Ssb_nisvs_12.7.22

SSB_NISVS_12.7.22.docx

[NCIPC] The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS)

OMB: 0920-0822

SUPPORTING STATEMENT: PART B

OMB# 0920-0822

The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS)

March 17, 2020

Point of Contact:

Sharon G. Smith, PhD

Behavioral Scientist

Contact Information:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control

4770 Buford Highway NE, MS S106-10

Atlanta, GA 30341-3724

phone: 770.488.1363

email: [email protected]

CONTENTS

Section Page

B. COLLECTIONS OF INFORMATION EMPLOYING STATISTICAL METHODS

B.1. Respondent Universe and Sampling Methods 3

B.2. Procedures for the Collection of Information 7

B.3. Methods to Maximize Response Rates and Deal with Nonresponse ...13

B.4. Tests of Procedures or Methods to be Undertaken……………………14

B.5. Individuals Consulted on Statistical Aspects and Individuals

Collecting and/or Analyzing Data…………………………………….29

B. COLLECTIONS OF INFORMATION EMPLOYING STATISTICAL METHODS

This is a revision request for the currently approved National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey - OMB# 0920-0822, expiration date 2/29/2020, for data collection and developmental activities.

A contract to redesign the NISVS data collection approach was awarded in late September 2018. The survey instruments have been developed and adapted for new data collection modes (i.e., paper and web-based survey administrations). Cognitive interviewing was completed 10/4/2019. Data collection for feasibility testing is scheduled to occur in March – June 2020. Data collection for the pilot testing is set to occur from January 2021 – April 2021. The focus of the current request is for approval of both feasibility and pilot testing.

The contractor’s (Westat) IRB is the IRB of record. As per the contract, CDC’s IRB will not be used for this contract because CDC is not engaged in the data collection effort.

After feasibility testing is completed, if changes to the OMB package are needed for the pilot testing phase, then we will submit an IRB revision and a non-substantive change request.

EXPERIMENTATION AND FEASIBLITY TESTING

The proposed study will test two different sample frames – a random digit dial (RDD) and address-based sample (ABS). The RDD survey will collect data using CATI and will use similar procedures as the previously administered NISVS. The ABS frame will receive a letter in the mail encouraging respondents to complete the survey on the web. Those who do not respond on the web will be mailed a paper survey or will be asked to call in to a telephone center (hereafter referred to as inbound CATI interview). The study will generate outcome prevalence estimates from each sampling frame (RDD and ABS), compare data quality measures across frames, and make recommendations for a final design for the NISVS moving forward. The final design will consider whether single or multiple frames are appropriate for future data collection efforts.

B.1. Respondent Universe and Sampling Methods

Target Population

For the feasibility phase of the NISVS redesign project, the target population is English-speaking women and men aged 18 and older in U.S. households. Those under age 18 are excluded because they are legally considered minors and their participation would necessitate significant changes to the study protocol. Additional exclusions include adults that are: 1) residing in penal, mental, or other institutions; 2) living in other group quarters such as dormitories, convents, or boarding houses (with ten or more unrelated residents) and do not have a cell phone; 3) living in a dwelling unit without a landline telephone used for voice purposes and also do not have a working cell phone; or 4) unable to speak English well enough to be interviewed. Those who do not speak English are excluded because the instrument and survey materials are limited to English.

Sampling Frames

Since one of the ultimate goals of the NISVS redesign project is to determine an optimal sampling frame to maximize response rates and reduce nonresponse, one objective of the feasibility phase of the project is to examine the performance of different sampling frames. Thus, this package seeks approval to test two sampling frames: 1) random-digit-dial (RDD) frame, and 2) address-based sample (ABS) frame. Details for each of these frames are provided below.

Random-digit-dial (RDD) frame

The RDD design will be a dual frame national survey, with approximately 80 percent of the completes being with cell phones and 20 percent with landline (LL). The cell phone frame comprises the majority of the sample because of its superior coverage, as well as the tendency for young adults and males to be better represented than on a landline. The cell numbers will be pre-screened to take out businesses and numbers identified as not likely to be active. For the landline frame, the numbers will be matched to an address list.

Table 1 provides the sample sizes and the anticipated eligibility and response rates for the cell and landline frames; the goal is to complete 2,000 interviews for the RDD frame. The assumptions related to response rates are based on the contractor’s prior experience with RDD surveys, as well as published rates for the NISVS. Approximately 80% of the sample will be drawn from the cell phone frame and 20% for the landline frame. For the landline frame, the numbers will be matched to an address list (this is the method used in previous NISVS collections). The cell phone frame comprises the majority of the sample because of its superior coverage, as well as the tendency for young adults and males to be better represented than on a landline. The cell numbers will be pre-screened to remove businesses and numbers identified as not likely to be active. To achieve 2,000 completed interviews in the RDD sample, the sample will be released in two waves for calling.

Comprehensive Screening Service (CSS), offered by Marketing Systems Group (MSG), will be used to reduce the landline numbers of unproductive calls in the sample. The service matches the landline telephone numbers to White and Yellow Pages of telephone directories to identify nonresidential business numbers in the sample. The numbers identified by this process will be coded as ineligible for telephone interviewing. CSS also applies an automated procedure in conjunction with manual calling to identify nonworking numbers. All sampled landline numbers, including those listed in the White Pages, will be included. Numbers found to be nonworking will be coded as ineligible and not released for telephone interviewing. In addition to CSS, address matching will be performed using reverse directory services for landline sampled numbers.

It is not possible to prescreen cell phone numbers or obtain addresses for them using telephone directories, because such directories do not exist. However, MSG is able to determine a cell phone number’s activity status using their proprietary Cell-WINS procedure. All numbers determined by this process to be “active” will be dialed. Those classified as “inactive” or “unknown” will be classified as ineligible and removed from data collection. The CSS also identifies cell phone numbers that had been ported from landline exchanges where telephone customers are allowed to swap their landline phones for cell phones and keep the same number. The original landline numbers therefore would not fall in the cell phone exchanges used for sampling cell phones but are treated as cell phones in data collection.

After 6 weeks, a subsample of households will be selected that have not responded for an additional round of non-response follow-up. We are proposing to sample approximately 50 percent of the non-responding households for this follow-up or approximately 5,000 non-respondents. Those in this sample will be offered a higher incentive of $40. The assumptions for this portion of the sample is that 6 percent of the landline and 10 percent of the cell sample will result in a completed interview, yielding an additional 402 completed interviews. This follow-up will be fielded over a 2-week period.

As shown in Table 1, a base total sample of 19,904 numbers will be selected. For the cell phone, we are treating the phone as a personal device and that it is not shared with others in the household. This eliminates the need to ask about others who may use the phone. For the cellphone frame, a little less than 15,000 numbers will be sampled. Once purging the businesses and non-active numbers, approximately 9,000 numbers will be dialed. Assuming a 20 percent screener response rate, a 95 percent eligibility rate, and a 95 percent conditional extended response rate (conditional on the screener being completed), the cell line will yield approximately 1,600 completed interviews. The cell phone has a high conditional extended response rate because the respondent who answers the phone is the targeted respondent. If they get through the initial screening for eligibility, they are likely to complete the NISVS survey. The landline frame begins with 5130 numbers. After purging, we are assuming an 18% screener response rate, a 98% eligibility rate, and a 65% conditional extended response rate, the landline frame will yield approximately 400 completed interviews (5130 x .68 x .18 x .98 x .65 = 400). The lower extended rate accounts for the need to switch respondents when someone other than the screener respondent is selected as the respondent. The combined response rate for the RDD survey, under these assumptions, is approximately 17 percent computed as: ((74% × the 19% cell response rate) + (26% × the 12% LL response rate)). The final response rate will be computed using AAPOR response rate formula RR4.

Table 1. Sample size, assumptions and number of completes for RDD frame

|

Cell phone frame |

Landline frame |

Total telephone numbers |

18,713 |

5,130 |

|

|

|

Residency after purging |

60% |

68% |

|

|

|

Total households |

11,228 |

3,489 |

|

|

|

Screener response rate |

20% |

18% |

|

|

|

Total screener completes |

2,246 |

628 |

|

|

|

Eligibility rate |

75% |

98% |

|

|

|

Households with eligible adults? |

1,684 |

615 |

|

|

|

Extended response rate |

95% |

65% |

|

|

|

Total extended completes |

1,600 |

400 |

|

|

|

Final Response Rate |

19% |

12% |

Address-based sample (ABS) frame

The goal is to complete 2000 surveys for this frame. The ABS will consist of mailing a request to the household for one individual to complete the survey. The process relies on selecting a respondent (see experiments below) and the respondent completing the survey using one of several different modes (web, paper, in-bound CATI).

A total of 10,582 addresses will be sampled. Based on prior surveys, we anticipate approximately 10 percent of these will be returned by the post office as non-deliverable. Some portion of the remaining sample will be ineligible households (e.g., vacant). However, this is considered to be a negligible number and no adjustment is made when computing response rates and weights. We have assumed an initial screening response rate of approximately 35 percent, with approximately 60 percent of those resulting in a completed NISVS survey. This will yield approximately 2,000 completed surveys, for a combined ABS response rate of 21 percent (0.35 x 0.60=0.21). This final response rate accounts for the entire ABS sample, combining across the different experimental conditions. For example, there will be an experiment that assigns non-response follow-up to a paper survey or to in-bound CATI. The above response rate combines across all of these experimental conditions.

The sampling frame will be drawn from a database of addresses used by MSG to provide random samples of addresses. The MSG database is derived from the Computerized Delivery Sequence File, which is a list of addresses from the United States Postal Service. It is estimated to cover approximately 98 percent of all households in the country. All non-vacant residential addresses in the United States present on the MSG database, including post office (P.O.) boxes, throwbacks (i.e., street addresses for which mail is redirected by the United States Postal Service to a specified P.O. box), and seasonal addresses will be subject to sampling. The sample will be drawn using implicit stratification, with the sample first sorted by geography. This will insure representation of all geographic regions of the country.

B.2. Procedures for Collecting Information

RDD Procedures

The field period for the telephone calls will be 6 weeks. To achieve the 2,000 completed interviews in the RDD sample, we plan to release the sample in two waves. The first wave will be a predictor sample replicating the characteristics of the entire sample. We plan to release 1,000 cases (800 cell and 200 LL) initially to ascertain sample performance and inform the second sample release to ensure we hit the target number of completes. The predictor sample is small enough that it can be put through the calling protocol in a shortened period (approximately 2 weeks) and provide data that will allow us to fine tune the full sample release (including reserve sample, if needed) to achieve 2,000 completed interviews within the allotted data collection period. The survey will be programmed in the Voxco computer software.

Data collectors for this study will go through a specific selection process. First, Westat’s staffing office will identify female candidates based on prior experience among existing staff, and intake interviews with new staff. These candidates will be sent an invitation to consider working on the project, including an overview of the study and a few sample questions, so that they can make an informed decision as to whether or not they are interested in pursuing this particular assignment. As a second step, one-on-one interviews will be conducted with those who respond to the initial invitation positively. The goal of these interviews is to make sure that candidates are informed about the scope of this project and its sensitive nature and that they can perform the desired level of sensitivity and professionalism this study warrants. The interviews will be tailored based on the experience level of the candidate (new vs. experienced) and candidates will have the option to opt out after learning more about the study.

All newly hired telephone interviewers receive the contractor’s general interviewer training which covers telephone interviewing protocols, best practices, and CATI administration and coding procedures. The project specific training will consist of self-paced tutorials, live interactive training sessions led by supervisory and management staff, and role play sessions. The role plays or live practice interviews continue until data collectors reach an adequate level of proficiency to start real production interviews. Interviewers will also receive distress protocol training including how to recognize and how to document distressed calls. Interviewers will be required to successfully complete each portion of training before they could proceed to the next portion.

As a standard Westat protocol, approximately 10 percent of the interviews will be monitored by a team leader (supervisor). During monitoring, team leaders hear both the respondent and interviewer while viewing the interviewer’s computer screen and their entries in real time. The interviewer and respondent are unaware of the monitoring. Team leaders discuss the results of each monitoring session with the interviewer. This discussion provides feedback to the interviewer, including what they did well, and suggestions to improve his or her techniques to gain cooperation, ask questions, or record responses. In addition, review sessions will be held on a rolling basis throughout the study. These sessions will be an opportunity for data collectors to talk about issues in gaining cooperation at both the household screening and extended interview levels, ask questions about unusual situations they may have encountered, and generally refresh their knowledge of study protocol and procedures. Per CDC’s request, monthly interviewer debriefings will be held as well. The discussions in these monthly debriefings will include topics such as problems encountered during interviews and difficult questions to administer.

Advance letters to the households with matching addresses in the predictor sample will be mailed approximately 3-5 days before calls are made. Pre-notification texts for the selected cell phones will also be sent a couple days prior to calling. The text message will inform the respondent about the upcoming call and will also include a toll-free number allowing respondents to call and schedule an appointment.

For the cell phone frame, the person who answers the phone will be screened to make sure that the phone is not for just business purposes, that they are able to safely proceed with the interview (e.g., not driving; in a location that affords some privacy), at least 18 years old, and live in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. For the landline sample, the interviewer will make sure the phone is not for a business use only and the respondent is at least 18 years old. For the landline frame, a respondent for the extended interview will then be selected using the Rizzo-Brick-Park (RBP) procedure that is currently used on the NISVS survey.

The surveys will use a graduated consent procedure. When initially introducing the study, the interviewer will describe it as a survey on “health and injuries”. Once a respondent is selected, the topic of the survey will be described in a graduated manner. The initial consent will describe the survey as on ‘health and injuries”. At the beginning of the first victimization section (stalking) the questions are introduced as “…physical injuries, harassing behaviors, and unwanted sexual activity.” Prior to each of the remaining sections, additional descriptions are given that are appropriate to the content of the items (e.g., use of explicit language). Respondents will be reminded to take the survey in a private location. They will also be informed that they can terminate the interview at any time.

The respondents’ addresses will be collected at the end of the interview to provide the incentive. A thank you letter including the incentive (cash) will be sent via USPS.

RDD Weighting and Variance Estimation

The weights produced for the RDD sample will combine the data from the landline and cell phone samples to estimate the national population. The weighting process has four stages:

Calculation of household weights for the landline and cell phone samples separately;

Calculation of person-level weights for the landline and cell phone samples separately;

Compositing the landline and cell-phone person-level weights, followed by trimming them; and

Raking the weights to agree with external population estimates.

The process will start with calculating a base weight, which will be based on the sampling rate. The base weight will be adjusted to account for the estimated proportion of the numbers with unknown residency that are residential along with other known residential nonrespondents. The person level weight for the landline sample will be calculated using the reported number of adults in the household (usually we cap the weight adjustment at 3 or 4). For the cellphone sample, the person that answers the phone is automatically selected, so there is no within-household adjustment needed. A simple nonresponse adjustment will be considered for the extended nonresponse (separately by landline and cell phone since the rates are so different). The typical approach is to use a single weighting adjustment cell nonresponse factor by type of sample (landline or cell).

A single set of weights (referred to as composite weights) will be calculated by dividing the sample into three groups: (1) those in the landline sample and who have a cellphone, (2) those in the cellphone sample with a landline phone and (3) those who only have a landline or a cellphone.

The

composite weight,

,

for person k

in household j,

will be calculated as:

,

for person k

in household j,

will be calculated as:

for

those from the landline sample with both types of phones

for

those from the landline sample with both types of phones

for

those from the cell sample with both types of phones

for

those from the cell sample with both types of phones

for

those who were landline-only or cellphone-only

for

those who were landline-only or cellphone-only

where

is the compositing factor for respondents with both landline and

cellular telephones from the landline sample. Thus, the final dataset

contains a single weight, PCWGT, for each respondent.

is the compositing factor for respondents with both landline and

cellular telephones from the landline sample. Thus, the final dataset

contains a single weight, PCWGT, for each respondent.

The composite weights will be trimmed to reduce the variance impact of large weights. The trimmed weights will be raked to national totals for age, gender, race, marital status and education from the latest American Community Survey 5-year data file.

Estimates of the precision of the estimates will be computed using replication methods (e.g., jackknife). The replication method is implemented by defining replicate subsamples for the sampling frame of telephone numbers and repeating all the steps of weighting for each replicate subsample separately. We will also to include variance stratum and variance unit identifiers on each record in the delivery files so that Taylor Series estimates of the standard errors can be produced.

ABS Procedures

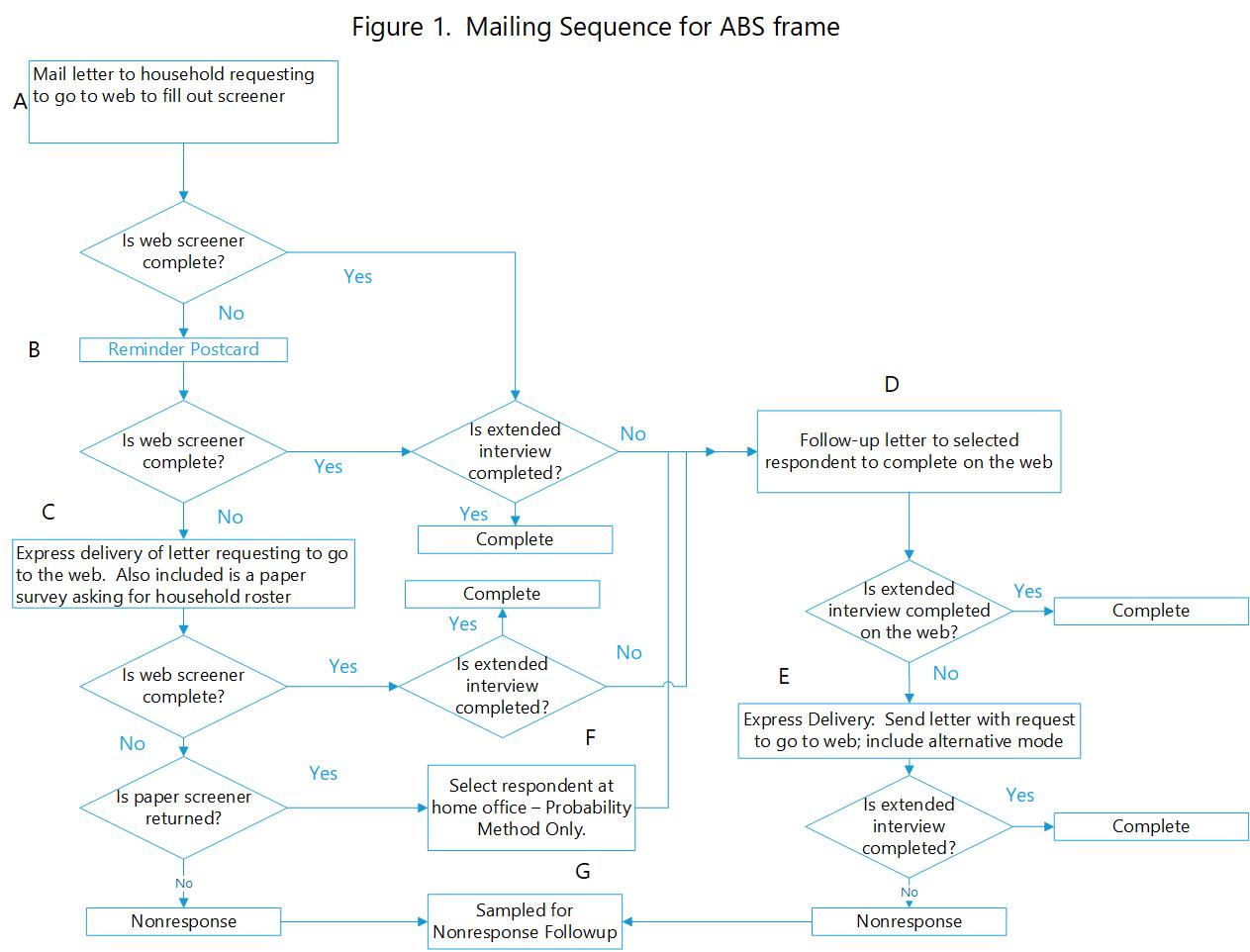

The procedures for the ABS frame are shown in Figure 1. The first step is to send a letter asking an adult to complete the screening survey on the web (Figure 1 - Box A). To increase the potential of the letter being opened and read, all letters use the CDC logo on the envelope and letter. The letter will contain a monetary pre-incentive of $5. Letters will include a unique PIN for each household and the URL to launch the survey. The letter will also include a helpdesk toll free number for any questions about the study. The web screener will ask the individual to answer selected questions about the household. It will then select an individual in the household to be the respondent for the main NISVS survey. If the person selected for the extended interview is the screener respondent, then the individual will be instructed to proceed directly to the extended interview. If the selected extended respondent is not the screener respondent, the screener respondent will be instructed to ask the selected adult to log in to the website and complete the survey.

A reminder postcard (Figure 1 – Box B) will be sent one week after the initial mailing. This will be sent to the entire sample. The text will thank those who have already responded. It will remind those that haven’t responded to do so.

The web version of the NISVS will have one question per page or, in the case of a sequence of similar questions, a grid-type format. The survey will automatically be formatted to the type of device the respondent is using (e.g., mobile phone, tablet, laptop). When logging in, the respondent will be required to change their password. Each screen of the survey will include a link to frequently asked questions, support resources (e.g., hotlines) and contact information for the project.

If the screener is not completed three weeks after the initial mailing, a letter will be sent by express delivery asking the respondent to either fill out the screener on the web or complete a paper version of the screener (Figure 1 – Box C). If the screener is not returned after this mailing, the household will be considered for subsampling for the non-response follow-up (Figure 1 – Box G).

Several procedures will be used to maintain the privacy of the survey respondents. As with the CATI/RDD version, a graduated consent process will be used. The letter and subsequent information provided to respondents will describe the study as being on health and injuries.

Once all attempts have been exhausted, a subsample of the non-respondents will be selected. Contacts will be made using the same procedures as above but offering a larger incentive of $30-$40 depending on the mode used to complete the survey (paper vs. in-bound CATI). For this purpose, we have assumed that we will subsample approximately 70 percent of the non-respondents. For the screener non-respondents, a letter will be sent by express mail asking them to go to the web. The package will also include a $5 pre-incentive and a paper screener. For the main interview non-respondents, an express mail letter will be sent requesting they go to the web or use an alternative mode. This group will also include anyone who is selected as a result of the follow-up of the screener non-respondents who sent back a paper screener.

The web survey is designed to have one question per page or, in the case of a sequence of similar questions, a grid-type format. The survey will automatically be formatted to the type of device the respondent is using (e.g., mobile phone, tablet, laptop). When logging in, the respondent will be required to change their password. Each screen of the survey will include a link to frequently asked questions, support resources (e.g., hotlines) and contact information for the project.

ABS Weighting and Variance Estimation

For the ABS sample, there will be four sets of weights: one set of weights will consider those who respond by web; a second set of weights will consider those who complete by web or by paper; a third set of weights are for those who respond by web, plus by in-bound CATI and a fourth set that combines the entire ABS sample regardless of mode or experimental group. These four weights will allow analysis to compare estimates across the three different mode combinations that are subject to experimental variation.

The weights will account for the probability of selection of the household and selection of the individual adult within the household. In addition, the weights will be adjusted for nonresponse and coverage errors, although the coverage error is expected to be small given the design. The data available for nonresponse adjustment is generally limited for ABS samples and is usually based on data associated with the geography of the sampled address. Data from various levels of geography will be linked to addresses and used in the formation of nonresponse adjustment cells.

The most effective weighting adjustments are likely to be the raking adjustment to control totals based on American Community Survey estimates. These control totals will include standard variables, such as age, sex, education, marital status and race.

For the weights for any substantial outlier, trimming or some other method will be implemented to reduce the effect of the outliers prior to finalizing the weights.

Estimates of precision will use the same method as the RDD (replication) and will also provide the appropriate information on the data file to use Taylor approximation.

B.3. Methods to Maximize Response Rates and Deal with Nonresponse

Incentives

An important goal of the redesign of the NISVS is increasing the response rate of the survey. Incentives are one of the most common and effective tools at increasing survey response. A review of the literature on incentives by Singer and Ye (2013, p. 134) concluded that “incentives increase response rates to surveys, in all modes.” This includes, mail, telephone, face-to-face, and web. There are conditions where incentives have differential effects on survey response and level of effort. Incentives are more effective in conditions of lower response (Singer and Ye, 2013). For surveys with lower response, there is more room to improve, or there are fewer competing motivating factors (e.g., high topic interest). Singer and her colleagues (Singer et al. 1999) found that incentives are more effective when burden is higher (e.g., longer survey, more difficult tasks), but even in low burden conditions incentives are effective.

For self-administered surveys, much of the research on incentives comes from studies where mail was the only mode of response. Compared to mail surveys, web surveys can differ in how respondents are invited to the survey, or in how incentives are delivered to respondents. Survey invitations can be delivered by mail, or if a frame of email addresses are available, by email (and in some cases both). Incentives, whether prepaid or promised, can be included in mail invitations or delivered electronically. Electronic incentives can also take many forms, such as digital bank credits (e.g., PayPal), or credits with online retailers (e.g., Amazon). There is very little data on the use of electronic pre-paid incentives.

Incentives are one of the most effective ways to increase the response rate. For the proposed NISVS design, pre-paying incentives for the ABS portion of the sample should boost the response rate by 10 to 15 percentage points, based on previous research. It is also useful to send a prepaid incentive to the RDD sample when it is possible. Promising an incentive also should be considered, as it has also been found to increase response rates for both telephone and web surveys. The amount of the incentive depends on the stage at which it is offered. For a pre-paid incentive, up to $5 has been tested and found to have a positive effect on response. The amounts for a promised incentive has ranged between $10 and $40.

Table 2. Use of Incentives by Sample Size

Incentive groups by sample frame |

Sample Size Offered Incentive |

RDD |

|

Pre-paid Incentive with letter to matched households |

|

$2 |

2,114 |

Promised incentive to complete the NISVS Interview |

|

For initial requests |

|

$10 |

10,746 |

For sampled non-respondents |

|

$40 |

5,800 |

ABS |

|

Pre-paid incentive |

|

For initial request |

|

$5 |

11,310 |

For sampled non-respondents |

|

$5 |

5,146 |

Promised incentive |

|

To complete household screener |

|

$10 to complete by web |

11,310 |

$5 to complete by paper |

10,122 |

|

|

To complete NISVS |

|

$15 to complete on web |

3,958 |

$15 for call-in CATI |

1,394 |

$5 to complete paper version |

1,394 |

|

|

For sampled non-respondents |

|

$40 |

6,254 |

*Number of eligible sampled persons who are offered the incentive. Estimate contingent on response rates assumed in the sample design. |

|

B.4. Tests of Procedures or Methods to be Undertaken

Testing Approaches for Research Questions

Research Question 1: For the NISVS survey, which assesses very personal and sensitive topics, does a multi-modal data collection approach result in improved response rates and reduced nonresponse bias compared to a RDD data collection approach?

Compute the differences in response rates between the RDD and ABS frames.

Response rates will be computed using RR#4 from the AAPOR response rate standards. When conducting statistical tests comparing response rates between the two frames (e.g., z-test), there will be 80 percent power to detect an actual difference of between one and two percentage points with a two-tailed significance test at the 95 percent confidence level (Table 3).

Table 3. Power Table

Comparison |

Size of Estimate |

||||

10% |

20% |

30% |

40% |

50% |

|

RDD vs. ABS |

|

||||

Response Rate (n = 17,476; 11,309) |

1% |

1% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

Selection-Weight Demographic Comparison, all adults (n = 1,979)+ |

3% |

4% |

4% |

4% |

4% |

Final Weight Comparisons with all adults (n = 1,484)* |

3% |

4% |

5% |

5% |

5% |

Final Weight Comparisons with adults age 18-49 (n = 891)* |

4% |

6% |

6% |

7% |

7% |

RDD - pre-notification text vs. no text |

|

||||

Screener response rate (n = 667) |

2% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

NISVS response rate (conditional on being eligible) (n = 5,000) |

2% |

2% |

3% |

3% |

3% |

Selection-weight demographic comparisons all adults (950)+ |

4% |

5% |

6% |

6% |

6% |

ABS |

|

||||

Respondent selection |

|

|

|

|

|

Final response rate (n = 5,655) |

2% |

2% |

2% |

3% |

3% |

Selection Weight - demographic comparisons (n = 990)+ |

4% |

5% |

6% |

6% |

6% |

Final Weight - comparisons with all adults (n = 742)* |

5% |

6% |

7% |

7% |

7% |

Paper vs. CATI call-in |

|

|

|

|

|

Response Rates (n = 1,393) |

3% |

4% |

5% |

5% |

5% |

Selection Weight - demographic comparisons (n = 357)+ |

7% |

9% |

10% |

10% |

10% |

n = effective sample size per group |

|

|

|

|

|

+ design effect of 1.2 * design effect of 1.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

Compute the differences in nonresponse bias between the RDD and ABS frames.

The analysis will use several different methods to assess differences in non-response bias (NRB). One will be to compare the distributions of key social and demographic variables to benchmarks for the target population (adults 18 and over). The benchmarks will be taken from national surveys with high response rates such as the American Community Survey and the National Health Interview Survey. The first set of analyses will compare demographic characteristics, including sex, age, race, ethnicity, household income, education, marital status and whether the individual was born in the U.S (Table 4). These comparisons will use the selection weights to account for the probability of selection into the sample (hereafter referred to as the selection-weighted estimates). Some of these characteristics will be used for weighting (e.g., age, race, ethnicity, marital status). Nonetheless, these initial comparisons will assess whether the proportion of respondents within these different groups differ with respect to the types of individuals that participate on the survey. Even if the characteristic is used for the weights, it is possible that individuals within the weighting cells differ between respondents and non-respondents. For example, if one of the frames is closer to the proportion of young people to the benchmark, the less likely it is that non-respondents will differ from respondents for this group. For those characteristics that are not being used for weighting, differences in the selection-weighted estimates provides information on how the methods compare on other characteristics that are related to the NISVS population.

Table 4. Characteristics to be compared between sampling frames and national surveys*

Characteristic |

Source |

CATI |

Web |

Paper |

Age |

ACS |

|

|

|

Race |

ACS |

|

|

|

Ethnicity |

ACS |

|

|

|

Household income |

ACS |

|

|

|

Education |

ACS |

|

|

|

Marital status |

ACS |

|

|

|

Born in US |

ACS |

|

|

|

Access to internet |

ACS |

|

|

|

Any adult injured in the past 3 months? |

NHIS |

|

|

|

Any adult with physical, mental or emotional problems? |

NHIS |

|

|

|

Any adult stay in a hospital overnight? |

NHIS |

|

|

|

House owned or rented? |

ACS |

|

|

|

Have asthma |

NHIS |

|

|

|

Have irritable bowel syndrome |

NHIS |

|

|

|

Have depression |

NHIS |

|

|

|

Rape and made to penetrate, adults 18-49 |

NSFG |

|

|

|

*ACS – American Community Survey; NHIS – National Health Interview Survey, NSFG – National Survey of Family Growth

The sample sizes for these comparisons will be number of completed surveys for each frame. The one-way distributions for each of these characteristics will be compared between the survey and benchmark estimates.1 The power for these comparisons will range from 3 to 4 percentage points, depending on the characteristic. For example, approximately 50 percent of the population should be female. There will be 80 percent power to detect a 4 percentage-point difference between the survey and benchmark estimate for this type of characteristic.

To assess non-response bias after the weights have been applied, a second series of comparisons will be made between the fully weighted estimates for the characteristics shown in Table 4 and their associated benchmarks. These comparisons will be restricted to those characteristics that are not used in the weighting. These characteristics include: household income, education, born in the US and whether the respondent has access to the internet. There will be 80 percent power to detect differences between 3 and 5 percentage points when comparing the survey and benchmark estimates.

The above analyses provide a way to compare how the two frames along characteristics that are correlated with NISVS outcomes of interest. A third series of comparisons will be between several of these outcomes and the benchmarks. These include 6 different health and injury indicators including: injuries (household), mental/emotional problems (household), hospitalization (household), whether the respondent has asthma, has Irritable Bowel Syndrome and has been depressed.

In addition, we will add to the survey a measure of rape and made to penetrate (MTP) from the NSFG to the end of survey. Estimates from this question will be compared to the 2015 – 2017 NSFG estimate. Prior analyses of NISVS have compared estimates of NISVS rape and MTP estimates to NSFG. However, differences in question wording makes these comparisons ambiguous. For example, the NISVS includes explicit questions on alcohol/drug-facilitated rape, while the NSFG asks a single question on forced penetration. Inserting the NSFG question into NISVS will control for the differences in question wording. Even this comparison will be confounded by other differences between the NISVS and NSFG methodology. For example, the NSFG is an in-person contact that is administered using an Audio Computer Assisted Self Interview (ACASI). Similarly, the placement of these questions on the NISVS surveys will be at the end of the survey, which creates a different context from the NSFG. Nonetheless, this comparison can be used as an additional measure of how the two frames are performing.

Comparison to the NSFG will involve restricting the sample to adults who are 18 to 49 years old. This cuts the sample by around 40% and reduces the power relative to the comparisons to the other final-weighted estimates. The rape estimate NISVS for 18-49 year-olds in 2016/17 was approximately 15 percent. The design would be able to detect a 5 percentage-point difference for this rate with 80 percent power (between a 10% and 20% estimate in Table 3).

The final analysis of non-response bias will compare key outcomes by the level of effort needed to complete the survey. Level of effort will be operationalized by the number of contacts needed to complete a particular survey. The outcomes that will be examined will include Contact Sexual Violence (CSV), Rape, Sexual Coercion, Unwanted Contact, Stalking, Intimate Physical Violence (IPV), Intimate Psychological Aggression (IPA) and any CSV, stalking, IPV or IPA.

Research Question 2: For the NISVS survey, does an ABS approach result in different prevalence estimates compared to a RDD approach? If so, does one approach result in better quality data over the other approach?

Using an RDD approach, NISVS has historically provided lifetime and 12-month estimates for victimization. State-level estimates have been made available after combining multiple years of data due to the need for a much larger sample size to produce reliable estimates. Therefore, given limited resources, the feasibility study is not designed to generate state-level estimates. For this research question, we will examine differences in estimates for the most prevalent lifetime NISVS outcomes and use those results as a proxy for the differences for 12-month outcomes.

To evaluate the overall quality of the information collected by the two frames, the analysis will begin by comparing key prevalence rates described above between the two frames. This will provide an indication of whether use of the ABS methodology will result in significant changes in the key estimates produced by NISVS. To assess quality, assessments will rely on the non-response bias analysis, as well as analyses that compare the outcomes to external and internal estimates. Data quality will also rely on analysis of rates of missing data, review of narratives provided by respondents and debriefing information on the privacy, confidentiality and burden of the survey. In addition, the analysis will review the web and paper surveys for indications of careless responding or extreme outliers.

Determine whether there are differences in prevalence estimates between RDD and ABS frames.

The prevalence rates that will be compared will be lifetime measures of Contact Sexual Violence, Rape, Sexual coercion, Stalking, any Intimate Partner Violence, Intimate Partner Psychological Aggression, any Contact Sexual Violence, Stalking or Intimate Partner Physical Violence. The design should be able to detect a difference between the frames of between 3%-5% with 80 percent power, depending on the measure. For example, for Contact Sexual Violence (42.8% in 2016/17) there is power to detect a 5 percentage-point difference. For rates lower than this, such as rape (15.6% in 2016/17) there will be 80 percent power to detect a difference of between 3 and 4 percentage points. For the rates near 50 percent (e.g., Intimate Partner Psychological Aggression), there will be 80 percent power to detect a 5 percentage-point difference.

Assess whether there is evidence to suggest that one approach results in better data quality than the other approach.

The analysis will assess data quality from several different perspectives. The first will test the extent of non-response bias (NRB) for the two surveys. The analysis of NRB is discussed in the section for Research Question 1 (above).

A second analysis will compare selected prevalence rates from NISVS to two alternative measures. One will be the NSFG questions that were discussed in the section on NRB. A second will be an estimate of unwanted sexual touching from the surveys using the item-count method (Droitcour, et al., 1991; Wolter and Laier, 2014). This method consists of providing a list of statements to respondents and asks the individual to count the number of statements that are true. On the NISVS instruments, one-half of the sample will get a list that includes a statement about being a victim of unwanted sexual touching, using identical language as one of the NISVS questions. The other half will get the same list, but with no statement about unwanted touching. By comparing the aggregate counts from the two lists, a rate of unwanted sexual touching can be calculated. Note that by asking for a count of items, rather than answers to each statement, there is an additional layer of confidentiality on reporting. The assumption is that responses will be less subject to motivated under-reporting when the question is asked directly. The estimates from each frame will be compared to the estimate derived from the main survey.

The third analysis will compare the rates of item-missing data from the two different frames. The analysis will assess the level of item-missing data for the entire survey, as well as concentrate on key sections used to derive the key victimization estimates. For example, the main screening items will be examined. Similarly, the extent to which respondents report for the number of perpetrators reported for particular types of victimization.

A fourth analysis will review the narratives that are being collected on an incident. At the end of the main survey (before debriefing questions), the respondent is read back a list of the types of victimizations they have reported. They are then asked to describe one of the incidents. These narratives will be reviewed to check the correspondence of the descriptions with the type of incident reported. For example, if an incident involving force is reported, the narrative will be used to assess the type of force that is reported and whether this fits within the intended definition.

A fifth analysis will use the debriefing items at the end of the survey to compare perceptions of confidentiality, privacy and burden of the survey. These items ask respondents about the privacy of the room, whether anyone else was in the room when taking the survey, who else was in the room and whether anyone in the household knows what the survey was about. This last item checks that the success of the two-stage consent procedure was successful. It also includes questions on the perceived length of the survey, the overall burden and the sensitivity of the questions. For each of these, we assume higher privacy/confidentiality and the lower burden have positive impacts on data quality. While not direct measures, these data will inform final decisions on survey procedures and the make-up of the survey.

When switching from an interviewer- to a self-administered survey, one concern is whether respondents will be sufficiently motivated to take the survey task seriously by reading the questions and carefully considering their answers. The analysis will use para-data, in particular, the timings from the web survey, to identify respondents who move through the survey too rapidly to read through the items. A second quality check will examine questionnaires with extreme answers (e.g., select all types of victimizations; report large number of partners). A third quality check will examine whether respondents provide inappropriate answers to two items that have been inserted into the self-administered modes. This is a method that has been used on self-administered surveys in a number of situations (Cornell, et al, 2014; Chandler, et al., 2020), including a recent survey measuring sexual assault among youth in residential placement (Smith and Stroop, 2019). The two items placed on the survey are: “I am reading this survey carefully” and “We just want to see if you are still awake. Please select ‘yes’ to this question”. These are placed within the section asking about health questions (reading carefully) and at the very end of the survey (select ‘yes’). We will use the para-data, extreme answers, and inserted questions to identify surveys that potentially provide low quality data.

Research Question 3: What are the optimal methods for collecting NISVS data with an ABS sample, with respect to respondent selection and follow-up mode?

Determine which respondent selection method results in the highest response rate and lowest response bias for the ABS frame.

Determine which follow-up mode results in the highest response rate and lowest response bias for the ABS frame.

ABS experiments

The feasibility test for the ABS frame includes two experiments. One will compare two respondent selection methods. One method will be a probability procedure and one a non-probability procedure.

Probability. The full probability method will be the Rizzo-Brick-Park (RBP) method. The RBP, as implemented on the landline portion of the NISVS, is a full probability method for any household with 1 or 2 adults. It is a quasi-probability method for households with 3 or more adults because it uses the birthday method to select the respondent.2 Our proposal is to use an abbreviated enumeration procedure instead of the next birthday method at this stage of the process. The shortened procedure would ask the respondent to identify the age and sex composition of the adults in the household. A random selection of an individual will be made, and the screener respondent will be instructed to ask the identified individual to take the main survey. This is an abbreviated enumeration because it does not ask for the name or initials of each adult member of the household.

The main advantage of this procedure is that it is closest to a full probability method which gives all adults in the household a known non-zero chance of selection. Prior research with quasi-probability methods, such as the next or least birthday method, has found there to be significant error with selection of the respondent (Battaglia, et al., 2008; Olson, et al., 2014; Hicks and Cantor, 2012). For example, Olson et al. (2014) found that for a paper mail survey, the wrong respondent was selected in 43% of two-person households.

When the first request to the household is sent, the respondent will be asked to go to the web to complete the household screener (Figure 1). The screener will include selecting an adult for the extended survey using the RBP method. The screener respondent will be instructed to ask the identified individual to take the extended survey. A reminder postcard will be sent out. For those still not responding after the postcard, a third mailing, sent express delivery, will be sent that asks someone in the household to complete the screener on the web, but also includes a paper version of the screener that asks for a roster of adults. This roster also asks for the age and gender of each individual. If the paper screener is returned, an individual will be randomly selected by Westat. The selected individual will be sent a request to fill out the survey.

Non-probability. The second experimental condition is a non-probability method. We propose using the Youngest Male Oldest Female (YMOF) approach. This method puts an emphasis on collecting data from younger people and from adult males. These two groups are traditionally under-represented in ABS mail surveys. To implement the YMOF, households will be randomly assigned to one of four groups: (1) youngest adult male, (2) youngest adult female, (3) oldest adult male, (4) oldest adult female. For each group, the respondent is asked to select that particular individual (e.g., youngest adult male) as the respondent. If the household doesn’t quite fit the particular profile (e.g., no adult males in household), additional instructions are given to select a respondent. For example, for group 1, for the youngest adult male group, if there is only one adult male in the household, the respondent is told to select that individual. If there are no adult males, then the person is asked to select the youngest adult female.

This is not a probability method because there are a small number of individuals who are not given a chance of selection. In particular, in households that have 3 or more adults of the same sex, those in the middle age group (i.e., neither youngest nor oldest) cannot be selected. The base-weight is computed using the reported number of adults in the household. Non-response and post stratification (or raking) adjustments are made to adjust for coverage and non-response. The assumption is that this last adjustment compensates for the relatively small number of households that have 3 or more same-gender adults. According to the American Community Survey (ACS), approximately 3.9% of the households have this particular age-gender profile.

This method, or various versions, have been used on other general population surveys and have resulted in successfully boosting the targeted groups (e.g., Marlar et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2015). However, when balanced against the lower response rates of the targeted groups, as well as the less intrusive nature of the respondent selection, this method can provide a better method than a full probability one, like the RBP. Prior research has not found significant differences in the population distributions among probability, quasi-probability or non-probability methods. Yan, et al. (2015) conducted a meta-analysis which examine several different within-household selection procedures for both mail and telephone surveys. Their measure of accuracy is the distribution of respondents with respect to gender, age and several other characteristics (e.g., income). The methods they examine are Kish, two birthday methods, Troldahl Carter (and variations) and the Youngest Male Oldest Female (YMOF) method. These last two non-probability methods put priority on selecting a household member in a particular age or gender group. With respect to gender, they found the YMOF method comes closest to the population distribution. They did not find any differences with respect other characteristics (e.g., age, education, income).

The advantage of this procedure is that it is minimally intrusive, and it can be implemented in a single step. The procedure can be described in the letter to minimize the number of people who log onto the web and have to switch respondents between the screener and extended survey. At the first mailing, the respondent is asked to send the selected person to web. The initial questions on the web will go through the respondent selection procedure to verify this is the right person. If it is, then they are asked to proceed with the survey. If there is no response, a follow-up reminder letter (with respondent selection instructions) is sent. If there is no response to this, an express letter is sent with the respondent selection instructions, but also contains a paper version of the respondent selection procedures. The respondent is asked to fill out either the web or paper version. If the paper version is filled out, we ask that it is sent back to the home office. Once the screening questions are completed, the follow-up contacts with the selected respondent are similar to those used for the probability method.

For this experiment, half of the sample will be randomly assigned to each method. When comparing response rates, there will be 80 percent power to detect differences of 2 to 3 percentage points, depending on the response rate (Table 3). To compare the demographic distributions using the selection weights, there will be power to detect differences between four to six percentage points. When using the final weights, there will be power to detect differences of between 5 to 7 percentage points.

The second ABS experiment will compare two different modes to complete the extended survey. If the selected respondent does not complete the survey in response to the initial request to go to the web survey, a second request will be made that gives the respondent the opportunity to complete the survey with one of two alternative modes. Half the non-respondents will be told they can complete an abbreviated paper version of the survey, while the other half will be told they can call in and complete the survey with a telephone interviewer. In both cases, the respondent will still be able to complete the survey by web.

Paper option. The paper version is offered because prior research has found that respondents are more likely to fill out a paper survey than other possible modes (web, telephone) (Montaquila, et al., 2013). With respect to response rates, paper and pencil instruments tend to yield the highest response rates (Messer and Dillman, 2011). Mixing web and paper surveys can also yield high response rates, although even here a significant number of respondents end up using the paper instrument. For example, without offering a bonus to complete the survey on the web, approximately two-thirds of respondents complete by paper in mixed-mode surveys (Messer and Dillman, 2011). By offering more money to complete the survey by the web, as we propose in the experiment below (section 2.2.3), we expect that approximately one-third of respondents will complete by paper (Biemer, et al., 2017).

In-bound CATI option. The second condition for this experiment is an inbound CATI interview. Respondents will be given the opportunity to call into an 800 number to complete the CATI version of the survey. One of the disadvantages of the paper survey described above is that it requires simplifying the NISVS instrument. Without a computer to drive the skip patterns, the paper instrument will not collect as much of the detail as the CATI or web surveys. For example, it will not be possible to collect data on each of the different perpetrators for each type of victimization. An inbound CATI has the advantage of collecting all of the NISVS data, rather than an abbreviated version as done on the paper version. The disadvantage is that asking respondents to call into an 800 number has not generally been successful in other contexts. However, given the offer of an incentive, we believe it is worth testing against the paper option.

There will be approximately 1,393 respondents in each of the two experimental groups. The power to test differences in response rates will range from three to five percentage points. Comparing demographic comparisons between the modes will only have around 357 individuals per group. However, if the response rates are relatively equal, and there are no large differences in the demographics between groups, the expanded information provided by the CATI will be considered to be a significant advantage to the paper.

Research Question 4: What is the effect of prenotification in the RDD on the response rate and non-response bias for NISVS?

Determine whether a prenotification text results in a higher response rate and lower nonresponse bias for the RDD frame.

The RDD will include an experiment that tests whether a text message sent to sampled cell phones prior to making the first call will increase response rates. This method has not been widely used on telephone surveys because of the 2015 declaratory Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ruling that expanded the definition of autodialer equipment. The experiment is based on a more recent declaratory ruling by the FCC which broadly exempted the Federal Government and its direct agents from the requirements of the Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPS). The TCPA requires obtaining prior express consent before making most calls or sending text messages (SMS) to mobile phones. Therefore, sending text messages on behalf of CDC without prior express consent is permissible as long as CDC instructed Westat to do so on its behalf. Westat will acknowledge that we are acting on behalf of CDC in our communications. Based on this, Westat will send a text to pre-notify the individual about the upcoming survey. It will mention the incentive, as well as that they will be receiving a call from the CDC. Half the cell phone numbers will be assigned randomly to this treatment, while the other half will not receive any text message at all.

The analysis of this experiment will examine both the screener and extended interview response rates. There will be approximately 13,000 numbers that are sent a text. For testing differences in the screener response rates, there will be 80 percent power to detect a 2 percentage-point difference (Table 3). To test whether the NISVS response rate, conditional on determining the respondent is eligible (e.g., at least 18 years old), there will be power to detect a difference between 2 and 3 percentage points.

To assess differences in non-response bias, we will compare the selection-weighted demographic distributions. Note that the cell phone frame does not include those that do not have a cell phone. Comparing the demographic distributions will provide texting increases the sample in the selected demographic groups. The power of these comparisons will be between 4 and 6 percentage points, depending on the demographic group.

Research Question 5: For NISVS, what is the total survey error for the ABS and RDD designs?

Compute the total survey error for the RDD frame and compute the total survey error for the ABS frame.

The Feasibility study will assess the performance of the ABS approach for NISVS. Ideally, the analysis would estimate the total survey error (TSE) of the estimates of the ABS and RDD approach. The TSE is the sum of the error due to variability and bias for any particular survey estimate ‘x’:

TSE = Variance(x) + Bias(x)2

It will be possible to assess the variability of particular estimates using design-based estimators (e.g., balanced repeated replication). Estimating the bias term, however, is not possible because it requires the availability of a measure that is considered ‘better’ than the survey. However, the study has built in a number of data quality measures which will be used to generate an overall quality profile of the ABS and RDD surveys.

For purposes of comparison, the cost, variability and other data quality measures will be assessed for both frames. Assuming that the ABS approach is implemented moving forward, this comparison will inform data-users on how the new methodology differs from what had been used in the past.

Calculating costs, sample sizes and variance of estimates

The first step will be to calculate how many completed surveys can be collected for a fixed cost. For the ABS, a final design will be determined by choosing a respondent selection method (probability vs. non-probability) and the type of non-response follow-up (paper vs. call-in CATI). The cost per completed survey will be calculated based on the feasibility test. Similarly a final design for the RDD will be recommended based on the results of the experiment with text messages. Once a decision on this is made, the cost for a completed survey will be calculated for the RDD.

These costs will be used to calculate the expected variance for key outcomes given a fixed cost. The expected variances will be computed assuming funds are available to collect a fixed number of surveys for each sex using the ABS design (e.g., 10,000 females and 10,000 males). Variances for the RDD outcomes will be calculated using the number of surveys that can be collected using the cost of the ABS frame. For example, if it costs $60 per completed survey for ABS, it will cost approximately $120,000 to collect 10,000 surveys from each sex. The cost of the RDD will than be used to calculate how many surveys can be collected for $120,000, along with the consequent variance for these estimators.

Other Data Quality Measures.

Our overall assessment of data quality will rely on building a quality profile of the ABS and RDD surveys. Table 1 summarizes the data quality measures and how they will be used in building the profile.

One of the primary reasons for redesigning the NISVS is the declining response rate, as well as for RDD surveys more generally. Low response rates have two important consequences for data quality. One is they increase the cost of conducting the survey. Higher costs will lead to smaller samples and less reliable data. Second, response rates are negatively correlated with non-response bias. While the response rate is only an indirect indicator of data quality, it is the case that the lower the response rate, the better the chance that the estimates will be affected by non-response bias (Brick and Tourangeau, 2017). Low response rates also decrease the confidence analysts have with the data (face validity).

For the above reasons, decisions about the design of the NISVS will first focus on whether the ABS has a significantly higher response rate than the RDD survey, as well as whether there are indications of non-response bias for the ABS. As noted earlier, prior analysis of the NISVS has not shown any signs of significant non-response bias. The analysis of the ABS design will evaluate non-response bias and compare it to similar analyses of the RDD survey.

A second set of analyses will assess how the major outcomes from the ABS and RDD designs differ from each other and the NSFG. One standard of data quality for sensitive behaviors like that collected on NISVS is to assume higher rates are better than lower rates (‘more is better’). This is based on the assumption that respondents tend to underreport these behaviors because of not wanting to reveal the information to another individual, such as the interviewer. The use of self-administered modes in the ABS design will address this relative to the telephone interview conducted with respondents from the RDD frame. However, there are other types of errors that may pull the estimates in the opposite direction. For example, respondents may comprehend questions better if an interviewer administers them, rather than relying on respondents reading the question themselves and following instructions. This might reduce reports of behaviors. To get a better sense of the quality of the measures, we will compare the measures of rape and made to penetrate to the NSFG. While not entirely comparable to NISVS, the NSFG is an external measure that has a significantly higher response rate and is conducted using a self-administered survey. Feasibility results that are closest to the NSFG, all other things equal, will be considered to have less bias. This measure of quality will supplement the non-response bias analysis described above.

One issue for NISVS moving to an ABS design is that an interviewer is not able to control and monitor the administration of the survey. This covers everything from the use of the graduated consent procedure to monitoring the emotional reactions of the respondent to assessing the immediate environment in which the survey is being administered (e.g., is anyone else listening). The analysis has built in several different measures to provide data on the effects of using a self-administered vs an interviewer administered survey. One is to generate alternative estimates of sexual touching using the item-count method. One would expect there to be closer alignment of the NISVS and item-count estimates for the self-administered surveys because of the extra layer of privacy built into the procedure. The analysis will compare the ABS and RDD along these lines.

A second set of analyses will compare perceptions of privacy, confidentiality and the immediate survey environment for the ABS and RDD surveys. The goal is that the ABS survey leads to at least as much privacy and confidentiality as the RDD. In addition, this analysis will check relative success of the graduate consent procedure across the two modes by asking if other members of the household were knowledgeable of the survey topic.

Finally, the analysis will examine the overall data quality of the web and paper responses by examining item missing data, extreme values, paradata (e.g., timings), the narrative and the number of respondents who answer the planted questions in the wrong way. These data will be used to classify respondents by how carefully they filled out the survey and their adherence to the intended definitions of the survey.

Quality indicator |

Data quality characteristic |

Response Rate |

Cost Face validity |

Non-response bias analysis |

Bias related to underrepresentation of key groups |

Comparison to NSFG |

Bias in measures of Rape and Made to penetrate |

Item Count |

Effect of motivated underreporting on estimates of sexual touching |

Perceptions of privacy and confidentiality |

Does the survey setting provide the privacy and confidentiality respondents?

Are privacy safeguards adequate for ABS procedures? |

Data quality on web and paper

Item missing data Extreme values Paradata and planted items

Narrative |

Are respondents motivated to respond?

Content validity |

Ultimately, the experimentation and feasibility phase of the NISVS redesign involves a comprehensive approach to understanding the advantages and disadvantages to moving from an RDD survey to an ABS frame with a push to web-based survey completion. Decisions that will be made to determine the novel NISVS data collection approach will therefore rely on a number of different aspects and will ultimately take into consideration the best cost-accuracy profile based on the results of the experiments described herein. There, of course, will remain some limitations. For instance, it may be difficult to estimate accuracy due to the lack of a gold standard to use as a comparison. However, this is why CDC has incorporated the comparison of estimates from the ABS to the RDD sample, which has been used historically to collect NISVS data. Additionally, CDC will compare prevalence estimates from both the RDD and ABS frames to estimates generated from previous full-scale NISVS data collections. A second limitation is the lack of understanding about the seriousness with which respondents complete a survey on the web (i.e., are they clicking through the survey simply to reach the end, or are they being careful and thoughtful about their responses?). As discussed herein, CDC has incorporated the inclusion of planted questions and the examination of paradata to improve our understanding of the seriousness of web-based survey completions. Overall, the recommendation for the future NISVS data collection design will be based on a reflection of what is learned from the results of the experiments outlined above.

PILOT TESTING

The pilot phase will be designed based on recommendations from the feasibility phase and will replicate methods used in the feasibility phase using a smaller sample. The goal of the pilot phase is to field the survey using the features anticipated for the full-scale NISVS collection (to be completed at a future time under a future OMB submission), but to do so over a short period of time. The plan is to complete 200 surveys using the recommended design. This phase will primarily be an operational test to assess whether the recommended design works as anticipated from the feasibility study.

Assuming a design using both RDD and ABS (web/paper), the sample sizes will be as follows: RDD, 66; ABS web, 86; ABS paper, 43; ABS in-bound CATI, 5. The procedures will mirror those used in feasibility testing (see sections B.2-B.4).

The analysis will examine the response rates, sample composition by demographic groups and costs. The target population will match the requirements used in the feasibility study, but a small number of Spanish-speaking participants will also be recruited.

B.5. Individuals Consulted on Statistical Aspects and Individuals Collecting and/or Analyzing Data

Individuals who have participated in designing the data collection:

CDC Staff:

Sharon Smith, Ph.D. 770-488-1368 [email protected]

Kristin Holland, Ph.D. 770-488-3954 [email protected]

Kathleen Basile, Ph.D. 770-488-4224 [email protected]

Jieru Chen, Ph.D. 770-488-1288 [email protected]

Marcie-jo Kresnow–Sedacca, M.S. 770-488-4753 [email protected]

Thomas Simon, Ph.D. 770-488-1654 [email protected]

Kevin

Webb 770-488-1559 [email protected]

Westat, Inc. Staff:

Eric Jodts 301-610-8844 [email protected]

David Cantor, PhD [email protected]

Regina Yudd, PhD [email protected]

Ting Yan, PhD [email protected]

J. Michael Brick, Ph.D. [email protected]

Douglas Williams [email protected]

Richard Valliant, Ph.D. [email protected]

Darby Steiger [email protected]

The following individuals participate in data analysis:

CDC Staff:

Jieru Chen, PhD 770-488-1288 [email protected]

Marcie-jo Kresnow-Sedacca, MS 770-488-4753 [email protected]

Westat, Inc. Staff:

David Cantor, PhD [email protected]

Ting Yan, PhD [email protected]

J. Michael Brick, PhD [email protected]

Douglas Williams [email protected]

Richard Valliant, PhD [email protected]

Darby Steiger [email protected]

Mina Muller [email protected]

REFERENCES

Battaglia M, Link MW, Frankel MF, Osborn Larry, & Mokdad AH. (2008). “An Evaluation of Respondent Selection Methods for Household Mail Surveys.” Public Opinion Quarterly 72: 459-469.

Biemer PP, Murphy J, Zimmer S, Berry C, Deng G, & Lewis K. (2017). Using bonus monetary incentives to encourage web response in mixed-mode household surveys. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology, 6, 240–261.

Brick, M. & Tourangeau R. (2017). Responsive Survey Designs for Reducing Nonresponse Bias. Journal of Official Statistics 33 (3): 735–752.

Chandler J, Sisso I, & Shapiro D. (2020). Participant carelessness and fraud: Consequences for clinical research and potential solutions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 129(1): 49-33.

Cornell DG, Lovegrove PJ, & Baly MW. (2014). Invalid survey response patterns among middle school students. Psychological Assessment, 26(1): 277–287.

Droitcour J, Caspar RA, Hubbard ML, Parsley TL, Visscher W, & Ezzati TM. (1991). The item count technique as a method of indirect questioning: A review of its development and a case study application. PP. 185 – 210 in Biemer, P., Groves, R.M., Lyberg, L.E., Mathiowetz, N.A. and S. Sudman (eds). Measurement Errors in Surveys. John Wiley & Sons: New York.

Hicks W & Cantor D. (2012). Evaluating Methods to Select a Respondent for a General Population Mail Survey.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, Orlando, FL.

Marlar J, Chattopadhyay M, Jones J, Marken S & Kreuter F. (2018). Within-Household Selection and Dual-Frame Telephone Surveys: A Comparative Experiment of Eleven Different Selection Methods. Survey Practice Volume 11, Issue 2.

Messer BL & Dillman DA. (2011). Surveying the general public over the internet using address-based sampling and mail contact procedures. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(3), 429–457.

Montaquila JM, Brick JM, Williams D, Kim K, & Han D. (2013). A Study of Two-Phase Mail Survey Data Collection Methods. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology, 1, 66–87.

Olson K, Stange M & Smyth J. (2014). Assessing Within-Household Selection Methods In Household Mail Surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 78(3):656–678.

Smith J & Stroop J. (2019). Sexual victimization reported by youth in juvenile facilities, 2018. Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 253042.

Singer E & Ye C. (2013). The use and effects of incentives in surveys. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 645(1), 112-141.

Singer E, Van Hoewyk J, Gebler N, & McGonagle K. (1999). The effect of incentives on response rates in interviewer-mediated surveys. Journal of Official Statistics, 15(2), 217-230.

Wolter F, & Laier B. (2014). The effectiveness of the item count technique in eliciting valid answers to sensitive questions. An evaluation in the context of self-reported delinquency. Survey Research Methods, 8(1): 153 – 168.

Yan T, Tourangeau R, & McAloon R. (2015). A Meta-analysis of Within-Household Respondent Selection Methods on Demographic Representativeness. Paper presented at the 2015 Federal Committee on Survey Methodology Research Conference, https://nces.ed.gov/FCSM/pdf/H3_Yan_2015FCSM.pdf

1 A design effect of 1.2 from the design weights is assumed for these comparisons.

2 The birthday method is implemented if the screener respondent was not selected for the interview and there are 3 or more adults in the household.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Smith, Sharon G. (CDC/DDNID/NCIPC/DVP) |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2023-07-29 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy