ACP Conversation Guide

Attachment 3_ACP Conversation Guide (2).docx

Generic Clearance for the Collection of Qualitative Feedback on Agency Service Delivery (NIH)

ACP Conversation Guide

OMB: 0925-0648

Advance Care Planning Conversation Guide

Title: Advance Care Planning Conversation Guide

Table of Contents

Use the Table of Contents to help find things quickly.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: What is advance care planning? 4

What does an advance care plan cover? 4

Why do I need an advance care plan? 5

Advance care planning for people with dementia 6

Overcoming barriers to advance care planning 6

What happens if I do not have an advance care plan? 7

Is an advance care plan legally binding? 7

Chapter 2: How do I start my advance care plan? 9

Think about what matters most in life 9

Think about what matters most when making medical decisions 10

Chapter 3: How do I make a living will? 11

How is a living will different from a will? 11

Learn about common care and treatment decisions. 11

Learn about common, life-sustaining medical treatments. 11

Learn about other future medical or end-of-life care decisions and forms. 13

Learn about other care options. 14

Talk with your doctor about your current health and care options. 15

Who on my health care team should I talk to about my advance care plan? 15

Tips for talking with your doctor about advance care planning 16

Other tips before your visit: 16

Make Your Living Will Official 18

Chapter 4: How do I choose a health care proxy? 19

What is a health care proxy and what decisions can they make? 19

Common powers of a health care proxy 19

Who should I choose as my health care proxy? 20

Who should I consider to be my health care proxy? 20

Who should I choose as my health care proxy? 21

How do I ask someone to be my health care proxy? 21

Prepare for the conversation. 21

Keep the conversation going. 22

How do I make my health care proxy official? 23

Chapter 5: How to make your advance care plan official 24

Where to find your advance directive forms. 24

How to make your advance care forms official 25

What to do after you fill out your advance directive forms. 25

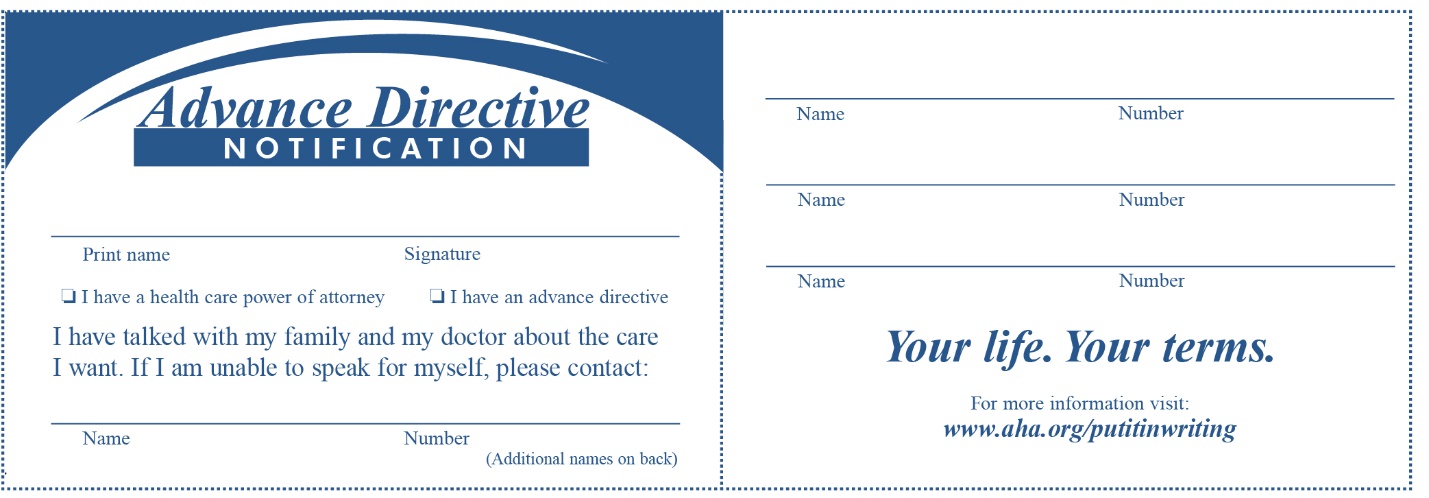

Advance Directive Wallet Card 25

Who else needs to know about my advance care plan? 26

Maintaining your advance care plan and preparing for future decisions. 26

Chapter 6: Plan for other decisions 27

How to plan for long-term care 27

How to make a will and do financial planning for your estate 27

How to pay for future health care. 27

How to make funeral and burial arrangements in advance. 28

Chapter 7: Advance Care Planning for Caregivers and Family Members 29

What to do when your loved one does not have an advance care plan 29

How to support advance care planning when the person is still able to make decisions. 29

How to support advance care planning when the person is not able to make decisions. 30

Advance care planning when a person has dementia 31

What does it mean to be someone’s health care proxy? 31

Is being a health care proxy right for you? 31

How to be a health care proxy 32

Advocating for your loved one’s care. 32

What questions should I ask before making medical decisions? 33

Other tips for family members and caregivers 34

Where can caregivers and family members find resources and support? 34

Where can I get more information? 36

Resources from the federal government 36

Administration for Community Living 36

Alzheimer’s and related Dementias Education and Referral (ADEAR) Center 36

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 36

U.S. Department of Veteran’s Affairs 37

Resources from non-profits and other organizations 37

American Hospital Association 37

Center for Practical Bioethics 37

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization 38

This book will help you learn about advance care planning and how to put a plan in place for your future care needs. You will learn:

What advance care planning is and how it can help you,

How to get your affairs in order and who to involve, and

How to make your decisions official.

You will also find worksheets, conversation guides, and other tools to help you plan. This book can help you prepare and plan for your own care or you can use it to help someone you know.

If you are not ready to start working on your plan right now, decide on a day and time to come back to this book.

Chapter 1: What is advance care planning?

After a severe heart attack, Roger was on life support. The medical team asked his wife, Donna, and two adult sons, Anton and Mike, if they wanted to continue life support. They had never discussed with Roger what he would want in a situation like this. Without knowing his wishes, they debated and agonized for days. Donna and Anton were still hopeful something could change. Mike, however, was certain that his father would never want to spend his life like this. He could not bear to see him in the hospital. Eventually a brain scan showed that Roger was unlikely to recover, and the family made the difficult decision to withdraw life support. Even after the funeral, Donna and Anton questioned if there was something more they could have done, while Mike wondered if they should have withdrawn life support sooner.

Advance care planning is about sharing what matters most to you with your loved ones and health care providers. Talking about your wishes will help ensure your decisions about medical care will be understood and respected if you become seriously ill or are unable to communicate your wishes. Having meaningful conversations with loved ones is the most important part of advance care planning.

Without these conversations, it will be more difficult for your family and health care team to make decisions about your care if you are unable to make them for yourself. If you’ve never talked about what you want, how will they know? Many people assume their loved ones know what they would want. However, research suggests that this is not always true. When participants in a research study were asked to guess which end of life decisions their loved one would make, they guessed nearly one in three decisions incorrectly. It is not uncommon to hear stories about families feeling deeply conflicted or even being torn apart over whether they made the right decision for their loved one. Even though it’s tough to have these conversations now, discussing the care you would want will make it easier on your loved ones in the future.

What does advance care planning cover?

To make your wishes official, you can develop an advance directive. An advance directive is a legal document that provides instructions for medical care and only goes into effect if you cannot communicate your own wishes. For example, because of an emergency or at the end of life. The goal is to ensure that your family and doctors understand your values, goals, and preferences, and could make decisions that reflect what you would want. Typically, an advance directive includes two legal documents:

A living will, which lists decisions about treatments that may help you live longer, sometimes called life-sustaining treatments.

A durable power of attorney for health care, which identifies a person—sometimes called a health care proxy or health care agent—to make decisions for you if you are unable to communicate your wishes yourself.

These documents should be updated as your life changes. You can update it at any time, but plan to review your plan at least once a year and after major life events like a divorce, death, retirement, moving out of state, or a change in your health.

[BOX BEGINS]

Words to Know

Word |

Definition |

Advance directive |

Instructions for your medical care that only go into effect if you cannot communicate. An advance directive usually includes instructions for your wishes (living will) and names a person to make decisions about your medical care (health care proxy). |

Living will |

A legal document that lists decisions about treatments that may help you live longer, sometimes called life-sustaining treatments. |

Durable power of attorney for health care |

A legal document used to name someone who can make health care decisions for you if you are unable to communicate. This person may also be called your health care proxy. The document may also identify an alternative proxy, and it may provide special instructions or limits for your health care proxies. The term “health care proxy” may also be used to refer to this document. |

[BOX ENDS]

Why do I need advance care planning?

People of all ages can benefit from advance care planning (ACP). It can help your loved ones and health care providers better understand and carry out your wishes if you are too sick to communicate. This could happen due to a disease or severe injury—at any age. It’s especially important if you have been diagnosed with a condition, like Alzheimer’s disease, that may affect your ability to clearly think, learn, and remember (known as cognitive health).

Without ACP, you may be less likely to get the care you want. Many people receive health care that does not match their preferences because those preferences are not communicated clearly. Studies show that ACP can make a difference. When people document their wishes, they are more likely to get the care they prefer at the end of life.

It’s common to need more help making decisions about health care as we get older. One study found that half of all adults age 65 or older who are admitted to a hospital had someone else involved in making their medical decisions. If you have an advance directive in place and updated regularly, someone you trust will be able to make decisions on your behalf if you are not able to do so.

Advance care planning can help your loved ones, especially during a stressful time like an emergency or recent diagnosis. Having meaningful conversations about end-of-life care can help reduce burden on your loved ones and help them feel less guilt, reduce depression, and have an easier time grieving. Sharing your wishes in advance and identifying a health care proxy can make life a little easier on your family and save them from wondering if they made the right decisions for you.

[BOX BEGINS]

Advance care planning for people with dementia

Many people do not realize that Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias are terminal conditions and ultimately result in death. People in the later stages of dementia often lose their ability to do the simplest tasks. Dementia can also progress unpredictably. Some people may lose their ability to make decisions earlier than anticipated. Understanding how the disease progresses can help you and your family prepare for some of the care decisions that you may need to make in the future.

If you have dementia, advance care planning can give you a sense of control over an uncertain future and allow you to participate directly in decision-making about your future care. If you are a caregiver of someone in the later stages of dementia, thinking about and discussing advance care planning decisions with your family, your loved one’s health care provider, or a trusted friend may help you plan and feel more supported when deciding the types of care and treatments your loved one would want.

[BOX ENDS]

[BOX BEGINS]

What’s standing in your way?

Explore common reasons people may have for not beginning advance care planning or putting an advance directive in place.

“I don’t need to do it right now.” – Amir, Age 45, Madison, WI

Even if you are perfectly healthy, you can experience unanticipated events, like a car accident, that could leave you unable to speak for yourself. Advance care planning now helps ensure that you’re not making decisions during a stressful time, like a medical emergency. It also gives you the ability to choose who will make decisions on your behalf if you are not able to.

“I don’t want to sign my life away.” – Harold, Age 64, Hattiesburg, MS

Advance directives and living wills only go into effect if you become unable to communicate your wishes. You also have the power to change your plans at any time. By discussing your wishes now, you can help your loved ones and doctors make decisions about your care and treatment in line with what you would want if you could not communicate them yourself.“I worry I won’t get the treatment I need.” – Diedre, Age 72, Houston, TX

With advance care planning, you are the one who decides what treatment you want to receive. It allows you to make it clear exactly what care you do and do not want if you are unable to communicate. You can state that you want treatment that will help extend your life or you could state that you only want treatments that will make you comfortable.“My doctor should be the one to bring up advance care planning.” – Aiyana, Age 57, Albuquerque, NM

You might prefer that your doctor starts the conversation about advance care planning, but, if they do not bring it up, it’s okay to ask about it. That way, you can learn about care and treatment decisions and make your wishes known. Talking with your doctor about advance care planning is covered by Medicare as part of your annual wellness visit.“It’s best if my family decides the care I need.” – Kiera, Age 72, Columbus, OH

You can have ask certain members of your family to make decisions for you. However, without a specific legal document that says this, they may not have the legal authority to communicate your wishes to your health care team. Advance directives give your family a set of tools to work from when making decisions about your care. You can also specify that your proxy speak with certain people, like other family members or a spiritual leader, before making health care decisions.“I don’t want to talk about death or dying with my family. It’s too difficult to have this conversation.” – Xavier, Age 63, Modesto, CA

It’s true that advance care planning conversations may be difficult for you and your loved ones. Yet, for many people find that these conversations create a sense of empowerment, help them learn more about themselves and their life situation, and bring them closer to their family members. You do not have to discuss specific treatments or care decisions right away. Instead, you can talk about what matters most to you and what makes life meaningful. You can also talk about who you trust to make medical decisions for you. You might try other ways to share your wishes with family like writing a letter about what matters to you. Or starting the conversation by playing a game, walking through this conversation guide together, or watching a video.

“I don’t want to go against my doctor’s wishes.” – Li Mei, Age 54, Chicago, IL

Doctors want to do what is best for their patients, but they often have to make difficult decisions with limited information. Your doctor will appreciate any information you can provide about the care you would want if you were unable to communicate your wishes. Talking with your doctor about your health care preferences helps them to do their job.

[BOX END]

What happens if I do not have an advance directive?

At 42, Erica was a marathon runner in excellent health. She never imagined needing an advance directive and had never talked to her loved ones or her partner of five years, Akimi, about future medical or end-of-life care. Erica trusted Akimi with her life; there was no one who knew her better. In 2020, Erica became seriously ill with COVID-19 and was hospitalized. For weeks, she was unable to make decisions about her care, and was put on a ventilator. Erica did not have a living will or durable power of attorney for health care in place, so Akimi could not make any decisions about Erica’s care. Instead her closest family member, her mother, was left to make decisions for her. Erica had not talked to her mother in years, and they had very different beliefs when it came to medical care. Thankfully, Erika recovered. She realized that in the future, she wanted Akimi to have the power to make medical decisions for her. She created an advance directive to make her wishes clear and named Akimi as her health care proxy.

It is impossible to predict the future. You may never face a medical situation where you are unable to communicate your wishes. But having an advance directive can give you and those close to you some peace of mind.

If you do not have an advance directive and you are unable to make care decisions on your own, the state laws where you live will determine who may make medical decisions on your behalf. This is typically your spouse, your parents if they are available, or your children if they are adults. If you have no family members, some states allow a close friend who is familiar with your values to help. Or they may assign a physician to represent your best interests.

Always remember: an advance directive is only used if you are not able to make those decisions on your own.

Will having an advance directive guarantee that my wishes are followed?

An advance directive is legally recognized, but it is not legally binding. This means that your health care provider and proxy will do their best to respect your advance directive, but there may be certain situations where they cannot follow your wishes exactly. For example, you may be in a complex medical situation where it is unclear what you would want. This is why having the conversations about advance care planning are so important. If a medical situation does not match exactly what your advance directive says, the people you have spoken to about your wishes and preferences may know what you would have wanted in that situation.

In some emergency situations, it may not be possible for the health care team to know your wishes before delivering care. For example, if you have a sudden heart attack and need an ambulance, it’s unlikely that health professionals will be able to locate your advance directive or health care proxy before providing emergency care. For these types of situations, you can talk to your doctor about establishing out-of-hospital Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) orders or portable medical orders called Physician’s Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST), Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST), or similarly named orders. These easy-to-find forms can help make your treatment wishes clear to health professionals during a medical emergency. In contrast, an advance directive often helps guide treatment after a medical emergency. These forms are discussed further in Chapter 3.

Finally, there is the possibility that a health care provider refuses to follow your advance directive. This might happen if the decision goes against:

The health care provider’s conscience.

The health care institution’s policy.

Accepted health care standards.

In these situations, the health care provider must tell your health care proxy right away and can help transfer your care to another provider. It’s important to create an advance directive and discuss it with your proxy and your provider in advance to be sure they support and understand your wishes.

Chapter 2: How do I start advance care planning?

Nothing was more important to Rosa than her family. When she was diagnosed with cancer, she told her doctor and her family that she wanted to do whatever it takes to be able to see her granddaughter’s college graduation, even if treatments would make her very sick. She decided on an aggressive treatment that allowed her to attend the graduation. Afterwards, she asked to stop treatment and return home to spend her final days surrounded by family.

Advance care planning starts with you. This chapter is designed to help you reflect on your values. You will find questions to help you think about what makes life meaningful to you and what’s important to you. You may not know the answer to every question right now, but thinking about each question can help prepare you to start the conversation with your loved ones and health care providers.

Keep in mind that everyone approaches advance care planning differently. You or your loved ones may not be comfortable talking about death or the possibility of a serious illness. You may not trust the health care system, or you may worry about not getting enough care. Remember to be flexible and take it one step at a time. You do not have to make every decision in one sitting. Start small. For example, try simply talking with your loved ones about what you value and enjoy most about life. Your values, treatment preferences, and even the people you involve in your plan may change. The most important part is to start the conversation.

Think about what matters most in life

What do you value? What matters most to you and makes your life meaningful may affect the kind of medical care you would want. Here are some questions to help you think about what matters most to you. Write down your thoughts:

What does a good day look like for you?

Some ideas: Is it time with family or friends? Enjoying certain activities? What do you most enjoy in life?

[TEXT BOX]

Finish this sentence: What matters most to me through the end of my life is…

Some ideas: Being able to recognize my children; being independent; spending time with the ones I love; helping others.

[TEXT BOX]

Is there a point in life where you would not want to keep living?

For example, if you were not able to do certain things, like breathe on your own or feed yourself?

[TEXT BOX]

What qualities are important in a person making health decisions for you?

Some ideas: Is it someone who can work well with other family members? Someone who has a similar cultural background?

[TEXT BOX]

What religious or spiritual beliefs affect the types of care you want?

For example, is it important to have a religious leader involved in certain care decisions? What should loved ones know about the spiritual or religious part of your life?

[TEXT BOX]

Think about what matters most when making medical decisions

For some people, staying alive as long as medically possible, or long enough to see an important event like a grandchild’s birth, is the most important thing. Advance care planning can help make that possible. Others have a clear idea about when they would no longer want to prolong their life. An advance directive can help with that, too. You might think about things like:

If you are seriously ill or nearing the end of life, how much medical treatment would you feel was right for you?

For example, would you want to try every available treatment even if it’s uncomfortable or painful, or would you want to avoid treatments that may impact your quality of life?

[TEXT BOX]

Would you rather live as long as possible or focus on quality of life?

For example, is it more important to live longer or would you rather focus on being able to function physically or mentally even if you may not live as long?

[TEXT BOX]

Who do you trust to make decisions about you care?

For example, would you like to leave decisions up to your health care provider? Or a member of your family or community?

[TEXT BOX]

What worries you most about your future health care needs? The end of life?

For example, are you concerned about finances, feeling like a burden, mending broken relationships, staying home as long as possible?

[TEXT BOX]

What does a “good death” mean to you?

For example, would you like to die at home with family around you? Would you like to avoid pain? Are there other important things like having prayers read or certain music played?

[TEXT BOX]

Your decisions about how to handle any of these situations could be different at age 40 than at age 85. Or they could be different if you have a chronic condition compared to being generally healthy. An advance directive allows you to provide instructions for these types of situations. You can adjust the instructions as you get older or if your viewpoint changes.

Chapter 3: How do I make a living will?

Although Kamal rarely went to mosque or talked about his faith, he always felt deeply connected to his Muslim upbringing, especially when thinking about big events in life, like birth, marriage, and death. In his advance directive, he made it clear that he wanted his faith to be paramount when it came to making decisions at the end of his life. He named his brother as his health care proxy and asked that he discuss decisions with the whole family as well as the imam, the leader at his mosque. He also made certain decisions very clear in his living will. For example, if doctors agreed that death was inevitable, he would want to stop treatment. As he progressed into the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease, having this information and the help of the imam made it easier for his family members to make hard decisions.

Once you have reflected on the things you value most, start thinking about your living will. A living will is a written document that tells doctors how you want to be treated if you are dying or permanently unconscious and cannot make your own decisions about emergency treatment. It allows you to make clear which treatments you would or would not want and under which conditions each of your choices applies. This section will walk you through the first steps of creating a living will, including:

Learning about the care and treatment decisions covered by a living will.

Talking about your current health and care options with your health care team.

[BOX BEGIN]

How is a living will different from a will?

A living will provides legal guidance about what you want to happen if you are too sick to make your own decisions. This may include decisions about your care and treatments, your health care providers, and where you might receive care.

A will provides legal guidance about how a person’s estate — their property, money, and other financial assets — will be distributed and managed when they die. It may also address care for a child or adult dependent, gifts, and end-of-life arrangements, such as the funeral and burial.

[BOX END]

Learn about common care and treatment decisions.

Sometimes decisions must be made about the use of emergency treatments to keep you alive. Doctors can use several artificial or mechanical ways to try to do this. For example, if someone has a life-threatening condition, their heart may stop beating, and a provider may try CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) to keep the person alive. In a situation like this, some people may decide that they would or would not want CPR. A living will allows you to make it clear which treatments you would or would not want.

Learn about common, life-sustaining medical treatments.

Take some time to think about the types of care and treatments you may need. Are there certain things you would or would not want if you were seriously ill or dying? You can start by learning about common, life-sustaining medical treatments that may be covered in living wills:

CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation): If your heart stops, you may be given CPR, which involves repeatedly pushing on the chest to keep blood moving to your vital organs, while putting air into the lungs. The force can sometimes break a person’s ribs. Electric shocks, known as defibrillation, and medicines might also be used as part of the process. The heart of a young, otherwise healthy person might resume beating normally after CPR. CPR is less likely to work in people who are older or who have chronic medical conditions.

Ventilators: If are not able to breathe adequately, you may need a ventilator, a machine that uses a tube to force air into the lungs and help a person breathe. Putting the tube down the throat is called intubation. Intubation can be very uncomfortable, so medicine is often used to keep the person sedated. If expected to remain on a ventilator for a long time, a doctor may insert the tube directly into the trachea (a part of the throat) through a hole in the neck. This is called a tracheotomy. For long-term help with breathing, this procedure makes it more comfortable and sedation is not needed. People who have had a tracheotomy need additional help to speak.

Artificial nutrition and artificial hydration (tube feeding and IV (intravenous) fluids): If you are not able to eat or drink, fluid and nutrients may be delivered into a vein through an IV or through a feeding tube. A feeding tube that is needed for a short amount of time goes through the nose and esophagus into your stomach. If a feeding tube is needed for a long period of time, it is inserted directly into your stomach through your abdomen. This may help if you are recovering from an illness. However, studies have shown that having a feeding tube toward the end of life does not meaningfully prolong life. If the person’s body cannot use the nutrients properly, a feeding tube may even be harmful. Among people with dementia who are having difficulty eating, some research suggests that careful hand feeding (sometimes called assisted oral feeding) may be more comfortable and reduce the chance of harm from tube feeding.

If you become terminally ill, meaning you are unlikely to recover from your illness and will eventually die, these treatments are unlikely to help you get better and may prolong the dying process.

[BOX BEGINS]

What would you choose?

Consider these situations and write down what you would choose. Remember: you feel differently as time goes on.

If an illness leaves you paralyzed or in a permanent coma and you need to be on a ventilator, would you want that?

[TEXT BOX]

If your heart stops or you have trouble breathing, would you want to undergo life-saving measures if it meant that, in the future, you could be well enough to spend time with your family?

[TEXT BOX]

If a stroke leaves you unable to move and then your heart stops, would you want to be given CPR? If the stroke also affected your thinking, does that change your decision?

[TEXT BOX]

What if you are in pain at the end of life? Do you want medication to treat the pain, even if it will make you drowsy and tired?

[TEXT BOX]

What if you are permanently unconscious and then develop pneumonia? Would you want antibiotics? To be placed on a ventilator?

[TEXT BOX]

If you were at the end of life and dying, would you prefer to spend your last days in a health care facility – like a hospital – or would you prefer to spend your last days at home?

[TEXT BOX]

[BOX END]

Doctor’s orders for future medical or end-of-life care decisions and forms.

There are other medical or end-of-life care decisions that may come up. To make your wishes clear, you may need to state your wishes in a living will and have doctor’s orders, (special forms that you complete with your doctor). Doctor’s orders make it much more likely that your wishes will be carried out, even in emergency situations. For example:

Do not resuscitate (DNR) order. If your heart stops beating or you stop breathing, medical staff typically make every effort to restore your heartbeat and breathing. A DNR order is a document that tells health care professionals not to perform CPR in case your heart stops beating or your breathing stops. Sometimes this document is referred to as a DNAR (do not attempt resuscitation) or an AND (allow natural death) order. Posting a DNR next to your hospital bed helps avoid confusion in an emergency. If you live at home, you may also consider a non-hospital or out-of-hospital DNR order. This order alerts emergency medical personnel to your wishes regarding measures to restore your heartbeat or breathing if you are outside a hospital setting. Ask your doctor about creating a DNR order and how to get it in the form of a wallet card, bracelet, or other document to have with you all the time.

Do not intubate (DNI) order. A DNI is a document that lets medical staff in a hospital or nursing facility know that you do not want to be put on a ventilator. Ask your doctor about completing a DNI order.

Physician's Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST), Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST), or Physician Orders for Scope of treatment (POST). POLST/MOLST/POST provide a doctor’s orders for your medical care preferences about CPR, intubation, and other types of treatment. Typically, these forms are used only when you are seriously ill or near the end of life. These forms serve as a medical order in addition to your advance directive. They make it possible for you to provide guidance that health care professionals can act on immediately in an emergency. All states and the District of Columbia have some level of POLST/MOLST/POST. The doctor fills out a POLST/MOLST/POST after discussing your wishes with you and your family. Once signed by your doctor, this form has the same authority as any other medical order. Check with your state department of health to find out if these forms are available in your state.

Learn about other future medical or end-of-life care decisions and forms.

There are other medical or end-of-life care decisions that may come up. To make your wishes clear, you may need to state your wishes in a living will and complete other forms. For example:

Organ and tissue donation. Organ and tissue donation allows organs or body parts from a person who has died to be donated to people who need them. The heart, lungs, pancreas, kidneys, corneas, liver, and skin may be donated. There is no age limit for organ and tissue donation. Once you become an organ donor, you can carry a donation card in your wallet. Some states allow you to add your organ donation status to your driver’s license. You should also state your wishes about organ donation in your living will. Sign up to become an organ donor by visiting www.organdonor.gov or by visiting your state or local motor vehicle office.

Brain donation. Brain donation helps researchers study brain disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, that affect millions of people. While many people think that signing up to be an organ donor includes donating their brain, the purpose and the process of brain donation are different. Rather than helping to keep others alive, brain donation helps advance scientific research. If you decide to donate your brain, consider contacting an NIA-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center to enroll in a study. Another way to become a brain donor is to pre-register with the Brain Donor Project (https://braindonorproject.org/). Similar to organ donation, you should state your wishes about organ donation in your living will.

Pacemakers and Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICDs). Some people have pacemakers to help their hearts beat regularly. If you have one and are near death, it may not necessarily keep you alive. Some people might have an ICD (implantable cardioverter-defibrillator) that shocks the heart if the rhythm becomes irregular. These shocks can be uncomfortable. If you have an ICD and you do not want life-sustaining treatments like CPR or intubation, you may also want your ICD to be turned off. You need to state in your living will what you want done if the doctor suggests it is time to turn it off.

Learn about other care options.

You can consider the types of care you might want as you age. This may include care or support for everyday activities as well as palliative care and hospice care. Learning about these options can help you plan ahead.

Palliative care. Palliative care is medical care that focuses on relieving the symptoms of serious illnesses, such as cancer, dementia, or heart failure. Patients work with a medical care team and continue to receive treatment for their illness. Palliative care can be helpful at any stage of illness and is best provided soon after a person is diagnosed. In addition to improving quality of life and helping with symptoms, it can help patients understand their choices for medical treatment. Palliative care can be provided in hospitals, nursing homes, outpatient palliative care clinics and certain other specialized clinics, or at home.

Hospice care. Hospice care focuses on the care, comfort, and quality of life of a person approaching the end of life. At some point, it may not be possible to cure a serious illness, or a patient may choose not to undergo further treatments intended to prolong life. Like palliative care, hospice provides comprehensive comfort care as well as support for the family. But, in hospice care, attempts to cure the person's illness are stopped. Hospice care is available when a person’s doctor believes he or she has limited time to live if the illness runs its natural course, typically six months or less. It can be offered at home or in a facility such as a nursing home, hospital, or even in a dedicated hospice center. Starting hospice early may help provide more meaningful care and quality time with loved ones.

[BOX

BEGINS]

Comfort

care

You may also hear the term comfort care when developing your living will. Comfort care is sometimes used to mean palliative care without other care that is intended to cure disease or prolong life. If treatment is no longer likely to help, medication or other care is provided to help soothe and relieve suffering. Comfort care includes managing shortness of breath; limiting medical testing; providing spiritual and emotional counseling; and giving medication for pain, anxiety, nausea, or constipation.

[BOX ENDS]

Providing end of life care at home can be a big job for family and friends—physically, emotionally, and financially. But, there are benefits too. Frequently, this care does not require a nurse but can be provided by nursing assistants or family and friends without medical training. However, hiring a home nurse may be an option for people who need additional help and have the financial resources.

A doctor must oversee care at home. Talk with your health care provider about the kind of care needed, how to arrange for services, and how to get any special equipment you may need. Health insurance might only cover these services or equipment if they have been ordered by a doctor; check with your insurance company before ordering.

Talk with your doctor about your current health and care options.

Now that you have learned about common treatments covered in a living will, the next step is to talk with your doctor. Your doctor can help you learn more about your current health and better understand the care and treatment decisions that may be needed as you get older or in an emergency. These conversations are also important because your doctor, along with your health care proxy, is part of your care team. When your doctor knows what matters most to you, they can help you get the care you want.

Conversations with your doctor about advance care planning are covered by Medicare as part of your yearly wellness visit. Medicare may also cover this service as part of your medical treatment. If you have private health insurance, check with your insurance provider to see if they cover advance care planning discussions. You may be able to have these conversations in person, over the phone, or over the internet depending on your doctor and what is most comfortable for you.

Some people may find it difficult to ask their doctor directly about their current prognosis or end-of-life care. Preparing for your appointment can help. You can find tips on how to prepare for an appointment and talk with your doctor by reading NIA’s Talking With Your Doctor: A Guide for Older People. If it makes you more comfortable, ask your health care proxy to come to your appointment with you. In some cases, you could even have your proxy speak directly with your doctor.

Who on my health care team should I talk to about my advance care plan?

Choose someone you’re comfortable talking with. Your health care team might include doctors, nurses, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and others—like a social worker. Many people choose to discuss advance care planning with their primary care provider or geriatrician. You might also decide to talk to more than one health care provider. For example, you may see a nurse practitioner for your regular medical care as well as a specialist for a certain condition, like kidney disease. If you don’t have a health care provider, now may be a good time to find a new doctor. You can learn more about choosing a doctor on the NIA website.

Use the table below to write down the health care providers you see each year.

What is the name of your health care provider? |

What is their phone number? |

What do you see them for? |

When is your next appointment? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tips for talking with your doctor about advance care planning

Ready to talk to your doctor? Read these tips and conversation starters to help you make the most out of your visit. You will also find examples of questions you might ask during your appointment. You may decide that not all the questions are important to you. Or you may not be ready to talk about all of these things right now. That’s okay. The important thing is to start the conversation.

Before your visit

You can prepare for your visit by writing down some of your current health issues and your questions about future health care and end-of-life care. Remember, the goal is simply to start the conversation. You do not have to make specific decisions about your medical care until you feel ready.

How would you describe your current health? What illnesses or conditions do you have right now? If you don’t have any medical issues now, your family medical history might be a clue to help you think about the future.

[Text]

What concerns or questions do you have about your future health or health care?

[Text]

What concerns or questions do you have about end-of-life care?

[Text]

Circle the medical treatments you would like to discuss further with your health care provider.

CPR

Ventilator use

Artificial nutrition and artificial hydration

Comfort care

Do not resuscitate orders

POLST/MOLST/POST forms

Organ and tissue donation

Brain donation

Pacemakers and ICDs

Other tips before your visit:

Decide if you would like someone to join you for your visit. If you have a more advanced condition, it may be best to include your health care proxy or someone else you trust when talking to your doctor about your wishes. You can even ask them to take notes. Your doctor may ask you to sign a release form before sharing information about your health with someone else.

Call or email in advance. Let your doctor know that you would like to discuss advance care planning during your appointment. You might say, “Could you please tell the doctor that I’d like to talk about my advance directive at my appointment?”

Ask for an interpreter, if needed: If you need an interpreter, email or call your doctor in advance to let them know.

Bring this booklet and worksheet. This can help guide your conversation and prioritize what you most want to discuss.

Bring any forms you’ve started or completed. If you’ve decided on your health care proxy, bring their contact information.

During your visit

Start the conversation. Here are some examples of ways to start the conversation during your appointment:

“I want to talk about my goals for care and living with my serious illness.”

“I want to have a conversation about my wishes for end-of-life care.”

“I’ve been thinking a lot about my health. I’d like to talk more about what to expect in the years ahead and how I can prepare myself and my family for future medical decisions.”

Talk about your current health and share what matters to you. If you have a health condition, like diabetes, heart disease, cancer, or Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia, talk with your doctor about your condition and how it might progress. If you don’t have any medical issues right now, talk with your doctor about decisions that might come up if you develop health problems that may run in your family. For example, you might ask:

How serious is my illness or condition?

[Text]

How might this condition worsen other conditions I have?

[Text]

What types of treatment or changes to my daily life should I expect in the coming weeks, months, or years?

[Text]

What can I expect from this course of treatment? What are my other choices? What can I expect if I decide to do nothing?

[Text]

Will I be able to continue to live independently?

[Text]

What types of treatment or care would you recommend if your own family member had this condition?

[Text]

Share what’s most important to you. You might have certain events you want to attend. Or you may have an idea of care you do or do not want based on your experiences with someone close to you. If you feel comfortable, you might choose to share what you wrote down in Chapter 2. Here are examples of things you might say:

Sharing what is important to you: “What matters most to me is _____.”

Sharing an important event: “My granddaughter is having her first child later this year and I’d really like to meet the baby. Can you help me understand what I might need to do to see that happen?”

Sharing a loved one’s experience: “My mother-in-law was diagnosed with cancer and no one understood how quickly it would progress. I want you to be open with me and let me know your best estimate for how much time I have left.”

Make sure you have all the information you need. It’s okay to ask your doctor questions even if it feels uncomfortable. You can also ask your doctor to write down what you’ve discussed so you can think about it further or share it with your loved ones. You might ask your doctor to:

Clarify something: “I didn’t understand what you meant by ______. Can you explain it in a different way?”

Write down what you’ve discussed: “Would you write this down for me? I want to be sure I understand what we’ve discussed, and I’d like to be clear when I share this information with my loved ones.”

Document your discussion in your medical record: “Will you write down what we’ve discussed today and put my wishes in my medical record?” You can also ask your doctor to give you a copy of what they wrote down and share it with loved ones.

Before you go, don’t forget to share important documents. If you’ve decided on your proxy, share their name and contact information. If you’ve already created parts of your advance directive, share that as well.

Remember, you don’t have to decide everything right away. You can tell your doctor that you’d like to think about what you’ve discussed and ask to set-up an appointment to have another conversation in a couple of weeks.

After your visit

Your wishes may change over time. Plan to talk to your doctor about your advance directive at least once a year and after major life changes like a divorce, death, or a diagnosis. When you complete your advance directive forms, remember to give your health care provider a copy. You can bring them to the office, or you may be able to submit them via your electronic health record.

Make Your Living Will Official

A living will is commonly part of the advance directive forms available for free in each state. Go to Chapter 5 to learn where to find your form and how to make your living will official.

Chapter 4: How do I choose a health care proxy?

You can choose a person to make medical decisions for you if you are unable to communicate them yourself. This person is called a health care proxy. This section will help you navigate important questions about your health care proxy, like:

What is a health care proxy and what decisions can they make?

Who would be the best health care proxy for me?

How do I ask someone to be my health care proxy?

How do I talk to others about my decisions?

[BOX BEGINS]

Words to Know

Word |

Definition |

Health care proxy (or proxy) |

A person who can make medical decisions for you if you are unable to communicate. Other terms may also be used, such as health care agent, surrogate, representative, or power of attorney for health care. |

Alternate proxy |

A second person you name who can make medical decisions for you if your health care proxy is not available. The term back-up agent may also be used. |

Durable power of attorney for health care |

A legal document used to name your health care proxy, name an alternative proxy, and provide special instructions or limits for your health care proxy. The term health care proxy may also be used to refer to this document. |

[BOX ENDS]

What is a health care proxy and what decisions can they make?

If you become seriously ill and cannot make decisions for yourself, your health care proxy can make health care decisions for you. Here are some important things to know about choosing a health care proxy:

Your proxy can only make decisions for you if you are too sick to make them yourself.

You can choose which decisions you want your health care proxy to make and which decisions you want your doctor to make.

It’s okay to change your health care proxy—just fill out a new proxy form and let your family and health care team know about the change.

You may name an alternate proxy if your proxy is unavailable for any reason.

You can choose a proxy in addition to or instead of a having a living will. Having a health care proxy can help you plan for unexpected situations like a serious car accident. If you choose not to name a proxy, it is especially important to have a detailed living will.

Common responsibilities of a health care proxy

You can specify how much say your proxy has over your medical care, including whether he or she can make a wide range of decisions or only a few specific ones. While every state has different forms, these are commonly included in a durable power of attorney for health care:

Deciding the types of medical care, procedures, treatments, or services you receive. For example, whether to use a feeding tube or have a feeding tube removed.

Identifying where you will receive care and your health care providers. For example, if you will receive care at a hospital, psychiatric treatment facility, or nursing home.

Overseeing information about your physical or mental health and your personal affairs, including medical and hospital records.

Making decisions about autopsy, tissue and organ donation, and what happens to your body after death.

Becoming your guardian if one is needed.

You can specify if you do not want your proxy to be able to make certain decisions. You may also add other preferences you have for your proxy on the form. For example, you can require them to talk with certain family members before making a decision. However, it’s important to give your health care proxy some flexibility to ensure they can give you the best care possible. For example, it may not always be possible to be cared for at home until you die, even if that is your wish.

Whom should I choose as my health care proxy?

Think carefully about the person you choose to be your health care proxy. It does not have to be a family member. For example, you might ask a close friend, lawyer, or someone in your social or spiritual community to be your health care proxy.

[BOX BEGINS]

Whom should I consider to be my health care proxy?

Here are some people you might consider:

Parent

Spouse / Partner

Child

Sibling

Other relative, like a cousin or niece

Friend

Trusted neighbor

Someone from your place of worship

Lawyer

[BOX ENDS]

Your health care proxy should be age 18 or older and be of sound mind. However, in Alabama and Nebraska, a proxy must be age 19 or older. There may be people in your life whom you love, but who may not be the right proxy for you. For example, you may decide it would be too painful for a certain person in your life – like a parent – to make decisions that reflect your wishes. While state requirements vary greatly, the American Bar Association generally recommends not choosing:

Your health care provider or their spouse, employee, or spouse of an employee.

The owner or operator of your health or residential care facility or someone working for a government agency financially responsible for your care.

A professional evaluating your ability to make decisions.

Your court-appointed guardian or conservator.

Someone who serves as a health care proxy for 10 or more other people

Be sure to check your state’s rules to find out if there are any other limitations on who can be your proxy.

[WORKSHEET BEGINS]

Who should I choose as my health care proxy?

Write down the names of three people you think would a good fit.

[Text Box]

List each name in the table and read each question. Check a box under each name if you answered yes to that question.

-

Questions

Person 1:

Person 2:

Person 3:

Am I comfortable talking with this person about my wishes and priorities for health care?

Will this person honor my wishes, and do as I ask when the time comes?

Do I trust this person with my life?

Can this person handle conflicting opinions from my family, friends, and health care providers?

Is this person comfortable asking questions of doctors, insurance companies, and other busy providers and will stand up for me?

Does this person live near me or would he or she travel to be with me, if needed?

If more than one person seems like a good fit to be your health care proxy, you could choose one as your primary health care proxy and the other as your back-up or alternate proxy.

[WORKSHEET ENDS]

How do I ask someone to be my health care proxy?

Once you’ve identified someone you would like to serve as your proxy and alternate proxy, ask them if they are willing to take on the responsibility and share your wishes with them. Here are some tips for asking someone to be your health care proxy:

Prepare for the conversation.

It’s okay to feel uncomfortable or emotional. Although it may push you out of your comfort zone, having this conversation will help you and your loved ones in the future. You may also find that you feel closer to the person after discussing these important decisions with them.

Decide on a conversation starter that works for you. If it makes you feel more comfortable, you might start by writing a letter, watching a video with the person, or making a video of yourself talking about your wishes. You can also search online for games designed to help discuss advance care planning.

Understand that the person may say no. Serving as someone’s proxy is a big responsibility. Some people may say no because they feel they cannot honor your wishes or that it would be too stressful to make medical decisions on your behalf. Some people may need time to think about it. That’s okay. The important thing is to ask, listen, answer their questions, and let them decide.

Bring this workbook and any advance care planning documents with you. Use them as a resource to explain what it means to be a proxy and share what matters most to you.

Start the conversation.

Here are some things you might say:

“This isn’t easy to talk about, but I’d like you to make my medical decisions if I’m too sick to speak for myself. I’d like to tell you more about what that means. Is that okay?”

“I’d like you to be my health care proxy. That means you would make medical decisions for me if I couldn’t make them for myself. Is this something you would be comfortable doing?”

Tell them what it means to be a proxy:

“As my proxy, if I am unable to speak for myself, you will be the one to make medical decisions for me. This might include:

Talking to my doctors and making decisions about my care, procedures, treatments, or services.

Asking questions and advocating for me.

Communicating to my loved ones — even if they don’t agree with certain decisions.”

“I need my proxy to understand what’s important to me when making decisions about my care. I’d like to share that with you and talk about what’s in my living will.” At this point you might walk them through your living will or some of the things you’ve written down in this workbook.

Consider sharing Chapter 7 of this workbook with the person. The chapter covers what it means to be someone’s health care proxy and offers tips to help them in their role.

Make sure your proxy has the right information:

After they agree to be your proxy, give them a copy of the signed durable power of attorney for health care form, your living will, and any other forms you think they may need.

Make sure your proxy knows the names and contact information for your health care providers.

Make sure your health care provider knows the name and contact information for your proxy.

Keep the conversation going.

Your wishes may shift over time. Keep your proxy informed about any changes you make to your living will. Plan to talk to your proxy at least once a year about your wishes.

You can choose to change your proxy at any time. Be sure to notify the person and your health care providers if you’ve decided to make a change.

You may want to talk to more than one person about your wishes before deciding who is the right proxy for you. Whomever you choose, be sure to share what you decide with your loved ones.

How do I make my health care proxy official?

Once you decide on your health care proxy and have talked about your care goals and wishes with them, you can make it official by completing a durable power of attorney for health care. This legal document is used to:

Name your health care proxy

Name an alternate health care proxy

Provide special instructions or limits for your proxy.

Usually it is best to name only one person as health care proxy. However, the form may allow you to name an alternate proxy or back-up agent if your proxy is unable to act for any reason. You do not have to name an alternate, but it’s a good idea to do so. Make sure the proxy and alternate proxy you choose understand and are comfortable with this responsibility before you name them officially.

The durable power of attorney for health care form is often available for free. Go to Chapter 5 to learn where to find the form for your state and how to make your durable power of attorney for health care official.

Chapter 5: How to make your plans official

Ready to complete your advance directive? This section covers where to find blank forms to work through, how to get help with advance care planning, and what to do once you have completed your forms.

[BOX BEGINS]

An advance directive is a useful tool for making your decisions clear and respected. However, some people may not feel comfortable putting their wishes in writing or finalizing the official legal documents. This may be especially true for people of color where past abuses and negligence by the health care system have led to mistrust. If completing these legal documents is not the right choice for you, that’s okay. The most important part of advance care planning is to have conversations with your loved ones about what matters to you. Use this book to help guide those conversations and share your wishes.

[BOX ENDS]

[BOX BEGINS]

Steps to advance care planning:

Think about what makes life meaningful to you and who you trust to make medical decisions for you.

Talk about making an advance directive with your doctor.

Choose a health care proxy and talk about your wishes with your loved ones.

Make it official: fill out your living will and durable power of attorney for health care forms.

Share your forms with your doctor and loved ones. Keep copies in a safe place and tell people you trust where they can be found.

Keep the conversation going. Continue to talk about your wishes and update your forms at least once a year or after major life changes.

[BOX END]

Where to find your advance directive form

You can establish your advance directive for little or no cost. Many states have their own forms that you can access and complete for free. Here are some ways you can find free advance directive forms for your state:

Contact your State Attorney General’s Office.

Reach out to your local Area Agency on Aging or the Eldercare Locator. You can call the Eldercare Locator (1-800-677-1116) or visit https://eldercare.acl.gov.

Download your state’s form online from one of these national organizations: AARP, American Bar Association, or National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

If you are a veteran, contact your local Veteran’s Affairs (VA) office. The VA offers an advance directive specifically for veterans.

Some people spend a lot of time in more than one state — for example, visiting children and grandchildren. If that's your situation, consider preparing advance directives using the form for each state — and keep a copy in each place, too.

There are websites that allow you to create, download, and print your forms. There are fees for creating forms through some of these websites. Before you pay, remember there are number of ways to get your forms for free. Some free online resources include:

PREPARE for Your Care, an interactive online program that was funded in part by the National Institute on Aging. It is available in English and Spanish.

The Conversation Project, a series of online conversation guides and advance care documents available in English, Spanish, and Chinese. The Conversation Project is a public engagement initiative led by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

If you use forms from a website, check to make sure they are legally recognized in your state. You should also make sure the website is secure and will protect your information. Read the website’s privacy policy and check that the website link begins with https (make sure it has an ‘s’) and that it has a small lock icon next to the link.

How to make your advance directive form official

To make your plan official, most states require your advance directive to be witnessed. This means that there are people who watch you sign the form. Often the state requires two witnesses who are adults, and some states have additional restrictions. For example, they may not allow a family member to serve as a witness.

Some states require your signature to be notarized. A notary is a person licensed by the state to witness signatures. You might find a notary at your bank, post office, or local library, or call your insurance agent. Some notaries charge a fee. Your form will likely include directions on whether a witness or notary is needed. Check with your state if you are unsure.

What to do after you fill out your advance directive form

After you complete your advance care planning forms, make copies and store them in a safe place. If you used an online program, download and print copies, and share the password with your proxy, if applicable. Give copies of your advance directive to:

Your health care proxy and alternate proxy.

Your health care providers.

Close family members and friends.

Because you might change your advance directive in the future, it's a good idea to keep track of who receives a copy. It’s also a good idea to bring a copy with you if you go to the hospital.

Some states have registries that can store your advance directive for quick access by health care providers, your proxy, and anyone you’ve given permission to access them. Private firms also will store your advance directive. There may be a fee for storing your form in a registry. You may also be able to store copies using other tools, like a smartphone app.

If you update your forms, file and keep your previous versions. Note the date the older copy was replaced by a new one. If you store your advance directive in a registry and later make changes, you must replace the version in the registry.

[BOX / TEAR-OUT PAGE BEGIN]

Advance Directive Wallet Card

You might want to make a card to carry in your wallet indicating that you have an advance directive and where it is kept. Here is an example of the wallet card offered by the American Hospital Association. You might want to print this to fill out and carry with you. A PDF can be found online (PDF, 40 KB).

[BOX / TEAR-OUT PAGE END]

Where can I find help with advance care planning?

Here are some resources that can help with advance care planning:

Legal help: A lawyer can help, but is not required to create your advance care plan. However, you should give a copy of your advance directive to your lawyer if you have one. If you need help with planning, Area Agency on Aging officials may be able provide legal advice or help. Other possible sources of legal assistance and referral include state legal aid offices, state bar associations, and local nonprofit agencies, foundations, and social service agencies.

Multi-lingual services: If you are looking for advance care planning forms, conversation guides, or related materials in other languages, here are some places that can help:

State Attorney General’s Office or your state office of the American Bar Association.

Local Area Agency on Aging or the Eldercare Locator. You can call the Eldercare Locator (1-800-677-1116) or visit https://eldercare.acl.gov.

Who else needs to know about my advance care plan?

Other important people in your life might need to know about your plans. This might include your parent, spouse or partner, adult children, faith leader, trusted friend, social worker, or lawyer.

Maintaining your advance directive and preparing for future decisions.

Review your advance directive regularly and update documents as needed. Changes in your life like a divorce, death of a loved one, change in employment or retirement, moving, or new state laws may all affect your decisions. You should also update your documents if there are any changes to your health like a recent diagnosis. Everyone should update their plans at least once a year. Consider choosing a date every year — like New Year’s or Tax Day — to revisit your advance directive.

Chapter 6: Plan for other decisions

You might also want to prepare for other possible decisions as you age. This may include considerations around long-term care and future health care, making estate and financial plans, and planning for funeral and burial arrangements. In this section you can learn more about each of these decisions.

How to plan for long-term care

Long-term care involves a variety of services designed to meet a person's health or personal care needs. These services help people live as independently and safely as possible when they can no longer perform everyday activities on their own. Long-term care can be provided within the home or at an outside facility. At some point, a person with dementia may require around-the-clock care or exhibit behaviors, such as aggression and wandering, that make it no longer safe to stay at home. People who require help full-time can move to an assisted living, nursing home, or residential facility that provides many or all of the long-term care services they need.

When planning for long-term care, it may be helpful to think about:

Where you will live as you age and how your home can best support your needs and safety.

What services are available in the community and how much they will cost.

How far in advance you need to plan so that you can make important decisions while you are still able.

Many types of long-term care are not covered by Medicare, so planning for how to pay for long-term care is also important. You can learn more about long-term care options like assisted living, nursing homes, and more on the NIA website.

How to make a will and do financial planning for your estate

In addition to advance directives for health care, you can establish advance directives for financial planning. These forms help document and communicate your financial wishes. These must be created while you can still make decisions. Three common documents are included in a financial directive:

A will specifies how your estate — your property, money, and other assets — will be distributed and managed when you die. A will can also address care for children under age 18 and adult dependents as well as gifts and end-of-life arrangements like the funeral and burial. If you do not have a will, your estate will be distributed according to the laws in your state.

A durable power of attorney for finances names someone who will make financial decisions for you when you are not able.

A living trust names and instructs someone, called the trustee, to hold and distribute property and funds on your behalf when you are no longer able to manage your affairs.

Lawyers can help prepare these documents with you. A listing of lawyers in your area can be found on the internet, at your local library, through a local bar association, or by contacting the National Academy of Elder Law Attorneys.

How to pay for future health care.

As part of your financial planning, think about how to pay for future health care, particularly long-term care. Long-term care can be expensive, and it’s hard to predict how much care you may need – and for how long. How people pay for long-term care depends on their financial situation and the kinds of services they may need. Most rely on a variety of payment sources. This might include:

Personal funds

State and federal government healthcare programs like Medicare or Medicaid

Private financing options like long-term care insurance or life insurance.

Some employers offer long-term care insurance. Check with your human resources program to see if it is available through your employer.

You can learn more about options and resources available to help pay for future health care on the NIA website.

How to make funeral and burial arrangements in advance.

It’s possible to plan ahead and make funeral and burial arrangements for yourself. Similar to advance care planning, making your decisions known in advance can help your loved ones during a stressful time and make sure that your wishes are understood and respected. You can plan:

What kind of funeral services you would like and where they will be held. For example, some people hold both a visitation (an informal opportunity to gather in honor of the person) and a funeral (the ceremony and burial of the person who has died).

What you would like to happen to your body. For example, whether you would like your body to be buried or cremated. You can decide on a conventional burial, green burial, or if you want cremation, you can state whether you want your body’s ashes kept by loved ones or scattered in a favorite place.

Other things that are important to you. For example, you might want to specify certain religious, spiritual, or cultural traditions that you would like to have during your visitation or funeral.

You can make arrangements directly with a funeral home. Here are a few tips for planning:

Shop around. Compare prices and options at least two funeral homes and ask for a price list. Federal law requires funeral homes to give you written price lists for products and services. Every funeral home may price things differently. Find one that is willing to work with you, understands your needs, and respects your budget.

You can make arrangements in advance, but you do not have to pay in advance. Prices may change over time. Before putting any money down, get information from the Federal Trade Commission on which questions you should ask first.

Review and revise your funeral and burial plans every few years. What you want may change as you grow older. Revisiting your plans can help make sure they reflect what you would want.

Put your preferences in writing and give copies to your loved ones and lawyer. The funeral home may also keep a copy of your wishes on file. Your will may not be found or read until after the funeral, so it is important to share information on your preferred end of life arrangements with your loved ones and your lawyer if you have one.

In most states, a funeral director is not required to be involved in the care of a loved one’s body after death if there is no embalming or cremation. Families can take care of transportation, preparation of the body, filling out the necessary paperwork, and all other needed arrangements. You can learn more about the options in your state from the National Home Funeral Alliance.

Chapter 7: Advance Care Planning for Caregivers and Family Members

Navina started noticing that her mother, Padma, had a mild tremor in her hand and difficulty getting out of her chair sometimes. At first, they both thought it was just the normal signs of aging. However, eventually Padma was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

The diagnosis hit Padma hard. She prided herself on being independent and the kind of person who cared for everyone else. The idea of not being able to take care of her loved ones, let alone herself, was overwhelming. Navina tried to talk to her mother about preparing for future health care decisions, but it took a few times for Padma to feel ready. After talking about her wishes, Padma felt like she had more control over an uncertain future. She understood this was a meaningful way she could help her family when tough decisions arose down the road.

Navina was always grateful for these conversations with her mother. Knowing her mother’s wishes helped the entire family feel more confident, supported, and prepared for the decisions they faced.

As a family member or caregiver, knowing what matters most to your loved one can help you honor their wishes and give you peace of mind if they become too sick to make decisions. Starting the conversation about advance care planning can help you understand and follow their wishes. In this chapter, you can learn:

What to do if your loved one doesn’t have a plan.

How to be a health care proxy.

How to advocate for your loved one’s care.

What to do when your loved one does not have an advance directive

If your loved one is growing older or was recently diagnosed with a serious condition, it is a good idea to ask if they have an advance directive. You might ask:

“Do you have an advance directive or have you done any advance care planning?” Since there are multiple terms used, you may ask about other things like a living will or health care proxy.

If they do have an advance directive, ask them to share their plan with you and whether it needs to be updated.

Unfortunately, only one in three people in the United States has a plan in place. If your loved one does not have a plan, there are steps you can take to better understand their wishes and help them put one together. Consider working through this book together.

How to support advance care planning when the person is still able to make decisions.

Talk to the person about their wishes. It’s especially important to start the conversation early if the person has been diagnosed with a disease that affects their cognitive health, like Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. Here are some ways you might start the conversation:

“I love you and wouldn’t want to do anything you didn’t agree with. It would make me feel better if I knew what was important to you. Will you tell me what matters most to you if you were ever too sick to speak for yourself?”

“I have been wondering what you would want if you got seriously ill and couldn’t make your own medical decisions. Would you want to try aggressive treatments to live longer? Or would you rather focus on managing your symptoms and enjoying the time you have left? Who would you want to make decisions for you?”

After a movie or news story that touches on end of life issues: “What would you want us to do if you were in this situation?”

Remind them of an experience with someone at the end of life “Remember when grandma died?” Ask how they felt about it and what they would want for themselves.

Some other tips:

Start simple. Sometimes talking about specific medical treatments or decisions can be scary and overwhelming. Instead, try asking about any concerns they may have and if there is someone they trust to make decisions for them.

Share what’s important to you. Sharing what matters most to you can help get the conversation started. It can also help your loved one feel more comfortable about sharing their own preferences.

Remind them why it’s important. Talk about the benefits of having these conversations and why it can help to make an advance care plan. By sharing their wishes, they can help ensure they get the care they want. It can also help loved ones feel less guilt, reduce depression, and have an easier time grieving. You can find examples and information about the many benefits of talking about advance care planning in Chapter 1.

Try to be understanding. After a recent diagnosis or health change, it can be overwhelming and difficult to discuss future health care needs. Some people may be in denial about the seriousness of their condition. Listen and reassure them. The person may react negatively and not want to talk about it. That’s okay. You can ask if there is someone else they would feel comfortable talking with, like a family member, their doctor, or someone in their spiritual community. You can also encourage them to think about these things and that you hope to discuss it another time.