DFC Evaluation Plan

FINAL Attachment 3_Evaluation Plan .docx

Drug Free Communities Support Program National Evaluation

DFC Evaluation Plan

OMB: 3201-0012

Attachment 3:

Drug-Free Communities Support Program National Evaluation Plan

Drug-Free Communities Support Program

National Evaluation Plan

Final

May 2015

R eport

prepared for the:

eport

prepared for the:

White House Office of National Drug Control Policy

Drug-Free Communities Support Program

by:

ICF International

9300 Lee Highway

Fairfax, VA 22031

under contract number BPD-NDC-09-C1-0003

Table of Contents

1. Introduction to the Drug-Free Communities (DFC) Program 2

DFC National Evaluation Logic Model 2

The SAMHSA Strategic Prevention Framework 2

Objective 1: Strengthen Measurement of Process Data 2

Objective 2: Refine Process Data with New Metrics on Coalition Operations 2

Objective 3: Report Outcomes and Strengthen Attribution between Processes and Outcomes 2

Objective 4: Deconstruct Strategies to Identify Best Practices 2

3. Data Collection and Management 2

Coalition Online Management and Evaluation Tool 2

Coalition Classification Tool (CCT) 2

Steps to Improve Data Quality 2

Facilitating Data Collection 2

Technical Assistance to Grantees 2

Analyzing Grantee Feedback from Technical Assistance Activities 2

Drug-Free Communities Support Program

National Evaluation Plan

The analysis plan outlined in this document is designed to provide ONDCP with strong evidence and useful results tailored to the needs of stakeholder groups (i.e., SAMHSA, DFC grantees, community partners, etc.). Our approach will ensure that we continue to provide results that can be used by coalitions to enhance their operations and capacity, and ultimately, improve their performance in reducing community-level youth substance use rates. If appropriate, we will also continue to provide ONDCP’s Government Performance Results Act (GPRA) and any additional monitoring tools that may be required.

The scope of the evaluation described in this attachment is specific to Drug-Free Communities (DFC). This analysis plan identifies existing methods that have proven useful and will be continued, and adjustments in methods to improve analyses and make adjustments based on preliminary findings of ongoing evaluation analyses on the existing data set.. The maintenance of this plan will ensure that all major decisions concerning the method and analysis are clearly documented. . It will also ensure that new staff on the contract will have a steep learning curve and become efficiently engaged in productive work.

1. Introduction to the Drug-Free Communities (DFC) Program

The Federal government launched a major effort to prevent youth drug use by appropriating funds in 1997 for the Drug-Free Communities Act. That financial commitment has continued for more than a decade, and in Fiscal Year 2013, 618 community coalitions across 50 States, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Palau, and Puerto Rico received grants to improve their substance abuse prevention strategies. With bipartisan support from Congress, the DFC Support Program provides community coalitions with up to $125,000 annually, with a maximum of $625,000 over five years with a maximum of two five year grants. The Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), in partnership with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), funded 87 new Year 1 grants in August 2013, with a goal to extend these long-term coalition efforts. ONDCP funded 99 new Year 1 grants in fiscal year 2014.

Goals of DFC are to: (1) increase collaboration, evidence-based decisions, and comprehensive community strategies participating communities; (2) to strengthen community, family, and individual protective assets; and reduce risks related to underage substance use; ; and (3) reduce substance use among youth.

DFC is the key federally funded community prevention program and can be a model for other public health issues outside of substance abuse prevention. The proposed plan outlined in this document will take research evidence to the next level. A key to the DFC national evaluation is to understand not just the outcomes associated with the program but to also understand the natural variation that occurs within coalitions. Ultimately, the goal is to build a connection between the two in order to answer not not only which coalition strategies are working, but also why they are working, how they are working, and in what situations they are working.

Evaluation Background

For two decades, communities have expanded efforts to address social problems through collective action. Based on the belief that new financial support enables a locality to assemble stakeholders; assess needs; enhance and strengthen the community’s prevention service infrastructure; improve immediate outcomes; and reduce levels of substance use, DFC-funded coalitions have been able to implement strategies that have been supported by prior research.1 Research also shows that effective coalitions are holistic and comprehensive; flexible and responsive; build a sense of community; and provide a vehicle for community empowerment.2 Yet, there remain many challenges to evaluating them. the community context within which interventions are implemented is dynamic. As a result, conventional evaluation models involving comparison sites are not appropriate to implement.3

Three major features of our evaluation approach allow us to expand upon previous analysis to include a far greater range of hypotheses concerning the coalition characteristics that contribute to stronger outputs, stronger coalition outcomes, and ultimately stronger community outcomes.

First, our approach will systematically deconstruct more encompassing measures (e.g., maturation stages) into specific factors that are more clearly related to strategies and functions that coalitions must perform, and that define their capacity. This will provide measures of multiple coalition characteristics that may differentiate real world coalitions, may be important to producing effective coalitions, and may operate differently across different settings and in different coalition systems.

Second, we use a natural variation approach, in which we examine and test for differences in coalition organization, function, procedure, management strategy, and intent which may provide concrete lessons on how to construct effective coalitions in diverse settings. This

Third, our design and analysis uses a multi-method approach in which different “sub-studies” or ad-hoc studies within the large DFC National Evaluation project umbrella can provide unique opportunities to contribute to project lessons. For example, the case study component of our design and analysis through the use of site visits will provide strong opportunity to implement many of the analyses identified in the discussion of the logic model that follows in the next section of this paper. The rich data attained during site visits to coalitions, combined with our process and outcome data, will serve this purpose. Over time, as the site visit data set grows in size, these rich measures will produce a valuable analytic database. In addition to site visits, we will continue to explore qualitative responses provided by DFC coalitions in their progress reports to better understand activities they are engaging in, not only related to core measure substances but more broadly to address substances that are of local concern.

By better understanding the DFC Program and its mechanisms for contributing to positive change, the National Evaluation can deliver an effective, efficient, and sensitive set of analyses that will meet the needs of the program at the highest level while also advancing prevention science.

DFC National Evaluation Logic Model

At its first meeting in April 2010, the DFC National Evaluation Technical Advisory Group (TAG) identified the need for revision of the “legacy” logic model prepared by the previous evaluator. A Logic Model Workgroup was established and charged with producing a revised model that provides a concise depiction of the coalition characteristics and outcomes that will be measured and tested in the national evaluation. The TAG directed the Workgroup to develop a model that communicates well with grantees, and provides a context for explicating evaluation procedures and purposes.

The Workgroup held its first meeting by telephone conference in July 2010. In the following two months, the committee (1) developed a draft model, (2) reviewed literature and other documents, (3) mapped model elements against proposed national evaluation data, (4) obtained feedback from grantees through focus groups at the CADCA Mid-year Training Institute in Phoenix, (5) developed and revised several iterations of the model, and (6) produced the recommended logic model shown in Exhibit 1. The National Evaluation logic model has six major features, described below, that define the broad coalition intent, capacity, and rationale that will be described and analyzed in the National Evaluation. At the most basic level, the logic model suggests that DFC coalitions operate in ways that guide the strategies and activities they engage in and that ultimately youth behavior is changed through engagement of the community in the coalition activities. All of this occurs in a community context that suggests local solutions for local problems.

Theory of Change. The DFC National Evaluation Logic Model begins with a broad theory of change that focuses the evaluation on clarifying those capacities that define well functioning coalitions. This theory of change is intended to provide a shared vision of the overarching questions the National Evaluation will address, and the kinds of lessons it will produce.

