Midterm and Final Evaluation

Midline and Final Evaluation Final_Endline Report USDA LRP_NRMC.docx

USDA Local and Regional Food Aid Procurement Program

Midterm and Final Evaluation

OMB: 0551-0046

Decentralized

evaluation for evidence-based decision making

Decentralized

Evaluation

Prepared

by

Team

Leader: Malay Das Team

Member: Animesh Sharma, Shivangi Rai, Jagriti Singh

End

line Evaluation of USDA Local Regional Procurement project in Nalae

District, Luang Namtha Province in Lao PDR

[FY

16-19]

Report

of End line Evaluation

January

2020

WFP

Country Office Lao PDR Evaluation

Manager: Sengarun Budcharern

![]()

Acknowledgements

The NRMC evaluation team wishes to acknowledge the guidance, support, and cooperation received from all the participants in the evaluation.

NRMC takes this opportunity to extend sincere thanks to the distinguished Government officials at the Ministries and departments at national, provincial and district levels for their time and precious inputs.

The NRMC Evaluation Team expresses its gratitude to the members of RBB and Yumiko Kanemitsu, for sharing their useful insights. Their suggestions have immensely helped in enhancing the design of the evaluation. We would also like to thank the staff of international development agencies which kindly took the time to meet us and give us their views on the Local & Regional Procurement program in Lao PDR.

NRMC wishes to sincerely acknowledge the support and guidance received from the staff of the WFP Lao PDR Country Office, especially from Jan Dalbaere, Hakan Tongul, Sengarun Budcharern, Fumitsugu Tosu, Air Sensomphone, Yangxia Lee, Outhai SihaLath as-well-as the WFP staff from Luang Namtha sub-office for assisting with the planning of and facilitating the evaluation mission, and for supplying documentation.

We are grateful to the team from Geo-Sys for their partnership with the NRMC evaluation team throughout the period of evaluation, particularly for their untiring efforts for data collection.

Last but not the least, the evaluation team wishes to acknowledge the cooperation received from all informants, including school children, school head, teachers, parents, cooks, farmers and VEDC members, during the primary data collection.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this report are those of the Evaluation Team and do not necessarily reflect those of the World Food Program. Responsibility for the opinions expressed in this report rests solely with the authors. Publication of this document does not imply endorsement by WFP of the opinions expressed.

The designation employed and the presentation of material in maps do no imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WFP concerning the legal or constitutional status of any country, territory or sea area, or concerning the delimitation of frontiers.

