Planning for the Mode of Administration

Planning for the Mode of Administration for the Youth Outcome Survey-FINAL.doc

National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD) and Youth Outcomes Survey - Final Rule

Planning for the Mode of Administration

OMB: 0970-0340

![]() Planning

for the Mode of Youth Outcome Survey Administration

Planning

for the Mode of Youth Outcome Survey Administration

Technical

Assistance Document

Issued:

May 2010

In this

document:

We

discuss the pros and cons of different modes of administering the

NYTD Youth Outcome Survey. Target

audience:

Data

managers, information technology managers, and independent living

coordinators from States that are still considering how best to

administer the NYTD youth outcome survey Key

words:

Youth outcome survey, nonresponse bias, survey mode

Planning for the Mode of Administration for the Youth Outcome Survey

While the NYTD regulation specifies the survey questions States must pose to youth in the baseline and follow-up populations, States are not required to follow a specific method of survey administration. This flexibility allows States to choose the administration method that they feel will collect the highest quality data given available resources, technology, implementation timelines, and characteristics of the youth population. The choice of survey methodology—or methodologies—is important to collecting high quality data that represent the collective experiences of youth both in and out of foster care. An appropriate administration method maximizes participation in the survey by all eligible youth and is vitally important to avoiding nonresponse bias1, as we previously discussed in the technical assistance document Practical Strategies for Planning and Conducting the NYTD Youth Outcome Survey (available at http://www.nrccwdt.org/resources/nytd/nytd.html).

States vary in the size of their foster care population and their experience using web-based technologies. Youth, meanwhile, vary in their interests, capabilities, and resources. Consequently, it is likely that using a few different approaches to collecting youth outcome data will be necessary to meet the needs of all youth required to be surveyed. We acknowledge that some States have already developed detailed data collection plans for the youth outcome survey and that some others have decided to contract out their data collection to universities or professional survey firms. This technical assistance document is not intended to replace these plans but to provide guidance to States that are still considering the best approach for collecting outcomes data from youth.

There are pros and cons to any survey administration method and the NYTD youth outcome survey is no exception. It is important to note that with any method of administration, some youth will require multiple follow-up contacts before they can be successfully invited to participate in the youth outcome survey. It is critical that a plan for repeated follow-up be developed before the survey is implemented. States need not be wedded to one approach to administer the baseline and follow-up surveys but may find

that different modes are more appropriate at different times. Below we discuss some of the pros and cons of various survey administration methods States may want to consider for the survey. The pros and cons are summarized in Table 1.

Regardless of mode, States will want to follow these Survey Dos:

Do involve youth in the design of your youth outcome survey instrument

Do make sure the survey questions are presented to youth as they appear in the regulation

Do market the youth outcome survey to youth in your foster care system

Do discuss NYTD as part of the youth’s transition plan

Do train staff on your survey administration method(s) of choice

Do estimate the number of 17-year-old youth who need to be surveyed

Do have a stated deadline for completion of the survey

Do plan on multiple follow-up contacts with youth to obtain a high survey response rate

Do let youth know what your plan is for administering the follow-up surveys at ages 19 and 21 at the time of the baseline survey.

Do collect contact information at the time of the baseline survey and at exit from care to help you reach youth at the time of the follow-up surveys

Do have a plan for updating contact information between survey rounds

Do keep in touch with youth between survey rounds

Do have a plan to collect outcomes data from youth with special needs

Do let youth know that their participation is essential to improving services that help youth transition successfully to independence

Web Surveys

Today’s youth have grown up with computers in school and at home so most are experienced and comfortable with this technology (Lenhart et al., 2005, Lenhart et al., 2007). Because of the popularity of electronic social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter and MySpace, many youth without computers at home seek out access to computers from libraries or other free public sites to keep connected with their friends (Lenhart et al., 2007). Not surprisingly, youth tend to find completing surveys online more interesting and fun than completing paper surveys (McCabe, 2004). Surveys conducted on the web have become increasingly popular as a low-cost method of survey administration. While there are up-front costs associated with programming a survey instrument for web-based administration, once the instrument is programmed, web surveys can reach a large audience at little cost for each additional respondent (Chang and Krosnick, 2009). Another advantage of web surveys is that the survey can be distributed easily via emails, website postings or hyperlinks. States may also have youth complete a computer-based survey in the agency office when the youth goes for a caseworker visit or receives independent living services.

Web surveys also have the advantage of being self-administered. Self-administered surveys have long been demonstrated to lead to more honest answers to questions about sensitive or illegal behaviors, such as sexual behaviors or substance use (Chang and Krosnick, 2009; Tourangeau and Smith, 1996; Wright et al., 1998). Data quality is further enhanced on web surveys by computer programs that do not allow required questions to be inadvertently skipped or that do not allow out-of-range responses to be provided. For example, if a youth answers “yes” to the survey question that corresponds to data element 52 (“Have you ever given birth or fathered any children that were born?”), the youth does not have the option of skipping the question that corresponds to data element 53 (“If you responded yes to the previous question, were you married to the child’s other parent at the time each child was born?”) because the computer requires an answer of “yes,” “no,” or “declined” for data element 52 before the youth can go on. Computerized interviews also help avoid data errors that may occur when respondents give internally inconsistent answers—such as answering “no” to the survey question that corresponds to data element 52 but then answering “yes” to the question that corresponds to data element 53. Because the youth enter their own data, time and money are also saved by avoiding questionnaire printing, data entry and data cleaning. Youth can also complete a web survey from any location (including another State) and at a time that is convenient for them.

Online surveys have their disadvantages as well. In addition to the upfront cost of programming the web survey, there are the costs of developing data security measures (such as user names and passwords) to ensure that only the target youth has access to the survey. It can also be difficult to verify that the target youth is the one who has completed the survey, rather than a sibling or housemate (however, there is little incentive for someone other than the target youth to complete the survey). Technological challenges can also be an issue with web surveys. Depending on the computer settings (such as the browser used, the script the browser can read, the screen resolution, security settings), the web survey may look somewhat different on one computer versus another (Couper, 2008).

Web surveys also pose difficulties for respondents with low literacy or with special needs that may need more explanation of what the questions mean in order to give an accurate response. Some respondents will simply be unable to complete a web survey because they lack access to a computer or because the web survey technology does not support the youth’s needs (e.g., the web survey is not compatible with a screen reader for a youth with a vision impairment) and will require an interviewer to administer the survey. States are encouraged to anticipate and address the special needs of particular youth populations when devising survey administration protocols for NYTD. Further technical assistance on administering the youth outcome survey to special populations such as youth with disabilities and youth who speak a language other than English will be provided in a future technical assistance document.

Interviewer-Administered Surveys

Interviewer-administered survey methods include both in-person and telephone-based administration. The biggest advantage of interviewer-administered methods is that the interviewer reads the questions to the respondent, thereby avoiding any concerns about literacy. With interviewer-administered modes interviewers are able to follow up on respondent questions with probes and can resolve inconsistencies (Chang and Krosnick, 2009). In-person interviewing has the advantage of face-to-face rapport building and typically has the highest response rate when the interviewer visits the respondent’s home. Telephone interviewing can also be an effective method of obtaining a high response rate, provided the youth has a working telephone number and is willing to share it.

Major disadvantages of interviewer-administered methods are the cost of training and administration, the possible introduction of interviewer and data entry errors, less candid answers to sensitive questions, and possible higher refusal rates for those youth with strained agency relationships. Without consistent training on survey administration, interviewers—both telephone-based and in-person—can introduce errors and biases when collecting data (Kiecker and Nelson, 1996). Having a caseworker administer a survey involves not only the time of the youth, but the time of the worker as well. If the survey is administered on paper, additional time must be factored in for data entry and data cleaning. And unless data-enterers are well trained (or double entry is used), errors can also be introduced during the data entry phase. As discussed above, respondents also tend to be less willing to give honest answers to sensitive questions when their answers are being recorded by an interviewer rather than when the survey is self-administered. Finally, youth who did not have a good relationship with their caseworker while in care may not welcome contact with the caseworker or agency after they leave care and thus may be less likely to agree to complete the follow-up surveys.

There are populations of youth for whom an interviewer-administered approach may be the only option. These populations include youth with very low literacy, youth who are visually impaired, youth who do not speak English, and youth who have other special needs that prevent them from completing a web survey or a paper form by themselves. To the extent possible, accommodations should be made to allow youth with special needs to complete the survey in a manner as similar as possible to other youth. For example, youth with low literacy may be able to complete their own paper copy as they follow along with interviewer while she/he reads the questions and response options aloud to the youth.

Self-Administered Paper Surveys

Self-Administered Paper Surveys with Interviewer Assistance

States that do not have the time and resources to program a web survey for the baseline instrument may want to consider an alternative self-administration mode: a paper survey that is delivered by the caseworker or other interviewer and completed by the youth in the interviewer’s presence. This method has the advantages of both self-administration and the personal attention of an in-person visit. The interviewer could also be available to answer questions the youth has about the survey, though training of the interviewer is encouraged in order to prevent the introduction of bias or error from incorrect or inconsistent explanations of the survey question. This method is likely to require additional time and costs when the youth is out of care and no longer receiving regular visits from his/her caseworker.

Surveys Administered by Mail

Mail surveys are often viewed as a low cost method of survey administration. While it is true that such surveys are typically inexpensive to mail out, they often suffer from low response rates. Use of the Dillman Total Design method (which involves multiple, sequenced mailings of questionnaires and reminders) has been demonstrated to bolster response rates significantly, though this method can be time-consuming and can increase costs considerably (Dillman et al., 2009c). Because the NYTD baseline population data collection requirement specifies that States must collect survey information from youth in foster care within 45 days of a 17th birthday (45 CFR 1356.82(a)(2)(i)), this may not be an adequate time frame in which to administer a survey by mail to a youth in the baseline population.

The quality of data from mail surveys may also be uneven as there is a risk that, despite clearly written instructions to the youth, the respondent may still inadvertently skip certain questions (or entire pages of the survey), select multiple answers to a single question or provide internally inconsistent responses to specific survey questions. For example, with a paper survey a youth may answer “no” to both survey questions related to data elements 52 and 53 when a “no” response to data element 52 (children) should mean that the question corresponding to data element 53 (marriage at child’s birth) is “not applicable.” Youth with low literacy and other special needs that preclude self-administration may also be unable to participate in mail surveys. Errors can also be introduced during the data entry phase when surveys are collected and entered into an information system. The person responsible for data entry, for example, may mistakenly key in the wrong value or may be unable to decipher illegible handwriting.

Table 1 summarizes the pros and cons of different methods of administering the NYTD youth outcome survey.

Table 1: Pros and Cons of Different Methods of Survey Administration

Mode |

Pros |

Cons |

Web Survey

Web Survey (continued) |

electronic social networking, many youth are motivated to have some access to computers (such as libraries or other free sites)

|

|

Interviewer-Administered Surveys

|

|

|

Self-Administered Paper Survey with Interviewer Assistance |

|

|

Self-Administered Survey by Mail |

|

|

Other Issues to Consider When Selecting and Implementing a Survey Mode

In order to comply with NYTD requirements, States must collect outcomes information from youth in the baseline population within 45 days following the youth’s 17th birthday (45 CFR 1356.82(a)(2)(i)). For youth in the follow-up population, States must collect outcomes information during the 6-month reporting period in which these youth turn age 19 or 21 (45 CFR 1356.82(a)(3)). Therefore, States will want to consider a data collection plan that 1) clearly lays out the expectations for completing the survey within the prescribed timeframes of NYTD outcome data collection and 2) appropriately builds in time for repeated follow-up activities to engage as many eligible youth as possible to participate in the survey.

Prenotification

It is important to have a deadline for survey completion that is clearly communicated to respondents to encourage them to participate in a timely manner. Use of mailed (or hand- delivered) advance letters is recommended to lay out clear expectations and timelines for survey completion, regardless of mode. Several studies have found that prenotification letters sent by mail garner a higher response rate for web surveys than prenotification sent solely by email (Couper, 2008). In addition, States may want to consider using social networking sites to publicize the survey and remind youth to complete it.

Incentives

Regardless of survey mode, States are encouraged to consider providing incentives to youth for participating in the survey. North Carolina conducted a survey of youth in foster care to see what factors the youth believed would make the biggest difference in the decision to participate in the NYTD survey. Financial incentives were at the top of the list. A separate technical assistance document will be issued on the use of incentives and other ways to maximize response rates for the baseline and follow-up surveys.

Using the Same Survey Mode for the Baseline and Follow-Up Surveys

We encourage States to consider using the same primary survey mode at baseline and at the two follow-up surveys so that youth become comfortable with the survey methodology through their baseline survey experience and know what to expect for the follow-up surveys. For example, if a web survey is being used, youth may be directed to complete the baseline survey on their home or library computer, at the caseworker’s office or on the caseworker’s laptop during a home visit. When it comes time to complete the follow-up survey at age 19, youth will then be familiar with the format and usability of the web survey, making the survey easier to complete a second time. Youth could then be directed to locations where they can complete the follow-up survey online if they do not have personal web access.

Using the same primary survey mode across the three rounds of the survey also minimizes difference in youth response that can occur from using different modes. The reliability of a question is enhanced when it is administered in the same mode across time. For example, a youth may feel uncomfortable disclosing to a person that he has had a substance abuse referral (survey question for data element 50) but may give a more honest answer on a self-administered survey. If an interviewer-administered mode is used at baseline but self-administration is used at follow-up, youth may appear to have more problems at the time the follow-up survey is administered rather than at the baseline survey when this change may really be the result of a change in mode. We do note that survey mode differences are most pronounced for sensitive questions (which number only a few among the NYTD youth outcome survey items), and not all surveys have found mode effects of interviewer and self-administered surveys when looking at the reporting of sensitive behaviors (McMorris et al., 2008).

Following Up with Non-Respondent Youth

Regardless of the survey mode selected, States are encouraged to develop plans for following up with non-respondents. Follow-up for non-respondents may take several different forms, including emailed or mailed reminders, text messages and telephone calls. In order to obtain a high survey response rate, it may be necessary to use an alternate method of data collection for some respondents. We do not recommend offering respondents an initial choice of survey mode as survey research has found that giving respondents choice can result in lower overall response rates (Dillman et al., 2009b; Gentry and Hood, 2008). However, using a sequential approach to offering different survey modes has been demonstrated to be effective at increasing overall response (Dillman et al., 2009a; McMorris et al., 2008). With the sequential approach, an alternate mode is provided for those who fail to respond to the initial mode. It is advantageous to start with the lower cost mode (such as a web survey) and then provide an alternate method of administration (such as interviewer-administered telephone survey) for those who have not responded.

For example, within a few days of a 17th birthday, a State informs all 17-year old youth in the NYTD baseline population by mail, email, telephone and text messaging that the youth outcome survey is available for completion on the web. The youth are given a date for when the survey needs to be completed (such as within 3 weeks) and sent weekly reminders to complete it. Youth who do not complete the web survey within 21 days are then called by a caseworker trained to administer the survey who collects the survey data over the telephone.

Selecting a Survey Mode That Works for Your State

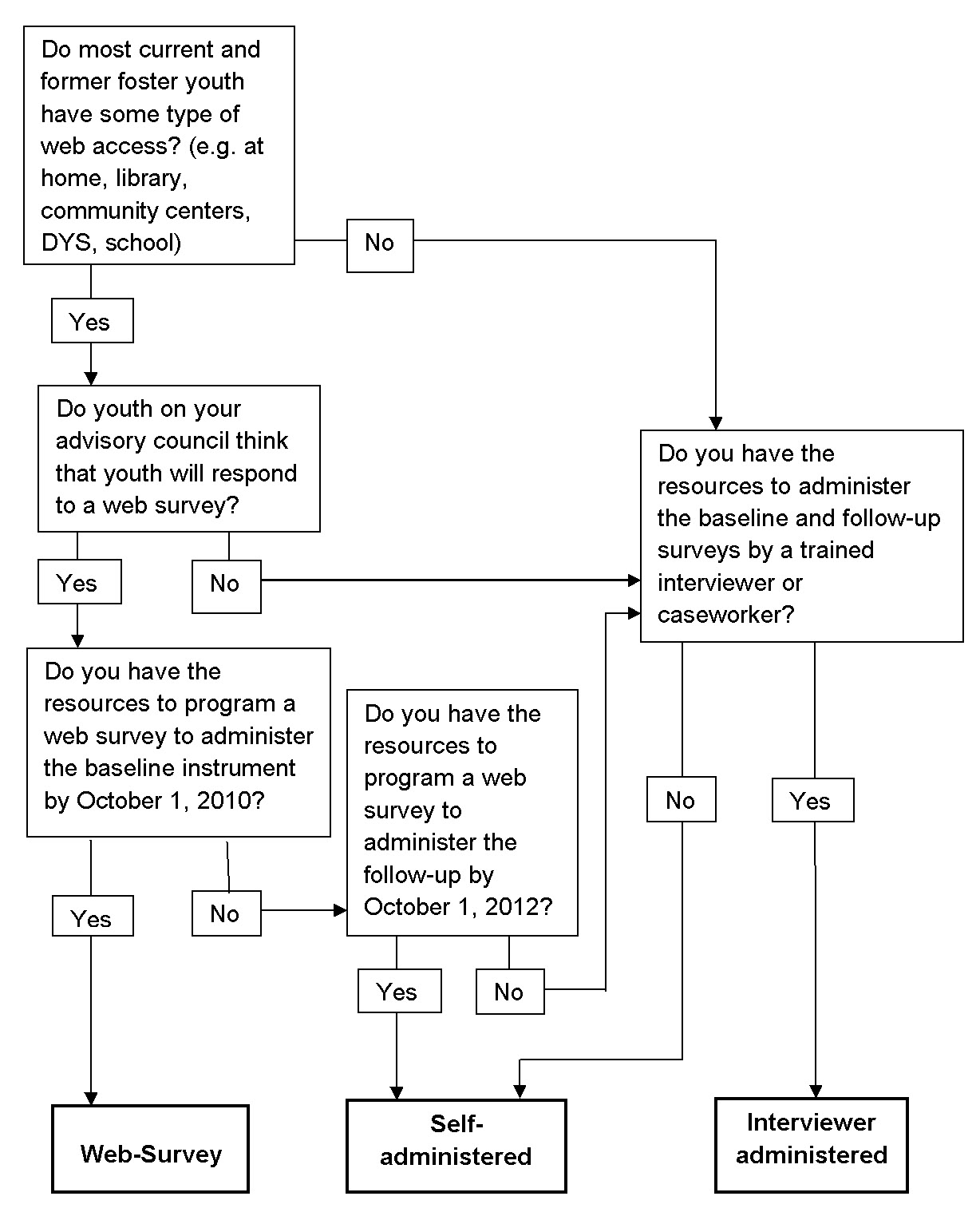

Below we offer some suggested steps a State may consider for implementing various modes of administering the NYTD youth outcome survey. Figure 1 presents a decision tree that may be used to help guide a State in selecting a primary survey administration mode.

Figure 1: Decision Tree for Survey Administration

States will want to document decision points about survey administration and what information the decision was based on. As it will be 5 years before the first cohort of youth completes the final NTYD follow-up survey, a log of decisions made and the consequences of those decisions will be important for States to use to monitor their progress and change course, as necessary.

Implementing a Web Survey

If your State has decided to conduct the NYTD youth outcome survey over the web, these are some suggested steps that the State could take:

Decide on wording for any additional explanations needed for the survey questions. While all States must ask the questions as worded in Appendix B of the NYTD regulation, some questions will be more easily understood by youth with additional explanation. The definitions provided in the regulation offer some additional guidance but you may determine that other youth-friendly explanations are more useful. It is recommended such explanations be plainly visible in the instrument (rather than utilizing a pop-up explanation screen when the cursor moves over a question) to ensure that all youth in your State understand the question in the same way

Design your data security system

Program the survey

Test the web survey with a sample of current foster youth to make sure that it is easily used

Design and program your management system to keep track of when youth need to complete the survey and who has completed the survey

Design a protocol for notifying youth about the web survey

Design a protocol for administering the survey to youth who cannot complete it as a web survey

Implementing an Interviewer-Administered Survey

States may decide to use caseworkers or other agency staff to administer the survey at baseline survey administration only, or for the administration of both the baseline and follow-up surveys. At the time of the baseline survey, youth will still be receiving regular visits from his/her caseworker, making interviewer-administration a more economical option.

States will want to follow these steps in planning for an interviewer-administrated instrument:

Train workers on how to administer the survey consistently, including how to use prompts or to offer further explanations about the meaning of the youth outcome survey questions and response options

Pretest interviewer-administration for clarity with a sample of youth in foster care

Print copies of the questionnaire

Set up a system for entry of the data and verification that the data entry was correct

Implementing a Self-Administered Paper Survey

States that want to administer the follow-up survey as a web survey but feel that they do not have the time and resources to program the baseline survey in time for administration by October 1, 2010 may want to have youth complete the baseline survey as a self-administered paper survey. Under this scenario, the youth’s caseworker would deliver a paper copy of the survey to youth during the regularly scheduled monthly visit. The youth would then complete the survey in the worker’s presence. The worker would then bring the survey back to the State agency for data entry. We do not recommend mailing the survey as mail surveys typically have a low rate of return.

States will want to follow these steps if they have decided on a self-administered paper survey:

Format the questionnaire in an easy-to-read manner, included explanatory text as necessary

Pretest the paper questionnaire for clarity with a sample of youth in care

Design the protocol for how the questionnaire will be distributed to youth and how it will be returned to the State agency

Train workers in how to administer the survey consistently, including how to use prompts or to offer further explanation about the meaning of the youth outcome survey questions and responses options

Have caseworkers review completed questionnaires for any skipped items prior to leaving the youth’s home

Set up a system for entry of the data and verification that the data entry was correct.

A State Example: Utah’s Plans to Implement the NYTD Youth Outcome Survey

Utah anticipates using NYTD data as a way to expand their Transition to Adult Living (TAL) program and improve services to youth who exit foster care. Rather than surveying a single cohort of 17-year-old foster youth every three years as required by the NYTD regulation, Utah plans to survey all youth in care at age 17 every year and follow up with all youth at ages 19 and 21. Maintaining regular contact with all youth who have transitioned from care enables the State to provide youth with necessary services and referrals to assist them in making a transition to independence. Utah’s foster care system has between 300 and 400 youth age 17 in care during any given year and plans to use automated systems to keep in touch with youth.

Utah plans to begin implementing the NYTD survey in May 2010. This early implementation will allow the State to work out any problems or issues before required NYTD data collection begins on October 1, 2010. Utah has programmed the youth outcome survey for online administration and also has a paper version of the survey instrument. In general, Utah anticipates that the baseline survey either will be administered by the caseworker during a home visit or as a web survey for those youth with email addresses in Utah’s Statewide Automated Child Welfare Information System (SACWIS). TAL coordinators are currently collecting and entering email addresses for all youth who will turn age 17 in the next 6 months. If the caseworker administers the survey, she or he will be able to use the youth’s answers as one assessment of the youth’s strengths and needs. The State plans on administering the follow-up surveys to youth at ages 19 and 21 via the web.

An automated prompt reminder will go out 30 days in advance of a baseline youth’s 17th birthday to let caseworkers know that they need to complete the survey within 45 days following the youth’s 17th birthday. The system will also generate a notification to the worker on the youth’s 17th birthday to make sure the survey gets completed. An automated email with a link to the web survey will also be sent to the youth at this time. The link to the survey will contain an embedded ID number that will allow the system to identify the youth. At the time of the 19-year-old and 21-year-old follow-up surveys, youth will again receive an automated email with a link to the survey. Youth who do not complete the survey within two weeks will receive an automated reminder. After that, a prompt will be sent to the Youth Liaison to locate the youth. The Youth Liaison is a former foster youth who works in the State administrative office and maintains contact with several youth.

Contact information will be collected at the time of each survey and at case closing and will include the youth’s address, home and cell phone numbers, email address, social networking site user names, and contact information for five other people who will know how to locate the youth. Regular contact with youth will be made by the regional TAL coordinators and by the Youth Liaison. The Youth Liaison will set up a social networking site for the youth and send out updates about scholarships and other opportunities and services available to youth who have transitioned from foster care. Youth will be encouraged to report any changes in their address or phone numbers as these occur and these will be updated in the SACWIS system.

Utah has been marketing NYTD to foster youth through their annual Youth Summit meetings, their local Youth Councils, and spreading the word to the TAL coordinators. Utah is not planning to provide any financial incentives to youth for completing the survey. However, current foster youth in the State have indicated that the opportunity to give feedback that will be used by the State to improve services for other youth transitioning from foster care to independence is a strong motivator for participation. Finally, Utah plans to provide updates to NYTD survey participants on how the data are being used to improve services.

For more information on Utah’s implementation plans, contact Dr. Navina Forsythe, Director of Information Systems, Evaluation & Research, Utah Division of Child and Family Services, (801)538-4045, [email protected].

Summary

While the NYTD regulation contains certain requirements (required survey questions, mandatory timelines and prescribed participation rates), States have the flexibility to determine which methods they will use to engage youth in outcomes data collection and to administer the NYTD youth outcome survey. This document is intended to help States decide on a method for administering the survey in order to assist in the development of a customized plan to collect high quality information on the collective outcomes of youth. Collecting high quality information on youth in the baseline and follow-up populations will assist the State in assessing its own performance in preparing youth for a transition to adulthood.

References

Chang, L., and Krosnick, J. (2009). RDD telephone versus internet surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 73, 641-678.

Couper, M. (2008). Designing effective web surveys. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dillman, D., Phelps, G., Tortora, R., Swift, K., Kohrell, J., Berck, J., and Messer, B. (2009a). Response rate and measurement differences in mixed-mode surveys using mail, telephone, interactive voice response (IVR) and the internet. Social Science Research, 38, 1-18.

Dillman, D., Smyth, J., and Christian, L. (2009b). Designing mixed mode surveys: Joint program in survey methodology two-day short course, Arlington, VA.

Dillman, D.; Smyth, J.; and Christian, L. (2009c). Internet, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method, 3rd Edition, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Gentry, R., and Hood, C. (2008, May). Offering respondents a choice of survey mode: Use patterns of an internet response option in a mail survey. Presented at the American Association for Public Opinion Research, New Orleans, LA.

Lenhart, A., Hitlin, P., and Madden, M. (2005) Teens and technology. Pew Internet & American Life Project, Pew Research Center.

Lenhart, A; Madden, M, Smith, A., and Macgill, A. (2007). Teens and social media. Pew Internet & American Life Project, Pew Research Center.

Kiecker, P. and Nelson, J. (1996). Do interviewers follow telephone survey instructions? Journal of the Market Research Society, 38, 161-176.

McCabe, S (2004). Comparison of web and mail surveys in collecting illicit drug use data: A randomized experiment. Journal of Drug Education, 34, 60-72.

McMorris, B., Petrie, R., Catalano, R., Fleming, C., Haggerty., K., and Abbott, R. (2008). Use of web and in-person survey modes to gather data from young adults on sex and drug use: An evaluation of cost, time, and survey error based on a randomized mixed-mode design. Evaluation Review, 33, 138-158.

Tourangeau, R. and Smith, T. (1996). Asking sensitive questions: The impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context. Public Opinion Quarterly, 60, 275-304.

Wright, D., Aquilino, W., and Supple, A. (1998). A comparison of computer-assisted and paper-and-pencil self-administered questionnaires in a survey on smoking, alcohol, and drug use. Public Opinion Quarterly, 62, 331-353.

For more information, please contact:

N ational

Resource Center for Youth Development

ational

Resource Center for Youth Development

NRCYS at the University

of

Oklahoma Outreach

918-660-3700

N ational

Resource Center for Child Welfare Data and Technology

ational

Resource Center for Child Welfare Data and Technology

703-263-2024

1 Non-response bias occurs when those who respond to the survey differ in their outcomes from those who do not respond. As non-response increases, the results of the survey may no longer by representative of the larger population, thereby biasing the results.

2 A skip pattern is a sequence of questions asked and skipped in a logical way. For example, survey questions related to NYTD data elements 42-44 are not asked of youth in foster care. On a paper-based survey administered to a youth in follow-up population that is still in foster care, a clearly worded skip pattern would direct the youth to jump over the group of questions related to data elements 42-44 and continue to the other youth outcome survey questions.

-

| File Type | application/msword |

| File Title | NYTD TO AFCARS RACE MAPPING |

| Author | ICF |

| Last Modified By | Miguel Vieyra |

| File Modified | 2010-06-28 |

| File Created | 2010-04-27 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy