Appendix F3 Advance Material for First Concept Mapping Meeting_02142022

Appendix F3 Advance Material for First Concept Mapping Meeting_02142022.docx

Food Security Status and Well-Being of Nutrition Assistance Program (NAP) Participants in Puerto Rico

Appendix F3 Advance Material for First Concept Mapping Meeting_02142022

OMB: 0584-0674

OMB Number: 0584-XXXX Expiration

Date: XX/XX/XXXX

Appendix F.3. Advance Material for First Concept Mapping Meeting

Overview

Thank you for agreeing to participate in the Puerto Rico Health and Well-Being Study as a stakeholder. Over the next 6 months, you will participate in two scheduled meetings. During these meetings, we will ask you to contribute your ideas and help us improve our understanding of food security in Puerto Rico. Because of the limited research on this topic, we have selected a participatory and consensus-oriented approach called group concept mapping (GCM). The GCM methodology is a form of expert elicitation that employs a six-step process, described in more detail in the following sections, and results in a structural model that can be used to facilitate planning or inform decision making. You will be part of a knowledgeable, diverse, and engaged group of individuals interested in discussing ways to improve food security in Puerto Rico.

During the two virtual stakeholder group meetings, we will gather recommendations on two questions about how to improve the food security of Nutrition Assistance Program (NAP) recipients:

What policy and administrative changes can improve the food security of NAP recipients?

What gaps in knowledge of how NAP protects against low food security, particularly when a natural disaster strikes, should be addressed to improve the food security of NAP recipients?

These two questions cover a wide range of programs and policies that potentially affect NAP recipients. To help focus the discussion, stakeholders will address policy and administrative changes and research gaps across three policy/program areas:

NAP (i.e., Programa de Asistencia Nutricional)

Other public, nonprofit, and private sector programs that can directly affect food security of NAP-eligible population (e.g., Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; school meal programs)

Public, nonprofit, and private sector human service programs that have an indirect effect on the food security of NAP-eligible population (e.g., income supports, housing, transportation)

The following sections provide background on NAP, other programs that directly or indirectly affect food security, and the GCM process. While this information is provided to help frame the discussions that will take place, we want to emphasize that we are interested in your understanding, your ideas, and your perspective.

Background Information

In September 2017, Hurricanes Irma and Maria wreaked significant damage to Puerto Rico’s infrastructure and agricultural production, destroying the power grid and causing a major humanitarian crisis. Congress responded by appropriating $1.27 billion in additional funding for disaster nutrition assistance to be distributed through Puerto Rico’s NAP.1 The additional funding was used to raise income limits and increase benefit amounts for eligible households.2

Nearly 2 years later, Congress requested the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to conduct a study to assess the impact of the additional benefits appropriated for NAP participants under the Disaster Relief Act and compare their food security, health status, and well-being with those of residents without such benefits. That request is the impetus for the proposed study.

Food Security in Puerto Rico

Multiple factors contribute to the problem of low food security in Puerto Rico. Economic hardship represents one driving factor. In 2019, Puerto Rico’s overall poverty rate was more than 43 percent, compared with 13 percent in the entire United States and 20 percent in Mississippi, the poorest State.3 Natural disasters such as hurricanes and earthquakes exacerbate the economic instability and threaten Puerto Rico’s food system, which relies heavily on imports from other countries. When hurricanes or other disasters strike, they delay food imports, resulting in food scarcity.

Unlike States and territories participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Puerto Rico is not authorized to obtain disaster nutrition assistance directly from USDA and must request additional grant funding through Congress. This reliance on Congress for disaster relief further contributes to low food security in Puerto Rico by delaying assistance for those most directly affected by disasters.

Puerto Rico’s Nutrition Assistance Program

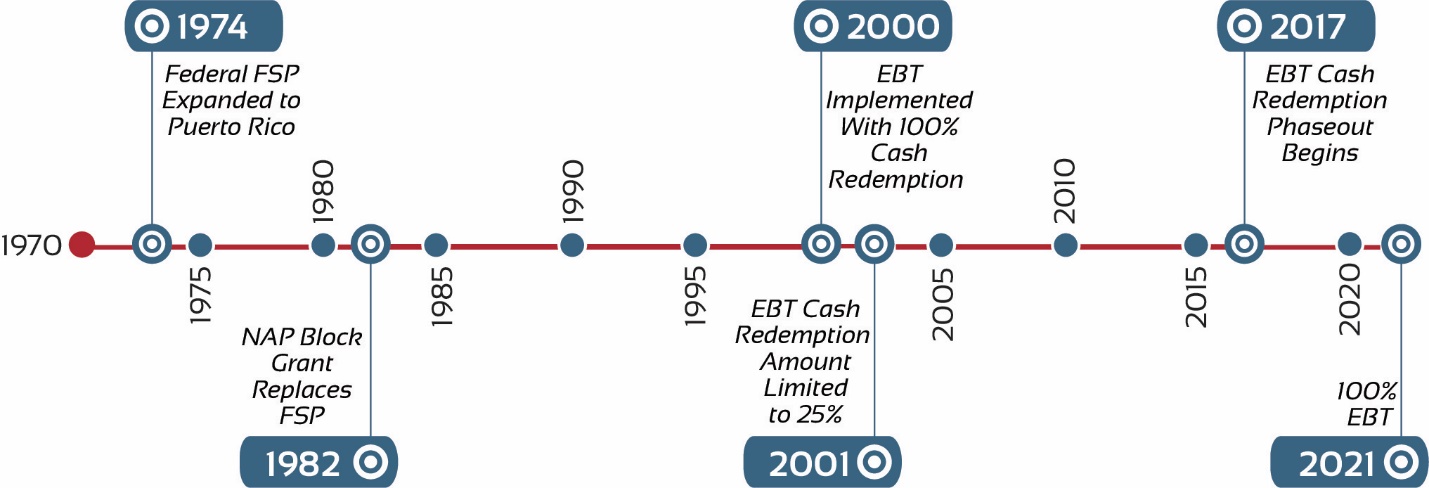

Figure 1. History of Puerto Rico's Nutrition Assistance Program

As figure 1 illustrates, NAP was first implemented in 1982 to replace the food stamp program, which had been operating in Puerto Rico since 1974. NAP is a block grant that aims to reduce hunger and improve the health and well-being of Puerto Rico’s most vulnerable residents by providing eligible households with nutrition assistance benefits. NAP is one of the key policy tools in the Puerto Rico food system for addressing food security. At the Federal level, FNS Mid-Atlantic Regional Office has administrative oversight of NAP in Puerto Rico. It is a fixed-block grant that is 100 percent federally funded for benefits and 50 percent funded for approved administrative costs. At the local level, NAP is administered by the Administración de Desarrollo Socioeconómico de la Familia (ADSEF) of Puerto Rico through 10 regional offices and more than 90 local offices.4 As a block grant, ADSEF may change eligibility requirements to serve more or fewer households, and the level of assistance varies with the demand placed on the program by eligible participants. In fiscal year (FY) 2020, NAP provided an average monthly benefit per household of $286.64 to 790,704 households, with an annual cost of benefits of $2,677,471,513.5

NAP has changed significantly since its initial implementation in Puerto Rico, evolving from a coupon-based (i.e., paper voucher) entitlement program to the current block grant program delivered through an electronic benefit transfer (EBT) system. NAP benefits were initially distributed through paper checks that participants redeemed for cash intended for food purchases, creating a 100 percent cash program. In October 2000, the transition from paper check to EBT began, and during this time NAP participants were able to withdraw up to 100 percent of their benefit dollars as cash.6 In 2001, it was required that 75 percent of benefits be used for eligible food purchases, and only 25 percent of the NAP benefits were allowed to be withdrawn in cash. The Agricultural Act of 2014 required Puerto Rico to phase out the cash portion of NAP benefits by 5 percentage points per year beginning in FY 2017. The Act required this phaseout to be completed by FY 2021, meaning that 100 percent of the benefits were to be used exclusively for eligible food purchases at participating retailers.7

In 2016, FNS approved the use of a portion of the NAP benefits for Family Markets. Family Markets are public spaces in which local farmers can offer their products for purchase with NAP benefits. The Family Markets were created through a collaboration between ADSEF and the Department of Agriculture of Puerto Rico to encourage the consumption of healthy, locally grown produce among NAP participants and boost the local economy of farmers in Puerto Rico. NAP participants receive an adjustment of up to 4 percent of their monthly benefits to exclusively use at Family Markets. However, the adjustment is contingent upon the availability of funds.

Public, Nonprofit, and Private Sector Food Security Programs (Other Than NAP)

Public, nonprofit, and private sector food security programs available in Puerto Rico include the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); Child Nutrition Programs; the Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP); Pandemic EBT (P-EBT); and food banks.

Eligible families on the island can participate in WIC, a federal program that provides supplemental foods, healthcare referrals, and nutrition education for low-income women, infants, and children up to age 5 who are at nutritional risk (GAO, 2014).8

Puerto Rico receives funding for the National School Lunch, National School Breakfast, Summer Food Service, and Children and Adult Care Food Programs.9

As a result of the COVID-19 health crisis, Puerto Rico was also extended the P-EBT. This program supplements school meals students might have missed while schools were closed during the pandemic.10

TEFAP is a food distribution program that supports institutions and organizations such as food banks, food pantries, soup kitchens, and other emergency feeding organizations serving low-income residents.11

El Banco de Alimentos de Puerto Rico, a food bank that is a member of Feeding America, is available for residents of Puerto Rico. El Banco de Alimentos de Puerto Rico is a nonprofit organization that collects and distributes food throughout the island using community organizations and churches. Currently, it has a network of more than 165 organizations, agencies, and churches to serve those in need of food.12

Public, Nonprofit, and Private Sector Human Service Programs That Affect Food Security

Public, nonprofit, and private sector human service programs available in Puerto Rico include the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF); Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP); Aid to Aged, Blind, and Disabled (AABD); Section 8 Housing Assistance; and Head Start. Many of the same Federal programs from the U.S. mainland are available to residents of Puerto Rico. However, some of these programs have limited funding in Puerto Rico.13

Residents of Puerto Rico can be eligible for TANF, which provides cash assistance to low-income families for their basic needs. Residents can also be eligible for LIHEAP, a Federal program that provides assistance for energy costs to low-income households. Similar to NAP, both of these programs are administered by ADSEF.

Instead of Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Puerto Rico has the AABD program, which provides cash benefits to individuals who are elderly, blind, or disabled and have limited assets and income.

When it comes to healthcare, Puerto Rico residents can be eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. However, Medicare reimbursements are different than for States, and Medicaid funding in Puerto Rico is capped and matching is limited.

Puerto Rico residents are also eligible for Section 8 Housing Assistance Payments Program, which provides housing assistance to low-income families, and Head Start, a Federal program to promote school readiness for young children of low-income families.

Group Concept Mapping

Group concept mapping (GCM) is a structured process of collaborative problem solving that aims to develop a broad and dynamic understanding of a complex and often not well-understood problem or issue. It is a truly participatory approach that begins with an open-ended brainstorming process that sources ideas from a group of individuals with a particular focus or understanding of the issue or problem that is being conceptualized.

GCM is a collaborative, mixed-methods approach to data collection that seeks to generate understanding from a group of knowledgeable individuals, all of whom contribute equally to the final product. It begins with an open-ended question and an idea-generating session that produces information that is subsequently used in a quantitative, multidimensional scaling procedure to generate a visual model that summarizes the thoughts and ideas of the group. The GCM approach is not a rigid methodology but tends to follow a regular pattern that involves six steps originally outlined by Trochim (1989):14

Planning and preparation. We developed the focus prompt—the statement or question that will drive the brainstorming activities—and the rating dimensions that will be used to rank the results of the brainstorming. We invite you and a diverse group of other stakeholders who are knowledgeable and involved in the food system in Puerto Rico to participate in this process.

Statement generation (brainstorming). You will be asked to respond to the focus prompt with suggestions and ideas. We encourage discussion to enrich the brainstorming session, but the main purpose of brainstorming is for stakeholders to generate as many ideas related to the focus prompt as possible. Most of the brainstorming will take place at the first virtual meeting, but you can continue to provide ideas for up to 2 weeks following the meeting by emailing your ideas to us or uploading them to the GroupWisdom platform.

Statement structuring. In this step, each stakeholder will independently organize and rank the ideas generated during brainstorming. First, you will be asked to sort the brainstorm statements into groups. You can form as many or as few groups as you feel are warranted. We ask that you include as many of the statements as possible and avoid creating a group that contains only one idea. We also ask that you attach a meaningful label or name to each group. Next, you will go through the statements one by one and rate each statement. Rating dimensions that have been used in similar policy-oriented projects are potential for impact and feasibility of implementation.

Analysis and data visualization. The information generated in statement structuring—groupings and ratings—form the dataset we will use to summarize the breadth and depth of stakeholder input. Analytic methods include multidimensional scaling and tests of association that will examine the interrelationship of ideas and generate useful maps and data visualization tools that convey the association and relative importance of each statement along the selected dimensions.

Interpretation of maps. Prior to the second virtual meeting, we will share the maps and other data visualizations with the stakeholders for validation and verification. At this stage, you and the other stakeholders will be asked to review the data visualizations and comment on the resulting clusters. We will ask you as a group to confirm or provide alternative suggestions for cluster names and whether the ideas nested within the clusters appear sensible. Some of the data visualizations may be comparative (e.g., based on differences among subgroups of stakeholders, for example), and you may be asked to comment on the observed differences.

Utilization of maps. In the final step, stakeholders will be asked to reflect on the data generation and output and provide suggestions on how the information can best be used to address the research objective. This step may involve making suggestions about which among several ideas should be prioritized.

Thank you again for participating in this important research project. We look forward to connecting with you at the first virtual stakeholder meeting. If you have any questions about the material, you can contact the Project Director, Dr. Claire Wilson ([email protected]), or the Concept Mapping Task Lead, Dr. Jonathan Blitstein ([email protected]).

Public

Burden Statement This

information is being collected to assist the Food and Nutrition

Service (FNS) in understanding food security status and economic

well-being among Puerto Rico residents. This is a voluntary

collection. FNS will use the information as a baseline for future

assessments of food security and the Nutrition Assistance Program,

particularly in the context of natural disasters. This collection

does not request personally identifiable information under the

Privacy Act of 1974. According to the Paperwork Reduction Act of

1995, an agency may not conduct or sponsor, and a person is not

required to respond to, a collection of information unless it

displays a valid OMB control number. The valid OMB control number

for this information collection is 0584-XXXX. The time required to

complete this information collection is estimated to average 75

minutes per response, including the time for reviewing instructions

and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send

comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this

collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this

burden, to: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition

Service, Office of Policy Support, 1320 Braddock Place, Alexandria,

VA 22314. ATTN: PRA (0584-XXXX). Do not return the completed form to

this address.

1 H.R.4008 - 115th Congress (2017-2018): Additional Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act of 2017. (2017). https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/4008/text

2 Keith-Jennings, B., & Wolkomir, E. (2020). How does household food assistance in Puerto Rico compare to the rest of the United States? Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/11-27-17fa.pdf

3 Glassman, B. (2019). A third of movers from Puerto Rico to the mainland United States relocated to Florida in 2018. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/09/puerto-rico-outmigration-increases-poverty-declines.html#:~:text=The%20poverty%20rate%20in%20Puerto,state%20poverty%20rates%20in%202018

4 Administración de Desarrollo Socioeconómico de la Familia. (2020). PR NAP State Plan of Operations, FY 2021. Retrieved from: https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/NAP-state-plan-fy2021.pdf.

5 USDA FNS. (2021). Puerto Rico Nutrition Assistance Program. https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/puerto-rico-nutrition-assistance-program

6 Trippe, C., Gaddes, R., Suchman, A., Place, K., Mabli, J., Tadler, C., DeAtley, T., & Estes, B. (2015). Examination of Cash Nutrition Assistance Program Benefits in Puerto Rico: Final report. Prepared by Insight Policy Research for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/PuertoRico-Cash.pdf

7 Government of Puerto Rico. (2021). PR NAP State plan of operations. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/NAP-state-plan-fy2021.pdf

8 GAO. (2014). Puerto Rico: Information on how statehood would potentially affect selected Federal programs and revenue sources. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-14-31

9 Ibid.

10 USDA FNS. (2021). State guidance on Coronavirus P-EBT. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/state-guidance-coronavirus-pandemic-ebt-pebt

11 Congressional Research Service. (2018). The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP): Background and funding. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45408/1

12 Banco de Alimentos Puerto Rico. (n.d.). Banco de Alimentos Puerto Rico [Web page]. https://www.alimentospr.com/?lang=en

13 GAO. (2014). Puerto Rico: Information on how statehood would potentially affect selected Federal programs and revenue sources. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-14-31

14 Trochim, W.M.K. (1989). An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 12(1): 1 -16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(89)90016-5

Food Security Status and Well-Being of NAP Participants in Puerto Rico, Appendix F.3. Advance Material for First Concept Mapping Meeting

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Allyson Corbo |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2024-07-25 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy