NLSY79_R31_Supporting_Statement_Part A_240508

NLSY79_R31_Supporting_Statement_Part A_240508.docx

National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979

OMB: 1220-0109

National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979

OMB Control Number: 1220-0109

OMB Expiration Date: 8/31/2025

SUPPORTING STATEMENT FOR

National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979

OMB CONTROL NO. 1220-0109

This Information Collection Request (ICR) is a revision of a currently approved collection seeking to obtain clearance for the main fielding of Round 31 of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79). The sample includes 9,964 persons who were 57 to 64 years old on December 31, 2021. Approximately 13 percent of the sample members are deceased. The NLSY79 is a representative national sample of adults who were born in the years 1957 to 1964 and lived in the U.S. when the survey began in 1979. The sample contains an overrepresentation of Black and Hispanic respondents to include a sufficient sample size to permit racial and ethnic analytical comparisons. Appropriate weights have been developed so that the sample components can be combined in a manner to aggregate to the overall U.S. population of the same ages, excluding those who have immigrated since 1978.

The main NLSY79 is funded primarily by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The BLS contracts with Center for Human Resource Research (CHRR) at The Ohio State University and the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago to conduct the survey. NORC handles the interviewing, initial data preparation, and weighting. Questionnaire design, additional data cleanup and preparation, development of documentation, and preparation of data files are handled by CHRR.

The data collected in this survey are part of a larger set of surveys in which longitudinal data are gathered for several cohorts in the U.S. In addition to the NLSY79, these include four National Longitudinal Survey Original Cohorts and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97). Additionally, the BLS currently is developing the content and design of a new NLSY cohort, including design of collection instruments, sampling and screening methodologies, outreach materials, and systems for processing and storing collected data. In recognition of the potential for data users to make cross-cohort comparisons of the collected data, these various cohorts are designed so that many questions asked of a cohort are identical or very similar to those asked of other cohorts. Other questions may differ among cohorts as needed to capture the changing nature of institutions and the different problems facing these groups of people.

JUSTIFICATION

1. Explain the circumstances that make the collection of information necessary. Identify any legal or administrative requirements that necessitate the collection. Attach a copy of the appropriate section of each statute and regulation mandating or authorizing the collection of information.

This ICR covers the main fielding of Round 31 of the NLSY79. The NLSY79 is a nationally representative sample of persons who were born in the years 1957 to 1964 and lived in the U.S. when the survey began in 1979. The longitudinal focus of the survey requires the collection of identical information for the same individuals over the life cycle and the occasional introduction of new data elements to meet the ongoing analytical needs of policymakers and researchers. Most of the information to be collected this round has been approved by OMB in previous rounds of the NLSY79. See Attachment 5 for details on changes for this round.

The mission of the Department of Labor (DOL) is, among other things, to promote the development of the U.S. labor force and the efficiency of the U.S. labor market. The BLS contributes to this mission by gathering information about the labor force and labor market and disseminating it to policymakers and to the public so that participants in those markets can make more informed and, thus, more efficient choices. The charge to the BLS to collect data related to the labor force is extremely broad, as reflected in Title 29 U.S.C. Section 1:

“The general design and duties of the Bureau of Labor Statistics shall be to acquire and diffuse among the people of the United States useful information on subjects connected with labor, in the most general and comprehensive sense of that word, and especially upon its relation to capital, the hours of labor, the earnings of laboring men and women, and the means of promoting their material, social, intellectual, and moral prosperity.”

The collection of these data contributes to the BLS mission by aiding in the understanding of labor market outcomes faced by individuals in the early stages of career and family development. See Attachment 1 for Title 29 U.S.C. Sections 1 and 2.

2. Indicate how, by whom, and for what purpose the information is to be used. Except for a new collection, indicate the actual use the agency has made of the information received from the current collection.

Through 1984, the NLSY79 consisted of annual interviews with a national sample of 12,686 young men and women who were ages 14 to 21 as of December 31, 1978, with overrepresentation of Black, Hispanic, and economically disadvantaged non-Blacks/non-Hispanic populations. The sample also included 1,280 persons serving in the military in 1978. Starting in 1985, the military sample was reduced to 201 due to a cessation of funding from the Department of Defense. Starting in 1991, interviews were discontinued with the 742 male and 901 female members of the economically disadvantaged non-Black/non-Hispanic sample. This reduced the eligible pool of sample members to 9,964. The NLSY79 was conducted annually from 1979 to 1994 and has been conducted every two years since 1994.

In addition to the regular interviews, several supplementary data-collection efforts completed during the early survey years greatly enhance the value of the survey to policymakers and researchers. The full Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) was administered to 94 percent of sample members. Also, for a large proportion of the sample, information has been collected about the characteristics of the last high school each respondent attended, as well as the courses taken, grades, and some other personal characteristics about the respondents while attending high school.

These data-collection efforts have enabled researchers to complete studies of the relationship between background environment, employment behavior, vocational aptitudes, and high school quality. The data have helped the Departments of Labor, Defense, Education, and Health and Human Services and many congressional committees to make more knowledgeable decisions when evaluating the efficacy of programs in the areas of civilian and military employment, training, and health.

The NLSY79 is a general-purpose study designed to serve a variety of policy-related research interests. Its longitudinal design and conceptual framework serve the needs of policymakers in a way that cross-sectional surveys cannot. In addition, the NLSY79 allows a broad spectrum of social scientists concerned with the labor market problems of young baby boomers to pursue their research interests. The increasingly omnibus nature of the survey makes it an efficient, low-cost data set. Historically, the survey has incorporated items needed for program and policy purposes by agencies other than the Department of Labor. In this survey round, we anticipate funding from the National Institute on Aging.

Sample sizes and the expected number of Round 31 respondents are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. NLSY79 Sample Size and Expected Response in 2024 (Round 31)

Cohort |

Approximate sample size |

Expected number of respondents |

NLSY79 main |

8,617 |

6,353 |

The specific objectives of the NLSY79 fall into several major categories that will be further explained below:

to explore the labor market activity and family formation of individuals in this age group;

to explore in greater depth than previously has been possible the complex economic, social, and psychological factors responsible for variation in the labor market experience (including retirement) of this cohort;

to explore how labor market experiences explain the evolution of careers, wealth, and the preparation of this cohort for the further education of their children and for their own retirement;

to analyze the impact of a changing socio-economic environment on the labor market experiences of this cohort by comparing data from the present study with those yielded by the surveys of the earlier NLS cohorts of young men (which began in 1966 and ended in 1981) and young women (which began in 1968 and ended in 2003), as well as the more recent NLSY97 cohort of young men and women born in the years 1980-84 and interviewed for the first time in 1997;

to consider how intergenerational links between mothers and their children, including the employment-related activities of women affect the subsequent cognitive and emotional development of their children, and how the development of the children affects the activities of the mother; and

to meet the data-collection and research needs of various government agencies with an interest in the relationships among child and maternal health, drug and alcohol use, and juvenile deviant behavior and child outcomes such as education, employment, and family experiences and interest in the relationships between health, cognition, and retirement.

The NLSY79 has several characteristics that distinguish it from other data sources and make it uniquely capable of meeting the major purposes described above. The first of these is the breadth and depth of the types of information that are being collected. It has become increasingly evident in recent years that a comprehensive analysis of the dynamics of labor force activity requires an eclectic theoretical framework that draws on several disciplines, particularly economics, sociology, and psychology. For example, the exploration of the determinants and consequences of the labor force behavior and experience of this cohort requires information about (1) the individual’s family background and ongoing demographic experiences; (2) the character of all aspects of the environment with which the individual interacts; (3) human capital inputs such as formal schooling and training; (4) a complete record of the individual’s work experiences; (5) the behaviors, attitudes, and experiences of closely related family members, including spouses and children; and (6) a variety of social-psychological measures, including attitudes toward specific and general work situations, personal feelings about the future, personality characteristics, and perceptions of how much control one has over one’s environment.

A second major advantage of the NLSY79 is its longitudinal design, which permits investigation of labor market dynamics that would not be possible with one-time surveys and allows directions of causation to be established with much greater confidence than cross-sectional analyses. Also, the considerable geographic and environmental information available for each respondent for each survey year permits a more careful examination of the impact that area employment and unemployment considerations have for altering the employment, education, and family experiences of these cohort members and their families.

Third, the oversampling of Black and Hispanic youth, together with the other two advantages mentioned above, makes possible more sophisticated examinations of human capital creation programs than previously have been possible. Post-program experiences of “treatment” groups can be compared with those of groups matched not only for preprogram experience and such conventional measures as educational attainment, but also for psychological characteristics that have rarely been available in previous studies.

As has been indicated above, the study has several general research and policy-related objectives.

Attachment 3- Survey Applications

Elaborates on these basic purposes by setting forth a series of specific research themes.

Attachment 4- Analysis of Content of Interview Schedules

Relates the detailed content of the interview schedule to the themes from Attachment 3.

Attachment 5- New Questions and Lines of Inquiry

Summarizes the new questions and lines of inquiry in the proposed questionnaire.

Attachment 6- Respondent Advance Letters

Provides the advance letters that will be sent to respondents prior to data collection and the questions and answers about uses of the data, confidentiality, and burden that will appear on the back of each advance letter.

The NLSY79 is part of a broader group of surveys that are known as the BLS National Longitudinal Surveys (NLS) program. In 1966, the first interviews were administered to persons representing two cohorts, Older Men ages 45-59 in 1966 and Young Men ages 14-24 in 1966. The sample of Mature Women ages 30-44 in 1967 was first interviewed in 1967. The last of the original four cohorts was the Young Women, who were ages 14-24 when first interviewed in 1968. The survey of Young Men was discontinued after the 1981 interview, and the last survey of the Older Men was conducted in 1990. The Young and Mature Women surveys were discontinued after the 2003 interviews. The most recent cohort added to the NLS program is the NLSY97, which includes persons who were ages 12–16 on December 31, 1984.

The National Longitudinal Surveys are used by BLS and other government agencies to examine a wide range of labor market issues. The most recent BLS news release that examines NLSY79 data was published on August 22, 2023, and is available online at http://www.bls.gov/news.release/nlsoy.nr0.htm. In addition to BLS publications, analyses have been conducted in recent years by other agencies of the Executive Branch, the Government Accountability Office, and the Congressional Budget Office. The surveys also are used extensively by researchers in a variety of academic fields. A comprehensive bibliography of journal articles, dissertations, and other research that have examined data from all National Longitudinal Surveys cohorts is available at http://www.nlsbibliography.org/.

3. Describe whether, and to what extent, the collection of information involves the use of automated, electronic, mechanical, or other technological collection techniques or other forms of information technology, e.g., permitting electronic submission of responses, and the basis for the decision for adopting this means of collection. Also, describe any consideration of using information technology to reduce burden.

The field staff of NORC makes every effort to ensure that the information is collected in as expeditious a manner as possible, with minimal interference in the lives of the respondents. Its success in this regard is suggested by the very high continuing response rate and low item refusal rates that have been attained. More recent efforts also have advanced technologies that lower respondent burden. In Round 31, respondents who wish to respond during the “early bird” will be able to arrange their interviews electronically through an appointment-setting application that is designed specifically for use by NLSY79 respondents. Use of this application increases the efficiency of the data collection process. As described below, the survey has encouraged this behavior in recent rounds by offering an “early bird incentive;” Round 31 includes an experiment to evaluate the effectiveness of this incentive.

During Round 11 (1989) of the NLSY79, about 300 cases were collected using a Computer Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI). During Round 12 (1990) CAPI was again used, this time for about 2,400 cases using a longer and more complex questionnaire. The CAPI efforts in 1989 and 1990 were designed to assess the feasibility of the method and the effect of CAPI methods on data quality. Since 1993, the NLSY79 has been conducted using CAPI for all cases. Note that some cases have been completed over the telephone in each round. In rounds 26-28, the percentage of cases completed by phone was around 96%; in Round 29, due to the coronavirus pandemic, all but one case were completed by phone; and in Round 30, over 97% of completions were conducted by telephone. The system has proved to be stable and reliable and is well received by interviewers, respondents, and researchers.

An analysis of the Round 12 (1990) experimental data revealed that the quality of the data, as measured by missing or inconsistent responses, was greatly improved by CAPI. The effects on the pattern of responses were minor, although some answer patterns were affected because the CAPI technology in certain cases changed the way the questions were asked. Production data from Rounds 15–21, based on over 80,000 completed interviews, showed these predictions of high-quality data were correct.

The Round 31 questionnaire is programmed in a single computer-assisted interviewing (CAI) platform that interviewers can use for either telephone or in-person administration. The programming of the questionnaire is highly complex and uses extensive information from prior interviews as well as different points in the current interview. Paper and pencil administration would likely involve a high rate of error. Using a single platform for both interviewing modes greatly improves the efficiency of questionnaire programming, data quality assurance, and post-data collection data processing activities relative to having separate platforms for different interviewing modes.

The CAI questionnaire offers additional features for data quality assurance. These include the capture of item-level timings, recordings of the interviewer-respondent interaction, and the ability to monitor when the interview might have been interrupted or resumed. The availability of these features allows the data collection team to monitor interviewer performance and inspect for data falsification with minimal additional burden on respondents; as described in Section 12 below, NLS expects to conduct less than 100 short validation interviews. Re-interviews are then conducted only in the event of concerns about how an interview was conducted based on the available recordings, timings, and other data. The NLSY79 has had need for minimal re-interviews in recent years – it had none in the last four rounds – and expects at most 1 percent of interviews to require a re-interview in Round 31.

The questionnaire’s consent statement indicates that the interview will be recorded for quality control purposes. If a respondent declines to be recorded, the timings and other data quality-related paradata can generally provide adequate information for data quality assurance. If necessary, re-interviews can be conducted with a small number of respondents, included in the estimate of 1 percent of interviews above.

4. Describe efforts to identify duplication. Show specifically why any similar information already available cannot be used or modified for use for the purposes described in Item A.2 above.

A 1982 study entitled “National Social Data Series: A Compendium of Brief Descriptions” by Richard C. Taeuber and Richard C. Rockwell includes an exhaustive list with descriptions of the national data sets available at that time. A careful examination of all the data sets described in their listing indicates that no other data set would permit the comprehensive analyses of youth and young adult employment that can be conducted using the National Longitudinal Surveys. Indeed, the absence of alternative data sources was the deciding factor in the Department of Labor’s determination (in 1977) to sponsor the NLSY79. The longitudinal nature of the survey and the rich background information collected mean that no survey subsequently released can provide data to replace the NLSY79. The expansion in the mid-1980s of the NLSY79 to incorporate information on child outcomes represents a unique intergenerational data-collection effort.

Survey staff have continued to confirm that no comparable data set exists. An investigation into data sets related to wealth by F. Thomas Juster and Kathleen A. Kuester describes the data available in the wealth domain, showing the unique nature of the data available in the NLS.

The 1993 volume The Future of the Survey of Income and Program Participation points out a number of contrasts between the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) and the NLS and other major longitudinal studies (see especially pages 77, 107, and 265–7). This book was written primarily to review the SIPP but helps put the major longitudinal surveys in perspective.

BLS convened a conference in fall 1998 to look at the design of the NLSY79 for 2002 and beyond. In the process, external reviewers assessed the coverage, quality, and duplication of the survey. In its central areas of coverage—event histories on labor supply, major demographic events, and child assessments—this conference concluded that the NLSY79 was well-designed and continued to be a unique resource, unduplicated in the national statistical inventory.

An article by Michael Pergamit, et al. (2001) discusses the strengths of the NLSY79, and prominent research that had been done using NLSY79 data. Many of these studies could not have been done otherwise, because the NLSY79 has such a breadth of information, along with a history of all jobs ever held and a cognitive test score. A later paper by Aughinbaugh, et al. (2015) examines the unique strengths of the NLSY79 and NLSY97 surveys, and the resulting important research.

In 2016, BLS convened a panel of aging, health, and retirement experts to give advice on the content and direction the survey needs to take in the next 10-15 years. The Retirement Working Group, led by Professor Kathleen McGarry, provided advice on survey content, linkages to administrative data, and such, which the NLSY79 has already begun implementing. In 2023, another group of experts, led by Professor Melissa McInerney, was convened to advise BLS on the relative benefits of following several different pathways as the survey sample grows older. The Pathways Working Group identified several key areas of research related to aging, work (both paid and unpaid), and other productive activities in which the NLSY79 remains uniquely positioned to provide needed information. Many of these areas were also identified in a recent National Academies (2022) report describing needed research pertaining to the Aging workforce. The Pathways group emphasized the tremendous value of continuing to collect data from this cohort for several more rounds.

The NLSY79 provides advantages for studying aging and retirement over other longitudinal studies, which tend to begin when respondents are much older. The NLSY79 contains a long history of information collected as events occurred, including extensive life course data on work, wages, and job characteristics. In addition, over half of the sample members have a sibling in the sample, the NLSY79 Child/Young Adult data contains assessments and interviews with children of the female respondents, and the main survey contains data on respondents’ cognition and health over the years.

Past work shows that there is no other longitudinal data set available that can address effectively the many research topics highlighted in attachment 3. This data set focuses specifically and in great detail on the employment, educational, demographic, and social-psychological characteristics of a nationally represented sample of younger baby boomers and their families and measures changes in these characteristics over long time periods. The survey gathers this information for both men and women, and for relatively large samples of Black and Hispanic adults. The repeated availability of this information permits consideration of employment, education, and family issues in ways not possible with any other available data set. The combination of (1) longitudinal data covering the time from adolescence; (2) national representation; (3) large Black and Hispanic samples; and (4) detailed availability of education, employment and training, demographic, health, child outcome, and social-psychological variables make this data set, and its utility for social science policy-related research, unique.

In addition to the content of the interviews, the survey is also distinctive because of its coverage of the respondents’ lives for more than 40 years and the linkage between data on mothers and their children. These aspects attract the thousands of users who rely on this survey for their studies of American workers, their careers, and their families.

References

Aughinbaugh, Alison, Charles R. Pierret, and Donna S. Rothstein. “The National Longitudinal Surveys of Youth: Research Highlights.” Monthly Labor Review (September 2015). https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2015.34.

Citro, Constance C. and Kalton, Graham, eds. The Future of the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1993.

Juster, F. Thomas and Kuester, Kathleen A. “Differences in the Measurement of Wealth, Wealth Inequality and Wealth Composition Obtained from Alternative U.S. Wealth Surveys.” Review of Income and Wealth Series 37, Number 1 (March 1991): 33-62.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. "Understanding the aging workforce: Defining a research Agenda." (2022).

Pergamit, Michael R., Charles R. Pierret, Donna S. Rothstein, and Jonathan R. Veum. “Data Watch: The National Longitudinal Surveys.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 15, 2 (Spring 2001): 239-253.

Taeuber, Richard C. and Rockwell, Richard C. “National Social Data Series: A Compendium of Brief Descriptions.” Review of Public Data Use 10, 1-2 (May 1982): 23-111.

5. If the collection of information impacts small businesses or other small entities, describe any methods used to minimize burden.

The NLSY79 is a survey of individuals in household and family units and therefore does not involve small organizations.

6. Describe the consequence to federal program or policy activities if the collection is not conducted or is conducted less frequently, as well as any technical or legal obstacles to reducing burden.

The core of the National Longitudinal Surveys is the focus on labor force behavior. It is very difficult to reconstruct labor force behavior retrospectively and still maintain sufficient precision and data quality. This is the single most important reason the NLS strives to maintain regular interviews with these respondents, who on average have frequent transitions in employment, income and earnings, and family and household structure. Historic dates relating to these transitions are difficult to reconstruct when one focuses on events earlier than the recent past. For those who are employed, retrospective information on wages, detailed occupations, job satisfaction, or other employment-related characteristics cannot be easily recalled.

As with employment-related information, data about a respondent’s education and training history are also difficult to recall retrospectively. Completion dates of training and education programs are subject to severe memory biases. Thus, causal analyses that require a sequencing of education, training, and work experiences cannot be easily or accurately accomplished with historical data. Not only are completion dates of educational and training experiences frequently difficult to recall, but there is also evidence that misreporting of program completion is not unusual.

The precise timing and dating of demographic, socio-economic, and employment events, so crucial to most labor force analysis, is in most instances impossible to reconstruct accurately through retrospective data collection that extends very far into the past. For example, there is evidence from the NLS that dates of events of fundamental importance, such as marriage and birth histories, are subject to considerable error at the disaggregated level when collected retrospectively. Respondents have difficulty recalling when their marriages began or ended. Also, accurate information about household structure, how it changes over time, and how this relates to changes in family income and labor force dynamics is difficult to reconstruct retrospectively, as is the information on the health and related behaviors of the respondents, their spouses, and their children.

Finally, it is important to emphasize that information of a subjective nature can only be accurately reported and collected on a contemporaneous basis. Recollection of attitudes may be colored by subsequent experiences or reflect a rationalization of subsequent successes or failures. Attitudes as widely diverse as one’s ideas about women’s roles or how one perceives one’s health as of an earlier period can be recollected inaccurately, even when respondents are trying to be as honest as they can. In addition, the older the events that one tries to recall, either objective or subjective in nature, the greater the likelihood of faulty recall. The recall of events or attitudes is often biased either by a tendency to associate the event with major life-cycle changes (that may or may not be in temporal proximity to what one is trying to recall) or to move the event into the more recent past.

While more frequent interviewing is desirable, financial limitations prompted the NLSY79 to move to a biennial interview cycle beginning in 1994. The data loss due to reduced frequency is somewhat ameliorated by the fact that the cohort is more established, having negotiated the school-to-work transition with varying degrees of success. The NLSY79 uses bounded interviewing techniques and is designed so that when respondents miss an interview, information not collected in the missed interview is gathered in the next completed interview. In this way, the event history on work experience is very complete.

A study was conducted to assess the impact of the longer recall period by using an experimental design in the 1994 interview. About 10 percent of the respondents who were interviewed in 1993 were given a modified instrument that was worded as if the respondents were last interviewed in 1992. Using this experimental structure, NLS examined the respondents’ reports on experiences between the 1992 and 1993 interviews using information from their 1993 and 1994 reports on that same reference period. As expected, recall was degraded by a lower interview frequency. Events were misdated and some short duration jobs were not reported when the reference period was moved back in time. Based on this evidence, it is clear that less frequent data collection adversely affects longitudinal surveys.

A second potential problem caused by the move to a biennial interview is a decline in NLS’s ability to locate respondents who move. NLS has been able to compensate for this so far, but a change to less frequent interviewing would likely have a more negative impact.

7. Explain any special circumstances that would cause an information collection to be conducted in a manner:

requiring respondents to report information to the agency more often than quarterly;

requiring respondents to prepare a written response to a collection of information in fewer than 30 days after receipt of it;

requiring respondents to submit more than an original and two copies of any document;

requiring respondents to retain records, other than health, medical, government contract, grant-in-aid, or tax records for more than three years;

in connection with a statistical survey, that is not designed to produce valid and reliable results that can be generalized to the universe of study;

requiring the use of statistical data classification that has not been reviewed and approved by OMB;

that includes a pledge of confidentially that is not supported by authority established in statute or regulation, that is not supported by disclosure and data security policies that are consistent with the pledge, or which unnecessarily impedes sharing of data with other agencies for compatible confidential use; or

requiring respondents to submit proprietary trade secret, or other confidential information unless the agency can demonstrate that it has instituted procedures to protect the information's confidentially to the extent permitted by law.

None of the listed special circumstances apply.

8. If applicable, provide a copy and identify the date and page number of publication in the Federal Register of the agency's notice, required by 5 CFR 1320.8(d), soliciting comments on the information collection prior to submission to OMB. Summarize public comments received in response to that notice and describe actions taken by the agency in response to these comments. Specifically address comments received on cost and hour burden.

Describe efforts to consult with persons outside the agency to obtain their views on the availability of data, frequency of collection, the clarity of instructions and recordkeeping, disclosure, or reporting format (if any), and on the data elements to be recorded, disclosed, or reported.

Consultation with representatives of those from whom information is to be obtained or those who must compile records should occur at least once every 3 years -- even if the collection-of-information activity is the same as in prior periods. There may be circumstances that may preclude consultation in a specific situation. These circumstances should be explained.

No public comments were received as a result of the Federal Register notice published in 89 FR 11317, on February 14, 2024.

There have been numerous consultations regarding the NLSY79. Preceding the first round of the NLSY79, the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) sponsored a conference at which academic researchers from a broad spectrum of fields were invited to present their views regarding the value of initiating a longitudinal youth survey and what the content of the survey should include. The initial survey development drew heavily on the suggestions made at this conference, which were published in a proceeding under the auspices of the SSRC.

In 1988, the National Science Foundation sponsored a conference to consider the future of the NLS. This conference consisted of representatives from a variety of academic, government, and nonprofit research and policy organizations. There was enthusiastic support for the proposition that the NLS should be continued in the current format, and that the needs for longitudinal data would continue over the long run. The success of the NLS, which was the first general-purpose, longitudinal labor survey, has helped reorient survey work in the United States toward longitudinal data collection and away from simple cross sections.

Also, on a continuing basis, BLS and its contractors encourage NLS data users to suggest ways in which the quality of the data can be improved and to suggest additional data elements that should be considered for inclusion in subsequent rounds. NLS encourages this feedback through the public information office of each organization and through the ‘Suggested Questions for Future NLSY Surveys’ (available online at https://www.nlsinfo.org/nlsy-user-initiated-questions).

Individuals from other Federal agencies who were consulted regarding the content of the 2024 survey include:

John Phillips

Chief, Population and Social Processes Branch

Division of Behavioral and Social Research

National Institute on Aging

The NLS program has a Technical Review Committee that advises BLS and its contractors on questionnaire content and long-term objectives. The committee typically meets twice a year. Table 2 below shows the current members of the committee.

Table 2. National Longitudinal Surveys Technical Review Committee (December 2021)

Fenaba Addo Department of Public Policy and Department of Sociology University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill |

Jennie Brand Department of Sociology and Department of Statistics University of California, Los Angeles |

Sarah Burgard Department of Sociology and Department of Epidemiology University of Michigan

|

Allyson Holbrook College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs University of Illinois Chicago |

Lisa Kahn Department of Economics University of Rochester |

Michael Lovenheim Department of Policy Analysis and Management Cornell University

|

Nicole Maestas Harvard Medical School

|

Melissa McInerney (chair) Department of Economics Tufts University

|

Emily Owens Department of Criminology, Law & Society and Department of Economics University of California, Irvine

|

John Phillips Division of Behavioral and Social Research National Institute on Aging/NIH

|

Narayan Sastry Population Studies Center University of Michigan |

Jeffrey Smith Department of Economics University of Wisconsin

|

Owen Thompson Department of Economics Williams College |

|

|

The NLS Technical Review Committee convened a conference in 1998 to review the current and future design of the NLSY79. This conference indicated that the central design of the NLSY79 remained strong, although changes in the nation’s welfare program required changes in the program recipiency section of the survey. Many of these changes were implemented in the 2000 and 2002 interviews. Some health section modifications were introduced in 2006 (cognitive functioning model), and the 2008 and 2018 surveys included a new health module for respondents who had reached age 50 and age 60 (mirroring the age 40 module).

9. Explain any decision to provide any payments or gifts to respondents, other than remuneration of contractors or grantees.

The long-term nature of the NLSY79, with regular reinterviewing of subjects over 40+ years, requires that respondents be given ample financial incentive to secure their cooperation. To determine appropriate baselines, missed round incentives, and other bonus incentives, NLS has implemented a variety of experiments over the course of the NLSY79 that have tested different incentive strategies to ensure that any incentive design is relevant.

Respondent incentives represent only a fraction of the total field costs, and higher incentives can be a cost-effective means of increasing response while constraining the overall budget. Each round there is a growing pool of sample members who are reluctant to cooperate. Therefore, the overall data collection strategy includes a set of measures to encourage cooperation beyond just offering higher respondent incentives. NLS requests clearance for the following, integrated conversion strategy:

Table 3: Main NLSY79 incentive categories

Incentive Type |

Completed Round 30 |

Missed Round 30 |

Base |

$70 |

$70 |

Early Bird |

$0 or $30* |

$0 or $30* |

Missed Rounds |

N/A |

$50 to $70 |

Final Push – Standard |

$30 |

$30 |

Final Push – Enhanced** |

$20 |

$20 |

In-kind |

Up to $12 |

Up to $12 |

Gatekeeper |

About $5 |

About $5 |

|

|

|

Min |

$70 |

$120 |

Max*** |

$132 |

$202 |

Typical |

$70 |

$120 |

* Early Bird incentives are experimentally assigned as described below.

** Enhanced final push is in addition to the standard final push for eligible sample members, so the total additional offer is $30+$20 = $50.

*** Maximum does not include the in-kind bonus.

Base Incentive

NLS will again offer a base respondent incentive of $70, the amount that was first introduced in Round 27 and repeated in Rounds 28-30.

Early Bird Incentive

In Rounds 27-30 of the NLSY79, all respondents were offered a $30 incentive (in addition to the base incentive) to provide their responses during the round’s Early Bird period. The intention of this incentive has been to align payments to cooperative behavior and reduce the overall costs of the survey. In Round 31, NLS proposes an experiment designed to test the effectiveness of these early bird incentives relative to increased interviewer outreach.

There are several motivations for conducting this exploration. To start, early bird incentives have historically been paid to roughly half of NLSY79 respondents in a given round and represent a significant cost. Total paid early bird incentives amounted to $91,380 in Round 30 and $102,420 in Round 29. Because most early bird incentives are paid to relatively cooperative respondents, this expenditure may not be effectively targeted to increase overall response. As can be seen in Table 4, almost half of the sample that had completed in the prior round completed in the early bird period (for both Round 29 and Round 30). And over 96% of early bird respondents across both rounds were cases that had completed in the prior round. Additionally, there are a sizable number of NLSY79 respondents who complete the survey with the early bird incentive in one round while completing it without early bird in a different round. For example, only 65% of the respondents who completed early bird in Round 30 also completed early bird in Round 29. Given this behavior, it is possible that many early bird respondents would have completed without the increased incentive.

Table 4. Number of early bird respondents and completion rate by prior round category.

Prior Round Status |

R29 EB N |

R29 EB Comp % |

R30 EB N |

R30 EB Comp % |

Last Round Comp |

3303 (96.7%) |

48.0% |

2969 (97.5%) |

45.4% |

Out 1 Round |

31 (0.9%) |

11.0% |

37 (1.2%) |

8.2% |

Out 2 Rounds |

12 (0.4%) |

5.4% |

16 (0.5%) |

8.7% |

Out 3 Rounds |

16 (0.5%) |

8.7% |

8 (0.3%) |

4.7% |

Out 4 Rounds |

7 (0.2%) |

5.6% |

3 (0.1%) |

2.0% |

Out 5+ Rounds |

45 (1.3%) |

4.3% |

12 (0.4%) |

|

Total |

3414 |

39.0% |

3045 |

Despite the fact that the early bird period has been conducted without interviewer outreach to respondents, NLS may not have saved very much collection effort in recent rounds by securing their early responses. NLS has spent significant interviewer outreach effort scheduling and rescheduling interview times or setting up future appointments for these respondents. In Round 30, for example, early bird respondents required about 5 attempts on average. Additionally, because interviews are almost entirely completed by phone, the cost of completing an early bird interview from a labor hours perspective is similar to completing an interview at any point in the round. This is in contrast to when early bird was first introduced and more interviews were conducted in person and other surveys where early respondents might complete via a less costly mode, such as web.

Finally, the setup of the early bird incentive has limited the ability of the NLS to make changes during the fielding period and adapt to needs in data collection. Because outbound outreach to respondents has been foregone until the end of the early bird period, mitigation strategies to be deployed if early bird response lags behind projections have been limited.

An alternative to offering an early bird incentive is to have NLS interviewers conduct direct outreach to sample members early in the round. It is possible that that this outreach will be as or more effective than the incentive in gaining completions, with lower costs.

For these reasons, NLS proposes an experiment to examine the effectiveness of early bird incentives in Round 31. In this experiment the fielded sample will be randomly assigned into one of three groups:

$30 early bird incentive without interviewer outreach (control group),

$30 early bird incentive with interviewer outreach (experimental group A), or

interviewer outreach without early bird incentive (experimental group B).

Having both experimental groups allows us to separately evaluate the effect of outbound outreach during the early bird period from the early bird incentive itself. Outreach in each experimental group will take a case managed approach where interviewers have an assigned set of cases for outreach and conduct a minimum of 5 and a maximum of 20 attempts for each respondent during the early bird period.

All respondents will be randomly assigned to one of the three groups with equal probability. Randomization will be stratified by replicate group so that outreach impacts can be adequately examined at all levels of respondent cooperation. Based on an approximate fielded sample (not including a small number of cases that have been excluded due to hostile refusals in prior rounds) of 8,560 respondents, NLS expects about 2,853 respondents in each of the three arms of the early bird experiment. This will give the experiment adequate power to detect moderate differences in response behavior among the groups, both at the end of the early bird period and at the end of the round. Using the average early bird completion rates from Round 29 and Round 30 combined, we would expect about 38% of the sample to complete the survey in the early bird period. Given the sample size, NLS would have 80% power (at the alpha = 0.05 level) to detect a significant difference in completion rate as small as 3.5 percentage points between groups. This difference would equate to approximately 100 additional (or fewer) completions during the early bird period in one treatment group versus another. The average non-deceased completion rate at the end of the round for Round 29 and Round 30 was 74%. Given the same sample size for the early bird experiment, NLS would have 80% power to detect a significant difference in completion rate as small as 3.2 percentage points between groups at the end of the round. This amounts to approximately 92 additional (or fewer) completions during the entire round in one treatment group versus another.

Missed Round Bonus

NLS proposes to offer an additional incentive payment for respondents who were not interviewed in the previous survey round(s). This missed round incentive reflects the increased incentives that were offered in Round 30 of the NLSY and are designed to bring respondents back to the NLSY panel and reinforce the long-term success of the NLSY79. This is especially critical as participants are dying at an increasing rate, decreasing the overall number of sample members available to participate. Anyone returning after only missing Round 30 would receive a $50 missed round incentive in Round 31. A respondent returning after two rounds out would receive a $60 missed round incentive and a respondent returning after three or more rounds out would receive a $70 missed round incentive. This graduated structure accounts both for the fact that the difficulty of gaining participation increases as the non-completion period increases and the fact that those returning from a long lapse in response will be asked to complete a longer interview (each interview traces the respondent’s job history back to the last completed interview).

Incentivizing completion among those who refused to respond in earlier waves has been found to be effective in several other longitudinal surveys as well as in the NLSY97. NLSY79 has implemented graduated missed round incentives in each of its last eight rounds; NLS believes that these missed round incentives have been important contributors to NLS’s continuing high retention rates. After offering incentive in Rounds 28 and 29 of $20, $30, and $40 were given to respondents returning after one, two, or three-plus rounds, respectively, NLS targeted these respondents in Round 30 by increasing these amounts to $50, $60, and $70, respectively. The results suggest that this targeting was quite effective. Table 5 shows that the completion rates of respondents in these groups were much higher in Round 30 than in Round 29. Respondents out for one round completed at 46.1% compared to 30.0% in Round 29; respondents with 2 rounds out completed at 35.3% compared to 16.2% in Round 29; and respondents with 3 rounds out completed at 22.5% compared to 13.6% in Round 29. Overall, 123 more responses were collected from these 3 groups than would have been collected if Round 29 response rates had been observed. As the additional $30 were paid to 397 respondents for a total of $11,910, the additional 123 responses cost an average of $96.82.

Table 5. NLSY79 Completion Rates by Prior Round Completion Patterns, Rounds 29-30

|

Missed Round Incentive |

Eligible |

Completed |

R30 Percent Completed |

R29 Percent Completed |

Perfect Responder |

$0 |

4239 |

4020 |

94.8% |

95.2% |

Completed R29 |

$0 |

2295 |

1996 |

87.0% |

85.4% |

1 Round Out |

$50 |

451 |

208 |

46.1% |

30.0% |

2 Rounds Out |

$60 |

184 |

65 |

35.3% |

16.2% |

3 Rounds Out |

$70 |

169 |

38 |

22.5% |

13.6% |

4 Rounds Out |

$70 |

149 |

24 |

16.1% |

|

5+ Rounds Out |

$70 |

1073 |

62 |

5.8% |

To gauge the cost effectiveness of this incentive, assume conservatively that we would require an additional 10 attempts to complete an interview, on average (respondents in Round 30 who missed 1-3 prior rounds required, on average, 18 outreach attempts to complete an interview). Using an estimate of 30 minutes per attempt, this translates to 5 hours of additional labor for these attempts, or $200 for each missed round respondent to complete the interview – well above the $96.82 cost of the incentive.

Given this success, and the fact that the number of respondents who have missed recent rounds remains high, we propose to maintain the Round 30 levels for missed round incentives. As shown in Table 6, if the impact on response continues at the level calculated for Round 30, the additional $30 per response compared to the R29 incentive amounts would result in 145 additional responses at an average cost of $90.33 per response. Even if this impact is cut in half, we would still expect 73 additional responses at an average cost of $150.65 per response. In both cases, the augmented incentive would be cost effective compared to a benchmark of $200 per response.

Table 6. Projected costs and number of additional completes for missed round incentives in Round 31, Respondents out 1 or More Rounds.

|

|

|

Assumed Response at R30 Level |

Assumed 50% of R30 Impact

|

||||

Prior Round Status |

R31 Eligible N |

R29 Response |

Rate |

Impact |

Cost |

Rate |

Impact |

Cost |

Out 1 Round |

518 |

30.0% |

46.1% |

83 |

$7,164 |

38.1% |

42 |

$5,913 |

Out 2 Rounds |

243 |

16.2% |

35.3% |

46 |

$2,573 |

25.8% |

23 |

$1,877 |

Out 3 Rounds |

119 |

13.6% |

22.5% |

11 |

$803 |

18.1% |

5 |

$644 |

Out 4 Rounds |

131 |

16.7% |

16.1% |

(1) |

$633 |

16.4% |

(0) |

$645 |

Out 5+ Rounds |

1,136 |

5.3% |

5.8% |

6 |

$1,942 |

5.6% |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

|

|

|

145 |

$13,115 |

|

73 |

$10,937 |

Cost per Additional Complete |

|

|

|

$90.33 |

|

|

$150.65 |

|

* Impacts are calculated as the difference in assumed completion rate in R31 and the actual completion rate in R29 multiplied by the projected number of eligible cases in R31. Assumed 50% of R30 impact assumes the R31 response rate for a given group will be the average of that group’s R29 and R30 response rates.

*Additional cost is calculated as $30 times the number of respondents.

Note that the positive impacts of these augmented incentives are concentrated among respondents who have not been out more than a few rounds. Accordingly, the approach we propose is definitively more cost effective than approaches that concentrate on longer-term non-respondents.

As with prior rounds, NLS will be careful to inform respondents that this is a one-time additional incentive in appreciation for their returning to the study after missing a previous round, and for the additional time and data needed to catch up in this interview round. NLS would inform them that they will not receive this additional amount next round (when they will be classified as prior round respondents). Based on prior experience in the NLSY79 and NLSY97, NLS anticipates that respondents will appreciate this premium and will understand the distinction between the base amount and the additional incentive. NLS also notes that missed round payments are also appropriate because these respondents tend to have slightly longer interviews as they catch up on reporting information from missed rounds.

Final Push Incentive

Starting after the first 12 weeks of the round, NLS will make cases that have not yet refused and had at least 6 contact attempts eligible for a final push incentive of up to $30 (bringing the total incentive, including the base incentive, to $100). Because these cases are among the most time-consuming and resource-intensive from which to gain cooperation, this impact represents a significant cost savings. As these cases, identified after many months of non-response, are all among the hardest to complete, the additional responses obtained are especially valuable to the survey’s representativeness. NLS offered this same amount in Round 29 and Round 30. Cases eligible for the final push are the survey’s most costly for completion and lead increasingly to elongated field periods. If a case has refused during initial outreach attempts, the case will be eligible for the final push incentive after 12 weeks regardless of the number of contact attempts made.

To facilitate a timely close to the fielding, starting 5 months after the start of fielding, all cases will be eligible for this incentive, after BLS and the contractors have discussed the exact timing of implementation. This represents a change of 1 month earlier from the timing used in Round 30. We propose this change since we expect the Early Bird experiment to increase completion rates early in the round and to close the data collection earlier than in Round 30. The intent is therefore to shift completion earlier in the round so that the earlier release of the final push incentive does not have a large impact on incentive costs.

This type of incentive has been shown to be effective in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, with little effect on noncontact rates (McGonagle and Freedman 2016). In addition, NLS conducted an experiment in Round 29 to evaluate the effectiveness of the final push on the NLSY79 sample. This experiment was conducted by randomly assigning interviewers into two separate groups. The first group had their cases eligible for the final push and enhanced final push at the traditional time, while the second group had their cases eligible for the final push and enhanced final push 6 weeks later. As shown in Table 7, after the 6-week treatment period the group receiving the incentive had significantly higher completion rates than the control group. Once the control group started receiving the incentive, their completion rates caught up.

Table 7: Final Push Evaluation Results (six-week treatment period)

Response Probability Group |

Final Push Experiment Group |

N |

Completes |

Pending |

Completion Rate |

High |

Treatment |

202 |

57 |

127 |

28.22% |

|

Control |

260 |

37 |

205 |

14.23% |

Mid |

Treatment |

451 |

84 |

321 |

18.63% |

|

Control |

479 |

64 |

355 |

13.36% |

Low |

Treatment |

955 |

29 |

708 |

3.04% |

|

Control |

742 |

14 |

582 |

1.89% |

Total |

Treatment |

1,608 |

170 |

1,156 |

10.57% |

|

Control |

1,481 |

115 |

1,142 |

7.77% |

*All statistics in the table reflect only the experimental time period from 3/29/2021-5/9/2021 when the treatment group was eligible for the final push incentive and the control group was not.

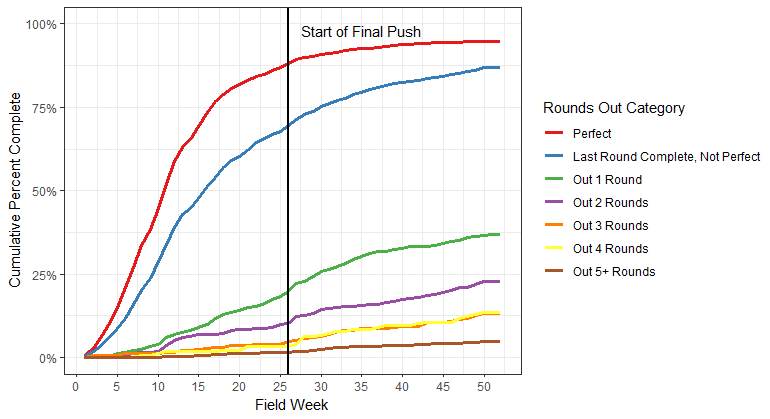

Non-experimental evidence from Round 30 corroborated the results of the Round 29 experiment as final push incentives increased response rates modestly. Figure 1 shows completion rates across time during Round 30 for groups having missed different amounts of previous rounds. The vertical line denotes the 3/20/23 start of final push. The introduction of the incentive coincided with a modest increase in the slopes of each line, suggesting that final push increased response rates modestly.

Figure 1. Completion Rates Before and After Start of Final Push, NLSY79 Round 30

Enhanced Final Push

Maintaining a sample that is balanced across demographic characteristics is essential to supporting research across the life cycle. To the end of bolstering the representativeness of the NLSY79 sample, NLS will offer an “Enhanced Final Push” incentive that targets a $50 final push amount instead of the $30 final push amount (an extra $20) for a subgroup of cases that had low response rates. NLS offered this same amount in Round 29 and Round 30. Once extended, this offer will remain in place for the remainder of the field period (as will the traditional final push incentive).

The subgroups NLS proposes to evaluate for inclusion in the enhanced final push will be chosen to represent groups that directly concern labor market activity: educational attainment, Armed Force Qualifying Test (AFQT) score, weeks worked (defined in 4 categories), presence or absence of a health condition that limits work activity, and each of these stratified by gender or race/ethnicity. For each possible subgroup, NLS will calculate the overall response rate for the subgroup on the earliest date between a) when the total sample completion rate is 60 percent or b) January 25, 2025. For reference, the total sample completion rate reached 60% on February 22 in Round 30. Any subgroup having a response rate at least 7 percent below the sample average (i.e., less than 53 percent) will be offered the enhanced $50 final push amount instead of the typical $30 final push amount that is approved for all remaining cases.

Results from NLSY79 Round 29, shown in Table 8, suggest that the enhanced final push had a positive impact on survey completion. Here, the group designated “Eligible for Enhanced Final Push” includes all individuals who would have been eligible for the enhanced final push if they had not completed the Round 29 interview as of the start of final push. The first two sets of columns present completion rates at the 60% mark and at the start of final push, respectively. The third set of columns presents the cumulative completion rate of these groups when fielding concluded.

Table 8: Round 30 Enhanced Final Push Results

|

At 60% Completion |

At Start of Final Push |

Cumulative at End of Round |

||||||

N |

Complete |

% Complete |

N |

Complete |

% Complete |

N |

Complete |

% Complete |

|

Not Eligible for Enhanced Final Push |

5,585 |

3,889 |

69.6% |

5,585 |

4,104 |

73.4% |

5,585 |

4,676 |

83.7% |

Eligible for Enhanced Final Push |

2,975 |

1,338 |

45.0% |

2,975 |

1,440 |

48.4% |

2,975 |

1,737 |

58.4% |

At the start of the final push, 48.4% of respondents in the group eligible for the enhanced final push had completed an interview, compared to 73.4% of other respondents. After the final push went into effect, the enhanced final push group completed at a higher rate (10 percentage point improvement in the completion rate and 21% increase) compared to the other respondents (10.3 percentage point increase, a 13% increase), providing suggestive evidence that the enhanced final push was successful. NLS previously has seen similar results when implementing a final push incentive in Round 28 and 29, which compared favorably to the results in Round 27 (when no final push incentive was offered).

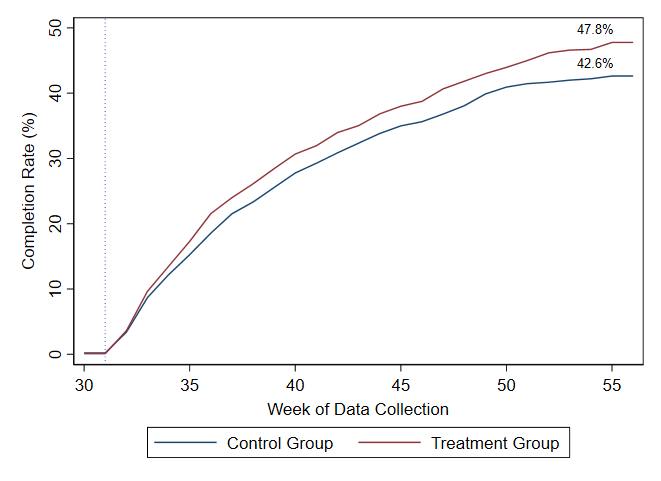

In Round 20 of the NLSY97, NLS followed on these suggestive results by conducting an experiment in which about half of the potentially eligible respondents were randomly chosen to receive the enhanced final push incentive and the other half served as a control. The results of the experiment, shown in Figure 2, indicate substantial effectiveness of the incentive. A gap in completion rates between treatment and control respondents began to emerge shortly after the introduction of the incentive and continued to grow over the rest of the round. At the end of data collection, the completion rate for the treatment group was 5.2 percentage points higher than the completion rate for the control group, with 47.8% in the treatment group completing compared to 42.6% in the control group.

Figure

2: Results of the Round 20 Enhanced Final Push Experiment

In-Kind Incentives

NLS proposes to offer in-kind gifts, in mailings or door hangers, for as many as 2,400 respondents. These gifts would have a maximum value of $12 and average only $10. Many NLS interviewers report that having something to offer respondents, such as a monetary incentive, additional in-kind offering, or new conversion materials, allows them to open the dialogue with formerly reluctant respondents. They find it useful for gaining response if they have a variety of options to respond to the particular needs, issues, and objections of the respondent. NLS has used similar gifts in many recent rounds to strengthen the ongoing relationships between the program and its respondents. NLS would like to have the ability to include a token in a mailing that either makes the envelope heavier or comes in a box, and thus may induce cooperative behavior from the respondent such as opening the mail, reading the message, engaging with the project through calls to the 800 number, setting a web appointment, or responding when the interviewer calls or stops by. Decisions for who receives the in-kind incentives would be made by NORC central office, and interviewers would not have discretion over which respondents received this incentive.

Although the value of the in-kind offerings that NLS is proposing is small, the benefit is useful in inducing respondents to engage outreach attempts and interviewers to make outreach. NLS’s goal will be to use these small tokens broadly across the sample. Because the value of the proposed items is small, NLS will not prevent circumstances where a respondent may be the recipient of more than 1 offer. However, no respondents will receive all in-kind offers.

Gatekeeper Incentives

Some “gatekeepers” are particularly helpful in tracking down reluctant sample members. For example, a parent or sibling not in the survey may provide locating information or encourage a sample member to participate. (Note that NLS never reveals the name of the survey to these gatekeepers; it is described simply as “a national survey.”) NLS often returns to the same gatekeepers round after round. To maintain their goodwill, NLS will offer gatekeepers who are particularly helpful a small gift worth about $5. NLS has offered a similar incentive in Rounds 26-30 of the NLSY79 and Rounds 15-21 of the NLSY97. It is used very infrequently but has proven effective in finding respondents and getting them to complete interviews.

Incentive Costs

We estimate the total incentives costs for R31 to be $595,929, which includes $470,429 for the base and missed round incentives and $125,500 for the additional incentives, including early bird, final push, enhanced final push, in-kind and gatekeeper incentives. A table listing the total cost of incentives by respondent pool is provided below.

Table 9. Round 31 Incentive Costs for Main NLSY79 Sample

Incentive Type |

R30 Completers |

Missed R30 |

Missed R29-R30 |

Missed R28-R30 |

Sample size* |

6413 |

518 |

243 |

|

Expected completes |

92.07% |

46.12% |

35.33% |

8.91% |

Base |

$70 |

$70 |

$70 |

$70 |

Missed Round(s) |

|

$50 |

$60 |

$70 |

Total from Base and Missed Round |

$413,311 |

$28,668 |

$11,161 |

$17,289 |

Total from Above Row |

||||

Other Incentives |

||||

Early Bird (Experiment) |

$30 for an estimated 2,000 respondents = $60,000 total. |

|||

Final Push |

$30 for an estimated 1,150 respondents = $34,500 total. |

|||

Enhanced Final Push |

$20 for an estimated 345 respondents = $6,900 total. |

|||

In-Kind |

$10 for an estimated 2,400 respondents = $24,000. |

|||

Gatekeeper |

$5 for an estimated 20 respondents = $100 |

|||

Total from Other Incentives |

$125,500 |

|||

Grand Total |

||||

* Note: Sample sizes exclude deceased and blocked cases. Expected completes and R31 sample size based on completion rates of similar groups in R30.

Electronic Payment of Incentives

In Rounds 27-30, NLS offered respondents the opportunity to receive their incentive payment via electronic methods (specifically, PayPal and Online Mobile Banking). During the NLSY79 Round 31 main field period, NLS will continue offering this option to telephone interview respondents. The attraction of electronic payment is large for both respondents and the NLS program. For respondents, electronic payment will generally involve less effort to receive funds than would a paper check or money order. Furthermore, the NLS program can save administration costs and mailing costs by making electronic payments. The cost is also much lower if a payment needs to be tracked or a respondent does not recall having received it. Electronic transaction options are expanding markedly, for example, PayPal, GoogleWallet, ApplePay, Zelle, etc., and NLS can expect the options during NLSY79 Round 31 main fielding to be even greater than those available today.

Summary

Overall, there are about 2,500 sample members who are hard to interview in the NLSY79, either because of busy schedules or a mindset that ranges from indifference to hostility. While there is no single strategy for reaching all respondents, the incentive plan laid out above provides a structure for engaging these respondents and provides flexibility in how NLS approaches sample members.

NLS reiterates that incentive payments are only part of the approach to encouraging response. An equally important part of the effort is designing an effective campaign for gaining cooperation, including conversion materials that interviewers can use to respond to sample members who provide a variety of reasons for not completing the interview. This portfolio of respondent materials backs up the interviewer, providing a variety of approaches to converting refusals. NLS also carefully plans outreach throughout the round, encourages national teamwork among the interviewers and periodic calls among interviewers to share their successful “tricks of the trade” with each other, and uses conversion materials to help reach respondents. With a combination of core study materials, the ability to personalize their approach to each respondent, and incentives such as in-kind bonuses that provide another selling point, interviewers will have the support they need to successfully persuade respondents. We also continue to further refine approaches to outreach, including how case groups are released, the effort expended on groups of cases, and the sequencing and mode of contacts during the field period.

NLS’s primary goal must be to continue to value the respondents, including their time, interest, and preferences. Angering sample members is not an option in the face of their ability to screen and reject interviewer’s calls. NLS’s incentive efforts and contacting approach will continue NLS’s efforts to motivate sample members, assuage their concerns, and convey NLS’s interest in them as individuals, not numbers.

References

Creighton, K. P., King, K. E., & Martin, E. A. (2007). The use of monetary incentives in Census Bureau longitudinal surveys. Survey Methodology, 2.

Martin, E., & Winters, F. (2001). Money and motive: effects of incentives on panel attrition in the survey of income and program participation. Journal of Official Statistics, 17(2), 267.

McGonagle, K. A., & Freedman, V. A. (2017). The effects of a delayed incentive on response rates, response mode, data quality, and sample bias in a nationally representative mixed mode study. Field methods, 29(3), 221-237.

Rodgers, W. L. (2011). Effects of increasing the incentive size in a longitudinal study. Journal of Official Statistics, 27(2), 279.

10. Describe any assurance of confidentiality provided to respondents and the basis for the assurance in statute, regulation, or agency policy.

a. BLS Confidentiality Policy

The information that NLSY79 respondents provide is protected by the Privacy Act of 1974 (DOL/BLS–13, NLSY79 Database (81 FR 25788)) and the Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act (CIPSEA).

CIPSEA safeguards the confidentiality of individually identifiable information acquired under a pledge of confidentiality for exclusively statistical purposes by controlling access to, and uses made of, such information. CIPSEA includes fines and penalties for any knowing and willful disclosure of individually identifiable information by an officer, employee, or agent of the BLS.

Based on this law, the BLS provides respondents with the following confidentiality pledge/informed consent statement:

“We want to reassure you that your confidentiality is protected by law. In accordance with the Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act, the Privacy Act, and other applicable Federal laws, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, its employees and agents, will, to the full extent permitted by law, use the information you provide for statistical purposes only, will hold your responses in confidence, and will not disclose them in identifiable form without your informed consent. All the employees who work on the survey at the Bureau of Labor Statistics and its contractors must sign a document agreeing to protect the confidentiality of your information. In fact, only a few people have access to information about your identity because they need that information to carry out their job duties.

Some of your answers will be made available to researchers at the Bureau of Labor Statistics and other government agencies, universities, and private research organizations through publicly available data files. These publicly available files contain no personal identifiers, such as names, addresses, Social Security numbers, and places of work, and exclude any information about the States, counties, metropolitan areas, and other, more detailed geographic locations in which survey participants live, making it much more difficult to figure out the identities of participants. Some researchers are granted special access to data files that include geographic information, but only after those researchers go through a thorough application process at the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Those authorized researchers must sign a written agreement making them official agents of the Bureau of Labor Statistics and requiring them to protect the confidentiality of survey participants. Those researchers are never provided with the personal identities of participants. The National Archives and Records Administration and the General Services Administration may receive copies of survey data and materials because those agencies are responsible for storing the Nation’s historical documents.”

BLS policy on the confidential nature of respondent identifiable information (RII) states that “RII acquired or maintained by the BLS for exclusively statistical purposes and under a pledge of confidentiality shall be treated in a manner that ensures the information will be used only for statistical purposes and will be accessible only to authorized individuals with a need-to-know.”

By signing a BLS Agent Agreement, all authorized agents employed by the BLS, contractors and their subcontractors pledge to comply with the Privacy Act, CIPSEA, other applicable federal laws, and the BLS confidentiality policy. No interviewer or other staff member is allowed to see any case data until the BLS Agent Agreement, Department of Labor Rules of Conduct, BLS Confidentiality Training certification, and Department of Labor Information Systems Security Awareness training certification are on file. Respondents will be provided a copy of the questions and answers shown in Attachment 6 about uses of the data, confidentiality, and burden. These questions and answers appear on the back of the letter that respondents will receive in advance of the Round 31 interviews.

b. CHRR and NORC Contractor Confidentiality Safeguards

BLS contractors (CHRR and NORC) have safeguards to provide for the security of NLS data and the protection of the privacy of individuals in the sampled cohorts. These measures are used for the NLSY79 as well as the other NLS cohorts. Safeguards for the security of data include:

1. Storage of printed survey documents in locked space at NORC.

2. Protection of computer files at CHRR and NORC against access by unauthorized individuals and groups. Procedures include using passwords, high-level “handshakes” across the network, data encryption, and fragmentation of data resources. As an example of fragmentation, should someone intercept data files over the network and defeat the encryption of these files, the meaning of the data files cannot be extracted except by referencing certain cross-walk tables that are neither transmitted nor stored on the interviewers’ laptops. Not only are questionnaire response data encrypted, but the entire contents of interviewers’ laptops are now encrypted. Interview data are periodically removed from laptops in the field so that only information that may be needed by the interviewer is retained. If a laptop is lost or stolen it can be wiped clean remotely.

3. Protection of computer files at CHRR and at NORC against access by unauthorized persons and groups. Especially sensitive files are secured through a series of passwords to restricted users. Access to files is strictly on a need-to-know basis. Passwords change every 90 days.

4. To assure the CHRR and its subcontractor NORC are in compliance with the Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 (FISMA) and adequately monitoring all cybersecurity risks to NLS assets and data, in addition to regular self-assessments, the NLS system undergoes a full NIST 800-53 audit every 3 years using an outside independent cybersecurity auditing firm.

Protection of the privacy of individuals is accomplished through the following steps:

1. Oral permission for the interview is obtained from all respondents, after the interviewer ensures that the respondent has been provided with a copy of the appropriate BLS confidentiality information and understands that participation is voluntary.

2. Information identifying respondents is separated from the questionnaire and placed into a non-public database. Respondents are then linked to data through identification numbers.

3. The public-use version of the data, available on the Internet, masks or removes data that are of sufficient specificity that individuals could theoretically be identified through some set of unique characteristics.

4. Other data files, which include variables on respondents’ State, county, metropolitan statistical area, zip code, and census tract of residence and certain other characteristics, are available only to researchers who undergo a review process established by BLS and sign an agreement with BLS that establishes specific requirements to protect respondent confidentiality. These agreements require that any results or information obtained as a result of research using the NLS data will be published only in summary or statistical form so that individuals who participated in the study cannot be identified. These confidential data are not released to researchers without express written permission from NLS and are not available on the public use internet site.

5. In Round 31 NLS will continue several training and procedural changes to increase protection of respondent confidentiality. These include an enhanced focus on confidentiality in training materials, clearer instructions in the Field Interviewer Manual on what field interviewers may or may not do when working cases, and formal separation procedures when interviewers complete their project assignments. Online and telephone respondent locating activities have been relocated from NORC’s geographically dispersed field managers to locating staff in NORC’s central offices. Respondent social security numbers were separated from NORC and CHRR records during Round 23.

11. Provide additional justification for any questions of a sensitive nature, such as sexual behavior and attitudes, religious beliefs, and other matters that are commonly considered private. This justification should include the reasons why the agency considers the questions necessary, the specific uses to be made of the information, the explanation to be given to persons from whom the information is requested, and any steps to be taken to obtain their consent.

Several sets of questions in the NLSY79 might be considered sensitive. This section describes these questions and explains why they are a crucial part of the data collection. All of these topics have been addressed in previous rounds of the surveys, and respondents generally have been willing to answer the questions. Respondents are always free to refuse to answer any question that makes them feel uncomfortable.