Community Context & History. The ability to understand and build on particular community needs and capacities is fundamental to the effectiveness of community coalitions. The National Evaluation will assess the influence of context in identifying problems and objectives, building capacity, selecting and implementing interventions, and achieving success.

Coalition Structure & Processes. Existing research and practice highlights the importance of coalition structures and processes for building and maintaining organizational capacity. The National Evaluation will describe and test variation in DFC coalition structures and processes, and how these influence capacity to achieve outcomes. The logic model specifies three categories of structure and process for inclusion in evaluation description and analysis:

Member Capacity. Coalition members include both organizations and individuals. Selecting and supporting individual and organizational competencies are central issues in building capacity. The National Evaluation will identify how coalitions support and maintain specific competencies, and which competencies contribute most to capacity in the experience of DFC coalitions.

Coalition Structure. Coalitions differ in organizational structures such as degree of emphasis on sectoral agency or grassroots membership, leadership and committee structures, and formalization. The logic model guides identification of major structural differences or typologies in DFC coalitions, and assessment of their differential contributions to capacity and effectiveness.

Coalition Processes. Existing research and practice has placed significant attention on the importance of procedures for developing coalition capacity (e.g., implementation of SAMHSA’s Strategic Prevention Framework). Identifying how coalitions differ in these processes, and how that affects capacity, effectiveness, and sustainability is important to understanding how to strengthen coalition functioning.

Coalition Strategies & Activities. One of the strengths of coalitions is that they can focus on mobilizing multiple community sectors for comprehensive strategies aimed at community-wide change. The logic model identifies the role of the National Evaluation in describing and assessing different types and mixes of strategies and activities across coalitions. Preliminary analyses conducted following revisions to the collection of strategy and activity data in 2013 suggest that DFC grantees that the implementation of strategies and activities is often organized into one of three strategy orientations. Going forward, the DFC National Evaluation will continue to explore strategy orientations in order as it related to both how DFC coalitions operate and how strategies and outcomes may be related to one another.

As depicted in the model, this evaluation task will include at least the following categories of strategies and activities.

Information & Support. Coalition efforts to educate the community, build awareness, and strengthen support are a foundation for action. Identifying how coalitions do this, and the degree to which different approaches are successful, is an important evaluation activity.

Enhancing Skills. This includes activities such as workshops and other programs (mentoring programs, conflict management training, programs to improve communication and decision making) designed to develop skills and competencies among youth, parents, teachers, and/or families to prevent substance use.

Policies / Environmental Change. Environmental change strategies include policies designed to reduce access; increase enforcement of laws; change physical design to reduce risk or enhance protection; mobilize neighborhoods and parents to change social norms and practices concerning substance use; and support policies that promote opportunities and access for positive youth activity and support. Understanding the different emphases coalitions adopt, and the ways in which they impact community conditions and outcomes, are important to understanding coalition success.

Programs & Services. Coalitions also may promote and support programs and services that help community members strengthen families through improved parenting; that provide increased opportunity and access to protective experiences for youth; and that strengthen community capacity to meet the needs of youth at high risk for substance use and related consequences.

Community & Population-Level Outcomes. The ultimate goals of DFC coalitions are to reduce population-level rates of substance use in the community, particularly among youth; to reduce related consequences; and to improve community health and well-being. The National Evaluation logic model represents the intended outcomes of coalitions in two major clusters: (1) core measures data, which are gathered by local coalitions, and (2) archival data (e.g., youth risk behavioral study (YRBS) data, Monitoring the Future (MTF) data, uniform crime report (UCR) date), which will be synthesized by the National Evaluation team. The primary focus of the evaluation is centered on the core measures. Sub-studies and ad-hoc studies are proposed as appropriate opportunities to include available, relevant archival data. These data will be utilized to assess the impact of DFC activities on the community environment and on substance use and related behaviors.

Community Environment. Coalitions are encouraged to engage in strategies to change local community conditions that needs assessment and community knowledge identify as root causes, or contributors, of community substance use and related consequences. These community conditions may include population awareness, norms and attitudes; system capacity and policies; or the presence of sustainable opportunities and accomplishments that protect against substance use and other negative behaviors.

Behavioral Consequences. Coalition strategies are also intended to change population-level indicators of behavior, and substance use prevalence in particular. Coalition strategies are expected to produce improvements in educational involvement and attainment; improvements in health and well-being; improvements in social consequences related to substance use; and reductions in criminal activity associated with substance use (e.g., reduced drunk or drugged driving).

Line Logic. The National Evaluation Logic Model includes arrows representing the anticipated sequence of influence in the model. If changes occur in an indicator before the arrow, the model represents that this will influence change in the model component after the arrow. For the National Evaluation Logic Model, the arrows represent expected relations to be tested and understood: How strong is the influence? Under what conditions does it occur?

Case Study Findings Examples During site visits conducted from

2011-2014, several key features of successful coalitions were

identified, including the following: DFC grantees built a strong

foundation in the community as the go-to resource for information

about substance use and prevention DFC grantees were effective

at collecting and communicating local data. Examinations of data

were used to guide decision making about strategies and activities

to engage in Most, though not all, were

effectively engaging youth, most typically through a youth

coalition. Youth coalition leaders and members described feeling

engaged with substance abuse prevention through the opportunities

to act as leaders These findings have been

communicated to DFC grantees through webinars and at CADCA

conferences, engaging participants in dialogue about how and to

what extent these activities might be used locally in order to

become more effective.

In summary, the National Evaluation Logic Model is intended to summarize the coalition characteristics that will be measured and assessed by the National Evaluation team. The model depicts characteristics of coalitions that will be described as they present themselves, not prescriptive recommendations for assessing coalition performance. This model is intended to guide an evaluation process through which we can learn from the grounded experience of the DFC coalitions who know their communities best. The model uses past research and coalition experience to provide focus on those coalition characteristics that we believe are important to well functioning and successful coalitions. The data we gather will tell us how community coalitions implement these characteristics, what works for them, and under what conditions. In this sense the model is an evolving tool -- building on the past to improve learning from the present and to create evidence-based lessons for coalitions in the future.

Exhibit 1. DFC National Evaluation Logic Model

T heory

of Change:

Well functioning community coalitions can stage and sustain a

comprehensive set of interventions that mitigate the local conditions

that make substance use more likely.

heory

of Change:

Well functioning community coalitions can stage and sustain a

comprehensive set of interventions that mitigate the local conditions

that make substance use more likely.

2. Evaluation Framework

Our approach to this evaluation is to move ONDCP to a progressively stronger evidence base, while identifying best practices and providing more practical results for the field. The DFC National Evaluation began collecting new data and to collect data in more streamlined ways in August 2012. In the next five years, a key aspect of the national evaluation will be to maintain and further improve the quality and utility of this data, including validity and reliability checks and measurement improvements. This data will be used to expand analyses focusing on how coalition processes and strategies are connected to outcomes.

Understanding Outcomes of the DFC Program

Since 2012, the DFC National Evaluation has been gathering data on four core outcome measures (i.e., past 30-day substance use, perception of risk associated with use, perception of parent disapproval, perception of peer disapproval) asked about each of four core measure substances (i.e., alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, nonmedical use of prescription drugs). These measures are gathered through two samples: high school and middle school. At the most basic level, the key objective of the DFC National Evaluation is to measure and understand changes in these core outcomes measures. The key questions are:

Are the core measures changing in the desired direction in DFC communities and are they doing so consistently across all core substances?

Changes in core outcomes will be examined and reported annually. Understanding change in core measures in coalition communities is a precursor to understanding what is associated with those changes (e.g., strategies and activities, coalition processes)

Moving Evidence to Practice

When a consumer of research–such as a legislator, school board member, community health professional, or prospective coalition member–reviews the effectiveness of various strategies, he or she is likely focused on a single question:

Will this strategy work in my community?

While the assessment of whether a study’s results are applicable in a local context is a complex judgment that must ultimately be made by practitioners on the “front lines,” there is a great need to present evidence-based information in a manner that is useful for making these types of judgments. Our approach to the National DFC Evaluation emphasizes this utilization-focused perspective by producing findings that a) optimize external validity (generalizability), and b) develops and analyzes measures of concepts that represent the ways that practitioners actually make and implement decisions. These are primary objectives of our evaluation methods. We do not emphasize high level abstractions or theory to achieve this goal. Our natural variation approach produces contextual sensitivity, reality-based measures, and sufficient detail in findings to help decision makers at the Federal, State, and local levels decide on informed courses of action to pursue local community prevention objectives.

Evaluation

Our goal in the next phase of the evaluation will be to implement a set of innovative, scientifically-based methods that will be both accepted by the research community and intuitive to non-researchers. Undoubtedly, this evaluation will need to address the concerns and needs of a number of stakeholders. Stakeholders in ONDCP, SAMHSA, and in the research and prevention communities will be focused on questions of internal validity and results of the DFC program, while stakeholders in the field will be focused on the identification of best practices and their replication. Our study design and analysis plan focuses on research questions that are relevant to these key stakeholder groups, and, in collaboration with ONDCP, we will identify priority questions on which to focus. One major emphases over the next five years will be to closely examine the new data that is being collected from DFC grantees and to analyze it to answer relevant questions in ways that provide useful guidance based on the most rigorous and precise analysis possible within this initiative. Exhibit 2 provides a summary of selected examples of research questions relevant to the evaluation (column 1), the potential products through which findings and lessons can be communicated in a useful way (column 2), and a preliminary identification of analysis methods that our design will support, and that will provide answers to the questions (column 3).

Exhibit 2. Key Evaluation Questions, Products, and Analytic Methods |

||

Key Research Questions |

Products |

Methods |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exhibit 3 is a simple guide to the planning and implementation that will characterize our implementation of the evaluation design. The plan is intended to be flexible and can be focused on specific issues based on what is of specific interest to ONDCP in any given year or over time. For example, we have proposed the addition of asking DFC coalitions to self-identify as having a focus on working with LGBT youth as well as on other special populations (e.g., minority youth). We have also proposed the introduction of a TWG of experts on working with special populations). Going forward we will focus additional analyses to better understand DFC coalitions who work with these special populations, many of whom may be disproportionately likely to be affected by substance use. The goal of these types of analyses is not to have all DFC grantees focus on these issues, but to better understand the issue so that if they do shift focus they will be better prepared and equipped to work effectively.

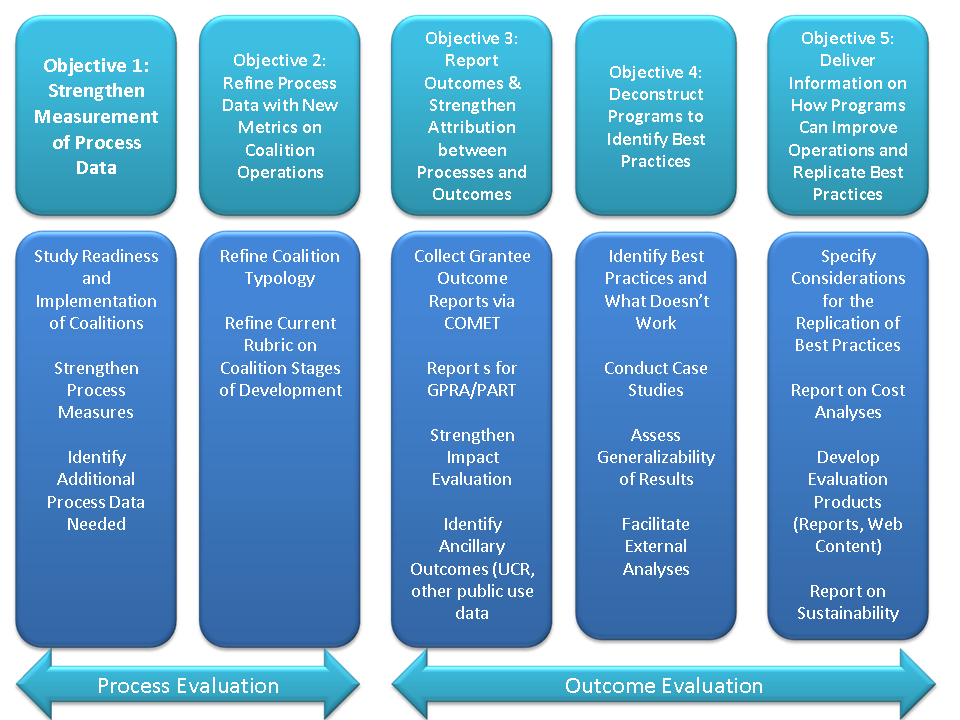

Exhibit 3 contains a simplified version of our evaluation plan. This exhibit demonstrates that there are five objectives (or stages) in the execution of this evaluation. They are:

Objective 1: Strengthen Process Measures. Ongoing examination of the level of detail with which coalition strategies are described and differentiated, following modifications that occurred in 2012. Thus, details will support analyses of the degree to which different coalition structures, procedures, strategies, and implementation characteristics contribute to the achievement of the grantee and community outcomes identified in our evaluation logic model (Exhibit 1). Strengthening process measures is simply the necessary foundation for answering many of the stakeholder research questions previewed in Exhibit 3.

Objective 2: New Metrics on Coalition Operations. The detailed measurement of process is necessary to accurately measure coalition structure, procedure, and activity. However, providing practical and generalizable guidance to coalition practitioners requires development of more encompassing metrics that characterize this detail in more general terms. These more general metrics “bundle” detailed measures into larger constructs that can guide planning, implementation, and capacity building across coalitions, and provide guidance to the settings, purposes, and populations to which they are most applicable. The Coalition Classification Tool (CCT) was revised in 2012 to broaden the dimensions of coalition operations being examined (e.g., collaboration quality, types of coalition strategies, strength of implementation, capacity for SPF steps, cohesiveness, sustainability) to accurately encapsulate conceptually important process measures in analyses of outcomes. Our focus in the next stage will be the development of new summary metrics to further explain what is truly happening at the local level and how these other factors contribute to a coalition’s effectiveness.

Objective 3: Outcomes and Attribution. Simultaneous to the strengthening of process measures and coalition metrics, we will be strengthening community intermediate outcomes, substance use outcomes, and additional related outcomes (e.g., consequence data). Our design and analyses for demonstrating attribution of coalition effects on outcome measures has been strengthened through improved measurement and improved comparison design. The ability to explain the measurable coalition structures, strategies, and implementation characteristics that contribute to attaining outcomes has been provided by the strengthened process measures. These metrics can be entered into multivariate models, which can identify contributing factors and specify them across different community settings, organizational contexts, and populations.

Objective 4: Identify Best Practices. Our focused analyses of contributions to effectiveness by different coalition strategies, our case study analyses, and our cross-site comparisons for site visit coalitions will contribute to a strong ability to identify best practices.

Objective 5: Deliver Useful Reports. The mixed-method richness of the analysis and interpretation provided by our evaluation design will support a variety of products, such as policy briefs and best practices briefs, to convey relevant, understandable, and useful lessons and best practices to policy makers, coalition practitioners, and other stakeholders and interested parties.

Exhibit 3. Objectives and Evaluation Components

Examination of New Strategy and Coalition Classification Tool Data

Beginning in 2012, DFC grantees submitted strategy data in a way that provided improved clarity. Most importantly, DFC grantees were instructed to submit an activity under one key category rather than submitting in multiple ways (and essentially double counting). We have analyzed strategy data submitted through 2013 and have identified three potential orientations into which grantees appear to combine their activities at any given point in time (utilizing principal components analysis and an examination of correlations). Going forward we will continue to assess the utility of thinking about strategy orientations beyond the traditional perspective of focusing on individual strategies or the seven strategies laid out by CADCA in order to communicate about how coalitions engage in activities comprehensively.

Similarly, new CCT data has been collected since 2012 and we have begun to examine that data as well. Initial steps include examining how grantees respond to individual items and how items may be combined into factors. We are also assessing factors over time in order to understand the extent to which coalition processes are stable versus changing. Preliminary analysis beyond descriptives include exploratory factor analysis and correlation analyses.

Outcome Data and Linking Strategy and Process Data to Outcome Data

The next step in the evaluation will seek to continue to understand outcomes associated with the DFC program and to establish potential connections between the strategies used by grantees as well as how coalitions function, to core measure outcomes. The new strategy and CCT data will be one key to this. In addition, we will use a mixed-method evaluation design, continuing to inform any quantitative relationships with what is learned from qualitative data and vice versa. Following is a description of the evaluation methodologies we plan to use:

Assess information from the respondents of YRBS – among other sources – to determine whether DFC results can be aligned to National data. YRBS serves as the primary comparison group as the data collected for YRBS are the most similar. To compare DFC outcomes to YRBS, the confidence intervals for each core measure/substance of the two groups (national sample versus DFC) are examined for any overlap. When there is not an overlap, the difference is considered to be statistically significant. When appropriate alternative national data are available, we will make these comparisons as well. Typically, additional comparisons are descriptive in nature rather than statistical.

Deconstruct Strategies to Identify Best Practices

Once we establish stronger linkages between processes and outcomes, ONDCP can use these results to inform the field about what is working and equally important, what is not. Our goal at this stage is to determine exactly what makes certain coalitions successful, and why.

Case studies will provide the research team the opportunity to:

Conduct interviews with coalition leadership and determine how successful coalitions achieve positive outcomes.

Conduct interviews with coalition partners from a number of agencies to determine best practices in developing healthy collaborative relationships.

Conduct focus groups with young people to determine whether particular prevention strategies are resonating with them.

Determine what local evaluation data may be available for further research.

Determine whether the results of our evaluation are corroborated by the experiences of “front line” staff.

Ensure that our results will be packaged and disseminated in a manner that is useful to DFC grantees.

Case study findings will be aligned with what is learned from aligning strategies and processes to outcomes. In addition, based on case studies collected to date we have proposed adding some additional items to progress reports. Specifically, one key to success appears to be youth coalitions. Our data was not appropriately identifying coalitions who do versus who do not have a youth coalition. In addition, we have proposed clarification on when laws are passed in order to better understand the relationships between changes in laws and changes in outcomes.

Deliver Information on How Coalitions Can Improve Operations and Replicate Best Practices

Our team provides DFC grantees with annual evaluation reports and a high level executive summary. In addition, data is shared with grantees through Ask-An-Evaluator webinars and through presentations at CADCA conferences. We will continue to identify ways to provide coalitions with key information on how to improve operations and replicate best practices. This practical guidance can be used by the field to improve operations, and ultimately, improve performance on the core measures. The goal of this stage is to provide “give back” to both Federal and local stakeholders in order to ensure buy-in and to fulfill our end of the deal to provide practical evaluation results.

3. Data Collection and Management

Data collection and management are critical to supporting timely, accurate, and useful analysis in a large, multi-level, multi-site study such as the DFC National Evaluation. This section outlines the multiple data sources, both historical and planned, that are necessary to such a complex undertaking. The overall data set for this project has several unique characteristics that set the context for our data collection and management planning.

The DFC National Evaluation is ongoing, and a large amount of data has been collected and is available for analysis. As we move forward into the next phase of this evaluation, we will build on this significant body of information to provide continuity and to increase the knowledge return from this valuable data set. Assessment and use of existing data has been discussed at several points in earlier sections.

The National Evaluation team will be modifying current data collection and adding new measures while controlling burden through eliminating data that has not proven useful, and utilizing existing survey and archival data for the same purposes.

The DFC National Evaluation database is complex, and draws from several distinct process and outcome data sources. An adequate and efficient overall data management plan must include procedures and markers (e.g., common site IDs) for integrating these data at with sites/coalitions as the unit of analysis. The system must also efficiently support the ability to create integrated analytic data sets in which data from different sources can be integrated for specific analyses.

This section will outline issues and procedures for collecting and managing these data and is organized by data source.

Data Sources

Current and planned sources are briefly summarized along with significant challenges to be addressed in our planning. They are organized by major data source (progress reports, CCT, public use data, and case study data).

Response burden is a serious issue in any evaluation. After all, if a coalition is overburdened with data collection, they will lose focus on their core mission of reducing substance use and its consequences among youth. We also believe that additional response burden is only acceptable when it produces data that are manageable, measurable, and most importantly, meaningful. Prior to adding any new data collection, the National Evaluation team will first determine whether needed data are available through public use data files. Obtaining additional data from public use data files, such as the Uniform Crime Reports has two major advantages:

It reduces reporting burden on DFC grantees

It allows us to build in historical data on coalition effectiveness, which will provide a stronger basis of evidence for our evaluation.

In the absence of public use data, data needs will need to be addressed in the progress report.

Core Measures

The main focus of this evaluation is on results from the core measures (i.e., 30-day use, perception of risk or harm, perception of parental disapproval, and perception of peer disapproval) for alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and nonmedical marijuana use. DFC grantees are expected to report new data for these measures every two years. The grantees are requested to report data by school grade and gender. The preferred population is school-aged youth in grades 6 through 12, including at least one middle school and at least one high school grade level.

Process Measures

Results on each element in the Strategic Prevention Framework – Assessment, Capacity, Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation – are collected through COMET to describe the range of strategies conducted by DFC coalitions. Most of the information presented is descriptive in nature, and further work will be needed to validate the content and quality of these data.

Coalition Classification Tool (CCT)

The CCT instrument is completed by a representative from each coalition, usually the coalition’s paid staff or evaluator. It contains a large number of process measures.

GPRA Measures

The Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) was established by Congress in 1993 to engage Federal programs in strategic planning and performance measurement. Federal programs–including DFC–are required by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to establish goals, measure performance against those goals, and report results on an annual basis. The DFC currently reports on six GPRA measures:

Percent of coalitions reporting at least 5% improvement in past 30-day alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use in at least one grade.

Percent of coalitions that report positive change in youth perception of risk from alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana in at least two grades.

Percent of coalitions that report positive change in youth perception of parental disapproval of the use of alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana in at least two grades.

With the addition of prescription drugs incorporated into the GPRA measures, we feel that coalition performance will be more accurately assessed and valuable information will be available to understand this growing threat.

Case Studies

Another important data source is qualitative data generated through site visits. The DFC National Evaluation team works with ONDCP to identify key grantees for inclusion in the site visits. To date, this has included high performing grantees, inner city grantees, border community grantees, grantees in tribal communities, and grantees in states that have legalized marijuana use. Going forward, it is anticipated that grantees of interest may include those who have indicated they are addressing synthetics or e-cigarettes and those who work to effectively engage LGBT youth.

These site visits will produce valuable data. The first will be largely qualitative, using information gathered through interviews, focus groups, and brief surveys that will help attribute coalition processes to outcomes. Substance abuse prevention strategies – and especially environmental approaches – are notoriously difficult to attribute to positive outcomes since we are essentially modeling a non-event. The presence of numerous exogenous factors limits our ability to quantify outcomes with certainty; we also need qualitative data to truly understand what is happening and why. The National Evaluation team plans to conduct extensive on-site data collection in order to strengthen attribution of findings, and to collect data on key considerations in the replication of best practices. Strong measurement of setting, design, and implementation characteristics is crucial to maximizing the learning opportunities in a natural variation design. Data will be coded across sites in order to identify potential best practices.

Steps to Improve Data Quality

Data cleaning is an essential component of any evaluation, as any strong analysis must rest on quality data. In the DFC National Evaluation, we will undertake two concurrent strategies to improve the quality of data provided by grantees: (1) validate and refine data cleaning procedures, and (2) provide technical assistance to grantees.

Currently, the data entered by DFC grantees are cleaned at multiple points:

A general cleaning process is conducted by Kit Solutions once data are entered into COMET. Cleaning procedures on the data include range checks and other standard techniques to ensure the quality of the data.

Data are reviewed by SAMHSA project officers for completeness and accuracy. Once data are approved by SAMHSA, they are cleared for release to the National Evaluation team.5

A more in-depth cleaning process is conducted by the National Evaluation team. This cleaning process takes place in two steps:

Raw data are cleaned and processed using structured query language (SQL) code, then appended to existing “raw” databases. Approximately 22,000 lines of SQL code are applied to this process, and most of the procedures involve logic checks within given databases. ICF has completed an initial review of this code, and the cleaning decisions appear to be in line with standard practice. A second round of review will be conducted in the second year of the contract to document all cleaning decisions and to ensure that the cleaning process is transparent to ONDCP.

The raw data are processed to develop a set of “analysis” databases, which – as the name implies – are used for all analyses. Data cleaning procedures conducted at this step mainly involve logic checks both within and across databases.

A final round of data cleaning is conducted within the analysis programs. For example, before data are analyzed, duplicate records are removed (duplicates are created when grantees update records from previous reporting periods).

By ensuring that our data are of the highest quality possible, we can have greater confidence in our findings. Given that DFC is implemented through the Executive Office of the President, and is attended to closely by members of Congress, we expect that this evaluation will be subject to scrutiny. Having confidence in our results is therefore of the utmost priority.

Facilitating Data Collection

Much of the data central to this evaluation is collected or provided by grantee organizations or individual respondents within organizations. As noted above, the National Evaluation team will be conducting extensive data quality and missing data bias analyses on existing data. We will identify major challenges in past data collection and develop responses and procedures that will help ameliorate these challenges. Issues will include the following.

Response burden is a serious issue in any evaluation. After all, if a coalition is overburdened with data collection, they will lose focus on their core mission of reducing substance abuse and its consequences among youth. We also believe that additional response burden is only acceptable when it produces data that are manageable, measurable, and most importantly, meaningful. Prior to adding any new data collection, the National Evaluation team will first determine whether needed data are available through public use data files.

Technical Assistance to Grantees

One of the key limitations in the current evaluation is that we do not know how grantees sampled youth for their surveys. Since the results of these surveys form the core findings for the DFC National Evaluation, we believe that additional steps need to be taken to ensure the validity of the sampling process, and by extension, the validity of our evaluation results.

Through proactive technical assistance to grantees, the National Evaluation team will provide instructions on how to sample students for outcome surveys. We will work with in-house sampling statisticians and vet our plans to ONDCP before they are sent out to grantees. We provide coalitions with a target sample size for their outcome surveys based on the population of the catchment area. For example, given a target population of 10,000 youth, a coalition would need to survey 375 youth to obtain a margin of error of ±5%. We will also emphasize the importance of obtaining a representative sample, although this may be more difficult to codify since all coalitions have different target populations in different settings. Moreover, it is critical that the sampling frame remain consistent so we can accurately measure change across time.

By keeping in contact with grantees, we can also stay up to date on the latest developments in the field, and be in a trusted position to provide guidance on data entry, such as how to classify implementation strategies. We will enhance buy-in for evaluation activities through give-backs, such as policy briefs and practice briefs, and as coalitions see the return on their investment, we believe the result will be better evaluation data.

Data Storage and Protection

DFC data are housed on ICF’s servers, and only the analysis team has authorized access to these data. The data collected as part of this evaluation are the property of ONDCP, and data will be handed back to ONDCP or destroyed at their request. In data reporting, the confidentiality of respondents will be protected, and cell sizes of less than 10 will not be reported to further protect respondents from identification. While we consider this a low-risk project from a human subjects protection perspective, we are nonetheless taking strong precautions to ensure that data are not mishandled or misused in any way.

4. Data Analysis

Analyses of the data will be conducted using methods that are appropriate for the design. Comparison group designs will be analyzed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), while interrupted time series analyses will employ repeated measures methods.

Analysis of GPRA Measures

The Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) was established by Congress in 1993 to facilitate strategic planning and performance measurement. Administered by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Federal programs – including DFC – must establish goals, measure program performance, and annually report their progress in meeting goals.

The following performance measures have been used to meet GPRA reporting requirements:

Percent of coalitions reporting at least 5% improvement in past 30-day alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use in at least one grade.

Percent of coalitions that report positive change in youth perception of risk from alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana in at least two grades.

Percent of coalitions that report positive change in youth perception of parental disapproval of the use of alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana in at least two grades.

DFC grantees report outcome data for GPRA on a bi-annual basis. GPRA performance measures are based on the current four core measures (30-day use, age of onset, perception of risk or harm, and perception of parental disapproval), and are collected using a variety of survey instruments. Grantees can select from a variety of pre-approved instruments or submit their instruments for approval by the National Evaluation team. Because grantees are only required to enter data on a bi-annual basis, different subsets of coalitions are represented in each performance year.

The evaluation team will assess these GPRA measures to determine their effectiveness in measuring coalition performance. Our initial assessment is that these measures need to be modified significantly. Summarizing results across multiple grades (e.g., positive change in perception of risk across two grades) is misleading because some coalitions report data from three grades (as required) and some coalitions report data on all seven grades (grades 6-12 inclusive). The coalitions that report more data therefore have greater opportunities to show “success”.

Our proposed GPRA measures follow:

Percent of coalitions reporting (over a two year period) improvement in past 30-day:

Alcohol use

Tobacco use

Marijuana use

Use of prescription drugs not prescribed to the respondent

Analysis of Core Measures

Our primary impact analyses will be characterized by their simplicity. Given that there are inherent uncertainties in the survey sampling process (e.g., we do not know how each coalition sampled their target population for reporting the core measures, we do not know the exact number of youth served by each coalition), the most logical and transparent method of analyzing the data will be to develop simple averages of each of the core measures. Each average will be weighted by the reported number of respondents. In the case of 30-day use, for example, this will intuitively provide the overall prevalence in 30-day use for all youth surveyed in a given year. The formula for the weighted average is:

![]()

Where wi is the weight (in this case, outcome sample size), and xi is the mean of the ith observation. Simply put, each average is multiplied by the sample size on which it is based, summed, and then divided by the total number of youth sampled across all coalitions.

One key challenge in the weighting process is that some coalitions have reported means and sample sizes from surveys that are partially administered outside the catchment area (e.g., county-wide survey results are reported for a coalition that targets a smaller area within the county). Since means for 30-day use are weighted by their reported sample size, this situation would result in a much higher weight for a coalition that has less valid data (i.e., the number of youth surveyed is greater than the number of youth targeted by the coalition). To correct for this, we will cap each coalition’s weight at the number of youth who live within the targeted zip codes. By merging zip codes (catchment areas) reported by coalitions with 2000 Census data, we can determine the maximum possible weight a coalition should have.6

To measure the effectiveness of DFC coalitions on the core measures for alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and prescription drugs, we will conduct the following related analyses:

Annual Prevalence Figures: First, we will compare data on each core measure by year and school level (i.e., middle school [grades 6–8] and high school [grades 9–12]).7 These results provide a snapshot of DFC grantees’ outcomes for each year; however, since coalitions are not required to report core measures each year, they should not be used to interpret how core measures are changing across time.

Long-Term Change Analyses: Second, we will calculate the average total change in each coalition, from the first outcome report to the most recent results. By standardizing time points, we are able to measure trajectories of change on core measures across time. This provides the most accurate assessment of whether DFC coalitions are improving or not on the core measures. This analysis will be run once use all DFC grantees ever funded data and then a second time using current fiscal year grantees only.

Short-Term Change Analyses: This analysis will include only current fiscal year grantees and will compare their two most recent times of data collection. This analysis will help to identify any potential shifts in outcomes that may be occurring.

Benchmarking Results: Finally, where possible, results will be compared to national-level data from YRBS. These comparisons provide basic evidence to determine what would have happened in the absence of DFC, and allow us to make inferences about the effectiveness of the DFC Program as a whole.

Together, these three analyses provide robust insight into the effectiveness of DFC from a cross-sectional (snapshot), longitudinal (over time), and inferential (comparison) perspective.

Analysis of Process Data

DFC coalitions follow the Strategic Prevention Framework (SPF), which is built upon a community-based risk and protective factors approach to prevention and a series of guiding principles that can be utilized at the Federal, State/Tribal and community levels. For the past five years, grantees have been reporting a wealth of process data corresponding to each step in the SPF (Assessment, Capacity, Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation – supported by cultural competence and sustainability at each step).

Much of the data collected to date has been largely untapped, and the exploration of process data is one of the more exciting opportunities for the next phase of the evaluation. As a first step in the process of analyzing these data, work will be undertaken to assess their validity.

The most common type of validity assessment will involve the linkage of free-form text responses to standardized response categories. For example, DFC grantees are asked to describe their implementation strategies and then, link that activity to one of Seven Strategies for Community Change8:

Provide information

Enhance skills

Provide support

Enhance access/reduce barriers (or reduce access/enhance barriers)

Change consequences

Change physical design

Modify/change policies

While these categories are sufficiently detailed to facilitate analyses, they may not be mutually exclusive in some cases (e.g., students caught using drugs have to attend after-school classes on substance abuse, which would both alter consequences and provide information), and strategies may not be categorized correctly in others. Moreover, some strategies may cross over multiple steps in the SPF (e.g., needs assessment strategies can be found in all five steps of the SPF).

Analyzing Grantee Feedback from Technical Assistance Activities

Technical assistance for the DFC National Evaluation has been designed to accomplish two major objectives: (1) increase the reliability and validity of the data collected from coalition grantees through various technical assistance approaches; and (2) provide “give backs" (i.e., Evaluation Summary Results) to grantees for their use in performance improvement and to support sustainability planning. Analysis of previous evaluation data and interviews with past evaluators revealed that grantees did not have a common frame of reference to define the evaluation data elements they were required to enter. This indicates that DFC grantees need assistance understanding the evaluation process, thus increasing their interest in the DFC National Evaluation process. Additionally, by providing grantees with “give backs” that they can use throughout the course of the evaluation, we increase their likelihood of providing meaningful, valid, and reliable data during data collection.

The Technical Assistance Team will achieve the first objective by working with the Evaluation Team to draft clear and concise definitions for all data elements to be collected. Consequently, coalition grantees will have uniform information for data elements when they are entering progress report data. To further increase the quality of the data collected from grantees, an Evaluation Technical Assistance Hotline (toll-free phone number) and email address have been established. Technical Assistance Specialists provide responsive evaluation support to grantees as questions arise when they are entering the required data. Grantees’ queries are logged and analyzed to develop topics for on-line technical assistance webinars.

The second objective is designed to produce materials that grantees will find useful in their everyday operations, stakeholder briefings, and when they apply for funding for future coalition operations. The Technical Assistance Team will work with the Evaluation Team to refine the format and content for “give back” materials to best suit their needs and then provide grantees with these materials at various points throughout the evaluation. This was also the subject of a focus group discussion at the CADCA Mid-year Training Institute in July 2010.

Overall, these technical assistance activities help to ensure buy-in for evaluation activities, reduce response burden, improve response rates, and ultimately, improve the quality of the data along with providing grantees with evaluation data they can make use of in strengthening their prevention strategies and securing additional funding.

Research Synthesis

One of the largest challenges in the conduct of multi-component, mixed method evaluations is determining how to put all the pieces together to arrive at a consistent and powerful set of findings that can be used to inform both policy and practice.

At the most basic level, the DFC National Evaluation is designed to answer four overarching questions:

Does the DFC Program work (i.e., does the program result in better outcomes, as defined by the core measures)?

How and why does the DFC Program work (i.e., what are the key factors needed to ensure that a coalition is effective)?

In what situations does the DFC Program work better than others (i.e., are there certain settings or types of communities that are inherently more likely to achieve success)?

What are best practices and policies for DFC coalitions (i.e., what specific strategies, policies, and practices maximize chances of success)?

Exhibit 7 lays out all study components described in this document, and which components will contribute to answering each overarching question. Our preliminary plans to synthesize study components rely on the quality and amount of data that can be brought to bear to answer each overarching question. Assuming we have quality data, we can answer the most important overarching question (Does the DFC Program work?) by synthesizing four study components:

The grantee-reported outcome data on the core measures will be used to track trends and prevalence figures among all DFC grantees. Because this is the only outcome data at our disposal that covers all DFC grantees, it will be the central focus of our impact analyses.

Benchmarking to National surveys, such as YRBSwill provide a basis of comparison for DFC to national-level prevalence figures. DFC grantees cover a wide swath of the country, and we can quite easily make the argument that DFC covers a representative sample of youth in the United States. Given that, a statistically significant difference between DFC and YRBS (for example) would provide a clear indication that grantees are effective. The problem with these comparisons, however, is that we oftentimes do not know which communities were sampled; therefore, a given survey could cover only DFC communities – or it could only cover non-DFC communities. Because we cannot separate the DFC from non-DFC prevalence figures in these surveys, it is best to simply call these comparisons exploratory in nature. Still, they will be used to describe whether DFC grantees are producing results in line with National trends, or whether they are over- or under-performing relative to National averages. In addition, the National Evaluation team will conduct a comparative analysis of National surveys, such as the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), Pride, National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), Monitoring the Future (MTF), American Drug and Alcohol Survey (ADAS), and other widely administered surveys. This will provide a better understanding of the biases inherent in each survey and the strength of the inferences we can make by comparing DFC results to these sources.

The GPRA analyses involve wrapping up outcome data (e.g., percent of coalitions reporting improvement in past 30-day alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and prescription drug use). These frameworks for reporting will be used in quasi-experimental studies where possible to both validate the measures and to provide a stronger basis of evidence for the measures.

The synthesis of these impact analyses will not only help us determine whether DFC grantees are making a difference at a given point in time, but also whether trends on the core measures are moving more strongly than the nation as a whole.

The next two overarching questions (How does DFC work? In what situations does DFC work the best?) will be anchored by our Natural Variation Study. By linking these processes and typologies to outcomes, we can exploit the natural variation in coalition operations to determine what works best in given situations.9 The use of quasi-experimental studies will corroborate these findings in a number of settings, which will add to the generalizability of results.

Site visits will provide a strong mixed-method component to the evaluation that will greatly enhance inductive learning from the experience of select, accomplished coalitions; help identify robust best practices with strong external validity (e.g., they work across diverse environments); and provide grounded interpretation of results. Site visit data collection will support (a) developing comparable site-level variables to support meta-analysis of the relation between measured site characteristics and measures of effect, (b) social network analysis to explain the interpersonal and organizational dynamics of coalitions, and (c) case studies will also help us both corroborate our findings and describe specific settings in which some strategies work better than others. These studies will be done at a more granular level, but what we lose in generalizability will be made up in terms of the specificity of our findings. This level of detail produced by the evaluation team will be highly valuable for practitioners looking to implement modifications to their prevention strategies, either from a service or policy context. Critical incidents analyses will allow us to understand the impact of key attenuating circumstances (e.g., change in leadership) on outcomes – and also whether the combination of circumstances (e.g., change in leadership combined with the loss of a key partner) has multiplier effects.

The final overarching question (What are best practices/policies for DFC coalitions?) will be developed based on the results of our intensive case studies (i.e., site visits to coalitions). These case studies will allow us the opportunity to determine how best practices/policies can be replicated, and also the opportunity to collect cost and sustainability data to determine what the best practices are for the price.10 Process data reported through COMET will allow us to determine which coalitions are engaged in such best practices, which will allow us to more carefully observe outcome trajectories of these coalitions to ensure that results are holding up across time.

Exhibit 7. Study Components Designed to Answer Overarching Evaluation Questions |

||||

Study Component |

Does DFC Work? |

How and Why Does DFC Work? |

In What Situations Does DFC Work Better? |

What Are Best Practices and Policies for DFC Coalitions? |

Grantee Reported Outcome Data (biannual reports) |

|

|

|

|

Benchmarking to National Surveys |

|

|

|

|

Natural Variation Study |

|

|

|

|

Grantee Reported Process Data |

|

|

|

|

Coalition Classification Tool/ Typology of Coalitions |

|

|

|

|

GPRA Analyses |

|

|

|

|

Case Studies |

|

|

|

|

Sustainability Study |

|

|

|

|

Cost Study |

|

|

|

|

Ultimately, the exact strategies needed to synthesize results from each study component will depend upon our results and the quality of the data that we can obtain. Our goal is to “tell a story” about how DFC coalitions are working and to synthesize findings in such a manner as to be useful and actionable for both policymakers and practitioners.

Challenges and Limitations

A number of challenges and limitations exist due to the structure of the grant requirements, the nature of the evaluation, and the availability of data. Each challenge is described below, along with a brief description of how each given challenge can be overcome:

We are not confident about whether the core measures are reported for a representative sample within each coalition. DFC grantees are asked to report data on the core measures every two years; however, very little guidance has been provided on sampling plans. We are not certain whether each coalition is providing a representative sample or whether they are “creaming” the results. In the next round of the National Evaluation, we will provide additional guidance on sampling and provide grantees with a target sample size and sampling procedures for their youth surveys. Although we will not be able to guarantee the delivery of data that are representative of the coalition at large, we will still provide guidance to grantees to make sure samples are as representative as possible.

Core measures are reported every two years, which makes interpretation of year-to-year change difficult. The National Evaluation team will conduct cohort studies to understand whether the group of coalitions reporting in even years is substantively different from the coalitions reporting in odd years. Other grantees report data for every year, which adds to the complexity. This contextual information will allow us to understand whether year-to-year fluctuations represent positive or negative movements in results.

There are no public use data files reported at the community level that can be used to develop a comparison group on the core measures. Because we cannot develop a comparison group for every coalition using national-level data, we will have to exploit pockets of similar data (e.g., Arkansas Pride data) that can be used to develop smaller, yet rigorous, impact analyses. The triangulation of these smaller studies will provide a wealth of information for practitioners and policymakers – and answer practical questions, such as “In what settings do DFC coalitions work better than others?”

Response burden needs to be kept to a minimum. Our data collection plan calls for a net reduction in reporting burden. Although we have limited “evaluation capital”11 at our disposal, we believe that reducing reporting burden will actually add to the quality of the evaluation data and overall, we will have more findings to share with confidence. It may seem paradoxical that less data collection will result in more findings, but in our experience, that pattern has held across many of our studies.

Difficulty in linking coalition strategies to community-level changes. Attribution is a significant challenge in this evaluation since DFC grants focus on developing an infrastructure to reduce substance use in the community; direct service provision is not intended to be the primary focus of DFC grantees. It is certainly difficult to attribute lower rates of substance use to the presence of better lighting in a public park; however, because we are conducting a number of separate studies, the triangulation and replication process inherent in our study design will increase our ability to attribute processes to outcomes. We will also develop models to link processes to outcomes.

5. Evaluation Products

With such a large number of stakeholders in this evaluation, the National Evaluation team will need to develop a number of evaluation products. Our plan includes a dissemination strategy that will ensure that coalitions get both a “give back” for their data collection efforts and practical guidance for implementing best practices. Anticipated products include:

Sample Outline of a Best Practices Brief

Introduction to Best Practices Briefs

Layout of the document

How to use best practices briefs

Overview of the Best Practice

Data supporting best practice (impacts found)

Overview of our level of confidence in the data

Detailed description of the best practice

Overview of the practice

How practice is implemented in coalition

Number of students/parents/staff engaged in practice

Theories/other research supporting best practice

Cost

Estimated implementation costs

Estimated maintenance costs

Comparison of costs to other strategies

Communication

Tips for how to communicate the need for this best practice to policymakers

Tips for the types of questions that policymakers will ask practitioners regarding the practice.

Contacts/Resources

Contact information of grantees who can provide advice on implementing the best practice

Further reading/resources on best practices

Optional: One page fact sheet that can be used in discussions with policymakers/funders

Policy Briefs, which will be similar in scope to best practice briefs, but they will be tailored to policymakers. Policy context will be included in lieu of helpful hints for replication.

Interim and Final Reports are the core products of our evaluation. Our reports are typically structured to distill complex evaluation methods and results into easily accessible and practical findings for practitioners.

A Sustainability Study that will share critical information with DFC grantees about preparing for sustainability of coalition initiatives and outcomes. Shortly prior to the end of each grantee’s DFC grant, the National Evaluation team will administer an online survey that will ask coalitions to identify (a) whether they are sustaining operations, (b) what funding, if any, they have received, and (c) best practices for sustainability. The results of this survey (which will be administered by phone if we do not receive a response online) will be shared with current grantees and will ensure that the seed money provided by ONDCP is spent wisely.

Web Content will provide grantees with additional findings and information to improve practice.

Prior to the development of any products (especially the practice briefs and policy briefs), the National Evaluation team will meet with ONDCP and its partners (e.g., SAMHSA, CADCA, etc.) to ensure there is no duplication in our efforts to provide information to grantees. We will also vet products with our Technical Advisory Group, which is comprised of grantees, researchers, and experts with on-the-ground experience, to ensure that they meet the highest standards of quality and provide the most practical results possible.

The upshot of these evaluation activities will be a stronger evidence base, along with more practical information for coalitions. Ultimately, we feel that this approach dovetails well with the needs of the grantees, as well as the mission of ONDCP and SAMHSA.

REFERENCES

Allen, N. (2005). A multilevel analysis of community coordinating councils. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (1/2), 49-63.

Beyers, J.M., Bates, J.E., Pettit, G.S., & Dodge, K.A. (2003). Neighborhood structure, parenting processes, and the development of youths’ externalizing behaviors: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1/2), 35-53.

Brooks-Gunn, J., Duncan, G.J., Klebanov, P.K., & Sealand, N. (1993). Do neighborhoods influence child and adolescent development? American Journal of Sociology, 99(2), 353-395.

Brounstein, P. & Zweig, J. (1999). Understanding Substance Abuse Prevention Toward the 21st Century: A Primer on Effective Programs. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Colder, C.R., Mott, J., Levy, S., & Flay, B. (2000). The relation of perceived neighborhood danges to childhool aggression: A test of mediating mechanisms. American journal of Community Psychology, 28(1), 83-94.

Cross, J.E., Dickman, E., Newman-Gonchar, R., Fagan, J.M. (2009). Using mixed-method design and network analysis to measure development of interagency collaboration. American journal of Evaluation (30)3, 310-329.

Crowel, R. C., Cantillon, D., & Bossard, N. (April, 2009). Building and sustaining systems change in child welfare: Lessons learned from the field. Symposium presentation at the 17th annual National child Care Conference on Child Abuse and Neglect, Atlanta, GA.

Donnermeyer, J.F., Plested, B.A., Edwardes, R.W., Oetting, G., & Littlethunder, L. (1997). Community readiness and prevention programs. Journal of the Community Development Society, 28 (1), 65-83.

Drug Free Communities Support Program Policy Report (2003). Caliber Associates.

Elliott, D.S., Wilson, W.J., Huzinga, D., Sampson, R.J., Elliot, A., & Rankin, B. (1996). The effects of neighborhood disadvantage on adolescent development. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 33(4), 389-426.

Engstrom, M., Jason, L.A., Townsend, S.M., Pokorny, S.B., & Curie, C.J. (2002). Community readiness for prevention: Applying stage theory to multi-community interventions. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community, 24(1), 29-46.

Florin, P., Mitchell, R., & Stevenson, J. (1993). Identifying training and technical assistance needs in community coalitions: A developmental approach. Health Education Research, 8, 417-432.

Florin, P., Mitchell, R., & Stevenson, J. (2000). Predicting intermediate outcomes for prevention organizations: a developmental perspective. Evaluation & Program Planning, 23, 341-346.

Foster-Fishman, P.G., Cantillon, D., Pierce, S.J., & Van Egeren, L.A. (2007). Building an active citizenry: The role of neighborhood problems, readiness, and capacity for change. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 91-106.

Gruenewald, P.J. (1997). Analysis Approaches to Community Evaluation. Evaluation Review, 21(2), 209-230.

Granner, M.L., & Sharpe, P.A. (2004). Evaluating community coalition characteristics and functioning: A summary of measurement tools. Health Education Research, 19(5), 514-532.

Kakocs, R.C., & Edwards, E.M. (2006). What explains community coalition effectiveness?: A review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30(4), 351-361.

Nunnally, J.C., & Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw Hill, New York.

Porowski, A., Landy, L., & Robinson, K. (2004). Key outcomes and methodological strategies employed in the Drug-Free Communities Support Program. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Prevention Research, Quebec City, Canada.

Roussos, S.T., & Fawcett, S.B. (2000). A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annual Review of Public Health, 21, 369-402.

Sampson, R.J., Morenoff, J.D., & & Gannon-Rowley, T. (2002). Assessing “neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions for research. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 443-478.

Shadish, W.R., Cook, T.D., & Campbell, D.T. (2002). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Influence. Boston: Houghton Mifflin company.

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Watson-Thompson, J., Fawcett, S.B., & Schulz, J. A. (2008). Differential effects of strategic planning on community coalitions in two urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Community Psychology 42, 25-38.

Wolf, T. (2001). Community Coalition Building – Contemporary Practice and Research: Introduction. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(2), 165-172.

1 Brounstein, P. & Zweig, J. (1999). Understanding Substance Abuse Prevention Toward the 21st Century: A Primer on Effective Programs. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

2 Wolf, T. (2001). Community Coalition Building – Contemporary Practice and Research: Introduction. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(2), 165-172.

3 Gruenewald, P.J. (1997). Analysis Approaches to Community Evaluation. Evaluation Review, 21(2), 209-230.

4 New core measures have been proposed for this evaluation. As part of our plan to implement these core measures, we will ask grantees to provide data from prior years on these measures, if practicable. In other words, in the collection of new core measures, we will try to immediately accumulate historical data to assess trends over time.

5 ICF will explore the option of providing training to SAMHSA project officers on the review of COMET data.

6 2010 Census data will be released starting in April 2011, with all data released by September 2013. ICF will update catchment area data as these new data come in.

7 Coalitions were asked to report data by school level and gender; however, given that only nine coalitions have reported results exclusively by gender (out of 731 coalitions that reported on 30-day use) – and sample sizes were much larger for school-level breakouts – we do not believe that presenting data by gender will add significantly to our understanding of trends in overall prevalence figures. We will, however, present patterns in results by gender when they are notable.

8 Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America (2009). Handbook for Community Anti-drug Coalitions. Retrieved 2/16/10 from http://www.cadca.org/ and originally from the University of Kansas Work Group on Health Promotion and Community Development—a World Health Organization Collaborating Centre.

9 This can be an incredibly complex inquiry since context will differ in each coalition. By using multivariate analyses to control for a set of potential moderating variables, we hope to isolate the conditions under which certain strategies work best. Answering complex questions such as this also require extensive qualitative data.

10 We will have to consider both the investment of DFC grant funds into the community and the coalition’s ability to leverage other funding.

11 Evaluation capital refers to the amount of burden we can impose on grantees before those burdens ultimately result in lower quality data – or less cooperation with evaluation staff.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| File Title | Drug Free Communities National Evaluation |

| Author | Allan |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2021-01-24 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy