Cort Ssa

CORT SSA.docx

Center for Substance Abuse Prevention Online Reporting Tool (CORT)

OMB: 0930-0354

SUPPORTING STATEMENT FOR THE

CENTER FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE PREVENTION ON-LINE

REPORTING TOOL AND GRANT PROGRAMMATIC PROGRESS REPORT

Check off which applies:

☐ New

☒ Revision

☐ Reinstatement with Change

☐ Reinstatement without Change

☐ Extension

☐ Emergency

☐ Existing

JUSTIFICATION

A.1. Circumstances of Information Collection

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA), Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP) is requesting approval from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to monitor CSAP discretionary grant programs through administration of a suite of data collection instruments for grant compliance and programmatic performance monitoring. This package describes the data collection activities and proposed instruments. Grant compliance monitoring will be conducted via a single data collection instrument to be completed by all CSAP discretionary grant recipients. Programmatic performance monitoring will be conducted via a suite of data collection instruments with each instrument tailored to a specific CSAP discretionary program. This request for data collection will replace OMB No. 0930-0354: Division of State Programs – Management Reporting Tool.

The Center for Substance Abuse Prevention Grant Programmatic Progress Report (PPR) instrument will be used to monitor grant compliance monitoring. This single instrument will be completed by all CSAP discretionary grant recipients. The Center for Substance Abuse Prevention Online Reporting Tool (CORT) will be used to conduct programmatic performance monitoring and each grant program will have a tailored version that aligns with its specific programmatic requirements. This instrument is comprised of two main sections: 1) CORT Annual Targets Report section to for CSAP discretionary grant recipients to report annual federal fiscal year programmatic goals, and 2) CORT Quarterly Performance Reports section for grantees to report grant activities implemented during each federal fiscal quarter. In developing the CORT Annual Targets Report and the Quarterly Performance Reports, CSAP sought the ability to elicit programmatic information that demonstrates impact at the program aggregate level.

In this way, data collected through this instrument are necessary to ensure SAMHSA and grantees comply with requirements under the Government Performance and Results Modernization Act of 2010 (GPRA) that requires regular reporting of performance measures. Additionally, data collected through the CORT will provide critical information to SAMHSA’s Government Project Officers related to grant oversight, including barriers and facilitators that the grantees have experienced, and an understanding of the technical assistance needed to help grantees implement their programs. The information also provides a mechanism to ensure grantees are meeting the requirements of the grant funding announcement as outlined in their notice of grant award. In addition, the tool reflects CSAP’s desire to elicit pertinent program level data that can be used not only to guide future programs and practices, but also to respond to stakeholder, congressional and agency inquiries.

SAMHSA requests approval for the following suite of data collection instruments as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Data Collection Tools

Instrument Name |

Attachment |

Grant Level Compliance |

|

Grant Programmatic Progress Report |

1 |

Program Level Performance Monitoring |

|

Center for Substance Abuse Prevention On-line Report Tool (CORT) Annual Targets and Quarterly Performance Reports |

|

Strategic Prevention Framework - Partnerships for Success (SPF-PFS) |

2 |

Sober Truth on Preventing Underage Drinking (STOP Act) |

3 |

Strategic Prevention Framework for Prescription Drugs (SPF Rx) |

4 |

First Responders-Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (FR CARA) |

5 |

Grants to Prevent Prescription Drug/Opioid Overdose-Related Deaths (PDO) |

6 |

Improving Access to Overdose Treatment (ODTA) |

7 |

SAMHSA’s underage drinking programs are authorized under 42 U.S.C. 290bb-25b: Programs to reduce underage drinking and CSAP’s SPF-PFS and SPF Rx programs are authorized under 42 USC 290bb-22: Priority substance use disorder prevention needs of regional and national significance. The First Responders – Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act programs is authorized under 42 U.S.C. 290ee-1: First responder training. Grants to Prevent Prescription Drug/Opioid Overdose-Related Deaths are authorized under Section 516 of the Public Health Service Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 290bb-22. Improving Access to Overdose Treatment are authorized under Section 544 of the Public Health Service Act. This data collection effort is supported by Subsection c (1): Recipients of grants, contracts, and cooperative agreements under this section shall comply with information and application requirements determined appropriate by the Secretary. The grant program is summarized below.

Strategic Prevention Framework - Partnerships for Success (SPF-PFS) – The purpose of the SPF-PFS program is to help reduce the onset and progression of substance misuse and its related problems by supporting the development and delivery of state and community substance misuse prevention and mental health promotion services. This program is intended to promote substance use prevention throughout a state jurisdiction for individuals and families by building and

expanding the capacity of local community prevention providers to implement evidence-based programs. In addition, the program is intended to expand and strengthen the capacity of local community prevention providers to implement evidence-based prevention programs. With this program, SAMHSA aims to strengthen state and community level prevention capacity to identify and address local substance use prevention concerns, such as underage drinking, marijuana, tobacco, electronic cigarettes, opioids, methamphetamine, and heroin.

Sober Truth on Preventing Underage Drinking (STOP Act) - The purpose of this program is to prevent and reduce alcohol use among youth and young adults ages 12-20 in communities throughout the United States through evidence-based screening, programs and curricula, brief intervention strategies, consistent policy enforcement, and environmental changes that limit underage access to alcohol as authorized by942 U.S.C. 290bb-25b. The program aims to: (1) address norms regarding alcohol use by youth, (2) reduce opportunities for underage drinking, (3) create changes in underage drinking enforcement efforts, (4) address penalties for underage use, and/or (5) reduce negative consequences associated with underage drinking.

Strategic Prevention Framework for Prescription Drugs (SPF Rx) – The purpose of the SPF Rx grant program is to provide resources to help prevent and address prescription drug misuse within a State or locality. The program is designed to raise awareness about the dangers of sharing medications as well as the risks of fake or counterfeit pills purchased over social media or other unknown sources, and work with pharmaceutical and medical communities on the risks of overprescribing. Whether addressed at the state level or by an informed community-based organization, the SPF Rx program will raise community awareness and bring prescription substance misuse prevention activities and education to schools, communities, parents, prescribers, and their patients. In addition, grant recipients will be required to track reductions in opioid related overdoses and incorporate relevant prescription and overdose data into strategic planning and future programming.

First Responders-Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act Grants (FR CARA) - The purpose of this program is to allow first responders and members of other key community sectors to administer a drug or device approved or cleared under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) for emergency treatment of known or suspected opioid overdose.

Grants to Prevent Prescription Drug/Opioid Overdose-Related Deaths (PDO) - The purpose of this program is to support first responders and members of other key community sectors to administer a drug or device approved or cleared under the FD&C Act for emergency reversal of known or suspected opioid overdose. Recipients will train and provide resources to first responders and members of other key community sectors at the state, tribal, and local levels on carrying and administering a drug or device approved or cleared under the FD&C Act for emergency treatment of known or suspected opioid overdose.

Improving Access to Overdose Treatment (ODTA) - The purpose of this program is to expand access to naloxone and other Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved overdose reversal medications for emergency treatment of known or suspected opioid overdose. The recipients will collaborate with other prescribers at the community level to implement trainings on policies, procedures, and models of care for prescribing, co-prescribing, and expanding access to naloxone and other FDA-approved overdose reversal medications to the specified population of focus (i.e., rural or urban). With this program SAMHSA aims to expand access to naloxone and other FDA approved overdose reversal medications for emergency treatment of known or suspected opioid overdose.

Background

As the Nation faces twin crises of the fourth wave of the opioid epidemic (Ciccarone, 2022) and the youth mental health crisis (Murthy, 2021), substance use prevention remains a priority for SAMHSA (SAMHSA, 2023). As described below, we are making strides on reducing some measures of youth substance use, but there is still a significant distance to go. Fentanyl-related overdose deaths have nearly tripled from 2019 to 2021, including adolescent overdose deaths. (CDC, 2023). Over the past decades, a large number of evaluation studies demonstrated that prevention interventions effectively reduce substance use, as well as delinquent behaviors; violence; and other mental, emotional, and behavioral health problems (e.g., Blow, 2020, Calear & Christensen, 2010; Lemstra et al., 2010; Ttofi & Farrington, 2011). Cost benefit analyses also show that investments in prevention yield cost savings to not only the individual and family, but to the community and state as well (Washington State Institute for Public Policy, 2015). SAMHSA continues to fund grants to support critical prevention work. This data collection package will help inform SAMHSA on the performance and progress of these investments.

Underage Drinking

Alcohol use is responsible for more than 3,900 deaths annually among youth under age 21 in the United States (2022). Underage drinking (UAD) also contributes to a wide range of costly health and social problems, including motor vehicle crash injuries, suicide, interpersonal violence (e.g., homicides, sexual and other assaults), unintentional injuries (e.g., burns, falls, drownings), cognitive impairment, alcohol use disorder (AUD), risky sexual behaviors (Brown, Gause, & Northern, 2016), poor school performance, and alcohol and drug overdoses.

UAD causes serious harm to the adolescent drinker as well as to the community as a whole (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2012). Alcohol use by adolescents negatively effects brain development, results in other serious health consequences (e.g., alcohol poisoning, risky sexual behaviors, and addiction), and leads to safety consequences from driving under the influence, poisonings, and other injuries. UAD places youth at increased risk for violence and victimization along with social or emotional consequences (e.g., low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, lack of self-control, stigmatization by peers), academic consequences (e.g., poor academic performance, truancy, suspension, or expulsion from school), and family consequences (e.g., poor relationships with parents).

Adolescent drinking can also impose economic consequences, ranging from personal costs (e.g., payment for AUD treatment or medical services) to familial costs (e.g., parents taking time off work to drive children to treatment) to community costs (e.g., providing enforcement, supervision, or treatment to underage drinkers). Sacks et al. (2015) estimated that in 2010, UAD was responsible for $24.3billion (9.7%) of the total cost to society of excessive alcohol consumption in the United States.

There are three national surveys funded by the federal government that collect data on underage drinking and its consequences. They are the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), Monitoring the Future (MTF), and the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS).

Data from NSDUH show that among 12- to 20-year-olds from 2021 to 2022, rates of current alcohol (past month) use decreased slightly from 15.6% to 15.1%. The reporting of past month binge drinking also declined slightly from 8.6% in 2021 to 8.2% in 2022. Heavy alcohol use increased slightly from 1.6 in 2021% to 1.7% in 2022 (SAMHSA, 2022). Due to changes in the methodology for survey administration, the reporting of NSDUH estimates from prior years (before 2020) can be misleading and it is not appropriate to compare 2022 estimates with prior years. Regardless of this limitation, NSDUH results from 2022 provide important to help inform efforts related to prevention efforts related to substance misuse. It is still important to highlight that percentages when translated to individuals reflect that approximately 6 million underage people reported current use of alcohol, 3 million reported binge drinking, and 646,000 reported heavy alcohol use (SAMHSA, 2022).

Results from MTF show that among eighth graders the prevalence of alcohol use in the last 30 days decreased from 7.3% in 2021 to 6.0% in 2022 (MTF, 2022). Among both tenth graders the prevalence of alcohol use in the last 30 days increased slightly from 13.1% in 2021 to 13.6% in 2022 (MTF, 2022). An increase was also seen amongst twelfth graders who used alcohol in last 30 days from 25.8% in 2021 to 28.4% in 2022. (MTF, 2022).

Results from YRBS rom show that the reporting of current alcohol use among high school students decreased between 2019 (29.2%) and 2021 (22.7%). In addition, binge drinking also decreased between 210 (13.7%) and 2021 (10.5%). High school students reporting the largest number of drinks they had in a row was 10 or more decreased between 2019 (3.1%) and 2021 (2.7%).

In response to this, SAMHSA implemented the STOP Act and SPF PFS grant programs to target UAD prevention efforts.

Opioid

Drug-related overdose has become the nation’s leading cause of accidental death, with deaths from opioid overdose playing a significant role in this increase. From 1999-2021, nearly 645,000 people died from overdoses involving any opioid, including prescription and illicit opioids (CDC, 2022). Addressing the continuing overdose epidemic (opioid misuse, opioid use disorder, and opioid overdose) is another public health crisis SAMHSA has prioritized.

The overdose epidemic can be described as occurring in three distinct waves. The first wave began with increased prescribing of opioids in the 1990s, with overdose deaths involving prescription opioids (natural and semi-synthetic opioids and methadone) increasing since at least 1999 (CDC, 2011). The second wave began in 2010, with rapid increases in overdose deaths involving heroin (Rudd, et al., 2014). The third wave began in 2013, with significant increases in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids, particularly those involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl (O’Donnell, et al., 2017). From a recent paper published by Friedman and Shover, point to an emerging fourth wave. This fourth wave is one characterized by the use of illegally manufactured opioids in combination with psychostimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine.

Data from the 2022 NSDUH showed that among people aged 12 or older, 3.2 percent (or 8.9 million people) reported misused opioids (heroin or prescription pain relievers) in the past year (SAMHSA, 2022). This is a slight decrease from 2021 in which 3.4% or 9.4 million people reported misused opioids (SAMHSA, 2022). Of note, the 2021 and 2022 estimates do not include illegally made fentanyl. Due to changes in the methodology for survey administration, the reporting of NSDUH estimates from prior years (before 2020) can be misleading and it is not appropriate to compare 2022 estimates with prior years.

In response to this, SAMHSA implemented a number of grant programs to target opioid overdose prevention. FR CARA and PDO provide funding to states and communities to purchase naloxone, a medication designed to rapidly reverse an opioid overdose, and to train individuals on how to administer it. SPF-Rx provides funding to improve utilization of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs).

A.2. Purpose and Use of Information

The CORT and PPR are tools that will enable GPOs and other CSAP staff to monitor grantee activities. The CORT gathers information through a web-based data collection system that uses clickable radio buttons, check boxes, drop-down choice items, and a limited number of open-ended text boxes as relevant. It also allows grantees to upload required documents requested by their GPO and as required in their Notice of Funding Announcement. The CORT will likely be completed by the grantee Project Director, Evaluator, or designee. The Annual Targets section will be completed annually and the Quarterly Progress Report section each quarter. The PPR will be uploaded to the grantee’s official electronic grant folder, located in electronic Research Administration (eRA) Commons.

The information is used by individuals at three different levels: 1) the Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and SAMHSA leadership, 2) program-level SAMHSA staff, including CSAP leadership and Government Project Officers (GPOs), and 3) grantees:

Assistant Secretary Level – The information is used to inform the Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use of the performance and outcomes of the programs funded through the Agency. The performance is based on the goals of the grant program. This information serves as the basis of annual GPRA measurement reporting to Congress contained in the Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees.

Center Level – In addition to providing information about the performance of the various programs, the information is used to monitor and manage individual grant projects within each program. The information is used by GPOs to identify program strengths and weaknesses, to provide an informed basis for providing technical assistance and other support to grantees, to inform funding decisions, and to identify potential issues for additional evaluation.

Grantee Level – In addition to monitoring performance and outcomes, the grantee staff use the information to monitor the requirements of the grant funding announcement as outlined in their notice of grant award.

In summary, the data collected through CORT will be a crucial resource for CSAP in setting prevention policy priorities, measuring program performance, and designing and promoting optimally effective prevention program initiatives.

A.3. Use of Information Technology

Grant Level Compliance: Programmatic Progress Report (PPR)

All SAMHSA awards require grantees to submit performance and progress reports through the electronic Research Administration (eRA) Commons, an end-to-end Grants Management system, (Exhibit 1). The frequency (ranging from quarterly to annually) and program-specific instructions for preparation and submission of these reports are identified in the terms and conditions found in the Notice of Award.

The system requires a web browser and access to the Internet. Users are able to access the system 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, aside from scheduled maintenance windows, through the use of an encrypted username and password. Levels of access have been defined for users based on their authority and responsibilities regarding the data and reports.

Exhibit 1. Main Screen of eRA

Program Level Performance Monitoring: Center for Substance Abuse Prevention On-line Report Tool (CORT) - Annual Targets and Quarterly Performance Reports

CSAP grant programs collect information using a variety of methods, including paper-and-pencil and electronic methods. This project will not interfere with ongoing program collection operations that facilitate information collection at each site.

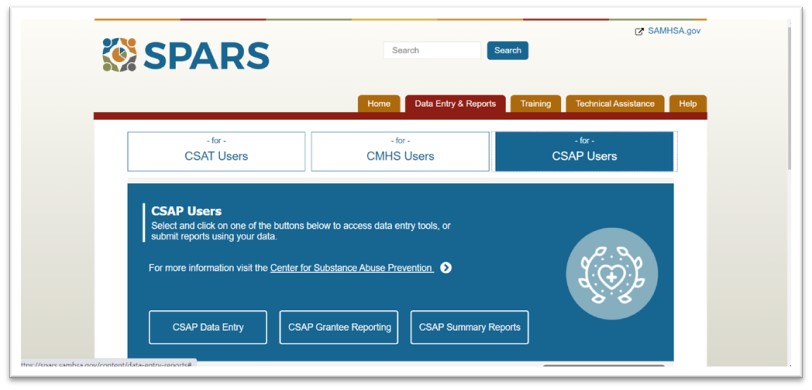

To maximize data accuracy and reliability, a web-based data collection and entry system, SAMHSA’s Performance Accountability and Reporting System (SPARS), has been developed and is currently used and available to all programs for data collection. The system requires a web browser and access to the Internet. Users are able to access the system 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, aside from scheduled maintenance windows, through the use of an encrypted username and password. Levels of access have been defined for users based on their authority and responsibilities regarding the data and reports.

Upon logging into a system-assigned account, grantees are able to: enter data on their program; upload documents for the project officer review and generate reports of their activities. Skip patterns facilitate navigation through the instrument by only displaying items that apply to the respondent, based on information already entered into the system. The system also allows SAMHSA’s GPOs to review and approve submitted progress reports or ask the grantee to provide additional information regarding their activities. Government Project Officers also have the capability to generate online summary reports on their grantees’ progress. A screenshot of the data entry screen on SPARS is below (Exhibit 2):

Exhibit 2. SPARS Data Entry Screen.

A.4. Effort to Identify Duplication

The items collected are necessary to assess grantee performance. CSAP is promoting the use of consistent performance and outcomes measures across all CSAP grant programs; this effort will result in less overlap and duplication and will substantially reduce the burden on grantees that results from data demands associated with individual programs.

SAMHSA will work closely with the grantees to identify whether other data are being collected by the grantee, which may be redundant to the respective CSAP grant programs. When duplication is identified, SAMHSA and the grantees will identify a priority action plan to reduce the duplicative efforts and streamline the data items to reduce burden.

A.5. Involvement of Small Entities

Grantees will usually consist of State agencies, tribal organizations, and other jurisdictions. Every effort has been made to minimize the number of data items collected from all programs down to the least number of items necessary to accomplish the objectives described within and meet GPRA reporting requirements. Therefore, there is no significant impact to small entities.

A.6. Consequences If Information Collected Less Frequently

The multiple data collection points for the suite of data collection instruments are necessary to track and monitor grant compliance and programmatic performance monitoring over time. In addition, SAMHSA will use the data for the purposes of evaluation. Less frequent reporting will affect SAMHSA’s and the grantees’ ability to do so effectively. For example, SAMHSA’s federal requirements require them to report on performance and GPRA measures once each year. Federal health disparities priorities require periodic reports of the activities used to address those priorities.

SAMHSA has made every effort to ensure that data are collected only when necessary and that extraneous collection will not be conducted. As part of this effort, cognitive testing will be performed that will include CSAP grantees. Feedback that is received from the cognitive testing may result in revisions to the PPR and CORT.

A.7. Consistency With the Guidelines in 5 CFR 1320.5(d)(2)

This information collection fully complies with the guidelines in 5 CFR 1320.5(d)(2). However, SAMHSA seeks an exception to OMB’s Revisions to OMB's Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity posted to the federal register on 3/29/2024. Specifically, SAMHSA is requesting to use the minimum categories outlined in Figure 3 of the Directive No. 15 for the MAI-PORT instrument. The MAI-Port is not a tool designed for program participants to complete. Rather, it is a way for grantees to report aggregate information about their program. Definitions and examples of each race and ethnicity category are found in the MAI-PORT instrument’s Appendix A - List of Definitions. OMB’s approach using more detailed categories outlined in Figure 1 of Directive No. 15 would require grantees to submit a massive amount of written responses to SAMHSA. We would ultimately aggregate this information, and it could be very burdensome for grantees to report. We don’t need the write-in responses; we only need the total of individuals that provide a written response.

A.8. Consultation Outside the Agency

The notice required by 5 CFR 1320.8(d) was published in the Federal Register on March 14, 2024 (89 FR 18653).

As part of the development of the PPR and CORT suite of tools, cognitive testing will be performed that will include CSAP grantees.

A.9. Payment to Respondents

No cash incentives or gifts will be given to respondents.

A.10. Assurance of Confidentiality

Data will be kept private to the extent allowed by law. SAMHSA has statutory authority to collect data under the Government Performance and Results Act (31 USC 1115) and is subject to the Privacy Act for the protection of these data. Only aggregate data will be collected with the PPR and CORT instruments. SAMHSA and its contractors will not receive identifiable client records from the grantee staff. Grantee staff will provide information about their organizations and their activities, rather than information about individuals they serve.

The contracting team takes responsibility for ensuring that the Web and data system is properly maintained and monitored. Server staff will follow standard procedures for applying security patches and conducting routine maintenance for system updates. Data will be stored on a password-protected server, and access to data in the system will be handled by a hierarchy of user roles, with each role conferring only the minimum access to system data needed to perform the necessary functions of the role.

While not collecting individual-level data, contractor staff are trained on the importance of privacy and in handling sensitive data.

A.11. Questions of a Sensitive Nature

SAMHSA’s mission is to lead public health and service delivery efforts that promote mental health, prevent substance misuse, and provide treatments and supports to foster recovery while ensuring equitable access and better outcomes. For the PPR and CORT instruments, the instruments will be used to report on performance is at the aggregate level. There are no questions of a sensitive nature that are asked of individuals as the data collection is focused at the grantee level and not the individual participant level.

A.12. Estimates of Annualized Hour Burden

Table 2 and Table 3 provides an overview of the data collection method, frequency of data collection, and number of times each tool is collected for the PPR and CORT data collection instruments.

Table 2. CSAP’s Grant Programmatic Progress Report (Grant Compliance)

Instrument |

Data Collection Method |

Frequency of Data Collection |

Maximum Number of Data Collections |

Attachment Number |

Grant Programmatic Progress Report |

Grantees submit into eRA |

Yearly

|

Yearly: 5 times (once per year)

Years 1–5 |

1 |

Table 3. CSAP On-line Data Collection Tool - Annual Targets and Quarterly Performance Reports (Program Performance Monitoring)

Instrument |

Data Collection Method |

Frequency of Data Collection |

Maximum Number of Data Collections |

Attachment Number |

SPF-PFS |

Grantees submit into SPARS |

Yearly: Annual targets

Quarterly: Performance reports |

Yearly: 5 times (once per year)

Quarterly: 20 times (four time per year)

Years 1–5 |

2 |

STOP Act |

Grantees submit into SPARS |

Yearly: Annual Targets

Quarterly: Performance reports |

Yearly: 5 times (once per year)

Quarterly: 20 times (four time per year)

Years 1–5 |

3 |

SPF Rx |

Grantees submit into SPARS |

Yearly: Annual targets

Quarterly: Performance reports |

Yearly: 5 times (once per year)

Quarterly: 20 times (four time per year)

Years 1–5 |

4 |

FR CARA |

Grantees submit into SPARS |

Yearly: Annual targets

Quarterly: Performance reports |

Yearly: 5 times (once per year)

Quarterly: 20 times (four time per year)

Years 1–5 |

5 |

PDO |

Grantees submit into SPARS |

Yearly: Annual targets

Quarterly: Performance reports |

Yearly: 5 times (once per year)

Quarterly: 20 times (four time per year)

Years 1–5 |

6 |

ODTA |

Grantees submit into SPARS |

Yearly: Annual targets

Quarterly: Performance reports |

Yearly: 5 times (once per year)

Quarterly: 20 times (four time per year)

Years 1–5 |

7 |

Annual Burden Hours

CSAP Grant Program |

Number of Respondents |

Responses per Respondent |

Total Number of Responses |

Hours per Response |

Total Burden Hours |

PPR |

657 |

1 |

657 |

4 |

2628 |

SPF-PFS |

315 |

1 |

315 |

1 |

315 |

STOP Act |

202 |

1 |

202 |

1 |

202 |

SPF Rx |

27 |

1 |

27 |

1 |

27 |

FR CARA |

87 |

1 |

87 |

1 |

87 |

PDO |

18 |

1 |

18 |

1 |

18.0 |

ODTA |

8 |

1 |

8 |

1 |

8 |

Total |

1,314 |

|

1314 |

|

3285 |

The time to complete the instruments is estimated in Tables 4 through 7. These estimates are based on current funded CSAP grant programs.

Table 4. Annualized Burden Table: CSAP’s Grant Programmatic Progress Report

CSAP Grant Program |

Number of Respondents |

Responses per Respondent |

Total Number of Responses |

Hours per Response |

Total Burden Hours |

Average Hourly Wage1 |

Total Respondent Cost |

SPF-PFS |

315 |

1 |

315 |

4 |

1,260 |

$48.35 |

60,921.00 |

STOP Act |

202 |

1 |

202 |

4 |

808 |

$48.35 |

39,066.80 |

SPF Rx |

27 |

1 |

27 |

4 |

108 |

$48.35 |

5,221.80 |

FR CARA |

87 |

1 |

87 |

4 |

348 |

$48.35 |

16,825.80 |

PDO |

18 |

1 |

18 |

4 |

72 |

$48.35 |

3,481.20 |

ODTA |

8 |

1 |

8 |

4 |

32 |

$48.35 |

1,547.20 |

Total |

657 |

|

657 |

|

2,628 |

|

127,063.80 |

1Grantee Project Director or Evaluator hourly wage is based on the mean hourly wage for state government managers, as reported in the 2022 Occupational Employment (OES) by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) found at https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/naics4_999200.htm#11-0000 Accessed on December 13, 2023.

Table 5. Annualized Burden Table: CORT - Annual Targets

CSAP Grant Program |

Number of Respondents |

Responses per Respondent |

Total Number of Responses |

Hours per Response |

Total Burden Hours |

Average Hourly Wage1 |

Total Respondent Cost |

SPF-PFS |

315 |

1 |

315 |

1 |

315 |

$48.35 |

15,230.25 |

STOP Act |

202 |

1 |

202 |

1 |

202 |

$48.35 |

9,766.70 |

SPF Rx |

27 |

1 |

27 |

1 |

27 |

$48.35 |

1,305.45 |

FR CARA |

87 |

1 |

87 |

1 |

87 |

$48.35 |

4,206.45 |

PDO |

18 |

1 |

18 |

1 |

18.0 |

$48.35 |

870.30 |

ODTA |

8 |

1 |

8 |

1 |

8 |

$48.35 |

386.80 |

Total |

657 |

|

657 |

|

657 |

|

31,765.95 |

1Grantee Project Director or Evaluator hourly wage is based on the mean hourly wage for state government managers, as reported in the 2022 Occupational Employment (OES) by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) found at https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/naics4_999200.htm#11-0000 Accessed on December 13, 2023.

Table 6. Annualized Burden Table: CORT - Quarterly Performance Report

CSAP Grant Program |

Number of Respondents |

Responses per Respondent |

Total Number of Responses |

Hours per Response |

Total Burden Hours |

Average Hourly Wage1 |

Total Respondent Cost |

SPF-PFS |

315 |

4 |

1,260 |

6 |

7,560 |

$48.35 |

365,526.00 |

STOP Act |

202 |

4 |

808 |

5.75 |

4,646 |

$48.35 |

224,634.10 |

SPF Rx |

27 |

4 |

108 |

6 |

648 |

$48.35 |

31,330.80 |

FR CARA |

87 |

4 |

348 |

6 |

2,088 |

$48.35 |

100,954.80 |

PDO |

18 |

4 |

72 |

6 |

432 |

$48.35 |

20,887.20 |

ODTA |

8 |

4 |

32 |

6 |

192 |

$48.35 |

9,283.20 |

Total |

657 |

|

2,628 |

|

15,566 |

|

752,616.10 |

1Grantee Project Director or Evaluator hourly wage is based on the mean hourly wage for state government managers, as reported in the 2022 Occupational Employment (OES) by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) found at https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/naics4_999200.htm#11-0000 Accessed on December 13, 2023.

CSAP assumes the number of responses will vary by year based on available funding. Therefore, the burden and respondent cost may vary by year. Table 7 provides an overview of the total estimated number of responses year. Starting with Year 2, the estimated total responses are based on current Congressional appropriations.

Table 7. Burden Totals by Year – All data collection instruments

Year |

# of grantees |

Annual Burden Hours |

Total burden hours |

Hourly wages |

Total cost |

Year 1 |

657 |

~28.69 |

18,851 |

$48.35 |

911,445.85 |

Year 2 |

700 |

29 |

20,088 |

$48.35 |

$971,254.80 |

Year 3 |

700 |

29 |

20,088 |

$48.35 |

$971,254.80 |

Year 4 |

700 |

29 |

20,088 |

$48.35 |

$971,254.80 |

Year 5 |

700 |

29 |

20,088 |

$48.35 |

$971,254.80 |

Total |

3,457 |

|

99,203 |

|

$4,796,465.05 |

1Grantee Project Director or Evaluator hourly wage is based on the mean hourly wage for state government managers, as reported in the 2022 Occupational Employment (OES) by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) found at https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/naics4_999200.htm#11-0000 Accessed on December 13, 2023.

A.13. Estimates of Annualized Cost Burden to Respondents

There are no respondent costs for capital or start-up or for operation or maintenance.

A.14. Estimates of Annualized Cost to the Government

The total estimated cost to the government for the data collection from FY 2024 through FY 2029 is $2,914,020. This includes approximately $75,008 per year for SAMHSA costs to manage/administer the data collection and analysis for 25% each of two employees (GS-14-5, $150,016 annual salary). Approximately $507,796 per year represents SAMHSA costs to monitor and approve grantee reporting in these instruments (10% time of 40 Project Officers (GS-13-5) at $126,949 annual salary). The annualized cost is approximately $582,804.

A.15. Changes in Burden

Since the publication of the 60-day Federal Registry Notice, changes were made to the burden estimates. These changes reflect the feedback received during the 60- day public comment period and the cognitive testing. Even though public commenters and cognitive testing respondents reported the new instruments as far less burdensome than the current OMB approved instruments, they reported burden estimates for the previous instruments and the newly proposed instruments were underestimated. As a result of this feedback, the revised burden estimates were increased to reflect a more realistic estimation of public burden.

A.16. Time Schedule, Publications, and Analysis Plan

Time Schedule

Time Schedule for Data Collection

Activity |

Time Schedule |

Obtain OMB approval for data collection |

December 2024 |

Collect data |

January 2025–October 2029 |

Analyze data --Quantitative data submitted through the annual targets and quarterly performance reports |

March 2025–October 2029 |

Disseminate of

findings |

Ongoing for monitoring purposes. |

Publications

Reports summarizing the PPR and CORT data will be prepared for the internal use of SAMHSA. CORT will primarily be used by SAMHSA Government GPOs to monitor the progress of their grantees. Additional audiences for these reports will include Congress, SAMHSA Contracting Officer’s Representatives (CORs), grantees, and the broader substance use prevention field (e.g., academia, researchers, policymakers, providers). Also, data from the reports will be used for evaluation purposes, as the process data may inform specific outcomes.

The data also may be shared at professional conferences, such as American Public Health Association Annual Meeting and Expo, National Prevention Network, SAMHSA’s Prevention Day, Society for Prevention Research, and other conferences.

Analysis

Both the PPR and CORT data will be collected through the website. Both quantitative and qualitative analysis will be conducted.

Quantitative analysis: Descriptive statistical procedures will be used, including frequency counts and percentages. Some cross-tabulations will be used to help identify patterns within the responses.

Qualitative analyses of the CORT data will focus primarily on open ended responses grantees provide to describe their accomplishments and barriers.

Analysis will be at the aggregate level for all measures found in the CORT instrument (Attachments 1 – 6).

A.17 Display of Expiration Date

OMB approval expirations dates will be displayed.

A.18. Exceptions to Certification for Statement

There are no exceptions to the certification statement. The certifications are included in this submission.

REFERENCES

Blow, D. (2020). Perceived availability and efficacy of in-school prevention programs: Association with school counselor well-being.

Brown, J. L., Gause, N. K., & Northern, N. (2016). The Association between Alcohol and Sexual Risk Behaviors among College Students: A Review. Current addiction reports, 3(4), 349-355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-016-0125-8

Calear, A. L., & Christensen, H. (2010). Systematic review of school-based prevention and early intervention programs for depression. Journal of Adolescence, 33(3), 429–438.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, March 03). Wide-ranging online data for Epidemiologic research (WONDER). Retrieved from http://wonder.cdc.gov.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019 and 2021), YRBSS 2019 and 2021-Youth Online Analysis. Accessed Dec 8, 2023 - https://nccd.cdc.gov/Youthonline/App/Default.aspx

Ciccarone D. The rise of illicit fentanyls, stimulants and the fourth wave of the opioid overdose crisis. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021 Jul 1;34(4):344-350. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000717. PMID: 33965972; PMCID: PMC8154745.

Friedman, J., Shover, C.L. (2023). Charting the fourth wave: Geographic, temporal, race/ethnicity, and demographic trends in polysubstance fentanyl overdose deaths in the United States, 2010-2021. Addiction. 2023 Dec;118(12):2477-2485.

Lemstra, M., Bennett, N., Nannapaneni, U., Neudorf, C., Warren, L., Kershaw, T., et al. (2010). A systematic review of school-based marijuana and alcohol prevention programs targeting adolescents aged 10–15. Addiction Research and Theory, 18, 84–96.

Murthy, V. (2021). Youth mental health - current priorities of the U.S. Surgeon general. - Current Priorities of the U.S. Surgeon General. https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/priorities/youth-mental-health/index.html

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2022). Monitoring the future study, National Survey Results on Drug Use: 1975-2022. 2022 Overview. Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Available at: https://monitoringthefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/mtfoverview2022.pdf

Sacks J.J., Gonzales K.R., Bouchery E.E., Tomedi L.E., Brewer R.D. (2015). 2010 national and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. American Journal of Preventive Medicine,2015; 49:ve73–e79.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, 2016. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt39443/2021NSDUHFFRRev010323.pdf

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, 2016. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt42731/2022-nsduh-nnr.pdf

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Results from the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables; Prevalence Estimates, Standard Errors, P Values, and Sample Size. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt42728/NSDUHDetailedTabs2022/NSDUHDetailedTabs2022/2022-nsduh-detailed-tables.pdf

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Strategic Plan: Fiscal Year 2023-2026. Publication No. PEP23-06-00-002 MD: National Mental Health and Substance Use Laboratory, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2023.

Washington State Institute for Public Policy. (2015, February). https://www.wsipp.wa.gov/ReportFile/1602/Wsipp_What-Works-and-What-Does-Not-Benefit-Cost-Findings-from-WSIPP_Report.pdf

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | Snaauw, Roxanne |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2024-10-07 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy