0648-0783 Supporting Statement A

0648-0783 Supporting Statement A.docx

Survey To Collect Economic Data From Recreational Anglers Along the Atlantic Coast

OMB: 0648-0783

SUPPORTING STATEMENT

National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration

Survey to Collect Economic Data from Recreational Anglers along the Atlantic Coast

OMB Control No. 0648-0783

Abstract

This request is for a revision to a currently approved information collection. The objective of the original data collection effort under OMB Control Number 0648-0783 was to assess how changes in saltwater recreational fishing regulations affect angler effort, angler welfare, fishing mortality, and future stock levels. That data collection effort focused on anglers who fished for Atlantic cod and haddock off the Atlantic coast from Maine to Massachusetts. Under this revised information collection request, the objective remains the same, but a new survey will be added with the focus on anglers who fish for summer flounder and black sea bass in the North Atlantic coastal states of New York and New Jersey.

Data collected from this survey will improve our ability to understand and predict how changes in management options and regulations may change fishing mortality and the number of trips anglers take for summer flounder and black sea bass. This data will allow fisheries managers to conduct updated and improved analysis of the socio-economic effects of proposed changes in fishing regulations to recreational anglers and to coastal communities. The recreational fishing community and regional fisheries management councils have requested more species-specific socio-economic studies of recreational fishing that can be used in the analysis of fisheries policies. This survey will address that stated need for more species-specific studies. In addition, the survey data will provide the foundation for a Management Strategy Evaluation designed to assess the added economic value to anglers associated with minimizing summer flounder discards. This work will be conducted as part of the Mid-Atlantic Fisheries Management Council’s Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management process.

The survey population consists of those anglers who fish in saltwater in the North Atlantic coastal states of New York and New Jersey and who possess a license to fish. A sample of anglers will be drawn from both state fishing license frames. The survey will be conducted using both mail and email to contact anglers and invite them to take the survey online. Anglers not responding to the online survey will receive a paper survey in the mail.

Justification

Explain the circumstances that make the collection of information necessary. Identify any legal or administrative requirements that necessitate the collection. Attach a copy of the appropriate section of each statute and regulation mandating or authorizing the collection of information.

The Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NEFSC) is sponsoring this project to elicit preferences for anglers targeting summer flounder and black sea bass. Understanding angler preferences is a critical step in determining how fishing regulations affect angler effort, angler welfare, fishing mortality, and future stock levels. The statistical model needed to meet this research objective requires fishing-related and socioeconomic data on users of these fisheries. The most recent available socioeconomic data for recreational summer flounder and black sea bass fishing are over ten years old, so policymakers are being forced to evaluate the economic and biological consequences of summer flounder and black sea bass regulatory actions without a good understanding of how changes in regulations affect angler effort and angler welfare. This has likely led to ineffective regulations that unnecessarily burden anglers, reduce their welfare, and fail to meet the conservation objectives for summer flounder and black sea bass (MAFMC 2013). To collect this information, the NEFSC seeks to implement an updated North Atlantic Recreational Fishing Survey (herein called NARFS II), a questionnaire directed toward recreational anglers who fish for summer flounder and black sea bass off the coasts of New Jersey and New York. National Marine Fisheries Service Marine Recreational Information Program (MRIP) data show about 8 million angler trips targeted summer flounder or black sea bass in 2019 along the Atlantic coast. Of these trips, New Jersey and New York accounted for 51% and 35% of the total, respectively. Thus, about 86% of the total angler trips targeting summer flounder or black sea bass occurred in these two states. To focus efforts on the population of interest and reduce implementation costs we intend to draw survey participants from New York and New Jersey. This is further explained in Part B, Question 2.

Data collected by the NARFS II will be used to estimate angler’s preferences for summer flounder and black sea bass. Building upon our findings from the first NARFS, anglers’ utility will be specified according to α-Maxmin Expected Utility (Gilboa et al. 1989, Ghirardato et al. 2004). This specification nests a von Neumann Morgenstern utility with constant absolute risk aversion (CARA) within the framework of ambiguity and allows for joint estimation of both risk and ambiguity preferences by anglers. Specifically, an agent with α-Maxmin preferences evaluates a choice by considering the weighted average of the worst expected payoff and the best expected payoff with α and 1-α being the two respective weights. The parameter α reflects the agent’s attitude towards ambiguity. This is not a technicality, but rather a potentially important issue because, (i) as anglers in the focus groups conducted in New Jersey stressed, in fishing you never know in advance how many fish you will bring home; luck plays a significant role; and (ii) because many anglers seem to focus primarily on the probability of achieving the extreme outcomes –bringing home zero fish versus filling the cooler up to the bag limit– when deciding whether to go fishing. Thus, policy instruments such as size and bag limits likely impact anglers’ welfare and participation not only through their effect on the expected catch and keep, but more generally through their effect on the probability of achieving different catch outcomes. These effects can only be quantified using data explicitly designed to elicit attitudes towards risk and ambiguity.

More broadly, NARFS II builds upon the methodological lessons we learned from NARFS. Specifically, how to properly convey risk and uncertainty regarding catch distributions in the questionnaire design. During the focus groups in New Jersey, we presented participants with several versions of the questions involving pie charts, that is, uncertain keep. The specification of these questions was informed by Holt and Laury (2002) multiple price lists, as well as recent efforts to convey risky outcomes (e.g. Huber at al. 2010, Harrison 2014, Dimmock et al. 2015). NARFS II focus groups participants found these questions to more realistically reflect the recreational fishing experience, in which variability of the catch is such a salient feature, than the design employed in the first NARFS in which catch outcomes were predetermined and deterministic. In fact, some of the focus groups participants suggested that this feature is what makes recreational fishing appealing to them in the first place. We think this small addition will improve the quality of the preference data collected and the overall survey response rate.

Overall, the survey data and models reliant on such data will inform management decisions of the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council (MAFMC), operating under the authority of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (16 US.C. 1801 et seq.).

Indicate how, by whom, and for what purpose the information is to be used. Except for a new collection, indicate the actual use the agency has made of the information received from the current collection.

The data collected from NARFS II will be used to estimate a model of angler behavior for summer flounder and black sea bass. Modeling results will show the types of policies that will be expected to achieve conservation objectives while simultaneously maximizing the well-being of anglers. Use of the modeling results by the MAFMC will increase the likelihood that summer flounder and black sea bass management policies meet intended conservation objectives because anglers’ preferences and well-being will be explicitly considered.

In addition, in 2019, the MAFMC approved development of a Summer Flounder Conceptual Model to address management questions regarding the highest priority ecosystem factors, in their efforts to move towards implementation of Ecosystem Based Management (EBM) (https://www.mafmc.org/eafm). The priority management question that the MAFMC selected was to “Evaluate the biological and economic benefits of minimizing discards and converting discards into landings in the recreational sector. Identify management strategies to effectively realize these benefits.”

The impetus for development of this model was the northward shift in the summer flounder stock on the Atlantic coast. Bottom trawl resource surveys conducted by NMFS research vessels have shown that the distribution of the summer flounder population has moved northward, due in part to ocean warming, and where the center of the stock was once off the coast of Virginia, it is now off the coasts of New York and New Jersey. This has caused significant conflict over the distribution of resource access and benefits due to a relatively static management context. The FMP strategy for managing the summer flounder recreational fishery along the Atlantic coast includes state-by-state harvest targets derived from the proportion of each state’s estimated 1998 recreational landings. As the resource has shifted northward since then, the proportion of summer flounder caught in the southern states (e.g., North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware) has declined while the proportion caught by anglers fishing in two of the northern states (New Jersey and New York) has increased substantially. This has given rise to major disparities in state-by-state regulations, with annual harvest regulations regularly being relaxed in the southern states while measures that are more restrictive are required in New York and New Jersey in an attempt to keep landings in these states below their annual state harvest targets. Over 90% of the recreational catch in New York and New Jersey is now being released by anglers each year because of imposition of high minimum size limits coupled with low possession limits.

As the shifting summer flounder stock has rendered the FMP management strategy incapable of providing fair and equitable access for fishery participants throughout the range of the resource, development of the Summer Flounder Conceptual Model would allow the MAFMC to better understand both the economic and biological consequences associated with consideration of management strategies that depart from the current management process. In particular, an evaluation of new management strategies that may be able to convert regulatory discards into landings without raising overall recreational fishing mortality. For example, members of the MAFMC’s Advisory Panel have suggested that lowering the minimum size for summer flounder in New York and New Jersey would actually reduce overall mortality. They argue that anglers in these states are releasing more than ten fish, on average, to obtain a single summer flounder that is greater than the minimum size limit. If the minimum size limit was reduced, anglers would obtain their possession limit sooner and discard far fewer fish. They claim that the overall reduction in discards would more than offset the increase in landings and result in lower overall mortality. Given an assumed recreational fishing discard mortality rate of 10%, the management strategy evaluation could provide an assessment of these claims and possibly identify the optimal combination of possession and size limits that would maximize economic benefits without raising overall fishing mortality.

The data collected from NARFS II will be used to estimate the economic benefits obtained from reducing regulatory discards, as the model we develop will consider the differential values anglers in New York and New Jersey place on keeping and releasing summer flounder. Ultimately, the data and the model we develop will be coupled with biological information to conduct the management strategy evaluation. This work will be conducted as part of the MAFMC’s Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management (EAFM) process.

Each section of the survey instrument is described in more detail below.

Section A: Your Recreational Fishing Experiences

The first three questions in this section of the survey will be used to screen out respondents without summer flounder and black sea bass fishery experience, which we define as those who have not gone recreational fishing for summer flounder and/or black sea bass in the last five years. Anglers that haven’t fished for summer flounder or black sea bass within the past five years will only respond to the first two questions then be directed to skip to the last section of the survey (Section C) to answer demographic questions. By asking all license holders (eligible and ineligible) to complete the survey we will be able to assess relative sample representativeness by comparing the characteristics of our sample (e.g., avidity and demographics) to the characteristics of the population of recreational anglers at large, which can be found in NOAA-sponsored nationwide angler expenditure reports. As the characteristics of summer flounder and black sea bass anglers may differ from the population of anglers as a whole, we need information from both types of anglers to assess sample representativeness. Moreover, these questions provide information on avidity, fishing mode, and seasonality of fishing trips taken. Questions 4 and 5 enquire about target species and critical factors that may be considered when deciding whether to go saltwater fishing. The answer to these questions will be used to model the opt-out option (i.e. specified using a choice specific constant and anglers’ characteristics).

Section B: Saltwater Fishing Trips

The next section of the survey contains a set of Choice Experiment (CE) questions. These questions are designed to elicit the tradeoffs anglers make between two fishing trips that vary in the number of legal and sub-legal summer flounder and black sea bass caught, regulations, total number of fish that could be kept and must be released, trip cost, trip length, and not going saltwater fishing. After presenting respondents with these fishing and non-fishing options, the questions ask respondents to select the option they would take if given the opportunity. Responses to these questions are the key source of data required to estimate the economic model of angler behavior. Table 1. summarizes the attributes and levels to include in the CE questions.

Table 1. NARFS II Survey Attributes and Levels

Attribute |

Level range |

Bag limits: |

|

Summer flounder (SF) |

1-8 |

Black sea bass (BSB) |

10-30 |

Size limits (inches): |

|

Summer flounder |

16-24 |

Black sea bass |

10.5-14 |

Number of SF you catch |

1-15 |

Number of SF you keep: |

0-8 |

|

|

Probabilities (of alternative # of SF kept fish) |

0-1.0 |

Number BSB you catch |

0-25 |

Number BSB you keep |

0-25 |

Probabilities (# of BSB kept fish) |

1.0 (e.g. deterministic) |

Trip length (hours) |

2- 9 |

Trip mode |

Shore, private boat with fish finder, private boat w/o fish finder |

Total trip cost ($) |

20-800 |

|

|

Based on the lessons learned from the original NARFS, the CE questions in NARFS II will include: (1) the explicit introduction of risk uncertainty in the number of summer flounder anglers are allowed to keep, which is displayed using pie charts describing each possible outcome and its associated probability (e.g. 10% probably of keeping zero summer flounder, 30% of keeping one summer flounder, 60% of keeping two); and (2) the possibility that these probabilities may themselves not be known, a fact that is conveyed again through pie charts, but this time by presenting probabilities for the union of outcomes (e.g. the probability of 1 or 2 kept summer flounder is 2/3). These and alternative strategies for conveying risk uncertainty were tested and discussed with undergraduate students at the University of Maryland and again with anglers’ focus groups in New Jersey. The focus group participants found that the pie-chart approach for capturing catch uncertainty was far more realistic than the design employed in the first NARFS in which catch outcomes were predetermined and deterministic.

Section C: About You and Your Household.

Section C asks a series of demographic and other questions. These questions will gather information on age, gender, education, income, race and ethnicity. Used as conditioning variables, this information may improve estimation of the economic model. Additionally, we can use this information to assess relative sample representativeness by comparing the characteristics of our sample to the characteristics of the population of recreational anglers at large, which can be found in NOAA-sponsored nationwide angler expenditure reports.

The Northeast Fisheries Science Centers will retain control over the information collected by this survey effort and safeguard it from improper access, modification, and destruction, consistent with NOAA standards for confidentiality, privacy, and electronic information. See response to question A10 of this Supporting Statement for more information on confidentiality and privacy. The information collection is designed to yield data that meet all applicable information quality guidelines. Although the information collected is not expected to be disseminated directly to the public, results may be used in scientific, management, technical, or general informational publications. Prior to dissemination, the information will be subjected to quality control measures and a pre-dissemination review pursuant to Section 515 of Public Law 106-554.

Describe whether, and to what extent, the collection of information involves the use of automated, electronic, mechanical, or other technological collection techniques or other forms of information technology, e.g. permitting electronic submission of responses, and the basis for the decision for adopting this means of collection. Also, describe any consideration of using information technology to reduce burden.

The survey instrument will be administered online and by mail. Potential respondents will be randomly drawn from saltwater recreational fishing license frames in New York and New Jersey. Individuals selected will receive a mail to web-push survey invitation. Those that fail to complete the web-survey will receive mail/email reminders that include a web-link to the survey. A final mail survey will be sent to nonresponders.

Describe efforts to identify duplication. Show specifically why any similar information already available cannot be used or modified for use for the purposes described in Question 2

We conferred with state officials in New York and New Jersey who have responsibilities for managing recreational saltwater fishing and they could not identify any existing or planned duplicative survey efforts. Additionally, there are no NMFS-led or NMFS-sponsored recreational fishing surveys planned for 2021 in New York and New Jersey, with the possible exception of the NMFS-sponsored 2021 Social Network Analysis Survey (SNAS) which will be submitted for PRA approval in the near future. The purpose of the SNAS is to evaluate anglers’ level of knowledge of, understanding of, trust in, and preferences for recreational saltwater fisheries regulations, management, data collection, and data. The SNAMS will be directed toward recreational saltwater anglers along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts from Maine through Florida and will likely survey members of saltwater fishing organizations. Some of the anglers targeted by SNAMS may hold saltwater recreational fishing licenses and be part of the NARFS II sample frame in New York and New Jersey. As this is a NMFS-sponsored survey we will work with the sponsors of the SNAS to ensure that anglers do not receive both an SNAMS and a NARFS II.

