitions of e-Commerce align primarily with the first prong of Fayyaz’s (2018) definition, with a focus on orders placed and paid for online. However, participants struggle to conceptualize business practices that do not neatly fit into the archetype of online retailers like Amazon, especially online reservations for in-person services. Six participants were uncertain whether instances of online reservations for in-person services should be considered e-Commerce because the service itself is provided in person.

“I mean when you go to a Bruce Springsteen concert, I don’t think of that as e-Commerce. If you are purchasing access to a concert in an arena, even though your purchase was done electronically, that doesn’t feel like e-Commerce to me.”

“We have internet transactions, but there is ultimately a service/rental/product that is being delivered…We have half of the e-commerce transaction not the full e-Commerce transaction. We would generate a sale from the golf course. You can designate your tee time on the internet and pay—that would be e-Commerce but only partially because you have to come out and play golf. So, it would only be half the transaction. True e-Commerce…is you buy a product and I send it to you—for example, Amazon or any online retailer.”

“In our particular case it does not apply yet. I think of it as someone goes online and pays for goods or services. We currently don’t have that feature, someone can go online and make a reservation, they come in and pay directly through a face-to-face transaction.”

A complicating factor for some participants is when services are reserved online in advance but payment is only provided at the time the service is provided. When payment is provided in person, participants do not consider this e-Commerce. For example, one participant explained that currently their services are reserved through a website but payment is collected in person, which they would not consider e-Commerce. However, the business is working to store credit cards on file, which would be charged automatically, and the participant considered this as e-Commerce.

“In our particular case [e-Commerce] does not apply yet. I think of [e-Commerce] as someone goes online and pays for goods or services. We currently don’t have that feature, someone can go online and make a reservation, they come in and pay directly through a face-to-face transaction…When the card on file becomes active, I would count it as e-Commerce because it will be part of our compliance, that’s why it is clear because right now all of our transactions are face to face.”

Like with services delivered in person, there is some confusion about BOPIS for goods. Although BOPIS is clearly e-Commerce for some participants, others question whether receiving the product in person can be considered e-Commerce. Five participants centralized the delivery method as key to their definition of e-Commerce. The dominant image of e-Commerce as exemplified by stores like Amazon can sometimes obscure participants’ understanding of e-Commerce when goods are not delivered. One participant who prioritized delivery method in her definition of e-Commerce believed that only products provided via mail to a consumer’s home would count as e-Commerce.

“I think of [e-Commerce] as you place an order online or through the internet and they are mailed to you. I’m not sure what the official definition is. So, I may have answered that we didn’t do e-Commerce, because you have to pick [our product] up in person. I’m just not sure about that…I think our website you can place an order and pick it up. But we’re food, we don’t mail anything back. The only thing would be placing an order online, through UberEats or DoorDash, it’s not like Amazon where it can get shipped out. So, in that sense no [we don’t have e-Commerce].”

“To me [e-Commerce] is internet sales, buying off of the internet without going to a brick-and-mortar store.”

Delivery method can also be a point of confusion for electronically delivered services and products (e.g., software), which map directly to prong three of Fayyaz’s (2018) definition of e-Commerce. One participant who provides digital marketing was conflicted because the work (i.e., photographing, client meetings, editing) happens in person but the final product is delivered electronically:

“It’s confusing to me as we have things that are delivered electronically, but the work is done on-site… I don’t know if what I am doing is e-Commerce. The product might be electronic, but the service is reliant on in-person interactions.”

Several participants were concerned about the “moving line” of what could and could not be considered e-Commerce. As they talked more, they started to wonder whether all transactions could be considered e-Commerce if they were tracked in an electronic system or made with electronic forms of payment (e.g., credit cards, bank transfers).

“If I go to Whole Foods, and I load up my cart, and I pay for it at the cash register. That’s not e-Commerce, right? However, the way I pay at Amazon, is I hold my palm over the thing, and I never take out a credit card. It charges my card based on scanning my palm. That sounds very electronic to me. Where is the line?”

“…at what point would something not be considered e-commerce in our business environment today? Even if someone pays by cash, it’s still getting input into a software and it’s being reported to you that a sale took place. I would probably draw the line if you’re there, even if paying electronic means or apple pay on your phone, I would probably not consider that e-commerce.”

“I guess I’m being too granular about this, but you’re right when does eCommerce start or stop?”

As outlined in Section 2, the sample of completed interviews included representation from diverse business types, each with their own understanding and application of the concept of e-Commerce. This section will highlight the key findings for several industries that may not fit the description of the e-Commerce archetype that many participants had considered, including non-profit organizations, utility companies, and companies with salespeople.

Non-profit organizations

As Census Bureau’s previous research has illustrated,4 non-profit organizations often have unique industry-specific comprehension challenges. When shown questions written with for-profit businesses in mind, non-profit organizations can struggle to understand business terminology (e.g., sales, total revenue, goods or services). Eight participants representing non-profit organizations participated in the current study. Most of these businesses included donations that were remitted electronically in their definitions of e-Commerce. They were more likely to mention electronic funds transfer (EFT) transfer, wire transfer, and automated clearing house (ACH) transfer than for-profit businesses. However, three participants did not initially consider grant funding and electronic donations as e-Commerce. One participant explained why she did not include grants as e-Commerce:

“We do very little e-Commerce because again we are 95% grant funded. Those come through grantor funding source, our services to individuals are free of charge. So that type of business is not what I would consider e-Commerce. I’m not going to the TikTok shop and buying something.”

Non-profit organizations do not fit well into the archetype of Amazon as e-Commerce because their revenue-generating activities may be entirely donation- or grant-based rather than focused on providing goods or services. Further discussion about non-profit organizations is included in Section 3.3.2 in review of the current AIES question.

Applicability for non-retail business models and business activities operated under contracts

There were also interesting e-Commerce applicability issues related to either industry-specific business models of operation or business activities operated under contracts experienced by non-retailers in the current study, such as utility companies, banks or financial services, and companies that lease out space or equipment. Two participants struggled to understand whether going online to pay bills should be considered an e-Commerce transaction. Another business reported that they leased out equipment and did not consider those transactions as e-Commerce, even when the bills were paid via electronic methods by their lessee. However, this company did consider “donations that are coming to us electronically” as e-Commerce activities.

“No, we don’t classify ourselves as an e-Commerce [company]. We do not offer a website to our customers to buy our products. Our marketing department has been handling the business sales of our products. They work out sales contracts with our customers. They will transmit the products to the destined locations for our customers to fulfill the transaction.”

“I think it’s the nature of our business model. It’s not like a person who lives in a residential home goes onto our website and orders in a quantity. We supply it. It’s different than Amazon or Target where you go online and you buy a widget. I think of e-Commerce in that way. Even Etsy—a person can sell individual things. [It’s] transactional. I don’t think of us using websites and customers coming on and buying gas like that or selling it or asking to store it. I mean we have a website but customers don’t go online and select a product and add it to their cart through the payment process in the traditional sense.”

“[Leasing] is not e-Commerce. Some people will choose to pay us as e-Commerce, but I don’t count those as part of our e-Commerce numbers because those companies are making a lease payment in whatever way is most convenient to them. The majority send us a paper check.”

Two participants reporting for banks were also included in this study and had drastically different interpretations of e-Commerce. One of these participants believed all of their revenue could be considered e-Commerce because all of the transactions take place digitally, including all fees earned for the accounts and interest. However, the other participant thought only a small part of their financial service operations could be considered e-Commerce, when the business conducts an internet auction for unsold off-lease vehicles. This participant did not consider the loans (i.e., the financial service) provided for the car dealerships as e-Commerce.

These examples illustrate the difficulties with understanding Fayyaz’s (2018) second definitional prong of digitally facilitated transactions. Even businesses that operate entirely digitally, such as a bank providing loans, may struggle to incorporate these digitally facilitated transactions into their conceptualization of e-Commerce. Participants representing utility companies were unsure whether electronically paid bills should be considered e-Commerce because customers are not placing an order for a good or service. Instead, in this industry, customers use the service and then pay after. Companies that earn revenue through leasing and non-retail companies that sell products or services by contracts (like the oil extraction company are also uncertain whether these transactions should be considered e-Commerce. The final contract and payment may be taken electronically, but negotiations may happen through other means and final payment may be made via check.

Two participants called for the need for industry-specific instructions to assist them when answering questions about e-Commerce. One of the utility company participants began to question whether they should be counting their operations as e-Commerce after further discussion. This participant wanted more industry-specific instructions to help them better understand whether to report their revenue as e-Commerce. One bank noted a similar need for industry-specific wording because the revenue-generating activities for their bank did not map well onto their concept of e-Commerce.

“Maybe that is where more clarification about our specific industry would be helpful. We have residential revenue amount, but is all of it done via e-Commerce? I don’t know. We would have to dig in and look into that for the future. Now that we have discussed that, maybe this does count, but it isn’t in the traditional sense.”

“Well, when you say “activities” what do you mean? Any account that is opened, the origination point is tracked so we know where it originates [online, by phone, physical location]. There are service records as well. We know how many online interactions, how many phone interactions…– when you say “transactions”, it means a lot of things in the banking world. If an account was opened or originates with our client care center, which is our telephone banking area, we can see that. If it originated online, with assistance of our client care center, we could see that. We would identify revenue for those accounts as belonging to electronic.”

Applicability for businesses that operate with salespeople

Another important consideration for defining e-Commerce is commission-based sales or whether salespeople are involved in the transactions. When salespeople are involved, some businesses do not classify those transactions as e-Commerce, even if the sale originated online. Others questioned whether transactions that a salesperson entered electronically into an application or online system should count as e-Commerce or not. The archetype of stores such as Amazon as e-Commerce can prevent participants from clearly mapping their business processes to their understanding of e-Commerce. These participants consider e-Commerce transactions as only those where the customer is interfacing directly with the electronic ordering mechanism, typically a website.

“We will review the orders from our website and coordinate the shipment with our local stores that have the inventory of the item as we received the payment from our website. If the customer orders an item online but then decides to visit our local stores to look at the item and complete the payment, then we will NOT count this transaction as e-Commerce and will select the sales-rep of the store who completed the transaction for the sale.”

“We do not offer a website to our customers to buy our products. Our marketing department has been handling the business sales of our products. They work out sales contracts with our customers.”

“We do have a very small [sales amount] through Shopify [which I consider e-Commerce]. But there is a lot of electronic sales [from the sales reps]. Sales are made via email and then logged electronically. But also [sales rep can] go in person and can make the sales in person and log it in electronically. They will go in the system and put it into the plant to fill the order.”

“No [I don’t consider our wholesale customers e-Commerce]. We have a customer service team that calls the customers and enters it directly into SalesPad.”

Sales mediated through salespeople are not currently explicitly included in Fayyaz’s (2018) definition, and most businesses using salespeople would not include these transactions as e-Commerce. However, some question whether they should be included when the salespeople use digital means for placing the orders.

Another interesting aspect that arose from conversations about defining e-Commerce is that the amount of e-Commerce business activities a business engages in directly impacts how participants define e-Commerce. The impact of scope on the definition of e-Commerce occurred at both ends of the spectrum—both those with very little e-Commerce activities and those who could consider all revenue as e-Commerce. See Exhibit 3-1 for the amount of e-Commerce activities reported by participants.5 Those with very little e-Commerce activities could be confused about whether their business engages in e-Commerce and may omit activities that they do consider e-Commerce simply because they make up such a small amount of total revenue. Conversely, other businesses consider all of their revenue e-Commerce and can struggle to define it because there is no business need to understand what is and is not considered e-Commerce. Instead, for the AIES e-Commerce question, they would report all of their revenue.

“[I forgot about curbside pickup] because it is so small. It was a bigger thing during COVID, and while it is still offered today, it is used minimally.”

Exhibit 3-1. Amount of e-Commerce Activities Reported by Participants

Scope of e-Commerce |

Number of Participants |

All |

5 |

Large |

8 |

Medium |

6 |

Small |

5 |

None |

7 |

One participant believed during most of the interview that her business did not engage in e-Commerce because it made up such a minute part of their total sales. However, when she saw the current AIES question, she did remember reporting the business’s eBay sales as e-Commerce. When thinking about e-Commerce more broadly, she did not initially include these sales because the majority of their business happens as in-person transactions. The impact of scope on a business’ conceptualization of e-Commerce may impact measurement error when small parts of the total revenue are omitted because of limited salience for respondents. Section 3.3.3 will include further discussion of businesses that consider all of their revenue e-Commerce.

As a part of discussing each participants’ definition of e-Commerce, they were also asked whether the business conducts any e-Commerce activities. As detailed in Section 2, all businesses sampled for the e-Commerce debriefing interviews indicated some amount of e-Commerce revenue in the most recent AIES. However, seven businesses stated during Module 2 that they do not have any e-Commerce activities (see Exhibit 3-1). Two participants changed their mind when later viewing the current AIES e-commerce question. Another participant was hesitant about whether they would count their business operations as e-Commerce and had not made a final decision for future reporting by the conclusion of the interview.

When preparing for these interviews, we anticipated that some businesses may reject the idea that they are engaging in e-Commerce; however, we were surprised to find that this was the case for nearly a quarter of the completed interviews. Some of the confusion from these participants comes from the industry-specific concerns outlined previously. Notably, all participants who participated in this study indicated they were the ones who responded to the AIES. It remains uncertain whether their inability to recall their affirmative response about the e-Commerce activities in their AIES reports is due to delegating the question to another colleague within the company or whether there are other underlying factors at play (such as data entry errors). Later sections will continue to detail how these participants navigated their understanding of e-Commerce and whether their business engages in it.

Review of the current AIES e-Commerce question was included as the last module in the interview protocol; however, feedback about the question and its instructions corresponds closely with how participants’ defined e-Commerce themselves. Participants were first shown only the question text and asked about comprehension, then were shown the instructions (see Appendix B). This section will outline reactions to the question text alone as well as to the question text with additional instructions. The later sections will outline how comprehension of the current AIES question impacts ability to report e-Commerce.

When shown the question text alone (see Exhibit 3-2), participants most commonly described the question as asking about electronic sales, including using phrases such as “online,” “electronic channels,” “internet,” “website,” “ordering on an app,” and “virtual.” Most participants focused on the point of sales or the way a customer placed an order, similar to their own spontaneous definitions of e-Commerce. Some participants continued to define e-Commerce by what it is not (i.e., not in-store or brick-and-mortar purchases). A key phrase for participants was “that were ordered,” which communicated the idea of customer orders through electronic means. Some participants also highlighted that the question asks for a subset of total revenue, also described as “income.”

“Of the entire amount of revenue that our company made in 2023, how much was ordered through the internet and was not purchased inside a brick-and-mortar store.”

“The question asked about the total revenue from the product sales from a website.”

“Asking for the dollar value proportionally of the total amount of sales that were generated from electronic sales.”

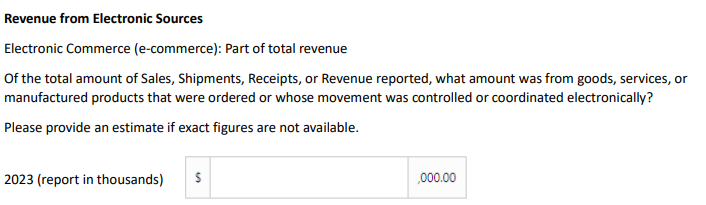

Exhibit 3-2. Current AIES e-Commerce Question Text |

|

The wording “ordered” played a big role for one participant (see Section 3.2.2). This participant originally focused on the delivery method of goods as a key feature of e-Commerce. After reading the question text and seeing the wording “ordered,” she was open to including any transactions where the product was ordered online, regardless of delivery method.

“To me, I would probably have answered with the items from the mobile pay. Because it was ordered online or through DoorDash, which is online, it’s not in person. To order… it doesn’t say delivered, it does say order.”

From the phrase “sales, shipments, receipts, or revenue,” participants focused on either sales or revenue. No participants mentioned shipments or receipts when describing their understanding of the question. In fact, “shipments” may have contributed to some misunderstanding from a participant who included remote delivery as key to her understanding of e-Commerce. This participant specified that she thought the question was asking about “how much was done through online orders, how much was paid through electronically, how much was shipped to someone where you may not know where they are located.” The phrase “shipments” may have reinforced an understanding of e-Commerce as including only transactions where goods are delivered remotely. Another participant also verbalized a dislike of the word “receipts,” sharing, “Receipts is usually bringing in stuff and that wasn’t included at all.”

“This seems like it is asking what is the total sales for online goods.”

“Asking me to separate the sales that are e-Commerce-related from the sales that are the total revenue.”

“I focus on the first part of it with the sales, shipments received and revenue reported. That ties in with your goods, services…. I focus more on that in terms of just meaning overall sales.”

“I would say - anything bought online or bought online and picked up in store. I would think to include that revenue.”

“I interpret this [question] as revenue. I was looking at the revenue that came from [online retailer].”

Another key phrase for participants was “controlled or coordinated electronically.” This phrase was key for one non-profit to understand that the grants they received should be counted as e-Commerce. Although initially this participant believed the non-profit business did not conduct any e-Commerce, she changed her mind after reading the question text and remembered that they did report their grant funding as e-Commerce. Another participant summarized the question as asking about “electronically controlled revenue,” highlighting this as a key phrase to her understanding. One participant liked the specificity of this phrase and said it improved clarity over asking about e-Commerce in general.

“Some of the [grant sources], they don’t mail us a check, you have to go online to a portal and connect that to an account so when they issue a grant, they sent it ACH into your account. For that reason, we did put a number for the answer to that question. It’s not because we provide something online it is because how we receive it…I believe this is the question I was just telling you about, we did put a number in there because it says at the end coordinated electronically, and for some of these grants that is how we receive it.”

However, the phrase “was controlled or coordinated electronically” also contributed to some confusion and misunderstandings from participants. One participant stated throughout the interview that her business did not have any e-Commerce activities.

“None of our goods, services, or products would be controlled or coordinated electronically, even the hotel reservations which would be online. It would still need to be coordinated and controlled in person when someone checks into the hotel.”

This participant did not understand that reservations made online hotel should be considered e-Commerce. Instead, she interpreted the in-person transaction as violating the definition provided in the question, because the payment was not controlled and coordinated entirely electronically. Another participant also noted that the phrase was confusing.

After reviewing only the question text, six participants thought the question was too broad and confusing. One participant felt confused when seeing a reference to “manufactured products” when they do not manufacture anything. Another participant recognized the question needed to be broad based on the wide variety of businesses that would respond to the survey, sharing “I know it is a very broad statement because not everyone does the same thing or collects funds for the same thing.” However, others felt it was so broad that anything could be included as e-Commerce, which could potentially lead to measurement error. This reinforces the idea of the “moving line” of e-Commerce; when participants started to think more about what could be considered e-Commerce, some also started to question whether all their revenue should be considered as e-Commerce.

“The question is so broad that it is going to be very difficult for anybody to say something isn’t eCommerce if you’re thoughtful, as I’m trying to be here.”

“So, to me, because of how it reads, this could be considered ANYTHING that was an order processed electronically, whether it was in our systems, or if they called us, or if it was online. Which is unfortunate, for e-Commerce, it seems like it’s something that’s solely online sales.”

Finally, as a positive, two participants expressed that they liked that the question only asked for industry totals rather than by location. They both stated that it would be extremely difficult and time-consuming to respond to the e-Commerce question by location. As will be discussed in later sections, some of the difficulty in reporting by location stems from lack of records because many businesses do not tie their e-Commerce activities to a specific location.

Industry-specific concerns

Participants reporting for businesses in industries that do not fit neatly into their conceptualization of e-Commerce want industry-specific instructions and wording to help them understand the question better. One participant, whose business offers services that are reserved online but delivered in person, struggled to understand that this source of revenue should be counted as e-Commerce based on the question text alone.

“I am not sure if that [online bookings] would qualify. I don’t know as it is confusing to me. None of our goods, services, or products would be controlled or coordinated electronically, even the hotel reservations which would be online. It would still need to be coordinated and controlled in person when someone checks into the hotel.”

With “services” buried in the middle of the question around a lot of other text, one participant missed it entirely, sharing “I think [the question] is [about] more manufacturing things, selling of things, not providing a telehealth service. I just don’t think it pertains to us.”

Another participant, whose business provides digital software, questioned whether their platform would be considered goods or services or manufactured products. He was unsure whether his business fit into the definition of e-Commerce provided in the question text, even though earlier he answered affirmatively that his business engages in e-Commerce. This issue is compounded by the fact that all of the business’s revenue could be considered e-Commerce, which makes the question more challenging to understand. In the end, the participant was convinced by the second half of the question text, including the phrase “movement was controlled or coordinated electronically” and decided he would report all revenue as e-Commerce.

“I think it needs another [statement] that would be “electronically provided services or physically delivered services” if that is the intention. That’s the whole thing—I don’t know the intention of the writer, but I know that I’m left out. So, I’m guessing its whether you’re interested in my revenue or not for this question…”

As outlined earlier, these participants struggled with comprehension of the second two prongs of Fayyaz’s (2018) definition of e-Commerce which includes digitally facilitated transactions and digitally delivered transactions. Some of these comprehension problems were improved when participants viewed the additional question instructions; however, other issues also emerged.

After responding with their understanding and comprehension of the question text alone, participants were then shown both the question text and instructions (see Exhibit 3-3). After reading the instructions, one-third of participants thought they changed the meaning of the question. In other words, when viewing the question text alone, participants were thinking about a different definition of e-Commerce than what was specified in the instructions. Most who said the instructions did not match their understanding of the question missed specific transactions that should be included as e-Commerce, such as BOPIS or monetary donations. One participant drastically changed her understanding of e-Commerce after reading the question text and instructions. As detailed previously, this participant initially believed that only mailed online orders would be considered e-Commerce. After reading the question text, she believed that all “online orders” should be included, but this was further confirmed when she read the detailed instructions. She incorporated this new information into her definition of e-Commerce and would report about all online orders, rather than only those that were mailed.

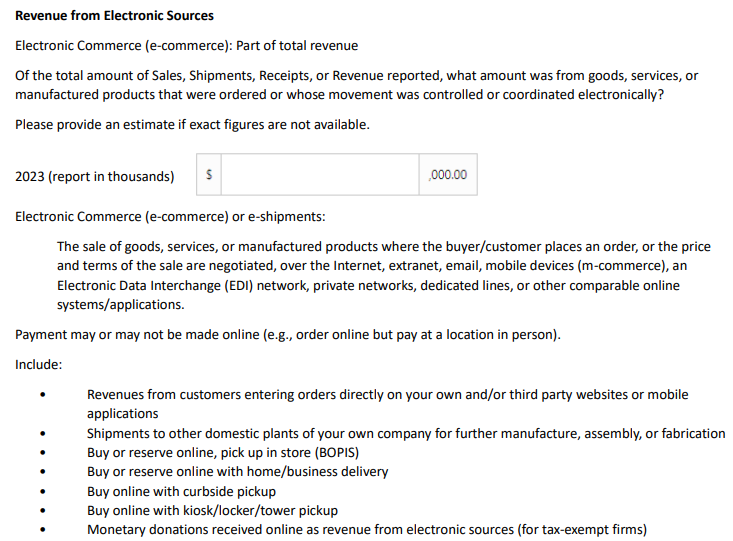

Exhibit 3-3. Current AIES e-Commerce Question Text Instructions |

|

Additionally, after seeing the instructions, eight participants commented they were helpful because the instructions provided further clarification and confirmation about what the question text alone asks for. Two participants appreciated the specifications of what to include but thought the question could also benefit from listing out what to exclude. One participant whose non-profit organization provides services found the BOPIS instruction confusing. She thought it would be more helpful to have what to exclude specified rather than what to include.

“The detail at the bottom gives me more details about e-Commerce or e-shipment. They make more sense now, and they matched my understanding.”

“Matches. I think it drills in…the main emphasis is online, online, online, online, so to me, [the instructions] just drive it home.”

“It matches what I was thinking about, but it provides a lot of clarity on it. It is more descriptive of buying online, what buying online means, shipments…it gives it more clarity on everything you are manufacturing or delivering.”

“I think it is the top bullet point there that is really applicable for us: “revenues from customers entering orders directly on their own or a third party website.” That really helped confirm the information we then reported.”

“When it says pick up in store, so again, does it really include if membership is done online but they come into the office to pay? I’m not sure if that counts. If they give examples, like if they paid with check or cash that should not be included. It would be great to have what should be excluded. It has here what should be included but not what should be excluded. That would make it a little clearer.”

“I think that your includes as part of the instructions now could also have an excludes. I would have written it as “Examples of what to include” or maybe not, but certainly examples of what may be excluded.”

While the instructions were helpful for most participants, five participants found them confusing and wordy.

“This is not helpful… The first paragraph is way too complicated. Again, the survey should be easy for people to understand. This gets into the highly technical information that you want.... Then there is a lot of things here to include.”

“Some of [the instructions] clarified it a little bit more, and others I was like that still doesn’t make sense. So, I’d have to call [Census]. I would just call to make sure that we are understanding it correctly so we didn’t report the wrong figures.”

One participant specifically experienced some confusion about the phrase “was controlled or coordinated electronically” in the question text when read in combination with the instructions. This participant started to question where the “line” was for e-Commerce activities and whether credit card payments should count as e-Commerce.

“The last portion ‘that were ordered or whose movement was controlled or coordinated electronically.’ To me that is confusing because when I think electronically, my brain goes to the swipe for the credit card, so does that include that or no? If I focus more on the online, online, online or the mobile portion of it that helps me with clarity of it versus electronic. There are a lot of electronic functionalities in what we do here that would not count as e-Commerce. To me, I would focus more on online vs in house—that helps me segregate those out.”

Overall, feedback about the question instructions is mixed, with some positive and negative reactions. Next, we will explore specific feedback about the wording and phrases used in the instructions. The rest of the section will outline participant reactions to specific phrases used in the instructions. This feedback may help to better understand how participants’ conceptualization of e-Commerce does and does not match the current AIES question wording.

Payment may or may not be made online

Nine participants commented on the instruction “Payment may or may not be made online (e.g., order online but pay at a location in person).” This sentence stands out to participants because it contradicts the dominant understanding of e-Commerce. As discussed in Section 3.2.1 almost all participants considered e-Commerce transactions to include those that are mediated through an online website where payment is conducted remotely and independently of any physical business locations. The instruction states that payment may be made in person after an order is placed online, which violates the common perception of e-Commerce as remote electronic sales. Five participants found the instruction confusing, with several indicating their surprise that payment in person could be considered e-Commerce. One participant discussed an example of making a reservation online for a restaurant, but then eating in person at the restaurant and paying.

“I think if you order food and you sit down and eat it and you don’t pay for it [online] then that’s not e-Commerce. To me e-Commerce is more you’re ordering, you’re paying, most instances you’re receiving the product online. The one caveat would be curbside or in-store pick up, the convenience is you’re doing everything electronically.”

The idea of paying in-person for a service provided in person violates common understanding of e-Commerce. Many participants struggled to incorporate this instruction into their conceptualization of e-Commerce. However, four participants acknowledged that they could consider these types of transactions e-Commerce but initially would not have thought of this as e-Commerce when thinking about e-Commerce generally nor when reading the question text alone.

“I think it is a little bit more

clear in that, for instance, the line that says “payment may or

may not be made online” that is how our [business services] are

handled. You make a reservation, but I think you end up paying at the

location in the retail

store. So that specifically under this guidance would be included as

e-Commerce. The order was secured via electronic means but you’re

just remitting payment in person. [It’s helpful.] It’s

specific to our business, it’s something that we utilize…[But]

I think when I read and was looking to complete the survey, my mind

immediately went to the platforms I know we have, and not really

diving into the nuance of, from the retail space this specific amount

relates to [business services] that would have been reserved on this

platform…”

“Based off your definition here, it counts. But initially I would not have thought of [making a sale online and paying in-store] as e-Commerce, without reading the definition. I would have thought no.”

Three participants indicated that their business does not have the ability for customers to pay in-store after placing an order online. Online orders require payment at the point in time the order is placed. The instruction did not apply and left them confused about when it could be applicable, especially because the instruction did not align with their conceptions of e-Commerce.

“We don’t have that option. A customer can’t make tender in a store but it ships online. Everything would be done online.”

“Payment may or may not be online. To us payment has to be online, otherwise you are going into a store.”

This instruction about payment being made online or in-person violates how participants’ conceptualize e-Commerce. Although the first prong of Fayyaz’s (2018) definition states “digitally ordered transactions (i.e., sales conducted over computer networks),” participants generally only consider e-Commerce transactions when the point of sale occurs electronically. That is, they consider online payments e-Commerce more often than in-person payments for online orders. The current instruction does not align with participants’ understanding of e-Commerce nor with the question text, which may lead to measurement error.

BOPIS

Related to the instruction about payment that may or may not be made online, participants also reacted to the instruction “Buy or reserve online, pick up in store (BOPIS).” Participants reporting for businesses that provide services highlighted the wording “reserve online” when thinking about how the instruction applies to their business. Like the findings about the phrase “Payment may or may not be made online,” the idea of reserving the service online but paying in person violates many participants’ construction of e-Commerce, which may lead to measurement error.

For example, one participant believed that providing services in person did not count as e-Commerce, even when payment is provided online in advance. She understood curbside pickup as e-Commerce and if her business had any curbside pickup transactions, she would include those in her reporting. However, the defining distinction to her was the difference between goods and services. She believed that receiving goods in person could be considered e-Commerce but providing services in person could not be e-Commerce.

“To me [that instruction is] I had to order online and I had to pay online, that’s what this is saying. If you’re conducting business via an online mechanism, portal, whatever it might be. So, the person who walks into our office and and gives us their credit card for fifty dollars, to me, that would not be e-Commerce… We do [take payment through website] but not for all of our [business services]. The only example of services we provide that we take payment online and deliver the services online is if we did a webinar that they could pay online and services delivered online as well. But for the other example, you literally have to come into our office. All you would be doing is paying via credit card. We are delivering services via face-to-face delivery rather than a product that you could ship to your house or pick up online or at the curb.”

Relatedly, another participant whose business provides services debated whether reservations in advance should be counted as e-Commerce because customers have not committed to any payment or service until they show up in person and are charged. He stated that even with the instructions, he would respond to the question with $0 revenue since he did not believe that these types of transactions constituted e-Commerce.

“It’s a grey area, if you say that if someone orders, by that I mean they go online and get a reservation and know it’ll be $22 but they haven’t committed to anything until they show up. We aren’t going to charge them anything because there has been no service provided. If this was asked today I would say zero.”

As mentioned in Section 3.2.2, this participant made a distinction for e-Commerce between payment in-person and electronically stored credit cards. When their business is able to store credit cards on file and charge the cards automatically for services provided, they would consider that e-Commerce. Currently, the business takes reservations online and completes the payment in person when the service is delivered. This participant struggled with the instructions about reserving online to pick up in store because it violated their understanding of e-Commerce. Another participant stated candidly that if the customers are paying in store, they would not consider it an e-Commerce sale.

These three participants highlight a concern for measurement error when participants read the instructions, but they so thoroughly violate the participants’ understanding of e-Commerce that they may choose to misreport. The way businesses organize their records also impacts reactions to the instructions and whether participants can incorporate the specific instructions into their understanding of e-Commerce. For those who do not track in-person payment for online orders, it is more difficult for them to understand the instruction and, furthermore, almost impossible for them to report on. Further detail about the lack of records reflecting in-person payment for online orders will be discussed in the next section (Section 3.4).

However, one participant found clarity in the instructions and adjusted his understanding of e-Commerce to prioritize how the order was placed and deprioritize how the payment was made. He found the BOPIS instruction helpful to construct a new, broader understanding of e-Commerce.

“[For instances where the [business service] is reserved online and the person comes in and pays in cash,] you are securing the product or service via an electronic means, you’re just remitting payment physically. I would still probably consider that e-Commerce.”

When he focused on in-person payments as just how the payment was “remitted,” he was able to expand his definition of e-Commerce to include both in-person and online payments. This participant also explained that he was able to report these transactions separately because of the way the records are organized around separate POS software systems. It was easier for him to incorporate this idea of in-person payments because the records the company keeps matches this conceptualization.

Electronic Data Interchange

Another phrase that was confusing for three participants was “Electronic Data Interchange (EDI).” For one participant, it was unclear whether an EDI network was the same as the online portals they access to move money. Another participant wondered if the business had an EDI or not, seemingly unfamiliar with the term. One participant was also confused about what an EDI was and thought there should be additional details to explain the term. This term may be dated and not relevant to current business operations.

“In the paragraph right below where you would put a number, ‘an Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) network or a private network’ we do have that in a way. We aren’t buying or selling products to people online, but we do have online portals where money is moved around, but I don’t know if that was the intent.”

“I am more confused after reading this than before… an Electronic Data Exchange Network? Do I have one of those?”

Shipments to other plants

Two participants also identified the statement “Shipments to other domestic plants of your own company for further manufacture, assembly, or fabrication” as confusing because these transactions are not typically considered revenue-generating and thus are not tracked.

“I wouldn’t think of the shipments to other domestic plants as being e-Commerce. I would say the second bullet point doesn’t really make sense to me… it wouldn’t be considered revenue, so it is not tracked. It wouldn’t be something I have access to; the location level would have to provide that if there was anything.”

Additional consideration and research should be given to this instruction to ensure that it is working as intended. The question text asks for a subset of total revenue, but if shipments to other plants are not considered revenue, then this instruction should not be included in the AIES question.

Kiosks

One participant was very confused about how to consider kiosk transactions in the context of e-Commerce. Her business offers fast casual food and includes kiosks in the store; however, she was not confident that this should be considered e-Commerce. Furthermore, there would be no feasible way for her to report kiosk transactions because these are considered in-store sales. More details will be reported in Section 3.4 when discussing record-keeping practices.

“Actually… you know, we have kiosks. So, if they go to the front of the store and purchase through the kiosk, I’m not sure that’s considered e-Commerce… it says buy online with kiosk… if there’s a kiosk in the store and you can swipe your card… I wouldn’t know how to answer that. It says buy online, is it considered online if you are 3 feet from the front register? That one would require more information. If you’re in store and doing it through the kiosk, is that online? Or online and away from the store?”

Differential inclusion of kiosks in reports of e-Commerce revenue may lead to measurement error, but this error may be unavoidable if business records do not allow for easy reporting.

m-commerce

One participant thought the phrase “mobile devices (m-commerce)” was confusing, stating, “What is ‘mobile devices (m-commerce)’ – is that like cell phone usage or iPad? I don’t know what you mean by mobile devices here.” Another participant felt the inclusion of m-commerce needed further clarification on whether orders placed by phone should be included as e-Commerce.

“The only other thing I would say here, because of the inclusion of mobile devices, maybe you need something about clarifying a “call-in” order as opposed to “ordering on your phone” or is that something that would be included here? It is just a point of clarification I would need.”

m-Commerce may have been a more prominent term in the past, but today m-commerce can cause more confusion than clarity because mobile phones are used seamlessly for online transactions.

Monetary donations

Four non-profit organizations shared their reactions to the instruction “Monetary donations received online as revenue from electronic sources (for tax-exempt firms).” Three participants did not initially include monetary donations in their conceptualizations of e-Commerce. One participant received most of their revenue via grants, which they had not initially considered e-Commerce. The instructions helped them understand that grants paid through electronic funds transfer (EFT) should be included as e-Commerce. The other participant who did not initially consider monetary donations as e-Commerce shared the following:

“I wasn’t thinking of monetary donations. That makes it clearer that we need to include that. I think we only picked up the credit card transactions, but maybe it included the [donations].”

However, this participant also had a question about the monetary donations, wondering, “we get donations via stocks… I’m thinking does that apply here? … if we can get more break down for the non-profit, that would be great.” This participant was confused whether other forms of donations should be included or only those made via direct donation.

Conversely, another participant thought that monetary donations were immediately obvious as e-Commerce in the non-profit space.

“For me personally, [monetary donations are] something I immediately associated with [e-Commerce]. We don’t have e-Commerce like a retailer that has an online store like Walmart, but I kind of immediately, when I was thinking about e-Commerce thought about ways people can make contributions online, and that would be e-Commerce for us. So, this [instruction] is really codifying that, but that’s an assumption I had from the beginning.”

However, this participant was previously employed in the for-profit sector and may have a higher level of comprehension than other reporters for non-profit organizations. The risk of measurement error for non-profit organizations is very high if they do not include electronic donations in their report of e-Commerce. The fact that the instruction is hidden may lead to a higher rate of issues since non-profit organizations may read the question text alone, respond $0, and move on to the next question without reading the instructions. The placement of the instructions will be discussed later in this section.

Industry-specific applicability considerations

When reviewing the instructions, several participants called out aspects of the instructions that were not applicable to their business, such as instructions about monetary donations, curbside pickup, manufactured products, and kiosks. Although some participants continued to acknowledge the need for diverse economy-wide instructions, others felt confused and that the question was not applicable to their business at all.

“A lot of those subcategories are not relevant to us. We deliver, customers come and pick up, but we don’t have a kiosk that I’m aware of… The survey is for a lot of businesses, I realize not everything is going to be for us. I do what I can do.”

“I think there are things that are just not relevant to us. Like we don’t have a kiosk/locker/tower pickup option, but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be there because it is probably relevant for someone else. We don’t do monetary donations from customers. I think it is fine and I would just skip the pieces not relevant to us.”

“Down there in the bottom where it says include these things, we don’t fit into those categories.”

“I think it is more manufacturing things, selling of things, not providing an online [business service]. I just don’t think it pertains to us.”

The instructions provided seem to over-represent retail-specific e-Commerce activities, which may come at the expense of other industries, such as utilities, and service industries, such as hotels and telehealth providers. After reviewing the instructions, four participants continued to state they did not engage in e-Commerce and felt the question was not applicable to their business at all.

However, reviewing the question text and instructions made two participants change their mind about whether their business engages in e-Commerce and one participant question whether their business engages in e-Commerce. Both of these non-profit participants originally did not think of donations and grants as e-Commerce when probed unconstrained about the definition. However, after reading the question text and instructions, both believed that grant money received electronically (e.g., through EFT, through Payment Management System, through ACH) should be considered e-Commerce. They also both recalled that they had reported these grants on the AIES e-Commerce question this year. When thinking about e-Commerce in general, these participants did not consider non-profit business activities such as receiving grant money as fitting into the concept of e-Commerce, which could lead to significant measurement error. Furthermore, one participant’s organization only generates revenue through grants while another’s organization generates 95% of revenue through grants. This highlights the potential need for industry-specific instructions that would appear outside of additional help text to assist businesses like these in correctly responding to the e-Commerce question.

The last participant who questioned whether their business does or does not engage in e-Commerce after reviewing the current AIES question was confused about how to apply the instructions to their specific industry (utilities). As detailed in Section 3.2.3, this participant was uncertain whether participants going online to pay bills should be considered e-Commerce when asked about e-Commerce broadly. After reviewing the question text and instructions, this participant continued to try to understand e-Commerce in the context of their industry.

“Now I am not quite sure if I should report e-commerce for our company…I still don’t consider our company engaging in e-commerce. But if we have to report [based on these instructions], it will be ‘all or nothing,’ either our total revenue is considered e-Commerce, or none is e-Commerce.”

This participant was unsure how to apply the archetype of e-Commerce (i.e., Amazon) to their specific business. They were unable to come to a definitive decision about whether they would report e-Commerce revenue and thought that it may be appropriate to report either all of the revenue as e-Commerce or none of it. They wanted further industry-specific instructions to help them understand, sharing, “None of the instructions really fit the description of our company’s business transactions. We would need some instructions that fits our industry for us to follow and report.”

The other participant reporting for a utility company had similar questions about the applicability of the question text and instructions to their business. They were unsure whether instances when customers reported meter readings online should be considered buying or reserving online. They were also unsure how to interpret “placing an order” in the context of their industry.

“I just read that second bullet, but I don’t think that one is really applicable. ‘buy or reserve online’—it’s interesting, right. The gas comes through the pipes and the end users like residential folks for instance can pay online, so I guess that is them buying online, but it is interesting. It depends on how you view it…. I guess I still don’t know if a customer enters their meter read online—does that count? It is what is going to generate the invoice… It seems like it would be based on ‘buy or reserve online’…and they pay online. So, in a way, yes. It is just a little tricky for the gas or utility industry. It’s just different… [the instruction] says ‘sales of goods or services’—I mean gas would be considered a good. It almost seems like it isn’t applicable to us. Is putting a meter amount of what they used placing an order? I don’t know. Is that what is being meant there?”

This participant went on to ask for further industry-specific clarification, sharing:

“I don’t know if the Census Bureau could clarify for our industry—I would think that across the industry things are fairly consistent in how transactions are recorded as far as revenue and customers.”

They also raised the potential for measurement error in their industry if different businesses interpreted transactions as either e-Commerce or not e-Commerce. Other participants also raised the need for industry-specific instructions, such as one participant, who shared, “I don’t know how you’re going to change all the instructions you’d have to get industry specific to make it fit for every business.”

Other industries that may benefit from industry-specific instructions include hotels and telehealth providers. This participant thought throughout the interview that their hotel business should not be considered e-Commerce, and when asked about how to make it clearer that the hotel reservations should be included, she stated, “I would include reservations or something like that. Online reservation or hotel booking so then we would include it.” Comparatively, another participant questioned whether telehealth services should be considered e-Commerce when discussing e-Commerce at large and changed her opinion after viewing the question text and instructions. She believed that “if [telehealth] is part of [e-Commerce], then it has to be in the instruction,” otherwise she would not include it in her reporting.

The current AIES e-Commerce question instructions seem overly focused on retail industries and may omit key instructions for other industries, as outlined in this section. Further consideration of industry-specific instructions may be important to minimize measurement error.

Applicability concerns for business activities operated under contracts or with salespeople

As noted in Section 3.2.3, businesses that use salespeople also struggle with conceptualizing e-Commerce in the context of their business. After viewing the question instructions, one participant described the process for salespeople.

“Our salespeople are out visiting a [client site] and they put the order in their app or iPad or device, they are traveling to the place where the customer is in person and get credit for the sale. Is that really e-Commerce? That person is making the sale in person, but it’s put into the app…To me e-Commerce is based on how the sale is made, how the revenue is created not how received.”

This perspective is similar to another participant, who after seeing the question instructions believed e-Commerce should be defined by POS rather than how the payment is remitted. For this participant, POS would be with their salespeople regardless of how the sale is recorded in their system. Because customers are not interfacing directly with an online or electric system, they would not consider these transactions e-Commerce.

The other participant whose business uses salespeople also questioned how to categorize these transactions. For their business, customers can make a reservation online, but they travel to the store in person to view the product and make the final purchase. When this happens, the salesperson interacts with the customer and may make a difference in the final products purchased. They would not consider these transactions e-Commerce.