Table of Contents

1.1. The Subject of the Evaluation 1

Alignment and Contribution to Government Strategies 12

Coherence with WFP Country Program (2017-2021) 13

Capacitating Smallholder Farmers and DAFO Officials 14

Providing Diverse and Nutritious Food to SMP 15

Gender Equality and Empowerment of Smallholder Farmers 15

Achievement of Outputs and Outcomes of the Intervention 17

Enhanced Access to Food Supply and Voluntary Contributions to SMP 24

Gender Equality and Empowerment 26

Changes in Dietary Diversity Score 26

Replication in Other Districts 27

Partnership with Government Agencies for Implementation 28

Efficiency of Farmer Groups 29

Flexibility and Adaptability of Program 30

Unintended Effects of the Program 32

Use of Improved Agriculture Techniques 32

Gender and Human Rights Impact 33

Capacity Building of Farmers, MAF Officials and Other Partners 33

Ownership of Community-Driven School Lunch 34

Replicating the LRP Program 35

3. Conclusions and Recommendations 35

3.1. Overall Assessment/ Conclusions 35

3.2. Good practices and Lessons Learned 36

Annex A Map of LRP Intervention Area 41

Annex B Evaluation Mission Schedule 42

Annex C Scope of Work for Activity Evaluation 46

Annex D Primary Users of Evaluation Report and Stakeholders Interviewed 47

Annex E Broad activities planned under LRP program 48

Annex F Planned Outputs and Beneficiaries 50

Annex G Planned Outcomes of USDA LRP-Lao PDR 51

Annex H Results Framework of WFP-Lao PDR: LRP (FY16) 60

Annex I Budget for WFP-LRP Program 61

Annex K Roles of Key Partners 66

Annex L Brief Report from Scoping Visit 67

Annex N Approach and Methodology 88

Annex O List of Stakeholders Interviewed 98

Annex Q Mapping of National Priorities and Logical Framework of LRP 102

Annex R List of Tables for Effectiveness Indicators 109

Annex S Data Collection Tools 114

Annex T Map for Province Oudumxay 180

Annex V Glimpses from Validation Workshop 193

List of Tables

Table 1: Snapshot of Program Subject 3

Table 2: Value of Sales Production under LRP 21

List of Figures

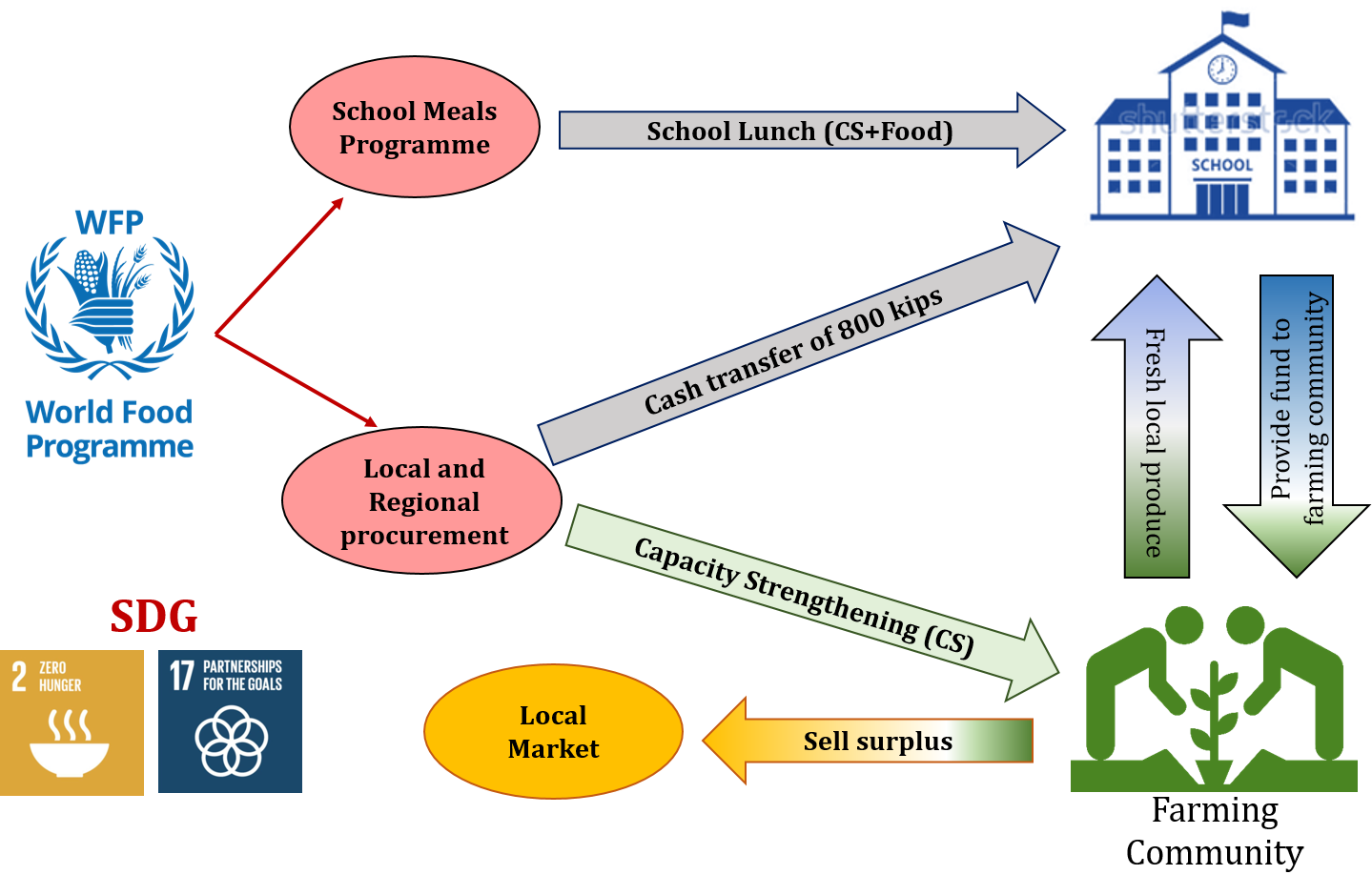

Figure 1: The SMP-LRP linkage 2

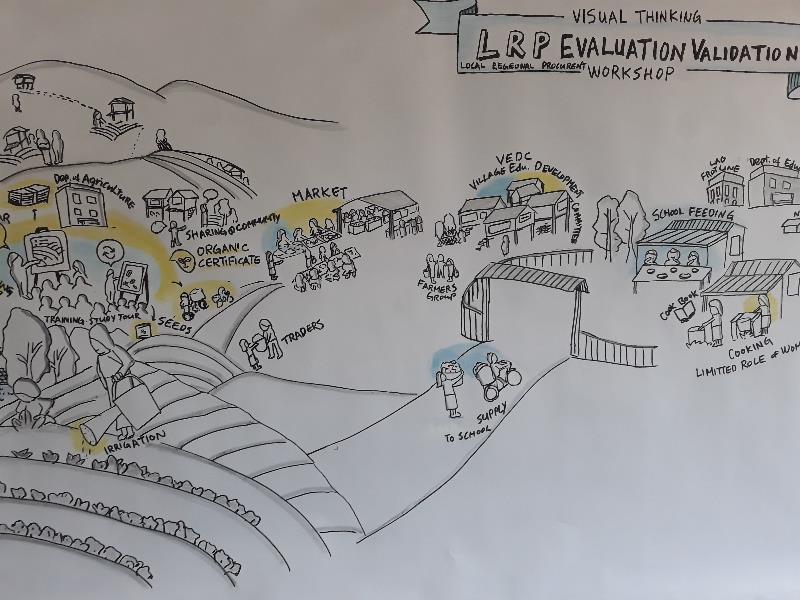

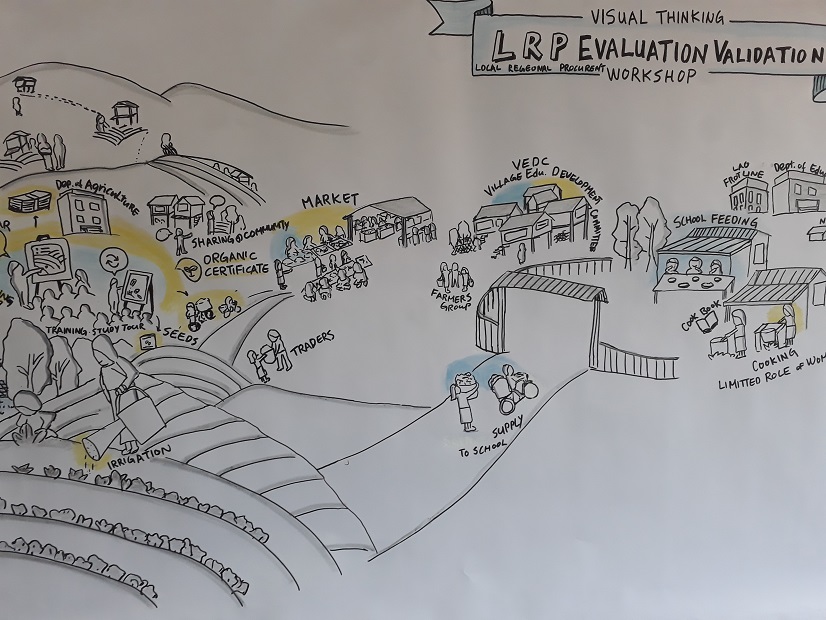

Figure 2: Visual thinking for validating results 10

Figure 3: Vegetable farming using Greenhouse technique 14

Figure 4: Students having lunch at school 15

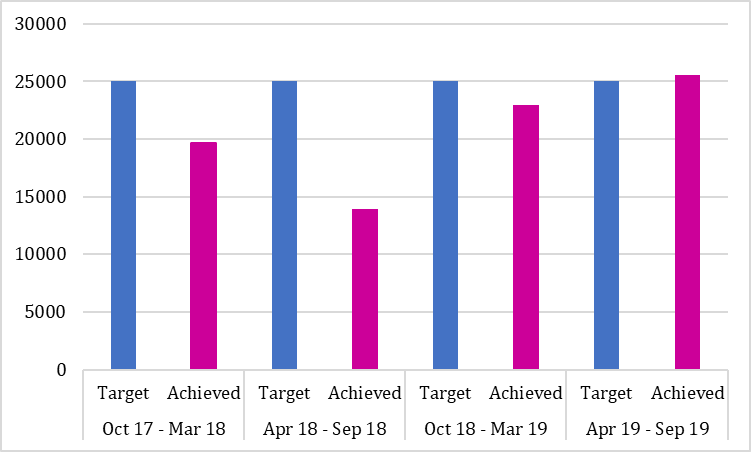

Figure 5: Number of individuals benefitting directly through LRP 17

Figure 6: Number of individuals benefitting indirectly through LRP 18

Figure 7: Individuals who received short-term agricultural training 20

Figure 8: Percentage of LRP farmers growing different vegetables 22

Figure 9: Variety of vegetables grown by LRP supported farmers 23

Figure 10: Percentage of LRP farmers cultivating in one or two seasons 23

Figure 11: Percentage of LRP farmers implementing best practices 24

List of Acronyms

ATSC Agriculture Technical Service Centre

CBTs Cash-based transfers

CO Country Office

CP Country Program

CPE Country Program Evaluation

CSP Country Strategic Plan

CRF WFP Corporate Results Framework

CRS Catholic Relief Services

DAC Development Assistance Committee (of the OECD)

DAFO District Agriculture and Forestry Office

DDS Dietary Diversity Score

DEQAS Decentralized Evaluation Quality Assurance System (of WFP)

DESB District Education and Sports Bureau

DFAT Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia)

DHO District Health Office

DP Development Partner

DTEAP Department of Technical Extension and Agro-Processing

EB Executive Board (of WFP)

ECE Early Childhood Education

EM Evaluation Manager

EQ Evaluation Question

EQAS Evaluation quality assurance system (of WFP)

ER Evaluation Report

ESDF Education Sector Development Framework

ESDP Education Sector Development Plan

ET Evaluation Team

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization

FFA Food assistance For Assets

FFE Food for Education

FGD Focus-group discussions

FLAs Field level agreements

GDI Gender Development Index

EEW Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women

GoL Government of Lao PDR

HDI Human Development Index

HDR Human Development Report

HGSF Home Grown School Feeding

HHs Households

HQ Headquarters

ICT Information and Communication Technology

IDI In-depth interview

IEC Inclusive Education Centre

IFPRI International Food Policy Research Institute

IGDs Individual and groups discussions

INGO International non-governmental organization

IR Inception Report

JICA The Japan International Cooperation Agency

KIIs Key informant interviews

LDC Least developed Country

LRP Local and Regional Procurement

LWU Lao Women’s Union

LWF Lutheran World Federation

LYU Lao Youth Union

MA Monitoring Assistants

MAF Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry

MCQ Multiple Choice Questions

MDG Millennium Development Goal

MoES Ministry of Education and Sports

MoH Ministry of Health

MOUs Memorandum of Understanding

MSC Most Significant Change

MT Metric Ton

NFS Nutrition and Food Security

NFR Note for the record

NNS National Nutrition Strategy

NNSPA National Nutrition Strategy and Plan of Action

NRMC NR Management Consultants India

NSEDP National Socio-Economic Development Plan

NSMP National School Meals Program

NTFPs Non-timber forest products

OECD Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

OEV WFP Office of Evaluation

PAFO Provincial Agriculture and Forestry Office

PDR People’s Democratic Republic – Lao

PHO Provincial Health Office

PESS Provincial Education and Sports Services

RBB Regional Bureau Bangkok

RRB Regional Rural Banks

SDG Sustainable Development Goal

SITREP Country Situation Report

SMAP School Meals Action Plan

SMP School Meals Program

SPR Standard Project Report

TOC Theory of Change

TOR Terms of Reference

UNDP United Nations Development Program

UNEG United Nations Evaluation Group

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund

UNFPA United Nations Population Fund

UNCT’s United Nations Country Team

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

USDA United States Department of Agriculture

VEDC Village Education Development Committee

WASH Water Sanitation and Hygiene

WB World Bank

WFP World Food Program

Executive Summary

Introduction

The activity evaluation for the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Local Regional Procurement (LRP) program in Nalae district of Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR), commissioned by the WFP country office of Lao PDR (WFP CO), occurred over June-November 2019. The evaluation covered the LRP program period from January 2017 till June 2019.

The primary stakeholders and users of this evaluation include: (1) WFP CO, (2) USDA, (3) the Regional Bureau Bangkok, (4) WFP Headquarter, (5) Office of Evaluation, and (6) Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF) and Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES) of Lao PDR.

Lao PDR has prioritised meeting the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 to ‘end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture’. The USDA McGovern-Dole School Meals Program (SMP) is a step towards this, by way of serving meals in schools. Under SMP 2017-21, the community is expected to contribute vegetables for the meals. The LRP program was conceptualised to ensure the sustainability of SMP; it aimed at supporting smallholder farmers to produce vegetables and sell them to schools. The surplus was to be consumed at home and sold in the open market, thus helping augmentation of the household income. The LRP program was piloted across 47 villages of Nalae district. The objectives of LRP included: (1) sustained supply of fresh food for school lunches by providing cash1 support to schools; (2) increased intake of vegetables by students; (3) continuous application of improved agricultural techniques; (4) increased ownership of the school lunch by the communities; and (5) promotion of equal access to agricultural extension for male and female farmers.

Objectives of the evaluation

Accountability: This evaluation assessed the USDA LRP performance and results of the implementation.

Learning: The evaluation determined the reasons why certain results occurred, or not, to derive good practices and lessons learnt, providing evidence-based findings to inform future operational and strategic decision-making.

Methodology

The evaluation used the OECD-DAC criteria to assess the relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, sustainability and impact of the LRP program through the lens of equality and inclusion of both genders and vulnerable groups. It provided an evidence-based assessment of the activities and outcomes using a Logic model.

The evaluation adopted a quasi-experimental evaluation design, which included the selection of LRP-supported (intervention) and non-supported (control) villages. A mixed-method approach was deployed to answer every evaluation criterion using key informant interviews (KIIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs). The evaluation design also included Most Significant Change (MSC), which involved identification and documentation of seven case studies in intervention villages, highlighting personal accounts of change of farmers who participated in LRP. Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women (GEEW) was mainstreamed in the evaluation by ensuring a gender-balanced team, collecting information for boys, girls, men and women, and undertaking a gender-disaggregated analysis.

The evaluation involved systematic random sampling for a selection of villages across lowland, upland and mountain regions.2 A total of 15 intervention and five control villages were covered. At the village level, FGDs were conducted with parents, farmers and Village Education and Development Committee (VEDC) members, while In-depth Interviews (IDIs) were carried out with schoolchildren, teachers and cooks. IDIs were also conducted with officials of the Government of Lao PDR (GoL) and other stakeholders.

Three significant limitations of this study include: (1) the inability of the evaluation design to allow attribution of any changes to the program, (2) the inability of children in standards I-II to comprehend and respond to the questions, and (3) unavailability of program farmers in certain villages.

Key Findings

Relevance

The LRP program was designed to provide the means to the community to move towards self-sufficiency in supplying vegetables for school meals, improving the dietary diversity of the community, and augmenting the income of smallholder farmers. With piloting of LRP in a disadvantaged region, the inclusive nature of the program was demonstrated.

The program partnered with the government for its implementation. District Agriculture and Forest Office (DAFO) officials attended training workshops, undertook exposure visits in Oudomxay province in September 2018, and in turn conducted training sessions for smallholder farmers from the intervention villages.

The LRP program was in line with the priorities stated in the country’s Agriculture Development Strategy to 2025 document, such as increasing multiple crop agricultural practices and diversification of food products to achieve food security. The program was also aligned with the National Nutrition Strategy to 2025, underpinned by inter-sectoral coordination.

LRP’s logical framework was in complete sync with three of the four strategic outcomes (SO1, SO3 and SO4) of WFP Country Strategic Plan: children in remote areas have sustained access to food (SO1), building sustainable livelihood opportunities for higher resilience to climatic shocks (SO3), and capacity building to strengthen institutions of local governance for improved service delivery (SO4).

In terms of gender equality and human rights, the universal coverage of the program ensured no girl or boy child was left out of the scheme of school meals, and both women and men smallholder farmers from intervention villages were trained on technical aspects related to soil improvement, multi-cycle cropping, etc. and provided with seeds and manual tools.

Effectiveness

Overall, the program aimed at benefitting 5000 individuals (4500 students and 500 farmers) directly. The actual achievement increased from a little less than 80 per cent in year 1 (3936 individuals) to almost 100 per cent in year 2 (4973 individuals). About 48 per cent of the beneficiaries were women. As for the indirect beneficiaries,3 the program achieved the target number of 25,000 persons in year 2.

On average, a total of 10 farmers4 per village were trained on nutrition-sensitive agriculture, reaching a total of 460 (265 males; 195 females) and 474 farmers (200 males; 274 females) in semesters I and II respectively. Interactions with these farmers revealed that the training sessions have resulted in an increase in their knowledge levels around agriculture.

In terms of inputs, the program provided 11 types of seeds and manual agricultural tools such as sickles, manual water sprinklers and water buckets in year 1 for carrying out cultivation. Year 2 saw the provision of greenhouse plastic sheets, water pumps and piped water connections for farmers cultivating vegetables across 10 model villages.

Trained farmer groups in 19 villages got into formal partnerships with schools in year 1 and began selling vegetables for school meals. In the second year, the program changed its strategy and worked with only 10 model villages. The program created and strengthened farmer groups, enabling them to focus on a diversified set of vegetables all-year round with the help of greenhouse techniques.

The LRP program helped increase the variety of vegetables cultivated by farmers in the intervention villages from four varieties before the start of LRP to 20 varieties by year 2.

About 39 per cent of all trained farmers (184 in number) in year 1 managed to sell their vegetables, achieving more than 70 per cent of the total sales (in value) target. As the number of farmers in the market increased, the demand for vegetables reduced, resulting in lower prices, which affected the value of sales.

Availability of a variety of vegetables also impacted dietary diversity, with the Dietary Diversity Score (DDS) increasing from 4 to 8 in the lowland region, 7 to 8 in the mountainous region, and dropping marginally from 8 to 7 in the upland region.

Efficiency

Leveraging farmer groups, which were formed with help from VEDCs, was an efficient strategy as it enabled an exchange of knowledge, seeds and tools, as well as planning around the production of different types of vegetables.

MAF officials have been trained, and along with WFP Monitoring Assistants, are currently providing technical support. Post exit of WFP, the officials will continue to help farmers practise improved agricultural techniques.

WFP designed a specific monitoring tool in KOBO (mobile/tablet-based monitoring data collection application) to track the project implementation process and the planned outputs. However, it was not regularly used during the two years of intervention.

After year 1, the LRP farmers did not experience a substantial increase in incomes as a result of cultivating vegetables and hence showed lukewarm interest. The geographical scope of the program, therefore, was limited to 10 villages in year 2, resulting in unutilised funds (about 37 per cent), which was utilised in additional 29 LRP villages by entering into a partnership with the Lutheran World Federation.

Sustainability

Linking farmers with the school resulted in ownership among community members towards school meals.

Lack of market access and no substantial increase in income might affect sustained program participation in the future.

Impact

Given that the activities for the two-year program only ended in October 2019, it was too early to capture and assess the true impact of the program.

The LRP program successfully built capacities of small landholder farmers for growing nutritious vegetables. In many cases, it was observed that the farmers contributed vegetables to the schools free of cost. In such instances, the 800 kips was used to procure meat for school meals.

In 14 out of 15 sampled intervention schools, the school meals continued uninterrupted despite the absence of food supply under USDA-SMP for the Sep’19-Mar’20 semester.

Discussions with schoolchildren indicated that on an average they consumed non-vegetarian meals three times per week. Improvement in the ability to concentrate in class and learning outcomes post SMP and LRP was reported by officials, teachers and parents.

As an unintended impact of the program, transfer of technical knowledge from the beneficiary farmers to non-beneficiary ones was reported, which resulted in the cultivation of similar vegetables by most farmers.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Overall, the WFP LRP program has been able to achieve its intended outcomes for year 1 and has been flexible enough to adopt changes as per the community needs for year 2. Conclusions drawn in terms of good practices, lessons learnt and recommendations are presented below.

The program design enabled the community to move towards self-sufficiency in supplying vegetables and ensuring access to nutritious food for children. The program identified and tackled both demand- and supply-side issues.

The collectivisation of farmers at the village level resulted in the transmission of technical knowledge and the sharing of seeds and tools.

Lack of access to markets made it difficult for the farmers to sell their produce, resulting in only a nominal increase in income levels.

The program lacked provisions to ensure women’s participation in leadership and decision-making roles.

Good practice

The program adopted the approach of collaborating with multiple stakeholders. Its success can be primarily attributed to the fact that the demand (community) and supply (government) sides were brought together under the program.

Working with the farmer groups helped in building a sense of camaraderie among all farmers, enabling them to share knowledge and resources, as well as plan the farming of vegetables. Capacity building of LRP farmers resulted in increased technical knowledge, which was also transmitted among farmers from the control group.

Lessons Learned

A needs assessment study is essential during the design stage as it helps understand the needs and aspirations of each region and accordingly customise the intervention.

Any such program in the future must consider (1) educating farmers about the demand and supply aspects and (2) bringing all of them on one platform to plan the potential vegetable production, keeping in mind the demand and supply constraints. While it is understood that sometimes it is imperative to make alterations to the original program design, the changes must be in sync with the initial idea of the program. A strong monitoring system provides a ready reference to the monitoring data and enables (i) quick checks to assess the direction of program movement and (ii) quick turnarounds by the program as a response to issues identified.

The key recommendations are presented in the table below:

Sl. No. |

Recommendations |

Proposed actions |

MAF & DAFO |

||

|

|

Providing technical support for small land farming |

There is a need to organise training on aspects such as regenerating seeds or building resilience to climate change. Creating a yearly calendar for such training and follow-up sessions would ensure high participation from farmers. |

|

|

Providing farmer groups with technology for self-monitoring |

MAF should create a self-monitoring system for farmer groups, encouraging them to record and share details pertaining to the types and quantities of vegetables cultivated with DAFO. |

|

|

Formalisation of farmer groups |

In order to ensure the sustainability of farmer groups, it is essential that MAF formalises them by creating formal structures, ensuring regular meetings, selecting position holders, and delineating their roles and responsibilities. |

|

|

Dashboard for DAFO to analyse monitoring data and take corrective actions |

There is a need to create a strong monitoring system, with a dashboard for DAFO officials, enabling them to identify issues and make timely corrections. |

Farmers |

||

|

|

Monitoring of the vegetables grown and quantity produced |

MAF should create a self-monitoring system for farmer groups, encouraging them to record details pertaining to the types and quantities of vegetables cultivated. Access to real-time data would enable DAFO to carry out immediate corrective actions. |

WFP |

||

|

|

Technological support for program monitoring |

Given WFP’s experience of the LRP program, it can provide technical support to MAF and DAFO in creating a monitoring system and linking it with the dashboard to capture critical information on a real-time basis. |

|

|

Need for a feasibility study for market accessibility and community needs |

WFP should plan a needs assessment study before designing a similar program. The needs assessment study would capture first-hand information on variations that exist across regions, social groups, gender, livelihoods, skills, etc. |

|

|

Ensuring more meaningful engagement with women |

Both women and men should be encouraged to volunteer for SMP activities, which would help in reducing women’s workload. At the same time, it is essential to ensure that women farmers are necessarily included in exposure visits and provided with opportunities to lead farmer groups. |

Introduction

Overview of the Evaluation

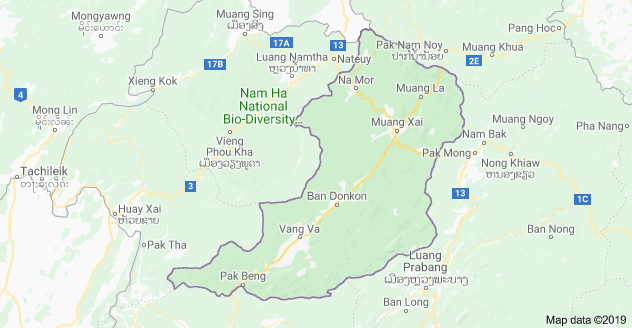

The activity evaluation for the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) supported Local Regional Procurement (LRP) program5 at Nalae district, of Luang Namtha province (details in Annex A), in Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR), commissioned by the WFP country office (WFP CO) of Lao PDR, was carried out during June-November 2019 (mission schedule presented in Annex B). The evaluation covers the period from April 2017 till June 2019. As per the USDA requirement, the LRP program design included an activity evaluation to critically evaluate its implementation and performance with a view to generating recommendations that will enable replications in other geographic areas.

Specific objectives: Underpinned by the dual and mutually reinforcing objectives of accountability and learning, this evaluation had the following specific objectives: assess and report on (1) the performance of the implementation, (2) reasons for success and failure of activities, (3) relevance and effectiveness of capacity strengthening and linking to the School Meals Program (SMP), and (4) contribution towards meeting the food security and nutrition needs of women, men, girls and boys.

Scope of the evaluation (details in Annex C): The evaluation of the LRP program involved three key activities: (1) review of relevant documents including project documents, internal/external administrative records and primary data, (2) visiting LRP project sites in Nalae district to conduct primary data collection, and (3) interacting with representatives and staff members of governmental implementing partners. The geographic scope for the evaluation included 47 villages of Nalae district within Luang Namtha province.

Stakeholders in the evaluation: A number of internal and external stakeholders have an interest in the results of the evaluation. They include: (1) WFP CO, (2) USDA, (3) Regional Bureau Bangkok (RBB), (4) WFP Headquarters Office of Evaluation (OEV), and (5) the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF) and Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES), Government of Lao PDR (GoL), and their respective departments at provincial and district levels.

Primary users of the report (details in Annex D): The primary users of this evaluation will be: (1) WFP CO for decision-making, notably related to program design and implementation; (2) USDA as funder of the project and the evaluation; (3) RBB in order to provide strategic guidance, program support and oversight; (4) WFP HQ for wider organisational learning and accountability; (5) OEV for evaluation syntheses; and (6) MAF and MoES, which will utilise the evaluation findings as inputs for its strategy post handing over of the schools.

The Subject of the Evaluation

Under the SMP 2017-21, supported by USDA McGovern-Dole, rice, lentils and fortified oil were provided to intervention schools, and the communities were encouraged to voluntarily contribute vegetables and fuelwood for school meals. According to the end-line evaluation of SMP 2014-16, while the first component – the provision of food items for school meals – worked well, voluntary contributions from the communities were rare and irregular. As a result, there was a felt need to accentuate the importance of vegetables in school meals by encouraging and facilitating communities to produce different kinds of vegetables through agricultural extension, and ensuring a sustained supply of vegetables to schools.

This led to the conceptualisation of the Local Regional Procurement (LRP) program, which was implemented across 47 villages of Nalae district in Luang Namtha province as a pilot program (results framework presented in Annex H). The activities under the LRP program were envisioned to supplement SMP, and hence were implemented only in schools receiving benefits under SMP. LRP’s key strategic objective (SO1) was to ensure improved effectiveness of food assistance through local and regional procurement for school meals as well as for the community, including parents and farmers (logical framework presented in Annex J). The LRP program provided cash support of 800 kips per student per day to schools for purchasing vegetables from the LRP supported farmers.

Figure 1: The SMP-LRP linkage

The

key activities supported by the program included: (1)

training for VEDC members; (2) training for farmers; (3) training on

cooking and management with support from the Lao Women Union (LWU);

and (4) partner monitoring and exchange visits for farmers (details

of activities presented in Annex E).

The program also envisaged

close coordination between MAF and MoES with MAF providing support

for the preservation of seeds for

future crop cycles and plantings, and MoES incorporating the crops

planted within the community into the Nutrition

and School Agriculture

curriculum. The relation between

SMP and LRP program is presented in

Figure 1.

The

key activities supported by the program included: (1)

training for VEDC members; (2) training for farmers; (3) training on

cooking and management with support from the Lao Women Union (LWU);

and (4) partner monitoring and exchange visits for farmers (details

of activities presented in Annex E).

The program also envisaged

close coordination between MAF and MoES with MAF providing support

for the preservation of seeds for

future crop cycles and plantings, and MoES incorporating the crops

planted within the community into the Nutrition

and School Agriculture

curriculum. The relation between

SMP and LRP program is presented in

Figure 1.Broadly speaking, the LRP program was based on two pillars: (1) supporting school meals for children by way of sustained supply of vegetables and (2) increasing household income by strengthening sustainable farming and establishing requisite commercial linkages. While the first pillar was largely concerned with encouraging farmers to cultivate vegetables and supply a portion of the farm produce to schools for meals, the second pillar aimed at increasing household income by linking farmers with the market for enhancing commercial activities.

Inputs for the program included technical training for cultivating vegetables and provision of vegetable seeds and essential manual tools such as water buckets and sprinklers. The program strategy, however, saw a major shift in the second year. While all 47 villages continued to grow vegetables and contribute to the school meals, only 106 of them expressed interest in cultivating vegetables with a commercial outlook. As a result, these 10 villages – termed ‘model’ villages – experienced intense interventions in year 2, directed towards enhancing the commercial aspects of the cultivation of vegetables. Interventions for the model villages included training farmers to process raw vegetables,7 and provision of greenhouse plastic sheets, water pumps and piped water connections to increase productivity and crop cycles. The remaining 37 (non-model) villages received seeds and manual agricultural tools in year 1, apart from technical training related to the cultivation of vegetables. No additional support was provided to these villages from the second year onwards. As a result, farmers in these villages were not able to sell their produce in markets, though they continued to cultivate vegetables and contribute a portion of these towards school meals.

The savings in the program budget as a result of the reduced scope of work was subsequently used to carry out an additional set of activities with support from the Lutheran World Federation (LWF). The component involved provision of (1) cash support to weavers for purchasing weaving tools, in 12 villages, (2) manual tractors for tilling land, in 10 villages, (3) domesticated animals like goat, sheep, pigs, cow and buffalo, in 15 villages, and (4) big cement stoves for schools, in 29 schools. The intervention with LWF was carried out for a period of four months between July and October 2019. It is important to note that support provided under this component was not aligned to the original LRP program activities despite the fact that it intended to enhance the income of the beneficiaries. The component with LWF was largely carried out with farmers having enough resources and the ability to generate incremental income from the provision of assets. Given that the primary data collection for the evaluation was carried out in September-October 2019, it was not possible to observe and measure the effects generated as a result of involving LWF in the program during July–October 2019.

Table 1: Snapshot of Program Subject

Sl. No. |

Subjects |

USDA LRP |

1 |

WFP contribution |

|

2 |

Main activities |

WFP assistance from April 2017 up to February 2019 consisted of:

|

3 |

Number of villages |

49 villages8 |

4 |

Type of beneficiaries in Nalae |

|

4 |

Number of beneficiaries |

|

Program geography: WFP CO, together with MAF and MoES, implemented the USDA LRP program in Nalae district of Luang Namtha across 47 targeted villages, covering 47 schools, between January 2017 and June 2019 (map of intervention area presented in Annex F). The program was originally initiated in a total of 49 villages; the number was subsequently brought down to 47 by the second semester since two villages fell within a dam construction site.

Program timeline: GoL has been receiving USDA support for SMP since 2008. The current SMP (2017-21) is being implemented in 31 select districts across eight provinces9 characterised by poverty, malnutrition and low literacy rates. The agreement between WFP CO of Lao PDR and USDA for the LRP program was signed in January 2017. Project implementation started in April 2017 and closed on 30 June 2019.

Planned outputs and beneficiaries: The LRP program was implemented across 47 villages and 47 schools of Nalae district, covering almost 500 women and men smallholder farmers and more than 3500 schoolchildren. Essentially, the program targeted 12 per cent of the smallholder farmers and 100 per cent of the children in these 47 villages/schools. A snapshot of all the targeted beneficiaries, as detailed in the ToR, has been provided in Annex F.

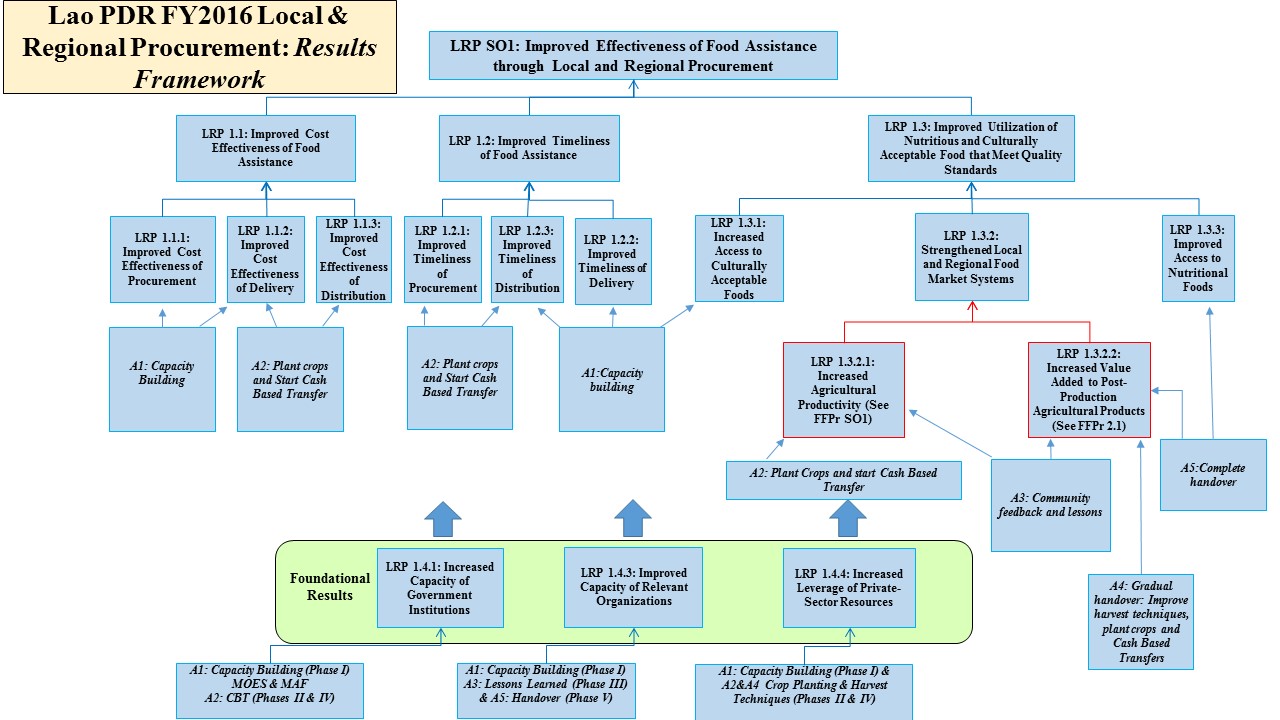

Planned outcomes: The ultimate strategic outcome of the LRP program was to achieve ‘Improved Effectiveness of Food Assistance through Local & Regional Procurement’. The three outcomes targeted by the program were: (i) improved cost-effectiveness of food assistance, (ii) improved timeliness of food assistance, and (iii) improved utilisation of nutritious and culturally acceptable food that meets quality standards. Details of the planned outcomes have been provided in Annex G. The performance indicators and the results framework provided in the evaluation ToR document (Annex H). For each of the outcomes, output indicators and activities have been listed in the planned outcomes matrix. The outputs and results targeted and achieved as per the semi-annual report have also been mapped for each outcome.

Program financing: The program was initially envisaged to cover two districts of Luang Namtha province (Nalae and Vieng Phoukha) with a proposed budget of about USD 1.9 million. However, USDA allocated a little below USD 1 million as financial assistance through LRP 439-2016/020-00 for FY2017/2018. As a result, LRP was implemented only in Nalae district. A break-up of the activity-wise budget (for both districts) is provided in Annex I.

Logical framework: The USDA LRP project’s strategic objective was aligned to and drawn from WFP Lao PDR’s SMP, with LRP SO1 focused on improved effectiveness of food assistance. The activities under the LRP program were directed towards achieving the outcomes stated in the logical framework. A table highlighting the outcomes, outputs and activities is presented in Annex J. The logical framework was comprised of outcomes and foundational results. The foundational results focused on building a conducive environment for the sustainability of the program, including capacity building of the government and other stakeholders. The three outcomes took care of the supply and demand aspects. From the supply side, they ensured improved cost-effectiveness and availability as well as the quality of food. As for the demand aspect, the program focused on improved utilisation of nutritious food by establishing market linkages and building knowledge among stakeholders about the consumption of nutritious food.

Partners: LRP in Nalae district was carried out in partnership with different government departments and local partners. Details of the roles of key partners mentioned below are presented in Annex K.

Government partners: Department of Technical Extension and Agro-Processing (DTEAP) under Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF), Provincial Agriculture and Forestry Office (PAFO), District Agriculture and Forestry Office (DAFO), Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES), Provincial Education and Sports Services (PESS), and District Education and Sports Bureau (DESB)

Others: Village Education and Development Committees (VEDCs)

Gender dimensions of the intervention: Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women (GEEW) and accountability to affected populations are part of the guiding principles of WFP’s action to achieve zero hunger and empowerment of women and other vulnerable groups. The evaluation is guided by WFP’s latest Gender Policy 2015-20. GEEW formed a key aspect of the LRP program and had been mainstreamed in the program design through its focus on one of the most disadvantaged regions of the country. While the program at the broader level targeted smallholder farmers in the region, the very nature of the community and the secondary status of women therein ensured that women formed a significant proportion of program beneficiaries. This can be seen in the evaluation questions, presented in Annex M, that address the influence of the program in the gender context as also the gender-specific impacts of the program.

WFP is committed to the 2030 Agenda’s global call to action and ensuring the underlying principle of ‘no-one left behind’. The LRP program is underpinned by the same principle and targets the smallholder farmers, including female farmers, in a remote area of the country. Through its support on improved farming techniques, it sought to help the farmers to build farming resilience against climate change and enable to continue supporting the National School Meals Program (NSMP) through the sale of vegetables. The inclusion of female farmers in LRP was directed towards empowering them to decide how to use their land through opportunities for higher earnings and a reliable source of income.

Context

Poverty, food and nutrition security: Lao PDR is one of the fastest-growing economies in East Asia and the Pacific with a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita of USD 6317 in 2018. However, the Human Development Index (HDI) 201910 ranks the country at 140 out of 189 countries. The Human Development Report 2019 designated 23.1 per cent of the population as multi-dimensionally poor; an additional 21.2 per cent live near multidimensional poverty. Nalae is a remote district inhabited by the ethnic Khmu community in the highland areas of Luang Namtha province, where around a quarter (28 per cent) of the population lives below the poverty line, which is higher than the national average.

According to the 2015 report of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), the Global Hunger Index rates hunger levels for the country as ‘serious’ with Laos ranked 76 out of 104 nations.11 As regards its nutritional status, the country faces a huge challenge of stunting, malnutrition, anaemia and Vitamin A deficiency, as almost one-fifth of the population consumes less than the minimum dietary energy requirements.12 Currently, 21 per cent of children are underweight, while 33 per cent of children are stunted and wasting stands at 9 per cent. Stunting rates in Nalae were higher (39.5 per cent) than the national average. The global nutrition report for Laos13 indicates a difference in stunting and wasting among the under-5 boys and girls.14 While wasting was prevalent among 5.8 per cent girls and 6.9 per cent boys, stunting was prevalent among 42.6 per cent girls and 45.7 per cent boys. Also, with 48.6 per cent under-5 children stunted in the rural areas; the situation is quite grim in comparison to urban areas (27.4 per cent).

Micronutrient deficiencies also affect large parts of the population with IFPRI 2014 reporting the prevalence of anaemia in school-aged children as ‘severe’ and anaemia in pregnant and lactating women (PLW) at 45.3 per cent.15 According to the global nutrition report for Laos, while 29.2 per cent girls in the 5-19 age group were underweight in 2016, the corresponding figure for boys was 35.7 per cent.

Trends related to SDG 2 and SDG 17: Poverty is one of the root causes of malnutrition and hunger in the country. Therefore, Laos has been focusing on meeting the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 – ‘End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture’ – through concentrated efforts and changes in policies.

The key outcome areas identified in the context of Lao PDR to meet SDG 2 include: (1) sustainable food production, improved agricultural productivity and resilient agricultural practices; (2) access for all to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round; (3) improved nutrition of vulnerable groups; and (4) improved management of genetic diversity.16 WFP is supporting the government in achieving SDG 2 through its multiple programs across the country. LRP is one such program that focuses on the nutrition and food security of vulnerable populations residing in remote locations.

WFP is also working towards achieving SDG 17 – ‘Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development’17 – by adopting the approach of building partnerships to work towards common goals. WFP partners with different departments of GoL including their offices at the central, provincial and district levels and other multilateral organisations for the implementation of its programs. Under the LRP program, the focus has been on capacity building of implementing partners, including the government and community organisations, and coordination among them for successful implementation of the program, which is in line with SDG 17.

Health: The under-5 mortality rate (U5MR) in Lao PDR was 67 in 2015. Although there has been a 59 per cent decline in U5MR from 1990, it has fallen short of the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) target for child mortality of 54. According to HDR 2016, poor nutrition causes 45 per cent of the deaths among children under the age of 5 and also leads to stunting and delays in physical development.

Education: While there has been a significant improvement in the status of children’s education in Lao PDR in recent years, females continue to lag behind males. The youth literacy rate amongst females was around 87 per cent, compared to 93 per cent among males (HDR 2016). The difference in literacy is starker among women from ethnic groups; close to 70 per cent of such women were illiterate and suffered further isolation given that few of them spoke the national language.18 The girl/boy ratio in schools in Nalae district which was at 0.98 for primary education, fell to 0.83 in secondary education and subsequently to 0.69 in upper secondary, indicating higher dropouts among girls.19

Agriculture: Lao PDR largely depends on agriculture and farming. However, smaller landholdings, absence of secure land tenures, and limited area under irrigation have led to low domestic food production and availability. Almost 90 per cent of the country’s farmers cultivate rice. This has resulted in a rice-dominated diet that is deficient in proteins, fats and micronutrients, relative to WHO-recommended levels, giving rise to stunting, wasting and other related problems. Due to its topography, Nalae district has been at high risk of natural disasters, such as heavy rainfall and landslides. The households most vulnerable to food insecurity and climatic shocks were those in remote areas with little access to basic infrastructure, those with low engagement in fishing and hunting or unskilled labourers, those practising upland farming on small slopes, women and men with small farmlands, and those without kitchen gardens.20

Government strategy, policies and programs: GoL aims to move from LDC status to that of a middle-income country by 2020. Through the 8th National Socio-Economic Development Plan (NSEDP) 2016-2020 and other policy instruments, the government is striving for sustainable economic growth and equitable social development. NSEDP includes sectoral plans of various departments including the School Meals Action Plan (SMAP) 2016-2020. Complementing this plan is the Agriculture Development Strategy 2025, through which GoL intends to combat malnutrition by promoting dietary diversity. This was drafted with the aim of achieving national food security, providing seed and technical assistance to increase production and quality of products, and ending shift cultivation practices.21 The National Nutrition Strategy to 2025 and Plan of Action 2016-2020 (NNSPA) aims at promoting equality in gender roles, emphasising women’s access to health services, nutrition and food security information, and food

Towards achieving universal access to primary education, GoL has made it free and compulsory. The Education Sector Development Plan (ESDP) 2016-2020 stresses the need to maintain and expand school feeding programs to encourage disadvantaged children (ethnic communities, children with disabilities, those in remote and impoverished circumstances) in lower primary grades to remain in school. In May 2014, GoL adopted the Policy on Promoting School Lunch, which laid the foundation of a nation-wide approach of offering school lunches as an incentive for children in primary school to attend school.

Gender dimensions: Despite playing a significant role in agricultural activities and contributing to economic earnings, women’s contribution still remains undervalued and seems most vulnerable to climatic and social shocks. With a Gender Development Index (GDI)22 value of 0.896, Lao PDR ranked 141 out of 188 countries in 2015.23 In 2016, however, Lao PDR demonstrated advancements with respect to GDI, with the GDI value rising to 0.924.24.

In relation to GEEW, Lao’s Gender Inequality Index ranked 106 out of 159 countries in 2015. In 2016, United Nations confirmed that Laos has one of the highest rates of Child, Early, and Forced Marriages (CEFM) in the region. One-third of women marry before age 18, while one-tenth marry before age 15. Lao PDR is more rural in character than any other country in South East Asia. More than three-quarters of the total population live in rural areas and depend on agriculture and natural resources for survival. Geographical isolation fosters a persistent cultural environment effectively contributing to the continuation of CEFM. A UNPFA report noted that young girls growing up in isolated minority communities that were not integrated into a wider society saw marriage as their only option, partly because they were not aware of other options, and could not speak Lao-Thai, the national language, to effectively communicate with people outside of their isolated community. This shows the important linkages between SDGs 2, 425 and 526.

The grim situation of women and girls is aggravated by cultural beliefs that the role of a woman is to be a wife and a mother, and as a result, parents lacked the motivation to invest in educating their daughters and preparing them for paid work (HDR 2016). Further, formal educational attainment and informally obtained knowledge held particularly by mothers have both been shown to be significantly linked to improved nutrition among their children.27 Cross-country time series, as also studies using natural experiments, have confirmed that maternal education is a key determinant of birth weight, neonatal survival and children’s attained height.

Development assistance: WFP CO of Lao PDR is one of the three main providers of school meals in Laos, along with GoL and Catholic Relief Services (CRS). WF CO and FAO are piloting education material in three WFP-assisted schools in Luang Namtha; WFP and World Bank are piloting the use of clean cookstoves that reduce smoke exposure and the risk of lung disease. UNICEF’s WASH program has supported close to 100 schools targeted by WFP for its school lunch program.

WFP’s portfolio in Laos is aligned to the development agenda laid out in the 8th NSEDP and United Nations Partnership Framework 2017-2021. WFP’s Country Strategic Plan 2017-2021 supports GoL in its National Nutritional Strategy and Agriculture Development Strategy through the provision of sustainable access to food for schoolchildren by 2021, reducing stunting rates among children to meet national targets by 2025, increasing the climate resilience of vulnerable households against seasonal and long-term stresses, and strengthening national and local governance institutions to improve service delivery.

WFP, together with MAF and MoES and other partners, has implemented the USDA LRP program in Nalae district of Luang Namtha since 2017. Technical assistance was provided to the farming communities of 47 villages for practising improved agricultural techniques and supporting SMP that was being implemented in the village schools. While MAF was expected to provide guidance on the diversity and quantity of seeds or cuttings required and on the procurement of such items, MoES was entrusted the role of incorporating the crops planted in the communities into the Nutrition and School Agriculture curriculum.

Evaluation Methodology

The activity evaluation of the pilot LRP program was conducted between July and November 2019. The evaluation team undertook a five-day scoping mission from 29 July to 2 August 2019 to obtain a better understanding of the project and finalise the evaluation approach and methodology, in consultation with the WFP CO of Lao PDR (scoping report presented in Annex L). The data collection phase took place in the National Capital Vientiane, province headquarters Luang Namtha and Nalae district, between 16 September and 2 October 2019. The period aligned with the reopening of schools after the semester break. (Mission Schedule presented in Annex B). The scope of the evaluation for the LRP program was the period April 2017 till June 2019.

Evaluation Questions and Criteria

The evaluation was in concurrence with the ToR and used the OECD-DAC criteria to assess the relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability of the LRP program. Overall, 20 evaluation questions (EQs) across these five criteria were framed to assess the program.

Relevance: Alignment with and contribution of the program to government strategies (EQ1); the extent to which the program design and implementation contribute to capacitating the smallholder farmers and linking them to markets (EQ2); the program’s contribution to enhancing farmers’ ability to provide diverse and nutritious food to SMP (EQ3); and the program’s contribution to gender equality and empowerment of the vulnerable farmers (EQ4).

Effectiveness: Assessing the reasons for achievement or non-achievement of program targets (EQ5); measuring the extent to which the program enhanced smallholder farmers’ contribution to school meals (EQ6); judging the contribution of the program towards gender equality and empowerment (EQ7); and assessing its contribution to improving dietary diversity (EQ8). Efficiency: Adequacy, sufficiency and timeliness of support provided by DTEAP, PAFO and DAFO for solving implementation issues (EQ9&11); efficiency of farmer groups in utilising the technical support for agriculture (EQ10); and flexibility and adaptability of the program to respond to the need for course corrections (EQ12).

Impact: The effects of LRP activities on SMP (EQ13); the intended and unintended effects on direct and indirect beneficiaries (EQ14); and the use of new agricultural techniques and knowledge (EQ15). Sustainability: Capacity building of farmers, MAF officials and other partners (EQ17); increased ownership of community-driven school lunches (EQ18); additional aspects for sustaining the LRP program (EQ19); and necessary factors for replicating the program (EQ20).

Further, the design and implementation of the program were also assessed using the lens of equality and inclusivity. Each of the five evaluation criteria has been analysed in detail, and the prerequisite factors vital for the LRP program to succeed were identified, along with the learnings to scale up the program in other geographies. For detailed information on evaluation questions and criteria, the Evaluation Matrix is attached as Annex M.

Approach and Methodology

The evaluation provided an evidence-based performance assessment of the activities and outcomes under the program’s results framework. For this purpose, the Logic model, which provided logical linkages across program resources, activities, outputs and outcomes, was used to measure the effectiveness of the program. The technical approach to the end-line evaluation study has been illustrated in the form of a figure in Annex N.

The activity evaluation followed a quasi-experimental evaluation design that covered the study of LRP-supported (intervention) as also non-supported (control) villages and schools. The methodology entailed secondary research as well as primary data collection. A mixed-method approach was deployed to answer the questions using key informant interviews (KIIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) for both qualitative and quantitative data. The evaluation design also included Most Significant Change (MSC), which involved the identification and documentation of seven case studies (Annex U) in the intervention villages, highlighting personal accounts of change of farmers who participated in the LRP program. During the field visits, the evaluation team identified individuals or households which had experienced substantial changes as a result of participating in the program and documented the process of such change in detail.

Sampling frame

In accordance with the requirements of the ToR, the sampling approach adopted for both the quantitative and qualitative components for the end-line evaluation was similar to the one deployed during the baseline. The approach involved systematic random sampling for a selection of villages, broken down into lowland (0-500 metres above sea level), upland (500-100 metres above sea level), and mountainous regions (more than 1000 metres above sea level),28 in the proportion of the actual number of intervention villages within each of the three strata.

The sample size and respondent groups for the current study were increased over the baseline and re-established. This was done in order to effectively capture the overall effect of the program as also for the adequate representation of the diversity that exists among program villages. The quantitative sample size covered under the end-line evaluation was calculated at the program level, using the ‘differences method’ formula with a finite population.29 A table providing the distribution of samples across different target groups for the quantitative and qualitative components is included in Annex N.

Data Collection Methods

Other than the secondary literature review, the evaluation used semi-structured questionnaires containing a mix of quantitative and qualitative questions for interviews and group discussions with parents and smallholder farmers for primary data collection. A tool containing multiple-choice questions was administered for children of 5-10 years from classes III-V of the schools in the villages. Discussion guides were used for carrying out FDGs (with VEDC members) and KIIs (with school heads, teachers, cooks, traders, WFP staff, NGO partners and government staff). The list of stakeholders met is presented in Annex O and data collection tools are presented in Annex S.

Data from secondary research (documents gathered are presented in Annex P) and different respondent categories within the primary data collection component was triangulated. The evaluation matrix in Annex M presents different sources from where the data for evaluation questions was collected, along with the corresponding methods employed for carrying out data analysis.

Data Analysis Methods

Given that the evaluation was primarily qualitative in nature, in addition to the comparison between intervention and control villages, the focus was essentially on explaining the reason(s) behind the achievement or non-achievement of key performance indicators.

The evaluation study included the use of qualitative research tools such as the H-form tool and Most Significant Change. Qualitative data was translated into English, checked by the evaluation team for consistency based on the field visits, and subsequently analysed using content analysis. Quantitative data was cleaned for ensuring basic consistency and, subsequently, tabulated.

Integration of Gender into the Methodology

The evaluation integrated gender dimensions into its design. It examined the role and nature of the participation of men and women in the program, specifically through VEDCs and farmer groups. The evaluation matrix presented in Annex M highlights that gender was an integral theme for a number of evaluation questions, along with a focus on other vulnerable groups. Question 4, under the relevance criterion, captures the extent to which the program was in line with the needs of women and men smallholder farmers, and whether the program was based on sound gender analysis. Under the effectiveness criterion, question 7 captures the extent to which women and men smallholder farmers benefitted from the program activities. Under the impact criterion, question 14 focuses on the intended and unintended effects of the program on men and women smallholder farmers.

The data collection team was adequately trained to ensure that views of all diverse groups were considered, reflected upon and triangulated, with specific attention to issues revolving around gender. The data collection team was gender-balanced, with three male and three female enumerators, all of whom were fluent in the Lao language. The core evaluation team also had an equal number (two each) of male and female members. To the extent possible, participants for group discussions included both men and women in equal numbers; questions to assess their views on gender issues were included in the checklist.

Validation Exercise

With the objective of validating findings of the LRP evaluation and aiding cross-learning among stakeholders (WFP, MAF and MoES, VEDC members and farmers), validation workshops were conducted in Nalae district and Vientiane.30 The workshops were aimed at triggering discussions, particularly around feedback on the program and key recommendations for designing and implementing a similar program in future.

T

he

workshop in Nalae district was attended by MAF and DAFO

officials, WFP representatives, VEDC members and farmers. Post the

presentation on the evaluation findings, five groups were created

for further discussion. Each group discussed (1) what worked well

with LRP; (2) what needed improvement; (3) how each group can ensure

these improvements, and (4) what support each group would require

from others in order to carry out these improvements.

he

workshop in Nalae district was attended by MAF and DAFO

officials, WFP representatives, VEDC members and farmers. Post the

presentation on the evaluation findings, five groups were created

for further discussion. Each group discussed (1) what worked well

with LRP; (2) what needed improvement; (3) how each group can ensure

these improvements, and (4) what support each group would require

from others in order to carry out these improvements.

Figure 2: Visual thinking for validating results

In Vientiane, the workshop was attended by officials from WFP and USDA. In addition to the discussion on the findings of LRP, the participants specifically discussed: (1) key inferences they drew from the evaluation and the visual thinking exercise, and (2) recommendations for designing and implementing a similar program in future.

Ethical Considerations and Quality Assurance

With its rich experience of working with UN agencies including WFP, NRMC has a deep understanding of the United Nations Evaluation Group (UNEG) norms, standards and ethical guidelines. Further, NRMC’s internal quality protocols were integrated with the process for information collection, collation, analysis and delivery.

The evaluation was particularly conscious of maintaining ethical norms with respect to data collection and its reporting. In addition to providing the option to the respondent to participate in the study, proper informed consent was taken before initiating any discussion. Prior consent was taken from the school heads/teachers before interacting with children in schools. Extreme care was taken while interacting with children, ensuring no mental or physical harm or loss to them during or after the interaction. Similarly, at the time of reporting, the evaluation team ensured that the names of the respondents were not disclosed in the evaluation report, which could potentially lead to their recognition.

The data collection team consisted of Lao-based personnel who were well versed with the local language and had prior experience of collecting and collating field-level information. A gender-balanced team was deployed to gather the perspectives of boys, girls, men and women. Separate teams were deployed for quantitative and qualitative surveys. Discussions with government officials, WFP field teams, and partners were conducted by the NRMC core team.

A two-day training session on field ethics and data collection tools was conducted for enumerators by the NRMC core evaluation team. The team was provided with translated tools to overcome language barriers.

As part of quality control as also to ensure timeliness of data collection, NRMC developed detailed field movement plans prior to the survey. A daily team movement plan was shared well in advance with the team. At least two of the core evaluation team from NRMC were present in the field during the entire period of data collection, accompanying qualitative and quantitative interviewers.

An internal team within NRMC reviewed the draft evaluation report before it was shared with WFP. The exercise ensured that the report covered all the evaluation objectives and answered all evaluation questions, following the prescribed research methodology. The final report has been edited by an external editor before it has been shared with WFP.

Limitations and Risks

While the evaluation made comparisons between case and control groups, it did not capture information pertaining to other interventions carried out in evaluation villages, and hence cannot attribute any changes to the program. The activity evaluation was quasi-experimental, and hence can only comment on the contributions made, without attributing any changes to the program. However, primarily using qualitative data, the evaluation sought to understand and explain the manner in which the program influenced the observed results as highlighted in the evaluation questions.

The two key objectives of the baseline study included understanding the agricultural practices adopted by farmers and the impact of the location of a village on their agricultural practices. While analysing key components of the first aspect, it emerged that the baseline study analysed data at the geographical strata (lowland, upland and mountains)31 and individual village levels. The end-line study, however, presents findings at program and strata levels, and not for each village individually.

Children in standards I-II were unable to comprehend and respond to the questions and hence were not included for data collection. As a result, the children’s tool was administered for children in standards III-V. The total number of children in a few schools was much lower than the minimum sample required for per school (27), which affected the total sample size achieved.

It is noteworthy that the program intervened with only 10 farmers within each intervention village. As a result, the end-line data collection adopted a census approach, involving all intervention farmers for the FGDs. However, it was observed that in a number of cases, certain farmers (and parents) would either shift to the uplands for paddy cultivation or move to the fields early in the morning, and hence could not be contacted. As a result, while the number of FGDs remained as planned, there was a slight shortfall in the number of individuals covered in such discussions. As mentioned earlier, the evaluation was primarily qualitative in nature, putting a major focus on explaining the reason(s) behind the achievement or non-achievement of key performance indicators. Since the number of qualitative activities and discussions remains unchanged, we believe the shortfall in individuals would not have any implication on the findings.

The performance matrix shows that the number of indirect beneficiaries was computed by multiplying the number of direct beneficiaries by 5. This approach was based on the assumption that every beneficiary reached would also have transferred benefits of the program to his/her family members. However, the approach failed to identify overlaps in the form of children and farmers belonging to the same households, or two siblings belonging to the same household. As a result, this approach of estimating indirect beneficiaries may have amounted to multiple counting of certain indirect beneficiaries, and therefore would have inflated the total figure. Also, it was not possible to determine the male-female ratio among the indirect beneficiaries.

While WFP had designed a specific monitoring tool in KOBO to track the project implementation process and its planned outputs, it was not regularly used during the two years of intervention. The absence of robust monitoring by WFP CO/implementing partner as also of financial data has impeded comprehensive and detailed analysis affecting the evaluation outcomes specifically for measuring effectiveness and efficiency.

The time frame for partnership with the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) was beyond the scope of this evaluation, and hence the evaluation could not evaluate the outcomes achieved as a result of this partnership. The evaluation can, therefore, only comment at a conceptual level on the idea of this intervention, but cannot assess the manner in which the intervention has been received by the community and the nature of impact thus created.

In accordance with the ToR, evaluation design included an assessment of the impact of the program. However, it was realised that it was too early to capture the true impact of the program, as the two-year program had recently ended, in June 2019. Hence, the evaluation results indicate more short-term changes.

Evaluation Findings

Relevance of LRP

The key evaluation questions (EQs) presented in Annex M were the foundation for assessing the LRP program. This section focuses on questions pertaining to the relevance of the program and includes: (i) alignment with and contribution of the program to government strategies (EQ1); (ii) the extent to which the program design and implementation contribute to capacitating the smallholder farmers and linking them to markets (EQ2); (iii) the program’s contribution to enhancing farmers’ ability to contribute diverse and nutritious food to SMP (EQ3); and (iv) the program’s contribution to gender equality and empowerment of the vulnerable farmers (EQ4).

Alignment and Contribution to Government Strategies

The LRP program 2017-2019 cohered with the national priorities around agriculture, nutrition and education. GoL has been combating malnutrition by promoting dietary diversity at household, school and community levels through the implementation of the School Meals Action Plan (SMAP) 2016-2020 and Agriculture Development Strategy to 2025 and Vision to the Year 2030. Annex Q highlights components within the national Agriculture Development Strategy and Nutrition Development Strategy as also the National Education Promotion Policy that were in synchronisation with the logical framework of the program.

MoES has identified Home Grown School Feeding (HGSF) as the future strategy for supporting SMP. HGSF aims to provide students with food produced and purchased within the country to the maximum extent possible. It is increasingly being endorsed by governments and organisations for its potential benefits to education, nutrition and agricultural production through the generation of a consistent local market demand.

Aligned with National School meals Program (NSMP), the LRP program also provisioned for 800 kips per student per day as cash transfer to schools for purchasing vegetables. It was expected that the availability of cash would enable schools to overcome any financial barriers that may have prevented purchase of vegetables resulting in non-cooking of school lunches. Also, by supporting farmers with technical knowledge and supporting the schools financially, the program identified and tackled both the demand and supply issues as prescribed under NSMP. The piloting of LRP at Nalae has supported schools in the district for a smooth transition to the national program. By establishing the partnership mechanism between schools and farmer groups, it has ensured the continuity of school meals under NSMP.

The LRP program was in line with the priorities stated in the Agriculture Development Strategy to 2025 and Vision to the Year 2030 strategy document by way of investments to increase multiple crop agricultural practices and diversify food products to achieve food security. The program design included building public-private partnerships between government departments, program staff and farmers, involving the capacity building of all relevant stakeholders, including provincial- and district-level government officials to achieve sustained outcomes from the program. Detailed analysis showcasing the linkage between the LRP program and the strategy document is elucidated in Annex Q.

The LRP program was aligned with the National Nutrition Strategy (NNS) to 2025 and Plan of Action 2016-2020 strategy, and was underpinned by inter-sectoral coordination involving WFP CO, MoES and MAF for ensuring capacity building of government officials and farmers to promote improved nutrition in school meals. NNS defines nutrition through the prism of gender, highlighting access to health and nutrition equally by girls, boys, women and men, and ensuring the participation of women and men in decision-making across levels.32

The Education Sector Development Plan 2016-2020 states that the provision of school meals can help in reducing dropouts and improving retention in schools in lower grades.33 SMP is primarily aligned with the government objectives of reducing dropouts as also improving learning outcomes by way of provision of school meals. The LRP program supported the sustainability of SMP by ensuring regular supply of locally grown fresh and nutritious vegetables for school meals, and hence was in alignment with the government plan.

MoES is the nodal agency for the implementation of nation-wide school meals in Laos. It has set up an Inclusive Education Centre (IEC) unit for oversight and scaling up of the National School Meals Program (NSMP). WFP CO closely coordinated with MoES to implement the LRP program. The LRP program design required close coordination between MAF and MoES. While it was envisaged that MAF would extend support through training on cultivation of vegetables required for meeting the nutritional needs of the schoolchildren, MoES was responsible for incorporating the crops planted in the community into the Nutrition and School Agriculture curriculum.

Coherence with WFP Country Program (2017-2021)

The WFP Country Strategic Plan for Lao PDR 2017-2021,34 drafted in consultation with GoL, envisions the full handover of school meal activities to local communities by 2021. For the successful implementation of the plan, building institutional capacity at the central and sub-national levels together with the government ensured strengthened capabilities to assume ownership at the community level. The LRP program’s cash support enables the school management to decide on the spending mechanism and thus are in a position to receive cash support under NSMP. Simultaneously, it also supported in building the capacities of the farmers for selling variety of vegetables throughout the year to schools.

Capacitating Smallholder Farmers and DAFO Officials

The USDA-supported SMP FY14-16 end-line evaluation had highlighted non-availability of vegetables as a critical barrier to the smooth implementation of SMP. Students attending school were deprived of the school lunch due to non-availability of vegetables. The problem is aggravated in challenging topographies such as in Nalae where farming is constrained by the terrain and lack of water for irrigation. In addition, over 80 per cent of households in this area are subsistence farmers, growing mainly rice. The tradition of single-crop subsistence farming where households grow rice (and have perhaps planted a small kitchen garden) has led to limited availability of the varied commodities required for a nutritious meal to be prepared through SMP.

Under these circumstances the LRP program aimed at training the smallholder farmers to practise multi-cropping of diverse vegetables and supporting them with seeds and tools. The goal was to enable these households, through the use of improved agricultural techniques, to grow sufficient vegetables in their small land parcels. The diversified products would be sufficient to meet the school requirements and would also facilitate the consumption of nutritious meals at home. The excess produce was to be sold in the open market, which would contribute to the household income.

Figure 3: Vegetable farming using Greenhouse technique

T

he

climatic uncertainties caused by long dry spells followed by heavy

rains constraint farmers from farming throughout the year. To

further support the farmers, they were provided with greenhouse

materials to ensure round-the-year vegetable production. Couple of

farmers from each group were taken for exposure visits where they

learnt from practicing farmers on setting up greenhouses and doing

greenhouse-based farming. These visits have helped the program

farmers and they have been able to grow vegetables throughout the

year. The deputy DAFO stated that due to these exposure visits,

farmers have started demanding for support. This increase in demand

is underpinned by the success achieved by the LRP supported farmers.

he

climatic uncertainties caused by long dry spells followed by heavy

rains constraint farmers from farming throughout the year. To

further support the farmers, they were provided with greenhouse

materials to ensure round-the-year vegetable production. Couple of

farmers from each group were taken for exposure visits where they

learnt from practicing farmers on setting up greenhouses and doing

greenhouse-based farming. These visits have helped the program

farmers and they have been able to grow vegetables throughout the

year. The deputy DAFO stated that due to these exposure visits,

farmers have started demanding for support. This increase in demand

is underpinned by the success achieved by the LRP supported farmers.

The importance of building capacities in the government for making it responsive to the needs of the community is critical for the success of any social safety program. DAFO officials attended training workshops and undertook exposure visits, and in-turn conducted training sessions for smallholder farmers from intervention villages. VEDC, LWU members, teachers, etc. were trained in various components of program implementation, while farmers were trained in modern agricultural practices. The trained officials can now be utilised as trainers for during replication and scaling up of the program.

The program involved government partners to impart onsite training to farmers on modern farming methods, including preparing the land for cultivation, preparing and using compost, growing vegetables, crop rotation etc. and providing seeds. Discussion with farmers indicated that easy access to trained officials had helped them in overcoming farming issues. Also, the officials had supported them to overcome the traditional wrong practices of farming. For e.g. reducing the quantity of seeds along with proper spacing have helped in increasing production with reduced input cost.