SAMHSA Response to OMB

Att 04_SAMHSA Response to OMB_3.3.2011.docx

Cross-Site Evaluation for the Benefit of Homeless Individuals (GBHI)

SAMHSA Response to OMB

OMB: 0930-0320

Attachment 4: SAMHSA Response to Original OMB Comments (3/3/2011)

Evaluation of SAMHSA Homeless Programs

Client Interview and Stakeholder Survey

Response to OMB February 22, 2011 Comments (Submitted March 3, 2011)

Summary Response

The following is a response to OMB review comments received on February 22, 2011, in response to the application for data collection for the Cross-Site Evaluation for the Grants to Benefit Homeless Individuals (GBHI) Program that was submitted December 30, 2010. We have listed each of the questions and comments in bold and provided our response. We also have attached, in response to the reviewers’ requests, the baseline and 6-month client surveys amended to respond to reviewer comments and the IRB approvals for stakeholder, client and other data collection efforts. To aid in review of response, we begin with a brief summary response for each Comment.

1. SAMHSA GBHI program background (Part A, Section 1). We provide a background of the SAMHSA GBHI program.

2. Evaluation design and “outcomes” (Part A, Section 2). We describe the evaluation framework and SAMHSA’s intent for the evaluation to address SAMHSA’s questions in terms of this formative evaluation. In brief, the purpose of the evaluation is formative with an intent to identify and measure post-program participation findings across the broad array of outcomes expected to be influenced by the range of services provided by GBHI Grantees either directly or through referral. These are programmatic outcomes that are used to monitor the provision of services, understand the way services are tailored to clients with different needs and to better understand how the implemented service models match the models described in the efficacy and effectiveness literature.

3. Web capabilities for stakeholder survey (Part A, Section 3). We describe the extensive experience of the contractor in developing and administering similar web stakeholder surveys, past and potential response rates, and grantee stakeholder feedback on the proposed stakeholder survey.

4. Incentives (Part A, Section 9). We agree that the incentives are cash-equivalent. We note the language on the client interview consent of “non-cash coupon” (Supporting Statement Attachment 6) and note IRB’s request for this level of specificity to not confuse clients or create an expectation that they will be receiving cash from the GPRA interviewer. We are willing to use language that satisfies OMB’s recommendation for clarity, our IRB, and SAMHSA policies.

5. Interviewers, Confidentiality, GBHI client survey and GPRA survey, IRB (Part A, Section 10). Interviewers: We provide the additional requested information on the interviewers explaining that the Grantee interviewers are trained interviewers trained both by Grantees and by SAMHSA for administration of the CSAT GPRA Client Outcome Measures and tracking. We also collected information from each of the 25 GBHI GBHI sites regarding work performed, background, training, and feasibility of implementing the GBHI supplemental client survey along with the CSAT GPRA Client Outcome Measure (OMB control number 0930-0208). We describe how these interviewers, while employed by the Grantee, are trained interviewers who engage in GPRA interviewing and tracking of clients in accordance with SAMHSA’s procedures that were OMB approved. We also provide the results of a two-site pilot test of the client survey that included cognitive testing, with active clients per the request of OMB. The pilot test demonstrated the feasibility of the survey in terms of format, content, and administration procedures for both clients and the interviewer. Per OMB’s suggestion we have added additional instructions on the survey to remind interviewers to display “Show Cards” that are also in training materials; we attach the GBHI client survey with those suggestions within the bounds of the directions from the standardized measures.

Confidentiality: We agree with the reviewers that the surveys are not anonymous and point to the Supporting Statement sections that emphasize the contractor’s procedures to ensure client privacy (section A.10, pages 11-13 ).

GBHI survey: We provide the reviewers with the requested information regarding the CSAT GPRA Client Outcome Measures (OMB control number 0930-0208), purpose as approved by OMB, and how the GBHI survey would be administered according to GPRA procedures following the GPRA administration during the same session. We also describe our positive results from our pilot study of the surveys, which found that the procedures proposed are feasible regarding client and interviewer burden, response time, and response sets.

IRB: In response to reviewer request we have attached the human subjects approval per the contractor’s Internal Review Board (IRB). We also emphasize the procedures that were undertaken, that there were no IRB concerns noted, that the consent and procedures were viewed as protecting the client and agency. We also point to the discussion of the IRB and findings that was included in the Supporting Statement (section A.10, pages 13-14).

6. GBHI client survey burden and response rate (Part A, Section 12). Reviewers requested a pilot of the survey with active clients out of concern that those in recovery and who were employed as contractors would not be representative of those who may not be in recovery and in treatment. The pilot to test the GBHI client survey content, procedures, burden and feedback (through cognitive testing) was implemented in two sites with active clients. Findings of the pilot indicated that current GBHI clients responded within the average time of that previously reported in the Supporting Statement (section A.12, pages 14-15 and section B.4, pages 21-22); burden included consent, survey, self-administration, looking up of client information, and receipt of self-administered information. OMB also asked about response rates. All clients approached for the pilot study responded positively and agreed to enroll in the pilot, however, we continue to propose that response rates over time will be at least 80% for the GBHI survey given the current rates of GPRA consent at baseline and 6-month follow-up (87.6% for GBHI Grantees per SAIS 6-month follow-up data). As it is proposed to administer both the GPRA survey and GBHI client survey in the same setting reducing burden and cost to clients and staff GPRA interviewers, we also piloted the survey with and without the GPRA survey in one setting. Our findings were that data quality was not reduced, clients did not experience the surveys as redundant and clients and interviewer did not experience an undue burden. The approach of combining the two survey administrations also has precedent in previous SAMHSA evaluations that were OMB-approved (Access to Recovery, OMB control number 0930-0299; Screening, Brief Intervention, Brief Treatment and Referral to Treatment Cross-site Evaluation, OMB control number 0930-0282; Targeted Capacity Expansion Program for Substance Abuse Treatment and HIV/AIDS Services, OMB control number 0930-0317).

OMB also requested a burden estimate for tracking. Given that the majority of clients remain in the program over six months, based on SAIS GPRA discharge data (OMB control number 0930-0208) for the GBHI program, that programs remain in contact with clients post-program completion or drop out (based on discharge numbers and on site visit and telephone interviews with each of the 25 sites conducted in the fall and winter 2010 – 2011), and that the GPRA interviewers are required to attain at least 80% response rate for the 6-month (with current GBHI rates at 87.6%), the additional burden for the GBHI survey would be negligible. This is also part of the rationale to administer both surveys at the same time, to minimize the burden of the cross-site evaluation on Grantees, their staff and their clients.

7. Analysis plans, duplication and non-response (Part A, Section 16). Per the reviewers request we include a brief description of the analysis plans and three sample data shell tables. We discuss how the GBHI client (and stakeholder) surveys were developed to not duplicate current SAMHSA performance collection requirements as also described in the Supporting Statement (section A.4, page 8). We also address the non-response issues. Specifically, administration of baseline surveys will be continual as new clients enroll in the program each month. Therefore, 6-month follow-up interviews will always follow the baseline date but no sooner than 180 days and no later than 210 days for an individual client (as is the OMB-approved CSAT GPRA protocol with which we are coordinating, OMB control number 0930-0208). No interviews will be attempted outside of these windows and those clients who do not complete an interview will be considered ‘non-respondent’. Since baseline interviews will cease in Spring of 2014, no follow-up interviews will be conducted after Fall 2014.

8. Survey Frame and Sampling. (Part B, Section 1). We address the question of why we are conducting a census rather than employing sampling methods, based on sample sizes, the needs of our evaluation, power, and the possible negative impact of selecting a subset of clients who will be aware of the individuals which were selected.

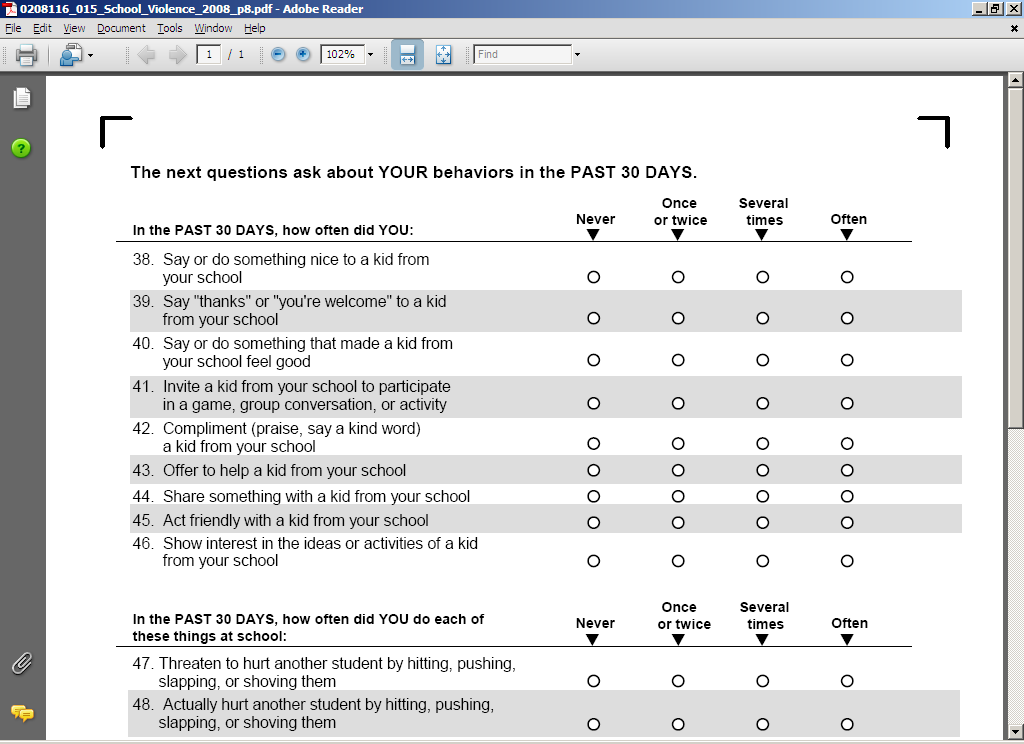

9. GBHI client survey (Part B, Section 2). Reviewers stated a set of concerns regarding the “complexity” of the survey for the population, given use of Likert scales and matrices and time-based questions, and requested detailed information on the sources and use of these types of scales and formats with the population. In summary, we provided information that supports that the majority of scales developed for this population include Likert scales (E.g., Bernstein et al., 1994; Bliese et al., 2008; Broner et al., 2002; Conrad et al., 2001; Davis et al., 2009; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983; Eisen et al., 2000, 2004; Gardner et al., 1993; Gulcur et al., 2007; Greenwood, Schaefer-McDanile, Winkel, & Tsemberis, 2005; Keane, Newman, & Orsillo, 1997; Koenig et al.,1993; Lang & Stein, 2005; Lehman, 1988; Lehman et al., 1991; McEvoy et al., 1989; Overall & Gorham, 1988; Peters & Wexler, 2005; Peters et al., 2008; Robbins et al., 2009; Rollnick et al., 1992; Ruggiero, Del Ben, Scotti, & Rabalais, 2003; Saltstone, Halliwell, & Hayslip, 1994; Shern et al., 1994; Skinner, 1982; Spies et al., 2007; Srebnik, Livingston, Gordon, & King, 1995; Storgaard, Nielson, & Gluud, 1994; Tsemberis, Moran, Shinn, Asmussen, & Shern, 2003; Weathers, Litz, Huska, & Keane, 1994; Zung, 1979). Similarly, time-based questions are commonly used and have been demonstrated as reliable and cognitively appropriate for assessment with psychiatric, substance abuse, criminal justice, veteran and homeless populations (for example, Banks, McHugo, Williams, Drake, & Shinn, 2002; Broner et al., 2002; Broner et al., 2004; Brown et al., 1993; Burt, 2009; Carey, 1997; Clark & Rich, 2003; Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, 1997; Ehrman & Robbins, 1994; Fischer, Shinn, Shrout & Tsemberis, 2008; Milby, Wallace, Ward, Schumacher, & Michael, 2005; North, Eyrich, Pollio, & Spitznagel, 2004; Peters & Wexler, 2005; Peters et al., 2008; Sacks, Drake, Williams, Banks & Herrell, 2003; Smith, North, & Spitznagel, 1992; Sobell & Sobell 1992; Sobell & Sobell, 1995; Spies et al., 2007; Tsemberis, Gulcur, & Nakae, 2004; Tsemberis et al., 2007—many of which are also likert response scales). Time-based and likert scale (matrix) questions focused on housing satisfaction, psychiatric symptoms and functioning (including trauma), drug use and attitudes, service choice, burden and satisfaction, quality of life, social supports, homeless and residential history, military history, education and employment, and so forth, have been included in current and prior OMB approved evaluations and SAMHSA-wide client-level program performance data collection (For example, SAMHSA Targeted Capacity Expansion Grants for Jail Diversion Programs, OMB control number 0930-0277; SAMHSA Homeless Families, OMB control number 0930-0223; HUD Life After Transitional Housing, OMB control number 2528-0239; National Outcomes Performance Assessment of the Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness , OMB control number 0930-0247; Access to Recovery, OMB control number 0930-0299; Safe Dates, OMB control number 0920-0783; School Violence, OMB control number 1850-0814; SAMHSA CMHS NOMs Adult Consumer Outcome Measures for Discretionary Programs, OMB control number 0930-0285; SAMHSA CSAP Participant Outcome Measures for Discretionary Programs, OMB control number 0930-0208).

Per the request of the reviewers we cross-walk each survey question and identify the domain, justification, some of the literature in which data from these measures is published, and the OMB control number for those measures that have been previously included in a relevant OMB approved survey. We also highlight for reviewers that measurement choice was the result of an extensive literature review and expert panel meeting that included national researchers, consumers, policy makers, other advocates and government agencies as described in the Supporting Statement (section A.2, page 4 and section A.8, pages 9-11). We add information based on our site visits and conversation with the 25 GBHI Grantee sites subsequent to submission of the Supporting Statement that provide support for this survey. We also present results of the cognitive testing and burden estimates (consistent with the tables submitted in the Supporting Statement, section A.12, page 14-15) of the survey with current active clients in two sites responsive to the OMB request for a “full dry run” and cognitive testing with active clients.

GBHI Client Survey and Stakeholder Survey Response to OMB Questions

Part A

Section 1:

We would like some additional background on how the program works and how a client gets involved in the program. If SAMHSA can provide an already-written background document that answers all of these questions, then they do not need to be answered separately.

Response: The Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) was funded by Congress to establish the Grants for the Benefit of Homeless Individuals (GBHI) program, sometimes also referred to as the Treatment for Homeless program. GBHI is a competitive, discretionary program initiated in 2001 to reduce homelessness and maintain housing through provision of treatment and other services to youth, adults and families with substance use and co-occurring mental disorders. The GBHI program includes general Grantees focused on intervening in homelessness and services for supportive housing (SSH) Grantees who provide supports for those previously homeless to maintain their housing and sobriety. The program’s goals are to (1) link substance use and mental health treatment services with housing programs and other services, (2) expand and strengthen treatment services for people who are homeless who also have substance use disorders, mental disorders, or co-occurring substance use and mental disorders; and (3) increase the number of homeless people who are placed in stable housing and who receive treatment services for alcohol, substance use, and co-occurring disorders.

Between 2001 and 2008, GBHI awarded 169 grants to provide services to the target population. An additional 25 Grantees were funded in 2009. Some Grantees serve priority populations, including criminal justice populations, chronically homeless persons, returning veterans, and chronic public inebriates; others focus on serving families, women, native Alaskans, Native Americans/Indians, other minority populations, or youth. Although all are required to, at a minimum, provide outreach, case management, substance abuse or co-occurring disorders treatment (integrated, sequential, or parallel), and wraparound and recovery services, many augment these services by adopting or adapting additional evidence-based practices (EBPs) from one of the SAMHSA toolkits (e.g., Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), Illness Management and Recovery, Supportive Employment), CSAT’s Treatment Improvement Protocols, or the National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices (NREPP). The models for service delivery vary and include primarily by referral, direct provision of treatment and other services, or a mix of direct service provision and referral to other community-based organizations. Service models are implemented in an array of settings, including on the street through outreach; in drop-in settings, shelters, and hospitals; at medical, substance abuse, or mental health clinics; in residential treatment communities; or in any of these settings or other nonoffice settings through mobile crisis units or ACT teams.

As described below, all clients are assessed by Grantees at intake, 6-months follow-up to intake and at program discharge with the CSAT GPRA Client Outcome Measures (OMB control number 0930-0208) which data is provided to SAMHSA via the web and stored in the Services Accountability Improvement System (SAIS). Since the inception of the GBHI program, CSAT homeless grants have served 33,171 individuals, a majority minority men aged 18 to 54 (Le Fauve, 2009). In 2010 the active portfolio has served over 22,000 individuals. Per the FY2010 President Obama’s budget, outcomes data available for a subset of clients served by the program through 91 active GBHI Grantees was cited indicating that individuals demonstrate: 1) 122% increase in employment or engaging in productive activities; 2) 166% increase in persons with a permanent place to live in the community; 3) 52% increase in no past months substance use; and 4) 36% improvement in no/reduced alcohol or illegal drug related health, behavioral or social consequences.

How likely are clients to remain in the program once they are admitted?

Response: Client retention is high among these programs. This is due in large part to the fact the programs are designed using evidence-based practices to intensively engage and retain an at-risk population that otherwise has limited resources. Among the 25 GBHI program Grantees that are the focus of the cross-site evaluation, typical program participation varies from 6 months to 24 months, based on grantee proposal reviews and telephone conversations with program directors and site visits conducted during the fall and winter 2010 -2011. The program length was designed by each grantee to address the needs of each grantee’s target population. A review of prior GBHI cohort CSAT GPRA Client Outcome Measures data (OMB control number 0930-0208) submitted to SAMHSA via the Services Accountability Information System (SAIS) indicates that clients of these earlier grantee programs remained in the programs an average of 139 days. These data also report high six month follow-up rates for clients who begin the programs, 87.6% as of February 28, 2011.

Does someone follow-up with respondents if they leave the program early?

Response: Yes. Grantees are required by SAMHSA to conduct a 6-month follow-up GPRA survey with at least 80% of their clients. If clients leave the program prior to six months, the grantee still has to follow-up with them. The current 6-month follow-up rate for all GBHI Grantees is 87.6%. Grantees are trained in tracking and retention of clients to assist their efforts in following-up with clients through face-to-face trainings provided quarterly and a series of on-line courses. If grantee interviewers require further assistance, they may also request telephone or on-site technical assistance in client retention, tracking and follow-up techniques. Grantees also conduct a discharge interview when a client is discharged from or has left the program regardless of calendar time since enrollment.

Does someone follow-up with clients after they complete the program?

Response: Grantees are required to complete a GPRA survey with at least 80% of their clients six months following the baseline interview. If a client completes the program before the 6-month period ends, the grantee is required to attempt to contact them and complete the 6-month interview. The current 6-month follow-up rate for all GBHI Grantees is 87.6%. Grantees also conduct a discharge interview when a client is discharged from or has left the program regardless of calendar time since enrollment.

Are you planning to follow any of the clients who drop out of the program during the survey period?

Response: Yes. The GBHI client interview will be administered by trained GPRA interviewers following the GPRA interview during the same meeting. The procedures for follow-up for the GBHI client interview mirror those for the CSAT GPRA Client Outcome Measures approved by OMB (control number 0930-0208). GBHI clients are required to be followed during this period whether or not they are still enrolled. We note again that these programs have a low drop-out rate.

Who are the stakeholders and what is their relationship to both the grantee and the client?

Response: Stakeholders are individuals, groups of individuals or organizations who are affected by these programs, who have an interest in the impact of these programs and who may offer collaboration or support for these programs and their clients. Examples of current stakeholders include substance abuse treatment providers, mental health treatment providers, housing providers, vocational service providers, medical care providers, HIV/AIDS services organizations, housing authorities, veterans agencies, state/city/county policy makers, state-/county-/city-wide initiatives to end homelessness, advisory boards, consumer boards, and advocacy groups. These stakeholders may have a direct relationship with both the grantee and the clients as partners to the grantee who provide services to the clients. The relationship can also be direct only through the grantee. For instance, a housing authority that funds housing will have contact with the grantee and require reports from the grantee on a continual basis, but will not have direct contact with the clients themselves.

Does the stakeholder know and interact with the grantees?

Response: The level of interaction between stakeholders and grantees varies based on information collected during conference calls with and site visits to the 25 GBHI Grantees. Stakeholders may have an active or passive relationship with the grantee programs. Part of the rationale of collecting data from these stakeholders is to better understand how these programs interact with the stakeholders in their communities and more broadly in the system.

What about with the clients?

Response: The client knows and interacts with the grantee staff, as well as with contractors and other service provider staff from stakeholder agencies. The client is unlikely to know the stakeholders per se but is usually aware of their agencies.

Are the grantees known to the clients?

Response: Yes, the Grantees are the programs that serve the clients. They provide services to the clients, either through direct provision or through linkage to another organization. Grantees are required by SAMHSA to provide, either directly or through referral, direct treatment for substance abuse and mental health disorders (which includes screening, assessment, and active treatment), outreach, case management, and wraparound services (which can include, for example, relapse prevention, crisis care, education or vocational services, transportation, medical care, housing readiness training, benefits application, housing application, peer support services). All clients are screened and accepted by the grantee program. Only once they are accepted by the grantee are they a “GBHI client.” The Grantees employ interviewers to screen, assess, administer the CSAT GPRA Client Outcome Measures (OMB control number 0930-0208) at baseline and follow-up points and to track clients while active, following or if leave the program, as described above.

Do the grantees and the clients ever interact during the course of the program?

Response: Yes. Grantee staff interact with the clients during the course of the program both providing direct services and helping the client to link to other community services. Grantees also hire GPRA interviewers to screen, assess and track clients who will interact with the clients over the course of program involvement and likely beyond during aftercare, or if they have dropped out of the program.

Section 2:

We are concerned with the “outcome” portion of the evaluation. It lacks the rigor of a counterfactual or control group. Therefore, it is inappropriate for SAMHSA to ascribe causality, impact or effect of the program, as it appears that SAMHSA may wish to do (e.g., page 3, “focus on the effects…on client outcomes”). For a formative evaluation, it can be appropriate to measure much more modestly than is proposed here a limited number of low burden client outcomes to see if the program shows promise (i.e., the absence of any positive outcomes would suggest a program with little or no promise). For simple grantee monitoring, it can be useful to determine grantee adherence to specified practices, which should have a very modest, if any, client component. Please clarify which of these SAMHSA aspires to do.

Response: The purpose of the evaluation is formative with an intent to identify and measure post-program participation findings across the broad array of outcomes expected to be influenced by the range of services provided by GBHI Grantees either directly or through referral. These services, which are provided following assessed need, include, as detailed above, treatment for substance abuse and mental health disorders (which includes screening, assessment, and active treatment), outreach, case management, and wraparound services (which can include, for example, relapse prevention, crisis care, education or vocational services, transportation, medical care, housing readiness training, benefits application, housing application, peer support services) and aftercare. As much as possible the intent is for each of these services to be based on models and practices that have an evidence base in peer-reviewed literature. Thus, outcomes directly relevant to the GBHI program include those related to substance use, mental health, employment and education, as well as to additional behavioral outcomes and housing. As correctly noted by the reviewers, the evaluation does not intend to draw causal inferences with respect to the GBHI program participation and outcomes, but to measure (more explicitly than the current GPRA measures allow) a variety of outcomes directly related to the specific services included in the GBHI programs. These are programmatic outcomes that are used to monitor the provision of services, understand the way services are tailored to clients with different needs and to better understand how the implemented service models match the models described in the efficacy and effectiveness literature. The additional questions place a time burden of 20 minutes on respondents (as described in the Supporting Statement, section A.12, pages 14-15 and section B.4, pages 21-22 and per survey testing with active clients in two sites subsequent to submission of the Supporting Statement) and will provide invaluable information to guide future programming efforts to aid homeless individuals with substance use or mental health disorders.

Describe the use of the information gained by the comparison of the self administered Part II of the baseline survey that contains several overlapping questions with the baseline survey. What quality indicators are in place for analysis of contradicting responses?

Response: The SV portion module of Part I of the survey is not self administered and contains questions about service needs and then actual receipt of needed services. The PC and the TCC (Part II) are self-administered and are intended to measure clients’ perception of the grantee program and the services they received. The PC produces a measure of overall client satisfaction, as well as the program’s culture with respect to empathy and attentiveness to clients and client empowerment. The goal of the TCC is not intended to gauge client satisfaction per se but is designed to capture the overall ‘philosophy’ or ‘style’ of the program model that is being implemented by the grantee. Specifically, some models, particularly for housing a population like this, use approaches that are prescriptive or coercive or part of a mandate from the criminal justice system. In order to assess where a grantee model fits in that dimension, the clients’ perceptions of how choice is presented and the requirements or stipulations surrounding other services are used to populate this scale. These client provided data are a capstone to or are part of the triangulation process that uses multiple data sources to evaluate these models (e.g., qualitative data from grantee interviews and documents, other administrative data, etc.)

Although there appears to be some overlap between the PC and the TCC for some questions they are qualitatively different questions. In the case of the PC, for example, the client is asked if they would switch providers if other providers were available. The similar question in the TCC asks whether switching to another provider would be permitted for that client (e.g., court –ordered to a particular provider). We believe we should maintain the integrity of the instruments and use them for their distinct goals. A quality review of these data is an important exercise for surveys like these. We intend to have boolean cross-checking using SAS or STATA for all elements that might yield internal inconsistency and either use logical imputation when possible or suppress scale items for which there is no clear solution. Fortunately, the properties of most scales are robust to a small number of missing items including for example the use of Likert matrix questions as part of a self-administered interview is consistent with other OMB approved studies such as Access to Recovery (OMB Control Number 0930-0299.

Section 3:

Have you tested the web capabilities and response rates for the stakeholder survey?

Response: We have not formally tested the web-based version and response rate for the stakeholder survey as it has not yet been approved and the cost of doing so would be prohibitive prior to OMB approval. However, as part of the site visits held in the fall and winter 2010-2011members of the evaluation team have met with stakeholders at each of the 25 GBHI Treatment for Homeless Grantees where we reviewed and discussed the stakeholder survey, including the survey questions, web-based format, length of the survey, and likelihood of response. The feedback we received was positive without suggestions for modifying the content, layout or procedures. The length of time estimated to take the survey, 17 minutes (as described in the Supporting Statement, section A.12, pages 14-15 and section B.4, page 22)was endorsed as non-burdensome. Also, the stakeholders’ familiarity with SAMHSA and the purpose of the types of programs it funds and interest in community services was viewed as a positive to attaining a high response rate within our anticipated response rate. As described in the Supporting Statement (p. 17) we conservatively estimated a 50% response rate for prior completed Grantee Stakeholders and an 80% response rate for current Grantees Stakeholders producing an average response rate of 65% across all years of GBHI program funding. The contractor, RTI International, has extensive experience in both developing and administering web-based surveys and surveying stakeholders with program models similar to the GBHI Treatment for Homeless program. The below table highlights a few of these studies and describes their applicability to the stakeholder survey for this evaluation.

Study Name |

Relevance/Experience |

OMB Control Number |

Evaluation of the National Weed and Seed Strategy |

Included a Web-based survey of stakeholders such as agency representatives or involved residents in 169 sites (1,353 respondents) achieving a 59% response rate. Please note that many of these 169 sites had already completed their funding cycle and thus had no direct mandate to participate in the evaluation unlike GBHI where we have ongoing relationships with all 25 sites and, as a part of their receiving funding, are required to participate in the cross-site evaluation. |

N/A |

Law Enforcement Forensic Processing Study |

Multi-mode survey, including web-based, of 2,000 law enforcement agencies achieving a 73% response rate. |

1121-0320 |

Safe Schools/Healthy Students Cross-site Evaluation |

Included a survey of partnership members and key partners in 97 grantee sites. During four waves of data collection the average response rate for these surveys was 65%. |

1121-0247 |

Section 9:

Incentives:

Grocery cards are a cash equivalent incentive. Please change the description in A9. We only consider items that are not easily exchanged for money, like a ruler or a magnet, as non-cash incentives. A gift card to a grocery store could easily be exchanged for cash and therefore should be considered a cash incentive.

Please clarify when the client receives the incentive.

Response: Question 1. We agree we are proposing cash equivalent incentives. All of the 25 Grantees requested cash equivalent incentives such as Target gift cards in discussions about the planned cross-site evaluation. The Grantees’ rationale for cash-equivalent incentives was twofold. First, all Grantees indicated that these types of incentives would be administratively easier to receive and track than other types of incentives. Second, the Grantees indicated that the clients would prefer something that they could use toward food and housing items. As described in section A.9 on page 11 of the Supporting Statement, incentives have been demonstrated to increase response rates and panel retention in surveys about sensitive behaviors without being overly coercive (Cottler et al., 1996) . We are also comfortable that using gift cards does not alter either the response rate or increase the probability of increasing substance use (Festinger et al., 2008). The language on page 9 of the Supporting Statement should have read: To increase response rates, all clients who agree to participate in the client interview at baseline will receive an incentive worth a $10 value (e.g., gift card). Participants who complete the baseline will be asked to complete a 6-month follow-up interview. Clients who agree to participate in the 6-month follow-up will receive an incentive worth a $25 value.”

The client consent form submitted on December 30, 2010 with the Supporting Statement (Attachment 6) reads “non-cash coupon worth $10.00 today; you will also receive a non-cash coupon worth $25.00 at the 6 month follow-up interview…”. Would OMB like this changed by deleting the words “non-cash” so the informed consent reads “coupon worth…”. The downside is that it is perhaps misleading in that clients may expect a “cash” coupon then; this level of specificity, “non-cash coupon”, was encouraged by the IRB.

Question 2. As noted in the submitted informed consent submitted with the Supporting Statement (Attachment 6), incentives will be provided at the baseline administration of the GBHI Client Interview and at the administration of the 6-month follow-up interview. Clients will not be penalized for skipping items or terminating an interview before full completion. If a client wishes to stop the interview, he or she will still receive the incentive.

Section 10:

Interviewers:

We are concerned that you are using grantees as interviewers for two reasons:

While it may be useful to have the grantees administer the client surveys because they are familiar with the clients, there is also a conflict of interest since the client will be evaluating the program with a grantee present.

We are also concerned because survey administration is not an easy task and while you will provide training to the grantees prior to the evaluation, they are not professional interviewers and they may not be as comfortable or skilled at collecting the required data.

Response:

Question 1. While we appreciate the concern that using Grantees as interviewers runs the risk of a potential conflict of interest, it is one of the limitations of this type of performance assessment. Grantees employ trained interviewers whose job it is to administer the CSAT GPRA Client Outcome Measures interviews, other program assessments, and track clients that are active and those who have dropped out of the program for 6-month and discharge interviews This method of grantee collected data is the primary method that can generate data on a large number of subjects from all 25 grantee programs given the level of available resources. Further as these data are used for clinical and performance assessment by Grantees, to collect them twice (once for grantee use in performance assessment and once for evaluation) would be duplicative and burdensome. OMB has approved multiple evaluations with grantee only or a mix of grantee and independent assessors depending on the grantee, for example: Targeted Capacity Expansion Grants for Jail Diversion Programs (OMB control number 0930-0277), Homeless Families (OMB control number 0930-0223), National Outcomes Performance Assessment of the Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness, (OMB control number 0930-0247), ; Targeted Capacity Expansion Program for Substance Abuse Treatment and HIV/AIDS Services (OMB control number 0930-0317). The assessment of the program by clients is, however, client self-administered to reduce response bias consistent with an approach taken by the OMB approved Access to Recovery (OMB control number 0930-0299) cross-site evaluation survey that includes Likert-matrix client self-administered satisfaction and detailed program feedback.

Question 2. We did not sufficiently describe in our Supporting Statement the Grantee interviewers who will conduct these interviews. Although the interviewers will be Grantee staff, they are “professional interviewers” that have been trained in interviewing and tracking in conjunction with their role conducting the SAMHSA CSAT GPRA Client Outcome Measures for Discretionary Programs (OMB control number 0930-0208), as well as through Grantee sponsored training. In preparation for the proposed data collection activities, we conducted telephone and face-to-face discussions during site visits with the grantee GPRA interview staff, as well as with managers, supervisors and local evaluators. We have confirmatory information following submission of the Supporting Statement about the level of the interviewers and the interviewers’ assessment of the proposed interviews and interview procedures. Based on these discussions with each of the 25 CSAT GBHI Treatment for the Homeless Grantees, each of the 25 sites has GPRA interviewers who have been trained by SAMHSA through face-to-face and on-line courses on interviewing and tracking of clients for follow-up interviews. Each of these interviewers has also received additional training from the Grantees in administering screening and assessment surveys and in engaging and tracking clients. These interviewers while employed by the Grantee are responsible for administrating the CSAT GPRA and other interviews, assigning ID numbers for on-line submission to SAMHSA for client-level data collection, providing incentives if the Grantee provides incentives, and tracking and following up with clients during and following program completion or drop-out for client, per procedures approved by OMB (control number 0930-0208). Grantees had prepared their staff for potential participation in client-level and other data collection prior to award, based on the SAMHSA GBHI Treatment for Homeless Request for Application (RFA) language that if a cross-site evaluation was awarded Grantees have agreed to participate in the cross-site evaluation activities.

The proposed GBHI client baseline and 6-month follow-up interviews were carefully reviewed by the cross-site evaluation expert panel and SAMHSA staff (see Supporting Statement section A.8, page 9); include the use of standardized instruments and measures previously approved by OMB for other cross-site evaluations including the population of focus for the GBHI cross-site evaluation (see Supporting Statement section A.2, pages 4-7 and below); and were reviewed with GPRA interviewers along with supervisory, management and local evaluation staff from each of the 25 GBHI sites. Following a semi-structured site visit protocol, each question was reviewed, along with procedures. Questions were asked regarding any potential redundancy with current GPRA questions, which questions or domains should be included or removed, and what additional questions should be considered. All 25 sites, consistent with the expert panel and prior SAMHSA review, endorsed all questions and associated domains as non-redundant; further grantee respondents thought the survey was particularly additive for the Treatment for Homeless program in terms of describing their clients, the areas of focus for clients and services, activities for a sufficient period that would capture both Grantee services and client activities, beliefs and behaviors, and that this would help to better describe the individual grant programs and overall GBHI program. While Grantees had suggestions for additional domains, they did not recommend replacing the questions proposed; adding more questions was viewed by the cross-site evaluation contractor as burdensome. Further, the Grantees felt that the format of the questions and type of questions were consistent with other questions clients answer without difficulty or confusion and believed that accurate information would be obtained from time-based questions. Finally, two sites voluntarily pre-tested the interview with a total of 4 clients during the original response period for comments/feedback and confirmed that there were no difficulties in overall administration, in response to individual questions, in response to Likert matrices or time-based questions, or completing self-administered sections. Grantees noted that clients were used to these types of interviews and to both interviewer administered and self-administered questionnaires. The findings of these two Grantees were consistent with our findings of the two-site pilot test of the client baseline and 6-month surveys and of with feedback from the non-grantee interviewer who had conducted our pilot.

We recommend using a neutral third party interviewer and full dry run of the survey protocol and administration with potential respondents. While complete interviewer materials and training is important with any survey, this survey requires special conditions and procedures and as little as possible should be left up to the Grantees to make up on the fly. This is true for professional interviewers, but is especially important since you are proposing to use non-professional interviewers for your evaluation. A dry run of the evaluation with actual clients will help assure both the interviewers and the survey team that the evaluation protocol works and collects the desired information.

Response: In preparation for client-level data collection, if approved by OMB, we conducted a “full dry run of the survey protocol” (both baseline and 6-month follow-up client interviews) and conducted cognitive testing with clients. We administered each of the client protocols to 8 respondents for baseline and 6-month follow-up. We also tested whether receiving a pre-survey of GPRA questions would increase time, reduce responsiveness or change the quality of the responses, varying whether the clients received the surveys alone on in conjunction with the GPRA survey. The process also included full informed consent procedures, directions, Part I and Part II questionnaires including clients sealing their responses in the envelop and returning them to the interviewer. The interviewer was a non-grantee interviewer trained on the GPRA interview. The clients were active clients at two current SAMHSA sites. The time burden was consistent with that noted in section A.12 on pages 14-15 and section B.4 on pages 21-22 of the Supporting Statement and will not result in a revision of the burden estimate table. The results of this pilot showed an average of 4 minutes for reviewing client information and the consent procedures, 14 minutes to administer Part I, and 3 minutes for client self-administered completion of Part II for both baseline and 6 month followup. No client had suggestions for removal of items or evidenced difficulty or slowness on particular items; all clients had positive comments on the survey indicating satisfaction about being heard. A majority of the clients felt that by responding to the questions that the grantee programs would be better informed about the services clients needed and better able to describe client gains.

These data, along with the information from current GPRA interviewers who reviewed and pre-tested the interview also in two sites, with four clients, during the response/comment period, indicate that the survey could be successfully administered.

Moreover, the survey is comprised primarily of standardized measures or measures that are or have been used for other SAHMSA cross-site evaluations (OMB numbers 0930-0277, 0930-0223, 2528-0239, 0930-0285; 0930-0247; and see chart of measures below) and whose data has been published in peer reviewed publications (for example, Broner et al., 2009; Burt, 2009; Burt, 2010; Case et al., 2009; Davis et al., 2009; Naples et al., 2007; Rog et al., 1995; Rog & Buckner, 2007; Rog et al., 1995; Steadman & Naples, 2005). We do agree with OMB reviewers the inclusion of instructions on the interview itself is useful tool. For each standardized instrument, or previously OMB approved measure, we included the measures instructions to maintain the integrity of the measure (see Supporting Statement Appendix 6) in addition to emphasizing this in training materials for interviewers. We will add instructions to each of the Likert scale matrix questions for Part I, “present Show Card” as a reminder to the GPRA interviewer.

Confidentiality:

The client survey is not anonymous because the survey requires identifying information on it, i.e., a GBHI client number. An anonymous survey is one that requires no identifying information on it and cannot link an individual in any manner back to this form.

How is this number assigned and is it something that the client would know or would it be looked up by the interviewer?

Response: We agree with OMB that this survey is not anonymous. In a review of the submitted Supporting Statement and materials we could not find the use of the word ‘anonymous’. The information provided to the cross-site evaluation is provided via an ID number assigned by the Grantee interviewer. The GPRA interviewer at each of the 25 sites assigns a number to accepted clients. This “GPRA number” is used for submission of the SAMHSA CSAT GPRA Outcomes Measures (OMB control number is 0930-0208) via their on-line SAIS system and is kept by the Grantee not the client. This number would be placed on the supplemental client interview form by the GPRA Interviewer. The cross-site evaluation will then link this number to the GPRA data for each client. Linking to the already collected GPRA data minimizes the need to avoid duplicate collection of information. For example, demographic information, substance use and attitudes, general psychiatric symptoms (not-trauma), physical health (including HIV), sexual risk, and family supports is not collected on the supplemental baseline and 6-month surveys as these data are already collected via the CSAT GPRA survey.

GBHI survey:

How does the GBHI survey fit with the GPRA survey operations? While we can understand wanting to administer these two surveys together in order to simplify procedures, we are concerned about this might affect the results in GBHI.

What is the purpose of the GPRA survey and what kind of questions does it ask? Can you also send us either the OMB control number and/ or a copy of the GPRA questionnaire?

How long on average does it take to administer the GPRA survey?

What incentives are provided by GPRA, if any? Are they provided at the same time as the incentive is provided for GBHI?

Response:

Question 1. The GBHI client survey as described in section A.2 on pages 4-7 of the Supporting Statement would be administered following the GPRA survey as described in section B.2 on pages 18-20 of the Supporting Statement. The decision to conduct the GBHI client interview in conjunction with the GPRA survey was based on the recommendation of the 15-member expert panel and SAMHSA staff, as well as at the request of the 25 GBHI Grantees as confirmed during site visits held during the fall and winter 2010-2011. During the piloting of the baseline and 6-month GBHI client interviews in two sites with active clients, we varied the survey administration, administering it alone and with the GPRA and found no differences in response rates, response times, or consistency of responses. The different procedures also did not affect the consistently positive response to the GBHI survey or to the GPRA by the clients. Moreover, the approach of combining the two survey administrations has precedent in previous SAMHSA evaluations that were OMB-approved (Access to Recovery, OMB control number 0930-0299; Screening, Brief Intervention, Brief Treatment and Referral to Treatment Cross-site Evaluation, OMB control number 0930-0282; Targeted Capacity Expansion Program for Substance Abuse Treatment and HIV/AIDS Services, OMB control number 0930-0317)

Question 2. The CSAT GPRA Client Outcome Measures survey was OMB approved and reauthorized in 2009 (control number 0930-0208). The GPRA survey was developed and is used by SAMHSA to comply with the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) of 1993 which requires all federal departments to develop strategic plans, set performance targets related to their strategic plan on an annual basis, report annually the degree to which they met these goals, conduct regular evaluations of their programs and use the results to explain successes and failures on the basis of performance monitoring data. The GPRA survey serves as a performance measure for all of SAMHSA’s discretionary services grants. The CSAT GPRA survey collects information at baseline, 6-month and discharge on client demographic characteristics and drug (by type of drug and overall) and alcohol use, education, employment, criminal justice activity, HIV, sexual risk behavior, current housing, social connection, and general (not trauma) psychiatric symptoms for the 30 days prior to interview administration. As noted in section A.4 on page 8 of the Supporting Statement the GBHI client survey was constructed to complement and not be redundant with the CSAT GPRA. The additional information proposed for the GBHI supplemental survey is specifically relevant to Treatment for Homeless Grantees to describe these programs and their clients at baseline and 6-month follow-up.

Question 3. The GPRA survey was OMB approved and reauthorized in 2009 (control number 0930-0208). The total estimated burden for administering the CSAT GPRA Client Outcome Measures is 21 minutes including instructions, review of documents and client information prior to interviewing, and so forth. The average time for the CSAT GPRA survey administration is approximately 10 minutes.

Question 4. The GPRA allows for payment of $20.00 incentives for follow-up interviews. Grantees may choose to provide an incentive up to a $20 value for completion of the 6-month follow-up GPRA survey only, though it is not a requirement. Examples of incentives that clients may receive include gift cards, coupons, toiletries, movie tickets, transportation vouchers, etc. If the grantee has chosen to provide the client with an incentive for completing the GPRA survey, then yes they would receive the incentive at the same time as the incentive provided for the 6-month follow-up GBHI survey. However, based on discussion with the 25 Grantees during site visits, clients will not receive double incentives, for the baseline and 6-month interviews.

IRB review:

Was this collection reviewed by an IRB?

If so, provide the certificate of approval plus information about their findings and recommendations. Specifically, we are interested in knowing if they felt the consent form provided enough protection both for the clients and for the agency and if they had any additional concerns about gaining consent from this population.

Response: Questions 1 and 2. The data collection plan, procedures, surveys, consents and scripts were reviewed and approved by RTI International’s IRB, a federally assured IRB (Federal Wide Assurance Number 3331). The consent forms for the client and stakeholder surveys submitted with the Supporting Statement (see Appendices 6 & 7) includes the RTI IRB approval. The surveys and accompanying materials, procedures and design were approved by the IRB. No concerns were identified. The IRB approved the consent forms as providing sufficient information for protection of clients, stakeholders and agency. In response to reviewer request, we have attached the approvals relevant to the stakeholder survey and to the client surveys. This information is also available in the original Supporting Statement; please see the Supporting Statement, section A.10, pages 13-14 and excerpted below:

“In addition, the three interviews, all informed consents and the client interview script have been reviewed and approved by the contractor’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Federal Wide Assurance Number 3331), review #12612. In keeping with 45 CFR 46, Protection of Human Subjects, the CSAT GBHI procedures for data collection, consent, and data maintenance are formulated to protect respondents’ rights and the privacy of information collected. Strict procedures will be followed for protecting the privacy of respondents’ information and for obtaining their informed consent. The IRB-approved model informed consents meet all Federal requirements for informed consent documentation. This template will be customized by each grantee to obtain informed consent for participation in the study. Any necessary changes to the surveys will be reviewed by the contractor’s IRB.

Data from the CSAT GBHI client interviews will be safeguarded in compliance with the Privacy Act of 1974 (5 U.S.C. 552a). The privacy of data records will be explained to all respondents during the consent process and in the consent forms.” (P. 13-14, Lines 510-523, Supporting Statement)

Section 12:

Can you provide us with background information on why you expect an 80% response rate for both administrations of the client survey?

We would also like to see additional support for the 20 minute total estimated completion time, especially with respondents who currently represent the target population, instead of individuals who in the past represented these individuals. We are concerned that contractors, even those whom were formerly homeless, may not serve as a good proxy for your target population.

Can you provide information to support estimated burden in follow up time needed for non-respondents.

Response:

Question 1. All clients who are enrolled in the GBHI program complete the GPRA survey. Client retention is also high among these programs. This is due in large part to the fact the programs are designed using evidence-based practices to intensively engage and retain an at-risk population that otherwise has limited resources. This is also due to Grantees having dedicated trained interview staff to conduct interviews and track clients as described previously. Grantees are required to complete a GPRA survey with at least 80% of their clients six months following the baseline interview. If a client completes the program before the 6-month period ends, the grantee is required to attempt to contact them and complete the 6-month interview per the OMB approved GPRA procedures protocol (0930-0208). Grantees also conduct a discharge interview when a client is discharged from or has left the program regardless of calendar time since enrollment. Among the 25 GBHI program Grantees that are the focus of the cross-site evaluation, typical program participation varies from 6 months to 24 months, based on grantee proposal reviews and telephone conversations with program directors and site visits conducted during the fall and winter 2010 -2011. The program length was designed by each grantee to address the needs of each grantee’s target population. A review of prior GBHI cohort CSAT GPRA Client Outcome Measures data (OMB control number 0930-0208) submitted to SAMHSA via SAIS indicates that clients of these earlier grantee programs remained in the programs an average of 139 days. These data also report high six month follow-up rates for clients who begin the programs, 87.6% as of February 28, 2011. All clients approached for the pilot study responded positively and agreed to enroll in the pilot. We believe that our estimates of at minimum 80% enrollment and retention remains accurate as a projection over the course of the project and is consistent with the description in the Supporting Statement (section A.12, pages 14-15 and section B.3, pages 20-21).

Question 2. In preparation for client-level data collection, if approved by OMB, we conducted a “full dry run of the survey protocol” (both baseline and 6-month follow-up client interviews) and conducted cognitive testing with clients. We administered each of the client protocols to 8 respondents for baseline and 6-month follow-up. We also tested whether receiving a pre-survey of GPRA questions would increase time, reduce responsiveness or change the quality of the responses, varying whether the clients received the surveys alone on in conjunction with the GPRA survey. The process included full informed consent procedures, directions, Part 1 and Part II questionnaires including clients sealing their responses in the envelop and returning them to the interviewer. The interviewer was a non-grantee interviewer trained on the GPRA survey. The clients were active clients at two current SAMHSA sites. The time burden was consistent with that noted in section A.12 on pages 14-15 and section B.4 on pages 21-22 of the Supporting Statement The results of this pilot showed an average of 4 minutes for the consent procedures, 14 minutes to administer Part I, and 3 minutes for completion of Part II for both baseline and 6 month followup. No client had suggestions for removal of items or evidenced difficulty or slowness on particular items; all clients had positive comments on the survey indicating satisfaction about being heard. A majority of the clients felt that by responding to the questions that the grantee programs would be better informed about the services clients needed and better able to describe client gains. As described previously, two GBHI Grantees also administered the surveys to four clients during the feedback/comment period, and found similarly that the survey performed well, within the allotted time, and engendered positive responses from clients about the types of questions asked. As it is proposed to administer both the GPRA survey and GBHI in the same setting reducing burden and cost to clients and staff GPRA interviewers, we also piloted the survey with and without the GPRA in one setting. Our findings were that data quality was not reduced, clients did not experience the surveys as redundant and clients and interviewer did not experience an undue burden. The approach of combining the two survey administrations also has precedent in previous SAMHSA evaluations that were OMB-approved (Access to Recovery, OMB control number 0930-0299; Screening, Brief Intervention, Brief Treatment and Referral to Treatment Cross-site Evaluation, OMB control number 0930-0282; Targeted Capacity Expansion Program for Substance Abuse Treatment and HIV/AIDS Services, OMB control number 0930-0317).

Question 3. As the GBHI client survey will not require additional follow-up or tracking over and above the GPRA, which follow-up burden is included in the approved measure (0930-0208) and as the Grantee is required to maintain 80% retention as a condition of funding, tracking burden would be negligible. Purposefully, to reduce Grantee and client burden and be cost effective we proposed that the GBHI client interview be supplemented to the GPRA interview session and as noted above, is the procedure for several OMB approved SAMHSA evaluations (control numbers: 0930-0299; 0930-0282; 0930-0317).

Section 16:

What kind of statistics and reports are planning to use this data for once it is collected? These uses can be both internal to the GBHI program, internal to SAMHSA, and external to the public or other interested parties. Include a detail discussion of your analysis plan and table shells of your expected analysis.

Would this information be collected even if SAMHSA was not conducting this evaluation and other ways this data might be used outside of the GBHI program?

Can you add dates for the nonresponse follow-up to the schedule?

Response:

Question 1. The GBHI cross-site evaluation supplemental data will be combined with data from the CSAT GPRA Client Outcome Measures, information gathered from the Grantees describing their program components, and data from secondary sources such as SAIS GPRA and Technical Assistance data, the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) and the Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) to develop a comprehensive portrait of the GBHI client populations, the needs of these populations, the services provided to address those needs, and the outcomes across a multitude of domain areas for those participating in GBHI programs. These supplemental data will provide mediating and moderating variables, as well as information on client characteristics not covered by the CSAT GPRA survey. The areas addressed by the supplemental data collection include service need, burden, satisfaction/perception of care, the form of care or individually tailored care, model adaption, homelessness, housing (placement/safety/perceived choice/perceived value), readiness for change, and co-occurring mental disorders. Three additional domains (services, trauma and veteran’s service era and combat information) were added in response to the recommendations of the expert panel and SAMHSA and confirmed with the GBHI Grantees. The additional services data will improve our ability to describe the relationships between treatment plans and abstinence and housing stability including measuring the extent to which models of matching services to needs are being used and the appropriate dosage of services as described in the literature for these models. As CSAT GPRA data includes administrative data on services received only at discharge, it impossible to assess whether and how service receipt changes over time using only GPRA data alone. The GPRA data does not collect this information from the client or address perceived need and service matching. The supplemental data will address this limitation. Additionally, the panelists recommended measuring trauma symptoms given that trauma is prevalent in the homeless population (e.g., Browne & Bassuk, 1997; Goodman, 1991; Bassuk et al., 1996; Burt et al., 1999; HUD, 2009; Shelton et al., 2009) and without intervention consistently predicts negative substance abuse, employment, housing and criminal justice outcomes. Finally, given the high prevalence of homelessness among returning veterans and differentially by service era (Kline et al., 2009), along with there being several Grantee programs focused solely on veterans, baseline collection of veteran service era was recommended.

We conducted a literature review that helped advance our thinking about likely influences on client-, grantee-, and system-level outcomes (Broner et al., 2010). As we developed our data collection and analysis plans, we used information from the review to strengthen the evaluation’s ability to provide insightful findings on what works for whom, under what approaches, and in what systems and contexts. At the client level, demographic characteristics (sex, age, race or ethnicity), parental status, educational attainment, veteran status (for recent cohorts), disability, social supports, and involvement with the criminal justice system can be important with respect to understanding the appropriateness and expected effectiveness of specific approaches. Client differences in substance abuse, mental illness, and co-morbidity are of central importance to GBHI. Our data collection and analyses will allow us to describe how client populations differ on these factors across study sites and test whether these factors are associated with differential program choices, components and successful provision of services, including housing the clients. For example, by collecting gender at the client level, we will assess whether programs are better able to provide appropriate services for female clients than for male clients. Clients will also differ in their levels of participation, program completion, and treatment compliance. Information from the supplemental data collection will enhance the CSAT GPRA information from the SAIS discharge data to allow us to estimate what client characteristics are significantly associated with participation at 6 month follow-up and to test whether participation mediates the programs’ ability to carry out full services objectives.

The outcome evaluation component focuses on addressing the “utility” element of the evaluation’s Objective 1, which per SAMHSA’s RFA was is to “examine the feasibility, utility, and sustainability of future Treatment of Homeless cohorts through the review of planned and actual outcomes.” The outcome evaluation will focus on the changes in client outcomes that are associated with differences in grantee models. The findings will be framed in a pre-post quasi-experimental design that will allow us to examine the relationship of both intent-to-treat and service receipt from to outcomes. HLM will be used to estimate the mean change in client-level outcomes between baseline and follow-up. HLM is appropriate for these analyses because this modeling approach allows us to control for the clustering of clients within grantee. Within the HLM framework, we will adjust for client characteristics and other contextual factors. These adjusted mean changes will provide easy-to-understand estimates of possible program impact. Although these estimates are not intended to be causally interpreted, we do intend to compare them to estimates for similar models and populations in the scientific literature to confirm that they are within ranges that we would expect, conditional on the level of adherence to the models that we observe for each grantee. These estimates form a baseline for exploring how program decisions and characteristics alter service delivery and outcomes. In this way, variation among the 25 Grantees will serve as experimental variation for analyzing ‘key ingredients’ of models for achieving different outcomes, such as linking clients to certain types of housing. As appropriate, subgroup analyses will be conducted in which the data will be stratified by program type or client type to assess whether outcomes differ among the different types of programs or for different types of client (e.g., veterans or women).

Example table shells are provided below.

The first table shell describes patient transportation needs and receipts by several different grantee strata and for a given set of services. Specifically, we calculate proportions of patients answering affirmatively to questions SV11a and SV11b on the client survey for each relevant cell. Cells are constructed by the kind of service the client might need to receive, whether a grantee or grantee collaborator are providing the service, the geographic scenario for the client with respect to the service, and the type of transportation offered as part of the program.

Table 1. (Sample Table) Proportions (st. dev) of Clients Reporting Transportation Needs and Receipt (SV11a and SV11b): Stratified by Combinations of Transportation Options for Primary Services and Grantee Organizational Characteristics |

||||||||||||

|

|

In-person Services |

||||||||||

|

|

Provided by Grantee Organization |

|

Provided by non-Grantee Organization (e.g., local clinic, unemployment office, DMV) |

||||||||

Primary Transportation for Logistics for Service Provision |

Typical Residence of Consumers at main stage of Continuum of Care |

SATX OP |

MHTX OP |

Clinical CM |

Medical TX |

Housing or other Wraparound CM |

|

SATX OP |

MHTX OP |

Clinical CM |

Medical TX |

Housing or other Wraparound CM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Direct Provision of Transportation to Central Location |

On-site Central Location |

proportion (st. dev) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Off-site Cluster |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scatter-site |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Subsidized Transportation to Central Location |

On-site Central Location |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Off-site Cluster |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scatter-site |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Service Provided at Residence |

On-site Central Location |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Off-site Cluster |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scatter-site |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Service Provided at Central – No Transportation Support |

On-site Central Location |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Off-site Cluster |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scatter-site |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: Data are based on client survey responses at 6-month follow-up |

||||||||||||

The second table is an example of a model of what characteristics are associated with a client’s housing status at both baseline and follow-up. In addition to client characteristics, we plan to include yet tobe determined independent variables that capture the grantee’s program. Although not causal, the estimate for the indicator of 6-month follow-up provides a benchmark for comparing how well these models may have performed compared with published estimates from rigorous effectiveness studies.

Table Shell 2. Multinomial Logit Estimates of the of Housing Status

|

Shelter |

Residential SA Treatment |

Transitional Housing |

Permanent, Independent Housing |

Follow-Up Indicator |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Female |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Hispanic |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Black |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Asian |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

American Indian |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Native Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Alaska Native |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Other Race/Ethnicity |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Age |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Illicit Substance Use (Days) |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Mental Illness (Scale) |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Indicator of Client Reporting Transportation Needs |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

|

|

|

|

Vector of Grantee Model Characteristics |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

Notes: [MODEL INFORMATION]. N = # clients in rectangular analysis sample. P-values are given in parentheses below coefficient estimates. Reference category for dependent variable is “No Housing”. Male and White are reference categories for gender and race indicators. Random effects for clients nested within grantee random effects are used if a Hausman Specification Test does not preclude a random effects specification.

The second table also provides context for the third table in which an additional grantee characteristic, transportation efficacy, is included in a moderator analysis of housing status after six additional months in the program.

Table Shell 3. Moderating Influence of a Program’s Transportation Strength on its Ability to Link Clients to Housing, Estimates from a Multinomial Logit Model of Housing Status

|

Shelter |

Residential SA Treatment |

Transitional Housing |

Permanent, Independent Housing |

Transportation Efficacy (Scale)* Follow-Up Indicator |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.00 |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.00) |

|

Transportation Efficacy (Scale) |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.00 |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.00) |

|

Follow-Up Indicator |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Female |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Hispanic |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Black |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Asian |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

American Indian |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Native Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Alaska Native |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Other Race/Ethnicity |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Age |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Illicit Substance Use (Days) |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

Mental Illness (Scale) |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Indicator of Client Reporting Transportation Needs |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

|

|

|

|

|

Vector of Grantee Model Characteristics |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

Notes: [MODEL INFORMATION]. N = # clients in rectangular analysis sample. P-values are given in parentheses below coefficient estimates. Reference category for dependent variable is “No Housing”. Male and White are reference categories for gender and race indicators. Random effects for clients nested within grantee random effects are used if a Hausman Specification Test does not preclude a random effects specification. Transportation Efficacy is a continuous scale derived from qualitative data analyses. The interaction term in the first row represents the moderating influence of a program’s transportation characteristics on its ability to link clients to housing.