Attachment B - Informed Consent - Health Care Professionals Training Module

Revised Attachment B - HCP module REVISED.docx

Improving Hospital Informed Consent with Training on Effective Tools and Strategies

Attachment B - Informed Consent - Health Care Professionals Training Module

OMB: 0935-0228

I mproving

Hospital Informed Consent with an Informed Consent Toolkit

mproving

Hospital Informed Consent with an Informed Consent Toolkit

Contract # HHSA290201000031I / TO 3

Deliverable 3.1.1

DRAFT STORYBOARD

FOR PILOT TEST

Making Informed Consent an Informed Choice: Training for Health Care Professionals

October 6, 2014

Prepared for:

Cindy Brach, MPP

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Submitted by:

Abt Associates Inc.

55 Wheeler

Street

Cambridge, MA 02138

Introduction

In medical care, informed consent is a process of communication between clinician and patient that results in the patient's authorization or agreement to undergo a specific medical intervention. All too frequently, however, patients do not understand the benefits, harms and risks and alternatives of their treatments even after signing a consent form.

In response to this challenge, Abt Associates, the Joint Commission, the Fox Chase Cancer Center and Temple University have been contracted by AHRQ to develop, test and make available to hospitals and the medical community an improved Toolkit on informed consent to medical treatment. This toolkit will draw from several sources, including:

A Practical Guide for Informed Consent, developed by Suzanne Miller and Linda Fleisher (Temple University) with funding by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Rozovsky F. Consent to Treatment: A Practical Guide, 4th Ed.(2013). Aspen Publishers.

Preliminary research including an updated environmental scan of the peer-reviewed and grey literature on informed consent

Input from an expert and stakeholder panel

The toolkit will be delivered in the form of two training modules, each providing approximately 1 hour of continuing medical education, to be pilot-tested through the Joint Commission’s Learning Management System. One training module will be designed for health care professionals, the other for hospital leaders.

The present document is the draft toolkit for health care professionals. It is presented as a storyboard. Once the storyboard is finalized, it will go into production and, upon satisfactory completion of the production process, it will be uploaded into the learning management system for pilot-testing.

Project name |

AHRQ Informed Consent Toolkit |

Course Title |

Making Informed Consent an Informed Choice: Training for Health Care Professionals |

Slide 1: Welcome and Overview |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Present the education accreditation notes in a smaller font or on a scrolling screen to limit learner interference |

Making Informed Consent an Informed Choice: Training for Health Care Professionals

Informed Consent requires clear communication about choices. It is not a signature on a form.

Goal

Informed Consent Informed Choice

Overview

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) with funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Contract No. HHSA290201000031I, Task Order #3. The authors of this module are responsible for its content. No statement may be construed as the official position of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Joint Commission is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians. – ACCME Accreditation Statement Policy |

Making Informed Consent an Informed Choice: Training for Health Care Professionals.

Welcome and THANK YOU for your interest in improving the informed consent process for your patients. Informed consent for medical treatment requires clear communication about choices. It’s not a signature on a form; it’s a communication process in which a patient is given information about his or her options for medical test, treatments or procedures, and then selects the option that is the best fit for his or her goals and values.

The goal of this course is to help you make informed consent an informed choice. In this course, you will find:

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) with funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Contract No. HHSA290201000031I, Task Order #3. The authors of this module are responsible for its content. No statement may be construed as the official position of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Joint Commission is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians. |

Slide 2: Course Scope |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

In the resources section: please link to these resources on informed consent to research: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/education/index.html http://www.ahrq.gov/funding/policies/informedconsent/index.html

Please also include this legal reference on end-of-life care: Rozovsky, FA (2013). Refusing treatment, dying and death, and the elderly. Section 10.6, pp.10-23 –10-30. In: Consent to Treatment: A Practical Guide. 4th ed. New York, NY: Aspen Publishers: Wolters-Kluwer Law & Business. |

Course Scope

This course focuses on informed consent for medical treatment.

It does not focus on:

See “Resources” for references on these topics.

This course is for:

|

Course Scope

Please note that this course focuses on informed consent to medical treatment.

It does not focus on blanket consent forms that patients sign upon admission to a hospital, since such forms provide very little information to patients.

It also does not focus on informed consent for research, nor on advance directives for end-of-life care.

If you wish to learn more about informed consent for research or advance directives, please see the “resources” section of this course.

This course is both for clinicians who obtain informed consent, and for other health care professionals. |

Slide 3: Learning Objectives |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Learning Objectives:

|

Learning objectives:

By the end of this course, you will be able to:

|

Slide 4: Contents of CE activity |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Course Contents

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Section 2: Strategies for Clear Communication

Section 3: Strategies for Presenting Choices

Section 4: Documenting and Confirming Informed Consent and being Part of a Team

All sections of this activity are required for continuing education credit.

|

This information in this course is organized into 4 sections.

The first section will review the principles of informed consent. We’ll examine existing problems with the process of informed consent for health care, the principles of informed consent and the implications for a good informed consent process.

Informed consent requires clear communication about choices, so in Sections 2 and 3 of this course, we’ll discuss strategies for clear communication and presenting choices. When you’re done with those sections you’ll have learned 10 strategies to make informed consent an informed choice.

Strategies for clear communication include preparing for the informed consent discussion, using health literacy universal precautions, removing language barriers, and using teach-back.

Strategies for presenting choices include offering choices, engaging the patient and their family and friends, eliciting the patient’s goals and values, encouraging questions, showing high-quality decision aides, and explaining the benefits, harms, and risks of all options.

Finally, in Section 4 we’ll talk about how to document and confirm consent, and what roles various health care team members can play in the informed consent process. All sections of this activity are required for continuing education credit.

|

Slide 5: Course Navigation |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Please update navigation instructions as necessary.

Please provide an option for closed captioning so that the module will be 508 compliant

Note to programmers – use BACK not PREV for the button name. |

|

Before you get started, please take a moment to learn how to navigate in this course:

If you exit the course before it is over, you’ll be asked if you want to resume (where you left off) the next time you watch the course.

|

Slide 6: Authors and Disclosures |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Scroll to view authors/planners |

Authors and Disclosures As an organization accredited by the ACCME and the ANCC, Joint Commission Resources requires everyone who is a planner or faculty/presenter/author to disclose all relevant conflicts of interest with any commercial interest. Nurse Planners Name Jill Chmielewski, RN, BSN, MJ Title: Associate Project Director, The Joint Commission Disclosure: Jill Chmielewski has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Physician Planner Name: Daniel Castillo, MD Title: Medical Director, Division of Healthcare Quality Evaluation, The Joint Commission. Disclosure: Dr. Castillo has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Planning Committee Members Name: Cindy Brach, MPP Title: Senior Health Policy Researcher, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Disclosure: Ms. Brach has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Melanie Wasserman, PhD, MPA Title: Senior Associate, Abt Associates Disclosure: Dr. Wasserman has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Salome, Chitavi, PhD Title: Project Director, The Joint Commission Disclosure: Dr. Chitavi has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Linda Fleisher, PhD, MPH Title: Senior Scientist, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Disclosure: Dr. Fleisher has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Suzanne Miller, PhD Title: Professor, Fox Chase Cancer Center Disclosure: Dr. Miller has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Sarah Shoemaker PhD, PharmD Title: Senior Associate, Abt Associates Disclosure: Dr. Shoemaker has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Dina Moss, MPP Title: Senior Science Analyst, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Disclosure: Ms. Moss has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Technical Advisory Panel Name: Mary Ann Abrams, MD, MPH Title: Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Ohio State University College of Medicine and Nationwide Children’s Hospital Disclosure: Dr. Abrams has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: David Andrews Title: Patient Advisor, Georgia Regents Medical Center Disclosure: Mr. Andrews has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Ellen Fox, MD Title: Executive Director, National Center for Ethics in Health Care, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Disclosure: Dr. Fox has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Barbara Giardino, RN, BSN, MJ, CPHRM, CPPS Title: Risk Manager, Rockford Health System, Illinois Disclosure: Ms. Giardino has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Jamie Oberman, MD Title: Navy Medical Corps Career Planner, Office of the Medical Corps Chief, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Disclosure: Dr. Oberman has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Yael Schenker, MD, MAS Title: Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, Section of Palliative Care and Medical Ethics, University of Pittsburgh Disclosure: Dr. Schenker has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Faye Sheppard, RN, MSN, JD, CPHRM, CPPS, FASHRM Title: Principal, Patient Safety Resources, Inc. Disclosure: Ms. Sheppard, Esq. has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Jana Towne, BSN, MHCA Title: Nurse Executive, Whiteriver Indian Hospital Disclosure: Ms. Towne has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Dale Collins Vidal, MD, MS Title: Professor of Surgery, Giesel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and Chief of Plastic Surgery, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center Disclosure: Dr. Collins Vidal has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Matthew Wynia, MD, MPH, FACP Title: Director, Institute for Ethics & Center for Patient Safety, American Medical Association Disclosure: Dr. Wynia has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Credits Available ACCME ANCC ACHE IACET

There are no fees for participating in or receiving credit for this online educational course.

A certificate of CE/CME is available for print at the end of each module.

Original release date: xx-xx-xxxx Last reviewed: xx-xx-xxxx Termination date: xx-xx-xxxx Joint Commission Resources is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians. Joint Commission Resources takes responsibility for the content, quality, and scientific integrity of the CME activity. Joint Commission Resources designates this educational activity for the listed contact hours of AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. Joint Commission Resources is also accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s Commission on Accreditation. Joint Commission Resources designates this continuing nursing education activity for the above listed contact hours. Joint Commission Resources is provider approved by the California Board of Registered Nursing, provider number CEP 6381, for the listed contact hours. Joint Commission Resources is authorized to award the listed hours of pre-approved ACHE Qualified Education credit for this program toward advancement or recertification in the American College of Healthcare Executives. Participants in this program wishing to have the continuing education hours applied toward ACHE Qualified Education credit should indicate their attendance when submitting application to the American College of Healthcare Executives for advancement or recertification. The Joint Commission Enterprise has been accredited as an Authorized Provider by the International Association for Continuing Education and Training (IACET). |

Authors and Disclosures As an organization accredited by the ACCME and the ANCC, Joint Commission Resources requires everyone who is a planner or faculty/presenter/author to disclose all relevant conflicts of interest with any commercial interest. Nurse Planners Name Jill Chmielewski, RN, BSN, MJ Title: Associate Project Director, The Joint Commission Disclosure: Jill Chmielewski has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Physician Planner Name: Daniel Castillo, MD Title: Medical Director, Division of Healthcare Quality Evaluation, The Joint Commission. Disclosure: Dr. Castillo has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Planning Committee Members Name: Cindy Brach, MPP Title: Senior Health Policy Researcher, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Disclosure: Ms. Brach has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Melanie Wasserman, PhD, MPA Title: Senior Associate, Abt Associates Disclosure: Dr. Wasserman has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Salome, Chitavi, PhD Title: Project Director, The Joint Commission Disclosure: Dr. Chitavi has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Linda Fleisher, PhD, MPH Title: Senior Scientist, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Disclosure: Dr. Fleisher has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Suzanne Miller, PhD Title: Professor, Fox Chase Cancer Center Disclosure: Dr. Miller has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Sarah Shoemaker PhD, PharmD Title: Senior Associate, Abt Associates Disclosure: Dr. Shoemaker has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Dina Moss, MPP Title: Senior Science Analyst, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Disclosure: Ms. Moss has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Technical Advisory Panel Name: Mary Ann Abrams, MD, MPH Title: Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Ohio State University College of Medicine and Nationwide Children’s Hospital Disclosure: Dr. Abrams has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: David Andrews Title: Patient Advisor, Georgia Regents Medical Center Disclosure: Mr. Andrews has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Ellen Fox, MD Title: Executive Director, National Center for Ethics in Health Care, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Disclosure: Dr. Fox has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Barbara Giardino, RN, BSN, MJ, CPHRM, CPPS Title: Risk Manager, Rockford Health System, Illinois Disclosure: Ms. Giardino has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Jamie Oberman, MD Title: Navy Medical Corps Career Planner, Office of the Medical Corps Chief, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Disclosure: Dr. Oberman has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Yael Schenker, MD, MAS Title: Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine, Section of Palliative Care and Medical Ethics, University of Pittsburgh Disclosure: Dr. Schenker has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Faye Sheppard, RN, MSN, JD, CPHRM, CPPS, FASHRM Title: Principal, Patient Safety Resources, Inc. Disclosure: Ms. Sheppard, Esq. has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Jana Towne, BSN, MHCA Title: Nurse Executive, Whiteriver Indian Hospital Disclosure: Ms. Towne has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Dale Collins Vidal, MD, MS Title: Professor of Surgery, Giesel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and Chief of Plastic Surgery, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center Disclosure: Dr. Collins Vidal has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Name: Matthew Wynia, MD, MPH, FACP Title: Director, Institute for Ethics & Center for Patient Safety, American Medical Association Disclosure: Dr. Wynia has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Credits Available ACCME ANCC ACHE IACET

There are no fees for participating in or receiving credit for this online educational course.

A certificate of CE/CME is available for print at the end of each module.

Original release date: xx-xx-xxxx Last reviewed: xx-xx-xxxx Termination date: xx-xx-xxxx Joint Commission Resources is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians. Joint Commission Resources takes responsibility for the content, quality, and scientific integrity of the CME activity. Joint Commission Resources designates this educational activity for the listed contact hours of AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. Joint Commission Resources is also accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s Commission on Accreditation. Joint Commission Resources designates this continuing nursing education activity for the above listed contact hours. Joint Commission Resources is provider approved by the California Board of Registered Nursing, provider number CEP 6381, for the listed contact hours. Joint Commission Resources is authorized to award the listed hours of pre-approved ACHE Qualified Education credit for this program toward advancement or recertification in the American College of Healthcare Executives. Participants in this program wishing to have the continuing education hours applied toward ACHE Qualified Education credit should indicate their attendance when submitting application to the American College of Healthcare Executives for advancement or recertification. The Joint Commission Enterprise has been accredited as an Authorized Provider by the International Association for Continuing Education and Training (IACET). |

Slide 7: Principles of Informed Consent |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Jamie: we’ve put running headers with the section name on each slide |

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Why does informed consent need to be improved?

A good informed consent process can:

Problems with informed consent:

|

In Section 1 we’ll learn about the principles of informed consent, starting with addressing the question of why informed consent needs to be improved.

Patients and health care teams alike benefit when a patient’s consent to treatment is fully informed as the result of a clear, comprehensive, and engaging communication process.

A good informed consent process has many advantages. It helps patients to make informed decisions, strengthens the therapeutic relationship, and can improve follow-up and after-care. When patients and their families understand the benefits, harms, and risks in advance, they can be partners in patient safety, and they can better cope with any poor outcomes that may happen as a result of treatment. This makes it less likely that the patient would sue the clinician when a poor outcome occurs.

Unfortunately, there are many problems with the informed consent process in hospitals today.

Both clinicians and patients often treat informed consent as a nuisance, a formality, and an obstacle on the way to care.

This is a problem, because even after signing a consent form, many patients don’t understand basic information about the benefits, harms, and risks of their proposed treatment, including the possibility of poor outcomes.

As a result, informed consent is one of the top 10 most common reasons for medical malpractice suits.

|

Slide 8: When “informed” consent isn’t informed |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

JAMIE: VISUAL

Show last 1:45 minutes of video clip of Toni talking: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubPkdpGHWAQ. This is not a good quality clip, but it can be extracted from the AMA health literacy video.

When audio on Art starts, add picture of Art (use a stock photo, or we can ask the person who contributed this story, Audrey Riffenburg, if she would share a real picture). When the quote from Art begins (i.e., What the hell do you mean…), add conversation balloon.

When audio on Dai starts, add his picture (use a stock photo) and the buttons.

|

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

When “informed” consent isn’t informed

Picture of Toni with link to video. Caption: Toni Cordell had a hysterectomy without realizing it.

Picture of older White male in a hospital bed with doctor standing next to him. Conversation bubble, “What do you mean! I’m not going to be able to talk?”

Picture of young Vietnamese man with injured arm. Caption:

|

Examples of failures in informed consent include the story of Toni Cordell. Toni had a hysterectomy without realizing the procedure recommended to solve her “woman’s problem” was the removal of her uterus.

Click on the picture of Toni to hear her describe what happened.

While Toni’s experience was not recent, failures in informed consent happen in hospitals every day.

Take Art, for example. He agreed to have surgery to remove throat cancer after his doctor explained it using terms like “laryngectomy,” “palliative trach,” “ventilator problems,” “bronchiecstasis,” and “purulent bronchitis.” Then his adult daughter explained, “Dad, what the doctor is saying is that with the surgery, you would have your voice box taken out. You wouldn’t be able to talk anymore. You’d have a breathing hole through the front of your throat for the rest of your life. You’d have to keep the hole protected so germs couldn’t go straight into your lungs. And you’d have a tube in your breathing pipe that you’d have to take care of every day.” Art was surprised and got angry. He asked, “What the hell do you mean! I won’t be able to talk?!”

Let’s look at one more case. Dai is a young agricultural worker who speaks only Vietnamese. He arrived at the hospital with a badly injured arm. The hospital wanted to perform an invasive diagnostic test and gave Dai a poorly translated consent form to sign. Dai signed it, because he thought that if he didn’t, he wouldn’t be given pain reliever.

Since these patients weren’t truly informed, we can’t say that they gave informed consent. |

Slide 9: Ethical Principles and Legal Standards |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Principle of Autonomy

P

Patients’ Rights to Informed Consent:

|

The ethical principle of autonomy gives patients the right to decide what happens to their bodies.

The legal doctrine on informed consent in health care has evolved over time and varies from state to state. But in every state, by law, patients have the right to:

|

Slide 10: Ethical Principles and Legal Standards |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Legal Standard for “Adequate Disclosure”:

|

State law defines what constitutes adequate disclosure – what you are required to tell patients.

In most states, adequate disclosure is the duty of the clinician who is providing the treatment. It can’t be delegated to another person. The information to be disclosed must include:

Many states have additional requirements. |

Slide 11: It’s Not About the Form |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Digital Ignite to explore opportunities for interactive learning for this slide |

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Signed Form ≠ Informed consent

L

S Risk

Liability

[Picture of MD talking to patient with question marks over patient’s head?]

“The statute requires a physician to "explain" the treatment, alternatives, and risks to his or her patient. ‘Explain’ means ‘to make plain or understandable: clear of complexities or obscurity’…. Explanation implies more than a mere correct statement of the facts. An explanation clarifies an issue or makes it understandable to the recipient …. For example, a physician can mouth words to an infant, or to a comatose person, or to a person who does not speak his or her language, but unless and until such patients are capable of understanding the physician’s point, the physician cannot be said to have explained anything to any such person.”

Macy v. Blatchford case, Oregon Supreme Court, 2000) |

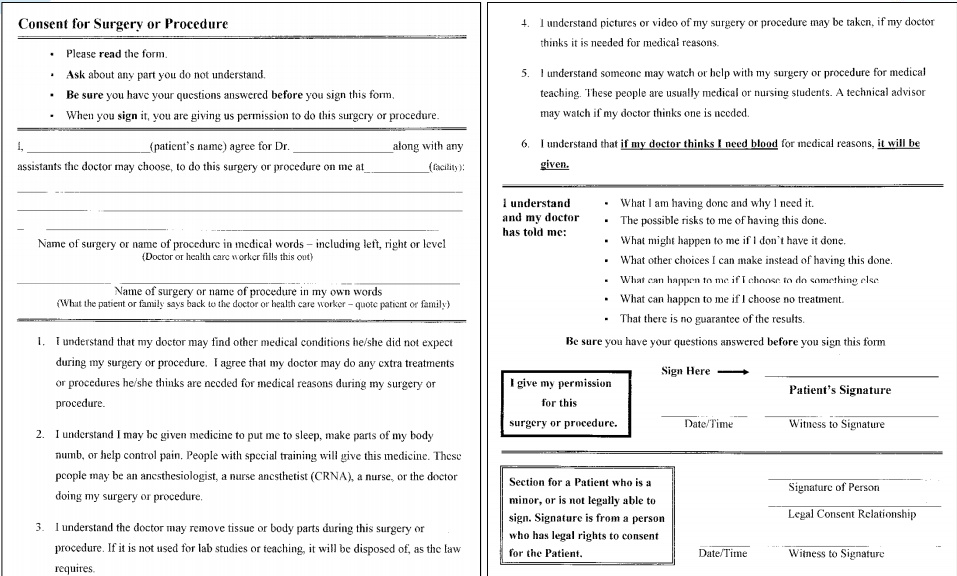

In the previous slide we described what clinicians have to tell patients as part of obtaining their consent. But telling patients isn’t enough for consent to be informed, even if patients sign the form.

The consent form exists to document that the patient has been provided information, understood the information and agreed to a particular test, treatment, or procedure. A signed consent form actually implies that prior to the patient’s signing, a process of adequately informing the patient and ensuring understanding has taken place. Yet, many patients sign informed consent forms even when they don’t understand the procedure, its benefits, harms, risks, or alternatives to treatment.

If the patient didn’t understand the information presented, it’s a patient safety problem, and you could be sued.

For example, in the Macy versus Blatchford case the Oregon Supreme Court, discussing whether a physician failed to obtain a patient’s informed consent for surgery, made the point that informing without understanding does not constitute informed consent. The court stated, “The statute requires a physician to "explain" the treatment, alternatives, and risks to his or her patient. ‘Explain’ means ‘to make plain or understandable: clear of complexities or obscurity’…. Explanation implies more than a mere correct statement of the facts. An explanation clarifies an issue or makes it understandable to the recipient …. For example, a physician can mouth words to an infant, or to a comatose person, or to a person who does not speak his or her language, but unless and until such patients are capable of understanding the physician’s point, the physician cannot be said to have explained anything to any such person.” |

Slide 12: Recognizing patient capacity for decision-making |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

JAMIE: consider bringing in bullets 1 by 1 with audio guidance – these are key points that need to be emphasized on-screen. I’m also open to other options to achieve that goal.

JAMIE: Let us explore alternative ways to stress the key points in this slide without using bullet points (graphics, images etc).

Consider making the 3rd and fourth bullets interactive (show the story, offer “yes/no” buttons, feedback to learner whether they got it right, then show the right answer

Add to the resources section this document on minors’ right to consent: https://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_OMCL.pdf

Link to Resources: FAQs for patients that lack decision making capacity.

|

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Patient capacity for decision-making

Most patients have capacity for decisions about medical treatment.

Key criteria for patient capacity:

- Their condition - Options - Benefits, harms and risks

Capacity can change over time and can vary depending on the decision to be made.

What’s not incapacity:

|

Patient capacity for decision-making

To uphold a patient’s right to participate in decisions about their care, it is important to recognize their capacity for decision-making.

The main thing to remember is that most patients have capacity for decision-making about their medical care and treatment.

Sometimes a patient is perceived as not having the ability to make an informed decision due to signs of intoxication, mental illness, cognitive impairment, or other factors.

In some cases, that perception is right, but in many cases, it is not.

Key to assessing the patient’s capacity is whether the patient:

Capacity is both the ability and the right to make a decision. It can change over time, and can depend on the decision to be made.

Patients don’t automatically lack capacity just because they disagree with the care team’s treatment plan. This is true even if members of the care team strongly disagree with the patient’s choice and think they know what’s best for the patient. Patients may refuse treatment even if it puts their lives in jeopardy.

Also, just because some patients can’t speak, have an intellectual or physical disability, mental illness, or cognitive impairment, or are under the influence of alcohol or pain medications, that does not automatically mean they lack capacity to make a decision. These conditions can make it harder to communicate and make decisions, though later in this course we’ll share some communication strategies that can help. |

Slide 13: When to consult an authorized representative |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

JAMIE: When narrator says, “Click on the label ‘Authorized representative, show this text:

For minors: the authorized representative is a parent or legal guardian (show a picture of a mom next to a hospital bed with a young child in it with arrow pointing to mom saying “Authorized representative (Mom)” [or use a picture of a Dad next to hospital bed with young child, with the label “Authorized representative (Dad)”]

For adults: an authorized representative can either be designated by the patient (health proxy) or designated by someone other than the patient who has authority (for example the hospital policy can establish a hierarchy of authorized representatives in the absence of a proxy, typically spouse first, then adult children, then siblings, then other relatives).

The Cecile story is a true story of Cindy’s. She can record it. |

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Except:

Consult an authorized representative

Picture of Cecile [Caption: Click here to hear Cecile’s real life story on informed consent in an emergency situation.]

|

The patient’s family and friends often play an important role in the decision-making process, but in most cases, the final decision rests with the patient.

There are some exceptions to this rule, namely:

In these cases, you will need to consult with someone who is legally authorized to make a decision on the patient’s behalf. Click on the label “Authorized Representative,” to learn more about who can serve as an authorized representative.

Even when you’re working with an authorized representative, sharing information with the patient can help them to feel included, respected, and more comfortable with the care they are receiving.

A last exception is a life- or health-threatening emergency leaving no time to identify or speak with an authorized representative. In that case, the clinician can make a decision in the patient’s best interests. But often there’s still time to hold a consent discussion in emergency situations. Click on Cecile to hear her story about informed consent in an emergency.

Cecile: My father was recovering from minor surgery when I noticed he was trying to say something but was having trouble coming up with the words. I called in the nurse practitioner, and he decided to call the stroke team. Well, the stroke team arrived, performed an assessment, and started to wheel my father out the door. “Where are you taking him?” I asked. “To give him medicine to break up the blood clot,” they said. I said, “But you haven’t gotten consent.” “It’s an emergency!” they called, halfway out the door. But I was my father’s health proxy and I called after them, “You can’t give him anything until I consent.” That caught them short. “You’re right,” they agreed. “Can you walk with us while we tell you about this medicine?” And I did. I understand they were in a rush – they had to give him the medicine within 3 hours of his first symptoms, but that didn’t mean they didn’t have time to get consent.

Informed consent rules vary state-by-state and hospital-by-hospital, so check your hospital policy or state laws for further guidance.

|

Slide 14: Making Informed Consent an Informed Choice |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

JAMIE: During first paragraph have the word “consent” morph into the word “choice |

Section 1: Principles of Informed Consent

Informed Consent Informed Choice

Informed choice requires:

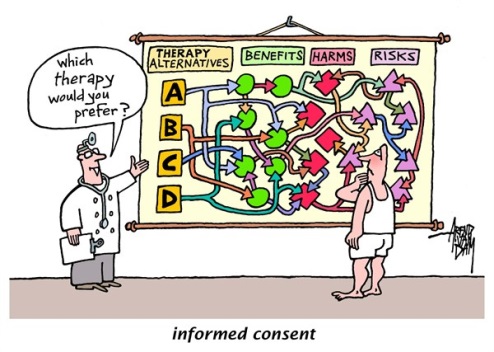

Of course, the information must be presented in a way the patient can understand. [We will contact the author of this cartoon for permission. http://www.cagle.com/tag/informed-consent/]

|

The goal of this course is to help you make informed consent an informed choice for your patients. Let’s talk about what that means.

What we often see in informed consent discussions is that a clinician will recommend a treatment, explain the treatment, and then get the patient’s consent to deliver the treatment.

This may satisfy the minimum requirements for informed consent, but to truly make an informed choice, patients need clear, unbiased medical information they can understand about all their treatment options, including what happens if they decide to do nothing.

This is challenging, because clinicians may not always be in a position to provide information about all the options.

In addition to considering all the options, to make an informed choice patients have to factor their goals and values into the decision.

Of course, in order for a patient to make an informed choice, the information about the choices must be presented in a way that the patient can understand.

|

Slide 15: Section 2. Strategies for Clear Communication |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Section 2. Strategies for Clear Communication

Strategy 1: Prepare for the Informed Consent Discussion Strategy 2: Use Health Literacy Universal Precautions Strategy 3: Remove Language Barriers Strategy 4: Use Teach-Back |

The second section of this course describes four strategies for clear communication during the informed consent process.

The first strategy is to prepare for the informed consent discussion by gathering all the information you’ll need and giving some thought to the way you’ll organize the discussion.

The second strategy is to use health literacy universal precautions, such as using plain language with all patients.

The third strategy is to identify and remove language barriers that arise when patients have limited English proficiency, including those with hearing impairments.

The fourth strategy is to use teach-back to make sure you’ve explained the choices in a way that the patient, their family and friends have understood.

|

Slide 16: Strategy 1. Prepare for the Informed Consent Discussion |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Section 2. Strategies for Clear Communication

Strategy 1: Prepare for the Informed Consent Discussion.

[Picture of Tanya – middle aged African American] |

The first strategy is to prepare for the informed consent discussion. To get ready, you’ll need to attend to several details.

Make sure you have the results of any relevant diagnostic tests available. When possible, share easy-to-understand results with your patients ahead of time.

Ask your patients if there are people whose opinions are important to them or whose support they would like to have during the discussion. If there are, plan to hold the discussion in a room that’s big enough to comfortably include everyone.

The space should also be private enough so that others won’t overhear confidential information about the patient.

Scheduling is important too. Schedule a time when everyone who should be there can attend. Think about whether it’s the right time to have an informed consent discussion. A patient who has just been told their diagnosis may not be ready to talk about the treatment options. Similarly, if your patient is impaired by alcohol, medications, or anxiety and immediate treatment is not required, wait until your patient is better able to hear the choices.

Consider how long the discussion is likely to take, and plan enough time for the discussion. Think about whether you might need more than one discussion session. Click on Tanya to hear how one clinician handled the situation when a discussion went longer than anticipated.

Audio clip in woman’s voice: My husband and I were close to reaching a decision with my husband’s doctor about a procedure she would perform the following week. The doctor thought we were done and was making for the door. But I still had lots of questions. So I said, “Look, I know that this is a routine procedure for you. But it isn’t for us. We have questions that we’d like to get answered before we proceed.” She looked uncomfortably at the door, and I knew she was thinking of the patients in her waiting room. She said, “I’ll tell you what. I’ve got two more patients to see. If you can wait, I’ll come back and we can talk more.” So we waited for half an hour. Then true to her word, she came back and answered all our questions. |

Slide 17: Strategy 2. Remove Communication Barriers |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

JAMIE: Explore using a word cloud or other presentation rather than bullet points to depict these challenges?

(If you use a word cloud, consider having the words jump out of the cloud when the audio speaks them.)

Can you double-check that we are meeting 508 compliance guidelines here? The audio is a fair bit longer than the on-screen content, so we are wondering about that. |

Challenges to effective communication

|

Informed consent requires good communication between clinicians and patients, but effective communication can be challenging. Many factors can contribute to the challenges.

During the informed consent discussion, patients are rarely at their best. They may be feeling ill, scared, or stressed. They may feel intimidated by people in white coats. They may not be able to hear everything you’re saying, tending to focus on the negative aspects of the choices you’re presenting – the harms and risks, without giving equal weight to the benefits.

Language can also be a barrier. As clinicians we often use medical terms that most patients won’t understand. Even if we use simple language, sometimes the concepts are hard to understand. For example, many Americans have trouble understanding numerical expressions of risk.

Patients who are not proficient in English face additional language barriers. According to the Census, almost 9 % of the U.S. population has limited English proficiency. If you are not certified as being proficient in your patient’s preferred language, then there’s a language barrier between you. Translated forms alone can’t remove that barrier, because not all patients can read the language they speak, and a form alone can’t take the place of an informed consent conversation. There also may be cultural differences between you and your patient. Without realizing it, you may be talking past each other. Some patients face additional challenges, such as limited health literacy. Over a third of U.S. adults—77 million people—have difficulty with common health tasks, such as following directions on a prescription drug label or understanding a chart showing a childhood immunization schedule. These patients often hide their difficulty reading or understanding, and you can’t tell by looking who they are because they come from every walk of life.

Being deaf or hard of hearing is another communication barrier, and vision impairments can make it hard or impossible to read consent forms.

Learning style matters too. Visual learners learn best from written materials and pictures; auditory learners learn best when they hear an explanation; and kinesthetic learners learn best when they can touch or experience something related to what’s being said.

Patients with cognitive impairment or intellectual disabilities often have capacity for decision-making and shouldn’t automatically be treated as incompetent.

The final challenge is the time pressure we all face. While we’d all like to be generous with our time, the truth is that spending more time than scheduled with one patient means you have to short-change another patient. Fortunately, with practice you can learn to remove communication barriers efficiently. |

Slide 18: Use health literacy universal precautions |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

For 2nd bullet: could have a picture of an MD talking to patient in exam room morph into patient sitting on living room couch.

Make an interactive game out of plain language. Examples of common, everyday language:

Resource: Tool 5: Tips for Communicating Clearly from AHRQ’s Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit.

Jamie, see right hand column. Can we hover over ALD for the definition?

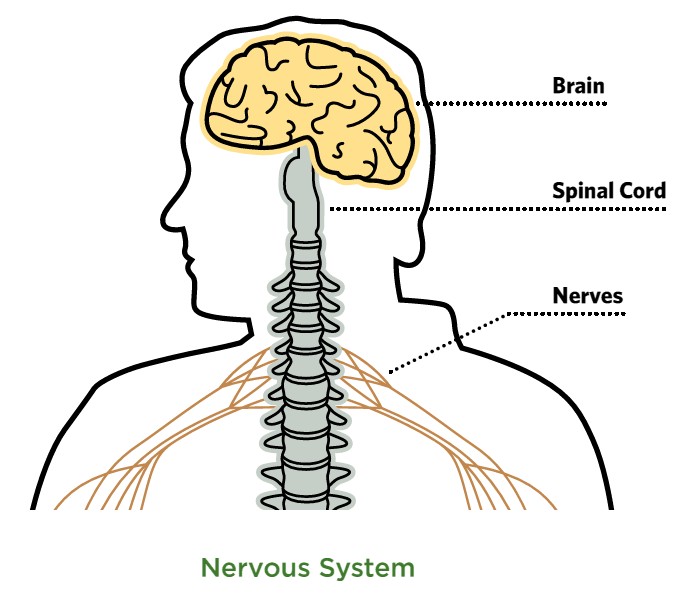

The picture of the nervous system is from http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/tools/LeadGlossary_508.pdf. What’s the best way to reference it? |

Section 2. Strategies for Clear Communication

Strategy 2: Use Health Literacy Universal Precautions

|

Many communication barriers can be removed by our second strategy, adopting “health literacy universal precautions.” These are techniques to communicate clearly and check understanding for every patient or family member involved, because everyone, no matter how well educated, is at risk of misunderstanding sometimes.

First, clinicians often use medical jargon without even realizing it. It’s how we were trained to speak. But your patients won’t follow what you’re saying if you use unfamiliar terms. Try to use language that you’d use while talking to your uncle in your living room. The simpler the words the better. Don’t worry that your patients will feel insulted, as if you’re talking down to them. No matter how well educated, everyone appreciates clear and simple explanations.

Second, speaking slowly is another important aspect of health literacy universal precautions. Your patients’ processing speed may decrease because they feel unwell or are afraid, or because of cognitive impairments or intellectual disabilities. Even under the best of circumstances, the new concepts you’re introducing may sound like a torrent of words if you don’t make an effort to slow down and speak at a comfortable pace. And for patients who can only handle a little bit of information at a time, you may need to break up the conversation into several sessions.

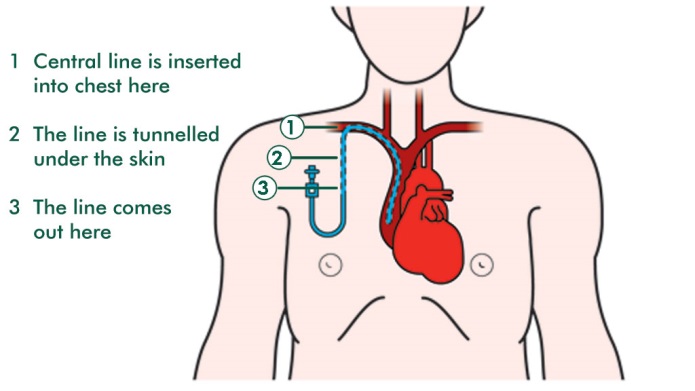

Third, in addition to explaining the information, use visuals to help get your point across. Visuals can be as simple as a picture you draw. Use clear and uncluttered illustrations, such as this picture of the nervous system. Think about whether there is anything you can let patients touch or experience – such as a computer touchscreen, a 3-D model of the body parts you’re talking about, a piece of equipment that will be used for their procedure, or a brief tour of the operating room in settings where that’s practical.

Fourth, repeating key points gives your patient a second chance to take in important information. Be as specific and concrete as you can to reinforce the information you have shared.

Fifth, patients may be hard of hearing but usually get by without a hearing aid. Since you want your patients to hear every word of the informed consent discussion, politely offer assistive listening devices to all patients you suspect have hearing difficulties. You can also try to find a quieter space for the informed consent discussion, and make sure to face the patient when you talk.

Similarly, for patients with low vision, you can offer magnifying readers, make sure the lighting is strong enough to read, and offer to read forms aloud.

Sixth, check that your patient understands. Teach-back is a useful technique that we’ll discuss in more detail a little later in this course. |

Slide 19: Do’s and don’ts of communicating with patients with limited English proficiency |

|

|||||||||||||||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

||||||||||||||

JAMIE - Please create a drag and drop exercise, with audio files in comments playing when learner places a phrase in the right column.

Show Gayle Tang’s picture when her audio clip is playing

Include this reference in the resources section on the dangers of not using a professional medical interpreter: Flores G, Abreu M, Barone CP, Bachur R, Lin H. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: a comparison of professional versus ad hoc versus no interpreters. Annals of emergency medicine. Mar 14 2012. |

|

Our third strategy is to overcome language barriers. Your hospital probably has a policy that guides communicating with patients with limited English proficiency, including those who use sign language instead of English. Make sure you’re familiar with your hospital’s policies. Remember, failure to use interpreters is risky for patients and can serve as the basis for lawsuits.

When conducting an informed consent discussion with a person whose native language is not English, there are some do’s and don’ts. See if you can sort the following actions into the “do’s” or “don’ts” column.

Listen to Gayle Tang, Senior director of National Diversity & Inclusion for Kaiser Permanente. “In my everyday life, I’m very proficient in English. I design and run an interpreter training program. But when I was faced with my own troubling diagnosis, my English fell away. I don’t get sick in English, I get sick in Chinese. When it was time to talk to the doctor about what was wrong with me and what my options were, I needed an interpreter.” |

||||||||||||||

Slide 20: More Do’s and Don’ts of Interpreter Services |

|

|||||||||||||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

||||||||||||

JAMIE - Please create a drag and drop exercise, with audio files in comments playing when learner places a phrase in the right column.

|

|

[see pop-ups] |

||||||||||||

Slide 21: Strategy 4. Use teach-back to check patient understanding |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Include a reference to this website on teach-back training in the resources section: http://www.teachbacktraining.org/

|

Section 2. Strategies for Clear Communication Strategy 4: Use Teach-Back

What is teach-back?

|

Now let’s learn about Strategy 4: Using teach-back to check patient understanding

Teach-back is a widely used technique to check for understanding. In the informed consent context:

|

Slide 22: Why use teach-back? |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Section 2. Strategies for Clear Communication Strategy 4: Use Teach-Back

Why use teach-back?

(Schenker et al, 2011; Greening et al, 1999; Wadley & Frank, 1997; White at al, 1995, Paasche-Orlow, 2011)

“Ask each patient or legal surrogate to “teach back” in his or her own words key information about the proposed treatments or procedures for which he or she is being asked to provide informed consent.”

|

Why use teach-back?

|

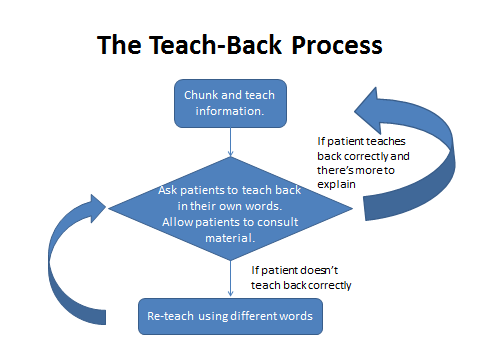

Slide 23: The Teach-Back Process |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Section 2. Strategies for Clear Communication

Strategy 4: Use Teach-Back

|

Don’t wait until the end of the informed consent discussion to initiate Teach-Back. Employ the “Chunk and Check” process by which you ask your patient to teach back each chunk of information as you go along.

It is very important that patients teach-back in their own words. If they simply parrot the exact words you said, you don’t know if they actually understood the meaning.

Teach-back is not a memory test. Patients can look over the Informed Consent form or other materials you’ve shared with them as they teach-back. But watch out for verbatim quotes that do not reveal whether your patient understands or not.

If your patient is unable to teach back correctly, explain again in a different way. Repeating the exact same thing probably won’t increase your patient’s understanding. Try a new approach using different words, and then ask your patient to teach-back again in his or her own words.

You need to repeat the teach-back process until your patient can correctly teach the information back. If your patient can’t demonstrate understanding, then he or she may be unable to give informed consent.

When the patient has correctly taught back everything you wanted to make sure they understood, be sure to document your use of the teach-back and the patient’s response in the medical record. |

Slide 24:Tips on conducting teach-back effectively |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

Section 2. Strategies for Clear Communication Strategy 4: Use Teach-Back

Tips on conducting teach-back effectively

Adapted from: Always Use Teach-Back Toolkit http://www.teachbacktraining.org/

|

Tips on conducting teach-back effectively

These tips come from the “Always Use Teach-Back toolkit “:

|

Slide 25: Teach-back phrases |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

JAMIE: Please explore options for making this slide interactive

|

Section 2. Strategies for Clear Communication Strategy 4: Use Teach-Back

Teach-back Questions

|

It’s hard to do teach-back without it feeling like you’re testing your patient. It’ll take practice, but clinicians have said that once they got the hang of teach-back, they could seamlessly weave it into the informed consent discussion.

Here are some phrases that can get you started.

|

Slide 26: Frequent questions about teach-back |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Please explore options for making this slide interactive

We have added the contents of this slide to the resources section.

Add to resources:

Fink, A. S., A. V. Prochazka, W. G. Henderson, D. Bartenfeld, C. Nyirenda, A. Webb, D. H. Berger, K. Itani, T. Whitehill, J. Edwards, M. Wilson, C. Karsonovich, and P. Parmelee. 2010. Predictors of comprehension during surgical informed consent. Journal of American College of Surgeons 210:919-926.

Schillinger, D., Piette, J., Grumbach, K., Wang, F., Wilson, C., Daher, C., Bindman, A. B. (2003). Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy Arch Intern Med, 163(1), 83-90.

|

Section 2. Strategies for Clear Communication Strategy 4: Use Teach-Back

Frequently asked questions about teach-back:

A: All patients making medical decisions are at risk of misunderstanding and can benefit from teach-back. Over a third of the U.S. population has limited health literacy. Even people with proficient health literacy are at risk of misunderstanding when they are sick, stressed, or scared.

A: A randomized controlled trial on elective surgery showed that teach-back improved patient understanding and took an average of 4 minutes (Fink et al 2010). Another study suggested that patient visits with teach-back took no longer than without teach-back (Schillinger et al 2003). In addition, teach-back can save time and money by reducing cancelled or delayed surgeries.

A: Patients may feel insulted if you make the teach-back seem like a test. To minimize that risk you can use the phrase, “just to make sure I explained it well…” before asking your teach-back questions, so that the patient understands it is not a test of their abilities.

A: Teach-back is useful whenever it’s important to confirm patients’ understanding. You have not obtained informed consent if you are not sure your patient has understood the information presented and the available choices.

|

Here are some frequently asked questions about teach-back:

A: All patients making medical decisions are at risk of misunderstanding and can benefit from teach-back. Over a third of the U.S. population has limited health literacy. Even people with proficient health literacy are at risk of misunderstanding when they are sick, stressed, or scared.

A: A randomized controlled trial on elective surgery by Fink and colleagues showed that teach-back improved patient understanding and took an average of 4 minutes, and another study by Schillinger and colleagues suggested that patient visits with teach-back took no longer than those without teach-back. In addition, teach-back can save time and money by reducing cancelled or delayed surgeries.

A: Patients may feel insulted if you make the teach-back seem like a test. Let your patient know that you’re checking how clear you were by using such phrases such as, “just to make sure I explained it well…” before asking your teach-back questions, so that the patient understands it’s not a test of their abilities.

A: Teach-back is useful whenever it’s important to make sure patients understand. You have not obtained informed consent if you are not sure your patient has understood the information presented and the available choices. |

Slide 27: Section 3. Strategies for Presenting Choices |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Add to resources the SHARE Tools. They will be published at: http:// ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/index.html |

Section 3. Strategies for Presenting Choices

Strategy 5: Offer Choices Strategy 6: Engage the Patient and Their Family and Friends Strategy 7: Elicit Goals and Values Strategy 8: Encourage Questions Strategy 9: Show High Quality Decision Aids Strategy 10: Explain Benefits, Harms, and Risks of All Options

|

In this third section of the course we describe six strategies for presenting choices. Since we already described four strategies in Section 2, we’ll keep track of these by numbering them from 5 to 10.

Strategy 5 is simply to offer choices. Patients always have a choice among alternatives, even if that choice is to do nothing.

Strategy 6 is to engage patients and their families and friends by putting them at ease and enhancing their confidence to participate in the informed consent discussion.

Strategy 7 is to ask patients about their goals and values so you can help them understand how well different options might work for them.

Strategy 8 is to encourage the patient to ask questions.

Strategy 9 is to select and show high-quality decision aids to help your patients to process information about their choices.

Strategy 10 is to explain the benefits, harms, and risks of all options – not just the option you recommend. |

Slide 28: Strategy 5 Offer Choices |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

When talking about angioplasty, maybe have the treatment options appear with lots of question marks |

Section 3. Strategies for Presenting Choices Strategy 5: Offer Choices

“There is good information about how these treatments differ that I’d like to discuss with you.”

[Pictures of Robert and Marie linked to audio clips.] |

Strategy 5 is to present all the options available. There are always choices, even if the only alternative is simply to do nothing.

It can be very difficult to offer options when you have a strong opinion on what the best choice is. It may help to keep in mind that what we think is the best treatment is often colored by what those around us are doing. For example, in your community most doctors may treat stable angina with angioplasty, while in another community bypass surgery is the most common treatment, and medical management is the most frequent treatment in yet another community. The fact that practice patterns differ around the country shows that it isn’t patients’ clinical circumstances, or their preferences, that’s driving much of medical decision making.

Ultimately it should be the patient’s decision, which will depend on such things as how much pain they are in, how much activity limitation they have, what they’re willing to put up with, how risk adverse they are, and what their short-term and long-term plans are. What seems best to you may not be the best choice for your patient based on their goals and values.

You may need to dispel the idea that you’re putting out options because you lack expertise and don’t know what to do. You might try saying, “There is good information about the differences between these treatments that I’d like to discuss with you.”

Click on the pictures of Robert and Marie to hear Dr Smith share two patient cases that illustrate the importance of important presenting choices.

Don’t limit the options to those that are covered by the patient’s insurance. What you and your patient consider affordable may differ.

Robert is an 88-year old man with advanced prostate cancer. He was responding well to hormone treatment, but his prostate became so large that he developed a blockage. We had to insert a catheter. I increased his dose of doxazosin in the hopes of shrinking his prostate, but after several weeks Robert is still unable to urinate. In the informed consent discussion, I told Robert and his family about two choices: have surgery to remove part of his prostate or live with a catheter. I thought the surgery would be the best choice, but I knew that Robert was afraid of anesthesia and of getting an infection while at the hospital. We talked through the benefits, harms, and risks of both options. Robert was pleasantly surprised that the surgery is usually done without general anesthetic and was less happy about the prospect of living with a catheter when he learned it would likely restrict his ping-pong playing. To my surprise, he chose to have the surgery. I think that if I had not gained his trust by being a neutral source of information, Robert might not have been willing to undergo the surgery.

Marie is a 32-year old who reported having heard a “popping” sound and having severe knee pain. An MRI revealed a medium-sized, bucket handle tear of her meniscus in the red zone. After looking at her test results and condition, I presented 3 options to Marie. She could try home management and physical therapy, she could have meniscus repaired, or she could have the torn part of her meniscus removed.

I then asked her to watch a decision aid that describes the options and to schedule another visit to discuss them further.

When Marie returned, I explained that her prognosis for a repair is good, since the tear is not too large and is in an area that has good blood flow to promote healing. I also told her my estimates for recovery times, and checked that she understood the benefits, harms and risks of the options, including the increased risk of future arthritis with a partial removal of the meniscus.

Marie was in so much pain that she didn’t think she could manage without surgery. Her chief concern was to get back to work quickly, and she was worried about the long period of time she would be rehabilitating her knee after a repair. Despite knowing that she’d be more likely to develop arthritis in that knee than if she had the repair, she decided to have the partial removal of her meniscus. It wouldn’t have been my choice, but she has different priorities. |

Slide 29: Strategy 6: Engage patients, families and friends |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

JAMIE: Explore other presentation rather than bullet points. |

Section 3. Strategies for Presenting Choices

Strategy 6: Engage the Patient and Their Family and Friends

Patients involved in decision making are more satisfied with their care.

Many patients and their families and friends lack confidence.

Your job:

|

Research shows that patients who are involved in decision making are more satisfied with their care. But many patients lack confidence that they can make important decisions about their health. That’s why our sixth strategy is engaging patients, families, and friends.

There are several reasons patients may feel at a disadvantage.

First, they don’t have the expert knowledge the clinician has. They may be vulnerable due to the physical and emotional effects of their illness including possible impairment, disability, fatigue, pain, mental stress etc. They may also be used to clinicians who tell them what to do rather than ask them to join in the decision making. Or they may come from a culture where it’s customary to defer to doctors and asking a question would be considered rude.

Many people may be involved in informing the patient, but if you're the clinician who's in charge of ordering a test or treatment or performing a procedure, there are some things you have to do yourself.

Your job is to put your patients at ease and show that you respect their values and opinions. You’ll need to draw them into the informed consent discussion and enable them to be an active participant in the decision they are facing. You can start by acknowledging their expertise. Patients have unique knowledge about their lives, emotions, culture, social supports, experiences, wants, goals, and more. Listen to them carefully and you’ll learn a lot. You can let them know that you are listening by asking follow-up questions. That way you can find out what specific information they need further clarity on before they can make a decision. For example, you could say: “I hear you’re worried about not being able to walk much this summer. Let’s talk a bit more about what to expect.” |

Slide 30: Put patients, families and friends at ease and show respect |

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

JAMIE: We are searching for replacement or some other suitable visual for this screen. We need a replacement video here if we choose to use video.

Let’s think about whether to remove the first 10 seconds of the embedded video or not. In those 10 seconds, the doctor makes it safe for the interpreter to ask questions and provide any information she may have missed. After that, the interpreter creates the same safety for the patient. I have the original clip if you want to edit it.

(Video link:http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/teamstepps/lep/videos/psychsafety/index.html) |

Section 3. Strategies for Presenting Choices

Strategy 6: Engage the Patient and Their Family and Friends

Put patients, families and friends at ease and show respect

|

Put patients, families and friends at ease and show respect

Start off by encouraging the patient to have a trusted family member or friend with them during the informed consent discussion to support them as they get information and make decisions. A patient who is stressed about their condition is more likely to misunderstand information given. A support person can lower the stress, help the patient to process the information, and ask questions.

There are other things you can do to put patients and their family and friends at ease. To show them that they are important and respected:

You can also create an environment of psychological safety by encouraging questions and signaling your openness. Psychological safety means that patients are not afraid to share what they think, wonder and feel, because they feel accepted and respected.

Here is a short video showing you an example of how you can create psychological safety. In this video, an interpreter is creating psychological safety for the patient on behalf of the medical team. When an interpreter is not needed, the clinician can directly communicate with the patient to create psychological safety.

|

Slide 31: Draw patients into discussion with conversational prompts |

|

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

JAMIE: Explore interactive options for this slide.

Include these resources in the “resources” section:

Tools to facilitate shared decision-making conversations:

Website of the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation: http://www.informedmedicaldecisions.org/

|

Section 3. Strategies for Presenting Choices

Strategy 6: Engage the Patient and Their Family and Friends

Draw patients into discussion with conversational prompts

Use open-ended questions.

Verbally acknowledge the patient as his or her own expert.

Ask specific questions related to the patient’s role in their care and treatment.

|

Many patients and their family and friends will need your encouragement to become active participants in the informed consent discussion. To draw them into the conversation, try starting with their areas of expertise – their experience with their health problem. You may need to help them get started. It helps to use open-ended questions that can’t be answered with yes or no. Here are some questions that can help get them talking.

Be sure to address the patient’s specific concerns. This will also indicate that you are listening and will encourage them to share further.

Always acknowledge that the patient is an expert about him or herself and encourage them to ask and share information about their treatment expectations, concerns, and understanding of their condition. For example, you might say,

One way to acknowledge the patient as an expert about him or herself is to ask specific questions related to the patient’s role in their care and treatment. You might, for example, ask them:

Additional resources are available in the “resources” section of this course to help draw your patients into informed consent discussions. These resources include worksheets to help patients think through their options, and the website of the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation.

|

|

Slide 32: Strategy 7: Elicit goals and values |

|

||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

|

When reading the last paragraph, show a patient and doctor. The patient’s conversation bubble says, “What would you do?” The doctor’s bubble says, “The question is, what’s important to you?” |

Section 3. Strategies for Presenting Choices Strategy 7: Elicit Goals and Values

Patients don’t all want the same thing.

Find out what your patient’s goals and values are.

|

Patients don’t all want the same thing. Treatments have different consequences, and some will matter more to one patient than another. Using Strategy 7, you’ll help your patient figure out what’s important to him or her.

To get at your patients’ treatment goals and values, you might try asking “What matters to you most?” You may need to probe a bit further, by asking about specific outcomes such as minimizing pain, getting back to work or school quickly, and being able to participate in a favorite activity. Some goals may be longer term, like reducing risk of future injury or illness or living as long as possible. Treatment choices may be influenced by concerns about the treatments themselves. Again, you may have to probe to find out what’s really on your patients’ minds. Is it side effects? Or are they worried about being dependent on others, or on medicines? Or about possible complications? Or perhaps they’re concerned about whether the treatment is likely to be successful. Patients may ask you “What would you do?” Remember that what a person chooses depends on their goals and values, and your patient’s goals and values may be different from yours. It’s tempting to jump in with your recommendation, but try to help your patients to think about what’s important to them.

|

|

Slide 33: Strategy 8: Encourage questions |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Jamie: Explore making this interactive.

List as a reference: AHRQ’s Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit Tool 14: Encourage Questions |

Section 3. Strategies for Presenting Choices Strategy 8: Encourage Questions

Reasons for unasked questions

Strategies to encourage questions

SAY: "I know I'm giving you a lot of information. Many people find this confusing. Let me pause here so you can tell me what questions you have."

DON’T SAY: “Do you have any questions?

Norma Kenoyer, Iowa New Readers

|

Patients often have unanswered questions about their choices. They may be ashamed to ask questions, fearing they will seem foolish. Or they might just be shy by nature. So you’ll need to encourage them to ask questions, which is our eighth strategy.

They may think that you don’t have enough time to answer their questions. Or, they may not be able to process the information quickly enough to be able to come up with questions.

Patients may simply be overwhelmed with the amount and flow of information. Or they may have forgotten their questions by the time you’ve finished presenting information on all the choices.

Here are some suggestions for how you can encourage your patients to get the information they need to make informed decisions.

Click on Norma Kenoyer, a member of Iowa New Readers, to hear how patients pick up on the cues you send. Audio clip: My doctor just seemed like he was in a hurry. I read his body language. He’d ask if I had any questions, and I said no and he’d walk out the door. I could have asked him this and that, but he couldn’t even give me a chance. It was, “Any questions?” and out the door he went before I could even think. |

Slide 34: Strategy 9 for Presenting Choices: Show High-Quality Decision Aids |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

JAMIE: Use visual to present this slide

Could use an edited down version of this video to illustrate decision aids are complements, not substitutes, of the IC discussion

Note: video is 4 min 14 seconds and will have to be edited. We will request copyright authorization from the informed medical decisions foundation.

For the resources section, offer this resource to learn more about the standards for high-quality decision aids: Volk RJ, Llewelyn-Thomas H, Stacey D, Elwyn G (2013). Ten years of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration: evolution of the core dimensions for assessing the quality of patient decision aids.

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6947/13/S2/S1 what constitutes a high-quality decision aid: |

Section 3. Strategies for Presenting Choice

Strategy 9: Show High-Quality Decision Aids

Decision aids unbiased information. They can be:

Decision aids are NOT a substitute for the informed consent discussion, even if offered as part of a high-quality computerized informed consent system.

[EMBED VIDEO HERE.]

Decision aids provide information about:

Using decision aids:

[Reference: Kinnersley et al 2013; Legare et al. 2014.]

|

Strategy 9: Show high-quality decision aids

A decision aid presents the various options in an unbiased way to patients so that they can make an informed choice.

Decision aids can be paper-based, audio-visual, multimedia, web-based, or interactive. Some decision aids are meant for patients to use on their own, while other decision aids are to be used jointly, with someone helping the patient process the information and highlight important points. Decision aids are designed to complement, rather than replace, the informed consent discussion, even if they’re offered as part of a high-quality computerized informed consent system. For example, after a patient has viewed a decision aid, the clinician can use teach-back to make sure the patient understood the information, personalize the information for that patient, encourage and answer questions, and discuss the information in the context of the patient’s goals and values.

Decision aids provide information about:

Clinicians often find that using decision aids helps them structure conversations about choices with patients. Research suggests using decision aids improves patients’ knowledge of the options available to them. Patients who use decision aids have more accurate expectations of possible benefits, harms, and risks of their options. Most importantly, decision aids help patients clarify what matters most to them, makes them more likely to participate in the decision-making process and communicate effectively with their providers, and makes them more likely to reach decisions consistent with their goals and values. And finally, patients whose decisions are fully informed through the use of decision aids are better able to cope with treatment outcomes and adverse events.

|

Slide 35: Finding High-Quality Decision Aids |

|

|

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

Add to resources: Option Grids: http://www.optiongrid.co.uk/

|

Section 3. Strategies for Presenting Choice

Strategy 9: Show High-Quality Decision Aids

Finding high quality decision aids

Consideration when choosing decision aids

|

Where can you find high-quality decision aids?

When using a decision aid, consider how your patient best learns. Is your patient one who likes to read information, or would they rather see and listen to it? If a multimedia resource is being recommended, make sure your patient has the right equipment to view it. And if the decision aid is available on a Web site, make sure your patient is comfortable using the Internet. You may need to make arrangements to show the decision aid to your patient in your office, and offer adaptive software for people with low vision or other disabilities. |

Slide 36: Strategy 4 for Presenting Choices: Explain benefits, harms, and risks of all options |

||||

Content to the designer |

On-Screen Content |

Audio Guidance |

||

Consider flashing the graphic on-screen when the audio says “and show a visual representation like this one “.

For the resources section, include this link for an example of a “paling palette” chart: http://www.riskcomm.com/images/Palette1Downs.pdf

Also include this link to create your own paling palette: http://www.riskcomm.com/introvisualaids.php?p=5

Also include this reference about the story of the Navajo cancer patient: [Reference: Carrese JA, Rhodes LA. Bridging cultural differences in medical practice. The case of discussing negative information with Navajo patients. J Gen Intern Med. Feb 2000;15(2):92-96.] |

Section 3. Strategies for Presenting Choices Strategy 10: Explain Benefits, Harms and Risks of All Options

|