The NARFS II will contain a series of discrete choice experiment (DCE) questions, each of which presents respondents with two or more hypothetical, multi-attribute alternatives and asks respondents to choose or rank their most preferred alternative. Each alternative is comprised of a combination of attribute levels, the ranges of which are carefully selected to fulfill policy-relevant research objectives. Responses to DCE questions can be used to evaluate choice behavior, preferences, and WTP values for marginal changes in attribute levels (Louiviere et al. 2000)

Several studies have employed a discrete choice experiment (DCE) to evaluate angler preferences for different aspects of the recreational fishing experience. Because they cover a wide range of species and fishery-specific research objectives, these studies differ in terms of the attributes used to explain angler preferences. In general, the attributes of interest to fisheries economists typically include catch or harvest rates and regulations. Angler preferences for marginal changes in catch and regulations have been estimated jointly for summer flounder in the Northeast (Massey at al. 2006; Hicks 2002), trout and grayling in Norway (Aas et al. 2000), paddlefish in Oklahoma (Cha and Melstrom 2018), trout in Michigan (Knoche and Lupi 2016), and pacific halibut and salmon in Alaska (Lew and Larson 2012; Lew and Seung 2010). In addition to catch rates and regulations, other studies have evaluated non-consumptive aspects of recreational fishing, such as hooking and losing, or seeing a target species (Goldsmith et al. 2018; Duffield et al. 2012). Lew and Larson (2015) exclude catch attributes from the utility function and estimate Alaskan charter boat angler preferences and willingness-to-pay for alternative bag and size limit restrictions. Like the proposed NARFS II, some studies have examined the interface between recreational catch and regulations by estimating the nonmarket value of fish that may be kept and of those which must be released. These studies consistently find that the recreational value of keeping fish is higher than that of releasing fish for a variety of species (Atlantic cod, haddock, and pollock: Lee et al. 2017; Pacific halibut, Chinook salmon, and coho salmon: Lew and Larson 2012; rockfish along the U.S. west coast: Anderson and Lee 2013; Anderson et al. 2013; groupers, red snapper, dolphinfish, and king mackerel along the U.S southeast coast: Carter and Liese 2012).

Recreational preferences for summer flounder and black sea bass in the East Coast have been previously evaluated in Holzer and McConnell (2017), using data from a 2010 summer flounder and black sea bass survey. However, while the authors explored the relevance of risk attitudes towards angler’s participation and welfare, the 2010 survey is over 10 years old and it was not designed to elicit both risk and ambiguity attitudes by anglers. In particular, elicitation of ambiguity preferences may shed light on the role of anglers’ subjective probability of catching the bag limit in the choice of a trip, which is relevant for the design of policy. The analysis in Holzer and McConnell (2017) was not designed to address this issue. Additionally, it’s highly likely that angler preferences for summer flounder and black sea bass have changed since the 2010 survey was conducted. As indicated above, bottom trawl resource surveys conducted by the NMFS Northeast Fisheries Science Center have shown that the center of the summer flounder population has moved northward over the past decade, due in part to ocean warming, and is now off the coasts of New York and New Jersey. This finding coincides with MRIP data that show the proportion of the overall Atlantic coast summer flounder and black sea bass catch caught by New York and New Jersey anglers has increased during the past decade. This means that the composition of anglers’ catch from New York and New Jersey has changed since 2010 and has likely resulted in shifting angler preferences for summer flounder and black sea bass. The proposed NARFS II data collection effort will capture these shifting angler preferences and lead to more accurate predictions of the effect of regulatory changes –which not only impacts expected catch, but the entire probability distribution of catching and keeping a given number of fish– on angler behavior.

If the collection of information impacts small businesses or other small entities, describe any methods used to minimize burden.

The collection of information does not involve small businesses or small entities.

Describe the consequence to Federal program or policy activities if the collection is not conducted or is conducted less frequently, as well as any technical or legal obstacles to reducing burden.

This one-time survey effort will collect all of the information needed to develop economic models of recreational saltwater fishing for summer flounder and black sea bass. This research will provide scientific and management support to NMFS’ Northeast Fisheries Science Center, NMFS’ Greater Atlantic Regional Fisheries Office, and the MAFMC. Not conducting the information collection will limit these agencies’ ability to account for anglers’ behavioral responses to regulatory changes and consequent impacts to angler welfare, thus limiting the ability of these agencies to manage fisheries consistent with federal and state law.

Additionally, the data and models developed from NARFS II will provide the foundation for addressing the summer flounder recreational fishing management issues deemed a priority by the MAFMC in their efforts to move away from single species management and towards EBM (https://www.mafmc.org/eafm). The MAFMC will be unable to appropriately address their priority management issue “Evaluate the biological and economic benefits of minimizing discards and converting discards into landings in the recreational sector. Identify management strategies to effectively realize these benefits.” without the data and models developed from NARFS II.

Explain any special circumstances that would cause an information collection to be conducted in a manner:

The NARFS II will be a cross-sectional volunteer survey asking anglers to respond once to a single questionnaire. Anglers receiving the NARFS II will be asked to fill out a multiple choice questionnaire within 30 days, but no written responses will be required. A stratified random sampling design will be strictly adhered to so that the results can be generalized to the population of summer flounder anglers in New York and New Jersey.

If applicable, provide a copy and identify the date and page number of publications in the Federal Register of the agency's notice, required by 5 CFR 1320.8 (d), soliciting comments on the information collection prior to submission to OMB. Summarize public comments received in response to that notice and describe actions taken by the agency in response to these comments. Specifically address comments received on cost and hour burden.

A Federal Register Notice published on Thursday, April 2, 2020 (85 FR 18557) solicited public comments. No substantive comments were received. We have also consulted with personnel at the New York Department of Environmental Conservation and the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife to obtain their views on the availability of data, frequency of collection, the clarity of instructions and recordkeeping, disclosure, or reporting format (if any), and on the data elements to be recorded, disclosed, or reported. No responses were received.

Explain any decision to provide any payment or gift to respondents, other than remuneration of contractors or grantees.

As a result of the incentive research conducted as part of the original NARFS, a $2 incentive will be included in 4,000 mail survey invitations to maximize survey participation for NARFS II and mitigate survey nonresponse bias by attracting participation from those who otherwise might not respond to the survey. As part of OMB’s "Terms of Clearance" for the original NARFS ICR, "a copy of the survey results, including the results pertaining to response rates with and without the incentive payment" was requested by OMB. A copy of the final survey report, completed by the contractor NMFS hired to conduct the NARFS on NMFS behalf, was forwarded to OMB by NOAA’s PRA Officer on May 7, 2020 (North Atlantic Recreational Fishing Survey Report 2020). The NARFS survey report provides considerable detail about survey sampling, survey implementation, survey outcomes, an assessment of the effects of the incentive ($2) on survey response rates, and recommendations for future NMFS surveys of recreational anglers (we have attached a copy of the NARFS Survey Report with this submission).

In terms of the NARFS incentive experiment, the findings aligned with previous research on small monetary prepaid incentives, as sampled anglers who received the $2 incentive condition were significantly more likely to respond to the questionnaire than respondents that did not receive the incentive (38.46% versus 25.31% respectively; chi-square = 56.45, p < 0.001). Thus, the NARFS final survey report recommended that future NMFS sponsored surveys of recreational anglers include a small monetary prepaid incentive to increase survey response and mitigate survey nonresponse bias. While the original NARFS targeted anglers fishing for Gulf of Maine cod and haddock, and NARFS II will target anglers fishing for summer flounder and black sea bass in New York and New Jersey, the overall sampling design will remain the same so we expect inclusion of a $2 incentive to result in a similar increase in survey response rates.

Also relevant to the proposed NARFS II are the results of a recently-implemented pilot test of the West Coast Saltwater Fishing Survey (WCSFS) (ICF 2018; OMB Control No. 0648-0750). Anglers in California, Oregon, and Washington who had saltwater fished in the last 12 months constituted the target population for the WCSFS. A random sample of 4,000 records, stratified by four regions (Northern California, Southern California, Oregon, and Washington) was drawn for the pilot test. The 4,000 sampled anglers were randomly assigned to one of three incentive levels (no incentive, $2, or $5) mailed with the first contact.

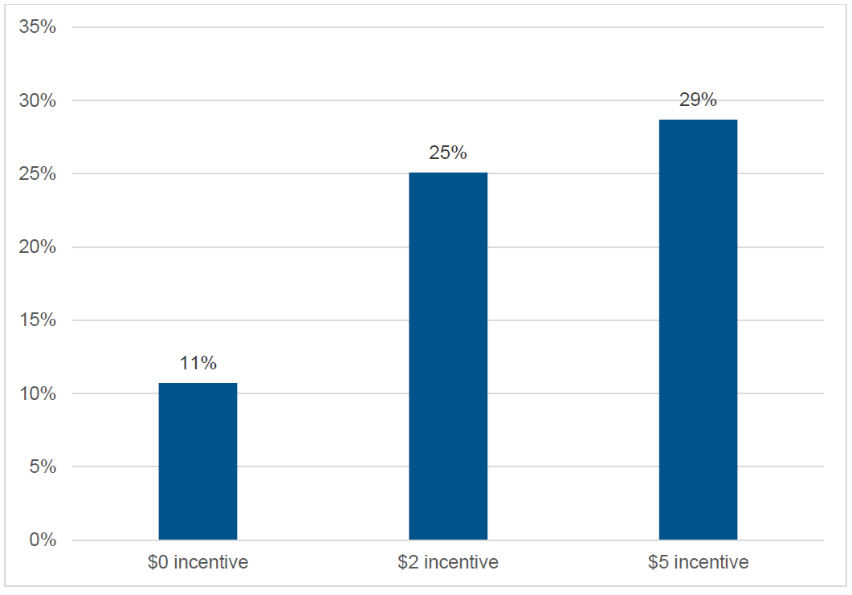

Each level of incentive significantly led to additional screener returns (Figure 1). The return rate for the $0 incentive amount was 11%. Adding $2 increased the return rate by 14 percentage points to 25% (z = -9.692; p < 0.001). Adding $3 more ($2 v. $5) increased completion by 4 percentage points more to 29% (z = -2.101, p = 0.036 for the comparison between $2 and $5). The finding further warrants including a $2 incentive in all of the mail correspondences during the NARFS II sampling procedure, We discuss this in detail in our response to question B3.

Figure 1. The Effect of Incentive on Screener Completion (ICF 2018)

Describe any assurance of confidentiality provided to respondents and the basis for the assurance in statute, regulation, or agency policy. If the collection requires a systems of records notice (SORN) or privacy impact assessment (PIA), those should be cited and described here.

Our sample frame will be drawn by an outside contractor from the 2019 recreational fishing license/registry databases maintained by the states of New York and New Jersey. Prior to receiving these license databases, our survey administration contractor will provide a signed agreement of access and a confidentiality agreement. The information in the license database and sample frame is covered under the Privacy Act System of Records COMMERCE/NOAA-11, Contact Information for Members of the Public Requesting and Providing Information Related to NOAA’s Mission. To support the anonymity of this research, no participant names will be included on the survey document. Participant names will be tracked in a separate database to code participants for protection during data analysis, confirm receipt of a survey from each individual, and avoid duplication of responses. The NARFS II will contain written text informing participants of the confidential and voluntary nature of their response.

Prior to providing deliverables, the agency contracted by the NEFSC to conduct the NARFS II will delete from the data all personal information such as name, street address, and phone number such that the NEFSC cannot link this information to any individual.

When writing final reports and publishing the findings of this research, tabulations of individual responses will occur at a high enough level of aggregation so that no single individual may be identified. In addition to the confidentiality protection measures, survey participants are provided the option to skip questions of concern and stop their participation in the survey at any time with no consequence to themselves. Finally, in the event of a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, we will protect confidentiality to the extent possible under Exemption 4 of the FOIA.

Provide additional justification for any questions of a sensitive nature, such as sexual behavior or attitudes, religious beliefs, and other matters that are commonly considered private. This justification should include the reasons why the agency considers the questions necessary, the specific uses to be made of the information, the explanation to be given to persons from whom the information is requested, and any steps to be taken to obtain their consent.

The NARFS II contains questions that solicit respondents’ income, race and ethnicity, which are considered sensitive information for some people. The NEFSC may use this information in two ways: first, by incorporating it into the economic model to control for variation in income that may affect angler preferences, as is common in estimating economic demand functions, and (2) to assess relative sample representativeness by comparing the characteristics of our sample to the characteristics of the population of recreational anglers at large, which can be found in NOAA-sponsored nationwide angler expenditure reports.

Provide estimates of the hour burden of the collection of information.

The annual burden of this data collection, across the three-year information request, is estimated to be 442 total responses, 102.10 hours, and $2,626 total annual wage burden costs.

See our response to Part B, Question 1 for the calculations used to estimate the number of total responses (516 eligible anglers + 810 ineligible anglers = 1,326 total responses). All survey responses are expected within the first year of the three-year information request, and taking an average over three years results in 442 responses. Burden hours estimated to complete the survey were determined from focus groups conducted in Maryland and New Jersey. Eligible anglers averaged 20 minutes and ineligible anglers averaged 10 minutes to complete the survey. Total burden hours for eligible anglers is estimated to be 516 anglers × 0.333 hours/angler = 171.83 hours. Total burden hours for ineligible anglers is estimated to be 810 anglers × 0.166 hours/angler = 134.46 hours. This yields a total burden of 306.29 hours, or 102.10 hours annually over the three-year information request.

While NMFS periodically collects household income-level data from saltwater anglers, personal income-level data for saltwater anglers are unavailable. Therefore, we use the May 2019 national BLS’ average hourly wage of $25.72 for “All Occupations” as a proxy for the hourly wage rate of our survey respondents.1 The resulting total wage burden costs are then estimated to be $7,878 (306.29 burden hours x $25.72 per hour), or $2,626 annually over the three-year information request. These results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. NARFS II Estimated Responses and Burden Hours

Information Collection |

Type of Respondent (e.g., Occupational Title) |

#

of Respondents/year |

Annual

# of Responses / Respondent |

Total

# of Annual Responses |

Burden

Hrs / Response |

Total

Annual Burden Hrs |

Hourly

Wage Rate (for Type of Respondent) |

Total

Annual Wage Burden Costs |

NARFS II |

Completion of mail/web surveys by an eligible angler |

172 |

1 |

172 |

0.333 |

57.28 |

25.72 |

1,473 |

NARFS II |

Completion of mail/web surveys by an ineligible angler |

270 |

1 |

270 |

0.166 |

44.82 |

25.72 |

1,153 |

Totals |

|

|

|

442 |

|

102.10 |

|

2,626 |

Provide an estimate for the total annual cost burden to respondents or record keepers resulting from the collection of information. (Do not include the cost of any hour burden already reflected on the burden worksheet).

There are no costs excluding the value of the burden hours in question A12. Mailed surveys will be accompanied by a postage-paid envelope.

Provide estimates of annualized cost to the Federal government. Also, provide a description of the method used to estimate cost, which should include quantification of hours, operational expenses (such as equipment, overhead, printing, and support staff), and any other expense that would not have been incurred without this collection of information.

The NARFS II will be administered and primarily analyzed by two outside contractors. The total costs to the federal government, over the three-year information request period, is $171,990. These costs consist of $45,000 to hire a contractor to administer the survey (includes the $2 incentive, programming, printing, and postage) and $73,200 to hire a second contractor to analyze the survey data, develop the behavioral models, and prepare reports outlining the methodology and results. Oversight and modeling assistance of one ZP-IV NOAA economist will also occur at a cost of $53,790. We use hourly loaded wage rates to estimate the cost of a NOAA economist’s time, assuming an annual salary of $148,000 and a 40% benefit load.

Average annual costs, over the three-year information request period, are shown in Table 3 below. The average annual cost of federal oversight and modeling assistance is estimated to be $17,930 ($206,092/year x 8.7%). The survey administration contractor is estimated to cost $15,000 ($45,000÷3) annually, and the contractor hired to conduct the modeling will cost $24,400 (73,200÷3) annually. Overall, the annual federal government cost is $57,330.

Table 3. NARFS II Estimated Annualized Costs

Cost Descriptions |

Grade/Step |

Loaded Salary /Cost |

% of Effort |

Fringe (if Applicable) |

Total Cost to Government |

Federal Oversight/Assistance |

ZP-IV |

$206,092/yr |

8.7 |

|

$17,930 |

Other Federal Positions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contractor 1 Cost |

|

$15,000 |

100 |

|

$15,000 |

Contractor 2 Cost |

|

16,520 |

100 |

$7,880 |

24,400 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Travel |

|

|

|

|

|

Other Costs: |

|

|

|

|

$12,000 |

TOTAL |

|

|

|

|

69,330 |

Explain the reasons for any program changes or adjustments reported in ROCIS.

The total burden of NARFS II, over the three-year information request period is estimated to be 1,326 total responses, and 306.29 hours. Supporting Statement A from the first NARFS estimated the burden of that survey to be slightly lower: 1,295 total responses, and 226.7 burden hours. However, the realized response rates from the first NARFS were higher than anticipated. We use the actual realized response rates from the first NARFS to calculate the estimated burden for NARFS II (Table 4).

Table 4. Respondents and Response Burdens Across NARFS and NARFS II

Information Collection |

Respondents |

Responses |

Burden Hours |

Reason for change or adjustment |

|||

Current Renewal / Revision |

Previous Renewal / Revision |

Current Renewal / Revision |

Previous Renewal / Revision |

Current Renewal / Revision |

Previous Renewal / Revision |

||

Telephone / Mail / E-Mail Surveys (NARFS) |

0 |

1,295 |

0 |

1,295 |

0 |

227 |

NARFS survey complete |

NARFS II |

4000 |

0 |

442 |

0 |

101.10 |

0 |

Current renewal request is based upon realized response rate from previous NARFS survey which was higher than anticipated, respondent pool has been corrected and anticipated responses/burden hours annualized |

Total for Collection |

4,000 |

1,295 |

442 |

1,295 |

102 |

227 |

|

Difference |

2,705 |

-853 |

-125 |

|

|||

Information Collection |

Labor Costs |

Miscellaneous Costs |

Reason for change or adjustment |

||

Current |

Previous |

Current |

Previous |

||

Telephone / Mail / E-Mail Surveys (NARFS) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Labor costs not included on previous submission |

NARFS II |

$2,626 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Updated annualized labor costs |

Total for Collection |

$2,626 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Difference |

$2,626 |

0 |

|

||

For collections of information whose results will be published, outline plans for tabulation and publication. Address any complex analytical techniques that will be used. Provide the time schedule for the entire project, including beginning and ending dates of the collection of information, completion of report, publication dates, and other actions.

Results of the economic models that use data collected by the NARFS II may be reported for management purposes or in peer reviewed journals. Tabulations of responses to NARFS II questions will be aggregated in order to maintain respondent confidentiality, as described in our answer to question A10.

If seeking approval to not display the expiration date for OMB approval of the information collection, explain the reasons that display would be inappropriate.

The agency plans to display the expiration date for OMB approval of the information collection on all instruments.

Explain each exception to the certification statement identified in “Certification for Paperwork Reduction Act Submissions."

The agency certifies compliance with 5 CFR 1320.9 and the related provisions of 5 CFR 1320.8(b)(3).

REFERENCES

Aas, Øystein, Wolfgang Haider, and Len Hunt. 2000. “Angler Responses to Potential Harvest Regulations in a Norwegian Sport Fishery: A Conjoint-Based Choice Modeling Approach.” North American Journal of Fisheries Management 20 (4): 940–50.

Anderson, L., S. Lee, and P. Levin. 2013. “Costs of Delaying Conservation: Regulations and the Recreational Values of Exploited and Co-Occurring Species.” Land Economics 89 (2): 371–85.

Anderson, L, and T Lee. 2013. “Untangling the Recreational Value of Wild and Hatchery Salmon.” Marine Resource Economics 28 (2): 175–97.

Brinson, A.A. and Wallmo, K. 2013. “Attitudes and Preferences of Saltwater Recreational Anglers: Report from the 2013 National Saltwater Angler Survey, Volume I”, NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-F/SPO-135

Carter, David W., and Christopher Liese. 2012. “The Economic Value of Catching and Keeping or Releasing Saltwater Sport Fish in the Southeast USA.” North American Journal of Fisheries Management 32 (4): 613–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02755947.2012.675943.

Cha, Wonkyu, and Richard T. Melstrom. 2018. “Catch-and-Release Regulations and Paddlefish Angler Preferences.” Journal of Environmental Management 214: 1–8.

Dimmock, S.G., Kouwenberg, R., Mitchell, O.S., and K. Peijnenburg. 2015. "Estimating Ambiguity Preferences and Perceptions in Multiple Prior Models: Evidence from the Field." Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 51:219-244.

Duffield, John, Chris Neher, Stewart Allen, David Patterson, and Brad Gentner. 2012. “Modeling the Behavior of Marlin Anglers in the Western Pacific.” Marine Resource Economics 27 (4): 343–57.

Ghirardato, P., Maccheroni, F., and Marinacci, M. 2004. "Differentiating Ambiguity and Ambiguity Attitude". Journal of Economic Theory, 118(2), 133-173.

Gilboa, I., and Schmeidler, D. 1989. "Maximin Expected Utility with Non-Unique Prior". Journal of Mathematical Economics, 18(2) 141-153.

Goldsmith, William M., Andrew M. Scheld, and John E. Graves. 2018. “Characterizing the Preferences and Values of U.S. Recreational Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Anglers.” North American Journal of Fisheries Management 38 (3): 680–97.

Harrison, M., Rigby, D., Vass, C., Flynn, T., Louviere, J., and K. Payne. 2014. "Risk as an Attribute in Discrete Choice Experiments: A Systematic Review of the Literature". Patient, 7(2):151-170.

Hauber,

A.B., Johnson, F.R., Grotzinger, K.M, and S.

zdemir.

2010. " Patients' Benefit-Risk Preferences for Chronic

Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura Therapies". The Annals of

Pharmacotherapy, 44:479-488.

zdemir.

2010. " Patients' Benefit-Risk Preferences for Chronic

Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura Therapies". The Annals of

Pharmacotherapy, 44:479-488.

Hicks, Robert L. 2002. “Stated Preference Methods for Environmental Management: Recreational Summer Flounder Angling in the Northeastern United States.” Fisheries Statistics and Economics Division, no. April: 111.

Holt, C. and S.K. Laury. 2002. "Risk Aversion and Incentive Effects." American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644-1655.

Holzer, Jorge and McConnell, Kenneth. 2017. " Risk Preferences and Compliance in Recreational Fisheries" Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, 4(S1):1-35.

ICF. 2018. “West Coast Saltwater Fishing Survey Pretest Report.” Submitted to National Marine Fisheries Servie.

Knoche, Scott, and Frank Lupi. 2016. “Demand for Fishery Regulations: Effects of Angler Heterogeneity and Catch Improvements on Preferences for Gear and Harvest Restrictions.” Fisheries Research 181: 163–71.

Lee, Min-Yang, Scott Steinback, and Kristy Wallmo. 2017. “Applying a Bioeconomic Model to Recreational Fisheries Management: Groundfish in the Northeast United States” 32 (2).

Lew, Daniel K., and Douglas M. Larson. 2012. “Economic Values for Saltwater Sport Fishing in Alaska: A Stated Preference Analysis.” North American Journal of Fisheries Management 32 (4): 745–59.

———. 2015. “Stated Preferences for Size and Bag Limits of Alaska Charter Boat Anglers.” Marine Policy 61: 66–76.

Lew, Daniel K., and Chang K. Seung. 2010. “The Economic Impact of Saltwater Sportfishing Harvest Restrictions in Alaska: An Empirical Analysis of Nonresident Anglers.” North American Journal of Fisheries Management 30 (2): 538–51.

Louiviere, Jordan J., David A. Hensher, and Joffre D. Swait. 2000. Stated Choice Methods: Analysis and Applications. Cambridge University Press.

Massey, D. Matthew, Stephen C. Newbold, and Brad Gentner. 2006. “Valuing Water Quality Changes Using a Bioeconomic Model of a Coastal Recreational Fishery.” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 52 (1): 482–500.

MAFMC (Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council). 2013. “Summer Flounder, Scup, and Black Sea

Bass Recreational Specifications Black Sea Bass Catch Limits for 2013 and 2014.” Supplemental Environmental Assessment, Dover, DE.

North Atlantic Recreational Fishing Survey Report. 2020. National Marine Fisheries Service, Northeast Fisheries Science Center Contract report submitted by ICF.

1 May 2019 National Occupation Employment and Wage Estimates United States, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupation Title: All Occupations (https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm#00-0000).

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-13 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy