Response to Public Comments (60-day period)

EDSCLS Benchmarking Study 2016 Response to 60-day Public Comments.docx

ED School Climate Surveys (EDSCLS) Benchmark Study 2017 Update

Response to Public Comments (60-day period)

OMB: 1850-0923

Docket: ED-2015-ICCD-0081, School Climate Surveys (SCLS) Benchmark Study 2016

Comments On: ED-2015-ICCD-0081-0001, FR Doc # 2015-15438, ED School Climate Surveys (EDSCLS) Benchmark Study 2016

Public Comments Received During the 60-day Comment Period and NCES Responses

Comment Numbers: 1

Document:

ED-2015-ICCD-0081-0005

Name: jean public

the

taxpayers are revolting. there is no reason for the fat cat

bureaucracy in corrupt washington dc to have a school cliame sur

veyl

in the usa. from every school in america. this dept mission is on

education.not asking every thing about every schoo

this

agency is wasting our money. we already pay taxes for loca, ocunty

and state education bureaucracies with all their added agencie, this

one in washington dc is doing absolutely noting to improve education.

they are in fact a hindranc to the efforts of the other 3 agencies at

the local, county and state level because of all the ime and money

they take up.

close down this survey.no need for it. close

down the entire us dept of education.it is a time wastint fat cat

bureaucracy accomplishing nothing a all. this comment is for the

public record. the american pubilc asks for downsizing in the fat cat

federal bureaucracy. this is a non essential tak

RESPONSE: N/A

Comments

related to Measuring Connectedness and Staff Satisfaction, and

Flexibility of EDSCLS

Comment Numbers: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Document:

ED-2015-ICCD-0081-0006

Name: Derek Peterson

Address:

Lidgerwood, ND, 58053

Organization: Institute for Community and Adolescent Resilience

Several

states have school climate questionnaires and surveys. Research shows

a strong connection between school attachment and student

achievement. (National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health.) It

would be a wise investment to:

1) identify the indicators of

school climate that lead to connectedness.

2) create valid and

reliable questions for each indicator.

3) survey middle and high

school aged students.

4) correlate the school climate and

connectedness to student achievement.

5) refine the instrument.

Document:

ED-2015-ICCD-0081-0007

Name: Jane Beck

Address:

Homer, AK, 99603

Organization: Project GRAD Kenai Peninsula

I have seen several versions of school climate questionnaires and surveys over the years. Although many of them attempt to gauge the level of respect a student feels at school, they often miss the important link of real "connection" to adults. Research shows that there is a strong connection between the level of "connectedness" a student has with his/her school, school staff, administrators, peers, and adults (both in and out of the school setting) with academic achievement levels. May I suggest that if a national school climate survey is developed, that it includes valid and reliable questions that indicate and determine the depth and breadth of these important connections? With this data, schools, administrators, teachers, counselors, parents, guardians, and the students themselves might see how building strong connections among students and adults will have a positive outcome for academic achievement.

Document:

ED-2015-ICCD-0081-0008

Name: Scott Butler

Ed.D.

Address: Omaha, NE, 68135

Organization: Eklund Consulting

My

doctoral dissertation focused on creating and analyzing a framework

that looked at the day to day experience of teachers in their

classrooms. A colleague and I wrote and piloted a school culture

survey for teachers that linked teacher experiences of the workplace

to teacher job satisfaction. Our tool, The School Workplace

Satisfaction Survey, has been an invaluable tool for many schools

across the country that wish to improve their school culture. We base

our work with schools on the concept that if we want to have

effective school cultures for kids, we must first of all create

effective cultures in which adults can work collaboratively.

Roland

Barth (2006) said it better than anyone: One incontrovertible finding

emerges from my career spent working in and around schools: The

nature of relationships among the adults within a school has a

greater influence on the character and quality of that school and on

student accomplishment than anything else.

The survey

developed for my dissertation is now routinely used in schools

through the consultation efforts of Eklund Consulting

(www.eklundconsulting.com). We strongly support the idea of creating

a way by which we measure and track the school culture for adults.

Other industries are far ahead of school in examining how workplace

culture impacts productivity. Most major cities regularly collect

data and name deserving companies as great places to work. Why

shouldnt we do the same for schools? We envision a day when schools

will be able to use their status as a named Great Place to Teach

(based upon data) to drive their recruiting and hiring

efforts.

Multiple studies have found that approximately

half of all teachers leave the profession within their first five

years of practice. When asked why they are leaving, most all cite

issues directly related to workplace culture. We know that teachers

improve with experience. If we are hemorrhaging half of our

workforce, how can we ever build a group of teachers nationally that

have developed the skills and talents needed to truly inspire and

teach kids at the highest levels.

Data collection alone,

however, cannot elicit change. All too often, the results of school

culture surveys are simply returned to the building leaders who is

expected to add improve school culture to a list of mandatory tasks

that is already far too long. The proactive work of improvement gets

pushed to the side and replaced by a seemingly never ending list of

tasks that must be completed in a timely manner. In our practice with

schools, we find that we cant simply report data, leave, and return

in a year or two to measure change. We maintain active coaching

relationships with all of our clients to make certain this very

important work stays on the front burner. In fact, every school that

has worked with us has demonstrated statistically significant change

at p < .05.

In short, we love the idea for this study

AND we have an amazing tool and process that should be part of the

mix.

Docket:

ED-2015-ICCD-0081

Name: Ann

Higgins-D'Alessandro

Address: Bronx, NY, 10458

Organization: Fordham University

Hello

This may be a worthwhile effort, but if successful

in meeting the goals you outline, it will eventually stymie the field

as it will lead to just one instrument being used in research and

practice, and thus eventually to no longer useful results. This is

not the argument that schools are all different and local situations

are different, although these likely pertain. The argument is that

science and good practice do not progress through asking and

answering the same questions time after time even in different

contexts (schools). Science progresses and breakthroughs in

understanding and practice come from innovative thinking and doing.

Science is innovation primarily, and measurement secondarily. The

first asks--what about this phenomenon do we want/need to understand

and the second asks how can it best be measured--what is or are the

unit(s) of analysis. I think that the phenomenon of school climate is

often ill-defined, and thus attempts to measure it are from the

outset unsucsessful.

I agree that this effort may be

worthwhile as it potentially could identify trends and insights not

yet identified in other studies and meta-analyses, depending upon how

it is conceived and executed. To improve these chances, I would

encourage its authors to further circumscribe its goals, especially

by introducing the fact that its usefulness will be time-limited.

Second, the more encompassing the final instrument, the more rigid it

will be, and the more apt it will be to miss changes in society, in

neighborhoods, and school systems that could render data that is

distorted and/or not useful.

Sadh and I developed and

published the School Culture Scale in 1998. Because it was

theoretically well-defined and operationalized, it has and is being

used world wide, translated into 5 other languages. Its usefulness is

also based on the facts that it is short, and flexible, with

subscales that measure central constructs of school culture that are

valid and reliable, as is the measure as a whole. It is adaptable--it

can be used with specifically-written instructions for schools or

classrooms, for students of different ages (3-12 grades, in college),

teachers, administrators, parents, staff, and has been adapted for

use in sports teams and workplaces for people of all ages. I believe

it has proven so useful because it is grounded in theory and focuses

on operationalizing a very specifically defined construct (the

culture of settings), and thus its role in understanding the larger

setting or context and the behavior of the people within it is clear.

In my years of research, school culture using our measure plays a

mediating role in the relationship of interventions/school practices

with student and teacher outcomes. In the workplace it seems to play

a moderating role. Culture is the aspects of climate that are

intentionally changeable by those within a setting--specifically its

norms, values, and relationships.

I am not suggesting that

my own measure should be part of this larger undertaking, although

would welcome a conversation about it if the authors thought it

useful. However, my POINT is that larger measures usually end up

measuring several constructs that are more or less pasted together

and that these constructs themselves may have different relationships

with each other in different settings and contexts; these differences

get covered over, clouded, and often lead to no or unclear results

with other constructs being examined (for instance, interventions,

student and teacher outcomes). Thus, I suggest that this project

think of creating a group of measures, each operationally defining a

very well-defined construct, and that hypothetical models of the

relationships among the measures (as well as with other variables) be

generated based on prior research and theory and tested as part of

this study.

In Summary, remember the great social

experiments of the 1970's when researchers were asked to evaluate

different pilot social and welfare programs. These extensive and very

expensive evaluation research studies showed, by and large, that

there were no significant effects of any of the programs on outcomes

in relationship to control samples or to other programs (see

EVALUATION: A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH, 7th Edition, by Peter Rossi,

Howard Freeman, and Mark Lipsey, Sage Publications, 2004, for a brief

description). Thus, I suggest your project use theoretically strong,

highly targeted foci and acknowledge any large measure of school

climate will have time-limited usefulness. Finally, I suggest that

the authors first question how worthwhile it is to do this study,

what the many theories and empirical studies of school climate have

already told us. If the decision is to move ahead with research

examining school climate, a large and messy concept, it do so, only

after very extensive measurement development.

my best on

this undertaking.

Document:

ED-2015-ICCD-0081

Name: Rebecca Sipos, Rebecca

Bauer

Address: Washington, DC, 20006

Organization: Character.org

Collection of school climate data is necessary because the

implications of the quality of school climate are wide reaching. In

our organizations 20+ years working with schools, we have found that

school climate significantly affects students' academic performance.

In addition, a positive school climate decreases discipline issues,

including instances of bullying and helps to promote better mental

health amongst students and teachers.

The information that

would be collected from the proposed survey is necessary to establish

a baseline of school climate scores, which would allow us to assess

how impactful our initiatives are. The data from the survey will be

helpful not only to our organization and organizations like ours, but

also to educators themselves, particularly school leaders.

The

quality of the information collected will be most informative if it

collects a wide variety of data regarding climate, but focuses in on

the pieces of information that most directly impact students' current

well-being and future success. With this in mind, I encourage that

the School Climate Surveys used include items regarding

student-teacher relationships, parent-teacher relationships,

students' relationships with peers and bullying. In addition, in

order to measure the success of a school's climate in promoting

character and 21st century skills, I advise that items that address

staff and students' attitudes toward and the school's culture

regarding empathy and integrity, also be included.

We at

Character.org support the department's efforts to measure these

qualities that we feel are as important as academic success.

RESPONSE:

Dear Mr. Peterson, Ms. Beck, Mr. Butler, Professor Higgins-D'Alessandro, and Ms. Sipos,

Thank you for your comments submitted during the 60-day review process on the ED School Climate Surveys (EDSCLS) Benchmark Study 2016. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) appreciates your interest in EDSCLS. The Benchmark Study will provide a national comparison point for users of the ED School Climate Surveys (EDSCLS). EDSCLS will be made freely available to all schools and school systems.

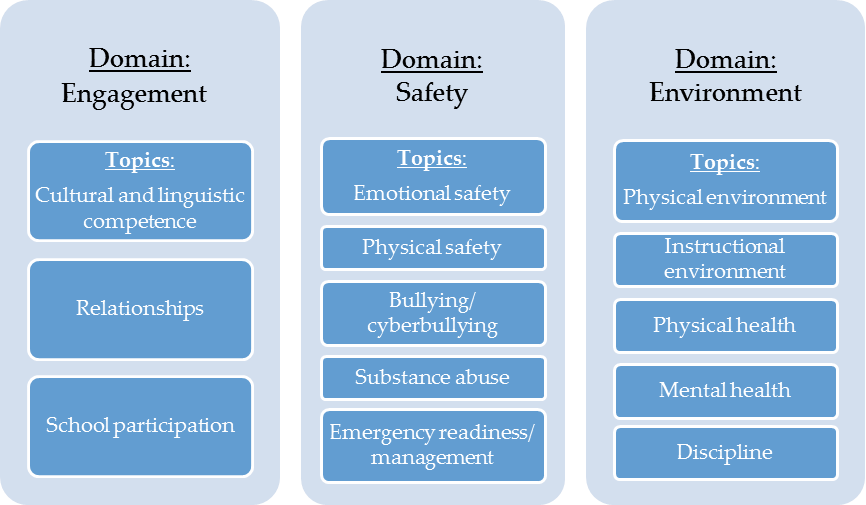

EDSCLS is designed to collect school climate information from grade 5-12 students, their parents, and all instructional and noninstructional staff in the public schools serving these students. The content domains and topical areas measured are based on the Office of Safe and Healthy Students (OSHS) model, which includes three domains of interest: engagement, safety, and environment. Figure 1 displays the three domains and their associated topical areas.

Figure 1. EDSCLS model of school climate

Measuring Connectedness

The domains that drove development of EDSCLS do not include connectedness as an independent topic, but items in the engagement domain measure the relationship among students, between students and adults at schools, between schools and parents, and students’ participation in school activities and events. A scale for engagement and its three subscales – cultural and linguistic competence, relationships, and school participation – have been created and are collected and reported through the EDSCLS platform. The topic of bullying is included in the safety domain and a subscale on bullying/cyberbullying has also been created and is collected and reported through the platform within the safety domain.

NCES does not have plans to link school climate data with student achievement. However, EDSCLS allows education entities that administer EDSCLS (schools, districts, or states) to relate information collected from the surveys to school and school system achievement data. The EDSCLS platform also allows education entities to add new items (e.g., new or existing connectedness items of interest to districts or states) to the end of the instruments to increase the coverage of the EDSCLS and to establish relationships between school climate scales with other measures or indicators.

Measuring Staff Satisfaction

While EDSCLS does not have a specific focus on adult workplace experiences, NCES’s Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS) and National Teacher and Principal Survey (NTPS) (a redesign of SASS), collect extensive data on teacher and principal job work-place experiences, job satisfaction, and mobility. The items in the EDSCLS measure the teachers’ and staff perceived school climate from the above 13 perspectives. The items in the engagement domain are focused on measurement of the relationship among adults, and between students and adults at schools. Though EDSCLS does not directly measure their job satisfaction, high scale scores on these topics and domain reflect a favorable view of work conditions. As mentioned above, EDSCLS also allows education entities that administer EDSCLS (schools, districts, or states) to add new items (e.g., adding job satisfaction items to link the school climate scores with job satisfaction indicators) and use the resulting data for further analyses.

Because the EDSCLS platform is designed to be a free-to-use tool, the review of existing survey items focused on nonproprietary sources.

Flexibility of the EDSCLS platform

The released EDSCLS platform allows the platform users (schools and other education agencies) to add new items to existing instruments and provide flexibility to meet new data collection needs due to changes in society, in neighborhoods, and school systems.

Development and Evaluation of the Instruments

Please note that the EDSCLS survey instruments recently went through several rounds of evaluation and refinement to ensure that the resulting data collection tool produces reliable and valid measures. The development started in 2013 with a school climate content position paper – a review of the existing school climate literature and existing survey items. A Technical Review Panel (TRP) meeting was held in early 2014 to recommend items to be included in the EDSCLS. The EDSCLS draft survey items were then created by building on the existing items and recommendations from the TRP. In the summer of 2014, cognitive interviews were conducted on the new and revised items in one-on-one settings with 78 individual participants: students, parents, teachers, principals, and noninstructional staff from the District of Columbia, Texas, and California. The pilot test of the EDSCLS took place in 2015. It was an operational test, under “live” conditions of all components of the survey system (e.g., survey instruments and data collection, processing, and reporting tools). A convenience sample of 50 public schools that varied across key characteristics (region, locale, and racial composition) participated in the pilot test. The EDSCLS platform was tested at the state level (containing multiple districts in one platform), district level (containing multiple schools in one platform), and the school level (containing only one school in the platform). All survey questionnaires were administrated online through the EDSCLS platform. The data from the pilot test were used to develop the final EDSCLS survey instruments and construct scales for topic areas and domains based on confirmatory factor analyses and Rasch modeling (see Appendix D). About a third of the items, those that proved problematic or redundant, were removed from the instruments after the pilot test.

Comment

related to Measuring Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity across

Federal Surveys

Comment Number: 7

Document:

ED-2015-ICCD-0081-0014

Name: Amy Loudermilk

Address: Washington, DC, 20006

Organization: www.thetrevorproject.org

Re: Comment Request for Agency Information Collection Activities,

(2015-15438)

Dear Ms. Valentine,

The Trevor Project is pleased to have the opportunity to deliver comments for the School Climate Surveys (SCLS) Benchmark Study 2016. We appreciate the opportunity to submit comments to the Department of Education (DOE) to help further enhance the quality and clarity of information being collected in the federal and non-federal climate surveys examined in the Benchmark Study. As a youth-focused organization, Trevor supports the SCLS in providing schools with access to survey instruments and a survey platform that allow for the collection and reporting of school climates nationwide. We absolutely recommend the enactment of the national SCLS benchmark study that will collect data from a nationally representative sample of schools across the country, in order to create a national comparison points for users of SCLS.

The Trevor Project is the leading national, nonprofit organization providing crisis intervention and suicide prevention services to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning (LGBTQ) young people through age 24. We work to save young lives through our accredited free and confidential lifeline, secure instant messaging services which provide live help and intervention, a social networking community for LGBTQ youth, in-school workshops, educational materials, online resources, and advocacy. Trevor is a leader and innovator in suicide prevention, especially as we focus on an important, at-risk population: LGBTQ youth. We have compiled these comments in hopes that these survey instruments can continue gathering important information about school climates nationwide, and in the most accurate and precise fashion possible. In the majority of studies that we comment on, we recommend amending the surveys to include questions about a respondent’s sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). While standardized questions have been developed to ask about a person’s sexual orientation, the same is not true about gender identity. Many different state and federal surveys are still field testing questions about gender identity to identify the best way to phrase the question. Because the field of social science hasn’t reached a conclusion yet on the best way to ask this question, we recommend survey drafters work with the All Students Count Coalition in the development of gender identity questions.1 This coalition is comprised of the leading national organizations working on this issue.

Below are our comments on the following ten (10) surveys:

Federal surveys:

Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Beginning Postsecondary Students Survey

Educational Longitudinal Study, High School Longitudinal Study

School Survey on Crime & Safety, Schools and Staffing Survey

Civil Rights Data Collection

National Survey of Children’s Health

State surveys:

California Healthy Kids Survey

Alaska School Climate & Connectedness Survey

Communities That Care Youth Survey

Pride Learning Environment Study

Creating a Great Place to Learn Survey

Comments on Federal Surveys

The first federal study we would like to address is the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). The YRBS is a national school-based study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that monitors health-risk behaviors that contribute to the leading causes of death and disability among youth and adults. We praise its recent inclusion of questions on same-sex sexual contact and orientation. It includes many mediators of LGBTQ status and educational outcomes, but missing from this survey are questions about a respondent’s gender identity. Research has shown transgender individuals have many health disparities, including a higher suicide risk, and schools cannot fully assess risky behavior among the student population if a gender identity question is not asked. We understand that states have opted to ask gender identity questions in the past but have not received data that is reliable or valid; therefore, we urge the CDC to continue working with groups like the All Students Count Coalition to develop questions that perform better in the field. We also call for additional funding to be provided with the goal of increasing the support available to aid states in their development of gender identity questions for their respective YRBS studies.

Next, we want to address three longitudinal studies. First, the Beginning Postsecondary Students (BPS) survey is a longitudinal study that collects data on a variety of topics, including: student demographic characteristics; school and work experiences; transfers; and degree attainment. The study surveys first-time, beginning students at the end of their first year, followed by three and six years after first starting in postsecondary education. The next study is the Education Longitudinal Study (ELS), which collects data from questionnaires directed to students, parents, math and English teachers, and school administrators. The survey addresses the issues of educational standards, high school course-taking patterns, dropping out of school, the education of at-risk students, the needs of language minority students, and the features of effective schools. It focuses on students’ trajectories from the beginning of high school into postsecondary education, the workforce, and beyond. The third study is the High School Longitudinal Study (HSLS), which is similar to the ELS in that it focuses on students’ trajectories from the beginning of high school into postsecondary education, the workplace, and beyond. It also provides separate questionnaires for students, parents, teachers, school counselors, and school administrators.

All three studies do not have questions regarding the sexual orientation and gender identity of the questionnaire’s respondents and the respondents’ parents. There is currently no longitudinal data from the education sector that measures LGBTQ status directly. We highly recommend that sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) questions be added to these studies, which would allow for greater analysis of LGBTQ students’ experiences at the individual, school, community, and national levels. In addition, SOGI questions should extend to the parents, too. The survey questions that currently exist in the ELS and HSLS studies ask students to report about their female and male guardians only, and do not allow a student to indicate that their parents are same-sex. Questions 2 – 10 of the Base Year Student Questionnaire (included in the BPS, ELS & HSLS) force students to pick one guardian as the guardian they primarily reside with, and therefore do not take into account students who may be living with both guardians in the same house. The 2010 U.S. Census estimates that one fifth of households with same-sex couples are raising children.2 Additionally, given the recent United States Supreme Court decision in Obergefell vs. Hodges granting same-sex couples the right to marry, it is likely that more couples will be marrying and raising children. However, there is limited research on LGBTQ parents’ experiences with school in their communities, which is vital to understanding the needs and experiences of children with LGBTQ parents.3 These studies must be amended to capture the realities of family structures today to enable the collection of data regarding same-sex couples’ children’s educational experiences.

The next three studies we would like to address are not longitudinal but are similar in their focus to the three previously mentioned studies. First, the School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS) is the National Center for Education Statistics’ sample survey of the nation’s public schools and is designed to provide estimates of school crime, discipline, disorder, programs and policies. It is administered to public primary, middle, high, and combined school principals in the spring of even-numbered school years. The SSOCS successfully addresses questions regarding staff training in crisis prevention and intervention, and we applaud its question regarding harassment toward students based on sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Where we believe this survey could be improved is by adding questions that would obtain data on suicide prevention and intervention trainings for school personnel and suicide policies. The way the survey defines violence as “actual, attempted or threatened fight or assault” is not inclusive of self-directed violence. Yet we know how incredibly prevalent this type of violence remains in schools. However, the survey does indicate an understanding that suicide is a type of violence and has an impact on crime and safety because it asks principals to report on the number of suicide threats or incidents. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among young people ages ten to twenty-four.4 LGB youth are four times more likely, and questioning youth are three times more likely, to attempt suicide as their straight peers.5 Nearly fifty percent of young transgender people have seriously thought about taking their lives, and one-quarter report having made a suicide attempt.6 What the survey lacks is a question asking if schools have trained staff on suicide intervention/prevention and a question asking if the school has a written policy about what to do in the event of a suicide attempt or threat. That is the link that will allow advocates, school administrators and law enforcement to attempt to ameliorate the suicide incidents in schools. Gun violence, for example, is dealt with in a holistic manner in the survey by not only asking about the number of gun violence incidents, but also asking if: schools have clear policies on guns in school; students and staff are informed about the dangers of gun violence; and if there are external groups that come into the school to inform children about alternative conflict resolution approaches. The survey should also treat suicide in a holistic manner by asking similar questions; it is the only way to get this type of information. This is the perfect survey to ask these types of questions, particularly about the number of suicide incidents at a school, because the data is analyzed and reported in aggregate. This would allow researchers to draw conclusions about trends which could in turn prompt life-saving intervention and prevention efforts. For example, the Western mountain states have consistently higher than average suicide rates, and this survey could examine whether that trend holds true for youth suicide attempts. Again, because the data is reported in aggregate, this would still provide confidentiality for students who have made attempts and prevent individual schools from being ostracized because of their rates.

The Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS), is a series of related questionnaires that provide descriptive data covering a wide range of topics, including: teacher demand; teacher and principle characteristics; general conditions in schools; principals’ and teachers’ perceptions of school climate and problems in their schools; teacher compensation; district hiring and retention practices; and basic characteristics of the student population. The third study, formerly the Elementary and Secondary School Survey, is the Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC), which collects data on key education and civil rights issues in public schools. The CRDC obtains data on student enrollment and educational programs and services disaggregated by race/ethnicity, sex, limited English proficiency and disability. Similar to the longitudinal studies, these surveys do not contain SOGI questions, leaving a gaping hole in the data collected. These surveys must be amended to include SOGI questions given that states and the federal government are affirming the civil rights of LGBTQ persons with respect to schooling, hate crime protections and many other areas.

The final federal survey we’d like to address is the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH), which is sponsored by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). This study examines the physical and emotional health of children 0-17 years of age and places special emphasis on factors that may relate to their well-being, including: medical homes; family interactions; parental health; school and after-school experiences; and safe neighborhoods. We applaud its inclusiveness of children with two mothers/female guardians and/or two fathers/male guardians, as well as how it addresses the living environment where suicidal individuals are, or were, present. Where the survey could benefit is in adding questions regarding the sexual orientation and gender identity of the respondent’s child. Obviously, sexual orientation and gender identity are concepts children become aware of as they are growing up; therefore, children and youth will begin to answer these questions as they become aware of their sexual orientation or gender identity. Some youth may be able to answer these questions at ten years old, while others may not be able to answer the questions until they’re thirteen or fourteen. The fact that children will answer these questions at different ages will not impact the validity of the survey; rather it will provide more data to analyze as the questions become age appropriate. The questions should not be required, but given that the survey is concerning children up to age seventeen, these questions will certainly be something young adults can answer. This data will increase the validity and usefulness of the survey. Additionally, while the survey addresses the presence of suicidal individuals in the child’s immediate environment, it does not address suicide attempts of the child or young adult. As suicide is the second leading cause of death among young people ages 10 to 24, HRSA is missing critically important information by not including a question about youth suicide attempts.7 Suicide attempts by children under age twelve are extremely rare, therefore, this question would also be voluntary and one that could probably only be answered by older children. By including optional SOGI and suicide attempt questions, HRSA will get a much more complete picture of what is going on and how to address it.

Comments on State Surveys

The Trevor Project is also pleased to be able to provide feedback on the many non-federal, state-based surveys included in this suite of surveys. Often, survey systems use the same set of questions for both middle and high school student respondents; however, the California Healthy Kids Survey does distinguish between these two groups with separate survey versions. The Elementary School Questionnaire does not contain SOGI questions, which makes sense given the age of elementary school children. However, the Middle School Questionnaire also does not contain a question about students’ sexual orientation or gender identity, and given the age range of 10-18 years old for respondents, it is age appropriate for SOGI questions to be asked. In the section about whether the respondent has been bullied in the past 12 months and what the cause might have been, bullying based upon homosexual orientation is addressed but not bullying based on a bisexual orientation or a person’s transgender or gender non-conforming identity. Lesbian, gay and bisexual students endure high rates of bullying, but transgender students do too, and the survey must ask questions about bisexuality and transgender students in order to obtain data that accurately speaks to all three of the major sexual orientations and gender identities.8 The question is phrased as “[you were bullied] because you are gay or lesbian or someone thought you were;” we recommend another question be added, “(you were bullied) because you are bisexual or someone thought you were.” It is important that there is a different question assessing the bullying rates of gay/lesbians and bisexuals because social science still needs to determine if the bullying rates differ by your sexual orientation. Additionally, another question should also be inserted using the same phrasing to inquire about bullying based on someone’s transgender or gender non-conforming status. In the question, “which of the following best describes you? Mark All That Apply” (Heterosexual (straight); Gay or Lesbian or Bisexual; Transgender; Not sure; Decline to Respond),” the identity of “bisexual” should not be grouped in with “gay” and “lesbian,” because as the question exists now, the phrasing does not extract the most precise and accurate demographical information.

Like the middle school component, the high school version of the California Healthy Kids Survey comprises a section about whether the respondent has been bullied in the past 12 months and what the cause might have been, in which bullying based upon homosexual orientation is addressed but not bullying because a person is bisexual or transgender or gender non-conforming. Our same recommendations to improve the middle school questionnaire also apply here. Only found in the high school version, a question appears that asks, “During the past 12 months, how many times did other students spread mean rumors or lies about you on the internet (i.e. Facebook, Myspace, email, instant message)? (0 times (never); 1 time; 2-3 times; 4 or more times).” This question is important for this age range as cyberbullying is a common issue and very real threat to the mental health wellness of high school students, especially for minority students like LGBTQ youth. In fact, according to the 2013 National School Climate Survey, nearly half of all LGBTQ students (49.0%) had experienced electronic harassment in the past year – in the form of text messages, Facebook, and other social media outlets.9 We fully support keeping this question as is but also recommend adding the same question to the middle school module, since cyberbullying is an equally real threat and experience for that age range.

As is appropriate for the high school age range, one question directly asks, “During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide” (No; Yes)? We applaud the incorporation of proper phrasing (e.g. “consider attempting suicide”) and ask that this question be kept as is. To apply the same comment as mentioned above for the middle school module, in the question, “which of the following best describes you? Mark All That Apply” (Heterosexual (straight); Gay or Lesbian or Bisexual; Transgender; Not sure; Decline to Respond), the identity of “bisexual” should not be grouped in with “gay” and “lesbian,” because as the question exists now, the phrasing does not extract the most precise and accurate information.

The 2015 version of the Alaska School Climate and Connectedness Survey for grades 5 through 12 appropriately asks questions about students’ access to trustworthy and supportive adults, perceived level of safety and student-to-student respect at school, bullying and general degree of acceptance for those with families who may not fall into the “normative” family type. We appreciate the inclusion of these questions. In the section of the survey titled “Respect for Diversity,” there are multiple mentions of “different cultures, races, or ethnicities” but no explicit reference to different sexual orientations or gender identities. We ask that the survey instrument add these two characteristics to those questions. Collecting information about the degree of student respect towards LGBTQ peers in a school is just as important as measuring the respect allotted towards students of “different cultures, races, or ethnicities,” especially given that approximately 74% of students are verbally harassed each year due to their sexual orientation and around 55% due to their gender identity or expression. Another 36.2% and 22.7%, respectively, were physically harassed. Many schools across America are unsafe places (i.e. where baseline acceptance and respect is not given to students for LGBTQ youth), and it is crucial to measure the prevalence of such disrespect.10 Furthermore, there is not a question in this survey that asks the student respondents about their own sexual orientation or gender identity, which is an important piece of demographic information to collect for this age range. Given the frequency of negative treatment of LGBTQ students, and the known affects that can transpire because of these behaviors (e.g. LGBTQ students who experience higher levels of victimization due to their identity are more likely to miss school, fall behind academically, and report higher levels of depression alongside lower levels of self-esteem)11, surveys like this one must ask SOGI questions. Without gaining this basic information, the amelioration of these problems of LGBTQ discrimination and pointed harassment will be all the more difficult to achieve.

The Communities That Care Youth Survey (CTC) uses a risk and protective factor approach to inspect problem areas among youth and is developed by the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP) in the office of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). This survey is for student respondents in grades 6 through 12, yet it does not address sexual orientation or gender identity at any point. We recommend this survey add questions about the student respondent’s sexual orientation and gender identity. The survey asks important questions about drug use and mental health and must add basic SOGI demographic questions in order to fully understand the landscape.

The Pride Learning Environment Survey serves as an in-depth evaluation of students in grades 6 through 12. The survey directly asks its respondents, “Have you thought about committing suicide (A lot; Often; Sometimes; Seldom; Never)” and “Does your school set clear rules on bullying (A lot; Often; Sometimes; Seldom; Never)” which are two questions that are important to ask of students in this age range. This first question, though, does not use proper, sensitive language surrounding the issue of suicide. The use of the word “commit” is extremely stigmatizing, possibly leading students to be untruthful in answering the question because it is phrased in such a stigmatizing and judgmental manner; a more appropriate phrasing would be “have you thought about attempting suicide” or “have you thought about dying by suicide?” The one suggestion we have for this survey is to add a question about the student respondent’s sexual orientation as well as gender identity, which are currently missing and ought to be included alongside the questions about sex and race.

Minneapolis, Minnesota conducts the Creating a Great Place to Learn survey, with two separate versions for staff and students. The student module of the survey, intended for students in grades 5-12, has neither a question about the respondent’s sexual orientation nor gender identity, which both need to be added to this survey. Problematic language appears in the questions about the student’s parents/guardians, as the phrasing occurs as such: “What is the highest grade or class your mother (or step-mother or female foster parent/guardian) completed in school?” In the following question, the same phrasing appears in reference to the “father (or step-father or male foster parent/guardian).” The evident assumption made here is that all students have one female parent or guardian and one male parent or guardian, when many students have only one parent or two mothers or two mothers, etc. Even though one of the answer choices is “don’t know, or does not apply,” this is not a sensitive or justifiable question to ask as it is currently phrased, and there currently is no way for students with same-sex parents to appropriately answer it. Students may easily feel ostracized and unaccepted, by way of not having their family structure properly and accurately represented in the answer options. These questions must be rephrased so as to not specify gender of parents/guardians and to allow for representation of diverse family structures.

Thank you again for the opportunity to provide comments on these vitally important surveys. We look forward to the results of these surveys in 2016. Questions or comments may be directed to Amy Loudermilk, Associate Director of Government Affairs at [email protected] or 202-380-1181.

Abbe Land

Executive Director & CEO

RESPONSE:

Dear Ms. Land,

Thank you for your comments submitted during the 60-day review process on the ED School Climate Surveys (EDSCLS) Benchmark Study 2016. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) appreciates your interest in EDSCLS. The Benchmark Study will provide a national comparison point for users of the ED School Climate Surveys (EDSCLS). EDSCLS will be made freely available to all schools and school systems.

The goal of the EDSCLS student survey is to measure students’ perception of their school climate – their engagement with other people at school, their safety and their learning environment at school. In order to protect student privacy, no items ask students about personal experiences, behavior, or victimization.

The Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment (PPRA; 20 U.S.C. § 1232h; 34 CFR Part 98) prohibits NCES from asking questions about sexual orientation without written parental consent. Prior experience suggests that requiring written parental consent for a student to participate in a survey has a negative effect on participation in the survey. Furthermore, the fact that NCES was tasked with providing a relatively easy to administer school climate survey, a survey requiring written parental consent would not be consistent with that mandate.

To address the aspect of school climate pertaining to sexual orientation, the EDSCLS high school student survey includes the item “Students at this school are teased or picked on about their real or perceived sexual orientation.” Additionally, the released EDSCLS platform allows the platform users (schools and other education agencies) to add new items to existing instruments and provide flexibility to meet new data collection needs due to changes in society, in neighborhoods, and school systems.

1 http://amplifyyourvoice.org/allstudentscount

2 U.S. Census Bureau, 2011, 2013

3 Wimberly, G. L. (Ed.). (2015). LGBTQ issues in education. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association

4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System [Data file]. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars

5 Kann, L., O’Malley Olsen, E., McManus, T., Kinchecn, S., Chyen, D., Harris, W. A., Wechsler, H. (2011). Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contracts, and Health-Risk Behaviors Among Students Grades 9-12 – Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance, Selected Sites, United States, 2001-2009, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60(SS07), 1-133.

6 Grossman, A. H. & D’Augelli, A. R. (2007). Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior 37(5), 527-527. Retrieved from http://transformingfamily.org/pdfs/Transgender%20Youth%20and%20Life%20Threatening%20Behaviors.pdf (The authors of this study state that because they were not able to recruit a representative sample, the generalizability of the results is limited. The study used a convenience sample that was recruited through agencies providing services to LGBT youth. The recruited participants then referred other youth to the study.).

7 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System [Data file]. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars

8 Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Palmer, N. A., & Boesen, M. J. (2014). The 2013 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York, NY: The Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network.

9 Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Palmer, N. A., & Boesen, M. J. (2014). The 2013 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York, NY: The Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network.

10 Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Palmer, N. A., & Boesen, M. J. (2014). The 2013 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York, NY: The Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network.

11 Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Palmer, N. A., & Boesen, M. J. (2014). The 2013 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York, NY: The Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Richard J. Reeves |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-23 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy