Five-Year Strategic and Implementation Plan for the Engines Program

Grantee Reporting Requirements for NSF Regional Innovation Engines (NSF Engines) Program

SWOT analyses_component plan guidance_updated

Five-Year Strategic and Implementation Plan for the Engines Program

OMB:

NSF Engines’ Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunity and Threat (SWOT) Analysis1

The Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunity, and Threat (SWOT) analysis is an organized approach to self-assess the strengths, weaknesses, gaps, opportunities, and challenges inherent in the development of products, technologies, and services. NSF is requesting a SWOT analysis in three areas: research, development, and translation (RD&T); workforce development; and broadening participation. The results of this analysis should stimulate thinking about options to maximize strengths and opportunities, address gaps and challenges, and mitigate potential weaknesses. It is not intended to be an evaluation of the importance or value of an Engine.

The NSF Engines’ SWOT analysis is guided by rubrics. Established at the start of a program, rubrics should foster discussions that inform the design and content of strategic documents, establish expectations for outcomes, and guide progress.

The rubrics are comprised of three components:

Topics: Conceptual areas of the program or project essential to its successful development and implementation.

Criteria: Characteristics or descriptors inherent in a topic.

Degrees of attainment: Steps along a continuum to fully achieve a criterion.

They are provided in Section B.

Instructions to Complete the SWOT Analysis

Content for the SWOT analysis. As a retrospective assessment, any information germane to the current status of the Engine—for example, your Engine proposal, any documentation used to develop the proposal, all documents and reports developed in response to NSF requests since notification of the award, and any other information you deem relevant—could be used to respond to the rubrics.

Framework for assessing each criterion. Each criterion in the rubric should be examined through the lens of strengths, weaknesses, gaps, opportunities, and challenges. These assessments may include initial thinking on options to maximize strengths and opportunities, address gaps and challenges, and mitigate potential weaknesses.

Engines are composed of a multiplicity of projects, partnerships, services, and other elements. For criteria for which there is more than one project, technology, or partnership, a SWOT analysis should be performed for each so that a detailed understanding of the status of all elements critical to the success of the Engine is obtained. Information from prior documents may apply to more than one criterion, and some repetitive use of information is anticipated.

Determining the degree of attainment. The information derived from the SWOT analysis is used to determine the degree of attainment that reflects the current status of the Engine for that criterion. The degrees build sequentially from 0 to 4, where zero is no evidence, one is preliminary, two is intermediate, three is advanced, and four is mature. The selection of the degree of attainment assumes prior degrees have been completed. At this early stage of Engine development, there is great variability in the progress to establish the Engines. Many of the criteria are anticipated to be at the preliminary, possibly the intermediate, degree of attainment, and future analyses will show advancement over time. For criteria that are not applicable to an Engine program, please indicate that in the no evidence column.

While all information that surfaces during the SWOT analysis is valuable, the narrative for each criterion should reflect current status and include a rationale and evidence for the selection of the degree of attainment. This may require distinction between retrospective information that assesses the current status as opposed to prospective information that may surface during the analysis and be applicable to future planning.

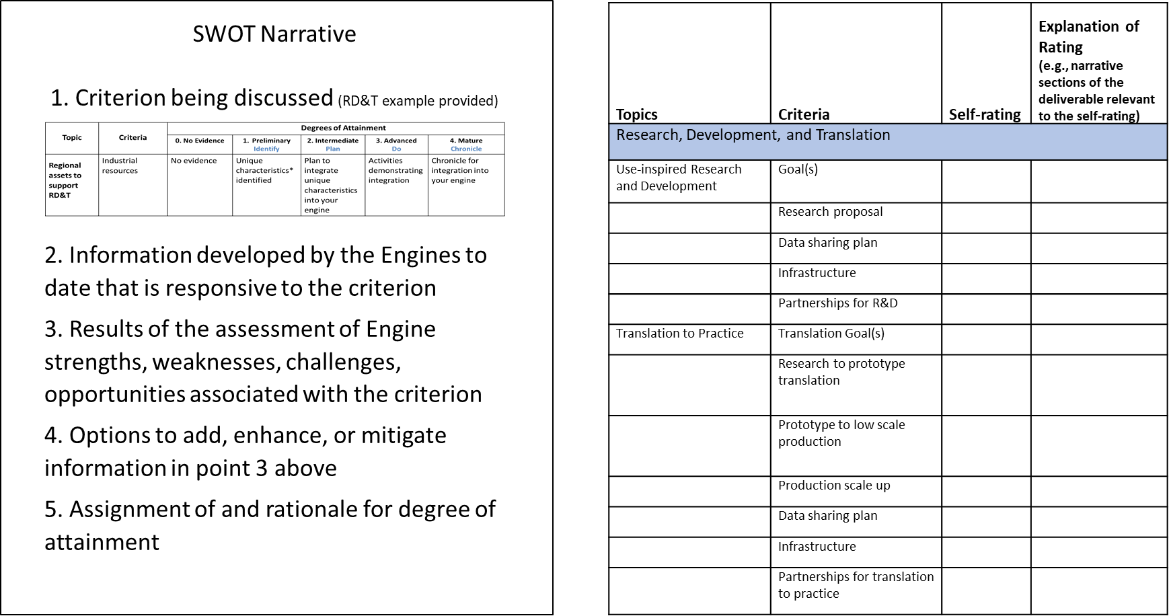

Documents constituting the NSF deliverable. The deliverable for the SWOT analysis will consist of a document containing the narrative supporting the rubrics ratings and an index that indicates the location of the main text and relevant information detailed in other criteria that support the rating. The narrative should summarize the results of this exercise, and an example narrative format is provided below. The index is provided in full in Appendix A.

Example Response Formats

Submission process. NSF will provide instructions to access a SharePoint site in a separate document.

Questions about the SWOT analysis. NSF will provide contact information for Engines to obtain assistance with the SWOT analysis in a separate email.

SWOT Rubrics

The rubrics in this section are responsive to the NSF request for rubrics to conduct SWOT analyses for RD&T (Section A), Workforce Development (Section B), and Broadening Participation (Section C).

Section A. Research, Development, and Translation for Ecosystem Development

Topic |

Criteria |

Degrees of Attainment |

||||

0. No Evidence |

1. Preliminary |

2. Intermediate |

3. Advanced |

4. Mature |

||

Use-inspired Research and Development (Criteria under this topic should be iterated as appropriate for each product, technology, or service that is being developed through the Engine)

|

R&D Goal(s) |

No evidence |

R&D concepts for developing Engine products, technologies, or services identified |

R&D concepts integrated into a set of R&D goals |

Initial R&D activities to make progress on goals identified |

Initial R&D activities to make progress on goals launched |

Research approach to achieve each goal |

No evidence |

R&D activities for each goal identified |

R&D activities integrated into a plan |

R&D activities initiated |

Evidence for continuing R&D activities |

|

Data sharing plan |

No evidence |

Data that should be shared identified |

Plan to share data |

Activities detailing steps to share data |

Evidence for continuing data sharing activities |

|

Infrastructure |

No evidence |

Components of R&D infrastructure identified |

Logistics plan for use, maintenance, and sustainability |

Activities demonstrating use, maintenance, and sustainability |

Evidence for continuing activities |

|

Partnerships for R&D |

No evidence |

Partners identified |

Plan to align partners with R&D goals |

Activities demonstrating alignment |

Evidence for continuing activities |

|

Topic |

Criteria |

Degrees of Attainment |

||||

0. No Evidence |

1. Preliminary |

2. Intermediate |

3. Advanced |

4. Mature |

||

Translation to Practice

(Criteria under this topic should be iterated as appropriate for each product, technology, or service that is being developed through the Engine)

|

Translation Goal(s) |

No evidence |

Steps to translate prototype product, technology, or service identified |

Translation steps integrated into translation to practice goals |

Adoption readiness levels for each goal are identified |

Goals integrated for translation to adoption activities |

Research to prototype translation |

No evidence |

Translation steps for proof-of-concept to prototype development identified |

Plan to achieve prototype development developed |

Activities related to prototype development |

Evidence for continuing activities demonstrating prototype feasibility |

|

Prototype to low scale production |

No evidence |

Low scale production design elements identified |

Plan to integrate design elements |

Activities related to low scale production of prototype |

Evidence for continuing activities for low scale production |

|

Production scale up |

No evidence |

Production scale up design elements identified |

Plan to integrate design elements identified |

Activities to establish a production environment |

Evidence for continuing activities to establish a production environment |

|

Data sharing plan |

No evidence |

Data that should be shared identified |

Plan to share data |

Activities detailing steps to share data |

Evidence for continuing data sharing activities |

|

Infrastructure |

No evidence |

Components of translation infrastructure identified |

Logistics plan for use, maintenance, and sustainability |

Activities demonstrating use, maintenance, and sustainability |

Evidence for continuing activities |

|

Partnerships for translation to practice |

No evidence |

Partners identified |

Plan to align partners with translation goals |

Activities demonstrating alignment |

Evidence for continuing activities |

|

*Adoption readiness levels (ARLs) are a complement to technology readiness levels (TRLs) and manufacturing readiness levels (MRLs). ARLs assess the adoption risks of a technology and translate this risk assessment into the readiness of a technology to be adopted by the ecosystem. https://www.energy.gov/technologytransitions/adoption-readiness-levels-arl-complement-trl

*Preliminary

degree of attainment for industrial resources: unique

characteristics could be a capacity; capability; critical access to

piece of equipment; materials and supplies; academic institutions,

industries, and other physical locations; unique geography, or

economic conditions.

**Entrepreneurial

resources include funding programs such as the Small Business

Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer

(STTR) Programs and Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA)

Programs; business networks, councils, and centers, such as the

Small Business Development Centers and Chambers of Commerce; and

entrepreneur blogs, podcasts, and websites sponsored by industry

groups and universities.

(https://www.purdueglobal.edu/blog/business/entrepreneur-resources)

***Environmental

resources generally refer to natural resources such as air, water,

and soil.

(https://www.fs.usda.gov/science-technology/water-air-soil).

The term has been expanded to include any material, service, or

information from the environment that is valuable to society.

Examples include food from plants and animals; wood for cooking,

heating, and building; and metals, coal, and oil.

(https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/environmental-resources)

Topic |

Criteria |

Degrees of Attainment |

||||

0. No Evidence |

1. Preliminary |

2. Intermediate |

3. Advanced |

4. Mature |

||

Regional Assets to Support RD&T Ecosystem Development |

Industrial resources |

No evidence |

Unique characteristics* identified |

Plan to integrate unique characteristics into your engine |

Activities demonstrating integration |

Evidence for continuing integration into your engine |

Academic resources |

No evidence |

Unique characteristics identified |

Plan to integrate unique characteristics into your engine |

Activities demonstrating integration |

Evidence for continuing integration into your engine |

|

Entrepreneurial resources** |

No evidence |

Unique characteristics identified |

Plan to integrate unique characteristics into your engine |

Activities demonstrating integration |

Evidence for continuing integration into your engine |

|

Environmental resources*** |

No evidence |

Unique characteristics identified |

Plan to integrate unique characteristics into your engine |

Activities demonstrating integration |

Evidence for continuing integration into your engine |

|

Access to critical supply chains |

No evidence |

Identify supply chains |

Plan to secure supply chains |

Activities demonstrating supply chains secured |

Evidence for continuing supply chain deliveries |

|

Topic |

Criteria |

Degrees of Attainment |

||||

0. No Evidence |

1. Preliminary |

2. Intermediate |

3. Advanced |

4. Mature |

||

Regional RD&T Ecosystem Development |

Essential elements of a regional innovation ecosystem |

No evidence |

Elements of ecosystem identified |

Relationship of elements to region of service and regional innovation ecosystem identified |

Plan to leverage engine to build the ecosystem |

Activities that lay the groundwork for the ecosystem initiated |

Ecosystem partnerships |

No evidence |

Partnerships representative of the Engine’s inclusive engagement goals identified |

Plan to integrate partnerships into regional ecosystem |

Outreach activities to partnerships that align with regional ecosystem |

Evidence for continuing outreach activities |

|

Staffing for the engine |

No evidence |

Unique regional workforce skills identified |

Plan to integrate workers into the engine staffing as required by goals of your engine |

Activities demonstrating integration |

Evidence for continuing integration into your engine |

|

Workforce to develop region of service |

No evidence |

Unique regional workforce skills identified |

Plan to attract appropriately skilled workers to the region |

Activities demonstrating actions to attract appropriately skilled workers to the area |

Evidence for continuing increases in regional skilled workers |

|

Regulatory assessment |

No evidence |

Regulatory implications of products and processes identified |

Regulatory implications discussed with appropriate regulatory group(s) |

Activities planned to address regulatory implications |

Activities to address regulatory implications initiated |

|

Economic plan for a sustainable ecosystem |

No evidence |

Financial requirements to establish ecosystem estimated |

Budget to achieve financial requirements outlined |

Plan to achieve financial requirements |

Evidence for continuing activities to achieve financial requirements initiated |

|

Inclusive engagement plan |

No evidence |

Principles for inclusive engagement identified |

Principles translated into action plan |

Engagement activities initiated |

Evidence for continuing activities |

|

Communication plan |

No evidence |

Principles for inclusive communication identified |

Principles translated into action plan |

Inclusive communication activities initiated |

Evidence for continuing activities |

|

Section B. Workforce Development within the Region of Service

Topic |

Criteria |

Degrees of Attainment |

||||

0. No Evidence |

1. Preliminary |

2. Intermediate |

3. Advanced |

4. Mature |

||

Labor Market for Engine-relevant industries within Region of Service |

Inventory of industries and employers in the region of service [Labor Demand] |

No evidence |

Identify the main industries and employers in the region |

Plans to leverage the main industries and employers of the region |

Implement activities to leverage primary Engine-related industries and employers of the region |

Continuing evidence for activities that align with workforce development goals |

Inventory of talent in region of service [Labor Supply] |

No evidence |

Identify the labor supply of the region (including graduating students, and non-traditional labor sources*) |

Plans to leverage institutions of higher education (IHEs), trade organizations, and other labor suppliers of the region |

Implement activities to leverage the IHEs, trade organizations, and other labor suppliers of the region |

Continuing evidence for activities that align with workforce development goals |

|

*Non-traditional labor sources are communities that are traditionally underrepresented in the labor market; they may include formerly incarcerated populations, Tribal populations, etc.

Topic |

Criteria |

Degrees of Attainment |

||||

0. No Evidence |

1. Preliminary |

2. Intermediate |

3. Advanced |

4. Mature |

||

Skills and Training for Workforce Development within Region of Service |

Education Requirements |

No evidence |

Identify educational requirements for skilled workforce for Engine-relevant industries |

Align educational requirements with regional education ecosystem |

Outreach activities to regional education programs |

Continuing evidence for regional education activities |

Workforce Development Goals |

No evidence |

Identify Engine’s workforce development goals for region of service |

Identify activities to reach workforce development goals |

Implement activities |

Continuing evidence for activities that align with workforce development goals |

|

Training programs to reach workforce development goals in Engine-relevant industries |

No evidence |

Identify skills needed for Engine’s workforce development goals |

Planning for training programs in the region |

Implement training programs |

Continuing evidence for training program activities |

|

Trainings related to increasing regional entrepreneurship |

No evidence |

Identify skills needed to increase regional entrepreneurship |

Planning for training programs in the region |

Implement training programs |

Continuing evidence for entrepreneurial training program activities |

|

Trainings related to increasing the resiliency of the workforce (capable of moving across industries) |

No evidence |

Identify skills needed to increase workforce resiliency |

Planning for training programs in the region |

Implement training programs |

Continuing evidence for resiliency training program activities |

|

Topic |

Criteria |

Degrees of Attainment |

||||

0. No Evidence |

1. Preliminary |

2. Intermediate |

3. Advanced |

4. Mature |

||

Partnerships for Workforce Development within Region of Service |

Institutes of higher learning (post-secondary school) |

No evidence |

Partners identified |

Plan to align partners with workforce development goals |

Activities demonstrating alignment |

Continuing evidence for regional partnership activities |

Private sector (for-profit companies, VCs, angel investors, etc.) |

No evidence |

Partners identified |

Plan to align partners with workforce development goals |

Activities demonstrating alignment |

Continuing evidence for regional private sector activities |

|

Trade organizations (economic development organizations, trade unions, chambers of commerce, etc.) |

No evidence |

Partners identified |

Plan to align partners with workforce development goals |

Activities demonstrating alignment |

Continuing evidence for regional trade organization activities |

|

Public sector (local, State, and Federal Governments) |

No evidence |

Partners identified |

Plan to align partners with workforce development goals |

Activities demonstrating alignment |

Continuing evidence for regional public sector activities |

|

Nonprofit sector (community organizations, NGOs, etc.) |

No evidence |

Partners identified |

Plan to align partners with workforce development goals |

Activities demonstrating alignment |

Continuing evidence for regional education activities |

|

Section C. Broadening Participation

Topic |

Criteria |

Degrees of Attainment |

||||

0. No Evidence |

1. Preliminary |

2. Intermediate |

3. Advanced |

4. Mature |

||

Outreach |

Engagement with new and established communities and geographies |

No evidence |

Principles for inclusive engagement identified |

Principles translated into action plan that broadens participation |

Engagement activities to achieve the action plan initiated |

Evidence for continuing activities demonstrating inclusive engagement |

Communication with new and established communities and geographies |

No evidence |

Principles for inclusive communication identified |

Principles translated into action plan |

Communication activities to demonstrate outreach initiated |

Evidence for continuing activities demonstrating communication and outreach |

|

Engine staff |

Individuals representative of the Engine’s goals for inclusive engagement for their region of service |

No evidence |

Representative participants that align with engine goals for inclusive engagement identified |

Plan to determine participants that align with engine goals and region of service |

Outreach activities to participants that align with engine goals and region of service |

Evidence for continuing outreach activities demonstrating alignment with engine goals and region of service |

Access path to join engine |

No evidence |

Steps in access identified |

Steps integrated into a process to join engine |

Activities to initiate access process |

Evidence for continuing activities demonstrating access to join engine |

|

Staff participation in strategic planning |

No evidence |

Options for participation identified |

Stakeholder consensus on options obtained |

Activities that demonstrate options initiated |

Evidence for continuing activities demonstrating stakeholder participation in strategic planning |

|

Staff participation in decision making |

No evidence |

Options for participation identified |

Stakeholder consensus on options obtained |

Activities that demonstrate options |

Evidence for continuing activities demonstrating stakeholder participation in decision making |

|

Topic |

Criteria |

Degrees of Attainment |

||||

0. No Evidence |

1.Preliminary |

2. Intermediate |

3. Advanced |

4. Mature |

||

Broadening Participation for Partnerships |

Representative of the Engine’s inclusion goals for their region of service |

No evidence |

Representative partnerships that align with engine goals identified |

Plan to identify partnerships that align with engine goals |

Outreach activities to partnerships that align with engine goals |

Evidence for continuing partnership outreach activities |

Access path to join engine |

No evidence |

Steps in access identified |

Steps integrated into a process |

Activities for access to join partnership initiated |

Evidence for continuing partnership access activities |

|

Partnership participation in strategic planning |

No evidence |

Options for participation identified |

Partnership consensus on options obtained |

Activities that demonstrate options initiated |

Evidence for continuing activities demonstrating partnership participation in strategic planning |

|

Partnership participation in decision making |

No evidence |

Options for participation identified |

Partnership consensus on options obtained |

Activities that demonstrate options initiated |

Evidence for continuing activities demonstrating partnership participation in decision making |

|

Broadening Participation for Workforce Development

|

Representative of the Engine’s goals for inclusive engagement for their region of service |

No evidence |

Representative workforce that aligns with engine goals for inclusive engagement identified |

Plan to develop workforce that aligns with engine goals for inclusive engagement |

Outreach activities to workers to develop engine workforce |

Evidence for continuing workforce outreach activities |

Opportunities to broaden participation in workforce recruitment |

No evidence |

Identified recruitment challenges to broadening participation in region of service |

Identify solutions to broadening participation recruitment challenges |

Initiate recruitment activities to meet broadening participation goals |

Evidence for continuing recruitment activities that broaden workforce participation |

|

Access to professional development opportunity |

No evidence |

Identified challenges to access to professional development |

Identified solutions to professional development accessibility challenges |

Implement activities to increase access to professional development |

Evidence for continuing activities increases access to professional development |

|

Compensation parity |

No evidence |

Regional skill-based compensation norms identified |

Plan to achieve regional consensus on compensation norms |

Activities detailing steps to achieve consensus |

Evidence for activities that would achieve regional compensation norms |

|

(Optional) Other Criteria Relevant to your Engine

Engines have the option to propose additional criteria that are relevant to the Engine but not included in the rubrics above. While it is anticipated that a criterion would be accompanied by the rationale for inclusion and a description of the strengths, weaknesses, challenges, and opportunities, an enumeration of the degrees of attainment is welcome, but not required.

Example Format

Topic |

Criteria |

Reasoning |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Example Template for the SWOT Analysis Component Plan

The following is an example template for organizing the SWOT Analysis section of the Strategic and Implementation Plan. Teams are NOT required to use this template but should include a summary of their SWOT as part of this section of the Plan.

Introduction

[[Explanation of how the analysis will inform the Engine’s strategic decision-making and planning.]]

II. Summary of SWOT

[[The purpose of this section is to summarize the outcomes of the Engine’s detailed SWOT analysis. The goal is not to list every strength, weakness, etc. but instead for the Engine to prioritize the top items in each category.]]

Engine’s Primary Strengths

[[For each of the below sections, list three of the Engine’s internal strengths, capabilities, and advantages of the Engine. For each strength, include up to one paragraph description of the strength, evidence supporting the strength, and reference the relevant detailed information about this strengths in the full SWOT analysis.]]

Research, Development, and Translation for Ecosystem Development R&D and Translation

Workforce Development within the Region of Service

Broadening Participation

Engine’s Primary Weaknesses

[[For each of the below sections, list three of the Engine’s internal weaknesses. For each weakness, include up to one paragraph description and reference the relevant detailed information about this weakness in the full SWOT analysis.]]

Research, Development, and Translation for Ecosystem Development R&D and Translation

Workforce Development within the Region of Service

Broadening Participation

Engine’s Primary Challenges/Threats

[[For each of the below sections, list three of the Engine’s internal challenges/threats. For each challenge/threat, include up to one paragraph description and reference the relevant detailed information about this challenge/thread in the full SWOT analysis.]]

Research, Development, and Translation for Ecosystem Development R&D and Translation

Workforce Development within the Region of Service

Broadening Participation

Engine’s Primary Opportunities

[[For each of the below sections, list three of the Engine’s internal opportunities. For each opportunity, include up to one paragraph description and reference the relevant detailed information about this opportunity in the full SWOT analysis.]]

Research, Development, and Translation for Ecosystem Development R&D and Translation

Workforce Development within the Region of Service

Broadening Participation

III. Full SWOT Analysis

[[This section includes the detailed analyses using the rubrics with degrees of attainment, narratives, rubrics index, etc. Note that this is the content that Engines are developing using the remainder of the guidance in this document]]

IV. Conclusion

[[summarize key findings from the SWOT analysis and implications for strategic planning and decision-making.]]

Appendix

[[Engines may want to include an appendix with further details such as the following (if applicable):

Additional supporting data, charts, or diagrams relevant to the SWOT analysis

References, sources, or stakeholders consulted during the analysis process]]

Index of Engine SWOT Ratings

Topic

Criteria

Engine rating

Explanation of Rating

(e.g., narrative sections of the deliverable relevant to the self-rating)

Research, Development, and Translation

Use-inspired Research and Development

R&D Goal(s)

Research approach to achieve each goal

Data sharing plan

Infrastructure

Partnerships for R&D

Translation to Practice

Translation Goal(s)

Research to prototype translation

Prototype to low scale production

Production scale up

Data sharing plan

Infrastructure

Partnerships for translation to practice

Regional Assets to Support RD&T Ecosystem Development

Industrial resources

Academic resources

Entrepreneurial resources

Environmental resources

Staffing to achieve engine goals

Access to critical supply chains

Regional RD&T Ecosystem Development

Essential elements of a regional innovation ecosystem

Ecosystem partnerships

Staffing for the engine

Workforce to develop region of service

Regulatory assessment

Economic plan for a sustainable ecosystem

Inclusive engagement plan

Communication plan

Workforce Development

Labor Market

Inventory of industries and employers in the region of service [Labor Demand]

Inventory of talent in region of service [Labor Supply]

Skills and Training

Education Requirements

Workforce Development Goals

Training programs to reach workforce development goals of the Engine

Trainings related to increasing regional entrepreneurship

Trainings related to increasing the resiliency of the workforce (capable of moving across industries)

Partnerships

Institutes of higher learning (post-secondary school)

Private sector (for-profit companies, VCs, angel investors, etc.)

Trade organizations (economic development organizations, trade unions, chambers of commerce, etc.)

Public sector (local, State, and Federal Governments)

Nonprofit sector (community organizations, NGOs, etc.)

Broadening Participation

Outreach

Engagement with new and established communities and geographies

Communication with new and established communities and geographies

Engine staff

Individuals representative of the Engine’s goals for inclusive engagement for their region of service

Access path to join engine

Staff participation in strategic planning

Staff participation in decision making

Partnerships

Representative of the Engine’s inclusion goals for their region of service

Access path to join engine

Partnership participation in strategic planning

Partnership participation in decision making

Workforce

Representative of the Engine’s goals for inclusive engagement for their region of service

Opportunities to broaden participation in workforce recruitment

Access to professional development opportunity

Compensation parity

Other Criteria Relevant to Your Engine

Topic

Criteria

Reasoning

Literature Survey

Should additional information on rubrics and the three assessment areas be helpful, a sampling of the published literature is provided here.

Rubrics

Values in Evaluation - The Use of Rubrics. Dickinson, Pauline; Adams, Jeffery (2017) In Evaluation and Program Planning 65, pp. 113–116. DOI: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.07.005.

Conclusions. Rubrics are an adaptable tool that can be used for determining the merit and/or worth of an evaluation or product. The development and evaluation of rubric criteria helps facilitate a deeper understanding on what is important with regard to the rubric topic.

Abstract (abbreviated). Rubrics are used by evaluators who seek to move evaluations from being mere descriptions of an evaluand (i.e., the programme, project or policy to be evaluated) to determining the quality and success of the evaluand. However, a problem for evaluators interested in using rubrics is the literature relating to rubric development is scattered and mostly located in the education field with a particular focus on teaching and learning. In this short article we review and synthesise key points from the literature about rubrics to identify best practice. In addition we draw on our rubric teaching experience and our work with a range of stakeholders on a range of evaluation projects to develop evaluation criteria and rubrics. Our intention is to make this information readily available and to provide guidance to evaluators who wish to use rubrics to make value judgements as to the quality and success of evaluations.

How Program Evaluators Use and Learn to Use Rubrics to Make Evaluative Reasoning Explicit. Martens, Krystin S. R. (2018) In Evaluation and Program Planning 69, pp. 25–32. DOI: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan. 2018.03.006.

Conclusions. Rubrics are an evaluation tool that can be used to develop and negotiate a shared understanding of evaluation criteria among stakeholders. While there are few formal paths to learn about rubrics, rubric guidance, training, and resources can be used to disseminate information on how to use rubrics as an evaluation tool.

Abstract (abbreviated). A rubric is a tool that can support evaluators in a core function of their practice—the process of combining evidence with values to determine merit, worth, or significance—however, little guidance specific to evaluation exists. This study examined, through semi-structured interviews, how a rare group of nine rubric-using seasoned evaluators from across the globe use and learned to use rubrics in their program evaluation practice. Key findings revealed rubrics were a critical component to the practice of these evaluators to make determinations, but also as frameworks to sharpen an evaluation’s focus. Additionally, findings support the notion that there is a paucity of formal channels for learning about rubrics and indicate these early adopters are instead, honing their skills through informal channels such as trial and error and by tapping into a community of practice. Future directions for training and research should include expanding understanding, application, and acceptance of use.

Knowing the Learner: A New Approach to Educational Information. A New Approach to Educational Information. Zachos, Paul; Doane, William (2017) ShiresPress.

Conclusions. Rubrics are descriptions or explanations of what evidence is needed to assign a specified rating level. Educational evaluation, including the use of rubrics, is the act of using information to help stakeholders attain desired outcomes.

Abstract (abbreviated). Every student, teacher, parent, educational policymaker, and institution deserves a way to know whether students are learning what is being taught. Educational assessment and evaluation are needed to create and apply thisknowledge productively. Knowing the Learner is directed to everyone who wishes to understand what truly educational assessment and evaluation are (as well as what they are not). But to understand these, it is first necessary to understand the basic nature of educational activities. The book shows how to develop this understanding and how, for the field of education to move forward, teachers must become increasingly skilled in the practice of assessment and evaluation. Although Knowing the Learner delves into technical subjects, they are always presented in a way that requires no technical knowledge. For all of these reasons, Knowing the Learner can be of value to everyone who cares about improving education and particularly to those who are actively engaged in educational practice, policy, and decision-making. Readers may be surprised to discover that a new approach to assessment and evaluation is precisely what is needed, not only to make educational practice more effective but also to make it more humane.

2. SWOT Analysis

SWOT Analysis: A Theoretical Review. E. Gurel and M. Tat. J International Social Research: 10(51) (2017).

Conclusions. (1) SWOT Analysis is a valuable strategic management technique for planning and decision making to achieve long-term goals of an organization. (2) The qualitative examination of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats reveals an organization’s current situation and makes it possible to develop future action plans for the organization. (3) Strengths and weaknesses of the SWOT approach are reviewed.

Abstract. This study is a literature review on SWOT, qualitative and descriptive in nature. The study will examine SWOT Analysis in a historical, theoretical, time frame perspective, as an effective situation analysis technique which plays an important role in the fields of marketing, public relations, advertising and in any fields of requiring strategic planning. SWOT Analysis is an analysis method used to evaluate the ‘strengths’, ‘weaknesses’, ‘opportunities’ and ‘threats’ involved in an organization, a plan, a project, a person or a business activity. In this qualitative and descriptive study, firstly the position of SWOT Analysis in the strategic management process is explained, secondly the components of SWOT Analysis is examined. The study includes an international sports wear brand’s SWOT Analysis; historical origins of SWOT, advantages-disadvantages and the limitations of SWOT is also reviewed.

The Origins of SWOT Analysis. Richard W. Puyt, Finn Birger Lie, and Celeste P.M. Wilderom. Long Range Planning: 56 (2023).

Conclusions. (1) SWOT analysis has traceable origins (situated in Silicon Valley in the sixties of the past century) and (2) enables a well-founded process of co-creative strategy making by all managers within an organization. (3) SWOT’s current use is most often as a generic canvas or brainstorming scheme as part of strategic planning and strategic issue management systems.

Abstract. The origins of SWOT analysis have been enigmatic, until now. With archival research, interviews with experts and a review of the available literature, this paper reconstructs the original SOFT/SWOT approach, and draws potential implications. During a firm’s planning process, all managers are asked to write down 8 to 10 key planning issues faced by their units. Each manager grades, with evidence, these issues as either safeguarding the Satisfactory; opening Opportunities; fixing Faults; or thwarting Threats: hence SOFT (which is later merely relabeled to Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats, or SWOT). Subgroups of managers have several dialogues about these issues with the instruction to include the needs and expectations of all the firm’s stakeholders. Their developed resolutions or proposals become input for the executive planning committee to articulate corporate purpose(s) and strategies. SWOT’s originator, Robert Franklin Stewart, emphasized the crucial role that creativity plays in the planning process. The SOFT/ SWOT approach curbs mere top-down strategy making to the benefit of strategy alignment and implementation; Introducing digital means to parts of SWOT’s original participative, long-range planning process, as suggested herein, could boost the effectiveness of organizational strategizing, communication and learning. Archival research into the deployment of SOFT/SWOT in practice is needed.

What Are the Benefits and Pitfalls of Innovation Ecosystems? Klaudia Gabriella Horváth. Review of Economic Theory and Policy: 17(3) (2022)

Conclusions. (1) SWOT analysis applied to the case study on the Tungsram agricultural innovation ecosystem revealed that the major motive for collaboration is the possibility to create new value by sharing knowledge and resources to reduce the cost of innovation; (2) Trust-based relationships (often based on prior relationships) influence both the selection of partners and the cohesion of the cooperation; and (3) Identifying a credible ecosystem leader to define and manage common business goals and strategy is key for the long-term operation of an ecosystem.

Abstract. Whereas innovation ecosystems became widely popular lately, our knowledge is quite limited on the practical implementation of the relevant ecosystem models, specifically in Hungary. Hence, the aim of this paper is to analyse an innovation ecosystem as a case study related to one of the biggest Hungarian multinational company, called Tungsram. The research is considered to be a qualitative research, as the methodology incorporates document analysis and 26 semi-structured interviews with the ecosystem’s participants. The results show that the main benefits of participating in ecosystems are: new value creation by resource and knowledge sharing, networking and minimizing the cost of innovation. Meanwhile, the pitfalls of cooperation are closely related to the credibility of the ecosystem leader, to the formulation of the ecosystem’s strategy and to the quality of the absorptive capacity of the partners.

Accelerating Innovation Ecosystems: The Promise and Challenges of Regional Innovation Engines. Jorge Guzman, Fiona Murray, Scott Stern, and Heidi L. Williams. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 31541 (2023).

Conclusions. (1) Careful consideration of the interplay between meaningful stakeholder engagement, systematic assessment, and tailored strategic interventions are critical to address regional bottlenecks or target latent and distinctive regional opportunities; (2) Meaningful and cost-effective opportunities that leverage impact on engine’s ecosystems require adequate resources and effective management practices; and (3) Relational trust among regional stakeholders should advance the objectives of each participating stakeholder.

Abstract. Motivated by the establishment of major U.S. Federal programs seeking to harness the potential of regional innovation ecosystems, we assess the promise and challenges of place-based innovation policy interventions. Relative to traditional research grants, place-based innovation policy interventions are not directed toward a specific research project but rather aim to reshape interactions among researchers and other stakeholders within a given geographic location. The most recent such policy - the NSF “Engines” program - is designed to enhance the productivity and impact of the investments made within a given regional innovation ecosystem. The impact of such an intervention depends on whether, in its implementation, it induces change in the behavior of individuals and the ways in which knowledge is distributed and translated within that ecosystem. While this logic is straightforward, from it follows an important insight: innovation ecosystem interventions – Engines – are more likely to succeed when they account for the current state of a given regional ecosystem (latent capacities, current bottlenecks, and economic and institutional constraints) and when they involve extended commitments by multiple stakeholders within that ecosystem. We synthesize the logic, key dependencies, and opportunities for real-time assessment and course correction for these place-based innovation policy interventions.

Regional Innovation: Federal Programs and Issues for Consideration. Julie M. Lawhorn, Marcy E. Gallo, Adam G. Levin, Emily G. Blevins. Congressional Research Service report R47495 (2023)

Conclusions: In light of the findings in the report, CRS recommends Congress consider place-based development policies, such as (1) options to expand the Federal role in the development of Regional Innovation Systems (RIS) or make adjustments to the scope and scale of RIS assistance; (2) enhanced oversight of how RISs are implemented and coordinated between Federal agencies and across multiple levels of government; (3) options to integrate services provided by other Federal programs, such as capital access, infrastructure, and existing research institutions with RIS grantees; and (4) building the capacity of support organizations in under-resourced and disadvantaged communities and expanding access to capital for entrepreneurs. Better evaluate the outcomes of strategies used to address socioeconomic and regional disparities may also be of congressional interest.

Abstract (abbreviated): In recent years, Congress has increased support for economic development policies that incorporate a regional innovation systems (RIS) approach. RIS are composed of public and private sector partners, including educational and research institutions, investors, firms, economic development organizations, and entrepreneurs, among others. The RIS approach seeks to develop an ecosystem that fosters linkages between organizations so that a region may increase jobs, attract investment, and otherwise support economic development and related goals. The rationale for increased federal involvement in developing connected, innovative regional economies is often associated with concerns that the United States is ceding its global technology and economic competitiveness position, in particular relative to China. Proponents of RIS policies also view the approach as a means of addressing regional barriers to innovation and entrepreneurship and strengthening the capacity of regional stakeholders. Some policymakers and analysts consider federal support for RIS as a way to help revitalize and restructure places and regional economies that have been impacted by globalization and international trade. Others emphasize the spread of innovation and bolstering innovation capacity in specific regions as a means of creating well-paying jobs and combating socioeconomic and regional disparities.

3. Innovation Ecosystems

Innovation Ecosystems: A Conceptual Review and a New Definition. Granstrand, Ove; Holgersson, Marcus (2020) In Technovation 90-91, p. 102098. DOI: 10.1016/j.technovation.2019.102098.

Conclusion: This review shows that actors, artifacts, and activities are all elements in an innovation ecosystem, linked together through relations, including complement and substitute relations. This review also points at the importance of institutions and the evolving nature of innovation ecosystems.

Abstract (abbreviated): The concept of innovation ecosystems has become popular during the last 15 years, leading to a debate regarding its relevance and conceptual rigor, not the least in this journal. The purpose of this article is to review received definitions of innovation ecosystems and related concepts and to propose a synthesized definition of an innovation ecosystem. The conceptual analysis identifies an unbalanced focus on complementarities, collaboration, and actors in received definitions, and among other things proposes the additional inclusion of competition, substitutes, and artifacts in conceptualizations of innovation ecosystems, leading to the following definition: An innovation ecosystem is the evolving set of actors, activities, and artifacts, and the institutions and relations, including complementary and substitute relations, that are important for the innovative performance of an actor or a population of actors. This definition is compatible with related conceptualizations of innovation systems and natural ecosystems, and the validity of it is illustrated with three empirical examples of innovation ecosystems.

Accelerating Innovation Ecosystems: The Promise and Challenges of Regional Innovation Engines. Guzman, Jorge; Murray, Fiona; Stern, Scott; Williams, Heidi (2023) In National Bureau of Economic Research. DOI: 10.3386/w31541.

Described previously in SWOT Analysis section.

Valuing Value in Innovation Ecosystems: How Cross-Sector Actors Overcome Tensions in Collaborative Sustainable Business Model Development. Oskam, Inge; Bossink, Bart; Man, Ard-Pieter de (2021) In Business & Society 60 (5), pp. 1059–1091. DOI: 10.1177/0007650320907145.

Conclusion: This paper highlights how each actor in any innovation ecosystem has individual interests that are a condition for the continuing existence and further development of the innovation ecosystem. Furthermore, that paper finds that cross-sector actors engage in a process of valuing value, which is a search and discovery of environmental, social, and economic value creation and capture.

Abstract (abbreviated): This article aims to uncover the processes of developing sustainable business models in innovation ecosystems. Innovation ecosystems with sustainability goals often consist of cross-sector partners and need to manage three tensions: the tension of value creation versus value capture, the tension of mutual value versus individual value, and the tension of gaining value versus losing value. The fact that these tensions affect all actors differently makes the process of developing a sustainable business model challenging. Based on a study of four sustainably innovative cross-sector collaborations, we propose that innovation ecosystems that develop a sustainable business model engage in a process of valuing value in which they search for a result that satisfies all actors. We find two different patterns of valuing value: collective orchestration and continuous search. We describe these patterns and the conditions that give rise to them. The identification of the two patterns opens up a research agenda that can shed further light on the conditions that need to be in place in order for an innovation ecosystem to develop effective sustainable business models. For practice, our findings show how cross-sector actors in innovation ecosystems may collaborate when developing a business model around emerging sustainability-oriented innovations.

A Conceptual Framework for Developing of Regional Innovation Ecosystems. Pidorycheva, Iryna; Shevtsova, Hanna; Antonyuk, Valentina; Shvets, Nataliia; Pchelynska, Hanna (2020) In EJSD 9 (3), p. 626. DOI: 10.14207/ejsd.2020.v9n3p626.

Conclusions: The innovation ecosystem at the regional level will be effective only if the organizational core is created on the basis of public-private partnership, which unites interest in innovations and capable regional actors. The innovation ecosystem must be subject to continuous change under the influence of new motivations of participants and new external conditions of macroeconomic, technological, and institutional nature—not only regional or national content, but also taking into account global perspective of fast and large-scale changes.

Abstract (abbreviated): The article highlights a conceptual framework for developing of regional innovation ecosystems at the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) 1 level. The conceptual model of the regional innovation ecosystem of Ukraine has been suggested taking into account features of its current territorial division. The key dimensions of the model include the goal of the ecosystem, its actors, the environment and the system of internal and external interrelationship. Considering the specifics of regional governance in Ukraine, it was substantiated that it is advisable to use the existing network of regional research centers as institutional tools to support regional innovation ecosystems at NUTS 1 level. It is suggested to create special coordination centers, in particular, regional innovation councils at NUTS 2 level.

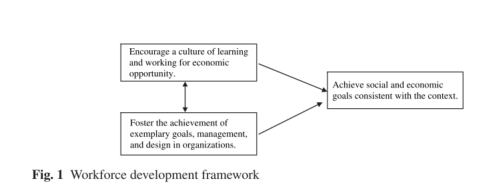

3. Workforce Development

Four Promising Practices from a Workforce Development Partnership. Myran, Steve; Sylvester, Paul; Williams, Mitchell R.; Myran, Gunder (2023): In Community College Journal of Research and Practice 47 (1), pp. 38–52. DOI: 10.1080/10668926.2021.1925177.

Conclusion: The program is framed along the following four components: (1) the role of employers, (2) the role of governmental agencies and nonprofit organizations, (3) a collaborative network of employers and other community partners, and (4) a spirit of creativity and innovation.

Abstract: This article reports on four synthesis findings from the Credentials to Careers (C2C) initiative – a consortium of seven community colleges working to create and implement innovative programs to train or retrain unemployed and displaced workers for STEM, advanced manufacturing and health-care related careers. These are (1) collaborating with community partners to meet the needs of employers and trainees, (2) tapping into local knowledge and investing in curriculum, (3) “minding the gaps” between each stage of their college career, and (4) using career navigators to support student success. In discussing the implications of this work, we ask what synthesis observations might offer comprehensive, specific and actionable knowledge for the changing workforce development climate of community colleges? As such, the implications suggest lessons and actionable knowledge that community college leaders and faculty members might draw from in their own efforts to meet community, student and workforce development needs.

The Emergence of ‘Workforce Development’: Definition, Conceptual Boundaries and Implications. Jacobs, Ronald L.; Hawley, Joshua D. (2009): In Rupert Maclean (Ed.): International handbook of education for the changing world of work: bridging academic and vocational education: Springer, pp. 2537–2552. Available online at https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4020-5281-1_167.

Conclusion: The definition of workforce development traditionally referred to government-sponsored or funded activities for disadvantaged people, focusing on job training and remedial education. This definition expanded in the 1990s and the authors propose it encompasses policies, programs, and activities related to working and learning challenges. Workforce development programs have extremely broad goals, and thus many activities can be classified as workforce development.

There is an emphasis on

employing organizations, educating organizations, and broader

socioeconomic goals.

Abstract: This chapter begins a much-needed discourse about workforce development, a term used with increasing frequency among educational practitioners, policy-makers and scholars alike. In spite of the increasing use of the term, there has been limited discussion about its meaning and implications for established fields of study (Giloth, 2000; Grubb, 1999; Harrison & Weiss, 1998). This discourse is critical for both theoretical and practical reasons, particularly given the economic and social benefits that are expected from workforce development programmes (Grubb & Lazerson, 2004).

Specifically, the purposes of this chapter are: (a) to discuss the emergence of workforce development based on five historical streams; (b) to propose a definition and conceptual boundaries for workforce development; and (c) to explore the implications of workforce development on policy-makers, researchers and practitioners.

Evaluation of the Workforce Development Agreements. Carrière; April (2022): In Employment and Social Development Canada. Available online at https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/canada/employment-social-development/corporate/reports/evaluations/workplace-development-agreements/wda-en.pdf, checked on 1/18/2024.

Conclusion: Canada’s Workforce Development Agreement (WDA) program provides a framework for workforce development agreements. This report provides a framework for how to evaluate WDAs. The evaluation matrix in Appendix A includes exemplar criteria for evaluating a WDA. Appendix B provides a literature review on effective programs and services for workforce development of specific underserved populations.

Executive Summary (abbreviated): The Workforce Development Agreements (WDAs) are a key mechanism to provide training and employment supports to Canadians. Through bilateral agreements with provinces and territories (P/Ts), financial support is provided for the design and delivery of programs and services to help participants obtain the training, skills, and work experience they need to improve their labour market outcomes. The agreements also allow for the provision of support to employers seeking to train current and future employees.

The agreements’ broad participant and program eligibility criteria aim to give P/Ts the flexibility they need to design and deliver programs and services that meet their jurisdictions’ labour market needs. The agreements aim to support those who are further away from the labour market or are underemployed, and include targeted funding for persons with disabilities as well as funding that can be used to serve other underrepresented groups, such as Indigenous peoples, youth, older workers, women, immigrants and newcomers to Canada.

Evaluation objectives

Describe the types of programs and services funded by the agreements and the delivery approaches.

Identify the labour market needs and priorities that the agreements are being used to address.

Examine the labour market outcomes observed for participants.

Identify strengths and challenges associated with the design and implementation of the agreements.

Promising Practices for Strengthening the Regional STEM Workforce Development Ecosystem. Board on Higher Education and Workforce Committee on Improving Higher Education's Responsiveness to Regional STEM Workforce Needs: Identifying Analytical Tools and Regional Best Practices; Board on Higher Education and Workforce; Policy and Global Affairs; National Academies of Sciences; Engineering; and Medicine (2016): Washington D.C.: The National Academies Press. Available online at https://thescienceexperience.org/Books/Practices_for_Strengthening_Regional_STEM_Workforce_Development_Ecosystem.pdf, checked on 2/2/2024.

Conclusion: The main stakeholders in a STEM workforce development ecosystem: higher education, local employers/industry, intermediary bodies (economic development organizations, chambers of commerce, etc.), policy/government, and nonprofit/philanthropic. There is a mismatch of university graduates and workforce needs especially in regard to narrow STEM skills and broad STEM skills. Proactive engagement of business and university leaders is needed for the STEM workforce development ecosystem.

Executive Summary (abbreviated):

To explore common and proposed practices in establishing partnerships among academia, governments, and industry, a committee organized under the auspices of the Board on Higher Education and Workforce of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine undertook an 18-month study of the extent to which universities and employers in five metropolitan communities (Phoenix, Arizona; Cleveland, Ohio; Montgomery, Alabama; Los Angeles, California; and Fargo, North Dakota) collaborate successfully to align curricula, labs, and other undergraduate educational experiences with current and prospective regional STEM workforce needs.

The key topic for this study was as follows: How to create the kind of university-industry collaboration that promotes higher-quality college and university course offerings, lab activities, applied learning experiences, work-based learning programs, and other activities that enable students to acquire knowledge, skills, and attributes they need to be successful in the STEM workforce.

Workforce Program Design and Evaluation. Allison Moe, Cory Chovanec, and Robin Tuttle: Better Buildings Workforce Accelerator Workshop. National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Available online at https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy23osti/86302.pdf, checked on 3/5/2024.

Conclusion: Workshop to help design and evaluate a workforce development program. The steps to developing a workforce development program are:

Regional Market Analysis: challenges, demand and opportunities, job market, potential partners;

Program Development: high-level goals/objectives, general approach, implementation details;

Partner Engagement: Partner responsibilities, building trust, formalizing the partnership;

Program Implementation: developing materials, recruitment, trainee engagement, tracking; and

Program Evaluation: tracking, reviewing goals and metrics, making changes to improve the program.

4. Broadening Participation

Summary and Analysis of Request for Information to Make Access to the Innovation Ecosystem More Inclusive and Equitable. Olszewski, Tom; White, Taylor (2022): Available online at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/09-2022-Equitable_Innovation_Ecosystem_RFI_Analysis_Public_Clean.pdf, checked on 1/24/2024.

Conclusion: The report identified four overarching types of barriers to inclusive innovation ecosystems: (1) barriers to entry, (2) educational and knowledge barriers, (3) structural and cultural barriers, and (4) Federal programmatic barriers. The report also identified three common traits associated with successful inclusive innovation programs: (1) partnering closely with the communities the programs aim to help, (2) evaluating the situation of the community being served and the impact of the programs, and (3) providing sustainable, reliable support for an enterprise from development to commercialization.

Executive Summary (abbreviated): OSTP published a Request for Information to Make Access to the Innovation Ecosystem More Inclusive and Equitable (Inclusive Innovation RFI) in the Federal Register, soliciting comments between the dates of June 3 and July 5, 2022 with the aim of gathering input from the public to identify and better understand:

Barriers that prevent innovators from underrepresented groups or underserved communities from participating in the U.S. innovation ecosystem;

Examples of government programs or other initiatives that have seen success in supporting innovators from underrepresented backgrounds; and

Recommendations to meet the specific needs of innovators from underrepresented backgrounds and underserved communities to increase their participation in the innovation ecosystem.

Cultural Diversity and Regional Innovation: Evidence from China. Guo, Mengmeng; Yu, Yixiang; Ye, Jingjing (2024) In Growth and Change 55 (1), Article e12704, e12704. DOI: 10.1111/grow.12704.

Conclusion: Cultural diversity does contribute to regional innovation. Cultural diversity has a significant positive impact on innovation, suggesting that in China the knowledge spillover brought by the diversity in culture exceeds the cost of conflicts and mistrust.

Abstract (Abbreviated): The cultural diversity brought by migrants has attracted widespread interest in recent years. This paper investigates the relationship between migrant cultural diversity and regional innovation by constructing panel data of provincial migrant cultural diversity and combining them with invention applications data from China's State Intellectual Property Office. The empirical results show that the migrant cultural diversity, measured by migrant's hukou and dialect respectively, has a positive impact on regional innovation. The effect still holds after a series of robustness tests and addressing endogeneity issues. Furthermore, the further analysis implies that the effects of the migrant cultural diversity in workers aged from 30 to 50, engaged in an innovative occupation, working in high market-competitiveness or inclusive provinces are more pronounced. Our study supplements the current research on the relationship between migrant cultural diversity and regional innovation.

DEIA Is Essential to Advance the Goals of Translational Science: Perspectives from NCATS. Hussain, Shadab F.; Vogel, Amanda L.; Faupel-Badger, Jessica M.; Ho, Linda; Akacem, Lameese D.; Balakrishnan, Krishna et al. (2023). In Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 7 (1), e33. DOI: 10.1017/cts.2022.482.

Conclusion: Encouraging robust representation of diverse populations in biomedical research can enable equitable access to scientific advances and contribute to a holistic understanding of disease and health. Data can also be leveraged to advance DEIA in translational research. Furthermore, using a DEIA lens can allow researchers to recognize different barriers to accessing understandable, accurate, and relevant information on translational findings.

Abstract (abbreviated): The National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) seeks to improve upon the translational process to advance research and treatment across all diseases and conditions and bring these interventions to all who need them. Addressing the racial/ethnic health disparities and health inequities that persist in screening, diagnosis, treatment, and health outcomes (e.g., morbidity, mortality) is central to NCATS’ mission to deliver more interventions to all people more quickly. Working toward this goal will require enhancing diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) in the translational workforce and in research conducted across the translational continuum, to support health equity. This paper discusses how aspects of DEIA are integral to the mission of translational science (TS). It describes recent NIH and NCATS efforts to advance DEIA in the TS workforce and in the research we support. Additionally, NCATS is developing approaches to apply a lens of DEIA in its activities and research – with relevance to the activities of the TS community – and will elucidate these approaches through related examples of NCATS-led, partnered, and supported activities, working toward the Center’s goal of bringing more treatments to all people more quickly.

What Does "Diversity" Mean for Public Engagement in Science? A New Metric for Innovation Ecosystem Diversity. Özdemir, Vural; Springer, Simon (2018) In Omics: a journal of integrative biology 22 (3), pp. 184–189. DOI: 10.1089/omi.2018.0002.

Conclusion: The authors of this paper developed a new diversity metric, Frame Diversity Index, which can usefully measure (and prevent) errors in the framing of a research question in an innovation ecosystem. The use of this metric can help broaden the concepts and practices of diversity and inclusion in science, technology, innovation and society.

Abstract (abbreviated): Diversity is increasingly at stake in early 21st century. Diversity is often conceptualized across ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, sexual preference, and professional credentials, among other categories of difference. These are important and relevant considerations and yet, they are incomplete. Diversity also rests in the way we frame questions long before answers are sought. Such diversity in the framing (epistemology) of scientific and societal questions is important for they influence the types of data, results, and impacts produced by research. Errors in the framing of a research question, whether in technical science or social science, are known as type III errors, as opposed to the better known type I (false positives) and type II errors (false negatives). Kimball defined “error of the third kind” as giving the right answer to the wrong problem. Raiffa described the type III error as correctly solving the wrong problem. Type III errors are upstream or design flaws, often driven by unchecked human values and power, and can adversely impact an entire innovation ecosystem, waste money, time, careers, and precious resources by focusing on the wrong or incorrectly framed question and hypothesis. Decades may pass while technology experts, scientists, social scientists, funding agencies and management consultants continue to tackle questions that suffer from type III errors. We propose a new diversity metric, the Frame Diversity Index (FDI), based on the hitherto neglected diversities in knowledge framing. The FDI would be positively correlated with epistemological diversity and technological democracy, and inversely correlated with prevalence of type III errors in innovation ecosystems, consortia, and knowledge networks. We suggest that the FDI can usefully measure (and prevent) type III error risks in innovation ecosystems, and help broaden the concepts and practices of diversity and inclusion in science, technology, innovation and society.

1Information from this data collection system will be retained by the National Science Foundation (NSF), a Federal agency, and will be an integral part of its Privacy Act System or Records In accordance with the Privacy Act of 1974. All individually identifiable information supplied by individuals or institutions to a Federal agency may be used only for the purposes outlined in the system of records notice and may not be disclosed or used in identifiable form for any other purpose, unless otherwise compelled by law. These are confidential files accessible only to appropriate NSF officials, their staffs, and their contractors responsible for monitoring, assessing, and evaluating NSF programs. Only data in highly aggregated form or data explicitly requested "for general use” will be made available to anyone outside of NSF for research purposes. Data submitted will be used in accordance with criteria established by NSF for monitoring research and education grants, and in response to Public Law 99-383 and 42 U.S.C. 1885c.

Pursuant to 5 CFR 1320.5 (b), an agency may not conduct or sponsor, and a person is not required to respond to an information collection unless it displays a valid OMB control umber. The OMB control number for this collection is 3145-XXXX. Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 200 hours per response the first year, including the time for reviewing instructions. Send comments regarding this burden estimate and any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to:

Suzanne

H. Plimpton

Reports

Clearance Officer

Policy

Office, Division of Institution and Award Support

Office

of Budget, Finance, and Award Management

National

Science Foundation Alexandria, VA 22314

Email: [email protected]

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Saybolt, Erin |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2024-11-16 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy